#Charles Lang Freer

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Plaque in the form of animals

National Museum of Asian Art

Previous custodian or owner Yamanaka and Co. 山中商会 (1917-1965) (C.L. Freer source) Charles Lang Freer (1854-1919)

Smithsonian Open Access

#plaques#animals#Charles Lang Freer#Yamanaka and Co.#Smithsonian Open Access#National Museum of Asian Art

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

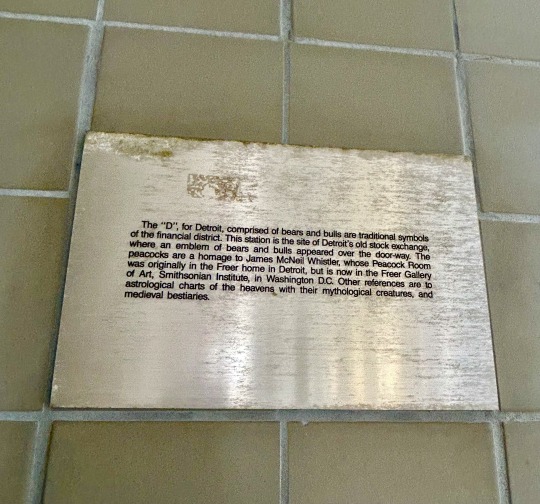

Art in the Stations: Financial District

The Financial District is home to some of Detroit's most beautiful art-deco skyscrapers, including The Guardian, Buhl, Ford, and Penobscot Buildings. The People Mover Station features Aztec and Byzantine designs, integrating both the neighborhood's architecture and history.

The large hand-painted mural "'D' For Detroit" by Joyce Kozloff includes mythical animals, peacocks, the bull and bear of the Stock Exchange, and an illuminated "D." The mural design is inspired by the Guardian Building, the Fisher Building, and Diego Rivera's Detroit Industry Murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Kozloff created and hand-painted each tile herself in Kohler, Wisconsin at the John Michael Kohler Art Center. She has also worked on several other public art installations around the country, including Harvard Square and the 86th and Central Park Street Subway Station.

The peacocks were inspired by James McNeill Whistler's paintings, who had designed "The Peacock Room" at 49 Prince's Gate in London, owned by British shipping magnate Frederick Richards Leyland. The room was preserved in 1904 by Charles Lang Freer, who installed it in his home at 71 E. Ferry Avenue. The original wall is now on display at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC.

#artinthestations#detroitpeoplemover#financialdistrict#publicart#detroit#downtowndetroit#financialdistrictdetroit#freerhome#charleslangfreer#thepeacockroom

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

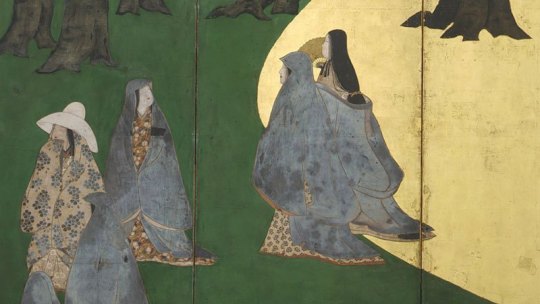

MWW Artwork of the Day (8/19/23) After Zhou Wenju (Chinese, fl. mid-10th c.) The Goddess Chang'e in the Lunar Palace (16th-17th c. copy) Ink and color on silk, 29.5 x 29.1 cm. Sackler-Freer Gallery, Washington DC (Gift of Charles Lang Freer)

In primordial times, the legendary hunter Yi once received the elixir of immortality from the great goddess, the Queen Mother of the West. Before he could consume the elixir, however, Yi's wife Chang'e (or Heng'e) stole the concoction and ingested it herself, thereby becoming an immortal. Fearing her husband's wrath, Chang'e fled to the moon, where she dwells for eternity in the Palace of Boundless Cold. Among the many denizens of the moon, the white rabbit, seen beside her on the terrace, is generally shown preparing the elixir of immortality with a mortar and pestle.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guqin (古琴 ), late 17th–mid 18th century. Wood, silk, mother-of-pearl. 47 1/2 × 7 3/8 × 2 15/16 in. Photo courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of J. C. Y. Watt, 2011.

The following excerpts are attributed to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Endowed with cosmological and metaphysical significance and empowered to communicate the deepest feelings, this zither, beloved of sages and of Confucius, is the most prestigious instrument in China. In performance, the qin symbolizes the union of heaven, earth, and humankind. The three basic playing techniques, sanyin, fanyin, and anyin, represent earth, heaven, and humans, respectively.

Copy after Qiu Ying 仇英 (c. 1494–1552), Playing the Zither Beneath a Pine Tree (detail), Ming dynasty, late 16th-early 17th century, ink and color on paper, China, 22.2 x 105.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1953.84)

Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) writers state that the qin helped to cultivate character, understand morality, supplicate gods and demons, enhance life, and enrich learning.

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) literati who claimed the right to play the qin suggested that it be played outdoors in a mountain setting, a garden or a small pavilion or near an old pine tree (symbol of longevity) while burning incense perfumed the air. A serene moonlit night was considered an appropriate time for performance.

Each part of the instrument is identified by an anthropomorphic or zoomorphic name and cosmology is ever present: for example, the upper board of wutong wood symbolizes heaven, the bottom board of zi wood symbolizes earth. Qins over a hundred years old are considered best, the age determined by the pattern of cracks (duanwen) in the lacquer. The 13 studs (hui) indicate finger positions. Strings of varying thicknesses are traditionally made of twisted silk.

0 notes

Text

Watching the CNN interview, I noticed that the Letter to the Romans fragment was shown and commented on upside down. At first I laughed at the ignorance (remember, academics are arrogant). But now, I rather interpret the episode as further proof of my argument about the Green family’s collecting—perhaps rather hoarding—attitude. Collectors truly interested in what they collect often become specialists. This was the case of many manuscript collectors of the last century who spent fortunes, as the Green family did, on manuscripts and rare books. John P. Morgan, Charles Lang Freer, and Alfred Chester Beatty all acquired early biblical papyri. Being successful businessmen, they were aware of the economy behind collecting and the potential personal gain they could get from it, and they bought aggressively in Egypt and elsewhere without paying too much attention to the provenance of their acquisitions—all things the Greens did too. But Morgan, Freer, Chester Beatty, and the like were also personally invested in the running of their collections and in learning from the manuscripts they accumulated. While researching this book and the market, I have met collectors very savvy about their acquisitions; like Steve Green, they consider papyri and other manuscripts as a form of investment, but nevertheless are truly passionate and have built an academic knowledge about what they collect.

-- from Stolen Fragments: Black Markets, Bad Faith, and the Illicit Trade in Ancient Artefacts by Roberta Mazza

0 notes

Text

Watching the CNN interview, I noticed that the Letter to the Romans fragment was shown and commented on upside down. At first I laughed at the ignorance (remember, academics are arrogant). But now, I rather interpret the episode as further proof of my argument about the Green family’s collecting—perhaps rather hoarding—attitude. Collectors truly interested in what they collect often become specialists. This was the case of many manuscript collectors of the last century who spent fortunes, as the Green family did, on manuscripts and rare books. John P. Morgan, Charles Lang Freer, and Alfred Chester Beatty all acquired early biblical papyri. Being successful businessmen, they were aware of the economy behind collecting and the potential personal gain they could get from it, and they bought aggressively in Egypt and elsewhere without paying too much attention to the provenance of their acquisitions—all things the Greens did too. But Morgan, Freer, Chester Beatty, and the like were also personally invested in the running of their collections and in learning from the manuscripts they accumulated. While researching this book and the market, I have met collectors very savvy about their acquisitions; like Steve Green, they consider papyri and other manuscripts as a form of investment, but nevertheless are truly passionate and have built an academic knowledge about what they collect.

-- from Stolen Fragments: Black Markets, Bad Faith, and the Illicit Trade in Ancient Artefacts by Roberta Mazza

0 notes

Text

National Museum of Asian Art Presents “Shifting Boundaries: Perspectives on American Landscapes”

“Blossom Time” (detail), Willard Metcalf (1858–1925), United States, 1910, oil on canvas, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Gallery of Art Collection, Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1915.27a-b The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art has announced “Shifting Boundaries: Perspectives on American Landscapes,” an exhibition featuring works by American painters such as…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

In Exaltation of Flowers, 1910-1913

Edward Steichen

#Edward Steichen#mural#In Exaltation of Flowers#flowers#Isadora Duncan#Charles Lang Freer#Mercedes de Cordoba#gold leaf

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is the Washington Codex of the Gospels AKA Codex Washingtonianus?

The Codex Washingtonianus or Codex Washingtonensis, designated by W or 032 (in the Gregory-Aland numbering), ε 014 (Soden), also called the Washington Manuscript of the Gospels, and The Freer Gospel, contains the four biblical gospels and was written in Greek on vellum in the 4th or 5th century.[1] The manuscript is lacunose.

Codex_Washingtonensis_W_032 – Painted cover of the Codex…

View On WordPress

#Charles Lang Freer#Codex Washingtonensis#Codex Washingtonianus#New Testament Textual Criticism#New Testament Textual Studies#Washington Codex

0 notes

Photo

"Undersea creature (ningyo or mermaid)". Artist: Kawahara Keiga. 1828, Japan. Ink and color on Dutch paper. Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment

691 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afterlife: Ancient Chinese Jades

Gallery 19

A construction boom in China more than a century ago resulted in new railways and factories—and the accidental discovery of scores of rich ancient cemeteries. Buried in these tombs for thousands of years were jewelry and ritual objects, all laboriously crafted from jade. When Charles Lang Freer acquired many of them, their precise age was unknown. The modern science of archaeology was not practiced in China until 1928, when the Smithsonian sponsored its introduction. With the advent of archaeology came a better appreciation of the evolution of ancient Chinese mortuary culture and China’s art history.

Today we know these jades represent the earliest epochs of Chinese civilization, the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age. Many came from the prehistoric burials of the Liangzhu culture (circa 3300–2250 BCE). These Stone Age people flourished in a large, fertile region between the modern cities of Shanghai, Hangzhou, and Nanjing. The graves they left behind now function like time capsules, providing insight into the dynamic character of ancient Chinese civilization during life and after death.

National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian

#jade#stone#exhibition#neolithic#erlitou culture#anyang period#han dynasty#eastern han dynasty#shang dynasty#art#art history#archaeology#Chinese#Liangzhu culture#minerals#National Museum of Asian Art#Smithsonian#重陽節#Double Ninth Festival#sculpture#jewellery#period dress#symbolism#archaism#repurpose#cultural amalgam

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1817, Japan. "Asagao sō" . Artist: Kinrin 琴鱗. Purchase, The Gerhard Pulverer Collection — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, Friends of the Freer and Sackler Galleries and the Harold P. Stern Memorial fund in appreciation of Jeffrey P. Cunard and his exemplary service to the Galleries as chair of the Board of Trustees (2003-2007)

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape, Ren Yu, 1892, Cleveland Museum of Art: Chinese Art

These seasonal landscapes (1915.97.3 and 1915.97.4) are from a set of four hanging scrolls by Ren Yu. He was the youngest, most eccentric, and least prolific of the Four Rens, a family of prominent painters in Shanghai during the late Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Perhaps due to his opium habit and subsequent financial difficulties, Ren Yu tended to be lackadaisical in his work. The few remaining high-quality paintings hint at his artistic potential lost to opium. Though Ren’s premature death left his artistic promise unfulfilled, his paintings on view were acquired and donated to the museum by Charles Lang Freer (1854–1919), a wealthy businessman and art collector from Detroit. As Freer had hoped, this donation of Ren Yu paintings inspired the young Cleveland Museum of Art to continue to expand its own Chinese painting collection. Size: Overall: 149.8 x 40.7 cm (59 x 16 in.) Medium: hanging scroll, color on paper

https://clevelandart.org/art/1915.97.3

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Silk, karaori, – fragment of a No robe" . early 19th century, Japan. silk. Gift of Charles Lang Freer

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ladies Among Cherry Trees

Artist: Style of Tawaraya Sōtatsu 俵屋宗達 (fl. ca. 1600-1643) Edo period, 1590-1640 School: Rinpa Ink, color, gold, and silver on paper H x W (.101): 165.4 x 378 cm (65 1/8 x 148 13/16 in) H x W (.102): 165.3 x 378.3 cm (65 1/16 x 148 15/16 in) Japan Credit Line: Gift of Charles Lang Freer Freer Gallery of Art Accession Number: F1903.101-102

#Tawaraya Sōtatsu#Ladies Among Cherry Trees#Edo Period#Art History#Art#Tales of the Genji#Lit#Japanese#Japanese Art

116 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Banshan type jar, Gansu ware, Neolithic period, 5000–2000 B.C.E., earthenware with iron pigments, China, 36.1 x 42.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1930.96)

2 notes

·

View notes