#New Testament Textual Studies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tuesday September 26th

More library photos, as that is where I’m studying this afternoon. I still can’t get over how pretty my college library is. There are several other libraries on campus, but I haven’t yet explored any other than my own because this one is so lovely.

Had New Testament class this morning. I spent almost an hour afterwards talking with the professor about New Testament textual criticism. It was really fun.

I have class again this evening, so I will stay around the college. There’s not really much point in going home; especially since I get more done and less distracted when I’m on campus.

#aelstudies#studyblr#university#dark academia#university studyblr#dark acadamia aesthetic#academia aesthetic#study motivation#books#library#new testament#textual criticism#religious studies#biblical studies

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Thinking Regarding Marcion of Sinope, Creator of The First New Testament, by James Bean

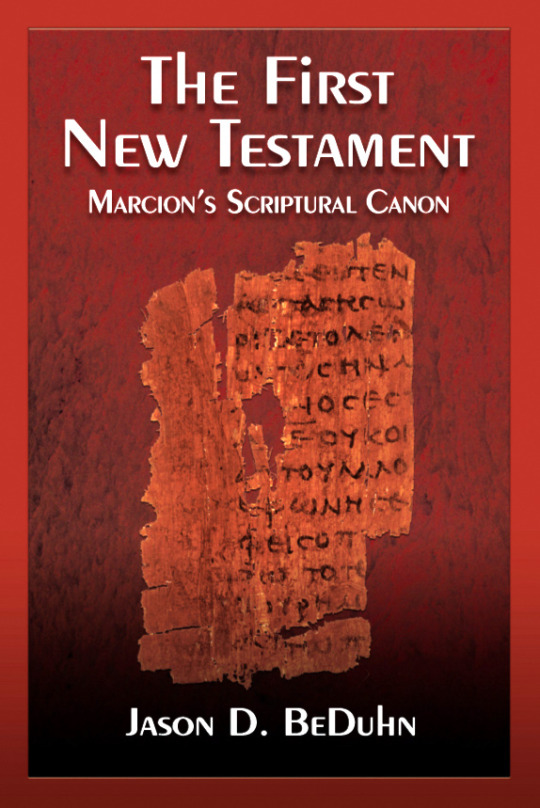

The old views regarding Marcion is that he was a semi-gnostic "heretic" who was the heavy-handed editor of early Christian texts snipping out references to the Hebrew scriptures. This however is simply parroting the old propaganda against Marcion concocted by the heresiologists, the heresy hunting church fathers not exactly known for complete accuracy and honesty. The more recent scholarly research and subsequent updates regarding Marcion is that he was the one who first invented the idea of a Christian canon of scripture consisting of one gospel followed by ten letters of the Apostle Paul. Marcion was not an editor of the Gospel of Luke but made use of an early gospel from an unknown author that others would eventually plagiarize, adopt, edit and expand into what we now call the Gospel of Luke. The letters of Paul in Marcion's collection are the genuine ones actually authored by Paul. This collection of Marcionite texts represents earlier material than the more familiar final versions found in the New Testament canon.

Thus being the EARLIEST NEW TESTAMENT Marcion's First New Testament is an extremely valuable source for the study of the original proto-Luke gospel (the Evangelion) and letters of Paul (the Apostolikon). A few reconstructions of Marcion's New Testament have been made including The First New Testament: Marcion's Scriptural Canon, by Jason Beduhn: "The earliest version of the New Testament, now in English for the first time! History preserves the name of the person responsible for the first New Testament, the circumstances surrounding his work, and even the date he decided to build a textual foundation for his fledgling Christian community. So why do so few people know about him? Jason BeDuhn introduces Marcion, reconstructs his text, and explores his impact on the study of Luke-Acts, the two-source theory, and the Q hypothesis."

Discussions regarding the above:

Reconstructing the FIRST New Testament! https://youtu.be/Q27JRfu35qE?si=dqNqU9aGzNO2lmcT

The Apostolos: https://www.youtube.com/live/Ou3Xrtme91c?si=eOL5xoQ1mE8plNS_

Marcion, Found Christianities Series: https://youtu.be/DktjZVfUWHU?si=hiQPHCZ-a3cuCXwD

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Rich Tapestry of Bible History: Insights into Faith, Culture, and Humanity

Unveiling the Tapestry of Bible History: A Journey Through Time

The Bible stands as a monumental work of literature, religion, and history, revered by millions around the globe. Its pages contain a rich tapestry of stories, teachings, and accounts that have shaped civilizations, inspired movements, and influenced cultures for millennia. Delving into the annals of Bible history unveils a captivating narrative that spans centuries and continents, offering profound insights into the human condition and our relationship with the divine.

Ancient Beginnings

The roots of Bible history trace back to ancient Mesopotamia, where the earliest narratives of the Hebrew Bible (known as the Old Testament) took shape. From the creation story in Genesis to the epic tales of Abraham, Moses, and the Israelites, these foundational texts lay the groundwork for the monotheistic faith of Judaism.

The Rise of Empires

As empires rose and fell throughout the ancient Near East, the Hebrew people found themselves entangled in a web of political intrigue and cultural exchange. The conquests of Assyria, Babylon, and Persia shaped the landscape of the biblical narrative, providing the backdrop for stories of exile, redemption, and the struggle for identity.

The Life of Jesus

In the first century CE, a Jewish teacher from the backwater town of Nazareth emerged as a central figure in the unfolding drama of Bible history. Jesus of Nazareth challenged the religious authorities of his time, proclaiming a message of love, forgiveness, and the coming Kingdom of God. His teachings and actions, as recorded in the New Testament, sparked a movement that would ultimately transform the course of world history.

Spread and Impact

The spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire brought the message of the Bible to new lands and cultures, reshaping societies and influencing art, literature, and politics. From the catacombs of Rome to the libraries of Constantinople, the Bible became a cornerstone of Western civilization, its stories and teachings woven into the fabric of daily life.

Challenges and Interpretations

Yet, the history of the Bible is not without its controversies and challenges. From debates over authorship and textual authenticity to the clash of religious interpretations and the rise of secular skepticism, the Bible has been a flashpoint for intellectual inquiry and spiritual struggle.

Legacy and Relevance

Despite the passage of centuries, the Bible continues to exert a profound influence on the modern world. Its stories of faith, courage, and redemption speak to the universal human experience, transcending time and culture. Whether as a sacred scripture, a literary masterpiece, or a historical document, the Bible remains a touchstone for millions, inviting readers to explore its depths and discover new layers of meaning. In conclusion, the history of the Bible is a testament to the enduring power of faith, the resilience of human spirit, and the inexorable march of time. Through its pages, we glimpse the triumphs and tribulations of generations past, finding echoes of our own journey in the tapestry of Bible history.

Also Read:-

Bible Lessons

Bible Principle

Bible Stories

Bible Study

Online Bible

Bible Teachings

Bible Verses

Free Online Bible

Online Bible

Scripture Online

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

This late-thirteenth-century New Testament is of extraordinary importance to our understanding of English mediaeval royal culture, politics, and diplomacy during the Hundred Years’ War. Although as the work of the Cholet Master its decoration makes it a very attractive object in its own right, it is its textual interest and staggering provenance which make it a national treasure. The manuscript is previously unknown to scholarship, having been in private hands for over 300 years. Excitingly, the particular French translation of the New Testament it contains appears to be unique and ripe for significant philological research. Furthermore, it was owned by Jean II ‘le Bon’, King of France (1350-1364), whose signature – an exceedingly rare survival – is on its final page. It is highly likely that it was seized as war booty when he and his possessions were taken hostage at the Battle of Poitiers by the Black Prince in 1356, and it has been in England ever since. [...] Provenance: Owned by Jean le Bon, King of France, whose name is inscribed on the final page. Other erased inscriptions, readable under ultraviolet light, show that the manuscript was owned by Thomas of Lancaster, Duke of Clarence (1387–1421), second son of King Henry IV of England, and by Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset (1406–1455). Beaufort gave the manuscript to Humphrey of Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester (1390–1447), fourth son of Henry IV and bibliophile.

For the impact on the studies of Humphrey's manuscript collection in particular (and for information about two other manuscripts connected with him this year), David Rundle has a blog post here.

#manuscripts#humphrey duke of gloucester#thomas duke of clarence#edmund beaufort 2nd duke of somerset#edward the black prince#jean ii of france#hundred years war#medieval france#patronage#historian: david rundle

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Paul Teaching an Imminent Eschatology in 1 Corinthians 15:51?

Eli Kittim

Some commentators have claimed that Paul’s language in 1 Corinthians 15:51 is referencing an imminent eschatology. Our primary task is to analyze what the critical Greek New Testament text actually says (not what we would like it to say), and then to ascertain if there are any proofs in it of an imminent eschatology. Let’s start by focusing on a particular verse that is often cited as proof of Paul’s imminent eschatology, namely, 1 Corinthians 15:51. It is alleged that this verse seems to suggest that Paul’s audience in Corinth would live to see the coming of Christ. But we must ask the question:

What in the original Greek text indicates that Paul is referring specifically to his immediate audience in Corinth and not to mankind collectively, which is in Christ? We can actually find out the answer to this question by studying the Greek text, which we will do in a moment.

At any rate, it is often asserted that the clause “We shall not all die" (in 1 Corinthians 15:51) does not square well with a future eschatology. These commentators often end up fabricating an entire fictional scenario that is not even mentioned in the original text. For starters, the plural pronoun “we” seems to be referring to the dead, not to people who are alive in Corinth (I will prove that in a moment). And yet, on the pretext of doing historical criticism, they usually go on to concoct a fictitious narrative (independently of what the text is saying) about how Paul is referring to the people of Corinth who will not die until they see the Parousia.

But, textually speaking, where does 1 Corinthians 15:51 mention the Corinthian audience, the Parousia, or that the Corinthians will still be alive to see it? They have rewritten a novel. None of these fictitious premises can be found in the textual data. Once again, I must ask the same question:

What in the original Greek text indicates that Paul is referring to his audience (which is alive) in Corinth and not to the dead in Christ (collectively)?

We can actually find out the answer to this question by studying the Greek text, which we will do right now!

As I will demonstrate, this particular example does not prove an imminent eschatology based on Paul’s words and phrases. In first Corinthians 15:51, the use of the first person plural pronoun “we” obviously includes Paul by virtue of the fact that he, too, will one day die and rise again. In fact, there is no explicit reference to the rapture or the resurrection taking place in Paul’s lifetime in 1 Corinthians 15:51. In the remainder of this commentary, I will demonstrate the internal evidence (textual evidence) by parsing and exegeting the original Greek New Testament text!

Commentators often claim that the clause “We shall not all die" implies an imminent eschatology. Let’s test that hypothesis. Paul actually wrote the following in 1 Corinthians 15:51 (according to the Greek NT critical text NA28):

πάντες οὐ κοιμηθησόμεθα, πάντες δὲ

ἀλλαγησόμεθα.

My Translation:

“We will not all sleep, but we will all be

transformed.”

In the original Greek text, there is no separate word that corresponds to the plural pronoun “we.” Rather, we get that pronoun from the case endings -μεθα (i.e. κοιμηθησόμεθα/ἀλλαγησόμεθα). The Greek verb κοιμηθησόμεθα (sleep) is a future passive indicative, first person plural. It simply refers to a future event. But it does not tell us when it will occur (i.e. whether in the near or distant future). We can only determine that by comparing other writings by Paul and the eschatological verbiage that he employs in his other epistles. Moreover, it is important to note that the verb κοιμηθησόμεθα simply refers to a collective sleep. It does not refer to any readers in Corinth!

Similarly, the verb ἀλλαγησόμεθα (we will all be transformed) is a future passive indicative, first person plural. It, too, means that all the dead who are in Christ, including Paul, will not die but be changed/transformed. The event is set in the future, but a specific timeline is not explicitly or implicitly given, or even suggested. Both expressions (i.e. κοιμηθησόμεθα/ἀλλαγησόμεθα) refer to all humankind in Christ or to all the elect that ever lived (including, of course, Paul as well) because both words are preceded by the adjective πάντες, which means “all.” In other words, Paul references “all” the elect that have ever lived, including himself, and says that we will not all perish but be transformed. We must bear in mind that the word πάντες means “all,” and the verb “we will all be changed” (ἀλλαγησόμεθα) refers back to all who sleep in Christ (πάντες κοιμηθησόμεθα). Thus, the pronoun “we,” which is present in the case endings (-μεθα), is simply an extension of the lexical form pertaining to those who sleep (κοιμηθησόμεθα). So, the verb κοιμηθησόμεθα simply refers to all those who sleep. Once again, the adjective πάντες (all/everyone)——in the phrase “We will not all sleep”—— does not refer to any readers in Corinth.

There is not even one reference to a specific time-period in this verse (i.e. when it will happen). Not one. And the plural pronoun “we” specifically refers to all the dead in Christ (πάντες κοιμηθησόμεθα), not to any readers alive in Corinth (eisegesis).

And that is a scholarly exegesis of how we go about translating the meanings of words accurately, while maintaining literal fidelity. It’s also an illustration of why we need to go back to the original Greek text rather than to rely on corrupt, paraphrased English translations (which often include the translators’ theological interpretative biases).

Conclusion

What commentators often fail to realize is that the first person plural pronoun “we” includes Paul because he, too, is part of the elect who will also die and one day rise again. Koine Greek——the language in which Paul wrote his epistles——is interested in the so-called “aspect” (how), not in the “time” (when), of an event. First Corinthians 15:51 does not suggest specifically when the rapture & the resurrection will happen. And it strongly suggests that the plural pronoun “we” is referring to the dead, not to the readers who, by contrast, are alive in Corinth.

Some commentators are simply trying to force their own interpretation that doesn’t actually square well with the grammatical elements of 1 Corinthians 15:51 or with Paul’s other epistles where he explicitly talks about the Day of the Lord (2 Thessalonians 2:1-12) and the last days (1 Timothy 4:1; 2 Timothy 3:1 ἐν ἐσχάταις ἡμέραις), a time during which the world will look very different from his own. The argument, therefore, that 1 Corinthians 15:51 is referring to an Imminent Eschatology is not supported by the textual data (or the original Greek text).

What is more, if we compare the Pauline corpus with the eschatology of Matthew 24 & 2 Peter 3:10, as well as with the totality of scripture (canonical context), it will become quite obvious that all these texts are talking about the distant future!

If anyone thinks that they can parse the Greek and demonstrate a specific time-period indicated in 1 Corinthians 15:51, or that the phrase “all who sleep” (πάντες κοιμηθησόμεθα) is a reference to the readers in Corinth, please do so. I would love to hear it. Otherwise, this study is incontestable/irrefutable!

The same type of exegesis can be equally applied to 1 Thessalonians 4:15 in order to demonstrate that the verse is not referring to Paul’s audience in Thessalonica, but rather to a future generation that will be alive during the coming of the Lord (but that's another topic for another day):

ἡμεῖς οἱ ζῶντες οἱ περιλειπόμενοι εἰς τὴν

παρουσίαν τοῦ κυρίου.

“we who are alive, who are left until the

coming of the Lord.”

If that were the case——that is, if the New Testament was teaching that the first century Christians would live to see the day of the lord——it would mean that both Paul and Jesus were false prophets who preached an imminent eschatology that never happened.

#1Corinthians15v51#1Thessalonians4v15#imminent eschatology#preterism#realized eschatology#the little book of revelation#koineGreek#PaulineCorpus#historicalcriticism#parousia#historicalgrammaticalmethod#futurism#paul the apostle#Τομικροβιβλιοτηςαποκαλυψης#futureeschatology#resurrection#Biblicaleschatology#bible prophecy#textual criticism#KoineGreekgrammar#inauguratedeschatology#rapture#parsingkoineGreek#EK#last days#day of the lord#eschaton#bible study#ελκιτίμ#elkittim

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

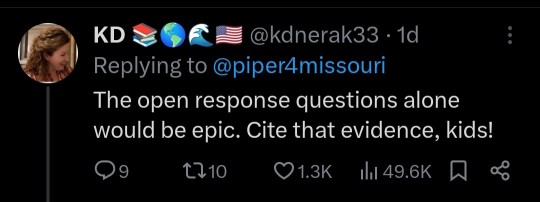

I don't know about American Bible classes, but I think I learned about 75% of what I know about textual criticism from Bible classes in my church before I even hit full puberty. All the literature classes I've had since then only polished something that was already hardwired in me.

To the point that I once had a very amusing online conversation with some atheist or other who thought that the fact there are different versions of the text in tiny writing in your Bible would be a world-shattering revelation to me. Like, excuse me, my minister pointed and explained those out to me when I was maybe eight, and my great-uncle was one of the people involved in the translation and compiling process and was probably responsible for some of those footnotes in my language.

To the point that I, a Christian, recently had to explain to a random smug Christianity-mocker online what textual criticism even was, because they thought criticism = attacking something, and, surprise surprise, that's actually not what the word means, and you might know that if you spent more of your life actually paying attention to texts instead of mocking people who, for whatever reason, do.

I need to stress this to anyone whose impression of Christianity is mainly based on American conservatives and their current batshit crazy worldviews. To anyone still wondering what I'm talking about, serious Bible study basically actually is where textual criticism was born. Nothing like comparing many many versions and translations of an important cultural text in an attempt to compile a definitive version to force people to think critically about texts and words and their meanings and origins and biases.

It probably helps that the minister we had when I was that age went on to teach New Testament at the main Protestant theological faculty in my country and is now the faculty's head...

It didn't make me an atheist. But it definitely made me a different sort of Christian than American conservatives. Not that that was hard, my church is not that kind of church to begin with.

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

7 Wonders of the World

History & Society

In 2000, a Swiss foundation launched a campaign to determine the New Seven Wonders of the World. Given that the authentic Seven Wonders list was compiled in the second century BCE and that only one entrant is still standing (the Pyramids of Giza), it seemed time for a replacement. And humans around the sector reputedly agreed, as more than a hundred million votes have been cast on the Internet or by using textual content messaging. The final outcomes, which were introduced in 2007, have been met with cheers as well as a few jeers—some of the outstanding contenders, including Athens’s Acropolis, failed to make the cut. Do you consider the brand new listing?

Great Wall of China

Great is probably an understatement. One of the world’s largest building production projects, the Great Wall of China, is broadly thought to be approximately 5,500 miles (8,850 km) long; a disputed Chinese study claims the period is thirteen hundred and seventy miles (21,200 km). Work started in the 7th century BCE and persevered for two millennia. Although called a “wall,” the structure absolutely features parallel partitions for prolonged stretches. In addition, watchtowers and barracks dot the bulwark. One not-so-super aspect of the wall, however, turned into its effectiveness. Although it was built to prevent invasions and raids, the wall, in large part, failed to offer actual safety. Instead, students have stated that it served more as “political propaganda.

Great Wall Of China

Chichen Itza

Chichen Itza is a Mayan city on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico that flourished within the ninth and 10th centuries CE. Under the Mayan tribe Itza—who were strongly encouraged by the Toltecs—some essential monuments and temples have been built. Among the most extraordinary is the stepped pyramid El Castillo (“The Castle”), which rises 79 feet (24 meters) above the Main Plaza. A testament to the Mayans’ astronomical abilities, the structure functions as a complete 365-step system for the wide variety of days within the sun year. During the spring and autumnal equinoxes, the putting sun casts shadows on the pyramid that give the appearance of a serpent slithering down the north stairway; at the base is a stone snake head. Life there has been now, not all paintings and technological know-how, but. Chichen Itza is home to the largest tlachtli (a type of wearing discipline) within the Americas. In that area, the citizens played a ritual ball sport famous throughout pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

Chichen Itza

Petra

The historical metropolis of Petra, Jordan, is located in a far-flung valley, nestled amongst sandstone mountains and cliffs. It was alleged to be one of the places in which Moses struck a rock and water gushed forth. Later, the Nabataeans, an Arab tribe, made it their capital, and all through this time, it flourished, becoming an important alternate middle, especially for spices. Noted carvers, the Nabataeans chiseled dwellings, temples, and tombs into the sandstone, which changed color with the moving sun. In addition, they constructed a water machine that allowed for lush gardens and farming. At its peak, Petra reportedly had a population of 30,000. The city began to decline, but as exchange routes shifted, An important earthquake in 363 CE brought on greater difficulty, and after another tremor hit in 551, Petra was step by step deserted. Although rediscovered in 1912, it became largely overlooked with the aid of archaeologists until the overdue twentieth century, and many questions remain about the metropolis.

Petra

Machu Picchu

This Incan web page close to Cuzco, Peru, was “observed” in 1911 by Hiram Bingham, who believed it was Vilcabamba, a mystery Incan stronghold used throughout the 16th-century rebellion in opposition to Spanish rule. Although that declaration was later disproved, the purpose of Machu Picchu has confounded students. Bingham believed it was domestic to the “Virgins of the Sun,” girls who lived in convents under a vow of chastity. Others suppose that it changed into, in all likelihood, a pilgrimage website online, even though a few consider it a royal retreat. One aspect it apparently should not be is the website of a lager commercial. In 2000, a crane getting used for such an advertisement fell and cracked a monument. What is understood is that Machu Picchu is one of the few essential pre-Columbian ruins determined to be nearly intact. Despite its relative isolation high in the Andes Mountains, it has agricultural terraces, plazas, residential areas, and temples.

Machu Picchu

Christ the Redeemer

Christ the Redeemer, a huge statue of Jesus, stands on Mount Corcovado in Rio de Janeiro. It began right after World War I, when some Brazilians feared a “wave of atheism." A statue was proposed, which was eventually designed by Heitor da Silva Costa, Carlos Oswald, and Paul Landowsky. Construction began in 1926 and was completed five years later. The resulting monument stands 98 feet (30 meters) tall—not including the base, which is about 26 feet (8 meters) high—and its outstretched arms are 92 feet (28 meters) wide. It is an Art Deco sculpture that is the largest in the world. Christ the Redeemer is made of reinforced concrete and is covered with about six million tiles. Somewhat worryingly, the statue is frequently struck by lightning, and in 2014, the tip of Jesus’ right finger was damaged during a storm.

Christ the Redeemer

Colosseum

The Colosseum in Rome was built in the first century by order of Emperor Vespasian. An engineering feat, the theater measures 620 by 513 feet (189 by 156 meters) and features an impressive vault system. It was able to accommodate 50,000 spectators, and they watched events. Perhaps most notable were skirmishes, although fighting men and animals were also common. In addition, the Colosseum was once used for mock naval meetings. But the belief that Christians were killed there—that is, thrown to lions—is questioned. According to one estimate, some 500,000 people died in the Colosseum. In addition, so many animals have been captured and then killed there that some species are reportedly extinct

Colosseum

Taj Mahal

Located in Agra, India, this mausoleum is considered one of the most famous monuments in the world and is perhaps the finest example of Mughal architecture. It was built by Emperor Shah Jahan (reigned 1628–58) in honor of his wife Mumtaz Mahal (the “Elect Palace”), who died after giving birth to their 14th child in 1631. It took about 22 years and 20,000 workers, and the great building was built, including a large garden with a reflecting pool. The mausoleum is made of white stone with geometric beads of semi-precious stones. Its impressive central dome is flanked by four small domes. According to some reports, Shah Jahan wanted his mausoleum to be made of black marble. But before any work could begin, one of his sons deposed him.

Taj Mahal

In conclusion, the Seven Wonders of the World represent a unique collection of architectural works that transcend time, geography, and culture. Each with its own unique history and significance, these symbols are enduring symbols of human creativity, ingenuity, and aspiration. From the towering pyramids of Giza to the majestic Taj Mahal, these wonders have captivated people for centuries, inspiring awe, admiration, and reverence. The only surviving marvel of antiquity, the Great Pyramid of Giza, stands as a testament to the advanced technology of the ancient Egyptians. Built over 4,500 years ago, this mysterious wonder, in perfect harmony with its impressive buildings and massive limestone stones, leaves historians and archaeologists in awe.

0 notes

Text

Featured Author | Book Buzz Radio Interview | Rev. Dr. Henry B. Malone

Featured Book: The Preaching and Sacred Writings of St. Peter the Apostle Kata St. Mark The Biblical Scholarship series on the New Testament writings Modern Received Eclectic Text compared to the Early Papyri and Uncials VOLUME II

Written for Pastors and serious Bible scholars to give them more time in the Greek text. The first question for the serious Bible scholar should be "What is the text?" Only then are you ready to move on to "What does it mean?" The Sacred Preaching & Writings of St. Peter the Apostle presents the "Received Text" since its inception to present. This is the eclectic text used today for all major translations. The changes over time are color coded Greek script. The textual critic's effort to recover the original autographs is recorded as the top line. Like an interlinear Bible, a level one English translation is provided. Below this in parallel and vertical format are the major Greek Uncials and Papyri published. A few documents take us to within twenty to forty years of the original autographs. The mundane work has been done. Now a study of the text itself can occupy your study. All top line eclectic text verbs have be parsed and the first person indicative form is identified for you.

0 notes

Text

PAPYRUS 72 (P72) P. Bodmer VII and VIII: the letters of Jude, 1 Peter, and 2 Peter

PAPYRUS 72 (P72) P. Bodmer VII and VIII: the letters of Jude, 1 Peter, and 2 Peter

EDWARD D. ANDREWS (AS in Criminal Justice, BS in Religion, MA in Biblical Studies, and MDiv in Theology) is CEO and President of Christian Publishing House. He has authored over 140 books. Andrews is the Chief Translator of the Updated American Standard Version (UASV).

Image: 1 Peter 5:12–end and 2 Peter 1:1–5 on facing pages of Papyrus Bodmer VIII Name Papyrus Bodmer VII-IX Sign P72 Text…

View On WordPress

#New Testament Textual Criticism#New Testament Textual Studies#P. Bodmer VII#P.Bodmer VIII#P72#Papyrus 72

0 notes

Text

This reminds me 2 things.

1

One of my friend groups is getting annoyed by this(I personally genuinely don't care). I've literally seen them call the recent uptick in shipping women together with no textual basis fujoshi like behavior. Wich cracked me up.

2

When I explained death of the author to my mother, her go to personal example to relate to it was a short story written by Kurt Vonnegut self insert character Kilgore trout in which an alien trying to understand the cruelty of most Christians wrote a Fix-It fic for the Bible so that the story of Jesus Christ better encouraged the morals Christians claim their religion stands for.

“It was The Gospel From Outer Space, by Kilgore Trout. It was about a visitor from outer space...[who] made a serious study of Christianity, to learn, if he could, why Christians found it so easy to be cruel. He concluded that at least part of the trouble was slipshod storytelling in the New Testament. He supposed that the intent of the Gospels was to teach people, among other things, to be merciful, even to the lowest of the low. But the Gospels actually taught this: Before you kill somebody, make absolutely sure he isn't well connected. So it goes. The flaw in the Christ stories, said the visitor from outer space, was that Christ, who didn't look like much, was actually the Son of the Most Powerful Being in the Universe. Readers understood that, so, when they came to the crucifixion, they naturally thought...: "Oh, boy - they sure picked the wrong guy to lynch that time!" And that thought had a brother: "There are right people to lynch." Who? People not well connected. So it goes.”

The point I'm trying to make here I guess is that different people are going to have different levels of flexibility when engaging with texts. Some will surprise you and some will let you down.

the awesome thing about the internet is i realized i can just do to female characters what people do to male characters all the time

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching a debate between a Jewish and Christian scholar is fascinating, because there is as stark difference in how the Christian and Jewish person will conduct themselves when they stand at the podium. Obviously, there is a sense of professionalism, but there will also be a manner of articulating your points and arguments from boths sdies.

The Jewish scholar tends to be academical and often refer to sources to debuke any Christological and ecclesial supposition about the Tanakh/OT, whereas the Christian often appeals to emotion and will speak in a charismatic way to reinforce his belief in Christ rather than to substantiate their argument. The other issue I find with the Christian debater is that they attempt to substantiate their belief through the New Testament, a scripture which holds no weight to a Jewish person; it is as useful as a brick.

The challenge in debating a Jewish scholar is the fact that a Jewish scholar studies Hebrew and Aramaic and are often fluent in respective language, thus possessing an advantage in textual and hermeneutical analysis of the Masoretic text, whereas a Christian often make use of an already translated Bible, which has been prone to corruption, distortion and christological alterations throughout centuries.

548 notes

·

View notes

Text

A scientist said he found a chapter of the Bible hidden for more than 1,500 years.

Researchers used ultraviolet photography to spot the text, which was hidden beneath multiple edits.

Researchers said the manuscript was a "gateway" to understanding phases of the Bible's evolution.

Scientists say they have found an old version of a Bible chapter that was hidden underneath a section of text for more than 1,500 years.

Grigory Kessel, a historian at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, announced the discovery earlier this year in an article in New Testament Studies, a peer-reviewed academic journal published by Cambridge University Press.

Kessel said he used ultraviolet photography to see the earlier text under three layers of words written on a palimpsest, an ancient manuscript that people used to write over other words but often left traces of the original writing behind.

Palimpsests were used in ancient times due to the scarcity of parchment. Words would be written on the material repeatedly until several layers covered the hidden words underneath.

Kessel said in a news release that the text was an extended, unseen version of Chapter 12 in the Book of Matthew that was originally a part of the Old Syriac translations of the Bible some 1,500 years ago. He said he made the discovery in the manuscript held at the Vatican Library.

The manuscript offers a "unique gateway" for researchers to understand the earliest phases of the Bible's textual evolution, according to the news release, and shows some differences from modern translations of the text.

For instance, according to the release, the original Greek version of Matthew 12:1 — which is the one most commonly used today — said, "At that time Jesus went through the grainfields on the Sabbath, and his disciples became hungry and began to pick the heads of grain and eat."

The newly discovered Syriac translation, however, is slightly different. It said, "began to pick the heads of grain, rub them in their hands, and eat them."

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Tower” based on Deuteronomy 29:10-15 John 11:28-44

Last Summer Diana Butler Bass gave a sermon at the Wild Goose Festival that was shared and forwarded to me approximately 100 times, which was good because that's how many times it took for me to read it. And once I read it, I participated in the sharing and forwarding too. Her sermon was entitled “All the Marys”1 and it shared one of the biggest breakthroughs in Biblical Scholarship in generations.

Which, I know, is THE SINGLE MOST EXCITING THING I COULD EVER SAY! Or, perhaps, maybe, it might not be?

Stick with me.

It's worth it. This is a case where a huge break through in Biblical scholarship has pretty big implications for those of us who follow Jesus. I'm well aware they aren't all like that.

What I find interesting is that I've now read her sermon several times over the course of 10 months, and I can't seem to retain it. The implications are actually so big and require such an enormous re-framing of how I understand the early Christian story, that my brain keeps erasing it in favor of the familiar.

If you have spent less time in Gospel commentaries and/or seminary than I have, I suspect you are going to find it easier to accept these very simple truths than I do. Which is great! This is really awesome stuff, and I'd love for people to hear it, know it, and even retain it.

Diana Butler Bass tells the story of Elizabeth (Libbie) Schrader who felt moved to study Mary Magdalene, landed at General Theological Seminary in New York to work on a Masters of New Testament, and wrote her final paper on John 11. Her professor encouraged her to look at the newly digitized version of the oldest known text of John, Papyrus 66, from around 200 CE, and find something new in it.

I'm going to quote Diana Butler Bass here:

And so Libbie is in the library looking at the text and she sees this first sentence. And it’s in Greek, of course. “Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and his sister Mary.” And Libbie said, “What? That’s not what my English Bible says. My English Bible says, ‘Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister, Martha.’” But the Greek text, the oldest Greek text in the world doesn’t say that. The oldest Greek text in the world says, “Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, at the village of Mary and his sister, Mary.” There are two Marys in this verse. And Libbie went, “What the heck? What is going on here?” And she started digging into the text, zooming in on it to try to see what she could see over the digitized version in the internet. And lo and behold, Libbie noticed something that no New Testament scholar had ever noticed.

And that is, in the text where it had those two Marys, the village of Mary and his sister, Mary, and her sister, Mary, the text had actually been changed. In Greek, the word Mary, the name Mary, is basically spelled like Maria in English, M-A-R-I-A. And the I, the Greek letter I, is the letter Iota. And it looks basically like an English I. Libbie could see by doing this textual analysis that the Iota had been changed to the letter TH in Greek, Theta. That somebody at some point in time had gone in over the original handwriting and actually changed the second Mary to Martha. And not only had that person changed the second Mary to Martha, but that person had also changed the way it comes out in English. It says, “The village of Mary,” that would’ve stayed the same, “and her sister, Martha.” Someone had also changed that “his” to “her”; that “her” was originally a “his,” but they had changed it to a “her.”

Admittedly, the original text is a confused and not very good sentence. “Now, a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, at the village of Mary and his sister, Mary,” it’s almost like they’re heightening the fact that Lazarus has this sister, Mary. They lived in this village together, and Mary is Lazarus’ sister. Someone had changed it to read, “Mary and her sister, Martha.”

Libbie sat in the library with all of this, and it came thundering at her, the realization that sometime in the fourth century, someone had altered the oldest text of the Gospel of John and split the character Mary into two. Mary became Mary and Martha.

She went through the whole manuscript of John 11 and John 12, and lo and behold, that editor had gone in at every single place and changed every moment that you read Martha in English, it originally said, “Mary.” The editor changed it all.

Now, that's a pretty big deal, but I imagine that maybe you don't... umm... I think the words might be “Care that much.” But let me say, “yet.” I haven't gotten to the part where this MATTERS yet, that was a really important BACKGROUND. It also makes John 11 as we know it really hard to read and make sense of. But that's OK too.

So the underlying question in this is “why?” Why would someone go through so much trouble to create the character Martha out of what was once Mary? The key may be in the part of John 11 we read last week,

25Jesus said, “I am the resurrection, and the life: the one that believes in me, though they may die, yet shall they live; 26and the one who lives and believes in me shall never die. Do you believe this?” 27She said to him, “Yes, Lord: I have believed that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one that comes into the world.

In the Bibles I have that “she” appears to be Martha but if she doesn't exist, then the she is Mary. And now we're getting to it. Christianity has long claimed that the first declaration that Jesus was the Messiah comes from Peter, the Rock, who is presented as having done so in Mark, Matthew, and Luke (the “Synoptics”) and that answer kinda worked because Martha was a pretty minor character and even though she says so in John, it is easy enough to ignore because Peter is THE ROCK, and Martha is... well, kinda a nobody.

Back to Diana Bulter Bass:

But if it is Mary, the Mary who shows up in John 11 is not an unremembered Mary... This Mary has long been suspected of being the other Mary, Mary Magdalene. Is it really true that the other Christological confession of the New Testament comes from of the voice of Mary Magdalene? That the Gospel of John gives the most important statement in the entirety of the New Testament, not to a man, but to a woman, and to a really important woman who will show up later as the first witness to the resurrection.

You see how these two stories work together. In John 11, Lazarus is raised from the dead, and who is there but Mary Magdalene? And at that resurrection, she confesses that Jesus is indeed the son of God. And then you go just 10 chapters later and who is the person at the grave? She mistakes him, at first, thinks he’s the gardener. She turns around and he says, “Mary,” and she goes, “Lord.” It’s Mary Magdalene. It is Mary Magdalene.

Oh, and now I get to place for you the final piece. Do you remember learning that Christ wasn't Jesus' last name? I do. Christ is the English version of Christos which was the Greek translation of Messiah, which literally meant “smeared” as in “smeared with oil” as in “annointed as king” because the Greek didn't have a Messiah concept like Hebrew did. So when we say Jesus Christ, we are actually saying “Jesus the Messiah.”

Well, a lot of people think Mary Magdalene was called that cause she was Mary, from Magdala. Except there was no village called Magdala. Diana Butler Bass summariezes it this way:

When we call her Magdalene, Mary Magdalene, is not Mary from Magdala. Instead, it’s a title.

The word magdala in Aramaic means tower. And so now you get the full picture. In the Synoptics, Jesus and Peter have a discussion. In that discussion, Peter utters the Christological confession. As a result of the Christological confession, Jesus says, “You are Peter the Rock.” In the gospel of John, Mary and Jesus have a conversation, and Mary utters the Christological confession. And she comes to be known as Mary the Tower.

Between these two confessions, are we looking at an argument in the early church? Peter the Rock or Mary the Tower?

But the John account was changed. The John story has been hidden from our view. All those years ago, Mary uttered those words, “Yes, Lord, I believe you are the Messiah, the son of God, the one who is coming into the world.” …

Mary is indeed the tower of faith. That our faith is the faith of that woman who would become the first person to announce the resurrection. Mary the Witness, Mary the Tower, Mary the Great, and she has been obscured from us. She has been hidden from us and she been taken away from us for nearly 2,000 years. …

Or, or perhaps and, you can leave here with a question: What if the other story of Mary hadn’t been hidden? What if Mary in John 11 hadn’t been split into two women? What if we’d known about Mary the Tower all along? What kind of Christianity would we have if the faith hadn’t only been based upon, “Peter, you are the Rock and upon this Rock I will build my church”? But what if we’d always known, “Mary, you are the Tower, and by this Tower we shall all stand?”

OK, that's it. That's my big Biblical Studies breakthrough story. Perhaps you might want to laugh with me that the big breakthrough is simply another affirmation that God loves and cares about all people, JUST LIKE THE TEXT FROM DEUTERONOMY said in a lot fewer words.

But, dear ones, what if we'd gotten both stories? And maybe the even more important question: how can we live now that we have both stories? How can we be followers of Jesus who was seen clearly by Peter and by Mary? How can we be people of faith who both follow a leader who is a rock on which we are steadied and a tower who lifts us all up? What if masculine and feminine were allowed to stand together as holy to the deepest core of our faith? What if there is a whole lot of space for both/and in our tradition!?!?

Someone actually didn't want that. Someone edited it out, and made Mary smaller. Dear ones, may we commit ourselves to the opposite. May we go out and make God, and each other, and all we meet BIGGER! Tower like, even. Amen

1 ALL THE MARYS Wild Goose Festival, Closing Sermon, July 17, 2022 by Diana Butler Bass https://dianabutlerbass.com/wp-content/uploads/All-the-Marys-Sermon.pdf

Rev. Sara E. Baron First United Methodist Church of Schenectady 603 State St. Schenectady, NY 12305 Pronouns: she/her/hers http://fumcschenectady.org/ https://www.facebook.com/FUMCSchenectady

May 21, 2023

#thinking church#progressive christianity#fumc schenectady#schenectady#umc#sorry about the umc#rev sara e baron#first umc schenectady#Diana Butler Bass#Wild Goose Festival#Mary the Tower#Mary AND Peter

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

For some reason this showed up in my recommendations. Well, @gaykarstaagforever, answer the following:

Why was anyone believing that Jesus had been born of a woman and born a Jew, killed and buried, descended from David and Israelites and having human brothers, one of whom was called James and Paul had met, just 20-30 years after Jesus was supposed to have existed, unless there was a historical Jesus? You're using false equivalences - Hubbard never claimed to have met Xenu's brother and The Prose Edda doesn't claim that Thor was swinging his hammer at giants just twenty-five years ago.

Why Paul claimed to have met Jesus' brother, who he holds up as an authority in the early Church, in a context when he was trying to downplay his acquaintance with other Christian leaders as much as possible, unless there was a historical Jesus?

Why did Josephus, the great Roman Jewish historian, mention both James and Jesus as historical figures unless there was a historical Jesus?

Why did Tacitus, one of the most cautious and reliable Roman historians, report Jesus as a historical figure without caveats or suspicions in a passage where he has nothing but contempt for Christians and Christianity, unless there was a historical Jesus?

Why do the Gospels all state Jesus was from Nazareth when Jews expected the Messiah to be from Bethlehem (Mark and John don't address the issue while Matthew and Luke say "yes, he was from Nazareth but he was born in Bethlehem, so there!") unless there was a historical Jesus from that town?

Why do the Gospels, with Tacitus again and probably Josephus too, all agree that Jesus was crucified, a horribly shameful death on multiple levels that had previously been universally seen as proof of a failed Messiah, unless there was a historical Jesus who died that way?

Can you think of a theory that accounts for all the above while being as parsimonious as or more parsimonious than the theory that a historical Jesus (not necessarily the Jesus of Christianity) existed?

And let's hear it from Bart Ehrman, Professor of Religion at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: "It is fair to say that mythicists as a group, and as individuals, are not taken seriously by the vast majority of scholars in the fields of New Testament [Studies], early Christianity, ancient history, and theology. This is widely recognized, to their chagrin, by mythicists themselves." (Did Jesus Exist?, 2012).

And what pressure is Bart Ehrman under to assert Jesus' historicity? His thesis is that Jesus was a failed doomsday prophet who never claimed divinity or expected crucifixion and the New Testament is historically and textually unreliable, and Ehrman is (checks notes) ... Professor of Religion at a top state university, author of several books promoting his ideas to a popular audience, and praised as a textual critic even by Evangelical scholars. Oh, he feels such an obligation to conform to Christian belief and is in so much academic danger if he doesn't.

Am I saying this because I'm a Christian? I'd be lying if I said I wasn't. But also because I really do care about accurate history, and I've made what I think are good historical arguments. And I'm not above going after misinformation on my side - look at the time I criticised young-earth creationism.

We have no evidence that Jesus was ever even a real person. Most historians just assume he was because "who starts a religion based on absolute fiction?"

And these are just some NEW stupid ones!

People have been making up stories and then threatening other people over them for thousands of years!

What I'm saying here is there is exactly as much material evidence for Jesus as there is for Apollo and Thor. But no historian's mother still believes in Thor. There is other shit going on here in the West with Christianity that compromises our ability to discuss it rationally.

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

Methods of Biblical Interpretation

This post summarizes the various methods scholars apply to Biblical interpretation as shared in Raymond E. Brown’s book An Introduction to the New Testament (abridged edition).

Historical Criticism aims to discern what an author aimed to convey with their text, and makes use of knowledge of a text's "historical origins, for example, persons, places, things, events, dates, sources, etc." (Brown p. 8). Brown claims that the attempt to determine an author's intended message is "fundamental to all other forms of interpretation."

Redaction Criticism (also called Author Criticism) recognizes how "writers creatively shaped the material they inherited" (Brown p. 9) and thus focuses on what those writers' interests and goals may have been.

Social Criticism "studies the text as a reflection of and a response to the social and cultural settings in which is was produced. It views the text as a window into the world of competing views and voices. Different groups with different political, economic, and religious stances shaped the text to speak to their particular concerns" (p. 10).

Rhetorical Criticism "analyzes strategies used by the author to make what was recounted effective," from organization of material to word choice.

Textual Criticism compares differences in manuscripts; while Structuralism focuses on the final of a text

Source Criticism tries to determine what sources a writer drew information from. When it comes to the Gospels, questions explored include, “Did the evangelists have sources from predecessors? Were these oral or written? Did one evangelist use as a basis another Gospel that had already been written?”

Form Criticism looks into the literary form or genres of a text (e.g. Gospel vs. epistle, or parable vs. miracle story)

Canonical Criticism looks at the bigger picture, at how one passage fits into the New Testament or entire Bible as a whole

Narrative Criticism concentrates on texts as stories, and "distinguishes the real author (the person who actually wrote) from the implied author (the one who can be inferred from the narrative)" (Brown p. 10)

Advocacy Criticism "is an umbrella title sometimes given to Liberationist, African American, Feminist, and related studies, because proponents advocate that the results be used to change today's social, political, or religious situation."

Finally, there’s the Overview approach, where a scholar combines multiple methods in order to “arrive at a much fuller meaning of the biblical text.”

#reading and studying the bible#biblical interpretation#hermeneutics#readings#log#spring 2022#updated to include source criticism cuz i somehow skipped it before

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

so jews often interpret it as being a pomegranate bc theyre a common fruit in western asia so would have been around during the time the torah was compiled; there's also a lot of ancient myths around pomegranates (like the persephone myth) and imo its just a prettier fruit that looks nicer in art than a boring apple and jews identify with it more as judaism began in the levant. there's not any textual basis; like i said, the hebrew of genesis just says "פרי" which just means fruit and not anything specific. there's nowhere in the tanakh, from my knowledge, where any specific fruit is mentioned. the apple, like i said, is due to a latin pun/homophone that popped up in the vulgate and lingered in the popular imagination.

in terms of other jewish interpretations, there were rabbis in the talmud who proposed that it could have been wheat, a fig, grapes, and apparently a banana. wheat is due to a couple of things including a pun in hebrew involving the word for sin, the fig was because of the fig leaves adam & eve covered themselves with and because figs are a common gynic symbol, the grape is bc of what i said in a previous ask, and the banana was bc of either maimonides thinking bananas were healthy (he was both a reknowned rabbi and a doctor for his community; he's probably the most well-known rabbi of all time as well) or because it was a popular belief in syrian & egyptian jewish communities, though i cant find a specific citation for an english translation (maimonides' more secular texts are far less easy to get in translation). i got all this info off the wikipedia page and from my previous coursework in jewish food traditions.

also as a note from what you said in your original post about canon-- you're right that just bc a text isn't considered canonical doesnt mean various traditions don't use it; there are many texts noncanonical to judaism and christianity that jews & christians use to discuss customs, histories, and translation. so looking into the book of enoch as a way to consider how previous generations of interpreters were looking at genesis actually makes a lot of sense, but in terms of a theological argument would be less significant than evidence from a canonical text, if that makes sense, though my understanding is even in the new testament there isn't any particular fruit considered to be the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, so this is a pretty good place to examine past interpretations

(this is so fun! i love doing comparative studies)

can you imagine how difficult a pomegranate would have been if it was the fruit 💀 like did the serpent split it open or did eve like- 😭 and then they’d have to pick out the seeds to eat them. being serious though there really isn’t enough evidence to figure out what specific fruit it was. fun to discuss though, thank you for sharing your knowledge with me!

#pomegranate is definitely more aesthetic in art though so that’s based of them#personally i really like the fig also#fig is always a fruit i’ve associated with the bible#asks :d

3 notes

·

View notes