#But when you speak of a general singular “you” it's usually masculine because it's still the default.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

You mentioned in tags some cultures have genders that don't align to the masc/fem - can you tell us more about that, and if any of our characters use these system(s)?

Hey there!

The non-standard gender systems I have for the Redux, sadly, won’t get a ton of limelight apart from the occasional off-hand mention. Not because I don’t want to include them, but because I wasn’t sure how to include them in a way that wouldn’t be off-putting to readers. Old Vale’s gender system is probably the most…unconventional of the lot.

None of the main cast (or any minor characters) at the moment use the more unusual gender systems I’ve come up with. They’re all presented as either male, female, nonbinary, bigender, genderfluid, or genderqueer, as we would understand those terms.

That aside, I’m still happy to give an overview of each kingdom’s take on gender.

Atlas’ is probably the most bog standard—it has a masculine/feminine binary, derived from the system used by Old Mantic settlers (who were descended from the Matsu people of Northern Anima). That being said, Atlas arguably has the most extreme adherence to gender performativity, given that the country tends to skew more conservative. Behavior, appearance, speech, and the like are strongly dictated by cisheteronormative expectations, particularly amongst Atlas’ upper class. As a result, the people of Solitas (which include Atlesians, Mantese, and Evadnine) generally have disproportionately exaggerated expressions of gender when compared to other countries. It’s something that I plan to explore more in-depth with characters like Weiss, Willow, May, and Watts as the story progresses, seeing as they all have very strong opinions regarding their culture’s value system.

Mistral’s gender system is a binary as well, but it has two “models,” so to speak. But before we go any further, I need to quickly clarify something:

Social gender is an identity ascribed to people, usually packaged with corollary traits.

Grammatical gender (sometimes used interchangeably with noun class) is a division of linguistics that categorizes nouns in relation to other aspects of language, such as adjectives, articles, or verbs.

Sometimes there’s correlation between the two, and sometimes there isn’t. In Spanish, for example, el hombre (man) is a masculine noun. The grammatical gender reinforces the culturally-associated semantic one. However, la hombría (manliness) is a grammatically feminine word, despite being a concept tied to masculinity.

It’s not surprising, then, that grammatical gender and social gender get conflated from time to time.

As for how this relates to the Redux—at one point Mistral had a social gender binary that was culturally synonymized with its grammatical gender. And the nouns of Old Mistrali-Mantic (the protolanguage of the Animoigne language family) weren’t categorized by masculinity or femininity. Instead, its nouns were divided into categories based on animacy (to what extent something is considered sentient/alive).

This means that, effectively, Mistral’s people were at one point monogender (that gender being geyl, “alive”). Distinctions like “masculine” and “feminine” didn’t really exist, outside of borrowing those concepts from other cultures. Old Mistrali-Mantic had words for things like “person who gestates” and “person who sires,” but those terms had no actual bearing on a person’s identity, or how they expressed themselves. They exclusively referred to biological sex, not gender. (And yes, animacy extended to pronouns, too. Old Mistrali-Mantic had four third-person pronouns, two singular and two plural. Imagine if English had two versions of it and they, and they were used to communicate whether or not the subject was alive. That’s basically the gist of it.)

Over time, however, as the Kingdom of Mistral conquered its neighbors across Anima, it began to assimilate them. This cultural exchange was a two-way street, though, and some of the nations that it annexed did in fact have masculine and feminine genders. As the Mistrali Empire grew, masculine and feminine genders caught on, and gradually supplanted the older non-grammatical animacy genders.

Animacy is preserved in several of the daughter languages in the Animoigne language family, as noun classes. But people in Mistral no longer identify as geyl. Nowadays, the default is either male, female, or (rarely) nonbinary. *

In the modern day, Mistral sees masculinity and femininity as a spectrum, with nonbinary being closer to androgyny. Something like this:

Vacuo, on the other hand, sees gender more like this:

And even then, the way that Vacuo deals with “conventional” gender (masc/fem) is odd, too.

See, in Western society, when we talk about people being nonbinary, we typically mean that their gender falls outside of a binary—masculinity and femininity.

In Vacuo, masculinity and femininity exist as part of a ternary system, with a third distinct gender that has no point of easy comparison to anything in our world. (I’ve been calling it “neutral” for lack of a better word, but really, it doesn’t quite work. “Neutral” implies having no strongly marked characteristics or features, and calling Vacuo’s third gender neutral would be like calling masculinity neutral. Because it absolutely does have its own unique qualities and associated traits. Alas, “neutral” will have to do for now.)

Someone who identifies with a gender outside of those three would be considered nonternary (as opposed to nonbinary, which would be the not-quite equivalent). Thus, Vacuo technically recognizes four categories of gender—masculine, feminine, “neutral,” and any gender that isn’t part of its traditional three.

Vacuo’s also a lot more culturally accepting/permissive of genders from other nations, and it doesn’t begrudge how people identify or express themselves. Vacuites are a relatively chill bunch.

And last but not least, Vale. The kingdom whose gender system started this entire discussion, and by far is the weirdest of the four.

Similar to Mistral of antiquity, Old Vale didn’t recognize male or female. Its genders—of which there were eight—were tied to a different culturally-valuable element: the seasons.

And for every one of Vale’s eight genders, there was a corresponding season that matched.

Eastern Sanus experiences four yearly divisions, reckoned by solar, astronomical, and meteorological phenomena. These are winter, spring, summer, and autumn, known in Old Vale as the “material seasons.” The material seasons have fixed calendar dates.

The other four are classified as the “liminal seasons,” or maidentides. Unlike the material seasons, maidentides don’t have fixed calendar dates. A maidentide could be more concisely described as the ephemeral, transient blurring of two seasons—when the temporal boundary that separates them is vague, evidenced by qualities of both the retreating season and the oncoming one superimposed upon each other. The summer-autumn maidentide, for example, is characterized by days where the oppressive humidity and heat of summer cling to the air, even as the foliage turns shades of brown, red, and yellow, and the leaves begin to fall.

In Old Vale, it was customary for a child’s first gender to be assigned to them based on the season they were born in. The genders paralleled the transient nature of the seasons by allowing people to freely transition between them, just as the world shifts between seasons. A person’s gender didn’t have to match the season they were currently in, either—as in, a person with a spring gender wouldn’t be expected to change it to a summer gender as May turned to June.

Interestingly, Old Valin cultures wouldn’t have recognized being cisgender or transgender, because gender transition is the default for their model. They did, however, have something sort of analogous.

Rather than there being cis- or transgender individuals, you had what were known as static and fluid individuals. Fluid individuals were those whose gender identity wasn’t rooted in a single season, and could freely move between them as wanted or needed. A static-gender person, by contrast, was someone whose gender was immutable and “locked in” to a single season, and who was relatively confident that the season they identified with was the only one that could fit them best.

The season genders of Old Vale originated in the mountain range of eastern Sanus, the Cirithel Mountains. In the present day, they’re more or less exclusively confined to that area. When some of the population split off centuries ago and migrated toward the western coast, they ended up ditching their gender system in favor of one similar to Vacuo’s. Unless you’re travelling to the city of Gyden, then you’re unlikely to encounter someone who identifies as one of the season genders. It’s estimated that those culturally-endemic genders will disappear within the next century or so.

Obviously, in a world as culturally diverse as Remnant’s, there would be multiple gender systems besides the ones I talked about. But truthfully, I haven’t had the time to develop any others beyond the aforementioned four. Hopefully what I wrote managed to answer your questions!

-

* There’s one exception to the animacy pronouns, and it’s not a particularly nice one. When Mistrali racists want to dehumanize Faunus, they’ll refer to them using the inanimate pronoun siþ. The animate pronoun geyl is used for people, so when someone uses siþ, they’re basically stripping a Faunus of their personhood by reducing them to the status of something non-living.

Addressing a Faunus as siþ would be like calling them an “it.”

#asks#anon#i speak#worldbuilding#queer discourse#gender#gender systems#languages#conlang#queer meta#queer meta asks#meta content

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Write Non-binary Characters: Part II

Visit PART ONE: the basics first!

PART TWO: the nitty gritty.

Non-binary in relation to Presentation.

What are we talking about here when we say presentation?

Presentation in relation to gender is how a person chooses to look, dress, and act in relation to their culture's gender norms. A person who wears dresses and makeup, speaks in a higher pitch, and daintily crosses their ankles is presenting in a feminine manner in most Western cultures because these are traits labeled as feminine in these particular cultures.

As mentioned in part I, non-binary people may choose to present themselves in many different ways.

Androgynous. The androgynous presentation (i.e. a presentation that is between masculine and feminine, presenting with traits ascribed to both) is commonly associated with non-binary people. Some non-binary people present as androgynous because it feels most natural to them, while others present as androgynous because it helps to inform the rest of the world of their gender.

Masculine or Feminine. Many non-binary people present as masculine or feminine despite being non-binary. They may present this way because they enjoy it and it feels natural, or because they grew up presenting that way and don’t have the time or means or desire to adjust, or because their best efforts would not allow them to present as androgynous without extreme measures they don’t feel the desire to undergo. But whatever the case, non-binary people who present as masculine or feminine are just as non-binary as those who present as androgynous!

A mix of presentations. Some non-binary people will mix up their presentation, either based on their mood, or on how they feel about their gender at that moment, or to keep their presentation similar around a specific group of people (such as work vs friends). This can mean presenting as masculine sometimes and feminine other times, or as androgynous sometimes and masculine or feminine others, or a mix of all three. This switch may happen in relatively even amounts, or the person may wish to usually present one way and on rare occasions another, or anything in between.

A word on gender dysphoria: non-binary people may or may not experience gender dysphoria (i.e. a feeling of unease or distress because their body does not match their gender identity). For non-binary people, this generally takes the form of wanting to be more androgynous. Whether or not a non-binary person experiences any dysphoria does not make them “more” or “less” non-binary. It is not in any way a qualification of non-binary-ness.

A word on gender nonconformity: Just because someone is gender nonconforming does not necissarily mean they are non-binary. Many binary queer people choose to present in ways that don’t conform to gender norms, and they have every right to do so. Sometimes gender nonconforming people are trying to decide whether they are truly binary or not. Whether they decide that they are binary, or non-binary, or trans, or make no decision at all, this is a perfectly respectable way to explore one’s gender.

Non-binary in relation to Pronouns.

Pronouns are often used as a linguistic form of gender presentation and designation. Most people relate singular they/them pronouns to non-binary people—and often non-binary people do use they/them exclusively—but there are many combinations and ranges of pronouns non-binary people choose. Let's go over some common options:

They/them, exclusively. They/them have been used as singular pronouns since the 14th century, and are already a popular way to refer to a person of unknown gender. They/them is often used by agender and bigender people, but as with all pronouns, may be claimed my anyone of any gender, including binary people who feel they/them if the best portrayal of their gender identity.

He sometimes, she other times. Transitioning between two or more different pronouns based on how someone is living their gender in the moment is very common for gender-fluid people. Just like with presentation, this exchange may be equal or it may be weighted heavily to one pronoun over another, or anything in between.

Binary pronouns, exclusively. Some non-binary people never feel the need to switch from the pronouns they were asigned at birth, while others feel they fit the binary pronoun opposite the one asigned them at birth. Some also choose to keep their original pronouns in order to avoid coming out to transphobic people. This is no way makes these people less non-binary than non-binary people who choose any other set of pronouns!

Multiple pronouns. People from all non-binary identities will commonly choose to go by multiple pronouns simultaneously. This can be because they feel close to all those sets of pronouns, because they have no desire to choose a specific set, or because they don't feel the need to give up the pronouns they were assigned at birth in order to take on new pronouns.

Note that this is the one situation in which people might have preferred pronouns. (If someone chooses a single set of pronouns, those are their pronouns! It's not a preference—it's a part of who they are.) But people who have chosen to go by multiple pronoun sets might have one they prefer to be called, especially in a particular setting. For example, a non-binary person might say "I prefer to go by they pronouns at work, but I also identify with and accept she pronouns, so I won't be offended if customers routinely use those for me."

New pronouns. Now that the non-binary community in western culture is finally coming together, there are new sets of pronouns being created specifically for non-binary people to use. There are infinite options here, one of the most popular being xe/xir, but they're still the least claimed pronouns due to most of society not being familiar with them.

It/its pronouns. While some people have claimed it/its pronouns and there are situations where it/its pronouns might accurately fit a character, its best to leave those stories to non-binary and trans writers, due to the long history of it/its being used to dehumanize trans people.

A word on gendered terms: the non-binary community interacts with gendered termanology (such as Mrs., brother, dude, gal, queen, gentlemen, sir, etc) in the same way as they do pronouns. Many non-binary people have certain gendered terms they accept, while some accept all and others accept only genderless terms. These accepted terms may match with their pronouns (e.g. someone who uses he pronouns also using masculine terminology, like mister, sir, brother, dude, etc) or may not.

Now that we have all these cool pronouns, how do we relay this information in our writing?

There are a few common techniques to help relay character pronouns in writing:

The Mind Reader's Way. Let your point of view characters just happily know what everyone else's correct pronouns are all the time so you can move on with the story and not have to sit down for awkward conversations. It may be unrealistic, but should not break suspension of disbelief for anyone who genuinely wants to read about characters from non-binary genders going on fun adventures. Keep in mind that this works best in societies where characters only use one pronoun set.

The Introduction Path. Have it be customary for characters to introduce themselves by stating their pronouns, and call all characters by they/them pronouns until they do so. This lets the story move forward quickly, but can be awkward if you have primary characters (such as villains) who never introduce themselves to the point of view character.

The Everyone's Friends Route. Have there conveniently always be someone else who knows that character's pronouns and can slip them into conversation.

The Pronoun Pin Road. Much like pronoun pins, include a piece of world building into your setting that culturally requires people to wear something particular relaying their pronouns. This works best either in a modern or futuristic setting where characters can wear actual pins/shirts/etc, or a secondary world where you can control all aspects of the culture.

The Coming Out Highway. The most awkward but most realistic option is to force your characters to explain their pronouns if they don't fit society's strict gender norms. This can be as simple as one character asking "sorry, I don't mean to bug you, but what pronouns do you go by?" or another character arriving to the second day of class in masculine clothes and announcing "I go by he/him pronouns today."

Whatever route you choose, make sure to be consistent throughout the story.

Part Three: Common Pitfalls and Easy Fixes.

#writeblr#enbie characters#writing non-binary characters#writers on tumblr#authors on tumblr#writing help#writing advice#writing lgbt characters#writing resources#writing tips#writers on writing#amwriting#creative writing#writing tag: characters#character tag: lgbt characters

884 notes

·

View notes

Photo

More Spooky.

Mixing the spooky prompts of 'gay vampires' and 'all dressed up for a spooky soriee' again.

This is Salt. She's pretty good a putting people back together, is full of leeches, has a dark sense of humor, and is very short. She's also as gay as a hermaphroditic leech person who mostly uses she/her for convenience but has no strong feelings about gender can be.

She grew up around pit fighters and eventually became a medic when her own career didn't work out (her eyes were always wonky but then she had to grow a few back after That Fight and yeesh). When the pits got shut down one of the older medics decided to put an actual practice together and hit the road, taking Salt and a few other favorites with. Eventually they got pretty successful and opened a lot of non-human friendly hospitals. She's currently attending a 'children of the night' themed benefit sponsored by Cashmere's company as a representative since her boss couldn't make it.

Here's a bunch of lore about the kind of vampire she is because of course I wrote some:

Hirudo Vampires

What are they: A race of Mermaids. Mermaids that are essentially a sack full of leeches, but yeah. Mermaids.

How they’re made: They’re born like any other mermaid. Weird humanoid monotreme lays an egg and after a bit you get a Child. Infants look like regular baby mermaids with kind of sluggy tails and can be confused with nudibranch juveniles if they’re gifted with brighter colors. They’re initially fed milk and invertebrates like worms and slugs by their parents but quickly move on to blood once their cravings start and they begin releasing leeches.

Turning: They can’t turn people. They can turn leeches but they rarely do because usually more than enough leeches naturally sprout from their innards and outside leeches that aren’t from another hirudo are a quick fix that will eventually be rejected by their bodies and need to be replaced.

Feeding: Their favorite method is anchoring their tails to something in a body of water, releasing their leeches, and just floating there until they return. When the leeches come back they swim into the hirudo’s body and plug themselves back into the digestive tract where they empty themselves over time. When the last leech runs out it’s time to go hunting again.

When not feeding they fill the inner cavity of their body with water for the leeches. Chemicals in this inner cavity thicken the water into a loose slime and when feeding all that Leech Slime gets released so that they take on more of a flesh suit aesthetic. A view of this feeding form is rare however, as hirudo hide while feeding and only have to feed this way once every few months if most of their leeches are successful hunters. If they’re not so successful or they can’t send them out for whatever reason they supplement their diet with invertebrates, soft organ meats, and ingesting small quantities of iron whenever they can. Mostly by nibbling on rusted objects or sucking on found bits of metal like jawbreakers.

Besides blind hunting they’ll also enthusiastically feed on willing subjects. Hirudo are renowned healers and their bites can ease certain ailments just like regular leeches. They can can greatly increase their healing powers through training and even imbue their leeches with specific healing spells by lightly carving said spells into their flesh. If you come across an aquatic apothecary or river-side hospital outside of human territories, they’re likely to be owned or staffed by hirudo. When healing others, singular leeches are selected and expelled for each patient. Dedicated healers tend to be larger than regular hirudo since their constant food source helps them produce more leeches.

Powers: Calming aura (to be fair the leeches have this power, not the hirudo), two or three times the strength of an average human (that’s normal for any mermaid though, they’re pretty much all pure muscle), durability (very hard to kill if they can get water and a blood source), and accelerated healing. They can direct their leeches to specific targets and use them as kind of detachable limbs, even speaking through them if they need to. Mostly they just point them in a general direction and see what they can get. The leeches have their own simple brains and can figure it out.

Fun Facts:

Bites don’t hurt and rarely become infected unless you’re just rolling around in garbage all day. You don’t bleed more or less than you would after a regular leech bite and if the creature doesn’t see the leech they probably won’t know they’ve been fed on until after it’s gone.

They can hang out on land just fine due to being their own personal swimming pools but they still dry out after a day or so and need to return to the water. While on land they develop a thin layer of mucus on their skin that isn’t sticky or wet but you can feel it creepily shift under your hands if you grab them too roughly and it gives them a shimmery glow. This layer flakes off if they become dehydrated and some harvest it as well as any spare Leech Slime for use in beauty products and skin ointments.

They can ‘walk’ on land but it’s draining after a bit and they all use canes and/or wheelchairs to get around.

Just like regular leeches, hirudo are hermaphrodites. What we think of as feminine or masculine appearances are just the product of different family genetics interacting with environmental stimuli and are the same as tribe markings to them. Come from a southern river system where your egg was kept in warm water? Guess you’ll grow up to look more femme and you get cool orange stripes. This situation isn’t unheard of in mermaids but land creatures can be taken aback. It’s whatever. Biology does what it wants.

Many name their leeches and get real mad if one is killed. Partially because anyone would be mad if you murdered one of their organs, but also because they like those little buddies. Luckily, they’re pretty hard to kill if they’re in water and they can get back to the main body.

Most physical fighting is done with leeches. All hirudo have at least one leech that’s bigger, tougher, and honestly creepier than the others just for combat situations. They vary a little from person to person but a consistent trait is that they have just. Too many teeth. Too many teeth that are sometimes not in the right places and sometimes look too human. Just a lot of Wrong Teeth on a big fat blood slug. If this ‘attack leech’ dies or doesn’t return to the body in a certain period of time then they start growing a new one immediately and oh boy is the new one always worse that the last one. There are hirudo out there housing some real abominations.

Combat Leech is their secondary defense mechanism. The first is expelling slime at predators and slipping out of their grip by furiously stretching and wriggling.

The leeches aren’t like wild leeches. They don’t digest the blood they take or make more leeches. They’re also strangely warm, like little hot water bottles. It’s hard to even call them leeches since they’re really detachable organs that act like leeches but like. What else can they be called? Idk, but there’s strong evidence that wild leeches find them creepy and will avoid them.

They’re very amused at the human perception of boobs because to them bigger titty is like a sign that says “I have fat to spare because I eat very well and that means I could probably rip you to shreds”.

They can produce children with other humanoids in theory but it’s a toss of the coin for the egg’s viability and it’s suspected that this is how vampire genes get thrown into non-mer family lines so like. Not a great idea if you don’t want to chance giving birth to some draculas!!!

They can fit through any space their head can fit into. They kind of navigate the world with octopus/cat vibes. Their arms are even more tentacle-y that classically arm shaped.

Eight to ten eyes with position and number differing by tribe.

On average they’re about 5-5.5ft long but powerful hirudo with lots of leeches can get 8ft+.

They’re actually known as some of the prettiest mermaids by humans.

Humans are some of their favorite prey.

Most biologist feel like this isn’t an evolutionary accident.

Immortality?: Hirudo can live for around three hundred years in perfect conditions but they’re not immortal, they grow old and die like anything else. Immortality in not out of reach for those able to push a few morals aside however, and can be accomplished two ways:

1. Feed exclusively on other hirudo. This is an asshole move for obvious reasons and can be done by consuming their leeches or going old school vampire and drinking right from the source. Can be killed if they’re dehydrated through aggressive salting or imprisoning on land for months.

2. Necromancy is just very advanced healing magic really. Carve enough arcane magic into your tummy buddies and you got yourself a real Leech Lich situation brewing. These hirudo can only be killed by thoroughly destroying all of their leeches.

#vampire#hirudo#salt#mermaid#body horror#small guide#that outfit went though a lot of alterations but i love the final so much

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s only after their mother dies and they get in contact with the first, unfriendly, demons that Inuyasha finds out that the human’s obsession over fitting everyone in one gender it’s weird for them too. They have already learned to keep quiet about what they think about themselves. What their body is, and isn’t, to them, they don’t tell the humans in the castle. Inuyasha doesn’t even tell their mother.

It has been a few years since they stopped living in the castle, when they have again the occasion to meet an human, on a moonless night. That particular one, as every other, is immediately concerned with their appearance, assuming their gender without even letting them speak.

Inuyasha doesn’t feel particularly attached to one nor the other, on a good day doesn’t even think about it.

(On a bad day somebody just has to remind them, usually while trying to kill them, and aren’t they lucky?)

They don’t go near another human settling for years after that night. Those are safer than the forests and fields, at least when they are weak, but they don’t have it in themselves to deal with stupid humans and their stupid way of thinking.

In a way this hurts more than being half breed. Their mixed heritage is on plain sight for everyone to see, and there is no mistake to be made (with the exception of one night per month): one look at their ears and the story of their birth is on plain sight for everyone to deduce.

But the way humans expect them to adapt to their roles, to dance to this tune they don’t fit in, just after one look at their body, that’s worst. Humans and demons alike hate them for their blood, but both of them just ignore how they feel about their body. It’s just irrelevant.

So Inuyasha makes sure that it’s irrelevant for themselves too. In any case they don’t even have the words to explain it, so why bother? It’s not like they have someone to tell, and the most important thing right now it’s to survive.

They never get around telling Kikyo about this too. She barely accepted their mixed blood, Inuyasha is not sure she can take more. They don’t want to take the risk of another rejection. As for the sacrifice they are willing to face, it’s not that different from the other one they already accepted to make when she asked, just another part of their identity they will have to renounce to.

Kagome is strange. She doesn’t question them and the way they present themselves, doesn’t even seem to notice. The girl has bigger problems anyways, it’s her fault if them both are on this quest. But she always looks at them with a bit more intention when they slip, in the way they refer to themselves, when the hyper masculine terms they use out of habit, to comply with the image others have of them, to not raise questions, get stuck in their throat. She always notices.

She asks one night, when everyone else it’s sleeping. They have just met Sesshomaru again and Inuyasha is quite proud of their victory, even if in reality the bastard run away just before Tessaiga could break definitively. Inuyasha still counts it as victory.

“It’s something that I have noticed before, but why did he refer to you with neutral terms?”

The asshole has never had anything to say about their gender obviously, as it’s normal for a demon, but Inuyasha doesn’t really want to explain to her. They huff and try to dismiss the question with a vague gesture and a “whatever” but she just keeps waiting patiently, peering at them from under her eyelashes. They both know that the answer it’s not simple, and the question is bigger than it could look to a mere bystander.

Inuyasha takes a breath. She has been on their side for a while now, and they don’t want to lose her. But at the same time she has already told them how irrelevant their mixed blood is for her. No. Not irrelevant. A part of them. Just a part of who they are, as normal as their hands and eyes, something that makes them THEM. If she could accept that, then maybe, just maybe…

Inuyasha doesn’t know how to explain, but Kagome is patient. It’s like a flood. When dawn comes, and, how? When? She stops them, shakes Sango awake and quietly informs her that she and Inuyasha are going back to her time. She then calls for Inuyasha and they start walking away from the camp. As soon as they are out of ears’ reach, she resumes the conversation.

She looks among books and books in the public library. Inuyasha just stands aside, the hat flattening their ears, trying not to draw attention and not to be in her way. They didn’t even stop to her house to say hi to her family, she knew she didn’t have anything of what she was looking for there.

“There must be something! I have read a couple of things but I cannot remember where I found them again!” she looks possessed, and Inuyasha is not going to bother her.

She comes up with a few books and articles from magazines, and is eyeing critically the huge computer in the backroom, pondering if to search on that too, since the Higurashi family doesn’t have one.

Inuyasha is not really listening to her. They are scrolling through the written text, trying to make good use of what little reading abilities they have, and to interpret the futuristic language and culture. Their worldview is being thrown off right now.

If for demons gender (and now they know the difference between gender and sex, and gender expression too, isn’t that neat?) is inconsequential, humans 500 years in the future keep spending a lot of time thinking and talking about it. Still, the revelation is another one. Demons don’t care about gender, you can’t use it against them. Humans don’t care too, they know where they fit and it comes natural to them to abide the unwritten rules that concern the sociality. Despite this, here Inuyasha gets a glimpse of another world. These books give them a place, among others, give their struggle a name and a reason and companionship. They are not the only one. There are humans too, here, going through something that might, with a stretch of imagination, be considered similar to their experience.

Kagome takes some books back home, essays and narrative ones, and some vhs to see on the television. Her family is nowhere to be seen and they are back to her room. Inuyasha feels safe there, the day has already been a mess, and their head is still spinning. “I don’t know where to look for more, but we need to understand better, honestly Inuyasha, why didn’t you speak sooner?”

They know her temper is without fire, that she is just worried, but it hurts the same. She must see their look, the flattened ears, because she backtracks immediately. “I’m sorry, I can understand why, it was a stupid thing to say. It’s just… I want to help. I would like for you to tell to the others too, but it’s your call. I’m sure they will want to understand though. That’s why I need to find more…” she is off again, checking on the list she compiled while looking for materials, and Inuyasha watches her go in the direction of the stairs and the living room, still shell-shocked.

“I didn’t even ask you!” She seems to have realized something, her voice still audible from the other room “I’m so bad at this, I’m sorry! Which pronouns should I use?”

Inuyasha can’t help the laugh that escapes their lips, they don’t know what to answer. But they will find out. There are words out there for them, just waiting to be discovered. Their experience can be told, and damn them if they are not going to.

—

A disclaimer: I am a cisgender woman, so my knowledge and undersanding of genderqueer identities can only be a secondhand one. This to say that I hope that I have not offended anyone with this depiction of this identity, and if I have I am deeply sorry, since it was not my intention.

For something so short I really had trouble writing this. First my native language doesn’t have the option of singular them, and I never had any occasion for using it before, so I’m sorry if I made mistakes. Second, Inuyasha the character, in the anime, while referring to themselves, uses Ore, an highly masculine way of saying me, and I didn’t want ignore canon completely even if I played fast and lose with the timeline, since I don’t remember what happened when. Additionally, and I never looked into the language so I’m not sure, I suspect that there are A LOT of pronouns whit different nuances in the spectrum between masculine and feminine in the Japanese language. So I had to take in account three language shifts while writing this tiny little thing. I’d like to add that while il like to think that my personal knowledge on transgender and genderqueer identities is not that bad, I haven’t the faintest idea of what 199something Japan might knew about it, so I kept on the conservative side (considering they are still a really closed off country about LGBT+ issues, I feel that it’s the most realistic portrait)

I cannot help but think about Inuyasha and a nonbinary or genderqueer identity. Assuming that for demons gender is something much less regulated by social norms than for humans, and that because of their upbringing Inuyasha didn’t get to receive a positive and validating explanation of gender and sexuality by none of the two cultures, I suppose that (in the feudal era!) it would have created in them an even higher sense of isolation and oddness. That’s probably why I love the idea of Inuyasha going to the pride for the first time (first gay pride in Tokyo was in 1994…) and in general realize that they are not alone.

It is a deeply difficult and isolating situation, not having the words to describe, even to ourselves, our identity, and I am happy that the modern ways of connecting with each other are lessening this kind of isolation.

this was written for day 5 of @inuyashapridemonth2020

#inuyasha#inuyashapride2020#my art#my writing#ops#I wrote something again#inuyasha pride month#nonbinary inuyasha

81 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi I’m here from looking at @xenogender-culture-is just wondering what pronouns do you use when you’re xenogender?

Hi! Thank you for coming to this blog for advice. We've gotten a lot of questions on that other blog and unfortunately we usually can't answer them there, since they clog up everyone's feed. Thankfully your question has a very simple answer: anyone, regardless of what gender they are, uses whatever pronouns they want to use!

Pronouns are, grammatically speaking, just words that refer to you and replace your name, almost like mini names. Typically certain pronouns are associated with a certain gender, like how he/him is generally considered the "male" pronoun set, but anyone can use any pronouns they want! A lot of lesbians, for example, use he/him pronouns to express their gender nonconformity. Men can use she/her pronouns, too, and anyone can use they/them or neopronouns if they want. Everyone just picks the pronouns they like the most or that make them the most comfortable, and that's different for everyone, including xenogender people.

You may still notice, however, that a lot of xenogender people use neopronouns. If you don't already know, neopronouns are pronouns that are considered outside of the standard pronoun sets for a language, and are usually newer and coined more recently, although this is not always the case. The standard singular gender pronoun sets in English are he/him, she/her, and they/them, so any pronouns that aren't those three are considered neopronouns! (Examples include xe/xem, fae/faer, etc.) A lot of xenogender people like to use neopronouns because they are completely outside of the realm of gendered language entirely, just like xenogenders typically are. Xenogenders are genders that falls outside of typical conceptualizations of gender and gendered language, and neopronouns for many people serve that exact same purpose. He/him carries an implication of masculinity, she/her carries an implication of femininity, and they/them carries an implication of gender neutrality. For people who want to avoid all gendered language or implications completely, neopronouns can be very helpful! (This isn't their only use, however. Some people use neopronouns just for fun, creativity, or self expression, and all of those uses are valid.)

We hope this helps answer your question! Thank you for asking so politely.

[ID: A DNI banner. It says, “Read our BYF/DNI before interacting!” on a background of the xenogender pride flag. /end ID]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English Language

While I know a lot of linguists who are feminists, there is some tension between feminist ideals and the anti-prescriptivist approach that linguists take towards language. Linguists, as a general rule, aim to document and examine language as it is used, without providing their own opinions on how they think language should be used. This approach to language allows linguists to show that certain forms of language, from split infinitives to singular they, are not bad or wrong or “grammatically incorrect.” However, when it comes to sexist language, it’s a lot harder to say that there’s no such thing as “bad” language use.

Some of the questions that arise are easily answered. It is fairly easy to distinguish between using slurs and splitting infinitives, as slurs are meant to hurt or disparage people, while split infinitives only offend the sensibilities of some long dead men who desperately wished English were more like Latin. But what about less malicious language use that still has sexist undertones? What about calling ships or storms she? What about using the word guys to refer to groups that contain women?

I thought a lot about this contradiction while reading Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English Language by Amanda Montell, a book that attempts to cover a wide variety of topics related to language and gender. Montell’s background in linguistics admittedly isn’t particularly extensive—she has a bachelor’s degree in linguistics, but she’s primarily a journalist who only occasionally writes about linguistics. (I should probably also state that, depending on how you count my graduate work in a related field, I have the same amount of linguistics education, so I’m not going to make any judgments on who “really counts” as a linguist.) That said, Wordslut is definitely a linguistics book—and a pretty good one at that.

Wordslut covers a broad variety of topics in sociolinguistics. Some are expected. The first chapter discusses the variety of (often derogatory) slang words used to describe women, while another chapter discusses the ways women speak to each other. Other chapters cover topics I see less frequently. One chapter, for example, looks at how women swear, while another looks at the vast array of slang words used to refer to genitalia. (I’d warn you that this book is NSFW, but if you’re reading a book entitled Wordslut at work in the first place, you’re a braver soul than I am.) One of my favorite chapters focused on how gay people speak, including both discussions of gay slang as well as examining why there’s a “gay voice” but no real “lesbian voice.” While I already was familiar with some of the topics in the chapter, I was not aware of Polari, a sort of code once used by British gay men as early as the 1500s that gave us such words as twink, camp, and fantabulous, and now I definitely want to know more about it. On a similar note, throughout the book, Montell makes sure to discuss queer, trans, and nonbinary experiences when relevant, which provides perspective that’s usually lacking in older writing about language and gender.

I did find that the quality varied from chapter to chapter—or even within the same chapter. Consider, for example, the chapter on catcalling. One section of the chapter compared catcalling behaviors with linguistic studies on compliments, breaking down precisely why catcalling is not a compliment. I thought this was a really interesting analysis, but I found the rest of the chapter fairly dull; some of it discussed facts I (and most other feminists) already know about how men dominate conversations and interrupt women, while other parts talked about the act of catcalling more generally. (A problem I found throughout the book is that Montell sometimes chose to discuss general feminist issues without really tying them back to linguistics.) While some of this unevenness is to be expected in a book with such a broad scope, one pattern emerged: I generally enjoyed the portions discussing how women speak, such as the chapter about conversational norms in groups of women or the section about the many uses of like, more than the portions discussing how women are spoken about. Perhaps this is because the former read like a celebration, while the latter was more of a rant. Montell is not happy about how our culture talks about women, and while I don’t disagree with her, I often found myself more frustrated than properly fired up.

It is worth noting that Montell is not an impartial voice throughout the book. She wants our language to become more equitable. Mostly, her ambitions are good. (And in her defense, she notes that certain approaches to making language more equitable, such as attempts in 70s to create a “women’s language” or storming a dictionary headquarters to demand the word slut be removed, are unlikely to be successful.) But in doing so, sometimes her own linguistic biases shine through. Consider, for example, an anecdote from the intro of the book, where Montell gives the following speech to a woman who critiques her use of the word y’all:

I like to see y’all as an efficient and socially conscious way to handle the English language’s lack of a second-person plural pronoun. I could have used the word you to address the two girls, but I wanted to make sure your daughter knew I was including her in the conversation. I could also have said you guys, which has become surprisingly customary in casual conversation, but to my knowledge, neither of these children identifies as male, and I try to avoid using masculine terms to address people who aren’t men, as it ultimately works to promote the sort of linguistic sexism many have been fighting for years. I mean, if neither of these girls is a guy, then surely together they aren’t guys, you know?

It’s a nice “take down the prescriptivist” story in some ways, but while I agree that y’all is a perfectly acceptable and useful word, Montell tries to argue that she chose to use y’all not just because her geographical and linguistic background make it the natural choice for her but because it’s the best choice, thereby turning an anti-prescriptivist argument into a prescriptivist one. Later in the same speech, she dismisses the option of using the pronoun yinz because it “doesn’t roll off the tongue nicely.” I’m more intrigued, however, by her insistence that it would be sexist to use you guys. Montell notes, “Many speakers genuinely believe guys has become gender neutral. However, scholars agree that guys is just another masculine generic in cozier clothing. There’d be no chance of you gals earning the same lexical love.” However, she provides no real evidence that guys isn’t truly neutral to speakers who use it, only that it is less marked than gals and that only masculine terms can ever reach this level of unmarkedness. I can’t help but wonder if it’s speakers who are excluding women when using phrases like you guys or if Montell simply hears it that way due to her own linguistic background.

Another issue I had with this book is that it heavily focuses on English. While the topics discussed throughout the book are fairly universal, only one chapter provides any non-English examples. However, given how Montell handles these non-English examples, especially those from non-Western languages, in that one chapter, that might be for the best. The chapter examines how grammatical gender affects speakers’ perceptions of natural gender, as well as the political consequences, and at points, it’s very effective. I was particularly intrigued by her discussion of French feminists’ attempts to introduce feminine terms for certain jobs in a language where words like doctor are obligatorily masculine (and l’Académie Française is trying very hard to keep them that way). A few pages later, Montell moves onto talk about more complex gender and noun class systems. She gives the now famous example of Dyirbal, where most animate nouns belong to one noun class but “women, fire, and dangerous things” belong to another. She then concludes that this demonstrates that this shows something about Dyirbal speakers’ worldviews—that they see everything as masculine unless it could “literally kill you.” It’s a compelling argument in some ways, but it’s hard to discuss Dyirbal speakers’ worldviews without remembering one thing: Dyirbal is an indigenous Australian language with a single-digit number of native speakers. Yes, it has an interesting—and perhaps problematic—approach to gender, but it’s tied to a very specific (and mostly eradicated) cultural context, and it simply isn’t problematic in the same way as l’Académie Française.

Overall, while I had my issues with Wordslut, I had a good time reading it . It’s not a must read, but if you’re looking for a fun, modern source on gender and language, it’s certainly entertaining and informative. It’s also a book that can definitely be enjoyed by linguists and non-linguists alike; there’s not much jargon that would trip up a non-linguist, but it covers a wide enough variety of topics that linguists (at least those who don’t specialize in sociolinguistics) won’t already know everything it covers. In general, if you’re interested in linguistics and feminism, you’ll probably have a good time and learn something new.

TL;DR

Overall rating: 3.5/5 Good for linguists? Yes, unless you’re already an expert in sociolinguistics Good for non-linguists? A definitive yes, since this assumes no background in linguistics Strong points: Broad scope and a fun, modern overview of the intersection between language and gender Weak points: Very English-centric, and the author’s outrage overshadows the actual information sometimes

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

fly away with me

Fandom: Sanders Sides

Pairing(s): Roceit (Creativity | Roman + Deceit | Janus), platonic but could be read as romantic if you want

Rating: General Audiences

Content Warning(s): blood mention (teeny, non-graphic, in passing), can’t think of any others, but let me know if you think I should tag something!

Length: 1,773 words

Brief Summary: Life isn’t a fairytale. Roman knows this, even as he wishes it were. (But perhaps...perhaps life doesn’t have to be like the stories to be magical.)

TS Masterlist + AO3 Links

*

“Hey.”

A voice pierces through a groggy Roman’s mind, slicing through what had been a rather nice dream about...he thinks it was sword-fighting. And flying. Yes. Sword-fighting and flying about on the deck of a ship, sword-fighting a hook-handed pirate with a mustache and a cackle that looked and sounded suspiciously similar to that of his brother’s.

Yes, whatever it had been, it was a nice dream. Roman would quite like to get back to it now, thanks.

Letting out a quiet, annoyed little “mmrmph,” Roman rolls over and blindly grabs for one of his spare pillows, snuggling tightly into it.

The voice sighs heavily, growing irritated as it speaks next. “Come on, you great big oaf.” Hands slither across his body and attempt to roll him back over. “Wake up already.”

“Nooo,” Roman protests sleepily, clutching his pillow more tightly to his chest and curling his legs up and in on himself.

The hands briefly disappear from Roman’s torso, and he thinks that maybe whoever it is has finally given up. Good, that means he can go back to sleep. Already he can see the pirate ship and his sword and a strangely masculine Wendy reappearing; already he can hear the cries of the gulls and the tinkling of Tinkerbell; already he can smell and taste sea salt and blood and the pirates’ bitter defeat—

—and then the hands reappears, roughly yanking Roman’s pillow out of his grasp.

“Nooo!” Roman whines, more petulant this time, and he reluctantly rolls over to see who or what is so important that they had to interrupt his beauty sleep.

Roman slowly blinks tacky eyes at the blurry, somewhat familiar figure standing beside his bed. “Who...izzat?” he slurs. “Who’re you? Why—”

“Roman, you idiot,” the person sighs, sounding annoyed and affectionate all in one—and he knows that voice, Roman does, only one person he knows can manage to properly pull off that tone—but who? The answer dances on the tip of his tongue, just barely escaping him in his drowsy state.

With the help of the mysteriously magnificent stranger, Roman slowly sits up in bed, his sheets clutched tightly in his fists and strewn about him. He relinquishes his grip on them to reach up and rub at bleary brown eyes.

Once he has successfully rubbed most of the sleep out of his eyes, Roman turns and takes a closer look at the stranger who had so rudely awakened him.

And—oh.

There, at the side of his bed, clothed in a ridiculously formal black and yellow outfit, as per usual, stands Janus, arms folded across his chest, toes tapping impatiently at the wooden floorboards of Roman’s bedroom.

Somehow, knowing who the person is makes both more and less sense in Roman’s head all at once.

“Jan—Janus?” he mumbles, tilting his head curiously at his best friend. “What—what’re you doing here? Why’d you—”

“Yes, because now is definitely the time to play twenty questions,” Janus groans. His arms uncross—Roman has to tear his eyes away from those beautiful, beautiful arms—and he grasps at Roman’s forearm with one hand. “Come on, Roman, we have to go.”

“Wh—” Roman’s bewildered stare meanders its way up Janus’ very pretty chest and up to his very pretty face once more. “Why?”

“No time to explain,” Janus hisses, pulling him out of bed. “Just—come on already, dammit. Get up and get dressed.”

Roman blinks dumbly, and in his half-asleep, half-awake state, he wordlessly lets Janus stand him up and dress him without a fight.

Janus unbuttons Roman’s pajama shirt and exchanges it for a more appropriate long-sleeved shirt and his beloved ITS hoodie. He wriggles off Roman’s pants, switching them out for jeans as Roman’s head lolls against the soft cotton of his hoodie.

Throughout the process Janus sees Roman’s bare chest and sees his bright cartoony Mickey Mouse boxers, and if Roman were more awake, he would most probably shriek and jump halfway across the room, his already-dark cheeks darkening even more with embarrassment. But Roman is still blissfully half-asleep, and Janus’ deft fingers feel so nice as they gently thread a comb through the kinks in Roman’s curls—so nice that he just might fall back to sleep again.

Janus has him sitting back down at the corner of his bed, jamming socks and shoes onto his feet, when Roman finally snaps out of his trance and into full wakefulness.

“Wait—now hold on a minute, pretty little liar!” Roman whisper-shouts, careful not to get too loud even as he chews Janus out. If his parents were to find the two of them now, it would be very awkward indeed. “What exactly is going on here? And—” he elbows Janus out of his bubble of personal space, “��I can tie my own shoes perfectly fine, thank you very much.”

“You sure you can manage it on your own?” Janus scoffs playfully, raising an eyebrow. “Who’s the one that just had to put your jeans on for you as if you were some big overgrown baby?”

Roman’s cheeks heat up. “I changed your diapers when we were younger,” he reminds, “so we’re even.” He’s already bent down to lace his own shoes up before he realizes that Janus has gotten Roman to do exactly what he wanted. He pops his head up to glare at his younger friend, but he relents and ties his shoes nevertheless.

“Touché.” Janus tosses his hands up in mock-defeat. “I surrender.”

Shoes tied—much better than Janus would be able to do, might he add—Roman sits straight up once more, although he refuses to stand up—one last, pathetic attempt at rebelling, even though he knows that Janus’ bright eyes and rare but manic smile will win him over as they always seem to. “Seriously, what exactly is going on here, lord of the lies?”

Janus pinches his fingers together and brings them up to his lips, miming zipping his lips. He shrugs and flicks his finger as if to to ‘throw away the key’.

“Typical.” Roman’s eyes fall on the open window behind Janus, and his mouth drops open in a little ‘o’. “Oh, by the pharaoh's crook and flail—did you—did you climb through the window?” Horror twists through his voice. “Janus, our apartment is on the fourth floor!”

The grin on Janus’ face is something to be worried about—something to be very, very worried about. “Yeah, I totally climbed all the way up to your window. Mm-hmm.”

After a moment of letting Roman stew in his worry, though, Janus snickers and shakes his head. “Nah. Remus is still up. He let me in on the condition that I get him video of you drooling and snoring in your sleep.”

“Wh—I do not drool in my sleep! Or snore!” Roman huffs. “Preposterous.”

Janus’ lips twist into a thin, sly smirk as he holds up his phone. “Oh, but I’ve got evidence suggesting otherwise,” he croons, tantalizingly holding the phone just out of Roman’s grasp.

Roman nearly falls for the ploy. Nearly.

“You’re just trying to get me up to follow you to...wherever you’re trying to take me,” Roman accuses, stabbing a finger towards his friend.

“Think what you will.” Janus shrugs, nonchalantly bringing a hand up to examine his nails. “It was worth a shot.” He slips his phone back into his back pocket.

“Well, I’m not falling for any more of your tricks,” Roman swears.

Janus raises a singular thin eyebrow. “You sure about that?” His left hand reaches into the pocket of his pants, and he fluidly pulls out a set of shiny new car keys, rattling them gently in Roman’s face. “So then...you don’t want to see what my parents got me for my birthday?”

Roman’s eyes grow wide, and, well, maybe he’ll fall for just one more of those tricks—wait, no! He must remain strong!

“No!” he forces himself to insist. “I—I can’t.”

“Well, why not?”

“...I’m not Remus,” Roman admits quietly, looking down at his sneakers. “I’m not as spontaneous as him, I’m not a daredevil like him. And I mean, what if my parents wake up and find out?”

Janus tiptoes over to Roman, placing nimble fingers on Roman’s chin and lifting his head up to look Roman in the eye. “I don’t want you to be Remus,” he says simply. “I want you to be you, and I want you to trust me when I say you’re going to love where we’re going.”

Janus’ eyes twinkle as his fingers pull away from Roman’s gobsmacked face. “And if your parents catch you...well, doesn’t that make things just a bit more fun?” he purrs. “Just a bit more exciting? Just a bit more...dangerous?”

Roman tries to fish around his mind for a coherent response. Tries. Fails. Instead, a noise not unlike a squished dog toy leaks out of his mouth, and he gapes at Janus where he is by the window, silhouetted by moonlight from above and streetlamps from below.

“So.” Janus’ voice is warm as he speaks next. Warm. Inviting. Home.

“Do you trust me?”

Roman stares at Janus, standing there at the window, heterochromatic eyes sparkling with the stars of faraway galaxies. He is bathed in the moonlight, the lighter patch of skin on the side of his face a shimmering silver, and the sight is ethereal, breathtaking.

Roman stares at Janus, with his hand stretched out invitingly towards where Roman himself sits on the side of his bed.

Sure, life may not be the fairy tales that Roman reads more religiously than he does actual religious texts. Perhaps there isn’t a distressed damsel to rescue, or a prince to sweep him off his feet, or a sword to pull from an anvil, or a frog prince to kiss, or a fairy to sprinkle the power of flight over him. So what?

What does it matter if his life isn’t like the fairy tales he reads, when he can simply create and live out his own?

Janus is getting a tad impatient now. Roman can see it in the patchy hand that props itself against his waist, in the exasperated yet fond smile lingering on his face. “Do you trust me?” he repeats, rolling his eyes—no doubt at the sappy look that is spreading across Roman’s own face.

Roman smiles. Reaches for Janus’ hand. Takes it in his own.

“Yes.”

Sepia skin holds firm onto multicolored, and matching grins echo across both faces. Janus darts over to the door, pulling Roman towards him.

They fly.

Fin

*

This was supposed to be under 1k words and it is Not. That is all I shall say on that. Also, title’s from Leaving London by Steffan Argus.

Want to be added onto any of my taglists? Shoot me an ask or a message here or via my other social media!

#sanders sides#thomas sanders sides#roman sanders#ts roman#ts creativity#ts princey#janus sanders#deceit sanders#ts janus#ts deceit#roceit#ts roceit#roman x janus#ts fanfic#ts fanfiction#tss fanfic#tss fanfiction#sanders sides fic#sanders sides fanfic#jwt sanderssides#blood mention#lmk if i need to tag anything else

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gender Census 2019 - The Full Report (Worldwide)

This is a long post! You can see a summary of the big three questions here.

~

Hi and welcome to this year’s worldwide report based on the 11,242 responses to the Gender Census, which ran from 25th February until 30th March. It was mostly shared on Tumblr and Twitter, with some Reddit and Facebook and no doubt some one-to-one link-sharing too.

You can see the spreadsheet of results in full here, which might be helpful if you need to see graphs or figures in more detail. For the charts and graphs of statistics over time, the summary spreadsheet can be found here.

~

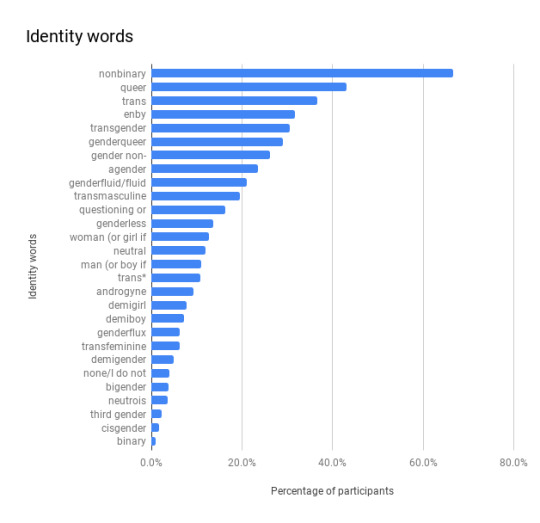

Q1. IDENTITY WORDS

As in previous years, I asked: Which of the following best describe(s) in English how you think of yourself?

Here’s the top 5:

nonbinary - 66.6% (up 6%)

queer - 43.0% (up 40.1%)

trans - 36.6% (up 1.8%)

enby - 31.7% (up 7.2%)

transgender - 30.4% (up 2.5%)

I put queer in bold because it’s new to the list, and the way it’s rocketed to second place is very unusual... and a little suspicious.

The wording of the identity question carefully avoids mentioning gender so that people without genders feel comfortable answering (or not answering), but it’s not really meant to include sexualities. The exception is sexualities that are part of someone’s gender identity, like this comment that someone wrote into the identity checkbox: “femme lesbian (sometimes i feel like lesbian *is* my gender)”

So anyway, last year queer got 2.9% (over the 1% threshold), and I personally know people who feel that their gender is queer, so I added it to the list. Usually when terms are added as checkbox options it might multiply their popularity by about four, but 43% is way too high to be explained by that. Queer is usually used to describe sexuality, so I think perhaps people who identify as queer in terms of their sexuality might have been selecting it too. I’m considering changing it slightly, to something like “queer (as gender identity)” to clarify it for next year. It’s possible that we won’t know if this percentage is due to bad survey design for a year or two.

(Edit: Some feedback on queer and my response to the feedback can be found here.)

Along those lines, several terms were added to the checkbox options this year because they were typed in by over 1% of participants last year:

queer

genderless

demiboy

demigirl

gender non-conforming

There are now 28 terms in the identity checkbox list, and as usual there were people expressing gratitude for the abundance of checkbox options in the identity question. However, there has also been an increase in people entering words into the textboxes that are already in the checkbox list. That means that people are missing or are not able to find the identity words they connect with more than last year, and it doesn’t help that the list is randomised to reduce primacy and recency bias.

Right now I add words to the checkbox list if they reach 1%, and this year for the first time I am considering adding another system for removing words that are not used as much. You can read a blog post I wrote about that here. I concluded based on the results of the 2017 survey (which asked for participants’ ages) that some words that seem to be used less overall are used more often by participants over 30, and since participants over 30 are underrepresented in online surveys generally I will be keeping any word that they enter over 3% of the time even if the word isn’t used as much overall.

Relatedly, I didn’t ask for ages in the survey this year, but I will be collecting information about age in future surveys to make sure that I don’t remove words and accidentally alienate underrepresented age groups. (The age question will be optional and will give age ranges rather than asking for an exact age, so hopefully that won’t make people feel too uncomfortable.)

This year someone complained for the first time that I was excluding words from other languages because I specify “in English” in the question, and if you know me from previous surveys you know that’s the opposite of my intention! Every word entered is counted, and I’m very aware that people use words from other languages while speaking English. So I’m considering rewording the question, but I welcome feedback on this since I’ve never had anyone complain about this issue before and plenty of people already enter non-English words.

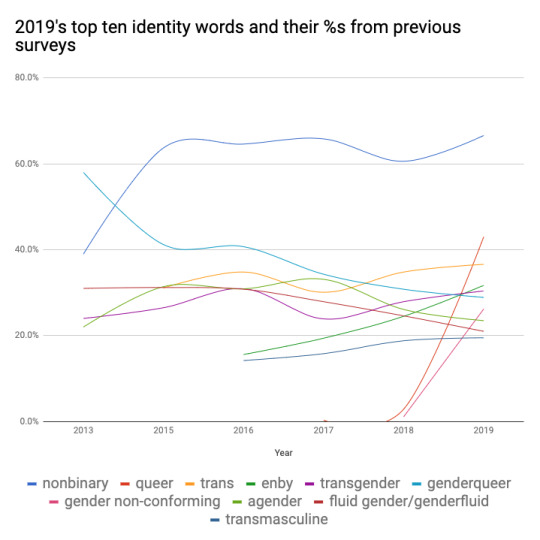

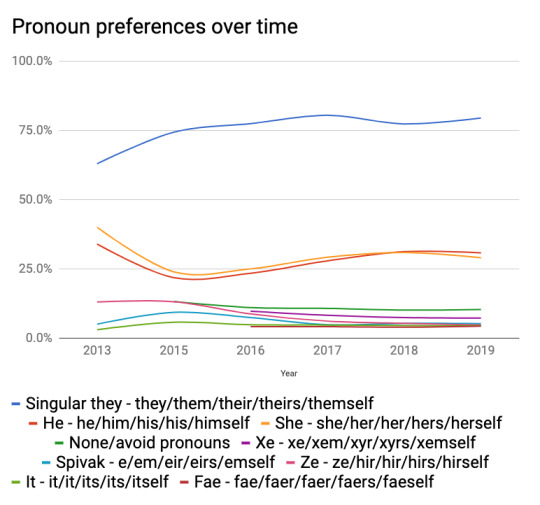

And here’s this year’s top 10 words and their popularity over time:

Those two lines shooting up from 2018 to 2019 are two of the words newly added this year: queer and gender non-conforming. That green line starting near the bottom in 2016 and steadily increasing over time is more like what I’d usually expect - that’s enby, which is now up to #4 on the list.

There are no new identity words to add next year; the closest to 1% was butch with 0.7%. However, since I intend to collect information about age and since people often type, for example, “girl but not woman, even though I am not a minor”, I will be splitting girl, woman, man and boy into separate checkboxes next year.

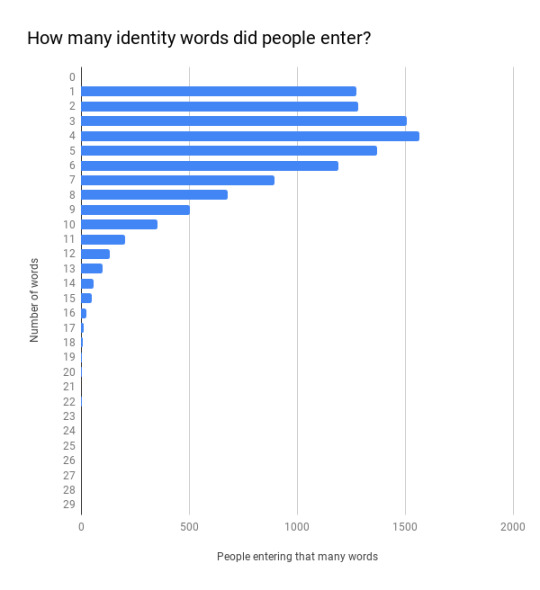

2,021 unique identity words/terms were typed into the “other” textbox, including 413 that were entered more than once. The average number of type-ins for people who actually typed words in was 1.8, and the average words per person overall was 5. Most entered 4 words:

~

Q2: THE TITLE QUESTION

I asked, Supposing all title fields on forms were optional and write-your-own, what would you want yours to be in English? I also clarified that participants should be currently entitled to use it, so they should have a doctorate if they choose Dr, etc.

There were 5 specific titles to choose from, plus a few options like “I choose on the day” and “a non-gendered professional or academic title”. Participants could choose only one, with the goal of finding out what, when pressed, people enter on official records forms and ID.

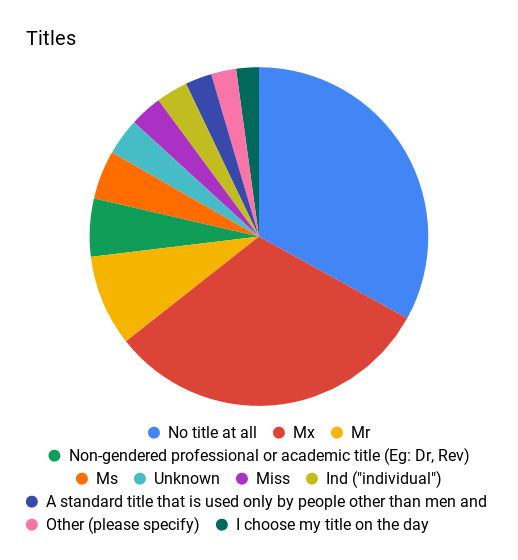

Here’s our top 5:

No title at all - 33.0% (up 0.6%)

Mx - 31.3% (down 1.3%)

Mr - 8.7% (up 0.2%)

Non-gendered prof/acad. - 5.5% (up 0.1%)

Ms - 4.7% (down 1.0%)

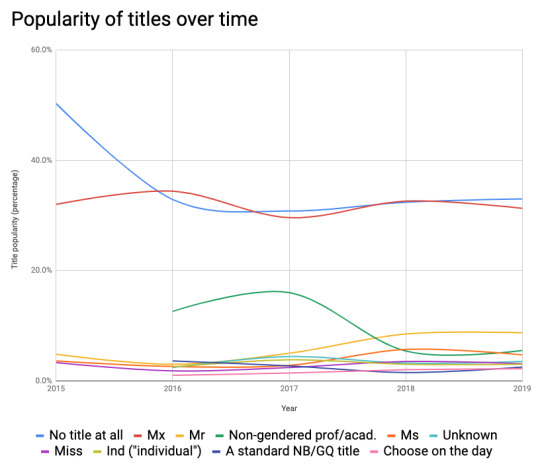

Here’s how that looks compared with previous years:

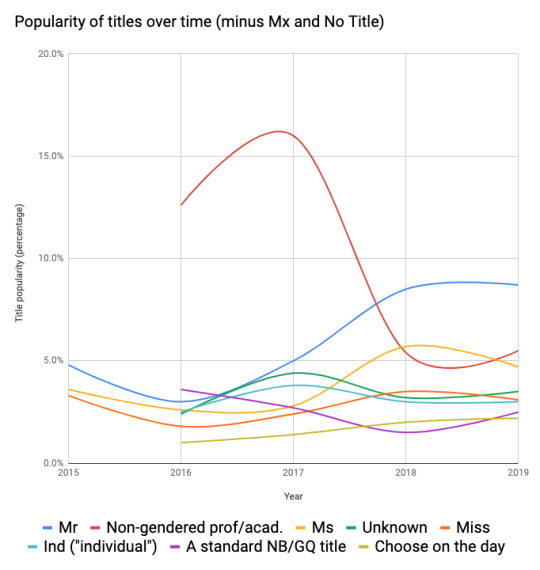

Mx and no title switched places again for the fifth year in a row! And this year I made a similar graph but without Mx and no title. They always get way more than everything else, and it makes it really hard to see what’s going on in the lower half of the graph!

That rollercoaster of a red line is because in 2018 I specified that “non-gendered professional/academic title” should be one that the participant should be entitled to use, which caused that significant drop.

The most popular five “other” textbox titles were:

M - 28 (0.2%)

Comrade - 17

Sir - 10

Mrs - 9

Ser - 7

As with last year, I invited people who chose “a standard title that is used only by people other than men and women” (2.5% of participants) to optionally suggest titles that they’d heard of. The goal is to find a popular title that is considered exclusive to nonbinary genders the way Mr is generally considered exclusive to men and Ms is to women.

243 people checked the “standard exclusive nonbinary” title option, and here’s everything entered more than once:

Mx - 16

M - 4

Xr - 2

Mrs - 2

Mx is generally considered gender-inclusive by people who are familiar with it, especially if their title is Mx, but it’s high on this list because Mx is very well-known generally. M in French is masculine, but in English it’s not gendered and I assume it’s pronounced “em”? (That seems to be what people have said in the notes, but please do tell me if I’m wrong!) It was also the most entered title in the “other” textbox. Xr is new to me, I’m not sure how it’s pronounced.

~

Q3: PRONOUNS

The fourth question was actually a complex set of questions retained from last year, which started with Supposing all pronouns were accepted by everyone without question and were easy to learn, which pronouns are you happy for people to use for you in English? This was accompanied by a list of pre-written checkbox options. It included “a pronoun set not listed here”. and if you chose that it took you to a separate set of questions that let you enter up to five pronoun sets in detail.

As usual, everything that was a pre-written checkbox option got over 1%.

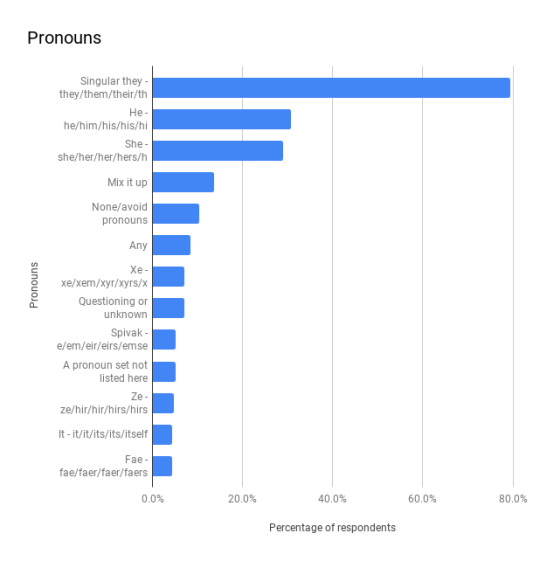

Here’s the top 5:

Singular they - they/them/their/theirs/themself - 79.5% (up 2.1%)

He - he/him/his/his/himself - 30.8% (down 0.4%)

She - she/her/her/hers/herself - 29.0% (down 1.9%)

None/avoid pronouns - 10.3% (up 0.2%)

Xe - xe/xem/xyr/xyrs/xemself - 7.2% (down 0.2%)

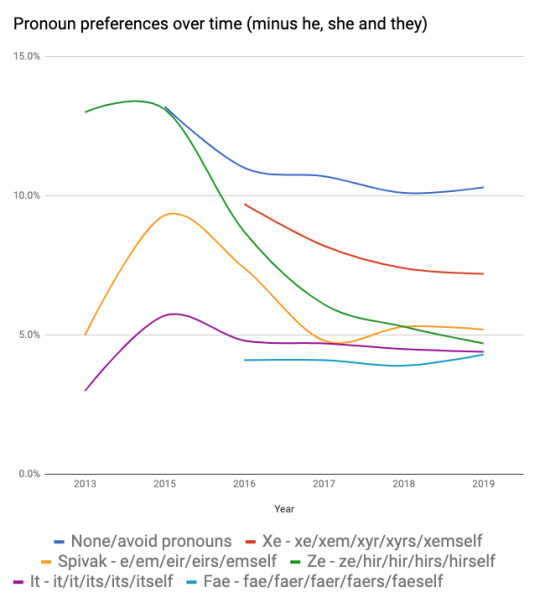

Here’s how that looks over time:

Because singular they, he and she always do better than everything else, let’s look at that chart without them. Every other specific pronoun set got under 8%.

Here’s the top 5 textbox neopronouns, none of which got over 1%:

ne/nem/nemself (singular verbs) - 27 (0.2%)

ve/ver/verself (singular verbs) - 24

ey/em/emself (singular verbs) - 23

ae/aer/aerself (singular verbs) - 22

thon/thon/thonself (singular verbs) - 18

(I’m going by the subject, object and reflexive, because that seems like the best way to collect similar sets together - eyeballing it, the most variations occur in the possessives.)

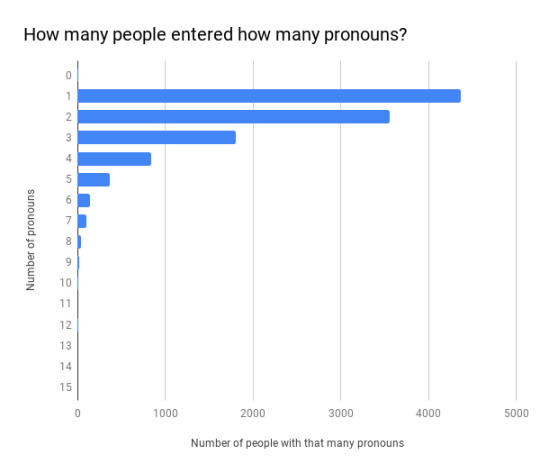

Half of participants don’t like he or she, and 9% like neither he, she nor they. 695 unique sets of neopronouns were entered by 574 people, of which 84 were entered more than once. The average number of pronouns entered was 2.2, and most people (39%) were happy with one set.

Overall it looks like there are no neopronouns really gaining in popularity, and even the checkbox neopronouns are being used less since 2015.

~

THE QUESTIONS I ASK

What should the third gender option on forms be called? - Still no consensus, but nonbinary is at 2 in 3 people and it does seem to be gradually climbing.

Is there a standard neutral title yet? - Not yet. Mx is still consistently far more popular than all other titles, but just as many nonbinary people want no title at all. It’s really important that activists campaigning for greater acceptance of gender diversity remember to fight for titles to be optional, too.

Is there a pronoun that every nonbinary person is happy with? - No. The closest we have to a standard is singular they, and it’s important for journalists and anyone else with a style guide to allow it. It’s levelled out at about 1 in 5 not being into singular they, and 9% of us don’t like he, she or they pronouns.

Are any of the neopronouns gaining ground in a way that competes with singular they? - No. This year the closest is “Xe - xe/xem/xyr/xyrs/xemself” (7.2%, compared to singular they’s 79.5%). Users of these neopronouns will probably not reach consensus for many years - language and especially pronouns can be very slow to settle and gain ground. Even if one neopronoun does become very commonly used, many will continue to use other neopronouns for a long time to come.

~

THIS YEAR IN REVIEW

Crowdfunding was successful enough that I have a little money leftover for costs next year. We had around the same number of participants as last year, but follower numbers and mailing list subscribers increased, which bodes well for next year.

I made some minor changes to the promotional illustrations to make them more gender-/sex-inclusive, and this year I got no complaints, so that was a good move! However, this year I did see a lot more confusion about who is invited to take part. I think the changes were probably worth it to make sure I’m being as welcoming and inclusive as I can be in the promotional stuff, so hopefully people will err on the side of caution and just jump in.

The way that the new survey software collects information, and my increased knowledge of Google Sheets, mean that I didn’t have to resort to MS Excel at all this year. This is really good, because working with unfamiliar software slows me down a lot! My formulae have been more efficient (thanks to my increasing Google Sheets skillz), so the entire sheet could be processed at once instead of being split into several questions. I’m really happy about that, because it means the entire worldwide results report came out less than 24 hours after the survey closed, instead of... *cough* eight months *cough* ...

I made an executive decision not to do a UK report this year, because the added complication makes it really hard for me to motivate myself. It definitely worked, look at that, it’s only March and the worldwide report is already out! I might still do a UK report, and I will keep collecting UK/not UK info about participants so that I always have that option, but for now I’ll just concentrate on the worldwide report and just do the UK report if I feel like it before 2020. And of course the spreadsheet is available to anyone who wants to download it and play with it, so if someone else wants to make some UK-specific statistics happen that is totally possible.

What I’ll do differently next year

In the identity question, I will keep queer as a checkbox option, but I will specify that it’s a gender. Maybe “queer (as gender identity)”? Feedback welcome on this!

In the pronouns question, I’ll change the wording of “none/avoid pronouns” so that it’s clear that it includes just using someone’s name. That’s because a lot of people tried to enter their names as neopronoun sets to express that, and I want to avoid people entering identifying information.

I will ask about age, to make sure that people over 30 are represented by checkbox options. Typically only about 10% of participants are over 30 so I want to make sure as many as possible are comfortable taking part. I’ll group ages into sets of 5 years (21-25, 26-30, etc.) to reduce risk of people being identified, and because entering an exact age probably feels a little more uncomfortable.

After 2020, any identity word, title or pronoun that is entered by less than 3% of participants and less than 3% of participants over 30 can be removed in future surveys. (I am a little concerned about this part, because it’ll make the work more complicated for me, and more work means more risk of epic procrastination. I’ll do my best!)

I’ve finally admitted to myself that I need to separate man and boy, and woman and girl. Currently it’s “woman (or girl if younger)” and “man (or boy if younger)”, and every year plenty of people skip those options in the checkboxes and type in “girl (but not woman even though I’m not a minor)” or something like that, and next year I’ll be asking about age so that’ll be an easy way to determine if there are any adults who are comfortable with one and not the other. This will increase the number of checkboxes to 30, which is pretty unwieldy and will make it harder yet again for people to find their words and increase the rate at which people drop out of the survey, so I’m glad for the under-3% checkbox removal threshold that I’m introducing from 2021 onwards.

Closing thoughts

I slipped up on a couple of things this year (ambiguity over the word “queer”, for example) - but overall I’m pretty impressed with how well I handled it all compared to last year. (I had recently moved house and was trying to rebuild my life, so I didn’t have a lot of spare energy in 2018!)

As always, I’m excited to pore through all your written answers and feedback, and I’m really grateful to everyone who shared the survey link! There were hundreds of RTs and thousands of reblogs, which never ceases to amaze me. Thank you everyone for sharing a small linguistic part of yourselves with me, I hope putting it all together helps you and makes a positive difference to the world!

See also

A list of links to all results, including UK and worldwide, and including previous years

The mailing list for being notified of next year’s survey

~

SUPPORT ME!

I do this basically for free (the crowdfunded money goes entirely on survey software and domain fees), so if you happened to stumble onto my Amazon wishlist and accidentally fall on an Add To Cart button… well, I would be immensely grateful. ;) If you wanted to go and check out Starfriends.org too I reckon Andréa would be pretty chuffed!

#gender census#results#nonbinary#gender census 2019#survey#pronouns#neopronouns#gender-neutral language#language

376 notes

·

View notes

Note

i don't know if you have a post about it but can you explain, dumb down if i'm being honestly, the uses/etc for the different pronouns: indirect object, direct object, etc?

Direct objects are basically what amounts to the accusative case for languages with case systems.

Basically it works like this: Subject verbs an object

The object that is “verbed” is the direct object; it receives the action and is directly acted upon.

So in a sentence like “I kick the ball”, the “I” is the subject, “kick” is the verb, and “the ball” is the object.