#Buddha Head of Eastern Wei

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Cryptic Motif of “Three Hares with Conjoined Ears”

On the Heavenly Palace decorative patterns found in the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang from the late Northern dynasties are images with cryptic patterns, including Buddha's head, the Taotie beast, deer, animals copulating, three hares with conjoined ears, and also writings. This type of decorative pattern is cryptic and difficult to understand and may be closely related to the history of the popular Eastern iconology and divination philosophy from the Han and Wei dynasties and Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou's suppression of Buddhism. They are important references for studying the related history of this period.

#china#motif#three hares with conjoined ears#silk road#culture influenced by buddhism from ancient india#art#reference

884 notes

·

View notes

Photo

© Paolo Dala

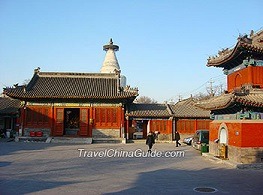

Buddha Head of Eastern Wei From Qingzhou, Shandong, China (530 - 580) Louvre (Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates)

Idols

...Let’s start with a definition. I think to cover all the cases, we should probably define an idol (and I think this is a biblical definition) as anything that we come to rely on for some blessing, or help, or guidance in the place of a wholehearted reliance on the true and living God. That’s my working definition of idol. So you can see that would cover, for example, a rabbit’s foot in your pocket, or a picture of a saint hanging on your wall, or a relic from some sacred shrine sitting on your mantle, or the more forthright images taken from Hindu or Buddhist temples, or the golden calf that Aaron made while Moses was on the mountain.

What makes all of those idols is that we are looking away from a wholehearted reliance upon the true and living God through Jesus Christ, and we are looking at the rabbit’s foot, or the relic, or the picture for some special protection, or blessing, or guidance, or help that we don’t think we could get by just looking to God.

...If we come to crave, love, depend upon, and trust for a blessing people’s praise to enhance our self-exaltation, or money, or power, or sex, or family, or productivity, or anything else besides God himself for the greatest blessing, help, guidance, and satisfaction, then in essence we are doing what idolatry has always done.

...“Little children, keep yourselves from idols. (I John 2:15,16)” Why does John in his letter end that way? He had never even referred to idols in the whole book. He never referred to idols in his whole Gospel. Out of the blue comes this closing sentence with the very word idol that ordinarily means a statue of something that we use to replace God with. “Don’t give in to idols; keep yourselves from idols.”

So why did he end that way? Here’s my closing suggestion. He had said in I John 2:15,16:

“Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world - the desires of the flesh and the desires of the eyes and pride of life - is not from the Father but is from the world.”

Now, John the apostle may have had literal material images in mind when he said, “Keep yourselves from idols.” But I think he is also thinking of the more general deadly problem that anything in the world that successfully competes with our love for God is an idol. So keep yourselves from idols - that is, love God and all that he is for us in Christ more than you love anything.

John Piper What Is An Idol?

#John Piper#What is an Idol?#Ask Pastor John#Desiring God#Theology#Idol#Statue#Sculpture#Art#Buddha Head of Eastern Wei#Chinese#China#Louvre#Abu Dhabi#United Arab Emirates#Buddha#Buddhism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Longmen Grottoes

Longmen Grottoes (World Cultural Heritage, China AAAAA-level tourist attraction)

The Longmen Grottoes are the treasure house of stone carving art with the largest number of statues and the largest scale in the world. It has been rated as "the highest peak of Chinese stone carving art" by UNESCO and ranks first among the major grottoes in China. Unit, AAAAA-level tourist attraction. (14 main attractions)

The grottoes in the Longmen area were first excavated in the Northern Wei Dynasty, flourished in the Tang Dynasty, and finally in the late Qing Dynasty. After more than 10 dynasties, including Northern Wei, Eastern Wei, Western Wei, Northern Qi, Sui, Tang, Five Dynasties, Song, Ming, and Qing Dynasties, it has been built for more than 1,400 years. It is the longest grotto in the world. Among all the caves in Longmen, about 30% of the caves in the Northern Wei Dynasty, 60% in the Tang Dynasty, and only about 10% in other dynasties.

After research, it was found that the Longmen Grottoes were built by Tianzhu (now India), Silla (now South Korea), Tocharo (Siberia), Kanguo (Central Asia) and other countries, and now they have found Western musical instruments, European patterns, ancient Greek stone pillars, etc. The extraterritorial elements are the product of the fusion of diverse civilizations such as Greece, Persia, India and China, and can be called the most internationalized grotto in the world.

Geographical environment

The Longmen Grottoes are located in the southern suburb of Luoyang, the ancient capital. The two mountains face each other, the Yishui River flows, the Foguang Mountains are beautiful, and the scenery is beautiful.

Longmen, also known as Yique, is where the east and west mountains face each other, and the Yihe River flows through it. From afar, it looks like a natural gate, so it was called "Yique" in ancient times.

Longmen Landscape

Longmen Yique

Statue of the Locanabuddha

Locanabuddha

Buddha statues: a total of nine bodies. The main Buddha in the middle is the Great Buddha of Lusena, carved by Wu Zetian according to his own appearance and manners. On the right is the eldest disciple Kasyapa, on the left is the younger disciple Ananda, and then is Samantabhadra Bodhisattva (left) and Manjusri Bodhisattva (right). The heroic and vigorous king, the aggressive warrior and the master Flushena together constitute a group of artistic group images with rich modal texture.

Lord Buddha: Locanabuddha is the Sambhogakaya Buddha, which means the light shines all over the place. The height is 17.14 meters, the head is 4 meters high, and the ears are 1.9 meters long. It is famous for its mysterious smile and is praised as "Oriental Mona Lisa" and "the most beautiful statue in the world" by foreign tourists. The Buddha statue has a plump and round face, wavy hair lines on the top of the head, eyebrows curved like a crescent moon, with a pair of beautiful eyes gazing down slightly, showing a peaceful smile, like a wise and kind middle-aged woman, which is respectable and not afraid.

Samantabhadra Bodhisattva, the free translation of Sanskrit Samantabhadra, has also been translated as Banji Bodhisattva, and transliterated as Sanmando Bhadra. Samantabhadra Bodhisattva is one of the four bodhisattvas of Chinese Buddhism. It symbolizes virtue and conduct, and corresponds to Manjushri, who symbolizes wisdom and virtue. He is also the left and right attendant of Sakyamuni Buddha. In addition, Vairocana Tathagata, Manjushri Bodhisattva, and Samantabhadra Bodhisattva are honored as the "Three Saints of Huayan".

On the left is the "Tang Dynasty After the Journey" drawn by Zhang Xuan in the Tang Dynasty. Wu Zetian carved the Lushena Buddha in the Longmen Grottoes according to his own appearance.

Binyang South Cave

Lotus Cave

Value influence: The lotus dome of the Great Hall of the People is designed based on this lotus.

The smallest Buddha statue in the Longmen Grottoes is only 2 centimeters high. These small thousand Buddhas are located above the south wall of the Lianhua Cave, which are vivid, detailed and lifelike.

Xiangshan Temple

Digital restoration

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Annals of Taiping Zhenjun 6-8 (445-447)

[From WS004. Rebellion of Gai Wu. The Emperor orders the srmana massacred and images of the Buddha destroyed.]

[Taiping Zhenjun 6, 24 January 445 – 11 February 446]

6th Year, Spring, 1st Month, xinhai [13 February], the Chariot Drove to travel to favour Ding province. Summoned and saw the long-lived and elderly, and inquired and asked them.

Decreed the Combined Outer Staff Cavalier Regular Attendant, Song Yin, as envoy to Liu Yilong.

2nd Month [23 February – 23 March], thereupon went west to favour Shangdang, and observed the continuous pattern trees at Xuanshi.

Went west to arrive at Tujing, and chastised and moved the rebellious Hu, and sent [them?] out to matching commanderies and counties.

3rd Month [should be 4th Month?], gengshen [23 April], the Chariot Drove to return to the Palace.

Decreed the various with questionable lawsuits to all be handed over to the Palace Writers, so as to arrange righteous measures and judgements.

This Month [24 March – 22 April, or 23 April - ], the Duke of Jiuquan, Hao Wen, rebelled at Xingcheng, and killed the defence general, Wang Fan. The county magistrate Gai Xian led his lineage clan to chaiste Wen. Wen abandoned the city and fled, and killed himself. His household and staff submitted to execution.

Summer, 4th Month [should be 5th Month?], gengxu [12 June?], the Great General who Conquers the West, the King of Gaoliang, Na, and others chastised the Tuyuhun Muliyan at Bailan in Yinping.

Decreed the Inspector of Qin province, the Duke of Tianshui, Feng Chiwen, to strike Muliyan's older brother's son Shigui at Fuhan.

The Cavalier in Regular Attendance, the Duke of Chengzhou, Wan Dugui, drove by relay-station to issue out [from] Liang province with the western troops and assault Shanshan.

6th Month renchen [24 September], the Chariot Drove on a northern tour.

Shigui heard the army was about to arrive, abandoned the city and escaped in the night.

Autumn, 8th Month, dinghai [17 September], Feng Chiwen entered Fuhan, divided and moved 1 000 families and turned back to Shanggui.

On renchen [22 September], Dugui used light cavalry to arrive at Shanshan, and apprehended their king, Zhenda, so as to go to the Imperial City. The Emperor was greatly pleased, and lavishly wait on him.

The Chariot Drove to favour north of Yin Mountain, and stayed at the Guangde Palace. Decreed to issue out the troops Under Heaven, selecting one part out of three, each to undertake strict precaution, so as to wait for later instructions. Moved the various kindred and mixed people, more than 5 000 families to the northern border. Ordered the people to move north livestock shepherds to the Wide Desert, so as to bait the Ruanruan.

On renyin [2 October], the King of Gaoliang, Na's army came to Mantou City. Muliyan spurred his section groups west across the Drifting Sands. Na urgently pursued.

The former King of Xiqin, Mugi's Heir Beinang confronted the army to resist in battle. Na struck and routed him. Beinang escaped and ran with his light cavalry. The Duke of Zhongshan, Du Feng, pursued him with elite cavalry, crossed the Three Cliffs, and arrived at Xue Mountain. He captured alive Beinang, Shigui, and Chipan's son Chenglong, and sent them off to the Imperial City. Muliyan thereupon went west to enter the state of Yutian.

9th Month [17 October – 14 November], Gai Wu of the Lushui Hu assembled a multitude to rebel at Xingcheng.

Winter, 10th Month, wuzi [17 November], the Chang'an Garrison Deputy Commander, Yuan He, led the multitudes to chastise him, and was killed by Wu.

Wu's partisans thereupon multiplied. The people all crossed the Wei and ran into the Southern Mountains. Hence decreed to issue out the Chile cavalry of Gaoping to hasten to Chang'an. Decreed General Shusun Ba to drive by relay-station to command and organize the troops of Bing, Qin and Yong stationed to the north of the Wei.

11th Month [15 December – 12 January], the King of Gaoliang, Na rearranged the battalions to turn back to the Imperial City.

On jiwei [18 December], dispatched Na and the Master of Writing Within the Hall, the Duke of Anding, Han Mao, to lead cavalry stationed in Xiang province's Yangping commandery. Sent out the people of Ji province to build a floating bridge at Que'ao Ford.

Gai Wu dispatched his section group leader Bai Guangping to plunder Xinping. The chieftains of the various Yi of Anding all assembled multitudes in response to him, and killed the defence commander of Qiancheng.

Wu thereupon advanced the army to Lirun Fort, and divided off troops to rob Linjin and Badong. General Zhang Zhi fought with them, and greatly defeated them. The troops that drowned and died in the He was more than 30 000 people. Wu also dispatched troops west to plunder until Chang'an. General Shisun Ba fought with them at Weinan [or “North of the Wei”], and greatly routed them. The cut off heads numbered more than 30 000 people.

On gengshen [19 December], the King of Liaodong, Dou Loutou, passed away.

Xue Yongzong of the Hedong Shu assembled a faction steal several thousand public horses, and chased more than 3 000 people to enter the Bend of the Fen. To the west he communicated with Gai Wu, and accepted his ranks and titles. The Inspector of Qin province, the Duke of Jincheng, Zhou Luguan, led the multitudes to chastise him, did not overcome, and turned back.

On gengwu [29 December], decreed the Master of Writing Within the Hall, the Duke of Fufeng, Yuan Chuzhen, and the Master of Writing, the Duke of Pingyang, Murong Song, with 20 000 cavalry, to chastise Xue Yongzong. Decreed the Master of Writng Within the Hall, Yi Ba, to lead 5 generals and 30 000 cavalry to chastise Gai Wu. The Duke of Xiping, Kou Ti, with 3 generals and 10 000 cavalry to chastise Wu's partisan Bai Guangping.

Gai Wu titled himself King of the Heavenly Terrace, and appointed and set up the Hundred Officials.

On xinwei [30 December], the Chariot Drove to return to the Palace. Selected the brave and fierce among the troops of the six provinces, 20 000 people, and sent the King of Yongchang, Ren, and the King of Gaoliang, Na, to divide command, and go along two roads, each with 10 000 cavalry, to go south and carry off from the Huai and Si and northwards [?], and the population of Qing and Xu so as to fill North of the He.

On guiwei [11 January], the Chariot Drove on a western tour.

[Taiping Zhenjun 7, 12 February 446 – 31 January 447]

7th Year, Spring, 1st Month, wuchen [25 February], the Chariot Drove to stay in Dongyong provnice.

On xinwei [28 February], the Chariot Drove south to favour Fenyin.

On gengchen [9 March], the Emperor overlooked Xi River. Gai Wu withdrew and ran to Beidi.

2nd Month, bingxu [15 March], favoured Chang'an. Inquired and asked the fathers and elders.

On dinghai [16 March], favoured Kunming Pool.

On bingshen [25 March], favoured Zhouzhi. Executed the rebellious people at Gengqing and Sunwen Ramparts who had communicated plans with Gai Wu.

The army stayed at Chencang. Executed the Di of San Pass who had murdered the defence general.

Turned back to favour Yongcheng. Hunted on the sunny side of Qi Mountain.

The various armies on the northern road, Yi Ba and others, greatly routed Gai Wu at Xingcheng. Wu abandoned his horse and escaped on foot.

The King of Yongchang, Ren, arrived at Gaoping. He apprehended Liu Yilong's general Wang Zhang, plundered Jinxiang and Fangyu, and moved their people, 5 000 families, to the north of the He. The King of Gaoliang, Na, arrived at Dongpingling in Ji'nan, and moved its people, more than 6 000 families, to the north of the He.

3rd Month [12 April – 11 May], decreed the various provinces to massacre the srmanas, and destroy the various Buddhist figures. Moved the artisans and craftsmen of Chang'an city, 2 000 families, to the Imperial city. The Chariot Drove to turn around the carriage, and favoured Luo River. Detached an army to execute the rebellious Qiang of Lirun.

This Month, Bian Jiong of Jincheng and Liang Hui of Tianshui rebelled, and occupied the eastern city of Shanggui. The Inspector of Qin province, Feng Chiwen, struck them, and beheaded Jiong. The multitudes then pushed forward Hui as the leader.

Summer, 4th Month, jiashen [12 May], the Chariot Drove to arrive from Chang'an.

On wuzi [16 May], at Ye City they destroyed the five storey Buddha image. Within the clay of the figure they obtained two jade signets, their writings both said: “Accept instructions from Heaven, soon long life and perpetual glory.” One of them had an engraving on its side saying: “Han's transmitted signet of state accepted by Wei”.

5th Month, guihai [20 June], the Duke of Anfeng, Lü Gen, led cavalry went to Shanggui, he and Chiwen chastised Liang Hui. Hui ran to Hanzhong.

Gai Wu again assembled at Xingcheng, declaring himself King of Qindi [“Qin Land”]. He made use of appointing the mountain people, the multitudes turned around and were again agitated. Hence dispatched the King of Yongchang, Ren, and the King of Gaoliang, Na to supervise the various armies of the northern road, and together chastise them.

6th Month, jiashen [11 July], issued out troops from Ding, Ji, and Xiang provinces, 20 000 people, to station various valleys in the mountains south of Chang'an, so as to forestall escapes beyond.

On bingxu [13 July], issued out from Si, You, Ding, Ji provinces, 100 000 people to build above the imperial domain a frontier circuit, rising up [from?] Shanggu and going west until the He, both in length and breadth a thousand li.

Autumn, 8th Month [7 September – 5 October], Gai Wu was killed by his subordinate people, they transmitted the head to the Imperial City. The King of Yongchang, Ren, pacified his left-over cinders. The King of Gaoliang, Na, routed Gai Wu's partisan Bai Guangping. Captured alive Tuge Lunaluo in Anding, and beheaded him in the Imperial City. Restored the Duke of Lüeyang, Jie'er to the feudal rank of King.

[Taiping Zhenjun 8, 1 February 447 – 21 February 448]

8th Year, Spring, 1st Month [1 February – 2 March], the Tujing Hu obstructed the strategic passes to make banditry. Decreed the General who Conquers the East, the King of Wuchang, Ti, and the General who Conquers the South, the King of Huainan, Ta, to chastise them. They did not submit. The mountain Hu, Cao Puhun and others, crossed west of the He. They guarded the mountains to strengthen themselves, and summoned and pulled in the various Hu of Shuofang. Ti and others guided the army to chastise Puhun.

2nd Month, jimao [4 March], the King of Gaoliang, Na, and others went from Anding to chastise and pacify the Hu of Shuofang. Following that, they combined armies with Ti and othesr, and together attacked Puhun, and beheaded him. Those of his multitudes who hurried to the strategic passes and died numbered in the ten thousands.

On guiwei [7 March], travelled to favour Zhongshan. Conferred and bestowed on the accompanying civil and military officials each proportionally.

The people of Yi county in Gaoyang did not follow the official instructions. Chastised and pacified them, and moved their remnant cinders to Beidi.

3rd Month [1 April – 30 April], the King of Hexi, Juqu Mujian, planned rebellion, and submitted execution.

Moved 3 000 families of the Dingling of Ding province to the Imperial City.

Summer, 5th Month [31 May – 28 June], the Chariot Drove to return to the Palace.

6th Month [29 June – 28 July], the various generals of the Western Campaign, the Duke of Fufeng, Yuan Chuzhen, and others, 8 generals were convicted of stealing and seizing army property that had been captured and plundered. The booty each numbered in the 10 000 000. Beheaded all of them.

8th Month [27 August – 25 September], the Great General of Guards, the King of Le'an, Fan, passed away.

Winter, 10th Month [25 October – 23 November], the Palace Attendant and Overseer of the Palace Writers, the King of Yidu, Mu Shou, passed away.

12th Month [23 December – 21 January], the states of Shanshan and Zheyi both dispatched sons to court to present.

The King Jin, Fuluo, passed away.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What do the Bamiyan Buddhas of Afghanistan, Botticelli’s La Primavera, and a 639-year performance of John Cage’s As Slow aS Possible have in common? It almost seems like the set up of a bad art joke. Except, there’s no punchline here. These pieces may be separated by extinct eras and irreconcilable distinctions in culture and location, but they are inextricably connected through one concept: the death of art. Instead of the usual discussion of a single artist or work, these three pieces will lead an inquiry into the abstract and nebulous idea of what it means for art to die. To be clear, I will be focusing on the most literal aspect of this hypothetical, that being the deformation or nonexistence of a work. Though we traditionally consider art to be everlasting, a message to generations of strangers far past the confines of our own timelines—when movements die, when sculptures decay, when paintings mold—our perceptions and remembrance of those works are irrevocably changed.

In the most literal sense of the term, the death of art is almost always first realized with physical degradation. If you peer closely and imagine openly, you can almost see it. There exists a faint sense of the former glory once held by the Bamiyan Buddhas. Erected in the 6th century, the immense figures were a sight to behold on the middle leg of the Silk Road. In the prime of the Buddhas’ exhibition, their distinctive style spoke volumes to this blended heritage. The high relief sculptures were carved directly from alcoves in the sandstone cliffs of Bamyan with additional details being molded with binding coats of mud and stucco. Atop this base, the Buddhas were lavished with painted on details and jewels to accentuate their air of divinity. They are children of the Orient and the Occident. Both Buddhas inherited Hellenistic drapery from the Greeks, stoic expressions from their Wei Dynasty predecessors, androgynous proportions from Gupta India. The hybrid aesthetic of Gandhara sculpture distinguishes itself from every other archaic school of art as there is an obvious integration of its western and eastern heritage.

We may look at accounts from ancient travelers and merchants to learn of what the Buddhas once were, but the modern perspective on their current status is equally important. The questions we must ask concern how and why the conversation surrounding these Gautama figures has shifted post-destruction. In 2001, the Taliban government, with jurisdiction over the Bamyan valley, detonated dynamite and fired anti-aircraft artillery at the Buddhas for weeks. The bare bones of their original foundation were all that was left. Taliban head Mullah Mohammed Omar ordered the attack on the pretense of destroying iconoclastic figures. While he may have achieved his goal at its face value, in some considerations, Omar only further drove the impression of the Bamiyan Buddhas in the narrative of world history.

Since the 2001 defacing of the statues, UNESCO claimed the region as a World Heritage Site, international outrage fueled efforts against the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, and both the art history and scientific communities united as a front to salvage what could be saved of the Buddhas. The tragedy of the Bamyan Buddhas is not unique. Unfortunately, these incidents befall on art in a manner that is as nondiscriminatory as it is consistent. Be it Gustave Courbet’s Stonebreakers or towering Gandhara Buddhas, we have to accept the unsuspecting vulnerability and obliqueness of our creations. If the Buddhas were to serve some sort of parable, we should take away that even if colors are dulled, canvas warps, or sculptures are left as piles of ashen smithereens, the artistry that once existed does not have to die too. Perhaps it will always be missing something, some essence that was one and the same as its vessel, but the Bamyan Buddhas represent every reason why we cannot afford to forget in the face of these crimes against culture.

So if art can live on even with the absence or deformation of its literal presence, what does it take for art to die?

If you have an artist or a specific piece you’d like my take on, comment on this post. See you Saturday!

#art#art history#helloblarty#bamyan#buddha#buddhist art#bamiyan buddhas#afghanistan#gandhara#sculpture#6th century#6th century art#gandhara art

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Architecture (Part 24): Chinese Pagodas

The Chinese pagoda is a combination of two sources – 1) the multi-storied wooden tower, which developed before Buddhism arrived in the 00's BC, and forms the main body of the pagoda; and 2) the Buddhist stupa from India, which forms its spire or finial. Pagodas were usually made of wood or brick, or a combination of the two.

The base plan varied between different dynastic periods. Overall, though, the square plan was the main choice before the 900's AD, and then polygonal plans became dominant.

Pagoda style changed and evolved – because of the influence of new stupa forms in the West, stylistic evolution, and changes in faith. Pagodas were not only built on Buddhist sites: they could be on their own, and were occasionally used in feng shui interpretations.

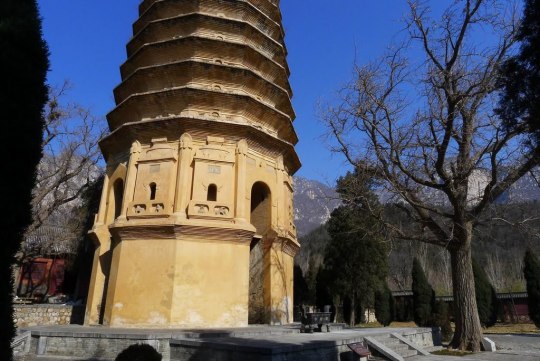

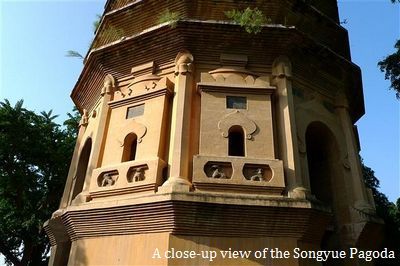

The Songyue Pagoda was built in 523 AD, during the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-535). It is located in the Henan province, at the Songyue Monastery on Mount Song. It is the oldest-existing brick pagoda in China, and at the time of its construction, most pagodas were made of wood.

It is the only Chinese pagoda to have a 12-sided (dodecagonal) base plan. It is 40m high, and made of yellow brick & clay mortar. The height of the pagoda decreases towards the top.

The ground floor is very high (this is common in pagodas with multiple eaves). Balconies divide it into two sections. On the outside, the doors and niches are carved with teapots and lions. The pillars have lotus-flower carvings on the bases, and lotus-flower & pearl carvings on the capitals.

Above the ground floor, there are 15 stories, all closely-spaced and with their own individual roofs. These roofs are lined with eaves and small lattice windows. Each storey is ornamented with ornamented bracket-cluster eaves in the dougong style. The pagoda is topped with a mast and discs.

Inside, the pagoda is octagonal rather than dodecagonal. There are 8 levels of projecting stone supports, probably to support the original wooden floors. A series of burial chambers were built beneath the pagoda; the innermost chamber had Buddhist relics, statues and scriptures.

Sarira Pagoda (937-75) is located at the Qixia Temple in Nanjing. It is small, and made of white stone. The base plan is octagonal, and it has five stories.

Sarira Pagoda.

Reliefs are carved on the exterior walls. On the base, there are various reliefs of the Buddha; also dragons, phoenixes, birds and flowers. On the body of the pagoda, there are carvings of the Heavenly Kings (four Buddhist gods who watch over the four cardinal points of the world), the Wenshu Buddha (Manjusri, the Buddha of Wisdom), and Puxian Buddha (Bodhisattva of Universal Benevolence) riding an elephant.

Base of the pagoda.

Carvings on the main body.

On each storey, there is a shrine with a Buddha. The base and finial are richly decorated with lotus motifs; the lotus is part of the imagery of the “Pure Land” school of Buddhism.

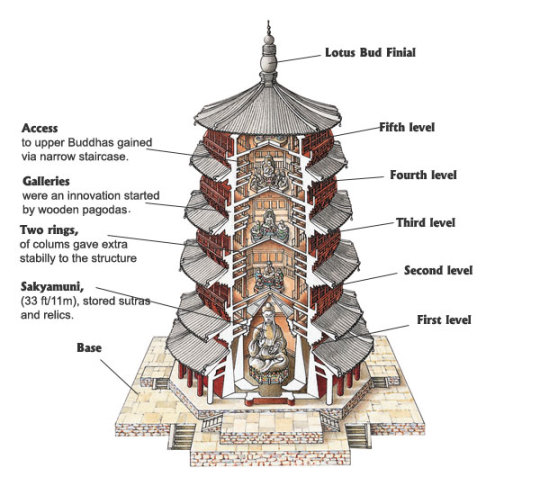

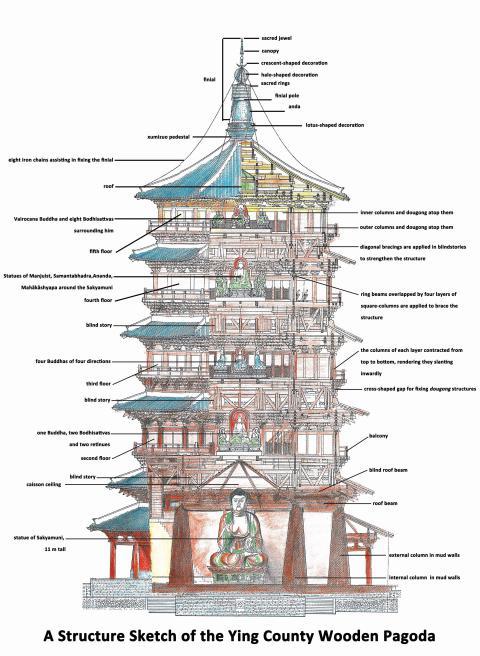

The Sakyamuni Pagoda was built in 1056, during the Liao Dynasty (907-1125), which ruled present-day Mongolia, part of the Russian Far East, northern Korea, and northern China. It was built by Emperor Daozong, who took the throne in 1055, and built on the site of his grandmother's family home. It is located on the central point of the Fogong Temple's main north-south axis (a common choice of location before the 700's).

The temple was built 85km south of Datong (the Liao Dynasty capital) in Shanxi province. It was originally called Baogong Temple, and was renamed Fogong Temple in 1315, during the Yuan Dynasty. During the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), its grounds were said to be massive, but it declined during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Liao Dynasty (1025).

The pagoda is the tallest wooden building in the whole of China, and is the oldest-existing pagoda to be built entirely of wood. It is 67.3m tall – it stands on a 4m-tall base, and the steeple is 10m tall.

It has 54 different types of bracket sets (the most for any Liao Dynasty building), but this isn't noticeable from a distance, as its structure has a high level of harmony and unity. There is a mezzanine level between each outer storey.

Dougong of the pagoda.

From the outside, the pagoda seems to have only 5 stories, and the ground floor seems to have two sets of rooftop eaves. Actually, there are 9 stories inside, as indicated by the pagoda's exterior pingzuo (terrace balconies). [I'm not sure if these are the same as the mezzanine levels.] The lower set of rooftop eaves on the ground floor covers the skirting verandah.

The lowest set of eaves is supported by a ring of columns; there are also support columns inside. The pagoda is named because of the 11m-high statue of the Buddha Sakayumi on the ground floor. There is an ornate zǎojǐng (cassion) above its head, and also one zǎojǐng carved into the ceiling of each storey. The pagoda has a hexagonal base plan, but is 8-sided.

Ground floor.

A zǎojǐng (meaning literally “algae well”) is also called a cassion, cassion ceiling, and spider web ceiling. It is a feature of East Asian architecture, found usually in the ceilings of temples & palaces, and usually in the centre, right above the main throne, seat or religious figure (here, it is the statue of the Buddha). Usually, it is a sunken panel set into the ceiling, often layered & richly decorated. Circles, squares, hexagons, octagons, and combinations of those shapes are common.

Cassion in the Forbidden City.

The Beisi Pagoda (also called the North Temple Pagoda) is located in the Bao'en Temple in Suzhou. The original pagoda was built in 1153, during the Song Dynasty (960-1279); the Buddhist monk Dayuan was in charge of its patronage and construction. The pagoda burned down near the end of the Song Dynasty, and was rebuilt during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). This is the pagoda that we have today.

It has an octagonal base, and is 76m tall. There used to be eleven stories, but it was damaged at some point and now there are only nine. It has double eaves and flying corners. The base and outside walls are made of brick, and the balustrades are made of stone. However, because it is wrapped with wooden cladding (the eaves and banisters are wooden), it looks like a timber structure from the outside.

Kaiyuan Temple is located in Quanshou, in Fujian province (south-eastern China). Originally called Lotus Temple, it was built in 685-86, during the Tang Dynasty, and gained its present name in 738. It is a Hindu-Buddhist temple, and one of the few surviving Hindu temples in mainland China.

Two twin pagodas stand to either side of the temple, about 200m apart from each other; they are the highest twin pagodas in China. Renshou Pagoda is on the west side, and Zhenguo Pagoda on the east. They are octagonal plans, and their eave corners turn upwards dramatically, in typical southern style. Their elaborate bracket sets imitate woodwork.

Renshou Pagoda.

Zhenguo Pagoda.

Mahavira Hall (the temple’s main hall).

The first Renshou Pagoda was built in 916, during the Five Dynasties period (907-60), and made of wood. It burned down twice in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), and was rebuilt each time – first with brick, and then with stone. Both pagodas have the same appearance and structure. Renshou Pagoda is 44.6m high, the shorter of the two.

Zhengou Pagoda was built during the Xiantong Period (860-73) of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). It was destroyed in 1155 and rebuilt in 1186; then demolished again in 1227 and rebuilt in stone in 1238. It is 48.24m high, 18.5m in diameter, and each side is 7.8m wide.

It stands on a Sumeru pedestal (a type of substructure named after the mythical Mount Sumeru). This Sumeru pedestal is quite low, and carved with a tier of lotus flowers and a tier of grasses. A celestial guard shouldering the pedestal is carved on each of its eight corners; and its girdle is carved with 39 pictures, including tales about the Buddha, and images of dragons, lions and other animals. The pedestal is surrounded by stone railings, and has five steps cut into each of its four sides.

Four of the pagoda's walls have doors, and the other four have niches for Buddhist statues. On both sides of the doors, images of heavenly kings and celestial guards are carved. On both sides of the niches, images of Manjusri, Samantabhadra & other bodhisattvas are carved, as well as gods and Buddhist disciples. Some carry the sun and moon in their palms; others hold calabashes or sceptres.

Each storey has a verandah on the outside. The corners of each storey are cylindrical, which is rare in ancient architecture.

Inside, there is a central pillar, winding corridors, and staircases. Unlike most winding or vertical staircases in pagodas, these aren't built along the inside of the walls, or along the central pillar. Instead, they are installed through a square hole on one side of the pillar (the pillar is solid and has no compartments). The floors are made up of two layers, with a facing of stone strips, and are supported by stone beams.

The iron steeples are stylistically typical of multi-storeyed pagodas. Iron chains connect them to the corners of their roofs.

The White Dagoba is located at Miaoying Temple, which is also called the White Stupa Temple or White Dagoba Temple. The temple was built in the city of Dadu, and is now in Beijing's Xicheng District. Dagoba is Sinhalese for the Buddhist stupa, and the word shows the building's Tibetan origins.

In 1271, Kublai Khan united the country of China under the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and Tibet also began to come under the Yuan Dynasty's power. To consolidate the relationship between the empire and Tibet (which was mostly under the rule of religious authorities), Kublai Khan ordered the White Dagoba to be built. The architect was Anigo, from Nepal.

The construction lasted from 1271-79. Then, Kublai Khan ordered a temple to be built around it. The area of the temple was 160,000m2, and this was decided by the Emperor firing four arrows in four directions from the top of the White Dagoba. The temple was called Dashengshou Wan'an Temple.

During the Yuan Dynasty, the temple was mostly used as an imperial temple. The governor ordered that all important ceremonies were to be rehearsed here three days ahead of time. When Kublai Khan died, his sacrificial ceremony was held here.

People called Dadu (the capital at the time) and the White Dagoba “Golden City and Jade Dagoba”. The temple was burned down in 1368, but the dagoba survived. In 1457, during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), Emperor Tianshun ordered the temple to be rebuilt. However, it was much smaller this time – about 13,000m2 – and it was renamed Miaoying Temple.

The current temple.

In the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the Miaoying Temple was one of the most well-known locations for temple fairs, hence the saying, “August 8th, time to visit the white dagoba”. On October 25th (according to the lunar calendar), there was a custom of lamas walking around the dagoba, chanting scriptures and playing music. This is the anniversary of the dagoba's completion.

The Miaoying Temple consists mostly of the White Dagoba and four halls (which store Buddhist statues, classical Buddhist scriptures, five Buddhist crowns, flowery cassocks, fabrics, and other artifacts). The golden Dagoba Longevity Statue is the most famous – it is 5.4cm tall, and has over 40 rubies. The bronzy [?] Kwan-yin Boddhisattva Statue (with 1000 hands & eyes) is also very famous. These current halls are from the Qing Dynasty.

The White Dagoba is north of the Miaoying Temple. It has a 3-layered base, and the body looks like an upside-down ice-cream cone. On top of the body is a thick wooden base, upon which is a solid bronze canopy. This is supported by strong iron chains. On the very top is another small stupa.

It is made of white-washed brick, and is 48m tall. The borders of the dagoba [or the stupa on top?] are adorned with small Buddhist characters and statues, and wind chimes. This dagoba is the earliest and largest Tibetan dagoba in China.

The White Dagoba.

#book: a concise history of architectural styles#history#architecture#china#ancient china#tibet#chinese architecture#chinese pagodas#northern wei dynasty#liao dynasty#yuan dynasty#song dynasty#ming dynasty#tang dynasty#qing dynasty#quanshou#songyue pagoda#songyue monastery#sarira pagoda#qixia temple#sakyamuni pagoda#fogong temple#beisi pagoda#bao'en temple#kaiyuan temple#renshou pagoda#zhenguo pagoda#white dagoba#miaoying temple

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Organization of the Chinese Pantheon {Part 2}

Today we learn who Daji is and where Wukong currently is.

Hidden Operations

An open secret to the gods, Daji functions as Nuwa's right-hand executing her orders the way she may see fit. With her sisters, the Pheasant Spirit and the Lute Spirit, Daji is responsible for the fall of many dynasties, reveling in the destruction and havoc she has brought. The gods pay Daji no mind as it is the business of a Primordial but they fear the day Daji will turn against them and bring about the fall of the Celestial Bureaucracy.

The Ministry of Water: The Ministry of Water deals with all bodies of water from the great expanse of the oceans to something as tiny as a puddle. Due to its large operations, the Ministry is divided into hundreds of sub-divisions, each dealing with a local water body. The Ministry of Water has been headed by various gods in the past. Currently, it's Ao Kuang, much to the disappointment of the other water gods.

Head Minister, Ao Kuang: Ao Kuang believes that he's on the wrong side of history. His palace has been ruined by countless heroes following Wukong's example. Thanks to Ne Zha's worshipers who depict him as an evil serpent who wants to eat humans (he does), the smear campaign against him is getting the Dragon King frustrated to an unbearable point. Then there's Jing Wei, who has made it her mission to dump rocks into the Eastern Sea. The Dragon King has filed countless reports to the Ministry of Bird Extermination and it is still not being dealt with.

Deputy Commissioner of Rivers, He Bo: The Yellow River was the very first head of the Ministry of Water when the Bureaucracy was founded. Its life-giving water is said to come from the Kunlun Mountain paradise in the west, the home of the mystics. He Bo used to demand virgin sacrifices from the mortal population along the river and devastate villages if the offerings aren't met. Defeated at the hands of Hou Yi, He Bo would face humiliation again when Erlang Shen challenged him, ending the tradition of virgin girl sacrfice. Now the Yellow River is an active and diligent member of the Ministry and is the only one who finishes all the important paperwork in time.

The Ministry of Exorcisms: The Underworld is home to many Ministries, none as important to the mortal population as the Ministry of Exorcisms. Occasionally, some playful demons and spirits slip between the well-guarded gates of the afterlife to wreak havoc on mankind. It's up to the Ministry of Exorcisms to file paperwork and report to Fengdu Dadi, the Jade Emperor and the Chief Minister of the East Mountain before setting out to capture these spirits.

Zhong Kui: Zhong Kui used to with two Ministries at once. Due to his brilliance, he was selected by Fengdu Dadi to become an Exorcist God. After years of exorcising demons from the mortal plane, he was promoted as a member of the Board of Imperial Examiners in the Ministry of Examinations. With the battles being waged with the other pantheons, the walls of the Dark Capital have fallen to otherworldly fiends. The Yanluo Wang have given him the permission to remain in the mortal plane at all times as to mitigate the damage done to the civilian populace. Due to his empty desk and a continuously piling paperwork, Zhong Kui has been demoted back to being the Official of the Ministry of Exorcisms and has since been fired from Board of Imperial Examiners.

Non-Bureaucratic Mentions

YAN DI'S GRAVE: Yan Di, the Flame Emperor was slain during a rebellion against Huang Di, the Yellow Emperor. After his death, Xing Tian, his devoted lieutenant attacked Huang Di. In the battle, the Emperor decapitated Xing Tian. Never the one to back down, Xing Tian continued to brandish his shield and battle-ax. His indomitable spirit guards Yan Di's grave, violently attacking anyone who dares desecrate it. The unwavering warrior avoids the battlefield of the gods, preferring the relaxation of poetry and music. The Heavenly Legion believes that he's an important tool to utilize in the war and has been planning a while to rouse his wrath on their enemies.

SUKHAVATI: Sukhavati is the celestial abode of Amitabha Buddha located at the western edge of the cosmos. After attaining Buddhahood through their journey, Sun Wukong and his friend, Zhu Bajie retire here in a state of eternal bliss. Occasionally the Monkey King prefers to check on his primate subjects in Mountain of Flowers and Fruits. Sun Wukong is the Bureaucracy's wild card. They never know what he's going to do for them. He will show up in the Jade Emperor’s court relaying some important details or be on the side of the enemy legions. After gaining enlightenment, Wukong now acts as an instrument beyond the Celestial Bureaucracy. He prefers to work with the Bodhisattvas and other protector deities to guide the laymen to achieve the state of nirvana.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Koan Q & A

Q: What is the basic purpose of koans?

A: Mainly to put a stop to representational thinking.

Q: Just what exactly do you mean by representational thinking?

A: Basically, representational thinking deals with the habitual use of mental images at a very subtle level. The major problem with such thinking is that we believe it matches the object it tries to represent. But it doesn't. From a Buddhist standpoint, no representation can match our Buddha-nature. And as long as we try to visualize this nature, we are just going to run around in circles.

Q: If I am given a koan, then, I am expected to perceive what is not a mental image--breaking my habit of representational thinking--right?

A: Yes...that's right. But surmounting such thinking, especially for us moderns, is really difficult. Often, we fail to arrive at the limit of representational thinking. Some even go so far as to represent non-representational thinking! Talk about delusion!

Q: Could you explain how all this pertains to the "Mu" koan about whether or not a dog has the Buddha-nature?

A: As you know Joshu replied to the question with "Mu", meaning "No". This came as a shock to the questioner who believed that all sentient beings, including a dog, have the potential to realize Buddhahood in the future. In regard to the koan exercise, itself, as laid out by Chinese Zen master Ta-hui, Joshu's "Mu" is called a *hua-wei* meaning "word-tail". For the practitioner thinking "Mu" in his mind's eye, it is merely a hua-wei, being no more than a mental image, or more precisely, a mental sound. In the exercise, itself, hua-wei chiefly refers to representational thinking. "Mu", let us say, is the grand representation of all! Imagine, then, trying to transcend "Mu", seeing the *pure antecedentness* of the hua-wei called the *hau-t'ou*, meaning 'ante-word'. But that is what we have to do. Basically, this means to look at the suchness which comes prior to the arising of Mu in our mind's eye. If we look correctly, we will see the first trace of Buddha Mind, understanding that the myriad of things issue from this abode which is free of mental images.

Q: Are you saying that the "Mu" I intone in my mind comes from Buddha Mind which cannot be intoned or seen?

A: Yes. However, most people are so addicted to representational thinking that they are unable to see anything besides the hua-wei side, in this case, the imagined "Mu" which is not the same as the real antecedent "Mu". Continuing this way, they will never get a glimpse of Buddha Mind. I should say, to actually merge with the hua-t'ou of "Mu" proves a great event if it is actually accomplished. But most practitioners never do it.

Q: Why is that?

A: It is because most people believe in the seen rather than the unseen. In the world of mental constructs, we have been led to believe that the source of thoughts is nothing--it is a dream. We are taught to value thoughts, schemata, feelings, desires and so on. Never once have our cultural wise men encouraged us to investigate the true source of these images.

Q: When you saw the hua-t'ou--the "pure antecedentness" as you call it--what was it like?

A: I just saw *that* which was image-free. No matter what image came before my mind I could see its hau-t'ou. It was great! I can remember the next morning as I watched the sun rise over the eastern hills and saw its hau-t'ou and jumped for joy like a madman! Then, when I went in the woods to cut firewood, I even felt the hau-t'ou of sawing wood! Even when my old fears came up, I could see the hua-t'ou. Over the years as my practice deepened, I became more of the the hau-t'ou and less and less of the hua-wei. As this happened, more of the Buddha's teaching was revealed to me. Oh, let me say this before I forget--Zen practice really begins after we see the hau-t'ou, and not before.

Q: That is very interesting. So, there comes a point when you actually "see the hua-t'ou" of "Mu". Right?

A: Yes--exactly so. No "ifs" "ands" or "buts" about it. You see *that* which no image can represent. In addition, it is like a mysterious jewel which, if you turn to it, your existence becomes more complete over time. The more you look at it, the clearer your Buddha knowledge becomes.

Q: That seems easy enough. But what about bigger koans like Hyakujo's fox? I really have a difficult time with that one. How did Hyakujo's words "The enlightened man is one with causation" free the Zen master from further rebirth as a fox?

A: The teacher of Ta-hui, Zen master Yuan-wu, said, "Do not seek for anything within the meaning of the phrase". What he was stressing is that you must learn to hear clearly outside of the phrase in the example of "The enlightened man is one with causation". That is the hua-t'ou. Do you understand?

Q: Not exactly. I am familiar with a number of interpretations of that particular koan. Do you mean they are wrong and yours is right?

A: [laughing] No, only truth has the correct answer. But let me now get to the point. Teachers who engage in looking for the various meanings in koan phrases themselves, are off the track. If a thousand Zen masters have a thousand different interpretations of Hyakujo's answer, which one should we follow? These teachers are only investigating dead words. They should see the live word that comes before all words!

Q: So what is the "live word", as you say?

A: It is where the hau-t'ou is. Exactly there! It is the source of my tongue which not even the Buddha can find! [laughing]

Q: Well, I must admit that is a pretty good answer. In other words, I have to get beyond representational thinking, as you say, and stop trying to conceptualize. By the way, I have heard a lot about "doubt" in koan practice. What does it mean?

A: When the pioneer of the koan exercise, Yuan-wu, used the expression "doubt", he meant it to refer to obstacles which Zen practitioners must overcome. Basically, in Yuan-wu's use, it is what separates us from the truth.

Q: But I read somewhere that we are supposed to cultivate "great doubt".

A: Oh, that was Ta-hui's understanding of doubt who was Yuan-wu's successor. He said that "great doubt is followed by great enlightenment", or something to that effect.

Q: What is your assessment of the way koans are practiced today?

A: To be honest, not very good. It is much like Yuan-wu's time, in which everyone was stuck on interpreting koan phrases, which, ironically, koans were designed as an antidote against. It seems to me, that we haven't changed a bit. Today, the only difference is that teachers now are analyzing koans from various psychological perspectives. They treat koans as if they were psycho-social parables which, of course, they are not.

Q: Aren't there answer to koans?

A: Not in a mundane sense, although in Japanese Rinzai Zen there are pat answers. But this is like giving out pictures of cookies to stop hunger. Thankfully, some crazy Zen master in 1916 gave out the answers to Hakuin's koan system and spared us all pictures of cookies! By the way, he called such Zen "pseudo-Zen".

Q: Does that mean, therefore, there are no answers?

A: It was never the intention of Ta-hui, or his teacher, to give 'word answers' to koans, in the case of riddles. When you penetrate the hua't'ou of the phrase you will know the right spiritual answer. If I say, "Mu" or "Cypress tree in the courtyard", or put my shoes on my head--you will understand. If I say, "Buddha" or chant a mantra, it is the same answer. That comes from seeing the hua-t'ou.

Q: Basically, you're saying that the modern practice of the koan is incorrect--right?

A: I am not going to answer that one. [laughing] I am already in hot water for my views. That is what you get for trying to be true to the original. I guess that makes me an old conservative Zennist!

Q: Well, you have to admit that what you have said so far, is not found in today's Zen books. To be honest, is your version traditional?

A: Of course, my account is traditional. On the other hand, today's so-called Zen books are, for the most part, the machinations of Pop Zennists who don't have the slightest inkling of how koans work. Basically, on this issue, Zen is divided into two camps, viz., those who wish to go beyond representational thinking and those who are using koans as a vehicle for psychological problem solving.

Q: What do you say when teachers tell their students that their own life is a koan?

A: You mean Dogen's idea? I say that they are looking in the wrong direction. Life is samsara--it never gets anywhere.

Q: Then, you don't think our life has any ultimate meaning?

A: What has ultimate meaning is the deathless hua-t'ou. In contrast with that, our body is a walking corpse looking for a grave. Yet, despite this dismal outlook, each of us has the capacity to harmonize with Buddha-nature, and by harmonizing with it, attain eternal life. After that, we will be like a swan, taking flight from a smelly old lake, flying to heaven.

Q: So, koans help us reach heaven? I can't believe that.

A: Koans help us see the immortal. By the way, I was using a metaphor from the Dhammapada. Yes, the Buddha talks about "swans" and "heaven". Sorry to rain on your parade! [laughing]

Q: It is going to take me a while to digest what you have said. For some who have spent years in study with a teacher, your words are depressing. In effect, you are suggesting that my Zen is not Zen because my answers dealt with psychological issues.

A: If I am suggesting anything it is this: China once greatly valued spirit. When the great Chinese mind developed Ch'an (Zen) it was for the purpose of spiritual transcendence--not learning how to cope with everyday life and the kids. In other words, there was only super swan flying Zen! [laughing]

Q: If Zen can't deal with common everyday issues, how can it be any good?

A: The problems people face today are not spiritual problems, but problems of desire and excess. In this regard, not even a Sage can be of any benefit. Only nature and Fate can deal with such people, teaching them their hard lessons. Spirit, on the other hand, says that if you want true happiness, leave your madhouse behind and move towards a higher level of being. The koan helps us do that.

Q: Does answering a koan correctly make one a Buddha?

A: Absolutely not. The answer only points you in the right direction. You just see a little bit of our Mr. Buddha! The insight still has to be cultivated until you manifest the state of Bodhisattva. After you become a Bodhisattva, a whole new practice evolves. Koans, after that, are like reading children's books.

Q: Does that explain why the Bodhisattva path is not mentioned very much in Zen?

A: I think so. But I should point out in Zen's beginnings, uncovered in old Tibetan manuscripts, there were roughly four kinds of Zen, viz., Gradual Zen, Sudden Zen, Mahayoga and Tathagata Zen. Mahayoga was basically the Bodhisattva path which lead to Tathagata Zen. What I think has happened now, is that Mahayoga and Tathagata Zen have been replaced by Sudden Zen. The higher forms of Zen, namely, Mahayoga and Tathagata Zen remained in Tibet and were subsequently absorbed.

Q: That is fascinating. I hope I haven't taken up too much of your time.

A: That's okay. I am glad to share my thoughts with you.

Text by Zenmar, the Dark Zen mystic

The Manual of Dark Zen – FREE BOOK GET YOUR COPY

0 notes

Note

Could you tell me any notable generals or officials under Yao Xing?

Can I interest you in one general Yang Fosong楊佛嵩? Based on his personal name, I'd say it's quite likely he was an adherent to Buddhism, his name could perhaps be translated as something like “Buddha's Eminence”. Since Yang Fusong is initially described as a “Di leader”, it's tempting to speculate that he belonged to the Yang clan of Chouchi.

Anyway Yang Fosong first appears in history in 393, Emperor Xiaowu of Jin's 18th Year of Taiyuan, as a Jin-aligned leader among the Di people. He appears to have been based in roughly eastern Guanzhong, with a following of 3 000 households, and held titles from the Jin court as General who Pacifies the Distant and Colonel who Protects the Di.

However that autumn he decided to shift his allegiance from Jin to Yao Chang and Qin. This prompted a response from the Jin commander at Luoyang, the General who Broadens Power, Yang Quanqi. He attacked and defeated Fosong in a battle at Tong Pass on 19 October 393.*

According to the Annual Records of Yao Chang in JS116, Yao Chang sent Yao Chong with an army to aid Fosong, who was now in flight from Quanqi. Chong caught up with the pursuing Jin army and defeated them, and the Jin commander Zhao Mu was killed.

The Biography of Yang Quanqi in JS084 must also be referring to this campaign, when it writes that “he entered Tong Pass from Hucheng, in amassed battles was always victorious, the beheaded and captives numbered in the thousands. He took the surrender of more than nine hundred families, and returned to Luoyang. He was advanced in title to Dragon-Prancing General.”

(* JS009 dates this battle to the 9th Month, bingxu, however there was no bingxu in the 9th Month that year, the closest was the 28th Day of the 8th Month, which was 19 October.)

Having successfully joined Qin, Yang Fosong was appointed General who Garrisons the East. Yao Chang died the next year, 394, and was succeeded by his son Yao Xing. On Xing's ascension, Yang Fosong was rewarded with noble title, either as Duke or Marquis.

Winter 395/396 Murong Chui of Later Yan sent his son Bao to attack Wei. Wei at time were on friendly terms with Qin, and the ruler of Wei, Tuoba Gui (temple name Taizu), asked Yao Xing for assistance. WS024, Biography of Xu Qian, writes:

Taizu sent [Xu] Qian to report the difficulties to Yao Xing. Xing dispatched general Yang Fosong to lead the multitudes to come and aid, but Fosong was slow and tardy. Taizu instructed Qian to make a letter to dispatched to Fosong, saying:

In all cases when relying on complying so as to cut away neglect, take advantage of righteousness and attack the dull-minded. There has never been someone who has faults in his wielding and yet are distinguished in achievements, who are not in time and yet puts forth a legacy.

The Murong are without the Way, and are invading on our frontier and border. The host is waning and the troops exhausted, Heaven's appointed time for perishing arrives. Thus hence dispatched [you] to make instructions for the army, surely expecting [you] to overcome and bring about.

You General depend on the duties of Fang and Shao, commanding a host of bears and tigers, affairs provides a crucial moment, now is the time. To follow this and take the lead is a service not twice driven, the achievement of a thousand years in a single morning it can established.

Afterwards at the exalted meeting in Yunzhong, advancing the host through the Three Wei, raising a toast and wishing for long life, would it not likewise be serene?

Fusong therefore made combined marches over multiple roads. Taizu was greatly pleased, he bestowed on Qian feudal title of Marquis Inside the Passes, and once more dispatched Qian to swear a covenant with Fusong, saying:

In the past Tang of Yin had the oath of Mingtiao. Wu of Zhou had the covenant of Heyang, by those means they depended on the gods and spirits, and illuminated loyalty and trust. In all cases, to be friendly and humane and good neighbours was the order and guideline of the ancients, and to smear the mouth with blood and cut the sacrificial animal so as to hold high forever cordiality. Now after having sworn, [we] speak of returning to their excellence, to split calamities and be compassionate in misfortune, fortune and distress truly to be the same. If someone disobeys this oath, the gods and the revered then put him to death.

When Bao was defeated, Fosong then turned back.

In 399 Yang Fosong was sent to attack Luyang (an earlier attack in 397 commanded by Yao Chong had failed). On their side, the Jin sent the General who Establishes the Martial, Xin Gongjing, to strengthen the defences. The city held out for a hundred days until finally falling in the 10th Month (15 November – 13 December). Xin Gongjing was captured.

The fall of Luoyang happened just months before Sun En's uprising in Kuaiji, and at the same time Huan Xuan was attacking the provincial governors before eventually marching on the capital and taking over the state. All was not well in the Jin empire, and there were many defections to Qin.

In c. 403? Jin's Grand Warden of Shunyang, Peng Quan, decided to surrender to Qin. This commandery was located south of Luoyang and north-east of Xiangyang. Yao Xing sent Yang Fosong with Qin's Inspector of Jing province and 5 000 cavalry to support him. They also attacked and captured the neighbouring commandery of Nanxiang, before heading east, plundering as far as Liang state before turning back.

In 409 Yao Xing sent his youngest brother, Yao Chong# to command the northern army in a campaign against Helian Bobo, Yang Fosong was named one of Chong#'s three subordinate generals. This campaign never got going, as Yao Chong# instead wanted to use the army to launch a coup against his brother. This plan also never got anywhere since Chong#'s second in command, Di Bozhi, refused to go along. Chong# had Bozhi poisoned, but the plot leaked out anyway, and Chong# was ordered to commit suicide.

Sometime in 411, according to the Annual Records of Yao Xing, JS118, the Qin commander at Xuchang came to Chang'an for a visit, and the following took place:

The Grand Warden of Yingchuan, Yao Pingdu, came to court from Xuchang. He talked to Xing, saying:

Liu Yu dares in his breast to have perfidious plans. He is stationed at Jushao Slope and has aspirations of disturbing the border. [We] ought to dispatch to burn him and so disperse his multitudes and plans.

Xing said:

[Given] Yu's fragility and weakness, how dares he spy on my borders and frontiers! If anyone has a perfidious heart, it will be his sons and grandsons!

He summoned his Master of Writing, Yang Fosong, and spoke to him, saying:

The Wu boy does not understand himself, and therefore has thoughts not of his allotment. [I] will wait until the first of winter to dispatch a minister to lead 30 000 finest cavalry to burn his assembled stockpiles.

Song said:

Suppose Your Majesty relies on Your Subject for this service, [I] will follow the mouth of the Fei to cross the Huai, straight-away hasten for Shouchun, raise up a great multitude so as to garrison the city, give free reign to the light cavalry to plunder the countryside, and make South of the Huai barren and bleak. Troops and grain will be all together finished. Enough to cause the Wu boy to instantly turn around in fear, his spirit and briskness flying far away.

Xing was greatly pleased.

Alas, this plan would never be carried out. Later the same year:

Used Yang Fosong as Commander-in-Chief of All Army Affairs in Chastising the Caitiffs North of the High Passes, General who Calms the Distant, and Inspector of Yong province, to lead the troops at present north of the High Passes and so chastise Helian Bobo. Several days after Song set out, Xing spoke to the crowd of subjects, saying:

Fosong is brave, fierce, resolute and sharp, always when approaching the enemy or responding to robbers, he cannot hold back or restrain [himself]. I have often moderated him and paired him with troops not exceeding 5 000. Now the multitudes travelling have become many, [if he] meets the thieves [he] will surely be defeated. Now his departure is already far off, pursuers would not catch up. I am deeply anxious about it.

Everyone of his subordinates considered it not to be so. Fosong as a result was seized by Bobo, he cut his throat and died.

According to the Annual Records of Helian Bobo, JS130:

That year (411), Bobo led 30 000 cavalry to attack Chang'an, he fought with Yao Xing's general Yang Fosong on the plain north of Qingshi, and defeated him. He took the surrender of his multitude of 45 000, and captured 20 000 military horses.

ZZTJ116 makes these two different battles, but that seems to me quite unlikely? In any case, here ends the story of Yang Fosong.

8 notes

·

View notes