#Black In America

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Nostalgia💚

We all we got

#black people#black history#black power#black stories#black beauty#nostalgia#nostalgic#new york#soft ghetto#black culture#melanin#black girl moodboard#black men#aesthetic#back in the day#lifestyle#gentillmatic#black tumblr#black in america#blacklivesmatter#black women#black kids#black children#black youth#beauty#soulaan#soulaani#hoodoo#black spirituality#not like us

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently. When anybody black participating. 😭😂

665 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perfectly said. Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu are not the sole problem. They are a symptom of the problems

#jews for palestine#jews for ceasefire#free gaza#free palestine#jews for peace#israel#anti zionisim#colonialism#gaza#decolonise palestine#USA#israel is committing genocide#Palestine#falestine#amerikkka#israel is an apartheid state#jumblr#jewblr#am yisrael chai#politics#systems of oppression#systemic injustice#black in america#donald trump#benjamin netanyahu#satanyahu#trump#fuck israel

385 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Woman behind PlayBoy.

Zelda Wynn Valdes

#black history#black women#playboy magazine#playboy bunny#fashion#black owned#black owned business#black people#black excellence#fashion desingers#fashion design#black inventors#black in america

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zendaya for usaella

#african beauty#black in america#zenday coleman#zendaya#african women#dark skin#dark skin beauty#ella usa#high fashion#usa fashion#american fashion#american photographer

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

#black inventors#black entrepreneurs#black excellence#black economics#black owned businesses#black women#entrepreneur#black in america#Instagram

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

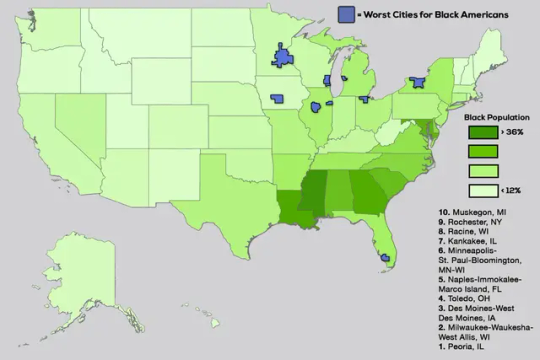

Where It’s Most Dangerous to Be Black in America

Black Americans made up 13.6% of the US population in 2022 and 54.1% of the victims of murder and non-negligent manslaughter, aka homicide. That works out, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, to a homicide rate of 29.8 per 100,000 Black Americans and four per 100,000 of everybody else.(1)

A homicide rate of four per 100,000 is still quite high by wealthy-nation standards. The most up-to-date statistics available from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development show a homicide of rate one per 100,000 in Canada as of 2019, 0.8 in Australia (2021), 0.4 in France (2017) and Germany (2020), 0.3 in the UK (2020) and 0.2 in Japan (2020).

But 29.8 per 100,000 is appalling, similar to or higher than the homicide rates of notoriously dangerous Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. It also represents a sharp increase from the early and mid-2010s, when the Black homicide rate in the US hit new (post-1968) lows and so did the gap between it and the rate for everybody else. When the homicide rate goes up, Black Americans suffer disproportionately. When it falls, as it did last year and appears to be doing again this year, it is mostly Black lives that are saved.

As hinted in the chart, racial definitions have changed a bit lately; the US Census Bureau and other government statistics agencies have become more open to classifying Americans as multiracial. The statistics cited in the first paragraph of this column are for those counted as Black or African American only. An additional 1.4% of the US population was Black and one or more other race in 2022, according to the Census Bureau, but the CDC Wonder (for “Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research”) databases from which most of the statistics in this column are drawn don’t provide population estimates or calculate mortality rates for this group. My estimate is that its homicide rate in 2022 was about six per 100,000.

A more detailed breakdown by race, ethnicity and gender reveals that Asian Americans had by far the lowest homicide rate in 2022, 1.6, which didn’t rise during the pandemic, that Hispanic Americans had similar homicide rates to the nation as a whole and that men were more than four times likelier than women to die by homicide in 2022. The biggest standout remained the homicide rate for Black Americans.

Black people are also more likely to be victims of other violent crime, although the differential is smaller than with homicides. In the 2021 National Crime Victimization Survey from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (the 2022 edition will be out soon), the rate of violent crime victimization was 18.5 per 1,000 Black Americans, 16.1 for Whites, 15.9 for Hispanics and 9.9 for Asians, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Understandably, Black Americans are more concerned about crime than others, with 81% telling Pew Research Center pollsters before the 2022 midterm elections that violent crime was a “very important” issue, compared with 65% of Hispanics and 56% of Whites.

These disparities mainly involve communities caught in cycles of violence, not external predators. Of the killers of Black Americans in 2020 whose race was known, 89.4% were Black, according to the FBI. That doesn’t make those deaths any less of a tragedy or public health emergency. Homicide is seventh on the CDC’s list of the 15 leading causes of death among Black Americans, while for other Americans it’s nowhere near the top 15. For Black men ages 15 to 39, the highest-risk group, it’s usually No. 1, although in 2022 the rise in accidental drug overdoses appears to have pushed accidents just past it. For other young men, it’s a distant third behind accidents and suicides.

To be clear, I do not have a solution for this awful problem, or even much of an explanation. But the CDC statistics make clear that sky-high Black homicide rates are not inevitable. They were much lower just a few years ago, for one thing, and they’re far lower in some parts of the US than in others. Here are the overall 2022 homicide rates for the country’s 30 most populous metropolitan areas.

Metropolitan areas are agglomerations of counties by which economic and demographic data are frequently reported, but seldom crime statistics because the patchwork of different law enforcement agencies in each metro area makes it so hard. Even the CDC, which gets its mortality data from state health departments, doesn’t make it easy, which is why I stopped at 30 metro areas.(2)

Sorting the data this way does obscure one key fact about homicide rates: They tend to be much higher in the main city of a metro area than in the surrounding suburbs.

But looking at homicides by metro area allows for more informative comparisons across regions than city crime statistics do, given that cities vary in how much territory they cover and how well they reflect an area’s demographic makeup. Because the CDC suppresses mortality data for privacy reasons whenever there are fewer than 10 deaths to report, large metro areas are good vehicles for looking at racial disparities. Here are the 30 largest metro areas, ranked by the gap between the homicide rates for Black residents and for everybody else.

The biggest gap by far is in metropolitan St. Louis, which also has the highest overall homicide rate. The smallest gaps are in metropolitan San Diego, New York and Boston, which have the lowest homicide rates. Homicide rates are higher for everybody in metro St. Louis than in metro New York, but for Black residents they’re six times higher while for everyone else they’re just less than twice as high.

There do seem to be some regional patterns to this mayhem. The metro areas with the biggest racial gaps are (with the glaring exception of Portland, Oregon) mostly in the Rust Belt, those with the smallest are mostly (with the glaring exceptions of Boston and New York) in the Sun Belt. Look at a map of Black homicide rates by state, and the highest are clustered along the Mississippi River and its major tributaries. Southern states outside of that zone and Western states occupy roughly the same middle ground, while the Northeast and a few middle-of-the-country states with small Black populations are the safest for their Black inhabitants.(3)

Metropolitan areas in the Rust Belt and parts of the South stand out for the isolation of their Black residents, according to a 2021 study of Census data from Brown University’s Diversity and Disparities Project, with the average Black person living in a neighborhood that is 60% or more Black in the Detroit; Jackson, Mississippi; Memphis; Chicago; Cleveland and Milwaukee metro areas in 2020 (in metro St. Louis the percentage was 57.6%). Then again, metro New York and Boston score near the top on another of the project’s measures of residential segregation, which tracks the percentage of a minority group’s members who live in neighborhoods where they are over-concentrated compared with White residents, so segregation clearly doesn’t explain everything.

Looking at changes over time in homicide rates may explain more. Here’s the long view for Black residents of the three biggest metro areas. Again, racial definitions have changed recently. This time I’ve used the new, narrower definition of Black or African American for 2018 onward, and given estimates in a footnote of how much it biases the rates upward compared with the old definition.

All three metro areas had very high Black homicide rates in the 1970s and 1980s, and all three experienced big declines in the 1990s and 2000s. But metro Chicago’s stayed relatively high in the early 2010s then began a rebound in mid-decade that as of 2021 had brought the homicide rate for its Black residents to a record high, even factoring in the boost to the rate from the definitional change.

What happened in Chicago? One answer may lie in the growing body of research documenting what some have called the “Ferguson effect,” in which incidents of police violence that go viral and beget widespread protests are followed by local increases in violent crime, most likely because police pull back on enforcement. Ferguson is the St. Louis suburb where a 2014 killing by police that local prosecutors and the US Justice Department later deemed to have been in self-defense led to widespread protests that were followed by big increases in St. Louis-area homicide rates. Baltimore had a similar viral death in police custody and homicide-rate increase in 2015. In Chicago, it was the October 2014 shooting death of a teenager, and more specifically the release a year later of a video that contradicted police accounts of the incident, leading eventually to the conviction of a police officer for second-degree murder.

It’s not that police killings themselves are a leading cause of death among Black Americans. The Mapping Police Violence database lists 285 killings of Black victims by police in 2022, and the CDC reports 209 Black victims of “legal intervention,” compared with 13,435 Black homicide victims. And while Black Americans are killed by police at a higher rate relative to population than White Americans, this disparity — 2.9 to 1 since 2013, according to Mapping Police Violence — is much less than the 7.5-to-1 ratio for homicides overall in 2022. It’s the loss of trust between law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve that seems to be disproportionately deadly for Black residents of those communities.

The May 2020 murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer was the most viral such incident yet, leading to protests nationwide and even abroad, as well as an abortive local attempt to disband and replace the police department. The Minneapolis area subsequently experienced large increases in homicides and especially homicides of Black residents. But nine other large metro areas experienced even bigger increases in the Black homicide rate from 2019 to 2022.

A lot of other things happened between 2019 and 2022 besides the Floyd protests, of course, and I certainly wouldn’t ascribe all or most of the pandemic homicide-rate increase to the Ferguson effect. It is interesting, though, that the St. Louis area experienced one of the smallest percentage increases in the Black homicide rate during this period, and it decreased in metro Baltimore.

Also interesting is that the metro areas experiencing the biggest percentage increases in Black residents’ homicide rates were all in the West (if your definition of West is expansive enough to include San Antonio). If this were confined to affluent areas such as Portland, Seattle, San Diego and San Francisco, I could probably spin a plausible-sounding story about it being linked to especially stringent pandemic policies and high work-from-home rates, but that doesn’t fit Phoenix, San Antonio or Las Vegas, so I think I should just admit that I’m stumped.

The standout in a bad way has been the Portland area, which had some of the longest-running and most contentious protests over policing, along with many other sources of dysfunction. The area’s homicide rate for Black residents has more than tripled since 2019 and is now second highest among the 30 biggest metro areas after St. Louis. Again, I don’t have any real solutions to offer here, but whatever the Portland area has been doing since 2019 isn’t working.

(1) The CDC data for 2022 are provisional, with a few revisions still being made in the causes assigned to deaths (was it a homicide or an accident, for example), but I’ve been watching for weeks now, and the changes have been minimal. The CDC is still using 2021 population numbers to calculate 2022 mortality rates, and when it updates those, the homicide rates will change again, but again only slightly. The metropolitan-area numbers also don’t reflect a recent update by the White House Office of Management and Budget to its list of metro areas and the counties that belong to them, which when incorporated will bring yet more small mortality-rate changes. To get these statistics from the CDC mortality databases, I clicked on “Injury Intent and Mechanism” and then on “Homicide”; in some past columns I instead chose “ICD-10 Codes” and then “Assault,” which delivered slightly different numbers.

(2) It’s easy to download mortality statistics by metro area for the years 1999 to 2016, but the databases covering earlier and later years do not offer this option, and one instead has to select all the counties in a metro area to get area-wide statistics, which takes a while.

(3) The map covers the years 2018-2022 to maximize the number of states for which CDC Wonder will cough up data, although as you can see it wouldn’t divulge any numbers for Idaho, Maine, Vermont and Wyoming (meaning there were fewer than 10 homicides of Black residents in each state over that period) and given the small numbers involved, I wouldn’t put a whole lot of stock in the rates for the Dakotas, Hawaii, Maine and Montana.

(https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/14/where-it-s-most-dangerous-to-be-black-in-america/cdea7922-52f0-11ee-accf-88c266213aac_story.html)

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇺🇸

#agent orange#america#bernie mac#iykyk#black men#black in america#the election 2024#the election circus

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am not insulting anyone, I am only saying my experience. (I wrote and drafted this from February 2024)

I never really talk about it. But at my school I have encountered comments I hadn’t had before.

I’m from the south, but, my area is a diverse place.

When I got to my (college) school. This was the first time I was in a truly white space. Not to say that’s a bad thing.

However I started to get comments I didn’t before. (From people who weren’t black and who are)

People made comments about my hair, called me “white washed”,talked about my skin tone, I’m not “black enough”.

Even in the spaces I pride myself in such as my majors and extracurriculars, I’m always treated second best. Even when I put my first and best foot forward. I work so hard for to be the second thought. When it comes to my involvement is theaters I am treated less than. I try my best to shine because if I the one to lag behind everyone gets frustrated but when others have a hard day it is taken into consideration. Even simple things like everyone get multiple costume change but me. I look around and I realize I’m the after thought.

It was strange and offended me when it was happening.

First off, calling me “white washed” or “not black enough” was horrible in itself. When I hear that I hear people only thinking that black people are a monolith. People who say that think that I can’t have my own interest, own hobbies, and ideas that they haven’t seen before. Then if I ask “what is black to you?” It is followed by a bunch of stereotypes that are pushed on black women. And if you don’t fit it people who aren’t black tell me a black person, I can’t meet the requirements.

Second the talking about my hair. That one cut deep. I see people talk about black hair online, but experiencing it in person was so painful. My hair was called unkept, needed to not be neat, wild, interesting, etc.

Also there are comments that I couldn’t wear the clothes I like and the style I chose to style for myself because it isn’t “black”

So since when was a bow and a pink skirt only for one group of people. When did pink makeup and cute clothes for one group. Like for example. In my opinion there is no vintage Americana without including black women and their style from the 50-70s.

There is no soft r&b, pop, jazz, rock, country that most favorite peoples artist sing.

(Now once again, I am not insulting anyone, I am only saying my experience.)

This is why I have my page. I created to open a space to show black people, to show that black women are beautiful, can have hobbies, can be feminine. Because there are still people who think otherwise. Black women are not included in a lot of spaces. So I made a space. And anyone is welcome to view this page and bask in the light. I post relatable content as well. And just fem things altogether!

#coquette#dollette#pink aesthetic#black coquette#coquette dollete#kawaii#pinkcore#coquette blackgirl#soft black girls#pastel pink#theatre#actor#black femininity#black in america#black in white spaces

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey guys! I have to work on building an audience for my YouTube channel for a class!

I would really appreciate if you checked out my channel and subscribed to it🥹 making YouTube videos is really nerve wracking for me right now as creativity has been a bit of a difficult feat but I’m working on it :)

I put a lot of tags but everything in the tags is what I have already posted or plan to post.

I will be talking about how I study Korean and other languages in the long form videos and just general talk about what I did during study abroad and being a black woman in east Asia.

#pidgin#pidgin doll#ateez#black art#artwork#black excellence#fashion#fashion illustration#fashion design#travel#Korea#korea travel#gwangju#Seoul#solo travel#study abroad#black woman#black woman travel#black and beautiful#black in Asia#black in America#culture shock#reverse culture shock#mental health#mental illness#major depressive disorder#Depop#traditional art#posca pens#posca

25 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

James Baldwin on the Black Experience in America

From a 1960 Canadian television interview, broadcaster Nathan Cohen talks to author James Baldwin about race relations and the Black experience in the United States.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can’t get over Julianna Margulies saying

“…as someone who plays a lesbian on tv…I’m more offended as a lesbian than a Jew.”

…playing a lesbian on tv does not, in fact, make you a lesbian.

Julesy, baby, is you okay?

The icing on the cake really is the full-on white woman lemme speak to yo manageh tone she used talking about the monolith that is the black lesbian people.

I’m not listening to that podcast but there are clips posted and I…can’t. I just caaaaan’t.

Another Julianna Margulies pearl of wisdom:

“I was the first person to march in Black Lives Matter. When that happened to George Floyd I put a black screen on my Instagram. Like I ran to support my black brothers and sisters. When LGBTQ people are being attacked I run. I make a commercial for same sex marriages with my husband in 2012. Like I’m the first person to jump up when something is wrong.”

Babes, you…put a black screen on your IG and made a commercial with your straight male husband (so, this means you are, in fact, not a lesbian, okay?)…like goddamn, what do you want? A damn Human Rights award?

…listens to another clip

*brain explodes*

Ma’am…uh, Miss Julianna Margulies, ah, did you just…did you just tell…did you just…tell young black people to…uhm,

“Get the fuck out of America. Because you were not here first. Native Americans were here and you owe them a big fucking apology and move the fuck out.”

Uhm…this is a rant Julianna Margulies had saying that black people who support not the Jewish people are uneducated.

So. Much. To. Unpack.

I don’t know what’s more unhinged…the constant interpretation that black people are a monolith, that black lesbians are a monolith, the get the fuck out or the not here first or Black people owe Native Americans an apology…while a white woman is saying this with her entire chest.

Girl, I need a fucking drink.

#julianna margulies#the morning show#apple tv#lesbians#black people#podcast#black lesbians#julianna margulies is confused about being gay#julianna margulies said WHAT#the good wife#justice for archie panjabi#archie panjabi#black in america#racism#the quiet part out loud#confidently ignorant

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Beloved,” at its core, is a story of multiple hauntings: The remnants of trauma left in those forced to be property, the fury of a petulant baby spirit that seems to come back from the dead to find the mother who killed her rather than let her be taken into enslavement. The book holds horrors but also questions the beginning of freedom time. “Freeing yourself was one thing,” Morrison writes, “but claiming ownership of that freed self was another.” The work of embodiment, belonging, and rest become the central themes for the characters and, by extension, the readers. For Sharpe, “Beloved” is rich in techniques for refusing the logic of slavery. One is infanticide; another, Sharpe shared with the class, is love.

She held the book and read the title aloud: “Beloved.” She paused and reframed the word for us. “Be loved.” Sharpe told the class that the book's name is “an injunction, a command, a wish, a plea, a lamentation.” To love the self, to believe the self is worthy of love, and to let that love radiate out and fill up others around you.

A thick silence settled over the classroom as the students absorbed the force of the revelation. The first and final words of the book were not merely an epitaph on a grave: They were instructions for living. Be loved. What I was witnessing, I later realized, was more than a lecture. It was a portal into Sharpe’s methodology.

“I think with ‘Beloved’ almost every day.”

—Jenna Wortham

#race in america#black in america#christina sharpe#jenna wortham#beloved#toni morrison#black thought#black ideology#academia#be loved

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

So like… Any of yall got like, a spare ticket to anywhere outside the us (NOT ENGLAND)

4 notes

·

View notes