#Black Health Disparities

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

More than two and a half years after a law took effect requiring maternity care staff to complete racism in medicine training, only 17% of hospitals were in compliance, according to an investigation recently published by the state Department of Justice.

The training matters, Attorney General Rob Bonta and others said during a press conference, because of the state’s persistently high death rates among Black mothers.

Though California is often looked at as a national model for improving maternal outcomes, Black women are still far more likely than others to die during pregnancy. They account for only 5% of pregnancies in the state but make up 21% of pregnancy-related deaths, according to the California Department of Public Health.

The mortality rate for Black infants is also three times higher than for white infants and nearly 1.5 times higher than for Pacific Islander babies, the second highest mortality rate, state data shows.

Investigations into the cause of all pregnancy-related deaths by the California Department of Public Health determined that more than half are preventable.

“We need to listen to this data. It’s screaming at us to do something,” Bonta said. “Listen to these women and make substantial transformative change before another patient is hurt, or worse.”

No hospitals were in compliance when the department began its investigation in 2021, and not a single employee had completed training.

Lawmakers passed the California Dignity in Pregnancy and Childbirth Act four years ago in an effort to reverse the vast disparities in maternal deaths among Black women, who are three times more likely than any other race to die during or immediately after pregnancy. The law requires hospitals and other facilities to train perinatal care providers on unconscious bias in medicine and racial disparities in maternal deaths. It took effect in January 2020.

Bonta recommended lawmakers adopt additional regulations to strengthen the law, including setting clear deadlines for compliance, designating a state agency to enforce the law and introducing penalties for noncompliance.

Former state Sen. Holly Mitchell, the Los Angeles Democrat who authored the bill, said “clearly more must be done” to implement the policy.

"It is my full expectation that every hospital across L.A. County and across the state join in making sure that their staff take the training,” said Mitchell, who is now a Los Angeles County supervisor. “We are simply asking them to follow the law.”

According to the department’s investigation report, about 76% of more than 200 hospitals surveyed had begun training employees by August 2022 but had not completed training. Two hospitals had not fully trained any staff, and 13 did not provide the department with any information.

“Nearly a third of facilities to which DOJ reached out began training only after DOJ contacted them, suggesting that DOJ’s outreach caused compliance in many cases,” the report states.

Black women report mistreatment at hospitals

It is well-documented that racism in health care settings contributes to poor outcomes. Black women in California consistently report poor experiences with medical professionals during pregnancy, including mistreatment because of their “race, age, socioeconomic class, sexuality, and assumed or actual marital status,” according to a recent research review and report by the California Department of Public health.

They also struggle to convince providers that they are in pain and report mistreatment when advocating for their health during pregnancy. A national survey from 2016 revealed half of white medical students and residents believed false and debunked myths about the biological differences between white and Black patients. Those who endorsed the beliefs were more likely to dismiss patients’ pain and make inaccurate treatment decisions.

“What is so deeply offensive about that is it is within our power to change,” Mitchell said.

Implicit bias training is the “bare minimum” of what health professionals can do to improve outcomes, said Assemblymember Akilah Weber, a Democrat from La Mesa and a medical doctor.

Research also shows maternal and infant health disparities among Black women and babies persist regardless of patients’ education or income levels. Celebrities like Serena Williams and Beyoncé have spoken out about their near-death experiences during childbirth.

Recent maternal deaths in Los Angeles

Earlier this year, the deaths of two Black women, Bridgette Cromer and April Valentine, in childbirth shook Los Angeles. Valentine’s death led to a state investigation and a $75,000 fine levied against Centinela Hospital Medical Center where her daughter was delivered via C-section. The investigation stated the hospital “failed to prevent the deficiencies…that caused, or are likely to cause, serious injury or death” to Valentine,, including repeated failure to take steps to prevent blood clots, a common pregnancy risk, even when Valentine complained of feeling heaviness in her leg, numbness and leg swelling.

The Los Angeles County Medical Examiner determined she died from a blood clot that traveled from her leg into her lungs.

Centinela announced its intent to close the maternity ward permanently days after Valentine’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit. The maternity ward, which delivered more than 700 babies last year, closed last week.

In a GoFundMe post, Cromer’s family said they did not have autopsy results yet but noted that she was readmitted into the operating room after birth with major bleeding before dying.

Gabrielle Brown, an advocate with Black Women for Wellness, said Centinela’s maternity ward closure is “a stark reminder of how healthcare disparities persist in our society.”

“It reminds us of the implicit biases that have subtly influenced healthcare decisions, ultimately leading to an immense reduction in the accessibility and quality of care for many members of our community,” Brown said.

Supported by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), which works to ensure that people have access to the care they need, when they need it, at a price they can afford. Visit www.chcf.org to learn more.

#Despite high Black maternal death rate#California hospitals ignored training about bias in care#Black Maternal Death Rate#California#Black Birth Safety Statistics#Giving Birth to a Black Baby#Black Babies#Black Mothers#Black Women#Black Health Disparities#bias in medicine#racism

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine how many people JUST LIKE HER are in ICU, TRAUMA, BIRTH AND DELIVERY, NICU, STEP-DOWN UNITS, PYSCH WARDS, ELDERLY CARE, OBGYN, CARDIOLOGY, POST OP CARE, etc…

#indiana state university#protest#racism#hate speech#campus activism#cowboy carter#beyoncé#country music#yik yak#student activism#campus response#discrimination#protest demands#campus culture#university response#social media#campus newspaper#diversity#inclusion#racial discrimination#Code of Conduct#university administration#health care disparities#Black maternal health#structural racism#health care professionals#systemic inequities

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mayor Eric Adams’ administration is promoting reparations in a bid to curb health and wealth disparities of black New Yorkers — but the effort is being met with accusations that it’s “sowing racial divisiveness,” The Post has learned.

The proposal for federal reparations is spelled out in a bombshell report from the city’s Department of Health and the Federal Reserve Bank entitled “Analyzing the Racial Wealth Gap and Implications for Health Equity.”

“The goal of a [federal] reparations program would be to seek acknowledgment, redress, and closure for America’s complicity in federal, state, and local policies … that have deprived black Americans of equitable access to wealth and wealth-building opportunities,” the report said.

The city’s Health Commissioner Dr. Ashwin Vasan and his team offered three key recommendations including: a fresh approach to public health policy, how to improve data collections on wealth and health outcomes and getting the community more involved with health care decisions.

But moderate and conservative politicians opposed to reparations accused Adams’ health minions of turning into ideologues and social justice activists instead of doing their jobs.

“Add reparations and sowing racial divisiveness to the list of greatest policy hits by Commissioner Vasan’s and his health department, right alongside the crack pipe vending machine, heroin ‘empowerment’ signs on subways, firing unvaccinated city workers, supporting government drug dens; and banning unvaccinated kids from sports,” fumed Council Republican Minority Leader Joe Borelli (R-Staten Island).

The New York legislature approved a commission to address economic, political and educational disparities by black people in June and follows the lead of California, which became the first state to form a reparations task force in 2020.

New York Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie, the first black person to hold the position, called the legislation “historic.”

Adams has previously expressed support for the commission which is awaiting Hochul’s signature.

“We have consistently brought together experts to discuss a variety of ideas to promote equity in our city and we will continue to do so,” said the Health Department’s spokesman.

“We have an obligation to help New Yorkers lead longer, healthier lives.”

As with most progress in this system, we have to first inspect its ongoing involvement in pro enslavement systems. Not only did the historical ties to the Trans-Atlantic-slave trade leave on going structural residual connections that linger in our society today, it continues to exist in the 13th amendment's clause: slavery illegal unless a crime was found on you. That "unless" aspect made it essentially persist as is under the guise of hyper-criminalization at a system level. This has had adverse, negative effect on everyone including the environment. These are facts that can be proven. Not just social justice counter points. Besides, we are literally (regardless of what we say about it) immersed in politics and social justice through our lived social experiences. Claiming "the social justice advocates are the issue for pointing out what exists" is not helpful and adds to the lack of communal education required to understand these things. We need problack proindigenx reperations and restituion.

#health#wealth#disparity#equity#science#heal department#reparations#trans atlantic slave trade#white supremacy#black people#federal#ny#nyc#america

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Tumblr! Black women in the US are at a higher risk of dying from pregnancy-related complications. Let's address this issue during Black Maternal Health Week. We can eliminate racial disparities in maternal health by addressing systemic racism and poverty and supporting access to quality healthcare services. Join us in advocating for policy changes and supporting community-based organizations working towards improving maternal health outcomes for Black women.

Black Maternal Health Week: Addressing Racial Disparities in Maternal Health

Maternal health is an essential issue in the United States, and Black Maternal Health Week is a week-long initiative aimed at addressing the racial disparities in maternal health outcomes. The week takes place every year from April 11th to April 17th, and it is an opportunity to raise awareness about the challenges faced by Black women during pregnancy and childbirth. The Centers for Disease…

View On WordPress

#Black Community#Black Lives Matter#Black Maternal Health Week#Black Moms Matter#Community Support#Health Disparities#Maternal Health#Maternal Mortality#Racial Justice#Reproductive Justice#Support Black Women

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

From birth to death, legacy of racism lays foundation for Black Americans' health disparities

PLEASE CLICK THE TITLE GRAPHIC TO SEE THE GRAPHIC PRESENTATION -

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Black Paraphernalia have posted a overview excerpt summary of a NIH study that was done. This subject is a very near to our heart and we being health care professionals who read many research studies in general and understand the double and triple risk a black woman face on a day to day but especially when it come to maternal care in the United States started with SLAVERY.

We decided to do a few post on Black women and Childbirth disparities and injustices in the medical arena. The sad thing even as health care license professionals, we have experienced covert discrimination and disparity when it came to our own professional positions and personal health.

This is the first of a few posts that we will present in hopes of B1 community awareness. Please check out this post and others to come.

For the entire study click on the title to read in full.

Health Equity Among

Black Women in the United States

Journal of Women's Health NIH - The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health

J Womens Health (Larchmt). February 2021; 30(2): 212–219.Published online 2021 Feb 2. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8868

Black women in the United States experienced substantial improvements in health during the last century, yet health disparities persist. Black women continue to experience excess mortality relative to other U.S. women, including—despite overall improvements among Black women—shorter life expectancies and higher rates of maternal mortality.

Moreover, Black women are disproportionately burdened by chronic conditions, such as anemia, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and obesity. Health outcomes do not occur independent of the social conditions in which they exist.

The higher burden of these chronic conditions reflects the structural inequities within and outside the health system that Black women experience throughout the life course and contributes to the current crisis of maternal morbidity and mortality. The health inequities experienced by Black women are not merely a cross section of time or the result of a singular incident.

No discussion of health equity among Black women is complete unless it considers the impacts of institutional- and individual-level forms of racism and discrimination against Black people. Nor is a review of health equity among Black women complete without an understanding of the intersectionality of gender and race and the historical contexts that have accumulated to influence Black women's health in the United States.

Research consistently has documented the continued impacts of systematic oppression, bias, and unequal treatment of Black women. Substantial evidence exists that racial differences in socioeconomic, education and employment and housing outcomes among women are the result of segregation, discrimination, and historical laws purposed to oppress Blacks and women in the United States.

The intersectionality of gender and race and its impact on the health of Black women also is important. This intersection of race and gender for Black women is more than the sum of being Black or being a woman: It is the synergy of the two. Black women are subjected to high levels of racism, sexism, and discrimination at levels not experienced by Black men or White women.

In contrast to Black women, White women in the United States have benefited from living in a politically, culturally, and socioeconomically White-dominated society. These benefits accumulate across generations, creating a cycle of overt and covert privileges not afforded to Black women.

The history of Black women's access to health care and treatment by the U.S. medical establishment, particularly in gynecology, contributes to the present-day health disadvantages of Black women. Health inequality among Black women is rooted in slavery. White slaveholders viewed enslaved Black women as a means of economic gain, resulting in the abuse of Black women's bodies and a disregard for their reproductive health. Black women were forced to procreate, with little or no self-agency and limited access to medical care.

The development of gynecology as a medical specialty in the 1850s ushered in a particularly dark period for the health of Black women. With no regulations for the protection of human subjects in research, Black women were subjected to unethical experimentation without consent. Even in more contemporary times, these abuses continue.

As a result of this history and the accumulation of disadvantages across generations, Black women are at the center of a public health emergency. Maternal mortality rates for non-Hispanic Black women are three to four times the maternal mortality rates of non-Hispanic White women.In

Racism and gender discrimination have profound impacts on the well-being of Black women. Evidence-based care models that are informed by equity and reproductive justice frameworks (reproductive rights as human rights need to be explored to address disparities throughout the life course, including the continuum of maternity care, and to ensure favorable outcomes for all women.

Health does not exist outside its social context. Without equity in social and economic conditions, health equity is unlikely to be achieved,and one cost of health inequality has been the lives of Black women.

The above is a summary excerpt take from the study by the Journal of Women's Health NIH - The National Center for Biotechnology Information advances science and health

BLACK PARAPHERNALIA DISCLAIMER - PLEASE READ

#black paraphernalia#disparity in black women health care#maternal deaths in healthcare with black women#the worst sight

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Health inequities are widespread in pediatric medicine, researchers find : Shots - Health News : NPR

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey @kojoty how's it going

my heavy smoker grandparents came over very briefly and the whole house smells like absolute shit now. So I (chronic tumblrina) got thinking.

#fascinating take#we gotta put classism up on the shelf too or#i come from a low income majority black-hispanic community and plenty of people around here dont smoke#no one in my family smokes#yeah if you smoke youre consciously choosing to ignore the negative impact smoking will have on your health#like ofc there is a class disparity#but its also really easy to just start smoking#and every black low class mother i know would kick the shit out of their kid for coming home with a cig are you crazy#aint no way you bringing that shit in a black household

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

Increase in Overdose Deaths Among Black Americans Amid National Decline

Decrease in Overdose Deaths Amid Ongoing Racial Disparities Recent federal data indicates a significant decline in overdose deaths across the nation, with a reduction of more than 12 percent reported between May 2023 and May 2024. This noteworthy development marks a crucial step in the United States’ ongoing battle against the devastating impacts of fentanyl. The White House announced that this…

#addiction treatment#Black Americans#drug policy#fentanyl crisis#Georgetown University analysis#naloxone access#overdose deaths#public health strategies#racial disparities#white Americans

0 notes

Link

**Why Black Women Face DEADLIER Breast Cancer Odds**: Delve into the staggering world of breast cancer disparities, where black women face a 40% higher morta...

#black women#breast cancer#health disparities#mortality rate#economic factors#healthcare access#missed treatment opportunities#equal access to healthcare#cancer awareness#social determinants of health#systemic racism#racial health inequities#black lives matter#cancer screening#treatment barriers#cultural biases#patient navigation#survivor support#breast cancer mortality#african american women#cancer disparities

1 note

·

View note

Text

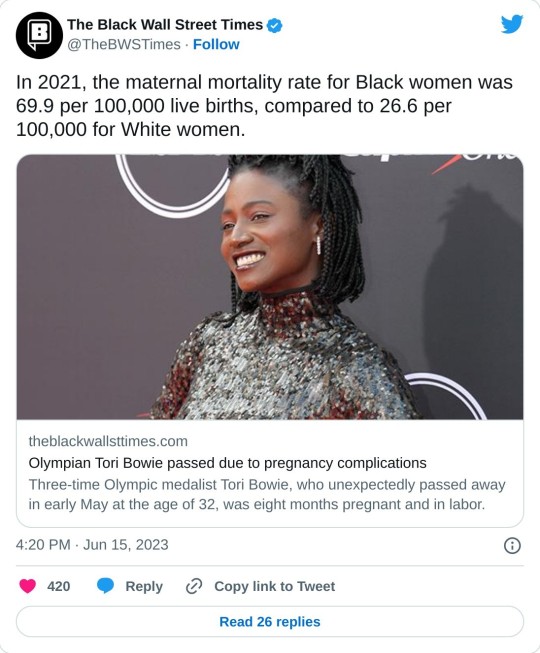

#Tori Bowie#Black Mothers Maternal Crisis#Black Mothers#Black Pregnancy#Health disparities#Black Health Matters#Black Lives Matter#Black Babies Matter#Protect Black Women

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

#police restraint#sedation#Excited Delirium#police brutality#use of force#Ketamine#medical ethics#racial bias#human rights#law enforcement#accountability#lethal implications#community safety#systemic racism#public health#civil liberties#police accountability#medical malpractice#excessive force#civil rights#public safety#criminal justice reform#racial profiling#healthcare disparities#emergency response#use of sedatives#Black Lives Matter#health equity#social justice

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black women face a maternal health crisis. Advocates want to make that a US election issue.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Studies Reveal: All Parents Face Toxic Stress, Racism Exacerbates the Burden for Black Parents

Recent studies highlighted by the U.S. Surgeon General and the American Psychological Association (APA) show that while parental stress is a widespread issue, “41 percent of parents say that most days they are so stressed they cannot function and 48 percent say that most days their stress is completely overwhelming compared to other adults.” The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Mental…

#African American parent magazine#African American parenting#African American parenting magazine#African American parents#Black children education#black parent magazine#black parenting#Black parenting magazine#black parents#community resilience#coping with parental stress#family support networks#Mental Health Disparities#overcoming racial bias#racism and mental health#stress in Black families#successful black parenting#successful black parenting magazine#systemic inequality

0 notes

Text

TIME: Racism Is Not a Mental Illness—But It's Complicated | Time

Everyone knows that Law & Order plotlines are often, as they say, ripped from the headlines.

But Dr. Alvin Poussaint, 88, knows this on another level: An emeritus professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, he has had the unusual experience of seeing his ideas incorporated into a season 12 episode of the long-running show. In it, a white working stiff murders a Black CEO in a dispute over a New York City taxicab. When the trial begins, a respected Black psychiatrist takes the stand to present his idea that the defendant suffers from “extreme racism,” a mental illness. His lawyers argue that extreme racism has such a complete hold on the defendant that it mitigates their client’s legal responsibility for the murder. In the final moments, the audience is encouraged to feel that it’s a victory for justice, for law and order, when the jury rejects the psychiatrist’s ideas, Poussaint tells me with a tinge of disdain.

In the real world, Poussaint was that psychiatrist. Sort of.

While he never brought his ideas to the witness stand inside the New York City courthouse behind those massive stone steps that Law & Order made famous, in 1999 he shared his theories on the link between mental health and extreme forms of bigotry on the op-ed pages of the New York Times. In doing so, he helped set off a debate that ended with the American psychiatric establishment publicly rejecting the concept—partly on the grounds that so many people are racists.

But even now, after nearly a decade during which the number of hate crimes has steadily increased, the question of the relationship between bigotry and mental illness has never fully been resolved. In fact, recent high-profile incidents have made public perception of that dynamic perhaps as muddled as ever. The issue comes up in relation to everything from major mass shootings to pop-culture discourse. The racist attack at a Buffalo, N.Y., supermarket, for which the gunman pleaded guilty this week to state murder and domestic terrorism charges, prompted calls for the country to “get serious about mental health” as well as pleas not to talk about the shooting as a matter of psychiatric illness rather than a racist hate crime.

Read more: Anti-Black Violence Has Long Been the Most Common American Hate Crime—And We Still Don’t Know the Full Extent

A memorial outside the Tops Friendly Market after a mass shooting in Buffalo, N.Y., is seen July 14, 2022.

Joshua Bessex—AP

Though the FBI typically releases data each fall detailing the prior year’s hate-crimes statistics, the agency has not yet done so in 2022. But social conditions are rife, experts say, for the increase to continue. (In 2020, the most recent year for which FBI data is available, the agency reported 8,263 incidents—an increase of nearly a thousand over the prior year, despite 452 fewer agencies reporting—and most experts believe the real number is higher.) Police have noted that 47 out of 100 people arrested for hate crimes in New York City in early 2022 “have prior documentation of an [emotionally disturbed person] incident.” So the stakes are high for the nation’s courtrooms to respond to the trauma unleashed by that dynamic—and for Americans to decide what constitutes a just outcome.

“It’s complicated,” says Sander Gilman, a historian at Emory University who researches the relationship between health, science, law, and society, and who has long taught a course on extremism. “But I’m going to start with two things that I call Gilman’s Law: not all racists are crazy, but crazy people can be racists.”

Thanks in part to the influence of pop culture—not least those TV police procedurals—many assume that insanity pleas are common. In reality, mental-health defenses are rare, and even more rarely lead to reduced punishment. Mounting that kind of defense requires time and significant resources to gather evidence and expert testimony, so in practice it is not an avenue available to all defendants.

In England and the U.S., courts began to reliably consider the mental health of defendants only in the 19th century. The M’Naghten rule, a standard for determining a defendant’s sanity at the time of a crime, was established in 1840s England. It holds that only the sane can be held responsible for their actions. As a result, the question of mental fitness—sufficient sanity to participate meaningfully in one’s own defense—is sometimes evaluated before a trial. (Whether the state has an obligation or right to treat such an illness in order for the person to then stand trial is, Gilman says, a question that goes back as far as the idea of such a defense.) Once a competency decision has been made, the accused who do go to trial have the right to a defense. In some cases, that may include an option for a jury to find the defendant not guilty by reason of mental disorder. In others, ideas about the mental health of the defendant may more informally shape what evidence is presented.

But so-called “mental disease or defect” defenses are used in only about 1% of cases, says Michael Boucai, a professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo School of Law and an expert on mental health and other social issues in courtrooms. Those defenses are successful in even fewer cases; in fact, such a tactic often backfires or results in a defendant confined for a longer term inside a hospital than that person would have spent in prison, sometimes with no end date. And even rarer—though not unheard of—is an attempt to use racism or other bigotry as an indicator of mental-health challenges, he says.

A crowd prays outside the Emanuel AME Church after a memorial service for the nine people killed in a racist attack at the church in Charleston, S.C., June 19, 2015.

Stephen B. Morton—AP

Some fear that raising mental-health issues in court runs the risk of bolstering inaccurate myths about the mentally ill. In reality, mentally ill people are disproportionately more likely to become the victims of crime, and most do nothing to victimize others. And, as has been observed after so many headlinemaking crimes, suspects from privileged groups are more likely to have their actions described as illness in need of treatment instead of criminal evil meriting punishment. Some experts fear that shifting the conversation to questions of mental health can also draw attention away from hateful ideas embraced by the person accused of the crime—ideas that are today often shared by people, including public figures, whose mental health is not questioned. That’s how important social problems that require the nation’s attention are transformed into one individual’s medical problems, says W. Carson Byrd, a sociologist at the University of Michigan.

Column: We Need to Take Action to Address the Mental Health Crisis in This Pandemic

That line of thinking is particularly problematic in a culture prone to dismiss the need for systemwide reforms to address inequality, Byrd says. It can foster an emphasis on quick fixes for the world’s long-standing problems with bigotry. (In 2012, for example, a team of British researchers announced that an existing heart and blood-pressure drug appeared to reduce implicit bias after a study involving just 36 subjects.)

“White supremacy is a very normal part of society,” says Byrd, who is also the faculty director of research initiatives at his university’s National Center for Institutional Diversity. It is not a good or productive part of society, he points out, but a deeply entrenched one. “One of the detriments of trying to look at racism as a form of psychopathology or mental illness is that it makes that [illness] abhorrent, as if everything else is working in a certain [non-racist] way.”

Research has also long shown that bigotry is not an inborn human trait, but rather something learned from our environments, Byrd says. While racism can influence one’s mental health, describing racism itself—even “extreme racism”—as a mental illness implies that bigotry exists beyond our individual and collective control.

“By medicalizing [extreme racism], making it something curable, a mental-health disorder, it pulls away from having those broader conversations about how society is impacting people,” he says. “We just try to figure out, ‘How do we fix this one person?’”

This problem, Boucai notes, can already be clearly seen in discussions about gun crime, and mass shootings in particular: “It’s very hard to understand these crimes and the discourse of insanity provides one way to do it,” says Boucai. “But I think we can see where that sort of language is irresponsible and potentially undermines a just result.”

In other words, if a mass shooter is simply insane, then wholesale gun-law reform can, to some, seem unnecessary, even unwise. When bigotry is involved, that supposed insanity might, some who oppose Poussaint’s ideas believe, undermine systemwide efforts toward equity—or at least toward greater safety for those most likely to be targeted.

In 1999, when Poussaint wrote his op-ed advocating for increased research into possible psychiatric treatments for extreme racism, he was the author of acclaimed books about the effects of racism on Black mental health and a veteran of public controversy. Years earlier he’d argued publicly that racial pride among Black Americans could be taken to an unhealthy extreme. By the 1990s, he may have been best known for his work with Bill Cosby, consulting on scripts for The Cosby Show in a massively popular effort to disrupt stereotypes.

Poussaint first published his ideas about extreme racism weeks after a man named Buford O. Furrow Jr. shot and seriously injured four children and an adult inside a Jewish Community Center in Los Angeles, then shot and killed a nearby Asian-American postal worker. When captured and ultimately convicted, Furrow told investigators his actions had been motivated by hate. Reporters unearthed information indicating that Furrow had close relationships with known white nationalists, and also that he had been evaluated by Washington State’s mental-health system only months before the attack. He’d even told officials after a previous arrest for assault that he’d “fantasized,” about mass murder. To Poussaint, this story signaled a growing threat posed by a failure to recognize that, while highlighting and combating systemic racism is important in preventing discrimination, so is identifying and helping individuals motivated by bigotry who might go so far as to injure or kill others.

Read more: 11 People Were Killed in 48 Hours in Mass Shootings Across America. It’s Likely to Get Worse

Train passengers are treated on the platform after Colin Ferguson opened fire on the train as it arrived at Garden City, N.Y., on December 7, 1993.

Alan Raia—Newsday RM/Getty Images

“Extreme racism crosses the line and is out of control,” he explains. “Just like somebody can have a little bit of anxiety, but if they have anxiety to the point that it is immobilizing, then it is a mental disorder.” Mass shooters behind hate crimes are, as he sees it, in a similar state: “[They] weren’t functioning individuals. They were impaired by their mental pathology.”

When the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the guide that mental-health professionals use to make their diagnoses, was published in 1980, clinicians like Poussaint considered racism—not extreme racism, but what he calls everyday racism—a potential symptom of several conditions, from paranoid personality disorder to generalized anxiety disorder. Racism alone is not sufficient to diagnose a patient with one of those conditions, but an extreme racist, Poussaint says, likely suffers from delusions. Such people live with multiple symptoms including paranoia; they are likely to project negative traits or outcomes onto entire groups and sustain those beliefs even in the face of strong countervailing evidence. Many embrace conspiracy theories. Some may grow violent. In fact, Poussaint argued in a 2002 Western Journal of Medicine article, the extreme racist often begins with “verbal expression of antagonism, progresses to avoidance of members of disliked groups, then to active discrimination against them, to physical attack, and finally to extermination (lynchings, massacres, genocide). That fifth point on the scale, the acting out of extermination fantasies, is readily classifiable as delusional behavior.”

Poussaint was not the first person to raise the idea that extreme racism is itself a mental illness. But he was among those leading the call for the American Psychiatric Association, publishers of the DSM, to consider putting it in subsequent editions of the manual, which has a long history of evolving, often slowly, in response to research and norms. When his op-ed ran, it seemed to Poussaint, people pounced.

Some of his fellow Black psychiatrists argued that such a diagnosis would unleash a wave of legal excuse-making, helping no one but the violent racists themselves. Poussaint counters that other health diagnoses have yet—nearly 200 years after psychological concerns officially entered American courtrooms—to produce rafts of acquittals. And some clinicians and researchers argued that there are other ways of attacking racism besides treating it as an illness—educational programs, diversity initiatives, policy changes. That’s a point Poussaint says he doesn’t oppose, at least when it comes to everyday racism. Those steps can help racists who embrace repugnant ideas while remaining functional parts of society. But those aren’t the people he’s talking about.

“Racism negatively impacts public health,” the American Psychiatric Association told TIME in a statement. “The American Psychiatric Association has been focusing on this in the DSM by identifying and addressing the impact of structural racism on the over- or underdiagnosis of mental disorders in certain ethno-racial groups. From time to time we have received proposals to create a diagnosis of extreme racism but they have not met the criteria identified for creating new disorders.”

To this day, Poussaint believes that extreme racism is very likely its own disorder in need of study, possible diagnostic criteria, and evidence-based treatment, he told me in September from his home in Massachusetts. But after retiring about 2½ years ago at the age of 86, he says he’s too far out of the professional mix to continue to push for an extreme racism diagnosis.

I ask Poussaint what he thinks might have happened if extreme racism had become its own diagnosable condition listed in the DSM. Extreme racism might have been a topic on talk shows and a more frequent topic of news coverage, he says. With research and public information campaigns, the need for intervention could have been as clear as it is for heart attacks; the steps to do so as well-known as CPR.

“We’d get away from treating it as if [extreme racism] is normative,” Poussaint says, “like a cultural difference because America is a racist country. We have made it normative by not calling it what it is. Even people in general society, friends and relatives and even the afflicted individual, would recognize it as a disorder and say, ‘I’m not alright.’ People who get swept up by anxiety and can’t function, they don’t think they are normal. They say, ‘This is taking over my life. I need some help.’ [A diagnosis] clues the family to say, ‘This person is really troubled and we have to get them some help.’”

#Racism Is Not a Mental Illness—But It's Complicated#Mental Health in America#mental health disparities#mental health neglect#racism is as american as rotten apples#Black Lives Matter#Systemic Racism#racial disparities in america

12 notes

·

View notes