#Black Detroit History

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

14 Lesser-Known African American Historical Sites in Detroit | Visit Detroit

1.4 miles. That is the short distance that stood between many 19th century Black Americans and freedom in Canada.

For many runaway slaves, the shores of the Detroit River would be their last glimpse of life in the country that enslaved them.

Detroit’s history as a stop on the Underground Railroad is only one aspect of our city’s invaluable Black history.

Some of Detroit’s historical landmarks are well-known. Places like the Charles H. Wright Museum, and Second Baptist Church are not to be missed on any visit to our city. But, for those who would like an even deeper dive in Detroit’s Black history. Here’s a list of some of our faves.

Be sure to scroll to the bottom to see all of these sites mapped out for easy itinerary planning.

1.The Offices of the Detroit Plaindealer

1114 Washington Blvd., Detroit, MI 48226

An independent African American newspaper, The Detroit Plaindealer, published its first issue in May of 1863. It closed up shop somewhere around 1895.

Published by brothers Benjamin and Robert Pelham Jr. - alongside Walter H. Stowers and W.H. Anderson - The Plaindealer was the African American voice. “That was our voice,” explained Kimberly Simmons, chair of the Detroit Historical Society’s Black Sites Committee and president of the Detroit River Project, to The Huffington Post. “You had a whole group of people here, and the only way they knew what was going on was the Plaindealer. So it was a huge deal.”

The newspaper’s office was located on the southwest corner of Shelby and State Street. That space is currently occupied by the Westin Book Cadillac Hotel. A marker was recently erected to denote the historical relevance.

2. The Alger Theater

16451 E. Warren Ave., Detroit, MI 48224

While it has largely been white-owned, The Alger Theater served what evolved into the diverse historic neighborhood of Morningside located on the near-Eastside of the city.

One of only two remaining intact and unchanged neighborhood theaters, the Alger Theater was granted historic designation in 2009. The designation saved the theater from demolition.

Historically, it was a movie house that eventually showed B-movies in the late-70s and early 80s. However, earlier in its life, popular jazz acts like Dave Brubeck and the Duke Ellington Orchestra played in the 800-plus seat theater.

The Friends of the Alger Theater is a 25-year-old active non-profit organization committed to making the historic theater an anchor of this evolving neighborhood.

3. The Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity House

293 Eliot St., Detroit, MI 48201

The home of Gamma Lambda Chapter, the 100-year-old Alpha House near downtown Detroit is home to the third oldest alumni chapter in the history of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc.

The building was built in 1919 and the fraternity purchased it in 1939. It is currently the meeting location, a museum, and event space for the organization.

Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. is the oldest Black Greek Letter Organization in history. It was founded in 1906.

4. Elmwood Cemetery

1200 Elmwood St., Detroit, MI 48207

One of the first fully-integrated cemeteries in the Midwest, Elmwood Cemetery is the resting place for a number of iconic Black Detroiters.

Former mayor, Coleman A. Young; Fannie Richards, Detroit’s first African American school teacher in the public school system; and Dudley Randall, Detroit’s former Poet Laureate, are all resting in this historic location.

Elmwood Cemetery and the Historic Elmwood Foundation launched a self-guided African American History Tour in 2015.

5. Algiers Motel Location

8301 Woodward Ave., Detroit, MI 48202

Three people were killed throughout the night of July 25-26, 1967, at the Algiers Motel in an incident during one of the darkest times in Detroit history. A period that the city has still not truly healed from.

As the 1967 rebellion raged in Detroit, several Black male youths and white women were listening to music inside the motel. One youth fired a starter pistol into the air which drew the attention of nearby officers believing they were dealing with many armed rioters.

The resulting police clash and deaths and wounding of seven others enraged the already tense community. The legacy of the Algiers Motel has been preserved in stage plays and films including the 2017 movie, Detroit.

6. The Shrine of the Black Madonna

7625 Linwood St., Detroit, MI 48206

Founded in 1967 by Albert B. Cleage, The Shrine of the Black Madonna was established as a segment of the Black Christian Nationalist Movement. The church is known for its recognition to center African Americans within the Christian narrative – a narrative that was often rooted in white supremacy.

Since its founding, the congregation at The Shrine of the Black Madonna became a powerhouse in Detroit politics instrumental in the mayoral elections of Coleman A. Young and Kwame M. Kilpatrick.

The Shrine also has a dynamic bookstore that is essential for any visitor to the historic site. The store features new and rare books on Black history and culture.

7. Masjid Wali Muhammad

11529 Linwood St., Detroit, MI 48206

Linwood Street was the site and home of much of the pan-African and Black nationalist movement. One important site is this historic masjid. This location was initially established as Temple #1 of the Black Muslim movement, The Nation of Islam.

The Nation of Islam moved into this space in 1959 and was designated a historic site in 2013.

The location was renamed in the late 70s after the death of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. The name, Masjid Wali Muhammad was chosen in honor of the brother of Elijah Muhammad and designated a “masajid” the Arabic word for the place of worship for Muslims.

8. King Solomon Church

6100 14th St., Detroit, MI 48208

Founded in 1926, King Solomon Baptist Church has been an important center of Black life in Detroit since its founding.

The church was the site of one of the first Boy Scout troops for Black Detroiters. It was also a community center for the neighborhood. Youth outreach programs, like a boxing program led by the legendary Emmanuel Stewart, was where world champion boxer, Thomas “The Hitman” Hearns got his start.

The church was also the home of a number of gospel acts including Reverend James Cleveland and The Supremes. The church, which has 5000-seats, has also been the location of a number of historical Black speeches including two appearances by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

9. Submerge Record Distribution

3000 E. Grand Blvd., Detroit, MI 48202

The world headquarters of Underground Resistance is also home to the Detroit Techno Museum.

Original records from the height of the era, including gold and platinum plaques, are on display inside the museum. It should be noted that it is only available by appointment.

The museum has been called a “mecca for true techno fans” and the music, which reflected the grime of Detroit in the 1980s. John Collins, a DJ and producer told Detroit Metro Times that techno music, which is renowned around the world, was created to give listeners “hope for the future, that things will get better.”

10. Plowshares Theatre Company

440 Burroughs St. #185., Detroit, MI 48202

Founded in 1989, the Plowshares Theatre Company has been offering a true off-Broadway experience as Michigan’s only professional African American theatre company.

The company has dedicated itself to “breaking new ground” by nurturing emerging, talented writers and actors. Named after a blade that cuts the top layer of soil in a farm, the name Plowshares refers back to the work that enslaved people did on plantations.

Producer Gary Anderson wrote that Plowshares is important because when African Americans can see themselves in artistic endeavors, like plays, it is a validation of life.

11. Dr. Ossian Sweet House

2905 Garland St., Detroit, MI 48214

This historic site does appear on a number of must-see lists for visitors to Detroit, but it remains worth mentioning again.

In September of 1925, Dr. Ossian Sweet and his wife Gladys moved into their home on Garland St., and within hours a neighborhood group gathered to run the couple out of the home. A mob of at least 400 people gathered the next night throwing stones at the house.

Someone inside the house fired shots from a second-floor window hitting a rioter who had come onto the porch and wounded another in the crowd. All of the Black people in the house were charged with murder.

Dr. Sweet was acquitted of charges after being represented by the illustrious Charles Darrow. Charges against the rest of the group were dropped. However, Mrs. Sweet contracted tuberculosis in jail and died, along with the couple’s two-year-old daughter. And years later, Sweet took his own life.

The home represents the challenges that African Americans in Detroit had in moving into primarily white neighborhoods. The city is now majority Black.

12. Whipping Post

The Southeast corner of Woodward and Jefferson Avenues

This site was the location of Detroit’s first and only whipping post. The post was used to flog thieves and vagabonds, in protection of the city’s moral codes.

The whipping post was also a location where a man could be sold for a number of days work for petty crimes although slavery was illegal in the state of Michigan.

The legacy of the whipping post is still little-known. However, it is reasonable to assume that Black Detroiters, prior to 1830 when the post was removed, were punished at the post. It is mapped on the Mapping Slavery in Detroit map created by the University of Michigan.

13. Second Baptist Church

441 Monroe St., Detroit, MI 48226

Second Baptist Church is the oldest Black-established church in the Midwest. Founded in 1836, Second Baptist Church was a station on the Underground Railroad. The church was a final stop for some 5,000 enslaved people giving them food and clothing before sending them on to Canada.

14. Elizabeth Denison Forth’s House

328 Macomb, Detroit, MI 48226

Born a slave near Detroit in 1786, Elizabeth (Lisette) Denison Forth won her freedom after she and her brother moved to Canada to establish residency, which guaranteed that they would not be returned to their previous slave owner.

Lisette became a domestic servant, but she invested all of her pay into purchasing land. She became the first Black property owner in Pontiac, Michigan. She invested in the stock market and real estate and ultimately her own home became a Michigan Historic Site.

The front doors of St. James Episcopal Church is dedicated to Lisette who was a devout Episcopalian. She dedicated her life savings of $1,500 in 1866 to the building of the church.

In 2017, she was added to the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame for her dedication to freedom and for equality among the rich and poor.

#14 Lesser-Known African American Historical Sites in Detroit#Detroit#Black HIstory in Detroit#Black Detroit#Black People#Black Lives Matter#Black Detroit History#racism in michigan#elizabeth dennison forth

0 notes

Text

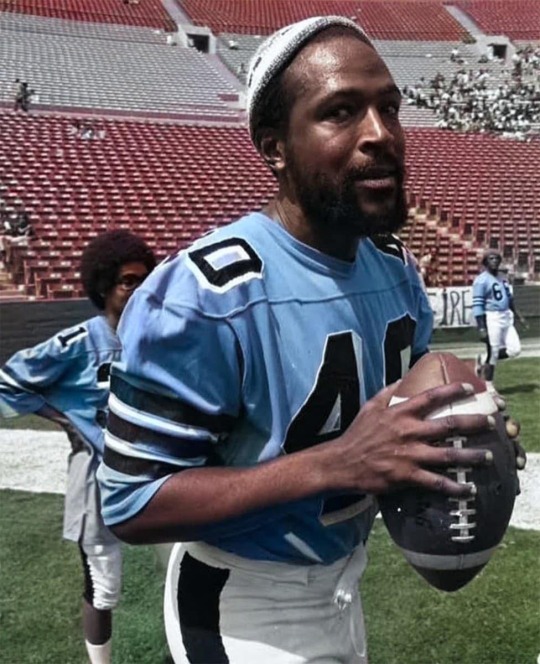

Did you know Marvin Gaye tried out for the Detroit Lions in 1970? Along with music, Marvin Gaye had a passion for sports. His two close friends, Mel Farr and Lem Barney, played for the Lions at the time and were able to set up a meeting between Gaye and the team's head coach, Joe Schmidt. Marvin Gaye confidently told Coach Schmidt that he would score a touchdown the first time he touched the ball, despite having never played on a football team before. He took on a vigorous workout regimen to prepare, and Coach Schmidt let him try out for several positions on the team. Although Marvin Gaye was not offered a spot with the Detroit Lions, he was satisfied by the fact that he was offered an opportunity and gave it his best effort.

#marvin gaye#detroit lions#blacktumblr#black history#black liberation#african history#nodeinoblackbusiness#buy black

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Feral Friday!

This week we’re diving into zine history.

Zines amplify marginalized voices & stories excluded from conventional publishing, challenge authority, and provide egalitarian channels for creative expression and alternative community building.

Though often dated to the sci-fi fanzines of 1930s, some argue that zine history originated in the context of early printing in the 16th century with Martin Luther’s self-published 95 Theses. Given Luther’s use of vernacular, critiques of established ideologies, and use of pamphleteering to spread his message, we tend to agree! Following suit overseas, the cheaply produced broadsides of the 18th century American Revolution were quickly disseminated to influence public opinion.

In the 1920s artists in Europe produced radical journals and periodicals which spread the ideas of Surrealist and Dada movements and critique of bourgeoise culture. In the 30s sci-fi fanzines provided platforms for fan content and dialogue. The Beat poets produced low-cost mimeographed chapbooks and broadsides in the 40s & 50s, challenging the censorial nature of American society with writing on civil rights, the anti-war movement, environmentalism, and free love.

During the same period the Soviet Union DIY (aka Samizdat) movement, in which Eastern Bloc activists reproduced and distributed state censored publications by hand (often on typewriters), emerged. Xerography became popularly available in the 60s and low-cost offset printing and the electric typewriter were introduced, spurring the rise of underground comix & alternative newspapers.

Punk zines appeared in the 70s, followed by the DIY movement and the indie music scene. In the 80s copy machines became ubiquitous, and in the 90s the Riot Grrrl underground punk movement and rise of third wave feminism produced a slew of new publications.

Because forms of zine production have proliferated in various contexts throughout printing history, even a Western-centric overview was hard to capture succinctly. Stay tuned for more in future posts!

Images:

Dada germanico. Gabriele Mazzota editore, Milan, 1970. Facsimile edition of 1920 original.

Dada germanico.

from Disputatio D. Martini Luther theologi, pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum, a bound edition of Martin Luther's 95 Theses. Adam Petri, Basel, 1517.

How industrial unionism was won : the great Flint sit-down strike against General Motors, 1936-1937. Progressive Labor Party, Brooklyn, NY.

Prose contribution to Cuban revolution. Allen Ginsberg. Artists' Workshop Press, Detroit, 1966.

Russian samizdat and photo negatives of unofficial literature in the USSR. Moscow. Wikimedia Commons.

The Bunch's power pak comics. Aline Kominsky-Crumb. Kitchen Sink Enterprises, Princeton, WI, 1979.

Plunger. Alison. Team Plunge, New York, NY. Dec. 1994.

FAT! SO?. Marilyn Wann. San Francisco, CA. no.4 1995.

Angry black-white girl : reflections on my mixed race identity. Nia Diaspora. Publication year unknown (between 2000-2009).

View more Feral Friday posts.

View more posts with zines.

--Ana, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#feral friday#zines#history of zines#labor rights#dada#martin luther#95 theses#riot grrrl#samizdat#underground comix#Aline Kominsky-Crumb#Allen Ginsberg#Nia Diaspora#Nia King#Detroit Artist Workshop Press#dada germanico#feral#feral fridays#Ana#Detroit Artists Workshop#zine culture#Kitchen Sink Press#Marilyn Wann#Plunger#beat generation#Angry Black-White Girl#Power Pak Comics

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Zoot Suit in Black Culture

In today's history lesson, we will discuss the vintage zoot suit, a men's suit with high-waisted, wide-legged, tight-cuffed, pegged trousers, and a long coat with wide lapels and wide padded shoulders.

The Chitlin Circuit (during the era of US racial segregation) was a network of clubs, theaters, and other venues where Black entertainers were allowed to perform, as defined by the Oxford Dictionary. These hotspots had comedy shows where entertainers such as Pigmeat Markham would dress up in baggy suits as part of their routine. This took place in the 1920s, eventually giving way to the more flamboyant, stylish and colorful zoot suit.

Born out of the inner city ghettos and African-American creativity, the suits were first associated with cities such as Harlem, Detroit and Chicago in the 30's. Musicians helped popularize the suit with a more tailored distinguished look, Cab Calloway, an American entertainer, famously wore the zoot suit in the movie, Stormy Weather (1943). Jazz and Jump Blues were all the rage back then and you could spot these suits at the dance halls.

“The zoot was not a costume or uniform from the world of entertainment. It came right off the street and out of the ghetto.” -Harold C. Fox, a Chicago clothier

According to Cab Calloway's Cat-ologue: A "Hepster's" Dictionary (1938), he called the zoot suit "the ultimate in clothes. The only totally and truly American civilian suit."

It was the signature look of the African-American subculture of Hepcats. A young Malcolm X could be seen wearing one. Dancers to businessmen to singers to instrumentalists, all dressed in zoots. It wasn't just about making a fashion statement, but a sense of cultural pride.

The look picked up in other communities such as the Mexicans, Filipinos, Japanese etc... forming their subcultures respectively.

On June 3, 1943, a string of attacks against Mexican-Americans started in Downtown Los Angeles, CA. Approximately 11 sailors got into a heated confrontation with some young Mexican-Americans and proceeded to assault them. The next day, hundreds of sailors traveled to a predominantly Mexican-American settlement in East Los Angeles and began another assault. Harassing anyone who wore a zoot suit, making them strip and burning their clothes. White residents and servicemen used the excuse that the zoots weren't "patriotic" due to it containing large amounts of fabric. This is during World War II were rationing food and fabrics were seen as necessary. This vicious and violent behavior spread to different cities leaving nothing, but devastation and trauma in its wake. These were known as the infamous Zoot Suit Riots of 1943.

Source 1 Source 2 Source 3 Source 4

#zoot suit#black history#black tumblr#black art#black women#theafroamericaine#black fashion#black hair#black culture#black girls of tumblr#nostalgia#Culture#african american#african history#vintage photography#cab calloway#art style#style#Mexican#history#writers on tumblr#writing#Detroit#america#north america#american history#california#black men#black community#melanin

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in Hip Hop History:

Black Milk released his fifth studio album No Poison No Paradise October 15, 2013

#today in hip hop history#todayinhiphophistory#hiphop#hip-hop#hip hop#music#history#hip hop music#hip hop history#rap#black milk#hip hop culture#music history#no poison no paradise#album#emcee#mc#rapper#producer#music producer#detroit#2013

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

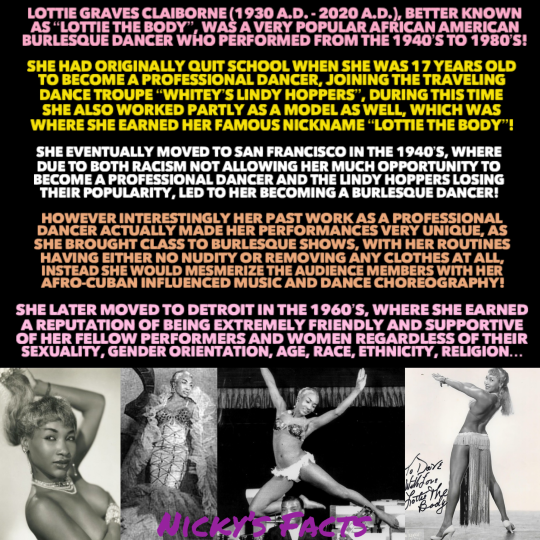

Lottie the Body brought class and acceptance to burlesque shows!

💃🏾

#history#lottie the body#burlesque#dancer#lottie graves claiborne#american history#detroit#black queen#burlesque performer#historical figures#black coquette#black history#black history month#role model#african american women#united states#girl power#black beauty#african american history#sisterhood#women supporting women#black tumblr#womens history#black girl magic#black excellence#soft black girl#women empowerment#nickys facts

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detroit: One Nation Under A Groove

youtube

👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾❣️❣️

#detroit#music#black dancers#black positivity#black magic#black power#black history#black people#black community#Youtube

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Halloween window display at B.F. Goodrich Company, Detroit, Michigan, date unknown.

#halloween#detroit#michigan#history#black and white#b.f. goodrich#ghost#pumpkin#graveyard#window display#midcentury#midcentury modern

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

↠ bitch, i never give pussy, but i’m always serving cunt ; drunk freestyle, monaleo

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thornton and Lucie Blackburn in Canaan, Mario Moore, 2022

Oil on linen 63 x 90 in. (160.02 x 228.6 cm)

#art#painting#mario moore#contemporary art#black artists#21st century#2020s#oil#american#african american#black history#detroit#michigan

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

~posting this in every fandom im in dont mind me im a lil desperate💅~

im doing my bachelor's thesis on fans and fandom spaces!!!! & i need responses:') details in the forms description!

pls dont forget to hit submit at the end!!

#the secret history#all for the game#our life beginnings & always#error143#queer as folk#detroit become human#dead poets society#haunting of bly manor#orange is the new black

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday to the Detroit's finest late great J Dilla aka Jay Dee

#n.e.w.s. brand#n.e.w.s.#n.e.w.s#news brand 88#n.e.w.s.brand#steer your destiny#detroit#the D#Michigan#J Dilla#Jay Dee#88#2025#winter#winter '25#music#producer#hip hop#rap#rapper#midwest#legend#legendary#black history#black history month

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

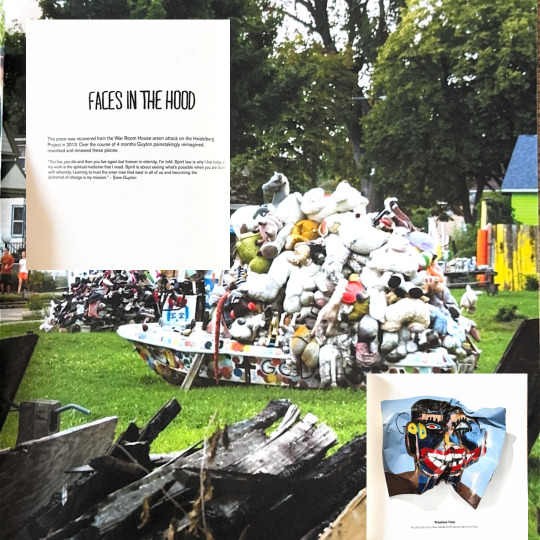

Archive Description:

Heidelberg Project:

The Heidelberg Project is an outdoor art environment/art installation by artist Tyree Guyton on Heidelberg street, on Detroit's east side. Guyton started the project as a response to the deterioration of his own neighborhood, as wells many other Detroit neighborhoods after years of decline. Through the project, Guyton hoped to raise awareness of the decay of inner-city neighborhoods and the effects of urban sprawl.

Guyton grew up on the Heidelberg Street and returned on 1986, starting the project by cleaning up vacant lots with his grandfather. Using discarded items they collected, and with the help of neighborhood children, Guyton and his grandfather transformed abandoned houses and vacant lots into massive pieces of art. Guyton also integrated the street, sidewalks, and trees into an enormous work of art, officially calling it the "Heidelberg Project". The project initially received unfavorable critical reviews and the City of Detroit ordered him to remove his installations. Guyton persevered and has since received many award for his efforts. Throughout the years, Guyton continued to update and expand the Project, which eventually grew to encompass two city blocks. Sone disliked the attention drawn to their neighborhood, while others simply thought of the project's installations and junk.

In November 1991 Mayor Coleman Young, gave an order to demolish three of the project's houses, the Baby Boy House, Fun House and Truck Stop. Eight years later, in 1999, Mayor Dennis Archer also ordered three more houses to be demolished, Your World, Happy Feet, and Canfield House. Unfortunately, a series of unresolved arson fires between 2003 and 2015 destroyed 12 of his artistic houses on Heidelberg Street. Only two of the original project houses remain, the Dotty-Wottyhouse and the Numbers House.

Sources: The Detroit Historical Society, Three Guyton Spirit Inner State Gallery Publication.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

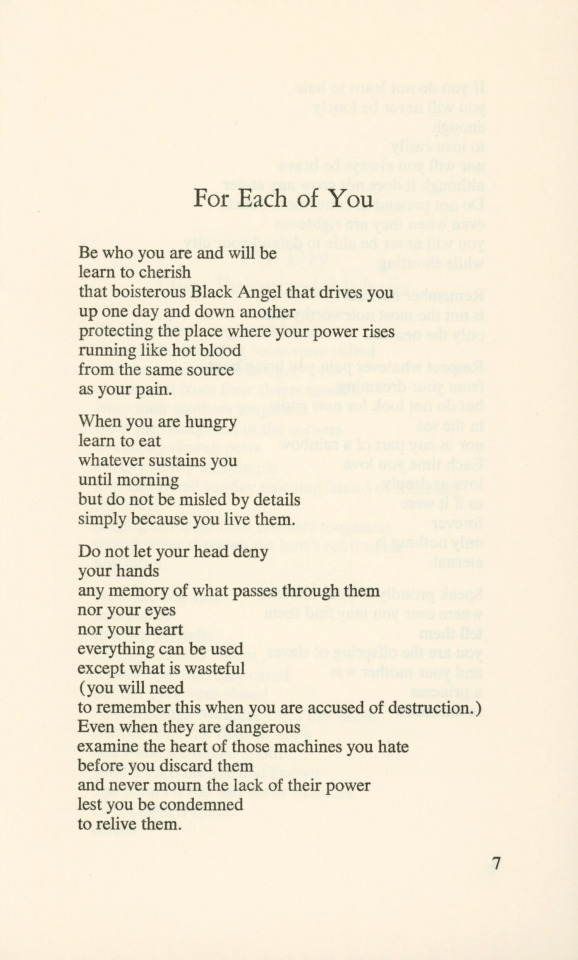

International Women's Day

In celebration of Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day (March 8), we’re showcasing one of writer, educator, intersectional feminist, poet, civil rights activist, and former New York public school librarian Audre Lorde’s (1934–1992) early collections of poetry. From a Land Where Other People Live was published in 1973 by Detroit’s groundbreaking Broadside Press. This independent press was founded in 1965 by poet, University of Detroit librarian, and Detroit’s first poet laureate Dudley Randall (1914-2000) with the mission to publish the leading African American poetry of the time in a well-designed format that was also "accessible to the widest possible audience." A comprehensive catalog of Broadside Press’s impressive roster of artists (including Gwendolyn Brooks, Nikki Giovanni, and Alice Walker, to name a few), titled Broadside Authors and Artists: An Illustrated Biographical Directory, was published in 1974 by educator and fellow University of Detroit librarian Leaonead Pack Drain-Bailey (1906-1983).

Lorde described herself in an interview with Callaloo Literary Journal in 1990 as “a Black, Lesbian, Feminist, warrior, poet, mother doing [her] work”. She dedicated her life to “confronting and addressing injustices of racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia.” From a Land Where Other People Live is a powerfully intimate expression of her personal struggles with identity and her deeply rooted critiques of social injustice. The work was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry in 1974, the same year that Broadside Press published New York Head Shop and Museum, another volume of Lorde’s poetry featured in our collection. You can find more information on her writings and on the organization inspired by her life and work by visiting The Audre Lorde Project.

More posts on Broadside Press publications

More Women’s History Month posts

More International Women’s Day posts

-- Ana, Special Collections Graduate Fieldworker

#Women’s History Month#International Women’s Day#Audre Lorde#Broadside Press#Dudley Randall#Detroit#Poetry#From a Land Where Other People Live#Independent presses#Feminist writers#Lesbian writers#Black writers#women writers#women poets#Ana

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detroit, Michigan. Back view of a Negro dressed in a zoot suit, walking in the business district (1942)

#black tumblr#black art#theafroamericaine#black fashion#black hair#black history#black culture#black girls of tumblr#nostalgia#history#vintage photography#photography#vintage#1940s#american history#Detroit#black men#black community#melanin#melanated#michigan

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in Hip Hop History:

Black Milk and Danny Brown released the album Black and Brown! November 1, 2011

#today in hip hop history#todayinhiphophistory#hiphop#hip-hop#hip hop#music#history#hip hop music#rap#hip hop history#hip hop culture#music history#black milk#danny brown#black and brown!#black and brown#2011#album#detroit#emcee#mc#rapper#producer#music producer

26 notes

·

View notes