#Because you have intrinsic value as a human being just by virtue of existing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

hey bex! i haven’t been using tumblr a lot lately but i am having a little thing that’s bothering me and idk who to talk to. i hope this doesn’t sound stupid but i am (very sure) i am asexual. i do not really want to do anything with another person. but sometimes i feel like a have a month or something that i feel like i am in heat. and feel the need to do something about it myself. which i know is a normal thing to do that yourself but sometimes i even feel bad about doing that. i’m very just lost and i feel like if i do that then i’m fake when i call myself asexual. (also i am a 25 year old female if you were wondering about who sent this)

(also reminder that i think you are very swell and i love this blog and i need to catch up on anything you have written while i haven’t been on this app.)

- 🥶

Well, hey there Ice. Glad you came to me here with this, I love being able to provide support and care when I can. Now, having those wants and urges is totally natural and you wanting to get down with yourself is perfectly fine. It does not make you a fake asexual because it is all a spectrum but also, asexuality is a lack of sexual attraction to people, that is what defines it, not libido. There are ace people in relationships, ace people who have sex and enjoy it and masturbation, ace people who read smut, engage in kink and get genuine pleasure and enjoyment out of it, and this doesn't mean they are any less ace.

I consider myself heavily aromantic in many respects, but I'm married, in a committed, long term, almost eleven year romantic relationship with my husband, doesn't mean I am still not aromantic because I have an exception in my husband.

Just remind yourself that you are allowed to do what you want with your own body, you are allowed to enjoy it to the fullest, you have permission to explore and feel good and experience pleasure. And also, keep in mind, our titles, sexualities, romantic orientations, they are meant to be helpful, not harmful and also, not rigid. We change, we expand, we grow throughout our life times, we gain and shed labels all the time and there is nothing wrong with that. It doesn't mean that you weren't what you said you were at that point, it could very well have been true at one point, and you grow past it at another.

This is totally cornball, but I love it, the moon has phases, and we still think it is valid and respect the moon, why can't you, a living, growing, changing person, also be respected during all your different phases?

Be kind and be gentle to yourself, please. Remember, more often than not we are our own harshest critics.

#For real tho Ice go get you some whenever you want#Don't feel bad for indulging in the natural and very human act of self pleasure#Seriously it is a bad path to go down#You earned it#You deserve it#Why?#Because you have intrinsic value as a human being just by virtue of existing#Hope this helps#BHF asks#BHF advice

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

i feel like seeing the world through actions rather than character seems like you're subconsciously distant and dissociated from yourself; as though some deep-seated insecurity or anxiety about an inherent personality trait means that you place value specifically on behavior and not personality.

for example, is a person artistic simply because they make art, or are they compelled to make art because they have this specific inexplicable draw and desire to do so? would someone who was not innately kind or interested in being kind "do" kind things?

which innate trait were you born with that drives you to assume that different opinions must stem from a psychological issue?

anyway, no, i am not innately artistic. nobody (or everybody, which is essentially the same thing) is. i bothers me that we treat art as so much more sacred than other human activities. would you say the same about someone whos hobby is collecting funko pops? are they driven by an inexplicable desire to collect shit figurines?

making art is something i know how to do. its a skill ive acquired, like cooking or driving a car. to attribute it to an innate talent would be to erase the years of study and practice ive put in. if its more initially rewarding because i have any natural advantage, it might be that i have pretty good fine motor skills, but thats a neutral physical trait like my height or weight, which i dont glean any meaningful identity from either. but maybe that initial aptitude led to more satisfaction, encouragement etc which has naturally caused me to think about art more than someone who did not start with that immediate small advantage.

ive had the privilege of teaching hobby painting classes to people who are not skilled and would not consider themselves "artistic," and everybodys reactions when they learn a new technique and make something they thought they couldnt is proof to me that art making is rewarding to *everybody,* not just a special class of divinely ordained creatives. i fundamentally do not believe that i am unique for finding art fulfilling. it feels good to make stuff. thats just human.

as far as kindness goes, if there are intrinsically kind people, it would follow that there are intrinsically unkind people, right? people who are born without kindness as an innate trait... so then what would be the point of trying to rehabilitate people whove committed violent crimes? if they dont have that inherent drive for kindness that innately kind people do, then it would be hopeless, right?

if we can neatly divide people into categorically kind and categorically unkind people i guess it would be much easier for us kind people (im at least flattered that you assume id be on that side of the dichotomy) to like, just be confident that we are morally in the right and not ever have to question the actual impact of our behavior since our intentions are good by virtue of this innate trait we were born with. sure whatever.

assigning importance to intentions and feelings rather than actions and their impact is like very yuckydisgusting to me. like i said in my reblog right before this, if kind thoughts were enough to make someone a kind person, then negative thoughts would be enough to make someone a bad person. silly and obviously wrong. i've fantasized about all kinds of destructive actions, but it literally does not matter at all, the only important thing is my choice not to act on those fantasies.

wanting or trying to be a kind person does not make someone a kind person. some of the nastiest motherfuckers ive ever met were constantly agonizing over whether they were a good person and looking for reassurance that they hadnt done wrong. yet they continued to act selfishly and harm people around them. their desire to be kind did jack shit.

but yeah, i do place value specifically on behavior because thats the only part of personality that meaningfully exists to literally anybody outside of your brain. basically. i think thats the main point of all of this.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

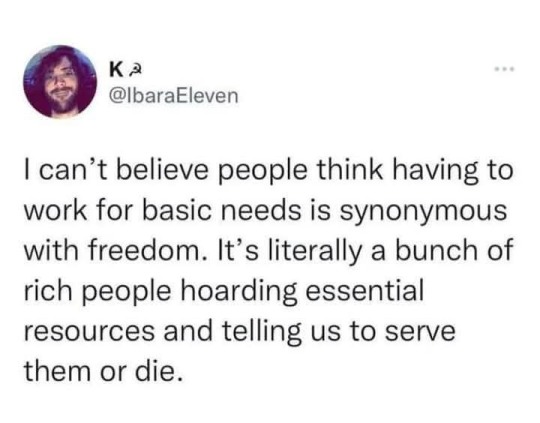

Protestant Work Ethic.

Culturally, Americans have been brought up to believe that the act of labor is in and of itself a moral virtue. That work is not a means to the end of achieving a material outcome or the end of acquiring compensation, but a means to the end of demonstrating intrinsic virtue and earning your place in Heaven.

The Protestant Work Ethic is very convenient for capitalists, and so business eagerly propagates it. How many times have you heard, "We don't want people who are just gonna clock in, do their forty hours, and then go home. We want people who are motivated to go above and beyond their job duties!"

Why would anybody want to do that? Why would actually want to work unpaid overtime or take on extra responsibilities beyond the scope of their job that they will not be compensated for?

Well, because that's demonstrating the moral virtue of work ethic. Capitalist propaganda promises a slightly different reward. Rather than the Kingdom of Heaven, capitalism dangles the possibility of future promotions and rising through the corporate ranks some day as your incentive to do all that extra work today.

But it's the same. And in a country that's 43% Protestant specifically, it speaks to the values that many American Christians are already raised to believe: That your purpose in being alive is to suffer, to persevere, and through that perseverance, to demonstrate the moral virtue that will earn your way into Heaven.

My dad used to say, "If you have to shovel shit, you go out there and be the best damn shit shoveler they've ever seen. You do that, and you won't be shoveling shit for very long." This, in my experience, is not an opinion that is well-founded in the reality of labor economics. It's just the same ephemeral promise: Work diligently without complaint and one day your labors will be rewarded.

It's the Problem of Evil. Evil must exist because if evil did not exist then good people could not demonstrate their goodness and earn their place in Heaven. So the goal must never be to eliminate evil. A lot of people don't understand why you would even want that. If we didn't have poverty then how would we have charity?

In the same way, Americans are raised to be grateful to their capitalist overlords for bestowing on them the opportunity to thanklessly demonstrate work ethic.

This is why Americans get more pissy about "stealing jobs" and "automation" and "globalization" than they do about wage theft and anti-labor practices. The implicit contract between the classes is not that the underclass will do work and the upper class will pay them for it. It's that the upper class will provide the underclass with opportunities to demonstrate work ethic, and the underclass will compensate the upper class for it.

To many Americans, they are not paying us for our labor. We are paying them for providing us with jobs. And when those jobs are taken away from us, we get upset. We don't want a society where we all live comfortably and don't have to work, because having opportunities to do work is the sole purpose of the economy in the eyes of many Americans.

This is also why Americans see a robust system of welfare as enabling moral failure. If demonstrating work ethic gives you value as a human being, then what does that say about people who aren't working? Why should my tax dollars got to support people who are, by definition, demonstrating immorality by not working? Am I to reimburse gamblers who blew all their money on poker chips next?

Do note that, like many things, racism is also a key player in all this. Demonizing people for failing to demonstrate work ethic has its roots in rich white people furious that their slaves would desire freedom over working in their plantations. Blasting the underclass as "lazy" if they don't want to do slave labor is a tale older than United States history.

But it's all interconnected. The intermarriage of the Protestant Work Ethic and capitalist interests has woven a wide net over the way Americans think about the economy and labor.

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

"I know my parent is consistently horrible, but my kid deserves a relationship with their grandparent" no, your kid deserves a relationship with a warm, loving, supportive elder, and your horrible parent has already destroyed the chances of their being that person by not being that person. Shitty people carry on being shitty because people feel obligated to keep them around no matter what. Don't buy into it. They might be capable of change, but they're never gonna start down that road until there are actual, palpable consequences for being shitty.

The real question is, why do you think having a relationship with a grandparent is an intrinsic good? What do you hope your kid gets out of it?

If it's just another loving adult in their life, there are plenty of candidates! Family is what you make.

If it's a connection with their heritage, there are other ways to do that. Look for other members of that community, education groups, resources, local events, etc. Maybe that means you need to reconnect to that heritage so you can be that person for your kid yourself.

If it's a way to give them a mentor who can provide a perspective from a previous generation, other people of that generation exist. Maybe you already know them, maybe you can encourage your kid to volunteer in places where they can connect with those folks. (Or volunteer with your kid, my mom did that with us a lot.)

If it's because you're determined to retain your own relationship with your parent and you think their role as a grandparent is part of that, no. Relationships aren't transitive, and your obligation to protect and nurture your child far outweighs any obligation you may feel to that parent. If your parent doesn't want a relationship with you unless they can also have one with the kid, then I'm so sorry, but they don't want a relationship with you, and it's going to be up to you to sort through the feelings that brings up.

If it's just a vague sense that this is the way things "should" be, also no. Western societal pressures around family structures turn out to be really bad for the development of a functional and emotionally healthy human person, actually. Plenty of people do not have their grandparents in their lives for whatever reason. Grandparents are not a value-add by virtue of existing. They can enrich a child's life by acting in ways that enrich a child's life, no more and no less. If you wouldn't want your kid around this person if there were no familial connection, your kid should not be around this person. Putting that into practice may be hard as hell, but the core truth really is that simple.

#not about me#just reading some advice columns and ranting#though i never did meet my dad's dad#and gather this was for the best#family

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is Orange?

Disclaimer: Please enjoy? Accept? Beware? This… Thing that started out as character analysis and turned into a deranged fanfic, because I experienced a literal revelation mid-way through free writing. I did not clean this up much because I’m still reeling from the theory implications myself. I cursed a lot.

~

What does Orange Side represent?

What do we know?

Orange is a “Dark Side”, defined as being one of the Sides hidden from C!Thomas.

The other Hidden Sides were Janus, Remus, and Virgil.

All the Hidden Sides were hidden due to a key aspect of their character that C!Thomas had to first acknowledge and then accept. Virgil required C!Thomas to acknowledge that he had heightened anxiety and accept that anxiety isn’t inherently wrong, just a different form of information that can be processed. Remus required C!Thomas to acknowledge that he had intrusive thoughts and accept that those thoughts don’t make him evil; they’re just thoughts. Janus required C!Thomas to acknowledge that he was capable of lying and accept that acting “selfishly” sometimes isn’t just okay, but actually critically important to managing stress.

What are the common themes here?

Confronting the reality about ourselves instead of pretending some traits don’t exist.

Understanding ourselves to be more complex than ‘good’ and ‘evil’.

Addressing mental health.

Orange Side is still hidden, but we can expect him to be something C!Thomas doesn’t want to (or isn’t ready to) acknowledge. Something that would be difficult to accept about oneself. All Hidden Sides fall under the jurisdiction of Janus, so let’s take another look at him.

In “Can Lying Be Good?” we get a lot of information about what Janus’ purpose is:

Roman: It you really don’t want to know something, he… can keep our mouths shut.

Logan: You don’t want to believe it. That’s where his power comes from. Things that you want to believe. Things that you wish were true. And things that you wish weren’t.

Deceit: What you don’t know can’t hurt you.

This all means that Orange Side is something that would cause C!Thomas distress to learn and something he subconsciously wishes weren’t true. This is not new information to most of you: the spin-off interpretations of Apathy and Pride are widely popular fandom theories, traits that are typically viewed as negative in large doses.

But the Hidden Sides being seen as something negative isn’t their only defining characteristic. They typically involve an aspect a mental health, involve societal expectations, and... what is it...

Janus is the umbrella over all the other Hidden Sides, sheltering and obscuring them from view. He is the gatekeeper in a very literal sense. What is he gatekeeping?

What is it? What is it what is it, why? What does he do? What seems bad but isn’t? What can he do? What issue is actually useful? What’s useful what’s useful WHATS USEFUL WHATS USEFUL?! WHY DOES IT HAVE TO USEFUL?

shitshitSHITSHISTHISTSTs

I KEPT ASKING MYSELF, WHAT’S USEFUL? WHAT TRAIT COULD IT BE THAT APPEARS BAD, BUT ISN’T BAD, IS ACTUALLY USEFUL. ANIEXTY WAS OKAY BECAUSE HE WAS JUST LOOKING OUT FOR US. LYING WAS OKAY BECAUSE HE JUST WANTED TO PUT C!THOMAS FIRST. INTRUSIVE CREATIVITY WAS OKAY BECAUSE DARK IDEAS OPEN UP NEW PATHS.

But the whole GODDAMN POINT is ACCEPTANCE!

You don’t HAVE to be useful to be accepted. You – yuo just BE. YOU BE!

PEOPLE don’t have to prove their Usefulness to you before you can treat them with respect. Our WORTH does not depend on what we PRODUCE. YE GODS, THE COGNITIVE DISSONANCE I JUST BROKE-

~~~

C!Thomas comes back from his self-care stay-cation. He’s ready to start production, he is rested and refreshed. BUT JUST LIKE EVERY PREVIOUS DILEMMA, it isn’t Good enough, Original enough, Fast enough. He’s done everything right, why is it still wrong? He’s accepted his anxiety, he’s accepted that things aren’t just black and white, he’s Accepted That It’s OKAY to have Dark Thoughts, he Has ACCEPTED SELF_CARE. Why Isn’t IT ENOUGH?!

“Fuck it.”

C!Thomas spins in his chair, looking at a man that looks just like him, but not quite.

“What?”

“Fuck it. Fuck them.”

“You sound like Remus,” Thomas jokes. He’s lying, of course. He’s nervous. The Side looks like a normal guy, but something about him is unsettling. The unidentified Side just presses his lips together, unimpressed.

“Um, ef w-who, exactly?” Thomas asks, but part of him already knows.

“All of them. Every person who isn’t you. Every person who expects something from you.”

“Now, you sound like Janus.” Thomas looks back at the computer screen, but the Side’s retort has him spinning around again.

“Janus is a short-sighted pseudo-rebellious minion of a capitalistic society, just like the rest of them.”

“Uh, excuse me?!”

“Isn’t it obvious? They’re all obsessed with Success. Whether they want to play by the rules, or manipulate them, or break them, whether it’s making money or pumping out good deeds, they’re still just trying to make you be successful within the framework of a system that prioritizes production over a human life.”

Thomas just stares for a moment before he can find his voice.

“Who are you?”

“Dude, seriously?” He waves his hands, palms up and presenting himself. “I’m Achilleus. I’m your motivation.”

~~~

Take a deep breath and follow me down the research black hole, where every topic I looked up was more and more terrifyingly appropriate:

Freedom

noun

the power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint.

Self-Determination

noun

the process by which a person controls their own life.

Autonomy

noun

(in Kantian moral philosophy) the capacity of an agent to act in accordance with objective morality rather than under the influence of desires.

Autonomic Nervous System (because i believe each Hidden Side is closer to the subconscious)

noun

the part of the nervous system responsible for control of the bodily functions not consciously directed, such as breathing, the heartbeat, and digestive processes.

Inherent Value

“inherent value in the case of animal ethics can be described as the value an animal possesses in its own right, as an end-in-itself” – Animal Rights – Inherent Value, by Saahil Papar

Intrinsic Value

“Intrinsic value has traditionally been thought to lie at the heart of ethics. Philosophers use a number of terms to refer to such value. The intrinsic value of something is said to be the value that that thing has “in itself,” or “for its own sake,” or “as such,” or “in its own right.”” – Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value, by Michael J. Zimmerman and Ben Bradley

“Finally, his sense of respect for the intrinsic value of entities, including the non-sentient, is the Kantian notion of the inherent value of all Being. This is based on the notion that a universe without moral evaluators (e.g. humans) would still be morally valuable, and there is no reason not to regard Being as inherently morally good.” – Technology and the Trajectory of Myth, by David Grant, Lyria Bennett Moses

Motivation

“Another way to conceptualize motivation is through Self-Determination Theory … which is concerned with intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation happens when someone does something for its inherent satisfaction.” – Second Language Acquisition Myths: Applying Second Language Research to Classroom Teaching, by Steven Brown, Jenifer Larson-Hall

Capitalism

“The flowery language of the United States Declaration of Independence would have you believe that human life has an inherent value, one that includes inalienable rights such as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But in America, a major indicator of value is actually placed on being a productive member of society, which typically means working a job that creates monetary revenue (especially if the end result is accumulated wealth and suffering was inherently involved in the process).” – The Diminished Value of Human Life in a Capitalistic Society, by Seren Sensei

Religion

“At the heart of the debate between Calvinism and Arminianism lay the insurmountable chasm between God’s sovereign election versus human self-determination.” – Sovereignty vs. Self-determination: Two Versions of Ephesians 1:3-14, by Reformed Theology

Mythology

“In Classical Greece, Achilles was widely admired as a paragon of male excellence and virtue. Later, during the height of the Roman Empire, his name became synonymous with uncontrollable rage and barbarism… He chooses kleos (glory) over life itself, and he owes his heroic identity to this kleos. He achieves the major goal of the hero: to have his identity put permanently on record through kleos…

“But is this really an accurate characterization of Achilles' pivotal decision? Is he really driven to sacrifice his life by an obsessive quest for honor and glory? One scene in the Iliad suggests the answer to both questions is no.

“When Achilles leaves the battlefield after his dispute with Agamemnon, the Trojans gain the upper hand on the Greeks. Desperate to convince their best warrior to return, Agamemnon sends an envoy of Achilles' closest friends to his tent to persuade him to reconsider his decision. During this scene, Achilles calmly informs his friends that he is no longer interested in giving up his life for the sake of heroic ideals. His exact words are below:

“The same honor waits for the coward and the brave. They both go down to Death, the fighter who shirks, the one who works to exhaustion (IX 386-388)…

“Not only does Achilles reject the envoy's offers of material reward, but he rejects the entire premise that glory is worth a man's life.” – making sense of a hero’s motivation, by Patrick Garvey

Achilles (/əˈkɪliːz/ ə-KIL-eez) or Achilleus (Ancient Greek: Ἀχιλλ��ύς, [a.kʰilˈleu̯s])

Achilles realizes his own inherent self-worth, thereby freeing himself from the expectations of others; societal or otherwise. Only once we are free can we find the balance between our own needs and the needs of others in a way that breeds neither anger nor resentment in either.

~~~

But that’s... that’s just... a theory. Huh.

#sanders sides theory#orange side#orange side theory#sanders sides#character thomas#cursing tw#swearing tw#dark sides#the others#janus sanders#virgil sanders#remus sanders#orange sanders#caps tw#name theory#long post#missfay#my writing

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond Compassion and Humanity; Justice for Non-human Animals by Martha Nussbaum

-

This is a great essay vegans can draw on for a virtue ethics answer to the question of why do we hold the principle that it's almost always wrong to breed sentient life into captivity?

So for myself and this strain of virtue ethicists it would be because you know you could leave room for other animals to enjoy happy flourishing, being able to express all their capabilities in wild habitat.

Therefore not wanting to parasitically take away life with meaning for low-order pleasure in our hierarchy of needs which we can find elsewhere.

The distinction between this philosophy and consequentialism would simply be if you wished to act this way because fundimentally it’s about who you want to be and who you want to let animal be:

It goes beyond the contractarian view in its starting point, a basic wonder at living beings, and a wish for their flourishing and for a world in which creatures of many types flourish. It goes beyond the intuitive starting point of utilitarianism because it takes an interest not just in pleasure and pain [and interests], but in complex forms of life. It wants to see each thing flourish as the sort of thing it is. . .[and] that the dignity of living organisms not be violated.

Counter-intuitively the author does still cling to a hedonistic view of the right to take life, but hopefully not for much longer:

If animals were really killed in a painless fashion, after a healthy and free-ranging life, what then? Killings of extremely young animals would still be problematic, but it seems unclear that the balance of considerations supports a complete ban on killings for food.

-

BEYOND “COMPASSION AND HUMANITY”

Justice for Non-human Animals

MARTHA C. NUSSBAUM

Certainly it is wrong to be cruel to animals… The capacity for feelings of pleasure and pain and for the forms of life of which animals are capable clearly impose duties of compassion and humanity in their case. I shall not attempt to explain these considered beliefs. They are outside the scope of the theory of justice, and it does not seem possible to extend the contract doctrine so as to include them in a natural way.

—JOHN RAWLS, A Theory of Justice

In conclusion, we hold that circus animals…are housed in cramped cages, subjected to fear, hunger, pain, not to mention the undignified way of life they have to live, with no respite and the impugned notification has been issued in conformity with the…values of human life, [and] philosophy of the Constitution… Though not homo-sapiens [sic], they are also beings entitled to dignified existence and humane treatment sans cruelty and torture… Therefore, it is not only our fundamental duty to show compassion to our animal friends, but also to recognise and protect their rights…If humans are entitled to fundamental rights, why not animals?

—NAIR V. UNION OF INDIA, Kerala High Court, June 2000

-

“BEINGS ENTITLED TO DIGNIFIED EXISTENCE”

In 55 B.C. the Roman leader Pompey staged a combat between humans and elephants. Surrounded in the arena, the animals perceived that they had no hope of escape. According to Pliny, they then ―entreated the crowd, trying to win their compassion with indescribable gestures, bewailing their plight with a sort of lamentation.‖ The audience, moved to pity and anger by their plight, rose to curse Pompey, feeling, writes Cicero, that the elephants had a relation of commonality (societas) with the human race. [1]

We humans share a world and its scarce resources with other intelligent creatures. These creatures are capable of dignified existence, as the Kerala High Court says. It is difficult to know precisely what we mean by that phrase, but it is rather clear what it does not mean: the conditions of the circus animals in the case, squeezed into cramped, filthy cages, starved, terrorized, and beaten, given only the minimal care that would make them presentable in the ring the following day. The fact that humans act in ways that deny animals a dignified existence appears to be an issue of justice, and an urgent one, although we shall have to say more to those who would deny this claim. There is no obvious reason why notions of basic justice, entitlement, and law cannot be extended across the species barrier, as the Indian court boldly does.

Before we can perform this extension with any hope of success, however, we need to get clear about what theoretical approach is likely to prove most adequate. I shall argue that the capabilities approach as I have developed it—an approach to issues of basic justice and entitlement and to the making of fundamental political principles [2] —provides better theoretical guidance in this area than that supplied by contractarian and utilitarian approaches to the question of animal entitlements, because it is capable of recognizing a wide range of types of animal dignity, and of corresponding needs for flourishing.

-

KANTIAN CONTRACTARIANISM: INDIRECT DUTIES, DUTIES OF COMPASSION

Kant’s own view about animals is very unpromising. He argues that all duties to animals are merely indirect duties to humanity, in that (as he believes) cruel or kind treatment of animals strengthens tendencies to behave in similar fashion to humans. Thus he rests the case for decent treatment of animals on a fragile empirical claim about psychology. He cannot conceive that beings who (in his view) lack self-consciousness and the capacity for moral reciprocity could possibly be objects of moral duty. More generally, he cannot see that such a being can have dignity, an intrinsic worth.

One may, however, be a contractarian—and indeed, in some sense a Kantian— without espousing these narrow views. John Rawls insists that we have direct moral duties to animals, which he calls ―duties of compassion and humanity. [3] But for Rawls these are not issues of justice, and he is explicit that the contract doctrine cannot be extended to deal with these issues, because animals lack those properties of human beings ―in virtue of which they are to be treated in accordance with the principles of justice‖ (TJ 504). Only moral persons, defined with reference to the ―two moral powers,‖ are subjects of justice.

To some extent, Rawls is led to this conclusion by his Kantian conception of the person, which places great emphasis on rationality and the capacity for moral choice. But it is likely that the very structure of his contractarianism would require such a conclusion, even in the absence of that heavy commitment to rationality. The whole idea of a bargain or contract involving both humans and non-human animals is fantastic, suggesting no clear scenario that would assist our thinking. Although Rawls’s Original Position, like the state of nature in earlier contractarian theories, [4] is not supposed to be an actual historical situation, it is supposed to be a coherent fiction that can help us think well. This means that it has to have realism, at least, concerning the powers and needs of the parties and their basic circumstances. There is no comparable fiction about our decision to make a deal with other animals that would be similarly coherent and helpful. Although we share a world of scarce resources with animals, and although there is in a sense a state of rivalry among species that is comparable to the rivalry in the state of nature, the asymmetry of power between humans and non-human animals is too great to imagine the bargain as a real bargain. Nor can we imagine that the bargain would actually be for mutual advantage, for if we want to protect ourselves from the incursions of wild animals, we can just kill them, as we do. Thus, the Rawlsian condition that no one party to the contract is strong enough to dominate or kill all the others is not met. Thus Rawls’s omission of animals from the theory of justice is deeply woven into the very idea of grounding principles of justice on a bargain struck for mutual advantage (on fair terms) out of a situation of rough equality.

To put it another way, all contractualist views conflate two questions, which might have been kept distinct: Who frames the principles? And for whom are the principles framed? That is how rationality ends up being a criterion of membership in the moral community: because the procedure imagines that people are choosing principles for themselves. But one might imagine things differently, including in the group for whom principles of justice are included many creatures who do not and could not participate in the framing.

We have not yet shown, however, that Rawls’s conclusion is wrong. I have said that the cruel and oppressive treatment of animals raises issues of justice, but I have not really defended that claim against the Rawlsian alternative. What exactly does it mean to say that these are issues of justice, rather than issues of ―compassion and humanity? The emotion of compassion involves the thought that another creature is suffering significantly, and is not (or not mostly) to blame for that suffering. [5] It does not involve the thought that someone is to blame for that suffering. One may have compassion for the victim of a crime, but one may also have compassion for someone who is dying from disease (in a situation where that vulnerability to disease is nobody’s fault). ―Humanity I take to be a similar idea. So compassion omits the essential element of blame for wrongdoing. That is the first problem. But suppose we add that element, saying that duties of compassion involve the thought that it is wrong to cause animals suffering. That is, a duty of compassion would not be just a duty to have compassion, but a duty, as a result of one’s compassion, to refrain from acts that cause the suffering that occasions the compassion. I believe that Rawls would make this addition, although he certainly does not tell us what he takes duties of compassion to be. What is at stake, further, in the decision to say that the mistreatment of animals is not just morally wrong, but morally wrong in a special way, raising questions of justice?

This is a hard question to answer, since justice is a much-disputed notion, and there are many types of justice, political, ethical, and so forth. But it seems that what we most typically mean when we call a bad act unjust is that the creature injured by that act has an entitlement not to be treated in that way, and an entitlement of a particularly urgent or basic type (since we do not believe that all instances of unkindness, thoughtlessness, and so forth are instances of injustice, even if we do believe that people have a right to be treated kindly, and so on). The sphere of justice is the sphere of basic entitlements. When I say that the mistreatment of animals is unjust, I mean to say not only that it is wrong of us to treat them in that way, but also that they have a right, a moral entitlement, not to be treated in that way. It is unfair to them. I believe that thinking of animals as active beings who have a good and who are entitled to pursue it naturally leads us to see important damages done to them as unjust. What is lacking in Rawls’s account, as in Kant’s (though more subtly) is the sense of the animal itself as an agent and a subject, a creature in interaction with whom we live. As we shall see, the capabilities approach does treat animals as agents seeking a flourishing existence; this basic conception, I believe, is one of its greatest strengths.

-

UTILITARIANISM AND ANIMAL FLOURISHING

Utilitarianism has contributed more than any other ethical theory to the recognition of animal entitlements. Both Bentham and Mill in their time and Peter Singer in our own have courageously taken the lead in freeing ethical thought from the shackles of a narrow species-centered conception of worth and entitlement. No doubt this achievement was connected with the founders’ general radicalism and their skepticism about conventional morality, their willingness to follow the ethical argument wherever it leads. These remain very great virtues in the utilitarian position. Nor does utilitarianism make the mistake of running together the question “who receives justice?” With the question “who frames the principles of justice?” Justice is sought for all sentient beings, many of whom cannot participate in the framing of principles.

Thus it is in a spirit of alliance that those concerned with animal entitlements might address a few criticisms to the utilitarian view. There are some difficulties with the utilitarian view, in both of its forms. As Bernard Williams and Amartya Sen usefully analyze the utilitarian position, it has three independent elements: consequentialism (the right choice is the one that produces the best overall consequences), sum-ranking (the utilities of different people are combined by adding them together to produce a single total), and hedonism, or some other substantive theory of the good (such as preference satisfaction). [6] Consequentialism by itself causes the fewest difficulties, since one may always adjust the account of well-being, or the good, in consequentialism so as to admit many important things that utilitarians typically do not make salient: plural and heterogeneous goods, the protection of rights, even personal commitments or agent-centred goods. More or less any moral theory can be consequentialized, that is, put in a form where the matters valued by that theory appear in the account of consequences to be produced. [7] Although I do have some doubts about a comprehensive consequentialism as the best basis for political principles in a pluralistic liberal society, I shall not comment on them at present, but shall turn to the more evidently problematic aspects of the utilitarian view. [8]

Let us next consider the utilitarian commitment to aggregation, or what is called ―sum-ranking. Views that measure principles of justice by the outcome they produce need not simply add all the relevant goods together. They may weight them in other ways. For example, one may insist that each and every person has an indefeasible entitlement to come up above a threshold on certain key goods. In addition, a view may, like Rawls’s view, focus particularly on the situation of the least well off, refusing to permit inequalities that do not raise that person’s position. These ways of considering well-being insist on treating people as ends: They refuse to allow some people’s extremely high well-being to be purchased, so to speak, through other people’s disadvantage. Even the welfare of society as a whole does not lead us to violate an individual, as Rawls says.

Utilitarianism notoriously refuses such insistence on the separateness and inviolability of persons. Because it is committed to the sum-ranking of all relevant pleasures and pains (or preference satisfactions and frustrations), it has no way of ruling out in advance results that are extremely harsh toward a given class or group. Slavery, the lifelong subordination of some to others, the extremely cruel treatment of some humans or of non-human animals—none of this is ruled out by the theory’s core conception of justice, which treats all satisfactions as fungible in a single system. Such results will be ruled out, if at all, by empirical considerations regarding total or average well-being. These questions are notoriously indeterminate (especially when the number of individuals who will be born is also unclear, a point I shall take up later). Even if they were not, it seems that the best reason to be against slavery, torture, and lifelong subordination is a reason of justice, not an empirical calculation of total or average well-being. Moreover, if we focus on preference satisfaction, we must confront the problem of adaptive preferences. For while some ways of treating people badly always cause pain (torture, starvation), there are ways of subordinating people that creep into their very desires, making allies out of the oppressed. Animals too can learn submissive or fear-induced preferences. Martin Seligman’s experiments, for example, show that dogs who have been conditioned into a mental state of learned helplessness have immense difficulty learning to initiate voluntary movement, if they can ever do so. [9]

There are also problems inherent in the views of the good most prevalent within utilitarianism: hedonism (Bentham) and preference satisfaction (Singer). Pleasure is a notoriously elusive notion. Is it a single feeling, varying only in intensity and duration, or are the different pleasures as qualitatively distinct as the activities with which they are associated? Mill, following Aristotle, believed the latter, but if we once grant that point, we are looking at a view that is very different from standard utilitarianism, which is firmly wedded to the homogeneity of good. [10]

Such a commitment looks like an especially grave error when we consider basic political principles. For each basic entitlement is its own thing, and is not bought off, so to speak, by even a very large amount of another entitlement. Suppose we say to a citizen: We will take away your free speech on Tuesdays between 3 and 4P.M., but in return, we will give you, every single day, a double amount of basic welfare and health care support. This is just the wrong picture of basic political entitlements. What is being said when we make a certain entitlement basic is that it is important always and for everyone, as a matter of basic justice. The only way to make that point sufficiently clearly is to preserve the qualitative separateness of each distinct element within our list of basic entitlements.

Once we ask the hedonist to admit plural goods, not commensurable on a single quantitative scale, it is natural to ask, further, whether pleasure and pain are the only things we ought to be looking at. Even if one thinks of pleasure as closely linked to activity, and not simply as a passive sensation, making it the sole end leaves out much of the value we attach to activities of various types. There seem to be valuable things in an animal’s life other than pleasure, such as free movement and physical achievement, and also altruistic sacrifice for kin and group. The grief of an animal for a dead child or parent, or the suffering of a human friend, also seem to be valuable, a sign of attachments that are intrinsically good. There are also bad pleasures, including some of the pleasures of the circus audience—and it is unclear whether such pleasures should even count positively in the social calculus. Some pleasures of animals in harming other animals may also be bad in this way.

Does preference utilitarianism do better? We have already identified some problems, including the problem of misinformed or malicious preferences and that of adaptive (submissive) preferences. Singer’s preference utilitarianism, moreover, defining preference in terms of conscious awareness, has no room for deprivations that never register in the animal’s consciousness.

But of course animals raised under bad conditions can’t imagine the better way of life they have never known, and so the fact that they are not living a more flourishing life will not figure in their awareness. They may still feel pain, and this the utilitarian can consider. What the view cannot consider is all the deprivation of valuable life activity that they do not feel.

Finally, all utilitarian views are highly vulnerable on the question of numbers. The meat industry brings countless animals into the world who would never have existed but for that. For Singer, these births of new animals are not by themselves a bad thing: Indeed, we can expect new births to add to the total of social utility, from which we would then subtract the pain such animals suffer. It is unclear where this calculation would come out. Apart from this question of indeterminacy, it seems unclear that we should even say that these births of new animals are a good thing, if the animals are brought into the world only as tools of human rapacity.

So utilitarianism has great merits, but also great problems.

-

TYPES OF DIGNITY, TYPES OF FLOURISHING: EXTENDING THE CAPABILITIES APPROACH

The capabilities approach in its current form starts from the notion of human dignity and a life worthy of it. But I shall now argue that it can be extended to provide a more adequate basis for animal entitlements than the other two theories under consideration. The basic moral intuition behind the approach concerns the dignity of a form of life that possesses both deep needs and abilities; its basic goal is to address the need for a rich plurality of life activities. With Aristotle and Marx, the approach has insisted that there is waste and tragedy when a living creature has the innate, or ―basic,‖ capability for some functions that are evaluated as important and good, but never gets the opportunity to perform those functions. Failures to educate women, failures to provide adequate health care, failures to extend the freedoms of speech and conscience to all citizens—all these are treated as causing a kind of premature death, the death of a form of flourishing that has been judged to be worthy of respect and wonder. The idea that a human being should have a chance to flourish in its own way, provided it does no harm to others, is thus very deep in the account the capabilities approach gives of the justification of basic political entitlements.

The species norm is evaluative, as I have insisted; it does not simply read off norms from the way nature actually is. The difficult questions this valuational exercise raises for the case of non-human animals will be discussed in the following section. But once we have judged that a central human power is one of the good ones, one of the ones whose flourishing defines the good of the creature, we have a strong moral reason for promoting its flourishing and removing obstacles to it.

-

Dignity and Wonder: The Intuitive Starting Point

The same attitude to natural powers that guides the approach in the case of human beings guides it in the case of all forms of life. For there is a more general attitude behind the respect we have for human powers, and it is very different from the type of respect that animates Kantian ethics. For Kant, only humanity and rationality are worthy of respect and wonder; the rest of nature is just a set of tools. The capabilities approach judges instead, with the biologist Aristotle (who criticized his students’ disdain for the study of animals), that there is something wonderful and wonder-inspiring in all the complex forms of animal life.

Aristotle’s scientific spirit is not the whole of what the capabilities approach embodies, for we need, in addition, an ethical concern that the functions of life not be impeded, that the dignity of living organisms not be violated. And yet, if we feel wonder looking at a complex organism, that wonder at least suggests the idea that it is good for that being to flourish as the kind of thing it is. And this idea is next door to the ethical judgment that it is wrong when the flourishing of a creature is blocked by the harmful agency of another. That more complex idea lies at the heart of the capabilities approach.

So I believe that the capabilities approach is well placed, intuitively, to go beyond both contractarian and utilitarian views. It goes beyond the contractarian view in its starting point, a basic wonder at living beings, and a wish for their flourishing and for a world in which creatures of many types flourish. It goes beyond the intuitive starting point of utilitarianism because it takes an interest not just in pleasure and pain, but in complex forms of life. It wants to see each thing flourish as the sort of thing it is.

-

By Whom and for Whom? The Purposes of Social Cooperation

For a contractarian, as we have seen, the question ―Who makes the laws and principles? is treated as having, necessarily, the same answer as the question ―For whom are the laws and principles made? That conflation is dictated by the theory’s account of the purposes of social cooperation. But there is obviously no reason at all why these two questions should be put together in this way. The capabilities approach, as so far developed for the human case, looks at the world and asks how to arrange that justice be done in it. Justice is among the intrinsic ends that it pursues. Its parties are imagined looking at all the brutality and misery, the goodness and kindness of the world and trying to think how to make a world in which a core group of very important entitlements, inherent in the notion of human dignity, will be protected. Because they look at the whole of the human world, not just people roughly equal to themselves, they are able to be concerned directly and non-derivatively, as we saw, with the good of the mentally disabled. This feature makes it easy to extend the approach to include human-animal relations.

Let us now begin the extension. The purpose of social cooperation, by analogy and extension, ought to be to live decently together in a world in which many species try to flourish. (Cooperation itself will now assume multiple and complex forms.) The general aim of the capabilities approach in charting political principles to shape the human-animal relationship would be, following the intuitive ideas of the theory, that no animal should be cut off from the chance at a flourishing life and that all animals should enjoy certain positive opportunities to flourish. With due respect for a world that contains many forms of life, we attend with ethical concern to each characteristic type of flourishing and strive that it not be cut off or fruitless.

Such an approach seems superior to contractarianism because it contains direct obligations of justice to animals; it does not make these derivative from or posterior to the duties we have to fellow humans, and it is able to recognize that animals are subjects who have entitlements to flourishing and who thus are subjects of justice, not just objects of compassion. It is superior to utilitarianism because it respects each individual creature, refusing to aggregate the goods of different lives and types of lives. No creature is being used as a means to the ends of others, or of society as a whole. The capabilities approach also refuses to aggregate across the diverse constituents of each life and type of life. Thus, unlike utilitarianism, it can keep in focus the fact that each species has a different form of life and different ends; moreover, within a given species, each life has multiple and heterogeneous ends.

-

How Comprehensive?

In the human case, the capabilities approach does not operate with a fully comprehensive conception of the good, because of the respect it has for the diverse ways in which people choose to live their lives in a pluralistic society. It aims at securing some core entitlements that are held to be implicit in the idea of a life with dignity, but it aims at capability, not functioning, and it focuses on a small list. In the case of human-animal relations, the need for restraint is even more acute, since animals will not in fact be participating directly in the framing of political principles, and thus they cannot revise them over time should they prove inadequate.

And yet there is a countervailing consideration: Human beings affect animals’ opportunities for flourishing pervasively, and it is hard to think of a species that one could simply leave alone to flourish in its own way. The human species dominates the other species in a way that no human individual or nation has ever dominated other humans. Respect for other species’ opportunities for flourishing suggests, then, that human law must include robust, positive political commitments to the protection of animals, even though, had human beings not so pervasively interfered with animals’ ways of life, the most respectful course might have been simply to leave them alone, living the lives that they make for themselves.

-

The Species and the Individual

What should the focus of these commitments be? It seems that here, as in the human case, the focus should be the individual creature. The capabilities approach attaches no importance to increased numbers as such; its focus is on the well-being of existing creatures and the harm that is done to them when their powers are blighted.

As for the continuation of species, this would have little moral weight as a consideration of justice (though it might have aesthetic significance or some other sort of ethical significance), if species were just becoming extinct because of factors having nothing to do with human action that affects individual creatures. But species are becoming extinct because human beings are killing their members and damaging their natural environments. Thus, damage to species occurs through damage to individuals, and this individual damage should be the focus of ethical concern within the capabilities approach.

-

Do Levels of Complexity Matter?

Almost all ethical views of animal entitlements hold that there are morally relevant distinctions among forms of life. Killing a mosquito is not the same sort of thing as killing a chimpanzee. But the question is: What sort of difference is relevant for basic justice? Singer, following Bentham, puts the issue in terms of sentience. Animals of many kinds can suffer bodily pain, and it is always bad to cause pain to a sentient being. If there are non-sentient or barely sentient animals—and it appears that crustaceans, mollusks, sponges, and the other creatures Aristotle called ―stationary animals‖ are such creatures—there is either no harm or only a trivial harm done in killing them. Among the sentient creatures, moreover, there are some who can suffer additional harms through their cognitive capacity: A few animals can foresee and mind their own deaths, and others will have conscious, sentient interests in continuing to live that are frustrated by death. The painless killing of an animal that does not foresee its own death or take a conscious interest in the continuation of its life is, for Singer and Bentham, not bad, for all badness, for them, consists in the frustration of interests, understood as forms of conscious awareness. [11] Singer is not, then, saying that some animals are inherently more worthy of esteem than others. He is simply saying that, if we agree with him that all harms reside in sentience, the creature’s form of life limits the conditions under which it can actually suffer harm.

Similarly, James Rachels, whose view does not focus on sentience alone, holds that the level of complexity of a creature affects what can be a harm for it. [12] What is relevant to the harm of pain is sentience; what is relevant to the harm of a specific type of pain is a specific type of sentience (e.g., the ability to imagine one’s own death). What is relevant to the harm of diminished freedom is a capacity for freedom or autonomy. It would make no sense to complain that a worm is being deprived of autonomy, or a rabbit of the right to vote.

What should the capabilities approach say about this issue? It seems to me that it should not follow Aristotle in saying that there is a natural ranking of forms of life, some being intrinsically more worthy of support and wonder than others. That consideration might have evaluative significance of some other kind, but it seems dubious that it should affect questions of basic justice.

Rachels’s view offers good guidance here. Because the capabilities approach finds ethical significance in the flourishing of basic (innate) capabilities—those that are evaluated as both good and central (see the section on evaluating animal capabilities)—it will also find harm in the thwarting or blighting of those capabilities. More complex forms of life have more and more complex capabilities to be blighted, so they can suffer more and different types of harm. Level of life is relevant not because it gives different species differential worth per se, but because the type and degree of harm a creature can suffer varies with its form of life.

At the same time, I believe that the capabilities approach should admit the wisdom in utilitarianism. Sentience is not the only thing that matters for basic justice, but it seems plausible to consider sentience a threshold condition for membership in the community of beings who have entitlements based on justice. Thus, killing a sponge does not seem to be a matter of basic justice.

-

Does the Species Matter?

For the utilitarians, and for Rachels, the species to which a creature belongs has no moral relevance. All that is morally relevant are the capacities of the individual creature: Rachels calls this view ―moral individualism.‖ Utilitarian writers are fond of comparing apes to young children and to mentally disabled humans. The capabilities approach, by contrast, with its talk of characteristic functioning and forms of life, seems to attach some significance to species membership as such. What type of significance is this?

We should admit that there is much to be learned from reflection on the continuum of life. Capacities do crisscross and overlap; a chimpanzee may have more capacity for empathy and perspectival thinking than a very young child or an older autistic child. And capacities that humans sometimes arrogantly claim for themselves alone are found very widely in nature. But it seems wrong to conclude from such facts that species membership is morally and politically irrelevant. A mentally disabled child is actually very different from a chimpanzee, though in certain respects some of her capacities may be comparable. Such a child’s life is tragic in a way that the life of a chimpanzee is not tragic: She is cut off from forms of flourishing that, but for the disability, she might have had, disabilities that it is the job of science to prevent or cure, wherever that is possible. There is something blighted and disharmonious in her life, whereas the life of a chimpanzee may be perfectly flourishing. Her social and political functioning is threatened by these disabilities, in a way that the normal functioning of a chimpanzee in the community of chimpanzees is not threatened by its cognitive endowment.

All this is relevant when we consider issues of basic justice. For a child born with Down syndrome, it is crucial that the political culture in which he lives make a big effort to extend to him the fullest benefits of citizenship he can attain, through health benefits, education, and the reeducation of the public culture. That is so because he can only flourish as a human being. He has no option of flourishing as a happy chimpanzee. For a chimpanzee, on the other hand, it seems to me that expensive efforts to teach language, while interesting and revealing, are not matters of basic justice. A chimpanzee flourishes in its own way, communicating with its own community in a perfectly adequate manner that has gone on for ages.

In short, the species norm (duly evaluated) tells us what the appropriate benchmark is for judging whether a given creature has decent opportunities for flourishing.

-

EVALUATING ANIMAL CAPABILITIES: NO NATURE WORSHIP

In the human case, the capabilities view does not attempt to extract norms directly from some facts about human nature. We should know what we can about the innate capacities of human beings, and this information is valuable, in telling us what our opportunities are and what our dangers might be. But we must begin by evaluating the innate powers of human beings, asking which ones are the good ones, the ones that are central to the notion of a decently flourishing human life, a life with dignity. Thus not only evaluation but also ethical evaluation is put into the approach from the start. Many things that are found in human life are not on the capabilities list.

There is a danger in any theory that alludes to the characteristic flourishing and form of life of a species: the danger of romanticizing nature, or suggesting that things are in order as they are, if only we would stop interfering. This danger looms large when we turn from the human case, where it seems inevitable that we will need to do some moral evaluating, to the animal case, where evaluating is elusive and difficult. Inherent in at least some environmentalist writing is a picture of nature as harmonious and wise, and of humans as wasteful overreachers who would live better were we to get in tune with this fine harmony. This image of nature was already very sensibly attacked by John Stuart Mill in his great essay ―Nature,‖ which pointed out that nature, far from being morally normative, is actually violent, heedless of moral norms, prodigal, full of conflict, harsh to humans and animals both. A similar view lies at the heart of much modern ecological thinking, which now stresses the inconstancy and imbalance of nature, [13] arguing, inter alia, that many of the natural ecosystems that we admire as such actually sustain themselves to the extent that they do only on account of various forms of human intervention.

Thus, a no-evaluation view, which extracts norms directly from observation of animals’ characteristic ways of life, is probably not going to be a helpful way of promoting the good of animals. Instead, we need a careful evaluation of both ―nature‖ and possible changes. Respect for nature should not and cannot mean just leaving nature as it is, and must involve careful normative arguments about what plausible goals might be.

In the case of humans, the primary area in which the political conception inhibits or fails to foster tendencies that are pervasive in human life is the area of harm to others. Animals, of course, pervasively cause harm, both to members of their own species and, far more often, to members of other species.

In both of these cases, the capabilities theorist will have a strong inclination to say that the harm-causing capabilities in question are not among those that should be protected by political and social principles. But if we leave these capabilities off the list, how can we claim to be promoting flourishing lives? Even though the capabilities approach is not utilitarian and does not hold that all good is in sentience, it will still be difficult to maintain that a creature who feels frustration at the inhibition of its predatory capacities is living a flourishing life. A human being can be expected to learn to flourish without homicide and, let us hope, even without most killing of animals. But a lion who is given no exercise for its predatory capacity appears to suffer greatly.

Here the capabilities view may, however, distinguish two aspects of the capability in question. The capability to kill small animals, defined as such, is not valuable, and political principles can omit it (and even inhibit it in some cases, to be discussed in the following section). But the capability to exercise one’s predatory nature so as to avoid the pain of frustration may well have value, if the pain of frustration is considerable. Zoos have learned how to make this distinction. Noticing that they were giving predatory animals insufficient exercise for their predatory capacities, they had to face the question of the harm done to smaller animals by allowing these capabilities to be exercised. Should they give a tiger a tender gazelle to crunch on? The Bronx Zoo has found that it can give the tiger a large ball on a rope, whose resistance and weight symbolize the gazelle. The tiger seems satisfied. Wherever predatory animals are living under direct human support and control, these solutions seem the most ethically sound.

-

POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE, CAPABILITY AND FUNCTIONING

In the human case, there is a traditional distinction between positive and negative duties that it seems important to call into question. Traditional moralities hold that we have a strict duty not to commit aggression and fraud, but we have no correspondingly strict duty to stop hunger or disease, nor to give money to promote their cessation. [14]

The capabilities approach calls this distinction into question. All the human capabilities require affirmative support, usually including state action. This is just as true of protecting property and personal security as it is of health care, just as true of the political and civil liberties as it is of providing adequate shelter.

In the case of animals, unlike the human case, there might appear to be some room for a positive-negative distinction that makes some sense. It seems at least coherent to say that the human community has the obligation to refrain from certain egregious harms toward animals, but that it is not obliged to support the welfare of all animals, in the sense of ensuring them adequate food, shelter, and health care. The animals themselves have the rest of the task of ensuring their own flourishing.

There is much plausibility in this contention. And certainly if our political principles simply ruled out the many egregious forms of harm to animals, they would have done quite a lot. But the contention, and the distinction it suggests, cannot be accepted in full. First of all, large numbers of animals live under humans’ direct control: domestic animals, farm animals, and those members of wild species that are in zoos or other forms of captivity. Humans have direct responsibility for the nutrition and health care of these animals, as even our defective current systems of law acknowledge. [15] Animals in the wild appear to go their way unaffected by human beings. But of course that can hardly be so in many cases in today’s world. Human beings pervasively affect the habitats of animals, determining opportunities for nutrition, free movement, and other aspects of flourishing.

Thus, while we may still maintain that one primary area of human responsibility to animals is that of refraining from a whole range of bad acts (to be discussed shortly), we cannot plausibly stop there. The only questions should be how extensive our duties are, and how to balance them against appropriate respect for the autonomy of a species.

In the human case, one way in which the approach respects autonomy is to focus on capability, and not functioning, as the legitimate political goal. But paternalistic treatment (which aims at functioning rather than capability) is warranted wherever the individual’s capacity for choice and autonomy is compromised (thus, for children and the severely mentally disabled). This principle suggests that paternalism is usually appropriate when we are dealing with non-human animals. That conclusion, however, should be qualified by our previous endorsement of the idea that species autonomy, in pursuit of flourishing, is part of the good for non-human animals. How, then, should the two principles be combined, and can they be coherently combined? I believe that they can be combined, if we adopt a type of paternalism that is highly sensitive to the different forms of flourishing that different species pursue. It is no use saying that we should just let tigers flourish in their own way, given that human activity ubiquitously affects the possibilities for tigers to flourish. This being the case, the only decent alternative to complete neglect of tiger flourishing is a policy that thinks carefully about the flourishing of tigers and what habitat that requires, and then tries hard to create such habitats. In the case of domestic animals, an intelligent paternalism would encourage training, discipline, and even, where appropriate, strenuous training focused on special excellences of a breed (such as the border collie or the hunter-jumper). But the animal, like a child, will retain certain entitlements, which they hold regardless of what their human guardian thinks about it. They are not merely objects for human beings’ use and control.

-

TOWARD BASIC POLITICAL PRINCIPLES: THE CAPABILITIES LIST

It is now time to see whether we can actually use the human basis of the capabilities approach to map out some basic political principles that will guide law and public policy in dealing with animals. The list I have defended as useful in the human case is as follows:

The Central Human Capabilities

Being able to live to the end of a human life of normal length; not dying prematurely, or before one’s life is so reduced as to be not worth living.

Bodily Health. Being able to have good health, including reproductive health; to be adequately nourished; to have adequate shelter.

Bodily Integrity. Being able to move freely from place to place; to be secure against violent assault, including sexual assault and domestic violence; having opportunities for sexual satisfaction and for choice in matters of reproduction.

Senses, Imagination, and Thought. Being able to use the senses, to imagine, think, and reason—and to do these things in a ―truly human‖ way, a way informed and cultivated by an adequate education, including, but by no means limited to, literacy and basic mathematical and scientific training. Being able to use imagination and thought in connection with experiencing and producing works and events of one’s own choice, religious, literary, musical, and so forth. Being able to use one’s mind in ways protected by guarantees of freedom of expression with respect to both political and artistic speech, and freedom of religious exercise. Being able to have pleasurable experiences and to avoid non-beneficial pain.

Emotions. Being able to have attachments to things and people outside ourselves; to love those who love and care for us and to grieve at their absence; in general, to love, to grieve, to experience longing, gratitude, and justified anger. Not having one’s emotional development blighted by fear and anxiety. (Supporting this capability means supporting forms of human association that can be shown to be crucial to our development.)

Practical Reason. Being able to form a conception of the good and to engage in critical reflection about the planning of one’s life. (This entails protection for the liberty of conscience and religious observance.)

Affiliation. (A) Being able to live with and toward others, to recognize and show concern for other human beings, to engage in various forms of social interaction; to be able to imagine the situation of another. (Protecting this capability means protecting institutions that constitute and nourish such forms of affiliation, and also protecting the freedom of assembly and political speech.) (B) Having the social bases of self-respect and non-humiliation; being able to be treated as a dignified being whose worth is equal to that of others. (This entails provisions of non-discrimination on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation, ethnicity, caste, religion, national origin.)

Other Species. Being able to live with concern for and in relation to animals, plants, and the world of nature.

Play. Being able to laugh, to play, to enjoy recreational activities.

Control over One’s Environment. (A) Political. Being able to participate effectively in political choices that govern one’s life; having the right of political participation; protections of free speech and association. (B) Material. Being able to hold property (both land and movable goods), and having property rights on an equal basis with others; having the right to seek employment on an equal basis with others; having the freedom from unwarranted search and seizure. In work, being able to work as a human being, exercising practical reason and entering into meaningful relationships of mutual recognition with other workers.

Although the entitlements of animals are species specific, the main large categories of the existing list, suitably fleshed out, turn out to be a good basis for a sketch of some basic political principles.

In the capabilities approach, all animals are entitled to continue their lives, whether or not they have such a conscious interest. All sentient animals have a secure entitlement against gratuitous killing for sport. Killing for luxury items such as fur falls in this category, and should be banned. On the other hand, intelligently respectful paternalism supports euthanasia for elderly animals in pain. In the middle are the very difficult cases, such as the question of predation to control populations, and the question of killing for food. The reason these cases are so difficult is that animals will die anyway in nature, and often more painfully. Painless predation might well be preferable to allowing the animal to be torn to bits in the wild or starved through overpopulation. As for food, the capabilities approach agrees with utilitarianism in being most troubled by the torture of living animals. If animals were really killed in a painless fashion, after a healthy and free-ranging life, what then? Killings of extremely young animals would still be problematic, but it seems unclear that the balance of considerations supports a complete ban on killings for food.

Bodily Health. One of the most central entitlements of animals is the entitlement to a healthy life. Where animals are directly under human control, it is relatively clear what policies this entails: laws banning cruel treatment and neglect; laws banning the confinement and ill treatment of animals in the meat and fur industries; laws forbidding harsh or cruel treatment for working animals, including circus animals; laws regulating zoos and aquariums, mandating adequate nutrition and space. Many of these laws already exist, although they are not well enforced. The striking asymmetry in current practice is that animals being raised for food are not protected in the way other animals are protected. This asymmetry must be eliminated.

Bodily Integrity. This goes closely with the preceding. Under the capabilities approach, animals have direct entitlements against violations of their bodily integrity by violence, abuse, and other forms of harmful treatment—whether or not the treatment in question is painful. Thus the declawing of cats would probably be banned under this rubric, on the grounds that it prevents the cat from flourishing in its own characteristic way, even though it may be done in a painfree manner and cause no subsequent pain. On the other hand, forms of training that, though involving discipline, equip the animal to manifest excellences that are part of its characteristic capabilities profile would not be eliminated.

Senses, Imagination, and Thought. For humans, this capability creates a wide range of entitlements: to appropriate education, to free speech and artistic expression, to the freedom of religion. It also includes a more general entitlement to pleasurable experiences and the avoidance of non-beneficial pain. By now it ought to be rather obvious where the latter point takes us in thinking about animals: toward laws banning harsh, cruel, and abusive treatment and ensuring animals’ access to sources of pleasure, such as free movement in an environment that stimulates and pleases the senses. The freedom-related part of this capability has no precise analogue, and yet we can come up with appropriate analogues in the case of each type of animal, by asking what choices and areas of freedom seem most important to each. Clearly this reflection would lead us to reject close confinement and to regulate the places in which animals of all kinds are kept for spaciousness, light and shade, and the variety of opportunities they offer the animals for a range of characteristic activities. Again, the capabilities approach seems superior to utilitarianism in its ability to recognize such entitlements, for few animals will have a conscious interest, as such, in variety and space.

Emotions. Animals have a wide range of emotions. All or almost all sentient animals have fear. Many animals can experience anger, resentment, gratitude, grief, envy, and joy. A small number—those who are capable of perspectival thinking—can experience compassion. [16] Like human beings, they are entitled to lives in which it is open to them to have attachments to others, to love and care for others, and not to have those attachments warped by enforced isolation or the deliberate infliction of fear. We understand well what this means where our cherished domestic animals are in question. Oddly, we do not extend the same consideration to animals we think of as ―wild. Until recently, zoos took no thought for the emotional needs of animals, and animals being used for research were often treated with gross carelessness in this regard, being left in isolation and confinement when they might easily have had decent emotional lives. [17]

Practical Reason. In each case, we need to ask to what extent the creature has a capacity to frame goals and projects and to plan its life. To the extent that this capacity is present, it ought to be supported, and this support requires many of the same policies already suggested by capability 4: plenty of room to move around, opportunities for a variety of activities.

Affiliation. In the human case, this capability has two parts: an interpersonal part (being able to live with and toward others) and a more public part, focused on self-respect and non-humiliation. It seems to me that the same two parts are pertinent for non-human animals. Animals are entitled to opportunities to form attachments (as in capability 5) and to engage in characteristic forms of bonding and interrelationship. They are also entitled to relations with humans, where humans enter the picture, that are rewarding and reciprocal, rather than tyrannical. At the same time, they are entitled to live in a world public culture that respects them and treats them as dignified beings. This entitlement does not just mean protecting them from instances of humiliation that they will feel as painful. The capabilities approach here extends more broadly than utilitarianism, holding that animals are entitled to world policies that grant them political rights and the legal status of dignified beings, whether they understand that status or not.