#Barbary Corsairs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

This is very interesting- Pirate history outside of 17th and 18th Century Europeans/colonists tends to get ignored, but I was not aware of any Barbary pirate wrecks being found- the only pirate shipwrecks I had previously been aware of being Blackbeard's Queen Anne's Revenge in North Carolina, and Bellamy's Whydah Galley off Massachusetts. So this is really quite rare, and an interesting insight into another group of pirates (who actually operated longer/on a larger scale than the so-called "Golden Age" pirates).

Also, I find it amusing that they mainly operated around the Straights of Gibraltar. I mean, it's obviously a good location for a pirate, a narrow channel near friendly territory through which a lot of shipping passes. But it's also exactly where Orcas attack yachts now, which reinforces my view of Orcas as Whale Pirates.

17th-Century Pirate 'Corsair' Shipwreck Discovered off Morocco

Wreck-hunters have discovered the remains of a small 17th-century pirate ship, known as a Barbary corsair, in deep water between Spain and Morocco.

The wreck is "the first Algiers corsair found in the Barbary heartland," maritime archaeologist Sean Kingsley, the editor-in-chief of Wreckwatch magazine and a researcher on the find, told Live Science.

The vessel was heavily armed and may have been heading to the Spanish coast to capture and enslave people when it sank, its discoverers said.

But it was carrying a cargo of pots and pans made in the North African city of Algiers, probably so that it could masquerade as a trading vessel.

Florida-based company Odyssey Marine Exploration (OME) located the shipwreck in 2005 during a search for the remains of the 80-gun English warship HMS Sussex, which was lost in the area in 1694.

"As so often happens in searching for a specific shipwreck we found a lot of sites never seen before," Greg Stemm, the founder of OME and the expedition leader, saide in an email.

The 2005 expedition also found the wrecks of ancient Roman and Phoenician ships in the area, Stemm said.

News of the corsair wreck is only being released now, in a new article by Stemm in Wreckwatch, after extensive historical research.

Dread pirates

The Barbary corsair pirates were predominantly Muslims who began operating in the 15th century out of Algiers, which was then part of the Ottoman empire.

Much of the western coastline of North Africa, from modern-day Morocco to Libya, was known as the "Barbary Coast" at the time — a name derived from the Berber people who lived there; and its pirates were a major threat for more than 200 years, preying on ships and conducting slave raids along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of Europe.

The people captured in the slave raids were held for ransom or sold into the North African slave trade that operated in some Muslim countries until the early 20th century.

But the piratical activities of the Barbary corsairs came to an end in the early 19th century, when the pirates were defeated in the Barbary Wars by the United States, Sweden and the Norman Kingdom of Sicily in southern Italy.

Sunken ship

The corsair wreck lies on the seafloor in the Strait of Gibraltar, at a depth of about 2,700 feet (830 meters).

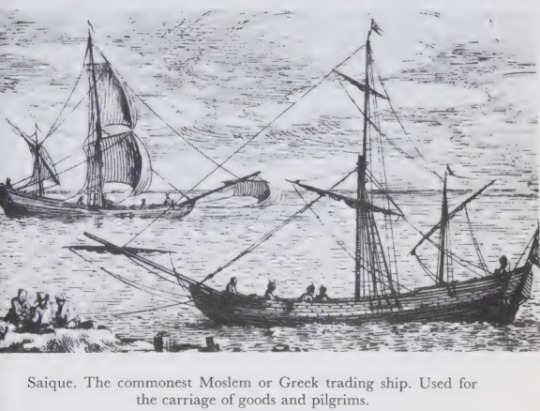

The ship was about 45 feet (14 m) long, and research indicates it was a tartane — a small ship with triangular lateen sails on two masts that could also be propelled by oars.

Tartanes were used by Barbary pirates in the 17th and 18th centuries, in part because they were often mistaken for fishing vessels, meaning other ships wouldn't suspect pirates were onboard, Kingsley said.

"I've seen tartanes described as 'low-level pirate ships,' which I like,” Kingsley said.

The wreck hunters explored the sunken corsair using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), which revealed the vessel was armed with four large cannons, 10 swivel guns and many muskets for its crew of about 20 pirates.

"The wreck neatly fits the profile of a Barbary corsair in location and character," Kingsley said. "The seas around the Straits of Gibraltar were the pirates' favorite hunting grounds, where a third of all corsair prizes were taken."

Stemm added that the wrecked ship was also equipped with a very rare "spyglass" — an early type of telescope that was revolutionary at the time and had probably been captured from a European ship.

Other artifacts of the wreck support the notion this was a pirate ship laden with stolen goods.

"Throw into the sunken mix a collection of glass liquor bottles made in Belgium or Germany, and tea bowls made in Ottoman Turkey, and the wreck looks highly suspicious," he said. "This was no normal North African coastal trader."

By Tom Metcalfe.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

#pierre jacques volaire#1765#art#battle#age of sail#boarding#pirates#corsair#corsairs#pirate#barbary pirates#ottoman#mediterranean#europe#european#history#sea#marine art#maritime#barbary coast#italy#muslim#islamic#ship#ships#boats#boat#sailors#sailor#collision

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corsairs of Malta: Legitimate Targets

"There was a constant temptation for the corsairs to attack not only Moslem shipping, but also to attack Christians. Although this was in direct contradiction of their oath, the corsairs justified their activity on various grounds. The Christians were not really Christians, they were only pretending to be Christians. If they were Christians, the goods they were carrying belonged to Turks, and thus it was legitimate to seize them. Or even if they were Christians and the goods that they carried belonged to them, they were Greek Orthodox and therefore schismatic, and therefore heretics, and therefore enemies of the Faith, and thus liable to depredation.

During the seventeenth century these unfortunate Greeks and the representatives of the other minority Christian groups in the Levant, such as the Maronites, were on their own and their only hope of recompense was to come to Malta and sue the corsairs in the island’s courts. It is some measure of the justice of the courts in Malta at this time that many Greeks who sued for wrongful depredation actually won their case and recovered damages. In the eighteenth century, however, while Maltese attitudes hardened towards the Greeks, the latter found a powerful protector in the Pope."

— Peter Earle, Corsairs of Malta and Barbary (1970)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Girl, An Ocean {A Black Sails fanfic}

Fandom: Black Sails Rating: Teen and up audiences Warnings: Graphic depictions of violence Category: Action adventure with romance Characters: Billy Bones, Hal Gates, James Flint, OC Relationships: Billy Bones/OC Additional tags: Original character-centric, canon character x original character romance, kinda alternative prequel to canon, canon compliant, slow burn, mutual pining, friends to lovers, tooth-rotting sweetness, cute but also sexy, angst galore, found family, Hal Gates has two children now Series: Part One of Six of A Girl, An Ocean Chapters: 1/13 Summary: Constance Tilly was a highborn lady sent to the America's to marry against her will. And then the ship carrying her to this fate was attacked by pirates. Not just any pirates - they get captured by none other than the infamous captain Flint. Author's note: Phew, and here it is! The fruits of my labor for the past months, still going strong! I'm having so much fun writing this unhinged piece of fanfic and I hope you enjoy it, too. Almost done with season one, then on to season two. And i already have a draft delineated for a post-show fic, JESUS CHRIST. I can't be stopped, I shan't.

Chapter i.

It was the bell toll that did it.

From the moment it was struck, confusion settled aboard. Men scrambled to their posts. Officers barked orders. People pushed and shoved for their arms, for the cannons, for things that, in my ignorance back then, I could not describe until much later. It was only for a moment that I glimpsed the looming threat across the ocean – a pirate vessel – before I was corralled with the other women and children below decks and secured within the sick bay.

In those chaotic minutes, the bell toll signaled danger. To me, though I had no idea at the time, it was the sound of freedom. I had been put aboard the HMS Delilah by my Father in March past, to traverse the Atlantic toward the New World as little more than an offering to a Governor. I was to wed his eldest son in Savannah, to secure a partnership between my family and the wealth and influence there. However, I didn't feel like a bride about to meet her true love - I felt like a bargaining chip in a transaction, a prized broodmare. Barely human.

When I had boarded that ship, I cursed my fate. I cursed my Father. I cursed the man who was to have me for a wife, it mattered not who he was or his character. Curse the lot of them. This was what I had been prepared for all my life, but until the day arrived, it had never seemed real. I always kept the vague hope it would never happen, that it was just a nightmare I would wake from. The thought of an impending pirate raid struck me with terror like any other reason-minded soul, but there was a secret feeling in my stomach that only grew as the hour of their coming neared, overtaking the fear like ivy, slowly but surely, relentlessly.

Hope.

We knew exactly when the pirates began their assault. First the cannon volleys, coming closer and closer. Then, the sound of hundreds of boots stomping back and forth on deck. Gunshots. Swords clashing. Screams. Men were dying up there. As I huddled in a corner with a stolen pistol in my hand, keeping the helpless ladies and their children behind me, it dawned on me that if our crew did not win out the day, a fate far worse than death might be in store for us. I had heard terrible stories about the pirates of Nassau and the corsairs of the Barbary coast, stories of torture, kidnapping, slavery. Recalling them chilled me to the bone, but one thing I knew for sure: I would not go down without a fight. If I had to be dragged out to my doom, I would do so with my head held high and on my feet, not cowering like a lamb awaiting the slaughter. And I would make them pay for it with their own blood.

At last... quiet. All sounds extinguished from one moment to the next. It felt like the world had stopped. Like being inside a mausoleum. Behind me, the ladies whimpered and shushed the toddlers. One babe wailed in protest, so tight his mother held him to her. We urged her to calm him down – with a bit of luck, the worst of the attack was over and the pirates would pass us by without ever knowing we were there, but as soon as the thought crossed my mind, I knew it was a lie. They would take all the valuables they could find, leaving no stone (or board, as it were) unturned, not a a single room left to pilfer. It was only a matter of time.

Minutes after silence fell, we heard heavy footsteps coming down the ladders. From the other side of the door, I heard grave voices, and laughter. Our crew and officers rarely laughed, leading me to expect the worst. With a deep breath, terrified as I might be, I brought up my pistol and pointed it at the locked door with my left hand. I had never fired a gun before. Seen plenty of men do it, however. How hard could it be? Press the trigger, the bullet explodes out. Simple.

I stole a glance behind me. “Be quiet and don't move.”

The voices drew closer. The handle turned, but the lock held shut, its key safe in my pocket next to a knife I had grabbed from the galley in our escape. Still, I knew a lock would hardly stop them.

More voices. My hand shook as sweat rolled down my forehead, my heart hammering against my throat. I steeled myself for what was to come next. I will not die here cowering. I will not die here cowering. I refuse.

A bang like two boulders crashing together shook the compartment, ripping a few gasps from behind me. Another bang, and the baby screeched like a banshee. I gripped my pistol like a life-line, my silver cross in the other, jaw clamped firmly shut. A final bang, and the door flew open in a shower of splinters. On the other side, a giant towered over us, so tall he had to duck his head to step inside. Upon seeing the barrel of my weapon pointed in his face, he hesitated.

In the seconds it took for him to evaluate the scene, I couldn't help to notice the beauty of his features: he was young, no more than 28 years old, with a strong jaw covered by the faintest shadow of a beard, full lips, big blue eyes and dusty blond hair. His face was covered in dark paint, which coupled with his stature and broad shoulders made him look barbaric and fierce, but there was a softness to his expression of confusion that made the whole "savage bloodthirsty pirate" look unconvincing.

He stared at me and I stared back while both of us waited for the other to break the tense silence. When he realized I would remain mute, he slowly raised his hands. With a shudder, I noticed they were covered in blood.

"It's alright," he said. "I'm not going to hurt you. You're safe."

Thank God my voice remained firm when I said: "We're safe. Sure." I didn't want him to know how scared I actually was. Something told me that would turn out poorly, like a dog sensing fear and getting excited into attacking. I had to show I wasn't afraid of him nor of any pirate.

"I understand it may be hard to believe, given the circumstances." His eyes flicked from the pistol to the women behind me, back to mine. "But I promise, no harm will come to any of you." He took a hesitant step towards us. "If you come with me up to the main deck--"

With a dexterity that surprised even me, I cocked the hammer with a threatening click that made him pause. It pleased me to see his Adam's apple bob from the nerves.

"Take one more step and I will shoot your face off no matter how handsome it is."

A little bravado goes a long way toward intimidating a foe out of a fight, I'd heard a cousin of mine from the military say. I prayed he was right. The giant man studied me for a sign of a lie, some tell on my body language or a shadow of fear in my eyes that would assure him I was bluffing so he could disarm me. Whatever he saw seemed to convince him I would make good on my warning, for he ducked out of the door and exchanged a few words with whomever was on the other side. All I could catch from his hushed tone was "get Gates down here."

As the other rushed away, the giant came back in and loomed over the exit, blocking it with his sheer size, one arm resting against the frame for good measure. Behind me, the babe had calmed to a cuddly whimper, and several children were sniffling (some of the grown women as well, I suspected). Tiring of holding the heavy flintlock, my arm began to cramp up, sending my hand into increasingly frequent spasms. I changed it into the other, always careful to keep a finger on the trigger. The man's nostrils flared in response, his breath stopping for a moment as I finished the exchange. If he had been worried that I might shoot him by accident, he didn't express it with words; he knew I wouldn't lower the barrel even if God Himself stepped down from heaven to order me so.

Not long after, several urgent steps approached and stopped by our door. The giant man spoke with whom I assumed was the Gates character he'd sent for, then a man in his fifties with a bold mustache about my height peeked into the room with an arched eyebrow. He seemed almost... amused? He certainly looked at the other like he was a boy who'd just done something extremely funny.

He gave the giant a pat on the shoulder and stepped into the room. Immediately, I turned the pistol on him, but he wasn't nearly as intimidated by this gesture as the taller pirate had been. My courage began to falter as I watched him take a seat on a chest by the door like he'd been invited to have tea.

"Hello," he said. "My name is Hal Gates, quartermaster of the Walrus. May I ask your name, Miss?"

It unnerved me, how calm he was. Like this was the kind of situation he found himself in on a daily basis and he'd grown so used to the routine that he knew exactly what was going to happen next, down to the second. I swallowed a lump in my throat.

"Constance," I replied, too quietly for my taste. I cleared my throat and repeated, a little louder: "My name is Constance."

"A pleasure to meet your acquaintance, Miss Constance." He bowed his bald head and tipped an invisible hat, like a gentleman would do. "Now, as I imagine, this is a frightening situation for you and your companions to be in and no one can blame you for such a... radical reaction to being attacked by pirates." He gestured lightly to my weapon. "However, in the quality of quartermaster, I can assure you that there is nothing so savage as a whole-sale slaughter going on up there. In fact, I'm here to inform you that your captain has wisely surrendered the ship to prevent further bloodshed and terms are being negociated as we speak to have the crew and all passengers on this vessel freed and unharmed, in exchange for any valuables you may have on board. We will leave you with enough provisions to continue on your way, and hopefully this will be the first and last time you will ever see a pirates in your life."

Beyond the door I heard a small chorus of snickers. The giant man, who hadn't moved from his position at the door, shushed them sternly.

Mr. Gates smiled. "Obviously, I don't expect you to take my word for it. You seem like a sharp, brave young lady and were I you, I wouldn't trust an old sea wolf like myself either. So, I propose sending for an officer of this fine ship, someone you know personally, and have him brought down here to verify my story. Just give me a name and I will have it done. What say you?"

I pondered on his proposal. My right arm was beginning to cramp as well, making it difficult to concentrate. Blasted pistols, why did they have to be so heavy? I cradled it in both hands to buy myself time and thought: if they sent for an officer, they could threaten him into lying to get us out of our defensive position. Honor would demand that any officer lay down his life to protect us, but that wasn't a certainty I was willing to gamble on. He could go along with the pirates' plot and give us up for the chance to save himself. It would cost him later, should he survive this encounter to face his employers, but when one's life is in peril, everything becomes desperate. I would know it - I was pointing a gun at a seasoned pirate to save mine, as well as those under my care. I glanced at the giant who carefully watched the conversation unfold with a hand on the cutlass that hung from his hip.

What I was about to attempt was risky, but I didn't have much of a choice. I could spend my bullet on the giant without guarantees of killing him and pull the knife on Gates, but I would be overrun by whoever else waited outside in seconds. It was either this or nothing.

Another deep breath to stabilize my nerves. “No.”

Gates' eyebrows furrowed comically. That wasn't part of your script, was it? I thought while fighting back a smirk.

“Beg pardon?” He said.

“No,” I repeated. “You will not be sending for any officers to come down here. This is what you're going to do: you and your man there will vacate this room. The ladies behind me will have my pistol and barricate themselves after I leave last. You--” I nodded to the giant. “-- will stand guard over the door and will not let anyone in or out. You--” To Gates. “– will take me to the captain so I may verify your story for myself. If you speak the truth and we are allowed to depart unharmed once you're done sacking our ship, then you will bring me back down and we stay in this room until it's safe to come out. And then we pray never to see each other again.”

A moment of silence passed whilst Gates considered my counter-proposal. The giant man traded a bewildered look with him, awaiting orders. What he made of all this, I couldn't tell. As for me, my elbows and shoulders protested the weight of the pistol to such an extent that I was certain I wouldn't last another minute holding it up. I tightened my grip once more, afraid to drop my only assurance of survival and letting this battle of wits go to waste on the account of my inferior physical prowess. If I lost the pistol, we were all doomed. That weight hung heavier on me than the gun – I would never forgive myself if the little ones died or were taken captive because of my weakness.

“These are your terms, then?” Gates finally asked.

“They are.”

He nodded slowly, then shrugged and turned to the giant, who tilted his head with an “alright then” look on his face before exiting the room to dispatch orders. Gates stood from the chest and brushed his vest off with a relaxed smile.

“I'll wait outside while you prepare yourself. Knock on the door when you're ready to go, Miss Constance.” And he left, closing the door behind him.

Convincing the other women to do as I said took longer than I had expected. They feared for their lives and that of their children, of course; but neither did they believe I should risk mine for them. It was not the place of a woman to give herself to heroics - the laws of decorum wouldn't allow for it. In the end, I asked them whether they preferred to cast decency to hell and live to practice them another day, or hang tight to it and die with their honor intact. That was enough to convince them to let me go. Maybe it was the word “hell”, liberally and literally used, that finally got their clucking to cease.

As promised, I left the pistol with the oldest boy, aged twelve, who had already shot weapons before and stood a better chance to use it properly than anyone else. I left instructions for him to keep the gun at the ready and protect the ladies and children, but to use the shot only if absolutely necessary, given it was the only one he had. Once I felt they would be secured enough, there was nothing left to do than to help them make an improvised barricade using whatever wasn't nailed down to the floor. Lastly, I knocked on the door to signal the pirates I was coming out.

It was the giant man who opened it for me. I don't know why I felt so confident leaving him to guard my companions. Perhaps it was the honest air about him, the softness of his eyes that made me feel comfortable trusting them to his care. Maybe it was his large size, surely capable of holding off a small squadron of men, that put me at ease. Either way, there was no going back, now. Too late to change strategy. It was now or never.

Mr. Gates was waiting for me at the foot of the ladder. As I advanced toward him, keeping my hand in my pocket and my fingers wrapped firmly around the knife handle, I was flanked by five or six pirates on either side, who observed my every step like blood hounds sniffing prey. Some were curious, others apprehensive. Some were even entertained by the notion of a lady in a pink silk gown and pearls walking in their midst. I tried not to think about the filthy images they were concocting in their heads. After what felt like an eternity, I reached Mr. Gates, who lead me up and out of those suffocating quarters. On the way, we passed by a few more pirates, too eager to begin their sacking to wait for the captains to finish agreeing on their terms. I was surprised to see such a variety of races among them: black men, Mughals, east Asian men. One of them drew his attention away from their plunder to greet Gates. He had mahogany skin, arms covered in a lattice of dots and a smile so bright it illuminated the lower deck. When he saw me, it widened to a cheeky grin, but when he attempted to joke, Gates ordered him to go back to work, that I was a guest to be treated with respect, not a prisoner. Unbothered by this firm shut-down, the man returned to his task with a chuckle and left us alone.

We continued our ascent. Now I could see more people, including the Delilah's own crewmen and officers being held at gun and sword point by the pirates. When they saw me with Gates, their faces paled up in horror. One officer, braver than the others, tried to get past his captor to defend me before he was hit across the cheek with a pommel and told to get back in line. Blood sputtered from his lips whilst he tried to remain upright. I had seen men wrestling before as a sport, but never in real context of battle such as this. The brutality of the blow shocked me. To this day, I don't know how I managed to keep the need to scream within me.

Finally, we reached the main deck. Gates pointed at the highcastle, where I saw our captain speaking to a man whom I could only assume was the pirate commander. He was a fearsome sight – not very tall or burly, but the look on his face could make the Devil himself tremble under the intensity of his gaze. He compensated his lack of stature with posture, straight as a pole, as imposing as a mountain. From his waist strap, I could see two pistols glinting in the setting sun. The man was a nightmare in corporeal form, and I prayed I would never find myself the target of his cutting stare, for I was certain all my courage would unravel in seconds.

The two captains conversed calmly with one another, lending me some hope that Gates was telling the truth. They shook hands. Our captain looked resigned about the situation he found himself in, but not afraid or even worried. He delivered his sabre to his opponent as a gesture of surrender, put on his tricorn hat and abandoned the highcastle under pirate escort to join his officers in captivity.

Alone by the mizzenmast, the pirate captain looked down on his band of ragged seamen, who waited for the signal with barely contained excitement. All it took was a single nod and cheers rattled the deck from bow to stern. The pirates who weren't busy keeping the officers and crew in line scurried below, eager to get their hands on whatever treasure they could find (and they would find plenty of it, unfortunately). I glanced up to the highcastle a second time, keeping close to Mr. Gates for added safety, and to my horror found the captain's piercing eyes staring straight at me. Even from eight or so yards away, I didn't feel like I was far enough away from him. His glare gave the impression he could read my every thought.

And that was when I realized whom I was looking at. I remembered Gates' self-introduction – quartermaster of the Walrus. I knew who commanded that ship. I had heard stories about him in hushed tones in the parlours back home in England, stories most bloody and violent of a man who knew no quarter and accepted none in return. He was unmatched as a pirate, infamous for his brutality. I'd been told he had boarded a ship some years ago and murdered everyone on board, not for its riches, of which there were hardly any, nor the glory of besting a navy ship carrying a lord governor inside.

No. He had done so for no other reason than because he could. Because he wanted to.

Because he liked it.

The man I was looking at... was Captain James Flint.

“Satisfied?”

Mr. Gates' voice brought me out of my spiraling thoughts like a tribunal gavel. How could I have been so stupid? I should have realized sooner, but I was so determined to keep everyone safe that I never even made the connection. It didn't matter what I did or said to keep those women and children from harm – we had been condemned from the very start.

“That man, there.” For the first time my voice faltered, such were the tremors that overtook me. “That's captain Flint, isn't he?”

“Ah.” The smile fell from his plump, hairy cheeks. “Our reputation precedes us, I see.”

My face heated up, fists balled up against my hips. “You lied to me,” I accused. “You were never planning to let us go, were you?”

“Now, wait a minute. I know what tales you might have heard, but I swear I have every intention of honoring my pledge that you will all leave from here safe and sound.”

“And why should I trust you?” My voice toughened with outrage. “You are honorless thieves, sworn to commit every sin under Heavens for your own selfish gain. Why should I believe a single word of yours?”

“Because overtaking you down there would have been much easier than this,” he countered readily. There wasn't a hint of amusement or lightness in his black eyes anymore. He was dead serious, rather desperate even. “You must know that. You're a smart lady, clearly. Tell me, have you ever shot a pistol before? Or even held one in your hand before today?”

I ground my teeth and pulled the most fearless scowl I could, the one I had often used on my younger sisters and cousins whenever they misbehaved. It had worked on them. On a pirate who had claimed countless lives? Not so much.

“Didn't think so. So let me run a little scenario by you, see what you think: let's say you were bold enough, and stupid enough, to pull that trigger. More likely than not, you would have hit a wall instead of me or my man, Billy. At best, you could have grazed either one of us. Then I would quickly pull the still smoking gun from your hand, smacked you across the face for good measure, and locked the lot of you down there until this was all over. Now, if we were the kind of “honorless thieves” you believe we are, I could have let my men shoot every officer and seaman aboard, have the run of the ship and do what they pleased with you. But we are not that kind.” He emphasized each of those last few words like a hammer hitting a nail. “We are not in the business of terrorizing women and children and murdering indiscriminately, no matter how easy it might have been. Instead, I let you take control of the situation, even though by all rights you had none. I kept my men at bay for your comfort. I set aside my duties as quartermaster to bring you up here in the hopes of offering some relief in knowing you will all live to see another day. Why would I do that if I didn't intend to follow through on my word?”

I stared at him through narrowed eyes. I wanted to hold on to my suspicions out of self-preservation. Not doing so felt reckless. And yet... His reasoning was sound, the argument compelling. So compelling, in fact, that learning I had never actually been in control even with a pistol in my hand momentarily made my heart stop.

Yet here we were. The more I tried to search for any reason not to believe him, the more difficult it got. And either way... What else could I do? My fate and the ship's rested entirely on Mr. Gates' word of honor and captain Flint's mercy, if he had any. The terms had been set and agreed upon. What could I do in the face of such overwhelming odds? Even the knife in my pocket felt as threatening as a goose feather.

Incapable of uttering a word, I nodded in acquiescence. And so, we returned to the belly of the ship. Before I could lose sight of the highcastle, and despite how terrifying the prospect of being caught under his gaze again was, I looked up to catch one final glimpse of captain Flint – but he was no longer there.

The sacking of the HMS Delilah was fully underway. The pirates worked like ants, running up and down the decks, carrying barrels of gunpowder, pistols, chests full of coins and jewels, coils of rigging, spare wood. Basically, anything they could get their hands on. Mr. Gates had promised we would be left with enough supplies to make it to our destination, but unless he put some order into that mess, I doubted we would last a day. Pushing that preoccupation for later, I followed the quartermaster with resignation weighting heavy in my heart. Well... better resigned and alive than frightened and dead, I supposed.

We were getting to the lower deck when Gates spoke up: “You know, regardless of whether or not you stood a chance to best an entire pirate crew, you showed remarkable courage and ability to keep a cool head in the face of danger, which I don't see often in a woman. Were you a man, I would have felt tempted to offer you to join us.”

I wish those words hadn't made me swell with pride. They were coming from a pirate, a criminal, a murderer. What did it say of my character to accept validation from someone like him? But Christ forgive me if it didn't fill me with joy to hear someone praise me for my very unfeminine traits, regardless.

“Thank you,” I murmured, trying my best to mask my true feelings behind feigned disinterest. Still, a smile forced its way into my lips as I continued: “You were right about one thing, though. I never did shoot a pistol in my life. In fact, the only reason I managed to cock the hammer was because I'd seen my cousins in the military do it. I simply copied them.”

Gates laughed, a warm, pleasant sound from deep in his gut. Truthful, like him. I had to whip those thoughts back into the depths of my brain. I couldn't let my guard down. Pleasant manners or not, this man was still a pirate. Putting too much trust in him might prove unwise.

We reached the sick bay. The giant man – Billy – remained in his post, resting against the wall with his big arms crossed. He stood up straight upon our approach.

“Everything all right?” He asked.

“Everything is in order.” Mr. Gates confirmed. “Miss Constance is satisfied and ready to rejoin her friends. And here?”

“All's well. They're still inside and no one tried to stir up trouble.”

“Good!” The quartermaster turned to me. “In that case, I should be heading back. If you wish, I will leave Billy here to guard you until we're done. It shouldn't take more than a couple of hours.”

I craned my neck back to look up at Billy. He didn't seem too happy to be playing knight to us poor women; probably would prefer to be with his friends, finding his own treasure. Still, I had a feeling he would obey any order Mr. Gates left him with, regardless of whether he liked it or not.

At least we could both share the feeling of disappointed resignation.

“I would be grateful,” I told him. He nodded in agreement.

“Well, then.” Mr. Gates bowed to me and I curtsied out of habit. “Miss Constance, it was a pleasure. Until next time... Or not.”

He and Billy traded a knowing smirk before he disappeared into the lower deck above us. Billy stepped aside, allowing me a wide berth so I could knock on the door and announce myself. I heard heavy scrapping from the other side and stole a glance at our captor-turned-guard. Standing so close to him, my eyes were leveled with his chest – which I only then realized was very much nude. What I had thought was a tattered black shirt was actually more war paint, slathered from shoulder to hip, spread over a chiseled stomach that made me blush. It crossed my mind how easily it would have been for him to snap my spine in half with those big hands. About as easily as I could snap a twig. Still, as I looked upon him from head to toe, I couldn't help to feel something else stirring in me. Something not at all unpleasant, yet equally dangerous. Jesus Christ, I was lusting after a pirate. If ever had I been hell-bound, it had never been more so than in that moment.

The store room door opened a crack, filling my nostrils with the stench of sweat, rope, wood and fear, an odor strong enough to bring me back to reality. Without noticing, my breath had quickened and I felt my face hot as an oven. Fortunately, the ladies had mistaken my excitement for terror, and ushered me inside to comfort me and hear the news. I pushed any thoughts of naked chests and large hands on my body out of my mind and relayed what had happened.

***

As the hours passed, I sat in a corner and rested against an armoire full of medical supplies, trying to process everything that had transpired. I had just survived an encounter with some of the worst pirates in recent memory. Largely due to their own willingness to let us go free, sure, but even so, how many women, rich or poor, could claim the same? How many men, even? These were the monsters we had been told about as children, and yet they went to great lengths to guarantee our safety. If they were truly as evil and soulless as we had been told, why would they do everything in their power to avoid unnecessary bloodshed?

Above all, it was Mr. Gates' words that I found hardest to push from my mind. Were you a man, I would have felt tempted to offer you to join us.

Had I been a man... How many times had I wished for it? Too many to count. Had I been born a man and Gates asked me to join the Walrus, I would have said yes in a heartbeat. I wouldn't think twice about it. There would have been consequences, but at least I would be free to suffer for my choices. To live with the outcome of choices that had been made for me was much worse. I was stifled and stagnated by my life of luxury and comfort, always told what I couldn't do, never what I could. If all that awaited me in America was more conforming to expectations while I watched men do all the things I wanted to do with a look of boredom, taking it all for granted while I couldn't shoot a pistol, ride a horse or smoke a pipe, then God forgive me but I would rather take the pistol cradled once more in my hands and put it to my temple. An eternity in hell wasn't as unbearable compared to what I sailed towards.

A knock on the door brought me out of my musings. The others, who had been keeping busy by quietly conversing or lulling the children to sleep, immediately went silent and turned to me. I guess they had secretly elected me as their representative in my absence. Huzzah. I pushed to my feet and removed the one chest we had bothered to press against the door to prop it shut, for some added peace of mind. I opened just enough to see Billy on the other side.

"We're almost finished here," he informed me. "Someone will be coming down shortly to fetch you so you can go up for some fresh air."

"Very well," I mumbled. Soon enough this little adventure would be over and my nightmare would resume. "Will you be gone by then?"

"Most of us will, but we still have a few things to carry. Shouldn't take long."

That was when a very dangerous thought popped into my mind, the one that would change my life forever.

It was a terrible idea. Stupid and utterly reckless. It had no chance of success, yet I was determined to try. I would most likely die in the attempt, yet the mere thought of the potential pay-off made me feel more alive than ever before. Better to risk it all now, when I still had nothing lose.

"Thank you," I said, then shut the door. I returned to my corner next to the armoire and carefully plotted my escape into a pirate ship.

#black sails#black sails fanfic#billy bones#hal gates#james flint#stories by crow#a girl an ocean fanfic

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

21. Lords of the Sea, by Alan G Jamieson

Owned: No, library Page count: 221 My summary: The Barbary corsairs - pirates that sailed the Barbary Coast under the command of the Ottoman Empire. Not pirates of the Caribbean, but of the Mediterranean. This is their story, from their early roots to the decline of corsairing. My rating: 3/5 My commentary:

You getting sick of pirates yet? Because I'm not! While a lot of pop-cultural knowledge on pirates is based in the Caribbean during the Golden Age of piracy - specifically on the Buccaneers - other pirates are available, from other regions. The Barbary corsairs is the name for the pirates who operated in the Mediterranean, and they were just as prolific as the Buccaneers, and arguably more successful. The pirates in the story I want to write are based around Europe, so some knowledge of what was going on in a closer geographic region is definitely going to be helpful; and besides, I'm just interested in the corsairs. Like, I didn't fully know that calling them pirates is a sort of 'our-terrorists-are-your-freedom-fighters' kind of deal - most of them were more accurately privateers operating under the Ottoman Emperor. Europeans called them pirates, because that's what they were to European powers, but many were operating entirely legitimately and saw their actions as an act of war. Which is interesting! Unfortunately, this book is…not.

Look, I know I was getting in for this when I decided to read so many books about pirates, but a dull recounting of 'and then there was a sea battle, and then there was another sea battle, and then there was another sea battle' is not my idea of a good time. Honestly, though, if that was my only issue with this book I might have rated it higher, but there were a couple of things I just couldn't get past in the way it related the events. One, it kept pointing out when cities and such changed names (such as 'they went to Constantinople (modern Istanbul)') which is completely normal, but then they used the modern and older names interchangeably to the point where I gaslit myself about when they changed Constantinople's name. Why do this? There was also a lot of pointed emphasis on the corsairs who were Christian renegades (Christians who converted to Islam) as opposed to the corsairs who were originally Muslim, which I felt was pointed alongside the book's repeated emphasis on Muslim corsairs taking Christian slaves. Sure, anyone enslaving people is bad, but there was a whiff of 'well brown people enslaved white people so the Atlantic slave trade was fine actually' apologia about it. I don't necessarily think the author has those views, but it was uncomfortably reminiscent of that attitude to the point where it was noticeable.

Also, this book didn't even namecheck my girl the Sayyida al-Hurra. Zero stars.

Next…I succumb to my morbid special interests.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Underrated Pirates:

We talk a lot about the pirates of the "Golden Age"- mostly white European/colonial pirates from the early 18th century (those of the 17th Century, including the Buccaneers, are also quite well-known).

But these were not the most powerful or most successful nor, arguably, most significant pirates. They were simply the best-publicized, likely due to a mix of Eurocentric bias and their emerging at the start of the age of mass media (Steven Johnson discusses this a bit in his excellent book on Henry Every, Enemy of All Mankind).

And even within the Golden Age, the most famous names are arguably not the most significant pirates. Blackbeard is the best-known today, undoubtedly, but he was not the most successful of his time.

So let's look at some pirates who tend to fall through the cracks of popular histories.

Zheng Yi Sao. This one has been getting some more recognition lately, in part thanks to her role in season two of "Our Flag Means Death." One always has to be careful about the sources of information with piracy, where popular mythology and history tend to have blended with little distinction between them, but per Wikipedia she commanded at her height a fleet of 400 ships and 40-60,000 men and went toe-to-toe with the Chinese and Portuguese fleets, before negotiating a mass surrender to China, and dying quietly in her late 60s as the operator of a gambling house.

Hayreddin Barbarossa. A Barbary Corsair, along with his three brothers, he eventually rose to command entire fleets for the Ottoman Empire, and rule Algiers (Wikipedia).

Sinan Reis, sometimes known as "Sinan the Chief" or "Sinan the Jew," who was Hayreddin's second in command (Wikipedia). Probably history's most notable Jewish pirate, although as with Hayreddin and so many others, the line between "pirate" and "privateer" is debatable here- Europe considered him the former, but to the Ottomans he was quite legitimate.

Peter Easton. An early 17th Century English privateer/pirate involved in founding the colony of Newfoundland (making him one of the most significant pirates in Canadian history), he continued pirating after his privateering commission was canceled, leading a powerful fleet and taking Spanish treasure ships before finally swearing loyalty to the Duke of Savoy and becoming a Marquis (source: Wikipedia).

Richard (or John) Taylor. Originally part of Howell Davis's crew, he helped seize what may have been the single most valuable prize in pirate history, the Portuguese ship Nossa Snehora do Cabo, with a treasure worth one million pounds, before getting a pardon from the Spanish and retiring peacefully (Wikipedia).

William Dampier. This one is also significant not so much for his actions as a pirate, but as an author, explorer, and naturalist. He holds the distinction of being the first person to circumnavigate the world three times, the first Englishman to reach Australia, the man who helped introduce words including avocado, barbecue, and chopsticks into English (along with the first European recipe for guacamole), and a writer who's work influenced the likes of Johnathan Swift and Charles Darwin (Wikipedia). If Stede Bonnet is known as the Gentleman Pirate, Dampier undoubtedly deserves to be remembered as the Naturalist Pirate or the Scientist Pirate.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genova: Italy’s overlooked, rebellious metropolis and maritime capital.

Genova isn’t a primary destination for most visitors to Italy. On the road from Nice, it might usually be a detour on the way to Milan or Rome. So why mention this small, apparently crumbling and cramped port in any debate of Italy’s great cities? Its frescos are flaking away under the Summer Sun, and those flakes are swept away onto the Mediterranean by the cold Winter sea breeze. Genova hasn’t witnessed much renewal of late, and in many ways that’s the point. Between the splendour of Florence, and the chic of Milan, Genova is Italy’s martyr. In point of population she is the fifth city of Italy, but by a considerable margin its largest port. Genova disputes only with Marseille the primacy of the Mediterranean.

Over eight centuries, the city did more to tether the fractured Italian peninsula to the enriching trade routes of the Mediterranean and modern creative vanguards of Western Europe than any other maritime republic, even Venice. Moreover, Genova’s trading spirit, per the Belgian historian Henri Pirenne, created the antecedents of modern entrepreneurship. The small thallasocracy, crammed between a rough sea and crumbling outcrops of rock, dared to lose sight of the horizon, building early fortunes in African Coral, Byzantine Silk, and Spanish Gold.

Known as La Superba, Genova first grew to prosperity as Venice did, by ferrying knights from all over Europe to the Crusades. The Lanterna, Genova’s iconic lighthouse, has guided ships into its harbor since 1128, and above it stand the Apennine mountains. These peaks formed a fortress, barring medieval invasions from Burgundy and Savoy, shepherding the city close to the Mediterranean. Descending in steep rows, they made for the city’s majestic appearance when viewed from the sea. Flanked by forests of Cedars, Pines, and Olive trees, the French Historian and Statesman, Jules Michelet, found the terrain to be perfectly in sync with the city’s character. “These aerial terraces who strive to climb higher and higher, to see above their neighbours, are observatories from where the capitalist admires his ships.”

At closer quarters the charm admittedly dries up. The centre is noisy and crowded, flanked by abjectly unkempt suburbs. Genova would surely have expanded if not for the constraints of its harsh landscape. Named after the two-faced Roman God Janus, the misleading facade of the city derives from a period of apparent decline. The grandest palazzos are late-Renaissance and Baroque and they give the impression of a much more fortuitous history than the one Genova really enjoyed in this period. By then, the Genovese navy had enjoyed their real golden age, scoring victories against Barbary Pirates, French Corsairs, and even seizing the huge iron chains of the gates of Pisa as spoils of war in 1284.

Genova maintained its independence as a city state until 1815 (only a generation before Italy came to exist), navigating a complex political landscape dominated by larger powers and building a unique social structure centered around its merchants. Even after its incorporation into the Kingdom of Savoy, Genova retained a strong sense of regional pride and ubiquity.

Pre-eminent among its merchant families were the Dorias, who by the 16th century had become a dynasty; and it was largely due to their efforts that Genova protected its great artistic traditions into the Renaissance. The Doria Palace built in 1529 for Andrea Doria was a homage to the wealth and good taste of the republic. The city’s palaces produce a more triumphal, if less romantic, effect than the more fanciful façades of nearby Turin and Milan.

The overseer of all this grandeur was the 15th century architect Galeazzo Alessi, a disciple of Michelangelo and favourite of Andrea Doria. Most of his palaces were sadly damaged by Allied bombardments in the bid to displace Mussolini, but the peculiar Genovese building style of striped marble and pointed conical towers, are preserved in the nearby villages and towns of Liguria.

Pressed round the eastern shore of the harbour is the ancient quarter of narrow streets and lopsided houses. The numerous medieval churches; including the family church of the Dorias, San Matteo, with its exquisite cloister and Andrea Doria's tomb is adjacent to the house of Christopher Columbus, Genova’s most famous inhabitant and the personification of it’s pioneering naval spirit. Ironically, Columbus sealed the city’s fate. His discovery of the New World effectively crippled Mediterranean commerce until the opening of the Suez Canal. As Columbus set sail in 1492, the Pope banned women from entering the beautiful ivory church of Saint John (San Giovanni) on the grounds that Saint John The Baptist had been murdered by a woman, Salomé. There is no clearer proof of Italy’s devotion to the decree of Roman Catholicism than San Giovanni’s restriction of female visitors remaining in place until 1950.

This isn’t the city’s only instance of religious zeal. Like the Turin shroud, Genova hosts the relic alleged to be the cloth Joseph of Arimethea used to wipe away Jesus’s blood from the crucifix, which supposedly crystallised into an Emerald. According to Petrarch, who resided and befriended Geoffrey Chaucer in Genova, twelve knights were appointed to protect it, each for a month every year with permission to kill anyone who tried to touch it. The city is no stranger to such religious violence, Pope Urban V made the clearest statement of the Papal Schism when he had five Cardinals executed in the city for allegedly supporting the breakaway ‘Anti-Papacy’ in 12th Century Avignon.

Subsequently Genova became, like Venice, a strategic accessory of the great Imperial European powers. Its gradual decline was sharply accentuated in the eighteenth century when the once-proud city was annexed by Revolutionary France; and its fortunes reached an all time low in 1800 when Napoleon’s most dependable General, Andre Masséna, dug in for a siege against the Austrians, which enabled Napoleon to win the Marengo campaign but starved most of Genova’s inhabitants to death.

Not all the French treated Genova so contemptuously, with Gustave Flaubert writing favourably that “Genova is a beautiful town, truly beautiful. One walks on marble here, everything seems to be made of marble. The most beautiful thing I saw in Italy was Genova.” He was joined in his admiration by no less than Richard Wagner, who wrote in the 1870’s “I have never seen anything resembling Genova. It is indescribably beautiful.”

After centuries of resistance, in I814 the Genovese Republic was extinguished and the whole of Liguria was incorporated in the growing Piedmontese dominions at the Congress of Vienna. This facilitated the rejoinder of Sardinia to the House of Savoy across the Ligurian sea, and became the backbone of the Risorgimento. Yet the Genovese, like the Catalans and the Irish, never fully accepted monarchic imposition. The royal palace is ornate but uninspired compared with those in Turin and Rome. Instead Giuseppe Mazzini, the great Republican leader, garners more local reverence than the royal House of Savoy.

The old neighbourhoods have gradually been surrounded by a more modern city, with some of Europe’s oldest skyscrapers built in the 1950’s and 60’s, the direct consequence of competition from shipbuilders and industrialists who were among the wealthiest in Italy. Unlike many cities, the modern Genova does not stifle the city’s classic heart. There is no surer symbol of this juxtaposition of past and present, bound by commerce, than the Palazzo San Giorgio. With its light Austrian-inspired frescoes and crumbling roof tiles, it serves as the port headquarters and has housed Marco Polo and Napoleon as a prisoner and conqueror respectively. Even Charles V was entertained here by the Dorias on his way to sack Milan and Rome.

In a sense, Venice will always get the better of Genova, and this is Genova’s salvation. The Italian peninsula receives more than 50 million visitors a year, most of whom crowd into Venice to the horror of the locals. I have passed through Genova enough times to safely say that it bears none of the same scars of tourism. However, there is nowhere else quite like it. Nowhere else in Italy has done more to foster the Northern genius, through the settlement of Flemish Old Masters Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony Van Dyck, as well as English authors Geoffrey Chaucer and Charles Dickens. Nowhere else has exported Italian cultural so effectively through the development of capital markets. Nowhere in Italy, in my opinion, has decayed with the same dignity, retaining the reverence of a proud and legitimately independent history.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagged by @bonenest (thank you! 🫂❤️) for 9 books I'm looking forward to reading (or trying to read at least 😅) this year!

(The First Ghosts by Irving Finkel, The Sea & Civilization: A Maritime History of the World by Lincoln Paine, All The Colors of the Dark by Chris Whitaker, Show Me the Bodies: How We Let Grenfell Happen by Peter Apps, In the Walled City by Stewart O' Nan, Pirates of Barbary: Corsairs, Conquests, and Captivity in the 17th Century Mediterranean by Adrian Tinniswood, Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan's Disaster Zone by Richard Lloyd Parry, Beyond the Throne by Kristian Nairn, and All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell)

Tagging (no pressure, feel free to skip this if you want or if you were already tagged!): @willowenigma , @arsenicflame , @dianetastesmetal , @gydima , @sherlockig , @starmoonchildfromthebeamsabove , @apineappleheart , @freebooter4ever , and @bjornkram !

#text and photo post#ask box things#apologies it took me a bit to do this aksnfkgn#had to get decent screenshots of the titles and i kept forgetting one or another#then the first book in the list is one that i only found out about today which is perfect lol

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Congress of Vienna, Part 2: Slavery

Okay, so I made another post with my initial reaction to reading this article, but I missed a lot, and wanted to go back and take notes on the different areas it covered. So here are some developments on the issue of slavery according this article:

Winning the War and Losing the Peace: Spain and the Congress of Vienna, by Dan Royle

— British public was very pro abolition by 1815

— Slavery was seen by many in Spain and elsewhere as a “necessary evil” to support their economy.

— The reason the British tried to enforce abolition onto the rest of the world was not entirely due to moral reasons. It was also because they knew it would be harder for British goods to complete with countries which were selling goods without having to pay for labor. So it was in British interests to make the rest of the world abolish slavery at the exact same time they did.

— Though many in Spain were “economic realists” when it came to slavery, one notable exception includes José Miguel Guridi y Alcocer, who made a petition to ban it in 1811.

— Augustín Argüelles was another abolitionist, but he didn’t like the idea of the British forcing them and wanted Spain to be doing it on its own terms.

— 24 August 1814: King Ferdinand VII signed an addition to the treaty of friendship with Britain, which was to acknowledge the ‘injustice and inhumanity’ of the slave trade.

— Overall, Spain was pretty uncomfortable with being forced to implement a policy by a foreign country, so Castlereagh, the British plenipotentiary, dropped the subject until later.

— Many in Spanish America, notably Cuba, strongly objected to abolition. This deeply worried the Spanish plenipotentiary to the congress, Pedro Gómez Labrador.

— Spain actually had fewer slaves than Britain at that time.

— October 1814: rule to limit slavery to only the region south of the equator and 10 degrees north. I’m not sure what the reason was for that seemingly arbitrary line on a map. I think it was meant to be a compromise.

— William Wilberforce wanted abolition immediately.

— Castlereagh offered the Duke of San Carlos 10 million Spanish dollars to end the slave trade, but nothing happened.

— Unlike the British, the French public was “vehemently opposed” to immediate abolition.

— Napoleon as emperor had abolished the slave trade in France anyway.

— So coming off of that, Talleyrand decided to help Castlereagh put pressure on Spain to do the same.

— Some were concerned that the Congress of Vienna was not addressing enslavement of Europeans happening in the Mediterranean by Barbary Corsairs.

— The main reason why it wasn’t being addressed was because the Barbary issue had declined a lot, though still important. It mostly effected the Mediterranean countries.

— Which is kind of interesting since Britain was actually the dominant naval power in the Mediterranean by that time.

— Labrador tried to get Johann Friedrich Hach’s pamphlet about Barbary slavery translated into English. Hach was the representative of the Hanseatic city of Lübeck.

— Piedmont-Sardinia, another Mediterranean country, made an official declaration against Barbary slavery at the congress.

— The Congress of Vienna representatives officially signed a declaration against the slave trade. But the countries disagreed on the timetable to officially implement its abolition.

— Castlereagh thought the issue of slavery was less significant than the reason the Congress of Vienna had been organized in the first place (which was to restructure Europe post-Napoleon), but made it a priority due to public demand in Britain.

— Metternich feared that the issue of abolition could lead to war.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week's map update is a three masted lateen-rigged warship based on a xebec, a vessel popular with the pirates of the Barbary States and other Mediterranean navies. Fast, maneuverable, and armed with fourteen guns, this corsair would be suitable to serve as both an enemy warship or as an adventuring party's vessel in a nautical campaign. She is not intended or designed for long voyages however, as space onboard is quite cramped and unpleasant (though navigating that morale hazard could be a fun challenge for party and DM). As always, Patreon supporters have access to the full size PNG/VTT files without watermark, and in grid/gridless + night/day variants. I've also included description of a sample ship in PDF, as well as a transparent background version for those who would like to convert the file into an object and overlay it on their own Roll20/VTT backgrounds, or to simply make navigating between layers easier.

#D&D#dungeons & dragons#ttrpg#dnd maps#battle maps#roll20#dungeondraft#pirate#nautical#age of sail#DM resource#Tellus

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

So in my under the weather mind, I had an idea of a few variations where once being discovered for who he really was, Francis dissappears to life at sea as a privateer what eventually turns into a notorious captain of The Barbary pirates coining himself the name Black King of the Ottoman corsairs striking terror in the coasts of Europe, North Africa all the way to Tripoli. (Somehow my characters always turn to piracy at some point in any fandom, I swear 🤣 Francis just would look nice as a pirate lord OKAY)

Years later, one of his fleet strikes raids through London's Thames again, yet this time worse in retaliation to EITC taking down some of their ships. They're busting down business, taking whatever isn't nailed down and setting the rest to burn whilst battling the royal forces. Eb makes sure he's out in the midst of it this time to try and find Francis and asks if they know Osman, he knows him and he wants to convene with him. Securing his idea of meeting with what he thinks is a guarantee by quoting parlay(Eb you poor idiot, stop mixing your adventure novels with real life).

Which they would delightfully sneer in entertainment. "Oh he doesn't go by that name anymore but we know who you are, he bloody hates you- but we'll gladly take you to him." He gets taken prisoner but they do leave after that and will take him to Francis main vessel in eager hopes of a bounty of their lord's worst kept secret fixation of spiteful vindication.

Francis at this point is madly hostile and ever bit his reputation over Eb not leaving with him years ago so this could go one of two ways. What Eb knows but doesn't care for Eb himself has repined in regret for not leaving from having been afraid to. He feels responsible for turning Francis into the terror he's become and just wants to stop the violence he caused, to apologize and confess then let whatever be may. At least he got it off his chest and said his peace.

Friend after telling them this: Hey have you watched Our Flag Means Death?

Me: No... It's that pirate series right? I haven't heard much about it but I do love pirates. Is it a new show?

Friend: Yeah... you should... You basically described it. It's two middle aged men down bad for each other and goes horribly because one wouldn't accept his feelings leaving the other to brood in a emo, angsty mess of violent rage. They act like a rogue version of your Francis and Scrooge. They're about to come out with a second season.

Me: O^O ...Why am I always the outler to hear about good shows, what the hell? I didn't know it was about two men that need to just smash each other! That's made for me!

@rom-e-o thought you might find this amusing. My mind is a circus sometimes. I don't see myself writing this but definitely would enjoy some pirate style artwork for it.

#I could see Eb sitting there blindfolded#fully prepared to be blown to smithereens.#He's kept in that suspense as he says his peace then just snatched at the waist and taken to his quarters.#fun fact alot of lgbt folks became pirates back then to live freely outside of religious tyranny.#I don't see myself writing this but its a fun concept 😅#scroogeposting#oc francis osman#pirate francis

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

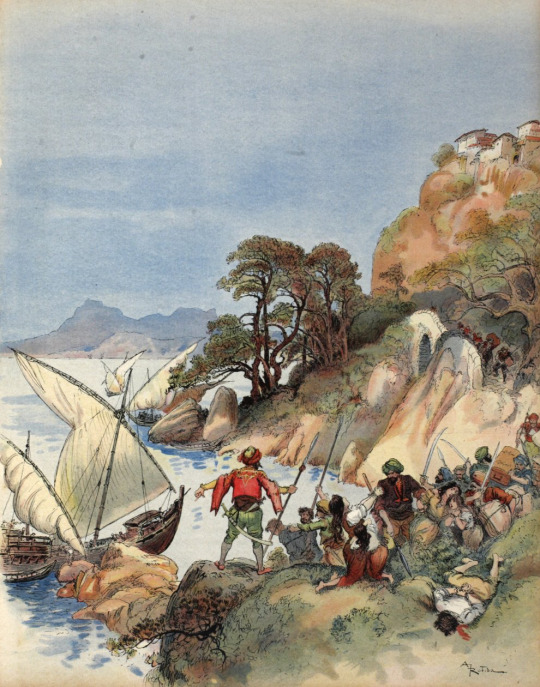

Barbary pirates terrorising the coast of the Mediterranean, kidnapping the inhabitants to sell as slaves

by Albert Robida

#barbary pirates#mediterranean#art#albert robida#pirates#pirate#europe#southern europe#barbary coast#north africa#history#european#north african#berber#berbers#muslim#muslims#islam#islamic#corsair#corsairs#ottoman#ottomans#ottoman empire#illustration#georges g toudouze#georges gustave toudouze#christians#christian

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

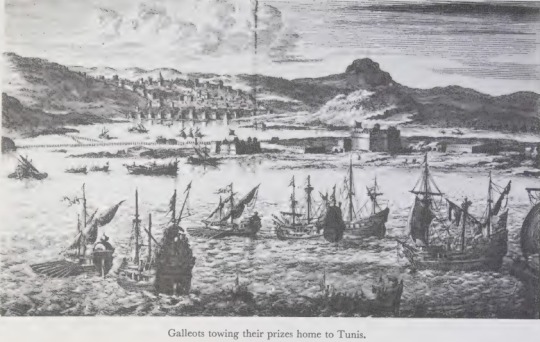

Corsairs of Barbary: Dividing the Loot

"Apart from searching the passengers and crew, the captain and the purser (khodja) were always quick to get hold of the ship’s books and to seal the cargo in order to prevent their men from sacking that as well. But on the score of pillaging captured ships the Barbary corsairs had a better reputation than most privateers of the period.

It was the universal custom of corsairs that certain goods such as the possessions of captured sailors and passengers should be the personal reward of those who captured them. Other goods such as any cargo below deck and the contents of the captain’s cabin were reserved either for the general share-out or for particular persons who had customary rights to them.

The normal practice of the Barbary corsairs was to pile goods that were destined for the general share-out around the mast. Many writers were surprised at the high standard of honesty shown in doing this. D’Arvieux went as far as to say that the Barbary corsairs did not pillage at all. This seems rather unlikely though the punishments for the individual found defrauding his mates were characteristically savage. None the less the general behaviour of the corsairs when capturing a ship was very much better than that of their Maltese rivals, and incomparably better than that of a contemporary English privateer.

The strong discipline of the janissaries and the scrupulously fair division of booty in the Barbary ports were the main reasons for this. D’Arvieux writes: "It is surprising that people as brutal and barbarous as the Algerians can keep so much order and justice as they do in their brigandage. One never sees the least difficulty amongst them over the division of the booty"."

— Peter Earle, Corsairs of Malta and Barbary (1970)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Europeans were also enslaved by North Africans, you mean white slaves?

Europeans were also enslaved by North Africans, you mean white slaves? Sounds like Africa snatched up whatever they thought they could sell, especially Christians. WAIT! Does Africa owe me Reparations?

The coasts of Valencia, Andalusia, Calabria and Sicily were so often raided that “there was no one left to capture”. Historians estimate as high as 1,250,000 captives were enslaved from 1530 - 1780. Was the Northern part of Africa built on the backs of white, European, Christians? Maybe it’s time to “rethink our belief that race was fundamental to pre-modern ideas” of slavery.

Direct Quotes:

The fishermen and coastal dwellers of 17th-century Britain lived in terror of being kidnapped by pirates and sold into slavery in North Africa. Hundreds of thousands across Europe met wretched deaths on the Barbary Coast in this way.

In the first half of the 1600s, Barbary corsairs - pirates from the Barbary Coast of North Africa, authorised by their governments to attack the shipping of Christian countries - ranged all around Britain's shores.

Admiralty records show that during this time the corsairs plundered British shipping pretty much at will, taking no fewer than 466 vessels between 1609 and 1616, and 27 more vessels from near Plymouth in 1625.

Considering what the number of sailors who were taken with each ship was likely to have been, these examples translate into a probable 7,000 to 9,000 able-bodied British men and women taken into slavery in those years.

Not content with attacking ships and sailors, the corsairs also sometimes raided coastal settlements, generally running their craft onto unguarded beaches, and creeping up on villages in the dark to snatch their victims and retreat before the alarm could be sounded. Almost all the inhabitants of the village of Baltimore, in Ireland, were taken in this way in 1631

how they eat nothing but bread and water.... How they are beat upon the soles of the feet and bellies at the Liberty of their Padron. How they are all night called into their master's Bagnard, and there they lie.'

According to observers of the late 1500s and early 1600s, there were around 35,000 European Christian slaves held throughout this time on the Barbary Coast - many in Tripoli, Tunis, and various Moroccan towns, but most of all in Algiers.

The unfortunate southerners were sometimes taken by the thousands, by slavers who raided the coasts of Valencia, Andalusia, Calabria and Sicily so often that eventually it was said that 'there was no one left to capture any longer'.

On this basis it is thought that around 8,500 new slaves were needed annually to replenish numbers - about 850,000 captives over the century from 1580 to 1680.

for the 250 years between 1530 and 1780, the figure could easily have been as high as 1,250,000 - this is only just over a tenth of the Africans taken as slaves to the Americas from 1500 to 1800, but a considerable figure nevertheless. White slaves in Barbary were generally from impoverished families, and had almost as little hope of buying back their freedom as the Africans taken to the Americas: most would end their days as slaves in North Africa, dying of starvation, disease, or maltreatment.

Slaves in Barbary fell into two broad categories. The 'public slaves' belonged to the ruling pasha, who by right of rulership could claim an eighth of all Christians captured by the corsairs

These slaves were housed in large prisons known as baños (baths), often in wretchedly overcrowded conditions. They were mostly used to row the corsair galleys in the pursuit of loot (and more slaves) - work so strenuous that thousands died or went mad while chained to the oar.

During the winter these galeotti worked on state projects - quarrying stone, building walls or harbour facilities, felling timber and constructing new galleys. Each day they would be given perhaps two or three loaves of black bread - 'that the dogs themselves wouldn't eat' - and limited water; they received one change of clothing every year. Those who collapsed on the job from exhaustion or malnutrition were typically beaten until they got up and went back to work.

selling water or other goods around town on his (or her) owner's behalf. They were expected to pay a proportion of their earnings to their owner - those who failed to raise the required amount typically being beaten to encourage them to work harder.

As they aged or their owner's fortunes changed, slaves were resold, often repeatedly. The most unlucky ended up stuck and forgotten out in the desert, in some sleepy town such as Suez, or in the Turkish sultan's galleys, where some slaves rowed for decades without ever setting foot on shore.

Many slaves converted to Islam, though, as Morgan put it, this only meant they were 'freed from the Oar, tho' not from [their] Patron's Service.' Christian women who had been taken into the pasha's harem often 'turned Turk' to stay with their children, who were raised as Muslims.

Slaves in Barbary could be black, brown or white, Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, Jewish or Muslim. Contemporaries were too aware of the sort of people enslaved in North Africa to believe, as many do today, that slavery, whether in Barbary or the Americas, was a matter of race. In the 1600s, no one's racial background or religion automatically destined him or her for enslavement. Preachers in churches from Sicily to Boston spoke of the similar fates of black slaves on American plantations and white slaves in corsair galleys; early abolitionists used Barbary slavery as a way to attack the universal degradation of slavery in all its forms.

This may require that we rethink our belief that race was fundamental to pre-modern ideas about slavery. It also requires a new awareness of the impact of slave raids on Spain and Italy - and Britain - about which we currently know rather less than we do about slaving activities at the same time in Africa. The widespread depopulation of coastal areas from Malaga to Venice, the impoverishment caused by the kidnapping of many breadwinners, the millions paid by the already poor inhabitants of villages and towns to get their own people back - all this is only just beginning to be understood by modern-day historians.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Arab Slave Trade. The Arab slave trade was the practice of slavery in the Arab world, mainly in Western Asia, North Africa, East Africa, and certain parts of Europe (such as Iberia and Sicily) during their period of domination by Arab leaders. The trade was focused on the slave markets of the Middle East, North Africa and the Horn of Africa. People traded were not limited to a certain race, ethnicity, or religion, and included Turks, Iranians, Europeans, and Berbers, especially during the trade’s early days. During the 8th and 9th centuries of the Fatimid Caliphate, most of the slaves were Europeans (called Saqaliba) captured along European coasts and during wars. However, slaves were drawn from a wide variety of regions and included Mediterranean peoples, Persians, peoples from the Caucasus mountain regions (such as Georgia, Armenia and Circassia) and parts of Central Asia and Scandinavia, English, Dutch and Irish, Berbers from North Africa, and various other peoples of varied origins as well as those of African origins. Toward the 18th and 19th centuries, the flow of Zanj (Bantu) slaves from East Africa increased with the rise of the Oman Sultanate based in Zanzibar. They entered trade conflict and competition with Portuguese and other Europeans along the Swahili coast. The North African Barbary states carried on piracy against European shipping and enslaved thousands of European Christians. They earned revenues from the ransoms charged; in many cases in Britain, village churches and communities would raise money for such ransoms. The government did not ransom its citizens. SCOPE OF THE TRADE Historians estimate that between 650 and 1900, 10 to 18 million people were enslaved by Arab slave traders and taken from Africa across the Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Sahara desert. The term Arab when used in historical documents often represented an ethnic term, as many of the “Arab” slave traders, such as Tippu Tip and others, were physically indistinguishable from the “Africans” they enslaved and sold. Due to the nature of the Arab slave trade, it is impossible to be precise about actual numbers. To a smaller degree, Arabs also enslaved Europeans. According to Robert Davis, between 1 million and 1.25 million Europeans were captured between the 16th and 19th centuries by Barbary corsairs, who were vassals of the Ottoman Empire and sold as slaves. These slaves were captured mainly from seaside villages in Italy, Spain, and Portugal and also from more distant places like France or England, the Netherlands, Ireland and even Iceland. They were also taken from ships stopped by the pirates. The effects of these attacks were devastating: France, England, and Spain each lost thousands of ships. Long stretches of the Spanish and Italian coasts were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants, because of frequent pirate attacks. Pirate raids discouraged settlement along the coast until the 19th century. Periodic Arab raiding expeditions were sent from Islamic Iberia to ravage the Christian Iberian kingdoms, bringing back booty and slaves. In a raid against Lisbon in 1189, for example, the Almohad caliph, Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur, took 3,000 female and child captives, while his governor of Córdoba, in a subsequent attack upon slives in 1191, took 3,000 Christian slaves. The Ottoman wars in Europe and Tatar raids brought large numbers of European Christian slaves into the Muslim world too. From a Western point of view, the subject merges with the Oriental slave trade, which followed two main routes in the Middle Ages:……….. #Africa

2 notes

·

View notes