#Avenue Franklin Roosevelt

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Avenue Franklin Roosevelt, Vincennes, France

Robin Ooode

0 notes

Text

These folks look suitably grim as they listen to the election returns at the temporary "wigwam" in the 7th Avenue Armory on November 6, 1928. Governor Alfred E. Smith, the Democratic candidate for president, is seated in the second row, third from the left. He lost to Herbert Hoover by 17 percentage points. Franklin D. Roosevelt, the (successful) candidate to succeed Smith as New York governor, is in the first row, third from the left.

Photo: Associated Press

#vintage New York#1920s#1928 election#Alfred E. Smith#Al Smith#election night#FDR#Franklin D. Roosevelt#Nov. 6#6 Nov.#election returns#1920s New York

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Église Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, Marseille, France: The Église Saint-Vincent-de-Paul is a Roman Catholic church in Marseille, France. It is located off the top of the Canebière, in the Thiers district. The exact address is 2-3 Cours Franklin Roosevelt, an avenue named for American President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945). Wikipedia

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Architecte Adrien Blomme (1878-1940) Avenue Franklin Roosevelt, Bruxelles, Belgique 1928. - source Thierry Bernard.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Detroit Riot of 1943 lasted only about 24 hours from 10:30 on June 20 to 11:00 p.m. on June 21, it was considered one of the worst riots during the WWII era. Several contributing factors revolved around police brutality and the sudden influx of African Americans from the South, lured by the promise of jobs in defense plants. They faced an acute housing shortage that many thought would be reduced by the construction of public housing. The construction of public housing for African Americans in predominately white neighborhoods often created racial tension.

The Sojourner Truth Homes Riot in 1942, began when whites were enraged by the opening of that project in their neighborhood. Mobs attempted to keep the African American residents from moving into their new homes. That confrontation laid the foundation for the much larger riot one year later.

On June 20, a fistfight broke out between an African American man and a white man at the sprawling Belle Isle Amusement Park. The brawl grew into a confrontation between groups of African Americans and whites and then spilled into the city. Stores were looted, and buildings were burned in the riot, most of which were located in an African American neighborhood.

Both groups engaged in violence. Whites were dragged out of cars and looted white-owned stores in Paradise Valley while whites overturned and burned African American-owned vehicles and attacked African Americans on streetcars along Woodward Avenue and other major streets. The Detroit police did little in the rioting.

The violence ended only after President Franklin Roosevelt, at the request of Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries, Jr., ordered 6,000 federal troops into the city. Twenty-five African Americans and nine whites were killed in the violence. Of the 25 African Americans who died, 17 were killed by the police. The police claimed that these shootings were justified since the victims were engaged in looting stores on Hastings Street. Of the nine whites who died, none were killed by the police. The city suffered an estimated $2 million in property damages. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 years ago I was in my flat living in Paris on the champs Elysée ...

That day will remain a remembering day !

I had a business lunch at le chat blanc located on 61 avenue Franklin Delano Roosevelt 75008 where I have been most probably drugged by someone in the table around or at my table !

Right after the lunch I felt like open to everything ... this will make sense... in the afternoon. My flat was located very close to this restaurant ! Right after the lunch I came back home and left again to do some grocery shopping. That is when hell fell out on me... an unknown man in the street came to me and started talking about my life like he knew everything ... (very well organized) and talked about me beeing in danger ! I could not resist the talk because of what I had eaten ... he quickly manage to gain confidence with me because of the drug and the knowledge he had on me ... He gave me something to look at in a very carefull way that I recall ! That came in contact with my skin ...

Then the person left ...

Within 24 Hours very bad symptoms started to appear.

This is my story and I will provide descriptions and informations.

For those willing to read I will provide help on how to protect your self or detect bad behave ! I did study a lot my story to understand how those people did manage to kill my life in a way no one can imagine (Following, hacking, poisonning..)

This took me 2 years to understand what happen to me and I am still victims of oppressions from X.

#poisonous#champs elysees#sex and drugs#fight back#self defense#god of destruction#anonymous#hacks#possession

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"David Dellinger and his friend Don Benedict caught a ride from New York to Washington, D.C., for the Lincoln’s Birthday weekend of 1940. Who knows where they stayed—on somebody’s floor, probably. It was the Depression, and Dellinger in particular knew all about roughing it. Benedict was hoping to learn from him on that score. They were in Washington because the two of them were part of a youth movement whose eager vanguard had descended on the city to agitate for jobs, rights, peace, and what they saw as justice. Both had backgrounds in the important Christian student movement of the era, Dellinger at Yale and Benedict at Albion, a little Methodist college in Michigan, and both now were graduate students at Union Theological Seminary in New York. There Dellinger had quickly formed a close bond with Benedict and Meredith Dallas, also from Albion. Pacifism, like socialism, was in the air at Union, at least among students.

Members of the American Youth Congress parade in gas masks on Fifth Avenue in New York City February 6, 1940 protesting impending war and publicizing the upcoming youth pilgrimage to Washington, D.C. Acme News Service. Washington Spark Flickr.

It was an exciting time, even if, like W. H. Auden, America’s young, having lived through “a low dishonest decade,” could feel the

Waves of anger and fear Circulate over the bright And darkened lands of the earth, Obsessing our private lives[.]

The students who made their way to Washington that weekend had come of age in the Great Depression. America’s collegians, once apathetic, were now far more conscious of injustice, chafing under the political constraints imposed by paternalistic faculty and administrators—and determined to stay out of war. “It was a time when frats, like the football team, were losing their glamor,” wrote the playwright Arthur Miller, recalling his days at the University of Michigan (Class of 1938):

Instead my generation thirsted for another kind of action, and we took great pleasure in the sit-down strikes that burst loose in Flint and Detroit…We saw a new world coming every third morning.

Many such Americans worried that war would undo whatever progress had been made by the New Deal, while undermining civil liberties. Stuart Chase, a popular economics writer and FDR associate whose 1932 book, A New Deal, provided ideas and a name for the White House program, argued that by avoiding war we might achieve

the abolition of poverty, unprecedented improvements in health and energy, a towering renaissance in the arts, an architecture and an engineering to challenge the gods.

But if war were to come, he wrote, we would see

the liquidation of political democracy, of Congress, the Supreme Court, private enterprise, the banks, free press and free speech; the persecution of German-Americans and Italian-Americans, witch hunts, forced labor, fixed prices, rationing, astronomical debts, and the rest.

Delegates to the American Youth Congress march from the U.S. Capitol to the White House Feb 9, 1940 where they were addressed by President Franklin Roosevelt. International News Photo, Washington Area Spark Flickr.

If Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal didn’t go far enough, it had at least offered hope. But in foreign affairs even this scant comfort was absent. During the thirties students had seen the rise of Hitler, the fascist triumph in the Spanish Civil War, and a series of futile appeasement measures culminating in the Nazi invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, which triggered war with Britain and France. As Dellinger, Benedict, and thousands like them arrived in Washington, tiny Finland was still fighting with unexpected ferocity to repel an invasion by the Soviet Union, which had cynically agreed with Germany to divide Europe between them. The Red Army even joined in the dismembering of Poland. On the other side of the world, China had been struggling since 1937 against a brutal Japanese invasion.

Hope springs eternal, but on the morning of Saturday, February 10, 1940, even the nasty weather augured ill. Washington was rainy and cold as a young woman on horseback—dressed as Joan of Arc—led a procession of idealistic young Americans along Constitution Avenue. Many were in fanciful costumes. The rich array included some in chain mail and others dressed as Puritans. A delegation from Kentucky rode mules. Signs and banners held aloft by the students that weekend bore antiwar slogans, including, loans for farms, not arms; jobs not guns; and, in sardonic reference to the discredited crusade of the Great War, the yanks are not coming.

The context of their march was the national struggle over what role America should play in the European war—a war that had happened despite the best efforts of well-meaning people the world over to avoid it by means of rhetoric, law, arms control, appeasement, and every other method short of actually fighting about it. Now that it was at hand, America’s young were far more opposed to intervention than their elders, and this was a source of conflict on campus. At Harvard’s graduation a few months later, class orator Tudor Gardiner reflected the attitudes of many students in calling aid for the Allies “fantastic nonsense” and urging a focus on “making this hemisphere impregnable.” When Gardiner’s predecessor by twenty-five years recalled, at a reunion event, that “We were not too proud to fight then and we are not too proud to fight now,” recent graduates booed. But when commencement speaker Cordell Hull, FDR’s secretary of state, called isolationism “dangerous folly,” Harvard president James Bryant Conant nodded in support. Scenes like this would play out at campuses all across the country.

Delegates to the American Youth Congress with the U.S. Capitol in the background Feb 9, 1940 call for more jobs not war. The image is an undated Harris & Ewing photograph from the Library of Congress.

The students who converged on Washington for the Lincoln’s Birthday weekend brought with them their generation’s disdain for war. Marching in a steady drizzle, they were bound, these tender youths, for the White House, to which they had foolishly been invited by Eleanor Roosevelt—herself an active pacifist during the interwar years. “Almost six thousand young people marched,” her biographer reports, “farmers and sharecroppers, workers and musicians, from high schools and colleges, black and white, Indians and Latinos, Christians and Jews, atheists and agnostics, freethinkers and dreamers, liberals and Communists.”

Dellinger and Benedict were part of this “extraordinary patchwork,” the two seminarians having made the trip from New York by car with some other young people. Dellinger in particular was already being noticed, as he always seemed to be. Years later he would recall (clearly as part of this weekend) being invited by the First Lady to a White House tea in early 1940 with other student leaders who had, as he put it, organized a protest that she supported. Benedict’s memoir recalls that the two of them went to Washington that same month and attended “a huge rally, with thousands massed around the White House” to hear remarks by the president and the First Lady. “Dave and I talked a lot about demonstrating,” Benedict writes, adding: “Both of us knew the value of drama.”

...

For the White House, it made sense to pay attention to the young, many of whom would be just old enough to vote in the upcoming presidential election. Before the Depression, college students were solidly Republican, but as the thirties wore on and their social consciousness expanded, they swung increasingly to Roosevelt’s Democrats. The AYC [American Youth Congress] was both a cause and effect of this change and enjoyed the warm support of Eleanor Roosevelt, who over the several years of its existence had raised money for it, defended it in her newspaper columns, procured access to important public figures, and even scheduled face time with the president. For the big weekend event she had gone all out, prevailing on officials, hostesses, and her husband to accommodate the anticipated five thousand young people in every possible way. An army colonel named George S. Patton housed a bunch of the boys in a riding facility the First Lady had recently visited. She lined up buses; helped with costumes and flags, meals and teas; and arranged at least one of the latter at the White House—consistent with Dellinger’s recollection.

The event in Washington was billed as “a monster lobby for jobs, peace, civil liberties, education and health,” but it turned out to be the Götterdämmerung for the youth congress, and a landmark in the decline of America’s vigorous interwar peace movement. Nothing could more effectively symbolize the movement’s tender idealism, fair-weather pacifism, and ecclesiastical aura than an American college student dressed as the Maid of Orleans—a sainted military hero—on horseback, just months before France itself fell to an onslaught of modern mechanized warfare. Of course the American Joan of Arc, whoever she was, can be read as a symbol of hope for France because, in fact, the Yanks were coming, even if most of them didn’t know it yet. On the other hand, hopes for peace were starting to look more like delusions, even to those who held them, and here the symbolism becomes even richer, for Joan embodies three powerful drivers of the era’s American peace movement: She is young, she is female, and she is religious.

A few of the 3,000 youth that arrived for the opening of the three day American Youth Congress February 9, 1940 that will lobby Congress for passage of a youth bill to provide education and jobs. Washington Area Spark Flickr.

Many of these activists regarded abolitionism as the forerunner of their reformist enterprise, so it was fitting that here they were, in 1940, rallying for righteous change on the weekend of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. By now the students have reached the White House, arriving an hour early to hear the president. They had to leave their banners and placards outside the gates, where the guards on duty counted 4,466 gaining admission to the South Lawn—no doubt including Dellinger and Benedict. They grew colder and wetter as they waited.

After a while the American Youth Congress’s national chairman, Jack McMichael, a southern divinity student who had earlier spoken out against the violent abuse and disenfranchisement of blacks, took the microphone on the South Portico and led the students in singing “America the Beautiful.” And then, at long last, he introduced the president, describing our troubled country as a place where Americans dream of “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” but face the threat of bloodshed.

Now war, which brings nothing but death and degradation to youth and profit and power to a few, reaches out for us. Are we to solve our youth problem by dressing it in uniform and shooting it full of holes? America should welcome and should not fear a young generation aware of its own problems, active in advancing the interests of the entire nation…They are here to discuss their problems and to tell you, Mr. President, and the Congress, their needs and desires…I am happy to present to you, Mr. President, these American youth.

When FDR finally appeared, looking out with Eleanor over a sodden crowd dotted with umbrellas, he wore a strange smile—and gave them a blistering earful, dismissing as “unadulterated twaddle” their concerns about Finland and warning them against meddling in subjects “which you have not thought through and on which you cannot possibly have complete knowledge.” Concerning their cherished Soviet Union, FDR said that in whatever hopes the Soviet “experiment” had begun, today it was “a dictatorship as absolute as any other dictatorship in the world.” It was a shocking public rebuke to the students as well as the First Lady. The young compounded the fiasco by booing and hissing, creating a public relations nightmare in a nation that took a dim view of such a response to the president. Later that afternoon the First Lady had to sit still at an Institute plenary session, calming herself by knitting, while the fiery antiinterventionist John L. Lewis pandered to his student audience by heaping abuse on FDR. He would support Willkie in the coming election.

Besides Dellinger, other future activists who stood in the rain for Roosevelt’s “spanking,” as some newspapers called it, included future Representative Bella Abzug of New York and the writer Joseph Lash, who would win the Pulitzer Prize for his biography of Eleanor Roosevelt and help found with her (and Niebuhr) the liberal but anti-communist Americans for Democratic Action. Woody Guthrie was on hand, too, to write the student movement’s requiem. The folk singer, not yet a celebrity, arrived by riding the rails from Texas. Stunned by the president’s public scolding of the idealistic youngsters, Guthrie wrote a song on the spot entitled, “Why Do You Stand There in the Rain?”

It was raining mighty hard in that old Capitol yard When the young folks gathered at the White House gate. … While they butcher and they kill, Uncle Sam foots the bill With his own dear children standing in the rain.

Without money, Dellinger and Benedict made like Guthrie by riding the rails to get home—a first for Benedict but something Dellinger had been doing on and off for several years. After the excitement of the weekend they entered the railyard in darkness, careful to elude watchmen, and hunted for a train heading north. When they found one, they couldn’t gain access to any of the boxcars, but finally climbed aboard an open coal car, the freezing wind whipping them as they picked up speed, the air thick with choking dust and smoke. Miserable as it was, they were moving too fast to get off. It was an omen, perhaps, of the nature of their journey to come.

- Daniel Akst, War By Other Means: How the Pacifists of World War 2 Changed America for Good. New York: Melville House, 2022. p. 4-6, 7-8, 17-19.

#washington dc#peace march#youth rally#white house#fdr#american youth congress#youth movement#pacifism#world war ii#united states history#the great depression#new deal#research quote#reading 2024

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The American Negro Exposition of 1940, took place at the Chicago Coliseum at Wabash Avenue and 15th Street. The event only ran for two months, but took years to plan.

The exposition received the endorsement of officials ranging from the mayor of Chicago, all the way up to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The event was organized in Chicago, with real estate businessman James W. Washington as founder and president. Washington was said to have traveled more than 135,000 miles over five years to secure endorsements.

He successfully lobbied the Illinois legislature to appropriate $75,000, equivalent to $1.4 million dollars today, for the project. Soon after the funds were matched by Congress.

The expo was hoping to draw 2 million people in attendance to celebrate the contributions of Blacks to America since emancipation which had taken place 75 years earlier.

#chicago#Black History#AMERICAN NEGRO EXPOSITION 1940#American Negro Exposition of 1940#James W Washington#Youtube

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A P-38 Pilot Describes the Attack on Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

P-38 pilot Roger Ames participated in the shooting down of Japan’s most important admiral.

This article appears in: Fall 2012

By Robert F. Dorr

When American air ace Major John Mitchell led 16 Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters on the longest combat mission yet flown (420 miles) on April 18, 1943, Mitchell’s target was Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese admiral considered the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Mitchell’s P-38 pilots, using secrets from broken Japanese codes, were going after Yamamoto, the poker-playing, Harvard-educated naval genius of Japan’s war effort. Mitchell’s P-38s intercepted and shot down the Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber carrying Yamamoto. After the admiral’s death, Japan never again won a major battle in the Pacific War.

No band of brothers ever worked together better than the men who planned, supported, and flew the Yamamoto mission. Yet, after the war, veterans fell to bickering over which P-38 pilot actually pulled the trigger on Yamamoto.

There was one thing they never disagreed on. Like most young pilots of their era, they believed the P-38 Lightning was the greatest fighter of its time.

Roger J. Ames (1919-2000) flew the Yamamoto mission. This first-person account by Ames was recorded by the author in 1998 and appeared in his 2007 book, Air Combat: A History of Fighter Pilots; it has never before appeared in a magazine.

Intercepting a Crucial Japanese Radio Message

The downing of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto is arguably the most studied fighter engagement of the Pacific War. Yamamoto, 56, was commander in chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet and the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack. He called himself the sword of Japan’s Emperor Hirohito. He claimed he was going to ride down Pennsylvania Avenue on a white horse and dictate the surrender of the United States in the White House.

Yamamoto studied at Harvard (1919-1921), traveled around America, was twice naval attaché in Washington, D.C., and understood as much about the United States, including U.S. industrial power, as any Japanese leader. In April 1943, Yamamoto was trying to prevent the Allies from taking the offensive in the South Pacific and was visiting Japanese troops in the Bougainville area.

On the afternoon of April 17, 1943, Major John Mitchell, commander of the 339th Fighter Squadron, was ordered to report to our operations dugout at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. The 1st Marine Division had captured the nearly completed field the previous summer and named it for Major Lofton Henderson, the first Marine pilot killed in action in World War II when his squadron engaged the Japanese fleet that was attacking Midway.

Now Mitchell found himself surrounded by high-ranking officers. They told him the United States had broken the Japanese code and had intercepted a radio message advising Japanese units in the area that Yamamoto was going on an inspection trip of the Bougainville area.

The message gave Yamamoto’s exact itinerary and pointed out that the admiral was most punctual. They told Mitchell that Frank Knox, secretary of the Navy, had held a midnight meeting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt regarding the intercepted message. It was decided that we would try to get Yamamoto if we could. The report of the meeting was probably inaccurate because Roosevelt was on a rail trip away from Washington, but the plan to get Yamamoto unquestionably began at the top.

Eighteen P-38s Selected For the Mission

The Navy would never have admitted it, but the Army’s P-38 was the only fighter with the range to make the approximately 1,100-mile round trip. We were under the command of the Navy at Guadalcanal, so you can bet they’d have taken the job if they were able.

First Lieutenant Rex T. Barber, one of two Americans originally credited with shooting down Yamamoto. He later was given sole credit for the kill.

According to the intercepted message, Yamamoto and his senior officers were arriving at the tiny island of Ballale just off the coast of Bougainville at 9:45 the next morning. The message said that Yamamoto and his staff would be flying in Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers, escorted by six Zeros. The Yamamoto trip was to include a visit to Shortland Island and Bougainville.

Mitchell was to be mission commander of 18 P-38s that would intercept, attack, and destroy the bombers. That’s all the P-38s we had in commission.

The Plan of Attack

Led by Mitchell, we planned the flight in excruciating detail. Nothing was left to chance. Yamamoto was to be at the Ballale airstrip just off Bougainville at 9:45 the next morning and we planned to intercept him 10 minutes earlier about 30 miles out. To ensure complete surprise, we planned a low level, circuitous route staying below the horizon from the islands we had to bypass, because the Japanese had radar and coastwatchers just as we did.

We plotted the course and timed it so that the interception would take place upon the approach of the P-38s to the southwestern coast of Bougainville at the designated time of 9:35 am. Each minute detail was discussed, and nothing was taken for granted. Takeoff procedure, flight course and altitude, radio silence, when to drop belly tanks, the tremendous importance of precise timing and the position of the covering element: all were discussed and explained until Mitchell was sure that each of his pilots knew his part and the parts of the other pilots from takeoff to return.

Mitchell chose pilots from the 12th, 70th, and 339th Fighter Squadrons. These were the only P-38 squadrons on Guadalcanal. The only belly tanks we had on Guadalcanal were 165-gallon tanks, so we had to send to Port Moresby for a supply of the larger 310-gallon tanks. We put one tank of each size on each plane. This gave us enough fuel to fly to the target area, stay in the area where we expected the admiral for about 15 minutes, fight, and come home. The larger fuel tanks were flown in that night, and ground crews worked all night getting them installed along with a Navy compass in Mitchell’s plane.

Captain Tom Lanphier’s P-38 #122 Phoebe on Guadalcanal with the 339th Fighter Squadron. Lanphier was originally given credit for half a kill before investigations revealed that Barber was the sole marksman.

Four of our pilots were designated to act as the “killer section” with the remainder as their protection. Mitchell said that if he had known there were going to be two bombers in the flight he would have assigned more men to the killer section. The word for bomber and bombers is the same in Japanese. (Author’s note: Ames is incorrect on this point about the Japanese language).

Captain Thomas G. Lanphier, Jr., led the killer section. His wingman was 1st Lt. Rex T. Barber. 1st Lt. Besby F. “Frank” Holmes led the second element. His wingman was 1st Lt. Raymond K. Hine.

The cover section was led by Mitchell and included myself and 11 other pilots. Eight of the 16 pilots on the mission were from the 12th Fighter Squadron, which was my squadron.

Although 18 P-38s were scheduled to go on the mission, only 16 were able to participate because one plane blew a tire on the runway on takeoff and another’s belly tanks failed to feed properly.

“Bogeys! Eleven O’Clock, High!”

It was Palm Sunday, April 18, 1943. But since there were no religious holidays on Guadalcanal, we took off at 7:15 am, joined in formation, and left the island at 7:30 am, just two hours and five minutes before the planned interception. It was an uneventful flight but a hot one, at from 10 to 50 feet above the water all the way. Some of the pilots counted sharks. One counted pieces of driftwood. I don’t remember doing anything but sweating. Mitchell said he may have dozed off on a couple of occasions but received a light tap from “The Man Upstairs” to keep him awake.

Mitchell kept us on course flying the five legs by compass, time, and airspeed only. As we turned into the coast of Bougainville and started to gain altitude, after more than two hours of complete radio silence, 1st Lt. Douglas S. Canning––Old Eagle Eyes–– uttered a subdued “Bogeys! Eleven o’clock, high!” It was 9:35 am. The admiral was precisely on schedule, and so were we. It was almost as if the affair had been prearranged with the mutual consent of friend and foe. Two Betty bombers were at 4,000 feet with six Zeros at about 1,500 feet higher, above and just behind the bombers in a “V” formation of three planes on each side of the bombers.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in dress whites, photographed on the morning he was killed, addresses a group of pilots at Rabaul, April 18, 1943. His death came as a tremendous blow to the Japanese.

We dropped our belly tanks. We put our throttles to the firewall and went for altitude. The killer section closed in for the attack while the cover section stationed themselves at about 18,000 feet to take care of the expected fighters from Kahili. As Mitchell said, “The night before we knew the Japanese had 75 Zeros on Bougainville and I wanted to be where the action was.

I thought, “Well, I’m going on up higher and we’re going to be up there and have a turkey shoot.’” We expected from 50 to 75 Zeros should be there to protect Yamamoto just as we had protected Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox when he came to visit a couple of weeks before. We’d had as many fighters in the air to protect Knox as we could get off the ground. I guess the Japanese had all their fighters lined up on the runway for inspection. Anyway, none of the Zeros came up to meet us. Our intercept force encountered only the Zeros that were escorting Yamamoto.

Lanphier and Barber: The First to Make Contact With the Enemy

Lanphier and Barber headed for the enemy. When they were about a mile in front and two miles to the right of the bombers, the Zeros spotted them. Lanphier and Barber headed down to intercept the Zeros. The Bettys nosed down in a diving turn to get away from the P-38s. Holmes, the leader of the second element, could not release his belly tanks so, in an effort to jar them loose, he turned off down the coast, kicking his plane around to knock the tanks loose. Ray Hine, his wingman, had no choice but to follow him to protect him. So Lanphier and Barber were the only two going after the Japs for the first few minutes.

Ground crewmen look over Lieutenant Robert Petit’s P-38, Miss Virginia, which Barber borrowed for the mission; he returned it to Henderson Field with over 100 bullet holes.

From this point onward, accounts of the fight get mixed up about who shot down whom. Briefly, here is probably what happened based on the accounts of all involved. I did not see what was happening 18,000 feet below me.

As Lanphier and Barber were intercepted by the Zeros, Lanphier turned head-on into them and shot down one Zero and scattered the others. This gave Barber the opportunity to go for the bombers. As Barber turned to get into position to attack the bombers, he lost sight of them under his wing, and when he straightened around he saw only one bomber, going hell bent for leather downhill toward the jungle treetops.

Barber went after the Betty and started firing over the fuselage at the right engine. And as he slid over to get directly behind the Betty, his fire passed through the bomber’s vertical fin and some pieces of the rudder separated from the plane. He continued firing and was probably no more than 100 feet behind the Betty when it suddenly snapped left and slowed down rapidly, and as Barber roared by he saw black smoke pouring from the right engine.

Shooting Down the Betty

Barber believed the Betty crashed into the jungle, although he did not see it crash. And then three Zeros got on his tail and were making firing passes at him as he headed toward the coast at treetop level taking violent evasive action. Luckily, two P-38s from Mitchell’s flight saw his difficulty and cleared the Zeros off his tail. Holmes said it was he and Hine that chased the Zeros off Barber’s tail. Barber said he then looked inland and to his rear and saw a large column of black smoke rising from the jungle, which he believed to be the Betty he’d shot.

As Barber headed toward the coast he saw Holmes and Hine over the water with a Betty bomber flying below them just offshore. He then saw Holmes and Hine shoot at the bomber with Holmes’ bullets hitting the water behind the Betty and then walking up and through the right engine of the Betty. Hines started to fire, but all of his rounds hit well ahead of the Betty. Then Holmes and Hine passed over the Betty and headed south.

Barber said that he then dropped in behind the Betty flying over the water and opened fire. As he flew over the bomber it exploded, and a large chunk of the plane hit his right wing, cutting out his turbo supercharger intercooler. Another large piece hit the underside of his gondola, making a very large dent in it.

Wreckage of Yamamoto’s “Betty” lies on the jungle floor on the island of Bougainville.

After this, he, Holmes, and Hine fired at more Zeros. Barber said that both he and Holmes shot down a Zero, but Hine was seen heading out to sea smoking from his right engine. As Barber headed home, he saw three oil slicks in the water and hoped that Hine was heading for Guadalcanal, but that was not the case.

Lanphier, having scattered the Zeros, found himself at about 6,000 feet. Looking down, he saw a Betty flying across the treetops, so he came down and began firing a long, steady burst across the bomber’s course of flight, from approximately right angles. In another account, Lanphier said he was clearing his guns. By both accounts, he said he felt he was too far away, yet, to his surprise, the bomber’s right engine and right wing began to burn and then the right wing came off and the Betty plunged into the jungle and exploded.

Return to Guadalcanal

Lanphier said that three Zeros came after him, and he called Mitchell to send someone down to help him. Then, hugging the earth and the treetops while the Zeros made passes at him, he unwittingly led them over a corner of the Japanese fighter strip at Kahili.

He then headed east and, with the Zeros on his tail, he got into a high-speed climb and lost them at 20,000 feet; he got home with only two bullet holes in his rudder. Contrast this to the 104 bullet holes in Barber’s plane, plus the knocked-out intercooler and the huge dent in his gondola.

Flying back to Guadalcanal, I heard Lanphier get on the radio and say, “That SOB won’t dictate peace terms in the White House.” This really upset me because we were to keep complete silence about the fact that we had gone after Yamamoto. The details of this mission were not to leave the island of Guadalcanal.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

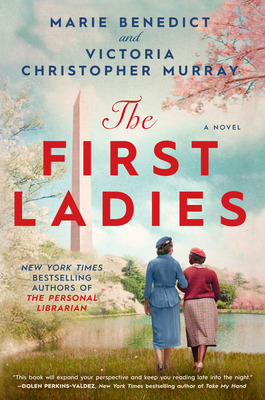

Read-Alike Friday: The First Ladies

The First Ladies by Marie Benedict & Victoria Christopher Murray

The daughter of formerly enslaved parents, Mary McLeod Bethune refuses to back down as white supremacists attempt to thwart her work. She marches on as an activist and an educator, and as her reputation grows she becomes a celebrity, revered by titans of business and recognized by U.S. Presidents. Eleanor Roosevelt herself is awestruck and eager to make her acquaintance. Initially drawn together because of their shared belief in women’s rights and the power of education, Mary and Eleanor become fast friends confiding their secrets, hopes and dreams—and holding each other’s hands through tragedy and triumph.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt is elected president, the two women begin to collaborate more closely, particularly as Eleanor moves toward her own agenda separate from FDR, a consequence of the devastating discovery of her husband’s secret love affair. Eleanor becomes a controversial First Lady for her outspokenness, particularly on civil rights. And when she receives threats because of her strong ties to Mary, it only fuels the women’s desire to fight together for justice and equality.

This is the story of two different, yet equally formidable, passionate, and committed women, and the way in which their singular friendship helped form the foundation for the modern civil rights movement.

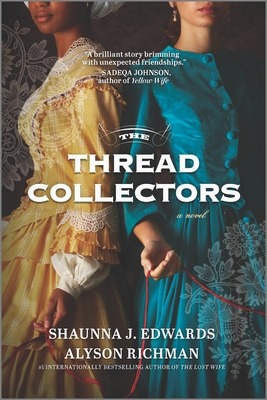

The Thread Collectors by Shaunna J. Edwards & Alyson Richman

1863: In a small Creole cottage in New Orleans, an ingenious young Black woman named Stella embroiders intricate maps on repurposed cloth to help enslaved men flee and join the Union Army. Bound to a man who would kill her if he knew of her clandestine activities, Stella has to hide not only her efforts but her love for William, a Black soldier and a brilliant musician.

Meanwhile, in New York City, a Jewish woman stitches a quilt for her husband, who is stationed in Louisiana with the Union Army. Between abolitionist meetings, Lily rolls bandages and crafts quilts with her sewing circle for other soldiers, too, hoping for their safe return home. But when months go by without word from her husband, Lily resolves to make the perilous journey South to search for him.

As these two women risk everything for love and freedom during the brutal Civil War, their paths converge in New Orleans, where an unexpected encounter leads them to discover that even the most delicate threads have the capacity to save us. Loosely inspired by the authors' family histories, this stunning novel will stay with readers for a long time.

The Women's March by Jennifer Chiaverini

Twenty-five-year-old Alice Paul returns to her native New Jersey after several years on the front lines of the suffrage movement in Great Britain. Weakened from imprisonment and hunger strikes, she is nevertheless determined to invigorate the stagnant suffrage movement in her homeland. Nine states have already granted women voting rights, but only a constitutional amendment will secure the vote for all. To inspire support for the campaign, Alice organizes a magnificent procession down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, the day before the inauguration of President-elect Woodrow Wilson, a firm antisuffragist.

Joining the march is thirty-nine-year-old New Yorker Maud Malone, librarian and advocate for women’s and workers’ rights. The daughter of Irish immigrants, Maud has acquired a reputation—and a criminal record—for interrupting politicians’ speeches with pointed questions they’d rather ignore.

Civil rights activist and journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett resolves that women of color must also be included in the march—and the proposed amendment. Born into slavery in Mississippi, Ida worries that white suffragists may exclude Black women if it serves their own interests. On March 3, 1913, the glorious march commences, but negligent police allow vast crowds of belligerent men to block the parade route—jeering, shouting threats, assaulting the marchers—endangering not only the success of the demonstration but the women’s very lives.

Inspired by actual events, The Women’s March offers a fascinating account of a crucial but little-remembered moment in American history, a turning point in the struggle for women’s rights.

Undiscovered Country by Kelly O'Connor McNees

In 1932, New York City, top reporter Lorena “Hick” Hickok starts each day with a front page byline―and finishes it swigging bourbon and planning her next big scoop.

But an assignment to cover FDR’s campaign―and write a feature on his wife, Eleanor―turns Hick’s hard-won independent life on its ear. Soon her work, and the secret entanglement with the new first lady, will take her from New York and Washington to Scotts Run, West Virginia, where impoverished coal miners’ families wait in fear that the New Deal’s promised hope will pass them by. Together, Eleanor and Hick imagine how the new town of Arthurdale could change the fate of hundreds of lives. But doing what is right does not come cheap, and Hick will pay in ways she never could have imagined.

Undiscovered Country artfully mixes fact and fiction to portray the intense relationship between this unlikely pair. Inspired by the historical record, including the more than three thousand letters Hick and Eleanor exchanged over a span of thirty years, McNees tells this story through Hick’s tough, tender, and unforgettable voice. A remarkable portrait of Depression-era America, this novel tells the poignant story of how a love that was forced to remain hidden nevertheless changed history.

#historical fiction#fiction#library books#readalikes#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#to read#tbr#tbrpile#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thousands of spectators cheer as over a quarter of a million marchers show support for the National Recovery Administration (NRA) in a parade on Fifth Avenue on September 13, 1933. The NRA was part of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal to institute industry-wide codes intended to eliminate unfair trade practices, reduce unemployment, establish minimum wages and maximum hours, and guarantee the right of labor to bargain collectively. The NRA ended when it was invalidated by the Supreme Court in 1935, but many of its provisions were included in subsequent legislation. The NRA flag, at the left, is the symbol of a Blue Eagle with the motto "We do our part." This view is looking north at 42nd St.

Photo: Associated Press

#vintage New York#1930s#NRA#National Recovery Admin.#New Deal#parade#5th Ave.#Fifth Ave.#42nd St.#labor#Sept. 13#13 Sept.#1930s New York#labor laws#worker protection

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

大纽约社区介绍之University Heights, the Bronx

大学高地(University Heights)位于布朗克斯西北部,是一块面积不大、有些地方还很邋遢的飞地。布朗克斯社区大学(Bronx Community College)占地45英亩,校园横跨悬崖峭壁,视野开阔,对社区的影响举足轻重。

这不是一所典型的通勤学校。该学院最著名的建筑由斯坦福-怀特(Stanford White)设计,2012年,学院大部分建筑被评为国家历史地标。

1973年,这个拥有约3万人口的社区并不景气。纽约大学(NYU)在19世纪末建立了这所校园,作为其格林威治村(Greenwich Village)以外的乡村校区,随着犯罪率的上升和入学率的下降,纽约大学以约6200万美元的价格将学校卖给了州政府。

据史料记载,随着有宿舍的大学被学生每晚回家的学院所取代,一个艰难的过渡时期随之而来。West 183rd Street和Loring Place North等曾经是学生和教师居住的街道变得空旷破败。

但学院的管理者和居民们认为,这所在20世纪80年代斥资数百万翻新校外建筑的学校就像一条马奇诺防线(Maginot Line),阻止了南布朗克斯的凋敝。

如今,隶属于纽约城市大学(City University of New York)的布朗克斯社区大学拥有约11000名学生和1600名教师,校���有保安人员看守,校园周围有巡逻车巡逻;2012年,由Robert A.M. Stern Architects设计的新北楼和图书馆落成剪彩。目前,学校还在翻修主广场。

6岁的盖尔-道森(Gail Dawson)说:"这个地区唯一真正稳定的好东西就是大学"。1978年,她从哈林区(Harlem)的一个公共住宅区搬到了这个社区,为的是给孩子们提供一个更安全的成长环境。当时,和现在一样,身患残疾的道森女士住在一套一居室的公寓里,房租由联邦住房券支付。

她说,虽然该地区的一些城市公园已经荒废,但学院却更注重其外观。"我喜欢这里的树,"她说。"这里很漂亮"。

大学高地给人的感觉是静态的。伟大美国人名人堂(Hall of Fame for Great Americans)是一个露天校园,收藏了约100尊半身铜像,包括艺术家、发明家和总统,其中最近期的人物莫过于富兰克林-德拉诺-罗斯福(Franklin Delano Roosevelt)。

但变化正在迫近。

该市正在考虑重新划分Jerome Avenue两英里的区域,以建造更多经济适用房、公园和商店。目前,车库、轮胎店和其他汽车行业占据了这条街道。

一些长期经营的企业主对此表示担忧,比如43岁的佩德罗-蒙西翁(Pedro Moncion),他在West 181st Street拥有一家San Rafael Auto Repair修车厂。蒙西翁先生说,将该街道重新划分为禁止工业用途可能会导致他已经经营了28年的生意终结。

此外,曾经住在附近希望山(Mount Hope)的蒙西翁先生说,在附近的许多街道上,购买杂货、衣服和电子产品的地方已经比比皆是。他说:"我不知道我们还能想要什么"。

大学高地坐落在一座小山上,从这里可以俯瞰曼哈顿和新泽西州的帕利塞德悬崖(Palisades cliffs)。大学高地的北面是West Fordham Road,南面是West Burnside Avenue,东面是Jerome Avenue,西面是哈林河(Harlem River)。根据2010年的人口普查数据,94%的家庭居住在出���房中,而整个城市的这一比例为69%。根据经纪人的说法,这些出租单元中的许多都被预留给第8条(Section 8)补贴住房,或者被安排成单人间(single-room-occupancy)。

市价单位确实存在,比如位于Sedgwick Avenue的River Hill Gardens,这是一座由Goldfarb Properties拥有的五栋砖砌综合楼。校园北面还建有优雅的七层砖砌公寓楼,其中一些是装饰艺术时期的产物。

经纪人说,总的来说,University Avenue(也称Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard)以西的公寓楼最古老,也最时尚。

除此之外,还有零星的砖砌独户住宅,如West 179th Street的独户住宅,它们面对的是带前院的半独立式住宅。少数共管公寓包括位于Grand Avenue和Davidson Avenue的一些公寓。但有些共管公寓受到住房发展基金公司(Housing Development Fund Corporation)的限制,根据该公司的规定,购房者的收入不能超过上限。

市场价房产可能很难找到。据Meridian Realty Partners的副经纪人Jackson Strong称,如果有房,700平方英尺左右的市价一居室共管公寓平均售价为9万美元,两居室为14万美元。

Strong先生说,独户住宅的价格约为30万美元,而两户住宅可能高达45万美元。

StreetEasy提供的数据显示,截至今年8月31日,所有住房的平均销售价格为13.5万美元。2014年的平均销售价格为13.7万美元,2013年为15.9万美元。根据StreetEasy的数据,今年截至8月,一居室公寓的平均租金为1270美元,2014年为1230美元,2013年为1150美元。

Strong先生说:"我们正在吸引那些被纽约市其他地区拒之门外的人,甚至是布朗克斯的其他地区"。

由于大多数学生都住在别处,大学城的夜生活很少。位于Aqueduct Avenue East和West 181st Street的BX Campus Deli熟食店似乎是少数几家承认自己存在的商家之一。

在West Fordham Road上,有一家Dallas BBQ烧烤店在周末举办D.J.派对。在West Burnside Avenue上,有一些小店出售水果、美容用品和眼镜。

Aqueduct Walk沿着老克罗顿水渠(Old Croton Aqueduct)的顶端延伸,从19世纪40年代到50年代,这条水渠一直将饮用水从威彻斯特县(Westchester County)输送到这座城市。如果想重温美国历史,布朗克斯社区大学的名人堂也许值得一去。10月18日,布朗克斯社区大学将参加全市范围的"纽约开放日"(Open House New York)活动,届时还将参观由马塞尔-布劳尔(Marcel Breuer)设计的粗野主义(Brutalist)风格建筑。

该地区划入了几所小学,包括Andrews Avenue上的Public School 291、Sedgwick Avenue上的Public School 226和Jerome Avenue上的Public School 33。这三所学校都教授幼儿园到五年级的课程;P.S. 226和P.S. 33还设有学前班。

根据该市的统计数据,在2013-14学年的州考试中,P.S. 291的成绩略好于其他两所学校,当时有18%的学生英语达标,31%的学生数学达标。全市的这两个数字分别为30%和39%。

公立中学有Creston Academy、East Fordham Academy for the Arts和Academy for Personal Leadership and Excellence可供选择,这些学校都在社区外。

St. Nicholas of Tolentine Elementary School是一所教会学校,位于Andrews Avenue North,学制为幼儿园至八年级。

大都会北方铁路(Metro-North Railroad)的哈德逊线(Hudson Line)在大学高地有一站。到大中央车站(Grand Central Terminal)的车程为21至24分钟,月票价格为201美元。

4号线地铁沿Jerome Avenue停靠Burnside Avenue、183rd Street和Fordham Road。

在纽约大学落户之前,校园所在区域有几处庄园,其中一处属于马里(Mali)家族,该家族生产台球毡和其他台球产品。他们的砖房最初成为宿舍,如今是巴特勒厅(Butler Hall),为高中生上大学做准备。

转载自 New York Times, University Heights, the Bronx: Anchored by a College Campus

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1. Belgian police raid European People’s Party's offices in Brussels

Belgian police and German authorities raided the headquarters of the European People’s Party (EPP) in Brussels on Tuesday as part of an investigation into financial irregularities. Read more.

For a more in-depth look into Mario Voigt, the German politician at the heart of the EPP police raid, click here.

2. Arrested US reporter Evan Gershkovich is no spy — but he is a wonderful footballer

Evan, my friend and former football team-mate, was arrested by the Russian authorities last week on charges of espionage — an allegation as ludicrous as it is tragic. Read more.

3. More people entitled to higher medical reimbursements than 20 years ago

The number of people in Belgium who are entitled to an Increased Allowance (VT status) resulting in them paying less upfront when visiting a GP has increased, however, not all people who are eligible make use of this status. Read more.

4. Labour conditions in Belgium are deteriorating across the board

The quality of working conditions in Belgium has been rapidly deteriorating in recent years, according to revealing research carried out by several Belgian universities. Read more.

5. Belgian striker Lukaku targeted by racist chants against Juventus

Romelu Lukaku was the target of racist abuse by Juventus fans on Tuesday night during the Italian Cup semi-final between Juventus and Inter Milan in Turin, his communications agency has said. Read more.

6. Stromae cancels more European tour dates due to health issues

Stromae has cancelled all of the concerts of his European tour until the end of May for medical reasons. 15 shows in all have been cancelled, including appearances in the European capitals of Berlin, London and Rome. Read more.

7. Hidden Belgium: Villa Empain

The art deco Villa Empain on Avenue Franklin Roosevelt in Brussels was commissioned in 1930 by Louis Empain, son of the rich banker Edouard Empain. Designed by Swiss architect Michel Polak, it could be the home of a Hollywood movie star. Read more.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A couple of days ago my brother and I were making our way home from Notre Dame and were about to buy train tickets until a couple stopped and asked if we knew where Avenue Franklin Roosevelt was. They had some accents and their English was a bit broken but we understood they were at the wrong station. We were in station C but they needed station B. Eventually my brother and I were like hey it's not far we can just take you there. When we crossed the street and saw the sign for their train station, the man mentioned he was Japanese and the woman he was with is Finnish. They were visiting from Finland. My brother and I are Haitian, I recently left the US and he came to visit. We were speaking English. In Paris, France right in front of Notre Dame. I love globalism :)

One time this man approached me in a bar talking in Spanish. So I assumed he was Spanish and we started speaking, we had a whole ass conversation and at some point he was like. So what part of Spain are you from? And I said well I’m Italian actually. What part of Spain are you from? And he was like. I’m Greek.

225K notes

·

View notes

Text

Venice Tipton Spraggs (c. 1905 - December 1, 1956) served as the Washington Bureau Chief for the Chicago Defender. She was born in Birmingham to Barbara Tipton. She attended Spelman College and married William Spraggs (1924) a presser from Birmingham. The couple had no children.

She wrote about prominent issues facing Black women and encouraged her readers to pursue every avenue of education afforded to them. She authored a column titled “Women in the National Picture” which detailed the activities of the National Council of Negro Women, the National Negro Congress, and the National Association of Colored Women. Her column reported on Washington’s legislative activity on issues relevant to Black women. Her mastery of journalism resulted in her historic induction into Theta Sigma Phi on August 6, 1947, in DC. She was elected for membership by both the local chapter and the fraternity’s national leadership, becoming the first African American to join the organization.

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her as a supervisor in the National Youth Administration. In 1948, she began holding minor political appointments with the Democratic Party’s Women’s Division, and in 1953, she was appointed assistant to the vice chairman of the DNC. She lobbied against the use of poll taxes and other discriminatory practices that disproportionately impacted Black voters in the South. As a party courier, she was charged with reaching women voters during the 1952 presidential election campaign.

She was a staunch supporter of Adlai Stevenson during his 1956 presidential bid and served as the Stevenson campaign’s election committee liaison with the DNC. She traveled the country campaigning for Stevenson, and in the process increased his popularity in the African American community. She fell ill with a bronchial disease during a campaign trip and returned to DC. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

MARDI 11 FEVRIER 2025 (Billet 2 / 4)

Sophie (Rob.) nous a adressé ce mail qu’elle nous a autorisés à partager sur le Blog. Nous sommes persuadés qu’il intéressera beaucoup de lecteurs(trices)/abonnés(ées).

_______________________________________

Chère Marina, cher Jean-Marie,

J'ai honte de ne pas m'être manifestée depuis si longtemps... et pourtant j'ai toujours autant de plaisir à lire le Blog. (1000 mercis chère Sophie – NDLR du Blog)

Pour une fois, j'ai quelque chose d'intéressant à vous raconter : je suis allée cette semaine avec Aurélie voir l'exposition « Dolce & Gabbana » au Grand Palais et nous avons été emballées. Pourtant les conditions de la visite sont loin d'être idéales : même si le Grand Palais a été entièrement refait, les salles d'exposition sont trop petites et il y avait un monde fou ! Ce n'est pas comme à Rétro Mobile, les gens ne vous laissent pas la place pour regarder... Malgré ce bémol, ce que l'on voit est époustouflant.

Tout d'abord le décor de chaque salle en lui-même se référant à la collection de vêtements qui y est exposée. Et puis la variété d'univers allant de sobres robes noires (inspiration sicilienne) aux inimaginables vêtements couverts de strass, de dorures, de tapisseries, de moulages, tous plus clinquants et kitsch les uns que les autres (inspirés par l'histoire italienne, le cinéma, l'opéra...). Ce qui m'a particulièrement plu (et qui faisait partie des choses les plus "raisonnables"), ce sont des jupes très amples peintes à la main avec des motifs inspirés de la Sicile.

Je pense que c'est exceptionnel car ces vêtements ne sont jamais montrés au grand public, les défilés étant réservés aux « very rich happy fews »..

Bien sûr, vous pouvez faire part aux blogueurs de mon enthousiasme pour cette expo !

Je vous embrasse.

Sophie (Rob.)

_______________________________________

Si vous voulez en savoir plus, lisez aussi le petit texte ci-dessous et ne manquez pas la vidéo ci-dessus.

« DU CŒUR A LA MAIN : DOLCE&GABBANA »

Du 10 janvier 2025 Au 31 mars 2025

Réunissant pour la première fois les créations uniques de la maison de mode de luxe, « Du Cœur à la Main : Dolce&Gabbana » est une lettre d’amour ouverte à la culture italienne, source d’inspiration constante de Domenico Dolce et Stefano Gabbana. L’exposition retrace l’itinéraire esthétique de leurs créations, d’abord portées dans leur cœur, puis exécutées à la main dans leurs ateliers.

Les modèles exposés, des pièces uniques réalisées par des artisans italiens dotés de savoir-faire incomparables, mettent en évidence les différents éléments de la culture italienne qui nourrissent les créations de Dolce&Gabbana. L’exposition, selon un parcours thématique, reflète la richesse de leurs inspirations puisées dans l’histoire de l’art italien, l’architecture, l’artisanat, les cultures régionales, la musique, l’opéra, le ballet, le cinéma, les traditions folkloriques, le théâtre et bien sûr… « la dolce vita » !

(Source : La plaquette de l’Exposition)

________________________________

Adresse : Le Grand Palais 7 avenue Winston Churchill, 75008 Paris

Horaires : du lundi au mercredi, de 10h à 19h30

Du jeudi au vendredi, de 9h à 22h

Du samedi au dimanche, de 9h à 19h30

(Attention, le Grand Palais sera exceptionnellement fermé les 10 et 11 février)

Tarifs : 22 ou 24€ (selon les jours)

Métro : lignes 1, 9, 13 / Stations : Franklin D. Roosevelt, Champs-Elysées - Clemenceau RER : ligne C / Station : Invalides Bus : lignes 28, 42, 52, 63, 72, 73, 80, 83, 93

0 notes