#Australian Citizenship Test 2023

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#Australian Values#Australian History#Government#National Symbols#Australian Citizenship Test Preparation#Australian Citizenship Practice Tests#Australian Citizenship Classes#Australian Citizenship Test 2023#How to Become an Australian Citizen#Australian Citizenship Requirements

0 notes

Text

Tips For Starting Preparation For the Australian Citizenship Test In 2023

Have you been wondering about the contents of the Australian citizenship test or are you reading it for the first time? Irrespective of your prior knowledge, it is worth knowing that there are a few tips and tricks you may want to check out as you go through the Australian citizenship course or booklet. In this blog, we are summing up a few useful tips and tricks that may come in handy as you appear for Australian citizenship test practice sessions or the actual test.

As a beginner, you will need to apply for Australian citizenship online. They will mail you their response and the test details within 3-4 weeks of application. Some people may need to wait longer depending on the office criterion and other related regulations. And understand that you may get very less time to prepare for the test. So, make sure you begin your preparations as you send your application. There is a lot of content available online, Australian citizenship test booklets, and similar other stuff that may help you with your preparations.

If they ask you to come for the test, know that they will ask you for some relevant documents as well. The most commonly demanded documents include the current passport, Australian driver’s license, and medicare card. They will make copies of the submitted documents and click your photo as you appear for the test. They will tell you that the test takes 2-3 hours but as many have reported, it is a much faster process.

The test is a multiple choice paper with 20 questions on a computer and usually, the candidate gets 45 minutes to complete it. It is in English and in writing only. If you aren’t fluent in English or don’t understand the language, you will get assistance from translators as they wish to provide everyone with a fair chance to the opportunity.

Please know that the citizenship test is completely free of cost and if anyone is asking for any money or a deposit for it, they are scamming you. Don’t fall for any such ruse.

Lastly, the test can be taken as many times as you want. Make sure that you go through the booklets provided by the Australian government. It will come in two parts out of which Book 1 is testable while Book 2 is not. You need to get through Book 1 thoroughly while Book 2 can be read for your personal interest. The test isn’t allowed to pose any question outside Book 1, so make sure you go through it thoroughly.

#australian citizenship#australian citizenship course#australian citizenship test booklet#australian citizenship test practice#australia citizenship practice test#australian citizenship test free#australian citizenship test practice 2023#australian citizenship practice test 2023 free

0 notes

Text

Global Top 5 Companies Accounted for 71% of total Sandalwood Extract market (QYResearch, 2021)

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus Santalum. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Indian Sandalwood Oil (Santalum Album) is extracted from the woods for use. Sandalwood is the second most expensive wood in the world, after African blackwood. Both the wood and the oil produce a distinctive fragrance that has been highly valued for centuries. Consequently, species of these slow-growing trees have suffered over-harvesting in the past century.

Most Sandalwood species are semi-parasitic and several produce a highly aromatic wood. The most common species are Indian sandalwood (Santalum album) and Australian sandalwood (Santalum spicatum), although other species are used for their scent as well.

The oil that distilled from eucarya spicata species, amyris and so on is not belonging to the Sandalwood Oil.

Different sandalwood species are indigenous to India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh (S. album), and Australia (S. spicatum and S. lanceolatum), as well as to several Pacific Islands such as Hawaii (S. ellipticum), Fiji and Tonga (S. yasi), Papua New Guinea (S. macgregorii), Vanuatu and New Caledonia (S. austrocaledonicum) and French Polynesia (S. insulare).

Traditionally, sandalwood is wild-harvested, since cultivation is difficult. Because of over- and illegal harvesting, supplies of sandalwood, especially Indian sandalwood, have decreased considerably over the last 10-15 years. Consequently, efforts to cultivate sandalwood have increased; Australia now has several plantations of Indian sandalwood trees.

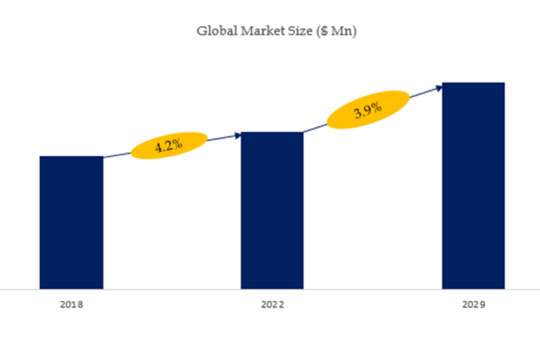

According to the new market research report “Global Sandalwood Extract Market Report 2023-2029”, published by QYResearch, the global Sandalwood Extract market size is projected to reach USD 0.16 billion by 2029, at a CAGR of 3.9% during the forecast period.

Figure. Global Sandalwood Extract Market Size (US$ Million), 2018-2029

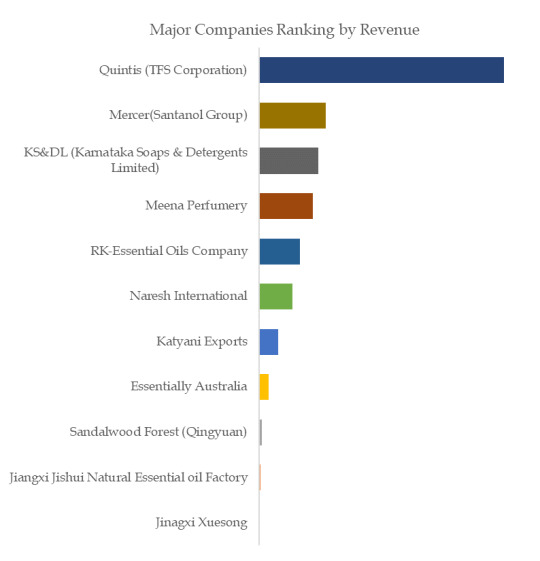

Figure. Global Sandalwood Extract Top 11 Players Ranking and Market Share(Based on data of 2021, Continually updated)

The global key manufacturers of Sandalwood Extract include Quintis (TFS Corporation), Mercer(Santanol Group), KS&DL (Karnataka Soaps & Detergents Limited), Meena Perfumery, RK-Essential Oils Company, Naresh International, Katyani Exports, Essentially Australia, Sandalwood Forest (Qingyuan), Jiangxi Jishui Natural Essential oil Factory, etc. In 2020, the global top five players had a share approximately 71.0% in terms of revenue.

About QYResearch

QYResearch founded in California, USA in 2007.It is a leading global market research and consulting company. With over 16 years’ experience and professional research team in various cities over the world QY Research focuses on management consulting, database and seminar services, IPO consulting, industry chain research and customized research to help our clients in providing non-linear revenue model and make them successful. We are globally recognized for our expansive portfolio of services, good corporate citizenship, and our strong commitment to sustainability. Up to now, we have cooperated with more than 60,000 clients across five continents. Let’s work closely with you and build a bold and better future.

QYResearch is a world-renowned large-scale consulting company. The industry covers various high-tech industry chain market segments, spanning the semiconductor industry chain (semiconductor equipment and parts, semiconductor materials, ICs, Foundry, packaging and testing, discrete devices, sensors, optoelectronic devices), photovoltaic industry chain (equipment, cells, modules, auxiliary material brackets, inverters, power station terminals), new energy automobile industry chain (batteries and materials, auto parts, batteries, motors, electronic control, automotive semiconductors, etc.), communication industry chain (communication system equipment, terminal equipment, electronic components, RF front-end, optical modules, 4G/5G/6G, broadband, IoT, digital economy, AI), advanced materials industry Chain (metal materials, polymer materials, ceramic materials, nano materials, etc.), machinery manufacturing industry chain (CNC machine tools, construction machinery, electrical machinery, 3C automation, industrial robots, lasers, industrial control, drones), food, beverages and pharmaceuticals, medical equipment, agriculture, etc.

For more information, please contact the following e-mail address:

Email: [email protected]

Website: https://www.qyresearch.com

0 notes

Text

Albanese Government Targets Education and Health Skills in Migration Plans

THE SKILLS GOVERNMENT targets in the points-tested Skilled Independent category give a clear signal of the skills it thinks will be in long-term demand. It also gives a signal to overseas students what courses it wants them to study if they want to maximise their chances of securing permanent residence.

The Skilled Independent category is a purely discretionary category that governments ramp up or down depending on demand in other skill stream categories to deliver whatever level of permanent migration program has been set (currently 190,000 plus 3,000 places in the Pacific Engagement Visa and not counting New Zealand citizens who now have a direct pathway to Australian citizenship).

Prior to 2017-18, both Labor and Coalition governments maintained the Skilled Independent category at well above 40,000 places per annum. Along with a cut to the overall migration program, former Home Affairs Minister and now Opposition Leader Peter Dutton cut the Skilled Independent category in 2017-18 and 2018-19 to less than 35,000.

The Skilled Independent category was further reduced during the pandemic with the closure of international borders. The focus of the migration program shifted towards state and territory-nominated visas as well as the new Global Talent Visa and the Business Investment and Innovation Program (BIIP) visas. The Coalition also started clearing the partner visa backlog it had illegally engineered.

The new Labor Government increased the overall migration program and along with it, the size of both the Skilled Independent category and state-nominated categories. The Global Talent visa and BIIP visas were significantly reduced given a range of concerns with these visas.

To deliver the larger Skilled Independent category, the Labor Government dramatically increased the size of invitation rounds for this category, reduced the frequency of these, lowered pass marks and initially targeted a very wide range of occupations.

The Coalition Government tended to issue small invitation rounds of usually less than 1,000, run these relatively frequently and use very high pass marks.

The very large invitation rounds under the Labor Government were partly due to an increase in the portion of invitations that did not convert to visa grant (often due to initial claims against visa criteria not being met when checks were undertaken). Nevertheless, the large invitation rounds created a backlog of applications that meant invitation rounds did not need to be run as frequently.

In late December 2023, the Government issued its first invitation round in the Skilled Independent category for 2023-2024. The two outstanding characteristics of this invitation round were its relatively small size compared to invitation rounds in 2022-2023 and the very narrow range of skilled occupations that were targeted.

This invitation round also does not distinguish between offshore and onshore applicants. That must mean the Government expects relatively few onshore applications and is seeking to attract offshore applications at a time when it is also trying to drive down net migration.

The most striking feature of the latest invitation round is that it focuses almost entirely on health and education-related occupations. There are no occupations in occupational segments such as IT, finance, engineering or trades.

This will send a very clear signal to potential offshore applicants as well as to overseas students looking to use an Australian qualification to apply for skilled migration. It will leave a large portion of the 600,000 plus students and around 200,000 temporary graduates currently in Australia (as well as possibly around 100,000 former students on a COVID-related visa) in immigration limbo if they do not have health or education-related qualifications.

While those students and temporary graduates could still migrate via an employer-sponsored or state-nominated visa, their options have now been significantly narrowed

Source: Independent Australia

0 notes

Text

Out for the count – America’s census looks out of date in the age of big data | International

<![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ]]> Jan 20th 2020A DOG:SLED or a snowmobile is the surest way to reach Toksook Bay in rural Alaska, where Steven Dillingham, the director of America’s census bureau, will arrive to count the first people in the country’s decennial population survey on January 21st. The task should not take long—there were only 590 villagers at the last count, in 2010—but it marks the beginning of a colossal undertaking. Everyone living in America will be asked about their age, sex, ethnicity and residence over the coming months (and some will be asked much more besides).This census has already proved unusually incendiary. An attempt by President Donald Trump to include a question on citizenship, which might have discouraged undocumented immigrants from responding, was thwarted by the Supreme Court. His administration has also been accused in two lawsuits of underfunding the census, thus increasing the likelihood that minorities and vulnerable people, such as the homeless, will be miscounted.America’s constitution mandates that a census take place every decade so that legislators “might rest their arguments on facts”, as James Madison put it in 1790. The government has become more reliant on this knowledge as its responsibilities have grown. In 2016 census data were used to direct some $850bn of funding for programmes such as Medicaid, food stamps, school lunches and roadbuilding. The results are also used to apportion seats in Congress, as well as by academics, genealogists and even supermarket chains deciding where to open new shops.Population counts long predate the founding fathers. Babylonians recorded their numbers on clay tiles as far back as 3800BC to work out how much food to grow. In ancient Athens administrators counted piles of stones, one added by each citizen, to gauge military capability and tax revenues. And Joseph and his pregnant wife Mary travelled from Nazareth to Bethlehem after Emperor Augustus decreed that “all the world should be registered”. By the 18th century, reliable and regular population counts were common in European countries, and enumerators (as census-takers are known) were being sent out to colonies around the world.A decennial survey of every household, as has just begun in America, is a tried and tested method. It provides a snapshot of an entire population. Citizens can state how they wish to be recorded and the resulting treasure-trove of data is publicly accessible. But the cost and scale of such an undertaking is growing. America’s previous census cost $92 per household, up from $16 in 1970 (in 2020 dollars). China mobilised an army of 6m enumerators to roam the country in 2010. The UN Population Fund calls a census “among the most complex and massive peacetime exercises a nation undertakes”.Migration and changing lifestyles are making it more difficult to reach everyone. Renters are trickier than homeowners to count reliably, because they move more often and live in less stable households. One study projected that this year’s American census could undercount the population by 1.2%, rising to more than 3.5% among black and Latino populations, who are less likely to own their home.Is there a better way? For the first time this year, Americans will be able to fill out the census online. This risks missing hard-to-reach groups such as indigenous populations and the old. It also introduces unforeseen headaches. In 2016 Australia’s census website crashed, leaving millions unable to submit their responses and venting their anger with the hashtag #censusfail.Nordic countries have ditched the unwieldy undertaking altogether, turning to other sources of information. In Sweden each citizen is given a personnummer, an identity number linked to government data on individuals’ health, employment, residence and more. These data are cross-referenced to produce statistics resembling the results of a traditional census. Denmark, Finland and Norway take the same approach. As societies share more information, wittingly or otherwise, new statistics can be produced. Mobile-phone records, for example, have been used to estimate commuting patterns. The Netherlands, meanwhile, conducts what it calls a “virtual” census. This is similar to the Nordic model, but also uses small-sample surveys to produce data not already held by the state, such as education levels and occupation.As long as each citizen has a unique identifier, such counts are cheaper to carry out—the Dutch government boasts that its census in 2011 cost just $0.10 per person—and can be done much more regularly. But the accuracy of the data is harder to guarantee. Population registers are never completely up to date and anyone not already on them will be missed. In Europe, two-thirds of countries are expected to use data from existing registers to some extent in the next round of censuses. This is up from just a quarter 20 years ago, according to analysis by Paolo Valente, a statistician at the UN.Making such a change is a slow process. Bernard Baffour, a researcher at the Australian National University, points out that it took decades for Sweden to implement a fully register-based census, partly because Swedes had to be reassured that their data were secure. As he puts it, “When a doctor asks how much you drink or smoke, are you happy for that to be linked with all the other information on you?” Frank de Zwart, a professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, also criticises register-based censuses for neglecting a key political function of censuses. For minorities such as native Americans, filling out a census is a powerful assertion of their place in society. A virtual census would deny them this opportunity. That said, self-reporting is far from perfect: 177,000 Britons implausibly claimed to be Jedi knights in the census of 2011.Even though Britain does not have identity cards, common in the rest of Europe, in 2013 the government tried to replace the census with other administrative data it already held. An outcry from MPs and statisticians forced ministers to shelve the idea. The public had rejected an attempt in 2006 to introduce identity cards, and recent scandals such as the harvesting of personal data from Facebook deepened Britons’ worries about privacy. Iain Bell, the statistician in charge of the census at the Office for National Statistics (ONS), emphasises the importance of public trust in producing official figures: “If people don’t want a single register of the population, we have to respect that and look to other sources.” Francis Maude, then a government minister, told MPs in 2014 that he hoped the next census, due to take place next year, would be the last. In 2023, the ONS will report back on whether this is achievable.Political rows over America’s census have shone a light on a function of government that most people consider only a handful of times over their lives, but the results of which affect them every day. Recording each member of every household seems outdated in the associated with big data, whether the data are held by governments or private companies. But in this sense, at least, America’s federal government is not big enough; its social-security system is too incomplete, and other information still too patchy, to replace the old-fashioned head-count. Will Mr Dillingham be the last enumerator to visit Toksook These types of? Don’t count upon this.Reuse this contentThe Trust Project <![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ]]>

If you enjoyed this post, you should read this: Thank You Page

source http://blognetweb.com/out-for-the-count-americas-census-looks-out-of-date-in-the-age-of-big-data-international/ source https://productreviewavoidscams.blogspot.com/2020/01/out-for-count-americas-census-looks-out.html

0 notes

Text

Out for the count – America’s census looks out of date in the age of big data | International

<![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ]]> Jan 20th 2020A DOG:SLED or a snowmobile is the surest way to reach Toksook Bay in rural Alaska, where Steven Dillingham, the director of America’s census bureau, will arrive to count the first people in the country’s decennial population survey on January 21st. The task should not take long—there were only 590 villagers at the last count, in 2010—but it marks the beginning of a colossal undertaking. Everyone living in America will be asked about their age, sex, ethnicity and residence over the coming months (and some will be asked much more besides).This census has already proved unusually incendiary. An attempt by President Donald Trump to include a question on citizenship, which might have discouraged undocumented immigrants from responding, was thwarted by the Supreme Court. His administration has also been accused in two lawsuits of underfunding the census, thus increasing the likelihood that minorities and vulnerable people, such as the homeless, will be miscounted.America’s constitution mandates that a census take place every decade so that legislators “might rest their arguments on facts”, as James Madison put it in 1790. The government has become more reliant on this knowledge as its responsibilities have grown. In 2016 census data were used to direct some $850bn of funding for programmes such as Medicaid, food stamps, school lunches and roadbuilding. The results are also used to apportion seats in Congress, as well as by academics, genealogists and even supermarket chains deciding where to open new shops.Population counts long predate the founding fathers. Babylonians recorded their numbers on clay tiles as far back as 3800BC to work out how much food to grow. In ancient Athens administrators counted piles of stones, one added by each citizen, to gauge military capability and tax revenues. And Joseph and his pregnant wife Mary travelled from Nazareth to Bethlehem after Emperor Augustus decreed that “all the world should be registered”. By the 18th century, reliable and regular population counts were common in European countries, and enumerators (as census-takers are known) were being sent out to colonies around the world.A decennial survey of every household, as has just begun in America, is a tried and tested method. It provides a snapshot of an entire population. Citizens can state how they wish to be recorded and the resulting treasure-trove of data is publicly accessible. But the cost and scale of such an undertaking is growing. America’s previous census cost $92 per household, up from $16 in 1970 (in 2020 dollars). China mobilised an army of 6m enumerators to roam the country in 2010. The UN Population Fund calls a census “among the most complex and massive peacetime exercises a nation undertakes”.Migration and changing lifestyles are making it more difficult to reach everyone. Renters are trickier than homeowners to count reliably, because they move more often and live in less stable households. One study projected that this year’s American census could undercount the population by 1.2%, rising to more than 3.5% among black and Latino populations, who are less likely to own their home.Is there a better way? For the first time this year, Americans will be able to fill out the census online. This risks missing hard-to-reach groups such as indigenous populations and the old. It also introduces unforeseen headaches. In 2016 Australia’s census website crashed, leaving millions unable to submit their responses and venting their anger with the hashtag #censusfail.Nordic countries have ditched the unwieldy undertaking altogether, turning to other sources of information. In Sweden each citizen is given a personnummer, an identity number linked to government data on individuals’ health, employment, residence and more. These data are cross-referenced to produce statistics resembling the results of a traditional census. Denmark, Finland and Norway take the same approach. As societies share more information, wittingly or otherwise, new statistics can be produced. Mobile-phone records, for example, have been used to estimate commuting patterns. The Netherlands, meanwhile, conducts what it calls a “virtual” census. This is similar to the Nordic model, but also uses small-sample surveys to produce data not already held by the state, such as education levels and occupation.As long as each citizen has a unique identifier, such counts are cheaper to carry out—the Dutch government boasts that its census in 2011 cost just $0.10 per person—and can be done much more regularly. But the accuracy of the data is harder to guarantee. Population registers are never completely up to date and anyone not already on them will be missed. In Europe, two-thirds of countries are expected to use data from existing registers to some extent in the next round of censuses. This is up from just a quarter 20 years ago, according to analysis by Paolo Valente, a statistician at the UN.Making such a change is a slow process. Bernard Baffour, a researcher at the Australian National University, points out that it took decades for Sweden to implement a fully register-based census, partly because Swedes had to be reassured that their data were secure. As he puts it, “When a doctor asks how much you drink or smoke, are you happy for that to be linked with all the other information on you?” Frank de Zwart, a professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, also criticises register-based censuses for neglecting a key political function of censuses. For minorities such as native Americans, filling out a census is a powerful assertion of their place in society. A virtual census would deny them this opportunity. That said, self-reporting is far from perfect: 177,000 Britons implausibly claimed to be Jedi knights in the census of 2011.Even though Britain does not have identity cards, common in the rest of Europe, in 2013 the government tried to replace the census with other administrative data it already held. An outcry from MPs and statisticians forced ministers to shelve the idea. The public had rejected an attempt in 2006 to introduce identity cards, and recent scandals such as the harvesting of personal data from Facebook deepened Britons’ worries about privacy. Iain Bell, the statistician in charge of the census at the Office for National Statistics (ONS), emphasises the importance of public trust in producing official figures: “If people don’t want a single register of the population, we have to respect that and look to other sources.” Francis Maude, then a government minister, told MPs in 2014 that he hoped the next census, due to take place next year, would be the last. In 2023, the ONS will report back on whether this is achievable.Political rows over America’s census have shone a light on a function of government that most people consider only a handful of times over their lives, but the results of which affect them every day. Recording each member of every household seems outdated in the associated with big data, whether the data are held by governments or private companies. But in this sense, at least, America’s federal government is not big enough; its social-security system is too incomplete, and other information still too patchy, to replace the old-fashioned head-count. Will Mr Dillingham be the last enumerator to visit Toksook These types of? Don’t count upon this.Reuse this contentThe Trust Project <![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ]]>

If you enjoyed this post, you should read this: Thank You Page

source http://blognetweb.com/out-for-the-count-americas-census-looks-out-of-date-in-the-age-of-big-data-international/

0 notes

Text

Out for the count – America’s census looks out of date in the age of big data | International

<![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ]]> Jan 20th 2020A DOG:SLED or a snowmobile is the surest way to reach Toksook Bay in rural Alaska, where Steven Dillingham, the director of America’s census bureau, will arrive to count the first people in the country’s decennial population survey on January 21st. The task should not take long—there were only 590 villagers at the last count, in 2010—but it marks the beginning of a colossal undertaking. Everyone living in America will be asked about their age, sex, ethnicity and residence over the coming months (and some will be asked much more besides).This census has already proved unusually incendiary. An attempt by President Donald Trump to include a question on citizenship, which might have discouraged undocumented immigrants from responding, was thwarted by the Supreme Court. His administration has also been accused in two lawsuits of underfunding the census, thus increasing the likelihood that minorities and vulnerable people, such as the homeless, will be miscounted.America’s constitution mandates that a census take place every decade so that legislators “might rest their arguments on facts”, as James Madison put it in 1790. The government has become more reliant on this knowledge as its responsibilities have grown. In 2016 census data were used to direct some $850bn of funding for programmes such as Medicaid, food stamps, school lunches and roadbuilding. The results are also used to apportion seats in Congress, as well as by academics, genealogists and even supermarket chains deciding where to open new shops.Population counts long predate the founding fathers. Babylonians recorded their numbers on clay tiles as far back as 3800BC to work out how much food to grow. In ancient Athens administrators counted piles of stones, one added by each citizen, to gauge military capability and tax revenues. And Joseph and his pregnant wife Mary travelled from Nazareth to Bethlehem after Emperor Augustus decreed that “all the world should be registered”. By the 18th century, reliable and regular population counts were common in European countries, and enumerators (as census-takers are known) were being sent out to colonies around the world.A decennial survey of every household, as has just begun in America, is a tried and tested method. It provides a snapshot of an entire population. Citizens can state how they wish to be recorded and the resulting treasure-trove of data is publicly accessible. But the cost and scale of such an undertaking is growing. America’s previous census cost $92 per household, up from $16 in 1970 (in 2020 dollars). China mobilised an army of 6m enumerators to roam the country in 2010. The UN Population Fund calls a census “among the most complex and massive peacetime exercises a nation undertakes”.Migration and changing lifestyles are making it more difficult to reach everyone. Renters are trickier than homeowners to count reliably, because they move more often and live in less stable households. One study projected that this year’s American census could undercount the population by 1.2%, rising to more than 3.5% among black and Latino populations, who are less likely to own their home.Is there a better way? For the first time this year, Americans will be able to fill out the census online. This risks missing hard-to-reach groups such as indigenous populations and the old. It also introduces unforeseen headaches. In 2016 Australia’s census website crashed, leaving millions unable to submit their responses and venting their anger with the hashtag #censusfail.Nordic countries have ditched the unwieldy undertaking altogether, turning to other sources of information. In Sweden each citizen is given a personnummer, an identity number linked to government data on individuals’ health, employment, residence and more. These data are cross-referenced to produce statistics resembling the results of a traditional census. Denmark, Finland and Norway take the same approach. As societies share more information, wittingly or otherwise, new statistics can be produced. Mobile-phone records, for example, have been used to estimate commuting patterns. The Netherlands, meanwhile, conducts what it calls a “virtual” census. This is similar to the Nordic model, but also uses small-sample surveys to produce data not already held by the state, such as education levels and occupation.As long as each citizen has a unique identifier, such counts are cheaper to carry out—the Dutch government boasts that its census in 2011 cost just $0.10 per person—and can be done much more regularly. But the accuracy of the data is harder to guarantee. Population registers are never completely up to date and anyone not already on them will be missed. In Europe, two-thirds of countries are expected to use data from existing registers to some extent in the next round of censuses. This is up from just a quarter 20 years ago, according to analysis by Paolo Valente, a statistician at the UN.Making such a change is a slow process. Bernard Baffour, a researcher at the Australian National University, points out that it took decades for Sweden to implement a fully register-based census, partly because Swedes had to be reassured that their data were secure. As he puts it, “When a doctor asks how much you drink or smoke, are you happy for that to be linked with all the other information on you?” Frank de Zwart, a professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, also criticises register-based censuses for neglecting a key political function of censuses. For minorities such as native Americans, filling out a census is a powerful assertion of their place in society. A virtual census would deny them this opportunity. That said, self-reporting is far from perfect: 177,000 Britons implausibly claimed to be Jedi knights in the census of 2011.Even though Britain does not have identity cards, common in the rest of Europe, in 2013 the government tried to replace the census with other administrative data it already held. An outcry from MPs and statisticians forced ministers to shelve the idea. The public had rejected an attempt in 2006 to introduce identity cards, and recent scandals such as the harvesting of personal data from Facebook deepened Britons’ worries about privacy. Iain Bell, the statistician in charge of the census at the Office for National Statistics (ONS), emphasises the importance of public trust in producing official figures: “If people don’t want a single register of the population, we have to respect that and look to other sources.” Francis Maude, then a government minister, told MPs in 2014 that he hoped the next census, due to take place next year, would be the last. In 2023, the ONS will report back on whether this is achievable.Political rows over America’s census have shone a light on a function of government that most people consider only a handful of times over their lives, but the results of which affect them every day. Recording each member of every household seems outdated in the associated with big data, whether the data are held by governments or private companies. But in this sense, at least, America’s federal government is not big enough; its social-security system is too incomplete, and other information still too patchy, to replace the old-fashioned head-count. Will Mr Dillingham be the last enumerator to visit Toksook These types of? Don’t count upon this.Reuse this contentThe Trust Project <![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ]]>

If you enjoyed this post, you should read this: Thank You Page

source http://blognetweb.com/out-for-the-count-americas-census-looks-out-of-date-in-the-age-of-big-data-international/ source https://productreviewavoidscams.blogspot.com/2020/01/out-for-count-americas-census-looks-out.html

0 notes

Text

Out for the count – America’s census looks out of date in the age of big data | International

<![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ]]> Jan 20th 2020A DOG:SLED or a snowmobile is the surest way to reach Toksook Bay in rural Alaska, where Steven Dillingham, the director of America’s census bureau, will arrive to count the first people in the country’s decennial population survey on January 21st. The task should not take long—there were only 590 villagers at the last count, in 2010—but it marks the beginning of a colossal undertaking. Everyone living in America will be asked about their age, sex, ethnicity and residence over the coming months (and some will be asked much more besides).This census has already proved unusually incendiary. An attempt by President Donald Trump to include a question on citizenship, which might have discouraged undocumented immigrants from responding, was thwarted by the Supreme Court. His administration has also been accused in two lawsuits of underfunding the census, thus increasing the likelihood that minorities and vulnerable people, such as the homeless, will be miscounted.America’s constitution mandates that a census take place every decade so that legislators “might rest their arguments on facts”, as James Madison put it in 1790. The government has become more reliant on this knowledge as its responsibilities have grown. In 2016 census data were used to direct some $850bn of funding for programmes such as Medicaid, food stamps, school lunches and roadbuilding. The results are also used to apportion seats in Congress, as well as by academics, genealogists and even supermarket chains deciding where to open new shops.Population counts long predate the founding fathers. Babylonians recorded their numbers on clay tiles as far back as 3800BC to work out how much food to grow. In ancient Athens administrators counted piles of stones, one added by each citizen, to gauge military capability and tax revenues. And Joseph and his pregnant wife Mary travelled from Nazareth to Bethlehem after Emperor Augustus decreed that “all the world should be registered”. By the 18th century, reliable and regular population counts were common in European countries, and enumerators (as census-takers are known) were being sent out to colonies around the world.A decennial survey of every household, as has just begun in America, is a tried and tested method. It provides a snapshot of an entire population. Citizens can state how they wish to be recorded and the resulting treasure-trove of data is publicly accessible. But the cost and scale of such an undertaking is growing. America’s previous census cost $92 per household, up from $16 in 1970 (in 2020 dollars). China mobilised an army of 6m enumerators to roam the country in 2010. The UN Population Fund calls a census “among the most complex and massive peacetime exercises a nation undertakes”.Migration and changing lifestyles are making it more difficult to reach everyone. Renters are trickier than homeowners to count reliably, because they move more often and live in less stable households. One study projected that this year’s American census could undercount the population by 1.2%, rising to more than 3.5% among black and Latino populations, who are less likely to own their home.Is there a better way? For the first time this year, Americans will be able to fill out the census online. This risks missing hard-to-reach groups such as indigenous populations and the old. It also introduces unforeseen headaches. In 2016 Australia’s census website crashed, leaving millions unable to submit their responses and venting their anger with the hashtag #censusfail.Nordic countries have ditched the unwieldy undertaking altogether, turning to other sources of information. In Sweden each citizen is given a personnummer, an identity number linked to government data on individuals’ health, employment, residence and more. These data are cross-referenced to produce statistics resembling the results of a traditional census. Denmark, Finland and Norway take the same approach. As societies share more information, wittingly or otherwise, new statistics can be produced. Mobile-phone records, for example, have been used to estimate commuting patterns. The Netherlands, meanwhile, conducts what it calls a “virtual” census. This is similar to the Nordic model, but also uses small-sample surveys to produce data not already held by the state, such as education levels and occupation.As long as each citizen has a unique identifier, such counts are cheaper to carry out—the Dutch government boasts that its census in 2011 cost just $0.10 per person—and can be done much more regularly. But the accuracy of the data is harder to guarantee. Population registers are never completely up to date and anyone not already on them will be missed. In Europe, two-thirds of countries are expected to use data from existing registers to some extent in the next round of censuses. This is up from just a quarter 20 years ago, according to analysis by Paolo Valente, a statistician at the UN.Making such a change is a slow process. Bernard Baffour, a researcher at the Australian National University, points out that it took decades for Sweden to implement a fully register-based census, partly because Swedes had to be reassured that their data were secure. As he puts it, “When a doctor asks how much you drink or smoke, are you happy for that to be linked with all the other information on you?” Frank de Zwart, a professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, also criticises register-based censuses for neglecting a key political function of censuses. For minorities such as native Americans, filling out a census is a powerful assertion of their place in society. A virtual census would deny them this opportunity. That said, self-reporting is far from perfect: 177,000 Britons implausibly claimed to be Jedi knights in the census of 2011.Even though Britain does not have identity cards, common in the rest of Europe, in 2013 the government tried to replace the census with other administrative data it already held. An outcry from MPs and statisticians forced ministers to shelve the idea. The public had rejected an attempt in 2006 to introduce identity cards, and recent scandals such as the harvesting of personal data from Facebook deepened Britons’ worries about privacy. Iain Bell, the statistician in charge of the census at the Office for National Statistics (ONS), emphasises the importance of public trust in producing official figures: “If people don’t want a single register of the population, we have to respect that and look to other sources.” Francis Maude, then a government minister, told MPs in 2014 that he hoped the next census, due to take place next year, would be the last. In 2023, the ONS will report back on whether this is achievable.Political rows over America’s census have shone a light on a function of government that most people consider only a handful of times over their lives, but the results of which affect them every day. Recording each member of every household seems outdated in the associated with big data, whether the data are held by governments or private companies. But in this sense, at least, America’s federal government is not big enough; its social-security system is too incomplete, and other information still too patchy, to replace the old-fashioned head-count. Will Mr Dillingham be the last enumerator to visit Toksook These types of? Don’t count upon this.Reuse this contentThe Trust Project <![CDATA[ (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); ]]>

If you enjoyed this post, you should read this: Thank You Page

source http://blognetweb.com/out-for-the-count-americas-census-looks-out-of-date-in-the-age-of-big-data-international/

0 notes

Text

Out for the count – America’s census looks out of date in the age of big data | International

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Jan 20th 2020A DOG:SLED or a snowmobile is the surest way to reach Toksook Bay in rural Alaska, where Steven Dillingham, the director of America’s census bureau, will arrive to count the first people in the country’s decennial population survey on January 21st. The task should not take long—there were only 590 villagers at the last count, in 2010—but it marks the beginning of a colossal undertaking. Everyone living in America will be asked about their age, sex, ethnicity and residence over the coming months (and some will be asked much more besides).This census has already proved unusually incendiary. An attempt by President Donald Trump to include a question on citizenship, which might have discouraged undocumented immigrants from responding, was thwarted by the Supreme Court. His administration has also been accused in two lawsuits of underfunding the census, thus increasing the likelihood that minorities and vulnerable people, such as the homeless, will be miscounted.America’s constitution mandates that a census take place every decade so that legislators “might rest their arguments on facts”, as James Madison put it in 1790. The government has become more reliant on this knowledge as its responsibilities have grown. In 2016 census data were used to direct some $850bn of funding for programmes such as Medicaid, food stamps, school lunches and roadbuilding. The results are also used to apportion seats in Congress, as well as by academics, genealogists and even supermarket chains deciding where to open new shops.Population counts long predate the founding fathers. Babylonians recorded their numbers on clay tiles as far back as 3800BC to work out how much food to grow. In ancient Athens administrators counted piles of stones, one added by each citizen, to gauge military capability and tax revenues. And Joseph and his pregnant wife Mary travelled from Nazareth to Bethlehem after Emperor Augustus decreed that “all the world should be registered”. By the 18th century, reliable and regular population counts were common in European countries, and enumerators (as census-takers are known) were being sent out to colonies around the world.A decennial survey of every household, as has just begun in America, is a tried and tested method. It provides a snapshot of an entire population. Citizens can state how they wish to be recorded and the resulting treasure-trove of data is publicly accessible. But the cost and scale of such an undertaking is growing. America’s previous census cost $92 per household, up from $16 in 1970 (in 2020 dollars). China mobilised an army of 6m enumerators to roam the country in 2010. The UN Population Fund calls a census “among the most complex and massive peacetime exercises a nation undertakes”.Migration and changing lifestyles are making it more difficult to reach everyone. Renters are trickier than homeowners to count reliably, because they move more often and live in less stable households. One study projected that this year’s American census could undercount the population by 1.2%, rising to more than 3.5% among black and Latino populations, who are less likely to own their home.Is there a better way? For the first time this year, Americans will be able to fill out the census online. This risks missing hard-to-reach groups such as indigenous populations and the old. It also introduces unforeseen headaches. In 2016 Australia’s census website crashed, leaving millions unable to submit their responses and venting their anger with the hashtag #censusfail.Nordic countries have ditched the unwieldy undertaking altogether, turning to other sources of information. In Sweden each citizen is given a personnummer, an identity number linked to government data on individuals’ health, employment, residence and more. These data are cross-referenced to produce statistics resembling the results of a traditional census. Denmark, Finland and Norway take the same approach. As societies share more information, wittingly or otherwise, new statistics can be produced. Mobile-phone records, for example, have been used to estimate commuting patterns. The Netherlands, meanwhile, conducts what it calls a “virtual” census. This is similar to the Nordic model, but also uses small-sample surveys to produce data not already held by the state, such as education levels and occupation.As long as each citizen has a unique identifier, such counts are cheaper to carry out—the Dutch government boasts that its census in 2011 cost just $0.10 per person—and can be done much more regularly. But the accuracy of the data is harder to guarantee. Population registers are never completely up to date and anyone not already on them will be missed. In Europe, two-thirds of countries are expected to use data from existing registers to some extent in the next round of censuses. This is up from just a quarter 20 years ago, according to analysis by Paolo Valente, a statistician at the UN.Making such a change is a slow process. Bernard Baffour, a researcher at the Australian National University, points out that it took decades for Sweden to implement a fully register-based census, partly because Swedes had to be reassured that their data were secure. As he puts it, “When a doctor asks how much you drink or smoke, are you happy for that to be linked with all the other information on you?” Frank de Zwart, a professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, also criticises register-based censuses for neglecting a key political function of censuses. For minorities such as native Americans, filling out a census is a powerful assertion of their place in society. A virtual census would deny them this opportunity. That said, self-reporting is far from perfect: 177,000 Britons implausibly claimed to be Jedi knights in the census of 2011.Even though Britain does not have identity cards, common in the rest of Europe, in 2013 the government tried to replace the census with other administrative data it already held. An outcry from MPs and statisticians forced ministers to shelve the idea. The public had rejected an attempt in 2006 to introduce identity cards, and recent scandals such as the harvesting of personal data from Facebook deepened Britons’ worries about privacy. Iain Bell, the statistician in charge of the census at the Office for National Statistics (ONS), emphasises the importance of public trust in producing official figures: “If people don’t want a single register of the population, we have to respect that and look to other sources.” Francis Maude, then a government minister, told MPs in 2014 that he hoped the next census, due to take place next year, would be the last. In 2023, the ONS will report back on whether this is achievable.Political rows over America’s census have shone a light on a function of government that most people consider only a handful of times over their lives, but the results of which affect them every day. Recording each member of every household seems outdated in the associated with big data, whether the data are held by governments or private companies. But in this sense, at least, America’s federal government is not big enough; its social-security system is too incomplete, and other information still too patchy, to replace the old-fashioned head-count. Will Mr Dillingham be the last enumerator to visit Toksook These types of? Don’t count upon this.Reuse this contentThe Trust Project (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

If you enjoyed this post, you should read this: Shruti Trikanad: Governing ID: Introducing our Evaluation Framework

source http://blognetweb.com/out-for-the-count-americas-census-looks-out-of-date-in-the-age-of-big-data-international/ source https://ungendered-yarn.tumblr.com/post/190436098725

0 notes

Text

Out for the count – America’s census looks out of date in the age of big data | International

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Jan 20th 2020A DOG:SLED or a snowmobile is the surest way to reach Toksook Bay in rural Alaska, where Steven Dillingham, the director of America’s census bureau, will arrive to count the first people in the country’s decennial population survey on January 21st. The task should not take long—there were only 590 villagers at the last count, in 2010—but it marks the beginning of a colossal undertaking. Everyone living in America will be asked about their age, sex, ethnicity and residence over the coming months (and some will be asked much more besides).This census has already proved unusually incendiary. An attempt by President Donald Trump to include a question on citizenship, which might have discouraged undocumented immigrants from responding, was thwarted by the Supreme Court. His administration has also been accused in two lawsuits of underfunding the census, thus increasing the likelihood that minorities and vulnerable people, such as the homeless, will be miscounted.America’s constitution mandates that a census take place every decade so that legislators “might rest their arguments on facts”, as James Madison put it in 1790. The government has become more reliant on this knowledge as its responsibilities have grown. In 2016 census data were used to direct some $850bn of funding for programmes such as Medicaid, food stamps, school lunches and roadbuilding. The results are also used to apportion seats in Congress, as well as by academics, genealogists and even supermarket chains deciding where to open new shops.Population counts long predate the founding fathers. Babylonians recorded their numbers on clay tiles as far back as 3800BC to work out how much food to grow. In ancient Athens administrators counted piles of stones, one added by each citizen, to gauge military capability and tax revenues. And Joseph and his pregnant wife Mary travelled from Nazareth to Bethlehem after Emperor Augustus decreed that “all the world should be registered”. By the 18th century, reliable and regular population counts were common in European countries, and enumerators (as census-takers are known) were being sent out to colonies around the world.A decennial survey of every household, as has just begun in America, is a tried and tested method. It provides a snapshot of an entire population. Citizens can state how they wish to be recorded and the resulting treasure-trove of data is publicly accessible. But the cost and scale of such an undertaking is growing. America’s previous census cost $92 per household, up from $16 in 1970 (in 2020 dollars). China mobilised an army of 6m enumerators to roam the country in 2010. The UN Population Fund calls a census “among the most complex and massive peacetime exercises a nation undertakes”.Migration and changing lifestyles are making it more difficult to reach everyone. Renters are trickier than homeowners to count reliably, because they move more often and live in less stable households. One study projected that this year’s American census could undercount the population by 1.2%, rising to more than 3.5% among black and Latino populations, who are less likely to own their home.Is there a better way? For the first time this year, Americans will be able to fill out the census online. This risks missing hard-to-reach groups such as indigenous populations and the old. It also introduces unforeseen headaches. In 2016 Australia’s census website crashed, leaving millions unable to submit their responses and venting their anger with the hashtag #censusfail.Nordic countries have ditched the unwieldy undertaking altogether, turning to other sources of information. In Sweden each citizen is given a personnummer, an identity number linked to government data on individuals’ health, employment, residence and more. These data are cross-referenced to produce statistics resembling the results of a traditional census. Denmark, Finland and Norway take the same approach. As societies share more information, wittingly or otherwise, new statistics can be produced. Mobile-phone records, for example, have been used to estimate commuting patterns. The Netherlands, meanwhile, conducts what it calls a “virtual” census. This is similar to the Nordic model, but also uses small-sample surveys to produce data not already held by the state, such as education levels and occupation.As long as each citizen has a unique identifier, such counts are cheaper to carry out—the Dutch government boasts that its census in 2011 cost just $0.10 per person—and can be done much more regularly. But the accuracy of the data is harder to guarantee. Population registers are never completely up to date and anyone not already on them will be missed. In Europe, two-thirds of countries are expected to use data from existing registers to some extent in the next round of censuses. This is up from just a quarter 20 years ago, according to analysis by Paolo Valente, a statistician at the UN.Making such a change is a slow process. Bernard Baffour, a researcher at the Australian National University, points out that it took decades for Sweden to implement a fully register-based census, partly because Swedes had to be reassured that their data were secure. As he puts it, “When a doctor asks how much you drink or smoke, are you happy for that to be linked with all the other information on you?” Frank de Zwart, a professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, also criticises register-based censuses for neglecting a key political function of censuses. For minorities such as native Americans, filling out a census is a powerful assertion of their place in society. A virtual census would deny them this opportunity. That said, self-reporting is far from perfect: 177,000 Britons implausibly claimed to be Jedi knights in the census of 2011.Even though Britain does not have identity cards, common in the rest of Europe, in 2013 the government tried to replace the census with other administrative data it already held. An outcry from MPs and statisticians forced ministers to shelve the idea. The public had rejected an attempt in 2006 to introduce identity cards, and recent scandals such as the harvesting of personal data from Facebook deepened Britons’ worries about privacy. Iain Bell, the statistician in charge of the census at the Office for National Statistics (ONS), emphasises the importance of public trust in producing official figures: “If people don’t want a single register of the population, we have to respect that and look to other sources.” Francis Maude, then a government minister, told MPs in 2014 that he hoped the next census, due to take place next year, would be the last. In 2023, the ONS will report back on whether this is achievable.Political rows over America’s census have shone a light on a function of government that most people consider only a handful of times over their lives, but the results of which affect them every day. Recording each member of every household seems outdated in the associated with big data, whether the data are held by governments or private companies. But in this sense, at least, America’s federal government is not big enough; its social-security system is too incomplete, and other information still too patchy, to replace the old-fashioned head-count. Will Mr Dillingham be the last enumerator to visit Toksook These types of? Don’t count upon this.Reuse this contentThe Trust Project (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

If you enjoyed this post, you should read this: Shruti Trikanad: Governing ID: Introducing our Evaluation Framework

source http://blognetweb.com/out-for-the-count-americas-census-looks-out-of-date-in-the-age-of-big-data-international/ source https://ungendered-yarn.tumblr.com/post/190436098725

0 notes

Text

issuu

The Australian Citizenship Test is an integral part of becoming a citizen of Australia. Taking the time to consider the content of the test, study the study booklet, and determine what is expected of the test-taker, is a worthwhile endeavor. By following some simple tips, such as creating a study plan, reading the questions carefully, and writing practice exams, individuals will ensure they are prepared to pass the Australian Citizenship Test with flying colors. Read more!!

#australia citizenship test#australian citizenship test practice#citizenship test#australian citizenship practice test#australian citizenship practice tests our common bond#Australian Citizenship test online#Australian Citizenship test 2023#australian citizenship practice exams#australian citizenship test example#Australian citizenship test answers#Australian citizenship test booklet#value of australia quiz test

0 notes

Text

Out for the count – America’s census looks out of date in the age of big data | International

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); Jan 20th 2020A DOG:SLED or a snowmobile is the surest way to reach Toksook Bay in rural Alaska, where Steven Dillingham, the director of America’s census bureau, will arrive to count the first people in the country’s decennial population survey on January 21st. The task should not take long—there were only 590 villagers at the last count, in 2010—but it marks the beginning of a colossal undertaking. Everyone living in America will be asked about their age, sex, ethnicity and residence over the coming months (and some will be asked much more besides).This census has already proved unusually incendiary. An attempt by President Donald Trump to include a question on citizenship, which might have discouraged undocumented immigrants from responding, was thwarted by the Supreme Court. His administration has also been accused in two lawsuits of underfunding the census, thus increasing the likelihood that minorities and vulnerable people, such as the homeless, will be miscounted.America’s constitution mandates that a census take place every decade so that legislators “might rest their arguments on facts”, as James Madison put it in 1790. The government has become more reliant on this knowledge as its responsibilities have grown. In 2016 census data were used to direct some $850bn of funding for programmes such as Medicaid, food stamps, school lunches and roadbuilding. The results are also used to apportion seats in Congress, as well as by academics, genealogists and even supermarket chains deciding where to open new shops.Population counts long predate the founding fathers. Babylonians recorded their numbers on clay tiles as far back as 3800BC to work out how much food to grow. In ancient Athens administrators counted piles of stones, one added by each citizen, to gauge military capability and tax revenues. And Joseph and his pregnant wife Mary travelled from Nazareth to Bethlehem after Emperor Augustus decreed that “all the world should be registered”. By the 18th century, reliable and regular population counts were common in European countries, and enumerators (as census-takers are known) were being sent out to colonies around the world.A decennial survey of every household, as has just begun in America, is a tried and tested method. It provides a snapshot of an entire population. Citizens can state how they wish to be recorded and the resulting treasure-trove of data is publicly accessible. But the cost and scale of such an undertaking is growing. America’s previous census cost $92 per household, up from $16 in 1970 (in 2020 dollars). China mobilised an army of 6m enumerators to roam the country in 2010. The UN Population Fund calls a census “among the most complex and massive peacetime exercises a nation undertakes”.Migration and changing lifestyles are making it more difficult to reach everyone. Renters are trickier than homeowners to count reliably, because they move more often and live in less stable households. One study projected that this year’s American census could undercount the population by 1.2%, rising to more than 3.5% among black and Latino populations, who are less likely to own their home.Is there a better way? For the first time this year, Americans will be able to fill out the census online. This risks missing hard-to-reach groups such as indigenous populations and the old. It also introduces unforeseen headaches. In 2016 Australia’s census website crashed, leaving millions unable to submit their responses and venting their anger with the hashtag #censusfail.Nordic countries have ditched the unwieldy undertaking altogether, turning to other sources of information. In Sweden each citizen is given a personnummer, an identity number linked to government data on individuals’ health, employment, residence and more. These data are cross-referenced to produce statistics resembling the results of a traditional census. Denmark, Finland and Norway take the same approach. As societies share more information, wittingly or otherwise, new statistics can be produced. Mobile-phone records, for example, have been used to estimate commuting patterns. The Netherlands, meanwhile, conducts what it calls a “virtual” census. This is similar to the Nordic model, but also uses small-sample surveys to produce data not already held by the state, such as education levels and occupation.As long as each citizen has a unique identifier, such counts are cheaper to carry out—the Dutch government boasts that its census in 2011 cost just $0.10 per person—and can be done much more regularly. But the accuracy of the data is harder to guarantee. Population registers are never completely up to date and anyone not already on them will be missed. In Europe, two-thirds of countries are expected to use data from existing registers to some extent in the next round of censuses. This is up from just a quarter 20 years ago, according to analysis by Paolo Valente, a statistician at the UN.Making such a change is a slow process. Bernard Baffour, a researcher at the Australian National University, points out that it took decades for Sweden to implement a fully register-based census, partly because Swedes had to be reassured that their data were secure. As he puts it, “When a doctor asks how much you drink or smoke, are you happy for that to be linked with all the other information on you?” Frank de Zwart, a professor at Leiden University in the Netherlands, also criticises register-based censuses for neglecting a key political function of censuses. For minorities such as native Americans, filling out a census is a powerful assertion of their place in society. A virtual census would deny them this opportunity. That said, self-reporting is far from perfect: 177,000 Britons implausibly claimed to be Jedi knights in the census of 2011.Even though Britain does not have identity cards, common in the rest of Europe, in 2013 the government tried to replace the census with other administrative data it already held. An outcry from MPs and statisticians forced ministers to shelve the idea. The public had rejected an attempt in 2006 to introduce identity cards, and recent scandals such as the harvesting of personal data from Facebook deepened Britons’ worries about privacy. Iain Bell, the statistician in charge of the census at the Office for National Statistics (ONS), emphasises the importance of public trust in producing official figures: “If people don’t want a single register of the population, we have to respect that and look to other sources.” Francis Maude, then a government minister, told MPs in 2014 that he hoped the next census, due to take place next year, would be the last. In 2023, the ONS will report back on whether this is achievable.Political rows over America’s census have shone a light on a function of government that most people consider only a handful of times over their lives, but the results of which affect them every day. Recording each member of every household seems outdated in the associated with big data, whether the data are held by governments or private companies. But in this sense, at least, America’s federal government is not big enough; its social-security system is too incomplete, and other information still too patchy, to replace the old-fashioned head-count. Will Mr Dillingham be the last enumerator to visit Toksook These types of? Don’t count upon this.Reuse this contentThe Trust Project (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

If you enjoyed this post, you should read this: Shruti Trikanad: Governing ID: Introducing our Evaluation Framework

source http://blognetweb.com/out-for-the-count-americas-census-looks-out-of-date-in-the-age-of-big-data-international/

0 notes

Text

#australiancitizenship#australiancitizenshiptest#australiancitizenship2023#australianvalues#australiacitizenshippractice#mycitizenshiptests#australiancitizenshipstudy#australiancitizenshipguide#australiancitizenshipexam#australiancitizenshipquestions#australian citizenship test#citizenship test#australian citizenship#australia#immigration#australian values

0 notes

Text

#australian citizenship test#australia#citizenship test#australian citizenship#australia citizenship test#immigration#australian citizenship practice test

0 notes