#Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A group of scientists warned Monday of the greatly underestimated risk of a collapse of ocean currents in the Atlantic which could have catastrophic consequences for the Nordic countries as the region's leaders gathered in Iceland. In an open letter addressed to the Nordic Council, which is meeting this week in Iceland's capital Reykjavik, the scientists said they wanted to bring attention "to the serious risk of a major ocean circulation change in the Atlantic."

Continue Reading.

#Science#Environment#Climate Crisis#Global Warming#Atlantic Ocean#AMOC#Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this EcoWatch story:

More than 40 scientists have written an open letter warning of a potential “tipping point” for the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) in the Arctic.

The letter to the Nordic Council of Ministers encourages countries in the region to prevent global heating from causing AMOC’s collapse, which could lead to sudden changes in weather patterns and damage to ecosystems.

“Science increasingly confirms that the Arctic region is a ‘ground zero’ for tipping point risks and climate regulation across the planet. In this region, the Greenland Ice Sheet, the Barents sea ice, the boreal permafrost systems, the subpolar gyre deep-water formation and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) are all vulnerable to major, interconnected nonlinear changes,” the scientists said in the letter. “The AMOC, the dominant mechanism of northward heat transport in the North Atlantic, determines life conditions for all people in the Arctic region and beyond and is increasingly at risk of passing a tipping point.”

AMOC is an ocean current system that brings warm water to the North Atlantic, giving Europe its mild climate, reported Reuters.

AMOC’s collapse would raise sea levels in the Atlantic, make the Northern Hemisphere cooler, reduce precipitation in North America and Europe and change monsoon patterns in Africa and South America, the United Kingdom’s Met Office said, as reported by Reuters.

“If Britain and Ireland become like northern Norway, (that) has tremendous consequences. Our finding is that this is not a low probability,” said signatory of the letter professor Peter Ditlevsen of the University of Copenhagen, as Reuters reported. “This is not something you easily adapt to.”

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gulf stream could collapse for first time in 12,000 years as early as 2025, study suggests Jul 25 2023

New analysis estimates timescale for collapse between 2025 and 2095, with central estimate of 2050

"The Gulf Stream system could collapse as soon as 2025, a new study suggests. The shutting down of the vital ocean currents, called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (Amoc) by scientists, would bring catastrophic climate impacts."

READ MORE https://www.irishtimes.com/environment/climate-crisis/2023/07/25/gulf-stream-could-collapse-as-early-as-2025-study-suggests/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resolution Effects on Ocean Circulation

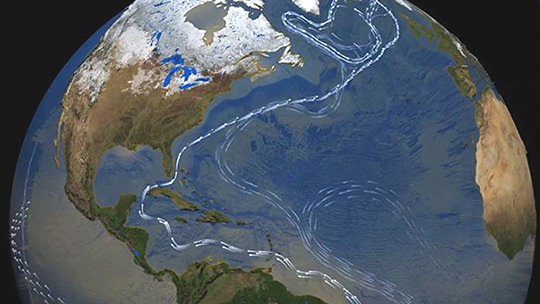

The Gulf Stream current carries warm, salty water from the Gulf of Mexico northeastward. In the North Atlantic, this water cools and sinks and drifts southwestward, emerging centuries later in the Southern Ocean. Known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), this circulation is critical, among other things, to Europe's temperate climate. (Image credit: illustration - Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, simulations - R. Gou et al.; research credit: R. Gou et al.; via APS Physics) Read the full article

#CFD#circulation#climate change#computational fluid dynamics#flow visualization#fluid dynamics#numerical simulation#ocean currents#oceanography#physics#science

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

@phiammacdeo-blog

Atlantic Ocean is headed for a tipping point − once melting glaciers shut down the Gulf Stream, we would see extreme climate change within decades, study shows

Superstorms, abrupt climate shifts and New York City frozen in ice. That’s how the blockbuster Hollywood movie “The Day After Tomorrow” depicted an abrupt shutdown of the Atlantic Ocean’s circulation and the catastrophic consequences. While Hollywood’s vision was over the top, the 2004 movie raised a serious question: If global warming shuts down the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation,…

View On WordPress

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please read

I've been protesting since i was two. I have memorised the chants, the speeches, the songs, the same arguments over and over and *over* again. I have signed over 500 petitions, i have attended over 150 marches, I have presented over 10 speeches personally. I don't remember when I learned about climate change because i always knew, so why didn't others?

I remember asking my Mother when i was around eight where she first learnt about it. When she was in year 8, back in 89-90. She said to me "I remember my teacher explaining it to us and thinking 'why isn't anyone doing anything'" She told me it's not that we don't have the answers, its we don't have the materials.

Now I know that is code for "the government is refusing to fund this" or "The government doesn't believe this is an issue" ect ect. Again and again, a new issue that needs to be solved or address or fixed before "we can focus on climate change"

Let me tell you ***You can not fight every battle*** But I try to. This latest "stunt" [Aliens aren't real] by the USA is yet another distraction from the biggest issue, The Atlantic ocean is facing a collapse.

Due to amount of cold water coming from the melted Greenland Ice sheets, It will cause the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) to collapse and shut down.

The last time this happened was around 15,000-14,500 years ago, at the end of the last ice age. It lead to a collapse of weather cycles, temperatures plunge and spike, ecosystems to collaspe.

If it collapses, La Niña could become the norm for Australia.

You can do something. I know because I've done something. So do it.

https://www.zmescience.com/science/major-atlantic-ocean-current-could-collapse-due-to-climate-change/

https://www.gzeromedia.com/gzero-north/warming-seas-have-scientists-on-alert

https://edition.cnn.com/2023/07/20/world/greenland-ice-sheet-melt-sea-level-rise-climate/index.html

https://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2023/07/what-is-happening-in-the-atlantic-ocean-to-the-amoc/

https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/151638/wasting-away-again-in-greenland

#climate change#clean energy#climate strike#climate emergency#climate action#climate catastrophe#climate crisis#climate justice#climate activism#greenland ice sheet#global warming#aliens#USA#politics

243 notes

·

View notes

Text

We, Black Curatorial, Kwanda, Twossaints, Black Eats London & West India Cinema Corporation have come together to fundraise for people affected by Hurricane Beryl across the West Indies. As West Indian people it is imperative that we support each other and ourselves in the building back of our communities, this is a duty. Hurricane Beryl has devastated hundreds of communities in the West Indies. This is not a freak storm, this is a direct impact of climate crisis in the region - fuelled and sustained by overconsumption and emissions in the Global North. The ocean waters are 4 degrees warmer than expected at this time of year, this has directly affected the speed and ferocity of the hurricane at the beginning of this year's hurricane season. To understand what the importance of AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) is for Hurricane season in the Caribbean and globally please watch this video. The impact of this hurricane is very much being felt, "90% of homes on Union Island had been destroyed", according to Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves. We’re fundraising for people and charities across Barbados, St Vincent & the Grenadines, Grenada and those affected across the region. The money raised will go towards helping local fishermen in Barbados to buy new boats, support roofing and housing materials for people in Carriacou, Union and Grenada and well as St Vincent to rebuild their livelihoods and homes. We are working collectively to disseminate these funds across the region ensuring they reach grassroots communities and people directly. The Hurricane is now a category 5 and on its way to Jamaica. We urge everyone to pray for its weakening and for the people currently effected by Beryl's peril. Please continue to share and donate to those affected! If you have any questions please email us.

WHERE ARE THE DONATIONS GOING?

This fund exists to go directly to grassroots organisations providing support for those across the following countries: Barbados St Vincent & the Grenadines Carriacou Petite Martinique Union Grenada Jamaica

HOW WILL THEY BE PROCESSED AND ADMINISTERED?

We are working with Kwanda to help disseminate the funds to the existing groups they work with in the affected countries. Black Curatorial work across Barbados and Jamaica administering funds for creatives via the Fly Me Out Fund our process of sending money via transfer is already set up to support and facilitate this fund's dissemination.

WHO'S INVOLVED?

Black Curatorial Kwanda West India Cinema Corporation Twossaints Black Eats London

#west indies#caribbean#hurricane beryl#barbados#st vincent and the grenadines#petite martinique#carriacou#grenada#jamaica#union island#hurricane relief#mutual aid#gofundme#donate if you can#donation boost#disaster recovery

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists this week warn that the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current (aka AMOC, contains the Gulf Stream) is closer than they previously predicted, as early as 2025.

This is bad and will lead to ripples in climate, weather patterns, local "normal" temperatures, storm severity, ocean oxygenation and fishery productivity (hello phrase "fish die-offs" 😭), and sea level that will disrupt life as we know it and cannot be reversed in this century or maybe (likely) for centuries to come.

(You can check the Wikipedia page for more information.).

Scream at someone about this.

Go here -- https://www.whitehouse.gov/contact/ -- or here -- https://www.usa.gov/elected-officials. Start typing. Feel free to use the template I'm putting under the "read more." Press send. Repeat if you have the energy. Ily if you do it even once. Thank you, and keep fighting the good fight!

Dear <NAME OF OFFICIAL>,

<OPTIONAL SENTENCE OR TWO TO INTRODUCE YOURSELF. Say why climate change matters to you. Say if you're frightened. Say if you're depressed. Say if you're anxious. Make it personal.>

This week a study was released (https://www.cnn.com/2023/07/25/world/gulf-stream-atlantic-current-collapse-climate-scn-intl/index.html, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-39810-w) showing that the collapse of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation is far closer than scientists had previously thought. When this current stops, it will have far-reaching impacts on sea level, weather, storm patterns, and fishery production that will be irreversible for a century or far longer.

I am deeply worried about the future. We need climate change ACTION now, not just voluntary incentive programs. Please take action to improve our electrical grid, transition our power plants to clean fuels, transition to clean modes of transportation, and tax carbon emissions.

Sincerely,

<YOUR NAME HERE>

#AMOC#honestly this is not surprising to anyone with pattern recognition#those extremely high gulf of mexico temperatures?#the cold blob off the south of greenland?#those are all signs#bad bad signs#climate change#advocacy#climate action#climate advocacy#global warming#mid atlantic current#gulf of mexico#contact your elected representatives#action#take action#climate crisis#tipping points

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

climate change blackpill megapost

there are several climate tipping points identified in the united nations intergovernmental panel on climate change sixth assessment report (chapter 3, specifically). tipping points refer to critical thresholds in a system that, when exceeded, can lead to a significant change in the state of the system, often with an understanding that the change is irreversible. they are:

the greenland ice sheet

the west antarctic ice sheet

the atlantic meridional overturning current

monsoon systems

el niño-southern oscillation

tropical rainforests

northern boreal forests

thawing permafrost

extreme heat

current (2022) global warming of ~1.1°C above preindustrial temperatures already lies within the lower end of some tipping point uncertainty ranges. several tipping points may be triggered in the paris agreement range of 1.5 to <2°C global warming, with many more likely at the 2 to 3°C of warming expected on current policy trajectories.

greenland's ice sheet is in disequilibrium and we are committed to 2-3 meters of sea level rise from its melt alone in the next 200 years.

greenland's ice sheets have been melting twice as fast in the last twenty years as they were during the previous century.

rapid increase in the rate of melting of the west antarctic ice sheet is unavoidable.

the west antarctic ice sheet is retreating twice as fast as previously predicted

because of widespread seawater intrusion beneath the grounded ice of the thwaites glacier.

the west antarctic ice sheet will raise sea levels by four meters when it melts.

this is causing the atlantic meridional overturning current to collapse.

the gulf stream (aka amoc) is weakening. 99% confidence. measured volume through the florida straits has declined by 4% in the past 40 years

the gulf stream will collapse between 2025 and 2095. 95% confidence.

the north atlantic is four standard deviations above its historic temperatures.

when the amoc collapses, the arctic sea-ice pack will extend down to 50°n. the vast expansion of the northern hemispheric sea-ice pack amplifies further northern hemispheric cooling via the ice-albedo feedback.

a collapse of the atlantic meridional overturning circulation would have substantial impacts on global precipitation patterns, especially in the vulnerable tropical monsoon regions in west africa, east asia, and india where they will experience shorter wet seasons and longer dry seasons with an overall decrease in precipitation

although recent studies indicate that the amazon will experience net benefit from the collapse of the amoc with cooler temperatures and increased rainfall

increased el niño intensity will increase the frequency and severity of droughts in the amazon rainforest.

even if we were able to stabilize global mean temperature at 1.5º C, el niño intensity will continue to increase for a century

and the amazon rainforest is currently in the worst drought on record, which may indicate it has passed its threshold to maintain its own wet climate.

while widespread and persistent warming of permafrost has been observed in polar regions and at high elevations since about 1980, the highest permafrost temperatures in the instrumental record were recorded in 2018–2019 (data from 2019-2020)

as of 2019 the southern extent of permafrost had receded northwards by 30 to 80km

soil fires in the canadian arctic are burning the peat underground and melting the permafrost. stat from the study 70% of recorded area of arctic peat affected by burning over the past forty years has occurred in the last eight and 30% of it was in 2020 alone.

nasa finds that tundra releases plumes of methane in the wake of wildfires.

in 2023 eight times more land burned in canada than average.

russian siberia experienced a similarly massive fire season in 2021.

a methane source we weren’t expecting was warmer, wetter conditions to increase organic decomposition in tropical wetlands which is releasing ever increasing amounts of methane.

we have been experiencing exponential rise in atmospheric methane since 2006. historical data indicates that we may have entered into an ice age termination event fueled by these methane releases.

we have been over 1.5º C above pre-industrial temperatures since the beginning of 2023.

this may be because of the extreme el niño conditions of the 2023-24 cycle, but breaches of 1.5°C for a month or a year are early signs of getting perilously close to exceeding the long-term limit

and the world meteorological organization expects us to permanently break 1.5º C of warming from pre-industrial levels within the next five years.

the united nations environmental programme (unep) emissions gap report found that current fossil fuel extraction commitments leave no credible path to keeping warming below 1.5º C. based on current policies we will experience 2.8ºC of warming by 2100. even if all current pledges were implemented and followed through with (which they never have been), we will only be able to limit that to 2.4-2.6ºC of warming.

#this isn't even touching on the anthropological or ecological impacts#just the physics of the predicament#climate change#climate crisis#climate emergency#ipcc#extinction rebellion#last generation#just stop oil#it's the end of the world as we know it

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this story from EcoWatch:

Current climate policies are putting the world at a high risk of critical Earth system components reaching tipping points, even if global temperatures return to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial average following a period of overshoot.

However, a new study has found that, if global heating is quickly reversed, these risks could be minimized.

The human-caused climate crisis has the potential to cause a destabilization of large-scale elements of Earth systems like ocean circulation patterns, ice sheets and components of the global biosphere. In the study, the researchers examined the risks that future emissions scenarios and current mitigation levels posed to four interconnected tipping elements, a press release from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) said.

The research team determined the risks of tipping for destabilizing a minimum of one of four central climate elements: the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the Greenland Ice Sheet, the Amazon Rainforest and the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) — the Atlantic Ocean’s main ocean current system. All four of these contribute to the regulation of the stability of the planet’s climate. Sudden changes to these biophysical systems can be triggered by global heating, leading to irreversible outcomes.

The report’s analysis explains how important it is to stick to the climate targets laid out in the Paris Agreement, while emphasizing that our current choices will impact the planet for centuries or even millennia.

“Our results show that to effectively limit tipping risks over the coming centuries and beyond, we must achieve and maintain net-zero greenhouse gas emissions. Following current policies this century would commit us to a high tipping risk of 45% by 2300, even if temperatures are brought back to below 1.5°C after a period of overshoot,” said Tessa Möller, co-lead author of the study and a researcher with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK)’s Integrated Climate Impacts Research Group, in the press release.

The researchers discovered that tipping risks become substantial by 2300 for several of the future emissions scenarios they assessed. If the average global temperature does not return to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100 — even if net-zero greenhouse gas emissions are reached — there will be a tipping risk of as much as 24 percent by 2300. This means that in roughly one-quarter of the scenarios that do not return to less than 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, a minimum of one of the tipping elements they considered will have tipped.

“We see an increase in tipping risk with every tenth of a degree of overshoot above 1.5°C. If we were to also surpass 2°C of global warming, tipping risks would escalate even more rapidly. This is very concerning as scenarios that follow currently implemented climate policies are estimated to result in about 2.6°C global warming by the end of this century,” said co-lead author Annika Ernest Högner, also with PIK, in the press release.

“Only a swift warming reversal after overshoot can effectively limit tipping risks. This requires achieving at least net-zero greenhouse gases. Our study underscores that this global mitigation objective, enshrined in Article 4 of the Paris Agreement, is vital for planetary stability,” said Carl Schleussner, one of the authors of the study and a leader with the IIASA Integrated Climate Impacts Research Group, in the press release.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

So much on this planet depends on a simple matter of density. In the Atlantic Ocean, a conveyor belt of warm water heads north from the tropics, reaching the Arctic and chilling. That makes it denser, so it sinks and heads back south, finishing the loop. This system of currents, known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, moves 15 million cubic meters of water per second.

In recent years, researchers have suggested that because of climate change, the AMOC current system could be slowing down and may eventually collapse. A paper published yesterday in the journal Nature Communications warns that the collapse of the AMOC isn’t just possible, but imminent. By this team’s calculations, the circulation could shut down as early as 2025, and no later than 2095.

That’s a tipping point that would come much sooner than anyone thought. “We got scared by our own results,” says Susanne Ditlevsen, a statistician at the University of Copenhagen and coauthor of the new paper. “We checked and checked and checked and checked, and I do believe that they're right. Of course, we might be wrong, and I hope we are.” But there’s vigorous debate in the scientific community over just how quickly the AMOC might decline, and how best to even figure that out.

It’s abundantly clear to researchers that the Arctic is warming up to four and a half times faster than the rest of the planet. Arctic ice is melting at a pace of about 150 billion metric tons per year, says Marlos Goes, an oceanographer from the University of Miami and NOAA's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory who was not involved with the new paper. Greenland’s ice sheet is also rapidly declining, injecting more freshwater into the sea. That deluge of freshwater is less dense than saltwater, meaning less water sinks and less power goes into the AMOC conveyor belt.

The consequences would be brutal and global. Without these warm waters, weather in Europe would get significantly colder—more like that of similar latitudes in Canada and the northern United States. “In model simulations, the collapse of the AMOC cools the North Atlantic and warms the South Atlantic, which may result in drastic precipitation changes throughout the world,” Goes says. “There would be changes in storm patterns over the continental areas, affecting the monsoon systems. Therefore, a future AMOC shutdown could bring massive migration, impacting ecological and agricultural production, and fish population displacement.”

Ditlevsen did her team’s calculation by using measurements of Atlantic sea surface temperatures as a proxy for the AMOC. These readings go all the way back to the 1870s, thanks to measurements taken by ship crews. This meant researchers could compare temperatures before and after the start of the wide-scale burning of fossil fuels and the ensuing changes to the climate.

Because the AMOC system involves warm water heading north from the tropics, if the circulation is slowing down, you’d expect to find cooler temperatures in the North Atlantic over time. And indeed, that’s what Ditlevsen’s group found, once they compensated for the overall warming of the world’s oceans due to climate change. “When it is established that the sea surface temperature record is the fingerprint of the AMOC, we can calculate the early warning signals of the forthcoming collapse and extrapolate to the tipping point,” says University of Copenhagen climate scientist Peter Ditlevsen, coauthor of the new paper. (The Ditlevsens are siblings.)

The result echoes previous studies finding early warning signals in the circulation, says Stefan Rahmstorf, who studies the AMOC current system at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “As always in science, a single study provides limited evidence, but when multiple approaches lead to similar conclusions, this must be taken very seriously, especially when we're talking about a risk that we really want to rule out with 99.9 percent certainty,” says Rahmstorf. “The scientific evidence now is that we can't even rule out crossing a tipping point already in the next decade or two.”

Still, scientists don’t agree about whether sea surface temperature (SST) is a good indicator of the health of this massively consequential circulation. “Fundamentally, I am deeply skeptical that SST is actually a proxy of AMOC,” says climate scientist Hali Kilbourne, who studies the current system at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. “But there's certainly a school of thought of people who think it's the best thing going—and it may be the best thing going right now. I don't think we have a good alternative, which is why people are using it."

“I really question whether [SST] is an adequate proxy for AMOC itself,” agrees Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research. “But the trouble is there aren't really adequate measurements.”

The core of the issue is that sea surface temperatures are just one component of the AMOC system; other factors also help determine Atlantic temperatures. Warm waters flowing north have an effect, but so does the atmosphere touching the water. “There's a lot of what we call air-sea interactions—the heat exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean,” Kilbourne says. “And that's not at all related to ocean circulation.”

“This SST fingerprint, although sensitive to the AMOC, is not solely driven by it, so these changes may be overestimated,” agrees Goes, the oceanographer from the University of Miami and NOAA. “Current climate models do not give a strong probability of the collapse of the AMOC this century.”

The beauty of the SST dataset is that it stretches back 150 years, so scientists can see longer-term trends in temperatures. However, those early shipboard measurements were made by people hauling buckets of water aboard and sticking a thermometer in—not exactly the precision that modern science demands. “It is not ideal, but it’s the best we can do,” says Peter Ditlevsen, “since we need measurements to go back to the pre-industrial era to assess the natural state of the AMOC, before it began slowing down toward the collapse.”

Satellite measurements of SST began in the late 1970s, providing much better coverage across oceans. And it wasn’t until 20 years ago that scientists deployed a dedicated AMOC sensor array, known as RAPID, which also measures current velocities and salinity—another factor that influences the density of water. By comparing this modern data to the historical SST data, Peter Ditlevsen says, they can compensate for the influence of the atmosphere on the sea surface, isolating the signal of the AMOC system.

When the RAPID array went online, the assumption was that it’d take 40 years to get an idea of whether the current system was in decline. “It's just hard to tease apart, because we really don't know what the intrinsic timescales of AMOC are,” says Nicholas Foukal, an assistant scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who wasn’t involved in the new paper. “We haven't had an AMOC collapse in the past 20 years, so it’s like trying to predict a hurricane—having never seen a hurricane.”

Since RAPID started operating, scientists have seen a good amount of variability. “We've been directly measuring AMOC since 2004, and we don't have any evidence of long-term decline,” says Foukal. “The first six years, there was a very strong decline. And people jumped on that, saying that it's declining, and we have observational evidence of it. But since then, it has recovered.”

Scientists also use models to simulate how the current system might change as the climate does. Compared to the studies indicating a slowdown and eventual collapse of the circulation, models indicate more stability, says Oluwayemi Garuba, a climate scientist who studies ocean-atmosphere interactions at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. “Observations are showing more statistically significant early-warning signals of a collapse of the AMOC, whereas most models are not showing that,” says Garuba. “So, it could be that the overturning circulation in models is just more stable than in observation, as earlier studies have suggested.”

Going forward, Greenland will be a major wildcard. Last week, scientists reported how they used ice cores from an abandoned military base to determine that around 400,000 years ago, northwest Greenland was ice-free. Back then, temperatures were about the same as they are today, yet atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations were far lower. That raises the alarm that the decline of Greenland’s ice sheet could accelerate. If it does, the melt would load the north Atlantic with astonishing amounts of freshwater, fast-tracking the decline of the AMOC and adding many feet to sea levels.

It’s complexity and uncertainty all the way down. “The fact that, with continued warming, AMOC will slow down is a very robust result. The uncertainty—and where science still needs to figure things out—is when,” Kilbourne. “But I kind of think that by the time we figure out when, it'll already have happened.”

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists detect sign that a crucial ocean current is near collapse

By Sarah Kaplan

The Atlantic Ocean’s sensitive circulation system has become slower and less resilient, according to a new analysis of 150 years of temperature data — raising the possibility that this crucial element of the climate system could collapse within the next few decades.

Scientists have long seen the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC, as one of the planet’s most vulnerable “tipping elements” —meaning the system could undergo an abrupt and irreversible change, with dramatic consequences for the rest of the globe. Under Earth’s current climate, this aquatic conveyor belt transports warm, salty water from the tropics to the North Atlantic, and then sends colder water back south along the ocean floor. But as rising global temperatures melt Arctic ice, the resulting influx of cold freshwater has thrown a wrench in the system — and could shut it down entirely.

The study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications suggests that continued warming will push the AMOC over its “tipping point” around the middle of this century. The shift would be as abrupt and irreversible as turning off a light switch, and it could lead to dramatic changes in weather on either side of the Atlantic.

“This is a really worrying result,” said Peter Ditlevsen, a climate physicist at the University of Copenhagen and lead author of the new study. “This is really showing we need a hard foot on the brake” of greenhouse gas emissions.

Ditlevsen’s analysis is at odds with the most recent report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which drew on multiple climate models and concluded with “medium confidence” that the AMOC will not fully collapse this century.

Other experts on the AMOC also cautioned that because the new study doesn’t present new observations of the entire ocean system — instead, it is extrapolating about the future based on past data from a limited region of the Atlantic — its conclusions should be taken with a grain of salt.

“The qualitative statement that AMOC has been losing stability in the last century remains true even taking all uncertainties into account,” said Niklas Boers, a scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. “But the uncertainties are too high for a reliable estimate of the time of AMOC tipping.”

The new study adds to a growing body of evidence that this crucial ocean system is in peril. Since 2004, observations from a network of ocean buoys has showed the AMOC getting weaker — though the limited time frame of that data set makes it hard to establish a trend. Scientists have also analyzed multiple “proxy” indicators of the current’s strength, including microscopic organisms and tiny sediments from the seafloor, to show the system is in its weakest state in more than 1,000 years.

For their analysis, Peter Ditlevsen and his colleague Susanne Ditlevsen (who is Peter’s sister) examined records of sea surface temperatures going back to 1870. In recent years, they found, temperatures in the northernmost waters of the Atlantic have undergone bigger fluctuations and taken longer to return to normal. These are “early warning signals” that the AMOC is becoming critically unstable, the scientists said — like the increasingly wild wobbles before a tower of Jenga blocks starts to fall.

Susanne Ditlevsen, a statistician at the University of Copenhagen, then developed an advanced mathematical model to predict how much more wobbling the AMOC system can handle. The results suggest that the AMOC could collapse any time between now and 2095, and as early as 2025, the authors said.

The consequences would not be nearly as dire as they appear in the 2004 sci-fi film “The Day After Tomorrow,” in which a sudden shutdown of the current causes a flash freeze across the northern hemisphere. But it could lead to a drop in temperatures in northern Europe and elevated warming in the tropics, Peter Ditlevsen said, as well as stronger storms on the East Coast of North America.

Marilena Oltmanns, an oceanographer at the National Oceanography Center in Britain, noted in a statement that the temperatures in the north Atlantic are “only one part of a highly complex, dynamical system.” Though her own research on marine physics supports the Ditlevsens’ conclusion that this particular region could reach a tipping point this century, she is wary of linking that transition to a full-scale change in Atlantic Ocean circulation.

Yet the dangers of even a partial AMOC shutdown mean any indicators of instability are worth investigating, said Stefan Rahmstorf, another oceanographer at the Potsdam Institute who was not involved in the new study.

“As always in science, a single study provides limited evidence, but when multiple approaches lead to similar conclusions this must be taken very seriously,” he said. “The scientific evidence now is that we can’t even rule out crossing a tipping point already in the next decade or two.”

Chris Mooney contributed to this report.

[Washington Post]

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ever since some of the earliest projections of climate change were made back in the 1970s, they have been remarkably accurate at predicting the rate at which global temperatures would rise. For decades, climate change has proceeded at roughly the expected pace, says David Armstrong McKay, a climate scientist at the University of Exeter, in England. Its impacts, however, are accelerating—sometimes far faster than expected.

For a while, the consequences weren’t easily seen. They certainly are today. The Southwest is sweltering under a heat dome. Vermont saw a deluge of rain, its second 100-year storm in roughly than a decade. Early July brought the hottest day globally since records began—a milestone surpassed again the following day. “For a long time, we were within the range of normal. And now we’re really not,” Allegra LeGrande, a physical-research scientist at Columbia University, told me. “And it has happened fast enough that people have a memory of it happening.”

In fact, a growing number of climate scientists now believe we may be careening toward so-called tipping points, where incremental steps along the same trajectory could push Earth’s systems into abrupt or irreversible change—leading to transformations that cannot be stopped even if emissions were suddenly halted. “The Earth may have left a ‘safe’ climate state beyond 1°C global warming,” Armstrong McKay and his co-authors concluded in Science last fall. If these thresholds are passed, some of global warming’s effects—like the thaw of permafrost or the loss of the world’s coral reefs—are likely to happen more quickly than expected. On the whole, however, the implications of blowing past these tipping points remain among climate change’s most consequential unknowns: We don’t really know when or how fast things will fall apart.

Some natural systems, if upended, could herald a restructuring of the world. Take the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica: It’s about the size of Florida, with a protruding ice shelf that impedes the glacier’s flow into the ocean. Although the ice shelf's overall melt is slower than originally predicted, warm water is now eating away at it from below, causing deep cracks. At a certain point, that melt may progress enough to become self-sustaining, which would guarantee the glacier’s eventual collapse. How that plays out will help determine how much sea levels will rise—and thus the future of millions of people.

The fate of the Thwaites Glacier could be independent of other tipping points, such as those affecting mountain-glacier loss in South America, or the West African monsoon. But some tipping points will interact, worsening one another’s effects. When melt from Greenland’s glaciers enters the ocean, for example, it alters an important system of currents called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. The AMOC is like a conveyor belt, drawing warm water from the tropics north. The water’s salinity increases as it evaporates, which, among other factors, makes it sink and return south along the ocean floor. As more glacial fresh water enters the system, that conveyor belt will weaken. Right now it’s the feeblest it’s been in more than 1,000 years.

A shutdown of that ocean current could dramatically alter phenomena as varied as global weather patterns and crop yields. Messing with complex systems is chilling precisely because there are so many levers: If the temperature of the sea surface changes, precipitation over the Amazon might too, contributing to its deforestation, which in turn has been linked to snowfall on the Tibetan plateau. We may not even realize when we start passing points of no return—or if we already have. “It’s kind of like stepping into a minefield,” Armstrong McKay said. “We don’t want to find out where these things are by triggering them.”

One grim paper that came out last year, titled “Climate End Game,” mapped out some of the potential catastrophes that could follow a “tipping cascade,” and considered the possibility that “a sudden shift in climate could trigger systems failures that unravel societies across the globe.” Chris Field, the director of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and a contributor to several IPCC reports, warned that “at some point, the impacts of the climate crisis may become so severe that we lose the ability to work together to deliver solutions.”

James Hansen, one of the early voices on climate, says that measures to mitigate the crisis may now, ironically, be contributing to it. He published a working paper this spring suggesting that a reduction in sulfate aerosol particles—or the air pollution associated with burning coal and the global shipping industry—has contributed to warmer temperatures. That’s because these particles cause water droplets to multiply, which brightens clouds and reflects solar heat away from the planet’s surface. Though the paper has not been peer-reviewed, Hansen predicts that environmentally minded policies to reduce these pollutants will likely cause temperatures to rise by 2 degrees Celsius by 2050.

Even before the climate gets to that point, we may face a dramatic uptick in climate-related disasters, says William Ripple, a distinguished professor of ecology at Oregon State University and the lead author of a recent commentary on the “risky feedback loops” connecting climate-driven systems. There’s a sense of awe—in the original meaning of inspiring terror or dread—at witnessing such sweeping changes play out across the landscape. “Many scientists knew these things would happen, but we’re taken aback by the severity of the major changes we’re seeing,” Ripple said. Armstrong McKay likened the challenge of being a climate scientist in 2023 to that faced by medical professionals: “You put a certain emotional distance between you and the work in order to do the work effectively,” he said, “that can be difficult to maintain.”

Although it may be too late to avert some changes, others could still be staved off by limiting emissions. LeGrande said she worries that talking about tipping points may encourage people to think that any further action now is futile. In fact, the opposite is true, Ripple said. “Scientifically, everything we do to avoid even a tenth of a degree of temperature increase makes a huge difference.”

5 notes

·

View notes