#Apalachicola River

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sunrise, Apalachicola River, Florida. (c) John B. Spohrer, Jr. :: [My Forgotten Coast]

* * * *

The spiritual task of life is to feed hope. Hope is not something to be found outside of us. It lies in the spiritual life we cultivate within. The whole purpose of wrestling with life is to be transformed into the self we are meant to become, to step out of the confines of our false securities and allow our creating God to go on creating. In us.

-- Joan D. Chittister

#Apalachicola River#John B. Spohrer Jr.#My Forgotten Coast#our creating God#Joan D. Chittister#quotes#hope#the inner

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

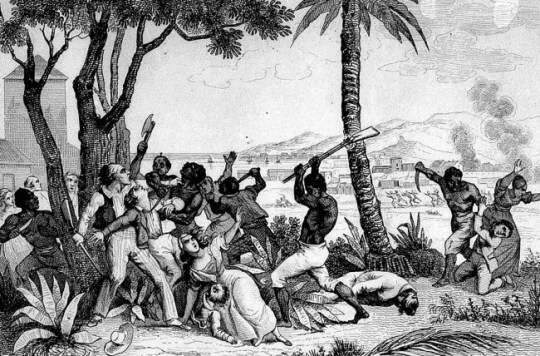

270 people dead in an instant at "Negro Fort"

Readers: Boom! A red-hot cannonball, shot from the middle of the Apalachicola River, slammed into a sprawling fort full of Indians and runaway slaves. In a flash, 270 people died.

Here’s more about this tragedy with help from Dale Cox, author of The Fort at Prospect Bluff.

The bluff, on a slow curve 20 miles north of the Gulf of Mexico, offers a clear view up the half-mile-wide Apalachicola, a major artery through the South two centuries ago. Whoever would control this piece of land would control shipping along the river.

The tragedy of the "Negro Fort" stemmed from a multinational tug-of-war for the Spanish-held territories of West Florida and East Florida.

In 1815, during the War of 1812, the British, at war with America, built a fort with bastions 15 feet high and 18 feet thick as a base to recruit escaped slaves and Indians. A year later, the British abandoned it, leaving artillery and military supplies. Blacks and Indians stayed.

About 5 a.m. on July 27, the gunboats carrying Clinch and his men could see the Union Jack and a red flag called "the bloody flag'' - a universal sign of no surrender. From inside, a 32-pound cannonball flew toward the Americans. Clinch returned fire. He launched four cannonballs and fired shots - cannonballs heated red hot for maximum carnage. The first one hit the ammunition pile.

"The explosion was awful and the scene horrible beyond description," Clinch wrote later.

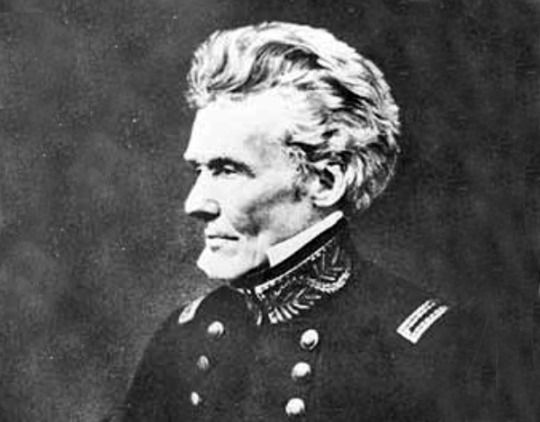

In 1818, during the First Seminole War, Jackson, again, went downriver on a search-and-destroy mission for Seminole villages. He instructed Lt. James Gadsden to build a fort where the former British fort had been. He named it for Gadsden who held the fort despite Spanish protests until Spain ceded Florida to the United States in 1821. It was mostly forgotten until the Civil War; Confederate troops occupied it until driven out by malaria.

The fort then fell to neglect. The state took charge of 78 acres in 1961 to create Fort Gadsden State Park. It later came under the management of the U.S. Forest Service and was renamed Prospect Bluff Historic Sites.

#Florida History: 270 people dead in an instant at “Negro Fort”#Negro Fort#prospect bluff#fort gadsden#Apalachicola River#seminole war#first seminole war#civil war#spanish#Black history in florida

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apalachicola River Linocut Print, "Apalachicola Magesty", Handmade Linocut Print by

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adan Salazar, a member of the cabalgata (a parade of horseback riders), travels 20 miles from the neighboring town of Múzquiz to celebrate Juneteenth in 2018 in Nacimiento, the generational home of the Black Seminoles who escaped the threat of slavery in the United States.

Just Across The Border, This Mexican Community Also Celebrates Juneteenth

The “Southern Underground Railroad” helped formerly enslaved people reach freedom in northern Mexico. One village here has observed Juneteenth or “Día de los Negros” for 150 years.

— By Taryn White | Photographs By Luján Agusti | June 17, 2021

In northern Mexico’s Coahuila State there’s a village where locals celebrate Juneteenth by eating traditional Afro-Seminole foods, dancing to norteña music, and practicing capeyuye—hand-clapped hymnals sung by enslaved peoples who traveled the Southern Underground Railroad to freedom.

It may seem unlikely that this holiday would be honored in a small village at the base of the Sierra Madre range, but Nacimiento de los Negros—meaning “Birth of the Blacks”—became a haven for the Mascogos, descendants of Black Seminoles who escaped the brutality of the antebellum South and settled in Mexico.

Now, long after the group came to Nacimiento in 1852, a new challenge remains for the Mascogos: Keeping their culture and traditions alive. In a country of approximately 130 million people, where 1.3 million identify as Afro-descendants, there are only a few hundred Mascogos. Decades of navigating ongoing drought conditions in Mexico, currently affecting 84 percent of the country, have devasted the village’s agriculture-based economy. Younger community members have little choice but to seek new opportunities elsewhere.

A young girl dons on the Traditional Attire—Polka-Dot Dress, Apron, and Handkerchief—worn by Mascogos Women during Juneteenth celebrations in Nacimiento.

But there is hope—both in the strength of Mascogo identity and in the growing recognition of Juneteenth (June 19), a day that marks the freedom of enslaved people in Texas at the end of the United States Civil War and is considered by some to be America’s “Second Independence Day.” On June 17, President Joseph Biden Signed a Bill that recognizes Juneteenth as a federal holiday. Such recognition could also strengthen the visibility of this historic community nearly 2,000 miles from Washington. D.C.

Juneteenth Becomes A Federal Holiday! President Joe Biden signs the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act. Evan Vucci/AP, June 17, 2021

The Southern Underground Railroad

Hundreds of enslaved people fled from southern plantations to live among the Seminoles in Florida Territory during the mid-to-late 18th century. Spain granted freedom to enslaved people who escaped to Florida under their rule, but the U.S. did not recognize this agreement.

In 1821, the Spanish ceded Florida to the U.S., sending the Seminoles and their Black counterparts farther south onto reservations near the Apalachicola River. Andrew Jackson, territorial governor of Florida, ordered an attack on Angola, a village built by Black Seminoles and other free Blacks near Tampa Bay. Dozens of escaped slaves were captured and sold or returned to their previous place of enslavement; many others were killed.

From left to right: Jose, Aton, and Sebastian, members of the horseback parade, arrive in Nacimiento’s nogalera (a Park Surrounded by Walnut Trees) as part of Día de Los Negros.

Nearly a decade later, Jackson, now president, signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 into law, which required Native tribes in the southeast to relocate to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. Seminole and Black leaders opposed the forced removal, later leading to the Second Seminole War (1835–42). Halfway through the confrontation, the Seminoles called for a truce and agreed to move—if their Black allies were allowed to move safely as well.

The negotiations quickly fell through, and the war resumed, but the relocation of nearly 4,000 Seminoles and 800 Black Seminoles, also known as the Trail of Tears, had already begun.

Southern Underground Railroad

As many as 5,000 enslaved African Americans escaped to freedom in Mexico, after that country outlawed slavery in 1829. While most traveled on their own or in small groups, some were helped by an informal network of free African Americans, Mexicans, Tejanos, and German settlers. Motivations for assisting the refugees were complex—some did so out of sympathy, while others were paid to transport them across the border.

Katie Armstrong, NG Staff. Source: Thomas Mareite, Abolitionists, Smugglers and Scapegoats: Assistance Networks for Fugitive Slaves in the Texas-Mexico Borderlands, 1836–1861, Cahiers du MIMMOC; National Park Service, National Trails Intermountain Region

By 1845, most Seminoles had been relocated to Indian Territory, where many Black Seminoles who joined the journey were kidnapped and sold into slavery in Arkansas and Louisiana. Faced with continuous hardships in Indian Territory, members of the Black Seminoles, Seminole Indians, and Kickapoo tribe left Indian Territory in 1849 for Mexico, where slaves could live freely.

Mexico officially abolished slavery in September 1829, and in 1857, Mexico amended its constitution to reflect that all people are born free.

Alice Baumgartner, assistant professor of history at the University of Southern California, says that the Seminoles’ and Black Seminoles’ move to Mexico was part of a much longer history of Mexican authorities recruiting Native peoples who had been forced from their homelands to help defend Mexico’s northern border. In exchange for fighting, they would receive 70,000 acres of land in northern Coahuila as well as livestock, money, and agricultural tools.

“That alternative was far from perfect,” she says, “but it was an alternative nonetheless.”

Juneteenth—In Mexico And The U.S.

Even though the Emancipation Proclamation declared enslaved people in the Confederacy free on January 1, 1863, word had not fully spread to geographically isolated Texas, where slaveholders refused to comply with the federal orders.

It wasn’t until the last battle of the war when Union troops arrived in Galveston, Texas—a full two-and-a-half years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed—that many enslaved people knew they were free.

One year later, freedmen in Texas organized “Jubilee Day” to commemorate the date, initially holding church-centered gatherings that provided oral history lessons on slavery. Today, the holiday, which is officially recognized in more than 47 states and the District of Columbia, typically includes barbecues, street festivals, parades, religious services, dancing, and sipping red drinks—the last to symbolize the bloodshed of African Americans.

Left: Josue, who is of Mascogo descent, honors the traditions of his community for Juneteenth, which now a federal holiday in the U.S. Right: Jennie Hidalgo was crowned the Queen of the Jineteada (the town’s pageant) for Nacimiento’s 2018 Juneteenth celebration.

Left: Gustavo wears the traditional dress for men during Juneteenth. Right: Jennifer celebrates Juneteenth with her community. After the parade of horseback riders arrives into town, Mascogo descendants gather under shade trees to barbecue and boil ears of corn over wood fires.

María Esther Hammack, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin, believes the first Juneteenth celebrations in Nacimiento may have been held as early as the 1870s due to military families traveling back and forth from Nacimiento to Fort Clark in Brackettville, Texas. From 1870 to 1914, Black Seminoles were enlisted by the U.S Army as Seminole Indian “scouts” to defend against other Native American tribes as the U.S. Government expanded into West Texas.

“People in el Nacimiento had already been enjoying freedom for many years, since their arrival in Mexico in 1850,” says Hammack. “[But] Juneteenth celebration in Coahuila, Mexico began as a means to show solidarity with their brethren in the U.S.,” says Hammack. Black Seminoles still living in Brackettville drive 160 miles south to celebrate Juneteenth with the Mascogos in Nacimiento.

While many details of the earliest celebrations have been lost to time, today’s traditions are a vibrant testament to Mascogo culture. On “Día de Los Negros,” women wearing traditional polka-dot dresses, aprons, and handkerchiefs assemble at the nogalera (a park surrounded by walnut trees) at dawn to begin cooking the communal meal. The cabalgata (a parade of horseback riders) begin their 20-mile journey from the neighboring town of Múzquiz, while the elders lead the community in clap-accompanied spirituals such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” Dancing to live music and playing bingo, a popular pastime in the town, are also musts.

By noon, the cabalgata arrives at the nogalera, and the townspeople enjoy traditional Afro-Seminole and Mexican dishes, such as corn on the cob, tetapún (sweet potato bread), pumpkin empanadas, pan de mortero (mortar bread), soske (corn-based atole), and asado (slowly cooked pork in hot peppers).

After a quick rest, the Mascogos reconvene at night for a party in the town’s plaza, where they dance the night away.

Threats To The Mascogo Culture

With more and more Mascogo descendants leaving Nacimiento for other parts of Mexico and the U.S., Dulce Herrera, a sixth-generation Mascogo and great-granddaughter of Lucia Vazquez Valdez—one of the last surviving negros limpios (pure Blacks)—fears the traditions of her culture will be lost.

She hopes to preserve them by teaching the younger generation of Mascogos the traditional songs and gastronomy of the community. Herrera is also working with her mother, Laura, and great-grandmother to raise the awareness of Mascogo heritage in Mexico.

Joseph stands with his horse’s whip. Currently, around 70 families live in Nacimiento and are dedicated to farming and cattle and goat ranching.

“Negros Mascogos is one of the most invisible Afro-descendant communities in Mexico,” she says, citing incidences in which community members were asked for official identification when visiting neighboring towns because “they think we are not Mexican.”

Her efforts have not been in vain. In May 2017, the governor of Coahuila signed a decree recognizing the Mascogos as Indigenous people of Coahuila.

As a result, Herrera and Valdez were able to secure federal funding for huertos familiares (community gardens) to assist community members with planting and selling their crops.

Travelers to Nacimiento can visit the small Museo Comunitario Tribu Negros Mascogos, which contains local artwork and exhibits related to Mascogo history. In 2020, the community also opened a restaurant, El Manà de Cielito, which serves local cuisine, and a hostel, Hospedaje Mascogos. Future plans include boosting cultural tourism by teaching community members to sell embroidered textiles, traditional handicrafts, and organic food as well as developing trails for walking, hiking, and horseback riding.

#Slavery#Underground Railroad#Native Americans 🇺🇸#Festivals#Cultural Conservation#Cultural Tourism#American 🇺🇸 Civil War#History & Culture

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the British evacuated Florida in the spring of 1815, they left a well-constructed and fully-armed fort on the Apalachicola River in the hands of their allies, about 300 African Americans and 30 Seminole and Choctaw Indians. News of “Negro Fort” attracted as many as 300 Black fugitives and 30 Choctaw Indians who settled in the surrounding area.

Under the command of an African American man named Garson and a Choctaw chief (whose name is unknown), the inhabitants of Negro Fort not only protected the community. The heavily armed fort became a symbol of Black Independence and a threat to the slave system.

In March of 1816, under mounting pressure from Georgia slaveholders, General Andrew Jackson petitioned the Spanish Governor of Florida to destroy the settlement. At the same time, he instructed Major General Edmund P. Gaines, commander of the military forces “in the Creek nation,” to destroy the fort and “restore the stolen negroes and property to their rightful owners.”

On July 27, 1815, the US military launched an all-out attack under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Duncan Clinch, with support from a naval convoy commanded by Sailing Master Jairus Loomis.

Ashot from the American forces entered the opening to the Fort’s powder magazine, igniting an explosion that destroyed the fort and its occupants.

Garson and the Choctaw chief, among the few who survived the carnage, were handed over to the Creek, who shot Garson and scalped the chief. Other survivors were returned to slavery.

Fort Gadsden was constructed over the site of the ruins of Negro Fort. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some of his photos! (From top: Adam's Ranch, Big Gully 1, Chassahowitzka River, Apalachicola River 1, Conservation 5)

More of his photos: https://clydebutcher.com/photographs/

This is so wholesome

93K notes

·

View notes

Text

in local news...

biden's ban on new old drilling developments is great news but my community has not had word that drilling proposed in calhoun county will be affected by this

the apalachicola river basin is really important environmentally and economically, it is an almost untouched beautiful wilderness

oil spills in it would not only be a disaster for wildlife in the area, leaks into the florida aquifer would affect drinking water of a lot of different counties near it and any stress would all but kill the oyster industry that many people in the apalachicola area heavily rely on, its a poor area that could really be turned upside down if even one thing went wrong

really the point of this post is to remind people to focus on your local issues, what affects those around you, the ban on new developments is great, but we cant be sure that the fight is over for everyone everywhere, know what happens near home

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Devastating Rainfall from Hurricane Helene

Hurricane Helene intensified as it approached Florida’s Big Bend in fall 2024, ultimately making landfall as a Category 4 storm at 11:10 p.m. Eastern Time on September 27. Even while its center was still over the Gulf of Mexico, the hurricane had begun producing devastating outcomes on land. A predecessor rain event and then the main storm system brought heavy precipitation to southern Appalachia starting on September 25. Deadly and destructive flooding occurred as a result in eastern Tennessee, western Virginia, and North Carolina, among other areas.

This map shows rainfall accumulation over the three-day period ending at 7:59 p.m. Eastern Time (23:59 Universal Time) on September 27, 2024. These data are remotely sensed estimates that come from IMERG (the Integrated Multi-Satellite Retrievals for GPM), a product of the GPM (Global Precipitation Measurement) mission, and may differ from ground-based measurements. For instance, IMERG data are averaged across each pixel, meaning that rain-gauge measurements within a given pixel can be significantly higher or lower than the average.

In Asheville, North Carolina, a total of 13.98 inches (35.52 centimeters) of rain fell from September 25 to 27, according to National Weather Service records. The storm swamped neighborhoods, damaged roads, caused landslides, knocked out electricity and cell service, and forced many residents to evacuate to temporary shelters. Record flood crests were observed on multiple rivers in the state. Flooding was widespread across the southern Appalachians; preliminary rainfall totals neared or exceeded 10 inches (25 centimeters) in parts of Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia.

On the coast of Florida, the heaviest rainfall was concentrated west of the storm’s center, in and around the town of Apalachicola. For hurricanes in the gulf, heavy rainfall typically occurs east of the storm’s center, where counterclockwise rotation brings in the most moisture from the water body. In the case of Helene, a frontal boundary over the Florida Panhandle interacted with the circulation to concentrate the highest totals west of the center, noted Steve Lang, a research meteorologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Parts of the Florida coast receiving less rain were not spared from flooding, however. Several Gulf Coast cities and towns, including Cedar Key and Tampa, were affected by storm surge.

NASA Disasters Response Coordination System has activated to support agencies responding to the storm, including FEMA and the Florida Division of Emergency Management. The team will be posting maps and data products on its open-access mapping portal as new information becomes available about flooding, power outages, precipitation totals, and other topics.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using IMERG data from the Global Precipitation Mission (GPM) at NASA/GSFC. Story by Lindsey Doermann.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hurricane Helene makes landfall in Florida as a catastrophic Category 4 storm.

Hurricane Helene has made landfall in Florida's Big Bend region as a catastrophic storm, battering the area with winds exceeding 130 mph and posing a threat of a potentially "unsurvivable" 20-foot storm surge along with heavy rainfall.

Weather Forecast For 32827 - Orlando FL:

Major Hurricane Helene made landfall in Florida's Big Bend region as a catastrophic Category 4 cyclone, unleashing hurricane-force winds and threatening a potentially "unsurvivable" 20-foot storm surge along with heavy rainfall.

Helene struck around Taylor County, Florida, between Tallahassee and Tampa, with its effects felt hundreds of miles away. At least two fatalities were reported in Wheeler County, Georgia, where a mobile home was damaged amid numerous Tornado Warnings.

The storm surge was severe enough to prompt water rescues from the Big Bend to Southwest Florida, with reports of mobile homes floating in the coastal town of Steinhatchee.

Power outages have surged as Hurricane Helene’s winds batter Florida. Over a million residents in the Sunshine State were left without power as wind gusts approached or even surpassed hurricane-force levels. St. Petersburg recorded a gust of 82 mph, while Sarasota experienced a wind gust of 74 mph.

Climate and Average Weather Year Round in 79936 El Paso TX:

https://www.behance.net/gallery/202335507/Weather-Forecast-For-79936-El-Paso-TX

Significant outages were also reported in Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.

FOX Weather's Ian Oliver reported that the surge rapidly submerged streets around St. Pete Beach on Thursday evening, even with high tide still several hours away.

Further south, in a community called Sunset Beach, local fire rescue announced they could no longer respond to service calls due to the flooding.

Clearwater Beach experienced its highest surge since at least the Superstorm of 1993, reaching over 7 feet.

The storm surge continued to pose a serious threat as the system moved up the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Due to Helene's massive size, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) warned of a significant risk of life-threatening storm surge along the entire west coast of the Florida Peninsula and the Big Bend region.

The highest inundation from Hurricane Helene was forecasted to reach up to 20 feet of storm surge flooding from Carrabelle to the Suwannee River in Florida. Areas such as Apalachicola and Chassahowitzka were expected to experience storm surges of 10-15 feet.

youtube

The National Hurricane Center (NHC) warned that a "catastrophic and deadly storm surge" is likely along parts of the Florida Big Bend coast, with inundation potentially reaching 20 feet above ground level and accompanied by destructive waves. The National Weather Service in Tallahassee described the anticipated storm surge into Apalachee Bay as "catastrophic and potentially unsurvivable."

Helene's effects will extend well beyond the coastal regions of the Big Bend, with hurricane-force gusts expected across Tallahassee and into Georgia as the storm moves inland overnight into Friday morning. The storm's size and speed mean it will retain its strength further inland than most hurricanes.

Although Helene was downgraded to a Category 2 hurricane within an hour of making landfall, its impacts are anticipated to persist for several days. Significant rainfall could lead to widespread and potentially catastrophic flash flooding across the Southeast.

During the hurricane, the Florida Highway Patrol reported a serious accident on Interstate 4 in Tampa that resulted in a fatality.

A video from the Florida Department of Transportation showed a highway sign dislodged and resting on a vehicle.

Troopers have not disclosed the cause of the crash but urged residents to remain at home until the worst of the weather has passed.

See more:

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-80133

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-80134

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-80135

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-80136

https://weatherusa.app/zip-code/weather-80137

0 notes

Text

Review of East Florida in the Revolutionary Era, 1763-1785, by George Kotlik

A few years ago I wrote a history of the British colony of West Florida (Fourteenth Colony), a forgotten entity which existed on the Gulf Coast from 1763 to 1781. The colony stretched from the Mississippi River in the west to the Apalachicola River in the east, comprising a territory that today includes portions of four Gulf Coast States. As I discovered in my research and subsequent…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Sunrise, Apalachicola River, Florida. (c) John B. Spohrer, Jr.

[My Forgotten Coast]

* * * * *

Intuitively, we know that it is important to spend time in solitude. We even start looking forward to this strange period of uselessness. This desire for solitude is often the first sign of prayer, the first indication that the presence of God’s Spirit no longer remains unnoticed. As we empty ourselves of our many worries, we come to know not only with our mind but also with our heart that we never were really alone, that God’s Spirit was with us all along.

--Henri J.M. Nouwen

[h/t Candace Chellew]

#Apalachicola River#Florida#John B. Spoher Jr.#sunrise#The Forgotten Coast#Henri J.M. Nouwen#Candace Chellew#quotes

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of ‘Negro Fort’ – Inside America's Forgotten Slave Rebellion - MilitaryHistoryNow.com

A year after the Battle of New Orleans, runaway slaves armed by the British occupied a stockade in Spanish Florida. The so called “Negro Fort” became a mecca for other fugitives from Southern plantations. In 1816, the U.S. Army arrived to crush the settlement. (Image source: WikiCommons)

“The Battle of the ‘Negro Fort,’ marks a critical moment when the federal government took a decisive stance in support of slavery and its expansion.”

By Matt Clavin

THE TIDAL MARSHES of Florida’s Apalachicola River were still under the authority of the Spanish crown in 1816, yet the events that took place there would go on to become a forgotten yet tragic chapter in the long and bloody history of American slavery.

It was during that year that an army of fugitive slaves, armed with foreign weaponry and united by dreams of freedom, would fight and die against a legion of American troops and allied Creek Indians dispatched by a future U.S. president bent on their destruction.

The Battle of the ‘Negro Fort’ marks a critical moment when the federal government took a decisive stance in support of slavery and its expansion.

What would become known as Negro Fort actually sprung from the War of 1812, one of the United States’ most misunderstood conflicts. During the contest’s third and final summer, Britain landed hundreds of troops on Florida’s Gulf Coast in preparation of an invasion of the southern United States.

Still Spanish territories at the time, East Florida and West Florida were neutral in the second war between the American Republic and the United Kingdom. Yet, the uncontested arrival of British troops there suggested the local authorities had ostensibly sided with the redcoats.

Americans’ fears of a Spanish-British alliances only increased when a detachment of Royal Marines erected a sizeable fort on the eastern shore of the Apalachicola River in the Florida Panhandle. Commanders of the new outpost then called upon Native Americans and fugitive African American slaves from across the region to join the British at the fort and together take up arms against the United States. Eventually, more than a thousand Creek, Choctaw, and Seminole Indians, along with several hundred runaways from southern plantations, accepted the invitation.

Following the final ratification of the Treaty of Ghent in the spring of 1815, the British withdrew their forces from Florida. With their powerful allies suddenly gone, most of the Indians gathered at the Apalachicola fort returned to their homes. But the hundreds of fugitive slaves inside the stockade had no place to go and so remained at the abandoned British post. And with the fort’s massive earthworks, wooden palisades and stone buildings at their disposal, along with an arsenal of hundreds of muskets, swords, bayonets and dozens of cannon, the runaways chose to remain there come what may.

Under an informal system of government that can best be described as martial law, this militant black community organized daily for its defence. At the same time, it established important relationships with the neighbouring Choctaws, Creeks, and Seminoles, who provided food and other sustenance in return for weapons and ammunition.

Negro fort was, in a word, formidable.

One British officer who, following the Treaty of Ghent, set out to assist some of the fugitive’s former owners regain their valuable property offered a curt assessment of fort’s inhabitants.

“The blacks are very violent & say they will die to a man rather than return.”

In the coming weeks and months, Hawkins and a number of prominent frontier citizens and officials flooded Washington with reports of rebellious slaves and their savage Indian allies running wild across the southern frontier. The accounts were almost entirely exaggerated.

Although clashes between Indians and settlers on disputed lands throughout the American south were commonplace in the early 19th Century, aside from inspiring an exodus of fugitive slaves from the southern states into Florida, the Negro Fort posed no threat to the United States.

None of this stopped the commander of the United States’ southern army, General Jackson, from taking bold and aggressive action against the settlement.

Through a careful and calculating correspondence, Jackson ordered General Edmund Gaines, a hero of the War of 1812, invade Florida with 100 regulars, destroy the fort and return all of its black inhabitants to their American and Spanish owners. To ensure an American victory with as few friendly casualties as possible, Jackson secured the assistance of hundreds of Creek warriors by promising them a cash reward of as much as $50 dollars a head for every black slave returned to captivity.

Over the course of the next two weeks, hundreds of pro-American Creek warriors clashed with black rebels in the dense woods surrounding the fort, which at times descended into bloody hand-to-hand combat.

With American troops watching from a safe distance, the number of casualties went unrecorded—though it must have been considerable.

When a failed sortie by the fort’s defenders was repulsed, an American eyewitness suspected it was only a ruse.

“Many circumstances convinced us,” army doctor Marcus Buck wrote to his father, “that most of them determined never to be taken alive.”

With a pause in the ground fighting, American army and navy vessels on the river exchanged cannonfire with the fort’s defenders for several days.

The bombardment continued to the morning of July 27, when a heated cannonball, or “hotshot,” fired from U.S. Gunboat 154 flew over walls of Negro Fort’s massive inner citadel, landing directly on a gunpowder magazine.

The response of American officials to the destruction of Negro Fort was muted, largely because the entire campaign was illegal. After all, with neither congressional nor executive authority, the United States armed forces had invaded a foreign territory.

By contrast, southern slave owners hailed the battle’s outcome as the dawning of a new day. A Georgia writer expressed this view when reporting “the capture of the Negro and Indian Fort, on Apalachicola.” He explained that because of the efforts of his “brave countrymen,” the southern and western frontiers were now free of the “predatory incursions” posed by black and Indian bandits “whose numbers were daily augmenting; and whose strength and resources presented a fearful aspect to our peaceful borders.”

Within two years of the Battle of Negro Fort, Jackson and the American army again invaded Florida. The resulting First Seminole War would be the first of three wars between the United States and Florida’s black and Indian population who simply refused to submit to their northern American neighbours.

Though Negro Fort survived for only a year, its memory endured in the hearts and minds of hundreds of its inhabitants who had abandoned the outpost prior to its destruction. By fleeing to the Florida peninsula and aligning with the Seminole Indians, most of these former slaves carved out difficult but free lives on the outer edges of the American republic.

As many as one hundred of them were even more fortunate, finding not only freedom but peace and tranquility in the West Indies. By boarding trading vessels and escaping to the Bahama Islands several years after the Battle of Negro Fort, they completed the improbable journey from American slaves to British subjects.

#The Battle of ‘Negro Fort’ – Inside America's Forgotten Slave Rebellion#florida#negro fort#negro abraham#Freedmen#seminole indians#florida enslaved#history of slave settlements in florida

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

A River Runs Through It, 2021, oil, acrylic, resin, aluminum, fishing line, fishing hooks, wood, nails, cigarette butts, graphite, glass flakes, lipstick, hinge, ink, canvas on shaped panel, by Chloe Chiasson © The artist. Courtesy Albertz Benda Gallery

The Worm Charmers! A Florida Family Coaxes Earthworms From The Forest Floor

— June 04, 2024 | By Michael Adno

A Hint Of Blue On The Horizon meant morning was coming. And as they have for the past fifty-four years, Audrey and Gary Revell stepped out their screen door, walked down a ramp, and climbed into their pickup truck. Passing a cup of coffee back and forth, they headed south into Tate’s Hell—one corner of a vast wilderness in Florida’s panhandle where the Apalachicola National Forest runs into the Gulf of Mexico. Soon, they turned off the road and onto a two-track that stretched into a silhouette of pine trees. Their brake lights disappeared into the forest, and after about thirty minutes, they parked the truck along the road just as daylight spilled through the trees. Gary took one last sip of coffee, grabbed a wooden stake and a heavy steel file, and walked off into the woods. Audrey slipped on a disposable glove, grabbed a bucket, and followed. Gary drove the wooden stake, known as a “stob,” into the ground and began grinding it with the steel file. A guttural noise followed as the ground hummed. Pine needles shook, and the soil shivered. Soon, the ground glowed with pink earthworms. Audrey collected them one by one to sell as live bait to fishermen. What drew the worms to the surface seemed like sorcery. For decades, nobody could say exactly why they came up, even the Revells who’d become synonymous with the tradition here. They call it worm grunting.

Audrey and Gary Revell took to each other in high school. In 1970 when Gary graduated, he asked Audrey to be his wife, and they married at his grandfather’s place down in Panacea, about thirty miles south of Tallahassee. For his entire life, he’d lived on an acre six miles west of Sopchoppy, Florida, in an area known as Sanborn. The place is set deep in the heart of the Apalachicola National Forest, a vast expanse of flatwoods and swamp that covers over half a million acres struck through with rivers. It’s where he and his siblings grew up in an old church building, where his great-grandfather had settled after finding his way up Syfrett Creek into the wilderness. It’s where Audrey and Gary settled after their wedding. “I was only sixteen, so I feel like I grew up here,” Audrey told me. Soon after, they started looking for ways to make ends meet, and Gary suggested, “We might ought to look into that worm thing.”

His family was already deep into worm grunting. Three generations preceded him, and by 1970, his uncles Nolan, Clarence, and Willie weren’t only harvesting the worms to sell as bait but were working as brokers with their own shops that distributed the critters throughout the South. It didn’t hurt that Audrey fell in love with it immediately. The work was seasonal, busiest in spring. During other parts of the year, their family trapped for a living, dug oysters, logged, raised livestock, and set the table with what they grew in their yard or caught in the water or in the forest. “That’s how we learned the woods,” Gary said. “We went in every creek, water hole, pig trail. You name it.”

By the 1970s, the cottage industry had reached its peak. Then Charles Kurault arrived in 1972 to film a segment for his eponymous CBS show, On the Road with Charles Kurault. The attention led the Internal Revenue Service and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to start regulating the harvest of worms, investigating unreported income, and implementing permit requirements. Back then, the sound produced by grunters in the first hours of daylight was as common as birdsong in this forest, and hundreds of thousands of worms were carried out in cans. Folks who once turned to grunting to make ends meet seasonally were soon in the woods year-round during that decade, competing to summon the bait to the surface and sell to brokers among the counties set between the capital city and the Apalachicola River. Millions of worms left those counties bound for fishing hooks across America. Money followed the pink fever, but as with any rush, the demand eventually dimmed as commercial worm farms caught on and soft, plastic lures became popular.

By that point, Audrey and Gary had decided to shape their own outfit. His uncles had told them, You ought to just think about keeping all that money to yourself. The couple had grown tired of depending on others for work. So, they set up their own shop full time, cultivated clients as far away as Savannah, and delivered bait all over the South, driving it themselves, or sending it north in sixteen-ounce, baby blue containers via Greyhound buses. “All the money was coming our way, what little we made,” said Gary. “We struggled with it for a long time, because when you get off the grid like that and try to do it for yourself and you’re young, it’s hard.”

I wanted to know what spending their life in the woods hunting for worms meant, but I also wanted to know where this mysterious, artful tradition came from. In the UK, there are a handful of worm-charming competitions and festivals in Devon, Cornwall, and Willaston that began in the 1980s and another in Canada that started in 2012. I’d heard of similar events in east Texas, of people using pitchforks and spades as well as burying one stick in the ground and rubbing it with another to coax worms up to the surface. Later, I even found a newspaper clipping from 1970 reporting on the first International Worm Fiddling Championship, in Florida. I searched for a deep well of literature on the practice but found nothing. Certainly, worm grunting predated the Revells. But why did rubbing a stick stuck in the ground with a metal file conjure earthworms? The only way to understand was to follow the Revells into the woods.

In February, I carved out toward the Revells’ place from St. Teresa, a strip of homes along the Gulf coast. Going first through Tate’s Hell, then turning west through the tiny town of Sopchoppy, I slipped into the forest as the distance between each home grew wider and wider. I found myself in a sea of slash and longleaf pine. Six miles later, I met Gary Revell in his driveway beneath an eastern redbud throwing its first spray of pink flowers. “Morning, Mike,” he said with a contagious warmth. In their kitchen, I met Audrey, who had already poured a cup of coffee, set out milk and creamers, and had a jar of sugar in hand. A few minutes later, we piled into their truck and drove down a narrow vein of road near Smith Creek. A horned owl drew a line through the trees, where the yellow flowers of Carolina jessamine crawled over palmettos. Black water pooled in ditches alongside the narrow road lined with bald cypress and the periodic sweet bay magnolia. By the time we reached where we were going, I had no sense of how far we’d gone or where we were.

Although the northern borders of the Apalachicola National Forest press right up against the Tallahassee airport, the place is remote. Across nearly six hundred thousand acres, you could spend lifetimes trying to map its dizzyingly vast flatwoods, hydric hammocks, and cypress stands. Two hundred and fifty million years ago when our contemporary continents formed, Florida’s peninsula broke off a fault line belonging to what’s now West Africa; they share the same basement rock today. Fifty-six million years ago, as sea levels receded, the Suwanee Current flowed from the Gulf of Mexico across what’s now Florida’s panhandle, bisecting Georgia before running into the Atlantic. And over the next twenty million years, Florida appeared first as an island separated from North America by a sequence of patch reefs before sea levels continued to fall and a bridge formed with Georgia, revealing this very forest. A few thousand years later, the bones of the southern Appalachians, ground into dust by glacial erosion, washed out of the Apalachicola River Valley and formed barrier islands that rim Apalachee Bay today. That river carried sediment down through Georgia and into the Gulf, which flanks the western edge of the forest. And as you move east, the New River, the Ochlocknee River, and the Sopchoppy River flow through the forest made up of two districts. An archipelago of sinkholes and hardwoods is lacerated by thin roads that mirror oxbows in the rivers. In 1936, when the land was declared a national forest, it became one of America’s southernmost pockets of wilderness and among the world’s most unique ecosystems. As the Revells told me, many are afraid of the place, scared to step foot out of the car. “I’ve walked all over all these woods, so I love them,” Audrey said. “A lot of times when we’ll be going to work in the mornings, we won’t meet a single car. It’s just nice being out here mostly alone. You know?”

Left: Gary Revell roops in a stand of recently burned trees in the Apalachicola National Forest just after daybreak. Right: A native earthworm, Diplocardia Mississippiensis, crawls across the ground before Audrey Revell collects it by hand. Photographs By Michael Adno

That first morning I spent with them, the Revells made their way to a part of the woods called Twin Pole. The forest service had recently burned a block of woods there, which meant the ground would be clear and easier to work. As we got closer, I could smell the sweet fragrance of smoldering slash pines and palmettos. For centuries, pine scrub and prairie throughout the South has burned naturally and been torched deliberately, first by Indigenous peoples like the Timucuan or Apalachee and then later by ranchers and land managers to replenish the soil and promote growth. Worm grunters follow the forest service’s burns like a compass, as the open ground makes it easier to spot worms and avoid venomous snakes.

“Alright, Mama,” Gary said to Audrey before changing into a pair of boots, fastening knee pads, and slipping on gloves. We walked through the burnt palmettos, coated in a film of black soot, before he pointed to a few holes in the soil. They were clues to where worms were and where they were headed. He took his stob, one his son had hewn out of black gum, and knocked it a foot into the earth with his steel file before rubbing the file against the stob’s head. He called each pass a “roop.” With every roop, he mirrored the sound himself, groaning first in a low pitch then ascending to an abrupt stop. Gary would roop, pause, tell a story, then start again. It didn’t take long before a dozen large earthworms began crawling around the earth between us as Audrey gathered them by hand.

“Gary can call up any kind of animal,” Audrey said. Screech owls, ducks, even a bull they once came across in the woods. Once, after he called to a quail, Audrey swears the bird landed on his head. I looked down as Audrey picked up worms and could see this was a corollary. As Gary rooped and talked, Audrey drew concentric circles around him, picking up the largest worms and carefully placing them in a one-gallon paint can. Audrey noted the difference between worms—“milky” that are lighter in color and frail, and dark pink worms that last longer on the shelf. Gary roops most of the time, but Audrey does sometimes, too. “They’re coming up tail first,” Gary said. He gazed down and read the ground: Here were some castings left by worms; some mounds of fresh earth; a transition in the ground that meant prime moisture. The Revells’ intuition was like that of the fishermen they were collecting bait for, a catalog of knowledge assembled from spending time out here and bound together by deep curiosity. Gary knocked his stob down against the serpentine root of a palmetto and demonstrated how to change the pitch. “When I see that,” he said, pointing to some larger holes, “I know he’s right here somewhere close.”

With a couple of paint cans filled, about 500 worms in each, Audrey and Gary headed back to their truck, collecting scraps of trash and some firewood along the way. An hour later, they dumped their catch out in a shed where they store their worms, counting them out by hand and then placing them in five-gallon buckets filled halfway up with sawdust they collect in the forest. Folks that know them come and collect worms from the shed themselves, leaving the money they owe in a box on the wall. Often, they’ll leave notes scrawled on pieces of cardboard, check registers, and even a cast-off piece of packing tape that read, “I got 200. I paid back the ten I owe.”

For two convenience stores in Wakulla County, Audrey and Gary are the source for worms. At home, they pack the bait in clear plastic cups with baby blue caps and deliver them each week. In the decades since the Revells struck out on their own, the market has winnowed with the advent of artificial baits and farmed nightcrawlers, and so have the venues to sell worms. In good years, they earned $30,000, according to a 2009 piece in the Tampa Bay Times, but they told me they didn’t want to discuss what they make today. Some years, they harvested oysters for part of the winter and then baited throughout the warmer months. The two found their way through, together, even when bad weather, drought, and competition reshaped the way they worked. They started traveling farther into Liberty County, hiking deep into the flatwoods to avoid previously worked pieces of land. In summer, when the temperature turned mean, they worked Tate’s Hell at night. “This earthworm deal is something that you got to live with and stay on top of to be able to survive it,” Gary said, “and we can say we’ve lived a very good life.” They’d raised their two sons this way, spent their lives living with the forest, watching almost every sunrise out there together. “It ain’t been no easy deal, but there’s really nothing on earth I’d trade for it,” Gary said. Today, one of the Revells’ sons, who is now forty-eight, marks the fifth generation of their family collecting the pink currency from the forest.

In the nineteenth century, Gary’s great-great-grandfather paddled up the Ochlocknee and into a branch that bent into the trees before it dissolved into a shallow stream. Audrey and Gary live in that area today, near a creek named for one side of his mother’s family, the Syfretts. As kids, Gary and his two brothers, Lucious and Donald, came up in the woods, often passing the days with three cousins opposite the creek from them. “We didn’t have a lot of people around, but we had this forest, and that kept us occupied.” Their father, Frank, was an equipment operator for the county during the week, but worked alongside his brothers on the weekends, grunting in the forest at first light. Fifty years ago, he could earn as much as a hundred dollars in two days of baiting, which dwarfed what he made in a week for the county, roughly eight hundred dollars in today’s money. Gary tagged along any chance he got. That’s how he first heard the tale of his great-grandfather’s worm discovery in the 1940s. Living along the Ochlocknee River, his great-grandfather fished often, and developed a sense of what baits worked where and when. While repairing his car one day, he’d left it running, jacked up the chassis, and removed a wheel. As the tire rolled away and his eyes followed it, he saw the ground strewn with pink worms.

As the story goes, his great-grandfather tested the theory elsewhere, leaving the car to idle and seeing worms sprout up on the spot. It was clear the vibrations stirred the worms, making it easier to collect bait and therefore sell it. This is how the mysterious practice became central to the Revells’ lives.

The Revells’ Intuition Was Like That Of The Fishermen They Were Collecting Bait For, A Catalog Of Knowledge Assembled From Spending Time Out Here And Bound Together By Deep Curiosity.

Later, the men noticed worms appearing when they chopped wood or ran saws against saplings. Gary remembered using an axe handle as a stob, rubbing the blade of another axe against it. Some folks in north Florida called it worm fiddling, worm rubbing, worm snoring, worm charming, and, of course, worm grunting. Styles and materials for coaxing worms to the surface varied. Some people preferred hickory stobs and used steel leaf springs from cars as a file. The Revells used different-shaped stobs for different sorts of soil, but they always used black gum, persimmon, or cherry wood, and preferred flat, thick steel files.

What’s strange is that despite the widespread practice of worm grunting, I couldn’t find a definitive origin story. There wasn’t a deep well of folklore to draw from online: not in the University of Florida’s special collections archive, the Florida State University archives, or those of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University. I searched my copy of the Federal Writers’ Project’s guide to Florida, organized by Stetson Kennedy and partially written by Zora Neale Hurston, with no luck. I couldn’t find anything that went farther back than the 1970s. But after another pass through the newspapers at the University of Florida, I found a path that stretched back more than a century.

On Friday, July 16, 1946, the Bradford County (FL) Telegraph ran a front-page item, “Know Anything about ‘Worm Grunting’?” They asked readers to submit letters, offering a five-dollar prize for “the best replies to a series of questions on this fascinating subject.” Among them: how long had the practice existed, who told them about it, where they grunted, what they looked for, what they used, and what time was best to do it. Three months later, the paper published six letters. Dave Crawford from Starke wrote that he’d learned of it in 1933. Some claimed that it had existed at least since 1896, another since 1866, while one reader claimed it had been around in some form since 1786. One man wrote, “When I was a small boy, there was an old colored woman that worked for us. In the afternoon she would take me out and teach me to grunt for worms. She told me her mother taught her to grunt worms.” Those anecdotal accounts raised the question of whether this was a tradition that extended back to the period of chattel slavery in America or even farther, before Indigenous peoples were forced from the land that settlers would come to call Florida.

The Revells’ tales of grunting echoed those long-ago anecdotes. Readers referenced an axe handle method, or crosscut saws, and an iron and a stake—all before Audrey or Gary were born. The winning letter from Dave Crawford revealed a bit of poetry and intuition that grunters still practice today: “When the wen is from the west the werms come up good and when you see the birds feeding on the ground and the red heads flying from tree to tree you can grunt up better. Just get a old ax or tire iron and a good pine stob about 2 feet long and a old lard bucket and get down by the swamp where it is wet and boy go to rubing and get busy and grunt long and loud and the old boys will come out they hiding place.”

That tradition endures, largely unchanged here in the Apalachicola National Forest. Yet, it’s vanishing like so many other foodways, forms of heritage, and ways to earn a living in this part of the country. Lots of folks preferred this work to other forms of labor, such as driving an Uber in town or food delivery, but commercial fishing, crabbing, and the shrimp industry have shrunk with each passing year due to increasing regulation, depleted fisheries, climate change, and cheaper imported seafood. The same is true for oyster harvesting, once a mainstay of the region’s foodways. After years of oyster decline partly due to overharvesting and negligent water management, in 2020 the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission mandated a five-year halt in harvesting oysters from the Apalachicola Bay. It was part of a $20 million plan to restore the habitat and population. That ban promised to leave local oyster tongers without work until 2025. As for worm grunting and its slow decline, the passage of time is responsible, too. “All the old people is gone,” Gary said. “That was the key to the whole thing. They set it up.”

In 2002, a committee was organized to preserve the tradition and put on the first annual Sopchoppy Worm Gruntin’ Festival. Every second Saturday in April since, Rose Street and Winthrap Avenue fill with vendors, bands, and demonstrations. There’s a ball and an annual queen. Media outlets flock to Wakulla County to cover the festival, often centering the Revells in their pieces. In 2009, they appeared on the Discovery Channel’s Dirty Jobs. That same year, Jeff Klinkenberg profiled the Revells for a cover story in what is now the Tampa Bay Times. Nobody could say definitively why the worms responded to vibrations, though, until a neuroscientist arrived in Sopchoppy with a theory.

As A Kid In Maryland During The 1970s, Kenneth Catania had a curiosity about the woods near his home that shaped his career path as a neuroscientist with a bent toward ecology and biology. His obsession with moles came later during a job at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. And that obsession eventually grew into a dissertation on star-nosed moles, which revealed how their sensory cortex evolved and developed to process information. This, by proxy, revealed how all mammals’ senses evolved. In 2006, he earned a MacArthur Fellowship or “Genius Grant.” The award came with $500,000. Two years later, he headed for the Apalachicola National Forest, thinking that the moles there might help him unravel another mystery about a different group of underground creatures.

For years, he’d wanted to visit the worm festival in north Florida, but annual field work always overlapped. Finally, in 2008, he drove to meet the Revells in Sopchoppy. He arrived with a question shaped by a few sentences written a century earlier by Charles Darwin about worm behavior as it related to moles.

Darwin published his last book in 1881, The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms With Observations on Their Habits. A sentence that struck Catania read, “It has often been said that if the ground is beaten or otherwise made to tremble, worms believe that they are pursued by a mole and leave their burrows.” Darwin continued, “Nevertheless, worms do not invariably leave their burrows when the ground is made to tremble, as I know from having beaten it with a spade, but perhaps it was beaten too violently.” Seventy years after Darwin’s shovel experiment failed, Dutch biologist and Nobel Laureate Nikolaas Tinbergen claimed that herring gulls tapped their feet to drum up worms, employing “exploitative mimicry.” By 1982, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins had built off that notion, staking claim to the idea of “rare enemy effect,” by which predators cast themselves in the role of another predator to exploit their prey’s behavior.

Then in 1986, a paper by John H. Kaufmann of the University of Florida drew a connection between wood turtles’ stomping to draw worms to the surface and the work of worm grunters. “Many humans collect earthworms for fish bait by hammering or scraping on a stake driven into the soil…. There is now evidence that wood turtles, Clemmys insculpta, use the same principle in obtaining earthworms for food,” Kaufmann wrote. He also noted an earlier paper from 1960 by Tinbergen that identified a corollary in herring gulls among other birds like flamingos and geese that drummed up prey by “paddling.” Especially fascinating is that Tinbergen hypothesized that the worms mistook the birds’ paddling for the vibrations of a mole. “That’s what drew me down there,” Catania told me. He wondered whether worm grunters were unintentionally mimicking a predator, possibly a mole like Darwin and Tinbergen suggested. “Nobody had formally studied it,” he said.

On that first morning in Florida, Catania’s alarm woke him at five. He got ready and met the Revells, who charmed Catania immediately as he took a seat in the cab of their truck. As they drove into the forest, he thought of this Darwinian theory that shaped his own hypothesis: that earthworms had developed an escape response to vibrations caused by a foraging mole. “What’s beautiful about the system there is the earthworms are native, so they evolved there, and if the moles are there, they evolved there, too,” Catania said. Most importantly, he wanted to find out if the vibrations generated by worm grunting echo that of a digging mole and, if so, how the earthworms respond.

As they rode along, Catania noticed mole tunnels crisscrossing the backroads. He saw more around the stand of trees where Audrey and Gary worked. Catania was spellbound as he watched the couple work. Weeks later, he returned with recording equipment, marking flags, and a garden trowel. He spent hour after hour, day after day in the forest, dropping geophones into tunnel routes, hoping to record the vibrations of moles digging, as well as those produced by Gary’s grunting. For every worm Audrey picked up, he placed an orange flag in the ground, mapping just how many worms appeared, in what directions, and how far from Gary’s stob. Then, he stalked moles underground, using stakes placed along their routes to reveal where they were headed, and used the garden trowel to catch them. Back at the Revells’ place, they took a handful of worms, placed them in a five-gallon bucket, and dressed them in a pile of sawdust. Catania picked up a mole and dropped it into the bucket. The worms fled to the surface. “Okay,” Catania thought, “things are pretty clear.”

He replicated this experiment in larger bins with controlled variables. The result was the same. As soon as the mole entered the soil, the worms fled to the surface. Catania later recorded the sound of an eastern American mole digging and compared it to his recordings of Gary rooping. It was a sonic match. The vibrations were almost identical.

Catania’s work with the Revells confirmed Darwin’s theory set forth more than 125 years earlier. Worm grunters had unknowingly applied “exploitative mimicry” like that employed by herring gulls or wood turtles to lure the worms to the surface. Catania published his paper that same year in PLoS ONE, a peer-reviewed journal. The New York Times even ran a small story about his findings, as did NBC News and other outlets. Before he returned to Nashville, Catania received a parting gift from Audrey and Gary—a rooping iron that had been in their family for decades. As he drove north that day, he stopped one last time in the woods, drove a stob into the soil, and rooped with a clear sense of what was happening underground.

Audrey Revell collects worms by hand in the Apalachicola National Forest as Gary Revell moves to the next spot, carrying his rooping iron and stob. Photograph by Michael Adno

On My Final Morning With Audrey And Gary, a seam of blue sky between the pines grew brighter as they drove out into the forest. Slowly, the first signs of light threw deep shades of purple against the clouds before pink, then scarlet bands passed through the trees. “That’s beautiful,” said Audrey.

They parked their truck along the road, collected their gear, and walked into the woods. As we neared a brake of trees, Gary passed me the stob and file, pointing to a patch of earth, and I clumsily drove the stob down. I tried to place my hands on the file the same as Gary, and I slowly slid the steel at an angle. A deep noise followed, and I just smiled, rooping again and again. I varied speed and angles, making some wince-worthy goose noises on bad passes, but I found a rhythm, and soon I’d drawn up a dozen worms. I moved a few times, continuing to work, removing some layers. When I finally got up, Gary asked, “So, Mike, what do you think?” My chest throbbed and sweat ran down my neck. “It’s fucking hard work,” I said.

Back at their place, Audrey made some sweet tea and showed me a couple albums of photographs she’d made of flora and fauna in the forest. She told me of terrestrial orchids “as pretty as one you would buy,” of the pitcher plants in spring, and the white “worm flowers” that signal damp ground. “You never know what you might see,” she said. Finally, she brought out some scrapbooks and clippings of articles from the New York Times, Scientific American, and the Tallahassee Democrat. In 2010, the Revells received Florida’s Folk Heritage Award, an honor recognizing Floridians who preserve living traditions. Governor Charlie Crist presented the award in a ceremony at the state Capitol. As we looked through those reminders of their life in the forest, Audrey and Gary turned serious. “I’m a steward of this forest,” he said. “I don’t do nothing to try to abuse it or change it.” I asked Audrey what the forest meant to her. “Everything,” she said.

That afternoon, as I prepared to leave, I found myself moved in a way I hadn’t been in years, fascinated by their connection to the forest, above ground and below. “As much as we’ve done it, I’ve thought, ‘Man, you’ve got to be crazy,’” Gary said of their work. “But, if you take me away from it, I ain’t worth nothing. I’m one of the last.” I drove away with a sore palm and a cup of worms beside me.

#OxfordAmerican.Org#The Worm 🪱 Charmers!#Earthworms 🪱#Florida Family#The Forest Floor#Apalachicola National Forest#Diplocardia Mississippiensis#Gary Revell | Audrey Ravell

0 notes

Text

Horace King or Horace Godwin (September 8, 1807 – May 28, 1885) was an architect, engineer, and bridge builder. He is considered the most respected bridge builder of the 19th century, constructing dozens of bridges in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. He was born enslaved on a South Carolina plantation. His owner, John Godwin taught him to read and write as well as how to build at a time when it was illegal to teach enslaved. He built bridges, warehouses, homes, and churches, and most importantly, he bridged the depths of racism. He became an accomplished Master Builder and he emerged from the Civil War as a legislator in the State of Alabama. Known as Horace “The Bridge Builder” King and the “Prince of Bridge Builders,” he served his community in many important civic capacities.”

Between the completion of the Columbus City Bridge in 1833 and the early 1840s, he and Godwin partnered on no fewer than eight major construction projects throughout the South. The partners constructed some forty cotton warehouses in Apalachicola, Florida. Scholars believe that Godwin sent him to study at Oberlin College. The two men designed and built the courthouses of Muscogee County, GA, and Russell County, AL, and bridges in West Point, GA, Eufaula, AL, and Florence, GA. They built a replacement for their Columbus City Bridge between Columbus and Girard.

He was allowed to marry Frances Gould Thomas, a free woman of color. It was uncommon for slave owners to allow such marriages since her free status meant that their children would all be born free.

He was publicly acknowledged as being a “co-builder” along with Godwin, an uncommon honor for a slave. He worked as an architect and superintendent of major bridge projects in Columbus, Mississippi, and Wetumpka. While working on the Eufaula bridge, he met attorney and entrepreneur Robert Jemison, Jr., who soon began using him on several different projects in Lowndes County, MS, including the Columbus, MS bridge. He would remain his friend and associate for the rest of his life. He bridged the Tallapoosa River in Tallassee, AL. He built three small bridges for Jemison near Steens, MS. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

Indigo snakes released in the Florida Panhandle

New Post has been published on https://petn.ws/wRBnJ

Indigo snakes released in the Florida Panhandle

Indigo snake release in the Florida Panhandle Florida wildlife officials recently released 41 eastern indigo snakes in a rural region along the Apalachicola River in the Panhandle in an effort to help restore the ecosystem. (Central Florida Zoo & Botanical Gardens) TALLAHASSEE, Fla. – Florida wildlife experts recently released dozens of eastern indigo snakes into the […]

See full article at https://petn.ws/wRBnJ #ExoticPetNews

0 notes