#Antony Polonsky

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hi, I'm unsure if this is your area of expertise but I was hoping if you know of any primary and secondary sources on antisemitic violence done to Jews returning to their homes in Poland immediately after the Second World War. I found a secondary source on the topic by Jan Gross, though I was hoping if you could point me in the right direction to any other sources.

Hi! While you are correct that it's not my focus, it's certainly an issue which exists in the orbit of my work. Jan Gross' Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz is required reading, of course. I also recommend:

Antisemitism and Its Opponents in Modern Poland by Robert Blobaum

Bondage To the Dead: Poland and the Memory of the Holocaust by Michael C. Steinlauf

Cursed: A Social Portrait of the Kielce Pogrom by Joanna Tokarska-Bakir

The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland edited by Antony Polonsky and Joanna B. Michlic

Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Vols. 9, 13, and 20

While I can't think of any primary sources off the top of my head (though Yitzhak Zuckerman addresses some of this in his A Surplus of Memory), you will find primary sources by mining the bibliographies of the above secondary sources.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trzeba mówić po polsku

Z Antonym Polonskym rozmawia Konrad Matyjaszek Antony Polonsky Trzeba_mowic_po_polsku_Z_Antonym_PolonsPobierz

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Volume 33: Jewish Religious Life in Poland since 1750

Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Volume 33: Jewish Religious Life in Poland since 1750

Editors: François Guesnet, Antony Polonsky, Ada Rapoport-Albert, Marcin Wodzinski Following tremendous advances in recent years in the study of religious belief, this volume adopts a fresh understanding of Jewish religious life in Poland. Approaches deriving from the anthropology, history, phenomenology, psychology, and sociology of religion have replaced the methodologies of social or political…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

just saw a post explaining that white people can experience splash-effect racism when they are perceived as not-white (usually when they have racialized features) because racism is a structural phenomenon & also exists in the eye of the beholder & i am realizing i will probably have to devote a section of my fake thesis to explaining via ~theory what seems so self-evident in practice there is even a set phrase for it in russian, i.e., "бьют по морде, не по паспорту"

(iirc antony polonsky has an article called "why did they hate tuwim & boy so much?" which touches on this & the answer for tuwim is more straightforward while the answer for boy is 'frankist family, frankism understood as a form of crypto-judaism, & his wife Looked Jewish (TM) Despite Her Married Last Name which is why the endek press always called her the period equivalent of irena (((goldberg))))

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

danger knows full well that caesar is more dangerous than he

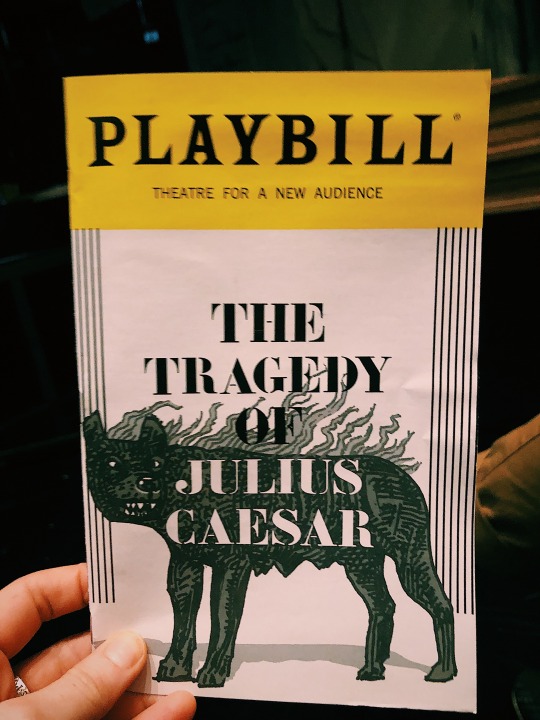

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

Theatre for a New Audience

dir. Shana Cooper

Shakespeare’s Caesar is a great script with timely circumstances. This production, coming to Theatre for a New Audience after a run at Oregon Shakespeare Festival, rides in on the heels of a number of recent Julius Caesar revivals. Most notably, perhaps, being the Public’s infamous production at The Delacorte two summers back. Shana Cooper’s Caesar takes perhaps the opposite approach. Instead of outfitting the characters in a very specific place in a very specific time (The Presidency of 2017), the Rome of TFANA’s Polonsky Shakespeare Center seems to live in an unspecified luminal space.

As a society currently very familiar with the story of Julius Caesar, this production couldn’t seem to decide what it wanted to add to the conversation. I found myself yearning for the logic behind the process. Why this version of this play at this specific moment in history?

The Calpurnia/Portia scenes are tricky. These women have 5 minutes to justify their presence in this play; to reach the same level of gravitas and intimacy as the men. The women feel stifled all across in this production. Tiffany Rachelle Stewart, brilliant in this summer’s Sugar In Our Wounds, has been given a few extra moments in an attempt, I suspect, to imbue meaning upon women who don’t have much meaning in the original text.

The production needs to decide if it is making a comment on masculinity and commit to its choice either way. Throwing two extra women in small ensemble roles is both not enough and too much.

An emotional wash spiked by moments of sharp, poignant, powerful clarity. The murder of Cinna the poet, a thrilling artistic move! Yet the murder of the titular character (spoilers, oops), decidedly less so. The physical language of the world was inconsistent, but occasionally absolutely brilliant. At one point Caska kissed another soldier on the head, exploring tenderness in the riled-up masculinity of war. The final fight combat sequence has stuck in my head for days afterward.

Important moments felt rushed (The introduction of Mark Antony) while other moments lacked the spark to stay engaging (Calpurnia’s scene, but as I mentioned earlier, I don’t feel the women in the cast were set up for success). Perhaps later into their run the pace will iron out. Or perhaps the pace set at OSF doesn’t translate here.

Matthew Amendt’s Cassius, a standout in my opinion, was fierce and motivated. Brutus (Brandon J Dirden) and Mark Antony (Jordan Barbour) were sometimes surface-level brooding. Stephen Michael Spencer as Caska brought a series of unexpected choices and exciting physicality. The set design by Sibyl Wickersheimer was effective without being focus-stealing, and vaguely evoked last season’s Winter’s Tale environment. The costumes (Raquel Barreto) were similarly utilitarian-chic, with the exception of the odd outfits worn at the top of play.

This production has a very strong foundation, things are bubbling beneath the surface and these ideals echoing in our minds endlessly in 2019.

#women review things#beware the ides of march#beware the snides of march am i right#shakespeare#julius caesar#theatre for a new audience#caesar#the tragedy of julius caesar#playbill#theatre critic#the interval#off-broadway

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

IKEA als Alternative?

Vor dem Zweiten Weltkrieg lebten die meisten Juden in Polen. Mit fast 3,5 Millionen Mitgliedern stellte das polnische Judentum eines der wichtigsten Zentren jüdischen Lebens darf. Die Sowjetunion beherbergte die zweitgrößte jüdische Gemeinde Europas. Bei einer Volkszählung 1939 gaben über 3 Millionen Menschen an, sie seien "jüdischer Nationalität". Die Sowjetunion war ein wichtiger Ort jüdischen Schaffens, obwohl Stalin die besonderen Autonomierechte, die den Juden 1920 gewährt worden waren, Stück für Stück beschnitt. Auch Litauen mit über 150.000 Juden war ein lebendiges Zentrum der religiösen jüdischen und säkularen jüdischen Kultur. Der Ursprung der jüdischen Gemeinden in diesen Staaten lag in der Adelsrepublik Polen - Litauen. Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts lebten auf dem Gebiet dieses riesigen Staates mehr als eine Dreiviertel Million Juden - mindestens ein Drittel aller Juden der Welt. Zur Blüte gelangte die jüdische Gemeinde durch die "Vernunftehe" mit dem polnischen Adel (slzlachta), der das Land dominierte und es den Juden trotz der Ausbrüche antijüdischer Gewalt, die u.a. die Krise des polnischen Staates Mitte des 17. Jahrhunderts begleitet hatten, ermöglichte, sich wirtschaftlich und intellektuell zu entfalten. Juden durften fast ungehindert Handel treiben und ein Handwerk ausüben. Häufig verwalteten sie die Besitztümer des Adels. Die jüdischen Tischler, Schuster, Schmiede, Schneider und Wagner waren nicht aus der ländlichen Tradition der Dörfer und Kleinstädte (Schetlach) wegzudenken. Das war einzigartig in Europa. Auch das jüdische und religiöse Leben entwickelte sich reichhaltig. Antony Polonsky, Fragile Koexistenz, tragische Akzeptanz. Politik und Geschichte der Juden Osteuropas, in: Osteuropa. Impulse für Europa. Tradition und Moderne der Juden Osteuropas

ISLA - Blog Label��“Eastern European Jews”

0 notes

Quote

I cannot resist the thought that Gross would not have written this book [Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland] if he had not worked abroad. I am referring not to the censorship of academic circles but to a more optical phenomenon. From up close, and especially from inside, it is impossible to see certain things. The Polish obsession with innocence is impossible to notice. It is also impossible to see that the rules that govern Polish public and private debate are controlled by this pressure of innocence. Above all, one cannot see that what Thomas Merton called the “pitiable refusal of insight” is seen by everyone but ourselves. It appears that one sees only what one knows. How does what Poles know about themselves and about the Holocaust translate into Polish innocence? The question “What do Poles know?” is directed first to historians. Rightly so, because historians are the ones who construct school curricula. And not rightly so, because as the German example shows, even the most certain knowledge about historical guilt translates into national awareness of this guilt indirectly and with difficulty. If we can talk at all about the responsibility of Polish historians for what Poles do not know about the Holocaust, we can do it only in terms of the sin of relinquishment. This is often the result of the innate caution of historians, which drives them away from certain subjects. The aspiring young historian knows of the price that can be paid in Poland for a “premature” publication. Is it necessary to recall here the name of Michał Cichy and the list of historians who replied to his article? A historian, like any other academic, wants first of all to be “serious.” “Serious” in Poland means “uncontroversial.” An uncontroversial Polish historian strokes his beard, watches with forbearance those who are in a hurry. What we are to do with this leisurely manner of the historians in a country in which the last witnesses to the war and the Holocaust are dying out is not really known. The quotation from Günter Grass cited above gives us further perspective. It seems that Polish children and grandchildren will also remember in lieu of their silent fathers and grandfathers. Undisturbed by historians, those witnesses will take with them to the grave everything that still should be told about szmalcownictwo [blackmailing] and the Blue Police, about the Baudienst formation in which Polish youth served, and about the pogrom in Warsaw during Holy Week in 1940, about priests informing on Jews on the basis of information received in confessions, about Jedwabne, Radziłów, and about the innocent ritual of “the burning of Judas” practiced during the war, about the glasses of water sold for gold coins to the Jews packed in “death trains.” And about the “railroad action” in 1945, in which the partisans of Narodowe Siły Zbrojne dragged some two hundred Jews repatriated from the East out of the trains and shot them, about the murder of Jews returning from exile, about pogroms in Kielce, Kraków, and hundreds of other unknown denunciations during and following the war. Surely this will happen unless, leaving the historians to their own reputations, we do what Jan Tomasz Gross has done and start talking about it.

Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, “Obsessed with Innocence” originally in Gazeta Wyborcza, 13-14 January 2001, reprinted in the book, The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland, edited by Antony Polonsky, et al., Princeton University Press, 2004.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antony Polonsky, “The Jedwabne Debate: Poles, Jews and the Problems of a Divided Memory”

http://dlvr.it/R7cv69

0 notes

Text

this is somehow the bitchiest thing i’ve ever seen written in a historiographic* essay [please read full post before engaging/reblogging]

“I do not believe that this anti-Semitic policy was inevitable. Anti-semitic attitudes, like other prejudices, exist everywhere; but policies are the result of conscious decisions. Poland inherited a ‘Jewish problem’. For various reasons the new Polish state rejected the assimilationist Jewish policy of pre-war Hungary or interwar Soviet Russia. I believe that the crucial factor here was the belief among the governing Polish elite that Poland had re-emerged as a nation state, the main mission of which was to advance the interests of the Polish nation - when being a ‘nation’ was defined as being able to absorb certain non-Polish elements but not being able, or not desiring, to absorb the Jews. This self-definition inevitably led to anti-Ukrainian policies...and to anti-Jewish policies and attitudes. Israelis are in a good position to understand that any state which defines itself as a mono-ethnic entity, but which in fact includes within its borders members of other ethnic groups that cannot be absorbed, must act in a way which is deleterious to the interests of these other groups. Again, exactly how adversely the interests of the unassimilable minority' will be affected depends on various local factors.”

Ezra Mendelsohn, “Interwar Poland: good for the Jews or bad for the Jews?” in The Jews in Poland, eds. Chimen Abramsky, Maciej Jachimczyk, and Antony Polonsky, (Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell Ltd, 1986), 137.

I’ve read a lot of Pointed Things about Zionism is historiographic essays. Sometimes to the point where I’m like “....is bro taking issue with the State of Israel et al or does bro hate Jews because lol this is a book about Indonesia.” But DAAAAAMNNNN EZRA.

*Historiography sections/essays are where historians discuss the state of the literature; ie: how other historians analyze and conceptualize the field. In the larger field of Modern Jewish History, most practitioners are Jewish, and have extremely diverse, passionate, and often conflicting views on the State of Israel, Zionism, Palestine, geopolitics, etc. They often disagree with each other intensely, leading to lifelong grudges and salt-the-lands polemics in obscure journals that no one outside the field would have have reason to read. This excerpt should be understand not as much as commenting on the State of Israel or right wing strands of contemporary Zionism, as it is Dr. Mendelsohn firing shots at certain of his colleagues.

If you would like to get into Discourse about the political issues and questions Mendelsohn raises here--as they are intellectually and politically provocative, and intentionally so--please copy and paste this into a new post and do it there; I/P etc online discourse gives me hives. I’m posting this simply as a messy bitch who loves historiographic drama.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trzeba mówić po polsku

.

Z Antonym Polonskym rozmawia Konrad Matyjaszek Abstrakt: Przedmiotem rozmowy z Antonym Polonskym jest historia pola badań studiów polsko-żydow-skich od momentu, kiedy powstały na przełomie lat siedemdziesiątych i osiemdziesiątych XX wieku, ażpo rok 2014. Antony Polonsky jest głównym historykiem wystawy stałej Muzeum Historii Żydów PolskichPolin i redaktorem naczelnym rocznika naukowego „Polin:…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The 59 books posted on JewishBookWorld.org in February 2022

The 59 books posted on JewishBookWorld.org in February 2022

Here is the list of the 92 books that I posted on JewishBookWorld.org in February 2022. The image above contains some of the covers. The bold links take you to the book’s page on Amazon; the “on this site” links to the book’s page on this site. (more…)

View On WordPress

#A Pain in the Tuchis#A Requiem for Hania#A Targumist Interprets the Torah#A “Jewish Marshall Plan"#Abraham Kronenberg#Adam Mansbach#Alex Pomson#Alice Blumenthal McGinty#Always Remember Your Name#Alwin Meyer#American Princess Warrior#Andra Bucci#Andrew Fukuda#Anne Schenderlein#Antony Polonsky#Antti Laato#Aviva Hermelin#Barry Friedman#Batya Brutin#Bethany Ball#Betsy R. Rosenthal#Coming to Terms with America#Daniel Horowitz#Daniel Lasker#David Gelernter#Dekel Peretz#Destruction of Bilgoraj#Dream Catcher#Eleanor Reissa#Etched in Flesh and Soul

0 notes

Text

Book Reflection | The Jews in Poland and Russia: A Short History

My first book reflection in a long time! I actually finished this book a while ago but kept putting off doing the reflection, but here I finally am. This book calls itself a short history, but it’s actually almost 700 pages long. I think the ‘short’ part comes from the fact that it’s an abridged version of a much longer three volume work which is essentially the culmination of the author Antony Polonsky’s lifetime of research. This book took me a long time (a few months) to read for a number of reasons. Its length, the fact that I wasn’t reading very much in the first place, and the fact that it was very dense. It was obviously very thoroughly researched, being the lifelong work of an academic who specialises in the topic, and was quite different to a lot of other book I’ve read about Jewish history.

A lot of the books I’ve read in the past have taken a quite personalised look at Jewish history, telling the story through personal accounts, looking at individual figures and social trends, and having an element of entertainment and/or humour. While I still enjoyed A Short History, it was very dry, dense, and academic in tone, with a great deal of facts, figures, and percentages. While it could be tough to wade through at times, I did enjoy the amount of fine detail Polonsky included about such things as migration patterns, relations between different Jewish (as well as non-Jewish) communities, inter-community religious conflicts, schooling, religiosity and population statistics, and detailed discussions of the intricacies of how Jews interacted with and were treated by the two world wars.

A Short History starts off by detailing the initial settlement of Jewish communities in Poland and Russia, then goes through their history from the 15th century up until the present day, covering such topics as social and religious changes throughout the ages, World War I and II, and Jews during and post-Soviet Union. The most detail was found in the middle sections, with there being somewhat less in the earliest and the latest sections. I would have preferred a bit more detail here, although it was most likely present in the main three volume work and had to be cut for space for the abridged version. Overall, while it was at times an effort to get through due to its dense and academic nature, I enjoyed this book and would recommend it to anyone who wants a very detailed history of Jewish life in Poland and Russia.

What’s the last book it took you a long time to read?

#original baldursgatecontent#my books#book reflection#jewish#jumblr#booklr#book#judaism#reading#read#bookblr#book worm#bookworm#book nerd#book lover#booklover#book blog#book blogger#bookstagram#bookish#bibliophile#book photo#book photography#book discussion#book talk#reviving booklr

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

The wonderful historian Timothy Snyder of Yale reviews Antony Polonsky's exhaustive study of 500 years of Jewish life in what was once its homeland, Eastern Europe.

Snyder wrote the brilliant and horrific "Bloodlands: Eastern Europe Between Hitler and Stalin," and this review and the Polonsky work bookend that nicely.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Policja mundurowa odegrała smutną rolę

Stanislaw Obirek

Pamiętam, że przed kilku laty prof. Antony Polonsky, główny historyk Muzeum POLIN, na pytanie o wkład polskiej historiografii do światowych badań nad historią Żydów bez wahania wskazał na publikacje Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów. Dodał przy tym, że historykom, którzy chcą się zajmować problemami Holocaustu, zaleca naukę języka polskiego. Bez znajomości prac polskich…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Volume 34: Jewish Self-Government in Eastern Europe by François Guesnet, Antony Polonsky (Editors)

Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Volume 34: Jewish Self-Government in Eastern Europe by François Guesnet, Antony Polonsky (Editors)

Few features have shaped east European Jewish history as much as the extent and continuity of Jewish self-rule. Offering a broad perspective, this volume explores the traditions, scope, limitations, and evolution of Jewish self-government in the Polish lands and beyond. Extensive autonomy and complex structures of civil and religious leadership were central features of the Jewish experience in…

View On WordPress

#Antony Polonsky#François Guesnet#Liverpool University Press#The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization

0 notes

Photo

For this @bibliophilicwitch‘s Sunday Tomes and Tea, it’s The Jews in Poland and Russia: A Short History by Antony Polonsky. It may be called ‘a short history’, but it’s actually almost 700 pages long! I guess that’s short for such an expansive topic, and one that I’m fascinated by given that I’m of Polish Jewish heritage. I’m looking forward to learning more about the region where my family lived for so long, and how their lives might have been.

What’s your favourite long book?

#original baldursgatecontent#my books#sunday tomes and tea#bibliophilicwitch#book#reading#read#booklr#bookblr#book worm#bookworm#book nerd#book lover#booklover#book blog#book blogger#bookstagram#bookish#bibliophile#book photo#book photography#book discussion#book talk#book question#reviving booklr#jewish#judaism#jumblr

30 notes

·

View notes