#Animal communication

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

one of the most fun things so far about living with a cat for the first time (and one of the most on-brand things for me as someone with a linguistics degree) has been getting to learn cat communication. it’s so cool and interesting to be able to notice the difference between certain meows and understand what they mean, like “hey! there’s a bug over there!” and “okay that’s enough snuggling please put me down now” and “scooch over so I can jump onto the bed”. and don’t even get me started on the body language! it’s just so funny, there’s a little guy who lives in my house and neither of us speak the same language but we’re trying!

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marmosets call one another by name

Enduring vocal labels for individuals may be a window into how humans evolved language

Miniscule monkeys called marmosets give one another individual “names,” researchers report today in Science. After recording chirpy conversations between pairs of marmosets in a captive colony, researchers observed how the animals responded to one another and to playbacks of the recordings, discovering that they use distinct vocalizations known as “phee-calls” to address and communicate with specific individuals. A given monkey could tell when a call was directed at them, for example, and respond appropriately...

Read more: https://www.science.org/content/article/marmosets-call-one-another-name

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists figured out chimpanzees have a rudimentary language by pranking them with snakes 🧑🏼🔬🐒🐍🙈

Want an awesome book about how primates communicate and see the world? Check out Baboon metaphysics:

139 notes

·

View notes

Link

Perhaps “syllables” or “phonemes” would have been better terminology. If these discrete combinatory elements are real, it’s up the the researchers to label them with an alphabet or syllabary and transcribe the sequences they record. Nitpicky? Yes, but clarity is next to godliness, eh?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Secret Language of Elephants

Did you know elephants can communicate over miles? Discover their fascinating infrasound and its implications!

Check out my other videos here: Animal Kingdom Animal Facts Animal Education

#Helpful Tips#Wild Wow Facts#elephants#animal communication#wildlife#nature documentary#elephant behavior#conservation#elephant intelligence#animal language#wildlife protection#African elephants#Asian elephants#animal studies#endangered species#nature lovers#wildlife enthusiasts#ecology#animal science#elephants in the wild#elephant habitats#biodiversity#animal emotions#nature conservation#wildlife research#zoo education#animal behavior studies#youtube#animal behavior#animal kingdom

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

writing on the wall

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just realised I consider my cats my animal pack since I can't have actual wolf pack. Cuddling with them, resting together, feeling their fur, it brings me so much comfort. I also feel closer to cat behaviour as a wolf than to dog's.

When I was little, I used to firmly believe I could communicate telepathically with my cats. We used to have really close bonds, and my cat always came to comfort me when I was feeling down. I loved that about her.

I'm trying to understand cat's language now, so I can better attune to their needs, be open to listening to them, because I believe I will know subconsciously what they want if we connect.

My current cat and I have a nice relationship. She doesn't come to comfort me, she gives me space and sometimes she needs her space. But we show deep affection to each other, and I can only describe our relationship as a friendship intimacy.

This is my Lilith:

I also live with my brother's cat, she's a Siberian and she's very fluffy :D She's more attuned to how I feel and will come to request cuddles to snap me out of bad feelings. She also comes to my bed to cuddle with me and comfort me. One time, we napped together cuddled like wolves, it was an euphoric experience. My cat does not like it, though xD

Behold Chiquita (yes, like the banana xD), we didn't choose that name as she has a pedigree, we mostly just call her a furry potato xD

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Across human cultures and languages, adults talk to babies in a very particular way. They raise their pitch and broaden its range, while also shortening and repeating their utterances; the latter features occur even in sign language. Mothers use this exaggerated and musical style of speech (which is sometimes called “motherese”), but so do fathers, older children, and other caregivers. Infants prefer listening to it, which might help them bond with adults and learn language faster.

But to truly understand what baby talk is for, and how it evolved, we need to know which other animals use it, if any. The great apes don’t seem to vocally, but might use a gestural equivalent. Squirrel monkeys and rhesus macaques use special calls when talking to youngsters, but they’re very different from human baby talk, which is a modified version of normal speech. Zebra finches are closer to us: When singing in front of juveniles, adults add longer pauses between musical phrases and repeat introductory notes. Greater sac-winged bat mothers also change their pitch and timbre when signaling to pups, but again, it’s hard to tell if they’re using a distinct call or doing something analogous to baby talk. To make an inarguable case for the latter, you’d need to study a species that talks with both infants and older peers using the same standardized, identifiable call. In other words, you’d need a dolphin.

Every bottlenose dolphin produces its own unique signature whistle, which is the closest thing any animal has to a human name. Dolphins can recognize individuals through these whistles and will sometimes copy one another’s, perhaps as a form of address. They use their whistles frequently, to announce their position when separated from their pod, or as an introduction when meeting up with new groups. Calves develop their own signature whistles based on those they hear around them, and once learned, the whistles can go unchanged for at least 12 years.

Laela Sayigh, a zoologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, has been studying the signature whistles of bottlenoses in Sarasota Bay, Florida, since 1986 as part of the world’s longest-running study of wild dolphins. She and her colleagues regularly catch these animals, check their health, and record their calls before releasing them. Sometimes, they catch mothers and calves together, and the animals exchange signature whistles throughout the process. By analysing 19 such moments, recorded over 34 years, Sayigh’s student Nicole El Haddad showed that mothers raised and widened the pitch of their signature whistles when calling to their calves, just as humans do when talking to their babies.

“We were just blown away by how consistent the effect was,” Sayigh told me. Between their intelligence and strong personality, dolphins behave unpredictably enough that scientists who study them are used to gleaning faint patterns amid messy data. But in this study, every mom changed its signature whistle around its calf in the same way. “The data are extraordinary and impressive,” Sabine Stoll, who studies language evolution at the University of Zurich, told me.

Dolphin baby talk isn’t exactly the same as ours—dolphin whistles don’t get more repetitive—but it’s certainly “the most convincing case of child-directed communication found in nonhuman animals to date,” Mirjam Knörnschild from the Museum of Natural History in Berlin, who led the study on sac-winged bats, told me. And its existence in a species separated from us by more than 90 million years of history is likely a “stunning” example of convergent evolution, Stoll said.

If both species evolved baby talk independently, perhaps they did so for similar reasons. Human parents can better grab their infants’ attention through high-pitched baby talk than through normal speech, and dolphin mothers might do the same. Keeping her signature whistle but raising its pitch “would be a pretty foolproof way for the mom to say ‘This whistle is meant for you’ to the calf, and for the calf to know My mom is talking to me right now and no one else,” Sayigh said. That specificity would allow both of them to keep close contact in a raucous ocean where many dolphins might be sounding off at once.

Human baby talk is also thought to strengthen a baby’s bond with its caregivers, and to help it learn language by exaggerating important features of the spoken word. The same could well apply to dolphins, which also stay with their mother for a long time, and learn calls by listening to their peers. But testing these ideas would be incredibly hard without separating mothers and their calves—an experiment that Sayigh said would cross an ethical line. She showed that dolphin baby talk exists; its exact role “is just one of those things that might have to go unanswered,” she said.

#zoology#animals#animal behaviour#ethology#bioacoustics#animal communication#psychology#child psychology#child development#dolphins

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

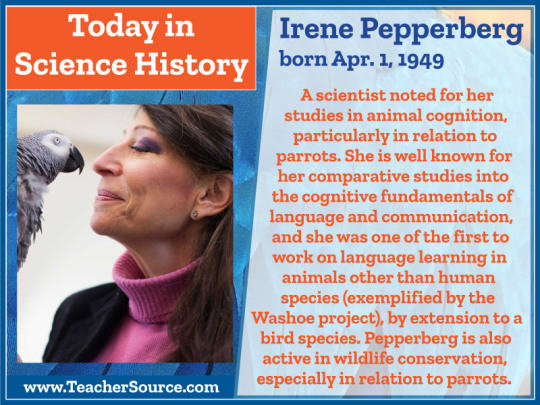

Irene Pepperberg was born on April 1, 1949. A scientist noted for her studies in animal cognition, particularly in relation to parrots. She is well known for her comparative studies into the cognitive fundamentals of language and communication, and she was one of the first to work on language learning in animals other than human species (exemplified by the Washoe project), by extension to a bird species. Pepperberg is also active in wildlife conservation, especially in relation to parrots.

#irene pepperberg#animal cognition#animal communication#animal behavior#parrots#wildlife conservation#science#science history#science birthdays#on this day#on this day in science history#women in science#women in history

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This animal hit me for no reason omg” *was upsetting the animal, over petting, teasing, crossing boundaries, ignoring stop signs, making the animal uncomfortable*

#animals#animal studies#animal welfare#animal wellbeing#animal care#animal communication#cat scratches

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yep, they adapt real quick communication-wise, always so fascinating.

My boy has multiple meows and I know when he's going to the box, wants treats, wants the door open, is bored, is annoyed, wants attention or wants me to fix his sleeping bags.

He does meow at me to bring the sun out too, tho. That accusing little stare when I open the balcony door to clouds.

My cats have this meow that means "please come with me to fix this" after which they'll lead me to the problem in question, usually a empty (or 'empty') food bowl or a closed door they want open. They look at the 'problem', they look back at me, clear message.

What fascinates me is how this illustrates what they percieve as being in the realm of my 'power.' I control the food, I control the door, sure, but my cats love to sit on the balcony in the sun, and it has happened plenty of times that on a rainy day they come get me, go to the balcony and show me... the rain. "Please fix this" they say. "Please get rid of the wet"

"Silly kitty," I say, "I can't control the rain." I then walk into the shower and turn on the rain.

249K notes

·

View notes

Text

These Parrots Won’t Stop Swearing. Will They Learn to Behave—or Corrupt the Entire Flock?

A British zoo hopes the good manners of a larger group will rub off on the eight misbehaving birds

A few years ago, a zoo in Britain went viral for its five foul-mouthed parrots that wouldn’t stop swearing. Now, three more birds at Lincolnshire Wildlife Park have developed the same bad habit—and zoo staffers have devised a risky plan to curb their bad behavior. “We’ve put eight really, really offensive, swearing parrots with 92 non-swearing ones,” Steve Nichols, the park’s chief executive, tells CNN’s Issy Ronald...

#parrot#zoos#bird#ornithology#animal behavior#animal communication#nature#animal intelligence#science

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

The more we learn about elephants, the more we discover what complex inner lives they have!

This article discusses how elephants have complex communities with distinct traditions, including how they communicate:

Want to learn more about elephant communication? Check out Beyond words: What animals think and feel, about the science of animal behavior.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Up. Up."

*sigh*

"This is such a simple trick. Why is she so dense?"

"Up, up, UP already . . . "

He is not asking, he is demanding

11K notes

·

View notes