#American novels

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Sometimes the bravest thing on earth was to sit through the night and feel the cold in your bones.

The Things They Carried, Tim O'Brien

#the things they carried#tim obrien#books#quotes#book quotes#classic literature#american novels#american writer#read this#classic novels#classic books#classic quotes

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week on Content Abnormal we present the 1947 American Novels adaptation of Washington Irving's The Legend Of Sleepy Hollow!

#the legend of sleepy hollow#washington irving#new york#headless horseman#ichabod crane#radio#classic#otr#horror host#dark night of the scarecrow#charles durning#larry drake#american novels#1947

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"There are times when I wish I believed in hellーother than the hells we make for one another, I mean."

Octavia Butler, Parable of the Talents (1998)

#literature#lit#quotes#poetry#spilled ink#american novels#science fiction#parable of the talents#octavia butler#female authors#black authors

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

From von Bertalanffy’s “system of systems,” LeClair derived six criteria to define the genre. (1) Systems novels respond to “accelerating specialization (and alienation) of knowledge and work”; “tremendous growth in information and communications”; “large-scale geopolitical crises over energy and exchange (of goods information and money); and “planetary threats produced by man yet now seemingly beyond his control.” (2) They bridge the gap between C. P. Snow’s “two cultures,” the literary and the scientific. (3) “The themes of systems theory are the master subjects of literary modernism—process, multiplicity, simultaneity, uncertainty, linguistic relativity, perspectivism—but in a new larger scale of spatial and temporal relations (the ecosystem) that reflects the new scale of sociopolitical experience, including the rise of multinational corporations and global ecology.” (4) In terms of character, “‘Systems man’ is more a locus of communication and energy in a reciprocal relationship with his environment than an entity exerting force and dictating linear cause-effect sequences.” (5) Systems theory “offers the novelist a contemporary model for hypothetical formulations of wholes.” (6) Systems theory provided a “a doubled or split relation to the idea of mastery, criticizing man’s attempt to master his ecosystem and yet, in its on synthetic act, ‘mastering’ various specialties in large abstractions in order to communicate beyond specialties.”

I have quoted liberally from LeClair’s original formulations to give a sense of the way that in setting new terms for the understanding of these novels he was deviating from the ordinary modes in which we talk about novels. Part of his project was to bring fresh academic attention to DeLillo, whom he saw as neglected by scholars, and so he sought the razzle-dazzle of a theory yet to infiltrate English departments, one that brought with it fresh jargon. It turned out we could talk about these books and understand them in a way close to that which LeClair intended without resorting to this language. Novels teach you how to read them, and they teach novelists how to write more novels. I have tried to reformulate LeClair’s theses on my own in the simplest terms: (1) too much information; (2) the inescapability of science; (3) the incomprehensible scale of things; (4) the limits of any man’s perceptions; (5) the need to see things whole; (6) the impossibility of mastery even when it’s the artist’s duty.

It could be argued that these conditions have applied to any novelist or writer of extended narratives at any time in the history of the form. Wasn’t Dickens synthesizing massive amounts of information? Didn’t Shakespeare have to consider science or cosmology? Wasn’t Nick Carraway telling a story whose historical dimensions he couldn’t entirely grasp? Didn’t Herman Melville and George Eliot aspire to put the whole world into their novels? Hasn’t total mastery eluded every writer from Homer down to Joyce and Beckett? Novels emerge from a long cyclical tradition. Since LeClair coined the term critics have recast the systems novel as a return of the encyclopedic novel or as the maximalist novel, terms of long standing that can easily be projected into the past. But the differences between these terms are useful to discern. An encyclopedia is a container of knowledge that seeks to include everything and organize it. Its mode of organization is arbitrary: the alphabet. The maximum is simply a term of scale: everything will be as big as possible. But the system will not only accommodate everything but also its movement and change. The theory comes from a biologist, and the metaphor accommodates living things, even living things moving deathward.

Christian Lorentzen, Shocks to the System: Don DeLillo’s novels of the Cold War and its aftermath

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Wisdom is knowing what you have to accept." --Wallace Stegner, Angle of Repose

1 note

·

View note

Text

#interview with the vampire#what we do in the shadows#astarion#vampire chronicles#vampire the masquerade#anne rice#dracula novel#dracula#first kill#castlevania netflix#castlevania#queer vampires#vampires#carmilla#not quite dead#buffy the vampire slayer#supernatural#the hunger#daughter of darkness#true blood#american horror story#american horror story hotel#the vampire lovers#underworld 2003#lgbtq#queer media#pride#meme#lgbt memes#vampire memes

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

A very happy Quincey P. Morris Day to all who celebrate! At last it is time to, as Bram Stoker's notes put it,

Bring in the Texan

#the absolute final boss of 'That one American character in a Victorian novel' and bless him for it#Dracula#Dracula Daily#Quincey P. Morris

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

almost heaven

#september#almost heaven#rust#west virginia#small town gothic#appalachia#wip: almost heaven#hansburg#margo#americana#abandonedcore#aesthetic#small town america#appalachain gothic#new england gothic#photography#rotting#rural aesthetic#abandoned#backroads#dark#autumn#green#lost places#rural gothic#american gothic#novel#writers

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pagan Rabbi, and Other Stories :: Cynthia Ozick

View On WordPress

#0-4363-5480-2#american fiction#american jews#american novels#american short stories#american stories#books by cynthia ozick#carol smither#fictional jews#first edition books#jewish fiction#jewish literature#jewish novels#jewish stories

0 notes

Text

A true war story is never about war. It's about sunlight. It's about the special way that dawn spreads out on a river when you know you must cross the river and march into the mountains and do things you are afraid to do. It's about love and memory. It's about sorrow. It's about sisters who never write back and people who never listen.

The Things They Carried, Tim O'Brien

#the things they carried#tim obrien#books#quotes#book quotes#book quote#bookworm#american novels#american writer#read this#war#war books#literature#classic books#classic literature#classic quotes#classic novels

19 notes

·

View notes

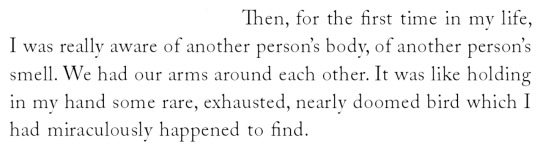

Photo

James Baldwin, from Giovanni’s Room

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

"But those [the world] will not break, it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too, but there will be no special hurry."

Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms (1929)

#quotes#literature#lit#spilled ink#american literature#1920s literature#novels#american novels#world war 1 novels#ernest hemingway#a farewell to arms#american classic

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone needs to do an analysis on the way the Kung Fu Panda movies use old-fashioned vs. modern language ("Panda we meet at last"/"Hey how's it going") and old-fashioned vs. modern settings (forbidden-city-esque palaces/modern-ish Chinese restaurant) to indicate class differences in their characters, and how those class differences create underlying tensions and misunderstandings.

#This is neither a criticism nor a compliment of that artistic choice#I just think it's really interesting#Like even looking at the Five:#Tigress talks in an older style than the others because she was mainly raised at the Jade Palace#While Mantis talks like Joe-schmo off the street because he *was* a streetfighter and an ordinary guy#Shifu and even Tai Lung talk like they're from an old-fashioned novel or kung fu movie#Po talks like a modern guy you'd meet working in a twenty-first century family restaurant#Part of Tigress's initial disdain for him in the first movie is clearly because she considers him to be low-class/a commoner#(And therefore an intruder into the world of the Jade Palace and the rest of the Kung Fu masters which appears to be semi-noble).#Shen looks genuinely off-put and disgusted when he has to respond to Po's greeting with a “...hey.”#And when Po wants to appear more legitimate as a warrior he adopts a more “legendary”/old-fashioned way of speaking.#In the aesthetic language of KFP old fashioned=noble/upper class and modern=common/lower class.#This translates entirely naturally—I think especially to an American audience—but it is wild once you notice it#Because you realize: “Hang on—shouldn't *all* these characters be talking like they're living in the medieval era?”#“And what does it mean that they're not? What is the movie attempting to convey with this—probably entirely subconscious—artistic choice?”#kung fu panda

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

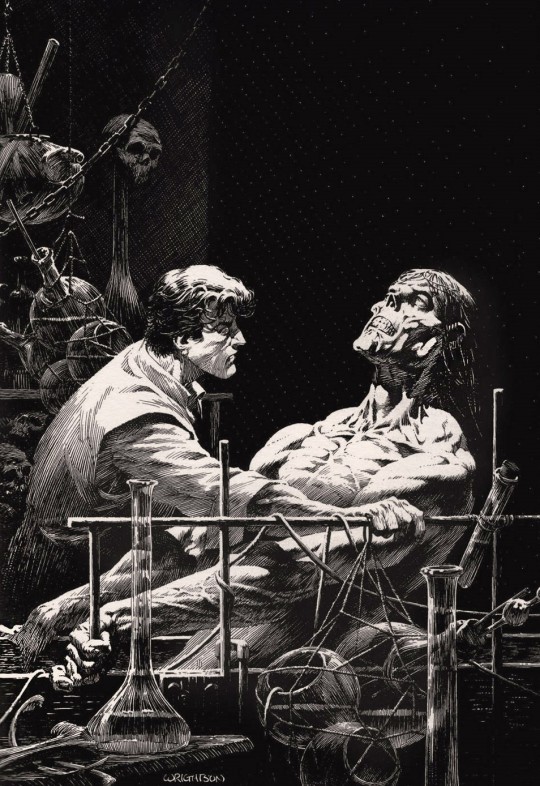

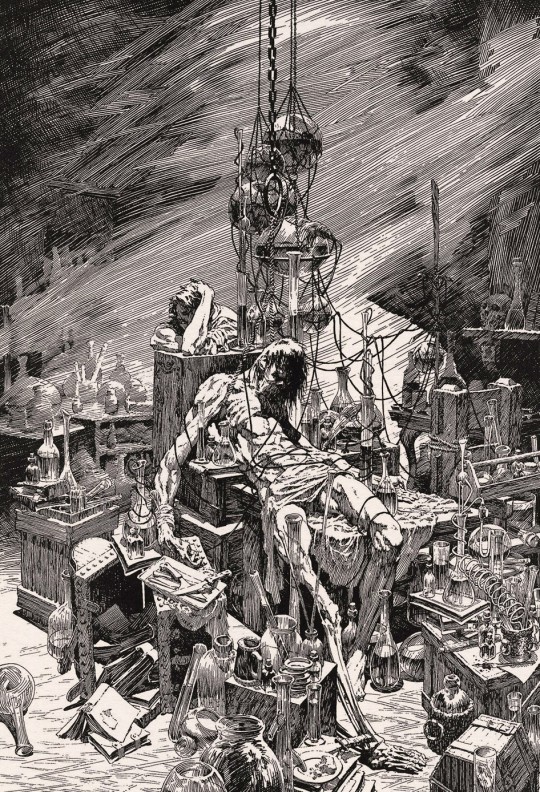

Illustrations from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein by Bernie Wrightson (1983)

#bernie wrightson#art#illustration#1980s#1980s art#vintage art#vintage illustration#vintage#american art#american artist#american illustrators#graphic novel#mary shelley#frankenstein#horror#horror art#classic art

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Great novel.

This an excellent book. People wanted it banned because of the message it sent.

150 notes

·

View notes