#Abd el Krim

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

EDGAR NEVILLE. RETRATO DE UN ARISTÓCRATA HEDONISTA

Se han cumplido 125 años del nacimiento de Edgar Neville Francisco R. Pastoriza Por allí por donde aparecía Edgar Neville la gente tenía que apartarse, dejar espacio al paso de la corpulenta anatomía de aquel eterno gentleman de vientre prominente que solía vestir pantalón de franela y una chaqueta azul marino con botones dorados de cuyo bolsillo superior asomaban las puntas de un…

#Abd-El-Krim#Benavente#Charles Chaplin#Conchita Montes#Dionisio Ridruejo#Edgar Neville#Emilio Prados#García Lorca#Hermanos Quintero#Jardiel Poncela#José López Rubio#Luis Buñuel#Manuel Altolaguirre#Manuel Azaña#Manuel de Falla#Mingote#Ortega y Gasset#Ramón Gómez de la Serna#Sean Connery#Tono

0 notes

Photo

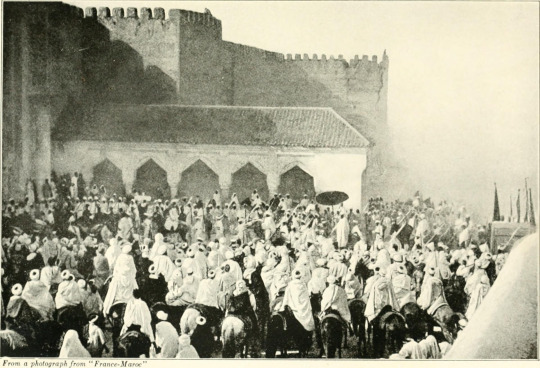

The Spanish protectorate in Morocco, 1912-1956.

“Breve atlas de historia de España”, Juan Pro, Manuel Rivero Rodríguez, Alianza ed., 1999

“Atlas de Historia de España”, Fernando García de Cortázar, Planeta, 2005

by cartesdhistoire

At the end of the 19th century, France sought colonial rule over the Sultanate of Morocco. In order to avoid conflict with Great Britain, which would not accept France disputing control of the Strait of Gibraltar, France agreed to divide the territory with Spain (1902 agreement). Meanwhile, Germany positioned itself as the Sultan's defender to safeguard its commercial and financial interests. At the Algeciras Conference (1906), Spain expressed interest in dividing Morocco into "zones of influence" and promoted the penetration of its companies in the north. However, this area of Morocco was the poorest, and it was challenging to develop mining businesses there, especially after successive negotiations restricted the Spanish area to the Rif mountain range.

In 1912, Morocco was divided into two protectorates, assigned to Spain and France, as a result of an agreement with Great Britain and Germany. This agreement aimed to save the theoretical independence of the Sultan and exclude Tangier as an international city. However, effectively occupying the Spanish area required a disproportionate military effort. It was a rugged region inhabited by "kabyle" warriors who had already successfully confronted the Spanish army since the Barranco del Lobo disaster in 1909. Under the leadership of Abd-el-Krim, they took up arms against the Spanish penetration, inflicting severe defeats (Annual disaster, 1921). The occupation became a matter of prestige and was only completed under the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, with the help of France, during the Alhucemas landing in 1925.

Morocco yielded almost no profits but required an occupying army, whose rebellion against the Second Republic helped determine the fate of the Civil War.

Independence was granted in 1956 when France decided to abandon its part of the country.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Strauss as Sergeant Otto Josef Klems and Tina Aumont as Leila, Abd el-Krim's daughter in Sergio Grieco's film "Il Sergente Klems", 1971.

Japanese program from ebay.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Materiel lost by the Spanish, in the summer of 1921 and especially in the Battle of Annual, included 11,000 rifles, 3,000 carbines, 1,000 muskets, 60 machine guns, 2,000 horses, 1,500 mules, 100 cannons, and a large quantity of ammunition. Abd el Krim remarked later: "In just one night, Spain supplied us with all the equipment which we needed to carry on a big war."[25]

According to the report, intelligence gathered by weapons experts, Israeli and Western officials has revealed that “Hamas has been able to build many of its rockets and anti-tank weaponry out of the thousands of munitions that failed to detonate when Israel lobbed them into Gaza”. “What is clear now is that the very weapons that Israeli forces have used to enforce a blockade of Gaza over the past 17 years are now being used against them,” the report said.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuando la figura de Abd-el-Krim sobrevoló América Latina

Por Leandro Albani

Fuentes: El Salto

A lo largo del siglo XX, las relaciones entre el pueblo rifeño del norte de África y América Latina fueron escasas, pero estuvieron marcadas por las luchas de liberación nacional y los intentos de derrotar al colonialismo en ambos continentes.

“Os hablo como hermanos, porque la sangre española que corre en vuestras venas es en gran parte sangre árabe, como la de todos los españoles del sur de la península que salieron de Palos, de Sevilla, de Cádiz, para sembrar en vuestra América el alma árabe que resucitó en los gauchos y en los llaneros, aunque encubierta por los signos de otra religión”

A principios del siglo XX, la lucha del pueblo rifeño, la fundación de su República después de derrotar a la España que colonizaba esas tierra del norte del actual Marruecos y la figura de un desconocido Abd-el-Krim, cruzaron el océano Atlántico y repercutieron en América Latina. Varias décadas después, la guerra de guerrillas desarrollada por las tribus al mando de el-Krim se convirtió en una de las técnicas que aprendieron los hombres liderados por Fidel Castro antes de desembarcar en Cuba, en diciembre de 1956. En poco más de dos años, desde la Sierra Maestra, en el oriente cubano, el Ejército Rebelde desató una guerra de guerrillas que hizo morder el polvo a la dictadura de Fulguencio Batista. El 1 de enero de 1959, Fidel y sus guerrilleros tomaron el poder e iniciaron una revolución que impacta hasta el día de hoy.

Para España, el año 1921 significó su principal derrota militar en su larga historia. El denominado “Desastre de Annual” se produjo en el Rif. La población amazigh de ese territorio, bañado por el mar Mediterráneo, donde la aridez y las montañas conforman un paisaje que a finales del siglo XIX se consideraba inhóspito, encabezó una guerra demoledora para el reino español. Encabezado por Abd-el-Krim, el pueblo rifeño le dio un golpe mortal al ejército ocupante, encargado de la colonización del territorio desde 1912.

La ocupación de las tropas españolas en el Rif no fue bien recibida, sobre todo porque lo primero que hicieron fue construir iglesias y sobornar a jefes tribales para que aceptaran el plan colonizador. Como si fuera poco, España no desarrolló industrias ni creó nuevas infraestructuras en la región. La colonización fue puramente militar. Y el pueblo rifeño fue anotando los sufrimientos que España multiplicó por sus tierras. Abd-el-Krim, que se desempeñaba dentro de la administración española ocupante, también registró las injusticias contra su pueblo. Luego de conocer la prisión en 1915, el futuro líder rifeño comprendió que sus coterráneos tenían derecho a ser libres y su tierra a convertirse en una República libre y soberana.

El mensaje a los pueblos latinoamericanos

En diciembre de 1924, la revista Renovación, editada en Argentina, publicó un mensaje de Abd-el-Krim a los pueblos de América Latina, donde el líder rifeño mostró un conocimiento profundo sobre la realidad del continente y en un puñado de párrafos convocó a luchar por la independencia. Además, reflexionó sobre la presencia del Islam en Europa y los vasos comunicantes entre los pueblos de África y América Latina.

El mensaje se dio en el marco del centenario de la Batalla de Ayacucho, una de las confrontaciones bélicas más importantes de las guerras de independencia en América del Sur (que transcurrieron entre 1809 y 1826). El también conocido como “Grito de Ayacucho” permitió la consolidación de la independencia de la República de Perú.

En ese texto, Abd-el-Krim escribió que no existe nada “más sagrado y respetable que el derecho de los pueblos a regir sus propios destinos, dándose las leyes y las formas de gobierno”.

El-Krim aseguró que el pueblo de Marruecos, en plena década de 1920, luchaba con los mismos ideales que los venezolanos Francisco Miranda y Simón Bolívar, y los argentinos Mariano Moreno y José de San Martín. También manifestó que “ayer no más nuestros corazones seguían emocionados por la última gesta de los Maceo y los Martí” en Cuba, quienes bregaban por la independencia total de la isla. “Así como vosotros hace un siglo luchasteis por formaros una nacionalidad propia, nosotros estamos dispuestos a sacrificar vida y haciendas para constituirnos en pueblos libres”, resumió el entonces Regente Provisional de la República del Rif.

“El glorioso día de Ayacucho existe para todos los pueblos oprimidos —dijo el líder rifeño—. Estamos seguros de ello y millones de nuestras vidas serán pocas, si es menester, para pagar el precio de nuestra libertad”.

En el mensaje, Abd-el-Krim apuntó contra la “Europa corrompida” en tiempos de la Primera Guerra Mundial, desencadenada, según la máxima autoridad del Rif, “por el imperialismo propio de su régimen capitalista”.

El líder rifeño también posicionó a los pueblos de Egipto y Marruecos a la vanguardia de la lucha por la liberación en África, y en toda su escritura sobrevolaba la necesidad urgente de la unidad para alcanzar la independencia. El-Krim llamó a “a sacudir el yugo de Inglaterra y de Francia, de Italia y de España”, lo cual desembocará en procesos independentistas en Argelia, Túnez y Libia.

“Nuestra causa es tan justa como antes lo fue la vuestra. No nos mueve particularmente odio a España, que en otro tiempo fue patria nuestra y cuna de nuestros abuelos”, reflexionó el dirigente, que a su vez defendió la influencia árabe en España, la cual, según su visión, fue truncada en “la hora fatal en que una guerra religiosa causó nuestra expulsión de la península hermoseada por nuestras artes y enriquecida por nuestras industrias”. El-Krim además criticó a “las castas militares y católicas de España” que arrastraron a su pueblo “a una guerra insensata y desastrosa que ha hecho de Marruecos el cementerio de sus hijos y el pozo sin fondo de sus presupuestos bélicos”. Como sucede en cualquier guerra hasta nuestros días, el líder rifeño remarcó que al norte de África se enviaba a “morir a los pobres españoles como hace cien años se los mandaba a morir en los valles de los Andes y hace treinta años en las maniguas de Cuba”. Frente al colonialismo español en el Rif, Abd-el-Krim manifestó que en su pueblo estaban “repugnados por tanta matanza y deseamos que los españoles desistan de su inútil heroísmo, evacuando Marruecos como evacuaron vuestra América, para dejarnos emprender la obra de paz, de trabajo y de enseñanza que nos permitirá formar naciones tan dignas como las que vosotros habéis formado”.

En el último fragmento del mensaje, el líder rifeño lamentó no poder enviar a América Latina una “embajada especial a las fiestas de Ayacucho glorioso”. Antes de que su firma como “Regente Provisional de la República del Rif” concluya la carta, el-Krim expresó su deseo de establecer con los pueblos del continente “unas firmes relaciones fundadas en el amor y la fraternidad, antes que la hipocresía convencional de la presente diplomacia del imperialismo capitalista”.

“El hombre de férrea voluntad”

En esas páginas, la lucha del pueblo rifeño y la figura de Abd-el-Krim aparecieron en tres ocasiones. En la primera edición de la revista, en un recuadro en la portada, se rescató que el “primer resultado que ha tenido el avance de Abd-el-Krim en la zona francesa, es el de que los obreros indígenas exigieron la jornada de ocho horas, y en verdad todo el movimiento en Marruecos tiene más carácter de lucha proletaria que de guerra imperialista”. A continuación se señaló: “Por eso la Francia llena de cañones y elementos de guerra sus protectorados, porque para ella es preferible todo, antes que los obreros indígenas tengan jornadas de ocho horas y salarios humanos”.

Con un tono crítico y duro, desde Revista de Oriente afirmaron que un “pueblo que no ha podido ser imbecilizado por el clericalismo español, ni por la brutalidad militar, es un pueblo de ideales y de cultura propios dignos de triunfar. Esta vez tenemos fe en las fuerzas del derecho y esperamos que los pueblos de Europa pidan maestros a Abd-el-Krim para civilizar a sus gobiernos”.

En el número 3, de agosto de 1925, la revista publicó un artículo a doble página bajo el título de “Marruecos” donde se presentaba un análisis de la crisis del capitalismo en Europa después de la Primera Guerra Mundial. Después se refirió a Marruecos y los descubrimientos de minas que atrajeron “las codiciosas miradas del capitalismo europeo”, tras lo cual “la garra imperialista europea se dejó sentir en todo el norte africano”. También se remarcó que pese al coste humano y económico de España y Francia, “la parte central y norte (de Marruecos), nunca fue dominada”.

A su vez, se describió la constitución de la “Compañía Española de Minas del Riff”, que tenía “entre sus más fuertes accionistas a Romanones, los jesuitas y el Rey”. Sobre la ocupación española del Rif se mostró el siguiente ejemplo: “España tiene unos 22.000 kilómetros cuadrados con Melilla, Ceuta y las minas de Beni-Tex-Ifrur”.

Al referirse al líder rifeño, se describió la historia de Abd-el-Krim como burócrata de la administración española que ocupaba el Rif, de quien se dijo que comprendió que “para vencer a los opresores de su pueblo, era necesario algo más que bravura y heroicidad, que era indispensable una constante y consciente labor de estudio, y una preparación orgánica lo suficientemente hábil y adecuada que le permitiera utilizar las más modernas invenciones y métodos, sin los cuales sabía que era utópico pensar en el éxito”. “Para eso sacrificó largos años de su vida —remarcaron en el artículo—, los que le permitieron ver todo el mecanismo, estudiar todas sus fallas, y llegar al convencimiento de que a esos ejércitos que les faltaba la columna vertebral de un ideal popular, no podían resistir a un puñado de los suyos que además de modernos fusiles y abundantes cartuchos llevaban el firme propósito de vencer y libertarse”.

Desde la revista también apuntaron que frente a la liberación del Rif “los ‘izquierdistas’ franceses no trepidan en lanzarse contra Abd-el-Krim en una nueva guerra de ‘defensa y de justicia’. Sin duda es esta la primera guerra típicamente colonial que ha debido emprender Francia, después del Tratado de Versalles y ante la cual, los socialistas franceses han tomado la más alta defensa del belicoso capitalismo nacional, votando la declaración favorable a la continuación de la lucha y manifestando que ‘saludan agradecidos a las valerosas tropas francesas e indígenas que están defendiendo la obra de Francia’”.

En el número 4 de la Revista de Oriente, de octubre de 1925, en una doble página utilizada para fotogalerías, apareció el líder rifeño, con un epígrafe que lo describió como el “que manda a las fuerzas marroquíes y tiene en jaque a los potentes imperialismos, francés y español”. Al lado, más pequeña, se ve una foto del hermano de Abd-el-Krim, al que se señaló como el jefe “al frente actualmente de las tropas que tomaron Xauen y Tetuán”.

Del Rif a Cuba

“Bayo no rebasaba las enseñanzas de cómo debe actuar una guerrilla para romper un cerco, a partir de las veces que los marroquíes de Abd-el-Krim, en la guerra del Rif, rompieron los cercos españoles”. La anécdota la relató Fidel Castro al periodista Ignacio Ramonet para su libro Cien horas con Fidel, publicado en 2006. Fidel había conocido a Alberto Bayo en México, cuando el dirigente cubano reunía y preparaba al grupo que luego desembarcó en las costas de la isla caribeña. En tierras mexicanas, el ex militar español se había sumado al proyecto de Fidel como instructor militar. La guerra de guerrillas era la especialidad de ese hombre que, entre 1916 y 1927, participó en diferentes momentos junto a las tropas españolas en el Rif y luego se encolumnó en la defensa de la República durante la Guerra Civil en España.

“Che era un alumno asiduo en todas las clases tácticas —contó Fidel—. Bayo decía que era su ‘mejor alumno’. Los dos eran ajedrecistas y, allí en el campamento, echaban todas las noches grandes partidas de ajedrez”.

El encuentro entre Fidel y Bayo fue en la capital mexicana. El veterano español tenía 60 años, el futuro líder cubano todavía no llegaba a los 30. En 1955, el ex militar había publicado 150 preguntas a un guerrillero, un libro fundamental para el futuro de las insurgencias latinoamericanas, inspirado en la lucha encabezada por Abd-el-Krim. En un artículo aparecido en Le Monde Diplomatique en 2013, Antonio Palerm escribió: “Bayo fue uno de los pocos militares españoles que simpatizó con los resistentes rifeños, a quienes amparaba, según su criterio, la razón histórica. Por ello, de vuelta a España, se afilió a la UMRA (Unión Militar Republicana Antifascista). Cuando estalla la Guerra Civil, el 18 de julio de 1936, le encontramos destinado en el Prat de Llobregat”.

Para Ernesto Guevara, las enseñanzas de Bayo no fueron menores. En el prólogo que escribió al libro Mi aporte a la revolución cubana, publicado por el ex militar en 1960, el Che afirmó: “Del general Bayo, quijote moderno que sólo teme de la muerte el que no le deje ver su patria liberada, puedo decir que es mi maestro”. En esas enseñanzas resplandece la figura del Abd-el-Krim.

Entre junio y septiembre de 1959, luego del triunfo de la revolución cubana, el Che viajó por Asia, el norte de África y Yugoslavia. El proceso encabezado por Fidel Castro necesitaba tender puentes para lograr un respaldo sólido a sus propuestas incipientes de socialismo. Por esos años, el liderazgo de Gamal Abdel Nasser iluminaba desde Egipto a todos los países de mayoría arabe. El gobierno nasserista enfrentaba a Israel y a Estados Unidos sin dobleces. A ese país en ebullición había llegado exiliado Abd-el-Krim luego de conocer —una vez más— la persecución, y sufrir la caída de la República del Rif debido a la campaña militar de España y Francia contra la joven nación.

Según diversas fuentes, cuando el Che llegó a Egipto solicitó reunirse con el líder rifeño. Algunos apuntaron que el propio Bayo fue quien facilitó el contacto para ese encuentro. En el artículo de Le Monde se indicó que ambos dirigentes pasaron toda una tarde juntos: “Sus intercambios eran en español, idioma que Abdelkrim dominaba a la perfección, además del amazigh, su lengua materna, el árabe, e incluso el francés y el inglés”.

En 2017, en un artículo firmado por Luis Agüero Wagner y publicado en el diario Siglo XXI, el autor sostuvo que el 14 de junio de 1959, el mismo día que cumplía 31 años, el Che “decidió hacerse a sí mismo un obsequio en El Cairo”. Agüero Wagner explicó que el facilitador del encuentro fue Abdallah Ibrahim, quien gobernaba en ese entonces en Marruecos, a través del embajador marroquí en Egipto, Abdelkhalek Torres. Otras fuentes indicaron que el propio Ibrahim le contó sobre la reunión entre el Che y El-Krim a Mohamed Louma, compañero de lucha del dirigente político marroquí Mohammed Basri. Según esta versión, el comandante argentino-cubano y el líder rifeño departieron en el jardín de la embajada de Marruecos en la capital egipcia. Al crecer el mito de esta reunión, algunos dicen que los encuentros se repitieron al menos en dos ocasiones más. Otros apuntan que el Che le regaló un bolígrafo a El-Krim. En el documental Het verhaal van Abdelkrim, Ahmed Morabit cuenta que existe una foto en el que se ve al Che sentado en el piso, escribiendo, y a su lado, sentado en una silla, a Abd-El-Krim. “Como un maestro con su alumno”, sentencia Morabit.

El líder rifeño, nacido en 1882, falleció en 1963 en El Cairo, donde el gobierno organizó un funeral nacional para despedirlo, debido a su compromiso con las luchas independentistas de África. Cuatro años después, caía en combate Ernesto Guevara en Bolivia, donde impulsaba una nueva guerrilla para expandir la revolución por toda Latinoamérica. Abd-el-Krim y el Che soñaron con un mundo donde las cadenas del colonialismo fueran pulverizadas por los pueblos oprimidos. Ambos dejaron sus vidas en esa empresa.

Fuente: https://www.elsaltodiario.com/historia/cuando-figura-abd-krim-sobrevolo-america-latina

#áfrica#che guevara#imperialismo#descolonización#américa latina#nuestramérica#historia#guerra de guerrillas

1 note

·

View note

Text

Worldbuilding | Morocco, 1920

Trauma

In the 1920s, Morocco was not having a particularly good time. In 1921, tension between colonial Spanish forces and Rif peoples in northern Morocco culminated in a series of guerrilla attacks led by Berber leader Abd el-Krim on Spanish fortifications in June–July 1921. Within weeks, Spain lost all of its territory in the region. This would come to be known as the Rif war. The Rif War lasted from June 1921 to May 1926, when Spanish forces regained the territory they had lost in 1921 and subsequently "won." About 43,500 Spanish troops were killed or wounded or went missing during the war; Spain’s ally France counted about 18,000 as killed, wounded, or missing. Rif casualties may have been about 30,000, with 10,000 killed.

The Rif War was the last major confrontation during several centuries of conflict between the Rif peoples of northern Morocco and the Spanish. Historians debate whether the Rif War is better understood as a secular insurgency against a colonial power or a war in defense of Islam and Berber independence. The war was mainly fought in the northern mountains of Morocco, known as the Rif, however it is not considered to be part of the Atlas Mountain System.

In addition to this, the French colonials settled in 1912, which would come to be known as the French protectorate in Morocco or more simply, French Morocco. France established a protectorate over Morocco as a result of the signing of the Treaty of Fez on March 30, 1912. Prior to 1912, Morocco had been an independent kingdom for several centuries. This would last for 46 years, until 1956.

Geography

North Africa has three main geographic features: the Sahara desert in the south, the Atlas Mountains in the west, and the Nile River and delta in the east. The Atlas Mountains extend across much of northern Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. The most notable of these is the Sahara desert.

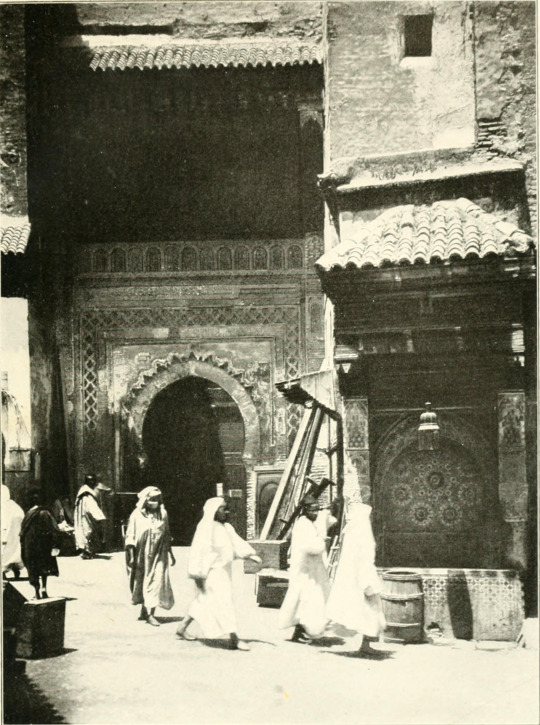

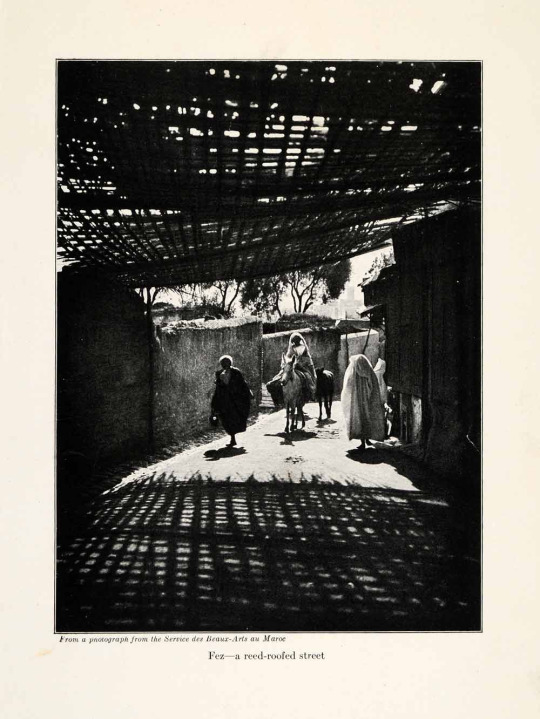

Architecture

Moroccan architecture in the 1920s incorporated natural elements like stucco, tilework, pise, brick, and marble, which provided beautiful, durable foundations. Tilework is often used to create colorful mosaics that can be used to decorate floors and walls, as well as significant areas in mosques or courtyards, like fountains. The Amazigh built traditional kasbahs and fortifications in the high mountains and desert. Their architectural style is characterised by imposing buildings made from pise, or red mud clay bricks that have been dried in the sun. Additionally, it was not uncommon to see reed-roofed streets and intricately decorated structures whilst walking through town. This ancient Moroccan architectural style is most prevalent in the Atlas Mountains. There, Amazigh villages and kasbahs made with red clay bricks that make a striking contrast to the blue sky. One of the most impressive is Ait Benhaddou in Ouarzazate. Built in the 1600s, this fortified village is made of clay buildings surrounded by defensive walls. The sheer size and asymmetrical structure of this village make it a truly spectacular site.

Morocco had witnessed a long line of invaders including Saharans, Phoenicians, Romans, Greeks, Byzantines, Ottomans, Arabs, Spanish and French. The region was conquered by Muslim Arabs by the 7th century and since then, Islam had the most significant impact on Moroccan architecture. Islamic architecture is highly decorative and functional, characterised by geometric patterns, tiles, fountains, horseshoe arches, and floral arabesques carved into stone or wood. Traditional Moroccan tiles (Zellij) were introduced, with spectacular geometric tiles lining the interiors and exteriors of buildings across Morocco. The classic colours are green, blue, brown, white, and black. Fountains are an integral part of Islamic Moroccan architecture, as they represent paradise. They’re also a place where Muslims can perform purification rituals before prayers. By the 8th century, the Moors were greatly influencing Moroccan architecture. The Moors occupied parts of Spain and Morocco for centuries, so aspects of Spanish architecture became entwined with Islamic and African influences. Some distinctive Moorish influences include the white stucco facades, red-tiled roofs, and elements from Art Deco and Art Nouveau styles. The Moors were also known for their clover-shaped and cusped arches, interior garden courtyards, and hand-glazed tiling.

When the French colonised South Morocco from 1912 to 1956, they introduced elements of French design to Moroccan architecture. One of the most distinctive changes was the windows. While Berber and Islamic architecture used small windows, the French brought in their large double French doors and windows. The French also introduced restrictive building standards. They decreed that buildings could not be higher than four stories and all building roofs should be level and flat. Balconies could not overlook neighbours and each planned area should have 20% of the land dedicated to outdoor gardens or courtyards. While these policies were aimed at preserving the country’s existing traditional architecture, they also stalled urban development in many areas and repressed architectural innovations.

0 notes

Text

MARRUECOS: ¿MOVILIZAR AL EJÉRCITO? General de División (R.) Rafael Dávila Álvarez

MARRUECOS: ¿MOVILIZAR AL EJÉRCITO? General de División (R.) Rafael Dávila Álvarez

Aquí nadie sabe lo que hay que hacer. Si atacar o defenderse. Si por tierra, mar, aire o por los tres sitios a la vez. Si hacer la guerra a Marruecos o hacérsela a Gibraltar, o a la ONU que se calla, o a Europa que alguien le ha dicho a última hora que es su frontera, la de la OTAN. Ahora por todas partes surgen los guerreros del antifaz que muestran su ardor guerrero. «España defenderá la…

View On WordPress

#Abd el Krim#blog generaldavila.com#Ceuta#ceuta y melilla#cni#el arte de la guerra#españa en taifas#fronetra de letonia turquia#guerra a marruecos#la crisis#la otan#la republica del rif#las fuerzas armadas#Marruecos#Melilla#rafael davila alvarez#sanchez presidente#sunzi#Trump

0 notes

Text

oh he hated his fucking guts 😭😭😭😭

En aquellos tiempos estaba de Alto Comisario allí don Dámaso Berenguer, y de ayudante un hermano suyo, no recuerdo el nombre. Nos mató 21000 soldados y no sé cuantos hombres y mujeres y hasta se oyó decir que también liquidaba a los niños. También nos cogió mil y pico de prisioneros, entre ellos a un primo segundo mío que se llamaba Fernando Gómez que años después se cayó aquí de la obra que estaba de albañil y se mató. Entre los muertos [estaba] otro primo segundo mío, no recuerdo el nombre. Entre los prisioneros estaba el General Silvestre. ¿Qué labor hacía Berenguer allí que no tenía un buen servicio de información para darse cuenta de las maquinaciones de Adel Qrin [Abd el-Krim]? Creo que lo que hacían todos los jefes y oficiales: chupar del bote y aquí me las den todas [creo que es un refrán]. Se formó un tribunal de responsabilidades, que lo presidía el General Picasso, y quién estaría metido en él, que cuando iba a medio recibió órdenes de darle carpetazo y aquí no ha pasado nada. Esa orden no pudo ser de otro que no fuera el rey, que yo creo que era un imbécil.

my great grandpa is now writing about the rif war and how it was a shithole and various cousins of his died in it, and especially he's shitting on the one who was in charge there at that moment, a guy called dámaso berenguer. at first i was like whatever, this is just historical stuff i don't know enough about. until it hit me. the guy my great grandpa was dunking on was the berenguer. the dictablanda berenguer. that guy. lol.

#percalesdiary#also his diss at the king? slay#that's so me coded#i guess it runs in the family#btw things are about to get spicy !!! he is talking about alhucemas an franco and in the next page i saw the year 1931 which means#it's second republic timeeeee#i'm so excited to finally know what was his role in the civil war and what his views was#cause he was sentenced to death. they didn't do that to all rojos#so i'm curious

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember in 1921 when Spain had one of the most catastrophic defeats a colonial army ever faced, the scale of which caused so much turmoil in Spain that there were mutinied and the Spanish king had to abdicate and multiple governments would reform only to quickly collapse and France decided to enter the Rif War because the Spanish were in a state of collapse and Abd el-Krim described the sheer scale of the destruction of the Spanish army as "In just one night, Spain supplied us with all the equipment which we needed to carry on a big war." due to the massive amounts of weapons and supplies left behind

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

The End of Today in World War I

November 11 2021, Arlington--Three years beyond the armistice seems a good enough place to finally bring my coverage of the post-war events to a close. There are still plenty of loose (or, honestly, dropped) threads left over from the war that would continue more than three years past the armistice, and I would feel remiss if I just stopped here without providing at least some conclusion.

Russia:

The defeat of Wrangel in November 1920 ended the last major White threat to Soviet power in Russia, though localized threats on the periphery would continue for at least two more years. Makhno’s Black Army of anarchists in Ukraine, after a brief alliance with the Reds against Wrangel, were forced into exile by August 1921. The last Armenian resistance in the mountains southeast of Yerevan was crushed in July 1921. Georgia saw continued small-scale guerilla fighting and a large rebellion in August 1924, though this failed to take Tblisi and was swiftly crushed.

The Soviets had thought they had largely secured control over Russia’s former holdings in Central Asia with the fall of Bukhara in September 1920. However, guerilla resistance by the Basmachi movement continued. In November 1921, former Ottoman leader Enver Pasha arrived to assist the Soviets, but soon defected to the Basmachi in a misguided continuation of his wartime plans for a grand pan-Turkish state. Enver reinvigorated the Basmachis and they seized large portions of present-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The Soviets, in return, made political concessions to the Muslims in the area while simultaneously bringing the full might of the Red Army to bear. After suffering multiple defeats, Enver Pasha was killed in a foolhardy cavalry charge on August 4, 1922. Local Basmachi resistance would continue for another year or two, and occasional cross-border raids from Afghanistan for a decade after that.

In the Far East, Japanese withdrawal towards Vladivostok allowed the Soviets to secure the crucial rail junction of Chita in October 1920. Most of the remnants of Kolchak’s forces fell back with them (or left the country entirely), but General Ungern-Sternberg decided instead to invade Mongolia in an insane plan to restore the Mongolian Empire. In February 1921, he captured Ulaanbaatar from the Chinese and returned Bogd Khan to power, but he was ousted by the Soviets and Red Mongolian forces in July, and was captured and executed later in the summer. The Mongolian People’s Republic was established (with Bogd Khan kept as head of state until his death in 1924) and would remain until the end of the Cold War.

A brief White offensive took Khabarovsk, 500 miles north of in the winter of 1922, but they were repulsed by February. Vladivostok only fell to the Reds after the Japanese evacuated in October 1922. Some White resistance remained around Okhotsk until June 1923, and the Japanese did not fully withdraw from Kamchatka and northern Sakhalin until 1925.

On December 28 1922, with the Civil War all but over, the Soviet Union was officially created by the agreement of the Soviet governments in Russia, Ukraine, Byelorussia, and Transcaucasia.

North Africa:

Despite his great victory at Annual, Abd el-Krim was not able to push onto Melilla and eject the Spanish from the eastern Rif. A stalemate ensued, and a large faction in Spanish politics preferred abandoning Morocco entirely. In September 1923, General Primo de Rivera seized power in a coup and planned to pull back from Morocco, but under coup threats from junior officers, instead fortified the remaining Spanish positions. In 1925, Abd el-Krim’s forces invaded French Morocco, reaching as far as Fez. The French responded with overwhelming force with a large army under Pétain, along with aircraft, artillery, and chemical weapons, and Abd el-Krim surrendered in May 1926.

Egypt had nominally been an Ottoman possession (albeit under British administration) until the outbreak of World War I, and the end of the war saw increased demands for Egyptian sovereignty, leading to mass strikes and protests in the spring of 1919. These were crushed by the British, and the following negotiations with moderate Egyptian nationalists were inconclusive. Lloyd George wanted to maintain the protectorate, but in early February 1922 General Allenby, now British High Commissioner in Egypt, threatened to resign. On February 28 1922, the United Kingdom unilaterally declared the independence of the Kingdom of Egypt, but reserved power over Egypt’s defense, minority rights, “the protection of foreign interests in Egypt,” and Sudan. These reserve clauses would remain in effect until Nasser seized power thirty years later.

Turkey and Greece:

In the summer of 1921, the Greeks launched a major new offensive towards Ankara, hoping to decisively defeat Kemal’s Turkish nationalist government. However, the Greeks were largely alone in this effort; the French, Italians, and Soviets had all warmed to Kemal and conducted arms trades with (or, in the case of Soviets, gifted arms to) Turkey. The British were still friendly to the Greeks, but less so after Venizelos’ election defeat and King Constantine’s restoration to the throne. After fierce battles in August and September 1921 25 miles from Ankara, the overextended Greek forces were halted and forced to fall back. In October, the French signed a treaty with Kemal’s government, largely settling the modern-day border between Syria and Turkey (excepting the area around Alexandretta [İskenderun], which remained under French control until 1937 before joining Turkey after a disputed referendum in 1939).

The Allies, realizing that the Treaty of Sèvres was dead, were willing to renegotiate, but Kemal, having the upper hand militarily in Anatolia, refused. On August 26 1922, Kemal broke through the still-overextended Greek lines and pushed towards Smyrna [İzmir], reaching the city on September 9. A fire engulfed the Greek and Armenian parts of city in the following days. Over 150,000 refugees were evacuated to Greece, while tens of thousands more perished in the fire or were deported to the Anatolian interior. The stunning defeat led a revolution in Greece by the end of the month, returning pro-Venizelos forces to power and forcing King Constantine to abdicate for a second time, this time in favor of his first son, George; Constantine would die in exile a few months later.

With Smyrna secured, Kemal soon moved on towards the Straits and Constantinople. Lloyd George, Churchill, and a small number of Conservatives in the coalition government called for defending the Straits against Kemal, even if it meant war with Turkey. However, the other Conservatives, along with, in a notable change from 1914, Canadian PM Mackenzie King, were opposed to war. On October 11, the Allies agreed to an armistice with Kemal at Mudanya, in which the Greeks agreed to evacuate what is now European Turkey up to the Maritsa river. The wartime coalition in Britain broke apart, and Conservative Bonar Law became Prime Minister later in the month before winning an overall majority in elections the next month (which saw the Liberals, still split between Lloyd George and Asquith, relegated to third-party status behind Labour).

On November 1, the Turkish General Assembly dissolved the Ottoman Empire. Final peace negotiations for a treaty to replace Sèvres dragged on for months, but a treaty was finally signed in Lausanne on July 24 1923. Kemal’s government in Turkey was recognized by the Allies, with essentially its modern borders. The fate of Mosul was to be left to the League of Nations, which eventually decided in favor of Iraq in 1926. Civilian ships were allowed free passage through the Straits, and Turkey’s European border was to be demilitarized (on both sides). Related agreements between Turkey and Greece resulted in large-scale population transfers, with over 1.5 million Greeks from Turkey moved to Greece and 500,000 Muslims in Greece moved to Turkey. This did not apply to the Greek population in Constantinople (and a few Turkish islands), whose rights were recognized explicitly in the Lausanne treaty.

The Allies finally left Constantinople on October 4 1923, and Turkish forces entered the city two days later.

All efforts to prosecute those responsible for the Armenian genocide ended with Lausanne, though by this point the Armenian assassination campaign had killed many of the top leaders, culminating with the killing of Djemal Pasha in Tblisi in July 1922.

The Middle East:

Britain’s Hashemite allies, ejected from Syria by the French in July 1920, were given, effectively, consolation prizes in Britain’s new mandates in the Middle East. Feisal was made King of Iraq in August 1921 (after the British had suppressed revolts there the previous year), and his elder brother Abdullah Emir of Transjordan in April 1921. Their father, Hussein, remained in power in the Hejaz, and even declared himself Caliph after Turkey dissolved the Caliphate in 1924. However, his relations with the British deteriorated, as Hussein repeatedly refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles. With British support, the Saudi rulers of Nejd invaded Hejaz, taking Mecca without resistance in October 1924 and Medina and Jeddah fell in December 1925 and January 1926. The Saudis soon established a protectorate over Asir (home of the Idrisids, who had by this point been ejected from Yemen by Imam Yahyah), though fighting in the area would continue until the early 1930s, when the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was officially declared and Yemen signed peace treaties with the Saudis and the British.

Japan and China:

The day after the burial of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington, an international conference on arms limitation convened in Washington. After extensive negotiations (in which the Americans were aided by cryptologic successes against the Japanese), the UK, the US, and Japan agreed to a 5:5:3 ratio in battleships, and a limit in tonnage for battleships (both for individual ships and overall); France and Italy were limited to a 1.67 ratio. This averted an expensive naval arms buildup that some blamed for the buildup of tensions before the First World War. Japan agreed to give up its concession in Shandong (around Tsingtao), a huge win for China and the United States, though they remained economically dominant in the area. The United States recognized Japan’s claim to the island of Yap, and the Anglo-Japanese alliance dating from 1902 was officially dissolved. Further construction of fortifications in the western Pacific was forbidden.

The treaty had a mixed reaction in Japan; although the 5:3 ratio was much more favorable to Japan than the equivalent ratio of Japanese and US economic bases, it was still viewed as a snub in ultraconservative circles.

Eastern Europe:

A portion of western Hungary, including the city of Sopron, had been assigned to Austria by the Treaty of Trianon, and was due to be transferred in August 1921. However, elements of the local Hungarian population in Sopron resisted Austrian entry, and organized a plebiscite in December in which Sopron’s population voted by a 2-1 margin to remain in Hungary. This was ultimately recognized by the Allies, though the rest of the territory was transferred to Austria as planned.

On October 21 1921, the former Emperor Charles flew into Hungary in a monoplane, formed a provisional government in Sopron, and prepared to march on Budapest. Horthy, who was ostensibly serving as Charles’ regent, quickly organized a resistance and soon outnumbered Charles’ forces, as Hungary’s neighbors prepared for yet another invasion of the country. On November 1, Charles left for exile in Madeira, and within days parliament officially dethroned the Habsburgs (although Horthy remained as regent). Charles died of pneumonia in April 1922. His nine-year-old son, Otto, became the head of the Habsburgs in exile, and would remain so until his death in 2011.

Poland’s puppet Republic of Central Lithuania, based in Vilnius, held elections (boycotted by most of the non-Polish population) in January 1922; the resulting government asked to be annexed by Poland, which was granted in March. Lithuania refused to recognize this, and still claimed Vilnius as its capital. The Allies attempted to defuse the situation by offering the Lithuanians French-occupied Memel [Klaipėda] in exchange for recognizing Polish control of Vilnius. The Lithuanians refused, and the Allies prepared to make Memel a free port like Danzig. Instead, the Lithuanians staged a revolt in Memel (like the one the Poles had staged in Vilnius) in January 1923 and soon seized control of the city. The Allies protested, but acknowledged the Lithuanian presence as a fait accompli.

Ireland

On December 6 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed. Within a year, Ireland was to become the Irish Free State, a British Dominion in the same vein as Canada. Northern Ireland would have the option to withdaw (which it quickly exercised). King George V would remain as head of state, and members of the Dáil would have to swear an oath of loyalty to him. Britain would retain control of Berehaven, Queenstown [Cobh], and Lough Swilly, which would become known as the Treaty Ports. Ireland would assume an appropriate portion of the United Kingdom’s debt.

The Treaty provided for Irish independence, of a sort, but there was substantial opposition to the Treaty, lead by Eámon de Valera, who demanded nothing short of a fully republican Ireland. In April, anti-Treaty forces seized the Four Courts in Dublin. In June, the pro-Treaty forces won a convincing majority in the first Free State election. Four days later, Field Marshal Henry Wilson (formerly Chief of the Imperial General Staff), who was now a MP from Northern Ireland, was assassinated by the IRA in London. The British threatened to attack the Four Courts in response, but the Free State government (led by Michael Collins) pre-empted this by attacking the building themselves. After a week of fighting, the pro-Treaty forces were victorious; among the dead was anti-Treaty leader Cathal Brugha.

Although the Free State was securely in control of Dublin, a civil war broke out in the rest of the country, with anti-Treaty forces concentrated in the south and west. With British support, the Free State was able to defeat most of the anti-Treaty forces by the end of 1922, although Michael Collins himself was killed in an ambush in August. Guerilla fighting continued until a ceasefire in May 1923. De Valera ultimately took the oath and re-entered Free State politics in 1927.

Italy

The postwar period saw increased labor unrest and socialist activity. Mussolini’s Fascists took advantage of disappointment around Italian gains in the war and anti-socialist sentiment to first win seats in parliament in 1921, while his Blackshirts actively helped suppress strikes. In October 1922, he became aware that D’Annunzio was planning a demonstration to mark the 4th anniversary of the victory over Austria-Hungary on November 4, and decided to pre-empt it by organizing a march on Rome from Naples (although he himself drove). The King refused to take action against Mussolini, and instead made him Prime Minister.

Germany

The Germans signed the Treaty of Rapallo in April 1922 with the Soviets, normalizing their relations and beginning trade between the two countries. It also began secret military cooperation between the two countries, explicitly violating the Treaty of Versailles. Two months later, industrialist Walther Rathenau, who as Foreign Minster had arranged the treaty, was assassinated by the same offshoot of the Ehrhardt Brigade that had assassinated Erzberger the previous year.

On January 11 1923, in response to German defaulting on reparations payments in the midst of a hyperinflation crisis, France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr, despite opposition from the United Kingdom and the United States. On January 24 1923, the last American troops left the Rhineland. In August 1924, the Dawes Plan (drawn up by an American member of the Reparations Commission) was agreed to; it reduced reparations payments, offered American loans to Germany, and arranged for the French departure from the Ruhr within a year.

The occupation increased support for the far right in Germany. Taking inspiration from Mussolini’s success in Italy, Ludendorff and Hitler attempted their own version in Munich, the Beer Hall Putsch in October 1923, which failed within a day. After the ensuing trials, Ludendorff was acquitted, and Hitler ultimately only served one year in prison.

Hindenburg was elected President of Germany in 1925; Ludendorff, with whom he was once joined at the hip, was eliminated in the first round with barely 1% of the vote as the Nazi candidate.

In 1930, after the start of the Great Depression, German reparations were reduced yet again by the Young Plan, with additional financial backing provided by American banks. With German reparations payments apparently secure, the French withdrew from the Rhineland on June 30, 1930.

This post is already incredibly long, so I’ll spin the second half into a new post.

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1921 07 17 Igueriben - Ferrer Dalmau

Durante el avance del general Fernández Silvestre, comandante general de Melilla en la primavera de 1921, la posición de la colina de Igueriben protegía, junto con la de Talilit e Intermedias A y B, los alrededores de Annual, campamento base español. Fue establecida el 7 de junio y componían su guarnición 316 hombres, pertenecientes al Regimiento de Infantería de Ceriñola. Estaban apoyados por la 1.ª Batería del Mixto de Artillería con cuatro piezas Schneider, cuatro máquinas Hotchkiss de la compañía de ametralladoras de posición y varios soldados de la compañía de telégrafos de campaña, junto a un puñado de policías indígenas. A primeros de julio quedó al mando de la guarnición el comandante malagueño Julio Benítez Benítez.En el lienzo de Ferrer-Dalmau puede verse lo más característicos de la posición, tal y como la dibujó el único oficial superviviente de su defensa, el teniente Luis Casado, que años después escribiría un libro sobre lo sucedido: Un parapeto, que se inició con piedras de la propia colina a primeros de junio y que fue perfeccionado posteriormente por tropas de Ingenieros. Tenía, aproximadamente, la altura de un hombre, estaba aspillerado, coronado por sacos terreros y rodeado por una alambrada clavada sobre estacas de madera. En el centro del recinto se hallaban las clásicas tiendas cónicas, con funciones de puesto de mando, enfermería y dormitorio. A ambos lados de la entrada se situaban las ametralladoras, mientras que las piezas de artillería se emplazaron en la parte opuesta de la posición.Desde la primera semana de julio de 1921 se produjo en la zona, inesperadamente, la irrupción de un verdadero ejército de cabileños hostiles, liderados por Abd-el-Krim. Igueriben quedó cercada y hostigada por el fuego enemigo. El problema más grave para los defensores sería la falta de los víveres y el agua, que eran proporcionados periódicamente desde Annual y que el certero fuego de los rifeños obligó a interrumpir. Los de Igueriben fueron agotando los suministros, a la par que aumentaba el número de heridos. Ante la gravedad de la situación, se organizaron varios convoyes de auxilio, que, para ascender por aquellas serpenteantes sendas, tuvieron que marchar fuertemente escoltados. Hubo que desarrollar verdaderas operaciones de combate bajo un intensísimo tiroteo enemigo para conseguir alcanzar la posición.Nuestro artista ha representado en su obra la llegada del convoy de Igueriben del día 17 de julio de 1921. Iba compuesto por hombres del Parque Móvil de Artillería al mando del teniente Ernesto Nougués Barrera y de la 1.ª compañía de Intendencia del alférez Enrique Ruiz Osuna. Como escolta contaban con el escuadrón de Caballería de Regulares n.º 2 del capitán Joaquín Cebollino Von Lindeman. Las mulas transportaban, sobre todo, barricas con agua y algunas municiones para los cañones y las armas ligeras.La marcha del convoy resultó una auténtica odisea, en la que los Regulares fueron relevándose en un avance escalonado, ocupando una tras otra sucesivas alturas, bajo un intenso fuego de los harqueños que les produjo numerosas bajas de soldados y oficiales. Las proximidades de la posición estaban batidas eficazmente por un enemigo que disparaba agazapado y protegido desde la cercana Loma de los Árboles. Los últimos metros del avance fueron liderados personalmente por el capitán Cebollino. La columna consiguió alcanzar Igueriben gracias al fuego de apoyo y el sacrificio de los Regulares, pero también -y eso es lo que quería realzar en su composición nuestro pintor-, a la abnegación de los soldados de reemplazo.En el lienzo vemos a los defensores tras el parapeto, liderados por Benítez, que, como relata Casado, sin descanso dirigió la defensa, atendiendo a todos los frentes y elevando la moral de las tropas

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

the whole reason he wanted raise her to be brave, ruthless when needed and prudent in displaying kindness is that he wanted her to succeed in leading an uprising. he raised her to be as capable and prepared as possible and to greatly value their culture is so she could effectively fight and survive a fight against forced assimilation. saying he wanted her martyrized implies he expects her to die in the fight, which is such a. pessimistic view of anticolonial resistance movements. he didnt want her to be a joan of arc figure, but someone more like abd el-krim!!!

so sick and tired of the 'wilk set asirpa up to be martyrized' take

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

François Bernez-Cambot est né à Pau en 1901, c’est le troisième enfant d’une fratrie dont les deux aînés ont été tués pendant la grande guerre.

Il s'engage alors en 1920 dans les troupes coloniales. Nommé sergent le 1er mai 1924, au sein du 14ème régiment de tirailleurs sénégalais, il part au Maroc et participe à la guerre du Rif contre Abd el Krim. il y est désigné pour prendre le commandement d'un poste isolé au sommet du djebel el Bibane, surnommé “le Verdun marocain”. Il a sous ses ordres deux gradés européens et 25 tirailleurs.

Le 12 avril 1925, à l'approche d'une importante harka rifaine, les approvisionnements sont complétés et les défenses renforcées. Le 16, le poste est encerclé.

Le sergent Bernez-Cambot va alors être l'acteur d'une des plus belles pages de l'histoire des sous-officiers, face à des guerriers rifains déchaînés et de plus en plus nombreux. Le 3 mai, il fait savoir à son capitaine qu'il est blessé et que le moral de ses hommes est excellent.

Le 13 mai, alors que le siège dure depuis 27 jours, le général Colombat parvient enfin à forcer le passage et à ravitailler ce poste. Blessé de deux balles, le sergent refuse d'être évacué tout comme ses hommes. Le poste voisin de Dar Rémik ayant été replié sur celui de Bidane, la garnison se compose alors outre son chef, de deux sergents, 5 soldats européens et 48 tirailleurs. Le 25 mai, le poste est de nouveau encerclé. Les jours suivants les défenseurs de Bidane feront de nombreuses victimes parmi les Rifains.

Le 5 juin, au cinquante et unième jour de siège, les assauts sont de plus en plus nombreux. A 14 heures, Bernez-Cambot rend compte par message optique :

« poste fichu. Adieu ».

Ce n'est pourtant qu'à 16 heures que cesseront les bruits du combat, après l'assaut par près de deux mille Rifains. Lorsqu'en septembre suivant, les tirailleurs reprennent ce poste, les corps des héroïques défenseurs sont toujours à la même place. La croix de la Légion d'honneur à titre posthume sera décernée à ce sous-officier digne des plus pures traditions militaires. Un monument rappelle son souvenir dans son village natal de Livron dans le Béarn.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Placa y portada de la casa natal (calle Mayor, 46) del capellán castrense Don José María Campoy Irigoyen, asasinado vilmente tras capitulaciòn de la posición de Monte Arruit por las hordas de Abd el-Krim, cuyo nombre completo era Muhammad Ibn 'Abd el-Karim El-Jattabi.

El teniente Campoy asistia espiritualmente a los españoles (402 heridos) que se trasladaban de la posición señalada a Melilla.

Honor y Gloria para este héroe jaqués que descansa junto a sus compañeros del Regimiento de Caballeria Alcántara 14 en el Cementerio de la Inmaculada Concepción de la ciudad norteafricana

instagram

0 notes

Photo

22/07/1921. Tiene lugar el "Desastre de Annual", la extraordinaria derrota del ejército español en el protectorado de Marruecos, ante las tropas rifeñas de Abd-el-Krim, contabilizando unas bajas de más12.000 soldados españoles muertos. Los españoles, mal preparados, peor equipados y caoticamente dirigidos por el general Manuel Fernández Silvestre y su corte de ineptos, lameojetes y enchufados jefes y oficiales, condujeron a miles de soldados pobres (en aquel tiempo los ricos, pagando, se libraban de ir a la guerra) despreciando por completo la vida humana en una absurda estrategia que derivó includo en una investigacion gubernamental, que no ser por el golpe de estado de Primo de Rivera en septiembre de 1923, hubiera inculpado a toda la cúplua militar española, incluido el rey Alfonso XIII, pero tras el golpe, se dio carpetazo al tema y para callar bocas se condenó al general Berenguer, que fue amnistiado por el rey y más tarde nombrado Presidente del Consejo de Ministros. La España de siempre. https://www.instagram.com/p/CgT1tP0ohK_/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Anecdote historique inutile n°73 (oui je sais ça faisait longtemps mais il me faut de la matière les ami.e.s)

En 1925, André Breton désire faire reconnaître l'œuvre du poète Saint-Pol-Roux. Il l'invite donc à parler à une conférence, et l'écrivain, en retour, invite le jeune groupe de surréaliste à un banquet en son honneur, organisé par le Mercure de France à la Closerie des Lilas. Les surréalistes ne sont pas ravis de devoir se retrouver autour des anciens amis du poète, qui sont de vieilles biques littéraires symbolistes, réac et patriotiques. En particulier l'hôtesse Rachilde, qui vient de dire qu'une française ne pouvait épouser un allemand. Mais les surréalistes avaient prévu leur coup. Le jour même, un tract contre la guerre coloniale du Rif est publié dans l'humanité (Ce tract où il disent en substance que pour eux, la France n'existe pas, et qu'ils sont contre une guerre coloniale au Maroc). Ils vont donc joindre les actes aux mots. Ils crient "Vive l'Allemagne, à bas la France", Aragon traite Rachilde de femme à soldat et la malmène directement. Michel Leiris se met à la fenêtre du restaurant et s'époumone «À bas la France ! Vive Abd el-Krim !». C'est la bagarre générale! Les assiettes, les chandeliers, tout sert de projectile, et Soupault n'hésite pas à se distinguer en se suspendant à un lustre pour balayer tous les couverts de la table. Leiris est rossé par la foule attroupée devant le café, et ensuite retabassé par la police au cachot. Certains surréalistes ont failli mourir ce jour-là. Il faut dire, être contre la guerre coloniale, et soutenir publiquement le résistant Abdelkrim el-Khattabi était un acte super marginal dans la France de 1925. Mais ironie de l'histoire, Rachilde est aussi arrêtée comme fauteuse de trouble.

Je sais pas vous mais perso, j'aimerais trop voir ce genre de scène au cinéma! Ils ont quand même la classe les surréalistes.

1 note

·

View note