#7-30-1866

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

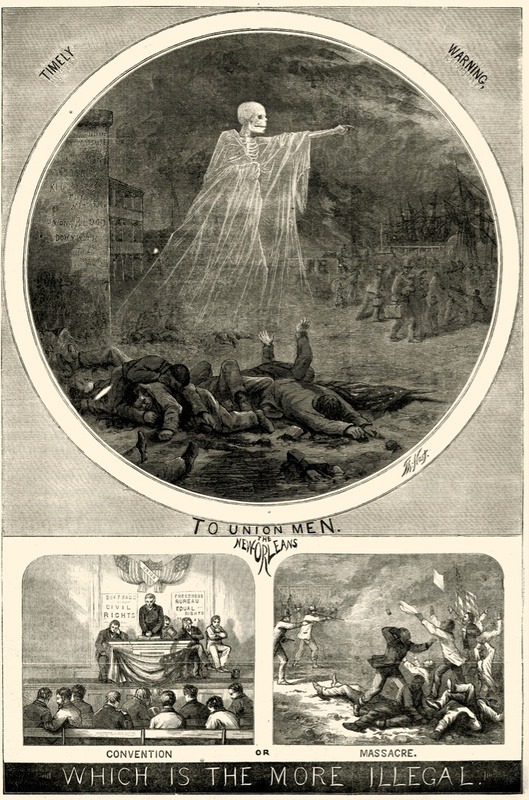

On July 30, 1866, black Republicans attempted to reconvene the Louisiana constitutional convention in an effort to secure voting rights. Held at the Mechanics’ Institute, a large crowd of black spectators was present as well. The gathering was attacked by an angry white mob that included police and firemen. [1] According to the Tribune, “black men were assassinated by scores. They fell inside of the hall, outside of the building, in the neighboring streets, and even in distant parts of the city, where they were tracked like dogs.” [2] Tribune editor Jean-Charles Houzeau witnessed the bloodbath and heard the assassins shout “To the Tribune!” He claimed the newspaper was saved by a detail of black soldiers. [3]

Louisiana was clearly incapable of reconstructing itself. The horror in New Orleans became an enormous national news story, tipping the fall congressional elections heavily in favor of Radical Republicans and significantly damaging President Johnson’s policies of accommodation with ex-Confederates. The new Republican controlled Congress wasted no time in passing four aggressive Reconstruction Acts. Louisiana was to be treated like a conquered enemy, and for the state to be readmitted to the Union, it had to create a new state constitution with strong equal rights provisions.

In late 1867 and early 1868, the constitutional convention in Louisiana drafted and enacted the most sweeping and radical state constitution in the American South. This historic body was composed of an almost equal number of black and white delegates. Many of the Tribune platforms were realized in the new charter, including black men’s right vote. The new state legislature included many black representatives. They would go on to enact the most far reaching and progressive legislation in the American South, including, unique to the entire south, an integrated public school system that was in place in New Orleans from 1872 to 1877. [4]

Harper’s Weekly devoted an entire issue to the massacre, including the grim full page graphic illustration “Timely Warning to Union Men. The New Orleans Convention or Massacre,” which appeared on September 8, 1866.

Official Website

This tour is based on Mark Charles Roudané’s most recent book “The New Orleans Tribune: An Introduction to America’s First Black Daily Newspaper.” To learn more about Roudané’s work, visit his official website and Facebook page.

Cite this Page

Mark Charles Roudané, “Mechanics' Institute Massacre,” New Orleans Historical, accessed July 31, 2024, https://neworleanshistorical.org/items/show/1541.

Related Sources

[1] James G. Hollandsworth Jr. An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2001).

[2] Tribune. July 30, 1867.

[3] Jean-Charles Houzeau. My Passage at the New Orleans Tribune: A Memoir of the Civil War Era, ed. David C. Rankin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984), 159.

See also: Mark Charles Roudané, The New Orleans Tribune, an Introduction to America’s First Black Daily Newspaper (Saint Paul: Roudanez History and Legacy, 2018).

#Mechanics’ Institute Massacre#7-31-1866#New Orleans#Louisiana#Black Voting Rights#Black Freedmen#white confederates#civil war#7-30-1866#american hate#white supremacy

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Great Sioux War

The Great Sioux War (also given as the Black Hills War, 1876-1877) was a military conflict between the allied forces of the Lakota Sioux/Northern Cheyenne and the US government over the territory of the Black Hills and, more widely, US policies of westward expansion and the appropriation of Native American lands.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 had established the Great Sioux Reservation, including the Black Hills, and promised this land to the Sioux in perpetuity. When gold was discovered in the Black Hills in 1874, the treaty was ignored by the US government, leading to the Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876. The Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho responded with armed resistance in raids on wagon trains, skirmishes, and five major battles fought between March 1876 and January 1877:

Battle of Powder River (Reynolds Battle) – 17 March 1876

Battle of the Rosebud (Battle Where the Girl Saved Her Brother) – 17 June 1876

Battle of the Little Bighorn (Battle of the Greasy Grass) – 25-26 June 1876

Battle of Slim Buttes – 9-10 September 1876

Battle of Wolf Mountain (Battle of Belly Butte) – 8 January 1877

In between these, were so-called minor engagements with casualties on both sides but, after June 1876, greater losses for the Sioux and Cheyenne. The final armed conflict of the Great Sioux War was the Battle of Muddy Creek (the Lame Deer Fight, 7-8 May 1877), by which time the Sioux war chief Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877) had already surrendered and the chief Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890) and Sioux war chief Gall (l.c. 1840-1894) and others had fled to the region of modern-day Canada. Although the war was over by May 1877, ending in a victory for the US military, some bands of Sioux and Cheyenne continued to struggle against reservation life until the Wounded Knee Massacre of 29 December 1890 broke their resistance.

Background

Although the first armed conflict between the Plains Indians and Euro-Americans was in 1823, problems between the Sioux and the US military began on 19 August 1854 with the Grattan Fight (Grattan Massacre), when 2nd Lieutenant John L. Grattan led his command of 30 soldiers to the camp of Chief Conquering Bear (l. c. 1800-1854) to demand the surrender of a man they claimed had stolen a cow from a Mormon wagon train.

Conquering Bear refused to surrender anyone, offering compensation instead, and, as the negotiations broke down, Grattan's men fired on the Sioux, mortally wounding Conquering Bear, and the Sioux warriors retaliated, killing Grattan and all of his command. The US military responded with campaigns against the Sioux in the First Sioux War of 1854-1856, which also included actions against their allies, the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

Tensions escalated after the opening of the Bozeman Trail in 1863, the establishment of forts to protect white settlers using the trail, and the Sand Creek Massacre of 29 November 1864. Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) was launched in response to the construction of these forts and the policies of the US government, concluding with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which established the Great Sioux Reservation (modern-day South Dakota and parts of North Dakota and Nebraska), including the Black Hills – a site sacred to the Sioux – which was promised to them for "as long as the grass should grow and the rivers flow."

When Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876) discovered gold in the Black Hills in 1874, the Fort Laramie treaty was broken as over 15,000 white settlers and miners streamed into the region during the Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876. The US government offered to purchase the Black Hills, but the Sioux would not sell. More settlers arrived, the government ignored Sioux demands that the 1868 treaty be honored, and the Great Sioux War began in March of that year, with the Reynolds campaign on the Powder River.

Continue reading...

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Mode illustrée, no. 41, 7 octobre 1866, Paris. Confections des Magasins du Louvre. 164. rue de Rivoli. Ville de Paris / Bibliothèque Forney

Étoffes, paletots et jupons des magasins du Louvre.

Jupon en cachemire rouge (ou plutôt bande de cachemire rouge, ayant 30 centimètres de largeur, tuyautée sur toute sa hauteur); robe en taffetas noir, à fines rayures rouges, à bords dentelé, un peu plus courte que le jupon. Paletot en cachemire noir, orné de galons perlés, à bords dentelés, garnis d'un effilé terminé par des perles. Chapeau de tulle noir, avec brides-écharpes.

Red cashmere petticoat (or rather a strip of red cashmere, 30 centimeters wide, piped over its entire height); black taffeta dress, with fine red stripes, with serrated edges, a little shorter than the petticoat. Black cashmere overcoat, decorated with pearl braid, with serrated edges, trimmed with a tapered edge finished with pearls. Black tulle hat, with scarf straps.

—

Robe en poult-de-soie gris, bord��e avec un volant tuyauté, ayant 10 centimètres de largeur; chaque lé est bordé avec une bande de velours violet, ayant 4 centimètres de largeur, surmontée d'une bande pareille, ayant 1 centimètre de largeur; ces bandes remontent sur toutes les coutures, de telle sorte que chaque lé est encadré, et semble boutonné sur le lé voisin, avec trois gros boutons de velours violet posés sur le bord inférieur, tout près des bandes. Le lé de devant semble boutonné de chaque côté sur les lés qui se joignent. Paletot en drap-velours violet, bordé d'astracan; manchon d'astracan. Chapeau en satin blanc.

Dress in gray poult-de-silk, edged with a piped flounce, 10 centimeters wide; each strip is edged with a strip of purple velvet, 4 centimeters wide, surmounted by a similar strip, 1 centimeter wide; these strips go up on all the seams, so that each strip is framed, and seems buttoned on the neighboring strip, with three large purple velvet buttons placed on the lower edge, very close to the strips. The front strip seems buttoned on each side on the strips which join. Overcoat in purple velvet cloth, edged with astracan; muff of astracan. Hat in white satin.

#La Mode illustrée#19th century#1860s#1866#on this day#October 7#periodical#fashion#fashion plate#color#description#bibliothèque nationale de france#dress#jacket#coat#Modèles de chez#Magasins du Louvre

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

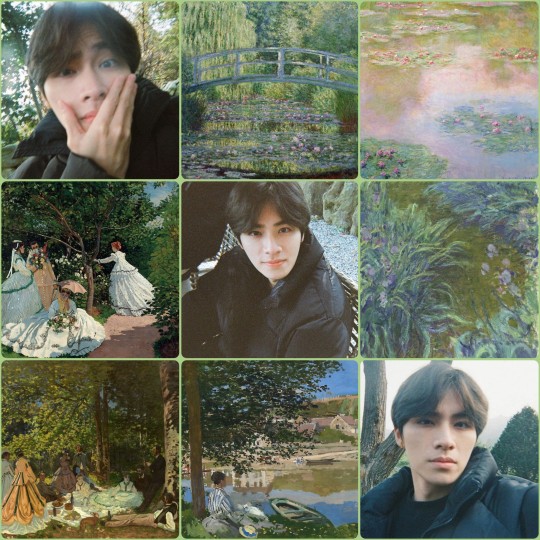

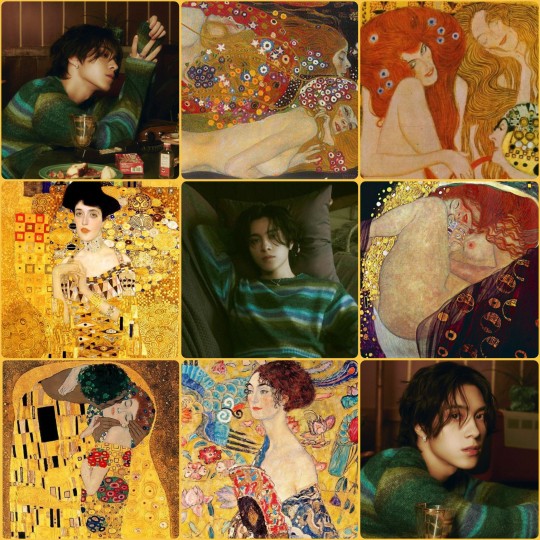

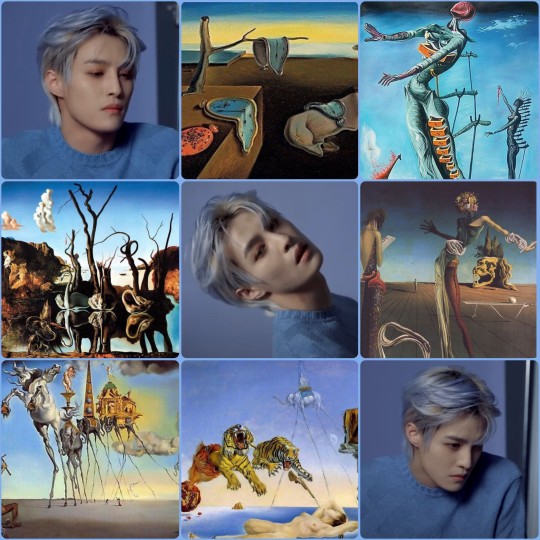

Which artist I think wayv members would be drawn by:

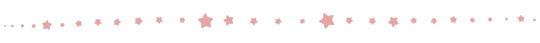

♡𝐊𝐮𝐧 could be drawn by 𝐕𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐕𝐚𝐧 𝐆𝐨𝐠𝐡♡

❥Vase with the twelve sunflowers, 1888

❥Self portrait, 1887

❥People strolling in a park in Paris, 1886

❥Wheat field with Cypresses, 1889

❥ Self-portrait with grey felt hat, 1887

❥Meadow in the mountains: Le Mas de Saint-Paul, 1889

♡𝐓𝐞𝐧 could be drawn by 𝐘𝐢𝐳𝐡𝐞𝐧𝐠 𝐊𝐞♡

❥7-30

❥7-26

❥7-4

❥Pink+!

❥0_0

❥6-27 6-28

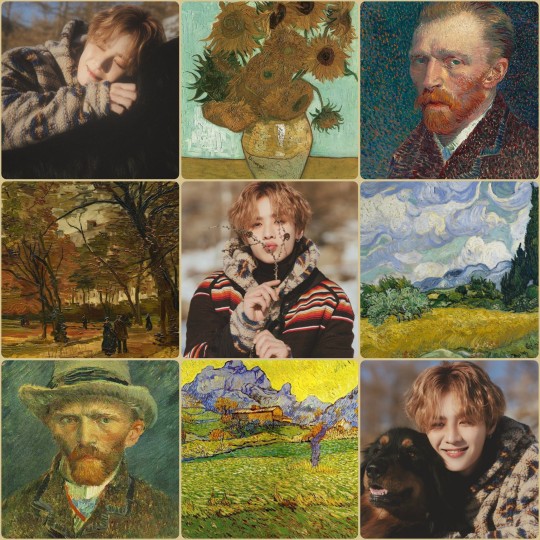

♡𝐖𝐢𝐧 𝐰𝐢𝐧 could be drawn by 𝐏𝐢𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐞-𝐀𝐮𝐠𝐮𝐬𝐭𝐞 𝐑𝐞𝐧𝐨𝐢𝐫♡

❥Woman with a parasol in a garden, 1875

❥The skiff, 1875

❥La Promenade, 1870

❥The swing, 1876

❥Path through the woods, 1874

❥La Grenouillere, 1869

♡𝐗𝐢𝐚𝐨𝐣𝐮𝐧 could be drawn by 𝐂𝐥𝐚𝐮𝐝𝐞 𝐌𝐨𝐧𝐞𝐭♡

❥The water lily pond, 1899

❥Water lilies, 1919

❥Women in the garden, 1866

❥Irises, 1914

❥Luncheon on the grass, 1865-66

❥On the bank of the Sienne, Bennecourt, 1868

♡𝐇𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐲 could be drawn by 𝐆𝐮𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐯 𝐊𝐥𝐢𝐦𝐭♡

❥Water serpents ii, 1907

❥Beethoven frieze, 1902

❥Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer i, 1903-07

❥Danae, 1908

❥The kiss, 1908

❥Lady with a fan, 1918

♡𝐘𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐲𝐚𝐧𝐠 could be drawn by 𝐒𝐚𝐥𝐯𝐚𝐝𝐨𝐫 𝐃𝐚𝐥𝐢♡

❥The persistence of memory, 1931

❥The Burning Giraffe, 1937

❥Swans reflecting elephants, 1937

❥Woman with a head of roses, 1935

❥The temptation of St. Anthony, 1946

❥Dream caused by the flight of a bee around a pomegranate a second before awakening, 1944

#nctzen#wayv#wayv icons#wayv moodboard#wayv ten#ten#yangyang#liu yangyang#ten lee#qian kun#kun#wayv kun#wayv yangyang#wayv winwin#wayv sicheng#dong sicheng#nct sicheng#winwin#ten chittaphon#chittaphon leechaiyapornkul#hendery#wayv hendery#xiaojun#wayv xiaojun#xiao dejun#paintings#gustav klimt#salvador dali#pierre auguste renoir#vincent van gogh

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traintober 2023 is Here!

Now, I can't draw - and I'm a writer anyway, so here's 31 days worth of headcanons, rambles and short stories based on the Traintober prompts by @theflyingkipper. First time doing this, so it ought to be fun!

This is the master post, so it'll have all the links you need to find what I post this year. This page will also have this link to my Ao3 work which has the same stuff, but without pictures.

Day 1: Free Day (A ramble about preservation and Sodor) Day 2: Bridge (Rheneas, 1866) Day 3: Twins (Neil, Bill and Ben) Day 4: Devious (Diesel will forever be the most devious) Day 5: It's Only Me! (Sir Topham Hatt and Edward, a friendship in three words...) Day 6: Special Letters (A Tale of Two A1 Brothers...) Day 7: Refreshment (The Refreshment Lady is retiring...) Day 8: Bird (Cranky blames Henry for it all...) Day 9: Viaduct (Neil doesn't like the Viaduct...) Day 10: Happiest (The Engines are Happiest when...) Day 11: Roundhouse (Edward doesn't like Tidmouth Sheds...) Day 12: Something Borrowed (Maybe don't Borrow Henrietta...) Day 13: Something New (Gordon's new life on the slow trains...) Day 14: Young Iron (Ivo Hugh has some advice for a young engine...) Day 15: Maintenance (Duke Needs the Others to be Well Maintained...) Day 16: Purpose (What is an engine's purpose?) Day 17: Holiday (How Tourism on Sodor has evolved...) Day 18: Blueprints (Crovan's Gate is home to many blueprints...) Day 19: Revolutionary (What are the origins of the iconic phrase?...) Day 20: Live Wire (Edward didn't much like the telegraph wires...) Day 21: Roots (Terence does not like weeds...) Day 22: Top Hat (Sir Topham Hatt I decides to visit the railway...) Day 23: Big World (Duck manages to squirm into the BWBA movie...) Day 24: Odd Jobs (Rusty has many odd jobs...) Day 25: Distress Signal (What's out in Tidmouth Bay...) Day 26: Summit (James and the Culdee Fell Engine...) Day 27: Record-Breaker (Mallard broke the record; the record broke Mallard) Day 28: Which Way Now (An engine gets lost in the fog...) Day 29: Out of Service (Oliver wasn't the only engine in that siding...) Day 30: Middle of Nowhere (They should have left that part of the island alone) Day 31: Lights Out (Don't let the lights go out at Crovan's Gate)

#fanfiction writer#railway series#weirdowithaquill#thomas the tank engine#railways#traintober#traintober 2023#ttte#masterlist#ao3 link

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The napoleonic marshal‘s children

After seeing @josefavomjaaga’s and @northernmariette’s marshal calendar, I wanted to do a similar thing for all the marshal’s children! So I did! I hope you like it. c: I listed them in more or less chronological order but categorised them in years (especially because we don‘t know all their birthdays). At the end of this post you are going to find remarks about some of the marshals because not every child is listed! ^^“ To the question about the sources: I mostly googled it and searched their dates in Wikipedia, ahaha. Nevertheless, I also found this website. However, I would be careful with it. We are talking about history and different sources can have different dates. I am always open for corrections. Just correct me in the comments if you find or know a trustful source which would show that one or some of the dates are incorrect. At the end of the day it is harmless fun and research. :) Pre 1790

François Étienne Kellermann (4 August 1770- 2 June 1835)

Marguerite Cécile Kellermann (15 March 1773 - 12 August 1850)

Ernestine Grouchy (1787–1866)

Mélanie Marie Josèphe de Pérignon (1788 - 1858)

Alphonse Grouchy (1789–1864)

Jean-Baptiste Sophie Pierre de Pérignon (1789- 14 January 1807)

Marie Françoise Germaine de Pérignon (1789 - 15 May 1844)

Angélique Catherine Jourdan (1789 or 1791 - 7 March 1879)

1790 - 1791

Marie-Louise Oudinot (1790–1832)

Marie-Anne Masséna (8 July 1790 - 1794)

Charles Oudinot (1791 - 1863)

Aimee-Clementine Grouchy (1791–1826)

Anne-Francoise Moncey (1791–1842)

1792 - 1793

Bon-Louis Moncey (1792–1817)

Victorine Perrin (1792–1822)

Anne-Charlotte Macdonald (1792–1870)

François Henri de Pérignon (23 February 1793 - 19 October 1841)

Jacques Prosper Masséna (25 June 1793 - 13 May 1821)

1794 - 1795

Victoire Thècle Masséna (28 September 1794 - 18 March 1857)

Adele-Elisabeth Macdonald (1794–1822)

Marguerite-Félécité Desprez (1795-1854); adopted by Sérurier

Nicolette Oudinot (1795–1865)

Charles Perrin (1795–15 March 1827)

1796 - 1997

Emilie Oudinot (1796–1805)

Victor Grouchy (1796–1864)

Napoleon-Victor Perrin (24 October 1796 - 2 December 1853)

Jeanne Madeleine Delphine Jourdan (1797-1839)

1799

François Victor Masséna (2 April 1799 - 16 April 1863)

Joseph François Oscar Bernadotte (4 July 1799 – 8 July 1859)

Auguste Oudinot (1799–1835)

Caroline de Pérignon (1799-1819)

Eugene Perrin (1799–1852)

1800

Nina Jourdan (1800-1833)

Caroline Mortier de Trevise (1800–1842)

1801

Achille Charles Louis Napoléon Murat (21 January 1801 - 15 April 1847)

Louis Napoléon Lannes (30 July 1801 – 19 July 1874)

Elise Oudinot (1801–1882)

1802

Marie Letizia Joséphine Annonciade Murat (26 April 1802 - 12 March 1859)

Alfred-Jean Lannes (11 July 1802 – 20 June 1861)

Napoléon Bessière (2 August 1802 - 21 July 1856)

Paul Davout (1802–1803)

Napoléon Soult (1802–1857)

1803

Marie-Agnès Irma de Pérignon (5 April 1803 - 16 December 1849)

Joseph Napoléon Ney (8 May 1803 – 25 July 1857)

Lucien Charles Joseph Napoléon Murat (16 May 1803 - 10 April 1878)

Jean-Ernest Lannes (20 July 1803 – 24 November 1882)

Alexandrine-Aimee Macdonald (1803–1869)

Sophie Malvina Joséphine Mortier de Trévise ( 1803 - ???)

1804

Napoléon Mortier de Trévise (6 August 1804 - 29 December 1869)

Michel Louis Félix Ney (24 August 1804 – 14 July 1854)

Gustave-Olivier Lannes (4 December 1804 – 25 August 1875)

Joséphine Davout (1804–1805)

Hortense Soult (1804–1862)

Octavie de Pérignon (1804-1847)

1805

Louise Julie Caroline Murat (21 March 1805 - 1 December 1889)

Antoinette Joséphine Davout (1805 – 19 August 1821)

Stephanie-Josephine Perrin (1805–1832)

1806

Josephine-Louise Lannes (4 March 1806 – 8 November 1889)

Eugène Michel Ney (12 July 1806 – 25 October 1845)

Edouard Moriter de Trévise (1806–1815)

Léopold de Pérignon (1806-1862)

1807

Adèle Napoleone Davout (June 1807 – 21 January 1885)

Jeanne-Francoise Moncey (1807–1853)

1808: Stephanie Oudinot (1808-1893) 1809: Napoleon Davout (1809–1810)

1810: Napoleon Alexander Berthier (11 September 1810 – 10 February 1887)

1811

Napoleon Louis Davout (6 January 1811 - 13 June 1853)

Louise-Honorine Suchet (1811 – 1885)

Louise Mortier de Trévise (1811–1831)

1812

Edgar Napoléon Henry Ney (12 April 1812 – 4 October 1882)

Caroline-Joséphine Berthier (22 August 1812 – 1905)

Jules Davout (December 1812 - 1813)

1813: Louis-Napoleon Suchet (23 May 1813- 22 July 1867/77)

1814: Eve-Stéphanie Mortier de Trévise (1814–1831) 1815

Marie Anne Berthier (February 1815 - 23 July 1878)

Adelaide Louise Davout (8 July 1815 – 6 October 1892)

Laurent François or Laurent-Camille Saint-Cyr (I found two almost similar names with the same date so) (30 December 1815 – 30 January 1904)

1816: Louise Marie Oudinot (1816 - 1909)

1817

Caroline Oudinot (1817–1896)

Caroline Soult (1817–1817)

1819: Charles-Joseph Oudinot (1819–1858)

1820: Anne-Marie Suchet (1820 - 27 May 1835) 1822: Henri Oudinot ( 3 February 1822 – 29 July 1891) 1824: Louis Marie Macdonald (11 November 1824 - 6 April 1881.) 1830: Noemie Grouchy (1830–1843) —————— Children without clear birthdays:

Camille Jourdan (died in 1842)

Sophie Jourdan (died in 1820)

Additional remarks: - Marshal Berthier died 8.5 months before his last daughter‘s birth. - Marshal Oudinot had 11 children and the age difference between his first and last child is around 32 years. - The age difference between marshal Grouchy‘s first and last child is around 43 years. - Marshal Lefebvre had fourteen children (12 sons, 2 daughters) but I couldn‘t find anything kind of reliable about them so they are not listed above. I am aware that two sons of him were listed in the link above. Nevertheless, I was uncertain to name them in my list because I thought that his last living son died in the Russian campaign while the website writes about the possibility of another son dying in 1817. - Marshal Augerau had no children. - Marshal Brune had apparently adopted two daughters whose names are unknown. - Marshal Pérignon: I couldn‘t find anything about his daughters, Justine, Elisabeth and Adèle, except that they died in infancy. - Marshal Sérurier had no biological children but adopted Marguerite-Félécité Desprez in 1814. - Marshal Marmont had no children. - I found out that marshal Saint-Cyr married his first cousin, lol. - I didn‘t find anything about marshal Poniatowski having children. Apparently, he wasn‘t married either (thank you, @northernmariette for the correction of this fact! c:)

#Marshal‘s children calendar#literally every napoleonic marshal ahaha#napoleonic era#Napoleonic children#I am not putting all the children‘s names into the tags#Thank you no thank you! :)#YES I posted it without double checking every child so don‘t be surprised when I have to correct some stuff 😭#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

July 25, 2024. Last week I was going on about how I wish field trips were a more regular thing in adulthood. Lo and behold, this week I went to Arles with three museum friends and can assure you, the whole field trip idea is even better when it's outside the work context.

We went specifically to see the exhibition Van Gogh and the Stars at the Fondation Van Gogh. The star (ha) painting was Van Gogh's Starry Night Over the Rhone, a loan from the Musée d'Orsay as part of the 150th anniversary of impressionism, an event being marked all over France, not just in Normandy. The painting's presence in this exhibition is special because this is the first time it's being shown since its creation in Arles 136 years ago!

The exhibition is (surprisingly) large but there are only two paintings and one drawing by Van Gogh himself, all the other works are by other artists on the theme of the stars and all the subcategories you can probably think of. So the name of the expo is kind of clickbaity but overall, it's still an impressive exhibition.

Here's a very small selection of works visible at the expo:

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), La nuit étoilée sur le Rhône, 1888, oil on canvas, Paris, Musée d'Orsay.

?

Camille Corot (1796-1875), L'étoile du Berger, 1864, oil on canvas, Toulouse, Musée des Augustins.

Kasimir Malevitch (1879-1935), Construction cosmique magnétique, 1916, oil on canvas, Private collection.

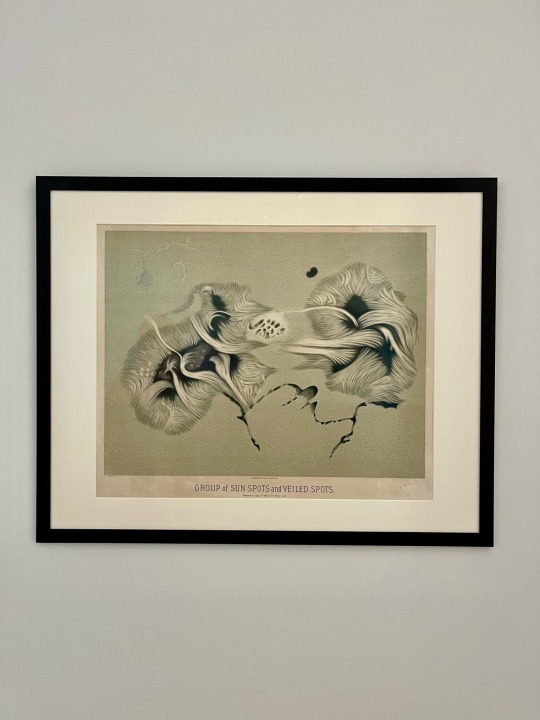

Étienne Léopold Trouvelot (1827-1895), Group of Sun Spots and Veiled Spots, Observed on June 17th 1875 at 7 h. 30 m. A.M., 1881, print, New York, New York Public Library.

Augusto Giacometti (1877-1947), Ciel étoilé (Voie lactée), 1917, oil on canvas, Chur, Bündner Kunstmuseum.

Frédéric-Auguste Cazals (1865-1941), Jean Moréas rallumant son cigare aux étoiles, 1893, gouache on paper, Private collection.

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), Veillée (d'après Millet), 1889, oil on canvas, Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum.

Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), Bleu, 1927, oil on board, New York, Museum of Modern Art.

#phd life#studyblr#art history#arles#day in the life#south of france#museums#100 days of productivity#spilled thoughts#field trip#travelblr#vincent van gogh#museum work

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

irl bsd authors

i haven't found a list of irl bsd authors listed from oldest to most recent so i decided to do that. multiple lists for date of birth, death, and publication of the work their ability is based on (if applicable) + fun stuff at the end

birth dates (oldest to most recent)

alexander pushkin - 6 Jun 1799

nathaniel hawthorne - 4 Jul 1804

edgar allan poe - 19 Jan 1809

nikolai gogol - 1 Apr 1809

ivan gonchorav - 18 Jun 1812

herman melville - 1 Aug 1819

fyodor dostoevsky - 11 Nov 1821

jules verne - 8 Feb 1828

saigiku jōno - 24 Sep 1832

louisa may alcott - 29 Nov 1832

yukichi fukuzawa - 10 Jan 1835

mark twain - 30 Nov 1835

ōchi fukuchi - 13 May 1841

paul verlaine - 30 Mar 1844

bram stoker - 8 Nov 1847

tetchō suehiro - 15 Mar 1849

arthur rimbaud - 20 Oct 1854

ryūrō hirotsu - 15 Jul 1861

ōgai mori - 17 Feb 1862

h. g. wells - 21 Sep 1866

natsume sōseki - 9 Feb 1867

kōyō ozaki - 10 Jan 1868

andré gide - 22 Nov 1869

doppo kunikida - 30 Aug 1871

katai tayama - 22 Jan 1872

ichiyō higuchi - 2 May 1872

kyōka izumi - 4 Nov 1873

lucy maud montgomery - 30 Nov 1874

akiko yosano - 7 Dec 1878

santōka taneda - 3 Dec 1882

teruko ōkura - 12 Apr 1886

jun'ichirō tanizaki - 24 Jul 1886

yumeno kyūsaku - 4 Jan 1889

h. p. lovecraft - 20 Aug 1890

agatha christie - 15 Sep 1890

ryūnosuke akutagawa - 1 Mar 1892

ranpo edogawa - 21 Oct 1894

kenji miyazawa - 27 Aug 1896

f. scott fitzgerald - 24 Sep 1896

margaret mitchell - 8 Nov 1900

motojirō kajii - 17 Feb 1901

mushitarō oguri - 14 Mar 1901

john steinbeck - 27 Feb 1902

aya kōda - 1 Sep 1904

ango sakaguchi - 20 Oct 1906

chūya nakahara - 29 Apr 1907

atsushi nakajima - 5 May 1909

osamu dazai - 19 Jun 1909

sakunosuke oda - 26 Oct 1913

michizō tachihara - 30 Jul 1914

tatsuhiko shibusawa - 8 May 1928

(ace) alan bennett - 9 May 1934

yukito ayatsuji - 23 Dec 1960

mizuki tsujimura - 29 Feb 1980

death dates (oldest to most recent)

alexander pushkin - 10 Feb 1837

edgar allan poe - 7 Oct 1849

nikolai gogol - 4 Mar 1852

nathaniel hawthorne - 19 May 1864

fyodor dostoevsky - 9 Feb 1881

louisa may alcott - 6 Mar 1888

ivan goncharov - 27 Sep 1891

herman melville - 28 Sep 1891

arthur rimbaud - 10 Nov 1891

paul verlaine - 8 Jan 1896

tetchō suehiro - 5 Feb 1896

ichiyō higuchi - 23 Nov 1896

yukichi fukuzawa - 3 Feb 1901

saigiku jōno - 24 Jan 1904

jules verne - 24 Mar 1905

kōyō ozaki - 30 Oct 1903

ōchi fukuchi - 4 Jan 1906

doppo kunikida - 23 Jun 1908

mark twain - 21 Apr 1910

bram stoker - 20 Apr 1912

natsume sōseki - 9 Dec 1916

ōgai mori - 8 Jul 1922

ryūrō hirotsu - 25 Oct 1928

ryūnosuke akutagawa - 24 Jul 1927

katai tayama - 13 May 1930

motojirō kajii - 24 Mar 1932

kenji miyazawa - 21 Sep 1933

yumeno kyūsaku - 11 Mar 1936

h. p. lovecraft - 15 Mar 1937

chūya nakahara - 22 Oct 1937

michizō tachihara - 29 Mar 1939

kyōka izumi - 7 Sep 1939

santōka taneda - 11 Oct 1940

f. scott fitzgerald - 21 Dec 1940

lucy maud montgomery - 24 Apr 1942

mushitarō oguri - 10 Feb 1946

h. g. wells - 13 Aug 1946

akiko yosano - 29 May 1942

atsushi nakajima - 4 Dec 1942

sakunosuke oda - 10 Jan 1947

osamu dazai - 13 Jun 1948

margaret mitchell - 16 Aug 1949

andré gide - 19 Feb 1951

ango sakaguchi - 17 Feb 1955

teruko ōkura - 18 Jul 1960

ranpo edogawa - 28 Jul 1965

jun'ichirō tanizaki - 30 Jul 1965

john steinbeck - 20 Dec 1968

agatha christie - 12 Jan 1976

tatsuhiko shibusawa - 5 Aug 1987

aya kōda - 31 Oct 1990

(ace) allan bennett - still alive

yukito ayatsuji - still alive

mizuki tsujimura - still alive

work (oldest to most recent)

alexander pushkin - A Feast in Time of Plague, 1830

edgar allan poe - The Murders in Rue Morgue, 1841

nikolai gogol - The Overcoat, 1842

edgar allan poe - The Black Cat, 19 Aug 1843

nathaniel hawthorne - The Scarlet Letter, 1850

herman melville - Moby-Dick, 1851

louisa may alcott - Little Women, 1858

fyodor dostoevsky - Crime and Punishment, 1866

ivan goncharov - The Precipice, 1869

yukichi fukuzawa - An Encouragement of Learning, 1872-76

jules verne - The Mysterious Island, 1875

mark twain - The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, 1876

mark twain - Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, 1884

tetchō suehiro - Plum Blossoms in the Snow, 1886

arthur rimbaud - Illuminations, 1886

saigiku jōno - Priceless Tears, 1889

ōchi fukuchi - The Mirror Lion, A Spring Diversion, Mar 1893

ryūrō hirotsu - Falling Camellia, 1894

h. g. wells - The Time Machine, 1895

kōyō ozaki - The Golden Demon, 1897

bram stoker - Dracula, 1897 (his ability has not been named, but c’mon, vampires)

akiko yosano - Thou Shall Not Die, 1903

natsume sōseki - I Am a Cat, 1905-06

katai tayama - Futon, 1907

lucy maud montgomery - Anne of Green Gables, 1908

ōgai mori - Vita Sexualis, 1909

andré gide - Strait is the Gate, 1909

kyōka izumi - Demon Pond, 1913

ryūnosuke akutagawa - Rashomon, 1915

motojirō kajii - Lemon, 1924

f. scott fitzgerald - The Great Gatsby, 1925

kenji miyazawa - Be not Defeated by the Rain, 3 Nov 1931

santōka taneda - Self-Derision, 8 Jan 1932

mushitarō oguri - Perfect Crime, 1933

chūya nakahara - This Tainted Sorrow, 1934

yumeno kyūsaku - Dogra Magra, 1935

margaret mitchell - Gone With the Wind, 1936

john steinbeck - The Grapes of Wrath, 1939

agatha christie - And Then There Were None, 6 Nov 1939

atsushi nakajima - The Moon Over the Mountain, Feb 1942

jun'ichirō tanizaki - The Makioka Sisters, 1943-48

ango sakaguchi - Discourse on Decadence, 1946

teruko ōkura - Gasp of the Soul, 1947

osamu dazai - No Longer Human, 1948

(ace) alan bennett - The Madness of King George III, 1995

yukito ayatsuji - Another, 2005

mizuki tsujimura - Yesterday’s Shadow Tag, 2015

can’t find dates:

michizō tachihara - Midwinter Memento

sakunosuke oda - Flawless

n/a: doppo kunikida, ranpo edogawa, ichiyō higuchi, h. p. lovecraft “Great Old Ones” (fictional ancient dieties eg. cthulhu), aya koda, paul verlaine, tatsuhiko shibusawa “Draconia” (umbrella term for shibusawa’s works/style)

bonus:

elise - The Dancing Girl (1890) by ōgai mori

shōsaku katsura - An Uncommon Common Man by doppo kunikida

Nobuko Sasaki (20 Jul 1878 - 22 Sep 1949) - doppo kunikida’s first wife

gin akutagawa - O-gin (1922) by ryūnosuke akutagawa

naomi tanizaki + kirako haruno - Naomi (1925) by jun'ichirō tanizaki

t. j. eckelburg + tom buchanan - The Great Gatsby (1925) by f. scott fitzgerald

the black lizard - Back Lizard (1895) by ryūrō hirotsu (+ The Black Lizard (1934) by ranpo edogawa)

some fun facts:

the oldest: aya koda 86, andré gide 81, h. g. wells 79, jun'ichirō tanizaki 79, ivan goncharov 79 (alan bennett is 89 but still alive)

the youngest: ichiyō higuchi 24, michizō tachihara 24, chūya nakahara 30

yukito ayatsuji’s Another is also an anime, released in 2012

both edgar allan poe and mark twain’s ability consist of two of the author’s work

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone wrote this as a factual historically backed response to the claim that somehow Democrats and Republicans changed sides.

June 17, 1854

The Republican Party is officially founded as an abolitionist party to slavery in the United States.

October 13, 1858

During the Lincoln-Douglas debates, U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas (D-IL) said, “If you desire negro citizenship, if you desire to allow them to come into the State and settle with the white man, if you desire them to vote on an equality with yourselves, and to make them eligible to office, to serve on juries, and to adjudge your rights, then support Mr. Lincoln and the Black Republican party, who are in favor of the citizenship of the negro. For one, I am opposed to negro citizenship in any and every form. I believe this Government was made on the white basis. I believe it was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity for ever, and I am in favor of confining citizenship to white men, men of European birth and descent, instead of conferring it upon negroes, Indians, and other inferior races.”. Douglas became the Democrat Party’s 1860 presidential nominee.

April 16, 1862

President Lincoln signed the bill abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. In Congress, almost every Republican voted for yes and most Democrats voted no.

July 17, 1862

Over unanimous Democrat opposition, the Republican Congress passed The Confiscation Act stating that slaves of the Confederacy “shall be forever free”.

April 8, 1864

The 13th Amendment banning slavery passed the U.S. Senate with 100% Republican support, 63% Democrat opposition.

January 31, 1865

The 13th Amendment banning slavery passed the U.S. House with unanimous Republican support and intense Democrat opposition.November 22, 1865

Republicans denounced the Democrat legislature of Mississippi for enacting the “black codes” which institutionalized racial discrimination.

February 5, 1866

U.S. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens (R-PA) introduced legislation (successfully opposed by Democrat President Andrew Johnson) to implement “40 acres and a mule” relief by distributing land to former slaves.

March 27, 1866

Democrat President Andrew Johnson vetoes of law granting voting rights to blacks.

May 10, 1866

The U.S. House passed the Republicans’ 14th Amendment guaranteeing due process and equal protection of the laws to all citizens. 100% of Democrats vote no.

June 8, 1866

The U.S. Senate passed the Republicans’ 14th Amendment guaranteeing due process and equal protection of the law to all citizens. 94% of Republicans vote yes and 100% of Democrats vote no.

March 27, 1866

Democrat President Andrew Johnson vetoes of law granting voting rights to blacks in the District of Columbia.

July 16, 1866

The Republican Congress overrode Democrat President Andrew Johnson’s veto of legislation protecting the voting rights of blacks.

March 30, 1868

Republicans begin the impeachment trial of Democrat President Andrew Johnson who declared, “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government of white men.”September 12, 1868

Civil rights activist Tunis Campbell and 24 other blacks in the Georgia Senate (all Republicans) were expelled by the Democrat majority and would later be reinstated by the Republican Congress.

October 7, 1868

Republicans denounced Democrat Party’s national campaign theme: “This is a white man’s country: Let white men rule.”

October 22, 1868

While campaigning for re-election, Republican U.S. Rep. James Hinds (R-AR) was assassinated by Democrat terrorists who organized as the Ku Klux Klan. Hinds was the first sitting congressman to be murdered while in office.

December 10, 1869

Republican Gov. John Campbell of the Wyoming Territory signed the FIRST-in-nation law granting women the right to vote and hold public office.

February 3, 1870

After passing the House with 98% Republican support and 97% Democrat opposition, Republicans’ 15th Amendment was ratified, granting the vote to ALL Americans regardless of race.

February 25, 1870

Hiram Rhodes Revels (R-MS) becomes the first black to be seated in the United States Senate.

May 31, 1870

President U.S. Grant signed the Republicans’ Enforcement Act providing stiff penalties for depriving any American’s civil rights.

June 22, 1870

Ohio Rep. Williams Lawrence created the U.S. Department of Justice to safeguard the civil rights of blacks against Democrats in the South.

September 6, 1870

Women voted in Wyoming in first election after women’s suffrage signed into law by Republican Gov. John Campbell.

February 1, 1871

Rep. Jefferson Franklin Long (R-GA) became the first black to speak on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

February 28, 1871

The Republican Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1871 providing federal protection for black voters.

April 20, 1871

The Republican Congress enacted the Ku Klux Klan Act, outlawing Democrat Party-affiliated terrorist groups which oppressed blacks and all those who supported them.

October 10, 1871

Following warnings by Philadelphia Democrats against black voting, Republican civil rights activist Octavius Catto was murdered by a Democrat Party operative. His military funeral was attended by thousands.

October 18, 1871

After violence against Republicans in South Carolina, President Ulysses Grant deployed U.S. troops to combat Democrat Ku Klux Klan terrorists.

November 18, 1872

Susan B. Anthony was arrested for voting after boasting to Elizabeth Cady Stanton that she voted for “Well, I have gone and done it — positively voted the straight Republican ticket.”January 17, 1874

Armed Democrats seized the Texas state government, ending Republican efforts to racially integrate.

September 14, 1874

Democrat white supremacists seized the Louisiana statehouse in attempt to overthrow the racially-integrated administration of Republican Governor William Kellogg. Twenty-seven were killed.

March 1, 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, guaranteeing access to public accommodations without regard to race, was signed by Republican President U.S. Grant and passed with 92% Republican support over 100% Democrat opposition.

January 10, 1878

U.S. Senator Aaron Sargent (R-CA) introduced the Susan B. Anthony amendment for women’s suffrage. The Democrat-controlled Senate defeated it four times before the election of a Republican House and Senate that guaranteed its approval in 1919.

February 8, 1894

The Democrat Congress and Democrat President Grover Cleveland joined to repeal the Republicans’ Enforcement Act which had enabled blacks to vote.

January 15, 1901

Republican Booker T. Washington protested the Alabama Democrat Party’s refusal to permit voting by blacks.

May 29, 1902

Virginia Democrats implemented a new state constitution condemned by Republicans as illegal, reducing black voter registration by almost 90%.

February 12, 1909

On the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, black Republicans and women’s suffragists Ida Wells and Mary Terrell co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

May 21, 1919

The Republican House passed a constitutional amendment granting women the vote with 85% of Republicans and only 54% of Democrats in favor. In the Senate 80% of Republicans voted yes and almost half of Democrats voted no.

August 18, 1920

The Republican-authored 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote became part of the Constitution. Twenty-six of the 36 states needed to ratify had Republican-controlled legislatures.

January 26, 1922

The House passed a bill authored by U.S. Rep. Leonidas Dyer (R-MO) making lynching a federal crime. Senate Democrats blocked it by filibuster.

June 2, 1924

Republican President Calvin Coolidge signed a bill passed by the Republican Congress granting U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans.

October 3, 1924

Republicans denounced three-time Democrat presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan for defending the Ku Klux Klan at the 1924 Democratic National Convention.

June 12, 1929

First Lady Lou Hoover invited the wife of black Rep. Oscar De Priest (R-IL) to tea at the White House, sparking protests by Democrats across the country.

August 17, 1937

Republicans organized opposition to former Ku Klux Klansman and Democrat U.S. Senator Hugo Black who was later appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by FDR. Black’s Klan background was hidden until after confirmation.

June 24, 1940

The Republican Party platform called for the integration of the Armed Forces. For the balance of his terms in office, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (D) refused to order it.

August 8, 1945

Republicans condemned Harry Truman’s surprise use of the atomic bomb in Japan. It began two days after the Hiroshima bombing when former Republican President Herbert Hoover wrote that “The use of the atomic bomb, with its indiscriminate killing of women and children, revolts my soul.”

May 17, 1954

Earl Warren, California’s three-term Republican Governor and 1948 Republican vice presidential nominee, was nominated to be Chief Justice delivered the landmark decision “Brown v. Board of Education”.

November 25, 1955

Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s administration banned racial segregation of interstate bus travel.

March 12, 1956

Ninety-seven Democrats in Congress condemned the Supreme Court’s “Brown v. Board of Education” decision and pledged (Southern Manifesto) to continue segregation.

June 5, 1956

Republican federal judge Frank Johnson ruled in favor of the Rosa Parks decision striking down the “blacks in the back of the bus” law.

November 6, 1956

African-American civil rights leaders Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy voted for Republican Dwight Eisenhower for President.

September 9, 1957

President Eisenhower signed the Republican Party’s 1957 Civil Rights Act.

September 24, 1957

Sparking criticism from Democrats such as Senators John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, President Eisenhower deployed the 82nd Airborne Division to Little Rock, AR to force Democrat Governor Orval Faubus to integrate their public schools.

May 6, 1960

President Eisenhower signed the Republicans’ Civil Rights Act of 1960, overcoming a 125-hour, ’round-the-clock filibuster by 18 Senate Democrats.

May 2, 1963

Republicans condemned Bull Connor, the Democrat “Commissioner of Public Safety” in Birmingham, AL for arresting over 2,000 black schoolchildren marching for their civil rights.

September 29, 1963

Gov. George Wallace (D-AL) defied an order by U.S. District Judge Frank Johnson (appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower) to integrate Tuskegee High School.

June 9, 1964

Republicans condemned the 14-hour filibuster against the 1964 Civil Rights Act by U.S. Senator and former Ku Klux Klansman Robert Byrd (D-WV), who served in the Senate until his death in 2010.

June 10, 1964

Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) criticized the Democrat filibuster against 1964 Civil Rights Act and called on Democrats to stop opposing racial equality. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was introduced and approved by a majority of Republicans in the Senate. The Act was opposed by most southern Democrat senators, several of whom were proud segregationists — one of them being Al Gore Sr. (D). President Lyndon B. Johnson relied on Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican leader from Illinois, to get the Act passed.

August 4, 1965

Senate Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) overcame Democrat attempts to block 1965 Voting Rights Act. Ninety-four percent of Republicans voted for the landmark civil rights legislation while 27% of Democrats opposed. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, abolishing literacy tests and other measures devised by Democrats to prevent blacks from voting, was signed into law. A higher percentage of Republicans voted in favor.

February 19, 1976

President Gerald Ford formally rescinded President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s notorious Executive Order 9066 authorizing the internment of over 120,000 Japanese-Americans during WWII.

September 15, 1981

President Ronald Reagan established the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities to increase black participation in federal education programs.

June 29, 1982

President Ronald Reagan signed a 25-year extension of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

August 10, 1988

President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, compensating Japanese-Americans for the deprivation of their civil rights and property during the World War II internment ordered by FDR.

November 21, 1991

President George H. W. Bush signed the Civil Rights Act of 1991 to strengthen federal civil rights legislation.

August 20, 1996

A bill authored by U.S. Rep. Susan Molinari (R-NY) to prohibit racial discrimination in adoptions, part of Republicans’ “Contract With America”, became law.

July 2, 2010

Clinton says Byrd joined KKK to help him get elected

Just a “fleeting association”. Nothing to see here.

Only a willing fool (and there quite a lot out there) would accept and recite the nonsensical that one bright, sunny day Democrats and Republicans just up and decided to “switch” political positions and cite the “Southern Strategy” as the uniform knee-jerk retort. Even today, it never takes long for a Democrat to play the race card purely for political advantage.Thanks to the Democrat Party, blacks have the distinction of being the only group in the United States whose history is a work-in-progress.

The idea that “the Dixiecrats joined the Republicans” is not quite true, as you note. But because of Strom Thurmond it is accepted as a fact. What happened is that the **next** generation (post 1965) of white southern politicians — Newt, Trent Lott, Ashcroft, Cochran, Alexander, etc — joined the GOP.So it was really a passing of the torch as the old segregationists retired and were replaced by new young GOP guys. One particularly galling aspect to generalizations about “segregationists became GOP” is that the new GOP South was INTEGRATED for crying out loud, they accepted the Civil Rights revolution. Meanwhile, Jimmy Carter led a group of what would become “New” Democrats like Clinton and Al Gore.

There weren’t many Republicans in the South prior to 1964, but that doesn’t mean the birth of the southern GOP was tied to “white racism.” That said, I am sure there were and are white racist southern GOP. No one would deny that. But it was the southern Democrats who were the party of slavery and, later, segregation. It was George Wallace, not John Tower, who stood in the southern schoolhouse door to block desegregation! The vast majority of Congressional GOP voted FOR the Civil Rights of 1964-65. The vast majority of those opposed to those acts were southern Democrats. Southern Democrats led to infamous filibuster of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.The confusion arises from GOP Barry Goldwater’s vote against the ’64 act. He had voted in favor or all earlier bills and had led the integration of the Arizona Air National Guard, but he didn’t like the “private property” aspects of the ’64 law. In other words, Goldwater believed people’s private businesses and private clubs were subject only to market forces, not government mandates (“We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone.”) His vote against the Civil Rights Act was because of that one provision was, to my mind, a principled mistake.This stance is what won Goldwater the South in 1964, and no doubt many racists voted for Goldwater in the mistaken belief that he opposed Negro Civil Rights. But Goldwater was not a racist; he was a libertarian who favored both civil rights and property rights.Switch to 1968.Richard Nixon was also a proponent of Civil Rights; it was a CA colleague who urged Ike to appoint Warren to the Supreme Court; he was a supporter of Brown v. Board, and favored sending troops to integrate Little Rock High). Nixon saw he could develop a “Southern strategy” based on Goldwater’s inroads. He did, but Independent Democrat George Wallace carried most of the deep south in 68. By 1972, however, Wallace was shot and paralyzed, and Nixon began to tilt the south to the GOP. The old guard Democrats began to fade away while a new generation of Southern politicians became Republicans. True, Strom Thurmond switched to GOP, but most of the old timers (Fulbright, Gore, Wallace, Byrd etc etc) retired as Dems.Why did a new generation white Southerners join the GOP? Not because they thought Republicans were racists who would return the South to segregation, but because the GOP was a “local government, small government” party in the old Jeffersonian tradition. Southerners wanted less government and the GOP was their natural home.Jimmy Carter, a Civil Rights Democrat, briefly returned some states to the Democrat fold, but in 1980, Goldwater’s heir, Ronald Reagan, sealed this deal for the GOP. The new “Solid South” was solid GOP.BUT, and we must stress this: the new southern Republicans were *integrationist* Republicans who accepted the Civil Rights revolution and full integration while retaining their love of Jeffersonian limited government principles.

Oh wait, princess, I am not done yet.

Where Teddy Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to dinner, Woodrow Wilson re-segregated the U.S. government and had the pro-Klan film “Birth of a Nation” screened in his White House.

Wilson and FDR carried all 11 states of the Old Confederacy all six times they ran, when Southern blacks had no vote. Disfranchised black folks did not seem to bother these greatest of liberal icons.

As vice president, FDR chose “Cactus Jack” Garner of Texas who played a major role in imposing a poll tax to keep blacks from voting.

Among FDR’s Supreme Court appointments was Hugo Black, a Klansman who claimed FDR knew this when he named him in 1937 and that FDR told him that “some of his best friends” in Georgia were Klansmen.

Black’s great achievement as a lawyer was in winning acquittal of a man who shot to death the Catholic priest who had presided over his daughter’s marriage to a Puerto Rican.

In 1941, FDR named South Carolina Sen. “Jimmy” Byrnes to the Supreme Court. Byrnes had led filibusters in 1935 and 1938 that killed anti-lynching bills, arguing that lynching was necessary “to hold in check the Negro in the South.”

FDR refused to back the 1938 anti-lynching law.

“This is a white man’s country and will always remain a white man’s country,” said Jimmy. Harry Truman, who paid $10 to join the Klan, then quit, named Byrnes Secretary of State, putting him first in line of succession to the presidency, as Harry then had no V.P.

During the civil rights struggles of the ‘50s and ‘60s, Gov. Orval Faubus used the National Guard to keep black students out of Little Rock High. Gov. Ross Barnett refused to let James Meredith into Ole Miss. Gov. George Wallace stood in the door at the University of Alabama, to block two black students from entering.

All three governors were Democrats. All acted in accord with the “Dixie Manifesto” of 1956, which was signed by 19 senators, all Democrats, and 80 Democratic congressmen.

Among the signers of the manifesto, which called for massive resistance to the Brown decision desegregating public schools, was the vice presidential nominee on Adlai’s Stevenson’s ticket in 1952, Sen. John Sparkman of Alabama.

Though crushed by Eisenhower, Adlai swept the Deep South, winning both Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas.

Do you suppose those Southerners thought Adlai would be tougher than Ike on Stalin? Or did they think Adlai would maintain the unholy alliance of Southern segregationists and Northern liberals that enabled Democrats to rule from 1932 to 1952?

The Democratic Party was the party of slavery, secession and segregation, of “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman and the KKK. “Bull” Connor, who turned the dogs loose on black demonstrators in Birmingham, was the Democratic National Committeeman from Alabama.

And Nixon?

In 1956, as vice president, Nixon went to Harlem to declare, “America can’t afford the cost of segregation.” The following year, Nixon got a personal letter from Dr. King thanking him for helping to persuade the Senate to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Nixon supported the civil rights acts of 1964, 1965 and 1968.

In the 1966 campaign, as related in my new book “The Greatest Comeback: How Richard Nixon Rose From Defeat to Create the New Majority,” out July 8, Nixon blasted Dixiecrats “seeking to squeeze the last ounces of political juice out of the rotting fruit of racial injustice.”

Nixon called out segregationist candidates in ‘66 and called on LBJ, Hubert Humphrey and Bobby Kennedy to join him in repudiating them. None did. Hubert, an arm around Lester Maddox, called him a “good Democrat.” And so were they all – good Democrats.

While Adlai chose Sparkman, Nixon chose Spiro Agnew, the first governor south of the Mason Dixon Line to enact an open-housing law.

In Nixon’s presidency, the civil rights enforcement budget rose 800 percent. Record numbers of blacks were appointed to federal office. An Office of Minority Business Enterprise was created. SBA loans to minorities soared 1,000 percent. Aid to black colleges doubled.

Nixon won the South not because he agreed with them on civil rights – he never did – but because he shared the patriotic values of the South and its antipathy to liberal hypocrisy.

When Johnson left office, 10 percent of Southern schools were desegregated.

When Nixon left, the figure was 70 percent. Richard Nixon desegregated the Southern schools, something you won’t learn in today’s public schools.

Not done there yet, snowflake.

1964:George Romney, Republican civil rights activist. That Republicans have let Democrats get away with this mountebankery is a symptom of their political fecklessness, and in letting them get away with it the GOP has allowed itself to be cut off rhetorically from a pantheon of Republican political heroes, from Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass to Susan B. Anthony, who represent an expression of conservative ideals as true and relevant today as it was in the 19th century.

Perhaps even worse, the Democrats have been allowed to rhetorically bury their Bull Connors, their longstanding affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan, and their pitiless opposition to practically every major piece of civil-rights legislation for a century.

Republicans may not be able to make significant inroads among black voters in the coming elections, but they would do well to demolish this myth nonetheless.

Even if the Republicans’ rise in the South had happened suddenly in the 1960s (it didn’t) and even if there were no competing explanation (there is), racism — or, more precisely, white southern resentment over the political successes of the civil-rights movement — would be an implausible explanation for the dissolution of the Democratic bloc in the old Confederacy and the emergence of a Republican stronghold there.

That is because those southerners who defected from the Democratic Party in the 1960s and thereafter did so to join a Republican Party that was far more enlightened on racial issues than were the Democrats of the era, and had been for a century.

There is no radical break in the Republicans’ civil-rights history: From abolition to Reconstruction to the anti-lynching laws, from the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, and 1964, there exists a line that is by no means perfectly straight or unwavering but that nonetheless connects the politics of Lincoln with those of Dwight D. Eisenhower.

And from slavery and secession to remorseless opposition to everything from Reconstruction to the anti-lynching laws, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, there exists a similarly identifiable line connecting John Calhoun and Lyndon Baines Johnson.

Supporting civil-rights reform was not a radical turnaround for congressional Republicans in 1964, but it was a radical turnaround for Johnson and the Democrats.

The depth of Johnson’s prior opposition to civil-rights reform must be digested in some detail to be properly appreciated.

In the House, he did not represent a particularly segregationist constituency (it “made up for being less intensely segregationist than the rest of the South by being more intensely anti-Communist,” as the New York Times put it), but Johnson was practically antebellum in his views.

Never mind civil rights or voting rights: In Congress, Johnson had consistently and repeatedly voted against legislation to protect black Americans from lynching.

As a leader in the Senate, Johnson did his best to cripple the Civil Rights Act of 1957; not having votes sufficient to stop it, he managed to reduce it to an act of mere symbolism by excising the enforcement provisions before sending it to the desk of President Eisenhower.

Johnson’s Democratic colleague Strom Thurmond nonetheless went to the trouble of staging the longest filibuster in history up to that point, speaking for 24 hours in a futile attempt to block the bill.

The reformers came back in 1960 with an act to remedy the deficiencies of the 1957 act, and Johnson’s Senate Democrats again staged a record-setting filibuster.

In both cases, the “master of the Senate” petitioned the northeastern Kennedy liberals to credit him for having seen to the law’s passage while at the same time boasting to southern Democrats that he had taken the teeth out of the legislation.

Johnson would later explain his thinking thus: “These Negroes, they’re getting pretty uppity these days, and that’s a problem for us, since they’ve got something now they never had before: the political pull to back up their uppityness. Now we’ve got to do something about this — we’ve got to give them a little something, just enough to quiet them down, not enough to make a difference.”

Johnson did not spring up from the Democratic soil ex nihilo.

Not one Democrat in Congress voted for the Fourteenth Amendment.

Not one Democrat in Congress voted for the Fifteenth Amendment.

Not one voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Dwight Eisenhower as a general began the process of desegregating the military, and Truman as president formalized it, but the main reason either had to act was that President Woodrow Wilson, the personification of Democratic progressivism, had resegregated previously integrated federal facilities. (“If the colored people made a mistake in voting for me, they ought to correct it,” he declared.)

Klansmen from Senator Robert Byrd to Justice Hugo Black held prominent positions in the Democratic Party — and President Wilson chose the Klan epic Birth of a Nation to be the first film ever shown at the White House.

Johnson himself denounced an earlier attempt at civil-rights reform as the “nigger bill.” So what happened in 1964 to change Democrats’ minds? In fact, nothing.

President Johnson was nothing if not shrewd, and he knew something that very few popular political commentators appreciate today: The Democrats began losing the “solid South” in the late 1930s — at the same time as they were picking up votes from northern blacks.

The Civil War and the sting of Reconstruction had indeed produced a political monopoly for southern Democrats that lasted for decades, but the New Deal had been polarizing. It was very popular in much of the country, including much of the South — Johnson owed his election to the House to his New Deal platform and Roosevelt connections — but there was a conservative backlash against it, and that backlash eventually drove New Deal critics to the Republican Party.

Likewise, adherents of the isolationist tendency in American politics, which is never very far from the surface, looked askance at what Bob Dole would later famously call “Democrat wars” (a factor that would become especially relevant when the Democrats under Kennedy and Johnson committed the United States to a very divisive war in Vietnam).

The tiniest cracks in the Democrats’ southern bloc began to appear with the backlash to FDR’s court-packing scheme and the recession of 1937.

Republicans would pick up 81 House seats in the 1938 election, with West Virginia’s all-Democrat delegation ceasing to be so with the acquisition of its first Republican.

Kentucky elected a Republican House member in 1934, as did Missouri, while Tennessee’s first Republican House member, elected in 1918, was joined by another in 1932.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Republican Party, though marginal, began to take hold in the South — but not very quickly: Dixie would not send its first Republican to the Senate until 1961, with Texas’s election of John Tower.

At the same time, Republicans went through a long dry spell on civil-rights progress.

Many of them believed, wrongly, that the issue had been more or less resolved by the constitutional amendments that had been enacted to ensure the full citizenship of black Americans after the Civil War, and that the enduring marginalization of black citizens, particularly in the Democratic states, was a problem that would be healed by time, economic development, and organic social change rather than through a second political confrontation between North and South.

As late as 1964, the Republican platform argued that “the elimination of any such discrimination is a matter of heart, conscience, and education, as well as of equal rights under law.”

The conventional Republican wisdom of the day held that the South was backward because it was poor rather than poor because it was backward.

And their strongest piece of evidence for that belief was that Republican support in the South was not among poor whites or the old elites — the two groups that tended to hold the most retrograde beliefs on race.

Instead, it was among the emerging southern middle class.

This fact was recently documented by professors Byron Shafer and Richard Johnston in The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (Harvard University Press, 2006).

Which is to say: The Republican rise in the South was contemporaneous with the decline of race as the most important political question and tracked the rise of middle-class voters moved mainly by economic considerations and anti-Communism.

The South had been in effect a Third World country within the United States, and that changed with the post-war economic boom.

As Clay Risen put it in the New York Times: “The South transformed itself from a backward region to an engine of the national economy, giving rise to a sizable new wealthy suburban class.

This class, not surprisingly, began to vote for the party that best represented its economic interests: the GOP. Working-class whites, however — and here’s the surprise — even those in areas with large black populations, stayed loyal to the Democrats.

This was true until the 90s, when the nation as a whole turned rightward in Congressional voting.” The mythmakers would have you believe that it was the opposite: that your white-hooded hillbilly trailer-dwelling tornado-bait voters jumped ship because LBJ signed a civil-rights bill (passed on the strength of disproportionately Republican support in Congress). The facts suggest otherwise. There is no question that Republicans in the 1960s and thereafter hoped to pick up the angry populists who had delivered several states to Wallace.

That was Patrick J. Buchanan’s portfolio in the Nixon campaign.

But in the main they did not do so by appeal to racial resentment, direct or indirect.

The conservative ascendency of 1964 saw the nomination of Barry Goldwater, a western libertarian who had never been strongly identified with racial issues one way or the other, but who was a principled critic of the 1964 act and its extension of federal power.

Goldwater had supported the 1957 and 1960 acts but believed that Title II and Title VII of the 1964 bill were unconstitutional, based in part on a 75-page brief from Robert Bork.

But far from extending a welcoming hand to southern segregationists, he named as his running mate a New York representative, William E. Miller, who had been the co-author of Republican civil-rights legislation in the 1950s.

The Republican platform in 1964 was hardly catnip for Klansmen: It spoke of the Johnson administration’s failure to help further the “just aspirations of the minority groups” and blasted the president for his refusal “to apply Republican-initiated retraining programs where most needed, particularly where they could afford new economic opportunities to Negro citizens.”

Other planks in the platform included: “improvements of civil rights statutes adequate to changing needs of our times; such additional administrative or legislative actions as may be required to end the denial, for whatever unlawful reason, of the right to vote; continued opposition to discrimination based on race, creed, national origin or sex.”

And Goldwater’s fellow Republicans ran on a 1964 platform demanding “full implementation and faithful execution of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and all other civil rights statutes, to assure equal rights and opportunities guaranteed by the Constitution to every citizen.” Some dog whistle.

Of course there were racists in the Republican Party. There were racists in the Democratic Party. The case of Johnson is well documented, while Nixon had his fantastical panoply of racial obsessions, touching blacks, Jews, Italians (“Don’t have their heads screwed on”), Irish (“They get mean when they drink”), and the Ivy League WASPs he hated so passionately (“Did one of those dirty bastards ever invite me to his f***ing men’s club or goddamn country club? Not once”).

But the legislative record, the evolution of the electorate, the party platforms, the keynote speeches — none of them suggests a party-wide Republican about-face on civil rights.

Neither does the history of the black vote.

While Republican affiliation was beginning to grow in the South in the late 1930s, the GOP also lost its lock on black voters in the North, among whom the New Deal was extraordinarily popular.

By 1940, Democrats for the first time won a majority of black votes in the North. This development was not lost on Lyndon Johnson, who crafted his Great Society with the goal of exploiting widespread dependency for the benefit of the Democratic Party.

Unlike the New Deal, a flawed program that at least had the excuse of relying upon ideas that were at the time largely untested and enacted in the face of a worldwide economic emergency, Johnson’s Great Society was pure politics.

Johnson’s War on Poverty was declared at a time when poverty had been declining for decades, and the first Job Corps office opened when the unemployment rate was less than 5 percent.

Congressional Republicans had long supported a program to assist the indigent elderly, but the Democrats insisted that the program cover all of the elderly — even though they were, then as now, the most affluent demographic, with 85 percent of them in households of above-average wealth.

Democrats such as Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Anthony J. Celebrezze argued that the Great Society would end “dependency” among the elderly and the poor, but the programs were transparently designed merely to transfer dependency from private and local sources of support to federal agencies created and overseen by Johnson and his political heirs.

In the context of the rest of his program, Johnson’s unexpected civil-rights conversion looks less like an attempt to empower blacks and more like an attempt to make clients of them.

If the parties had in some meaningful way flipped on civil rights, one would expect that to show up in the electoral results in the years following the Democrats’ 1964 about-face on the issue.

Nothing of the sort happened: Of the 21 Democratic senators who opposed the 1964 act, only one would ever change parties.

Nor did the segregationist constituencies that elected these Democrats throw them out in favor of Republicans: The remaining 20 continued to be elected as Democrats or were replaced by Democrats.

It was, on average, nearly a quarter of a century before those seats went Republican. If southern rednecks ditched the Democrats because of a civil-rights law passed in 1964, it is strange that they waited until the late 1980s and early 1990s to do so. They say things move slower in the South — but not that slow.

Republicans did begin to win some southern House seats, and in many cases segregationist Democrats were thrown out by southern voters in favor of civil-rights Republicans.

One of the loudest Democratic segregationists in the House was Texas’s John Dowdy.

Dowdy was a bitter and buffoonish opponent of the 1964 reforms.

He declared the reforms “would set up a despot in the attorney general’s office with a large corps of enforcers under him; and his will and his oppressive action would be brought to bear upon citizens, just as Hitler’s minions coerced and subjugated the German people.

Dowdy went on: “I would say this — I believe this would be agreed to by most people: that, if we had a Hitler in the United States, the first thing he would want would be a bill of this nature.” (Who says political rhetoric has been debased in the past 40 years?)

Dowdy was thrown out in 1966 in favor of a Republican with a very respectable record on civil rights, a little-known figure by the name of George H. W. Bush.

It was in fact not until 1995 that Republicans represented a majority of the southern congressional delegation — and they had hardly spent the Reagan years campaigning on the resurrection of Jim Crow.

It was not the Civil War but the Cold War that shaped midcentury partisan politics.

Eisenhower warned the country against the “military-industrial complex,” but in truth Ike’s ascent had represented the decisive victory of the interventionist, hawkish wing of the Republican Party over what remained of the America First/Charles Lindbergh/Robert Taft tendency.

The Republican Party had long been staunchly anti-Communist, but the post-war era saw that anti-Communism energized and looking for monsters to slay, both abroad — in the form of the Soviet Union and its satellites — and at home, in the form of the growing welfare state, the “creeping socialism” conservatives dreaded.

By the middle 1960s, the semi-revolutionary Left was the liveliest current in U.S. politics, and Republicans’ unapologetic anti-Communism — especially conservatives’ rhetoric connecting international socialism abroad with the welfare state at home — left the Left with nowhere to go but the Democratic Party. Vietnam was Johnson’s war, but by 1968 the Democratic Party was not his alone.

The schizophrenic presidential election of that year set the stage for the subsequent transformation of southern politics: Segregationist Democrat George Wallace, running as an independent, made a last stand in the old Confederacy but carried only five states.

Republican Richard Nixon, who had helped shepherd the 1957 Civil Rights Act through Congress, counted a number of Confederate states (North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee) among the 32 he carried.

Democrat Hubert Humphrey was reduced to a northern fringe plus Texas.

Mindful of the long-term realignment already under way in the South, Johnson informed Democrats worried about losing it after the 1964 act that “those states may be lost anyway.”

Subsequent presidential elections bore him out: Nixon won a 49-state sweep in 1972, and, with the exception of the post-Watergate election of 1976, Republicans in the following presidential elections would more or less occupy the South like Sherman.

Bill Clinton would pick up a handful of southern states in his two contests, and Barack Obama had some success in the post-southern South, notably Virginia and Florida.

The Republican ascendancy in Dixie is associated with several factors: The rise of the southern middle class, The increasingly trenchant conservative critique of Communism and the welfare state, The Vietnam controversy, The rise of the counterculture, law-and-order concerns rooted in the urban chaos that ran rampant from the late 1960s to the late 1980s, and The incorporation of the radical Left into the Democratic party.

Individual events, especially the freak show that was the 1968 Democratic convention, helped solidify conservatives’ affiliation with the Republican Party. Democrats might argue that some of these concerns — especially welfare and crime — are “dog whistles” or “code” for race and racism. However, this criticism is shallow in light of the evidence and the real saliency of those issues among U.S. voters of all backgrounds and both parties for decades. Indeed, Democrats who argue that the best policies for black Americans are those that are soft on crime and generous with welfare are engaged in much the same sort of cynical racial calculation President Johnson was practicing. Johnson informed skeptical southern governors that his plan for the Great Society was “to have them niggers voting Democratic for the next two hundred years.” Johnson’s crude racism is, happily, largely a relic of the past, but his strategy endures.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pics: HPL, the Great Old Writer.

Intro: Notes for Lovecraft's 1st issue of The Conservative.

Specifically, on the article "The Crime of Crimes."

Notes:

1. Proofreading is the art of reviewing unpublished works for mistakes & fixing them.

2. Diction is the word selection writers use to create feelings in readers' heads.

Pic: Map of the enemies in WW1. The green ones are the 'good' guys.

3. The European War & The Great War were both names for World War One.

It earned these names due to the global scale of the fighting - which occurred in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Pacific Ocean & the Middle East.

WW1 also had the 5th largest death toll in history - from 15 to 30 million victims.

4. Socialists were actually against the war.

As it had workers killing each other for their bosses' interests.

But, after war was declared, Socialists backed their countries & supported the war.

5. The aristocracy are, in some places, the highest social class - holding titles & offices thru hereditary 'rights.'

Pic: Map of Serbia today.

6. Serbia, before WW1, was being threatened by the Austria/Hungarian Empire.

Worse, the Serbians were exhausted - they had just fought 2 Balkan wars!

They were about to give Austrian trains a route to the Mediterranean Ocean, when the Austrian Archduke was assassinated - in Sarajevo, Serbia!!

7. Austria was excluded from German affairs in 1866, when the end of the German Confederation occurred.

To retain its status, Austria negotiated with Hungary.

They agreed that their "foreign affairs & defense" were the same for both empires.

So, the Dual Monarchy (or, Hapsburg Monarchy) was born.

8. Belgian neutrality existed since The Treaty of London in 1839.

But, Germany invaded Belgium in 1914, to avoid fortifications along the French-German border.

This pulled Great Britain into WW1 as they were the one's charged with protecting Belgium's neutrality.

9. Anthropology studies what makes us human.

It's 4 branches are archaeological, biological, cultural & linguistic studies.

Pic: Huxley &, by mistake, Mongolia...

10. Aldous Huxley was a British writer, philosopher & critic.

His "Brave New World" is a future dystopia, whose citizens are bio- engineered into a social hierarchy based on intelligence.

The story foretells many different advances used, in the novel, to keep citizens in a peaceful state.

John, an ostracized & illicit 'savage', becomes a huge star in London.

But, John sees this 'civilization' as being "an empty society."

Jaded, he retires to an abandoned lighthouse to practice a frugal solitary lifestyle.

Unfortunately, it actually leads to his death...

John is an intensely moral person, living to a Shakespearean code but, he's also a bit naive.

Yet, he finally sees that technology & consumerism are poor substitutes for freedom, dignity & integrity.

11. Ethnology is the study of people's characteristics, their variety & the relationships between them.

12. Aryan is a Nazi concept about white, non-Jewish folk (descended from Nordic nations) as being a superior racial group.

Pics: The old Aryan idea (starting South of the Caucasian Mts.) that Lovecraft knew.

And, the more modern version - North of the Caucasians...

But, in actuality, Aryan described people who spoke the Proto-Indo- European languages.

The Indo-Europeans were their 'descendants'...

Pic: Another version of the spread of Aryan languages.

13. The Medieval Era or Middle Ages lasted from the fall of Rome in 476 til the start of the Renaissance in the 1400s.

The Early Middle Ages (from 476 til 900s AD) were known as the Dark Ages - due to a decrease in culture & science.

That's some 400 years of rebuilding & moving on to feudalism...

14. No excuse & no concrete evidence. Just a lot of hot air, racist ideas & dramatic posturing.

15. "No branch of civilization is not of his (white men) making."

1st, you can't prove a double negative - they cancel each other out.

And, 2nd of all, civilization was made up by the ancient Egyptians & almost as old Sumerians (now, modern Iraqi Arabs).

So, Howard's lying right off of the bat...

The first laws were not made by white men.

Nor were the 1st cities made by Aryans.

The wheel was not invented by whitey.

Need we go on?

Next: More Notes!!

0 notes

Text