#664 bce

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ram's-head Amulet, Egyptian, 712-664 BCE

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Egyptian Jewellery, Lapis Lazuli Amulets

From left to right: 1 Frog Amulet 664–332 B.C. 2 Heart Amulet 664–334 BCE 3 Lion and Bull Amulet 522–343 B.C. 4 Cat Amulet 1550–1295 B.C. 5 Ba Amulet 664–332 B.C. 6 Lion Amulet 1550–1295 B.C. 7 Fish Amulet 1550–1295 B.C. 8 Female Sphinx Amulet 1981–1550 B.C. 9 Harpokrates Amulet ? 1850–1640 B.C. 10 Falcon Amulet 664–332 B.C.

#ancient history#antiquity#ancient civilizations#ancient art#jewelry#lapis lazuli#history#antiquities#jewellery#ancient egypt#antiques#ancient jewelry#pendant#egyptology#egypt#ancientegyptianjewellery#amulet#collections#archiveofmyown#archaeology#artefact

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Egyptian faience emblem from a sistrum (rattle), depicting the goddess Hathor. Made by an unknown artist during the Late Period (Dynasties 26-29 = 664-332 BCE). Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#art#art history#ancient art#Egypt#Ancient Egypt#Egyptian art#Ancient Egyptian art#artifact#artifacts#sistrum#Egyptian religion#Ancient Egyptian religion#Hathor#faience#Late Period#Metropolitan Museum of Art

450 notes

·

View notes

Note

omg i loved your “shifting to Italy” post and was wondering if you could do one for ancient egypt? xx (you don’t have to ofc just a suggestion!!)

shifting to ancient egypt? gotch ya.

ancient egypt was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the nile river in northeast africa.

act i. when are you?

based on your time period, you will have very much different experiences. i’d suggest you to research which one you are more interested in shifting.

predynastic ( c. 6000-3150 BCE ) preceding recorded history, saw the development of early settlements and the emergence of distinct cultures in the nile valley.

early dynastic period ( c. 3100-2686 BCE ) marked by the unification of upper and lower Egypt, the first and second dynasties ruled during this time, establishing the foundations of the egyptian state.

old kingdom ( c. 2686-2181 BCE ) a period of great power and prosperity, characterized by the construction of the pyramids and the establishment of the pharaoh as a divine ruler.

first intermediate period ( c. 2181-2040 BCE ) period of political instability and fragmentation following the decline of old kingdom.

middle kingdom ( c. 2040-1640 BCE ) period of reunification and renewed prosperity, with advancements in art, architecture, and literature.

second intermediate period ( c. 1640-1550 BCE ) another period of instability, marked by the rise of the hyksos and the fragmentation of egyptian rule.

new kingdom ( c. 1550-1070 BCE) a period of great expansion and military power, with powerful pharaohs like hatshepsut, akhenaten, and ramses ii.

third intermediate period ( c. 1070-664 BCE ) period of decline and fragmentation, with various dynasties vying for power.

late period ( c. 664-332 BCE ) period of foreign rule, with egypt ruled by the assyrians, egyptians, and persians.

roman period ( 30 BCE - 641 CE ) egypt became a province of the roman empire, marked by roman administration and culture.

act ii. who are you?

you are in the middle of a society who has a strict social structure, and where your status will shape your daily life and power. you are born with it, and only scribes, soldiers and artisans could rise. from the most protected to the least one:

pharaoh. used as a title for absolute monarch since under the new kingdom, often called horus on earth. had control over laws, military, religion, and land. lived in luxurious palaces with servants, and wore a double crown ( pschent ) to symbolise his status as ruler. the most well-known are tutankhamun, ramesses ii, and akhenaten.

pharaoh’s family. wives, children and sibilings had high-ranking positions in the government and religion.

nobles. were high-ranking government officials, including the vizier ( the pharaoh's chief advisor a.k.a prime minister, who oversaw taxes, justice, and administration ) and nomarchs ( governors, controlled egypt’s provinces and managed local social ).

priests. they played a crucial role in religious ceremonies and rituals, and they held significant influence in society.

high priest: appointed by the pharaoh, held the highest authority within the priesthood, performing the most important rituals and managing the temple's affairs.

wab priests: carried out essential but mundane tasks, such as preparing for festivals and maintaining the temple complex.

other priests: who read funeral liturgies ( hery-heb ) who read incantatory formulas from the book of the dead ( khereb priests ) and those involved in mummification ( paraschists, taricheutes, and colchytes ).

priestesses: women could also be priests, with their roles varying depending on the specific cult or deity.

scribes. highly respected, literate individuals who held important administrative and clerical positions, responsible for recording and documenting everything from daily activities to royal decrees. part of the elite 1% of the population that could read and write. they used reed pens, black ink made from soot and gum, adding red oxide to make red ink, and palettes.

artisans. they lived in special workers villages ( deir el-medina ) and included stonecutters, painters, carpenters, sculptors, jewelers, and metalworkers. they created tombs, statues, temples, furniture and luxury goods.

farmers. made up the majority of population and they walked in fields, growing wheat, barley, flax and vegetables. during flood seasons they usually worked with artisans.

slaves. prisoners of war, debtors and criminals. they worked in nobles households ( cooking, cleaning, taking care of children ), temples, mines and quarries; some could earn freedom and better positions over time.

act iii. where are you?

where you live will shape your experience drastically. normal houses were built of mud-bricks with floors made from earth, and they had living rooms, kitchens and bedrooms, and many of the large objects that we can move around ( like seats and ovens ) were built into the house. there was no gas or electricity, meaning that food was cooked in stone ovens, using a fire for heat. to keep food, pits were dug and food was stored below ground level.

cities, they were the heart of the civilisation. center of political activity, religion, and economic powers. in the cities lived pharaohs and nobles ( pharaohs lived in the ‘great house’ or “per ‘aa. palaces were lavish, with evidence suggesting sprawling complexes with large dining rooms, and other amenities reflecting the pharaoh's status ) priests and scribes ( temple complexes, government departments, and even private households, depending on their specific duties and employers ) artisans and merchants ( often lived in distinct workmen's villages like deir el-medina, located near the valley of the kings ) slaves ( lived in simple dwellings, possibly separate from their owners' homes, or within the same household as servants ) but…… what cities? here some examples.

memphis. the capital of the old kingdom. full of loud markets, stone temples, and busy workshops. the most notorious thing are the white walls, the great temple of ptah, statues, palaces ( huge monuments of pharaohs ) craftsmen’s quarters ( people making gold jewelry, statues, and linen ) the nile docks ( ships unloading grain, wine, and goods from nubia and the levant ) …. one of the official religious centers as it was the worship center for the holy triad of the creator god of ptah, his wife sekhmet and nefertem.

thebes. the city of the gods. religious and cultural powerhouse, full of priests, scribes, tomb builders, and travelers. you’d see karnak and luxor temples ( giant temples with sphinx-lined roads ) street performers, food vendors, and boat festivals on the nile. markets full of incense, perfume, and imported goods from the red sea trade.

deir-el medina. there were around 68 houses, made of mud-brick built on stone foundations. letters, legal documents, statues and tombs tell us about family and working life. many of the men and women could read. women baked bread and brewed beer. the village had a court of law and everyone had a right to a trial. there was a local police, the medjay, to keep order. the people of deir-el medina also had medical treatment. they could get prescriptions of ingredients, prayers and spells from the physicians.

act iv. how is your social life?

we are talking about a very social civilisation….. if you were rich. their daily lives revolved around family, work, festivals, and entertainment, and they knew how to balance duty and pleasure ( fun fact: for them sexuality was sacred ).

marriage. frequently arranged by parents, they were a primarily a social and economic arrangement, not a religious or legal ceremony, where couples were considered married once they started living together, often after a party or celebration. while divorce was possible, it was difficult, and women were often protected from divorce by marriage contracts that placed financial burdens on men.

friendship. was significant aspect of life in ancient egypt, strong bonds and social obligations between individuals, including the idea of ‘friends’ being part of a broader social circle beyond immediate family.

banquets. they were lavish celebrations featuring large gatherings of family and friends, music, dance, and copious amounts of food and drink, frequently held near tombs to facilitate communication with the deceased. they were hosted by wealthy families and nobles. entertainment consisted in harpists, flutists, dancers, acrobats. the food ?? roast duck, fish, bread, figs, wine and beer. the banquets were often held in tents or colonnaded spaces, which were sometimes depicted in tomb. fun fact : particularly during banquets and celebrations, people wore scented wax cones on their heads, which melted and released a pleasant fragrance.

public festivals and religious celebrations. the most well-known festivals were: opet festival ( in thebes ) was a celebration of amun and mut’s marriage, statues was paraded through the streets. hathor festival is a wild party with drinking, music, and dance. wepet renpet ( new year’s ) is a huge nile-side festival with feasts and fireworks, celebrated mid-july. beautiful festival of the valley is a state festival, initiated by mentuhotep ii, and celebrated the bonds between the living and the dead, with citizens strengthening their bonds with the deceased. wag festival involved making paper boats containing shrines to souls and setting them out on the river nile to float towards the west, commemorating the death and rebirth of osiris.

markets. like today, bustling marketplaces were a social hotspot. the steet vendors sold jewelry, makeup ( kohl eyeliner and scented oils ) fine linen clothes, sandals, spices, perfumes, and exotic imports.

music. they usually played harps, flutes, drums, and lyres at parties and religious events while women, were often professional dancers, were hired for feasts and ceremonies.

act v. what are you eating?

bread was a fundamental part of the diet, made from emmer wheat or barley. it was eaten at every meal and was considered a basic element of human life.

beer was a common beverage.

vegetables. were a regular part of the egyptian diet, with a variety of options available, including onions, garlic, lentils, and cucumbers.

fish was a readily available and nutritious food source, it was prepared in various ways, including frying, smoking, and boiling.

fruits like figs and dates were also part of the ancient egyptian diet and were often included in offerings to the gods.

oils were derived from ben-nuts, sesame, linseed and castor oils. honey was used as a sweetener, and vinegar may have also been used. seasonings included salt, juniper, aniseed, coriander, cumin, fennel, fenugreek, and poppyseed.

meat. the wealthy would enjoy pork, mutton, and beef.

poultry, such as ducks and geese.

dairy products, like cheese, butter, and cream.

wine was a product of great importance, offered in funerary rituals and in temples to worship gods and consumed daily by the upper classes during meals and parties.

act vi. what are you wearing?

reflected both the hot climate and social status, with the wealthy adorning themselves with finer materials and elaborate jewelry.

linen. the primary fabric, made from the flax plant, was favored for its breathability and comfort in the hot climate.

wool. while known, wool was considered impure and primarily used by the wealthy for overcoats, but was forbidden in temples and sanctuaries.

jewelry. gold, lapis lazuli, turquoise, and other precious materials were used to create elaborate jewelry, including necklaces, rings, bracelets, and amulets.

women’s clothing. they wore full-length dresses with one or two shoulder straps, which could be pleated or draped. the wealthy often wore flowing, sheer dresses layered with colorful shawls or capes.

men’s clothing. kilt-like skirts ( schenti ) are a wrap-around skirt, tied at the waist, with variations in length depending on the era and fashion trends. loincloth and headdresses.

children’s clothing. they wore simple garments, often loincloths or short kilts for boys, and simple linen dresses for girls.

cosmetics. ochre for lips and cheeks, henna for fingernails, and kohl for outlining eyes and coloring eyebrows.

hair. men and women often shaved their heads, and instead they used wigs.

sandals. while many went barefoot, sandals were sometimes worn.

makeup, particularly black kohl eyeliner, was used by both men and women for both aesthetic and practical purposes, with ingredients like galena and malachite used to create pigments, and cosmetics were also seen as having spiritual and protective significance.

kohl eyeliner. a dark, black eyeliner made from ground galena (lead sulfide) and other ingredients like soot, which was used to outline the eyes. it was believed to protect the eyes from the sun's glare and to repel insects. applied in a distinctive style, with lines drawn above and below the eyes, sometimes slightly arched at the ends.

red pigments. red ochre, a clay that was dried in the sun, was used for blush and lipstick and it was also used to stain nails with henna.

green eye shadow. a.k.a malachite, a copper-based mineral, was ground and mixed with water to make a green eyeshadow.

oil and creams. scented oils and creams were used to moisturize the skin and mask body odor. ingredients included myrrh, thyme, marjoram, chamomile, lavender, lily, peppermint, rosemary, cedar, rose, aloe, olive oil, sesame oil and almond oil.

lipstick. red lipstick was made from red ochre and other pigments, theredder the lips, the higher the social status.

note: don’t forget to script safety things!

#kerry's drs#reality shifting#shiftblr#shifting blog#shifting#shifting community#shifting antis dni#shifting motivation#shifting consciousness#shifting diary#shiftingrealities#shiftinconsciousness#shifting ideas#shifting realities#shifting reality#reality shift#shifters#shift#anti shifters dni#how to shift#reality shifter#reality shifting community#shiftblr community#shifting advice#shifting help#shifting journey#shifting methods#shifting script#shifting to desired reality#shifting stories

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

for a mere 1000 USD you could become the proud new owner of egyptian dark serpentine phallus amulet late period ca. 664-332 BCE

#i was looking for cute faience animals and found this instead#tagamemnon#egyptian stuff#queueusque tandem abutere catilina patientia nostra

372 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Hanfu · 漢服]The relationship between women in history is not just love rivals,

“but also thousands of years later, everyone knows that it is me and you.”

Let's get to know about them/她们 in China history.

1.【Han Dynasty】:Princess Jieyou (解忧公主) & Feng Liao (馮嫽)

Princess Jieyou (Chinese: 解忧公主; 121 BC – 49 BC), born Liu Jieyou (Chinese: 刘解忧), was a Chinese princess sent to marry the leader of the Wusun kingdom as part of the Western Han Chinese policy of heqin(和亲).

As the granddaughter of the disgraced Prince Liu Wu (劉戊) who had taken part in the disastrous Rebellion of the Seven States,her status was low enough that she was sent to replace Princess Liu Xijun (劉細君) after her untimely death and marry the Wusun king Cunzhou (岑陬).

Jieyou lived among the Wusun for fifty years and did much work to foster relations between the surrounding kingdoms and the Han. She was particularly reliant upon her attendant, Feng Liao, whom she dispatched as an emissary to Wusun kingdoms and even to the Han Court. She faced opposition from pro-Xiongnu members of the Wusun royalty, particularly Wengguimi’s Xiongnu wife. When word came that the Xiongnu planned to attack Wusun, she convinced her husband to send for aid from the Han Emperor. Emperor Wu of Han sent 150,000 cavalrymen to support the Wusun forces and drive back the Xiongnu.

In 51 BCE at the age of 70, Jieyou asked to be allowed to retire and return to the Han. Emperor Xuan of Han agreed and had her escorted back to Chang'an where she was welcomed with honor. She was given a grand palace with servants usually reserved for princesses of the imperial family. In 49 BCE, Jieyou died peacefully.

Feng Liao (馮嫽)

Feng Liao (馮嫽) was China's first official female diplomat,[citation needed] who represented the Han dynasty to Wusun (烏孫), which was in the Western Regions. It was a practice for the Imperial Court to foster alliances with the northern tribes via marriage, and two Han princesses had married Wusun kings.

Feng Liao was the maidservant of Princess Jieyou (解憂公主), who was married off to a Wusun king. Feng herself later married an influential Wusun general, whose good standing with Prince Wujiutu (烏就屠) of the kingdom later proved beneficial to the Han dynasty.

When Prince Wujiutu seized the throne of Wusun in 64 BC, after his father died, there was fear in the Imperial Court of Han that Wujiutu, whose mother was Xiongnu, would allow Wusun to become Xiongnu's vassal.

Zheng Ji, Governor of the Western Regions, recalled that Feng Liao had married into Wusun and with her familiarity of the Wusun customs, she was a prime candidate to persuade Wujiutu to ally his kingdom with Han. Wujiutu acceded and Emperor Xuan of Han (漢宣帝) sent for Feng. He praised her for her judgement and diplomacy, and appointed her as the official envoy to Wusun.

Wujiutu was conferred the title "Little King of Wusun" while his brother, the son by a Han princess, was named "Great King of Wusun". Wusun was divided between the two kings and tensions in that region were eased.

※Xiongnu: Xiongnu: A nomadic tribe that has occupied northern China for a long time. Later it gradually became a state. It harassed the borders of the Han Dynasty for a long time and robbed supplies.

------

With their efforts, the Wusun Kingdom gradually tended to support the Han Dynasty, and the Xiongnu's defeat in China also began.

------

2.【Tang Dynasty】:Shangguan Wan'er(上官婉儿)&Princess Taiping (太平公主)

Shangguan Wan'er/上官婉儿 (664 – 21 July 710) was a Chinese politician, poet, and imperial consort of the Wu Zhou and Tang dynasties. Described as a "female prime minister,"Shangguan rose from modest origins as a palace servant to become secretary and leading advisor to Empress Wu Zetian of Zhou. Under Empress Wu, Shangguan exercised responsibility for drafting imperial edicts and earned approbation for her writing style. She retained her influence as consort to Wu's son and successor, Emperor Zhongzong of Tang, holding the imperial consort rank of Zhaorong (昭容). Shangguan was also highly esteemed for her talent as a poet.Shangguan was also highly esteemed for her talent as a poet. In 710, after Emperor Zhongzong's death, Shangguan was killed during a palace coup that ended the regency of Empress Dowager Wei.

Princess Taiping (太平公主)lit. "Princess of Great Peace", personal name unknown, possibly Li Lingyue (李令月) (after 662 – 2 August 713) was a royal princess and prominent political figure of the Tang dynasty and her mother Wu Zetian's Zhou dynasty. She was the youngest daughter of Wu Zetian and Emperor Gaozong and was influential during the reigns of her mother and her elder brothers Emperor Zhongzong and Emperor Ruizong (both of whom reigned twice), particularly during Emperor Ruizong's second reign, when for three years until her death, she was the real power behind the throne.

She is the most famous and influential princess of the Tang dynasty and possibly in the whole history of China thanks to her power, ability and ambition. She was involved in political difficulties and developments during the reigns of her mother and brothers. Indeed, after the coup against Empress Dowager Wei, she became the real ruler of Tang. During the reign of Emperor Ruizong, she was not restricted by anything, the emperor issued rulings based on her views and the courtiers and the military flattered her and majority from every civil and military class joined her faction, so her power exceeded that of the emperor.

Eventually, however, a rivalry developed between her and her nephew, Emperor Ruizong's son, Crown Prince Li Longji. Both of them were hostile in power-sharing and they fought for the monopoly over power. After Emperor Ruizong yielded the throne to Li Longji (as Emperor Xuanzong) in 712, the conflict came to the political forefront, and openly, the court became a manifestation of conspiracy rather than the administration of the empire; in 713, Emperor Xuanzong, according to historical records, believing that she was planning to overthrow him, acted first, executing a large number of her powerful allies and forcing her to commit suicide.

------

The relationship between Shangguan Wan'er and Princess Taiping has always been written as "enemies" in official history, but with the phrase "千年万岁,椒花颂声", their friendship that has been buried for thousands of years was revealed.

The"千年万岁,椒花颂声" sentence comes from the epitaph written by Princess Taiping for Shangguan Wan'er. The original text is: "潇湘水断,宛委山倾,珠沉圆折,玉碎连城。甫瞻松槚,静听坟茔,千年万岁,椒花颂声”

Translation: Now that you are far away, the sky and the earth will lose their color. I'm afraid that all I can do in the future is to sit and look at the tea tree in front of your tomb. Maybe I can hear your voice again when I stand within an inch of the tomb. But this is a delusion after all, a quiet tomb, no beautiful face, a empty place of death. I hope that in a thousand or ten thousand years, there will still be people like me who remember you.

------

3.【Late Qing Dynasty】:Lü Bicheng(呂碧城) & Qiu Jin (秋瑾)

Lü Bicheng(呂碧城)also known as Alice Pichen Lee(1883–1943) was a Chinese writer, activist, newspaper editor, poet and school founder. She has been mentioned as one of the top four women in literature from the early Republic of China.

When she was four, her father retired to Lu'an, Anhui. She lived a life of comfort until the age of 12, when her father died in 1895. Because Lü Fengqi had no male heir, relatives of the Lü lineage contested for his inheritance, and Yan Shiyu and her four daughters were forced to move to Lai'an County to live with her natal family. When she was nine, Lü Bicheng was betrothed to a Wang family, but as her own family fortune declined, the Wang family broke off the marriage contract, giving the young Bicheng the stigma of a "rejected woman". The resulting emotional scar is often considered a major factor in her later decision to never marry.[8] Her widowed mother and the Lü girls were not well treated at the Yan family in rural Anhui. When Lü was 15 or 16, Yan Shiyu sent her to live with her maternal uncle Yan Langxuan (嚴朗軒), who was the salt administrator in Tanggu, the port city outside the northern metropolis of Tianjin. Her sister Huiru also joined her later.

During her stay in Tanggu, Qing China went through the tumultuous period of the failed Hundred Days' Reform of 1898, which brought about increasing awareness of women's education, and the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. In 1904, Mrs. Fang, the wife of her uncle's secretary, invited Lü Bicheng to visit a girls' school in Tianjin, but her uncle prevented her from going and severely reprimanded her. The next day, she ran away from her uncle's home, and took the train to Tianjin with no money or luggage. She wrote a letter to Mrs. Fang, who was staying at the dormitory of the Ta Kung Pao newspaper. Ying Lianzhi, the Catholic Manchu nobleman who founded the newspaper, read the letter and was so impressed by it that he made her an assistant editor. Lü Bicheng wrote a "progressive" ci that she had previously written, set to "A River Full of Red" ("Manjianghong") usually used to express heroic emotions. Ying transcribed the whole song in her diary and published it in L'impartial two days later. At the time, it was sensational for a woman to write for an influential national newspaper such as Ta Kung Pao. She was 21 years old. She used Ta Kung Pao to promote feminism and became a well-known figure.

Lü's ci poetry was published in the newspaper and it was very well received. She was the chief editor of the newspaper from 1904 to 1908. In 1904 she decided to improve education for girls. She had published her thoughts on women's rights and the general editor of the newspaper introduced her to Yan Fu who was an advocate for Western ideas. The Beiyang Women's Normal School was established that same year. At 23 Lü took on the job of principal of the school she had founded two years before. At first this school found it difficult to find girls who qualified for secondary education and students were brought in from Shanghai to make up the numbers.

Lü knew the revolutionary Qiu Jin and they had similar objectives but Lü did not join her in Japan when she was invited as she was unsure whether women should meddle in politics. She was then chosen to be secretary to Yuan Shikai, one of the most powerful people in China. When he set out to declare himself emperor of China she left, like many of his followers, and abandoned him.

--

Qiu Jin (秋瑾)8 November 1875 – 15 July 1907,was a Chinese revolutionary, feminist, and writer.Her sobriquet name is Jianhu Nüxia (Chinese: 鑑湖女俠 lit. 'Woman Knight of Mirror Lake').

Qiu was born into a wealthy family. Her grandfather worked in the Xiamen city government and was responsible for the city's defense. Zhejiang province was famous for female education, and Qiu Jin had support from her family when she was young to pursue her educational interests. Her father, Qiu Shounan, was a government official and her mother came from a distinguished literati-official family. Qiu Jin's wealthy and educated background, along with her early exposure to political ideologies were key factors in her transformation to becoming a female pioneer for the woman's liberation movement and the republican revolution in China.

In the early 1900s, Japan had started to experience western influences earlier than China. As to not fall behind, the Qing government sent many elites to learn from the Japanese. Qiu Jin was one of these elites that got the chance to study overseas. After studying in a women's school in Japan, Qiu returned to China to participate in a variety of revolutionary activities; and through her involvement with these activities, it became clear how Qiu wanted others to perceive her. Qiu called herself 'Female Knight-Errant of Jian Lake' — the role of the knight-errant, established in the Han dynasty, was a prototypically male figure known for swordsmanship, bravery, faithfulness, and self-sacrifice — and 'Vying for Heroism'

Qiu Jin had her feet bound and began writing poetry at an early age. With the support from her family, Qiu Jin also learned how to ride a horse, use a sword, and drink wine—activities that usually only men were permitted to learn at the time.In 1896 Qiu Jin got married. At the time she was only 21, which was considered late for a woman of that time. Qiu Jin's father arranged her marriage to Wang Tingchun, the youngest son of a wealthy merchant in Hunan province. Qiu Jin did not get along well with her husband, as her husband only cared about enjoying himself.While in an unhappy marriage, Qiu came into contact with new ideas. The failure of her marriage affected her decisions later on, including choosing to study in Japan.

While still in Tokyo, Qiu single-handedly edited a journal, Vernacular Journal (Baihua Bao). A number of issues were published using vernacular Chinese as a medium of revolutionary propaganda. In one issue, Qiu wrote A Respectful Proclamation to China's 200 Million Women Comrades, a manifesto within which she lamented the problems caused by bound feet and oppressive marriages. Having suffered from both ordeals herself, Qiu explained her experience in the manifesto and received an overwhelmingly sympathetic response from her readers. Also outlined in the manifesto was Qiu's belief that a better future for women lay under a Western-type government instead of the Qing government that was in power at the time. She joined forces with her cousin Xu Xilin and together they worked to unite many secret revolutionary societies to work together for the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

Between 1905 and 1907, Qiu Jin was also writing a novel called Stones of the Jingwei Bird in traditional ballad form, a type of literature often composed by women for women audiences. The novel describes the relationship between five wealthy women who decide to flee their families and the arranged marriages awaiting them in order to study and join revolutionary activities in Tokyo. Titles for the later uncompleted chapters suggest that the women will go on to talk about “education, manufacturing, military activities, speechmaking, and direct political action, eventually overthrowing the Qing dynasty and establishing a republic” — all of which were subject matters that Qiu either participated in or advocated for.

Life after returning to China

Qiu Jin was known as an eloquent orator who spoke out for women's rights, such as the freedom to marry, freedom of education, and abolishment of the practice of foot binding. In 1906 she founded China Women's News (Zhongguo nü bao), a radical women's journal with another female poet, Xu Zihua in Shanghai. They published only two issues before it was closed by the authorities. In 1907, she became head of the Datong school in Shaoxing, ostensibly a school for sport teachers, but really intended for the military training of revolutionaries[citation needed]. While teaching in Datong school, she kept secret connection with local underground organization—The Restoration Society. This organization aimed to overthrow the Manchu government and restore Chinese rule.

Death

In 1907, Xu Xilin, Qiu’s friend and the Datong school’s co-founder was executed for attempting to assassinate his Manchu superior. In the same year, the authorities arrested Qiu at the school for girls where she was the principal. She was tortured but refused to admit her involvement in the plot. Instead the authorities used her own writings as incrimination against her and, a few days later, she was publicly beheaded in her home village, Shanyin, at the age of 31. Her last written words, her death poem, uses the literal meaning of her name, Autumn Gem, to lament of the failed revolution that she would never see take place:

秋風秋雨愁煞人 (Autumn wind, autumn rain — they make one die of sorrow)

After Qiu Jin was killed, no one dared to collect her body. Lu Bicheng endured her grief and took great risks to bury her friend. The guarding Qing army learned that the woman who came to collect the corpse was Lu Bicheng, who was famous in China, and they had no choice but to do anything.

Qiu Jin's death caused Lu Bicheng to lose a rare confidant in life. She wrote many poems in memory of Qiu Jin, recalling this like-minded friend.

Later, Lü Bicheng wrote "The Biography of the Revolutionary Heroine Qiu Jin" in English, which was published in newspapers in New York, Chicago and other places in the United States. It caused a great response and not only made many people in the world know about Qiu Jin's legendary story, but also published it in newspapers in New York and Chicago. It also makes people understand the darkness and corrupt social status quo of the Qing Dynasty. Lu Bicheng used a pen of her own to record her friendship with Qiu Jin, and also fulfilled her promise to Qiu Jin to respond with the "battle of words"

————————

📸Video & 🧚🏻 Model:@荷里寒 & @阿时Ashi_

🔗Weibo:https://weibo.com/3618951560/NEZZnpQRq

————————

#chinese hanfu#china history#woman power#woman in history#hanfu#hanfu accessories#hanfu_challenge#chinese traditional clothing#china#chinese#han dynasty#tang dynasty#late qing dynasty#feminism#revolution#漢服#汉服#中華風#girl power#hanfu girl

403 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptian

Bastet

Between 664 and 610 BCE, Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt (664 BC-525 BC)

#egyptian art#bastet#egyptian cat#egyptian history#egyptian culture#ancient art#ancient artifacts#ancient people#ancient culture#catblr#cats of tumblr#cats in art#cat art#cat aesthetic#beautiful cats#beautiful animals#aesthetic#beauty#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr

883 notes

·

View notes

Text

A gold ring owned by a priest named Sienamun, ca. 664-525 BCE

The symbols spell out the name "sA-m-Imn": Sienamun.

Literal translation of the symbols comes out to "Son of (the god) Amun"

while the first two lines indicate he was a priest: "Hm-nTr" and a certified horse girl (i.e. a caretaker of horses): "imy-r smsmw"

#art#archaeology#ancient#egypt#ancient history#ancient egypt#gold#gold jewelry#bce#egyptology#ancient kemet#kemet#heiroglyphics#hieroglyphs#hieroglyphics

694 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lionness Headed Usekh, So Called "Aegis"

Egyptian, 1290-664 BCE (Late New Kingdom-Third Intermediate Period)

Silver was not easily obtainable in Egypt and was probably more costly for ancient Egyptians to acquire than gold.

#artifact#Egypt#new kingdom#third intermediate period#Aegis#lioness headed Usekh#pendant#embossed silver

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cat, 664–30 BCE, Ancient Egypt

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detail of a bronze statuette. The Goddess Bastet in Her form of sacred cat playing with her kitten. Date: c. 664-332 BCE.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nine-headed hermit": the early history of Zhong Kui (and his sister)

Gong Kai's painting Zhongshan Going on Excursion, showing Zhong Kui, his sister and various demons during a journey (wikimedia commons) Zhong Kui is probably one of the most recognizable figures from Chinese mythology today and continues to star in novels, movies and other works. However, his modern image largely depends on sources the Ming and Qing periods. In this article, I’ll attempt to instead shed some light on some lesser known aspects of his earlier history. You will be able to learn why he was called a “nine headed hermit” despite having only one head, what he had to do with foxes, when his sister was portrayed as an exorcist like him, and more. As a bonus, I’ve included a brief summary of Zhong Kui’s reception in medieval Japan.

The earliest history of Zhong Kui

Zhong Kui’s history goes all the way back to the Zhou period (most of the first millennium BCE). A homophone of his name (鍾馗), zhongkui (終葵; also zhongzui, 終椎) at the time referred to a type of ritual mallet used to expel demons. During the Six Dynasties period first cases of this term (now written as 鍾馗 ori 鍾葵) being used as a personal name start to pop up. The purpose was most likely to confer the protection granted by such objects to a child just through their name. Numerous cases are attested, and it doesn’t seem the bearers of the moniker Zhong Kui can be distinguished by a specific origin, social class or even gender. The earliest possible reference to a specific supernatural being named Zhong Kui comes from the Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing (太上洞淵神咒經; “Scripture of the Divine Incantations of the Abyssal Caverns of the Most High”), a Daoist work possibly composed as early as in the fourth century. The oldest surviving copy of the passage concerning Zhong Kui has been identified in a copy from Dunhuang dated to 664. He appears in it as an assistant of king Wu of Zhou and Confucius (sic) who helps them subjugate ghosts and disease demons. It is not impossible that to the compilers of Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing Zhong Kui was only a stand-in for an exorcist, though, not a single well defined figure. There’s an eyewitness account of such specialists dressing up in leopard skins, painting their faces red and announcing they are Zhong Kui in another, slightly newer Dunhuang text. It specifies that many Zhong Kui exist, and that they answer to the “General of Five Paths”, an originally apocryphal Buddhist figure eventually canonized as one of the kings of hell (you can find an excellent article about him here). In any case, regardless of the clear evidence for ambiguous use of the term in earlier times, it is agreed Zhong Kui became a well defined figure by the end of the Tang period. That’s also when legends about his origin started to circulate.

The legend of Zhong Kui

A typical depiction of Zhong Kui as a Tang period official by the Qing period artist Lü Xue (wikimedia commons)

According to the most popular version of Zhong Kui’s origin story, he was a scholar from the Zhongnan Mountains who lived during the reign of Gaozu of Tang (reigned 618-626). He took part either in the imperial examination or the imperial military examination (that’s an ahistorical detail - it was established by Wu Zetian in 702), but failed. This detail is not elaborated upon further in early accounts, but by the Ming period it was attributed not to lack of skill but rather to prejudice against Zhong Kui’s physical appearance (he is fairly consistently described as dark-skinned, unusually tall, with a bulbous head and excessive facial hair). It’s possible that this new backstory was based in part on experiences of real officials of foreign origin, whose appearance was sometimes mocked by their peers, as already documented in Tang sources. Another possibility is that the descriptions were meant to be exaggerated to the point of making him resemble a demon, though. Either way, out of despair caused by failure Zjong Kui committed suicide by smashing his head against the steps leading to the imperial palace. However, since in his final words he swore to protect the emperor and his realm, he didn’t return as a vengeful ghost, but rather as a queller of malevolent supernatural entities. Alternatively, he took this role out of gratitude for Gaozu, who was saddened by his death and organized the burial worthy of an honored official for him. Note that in later plays which often serve as the basis for modern adaptations, the burial is typically arranged by a certain Du Ping (杜平), a friend of Zhong Kui from back home. Apparently a version in which the kings of hell are so impressed by Zhong Kui that they decide to make him the king of the ghosts also exists, though I was unable to track down its original source. In any case, he is associated with Mount Fengdu - one of the terms referring to the realm of the dead - in a poem by Song Wu (宋无; 1260–1340) already. He, or at least generic clerk figures based on his iconography, also sometimes appear in Song period paintings of the Ten Kings.

Several Zhong Kui-like clerks from a depiction of hell in Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation (wikimedia commons)

According to Shih-shan Huang a single example of such a figure has even been identified in a Manichaean context, specifically in the scroll Sermon on Mani’s Teaching on Salvation.

Manichaean curiosities aside, supposedly the first person to be aided by Zhong Kui was emperor Xuanzong of Tang. At some point he fell gravely ill. In a dream, he saw a demon who attempted to steal a flute which was one of his most prized possessions. However, the attempt was foiled by a fearsome giant, who dealt with the thief rather brutally, poking out one of his eyes and then devouring him. After completing this act of demon quelling, he explained that he is Zhong Kui, and how he came to fulfill his current role. After waking up, Xuanzong felt healthy again. He was so impressed he commissioned Wu Daozi, arguably the most famous artist in China at the time, to prepare a painting of Zhong Kui which could be used as a talisman against any further supernatural issues. Supposedly it left quite the impression on the general populace, and soon numerous images of Zhong Kui started to be distributed as talismans. There is definitely a kernel of truth to this part of the legend, as eyewitness accounts of Wu Daozi’s painting exist, but the work itself is lost. As a side note, it’s worth pointing out the flute thief demon, despite meeting a gruesome end here, enjoyed a literary afterlife of his own. A certain Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳), the author of a colophon on one of the earliest surviving Zhong Kui paintings, suggests that the (in)famous rebel An Lushan might have been a reincarnation of this specific entity. While I am not aware of any other attempts at providing him with a backstory, in Ming period retellings of the legend, he received a name, Xu Hao (虛耗).

Zhong Kui’s later career

Zhong Kui’s popularity grew after the Tang period, and he arguably eclipsed figures such as the fangxiang (方相) or the baize (白沢) as the demon queller par excellence. Legends about his origin and his first notable act of demon quelling which I summarized above spread far and wide during the reign of the Song dynasty. After becoming a well defined figure, Zhong Kui came to be most commonly classified as a ghost (鬼; gui). In texts from the Song and Yuan periods he is often labeled more specifically as a “big ghost” (大鬼, dagui) or “ghost hero” (鬼雄, guixiong). However, his popularity effectively made him a god in popular imagination, and as a matter of fact he is referred to as such. His divinity is not exactly conventional, though. This topic is addressed in Fu Lu Shou Xianguan Qinghui 福祿壽仙官慶會 (The Immortal Officials of Happiness, Wealth and Longevity Gather in Celebration) by the Ming playwright Zhu Youdun (朱有燉; 1379-1435). Zhong Kui says himself that unlike his peers, he has no festival to call his own, and receives no regular offerings - and yet, he still vanquishes malicious entities on behalf of humans as long as talismans showing him continue to be distributed.

Interestingly, despite his long career in texts, no images of Zhong Kui older than the thirteenth century are known. This is mostly a matter of selective preservation, though - we know that depictions of him existed as early as in the ninth century, and that they were mass produced, presumably as woodblock prints, in the tenth. However, he didn’t necessarily look similar to his modern depictions. He actually only came to be depicted as a Tang scholar in the Song period. It seems earlier his costume might have varied. One thing which seemingly remained consistent when it comes to Zhong Kui’s appearance is his facial hair. This feature is even emphasized in many of his epithets, such as “Old Beard” (老髯, Lao Ran), “Bearded Elder” (髯翁, Ran Wong) or “Bearded Lord” (髯君, Ran Jun). It’s possible that this was initially a way to highlight his vitality and his opposition to disease-causing demons. Tang and Song sources indicate the state of facial hair could be viewed as an indicator of health. There’s even a handful of peculiar anecdotes about certain emperors, like Taizong of Tang or Renzong of Song, believing their facial hair has supernatural healing powers and offering ailing courtiers concoctions in which it was one of the ingredients. There’s no evidence Zhong Kui’s hair was ever believed to serve a similar purpose, though. Not all of Zhong Kui’s titles revolve around his beard, though. An interesting example is “Nine-Headed Hermit” (九首山人). The intent isn’t to imply he has nine heads, it’s a multilayered pun instead. The character 馗 in Zhong Kui’s name is a combination of 九, “nine”, and 首, “head”. Referring to him as a “hermit”, literally “man of the mountain”, is likely supposed to show that he traverses areas traditionally believed to be inhabited by demons.

The nine-headed snake Xiangliu (wikimedia commons)

Chun-Yi Tsai suggests that this title also highlights Zhong Kui’s physical prowess by implicitly evoking “a nine-headed serpent known for its tremendous strength in Guideways through Mountains and Seas” (presumably Xiangliu).

Zhong Kui’s strength lets him punish his enemies in various unexpectedly creative ways. The earliest sources already mention he could grind vanquished demons in a mill, for instance. References to eating them are particularly common. Depending on the source, Zhong Kui might simply devour them whole, hunt and prepare them like game animals, chop them up to pickle them, mince them to prepare meat snacks, squeeze them to make juice and wine, and so on. Such comedically gruesome descriptions are generally limited to textual sources, since violence was rarely depicted in other mediums, even in relation to military topics. Wu Daozi’s lost painting was apparently one of the exceptions, as according to a tenth century description it showed Zhong Kui gouging out the eyes of the captured demon.

Zhong Kui’s sister and other assistants

While Zhong Kui is often depicted in the company of nondescript demons, there are relatively few recurring figures associated with him. The main exception is his sister. The Song period painter Gong Kai (龔開) and his contemporary Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳) simply refer to her as Amei (阿妹), literally “younger sister”, though here it’s apparently a personal name, following Chun-yi Tsai’s interpretation. Her origin is unknown, and she is not present in any of the early variants of the legend.

Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (wikimedia commons)

Today Zhong Kui’s sister is known chiefly from works of art in various mediums which can be broadly subsumed under the label “Zhong Kui marrying off his sister” (鍾馗嫁妹, Zhong Kui jiamei) which proliferated through the Ming and Qing periods. This label is sometimes applied to earlier paintings too, for example Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (鍾馗嫁妹圖, Zhong Kui jiamei tu) is the conventional modern title of a scroll attributed to the poorly known painter Yan Geng (顏庚). A colophon from the Ming period describing this work calls the figure presumed to be Zhong Kui’s sister Ayi (阿姨; an informal way to refer a maternal aunt) as opposed to Amei. Chun-yi Tsai states it is not impossible that the woman is supposed to be Zhong Kui’s wife, rather than his sister, though. The painting can be dated to the Yuan period, and there is no evidence for the story of Zhong Kui marrying off his sister before the Ming plays - granted, it is not impossible that it was already in circulation earlier. Still, other paintings showing Zhong Kui marrying off his sister only date to the Qing period. Additionally, the procession might be a parody of paintings showing rural marriages or couples moving to a new house.

While as far as I am aware this eventually went out of fashion, in early sources Zhong Kui’s sister could be portrayed as an exorcist herself. An example can be found in one of the sermons of the Chan monk Yuanwu (圓悟; 1063–1135), in which he states that celebrations on the “Double Fifth” (端午節, duanwu jie) - the fifth day of the fifth month - involved a dance of “Zhong Kui and his little sister”. A reference to performers dressed up as the pair (as well as kings of hell, gods of soil and stove, various warrior deities and more) has alsobeen identified in an account of celebrations in Kaifeng from the end of the reign of the Northern Song dynasty.

Similar evidence can be found in art too. For example, Zheng Yuanyou (鄭元祐; 1292-1364) in a poem inspired by a painting titled Zhong Kui’s Sister (馗妹圖; as far as I am aware, this work has not been identified) states that she travels alongside her brother, that she’s armed with a sword, and that demons fear her. A related portrayal of her is known from a critical review of the works of Si Yizhen (姒頤真), a Song dynasty painter. According to Gong Kai, in one of his paintings she is shown in tattered (or unbuttoned - the term used, 披襟, can mean both) clothes, and chases away a boar attacking her brother. He was evidently not fond of this innovation, and criticizes it as “vulgar” and inappropriate. It needs to be stressed that Gong Kai’s displeasure wasn’t necessarily tied to presenting Zhong Kui’s sister as a demon queller, though. In fact, he is actually the author of the most famous work portraying her in this role.

Gong Kai's take on Zhong Kui's sister and her attendants (wikimedia commons; cropped for the ease of viewing)

Gong Kai depicted Amei in unusual black makeup, which is also worn by female demons accompanying her (note the one carrying a kitty!). This might be a parody of the sanbai (三白; “three whites”) face painting popular in the Song period. She and her attendants wear robes decorated with depictions of the “five poisons” (五毒), a term referring to animals perceived as particularly dangerous and inauspicious. The exact list varies, though centipedes, scorpions and snakes in particular are mainstays. The five poisons are directly associated with Zhong Kui, as he can be invoked to ward them off. Direct evidence first appears in the Qing period in accounts of the well known Dragon Boat Festival, but it’s not impossible this was an earlier development.

It is presumed that Gong Kai’s painting might depict Zhong Kui and Amei looking for a demonic version of Yang Guifei, as indicated by various hints in colophons. Her portrayals in art are quite diverse, but attributing demonic traits to her would be hardly unparalleled - she could even be described as a “palace demon” (宮妖, gong yao). The decline of the Tang dynasty was blamed on her, and metaphorically she might have been invoked to criticize other people believed to improperly use the power granted to them by the imperial court.

Gong Kai’s painting also depicts a less recurring member of Zhong Kui’s entourage. One of the demons carries a fox, specifically a nine-tailed specimen. The association between this animal and Zhong Kui goes all the way back to the early Tang period. In one of the Dunhuang manuscripts, the demon queller’s entourage includes a nine-tailed fox and a baize, who acted as bringers of good luck alongside him. It’s also worth pointing out that in another text from the same site, his mount during the hunt for a wangliang (魍魎; I will likely cover this entity a future article, stay tuned) is a “wild fox”. Chun-Yi Tsai attributes the inclusion of a nine-tailed fox among Zhong Kui’s servants as a “family pet” of sorts to the portrayals of this supernatural creature both as an apotropaic antidote to poison (including the five poisons) and as a demon in its own right. It would be a suitable member of Zhong Kui’s entourage both as a conquered malevolent being and as an amplifier for his exorcistic, protective power. A further possibility is that the association is the result of wordplay. A new year celebration involving a procession of people dressed up as members of Zhong Kui’s entourage, including his sister and various supernatural attendants, was known as dayehu (打夜胡). The homphony between 胡 and 狐, “fox”, might have resulted in the inclusion of the animal among the helpers.

Post scriptum: Zhong Kui in Japan

Zhong Kui, as depicted in Extermination of Evil (wikimedia commons)

Zhong Kui - or rather Shōki, following the Japanese reading of his name - probably reached Japan in the Insei period. Many other figures originating in China reached a considerable degree of popularity in Japan at roughly the same time - Taishan Fujun, Siming, Wudao Dashen, Pangu, Shennong, the examples keep piling up.

The oldest known Japanese depiction of Zhong Kui, which you can see above, is a painting from the twelfth century set known as Extermination of Evil. It might look a bit outlandish compared to most of the other depictions shown through this article, but I was able to locate a very close Chinese parallel:

A Yuan period depiction of Zhong Kui from the collection of the Beijing Library, via Richard von Glahn’s Sinister Way. Reproduced here for educational purposes only.

This is a Yuan period illustration said to be based on Wu Daozi’s painting. Zhong Kui doesn’t look like a Tang scholar yet, and the jacket and wide-brimmed hat are remarkably similar. It seems safe to assume that the Japanese painter was following a similar model - presumably one of the many now lost early depictions of Zhong Kui. Slightly antiquated iconography surviving far away from the core area associated with a specific figure would hardly be unparalleled - it has been recently suggested that the baize/hakutaku is a similar case, with Japanese depictions and descriptions matching Tang sources fairly closely, but missing the elements which developed in the Song period or later. For the most part, Zhong Kui fulfilled a similar role in Japan as in China: he was regarded as a fearsome demon queller, and images representing him were distributed for apotropaic purposes. However, it’s also important to note that there were certain innovations. He arrived in Japan at the brink of the middle ages - theologically speaking an era of unparalleled innovation, during which both native and imported figures were interpreted in unexpected ways, leading to the rise of a new ��medieval mythology”. Zhong Kui was hardly an exception from this trend. A “medieval myth” involving Zhong Kui is known from Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), an onmyōdō treatise traditionally attributed to Abe no Seimei, but most likely written by one of his descendants in the fourteenth century. Curiously, Zhong Kui’s name is written in it as 商貴 instead of the expected 鍾馗.

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

In the Hoki Naiden, Zhong Kui is still a queller of malevolent supernatural beings. However, instead of being a scorned scholar, he is a yaksha who became the ruler of Rājagṛha, a city in India. He is said to correspond to both the medieval Japanese deity Gozu Tennō (牛頭天王), and to his celestial “double” Tenkeisei (天刑星; from Chinese Tianxingxing), the “star of heavenly punishment” (I covered him here). They are said to be his manifestations respectively on earth and in heaven. This equation might seem random at first glance, but both of them actually had a lot in common with Zhong Kui: all three were believed to keep demons, especially those causing diseases, in check. Curiously, the reinterpretation of Zhong Kui as a yaksha turned king can also be found in the Genkō Shakusho (元亨釈書), a Kamakura period Buddhist history book. However, I am not aware of any studies examining it in more detail. I assume identifying him as a yaksha was a result of association with Gozu Tennō (I briefly discussed his yaksha credentials here), rather than the other way around, though.

While Hoki Naiden ultimately pertains more to medieval than modern religion, it’s worth noting that an unconventional take on Zhong Kui is still part of an extant tradition. Through history, Zhong Kui could be identified as a dōsojin (道祖神). This term denotes a class of deities meant to protect roads, crossroads and borders of villages. In parts of the Niigata prefecture this form of him is sometimes referred to as Shōki Daimyōjin (鍾馗大明神) today.

Bibliography

Joshua Capitanio, Epidemics and Plague in Premodern Chinese Buddhism

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Richard von Glahn, The Sinister Way: The Divine and the Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture

Shih-shan Susan Huang, Picturing the True Form. Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China

Wilt Idema & Stephen H. West, Zhong Kui at Work: A Complete Translation of The Immortal Officials Of Happiness, Wealth, and Longevity Gather in Celebration , by Zhu Youdun (1379–1439)

Chun-Yi Joyce Tsai, Imagining the Supernatural Grotesque: Paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the Late Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) Dynasties

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sending a hug to all mutuals.

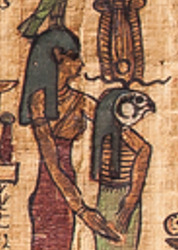

(Image: Excerpt of Papyrus Ryerson / OIM 9787, Book of the Dead, Egypt, Late Period, 664-332 BCE)

#now that it's cooled down again#it's time for hugs again#ancient Egypt#egyptology#i see the picture isn't looking too great on mobile but it looks fine on desktop :')

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pharaoh Psusennes I (r. c. 1047–1001 BCE)

The silver coffin of Psusennes I (r. c. 1047–1001 BCE) was discovered by Pierre Montet at Tanis. Psusennes I was one of the pharaohs of the 21st Dynasty, which ruled Lower Egypt from the city of Tanis. During this period, Egypt was politically divided, as the High Priests of Amun held power in the South. This division marked the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1077–664 BCE), a time when Egypt's influence had waned following the Golden Age of the New Kingdom.

Despite the political fragmentation, Psusennes’ sarcophagus showcases the continued sophistication of Egyptian craftsmanship. Unique to his burial is its location within the city walls of Tanis, diverging from the tradition of burying pharaohs outside cities on the west bank of the Nile. This change was likely a response to rampant tomb robbery, which rendered other sites unsafe. Additionally, the rule of the High Priests in the South complicated access to the traditional royal burial grounds, such as the Valley of the Kings. -O.G.

#ancient history#archaeology#art history#ancient egypt#egyptology#egyptian#classical literature#ancient art

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

source: bishopsbox

Ancient Egyptian black serpentine scarab, dated to 664-332 BCE

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptian

Cat with kitten

Late Period of ancient Egypt (664 BCE -332 BCE)

#egyptian art#ancient egypt#ancient art#ancient culture#egyptian history#egyptian culture#egyptian artifacts#egyptian aesthetic#aesthetic#cats in art#cats of tumblr#catblr#beautiful cats#beautiful animals#beauty#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr

215 notes

·

View notes