#26 April 1871

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

The establishment of the Alsace-Lorraine border, 1871-1877.

« L’invention d’une frontière », Benoît Vallot, CNRS, 2023

by cartesdhistoire

German nationalist intellectuals have clearly expressed since the beginning of the 19th century. the desire to withdraw from France the territories that they believe they recognize as German, due to the Germanic culture and language of the inhabitants, but also their prior belonging to the Holy Empire. The war against France which began on July 19, 1870 was therefore seen as an opportunity for a reconquest of territories ("Zurückeroberung").

The armistice was signed on January 26, 1871. The German chancellor, fearing an intervention by the European powers in favor of France, which had managed to attract the sympathy of international public opinion, downplayed the appetites of the Prussian general staff which demands all the territories placed under the authority of the general government of Alsace and Lorraine (administration of the territories occupied by the German army) as well as 6 billion gold francs in war compensation (a tribute in fact, because this amount represents much more than what the war cost the Germans). Bismarck therefore proposed to Thiers – and not the opposite as the latter would later claim – the conservation of Belfort for France and the reduction of compensation from 6 to 5 billion, in exchange for the abandonment of Metz, as compensation. (“Schmerzensgeld”).

The delimitation of the border between France and Germany is discussed based on a “green border” drawn on the map, without the populations being consulted, because the negative outcome is in no doubt for the Germans: the February 17, the deputies of Bas-Rhin, Haut-Rhin, Moselle, Meurthe and Vosges had in fact demonstrated their irrefutable opposition to any territorial cession to Germany through an official protest.

The definitive peace treaty was signed on May 10, 1871 in Frankfurt, then the concrete demarcation of the border lasted until April 1877: 14,521 km2 and more than a million and a half people thus changed sovereignty.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paris Commune, 1871.

Presentation of some social measures

The central committee of the National Guard, which had held power in Paris since March 18, 1871, encouraged voters to vote for a municipal assembly and to appoint "men who will serve you best" and who were "among you, living your own life, suffering from the same ills." After five months of siege, the Paris proletariat had "consumed more alcohol than bread" (P.H. Zaidman). Workers accustomed to living from day to day were not paid and did not expect to find work for a long time. A decree of February 15 restricted the allowance of 1.50 francs per day to only the National Guards who justified their lack of work. This pay was for most people their daily bread, and it was forbidden to take off their uniform (which was useful for their survival and that of their family). Craftsmen and merchants are pressed by the deadlines, the deadlines of which (which were increased by the government of September 4, but remained insufficient) are reduced by the Versailles Assembly (elected on February 8, 1871). Craftsmen and merchants are ruined by the cessation of transactions in the city deserted by those who were able to take refuge outside. All those who have no savings and who are without resources show concern for the payment of their rent. Small rentiers and liberal professions, just like the proletariat of Paris, are helpless and preoccupied by daily supplies.

The assembly of the Commune, elected on March 26, 1871, obliged to simultaneously fulfill the functions of government and municipality, composed of men with different political positions, subjected to different external pressures (clubs, district assemblies, circles of national guards), militarily assailed by the Versailles reaction, had very little time to pursue a social policy satisfactory to the majority of those who designated it.

First, it was a question of solving the problem of rents.

In September 1870, the government of National Defense had to find the means to continue the war. Since many republicans lived in the memory of 1789, in particular of the declaration of the fatherland in danger, they were inspired by it to help the destitute defenders. Thus was born the idea of exempting tenants from paying their rent for the duration of the conflict: this measure is called "moratorium of rents". The decree of September 30, 1870 granted a three-month period to tenants to pay their term due on October 1. As the siege of Paris and the protests continued, the decree was renewed on January 3, 1871. In November 1870, elections for the mayoralties of the twenty arrondissements, organized following popular demonstrations, had been won in nine of them by radical republicans. In the neighborhoods, committees composed of elected delegates were also formed. They formed a Republican Central Committee opposed to the government. A new period was thus granted to needy tenants.

For the Versailles Assembly, the measure threatened property and social order. The Versailles Assembly never stopped questioning these measures. At the beginning of March, the question of the April "term" began to arise. According to the Proudhonists, the very principle of paying rent was being called into question. For the defenders of social order, it was necessary to assert the right to property. On March 10, 1871, Thiers repealed the rent moratorium in place since September 1870. Parisian tenants, the majority in Paris, could not submit to this brutal decision.

After March 18, according to the majority of deputies, it was urgent to abolish the rent moratorium. In addition, other cities "threatened" to form revolutionary communes.

Discussions on the rent problem began on March 28, before the establishment of the nine commissions responsible for its management. The Labor, Industry and Trade Commission, as well as the Finance Commission, took charge of the rent issue. Eugène Varlin and Adolphe-Alphonse Assi presented a draft decree on rents; This is a matter of taking an emergency social measure (two days to prepare the decree)! However, Danielle Voldman points out that Varlin and Assi underestimated the difficulties of implementing the decree. In any case, the decree was adopted on March 30. "Considering that work, industry and commerce have borne all the burdens of the war, it is only fair that property should make its share of sacrifices to the country" (Journal Officiel, March 30, 1871).

Tenants were given the terms of October, January and April; any payments made were to be applied to debts falling due. Debts for furnished tenancies were forgiven, tenants were granted the right to terminate their leases for six months, or to protect the notice given for three months. The workers and petty bourgeois tenants were quick to make use of this decree; when the concierges opposed their departure, they moved out with the help of the National Guards. The sums already paid were considered as advances on future terms. The remission also applied to small furnished dwellings (the “garnis”). When leases were terminated, the tenants’ voice took precedence over those of the owners. Finally, tenants who were dismissed could stay for six more months. From the point of view of the working classes, this was the assurance of not finding themselves on the street for several months. Thiers tried to respond to the decree. Of course, the main thing for Thiers was to maintain "social peace"! Most of the deputies refused to let the owners lose their income. A few argued for an "appeasement law". Since the district town halls could not cope with the influx of requests for help, the Commune proposed to requisition the apartments abandoned since March 18 by those who had fled Paris. These requisitions were to be made with an inventory of the premises and a copy to the representatives of the absent owners. It is possible that the requisitions were blown out of proportion by some dispossessed owners, and that the lack of documentation concerning these requisitions reveals their small extent more than the destruction of the archives in the fire at the Hôtel de Ville.

Concerning the question of deadlines, from April 1, the Commune encouraged workers' societies and trade unions to send it all the necessary information. Charles Beslay, elected to the Council of the Commune, presented his project (published in the Official Journal). After serious discussions, a decree of April 12 provided for the suspension of proceedings until the publication of the decree on this question. The repayment of debts (of all kinds) falling due should have been made within the following three years (unfortunately, this did not happen as planned!).

The arbitration commissions, composed of two tenants and two owners chosen by the judge, could grant debtors a period of two years to pay the rent arrears without interest as well as a spreading of the debt, over the year by twelfths. After two years, a period was still possible, this time with 5% interest. The tenant had to prove that the "events" occurring between September and May had prevented him from paying his rent and that he was "in good faith". The arbitration commissions continued the work of the municipal commissions and took over the procedures initiated since the winter with the justices of the peace by owners contesting the validity of their tenants’ requests. Until May 28, 1871, the functioning of these commissions was slow; the owners waited to see how the situation would evolve, not caring about appearing to be members of the “starving” party. On the other hand, at the beginning of May, mention was found of the first requests from tenants. At the end of the Bloody Week, the requests exploded.

It must be admitted that these measures were not enough to get the people of Paris out of the precarious situation in which they found themselves...

On March 29, a decree, proposed by Augustin Avrial (at the Commission of Labor and Exchange), suspended the sale of the deposited objects, but this proved insufficient. The debates never ended! On May 3, Arthur Arnould insisted on continuing the discussion launched by Augustin Avrial. On May 6, François Jourde (Finance Commission) voted on a project which, while compensating the administration of the Mont-de-Piété, authorized the free withdrawal, from May 12, of all recognitions prior to April 25 that carried a commitment of up to 20 francs (clothing, linen, furniture, work instruments, etc.). Since the operation was to involve at least 1,800,000 items, these items were divided into 48 series to be drawn at random. This policy of "relief" should have been supplemented by the use of public resources, such as public assistance (but which was disorganized and deserted by almost all of the employees who came out of it).

At an extraordinary council of hospitals held on March 20, the Parisian administration of the Assistance publique decided to continue to exercise its functions despite the events of March 18. On March 22, the Director was forced to leave Paris, soon followed by the division heads, which led to profound disorganization. Appointed head of the Assistance publique on March 26, Camille Treillard set about making the institution function as best he could, under the control of the Central Committee of the twenty arrondissements, then under the control of Gustave Tridon, charged by the Commune with following this file. In early April, the influx of wounded implied the need to increase the number of hospital beds. The Assistance publique had to face the innumerable problems posed by the necessary reorganization. Their professional ethics pushed most of the doctors to remain at their posts, while they were generally indifferent or hostile to the Commune. The same thing happened to the 2,350 lay staff members, who were generally better disposed towards the fédérés. Camille Treillard, a deeply honest and scrupulous man, was concerned above all with ensuring the proper functioning of the public hospital system, specifying the priorities: "The political spirit must be banished from the hospital, to allow only the spirit of devotion and solidarity to reign". Treillard did his best to resolve the problems of supplies, the provision of bandages, and also to resolve the problems of financing (the "treasure" of the Assistance publique had been put in a safe place by the Versailles troops). Despite the relative isolation in which each hospital was forced to operate, the health system managed to fulfill its mission in a generally satisfactory manner thanks to its staff. Camille Treillard was able to face the dramatic situation resulting from the Semaine sanglante with courage, and refused to hand over the wounded fédérés to the Versailles troops. During the Bloody Week, the Versailles troops did not hesitate to shoot several doctors.

Two commissions have a significant impact on the economic and social life of the people of Paris, and reveal, through their actions, all that the Commune contains of socialist.

The Subsistence Commission, led by François Parisel and then Auguste Viard, aimed to ensure the supply of Paris and the lowering of prices, compromised by certain unscrupulous officials (such as the inspector of markets and halls who hid part of the flour stock). From April 25, the exit of transit goods was authorized, except for foodstuffs and munitions. The Prussian blockade, the suppression of correspondence with the departments, the ban on water convoys decided by Versailles, did not prevent the supply of the market by the neutral zone, and prices were falling (except for the price of meat). On April 30, salt was offered to bakers, for humanitarian purposes. The Subsistence Commission decided to purchase foodstuffs to sell them at cost price through establishments placed under the guarantee of the municipalities. From May 6, the Commission checked the flow of meat at the free butcher's market of Les Halles and in the butcher's shops of Montmartre.

The Commission of Labor, Industry and Exchanges: First under the impetus of an initiative commission established on April 5, then under the impetus of Léo Frankel, the Commission of Labor, Industry and Exchanges, obviously intended to respond to the satisfaction of workers' interests. A decree of April 16 asked the workers' union chambers to set up a commission of inquiry that would serve to draw up statistics on abandoned workshops and an inventory of work tools, to present a report on the practical conditions for quickly putting these workshops back into operation by the cooperative association of workers and employees, to draw up a draft constitution of these workers' cooperative societies. The decree also provided for the payment of compensation to be paid to the employers upon their return. A room was made available to the union chambers at the Ministry of Public Works and the unions began to work by appointing their delegates. The commission of inquiry held two sessions on May 10 and 18, but could only limit itself to preliminary studies, the Versailles repression not allowing it to go further...

Thanks to Léo Frankel, the Executive Commission banned night work for bakery workers (April 20). The decree was gratefully received by the bakery workers who demonstrated in its favor on May 16. A more general measure was taken on April 27, prohibiting fines and deductions from wages in public and private administrations and restoring those that had been deducted since March 18. A special circumstance forced the Commune to go further. On May 4, Edmond Evette and Lazare Lévy were tasked with monitoring the production of military clothing. Their report noted that the auction price had led to a drop in wages. The Commune paid 2.5% less for its supplies than the government of September 4. Léo Frankel and Benoît Malon concluded that it was necessary to resort to workers' corporations. On May 12, the Commission of Labor, Industry and Trade was authorized to revise the contracts concluded to date, to give preference to workers' associations, according to specifications determined by the intendance, the union chambers and a delegate of the Commission, and set the minimum wage for work by the day or in its own way. On May 14, François Parisel, head of the scientific delegation, called on unemployed workers to work on paper. Léo Frankel, for his part, wanted to limit the working day to eight hours; however, several workshop regulations set it at ten hours. In these workshops, the director, the workshop manager and the bench managers were appointed by the workers who had daily means of action on management.

Despite the decrease in the number of employed workers (which went from 600,000 in 1870 to 114,000), the war, and the economic situation, union and corporate life managed to develop.

From March 23, the trade union chamber of stone cutters and sawyers decided to organize relief in the event of injuries or accidents. On April 27, the tallow smelters and iron smelters joined together to form a trade union chamber and a cooperative association. The butcher workers wanted to organize a trade union chamber that would be necessary to eliminate employer exploitation. It should be noted that historians list the action of 43 production associations, 34 trade union chambers, 7 food companies and 4 groups of the Marmite (food cooperative founded in 1868 by Eugène Varlin and attached to the International).

The women workers also tried to follow the action undertaken by their male comrades. The Central Committee of the Union of Women for the Defense of Paris and the Care of the Wounded, charged by the Labor, Industry and Trade Commission with the organization of women's work, convenes (on May 10) a meeting at the Bourse to appoint delegates in each corporation. It is also a question of forming union chambers, cooperative workshops, and a federal chamber. Another meeting was planned (on May 21) to set up chambers, but it never took place...

Overall, during these 72 days, the Commune could have done more in the social domain, to satisfy all those who brought it to power and who hoped to see social improvements. Nevertheless, one must take into account the political divisions (neo-Jacobins, Blanquists, auto-authoritarians), with the heavy task of governmental and municipal reorganization to assume. Thus, the Commune had to bear the weight of a two-month war against the Versailles army. It must be acknowledged that the Commune outlined what a truly socialist policy would be, which it would be up to future generations to implement...

Sources :

Michel Cordillot, Danielle Voldman, Pierre-Henri Zaidman - La Commune de 1871 : Les acteurs, l'événement, les lieux Laure Godineau - La Commune de Paris par ceux qui l'ont vécue Jacques Rougerie, La Commune de Paris Jacques Rougerie, Paris libre 1871

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … December 26

1716 – Thomas Gray, the English writer, was born on this date (d.1771). "My life is now but a perpetual conversation with your shadow - The known sound of your voice still rings in my ears. I cannot bear this place, where I have spend many tedious years within less than a month, after you left me ..." So wrote Thomas Gray to a young man when he was 54. Professor of Modern History at Cambridge University and one of the best known poets of his time. He was also more than likely still a virgin, although he may have had a homosexual affair with Horace Walpole when he was younger.

The author of "An Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard," Gray had lived most of his life with his mother, but was known to have cultivated the Platonic friendship of handsome young men. One of Professor Gray's young men introduced him to the Swiss charmer, Charles de Bonstetten – and Gray was hooked. He was profoundly, deeply in love. When Bonstetten left Cambridge a year later, the poet was devastated. But the friends exchanged letters, and the young man suggested they take a walking tour together in Bonstetten's native Switzerland. Gray was overjoyed. The trip was scheduled for the summer of 1771 and Gray wrote tireless letters of devotion while counting the ticking minutes. Finally, the time was near. He would be leaving to see his handsome young man again. The poor poet dropped dead before he had taken one step out the door.

1795 – William Drummond Stewart (d.1871) was a Scottish adventurer and British military officer and homosexual. He traveled extensively in the American West for nearly seven years in the 1830s. In 1837 he took along the American artist, Alfred Jacob Miller, hiring him to do sketches of the trip. Many of his completed oil paintings of American Indian life and the Rocky Mountains originally hung in Murthly Castle, though they have now been dispersed to a number of private and public collections.

Born at Murthly Castle, Perthshire, Scotland, Stewart was the second son and one of seven children of Sir George Stewart, 17th Laird of Grandtully, 5th Baronet of Murthly and of Blair. The family decided that William would go into the Army (as his older brother would inherit his father's estate and title). After his seventeenth birthday in 1812, William asked his father to buy him a cornetcy in the 6th Dragoon Guards. After his appointment was confirmed on April 15, 1813, he immediately joined his regiment and began a programme of rigorous training.

Stewart was anxious to participate in military action; so in 1813, his father purchased for him an appointment to a Lieutenancy in the 15th King's Hussars, which was already in action during the Peninsular Campaign. In 1814, Stewart joined his regiment, subsequently seeing combat during the Waterloo campaign in 1815. In 1820, Stewart was promoted to a Captain and soon thereafter retired on half pay.

Seeking adventure, Stewart traveled to St. Louis, Missouri in 1832, where he brought letters of introduction to William Clark, Pierre Chouteau, Jr.,William Ashley and other prominent residents. He arranged to accompany Robert Campbell, who was taking a pack train to the 1833 rendezvous of mountain men, an annual all-male gathering of fur traders, a drunken debauch held each summer when trappers gathered to trade their pelts for food, liquor and manufactured goods brought to the Rockies from St. Louis by companies of fur traders.

The party left St. Louis on May 7 and attended the Horse Creek Rendezvous in the Green River Valley of Wyoming. Here Stewart met the mountain men Jim Bridger and Thomas Fitzpatrick, as well as Benjamin Bonneville, who was leading a governmental expedition in the area.

At the rendezvous Stewart met the Metis (French Canadian and Cree) hunter Antoine Clement, with whom he began a homosexual relationship. With some of the men, Stewart visited the Big Horn Mountains, wintered at Taos, and attended the next rendezvous at Ham's Fork of the Green River. Later that year, he journeyed to Fort Vancouver, Washington, at the coast of the Pacific Ocean.

Stewart attended the 1835 rendezvous at the mouth of New Fork River on the Green and reached St. Louis in November. Finding that his finances were curtailed because he brother had failed to forward his share of the estate left by their father, Stewart went to New Orleans, speculated in cotton to recoup, and wintered in Cuba.

In May, he joined Fitzpatrick's train to the Rockies for another rendezvous on Horse Creek. For the rendezvous of 1837, Stewart took along an American artist, Alfred Jacob Miller, whom he hired in New Orleans. Miller painted a notable series of works on the mountain men, the rendezvous, American Indians, and Rocky Mountain scenes. He wintered in 1836-1837 and 1837-38 at New Orleans, where he speculated again in cotton. In 1838 he learned that his childless older brother John had died of an undisclosed disease (probably cancer). William Stewart would become the seventh baronet of Murthly.

"Attack by Crow Indians" Alfred Jacob Miller

After his older brother John Stewart died childless in 1838, William inherited the baronetcy and returned to Scotland, taking with him his partner Antoine Clement, and the couple lived in Dalpowie Lodge, while entertaining in Murthly Castle. Stewart explained Clement's presence by at first referring to him as his valet, then as his footman. Because Clement was restless and unhappy in Scotland, the couple spent many months traveling abroad, including an extended visit to the Middle East.

In 1842 he returned to America, and in the summer of 1843 hosted a private rendezvous-style party at a remote lake in the Rockies (now called Fremont Lake). On that trip Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, the son of Sacagawea of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was hired to care for the mules.

Stewart returned to North America in late 1842, and in the September of 1843 he and a large entourage traveled to what is now Fremont Lake. Stewart brought with him a large array of velvet and silk Renaissance costumes for his all-male guests to wear during the festivities. He hauled wagon loads of canned delicacies, cigars, liqueurs and champagne. Fur trader William Sublette co-hosted the party with Stewart. Though there had been no rendezvous since 1840, the party had many elements of the old Rocky Mountain gatherings. Stewart had planned to spend the winter of 1843-44 in New Orleans, and visit Taos and Santa Fe the following spring, but the Renaissance "pleasure trip" ended in a dispute that split the party and caused Stewart to return to Scotland earlier than he had planned, never to return to the United States.

In 1856 Stewart's American friend Ebenezer Nichols, his wife, and three sons, visited from Texas. When it came time to leave Scotland, the Nichols's middle son, Franc, declined to return home. He instead stayed on with William Drummond Stewart at Murthly Castle, possibly in a sexual relationship, eventually being adopted by Stewart and becoming his primary heir.

Stewart died of pneumonia on April 28, 1871.

Stewart wrote two autobiographical novels based on his experiences in America, Altowan (1846) and Edward Warren (1854). Both novels include surprisingly frank homoerotic scenes.

1931 – Martin Gouterman (d.2020) was one of the foundational figures of modern porphyrin science. After completing his Ph.D. at The University of Chicago in 1958, he joined Harvard, where he developed his eponymous four-orbital model.

In 1966, he moved to the University of Washington Seattle (UW). Here he came out as gay and helped set up Seattle's first gay rights group, the Dorian Society.

At UW, Gouterman accomplished an “optical taxonomy” of the major classes of porphyrin derivatives and pioneered pressure-sensitive paints based on phosphorescent platinum porphyrins to map the partial pressure of oxygen on airplane wings. Revered by his students and co-workers for his brilliant yet gentle advising, Gouterman remains a beacon for a more humane and inclusive scientific enterprise.

In the early 1980s, Gouterman acted as a sperm donor and helped a lesbian couple have a son.Through mutual acquaintances, he discovered the identity of his son and thereafter enjoyed a close relationship with him.

1933 – On this date the Gay classic film Queen Christina was released and starred Greta Garbo in the lead role. The American pre-code historical drama film was directed by Rouben Mamoulian and written by H. M. Harwood and Salka Viertel and based on a story by Salka Viertel and Margaret P. Levino.

The movie is very loosely based on the life of the 17th century Queen Christina of Sweden, who, in the film, falls in love during her reign but has to deal with the political realities of her society. It was billed as Garbo's return to cinema after an eighteen-month hiatus.

1971 – Jared Leto is an American actor, singer, songwriter, and director. After starting his career with television appearances in the early 1990s, Leto achieved recognition for his role as Jordan Catalano on the television series My So-Called Life (1994).

He made his film debut in How to Make an American Quilt (1995) and received first notable critical praise for his performance in Prefontaine (1997). Leto played supporting roles in The Thin Red Line (1998), Fight Club (1998) and American Psycho (2000), as well as the lead role in Urban Legend (1998), and earned critical acclaim after portraying heroin addict Harry Goldfarb in Requiem for a Dream (2000).

He later began focusing increasingly on his music career. Leto is the lead vocalist, multi-instrumentalist and main songwriter for Thirty Seconds to Mars, a band he formed in 1998 in Los Angeles, California, with his older brother Shannon Leto. Their debut album, 30 Seconds to Mars (2002), was released to positive reviews but only to limited success. The band achieved worldwide fame with the release of their second album A Beautiful Lie (2005). The band has sold over 15 million albums worldwide. Leto has also directed music videos, including the MTV Video Music Award–winning "The Kill" (2006), "Kings and Queens" (2009), and "Up in the Air" (2013).

Leto's performance as a transgender woman in Dallas Buyers Club (2013) earned him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, among numerous other accolades. Leto is considered to be a method actor, known for his constant devotion to and research of his roles. He often remains completely in character for the duration of the shooting schedules of his films, even to the point of adversely affecting his health.

Leto is a gay rights activist. In October 2009, he raised money to the campaign against California Proposition 8, created by opponents of same-sex marriage to overturn the California Supreme Court decision that had legalized same-sex marriage. He spoke out in support of LGBT rights group Freedom Action Inclusion Rights (FAIR). In May 2012, he expressed support after hearing that Barack Obama had endorsed same-sex marriage.

Although Leto presents himself as straight in real life, Alexis Arquette - the transgender sister of David Arquette - claimed "I had sex with Jared Leto back when I was presenting as a male," Alexis stated. "And yes, it's not only massive, it's like a Praetorian Guard's helmet."

You can watch him grab and flaunt this "massive" chunk of meat at a 30 Seconds to Mars concert performance in Toronto in 2014 in the gif clip below.

censored by small pricks Tumblr

1973 – Reichen Lehmkuhl, (born Richard Allen Lehmkuhl) is an American former reality show winner, model, and occasional actor. A former United States Air Force officer, he is best known for winning season four of the reality game show The Amazing Race with his then-partner Chip Arndt, and for his much publicized 2006 relationship with pop singer Lance Bass.

After Lehmkuhl's parents, a policeman and a nurse, divorced when he was five, his family moved to Norton, Massachusetts, and his mother remarried. Sometime after 2002, he changed his first name legally from Richard to Reichen. Lehmkuhl graduated from the United States Air Force Academy. He has since advocated for gay rights in the military as a spokesperson for Servicemembers Legal Defense Network.

Lehmkuhl was working simultaneously as a physics teacher at Crossroads School for the Arts and Sciences, flight instructor and model in Los Angeles when he was approached by a casting director for The Amazing Race. Lehmkuhl and Chip Arndt were a couple during the competition but have since split. Lehmkuhl moved to Dallas, Texas briefly after his win on The Amazing Race but before all episodes had been broadcast. Reichen's spending habits at that time caused speculation that he had won The Amazing Race — and that he and Arndt had broken up. During the show, the couple was typically described as "Married" in the subtitles that are used to illustrate the relationship between team members (other teams being, for example, "Best Friends" or "Father-Daughter").

Lehmkuhl hosted The Reichen Show on Q Television Network until Q Television ceased operations in May 2006. His autobiography Here's What We'll Say, about his time in the Air Force under the military's commonly called "Don't ask, don't tell" policy, was released by Carroll and Graf on October 28, 2006. The New York Post reported in November 2010 that the book had been adapted into a screenplay. He published a beefcake calendar for several years and has appeared on sitcoms, soap operas, and other reality television shows.

On July 2006, former 'N Sync band member Lance Bass told People Magazine that he is gay and in a "very stable relationship" with Lehmkuhl. The couple broke up in January 2007. Bass said they remained "good friends".

On May 1, 2007, the LGBT-interest television network here! announced that Lehmkuhl had joined the cast for the third season of its original gothic soap opera, Dante's Cove. He plays the role of Trevor, originally described as "a business school graduate who comes to Dante's Cove looking to find himself."

Lehmkuhl also has a jewelry line called Flying Naked composed of flight-themed jewelry made of titanium steel. Items from the collection are being sold from loveandpride.com. A percentage of each sale goes to the Servicemembers Legal Defense Network.

Lehmkuhl starred in My Big Gay Italian Wedding, an off-Broadway production from its opening May 5, 2010 in New York City to July 24, 2010. A percentage of ticket sales promoted legalization of same-sex marriages in the US through Broadway Impact.

LGBT-interest network Logo announced on June 3, 2010, that Lehmkuhl and boyfriend, model Rodiney Santiago had joined the cast of Logo's reality series, The A-List: New York. The low-rated series, frequently described as a "Real Housewives"-style show, was cancelled after two seasons. Since the airing, Lehmkuhl and Santiago are no longer a couple.

1974 –Joshua John Miller is an American actor, screenwriter, author, and director. Miller co-writes with his life partner M.A. Fortin; the two wrote the screenplay for the 2015 horror comedy The Final Girls, and the USA Network drama series Queen of the South.

Miller was born in Los Angeles to actor and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Jason Miller and actress and Playboy pin-up Susan Bernard. Miller's half-brother is actor Jason Patric, and his maternal grandfather was photographer Bruno Bernard, also known as "Bernard of Hollywood". His father was of Irish and German descent, and his mother is Jewish. Miller is openly gay and, as of 2013, is in a relationship with fellow screenwriter M.A. Fortin.

Miller began appearing in films and television when he was eight years old. His first film role was in Halloween III: Season of the Witch. He would go on to star in such films as River's Edge, Near Dark, Class of 1999, and Teen Witch. Miller also made guest appearances on several popular television shows, including 21 Jump Street, The Wonder Years, The Greatest American Hero, Highway to Heaven (for which he received a Young Artist Award in 1985), and Growing Pains (hence a popular misconception that he is a relative of Jeremy Miller, who portrayed Ben Seaver on that series; they are not related). Miller appeared in several plays, and was involved in dance from a very early age. He starred in the Los Angeles Ballet Company's production of The Nutcracker for three consecutive seasons beginning at age seven, and later appeared as a dancer in Janet Jackson's Grammy Award-winning Rhythm Nation 1814 video.

In 1997, he published a pseudo-autobiographical novel called The Mao Game about a fifteen-year-old child star attempting to cope with heroin addiction, memories of past sexual abuse, and the impending death of his grandmother, who has been diagnosed with cancer. In 1999, The Mao Game was adapted into a film, written and directed by Miller, and co-produced by Whoopi Goldberg. The film starred Miller, Kirstie Alley, and Piper Laurie, and featured Miller's mother, Susan Bernard, in a brief, uncredited cameo. It toured the festival circuit, and garnered mixed reviews from critics.

In 2007, Miller appeared as Jinky in The Wizard of Gore. He has written a second novel, titled Ash.Miller collaborated with M.A. Fortin to write the DreamWorks TV and Fox production Howl. Miller and Fortin then co-wrote the short film Dawn (2014), which was directed by actress Rose McGowan and premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. The two also co-wrote the screenplay and executive produced the 2015 horror comedy film The Final Girls, directed by Todd Strauss-Schulson and starring Taissa Farmiga and Malin Åkerman. Miller and Fortin wrote the pilot for the USA Network drama series Queen of the South. Miller also serves as an executive producer for the series, which began airing on June 23, 2016.

1995 – Conner Mertens is an American football placekicker for the Willamette Bearcats. He was the first active college football player to publicly come out about his sexuality; he came out as bisexual.

Mertens grew up in Kennewick in Tri-Cities, Washington, where he was the youngest of four boys in his family. Growing up, he always excelled at sports. He concentrated on athletics after an incident in fifth grade in which classmates teased him for remaining in costume and makeup after a drama competition.

According to Mertens, the environment at Southridge High School was "hostile", as he was surround by a culture of homophobia. He said the Tri-Cities was not the most friendly area toward the LGBT community. In 2012, 63 percent of the area voted against a measure for same-sex marriage that was ultimately approved by the state. Starting with his sophomore year in high school, Mertens was active in Young Life, a national organization that preaches Christianity to youth. After being in trouble in his freshman year, he credited Young Life with turning his life around.

Mertens redshirted and did not play football in his freshman year due to an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury to his left knee from playing soccer. In January 2014, Mertens came out as bisexual, the first active college football player at any level to publicly come out. With his announcement, he was banned from working with Young Life, which he had been certain would be a part of the rest of his life; the organization's "Faith and Conduct Policies" did not allow any LGBT person to be a staff member or volunteer, though they could participate as "recipients of ministry of God's grace and mercy as expressed in Jesus Christ."

He became Willamette's kicker in 2014, when he also received limited opportunities as a punter. In his senior year, Mertens was named the placekicker on the Tri-City Herald All-Area second team. He was also a four-year starter on Southridge's soccer team. Conner is also a member of the Sigma Chi Fraternity.

Mertens is featured in Out to Win, a documentary about LGBT participation in American sports.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosopher's Flight and The Philosopher's War Timeline

Tom Miller clearly planned these two novels stupendously, and I found myself wanting to put everything together in order so I could follow the timeline the way he intended. Hope someone else finds this helpful!

1750: Sigilry comes into widespread use 1831: Cadwallader invents smoke carving 1857: Transporter sigil first comes into use 1861: Wainwright starts Legion of Confederate Smokecarvers April 6, 1865: Petersburg massacre 1865: Birth-control sigils are published 1870: Franco-Prussion war begins 1871: Cadwallader’s Siggilrists break the Korps des Philosoph beseiging Paris 1891: Chilean Civil War - Beau Canderelli is a military philosopher 1892: Maxewell Gannet alludes to his list of 200 sigilrists 1897: Beau Canderelli and Emmaline Weekes meet in Havana January 1899: Robert is born 1901: Second Disturbance - Emmaline Weekes and Beau Canderelli guerrilla fight the trenchers November 1901: Beau Canderelli dies of a gunshot 1902: Hatcher and Jimenez make the first Transatlantic Flight hovering back-to-back 1914: The Great War breaks out February 1916: Gallipoli; Danielle Hardin evacuates most of the Commonwealth army solo 1916: Corruption discovered in 1st Division of R&E by Blandings; Gen. Rhodes creates 5th division for Blandings before Rhodes is fired April 6, 1917: Philosopher’s Flight begins August 1917: Edith Rubinsky (Edie or Ruby) gets her legs ruined January 1918: Robert gets his sigil fixed January 1918: Robert places 3rd in the Long Course of the General’s Cup May? 1918: Danielle becomes aide to Sen. Cadawaller-Fulton July 1918: Robert goes to Europe as part of R&E Early October 1918: Drale dies, Punnet dies in Battle of Saint-Mihiel Late October 1918: Robert breaks 1000 evacuations October 30th, 1918: the mutiny begins; Germans attack Metz and head towards Paris with their plague smoke October 31st, 1918: Robert picks up Bertie Synge and gets trapped under German cloud of smoke November 1st, 2pm, 1918: Edie finds Robert and Bertie November 2nd, 1918: Robert and co. end the war by transporting Berlin January? 1919: Robert ties 1st with Dmitri in the endurance flight February? 1919: General Pershing decimates the Corps, renames it the Army Philosophical Service; Essie stays on and rises through the ranks March 1919: Thomasina Blandings is court-martialed, subsequently gets sentenced to 10 years imprisonment at Ft Leavenworth Christmas 1919: First Zoning law passed January? 1920: Robert ties 1st with Michael Nakamura March? 1920: limits on hoverers license passed; Robert is living in Massachusetts January? 1921: Robert places 1st in Endurance flight 1922: Assuming she held to her timeline, Danielle Hardin runs and wins the Representative seat in Rhode Island 1926: Second Zoning Act - Danielle Hardin campaigns against December 26, 2926: Danielle Hardin writes to Robert 1930: Robert and (presumably) Edie’s daughter is born January 1932: Pilar Desoto orbits earth, Robert powers her 3rd-stage booster 1939: Preface to Flight, Robert is exiled in Mexico and is Field Commander for the Free North American Cavalry (at some point lbefore this, Freddy Unger starts teaching at the Universidad de Tamaulipas, Essie is promoted to Major General of the US Army Philosophical Service, Edie becomes a doctor of Neurology at Matamoros General Hospital) 1941: Danielle Hardin is/was Secretary of Philosophy to Franklin D Roosevelt November 11, 1941: Preface to War, Robert is promoted to Commander and Brig. General of First North American Volunteer Air Cavalry, and is in China due to personal request from Roosevelt (in exchange for amnesty for sigilrists in exile from United Stages)

#the philosopher's flight#the philosopher's war#tom miller#timeline#alternate history#sigilry#books#books you should read#my writing

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐇𝐚𝐣𝐢𝐦𝐞 𝐈𝐬𝐨𝐠𝐚𝐢 : 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝐍𝐞 𝐖𝐚𝐳𝐚

Hajime Isogai was an early student of judo and the second person to be promoted to 10th dan. He was considered to be a newaza expert, although was also famed by his tachiwaza as well. He was an early promoter of the kosen judo circuit.

Born: October 26, 1871, Miyazaki, Japan

Died: April 19, 1947

.

Picture : Hajime Isogai (tori)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

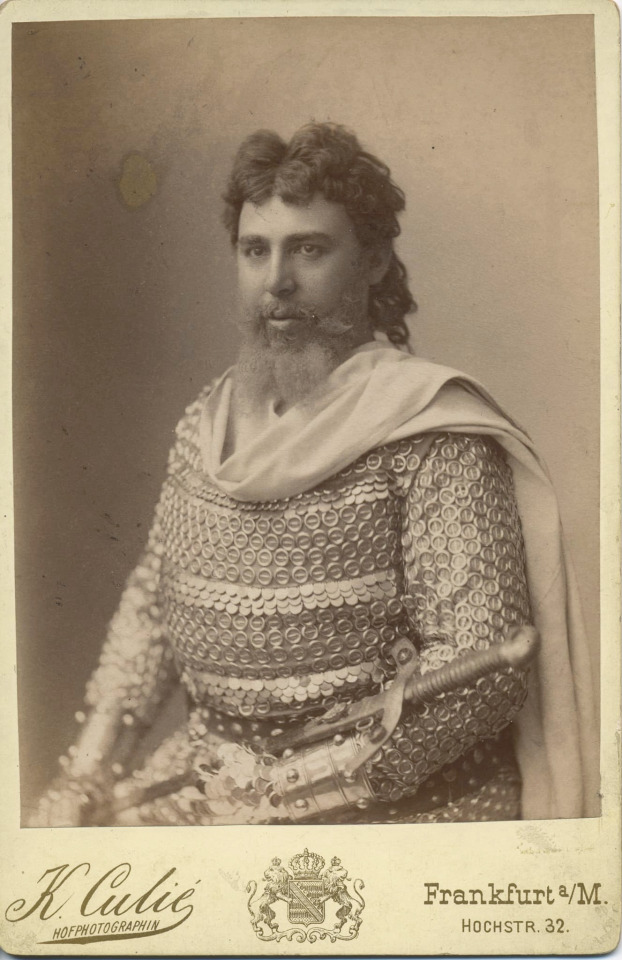

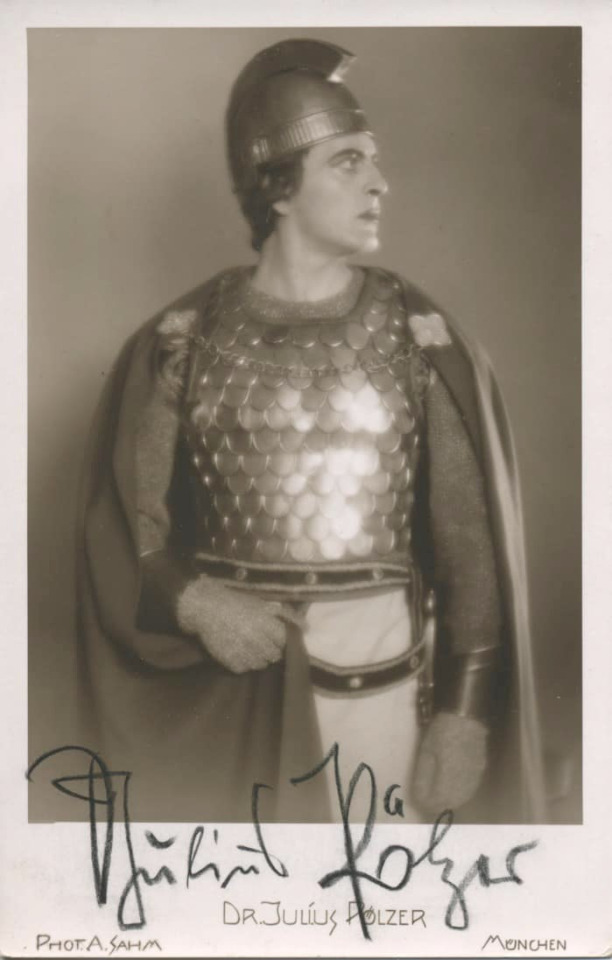

On June 10, 1865, the world premiere of "Tristan and Isolde" by R. Wagner took place in Munich.

„Isolde… wie schön…“

Here are some of the first tenors to have sung the role of Tristan over the years and contributed to the success of this work through their dedication.

Erik Schmedes (27 August 1868, in Gentofte, Denmark – 21 March 1931, in Vienna), Danish heldentenor.

Alois Pennarini (Vienna 1870 - Liberec, Czechoslovakia 1927), Austrian-Hungarian first spinto tenor then heldentenor.

Modest Menzinsky (29 April 1875 in Novosilky, Galicia - 11 December 1935 in Stockholm), Ukrainian heroic tenor.

Karl Kurz-Stolzenberg

Adolf Gröbke (May 26, 1872 Hildesheim - September 16, 1949 Epfach), German tenor.

Iwan Ershov (November 8, 1867 – November 21, 1943), Soviet and Russian dramatic tenor.

Alfred von Bary (January 18, 1873 in Valletta, Malta - September 13, 1926 in Munich), German tenor.

Alexander Bandrowsky (April 22, 1860 in Lubaczów - May 28, 1913 in Cracow), Polish Tenor.

Jacques Urlus (6 January 1867 in Hergenrath, Rhine Province – 6 June 1935 in Noordwijk, Netherlands), Dutch dramatic tenor.

Francesc Viñas (27 March 1863 – 14 July 1933), Spanish tenor.

Richard Schubert (Dessau, Germania; December 15, 1885 - Oberstaufen, Germania; October 12, 1959), German tenor.

Dr. Julius Pölzer (April 9, 1901 in Admont - February 16, 1972 in Vienna), Austrian tenor.

Giuseppe Borgatti (Cento, 17 March 1871 – Reno di Leggiuno, 18 October 1950), dramatic tenor. (with Magini-Coletti as Kurwenal)

Antonio Magini-Coletti (17 February 1855 – 21 July 1912), Italian baritone.

#opera#classical music#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#tenor#classical studies#Tristan and Isolde#classical musician#classical musicians#musician#musicians#classical history#historian of music#history#maestro#chest voice#Tristan und Isolde#Richard Wagner#Wagner#classical singer#classical singing#opera history#music#classical

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

A few inscriptions on tombstones I photographed one day in Canongate Kirkyard, Edinburgh:

To the memory of Janet Cox, Wife of the Reverend Dr. Belfrage, Slateford; Who departed this Life, 28th March, 1821, Aged 35 Years; This Monument is Erected, as a tribute of Affection and Regret, by her husband. She was lovely in her life, as a Devoted Partner, Enlightened Companion, and Faithful Frind; and on her death bed Exemplified the Resignation with which the Christian can suffer, and the Peace with which the Christian can die.

Sacred to the memory of James L. Maxwell who died 18th April 1876, aged 75 years. And of Mary Welsh his wife who died 26th February 1872, aged [68] years. Also of their children William, died [12th] Sept. 1840, aged 8 [½] years. Mary Welsh, died 30 Sept. 18[42], aged 4 ½ years. William L., died 17th March 1844, aged 15 months. Alexander, died [6]th Sept., 1845, aged 5 ½ years. John Welsh, died [19]th June 184[6], aged 14 months. Adam, died 26th Sept. 1848, aged [6] months. Whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die. John [11:26]

In memory of James Blyth who died 6th June 1829, Aged 39 years. And Agnes his daughter who died 12th June 1827, Aged 17 months. And Marion Kerr his wife who died 18th March 1871, Aged 80 years.

Sacred to the Memory of Margaret Davidson, for [38] years the faithful housekeeper of the late Rev. John Clark M.A., minister of the old church St Giles Edinburgh, who died on the 18th April 1862. William Wright, died 4th October 18[63] aged [??] years, for many years the faithful servant of the Rev. John Clark M.A.

In loving memory of my dear husband, Pte. J. A. McConnell, Black Watch, son of the late Peter McConnell, killed in action 25th May 1918 aged 35 years. Interred at Hazelrouch.

Because I walked through these cemeteries and took these pictures, I now know (and so do you) that Janet Cox fell ill and died at age 35, and that her husband, a minister, loved and respected her so much that he wanted the world to know that she went right on impressing the hell out of him even when she was dying. That James and Mary Welsh Maxwell buried six of their children, and then lived another quarter of a century together. That Marion Kerr Blyth lost her baby daughter and her husband two years apart, and lived another 40 years without them. That the Rev. John Clark at St. Giles erected a monument to his servants among the headstones of merchants and scholars and architects. That Mrs. J. A. McConnell may never have visited her husband's grave in France, but she had somewhere to leave flowers for him in Scotland.

And all those people erected those monuments so that you and I would know those things. They didn't write those things for themselves; they already knew them. They wrote them, in stone, so that long after they were gone, people would still be able to read them, and would know these things. Because human lives are fragile and temporary, and when you lose someone, you can't bear the thought that they're just gone and that soon no one will know they were ever here.

don't y9u think it's kind of fucked up and immoral that you go walking around dead people's resting places for fun

do i think going for a walk in a cemetery that's open to the public 24/7 with a footpath and garden and everything is fucked up and immoral? no??? what the fuck???????????

25K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sir William Drummond Stewart (deceased)

Gender: Male

Sexuality: Bisexual

DOB: 26 December 1795

RIP: 28 April 1871

Ethnicity: White - Scottish

Occupation: Soldier, explorer, nobility

#William Drummond Stewart#lgbt history#lgbt#lgbtq#mlm#male#bisexual#1795#rip#historical#white#scottish#soldier#explorer#nobility

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silliman’s backstory timeline, because I like some context for my whaling journal perusals. I love when I’m able to confirm information about these men because I recognize their handwriting. ANYWAY:

Silliman B. Ives is born August 31st 1841 in New Haven, CT.

In 1860 he’s living with his family and working as clerk.

At the start of the American Civil War he immediately enlisted as a Private in the 1st Connecticut Infantry Regiment, April 15th 1861. Age 19.

Became 1st Lieutenant/Adjutant of the 12th CT infantry in December, 1861.

In May of 1863 he applied for a vacancy in provost marshal General James Bowen’s office, in New Orleans.

In December 1863 he was appointed Captain of the 2nd United States Colored Infantry Regiment. He then mustered out of service 29th of December, 1864.

Then he went a’whalin. May 1865 - October 1867 aboard the Vigilant.

Then he went a’whalin again, now 26 nearing 27 (fairly old for a whaleman!), aboard the Sunbeam 1868-1871. (The 1870s Census shows him living with his parents, with the occupation of ‘seaman’).

At some point after it looks like he gets married (as his military pension is collected by a Sarah E. Andrews Ives, listed as his widow. She’s also listed as his widow in subsequent city directories. However there’s no marriage record, and curiously his death record lists him as single.

For at least the last few years of his life he’s living in Brewster MA. He dies at age 52 of heart disease in January 1894 (with his occupation listed as ‘student’, what of, I wonder!). No record of having had any children. Found his wife’s headstone but not his, where she’s listed as ‘Wife of Silliman B. IVES.’ She outlives him by about 16 years, and is buried in Hartford.

#mr ives#I’m like….’will do your family genealogy for free on a saturday morning but only if your ancestor was a whaler’

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Communards, including Gustave Courbet, pose with the statue of Napoléon I from the toppled Vendôme column, Paris 1871

A PotO-Commune Timeline

Here is a summarized timeline of the 1871 Paris Commune combined with some dates relevant to Leroux’s novel. I created this when writing my own Commune fic last summer. Some of the text is from Wikipedia and other sources. I hope you find this helpful if you are considering creating something for PotO-Commune Week, May 21-28, 2021.

I want to emphasize again that this is a very de-centralized call for PotO-Commune content. If you create something, just tag it poto paris commune 1871 so other phans can find it.

January 1862: The foundations are laid for the Garnier Opera house. Considering that Erik had a contract to work on the foundation, he should already be in Paris at least a little before this time. That certainly puts him in Paris during the Commune and probably already living beneath the Garnier as most of the building was completed by 1871.

July 1870 to January 1871: The Franco-Prussian War, also called the War of 1870. Construction on the Garnier stops during the war but the structure is complete enough that the building is used during both the war and later during the Commune.

September 19, 1870 to January 28, 1871: The Siege of Paris, the final days of the war, notable for the awful conditions all citizens of Paris suffered, including severe food shortages.

January 28, 1871: Paris is surrendered to the Prussians. While all regular troops are disarmed, the National Guard of Paris is permitted to keep their arms.

February 16, 1871: The Assembly elects Adolphe Thiers as leader of France.

March 1871: Charles Garnier, already sick from deprivation during the Siege of Paris, leaves Paris until June to recover in Italy. March 18, 1871: Adolphe Thiers attempts to disarm Paris and sends in French troops but they refuse to fire on Parisian workers. Many troops peacefully withdraw, some remain in Paris. Thiers is outraged.

This is also the date when Leroux says the Communards/Fédérés occupied the Opera house.

March 26, 1871: A municipal council — the Paris Commune is elected by the citizens of Paris.

March 30, 1871: The Commune abolishes conscription and the standing French army. All citizens are allowed to bear arms and can enroll in the National Guard - the National Guard was separate from the French Army, and they are now set against each other.

The Commune remits all payments of rent for dwelling houses from October 1870 until April 1871.

April 2, 1871: The French Army begins its own siege of Paris.

The Commune decrees the separation of the Church from the State, and the abolition of all state payments for religious purposes as well as the transformation of all Church property into national property. Religion is declared a purely private matter.

April 20, 1871: The Commune abolishes night work for bakers.

April 23, 1871: Thiers breaks off the negotiations for a hostage exchange. The Archbishop of Paris and 62 others are held hostage by the Commune, for one man, Louis Auguste Blanqui, who had twice been elected to the Commune but was imprisoned by the French government.

May 6: First Commune sponsored concert at the Tuileries Palace

May 9, 1871: Fort Issy, which is completely reduced to ruins by gunfire and constant French bombardment, is captured by the French army.

May 11: Second Tuileries Concert

May 16: The Vendôme is toppled. Artist Gustave Courbet was blamed for this and imprisoned and charged for the cost of the statue after the fall of the Commune. He never paid.

May 18: Third Tuileries Concert

May 21: Fourth and last Tuileries Concert

Barricade at Rue de Rivoli constructed (Where was Daroga during all this?)

May 21-28, 1871: La Semaine Sanglante

French Army/Versaillais troops enter Paris on May 21. The Versaillais spend eight days massacring Communards, workers and civilians. Marshal MacMahon, who would later become president of France, leads the operation. Tens of thousands of workers are summarily executed. Some estimate as many as 30,000 people. 38,000 others imprisoned and 7,000 are forcibly deported.

May 23, 1871: Republican troops oust the Communards from the Opera

The Tuileries Palace is set on fire and burns until the next day.

May 24, 1871: Archbishop Darboy and all other 62 hostages held by the Commune are executed.

May 28, 1871: 147 Communards are executed after a shoot out in the Cimetière du Père-Lachaise. They were buried on site at what is now called the Mur des Fédérés or Communard Wall. The Commune is effectively over.

August 8, 1873: Notable Communard and Anarchist Louise Michel is deported to New Caledonia, among many others.

October 29, 1873: The Salle le Peletier, home of the Paris Opera, burns down.

January 25, 1875: The Palais Garnier finally opens as the new home of the Paris Opera.

#phantom of the opera#le fantôme de l'opéra#gaston leroux#paris commune#paris commune 1871#poto paris commune 1871#poto

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

A brown moth fluttered.

The curtain was down, and the carpenters were rearranging the “No, no, no! I can’t breathe 1 volatile I can’t breathe.” And such a fit of suffocating 2 “I can’t breathe,” she would sometimes say 3 and the minisnever! I can’t breathe it in fast enough, nor hard enough, nor long enough.” 4 and started up up. to return to the tent, only to check him No, I can’t breathe the same air self in the act as often as he started, with ye to-night, but ye’ll go into the he lost consciousness in uneasy dreams 5 meet me at the station. I can’t breathe in this wretched 6 “sickening down there — I can’t breathe! I can’t stand it, Drewe! It’s killing me!” — Tears 7 struggling to altitudes that I can’t breathe in. I could help him when he was in despair, but he is the sort who 8 sometimes I find I can’t breathe in it. Perhaps some folks will say “so much the worse for you” 9 it seems if I can’t breathe in the house. not dared hope 10 “Well, I won’t wear ’em. I can’t breathe” “Sure! Blame ’em!” “I can’t breathe a square breath.” Oh 11 things I regret I can’t breathe. 12 bramble bush. I can’t breathe. I can’t eat. I can’t do anything much. It’s clear to my knees. 13 I can't breathe, I can't talk, 14 lying on its “I can’t stay here I can’t breathe” side, the cork half-loosened. A brown moth fluttered. 15 “I can’t breathe beside you.” 16 the needs of any reasonable young lady. “I can't breathe there, 17 I can’t breathe — I really need the rush of this wintry air to restore me!” 18 I can’t breathe no more in that coop upstairs . tablet ; two he said is what you need.” of flame shoots through a stream of oil 19 no friction. It’s friction—rub- / asthmatically.] “I can’t breathe deep — I can light and of reason. But I’ve a notion 20 out of it. I can’t breathe in the dark. I can’t. I / She withdrew 21 “I can’t breathe or feel in” 22 Up a flight of stairs, and there was the girl, sitting on the edge of an untidy bed. The yellow sweater was on the floor. She had on an underskirt and a pink satin camisole. “I can't breathe !” she gasped. 23 I can’t breathe in the dark! I can’t! I can’t! I can’t live in the dark with my eyes open! 24 One never gets it back! How could one! And I can’t breathe just now, on account of 25 that old stuff, I could shriek. I can’t breathe in the same room with you. The very sound of 26 don’t! I can’t — breathe.... I’m all — and bitter howling. 27

sources (pre-1923; approximately 90 in all, from which these 27 passages, all by women)

1 ex “Her Last Appearance,” in Peters’ Musical Monthly, And United States Musical Review 3:2 (New-York, February 1869), “from Belgravia” : 49-52 (51) “Her Last Appearance” appeared later, “by the author of Lady Audley’s Secret” (M.E. Braddon, 1835-1915 *), in Belgravia Annual (vol. 31; Christmas 1876) : 61-73 2 snippet view ex The Lady’s Friend (1873) : 15 evidently Frances Hodgson Burnett (1849-1924 *) her Vagabondia : A Love Story (New York, 1891) : 286 (Boston, 1884) : 286 (hathitrust) 3 ex “The Story of Valentine; and his Brother.” Part VI. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine vol. 115 (June 1874) : 713-735 (715) authored by Mrs. [Margaret] Oliphant (1828-97 *), see her The Story of Valentine (1875; Stereotype edition, Edinburgh and London, 1876) : 144 4 OCR confusions at Olive A. Wadsworth, “Little Pilkins,” in Sunday Afternoon : A Monthly Magazine for the Household vol. 2 (July-December 1878) : 73-81 (74) OAW “Only A Woman” was a pseudonym of Katharine Floyd Dana (1835-1886), see spoonercentral. Katharine Floyd Dana also authored Our Phil and Other Stories (Boston and New York, 1889) : here, about which, a passage from a bookseller's description — Posthumously published fictional sketches of “negro character,” first published in the Atlantic Monthly under the pseudonym Olive A. Wadsworth. The title story paints a picture of plantation life Dana experienced growing up on her family’s estate in Mastic, Long Island. Although a work of fiction set in Maryland, the character of Phil may of been named for a slave once jointly owned by the Floyds and a neighboring family. source see also the William Buck and Katherine Floyd Dana collection, 1666-1912, 1843-1910, New York State Historical Documents (researchworks). 5 OCR cross-column misread, at M(ary). H(artwell). Catherwood (1847-1902 *), “The Primitive Couple,” in Lippincott’s Magazine of Popular Literature and Science 36 (August 1885) : 138-146 (145) author of historical romances, short stories and poetry, and dubbed the “Parkman of the West,” her papers are at the Newberry Library (Chicago) 6 ex Marie Corelli (Mary Mackay; 1855-1924 *), Thelma, A Norwegian Princess: A Novel, Book II. The Land of Mockery. Chapter 12 (New Edition, London, 1888) : 432 7 preview snippet (only), at Ada Cambridge (1844-1926 *), Fidelis, a Novel ( “Cheap Edition for the Colonies and India,” 1895) : 289 full scan, (New York, 1895) : 261 born and raised in England, spent much of her life in Australia (died in Melbourne); see biography (and 119 of her poems) at the Australia Poetry Library in particular, the striking poems from Unspoken Thoughts (1887) here (Thomas Hardy comes to mind) 8 snippet view (only) at F(rances). F(rederica), Montrésor (1862-1934), At the Cross-Roads (London, 1897) : 297 but same page (and scan of entirety) at hathitrust see her entry At the Circulating Library (Database of Victorian Fiction 1837-1901) an interesting family. Montrésor’s The Alien: A Story of Middle Age (1901) is dedicated to her sister, C(harlotte). A(nnetta). Phelips (1858-1925), who was devoted to work for the blind. See entry in The Beacon, A Monthly magazine devoted to the interests of the blind (May 1925) a great-granddaughter of John Montresor (1737-99), a British military engineer and cartographer, whose colorful (and unconventional) life is sketched at wikipedia. 9 Alice H. Putnam, “An Open Letter,” in Kindergarten Review 9:5 (Springfield, Massachusetts; January 1899) : 325-326 Alice Putnam (1841-1919) opened the first private kindergarten in Chicago; Froebel principles... (wikipedia); see also “In Memory of Alice H. Putnam” in The Kindergarten-primary Magazine 31:7 (March 1919) : 187 (hathitrust) 10 OCR cross-column misread, at Mabel Nelson Thurston (1869?-1965?), “The Palmer Name,” in The Congregationalist and Christian World 86:30 (27 July 1901) : 134-135 author of religiously inflected books (seven titles at LC); first female admitted for entry at George Washington University (in 1888). GWU archives 11 OCR cross-column misread, at Margaret Grant, “The Romance of Kit Dunlop,” Beauty and Health : Woman’s Physical Development 7:6 (March 1904): 494-501 (499 and 500) the episodic story starts at 6:8 (November 1903) : 342 12 ex Marie van Vorst (1867-1936), “Amanda of the Mill,” The Bookman : An illustrated magazine of literature and life 21 (April 1905) : 190-209 (191) “writer, researcher, painter, and volunteer nurse during World War I.” wikipedia 13 ex Maude Morrison Huey, “A Change of Heart,” in The Interior (The sword of the spirit which is the Word of God) 36 (Chicago, April 20, 1905) : 482-484 (483) little information on Huey, who is however mentioned in Paula Bernat Bennett, her Poets in the Public Sphere : The Emancipatory Project of American Women's Poetry, 1800-1900 (2003) : 190 14 ex Leila Burton Wells, “The Lesser Stain,” The Smart Set, A Magazine of Cleverness 19:3 (July 1906) : 145-154 (150) aside — set in the Philippines, where “The natives were silent, stolid, and uncompromising.” little information on Wells, some of whose stories found their way to the movie screen (see IMDB) The Smart Set ran from March 1900-June 1930; interesting story (and decline): wikipedia 15 OCR cross-column misread, at Josephine Daskam Bacon (1876-1961 *), “The Hut in the Wood: A Tale of the Bee Woman and the Artist,” in Collier’s, The National Weekly 41:12 (Saturday, June 13, 1908) : 12-14 16 ex E. H. Young, A Corn of Wheat (1910) : 90 Emily Hilda Daniell (1880-1949), novelist, children’s writer, mountaineer, suffragist... wrote under the pseudonym E. H. Young. (wikipedia) 17 ex Mary Heaton Vorse (1874-1966), “The Engagements of Jane,” in Woman’s Home Companion (May 1912) : 17-18, 92-93 Illustrated by Florence Scovel Shinn (1871-1940, artist and book illustrator who became a New Thought spiritual teacher and metaphysical writer in her middle years. (wikipedia)) Mary Heaton Vorse — journalist, labor activist, social critic, and novelist. “She was outspoken and active in peace and social justice causes, such as women's suffrage, civil rights, pacifism (such as opposition to World War I), socialism, child labor, infant mortality, labor disputes, and affordable housing.” (wikipedia). 18 ex snippet view, at “Voices,” by Runa, translated for the Companion by W. W. K., in Lutheran Companion 20:3 (Rock Island, Illinois; Saturday, January 20, 1912) : 8 full view at hathitrust same passage in separate publication as Voices, By Runa (pseud. of E. M. Beskow), from the Swedish by A. W. Kjellstrand (Rock Island, Illinois, 1912) : 292 E(lsa). M(aartman). Beskow (1874-1953), Swedish author and illustrator of children’s books (Voices seems rather for older children); see wikipedia 19 ex Fannie Hurst (1885-1968 *), “The Good Provider,” in The Saturday Evening Post 187:1 (August 15, 1914) : 12-16, 34-35 20 OCR cross-column misread, at Anne O’Hagan, “Gospels of Hope for Women: A few new creeds, all of them modish—but expensive” in Vanity Fair (February 1915) : 32 Anne O’Hagan Shinn (1869-1933) — feminist, suffragist, journalist, and writer of short stories... “known for her writings detailing the exploitation of young women working as shop clerks in early 20th Century America... O’Hagan participated in several collaborative fiction projects...” (wikipedia) a mention of St. Anselm, whose “sittings” are free, vis-à-vis “Swami Bunkohkahnanda”... “Universal Harmonic Vibrations”... 21 OCR cross-column misread (three columns), at Fannie Hurst (1885-1968 *), “White Goods” (Illustrations by May Wilson Preston) in Metropolitan Magazine 42:3 (July 1915) : 19-22, 53 repeated, different source and without OCR misread, at 24 below 22 ex Mary Patricia Willcocks, The Sleeping Partner (London, 1919) : 47 (snippet only) full at hathitrust see onlinebooks for this and other of her titles. something on Mary Patricia Willcocks (1869-1952) at ivybridge-heritage. in its tone and syntax, her prose brings Iris Murdoch to mind. 23 Katharine Wendell Pedersen, “Clingstones, A week in a California cannery.” in New Outlook vol. 124 (February 4, 1920) : 193-194 no information about the author. the journal began life as The Christian Union (1870-1893) and continued under the new title into 1928; it ceased publication in 1935; it was devoted to social and political issues, and was against Bolshevism (wikipedia) 24 ex Fannie Hurst (1885-1968 *), “White Goods,” in her Humoresque : A Laugh on Life with a Tear Behind it (1919, 1920) : 126-169 (155) 25 ex snippet view, at Letters and poems of Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva), with an introduction and notes by Henry Howard Harper. Volume 2 (of 2; Boston, Printed for members only, The Bibliophile society, 1920) : 51 (hathitrust) Carmen Sylva was “the pen name of Elisabeth, queen consort of Charles I, king of Rumania” (1843-1916 *) 26 OCR cross-column misread, at Ruth Comfort Mitchell, “Corduroy” (Part Three; Illustrated by Frederick Anderson), in Woman’s Home Companion 49:8 (August 1922) : 21-23, 96-97 (hathitrust) Ruth Comfort Mitchell Young (1882-1954), poet, dramatist, etc., and owner of a remarkable house (in a “Chinese” style) in Los Gatos, California (wikipedia) 27 Helen Otis, “The Christmas Waits,” in Woman’s Home Companion 49:12 (Christmas 1922) : 36 probably Helen Otis Lamont (1897-1993), about whom little is found, save this “Alumna Interview: Helen Otis Lamont, Class of 1916” (Packer Collegiate Institute, Brooklyn, 1988) at archive.org (Brooklyn Historical Society)

—

prompted by : recent thoughts about respiration (marshes, etc.); Pfizer round-one recovery focus on the shape of one breath, then another; inhalation, exhalation and the pleasure of breathing; and for whom last breaths are no pleasure (far from it); last breaths (Robert Seelthaler The Field (2021) in the background).

1 of n

all tagged breath all tagged cento

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of a Communard (1) : Arthur Arnould (1833-1895)

During the Second Empire, Arthur Arnould was a journalist at the Revue nationale, a newspaper opposed to Napoleon III. In 1870, he joined La Marseillaise.

After the proclamation of the Third Republic, he became assistant librarian of the city of Paris.

On March 26, 1871, he was elected to the Council of the Commune, as a representative of the 4th arrondissement. He was first a member of the Commission of External Relations, whose delegate was Pascal Grousset. In April, he joined the Commission of Labor and Exchange, whose delegates were Augustin Avrial, Léo Frankel, Benoît Malon, and Albert Theisz. He then joined the Commission of Subsistence, under the responsibility of Auguste Viard. Finally, we find him at the Commission de l’Enseingement, under the responsibility of Edouard Vaillant.

During the Commune, Arthur Arnould worked for Le Rappel, La Nouvelle République, and L’ Affranchi. On May 1, alongside Auguste Vermorel, he became an editor at the Journal officiel. When the Committee of Public Safety was created, he was one of the nineteen internationalists of the anti-authoritarian minority, alongside Andrieu, Avrial, Babick, Beslay, Chalain, Clémence, Cluseret, Frankel, Girardin, Langevin, Lefrançais, Longuet, Malon, Pindy, Serraillier, Rheiz, Vaillant, Varlin. As a reminder, the Committee of Public Safety, following the proposal of Jules Miot, was established on May 1, 1871, by 45 votes to 22. The five members were Antoine Arnaud, Gabriel Ranvier, Léo Meillet, Félix Pyat, and Charles Gérardin. The anti-authoritarians saw their power confiscated by the Committee of Public Safety; they were ousted from the delegations. On May 15, Arthur Arnoult signed the declaration of the internationalist minority, which publicly denounced the "dictatorship" of the Committee of Public Safety, "The Paris Commune has abdicated its power into the hands of a dictatorship to which it has given the name of Public Safety."

In November 1872, Arthur Arnould was sentenced in absentia to deportation. He therefore took refuge in Switzerland with his wife Jeanne Matthey (Jenny). In Geneva, among the proscribed, he was active in the Socialist Revolutionary Propaganda and Action Section. In 1873, he was sent to Lugano to attend the congress of the International League for Peace and Freedom. A year after the Saint-Imier Congress, he became close to Bakunin.

In 1874, he left for Argentina with Jenny.

In 1876, Bakunin died. Arthur Arnould was one of the people responsible for managing his manuscripts, which he then passed on to James Guillaume. In Geneva, he contributed to the Bulletin de la Fédération jurassienne, La Commune, and Le Travailleur. He published L’État et la Révolution (in 1877), and his Histoire populaire et parlementaire de la Commune de Paris (in 1878). With Gustave Lefrançais, he wrote Souvenirs de deux communards réfugiés à Genève, 1871-1873.

He also wrote novels under the pseudonym A.Matthey.

In the 1880s, when he returned to France, we can say that the character changed, and not in a good way, for a former communard and anarchist ! In 1881, he joined the Republican Socialist Alliance, a reformist socialist party of which Clemenceau was a member... A few years later, he had to deal with Jenny's death... The worst thing about his evolution was that he would have accepted to be decorated with the Order of Isabella the Catholic ! Then he joined an esoteric sect, the Theosophical Society.

Nevertheless, I would not say that he had completely erased his past as a communard and anarchist, since he still wrote an article about Bakunin in the Nouvelle Revue in 1891.

He died in 1895.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honoring Ida Tarbell on the anniversary of her birthday November 5, 1857

Ida M. Tarbell, c. 1904. Photo: Wikipedia

At the age of 14, Ida Tarbell witnessed the Cleveland Massacre, in which dozens of small oil producers in Ohio and Western Pennsylvania, including her father, were faced with a daunting choice that seemed to come out of nowhere: sell their businesses to the shrewd, confident 32 year-old John D. Rockefeller, Sr. and his newly incorporated Standard Oil Company, or attempt to compete and face ruin. She didn’t understand it at the time, not all of it, anyway, but she would never forget the wretched effects of “the oil war” of 1872, which enabled Rockefeller to leave Cleveland owning 85 percent of the city’s oil refineries.

Tarbell was, in effect, a young woman betrayed, not by a straying lover but by Standard Oil’s secret deals with the major railroads—a collusive scheme that allowed the company to crush not only her father’s business, but all of its competitors. Almost 30 years later, Tarbell would redefine investigative journalism with a 19-part series in McClure’s magazine, a masterpiece of journalism and an unrelenting indictment that brought down one of history’s greatest tycoons and effectively broke up Standard Oil’s monopoly. By dint of what she termed “steady, painstaking work,” Tarbell unearthed damaging internal documents, supported by interviews with employees, lawyers and—with the help of Mark Twain—candid conversations with Standard Oil’s most powerful senior executive at the time, Henry H. Rogers, which sealed the company’s fate.

She became one of the most influential muckrakers of the Gilded Age, helping to usher in that age of political, economic and industrial reform known as the Progressive Era. “They had never played fair,” Tarbell wrote of Standard Oil, “and that ruined their greatness for me.”

Ida Minerva Tarbell was born in 1857, in a log cabin in Hatch Hollow, in Western Pennsylvania’s oil region. Her father, Frank Tarbell, spent years building oil storage tanks but began to prosper once he switched to oil production and refining. “There was ease such as we had never known; luxuries we had never heard of,” she later wrote. Her town of Titusville and surrounding areas in the Oil Creek Valley “had been developed into an organized industry which was now believed to have a splendid future. Then suddenly this gay, prosperous town received a blow between the eyes.”

That blow came in the form of the South Improvement Company, a corporation established in 1871 and widely viewed as an effort by Rockefeller and Standard Oil in Ohio to control the oil and gas industries in the region. In a secret alliance with Rockefeller, the three major railroads that ran through Cleveland—the Pennsylvania, the Erie and the New York Central—agreed to raise their shipping fees while paying “rebates” and “drawbacks” to him.

Word of the South Improvement Company’s scheme leaked to newspapers, and independent oilmen in the region were outraged. “A wonderful row followed,” Tarbell wrote. “There were nightly anti-monopoly meetings, violent speeches, processions; trains of oil cars loaded for members of the offending corporation were raided, the oil run on the ground, their buyers turned out of the oil exchanges.”

Tarbell recalled her father coming home grim-faced, his good humor gone and his contempt directed no longer at the South Improvement Company but at a “new name, that of the Standard Oil company.” Franklin Tarbell and the other small oil refiners pleaded with state and federal officials to crack down on the business practices that were destined to ruin them, and by April of 1872 the Pennsylvania legislature repealed the South Improvement Company’s charter before a single transaction was made. But the damage had already been done. In just six weeks, the threat of an impending alliance allowed Rockefeller to buy 22 of his 26 competitors in Cleveland. “Take Standard Oil Stock,” Rockefeller told them, “and your family will never know want.” Most who accepted the buyouts did indeed become rich. Franklin Tarbell resisted and continued to produce independently, but struggled to earn a decent living. His daughter wrote that she was devastated by the “hate, suspicion and fear that engulfed the community” after the Standard Oil ruckus. Franklin Tarbell’s partner, “ruined by the complex situation,” killed himself, and Tarbell was forced to mortgage the family home to meet his company’s debts.

Rockefeller denied any conspiracy at the time, but years later, he admitted in an interview that ���rebates and drawbacks were a common practice for years preceding and following this history. So much of the clamor against rebates and drawbacks came from people who knew nothing about business. Who can buy beef the cheaper—the housewife for her family, the steward for a club or hotel, or the quartermaster or commissary for an army? Who is entitled to better rebates from a railroad, those who give it for transportation 5,000 barrels a day, or those who give 500 barrels—or 50 barrels?”

Presumably, with Rockefeller’s plan uncovered in Cleveland, his efforts to corner the market would be stopped. But in fact, Rockefeller had already accomplished what he had set out to do. As his biographer Ron Chernow wrote, “Once he had a monopoly over the Cleveland refineries, he then marched on and did the same thing in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York and the other refining centers. So that was really the major turning point in his career, and it was really one of the most shameful episodes in his career.”

Still a teenager, Ida Tarbell was deeply impressed by Rockefeller’s machinations. “There was born in me a hatred of privilege, privilege of any sort,” she later wrote. “It was all pretty hazy, to be sure, but it still was well, at 15, to have one definite plan based on things seen and heard, ready for a future platform of social and economic justice if I should ever awake to my need of one.”