#1882 after Manet)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Robert Longo. Untitled (X-Ray of A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882 after Manet), 2017 (detail). Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac London · Paris · Salzburg. Photograph: Artist Studio.

#Robert Longo#Untitled (X-Ray of A Bar at the Folies-Bergère#2017#X-Ray#A Bar at the Folies-Bergère#after Manet#1882#1882 after Manet)

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Isaac Israëls, 1865-1934 In the danshouse, Amsterdam oil on canvas 97.5 x 74.5 cm, signed l.l. and painted ca. 1892-1897.

Son of the Hague School artist Jozef Israels, Isaac Israels was a leading figure of the Amsterdam Impressionism movement, renowned for his highly personal, luminous and free brushwork and subjects from his travels to Paris, London, and Indonesia.

At the mere age of thirteen, Israels attended the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague where he befriended Georg Hendrik Breitner. Between 1880 and 1884, Israels and Breitner were both particularly fascinated by military subjects and in 1882 Israels debuted at the Salon with Military Burial. In 1886, the two artists enrolled at the Reijksacademie in Amsterdam but after only a year the pair left the academy and joined the circle of the Tachtigers (or ‘Eighties’ group), a progressive Dutch movement of writers and artists.

Through trips to Paris with his father, Israels had come into contact with the French realist writers Emile Zola and J.K. Huysmans. In 1894, Israels received a permit to take his easel to the streets and paint the urban milieu en plein air. 1900, he was introduced by his childhood friend Thérèse Schwartze to the Amsterdam fashion house Hirsch & Cie, in whose studios he regularly painted.

In 1904, Israels moved to Paris. The parks, cafes, cabarets, and street scenes which Israels studied in Amsterdam continued to be his chosen subject in Paris; however, he also took to painting acrobats and fairgrounds. Israels moved to London in the spring of 1913 but grew increasingly frustrated here as the outbreak of the First World War prevented him from painting out in the streets. He redirected his interests towards boxers and wrestlers. He returned to Holland for the remainder of the war, moving between The Hague, Amsterdam and Scheveningen, where he used to holiday with his father, accompanied by other artists such as Edouard Manet.

After the war, Israels passed much of 1919 in Paris and then spent 1920 in Copenhagen, Stockholm and London. Between 1921 and 1922, Israels and his friend Jan Veth went to Java and Bali after befriending many East Indians during the war. Israels was enraptured by the landscape and people whom he encountered in South East Asia. He sketched the household of the local ruler at Solo, and produced numerous watercolours and oil paintings of Balinese women, Chinese weddings, dancing girls, bands, beggars and children. Upon his return, Israels spent the greater part of 1923 in The Hague where he took over his father’s studio. During this time, his focus returned to theatre-life and portraits. Israels received significant awards for his artistic achievements including a knighthood in 1925 and an Olympic Award for Art three years later.

Sotheby's

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Dorothea Arnault, drawn into the painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergere by Manet from 1882. I’m writing a paper about this painting for a university class, and while doing research, was struck by the kinds of things I could be saying about this character and this painting by making this.

A common assumption about this painting is that the interaction in the reflection between the man and the woman is more or less sexual in nature. Bargirls in general, and especially those at this particular venue in Paris, were known for being more or less sexually available. Anyone who knows Dorothea knows that part of how she externally presents herself is pretty sexual, though she also gives off a very confident air, something that says you could never have her.

One prevalent interpretation of the difference between the reflection and what we can see of the “real” girl is that one represents her inner world and one represents her outer world—generally the mirror being an inner world and her detached expression being her outer world. I don’t personally agree with that interpretation, but I thought it would be interesting to put Dorothea into that context, and make you wonder which is really the internal and which is the external. She flirts a lot to succeed in her self-imposed external goals, like the girl’s reflection may be doing in the painting, but I always got the sense that she would rather have something more real than that, if she could.

But—Dorothea is at heart a performer. I could imagine that she longs for the glitz and glamour as shown by the crowd in the painting. Perhaps she’s metaphorically stuck behind this bar while wishing she could indulge in the fantasy more than she is. Perhaps the man off to the right is not superficially propositioning her for sexual favors but interested in *her* her, and that is the real fantasy. He does look stoic.

So is the mirror reflecting reality while you see her as she really is, or do you see her hopes and dreams in the mirror?

As for the second point, the one that really made me think ‘Dorothea’:

It is important to know the historical context in which this painting was done—the cusp of industrialization, which is a time period I enjoy picturing Dorothea’s home city of Enbarr in. Cities became metropolises, huge and crowded and bursting with a growing kind of middle class, which meant more people had a bit more free time and free money to spend on entertainment and luxurious goods. The lowering costs of production and travel meant that more goods and entertainment were available. The department store made its big debut around this era, the Era of Crowds, and they’re applicable to my point for two big reasons.

First, they were a kind of adventure. With salespeople behind counters, goods within your senses of touch and taste, glittering displays, and huge venues, going to a department store meant spending your day being assaulted with all kinds of within-budget spectacles.

Second, stores adopted other forms of entertainment—some added cafes, others theaters, others *became* theaters after hours. Managers hired performers, hosted events, generally did all kinds of things to advertise and get people to spend their time in their stores.

These things combined meant that shopping and entertainment sort of conflated together. A store became a show, a show often became a store with merchandise and bars and cafes. Due to this association, salesgirls and bartenders and other service people became performers in their own contexts.

Dorothea *is* a performer. She’s a talented opera singer, the star of many shows, who left her success to go to a school and secure her future (by finding a rich husband, as she says.) She’s not a literal salesgirl, but she is metaphorically. By positioning her at the bar in the painting, a bar that almost looks like it extends into your space, is she potentially asking you to buy her future? Is she judging the passersby like a customer at a store? Does she wish she was one of the performers, like the trapeze artist we can barely see in the top left? Does she wish she wasn’t part of this whole spectacle at all?

There is also something to be said for the mixed clientele of an entertainment venue of a place like the Folies-Berger—people from many social classes mixed and saw themselves in those mirrors as wealthy socialites partaking in luxury. One of Dorothea’s themes is the seemingly arbitrary division between her world’s nobility and commoners. As a commoner herself that interacts regularly with the upper class, she doesn’t think the division should exist at all, much less be as pronounced as it’s shown in her story. The working class of this time period, such as barmaids like the one shown, often dressed in a higher-class fashion as per their uniforms to appeal to more people. Those attending a venue like this may not have been the wealthiest, but they wanted to feel like they were. This place of false luxury is at odds with Dorothea’s ideals, making her place in this painting and the questions about the reflection and her role all the more obvious.

While putting this specific character in the context of this painting answers some questions, I believe it raises more, and highlights some of those I find the most interesting. Is the mirror a reflection of her dreams or is it her harsh reality? What is she selling and does she even want to? And is any part of this literal, or is it purely a metaphor, a piece of poetry, a collection of good questions in one image?

…I should really go write my real essay now.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝒜𝓁𝑔𝓊𝓃𝒶𝓈 𝑜𝒷𝓇𝒶𝓈 𝒾𝓂𝓅𝓇𝑒𝓈𝒾𝑜𝓃𝒾𝓈𝓉𝒶𝓈

Berthe Morisot (1841 - 1895) ; Después del almuerzo, 1881 Técnica: óleo sobre lienzo ; Dimensiones: desconocido Colección privada ; https://www.wikiart.org/es/berthe-morisot/after-luncheon

Berthe Morisot ; La cuna, 1872 Técnica: pintura al óleo ; Dimensiones: 56 x 46 cm Museo de Orsay, París, Francia ; https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_cuna#/media/Archivo:Berthe_Morisot_008.jpg

Mary Cassatt ( 1844 - 1926) ; Verano, 1894 Técnica: óleo sobre lienzo ; Dimensiones: 100.6 x 81.3 cm Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, EE.UU. ; https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Cassatt#/media/Archivo:Mary_Cassatt_-_Summertime_-_TFAA_1988.25.jpg

Paul Cézanne (1839 - 1906) ; Naturaleza muerta con flores y frutas, 1890 Técnica: óleo sobre lienzo ; Dimensiones: 62 x 65 cm Museo de Orsay, París, Francia ; https://arthive.com/es/paulcezanne/works/375411~Naturaleza_muerta_con_flores_y_frutas

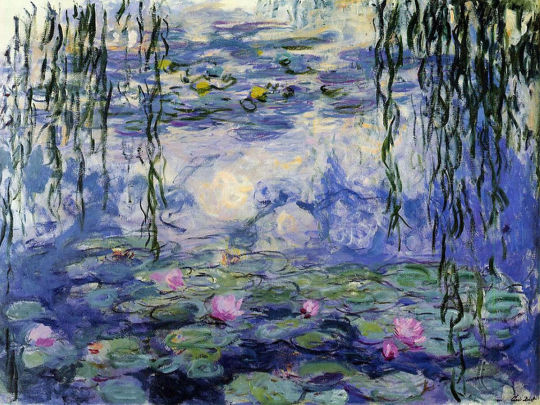

Claude Monet (1840 - 1926) ; Los Nenúfares, 1920 - 1926 Técnica: óleo sobre tela ; Dimensiones: desconocido Orangerie de las Tullerías, París, Francia ; https://www.salirconarte.com/magazine/curiosidades-sobre-los-nenufares-de-monet/

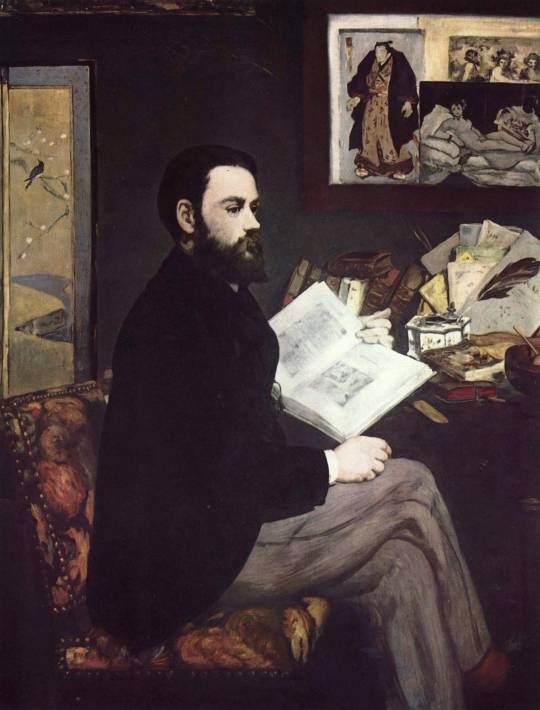

Édouard Manet (1832 - 1883) ; Un bar del Folies-Bergère, 1882 Técnica: pintura al óleo ; Dimensiones: 96 x 130 cm Courtauld Gallery, Londres, Reino Unido ; https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0d/Edouard_Manet%2C_A_Bar_at_the_Folies-Berg%C3%A8re.jpg

#semana 4#uam#impresionismo#arte impresionista#pintura#arte#siglo xix#siglo xx#berthe morisot#mary cassat#paul cezanne#claude monet#edouard manet#morisot#cassat#cezanne#monet#manet

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Artist Research

Jeff Wall

Most of his famous references to painting are also tributes to modern painting led by Baudelaire's aesthetics. Through precise and ingenious arrangement and thinking, the contradictions and conflicts in the reality of western society are episodic. The systematic study of art history background and the support of the rise of digital technology not only become the inspiration of his creation, but also make the audience often confused about what is true and what is false.

Wall’s early pictures evoke the history of image making by overtly referring to other artworks: The Destroyed Room (1978) explores themes of violence and eroticism inspired by Eugène Delacroix’s monumental painting The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), while Picture for Women (1979) recalls Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) and brings the implications of that famous painting into the context of the cultural politics of the late 1970s. These two pictures are models of a thread in Wall’s work that the artist calls “blatant artifice”: pictures that foreground the theatricality of both their subject and their production. A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), reinterprets the scene in a woodcut print by Japanese printmaker and painter Katsushika Hokusai. Part of the larger portfolio called The Thirty-six Views of Fuji, Hokusai's original image, Travelers Caught in a Sudden Breeze at Ejiri (c. 1832), depicts seven individuals caught off-guard in the wind at different points along a narrow path. (https://gagosian.com/artists/jeff-wall/)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Untitled (X-Ray of A Bar at the Folies-Bergères, 1882, after Manet" de Robert Longo au fusain (2017) et "Un Bar aux Folies Bergère d'après Manet" de Vik Muniz à partir d'images de magazine (2012) en référence à “Un Bar aux Folies Bergère" d'Édouard Manet (1881-82) présentés à la conférence “L'Art Contemporain a-t-il de la mémoire ?“ par Paul Bernard-Nouraud - Historien d'Art - pour le cycle “Etre de son Temps : L'Art Contemporain Face à l'Epoque” de l'association Des Mots et Des Arts, décembre 2021.

#conferences#peinture#food#photomontage#Muniz#Manet#BernardNouraud#DesMotsDesArts#style#dentelle#Longo#illustrations

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Édouard Manet French: 23 January 1832 – 30 April 1883) was a French modernist painter. He was one of the first 19th-century artists to paint modern life, and a pivotal figure in the transition from Realism to Impressionism.

Born into an upper-class household with strong political connections, Manet rejected the future originally envisioned for him, and became engrossed in the world of painting. His early masterworks, The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe) and Olympia, both 1863, caused great controversy and served as rallying points for the young painters who would create Impressionism. Today, these are considered watershed paintings that mark the start of modern art. The last 20 years of Manet's life saw him form bonds with other great artists of the time, and develop his own style that would be heralded as innovative and serve as a major influence for future painters.

Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe ( Luncheon on the Grass )

A major early work is The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe), originally Le Bain. The Paris Salon rejected it for exhibition in 1863, but Manet agreed to exhibit it at the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected) which was a parallel exhibition to the official Salon, as an alternative exhibition in the Palais des Champs-Elysée. The Salon des Refusés was initiated by Emperor Napoleon III as a solution to a problematic situation which came about as the Selection Committee of the Salon that year rejected 2,783 paintings of the ca. 5000. Each painter could decide whether to take the opportunity to exhibit at the Salon des Refusés, less than 500 of the rejected painters chose to do so.

Manet employed model Victorine Meurent, his wife Suzanne, future brother-in-law Ferdinand Leenhoff, and one of his brothers to pose. Meurent also posed for several more of Manet's important paintings including Olympia; and by the mid-1870s she became an accomplished painter in her own right.

The painting's juxtaposition of fully dressed men and a nude woman was controversial, as was its abbreviated, sketch-like handling, an innovation that distinguished Manet from Courbet. At the same time, Manet's composition reveals his study of the old masters, as the disposition of the main figures is derived from Marcantonio Raimondi's engraving of the Judgement of Paris (c. 1515) based on a drawing by Raphael.

Two additional works cited by scholars as important precedents for Le déjeuner sur l'herbe are Pastoral Concert (c. 1510, The Louvre) and The Tempest (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice), both of which are attributed variously to Italian Renaissance masters Giorgione or Titian. The Tempest is an enigmatic painting featuring a fully dressed man and a nude woman in a rural setting. The man is standing to the left and gazing to the side, apparently at the woman, who is seated and breastfeeding a baby; the relationship between the two figures is unclear. In Pastoral Concert, two clothed men and a nude woman are seated on the grass, engaged in music making, while a second nude woman stands beside them.

Olympia

As he had in Luncheon on the Grass, Manet again paraphrased a respected work by a Renaissance artist in the painting Olympia (1863), a nude portrayed in a style reminiscent of early studio photographs, but whose pose was based on Titian's Venus of Urbino (1538). The painting is also reminiscent of Francisco Goya's painting The Nude Maja (1800).

Manet embarked on the canvas after being challenged to give the Salon a nude painting to display. His uniquely frank depiction of a self-assured prostitute was accepted by the Paris Salon in 1865, where it created a scandal. According to Antonin Proust, "only the precautions taken by the administration prevented the painting being punctured and torn" by offended viewers.[9] The painting was controversial partly because the nude is wearing some small items of clothing such as an orchid in her hair, a bracelet, a ribbon around her neck, and mule slippers, all of which accentuated her nakedness, sexuality, and comfortable courtesan lifestyle. The orchid, upswept hair, black cat, and bouquet of flowers were all recognized symbols of sexuality at the time. This modern Venus' body is thin, counter to prevailing standards; the painting's lack of idealism rankled viewers. The painting's flatness, inspired by Japanese wood block art, serves to make the nude more human and less voluptuous. A fully dressed black servant is featured, exploiting the then-current theory that black people were hyper-sexed.[4] That she is wearing the clothing of a servant to a courtesan here furthers the sexual tension of the piece.

Olympia's body as well as her gaze is unabashedly confrontational. She defiantly looks out as her servant offers flowers from one of her male suitors. Although her hand rests on her leg, hiding her pubic area, the reference to traditional female virtue is ironic; a notion of modesty is notoriously absent in this work. A contemporary critic denounced Olympia's "shamelessly flexed" left hand, which seemed to him a mockery of the relaxed, shielding hand of Titian's Venus.[10] Likewise, the alert black cat at the foot of the bed strikes a sexually rebellious note in contrast to that of the sleeping dog in Titian's portrayal of the goddess in his Venus of Urbino.

Olympia was the subject of caricatures in the popular press, but was championed by the French avant-garde community, and the painting's significance was appreciated by artists such as Gustave Courbet, Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet, and later Paul Gauguin.

As with Luncheon on the Grass, the painting raised the issue of prostitution within contemporary France and the roles of women within society.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère), 1882, Courtauld Gallery, London

In his last years Manet painted many small-scale still lifes of fruits and vegetables, such as Bunch of Asparagus and The Lemon (both 1880). He completed his last major work, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (Un Bar aux Folies-Bergère), in 1882, and it hung in the Salon that year. Afterwards, he limited himself to small formats. His last paintings were of flowers in glass vases.

Manet's public career lasted from 1861, the year of his first participation in the Salon, until his death in 1883. His known extant works, as catalogued in 1975 by Denis Rouart and Daniel Wildenstein, comprise 430 oil paintings, 89 pastels, and more than 400 works on paper.

The grave of Manet at Passy

Although harshly condemned by critics who decried its lack of conventional finish, Manet's work had admirers from the beginning. One was Émile Zola, who wrote in 1867: "We are not accustomed to seeing such simple and direct translations of reality. Then, as I said, there is such a surprisingly elegant awkwardness ... it is a truly charming experience to contemplate this luminous and serious painting which interprets nature with a gentle brutality."

The roughly painted style and photographic lighting in Manet's paintings was seen as specifically modern, and as a challenge to the Renaissance works he copied or used as source material. He rejected the technique he had learned in the studio of Thomas Couture – in which a painting was constructed using successive layers of paint on a dark-toned ground – in favor of a direct, alla prima method using opaque paint on a light ground. Novel at the time, this method made possible the completion of a painting in a single sitting. It was adopted by the Impressionists, and became the prevalent method of painting in oils for generations that followed. Manet's work is considered "early modern", partially because of the opaque flatness of his surfaces, the frequent sketchlike passages, and the black outlining of figures, all of which draw attention to the surface of the picture plane and the material quality of paint.

The art historian Beatrice Farwell says Manet "has been universally regarded as the Father of Modernism. With Courbet he was among the first to take serious risks with the public whose favour he sought, the first to make alla prima painting the standard technique for oil painting and one of the first to take liberties with Renaissance perspective and to offer "pure painting" as a source of aesthetic pleasure. He was a pioneer, again with Courbet, in the rejection of humanistic and historical subject-matter, and shared with Degas the establishment of modern urban life as acceptable material for high art."

Art market

The late Manet painting, Le Printemps (1881), sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum for $65.1 million, setting a new auction record for Manet, exceeding its pre-sale estimate of $25–35 million at Christie's on 5 November 2014. The previous auction record was held by Self-Portrait With Palette which sold for $33.2 million at Sotheby's on 22 June 2010.[38]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89douard_Manet

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

IMPRESIONISMO

Francia, siglo XIX: Final del clásico/Principio de lo moderno

Espontáneo, directo, personal. Luz y color real, natural

El concepto se le adjudica a Louis Leyor (1874)

Rompe la formalidad, surge en conjunto con el cine

Estilo difuminado por la luz, la composición cambia por condiciones atmosféricas e intensidad de la luz.

No importa el objeto, sino las variaciones cromáticas que este sufre a lo largo del día

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Le Bar aux Folies-Bergère, Edouard Manet, 1881-82

Le Bar aux Folies Bergère, painted and exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1882, was the last major work by French painter Édouard Manet. It depicts a scene in the Folies Bergère nightclub in Paris. It originally belonged to the composer Emmanuel Chabrier, who was Manet’s neighbor, and hung over his piano. The painting exemplifies Manet’s commitment to Realism in its detailed representation of a contemporary scene.

The painting is rich in details which provide clues to social class and milieu. The woman at the bar is a real person, known as Suzon, who worked at the Folies-Bergère in the early 1880s. For his painting, Manet posed her in his studio. By including a dish of oranges in the foreground, Manet identifies the barmaid as a prostitute, since Manet habitually associated oranges with prostitution in his paintings. Other notable details include the pair of green feet in the upper left-hand corner, which belong to a trapeze artist who is performing above the restaurant’s patrons.

The beer bottles depicted are easily identified by the red triangle on the label as Bass Pale Ale, and the conspicuous presence of this English brand instead of German beer has been interpreted as documentation of anti-German sentiment in France in the decade after the Franco-Prussian War.

Very interesting indeed.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art in the City : Paris Edition

Manet ‘Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe’ 1863 Oil on canvas

The people in the painting are art students, the naked women as once discussed before is naked not nude for the fact the painter has not idealized her in anyway for the male gaze. Speaking of gaze, the naked women is staring at the viewer, whoever that may be. Her gaze is challenging and not submissive, a classical painting with a passive women's glance witch caused outrage at the time of its creation.

Claude Monet ‘St Lazarre Railway’ 1977 Oil on canvas

Before Monet no one would have painted a railway station, at the time of this painting railway stations were a new concept. Being an impressionist painting Monet tries to emulate light and movement. Monet painted this in the station which was made possible because tubes of paint had just been manufactured at that time.

Le Banlieue ‘Banlieue Parisienne’ 1979 Photograph

Seen in this photograph is where artists went and built a community because it was extremely cheap, people that lived here consisted off painters, writers, poets and musicians among more that because of the high level of unemployment at the time allowed them a place to go.

Pierre-Anguste Renoir ‘Luncheon of the boating Party’ 1881 Oil on canvas

Renoir captured an impression in time of modern life in 1881, people who were off different social classes mingling over lunch. It is visible form the peoples clothes of which class they appear to be from, such as the men white vests will be off a lower class than the suited and booted men.

Manet ‘Bar at the Folies Bergeres’ 1882 Oil on canvas

Manet here has painting a nightclub of sorts, one not attended by high society but rather musicians and artist as well as writers would meet here. Many of the females Manet painted were in fact prostitutes, this women in this painting is believed to have been one too. Oranges in a painting depict and suggest prostitution metaphorically, because Manet has painted a bowl full of oranges alongside the lady in question it gives strong evidence to believe she was a lady of the night. However, Monet has also painted roses which signifies the lady has a sense of innocents and purity about her, the position of which Monet has placed these roses (on her chest in fact covering cleavage) supports this idea strongly. When it comes to the bar ladies gaze, she could be looking at one of two things, the gentleman who can be seen behind her in the mirror, or she could be engaging with us the viewer. Her look suggests to me a disconnection from her environment, a detachment from what is going on around her. While her eyes are challenging, she is not confrontational, she looks as if she is a product on sale.

Picasso ‘Les Demoiselles ‘Avignon’ 1907 Oil on canvas

Picasso was influenced by tribal masks from trocadero in Paris when producing this analytical cubism painting. For this painting, he reduced real life into geometrical shapes analysing the way form is depicted. Never leaving representation Picasso would always leave a link to reality.

Juan Gris ’Tabacco, newpaper and bottle of wine’ 1914 Oil

In Paris artists would more often than not meet in cafes, which sparks where the inspiration came from for this painting. The newspaper was from a cafe Gris visited, the bottle of wine that can just about be made out in the painting signifies everyday life.

Picasso ‘Two Women Running on a beach’ 1922 Oil on wood

“Two women running on a beach” is painted in a Neo classical style, people returned to painting this way after the war, as it brought them and others comfort and normality again.

Rene Magritte ‘This is not a pipe. The treachery of images’ 1928-9 Oil on canvas

The title “this is not a pipe” can be confusing when so clear as day you’re looking at a painting of a pipe. However, there is the key word “painting”, this is not a pipe, this is a painting of a pipe.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Bar At The Folies-Bergère, Édouard Manet, 1882. After viewing @andhetravels stories this last week, showing their visit to @courtauld , it reminded me of my recent whistle-stop trip to London to see my favourites galleries and exhibitions. On my blog today I have published my London diary, describing my capital excursion. Link in story/bio. ___________________________________________ #edouardmanet #abaratthefoliesbergere #thecourtauld #courtauldgallery #courtauld #art #artwork #artist #artgallery #exhibition #artmuseum #museum #galleries #exhibitions #artexhibition #postimpressionism #postimpressionist #artcollector #artcuration #london #somersethouse #strand #frenchpainter #frenchartist #modernist #modernistart #frenchmodernist #19thcentury #19thcenturyart #culture (at The Courtauld) https://www.instagram.com/p/CaNTE0GIj2h/?utm_medium=tumblr

#edouardmanet#abaratthefoliesbergere#thecourtauld#courtauldgallery#courtauld#art#artwork#artist#artgallery#exhibition#artmuseum#museum#galleries#exhibitions#artexhibition#postimpressionism#postimpressionist#artcollector#artcuration#london#somersethouse#strand#frenchpainter#frenchartist#modernist#modernistart#frenchmodernist#19thcentury#19thcenturyart#culture

0 notes

Photo

ROSES IN A CHAMPAGNE GLASS after Manet, Claude GUILLEMET

Towards the end of his life, Eugene Manet was too sick to paint major works. Instead, he painted the flowers his friends and admirers used to offer him. This one was painted in 1882.

https://www.saatchiart.com/art/Painting-ROSES-IN-A-CHAMPAGNE-GLASS-after-Manet/868422/3800737/view

0 notes

Text

Project Proposal and Research

12/5/20

Idea: Comfort food/human’s conciseness/ figural and its significance in photography

Comfort food, providing a consolation or a feeling of well-being. Everybody has their own sweet and savoury craving, wether its after a long day, a midnight snack or a Sunday morning brunch, we all have one. This personal series will undergo individuals close to me including family and friends, capturing their personality and of course their most desired comfort food. Each image will have its own uniqueness reflecting the person’s characteristics. Constructing an aesthetic series using complimentary colours and artificial lighting to capture theatrical scenes, will tie in each image all possessing the same quality and idea of an individuals own comfort food. I believe this concept connects very nicely to project three, as I will be undergoing this notion of the figural. Figural being a form of significance which relies on imagery and association, capturing symbolic meaning in ones person life. Inspired by Anne Hardy and Henry Hargreaves, and their ability to capture empty spaces and aesthetic foods, still possessing this notion of the lack of human body except its clear that their soul and presence still remain in the image. This feeling of emotion is what I would like to portray and capture in my series.

Journal Articles

The Chicago School of Media Theory: Figurative/Figural

Theorist Micheal Fried, explores the relationship between the figure and literal within the modern art world.

Fried’s understanding of the modern age, views art as literalist and minimalist, suggesting that the whole work “they are what they are nothing more” than shapes, colour and form.

Literal can be seen and used as a metaphor

The introducing of anthropomorphism can be only depended on literalist art once a person seeks a hidden meaning.

Anthropomorphism can be seen as a symbol seen from a singles of a shape.

Literalist art proclaims its object hood

Referring back to literal and the figure, Fried suggest that literalist art is almost seen as non-art because it rejects the representation of art that calls the attention to in the term figure.

The status of an object within Literalist works are further emphasised between the relationship of the view to the artwork in space.

Fried draw attentions around the dichotomy betwen the liter and the furfural and figurative, as he further implies the way in which these dichotomy dissipated within the modern art movement.

Identifying the figure and the literal, yes photography can be seen very literal as we capture something that is clearly identified by all. However once the audience starts to connect the dots (anthropomorphism) thats when the image itself creates it’s own meaning and symbolism.

https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/figurativefigural/

Comfort Food: Nourishing Our Collective Stomachs and Our Collective Minds by Jordan D. Troisi1 and Julian W. C. Wright1

Food is a powerful motivator in human functioning—it serves a biological need, as emotional support, and as a cultural symbol.

Comfort food in the media is seem as unhealthy, often consumed in moments of stress or sadness

But for anyone who has a love of food and of eating, it will come as no surprise that food also has emotional, cultural, and symbolic mean- ing as well.

Food satisfies our collective minds

Comfort food serve as a memory based link to close others and that those with secure attachment styles would have favorable associations with foods associated with other people.

This article provides information on how society identifies comfort as it can be seen through two perspective, as stress eating (unhealthy food) causing anxiety and is something tradi- tional, cultural, regional, familial, or otherwise imbued with meaning

Eating is the perfect social psychological variable, because it is connected to almost every social variable or process you can think of! (Herman, as cited in Baumeister & Bushman, 2014, p. xxi)

Given the need for humans to consume food in order to maintain numerous homeostatic processes, such topics also seem relevant for courses in biopsychology. Furthermore, there is clear evidence that stressful experiences have numerous bio- logical implications.

This article provides insight on what comfort can really represent for ones individual - it’s a guilty pleasure meal that is close to their hearts. It can be something that endure and crave if feeling overwhelmed or stress which is why some may seem to be fatty and fills with sugar and oil however comfort food isn’t always seen as that. It possess cultural aspects and symbolises their homes - when feeling home sick.

https://journals-sagepub-com.ezproxy2.library.usyd.edu.au/doi/pdf/10.1177/0098628316679972

Artists of Inspiration

Through my online journal I have briefly discussed Anne Hardy and Henry Hargreaves, both strongly influencing me for my idea for project three. I have also done research of artist Jeff Wall. I will be elaborating further below on what aspect of these artists works have influenced me and how I will use this to create a capture my own innovative series.

Anne Hardy

Hardy’s work transforms sculpture into photographic ‘paintings’. Though her scenes are built in actuality, their compositions are developed to be viewed from one vantage point only and it’s only their 2 dimensional images that are shown. Hardy uses the devices inherent within photography to heighten her work’s painterly illusion. In Cipher, aspects such as the hazy aura around the fluorescent lights, faux grotto walls, and the spatial defiance of the hanging ropes, give allusion to gesture and drawn lines.

‘Cipher’ 2007

Henry Hargreaves

Photographer Henry Hargreaves and installation artist Nicole Heffron have spent the past year imaging how famous directors might celebrate their birthdays in order to recreate the scenes for a unique photo series. Pictured: The bloodied samurai sword suggests that this cake was intended for Kill Bill director Quentin Tarantino

The image of the staircase on this birthday cake suggests that this birthday cake was intended for the Vertigo director Alfred Hitchcock

The bear-shaped cake here is an instant giveaway that this is the birthday cake of Ted director Seth Macfarlane

The glass of milk in this set up is a subtle suggestion that this sterile birthday is that of the Clockwork Orange director Stanley Kubrick

The scene at Martin Scorsese's knees-up has elements of New York's Little Italy as well as the gambling and cigars of Casino and his first hit Mean Streets

John Waters' identity is given away by his Pink Flamingos cake, a reference to the title of the 1972 movie starring drag queen Divine

What I love the most of Hargreaves food images is how he can create these bloody to half eaten food scenes look so pleasing to the eye even when it should make you feel a little gross out. Food photography I feel is very difficult to capture and the same goes in films. It’s so easy for people to be gross out by them especially when their hands and mouths involved, however Hargreaves manages to create these aesthetic food series, almost making me hungry and wanting to eat those cakes. Hargreaves has inspired in the past with previous food photographs, and he still manages to continue to inspire me now. His work is so intriguing and the use of colour and composition overall ties in the image very nicely. However, instead of capturing celebrities and prisoners on death row, for my own work I want it to be personal. Using the pope around me such as family and friends and capture what their own comfort food is their favourite and what it means to them. Is it a stress comfort food or is something that reminds them of home, child hood or a distant memory. Even for myself and capturing my own comfort food and exploring why I have chosen that specific meal. I believe exploring on this idea of food and the figural, it will ultimately challenge me, and let me undergo such research and even an experience of capturing something more than just a photograph of food but the human soul behind that.

Jeff Wall

I begin by not photographing.

—Jeff Wall

This quote really speaks to me on what art really means to myself. I believe their is so much more than just taking a photo. Behind the scenes artists have to create this ideal image before capturing the photo itself. I love constructing and forming this perfect composition in my mind and capturing it with a camera allows that form to last forever however just creating art itself bringing forth this new world of what photography can really say.

Jeff Wall’s work synthesizes the essentials of photography with elements from other art forms—including painting, cinema, and literature—in a complex mode that he calls “cinematography.” His pictures range from classical reportage to elaborate constructions and montages, usually produced at the larger scale traditionally identified with painting

Some of Wall’s early pictures evoke the history of image making by overtly referring to other artworks: The Destroyed Room (1978) explores themes of violence and eroticism inspired by Eugène Delacroix’s monumental painting The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), while Picture for Women (1979) recalls Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) and brings the implications of that famous painting into the context of the cultural politics of the late 1970s. These two pictures are models of a thread in Wall’s work that the artist calls “blatant artifice”: pictures that foreground the theatricality of both their subject and their production. Dead Troops Talk (1991–92), a large image depicting a hallucinatory moment from the Soviet war in Afghanistan, is a central example, and was one of the first works to employ digital-imaging technology, which has since transformed the landscape of photography. Wall was a pioneer in exploring this dimension and remains at the forefront of its development.

Doing research on Wall and his work, it’s clear he really wants to capture these somewhat candid images however, behind these image unfold stories and visions. His work in a way have these capturing aesthetic scenes that drawn the audience in. It creates a sense of narrative and story lines by one single picture. I did find the “Destroyed Room” to be very fascinating and it held many similarities on what I wanted to create. However after viewing his other works I couldn’t help but be intrigued by his image “Changing Room”, the image itself look as if it’s some kind of painting. I think it also ties in with this theme figure and figural topic. The top half of the body looks as if it's some kind of bird especially the animal pattern on the fabric. However, on the bottom half it’s clear that a women is simply just getting change. The figure itself seems to be part human and animal, thats how I view the image as a whole. And I do believe thats what Wall was trying to capture this weirdly human figure or it could have been by accident of the lady putting the shirt or another from of dress and it just seemed as if it was a bird. Overall Wall’ work is absolutely amazing, it has this sense of allude affect on the scenes, drawing myself within the images, trying to figure this narrative by just viewing one image. I wanna be able to incorporate this whole emotional effect on my own images and creating this sense of narrative.

200 word Project Proposal

Looking at a variety of artists and articles surrounding this whole notion of the figural within art has allowed me to compose a solid idea of what I will be exploring within project 3. Comfort food is known for providing a consolation or a feeling of well-being. Reading 'Comfort Food: Nourishing Our Collective Stomachs and Our Collective Minds’ it provides insight into what comfort food really means for an individual. It can be seen through two perspectives, including stress and anxiety eating, this makes people crave more unhealthy sugary or high fat food, or is something tradi- tional, cultural, regional, familial, or otherwise imbued with meaning to an individual. Gathering both research on the figural/literal themes within art and this whole concept of comfort food, I believe both have similar qualities and can be captured in a unique form. Wanting to approach this project in a more personal outlook, I will be exploring and capturing my friends and families own comfort food and what it means to them. I will also be using myself and my own desired comfort food, to explore and ask questions what makes comfort food comfort?. Inspired by Anne Hardy, Jeff Wall and Henry Hargreaves, each artists has provided a source of inspiration that I will be incorporating within my own work, however still creating an innovative personal series of my own.

0 notes

Text

History and Theory of Art as Method

It’s pretty obvious that art has changed over time. There have been too many movements to count, arguments over order, influence and pioneers of each artistic style. But these art movements and historical events have a large impact on the photographic world also. What painters are doing at the time, can mimic or differ completely from what photographers are doing. It would be naive to say that photographers and artists are separate beings, as a large majority of well known artists work in multiple mediums. Therefore, a knowledge of what is happening in art must have an influence over photographic style.

Jeff Wall, for example, when you look at their work there are clear references to art, even if you don’t have an extensive knowledge of art history and movements. His photograph ‘A sudden gust of wind’ (1993) mimics the work from Hokusai, with the graceful composition of floating papers, the vast landscape and event the posture of the people and tree in the foreground.

[Above] A Sudden Gust of Wind (After Hokusai), Jeff Wall (1993)

[Below] Travellers Caught in a Sudden Gust of Wind, Hokusai (1832)

Jeff Wall is a photographer that took art as a significant reference for his work frequently. It can also be seen in his image ‘Picture for Women’ from 1979. It references Manet’s painting ‘A bar at the Folies-Bergère’, which has many significant references to the class system within society in the 19th Century, and the role of women at the time also. Wall’s image can be methodised using Art theory, with obvious reference to Manet’s painting, but also can be analysed using a feminist theory or gender theory, as he begs the viewer to re-analyse the way women are seen within art. By taking a historical painting and recreating it in a contemporary setting, it asks for the viewer to create comparisons between the two.

[Above] Picture for Women, Jeff Wall (1979)

[Below] A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, Édouard Manet (1882)

0 notes

Text

HISTORY OF ART

ART IN PARIS

29.10.19

Julie started by giving us some advice on the academic poster due in December. The poster needs to answer the question, "how did [city] inspire [artist/movement]?" The city and artist/movement is for us to choose.

This week, we're focussing on how Paris inspired the impressionists, and how Paris supported the development of surrealism.

We were shown Manet's ‘Le Dejeuner Sur L'Herbe’, 1863. This painting was "pivotal" at the time, as artists no longer wanted to be dictated by the academy. The piece challenges the male gaze, by the woman looking directly at the audience, almost in a confrontational way. Despite being naked, she's not uncomfortable, and doesn't appear to be listening to the scholars she's sat with. This piece was rejected from The Paris Salon due to being "scandalous." They didn't like the male gaze being challenged. Due to this, Manet agreed to exhibit it at Salon des Refusés, a salon for rejected works.

Claude Monet's 'St Lazarre Railway, 1877, was also shown. This piece was an impressionism piece, portraying real, modern life. Again, linking to normal life being intergrated into art.

We also looked at female artist, Mary Cassatt's 'In the Loge', 1878. This also challenged the male gaze, showing a woman watching a show or the opera, and a man with binoculars in the background watching the woman instead. Julie also highlighted the "barrier" represented through the balcony's edge. These barriers shown the wall created between women and where they wanted to be. Male artists could access these places, such as cafes, bars and clubs, whereas women were expected to stay at home.

Renoir 'Luncheon of the Boating Party', 1881, again, shown ordinary people living normal life. It's believed that this was painted without an underdrawing, common amongst impressionism. I really love this painting and the vibrancy captured of the lunch time.

Manet's 'Bar at the Folies Bergers', 1882, features a woman stood behind a bar, with a challenging gaze. In the background, there's a mirror, and you can see that she's looking at a man. It's like she's challenging the audience, as we feel as if we're in the place of the man. There's oranges in frame, symbolising prostitution, and Julie told us there was 20k prostitutes in Paris at the time.

We also looked at Picasso's 'Les Demoiselles', 1907. This is an early cubism piece, featuring motifs of colonial activity. You can see the inspiration from tribal masks in Trocadero, Paris. The piece was seen as something to be questioned, and was "lacking perspective", making "real perspective" a thing of the past, with artists now investigating new dimensions.

After the war, lots of artists died, and there was a "return to order." Art work regressed back, and became less challenging again, seen in Picasso's 'Two Women Running on The Beach' and 'Seated Harlequinn', 1922+23. Following this, surrealism began, inspired by the horrors of the war and psychoanalysis therapy. This was also "the time of panphlets", beginning the "surrealism revolution."

Salvador Dali's 'Apparition of a Face', 1937, is open for interpretation. It's not a logical piece, and is about dreams making it quite random. It's like an optical illusion, with people seeing different things within it. I really liked this piece, there's a lot going on in it but I think my favourite part is the central face.

We were also shown some examples of posters to inform us on ways to make our own. I already think I want to do mine about New York and pop art, as it's quite similar to my style in terms of colour, and the boldness of it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

OCTOBER IN SAN FRANCISCO...

My friend and muse OCTOBER from the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts seems to enjoy San Francisco where she is participating at a special event about her creator JAMES TISSOT « FASHION AND FAITH » at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco (Legion of Honor)

My dear OCTOBER should be back in Montreal next spring 2020 as the exhibition will end on February 9.

I cannot wait for her return...

REVIEW

James Tissot: « Fashion & Faith«

More Than Pretty People?

By THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Tissot, often dismissed as a society painter, gets a reappraisal at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor.

Ruffles and flourishes: James Tissot (1836-1902) was a master of them. In his meticulous, highly detailed paintings, ladies and gentlemen of the late 19th century sip tea, stroll, dance, eat and pose, almost always dressed to the nines. Tissot amplified the glamor of their clothing and the luxuriance of their surroundings to make such pretty pictures. They were popular in London and Paris in his lifetime and prized by American collectors well into the latter half of the 20th century.

But was Tissot more than a fussy society painter? Many critics, then and now, think not. “James Tissot: Fashion & Faith” at the Legion of Honor takes a different stance. Informed by new scholarship, curator Melissa E. Buron, with colleagues at the Musée d’Orsay and the Orangerie in Paris, proposes a more complex view of an artist who famously turned down Edgar Degas’s invitation to join the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, possibly because he was more famous than they were. How times change.

Tissot’s extraordinary artistic talent is obvious in the 70 paintings and other objects on view. The stunning “October” (1877), which opens the exhibition, is quintessential Tissot: it shows his lover and muse, Kathleen Newton, in an exquisite black, fur-trimmed, embroidered jacket and ruffled skirt, walking along a golden autumnal trail. His focus on high-style and his precision with the brush is even more clear in exuberant works like “Painters and Their Wives” (c. 1883-85), a dense outdoor café scene celebrating “Varnishing Day” before the annual Paris Salon.

Perhaps more captivating than his genre scenes are Tissot’s portraits—especially “Portrait of Mlle L. L...” (1864). Set in a room that is more homey than elegant, it shows her in billowing black dress and red bolero, meeting the viewer’s gaze, and led to several commissions, including formal group portraits like “Portrait of the Marquis and Marquise de Miramon and Their Children” (1865).

It’s also obvious from “Fashion & Faith” that Tissot’s art reflects his biography. He grew up in Nantes, in northwest France, the son of a textile merchant and a milliner with her own hat shop—steeped not only in fashion but also in market trends. As a young artist, he absorbed medieval, neoclassical and academic traditions, then flirted with history painting, Japonisme and aestheticism. He served as a sharpshooter during the Franco-Prussian War.

He also knew many artistic peers in France and England, and their influence is unambiguous—with his “The Thames” (1875) and “Holyday (The Picnic)” (c. 1876) recalling Manet, “The Two Sisters; Portrait” (1863) conjuring Whistler, and other works drawing on Sargent, to name a few examples.

Yet unlike theirs, Tissot’s art stayed within the lines. And, in contrast to the social tensions in many of their works, Tissot’s subjects seem slight.

But they were not necessarily vacuous, as critics have claimed: “Fashion & Faith” recasts Tissot as a storyteller whose narratives deal with human relationships beneath their decorous surfaces. There’s the poor wallflower in “The Ball on Shipboard” (c. 1874) and the boy whose marriage offer was refused in “The Captain’s Daughter” (1873). In “Too Early” (1873), a man and his three daughters embarrassingly appear at a ball prematurely, so nouveau—a theme he reprised in “Provincial Woman” (c. 1883-85), where the same overly ruffled quartet has grown older, but not wiser.

Likewise, Tissot’s deep love for Newton is conspicuous. Aside from “October,” she is the beautiful woman in the spectacular “Winter or Mavourneen” (1877), where she stands in near silhouette against a window, looking away, and in the striking “Mrs. Newton with a Parasol” (c. 1878), among others. When she was stricken with tuberculosis, he records her decline, ending with the poignant “Summer Evening” or “The Dreamer” (c. 1881-82), which shows her near death.

The day after her funeral in 1882, Tissot left London, after 11 years there, for France, and by 1885 had begun a new chapter—the “Faith” of this exhibition. Attempting to contact Newton in the afterlife, he took up spiritualism, producing a strange, atmospheric painting, “The Apparition” (1885), which until this exhibition was thought to be lost (though it is familiar from prints he made of it). It shows a shrouded Newton, aglow with inner light, guided by a medium.

At the same time, Tissot rekindled his Christian faith, transformed by a vision he experienced at the Church of Saint-Sulpice. He focused the rest of his life on religious images, making hundreds of sketches and watercolors chronicling the life of Christ, many published in his illustrated New Testament, a 1903 copy of which is on display. Later, he turned his attention to the Old Testament.

A gallery of these images—articulate, precise, sometimes stirring—ends the exhibition. They were warmly received in Europe and in the United States, bringing Tissot wider fame and more fortune. They may be the most influential part of Tissot’s oeuvre, as their sequential nature inspired early filmmakers and his images affected more recent ones, too, such as William Wyler in “Ben-Hur.”

“Faith & Fashion” surely deepens our understanding of Tissot, and it may convince some visitors that he is underestimated. Still I suspect that for many he may remain just a virtuoso with the brush. And what’s wrong with that?

—Ms. Dobrzynski writes about culture for the Journal and other publications.

1 note

·

View note