#1880 Republican National Convention

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Which President, in your opinion, was the most reluctant to seek the position? Which wound up hating it the most by the end of his term?

I am a strong believer that nobody truly becomes President of the United States "reluctantly". That's not exactly the kind of job that seeks you, especially the modern Presidency.

For a significant slice of American history, many of the people nominated for President acted as if they were being called upon to run when, behind-the-scenes, they were very active in building their campaigns and corralling supporters. Until the 20th Century it was frowned upon to openly run for the Presidency, but almost all of the Presidents wanted the gig.

I'd say that George Washington was probably more reluctant than most of his successors and likely would have preferred retiring to Mount Vernon after the Revolution, but I think he also recognized that he was the guy who needed to be the President that set the precedents. I think Ulysses S. Grant would have been perfectly happy to not be President, but once he was elected in 1868 he also wanted to keep the job. He even tried to run for a third term in 1880.

That 1880 election might have been the one case where the winner -- James Garfield -- genuinely wasn't interested in the Presidency at that point. He had gone to the Republican National Convention to support fellow Ohioan John Sherman (and defeat Grant's hopes for a third term) and gained some major attention after giving a well-received speech placing Sherman's name in nomination. When the candidacies of Sherman and James G. Blaine -- another anti-Grant candidate -- stalled, Garfield became a compromise choice and was eventually nominated on the 36th ballot. Garfield was apparently legitimately shocked by the events leading to him leaving Chicago as the GOP nominee.

By most accounts, William Howard Taft was far more interested in a potential seat on the Supreme Court than becoming President. At heart he was a judge and believed himself to be better suited for the judiciary than the Executive Branch. But Taft turned down three offers by Theodore Roosevelt to be appointed to the Supreme Court (in 1902, 1903, and 1906) because he felt obligated to complete his work as Governor-General of the Philippines and then Secretary of War. But Taft's wife desperately wanted him to become President and by the time of President Roosevelt's third offer of a seat on the Court, Taft was already being talked about as Roosevelt's hand-picked successor in the White House. And, as with all other Presidents, once he had a taste for the job, he didn't want to give it up, running for re-election in 1912 against his former friend, Roosevelt.

Gerald Ford is the only other President who hadn't spent a significant portion of his political career with his eyes on the White House. Ford spent nearly a quarter-century in the House of Representatives and his main ambition was to be Speaker of the House, but Republicans weren't able to win control of the House when Ford was in Congressional leadership positions. But even with Ford being a creature of Congress, he did attempt to put himself forward as a nominee for the Vice Presidency, first in 1960 and then in 1968, and Nixon kicked the tires on picking him as his running mate in 1960. No one wants to be Vice President without seeing it as a potential stepping stone to the Presidency, particularly at that point in history before Vice Presidents were empowered with some real influence within the Administrations they served in.

As for who wound up hating it by the end of their time in office, I think it's safe to say that John Quincy Adams didn't shed too many tears when he was defeated for re-election in 1828. And I'm sure he wouldn't use the word "hate", but nobody can convince me that George W. Bush wasn't thoroughly ready to escape Washington by late-2007. There were times in 2008 when he seemed like he just wanted to hold a snap election like they have in parliamentary systems and go home to Texas. If some Presidential insider published a book that said that Bush asked if he could just give the keys to the White House to Barack Obama in July 2008, I wouldn't be the least bit shocked.

On the other hand, if there were no term limits, Bill Clinton would have been running for President in every election since 1992 (and the crazy thing is that he's still younger than both of the presumptive 2024 nominees). I'm kind of surprised that he didn't make an effort to repeal the 22nd Amendment in the past 20 years. Clinton loved being President and was trying to find something Presidential to do until minutes before his successor was inaugurated in 2001.

#History#Presidents#Presidential Candidates#Presidential Nominees#Presidential Elections#Presidency#Reluctant Presidents#Politics#Political History#Presidential History#George Washington#President Washington#General Washington#Ulysses S. Grant#President Grant#General Grant#1880 Election#1880 Republican National Convention#James Garfield#President Garfield#William Howard Taft#President Taft#Chief Justice Taft#Gerald Ford#President Ford#John Quincy Adams#JQA#President Adams#George W. Bush#Bush 43

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you happen to know how often it occurred for wives of arrested deputies to share the same fate of their husbands, so either imprisoned, or condemned to death ? Do you have some examples? I'm referring to the years between 92-95. Moreover if it's not too much to ask for, could you also point out the signature of the CSP members who signed such warrants?

That’s a very interesting question, especially since no official studies seem to have been made on the subject. What I’ve found so far (and it wouldn’t surprise me if there’s way more) is:

Félicité Brissot — after the news of her husband’s arrest, Félicité, who had lived in Saint-Cloud with her three children since April 1793, traveled to Chartres. There (on an unspecified date?) she and her youngest son Anacharsis (born 1791) were arrested by the Revolutionary Committee of Saint-Cloud (the two older children had been taken in by other people) which sent her to Paris. Once arrived in the capital, Felicité was placed under surveillance in the Necker hotel, rue de Richelieu, in accordance with an order from the Committee of General Security dated August 9 1793 (she could not be placed under house arrest in her own apartment, since seals had already been placed on it). On August 11 she underwent an interrogation, and on October 13, she was sent from her house arrest (where she had still enjoyed a relative liberty) to the La Force prison. Félicité and her son were set free on February 4 1794, after six months spent under arrest. The order for her release was it too issued by the Committee of General Security, and signed by Lacoste, Vadier, Dubarran, Guffroy, Amar, Louis (du Bas-Rhin), and Voulland. Source: J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912) by Claude Perroud)

Suzanne Pétion — In a letter to the Convention dated July 26 1793, Carrier reports that ”Péthion's [sic] wife, their son and the wife of another fugitive, were arrested in Homfleurs, we are going to take them to Paris.” On August 9, we find a CGS decree ordering Suzanne and her ten year old son, for the moment under house arrest, to be taken to the Sainte-Pélagie prison. Ten days after that, August 19, the CGS orders the furniture in Suzanne’s apartment to be brought over to her. A year later, August 13 1794, we find a letter from Suzanne to the Committee of Public Safety pleading for the release of her and her son, imprisoned only for sharing the name of a proscribed deputy. But this would appear to have lead nowhere, and the two were instead transported from the Sainte-Pélagie prison to the Maison Desnos. Finally, on December 9 1795, after one year, four months and thirteen days imprisoned, a CGS decree with the signatures of Mathieu, Reverchon, Bourdon, Montmayou, Barras and Comorel on it ordered Suzanne and her son released and their seals lifted immediately.

Louise-Catherine-Àngélique Ricard, widow Lefebvre (Suzanne Pétion’s mother) — According to Histoire du tribunal révolutionnaire de Paris: avec le journal de ses actes (1880) by Henri Wallon, Louise was called before the parisian Revolutionary Tribunal on September 24 1793, accused “of having applauded the escape of Minister Lebrun by saying: “So much the better, we must not desire blood,” of having declared that the Brissolins and the Girondins were good republicans (“Yes,” her interlocutor replied, “once the national ax has fallen on the corpses of all of them”), for having said, when someone came to tell her that the condemned Tonduti had shouted “Long live the king” while going to execution; that everyone would have to share this feeling, and that for the public good there would have to be a king whom the “Convention and its paraphernalia ate more than the old regime”. She denied this when asked about Tonduti, limiting herself to having said: “Ah! the unfortunate.” Asked why she had made this exclamation she responded: ”through a sentiment of humanity.” She was condemned and executed the very same day.

Marie Anne Victoire Buzot — It would appear she was put under house arrest, but was able to escape from there. According to Provincial Patriot of the French Revolution: François Buzot, 1760–1794 (2015) by Bette W. Oliver, ”[Marie] had remained in Paris after her husband fled on June 2 [1793], but she was watched by a guard who had been sent to the Hôtel de Bouillon. Soon thereafter, Madame Buzot and her ”domestics” disappeared, along with all of the personal effects in the apartment. […] Madame Buzot would join her husband in Caen, but not until July 10; and no evidence remains regarding her whereabouts between the time that she left Paris in June and her arrival in Caen. At a later date, however, she wrote that she had fled, not because she feared death, but because she could not face the ”ferocious vengeance of our persecutors” who ignored the law and refused ”to listen to our justification.” I’ve unfortunately not been able to access the source used to back this though…

Marie Françoise Hébert — arrested on March 14 1794, presumably on the orders of the Committee of General Security since I can’t find any decree regarding the affair in Recueil des actes du Comité de salut public. Imprisoned in the Conciergerie until her execution on April 13 1794, so 30 days in total. See this post.

Marie Françoise Jos��phine Momoro — imprisoned in the Prison de Port-libre from March 14 to May 27 1794 (2 months and 13 days), as seen through Jean-Baptiste Laboureau’s diary, cited in Mémoires sur les prisons… (1823) page 68, 72, 109.

Lucile Desmoulins — arrested on April 4 1794 according to a joint order with the signatures of Du Barran (who had also drafted it) and Voulland from the CGS and Billaud-Varennes, C-A Prieur, Carnot, Couthon, Barère and Robespierre from the CPS on it. Imprisoned in the Sainte-Pélagie prison up until April 9, when she was transferred to the Conciergerie in time for her trial to begin. Executed on April 13 1794, after nine days spent in prison. See this post.

Théresa Cabarrus — ordered arrested and put in isolation on May 22 1794, though a CPS warrant drafted by Robespierre and signed by him, Billaud-Varennes, Barère and Collot d’Herbois. Set free on July 30 (according to Madame Tallien : notre Dame de Thermidor from the last days of the French Revolution until her death as Princess de Chimay in 1835 (1913)), after two months and eight days imprisoned.

Thérèse Bouquey (Guadet’s sister-in-law) — arrested on June 17 1794 once it was revealed she and her husband for the past months had been hiding the proscribed girondins Pétion, Buzot, Barbaroux, Guadet and Salles. She, alongside her husband and father and Guadet’s father and aunt, were condemned to death and executed in Bordeaux on July 20 1794. Source: Paris révolutionnaire: Vieilles maisons, vieux papiers (1906), volume 3, chapter 15.

Marie Guadet (Guadet’s paternal aunt) — Condemned to death and executed in Bordeaux on July 20 1794, alongside her brother and his son, the Bouqueys and Xavier Dupeyrat. Source: Charlotte Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel.

Charlotte Robespierre — Arrested and interrogated on July 31 1794 (see this post). According to the article Charlotte Robespierre et ses amis (1961), no decree ordering her release appears to exist. In her memoirs (1834), Charlotte claims she was set free after a fortnight, and while the account she gives over her arrest as a whole should probably be doubted, it seems strange she would lie to make the imprisonment shorter than it really was. We know for a fact she had been set free by November 18 1794, when we find this letter from her to her uncle.

Françoise Magdeleine Fleuriet-Lescot — put under house arrest on July 28 1794, the same day as her husband’s execution. Interrogated on July 31. By August 7 1794 she had been transferred to the Carmes prison, where she the same day wrote a letter to the president of the Convention (who she asked to in turn give it to Panis) begging for her freedom. On September 5 the letter was sent to the Committee of General Security. I have been unable to discover when she was set free. Source: Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan, etc. supprimés ou omis par Courtois. précédés du Rapport de ce député à la Convention Nationale, volume 3, page 295-300.

Françoise Duplay — a CGS decree dated July 27 1794 orders the arrest of her, her husband and their son, and for all three to be put in isolation. The order was carried out one day later, July 28 1794, when all three were brought to the Pélagie prison. On July 29, Françoise was found hanged in her cell. See this post.

Élisabeth Le Bas Duplay — imprisoned with her infant son from July 31 to December 8 1794, 4 months and 7 days. The orders for her arrest and release were both issued by the CGS. See this post.

Sophie Auzat Duplay — She and her husband Antoine were arrested in Bruxelles on August 1 1794. By October 30 the two had been transferred to Paris, as we on that date find a letter from Sophie written from the Conciergerie prison. She was set free by a CPS decree (that I can’t find in Recueil des actes du Comité de salut public…) on November 19 1794, after 3 months and 18 days of imprisonment. When her husband got liberated is unclear. See this post.

Victoire Duplay — Arrested in Péronne by representative on mission Florent Guiot (he reveals this in a letter to the CPS dated August 4 1794). When she got set free is unknown. See this post.

Éléonore Duplay — Her arrest warrant, ordering her to be put in the Pélagie prison, was drafted by the CGS on August 6 1794. Somewhere after this date she was moved to the Port-Libré prison, and on April 21 1795, from there to the Plessis prison. She was transfered back to the Pélagie prison on May 16 1795. Finally, on July 19 1795, after as much as 11 months and 13 days in prison, Éléonore was liberated through a decree from the CGS. See this post.

Élisabeth Le Bon — arrested in Saint-Pol on August 25 1794, ”suspected of acts of oppression” and sent to Arras together with her one year old daughter Pauline. The two were locked up in ”the house of the former Providence.” On October 26, Élisabeth gave birth to her second child, Émile, while in prison. She was released from prison on October 14 1795, four days after the execution of her husband. By then, she had been imprisoned for 1 year, 1 month and 19 days. Source: Paris révolutionnaire: Vieilles maisons, vieux papiers (1906), volume 3, chapter 1.

#frev#french revolution#madame roland is of course here too but she might go in the notlikeothergirls camp in this particular instance#félicité brissot#suzanne pétion#éléonore duplay#élisabeth lebas#charlotte robespierre#théresa cabarrus#lucile desmoulins#marie françoise hébert#everyone: is held in prison from anything from two months to a whole year if not executed before then#charlotte: two weeks…#i mean i’m not surprised but…

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steve Brodner

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

July 24, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

JUL 25, 2024

Tonight, President Joe Biden explained to the American people why he decided to refuse the 2024 Democratic presidential nomination and hand the torch to Vice President Kamala Harris.

Speaking from the Oval Office from his seat behind the Resolute Desk, a gift from Queen Victoria to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880, Biden recalled the nation’s history. He invoked Thomas Jefferson, who wrote the Declaration of Independence; George Washington, who “showed us presidents are not kings”; Abraham Lincoln, who “implored us to reject malice”; and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who “inspired us to reject fear.”

And then he turned to himself. “I revere this office, but I love my country more,” he said. “It’s been the honor of my life to serve as your president.” But, he said, the defense of democracy is more important than any title, and democracy is “larger than any one of us.” We must unite to protect it.

“In recent weeks, it has become clear to me that I need to unite my party in this critical endeavor,” he said. “I believe my record as president, my leadership in the world, my vision for America’s future, all merited a second term. But nothing, nothing can come in the way of saving our democracy. That includes personal ambition. So I’ve decided the best way forward is to pass the torch to a new generation. It’s the best way to unite our nation.”

There is “a time and a place for long years of experience in public life,” Biden said. “There’s also a time and a place for new voices, fresh voices, yes, younger voices. And that time and place is now.”

Biden reminded listeners that he is not leaving the presidency and will be continuing to use its power for the American people. In outlining what that means, he summed up his presidency.

For the next six months, he said, he will “continue to lower costs for hard-working families [and] grow our economy. I will keep defending our personal freedoms and civil rights, from the right to vote to the right to choose. I will keep calling out hate and extremism, making it clear there is…no place in America for political violence or any violence ever, period. I’m going to keep speaking out to protect our kids from gun violence [and] our planet from [the] climate crisis.”

Biden reiterated his support for his Cancer Moonshot to end cancer—a personal cause for him since the 2015 death of his son Beau from brain cancer—and says he will fight for it, (although House Republicans have recently slashed funding for the program). He said he will call for reforming the Supreme Court “because this is critical to our democracy.”

He promised to continue “working to ensure America remains strong, secure and the leader of the free world,” and pointed out that he is “the first president of this century to report to the American people that the United States is not at war anywhere in the world.” He promised to continue rallying a coalition of nations to stop Putin’s attempt to take over Ukraine, and vowed to continue to build the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). He reminded listeners that when he took office, the conventional wisdom was that China would inevitably surpass the United States, but that is no longer the case, and he said he would continue to strengthen allies and partners in the Pacific.

Biden promised to continue to work to “end the war in Gaza, bring home all the hostages and bring peace and security to the Middle East and end this war,” as well as “to bring home Americans being unjustly detained all around the world.”

The president reminded people how far the nation has come since he took office on January 20, 2021, a day when, although he didn’t mention it tonight, he went directly to work after taking the oath of office. “On that day,” he recalled, “we…stood in a winter of peril and winter of possibilities.” The United States was “in the grip of the worst pandemic in the century, the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, the worst attack on our democracy since the Civil War.” But, Biden said, “We came together as Americans. We got through it. We emerged stronger, more prosperous and more secure.”

“Today we have the strongest economy in the world, creating nearly 16 million new jobs—a record. Wages are up, inflation continues to come down, the racial wealth gap is the lowest it’s been in 20 years. We are literally rebuilding our entire nation—urban, suburban and rural and tribal communities. Manufacturing has come back to America. We are leading the world again in chips and science and innovation. We finally beat Big Pharma after all these years to lower the cost of prescription drugs for seniors…. More people have health care today in America than ever before.” Biden noted that he signed the PACT Act to help millions of veterans and their families who were exposed to toxic materials, as well as the “most significant climate law…in the history of the world” and “the first major gun safety law in 30 years.”

The “violent crime rate is at a 50-year low,” he said, and “[b]order crossings are lower today than when the previous administration left office. I’ve kept my commitment to appoint the first Black woman to the Supreme Court of the United States of America. I also kept my commitment to have an administration that looks like America and [to] be a president for all Americans.”

Then Biden turned from his own record to the larger meaning of America.

“I ran for president four years ago because I believed…that the soul of America was at stake,” he said. “America is an idea. An idea stronger than any army, bigger than any ocean, more powerful than any dictator or tyrant. It’s the most powerful idea in the history of the world.”

“We hold these truths to be self-evident,” he said. “We are all created equal, endowed by our creator with certain inalienable rights: life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness. We’ve never fully lived up to…this sacred idea—but we’ve never walked away from it either. And I do not believe the American people will walk away from it now.

“In just a few months, the American people will choose the course of America’s future. I made my choice…. “[O]ur great vice president, Kamala Harris… is experienced, she is tough, she is capable. She’s been an incredible partner to me and a leader for our country.

“Now the choice is up to you, the American people. When you make that choice, remember the words of Benjamin Franklin hanging on my wall here in the Oval Office, alongside the busts of Dr. [Martin Luther] King and Rosa Parks and Cesar Chavez. When Ben Franklin was asked, as he emerged from the [constitutional] convention…, whether the founders [had] given America a monarchy or a republic, Franklin’s response was: ‘A republic, if you can keep it.’... Whether we keep our republic is now in your hands.”

“My fellow Americans, it’s been the privilege of my life to serve this nation for over 50 years,” President Biden told the American people. “Nowhere else on Earth could a kid with a stutter from modest beginnings in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and in Claymont, Delaware, one day sit behind the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office as the president of the United States, but here I am.

“That’s what’s so special about America. We are a nation of promise and possibilities. Of dreamers and doers. Of ordinary Americans doing extraordinary things. I’ve given my heart and my soul to our nation, like so many others. And I’ve been blessed a million times in return with the love and support of the American people. I hope you have some idea how grateful I am to all of you.

The great thing about America is, here kings and dictators do not rule—the people do. History is in your hands. The power’s in your hands. The idea of America lies in your hands. You just have to keep faith—keep the faith—and remember who we are. We are the United States of America, and there is simply nothing, nothing beyond our capacity when we do it together. So let’s act together, [and] preserve our democracy. God bless you all and may God protect our troops.

“Thank you.”

And with that, President Joe Biden followed the example of the nation’s first president, George Washington, who declined to run for a third term to demonstrate that the United States of America would not have a king, and of its second president, John Adams, who handed the power of the presidency over to his rival Thomas Jefferson and thus established the nation’s tradition of the peaceful transition of power. Like them, Biden gave up the pursuit of power for himself in order to demonstrate the importance of democracy.

After the speech, the White House served ice cream to the Bidens and hundreds of White House staffers in the Rose Garden.

And when the evening was over, First Lady Dr. Jill Biden posted an image of a handwritten note on social media. It read: “To those who never wavered, to those who refused to doubt, to those who always believed, my heart is full of gratitude. Thank you for the trust you put in Joe—now it’s time to put that trust in Kamala.”

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Steve Brodner#political cartoons#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#President Joe Biden#Biden Presidency#accomplishments of Joe Biden#Biden Harris#election 2024#team work

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bye-Bye, Boss! And The Unsung Socialist Hero Of Cincinnati’s Charter Movement

Where are the parades? Where are the celebrations? Election Day this year marks exactly a century since Cincinnati voters rose up to finally end boss rule in the Queen City.

From the 1880s right up to 1924, Cincinnati had been run by what amounted to a criminal syndicate, with George Barnsdale Cox, known as “Boss Cox,” and his minions controlling every aspect of city politics and – most importantly – city finances through their stranglehold on the Hamilton County Republican Party. The Cox Gang siphoned millions of public dollars into their own pockets, let city schools and public services languish, allowed gambling and prostitution to flourish under police protection, and nationally besmirched the reputation of our city. Just how powerful was Boss Cox? Here is a major national magazine, Collier’s, from 24 September 1910:

“No public officeholder in Cincinnati is allowed to name his own deputies. Cox himself appoints these underlings. He has in each public office his representative, who is in real charge. In one case it was disclosed in a legislative investigation that the regularly elected official was not even allowed the combination of his office safe. That was the property of Cox’s agent.”

And here is The New Republic from 7 May 1924 describing a major source of the Boss’s ill-gotten gains:

“Cox was a grafter. It was definitely proved that he had pocketed many thousands of dollars, bribes paid to him by banks for illegally depositing with them Hamilton County funds.”

By 1924, Cox himself had been dead for eight years, but the ironclad Republican machine he had constructed still sputtered along, led by burlesque impresario Rudolph K. “Rud” Hynicka. It infuriated local progressives that Hynicka didn’t even live in Cincinnati but pulled all the strings – political and purse – in Cincinnati from his office in New York City.

The entire boss system came crashing down on 4 November 1924, when Cincinnati voters marked their ballots by a 2.5 to 1 margin to adopt a city manager form of government eliminating the ward-based city council.

In the years since, mythology has enshrined a conventional explanation of how this peaceful revolution prevailed. In this telling, independent Republicans like Murray Seasongood assumed the founding father roles. Here is a typical summary of the traditional narrative, from an article by William A. Baughin from the Winter 1988 issue of Queen City Heritage:

“Under the direction of Seasongood . . . the Charter Committee conducted a successful campaign to bring about these changes in the fall elections of 1924. After this victory, the Charter Committee remained in existence, completing its transition to a de facto political party when it endorsed and campaigned for a slate of councilmanic candidates in 1925.”

Though not exactly inaccurate, the standard version ignores decades of organized opposition to Boss Cox from Democrats and, notably, Socialists. It is not too strong a statement to assert that Cincinnati’s successful charter vote in 1924 would have been impossible without concerted action by the local Socialists and their allies.

Rarely mentioned these days is a radical reformer who devoted half a century to a campaign for social and economic reform. Herbert S. Bigelow was a provocative and controversial figure throughout a long and eventful life. He opposed United States involvement in the First World War and was kidnapped and horsewhipped because of that. He lobbied for old age pensions, for fair taxation, and for municipal control of utilities and transportation.

Bigelow set the stage for the political coup of 1924 as far back as 1912, when he helped organize a progressive, statewide constitutional convention. Bigelow headed a delegation to that convention from Hamilton County, was elected president of the convention; and guided the convention toward submitting to the voters an Initiative and Referendum amendment, and a Municipal Home Rule amendment as well.

As a young man, studying for the ministry at Cincinnati’s Lane Seminary, Bigelow’s social consciousness was awakened, and he dedicated his life “less for the gospel of heaven above and more for justice here on earth.” As pastor of the old Congregational Church on Vine Street, Bigelow’s social agenda so alienated the old-time congregants that he created a totally new “People’s Church” with no theological dogma, only a commitment to progressive causes. He preached, he said, the Social Gospel.

Bigelow’s church spawned what would today be called a political action committee, known as the People’s Power League, organizing liberals and radicals of every stripe from labor unions to Socialists to disenchanted refugees from the major parties. When the United States entered World War I, Bigelow loudly protested the forced enlistment of men through the draft, a position that almost got him killed. As Daniel R. Beaver relates in his 1957 biography of Bigelow, “A Buckeye Crusader”:

“The minister's outspoken attitude aroused the opposition of many patriotic organizations around Cincinnati and finally brought about a physical attack on him October 28, 1917. Bigelow was kidnapped as he was about to address a meeting of the Socialist Party in Newport, Kentucky, taken to a deserted field and horsewhipped, ‘In the name of the women and children of Belgium.’”

Bigelow that year backed the Socialist Party in Cincinnati’s municipal elections. He was convinced his attackers were egged on by the business and industrial interests of Cincinnati. Bigelow expressed a lifelong antipathy to any cause, no matter how popular, that had the support of Cincinnati’s established capitalists. This prejudice, according to biographer Beaver, affected his involvement in the Charter movement:

“His attitude was clearly shown in 1924 when a battle was begun by moderate Cincinnatians led by Murray Seasongood to introduce the city charter form of government into the political life of Cincinnati. [Bigelow] distrusted the motives of the reformers because of their business connections and remained aloof until it became obvious that he and his followers were needed to circulate petitions for a charter election. Though subsequent events are disputed, it seems that he and his associates exacted from the Charterites a promise to include a plan for proportional representation in their bill in return for the support of Bigelow's organization.”

Despite the essential contributions from the People’s Church, Charterites downplayed the pastor’s involvement because Bigelow, in addition to building grassroot support for municipal reform was also campaigning quite vocally in 1924 for Progressive presidential candidate Robert M. LaFollette, who had the backing of the Socialists. Still, Bigelow was able to influence the Charterites to adopt several reforms that originated in his progressive campaigns.

A much more nuanced version of the victory of 1924 would acknowledge the contributions of organized labor, women and Socialists in addition to the traditional political parties, and especially the role of Cincinnati’s lifelong firebrand, Herbert S. Bigelow.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Let's go for an obscure one...what can you tell us about Benjamin Harrison?

Benjamin Harrison was the grandson of William Henry Harrison, who got into politics partly to live up to the family legacy, and party out of a sense of duty to live a life of public service. By all accounts, he wasn't a natural politician--his handshake was compared to "a dead fish wrapped in brown paper", and his enemies said that talking to him was "like talking to a hitching post". Political cartoons at the time showed him as a little guy (he was 5'6") dwarfed by his grandfather's hat, and there was a general idea that he couldn't live up to his more famous ancestor's legacy.

But he was also a decent, upstanding guy who was friendly with people he knew well, and who loved kids and dogs. Stories were told about stray dogs that liked him so much that they would try to follow him into his law office.

Harrison was a precursor to some of the things that Teddy Roosevelt later became famous for. He signed the Sherman Anti-Trust Bill that fought against big business, and he was heavily involved in conservation. He created the national forests, and he was the first president who was involved in trying to make conservation laws to save a specific species. He tried (though unsuccessfully) to regulate hunting of fur seals in international waters.

Harrison is the president in the middle of the Grover Cleveland sandwich--his term sat between Cleveland's two separate terms--because the elections at that time were won by narrow margins, thanks to a pretty even split between the two parties and a bunch of newer parties eating into the votes. Both guys were pretty chill about the whole thing. Supposedly, when Cleveland and Harrison were riding together to Harrison's inauguration, Cleveland held his umbrella to protect his victorious opponent from the rain.

When Harrison ran for a second term, his wife died two weeks before the election. After he lost, people sent him condolences about the election and his wife, but Harrison said he barely noticed the election, because that loss was nothing compared to the loss of his wife of nearly forty years.

One last thing: after the Presidential episode about Harrison focused so heavily on him being this boring, upstanding, decent guy, I was very amused to find this speech from him after James Garfield was nominated as presidential candidate at the 1880 Republican Convention.

I am not in very good voice to address the convention. Indiana has been a little noisy within the last hour, and, though the Chairman of this delegation, I forgot myself so much as to abuse my voice. I should not have detained the convention to add any word to what has been said in a spirit of such commendable harmony over this nomination, if it had not been for the over partiality of my friends from Kentucky, which whom we have had a good deal of pleasant intercourse. They insist, sirs, as I am the only defeated candidate for the Presidency on the floor of this convention, having received one vote from some misguided friend from Pennsylvania, who, unfortunately for me, didn't have staying qualities, and dropped out on the next ballot. I want to say to the Ohio delegation that they may carry to their distinguished citizen who has received the nomination at the hands of this convention my encouraging support. I bear him no malice at all. But, Mr. Chairman, I will defer my speeches until the campaign is hot, and then, on every stump in Indiana, and wherever else my voice can help on this great Republican cause to victory I hope to be found.

Let's just say I did not expect Mr. Boring and Straight-Laced to show up with a speech that could be read as, "I lost my voice because I yelled so much at the guys from Kentucky."

#answered asks#presidential talk#maybe that speech is only interesting to me#but i did want to provide something that wasn't just a summary of the podcast episode and i had something on hand#also for some reason i was really hoping to be asked about benjamin harrison#so thank you for obliging

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

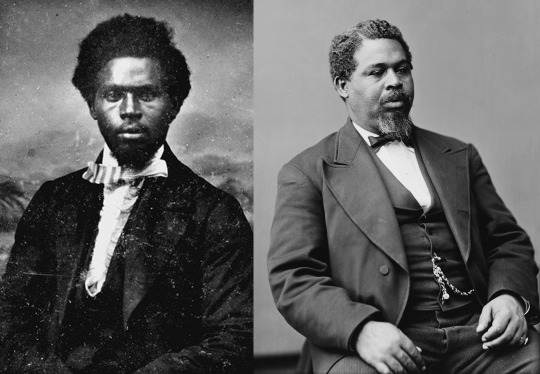

Walter “Wiley” Jones (July 14, 1848 – December 7, 1904) was a businessman in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, who was one of the wealthiest African Americans in his state. He owned the first streetcar company in Pine Bluff and a park in the city that housed the fairgrounds. A devotee of horse racing, he owned stables and a race track on the park grounds. He owned a saloon. He was active in civic affairs and was an advocate for civil rights.

He was born in Madison County, Georgia. His parents were George Jones, a white planter, and enslaved, Anne, they had six children.

In August 1886, he secured the charter for the first streetcar line in Pine Bluff. He had one and one-fourth miles completed and the first car running by October 19, 1886, coinciding with the first day of the annual fair of the Colored Industrial and Fair Association, an organization of which he was treasurer. He owned the fairgrounds located on a 55-acre park he owned near Main Street which was called Wiley Jones Park. His stables included one stallion, “Executor” that was of particular note, and later his colt, “Trickster”. He owned several mares and a herd of Durham and Holstein cattle. In 1901, his thoroughbred pace, “Billy H”, broke a track record at a race in Windsor. In 1890, he purchased the second line in Pine Bluff, known as the Citizen’s line, from H. P. Bradford for $125,000. In 1894, he sold his streetcar company to another streetcar syndicate. In 1901, he founded the Southern Mercantile Company, making his longtime friend Fred Havis president and his brother, James, manager.

He was an active Republican and was a delegate to the 1880 RNC. He opened a manual training school, the Colored Industrial Institute of Pine Bluff (1888). He was an organizer of the Arkansas Colored Men’s Association. He was a delegate to the annual convention of the Colored Men’s National Protective Association. He was a Mason and along with Professor J. C. Corbin played an important role in the building of a Masonic Temple in Pine Bluff. He sold land to the Masons to be used to build the temple. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

August 9, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

AUG 10

When President Joe Biden announced that he would not accept the Democratic nomination for president and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris on July 21—less than three weeks ago—the horizon for the 2024 presidential election suddenly shortened from years to about three months. That shift apparently flummoxed the Republicans, who briefly talked about suing to make sure that Biden, rather than Harris, was at the head of the Democratic ticket, even though the Democrats had not yet held their convention and Biden had not officially become the nominee when he stepped out of contention. Lately, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump has suggested that Biden might suddenly, somehow, change his mind and upend the whole new ticket, although Biden himself has been strong in his public support for Harris and her vice-presidential running mate, Minnesota governor Tim Walz, and Democrats held a roll-call vote nominating Harris for the presidency.

The idea that presidential campaigns should drag on for years is a relatively new one. For well over a century, political conventions were dramatic affairs where political leaders hashed out who they thought was their party’s best standard-bearer, a process that almost always involved quiet deals and strategic conversations. Sometimes the outcome was pretty clear ahead of time, but there were often surprises. Famously, for example, Ohio representative James A. Garfield went to the 1880 Republican convention expecting to marshal votes for Ohio senator John Sherman—General William Tecumseh Sherman’s brother—only to find himself walking away with the nomination himself.

As recently as 1952, the outcome of the Republican National Convention was not clear beforehand. Most observers thought the nomination would go to Ohio senator Robert Taft, the son of President William Howard Taft, but after a tremendous battle—including at least one fist fight—the nomination went to war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower, who challenged Taft because of the senator's opposition to the new North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Taft supporters took that loss hard: Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. drove Eisenhower’s victory, prompting right-wing Republicans’ enduring hatred of what they called the “eastern establishment.”

The 1960 presidential election ushered in a new era in politics. While Eisenhower had turned to advertising executives to help him appeal to voters, it was 1960 Democratic nominee Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy who was the first presidential candidate to turn to a public opinion pollster, Louis Harris, to help him adjust his message and his policies to polls.

Political campaigns were modernizing from the inside to win elections, but as important in the long run was Theodore H. White’s best selling account of the campaign, The Making of the President 1960. White was a successful reporter, novelist, and nonfiction writer who, finding himself flush from a movie deal and out of work when Collier’s magazine went under, decided to follow the inside story of the 1960 presidential campaign. “I want to get at the real guts of the process of making an American president—what the mechanics, the mystique, the style, the pressures are with which an American who hopes to be our President must contend,” White wrote to Senator Estes Kefauver (D-TN).

White set out to follow the campaigns of the many primary candidates that year: Democrats Hubert Humphrey, Lyndon Johnson, and John F. Kennedy and Republicans Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller.

Before White’s book, political journalism picked up when politicians announced their candidacy, and focused on candidates’ public statements and position papers. White’s portrait welcomed ordinary people backstage to hear politicians reading crowds, fretting over their prospects, and adjusting their campaigns according to expert advice. In heroic, novelistic style, White told the tale of the struggle that lifted Kennedy to victory as the other candidates fell away, and his book spent 20 weeks at the top of the bestseller lists and won the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction.

White’s book emphasized the long process of building a successful presidential race and the many advisors who made such building possible. In the modern world a presidential campaign lasted far longer than the few months after a convention. In his intimate portrait of that process, White radically transformed political journalism. As historian John E. Miller noted, journalists who had previously covered the public face of a candidacy “now sought to capture in minute detail the behind-the-scenes maneuvering of the candidates and their strategy boards and to probe beneath the surface events of political campaigns to ascertain where the ‘real action’ lay.”

For journalists, seeing the inside story of politics as a sort of business meant leaving behind the idea that political ideology mattered in presidential elections, a position that political scientists were also abandoning in 1960. It also meant getting that inside story by preserving the candidates’ goodwill, something we now call access journalism. Other journalists leapt to follow the trail White blazed, and by 1973 the pack of presidential journalists had become a story in its own right. White told journalist Timothy Crouse that he had come to regret that his new approach to presidential contests had turned presidential campaigns into a circus.

Over time, presidential campaigns began to use that circus as part of their own story, spinning polls, rallies, and press coverage to convince voters that their candidate was winning. But now the 2024 election seems to be challenging the habit of seeing a presidential campaign as a long, heroic sifting of advice and application of tactics, as well as the perceived need for access to campaign principals.

Yesterday, apparently chafing as the Harris-Walz campaign turns out huge crowds, Trump called reporters to his company’s Florida property, Mar-a-Lago. Those determined not to miss any twist of the campaign—and who had enough advance notice to make it to Florida—listened to him serve up his usual banquet of lies: that doctors and mothers are murdering babies after they’re born; everyone wanted Roe v. Wade overturned, no one died on January 6, 2021; he loves autocrats and they love him; and so on. The journalists there did not ask him about the recent bombshell report suggesting that Egypt poured $10 million into his 2016 campaign.

But, as conservative writer Tom Nichols of The Atlantic noted, Trump appears nonetheless to have gone entirely off the rails. He claimed that the crowd he drew on January 6 was bigger than those who gathered in 1963 to hear the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his famous I Have a Dream speech, and he told the entirely fabricated story of surviving an emergency landing in a helicopter with former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown. As Nichols put it, “The Republican nominee, the man who could return to office and regain the sole authority to use American nuclear weapons, is a serial liar and can’t tell the difference between reality and fantasy. Donald Trump is not well. He is not stable. There’s something deeply wrong with him.”

But the media appears to be sliding away from Trump: today he angrily insisted he could prove that the dangerous helicopter trip actually occurred, leading New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman to note that “Mr. Trump has a history of claiming he will provide evidence to back up his claims but ultimately not doing so.” When asked to produce the flight records he claimed to have, Trump “responded mockingly, repeating the request in a sing-song voice.”

In contrast, as presidential candidates, first Biden and now Harris have not appeared to bother with access journalism or courting established media. Instead, they have recalled an earlier time by turning directly to voters through social media and by articulating clear policies that support their dedication to the larger project of American democracy.

Yesterday, after journalists had begun to complain that they did not have enough access to Harris, she came to them directly on the tarmac at the Detroit airport and asked, “What’cha got?” All but one of their questions were about Trump and his comments; the one question that was not about Trump came when a journalist asked when Harris would sit down for an interview.

—

1 note

·

View note

Text

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

August 9, 2024

Heather Cox Richardson

Aug 10, 2024

When President Joe Biden announced that he would not accept the Democratic nomination for president and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris on July 21—less than three weeks ago—the horizon for the 2024 presidential election suddenly shortened from years to about three months. That shift apparently flummoxed the Republicans, who briefly talked about suing to make sure that Biden, rather than Harris, was at the head of the Democratic ticket, even though the Democrats had not yet held their convention and Biden had not officially become the nominee when he stepped out of contention. Lately, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump has suggested that Biden might suddenly, somehow, change his mind and upend the whole new ticket, although Biden himself has been strong in his public support for Harris and her vice-presidential running mate, Minnesota governor Tim Walz, and Democrats held a roll-call vote nominating Harris for the presidency.

The idea that presidential campaigns should drag on for years is a relatively new one. For well over a century, political conventions were dramatic affairs where political leaders hashed out who they thought was their party’s best standard-bearer, a process that almost always involved quiet deals and strategic conversations. Sometimes the outcome was pretty clear ahead of time, but there were often surprises. Famously, for example, Ohio representative James A. Garfield went to the 1880 Republican convention expecting to marshal votes for Ohio senator John Sherman—General William Tecumseh Sherman’s brother—only to find himself walking away with the nomination himself.

As recently as 1952, the outcome of the Republican National Convention was not clear beforehand. Most observers thought the nomination would go to Ohio senator Robert Taft, the son of President William Howard Taft, but after a tremendous battle—including at least one fist fight—the nomination went to war hero Dwight D. Eisenhower, who challenged Taft because of the senator's opposition to the new North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Taft supporters took that loss hard: Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. drove Eisenhower’s victory, prompting right-wing Republicans’ enduring hatred of what they called the “eastern establishment.”

The 1960 presidential election ushered in a new era in politics. While Eisenhower had turned to advertising executives to help him appeal to voters, it was 1960 Democratic nominee Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy who was the first presidential candidate to turn to a public opinion pollster, Louis Harris, to help him adjust his message and his policies to polls.

Political campaigns were modernizing from the inside to win elections, but as important in the long run was Theodore H. White’s best selling account of the campaign, The Making of the President 1960. White was a successful reporter, novelist, and nonfiction writer who, finding himself flush from a movie deal and out of work when Collier’s magazine went under, decided to follow the inside story of the 1960 presidential campaign. “I want to get at the real guts of the process of making an American president—what the mechanics, the mystique, the style, the pressures are with which an American who hopes to be our President must contend,” White wrote to Senator Estes Kefauver (D-TN).

White set out to follow the campaigns of the many primary candidates that year: Democrats Hubert Humphrey, Lyndon Johnson, and John F. Kennedy and Republicans Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller.

Before White’s book, political journalism picked up when politicians announced their candidacy, and focused on candidates’ public statements and position papers. White’s portrait welcomed ordinary people backstage to hear politicians reading crowds, fretting over their prospects, and adjusting their campaigns according to expert advice. In heroic, novelistic style, White told the tale of the struggle that lifted Kennedy to victory as the other candidates fell away, and his book spent 20 weeks at the top of the bestseller lists and won the 1962 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction.

White’s book emphasized the long process of building a successful presidential race and the many advisors who made such building possible. In the modern world a presidential campaign lasted far longer than the few months after a convention. In his intimate portrait of that process, White radically transformed political journalism. As historian John E. Miller noted, journalists who had previously covered the public face of a candidacy “now sought to capture in minute detail the behind-the-scenes maneuvering of the candidates and their strategy boards and to probe beneath the surface events of political campaigns to ascertain where the ‘real action’ lay.”

For journalists, seeing the inside story of politics as a sort of business meant leaving behind the idea that political ideology mattered in presidential elections, a position that political scientists were also abandoning in 1960. It also meant getting that inside story by preserving the candidates’ goodwill, something we now call access journalism. Other journalists leapt to follow the trail White blazed, and by 1973 the pack of presidential journalists had become a story in its own right. White told journalist Timothy Crouse that he had come to regret that his new approach to presidential contests had turned presidential campaigns into a circus.

Over time, presidential campaigns began to use that circus as part of their own story, spinning polls, rallies, and press coverage to convince voters that their candidate was winning. But now the 2024 election seems to be challenging the habit of seeing a presidential campaign as a long, heroic sifting of advice and application of tactics, as well as the perceived need for access to campaign principals.

Yesterday, apparently chafing as the Harris-Walz campaign turns out huge crowds, Trump called reporters to his company’s Florida property, Mar-a-Lago. Those determined not to miss any twist of the campaign—and who had enough advance notice to make it to Florida—listened to him serve up his usual banquet of lies: that doctors and mothers are murdering babies after they’re born; everyone wanted Roe v. Wade overturned, no one died on January 6, 2021; he loves autocrats and they love him; and so on. The journalists there did not ask him about the recent bombshell report suggesting that Egypt poured $10 million into his 2016 campaign.

But, as conservative writer Tom Nichols of The Atlantic noted, Trump appears nonetheless to have gone entirely off the rails. He claimed that the crowd he drew on January 6 was bigger than those who gathered in 1963 to hear the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his famous I Have a Dream speech, and he told the fabricated story of surviving an emergency landing in a helicopter with former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, a story that appears to have involved a different Black man, at a different time, and did not feature the conversation he recounted.*

As Nichols put it, “The Republican nominee, the man who could return to office and regain the sole authority to use American nuclear weapons, is a serial liar and can’t tell the difference between reality and fantasy. Donald Trump is not well. He is not stable. There’s something deeply wrong with him.”

But the media appears to be sliding away from Trump: today he angrily insisted he could prove that the dangerous helicopter trip actually occurred, leading New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman to note that “Mr. Trump has a history of claiming he will provide evidence to back up his claims but ultimately not doing so.” When asked to produce the flight records he claimed to have, Trump “responded mockingly, repeating the request in a sing-song voice.”

In contrast, as presidential candidates, first Biden and now Harris have not appeared to bother with access journalism or courting established media. Instead, they have recalled an earlier time by turning directly to voters through social media and by articulating clear policies that support their dedication to the larger project of American democracy.

Yesterday, after journalists had begun to complain that they did not have enough access to Harris, she came to them directly on the tarmac at the Detroit airport and asked, “What’cha got?” All but one of their questions were about Trump and his comments; the one question that was not about Trump came when a journalist asked when Harris would sit down for an interview.

*I corrected this sentence, which said the helicopter story was “entirely fabricated,” shortly after midnight on August 10, in light of a new story by Christopher Cadelago in Politico that says Nate Holden, a former city councilman and state senator from Los Angeles, says he was on a frightening helicopter ride with Trump at some point in the 1990s.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

WE'RE NOT GOING BACK

#Letters from An American#Heather cox Richardson#Nate Holden#Willie Brown#Trump lies#Presidential campaigns#history#American History#Journalism

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

First Afro-American ran for US President

“George Edwin Taylor ran for president a long time before Barack Obama.”

“Born in the pre-Civil War South to a mother who was free and a father who was enslaved, George Edwin Taylor would become the first African American selected by a political party to be its candidate for the presidency of the United States.

Taylor was born on August 4, 1857 in Little Rock, Arkansas to Amanda Hines and Bryant (Nathan) Taylor. At the age of two, George Taylor moved with his mother from Arkansas to Illinois. When Amanda died a few years later, George fended for himself until arriving in Wisconsin by paddleboat in 1865. Raised in and near La Crosse by a politically active African family, he attended Wayland University in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin from 1877 to 1879, after which he returned to La Crosse where he went to work for the La Crosse Free Press and then the La Crosse Evening Star. During the years 1880 to 1885 he produced newspaper columns for local papers as well as articles for the Chicago Inter Ocean.

Taylor's newspaper work brought him into politics--especially labor politics. He sided with one of the competing labor factions in La Crosse and helped re-elect the pro-labor mayor, Frank "White Beaver" Powell, in 1886. In the months that followed, Taylor became a leader and office holder in Wisconsin's statewide Union Labor Party, and his own newspaper, the Wisconsin Labor Advocate, became one of the newspapers of the party.

In 1887 Taylor was a member of the Wisconsin delegation to the first national convention of the Union Labor Party, which met in Ohio in April, and refocused his newspaper on national political issues. As his prominence increased, his race became an issue, and Taylor responded to the criticism by increasingly writing about African American issues. Sometime in 1887 or 1888 his paper ceased publication.

In 1891 Taylor moved to Oskaloosa, Iowa where he continued his interest in politics, first in the Republican Party and then with the Democrats. While in Iowa Taylor owned and edited the Negro Solicitor, and became president of the National Colored Men's Protective Association (an early civil rights organization) and the National Negro Democratic League, an organization of Africans within the Democratic Party. From 1900 to 1904 he aligned himself with the Populist faction that attempted to reform the Democratic Party.

Taylor and other independent-minded African Americans in 1904 joined the first national political party created exclusively for and by Africans, the National Liberty Party (NLP). The Party met at its national convention in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904 with delegates from thirty-six states. When the Party's candidate for president ended up in an Illinois jail, the NLP Executive Committee approached Taylor, asking him to be the party's candidate.

While Taylor's campaign attracted little attention, the Party's platform had a national agenda: universal suffrage regardless of race; Federal protection of the rights of all citizens; Federal anti-lynching laws; additional African regiments in the U.S. Army; Federal pensions for all former slaves; government ownership and control of all public carriers to ensure equal accommodations for all citizens; and home rule for the District of Columbia.

Taylor's presidential race was quixotic. In an interview published in The Sun (New York, November 20, 1904), he observed that while he knew whites thought his candidacy was a "joke," he believed that an independent political party that could mobilize the African American vote was the only practical way that blacks could exercise political influence. On election day, Taylor received a scattering of votes.

The 1904 campaign was Taylor's last foray into politics. He remained in Iowa until 1910 when he moved to Jacksonville. There he edited a succession of newspapers and was director of the African American branch of the local YMCA. He was married three times but had no children. George Edwin Taylor died in Jacksonville on December 23, 1925.”

Above written source=

George Edwin Taylor - 2014 - Question of the Month - Jim Crow Museum

The Brother tried and I knew all the Afro-Americans couldn't vote for him because voter suppression .

#george edwin taylor#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#afrakans#africans#brown skin#african culture#barack obama#african president#politics

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

time to learn about Actual American Hero Robert Smalls!!!! split into two sections: before and during the civil war, and after the civil war

before and during the civil war:

born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina in 1839 (his owner was most likely his father). he grew up as part of the Lowcountry Gullah community.

his mother had grown up in the fields but worked in the main house when he was born. Robert was a favorite of their owner but she wanted to make sure he understood what it was like for field slaves so she requested that he work in the fields and witness a whipping

he was sent to Charleston to work when he was 12 and earned $1 a week, with the rest of his money going to his owner. he started as a laborer and eventually started working on boats, working his way up to become what was essentially a pilot (even though he was a slave and couldn’t be given the proper job title). due to his work on ships, he knew Charleston Harbor really well

the civil war started in spring of 1861 (the Battle of Fort Sumter, which started the war and took place at the mouth of Charleston Harbor, was in April 1861) and in the fall he was assigned to steer the CSS Planter (CSS stands for Confederate States Ship). the ship’s jobs included surveying waterways and laying mines. he earned the trust of the crew and owners by pretending to be happy working on the ship while secretly planning an escape with the other slaves on board

on May 12, the Planter picked up four big guns from a Confederate post that was being dismantled south of Charleston, then returned to CHS and loaded 200 pounds of artillery and a bunch of firewood. that night the three white officers left the ship to sleep on shore and left the enslaved crew aboard as usual.

early in the morning on May 13, Robert Smalls put on the captain’s uniform and a straw hat similar to the one the captain usually wore and left the wharf. they stopped at another wharf to pick up his family as well as family members of some of the other enslaved crew, all of whom had hidden out on another ship earlier on May 12. Robert Smalls and his straw hat copied the captain’s mannerisms and sailed past FIVE confederate forts using the correct hand signals; the alarm was raised at Fort Sumter only after they had passed out of the fort’s gun range. Robert Smalls drove that confederate ship directly to the Union blockade at the mouth of Charleston Harbor and raised the white sheet his wife Hannah had brought to surrender the ship to the union

not only did the ship have four guns and 200 lbs of artillery - Robert Smalls also had the captain’s code book of confederate signals and a map of all of the mines in charleston harbor, as well as a ton of knowledge about the waterways around charleston and the confederate military instillations and movements. he was viewed as extremely intelligent and hailed as a hero in the north (obviously)

he was given what we all can agree was a criminally small amount of “prize money” for the transfer of the Planter to the union - his share was $1500 (he was one of eight slaves aboard) based on the appraisal. in the 1880s, the appraisal was disputed and it was said the value of the ship should have been close to $60,000. even still he didn’t get any more money until 1900, when he was given an additional $3500 (bringing the total to $5000, which a lot of people still felt was too little and they were definitely right)

RS served as a civilian in the union navy and army and was instrumental in convincing Lincoln and Edwin Stanton to allow black men to enlist in the union army at Port Royal, SC (google the Port Royal Experiment for more information!! I could do another entire post about Mitchelville tbh). he was supposedly given a commission in the navy so he could be properly paid as a pilot. when he tried to collect his pension after the war, he was told he hadn’t received an official commission. it took TWO acts of congress (1883, which failed probably because he was black, and 1897) for him to be put on the Navy retired list and allow him to collect a pension of $30 per month, that of a Navy captain

you thought that shit was amazing? after the war:

he moved back to Beaufort and bought a house. which house you ask??? that’s right, he bought his FORMER OWNER’S house (511 Prince Street) which had been seized in 1863 because the dude refused to pay taxes (and then won the court case when his former owner tried to sue him to get it back, which became a very important precedent case). his mom lived with him for the rest of her life, and he even let his former owner’s wife live in the house at the end of her life

he taught himself to read and write in less than a year(!!) and bought another building to serve as a school for african-american children

he had several successful businesses: a store specifically to serve the needs of freedmen, a horse-drawn railway line that went from the wharves in charleston to the depots 18 miles inland, and he owned and published the Beaufort Southern Standard newspaper

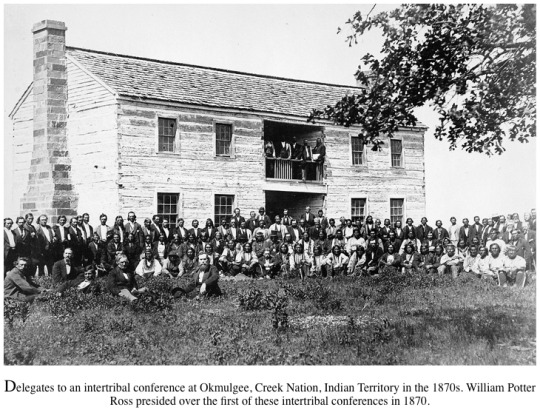

his fame during the war and the fact that he was fluent in the Gullah dialect spoken in the Lowcountry helped him in his very, very successful political career - he was a delegate at the SC constitutional conventions in 1868 and 1895 as well as at several Republican National Conventions (back when the republicans were the good guys); he was elected to the SC House of Representatives in 1868 and then selected to complete the unexpired time in Jonathan Jasper Wright’s SC Senate seat; and he was elected to the US House of Representatives five times (until the mid-1900s, he was the second-longest serving african-american member of congress)

while in the HoR, he introduced an amendment to a bill that would desegregate the army, which wasn’t considered by congress. he was a supporter of racial integration legislation while serving in the senate.

the 1895 SC constitutional convention he and five other african-american delegates tried to stop the disenfranchisement of black voters, and worked to publicize the issue, but weren’t successful in stopping the ratification of the new constitution

he died in 1915 (aged 75!) and was buried at the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Beaufort - a monument to him was installed in the churchyard in 1976 and is inscribed with the following quote of his: “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

#robert smalls#black history#I told you I would do it and I did!!!!!!#it's a long one but VERY INTERESTING PLEASE READ

117 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is Trump the first person to run for president three different times?

No, there have been numerous people through the history of the United States who have run for President three or more times, but most of them didn't get their party's nomination.

Interestingly, a lot of people forget that the 2024 election is actually Joe Biden's fourth, full-fledged, formal Presidential campaign, in addition to Trump's third campaign. Biden unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination in 1988 and 2008 before finally winning the nomination and general election in 2020. Ronald Reagan first ran for President in 1968 when he jumped into the race for the Republican nomination as an alternative to Richard Nixon, but it was kind of a half-hearted, late bid and Reagan later admitted that he wasn't quite ready to run for President at that point, which was only about a year into his tenure as Governor of California. Reagan challenged incumbent President Ford for the Republican nomination in 1976 and very nearly pulled off a rare intraparty defeat of a sitting President from his own party. And of course, Reagan ran and won in 1980 and 1984.

It's not just a relatively recent phenomenon, either; candidates have been running for President three or more times for as long as the Presidency has existed. Thomas Jefferson sought the Presidency in 1796 , 1800, and 1804, and there are many more examples, including Ulysses S. Grant, who was the first former President to make a serious attempt at breaking George Washington's tradition of serving two terms and then retiring. Grant won Presidential elections in 1868 and 1872, and allowed his supporters to actively work for his nomination at the 1880 Republican National Convention after President Hayes retired without seeking a second term. Grant was the frontrunner for the nomination, but once the balloting for the nominee started, the convention became deadlocked between Grant and James G. Blaine -- another person who ran for President multiple times: 1876, 1880, and 1884 (when he was nominated, but lost the general election). On the thirty-sixth ballot, the Republicans finally nominated James Garfield, who had emerged as a compromise candidate.

It is less common for someone to be a major party nominee for President on three or more occasions, which Trump has a shot of being in 2024 if he's not in prison. However, it is still not unprecedented. Obviously, Franklin D. Roosevelt won four Presidential elections (1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944), which had never happened before and will never happen again unless the Constitution is amended. William Jennings Bryan was the Democratic nominee in 1896, 1900, and 1908, and lost all three times. Grover Cleveland won the Democratic nomination in three straight elections: 1884 (which he won), 1888 (which he lost), and 1892 (which he won). Trump is hoping to join Cleveland as the only Presidents to serve two non-consecutive terms. Henry Clay was his party's nominee on three different occasions, and lost all three times. In an odd quirk of the times, because the major political parties were still in the process of forming in the first half of the 19th Century, Clay was technically the Presidential nominee for three different political parties: Democratic-Republican in 1824, National Republican in 1832, and Whig in 1844. Martin Van Buren was elected President as the Democratic nominee in 1836 and renominated in 1840, but lost the general election, After breaking with his party over the spread of slavery to new American territories, former President Van Buren ran as the Free Soil nominee in 1848, but came in third in the general election behind Zachary Taylor and Lewis Cass. And, one more recent example would be Richard Nixon, who was the 1960 Republican Presidential nominee and narrowly lost the general election in John F. Kennedy. Despite the belief that his political career was finished -- particularly after a humiliating loss in the 1962 campaign for Governor of California -- Nixon won the Republican nomination again in 1968 and 1972 and went on to win the general election both times (as well as winning 49 out of 50 states in 1972).

(I'm sorry...I understand that was a long-winded, overly-detailed way of answering your question when I also could have just said, "No.")

#Presidents#Presidential Elections#Presidential Politics#Presidential Nominees#Presidential Campaigns#History#Politics#Political History#Presidential History#Campaigns#Elections

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, more girls than boys went to secondary school in an increasing ratio in all parts of the country. Girls represented 53 percent of all students in 1872 and 57 percent in 1900. They were especially overrepresented in public schools. Although private schools had equal percentages of male and female attendees, by 1900 about 60 percent of the students in public high schools were girls.

In the West girls attended high schools at an especially high rate in relation to the attendance of boys, whose labor was generally too valuable for families to forgo. Most students in secondary schools lived in the Northeast, however. The educational historian Joel Perlmann’s rich statistics from Providence, Rhode Island, allow us to consider the role of class and parentage in determining girls’ high school attendance.

In 1880 about 14 percent of all teenage girls were enrolled in high schools in Providence, compared with perhaps 2–3 percent nationally. Although high schools were supported by public funds, those who sent their children needed to be able to do without their labor. Native whites in Providence sent a third of their teenage daughters to high school and nearly a quarter of their sons. White-collar workers (whether immigrant or native) also sent a third of their teenage daughters and just over a quarter of their teenage sons to high school. (The elite were more likely to send their children to private schools.)

Where class and native-born parentage overlapped, as it often did, secondary school attendance was especially high. Yankee, white-collar parents sent the highest proportion of both daughters (46 percent) and sons (36 percent) to secondary school. Though a significant majority of teenage American girls could not afford to go to school, those who did represented a growing and influential segment of the youth population.

These carefully compiled statistics raise some important questions. Why did girls go to secondary school in higher numbers than boys? How might one explain a family’s decisions to allow a girl to remain in school while sending her brother out to work? Conventional wisdom cites the lower ‘‘opportunity costs’’ of educating girls. Girls’ work was sufficiently devalued in the urban labor market that families would consider forgoing the potential income for other desired ends.

One such end, as we have seen, was the goal of refinement, that eighteenth-and nineteenth-century project designed to demonstrate the genteel sensibilities of aristocracy as a means of securing middle-class respectability. The historian Richard Bushman has pointed out the numerous contradictions of this aristocratic aesthetic which coexisted both with a capitalist culture based on labor and a republican tradition that dignified it. He has also argued, however, that the strongest constraints on conduct in the name of gentility were levied on young women, who from the eighteenth century forward were expected to demonstrate reserve and grace to establish their family’s standing.

In the late eighteenth century, this quest for refinement fostered a gendered, ornamental female education. Eliza Southgate, attending school in Boston, responded to her brother’s compliments on her letter writing with thanks and her ‘‘hope I shall make a great progress in my other studies and be an ‘Accomplished Miss.’’’ What that might mean was fleshed out a bit by Rachel Mordecai’s report for her mother of her younger sister’s progress.

She noted that her young charge read well, knew several pages of French nouns, added and multiplied, knew first principles in geography, knew parts of speech and conjugated verbs in grammar, played a number of songs. Mordecai concluded: ‘‘She sews plain work tolerably well, and has marked the large and small alphabet on a sampler.’’ The seamless blending of parts of speech and piano, sums and sampler, characterized an era in female education in which accomplishments were equally academic and ornamental. An educated and accomplished miss was expected to call a certain attention to herself.

The common-school movement of the early nineteenth century educated boys and girls together, and with the republican and Jacksonian revolution in culture, commentators grew less comfortable with the ornament of aristocratic accomplishment. Instead they praised the restraint, reserve, and womanliness of well-educated girls. Refinement in lessons as in life might be measured less by conspicuous self-display and more by selflessness, by learning what not to do, and how not to be. Youth’s Companion expressed these lessons in an 1868 story of an exemplary schoolgirl:

‘‘She was quiet, almost to reserve, though her dimpling smiles were prettier than any language; but when she did speak, her words were well chosen, though few.’’ She had applied the same lesson to her music. Though she played the piano well, ‘‘Jenny made rare use of her accomplishment. She never bored anybody, as the best players do at times.’’ All in all, Jenny had grasped the true restraint which represented a gendered lesson well learned. Whatever it actually delivered (and I shall argue that it largely delivered something else), school seemed to be the best strategy for ensuring that at least one member of the family—the one whose wages could most easily be forgone—might embody the class aspirations of the rest.

To demonstrate class standing, increasingly, young women did not work for wages. The irony was that attending school equipped young women for work—especially for one of the few semirespectable jobs available to them. Accompanying the message that education was refining and improving was a parallel rationale that was often hidden: in the unstable economy of the nineteenth century, education provided an entrée to the job of schoolteaching, a tolerable means of wage-earning for young women in need.

With the expansion of school systems in the nineteenth century and the growth in the national economy opening more lucrative opportunities for men, low-paid women increasingly replaced men as the nation’s teachers. By 1870 about two-thirds of the nation’s teachers were women, a proportion that increased to nearly three-quarters in 1900. In the major cities of the Northeast, more than four-fifths of the teaching profession was female.