#1860s extant garment

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hello hello! I have gotten myself into an American Civil War era ball in November and I was wondering if you had any input on formal dress from the era! I've never done reenactment before but I would love some input on what I should wear!

That sounds very cool! I hope you'll have great time there when it eventually comes! :D

I'll go through all the garments and accessories that would have been used at the time, but obviously limitations of reality might get in the way of some parts. I'll give my opinion on what I think is more and less necessary to embody the era, but I've never done reenactment either so I can't really say for sure what is the expected level of historical accuracy, maybe someone with some experience of reenactment can chime in. But you'll be the best judge on what you can realistically get/make. Think of this as background info.

So the years we are looking at are 1861-65. I'll start from underlayers towards outer layers.

Shift and drawers

By 1860s drawers were used by most women with their shifts. The shift had wide neckline, small sleeves and often a bit of lace trimming. The sleeves could be wide like in the examples, but less often they might be small poofs. It was roughly knee length and still quite often made from white linen, but white cotton too.

Linen shift from mid 1800s US, and a linen shift from 1861-65.

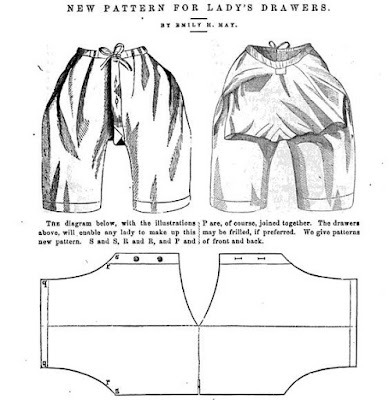

The drawers were very simple in design. They most often split crotch seam, meaning the crotch seam wasn't sewn closed and the waistband was the only thing holding the pieces together. This made it easier to use the bathroom. They reached around mid-calf, sometimes just over the knees, but ankle length was too long. 1860s drawers were very full and usually had simple lace and/or frills at the hem. They were also made from either linen or cotton at the time.

The first example is from 1863 Peterson's Magazine, where pattern for joined drawers are marketed as new, but it's still very much patterned in a way where the drawers don't need to be taken down when using bathroom. It would be still pretty rare. Then drawers from 1860s US.

I would say basically any shift with short sleeves and wide enough neckline works here or really in place of that even almost any similarly shaped under dress, but it's very crucial to have something under the corset. If a shift isn't easily available, the replacing dress should be thin so it's not super hot, loose so it doesn't need closures that might cause chafes under the corset and preferably linen or at least cotton, so it's not sweaty and feels comfortable. Linen is really the superior undergarment material as it's anti-bacterial, very breathable and easy to wash, cotton was only contending with it for very Victorian reasons. The drawers are not necessary, not everyone used them at the time. If you don't feel comfortable not wearing any underpants (which was the other option at the time), I do recommend them since using a bathroom with the crinoline and underpants you have to take down is pretty hard.

Corset

1860s corset was fairly short compared to earlier and later corsets, and usually wouldn't reach very far on the hips. It wasn't necessary as the waistline was just above the natural waistline and the skirt was very wide so the shape of the hips would be completely covered. The corset used in formal settings like balls was usually heavily boned but for the same reasons as why the corset itself was relatively short, the bones didn't necessarily reach beyond the waistline. For these reasons even the heavily boned corsets left very large range of movement for the torso. As it was typical for the whole Victorian era, the corset was closed at the front with a busk and had lacing in the back.

The boning was usually just whalebone, metal often only used in the busk. The fabric was reinforced with most often with cotton twill or canvas. Especially in case of these fancier corsets used with evening gowns, the corset often had a silk fashion fabric, which could be white like other undergarments or colorful.

Silk corset from 1864 Britain/France, and cotton wedding corset from 1865-67 US.

Corset really is very necessary to pull of the ball gown of this era. Not just because it's very crucial in getting the silhouette, but also because it makes it easier to wear the large skirt as the corset distributes it's weight across the torso and supports the torso too. I do think any Victorian corset works here well enough as they are roughly similarly shaped. Because the crinoline is very light, the skirt is lighter than it looks, so even other less structured supportive garments that give even somewhat similar shape could work if Victorian corsets are not an option, like Regency stays or Edwardian corsets or even some modern corset. From what I've heard about reenactment events, I would prioritize having corset (or similar) that fits you and you know you can wear for a long period of time over historical accuracy and the right silhouette. (Corset often needs to be broken in like leather shoes, because the whalebones will shape into the body.)

Crinoline

Crinoline is a crucial part of the underlayers to achieve the silhouette of this era. The silhouette went through some changes even in the first half of 1860s. It started as quite similar to late 1850s silhouette of very large and round, though already in 1861, the volume was more focused in the back. In the following years the skirt would become less round, but wider and the volume would increasingly lean to the back. The skirt would reach it's widest point with massively long back, almost like a very wide bustle, in 1865.

Crinoline from 1860-62 Spain, and another from 1865. You can see the progression quite well between these two.

Here's also all of these foundational layers shown all at once, though I think the crinoline is from between 1866-68, since it's so narrow around the hips (the silhouette collapsed very quickly from the critical mass of 1865 to a much more narrow A-lined silhouette).

As said, this is really necessary to pull of the skirt of early half of 1860s. You really can't get the shape right without it. Especially for the earlier silhouette of the decade 1850s crinoline works perfectly fine and even the later 1860s crinoline like above. Even modern or 1950s hoop skirts can be serviceable here, but if the skirt is cut like in the mid 1860s, it definitely does need the elliptical crinoline that are very specific for those couple of years, as you'll see in the examples of the next section.

Petticoat

Petticoat's purpose in this era was mainly to smooth out the crinoline. It was therefore voluminous and usually made out of fairly stiff fabric, usually a bit heavier linen or cotton. There was often horizontal pleats around the hem, which would reinforce the shape. Couple of layers could be used too to properly cover the crinoline. It was pretty plain, usually white, but not necessarily, maybe with a bit of lace at the hem. Especially in early 1860s the petticoat was usually gathered with cartrigde pleats, which give a very round and voluminous shape. Around the mid 1860s, the pleating would be mostly focused in back to enhance the long shape.

Cotton petticoat from 1855-65 US, and linen petticoat from 1860-65 US. The first is very likely late 1855 or very early 1860s as it's so very round. The second is definitely closer to 1865, it shows very well how much more volume was at the back, as the hem there is much longer.

This is not strictly necessary, but it's very obvious when a crinoline doesn't have a petticoat on top of it, especially if the skirt is made out of some thinner fabric. It can be very simple, it just needs to be big enough. Basically any similar sized skirt or petticoat works fine in it's place.

Corset cover

Corset cover or camisole, as the name suggests, had similar purpose as petticoat, to smooth out the hard line of the corset. It was a small shirt, with similar neckline and sleeves as shift at the time. It was like other undergarments almost always white, often made out of cotton, but linen too.

Cotton corset cover from 1860 US, and another from 1864-68 US.

It's not super necessary imo, but it does give a smoother finish. It could be pretty easily replaced by a corset cover from different era, that's close enough in design (so it won't be showing under the bodice), if something like that is more easily available.. Any shirt really that's similarly loose-ish, so that it doesn't create too much bulk, but also doesn't get pinned tense by the bodice, would work I think.

Ball gown

Now we finally get to the meat of it. Ball gowns of the early half of 1860s had very tiny sleeves, that hung just over the shoulder. They were usually tiny poofs or could be tiny frills too. As mentioned earlier, the bodice was short and ended abruptly at the waistline, which was slightly above the natural waist, to emphasize the mass of the skirt. A typical waistline exaggerated pointed end.

The skirt was not as elaborately layered like a cake as in late 1850s, but typically it had a bit of layering at the hem, where the layers were displayed by different types of gathering. An organza layer on top was very popular. A bit of trimming at the hems of the layers of the skirt was common, but the amount of trimmings was pretty restrained (especially when compared to the next couple of decades).

The colors of evening wear were usually light. I've noticed white, light pink, light blue, mint and lavender crop up most often. It was though very trendy to have a dark or a bright jewel accent color combined with the soft dominant color. The new synthetic dyes were able to create cheep bright colors unlike before and people were very into them. The most popular colors, that were also used a lot as accent colors in evening wear were bright purple, magenta, electric blue and emerald green. The evening gowns tended to be solid color and mostly one color too, except for the accents. Typical decorative motifs were fabric flowers, bows, lace trimming and fringes. For evening wear the fabric was most often silk as taffeta or satin and possibly organza in addition.

Here's some select fashion plates with ball gowns I really like. The firs is from 1863 and the other two are from 1865.

The first two include my personal favorite trend from this period, which is corselette/Swiss waist/Medici waist. It was a small decorative usually underbust waistwear, sometimes with shoulder straps, sometimes without. It was part of the Gothic Revival fashion and was alluding to Renaissance bodices and stays. They really have nothing to do with Medieval or Renaissance fashion, but Victorians associated the use of waistwear and stays as outer wear with vague idea of The Gothic for quite complicated reasons (I talk about that in this post at length). They were lightly boned, but just to keep up the shape, they were not in any way supportive, just decorative. The blue dress in the first example above has a Medici waist (the trend was loosely inspired by Catherine de Medici's portraits), which has the distinctive upward pointed neckline combined with shoulder straps, and the white dress in the second example has either Swiss waist or corselette. The terms were used quite interchangeably, even the Medici waist's definition is pretty loose (I usually just default to corselette). Below there's couple of more example of these. First is silk corselette from 1863-67 US and second is silk corselette from 1864-68 US. The third is a dress with another silk coselette supposedly from 1855 US. I think the bodice is too short for 1855 and the skirt very distinctly mid 1860s, with the volume in the back, so I won't believe MET on this. Interestingly the dress is made out of piña fabric, which is traditional fabric made out of pineapple plant fiber and was a luxury fabric among Western upper crust in 18th and 19th centuries for colonialist reasons.

Okay, I'm done with the corselette propaganda. I have a pinterest board of primary images with a section for 1860-65 for additional inspiration, but I haven't organized it yet, so there might be some misplaced images.

Accessories

These are not that necessary, but a bit of extra detail to sell the look.

Hair was kept in elaborate low buns, which could be decorated with fabric flowers and ribbons for the evening. Necklaces were pretty short and usually fairly simple. This was the time, when the iconic black silk ribbon collar became a thing. In 1860s it usually had some small (or bigger as in this royal example) pendant on it.

Gloves were strictly necessary. For evening they were always white kid (a type of thin leather) gloves, which just covered the wrists. Silk gloves were thought of as tacky. The gloves were very simple in style but bracelets were often used with them.

Above knee stockings were always used. Usually they would be white, but they did come in all kinds of colors and small patters on the ankle were common. They would be knitted silk for the evening. Here's some silk stockings in very fun colors and patterns from 1860s England. They were secured with with a wide silk ribbon tied below or above knee. I use stockings and ribbon to secure it for everyday purposes, and it works really well. The thing is to have wide enough ribbon you can circle around the leg couple of times, so it won't put too much pressure on one spot. For me below knee works the best. Really any thin knee high stockings works for this, and white is the safest bet.

There's some options with the shoes. Both boots and slippers were acceptable for evening wear and slippers could have a heel or not. The evening shoes were less practical and fancier that your day shoes. They usually had silk as the fashion fabric, which wasn't that much of an issue, since they were used indoors.

Silk evening boots from 1860s France, silk slippers with a heel from 1855-65, and silk slippers from 1862 Austria.

Honestly, shoes won't be really seen under the skirt, so I don't think it's very necessary to get new shoes (there are shoe sellers like American Duchess who do historical reproduction so it's possible). Basically any ballerina slippers with a somewhat flat or at least round end are pretty close. Also any shoes roughly between 1830-1880 are basically accurate (minus some details) as the shoe fashion changed pretty slowly.

I hope this was helpful for at least providing some background info!

#historical fashion#history#victorian fashion#fashion history#dress history#answers#historical costuming#extant garment#1860s fashion#fashion

133 notes

·

View notes

Note

I just needed to let you know that your patchwork coat has been living rent free in my head since I saw it and I'm seriously considering starting my own.

Yesss! Good! Will it be the same cut as the 1830's one, or more like those 1860's honeycomb ones, if you've decided yet?

I love how you've lined up the stripes on those top two pieces!

Someone on instagram recently tagged me in a post about how they're starting a triangle one too, which is quite exciting! Patchwork can look so so different in different fabrics even if it's the same pattern (as evidenced by the extremely different looking extant honeycomb ones), and I look forward to seeing finished patchwork garments! In like. Approximately 1-5 years time maybe.

(Link to my dressing gown for anyone who missed it.)

#ask#sewing#patchwork#the dressing gown video has more views than any other I've posted and I hope more people start patchwork things because of it!!#fun and economical and uses up scraps!

194 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm new to the historical costuming and historybounding community and I noticed something odd and I wnated to know your opinion about it.

1850s/60s clothes are essentially nonexistent in the community at large. Every now and again, someone will make a Little Women inspired something, but that's it. No one seems to dislike this period, but no one seems to love it either?

Which confuses me so much because I would have assumed it to be one of the most popular styles, the way that the 1890s are in actuality.

Oh yeah, you're absolutely right! It IS rather underrepresented.

My main thought is that it's less practical for potential everyday modern wear than the later 19th century, and therefore less popular. Hoop skirts are marvelous, and not as huge or unwieldy as people like to think, but they're still not terribly practical for most people's lives nowadays. I adore the late 60s/early 70s elliptical skirt and bustle styles, but taking up so much space on the train would get me intense dirty looks at minimum. So I tend to aim a bit later- Natural Form or 1880s/90s transitional.

(Though I admit, it IS rather frustrating that almost every other daily wear historical costumer does 1890s/early 1900s. I want tips for styling a blouse so it looks less Edwardian Shirtwaist and more 1879 Blouse Waist, damnit! I can look at ads and photos and extant garments and fashion plates myself, but I'd love to have living people to compare notes with.)

I can recommend two bloggers who do more 1860s stuff, though: The Quintessential Clothes-Pen (Quinn Burgess) and Plaid Petticoats (Raven Stern). They do other eras as well, but it's not as much of an 1890s washout as popular costubers sometimes tend to be- with no hate intended to those people; that's just what they like to make! Neither of the bloggers I recommended are Everyday Victorian Clothing people, so that might contribute to their era flexibility.

Best of luck in finding your 1860s dream content!

(Also, if you DO want some more practical everyday 1860s, you could try looking at 1867-69; there was a brief A-line skirt moment there that everyone forgets about, but which would be less space-consuming than hoops.)

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Very pretty but might be scratchy.

Woman’s blouse

1860s

Museum of Vancouver

#extant garments#19th century#1860's#1860s#victorian fashion#blouse#victorian#fashion history#historical fashion#history of fashion

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

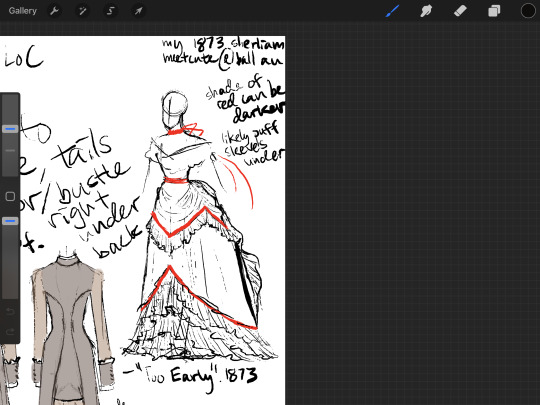

fem!William cosplay

In honor of sherliam week 2023, I'm gonna start posting about my plans for a hopefully historically-accurate cosplay of William! :D

i'm planning on designing 4 outfits: professor, noblewoman day wear, noblewoman evening party wear, and traveling wear. I'm probably going to be actually making one of the first two or both. I could also throw in a teagown, loc outfit (though i honestly think it would just be the same as canon anyways?), sleepwear, specific design for undergarments, etc, but we'll see if i'm still interested in that later

when I first came up with the idea sometime in july or august, because i am such a historical costume girly, i was like, so i would do a male one except i know that i would never wear it outside of the cosplay, which would be a waste of my money and limited energy. So, i decided to just do a female adaptation of his canon character design and made a ~1878-1879 corset, with plans to make combinations (for that sweet sweet in-character practicality), corset cover, etc. Then, as i was working on the design, i ended up coming up with a whole au/justification for an actual female ver. of william that was publicly known in-universe as a woman who identified as such with the og william also being publicly known as a girl, because if he was still a boy, then f!william would have had to cross-dress. Also, if anything i'm saying is irl historically wrong, i'm literally begging for you to tell me and forward resources about what im wrong about.

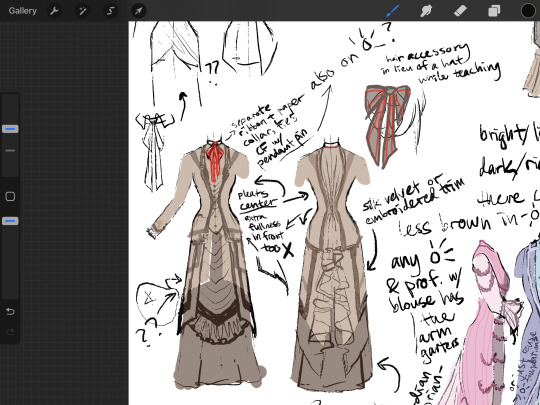

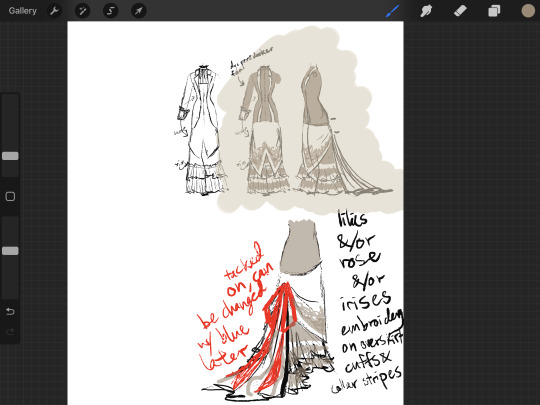

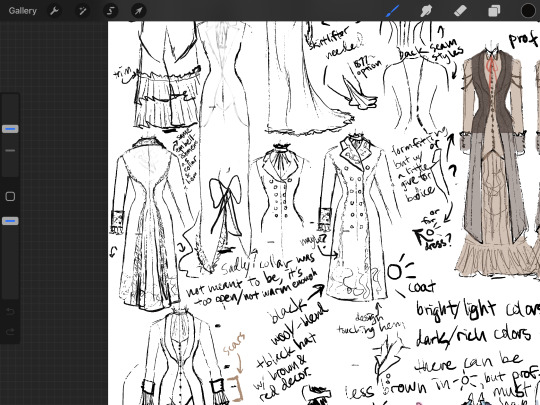

So, essentially, in the 1860-70's, specifically including ~1876 - 1879, there doesnt seem to be as much popularity towards women being highly educated through universities or being teachers at universities as it is in the later victorian era, though there already has been precedent set for a couple decades of women graduating from college. So, if a female william (f!william for short) was a well-off and decently mid-high ranking noble lady from a family with an earl/count title, it could be presumed that trying to be a "perfect noble" (wo)man would not involve being more noticeably progressive in such an eye-catching manner. However, considering that in canon william doesnt try to downplay his intelligence at all publicly, given that he is known as a mathematical genius who graduated and became a professor at a very unusually young age, even f!william would probably be stubborn enough to fully go for it and achieve the same results, with a lot more opposition from strangers. Admittedly, a woman would not have been allowed to attend Eton, because it's all-boys, and being titled a professor means that you've been hired as a professor at a university, and i imagine it'd be hard to get a bunch of likely sexist-ass old men to hire a young woman as a professor, but let's say she did manage to do it, especially with the backing of a respectable noble family name. So that means she's a ~19 y/o publicly-known-as-21 y/o to ~23 y/o publicly-known-as-25 y/o who is going to be starting to teaching mostly young men, who are almost entirely well-off to noble status, in ~1874-1878. That's the tail-end of the first bustle era and in 1876 the natural form era starts until early 1880's. So i looked at a lot of fashion plates and extant garments from this general time period to get a sense of both eras to design a dress that was first made during the first bustle era to be fashionable to that time that was then retailored to fit the natural form era's fashionable silhouette but also not being too fashion-forward since i dont think she would try to keep up with that more than necessary as it isnt her priority, because it's possible, even likely, for f!william to be more practical/frugal by choosing to have an "older" outfit retailored to fit a new era's style than have an entirely new outfit made. Side-note, there is practically no way to pass off the button-up shirt collar design as a historically-accurate fashionable lady's collar, so dont @ me about that. Currently, this is the design i've settled on for the professor design, which would be worn while teaching at Durham uni and possibly also as daywear on the days she has to go to work there.

the dominating collar scheme for all the daywear options is brown, and while i could have used more red in accordance with the canon red tie and eyes, i again know that my wardrobe doesnt do red, so that wasnt really a choice in terms of the main body of the dresses if i want to be able to wear any of it normally. This one also needs to have the color layer updated. For the professor outfit, I was keeping in mind a relatively simple/modest design- for a noble lady- but especially in the back where male students would probably see a lot of (since she would be also writing on the blackboard), because anything too complicated or eye-catching could be "distracting". i didnt want to make it too modest because the students and coworkers are also of similar social class to f!william, so there is some expectation of dressing well for her station but also not being too distracting for the young male students :/ i'm still considering toning the design down more, but im not sure how....

this is what i have for the normal noble lady daywear, hopefully appropriate year-round because i dont feel like designing a new outfit for like all 4 seasons. since it was by far more fashionable for women to wear brighter/lighter colors (usually more adorned by trims in matching/accenting solids rather than patterns for any time of year) during this time if it wasn't winter, in which case it would be dark but still rich colors, i made the browns a lot lighter to compensate for the fact that i'm trying to a. keep close to canon design and b. again, i want to be willing to actually wear it normally, so no reds or pinks as a main part. the big red ribbon will just be tacked on lightly so i can take it off when i'm not cosplaying. I also try to incorporate more of the pressed pleats trims as a nod to william's whole thing about perfectionism, precision, and preparation, as well as him being a math nerd, but like that also ties into the... 3 P's?? so *shrugs*. I also just love the trains of the natural form era so of course I had to add that here, where i can go wildly unpractical, in comparison to the professor one, which does have to account for a good bit of walking by foot across campus and possibly through town. this is also subject to change, but i like to think it's mostly set in stone here.

i also designed a black coat as a noblewoman adaptation of the one william wears in canon, which you can see him wearing when he and albert are at adam whitely's park opening speech. I'm not entirely sure about the exact nature and design of the embellishments, but its probably going to be some amalgamation of beadwork and embroidery. i'm actually also going to be making this, straight up because i want a black coat anyways lol. too bad it's not in time for this years winter. i didnt actually draw out the design for the hat but i was planning on a black base hat with brown and red decorations to tie it to any of the daywear clothes, including the coat, and maybe with a sheer white veil in the back? that was in fashion like during at least the mid 1870's. I'm also adapting the cane to an umbrella/parasol. while it'd make more sense to be a delicate litle parasol, i already have a normal-sized black umbrella with a silver metal handle, so that's like a perfect prop that mimics the dark wood cane with a metal handle that william uses in canon, though my umbrella doesn't have a sword hidden in it haha.

also, as a fun aside, in 1873, there was a brief trend for women to wear a ribbon choker that tied in the back with long tails as an evening wear accessory. so this is a sketch of a painting's outfit, dont remember the name though, that was painted in that year. Correction, I just saw that I wrote it down and its name is “Too Early”. I couldn't help but think up a fun little au of an au where f!william, who would be 18 y/o publicly-known-as-20 y/o, was at a ball and sherlock, male or female? (though i think a female sherlock would be kind of weird considering his canon bias that women are emotional, not as logically intelligent, and delicate :/), was also dragged there by mycroft or something when he decided?? to briefly visit england instead of presumably??? staying at whatever college he was studying at in paris. So, i was originally thinking that it would be such a cool image of sherlock lightly grabbing the tail ends of a red ribbon choker that f!william was wearing with a similar vibe as that sherliam manga vol. 14 cover art, as william turns to look over her shoulder at sherlock. But then, i obviously had to justify it to myself, so i came up with the whole above scenario and i guess they ended up meeting and becoming interested in each other a la canon but earlier and at some point in the night, william was teasingly staying (physically) one step ahead of sherlock and the image is when sherlock finally managed to catch william.

so i guess i'll post updates as i go? i'm definitely estimating this to be a year(s)-long project, considering all the research, patterning, and sewing i'll be doing. i'm also planning on doing a photoshoot with the cosplay when i'm done, so i'll be posting those whenever i have them ready.

edit: I just briefly skimmed a little of the history of female scholars, and apparently the first one to become a professor during the Victorian era is credited to Edith Morley, in 1908 at the age of 33, though there were some other women who also attended a male-dominated college around the same time as her in the 1890’s. Thus, for f!william to have been able to get that professorship or even attend and graduate from a college with a proper degree ~1869-1873, that would have been seen as even more extremely radical, which would have made her stick out in high society in a way that would make it harder to convince targets like lord Enders that she was similarly elitist and a “proper” noblewoman. She also would have had to convince both count Rockwell, her guardian, and the college itself to allow her to attend at ~14 y/o publicly-known-as-16 y/o and maybe even graduate with a proper degree, probably through a lot of machinations on her part, not to even mention being a professor. The only advantage to be found is that she’s seen as a noble, so there is some influence to exert to match male-dominated college chairs.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blue silk dress, ca. 1867, French.

Designed by House of Depret.

Met Museum.

#womenswear#extant garments#dress#silk#19th century#france#met museum#Depret#house of Depret#1867#1860s#1860s dress#1860s France#1860s extant garment#blue

427 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know this is authentic, but the plaid is just so far out of scale for a human body - used buggy salesman, perhaps?

Suit

1860s

England

LACMA (Accession Number: M.2010.33.9a-b)

901 notes

·

View notes

Text

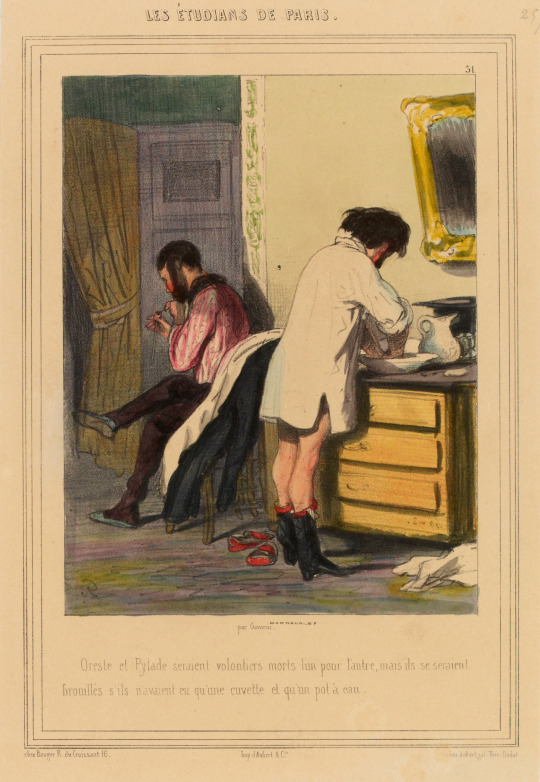

A circa 1840 print by Paul Gavarni (Paris Musées) dated 1839-1841, showing two Parisian students in their less than ideal quarters. The caption reads, "Orestes and Pylades would gladly have died for each other, but they would be at odds if they had only had a basin and a water jug."

It's another wonderful look at early/mid 19th century men's underwear, and the long shirt of the man washing his face is reminiscent of this (undated, 19th century) extant garment in the collection of the Musée de la Chemiserie et de l’Elégance Masculine:

I have been trying to date this particular shirt. The relatively plain front and lack of frills makes me think it's not very early 19th century—but Phillis Cunnington and C. Willett Cunnington's book The History of Underclothes has extant shirts that look like this from c. 1795-1800 and 1813. They quote the Beau Monde magazine in 1806 and 1807 promoting shirts without frills. (But some men clearly were wearing shirt frills, if you have ever seen a portrait of a Napoleonic/War of 1812 era officer).

The Story of Men's Underwear by Shaun Cole has some more clues dating this shirt, namely that "after 1850 the bottom of the shirt was curved rather than square cut."

So is this an 1840s shirt? It does look like the student's shirt in the Gavarni cartoon above, and here another Gavarni dated 1840-1841 (also Paris Musées):

(I THINK they just went swimming? The caption is about how they have to hurry up for the dinner bell or their aunt is going to be annoyed).

Finally, the Musée de la Chemiserie is located in an 1860 shirt factory, could this be one of their own creations, despite the straight cut bottom? It's a beautiful piece of craftsmanship. While it seems like all 19th century men's shirts are pretty large, compared with their 21st century descendants, they did become more tailored and fitted over time:

Men’s shirts had traditionally been made from a series of rectangles and squares, which resulted in a voluminous garment. By the mid-nineteenth century, a desire for closer fitting garments led to the development of patterns that allowed shirt makers, tailors and the home sewer to produce well fitting garments. In 1845 a scale pattern was featured in the Journal des Demoiselles with complex written instructions that ended with the statement ‘If you succeed, be proud! Because ‘a shirt without a fault is worthy of no less than a long poem’.” By the 1850s, tailors were applying their pattern drafting systems to shirts and tailors and other producers strove to introduce developments that made their shirts closer fitting and more comfortable. Patterns for shirts were included in magazines aimed at men such as Devere’s Gentleman’s Monthly Magazine of Fashion and The West-End Gazette of Gentlemen’s Fashions, as well as trade journals such as The Tailor and Cutter. In 1871, London shirt-maker Brown, Davies & Co. registered a design for “The Figurative Shirt”, which buttoned all the way down the front, removing “the old and objectionable way of putting on the shirt by putting it over the head”

— Shaun Cole, The Story of Men's Underwear

#1840s#fashion history#dress history#men's fashion#paul gavarni#historical men's fashion#shirts#victorian#july monarchy#fashion#undergarments#19th century#shaun cole#phillis cunnington#cecil willett cunnington#extant#Eighteen-Forties Friday

196 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wedding dress, 1867

From the Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Ooh I didn't know that! They're so cute!

Top 5 historic clothing items we should bring back into style (stockings on men, big cuffs on coats etc.)

Well I am very biased, because my everyday clothes are mostly 18th century menswear inspired, but for a list as short as 5 it's good to narrow it down!

1. 18th century shirts. Big puffy soft linen shirts. Best shirts. Comfiest shirts. Though tragically, since they get softer with more washing, they're at their absolute most comfortable right before they wear out.

(This one's from the post where I copied the tiddy-out violinist painting.) Besides being the nicest softest comfiest, they're also the most economical, being made entirely from rectangles. And they're versatile, they look good with lots of different garments! Someday I will do a very detailed youtube tutorial for my machine sewn shirt method. I've done so many now that I think I've finally got it down.

2. Adjustable waistbands. Why did this ever stop being a thing? 18th century breeches have lacing at the back, then in the 19th century trousers have a buckle tab. Now they do not, even though we're all still humans with bodies that change. (These are my orange silk breeches)

Do you know how many hours of my life I've spent taking in or letting out the waist seams of modern trousers? I don't know either, but I've been an alterations tailor since 2019, so it's got to be a fair amount.

All that waist altering wouldn't be necessary if they still made them adjustable! Waistlines fluctuate, so too should waistbands!!

3. Shoulder capes attached to coats. This was a thing in the late 18th century, and in the 19th, and I think into the early 20th too. It adds extra protection from the rain and snow, and it looks cool.

(c. 1812, The Met.)

(c. 1840-60, MFA Boston. The cape on this one is detachable)

You can make them long or short, and stack them up like pancakes or just have one. I've got 2 small ones on my corduroy coat, and one on my dark blue wool. Both cut from almost the same 1790's-ish pattern.

I also want to give a shoutout to fitted sleeves! I love me some two piece sleeves with a distinct elbow! And the coat pockets were bigger back then.

4. Indoor caps. I don't care what era or how fancy you go with it, I just want people to wear caps indoors when it's cold! This one's super simple, it's just a tube of linen tied with a ribbon.

(Detail from Le Marchand d’Orviétan ou l’opérateur Barri by Etienne Jeaurat, 1743.)

If it's cold in your apartment you need slippers for the feets and a cap for the head. Speaking of which.

5. Medieval hoods. This one is wayyy outside my usual era, but the wintery below-freezing weather has just started here and the knit hat I've been wearing isn't quite long enough to cover my ears. I want to make a simple hat with ear flaps, but I also wouldn't be opposed to trying to work something vaguely similar to this into my wardrobe. It looks so warm!

(Image source. Also she has a printable pattern available!) I actually made one of these once, an entire decade ago. But it was scratchy blanket wool and I've since given it away.

That's some of the main things I think we should bring back! There are lots of other things too, like men's nightgowns, and waistcoats with little scenes embroidered on them, but for this list I tried to be mostly practical.

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Afternoon Dress

1874

United States

This dress was made from a paper pattern bought in Paris in 1874. Extant garments created from the early days of this type of garment are rarely identifiable. Sized paper patterns were introduced by Ebenezer Butterick (1826-1903) in 1863 and quickly spread to many different companies across the United States and Europe. Being able to create stylish garments at home by sewing machine (which was invented in 1790 but wasn't affordable until the 1850s) revolutionized fashionable dress for the masses. This particular dress has distinctive features of its period such as heavy trim and decorative pockets. The bustle silhouette, although primarily associated with the second half of the 19th century, originated in earlier fashions as a simple bump at the back of the dress, such as with late 17th-early 18th century mantuas and late 18th- early 19th century Empire dresses. The full-blown bustle silhouette had its first Victorian appearance in the late 1860s, which started as fullness in skirts moving to the back of the dress. This fullness was drawn up in ties for walking that created a fashionable puff. This trendsetting puff expanded and was then built up with supports from a variety of different things such as horsehair, metal hoops and down. Styles of this period were often taken from historical inspiration and covered in various types of trim and lace. Accessories were petite and allowed for the focus on the large elaborate gowns. Around 1874, the style altered and the skirts began to hug the thighs in the front while the bustle at the back was reduced to a natural flow from the waist to the train. This period was marked by darker colors, asymmetrical drapery, oversize accessories and elongated forms created by full-length coats. Near the beginning of the 1880s the trends altered once again to include the bustle, this time it would reach its maximum potential with some skirts having the appearance of a full shelf at the back. The dense textiles preferred were covered in trimming, beadwork, puffs and bows to visually elevate them further. The feminine silhouette continued like this through 1889 before the skirts began to reduce and make way for the S-curve silhouette.

The MET (Accession Number: 2009.300.777a–c)

#afternoon dress#fashion history#historical fashion#1870s#bustle era#gilded age#19th century#united states#1874#brown#silk#embroidery#up close#the met

279 notes

·

View notes

Text

no but seriously. there are so many holes in people's social history knowledge and myths that get repeated by trusted scholars and institutions

(it's almost always social/micro-level history, because Great Man history has been the most popular model to teach for so long)

if it's halfway believable, people will just...not question it

I went to an exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts here in Boston- a world-class museum! -a few years ago. they displayed a very small corset, laced fully closed, with a placard implying that All Corsets Were Thus and All Women Suffered Because Of Them

in the NEXT ROOM. was a video of cancan dancers from the 1890s. all of them were, to my eye as a clothing history researcher, clearly wearing corsets. all of them were dancing with all the energy and enthusiasm that characterizes the cancan, smiling broadly, clearly not winded or pained in the slightest

my mind immediately goes "wait this makes no sense. even if I didn't know what I know about corsets, if all women wore them and these women are doing pretty athletic dancing, doesn't that negate the text next to that corset? and speaking of that corset, why aren't we looking at the lack of wear on it? it looks pristine- why is there no comment on how that indicates it was not frequently worn? why is there no lacing gap, as extant sources indicate was normal? why is there no consideration of survivorship bias in why this garment has survived to end up in a museum?"

"why aren't the curators of the exhibit doing the mental math of Very Small + Hardly Worn + Lacing Gap + Lasted Long Enough To Be In A Museum Collection and coming to the conclusion of Not Normal?"

and honestly you see it with all kinds of myths. I know it mostly with the clothing stuff because that's my forte- I've had tour guides at house museums tell me that fire screens exist to stop women's wax makeup from melting (not true) and that hoop skirts catching fire was the #1 cause of death for women in the 1860s (VERY not true). I was working with a curator to examine some garments in a certain collection, made a joke about health panics around women's clothing in the 1890s, and heard her say in 100% seriousness "well, I mean, it WAS dangerous and bad for you." zero elaboration. stated as if this were an absolute fact. a museum curator at a huge historical organization

nobody's perfect! nobody knows everything! I believed women weren't allowed to have our own bank accounts or credit in our own name until the 1970s, and only just found out that that's not exactly true a week ago! but the lack of interest in questioning what you think you know- even if you've been trained to flag anything that makes a neat, tidy story in history -astounds me

also what's with this late historical trend of people who study pre-19th century eras blaming everything negative on the Victorians?

"stays weren't impossibly painful torture devices!" right!

"that's something those HORRIBLE BARBARIC VICTORIANS did!" NO

"the Medieval period wasn't actually a dung-caked hellhole most of the time!" it was indeed not!

"the STUPID DUMB BRAINLESS VICTORIANS came up with that idea!" INCORRECT

"the Victorians invented colonialism!" ARE YOU EVEN LISTENING TO YOURSELF AND HAVE YOU HEARD OF THE TRIANGLE TRADE

#we had a guy come in to do interpretation at one of my museums the other day#and I was anxious about it and told one of my coworkers#and they were like 'well they let him in- surely he knows what he's talking about!'#and I was like 'the text on the wall in the bathroom downstairs says that everyone wore lead-based makeup and smelled terrible'#'in 1770s Boston'#the higher-ups are okay with us KNOWINGLY spreading social history misinformation. I don't trust them.

571 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m reading The Stammering Century, a book about 19th century American fanatics and radicals (written in the 1920s).

I can’t resist quoting a long stretch I just read, which contains (among other things) some echos of discourse I see on this website all the time today:

Emerson, consequently, is the prophet of the next generation of reformers: the prophets of the will; the priests of the sinless religion based not on Christ but on self; the mind healers, and optimists, and teachers of self-confidence in fourteen lessons; the mystics of success. When we come to them, we see how, out of the vast range of Emerson’s ideas, and out of his high conceptions of the gentleman and the man, they managed, by skillful selection, to create the bounder with an aggressive ego and how, out of a lofty mysticism, they drew a silly one. From that, at least, the radicals of his own time were deterred by his severe presence and by his hostility. They drew from him a single encouragement: to trust themselves against society. In some of his most impressive sentences he spoke of divine justice: “It is impossible to tilt the beam. All the tyrants and proprietors and monopolists of the world in vain set their shoulders to heave the bar. Settles for evermore the ponderous equator to its line, and man and mote, and star and sun, must range to it, or be pulverized by the recoil.” That type of retribution they understood, for they all believed themselves instinctively at one with nature, and privy to its secret intentions. They could trust themselves, because they—and they alone—trusted nature.

The radicals of the 1840’s and after created the type-radical of our own time. The changes which words undergo have confused us somewhat for, in 1840, the radical was called a reformer and, in 1928, the reformer is not a radical and the radical is called a Red. In 1914, before Prohibition and Bolshevism had blurred the picture in the back of our minds, the radical was, in our imagination, a comparatively harmless crank, given to fads, strolling about in white garments, eating nuts, talking of love and beauty. He was, in reality, already turning into something harder and more dangerous to settled convictions, but the cartoonist lagged a little behind the fact, and we still thought of the radical as he was in 1840. The reformer, meanwhile, had undergone another transformation. In 1840, that name was given to the lofty soul who, at the risk of martyrdom, was ready to lay the ax at the root of every human institution:

“The trump of reform,” wrote the Dial in 1841, “is sounding throughout the world for a revolution of all human affairs. The issue we cannot doubt; yet the crises are not without alarm. Already is the ax laid at the root of that spreading tree, whose trunk is idolatry, whose branches are covetousness, war, and slavery, whose blossom is concupiscence, whose fruit is hate. Planted by Beelzebub, it shall be rooted up. Reformers are metallic; they are sharpest steel; they pierce whatsoever of evil or abuse they touch. Their souls are attempered in the fires of heaven; they are mailed in the might of principles, and God backs their purpose. They uproot institutions, erase traditions, revise usages, and renovate all things. They are the noblest of facts. Extant in time, they work for eternity; dwelling with men, they are with God.”

So he stood, ax uplifted, at the threshold of the Gilded Age, and the age paralyzed his arm. In 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, the radical-reformer—the ultraist as he was called—had reached the end of his tether. In that notable success was the seed of his failure, for it meant that the most extreme of radical measures had succeeded without destroying society, and without much aid, even, from the radicals. Until 1860, the infidel, the suffragist, the Perfectionist, the experimenter in Communities, all were somehow tolerated by society provided they were not also Abolitionists. Abolition was the Bolshevism of that time in the North as well as in the South. The opponents of slavery avoided Garrison because he prejudiced their cause, their compromises, their projects for restoring the negro to Africa. Our school histories have given us the picture of a North of Abolitionists and a South devoted to the “peculiar institution.” We reject the bitter facts that neither Lincoln nor his party was in favor of abolition; that both might have made slavery permanent to save the Union; that New England mobbed anti-slavery meetings; that liberals of all types avoided the taint of Abolitionism; that Lovejoy was not killed by a true southern mob; that only a pitiful handful of fanatics voted for an abolitionist president; that Quakers and New England Congregationalists supported slavery; that to all right-thinking people John Brown and William Lloyd Garrison were anathema; and that a good Bostonian shrank from being seen even with so eminent a negro as the orator, Frederick Douglass. The Abolitionist was the arch-enemy of established society. When his cause was carried by the accident of a war which he did not inspire, all other causes were shaken. It should not have been so: one triumph should have led to others, and might have done so if the field of operations had not changed. Causes went into politics. After the Civil War we see a succession of third parties with programs of social reform. And as the scandals of the age rose out of economic exploitation protected by politics, the reformer, too, had to shift his ground.

Beginning with the ’70’s, the personal reform of temperance was transformed into the political reform of prohibition, and the radical-reformer of the 1840’s reappeared, a decade later, as the protagonist of honesty in politics, to be followed closely by the muck-raker and eventually by the Progressive. The radical element in the reformer had separated out of the composition. By fissure, the man of the 1840’s had become two: the radical attached to abstract ideas, the reformer attached to politics. The return of Roosevelt to orderly Republicanism, the liberal enthusiasm for Wilson and the Peace, put an end to that type of reformer. But, in the meantime, another had risen, antipodal in every superficial respect to the reformer of 1840, yet psychologically close to him. The keyword of 1840 was “abolish”; of 1900 “improve”; of 1926 “prohibit.” At the moment it seems that only the last was successful.

The early radical-reformer was, strangely enough, a sympathizer with the supposed motive of the modern prohibitionist; that is, he usually disliked liquor in all its forms. What he would have despised utterly is the prohibitionist’s method; for the 1840 radical was not a legalist, and his way of banishing liquor was a transcendental kind of local option. Association was another key-word of the time (Alcott preferred Con-sociation); and when an association was made, a colony founded, the members could banish liquor and tobacco if they chose, and any new member would naturally accept the laws of the Community in that respect as he did in respect to property or wives. The radicals corresponded in time to the Washingtonian Movement, the great effort to impress temperance on Americans through the testimony of reformed drunkards. This movement was as personal as the Anti-Saloon League was impersonal. It required a moral conversion, and it offered individual happiness, invoking no law but the moral law, appointing no bureaucracy, and carrying on no lobby. This was the typical movement of the time, trusting to moral suasion, appealing to the individual, and involving no compulsion. It wanted to abolish the drunkard without abolishing the drink. The communist experiments of the same time wanted to abolish private property and unequal wages—for themselves. The vegetarians desired an end to the universal wrong done to animals, but their chief aim was to persuade people to stop incorporating the flesh of beasts into their own bodies. The suffragists demanded the right to vote; they did not try to take that right away from any man. Only the Abolitionist pure and simple attacked a right or a privilege and he, too, worked on the basis of equality, for he did not propose to let the black man keep the white man as slave. To abolish a pernicious institution, and then to leave men and women to their own devices, was the ideal of the libertarian radical, and whatever institution he founded or approved was one which protected liberty.

Contrasted with the sour figure of the modern Prohibitionist, the reformer of 1840 is a happy and generous person, trusting human nature in its “natural” state, eager to allow every liberty to mankind, and never happy himself so long as injustice and unkindness remained on earth. In that view, the radical comes to our mind in the same group-picture with the martyrs of liberty, the saints, and the prophets. We imagine the contempt an Alcott or a Greeley might have had for the tyrannical practice and mean devices of a censor of literature, or an Anti-Saloon Leaguer, or a Tennessee legislator of to-day, and it seems to us that a miasma of intolerance has spread over our own time, choking our finer sensibilities and stunting the growth of great spirits.

For the sake of convenience, we may take the period 1800–1840 (roughly) as the one in which the revivalist worked on the radical-reforming temperament and created communities; and the period from 1840 to our own day as the one in which the radical-reformer turned into the prohibitory-reformer. Stated even in these terms, the marks of degeneracy become plain. It would be premature to stress the point. But it may be noted now that the degradation of radical doctrine is probably due in part to the vast failure of radical movements when they founded communities. At that point, they touched America with the sharpest edge: they challenged the system of production, of capitalism. Had they made any success for themselves there, they might have developed more happily, with the respect which America (and possibly Europe) pays to whatever establishes itself. But they failed, conclusively. Except for the Shakers and the Rappites of an earlier, religious day, only one community gave any indication of success. This was Oneida, and it, too, was based on a religion. Many years later, Zion City seemed successful, came close to bankruptcy, and was saved, but it was not a true community.

The others, the communities founded on faith and hope perished without grandeur. Several records exist, most of them based on fragments of a manuscript written by a forgotten Scot whose practical mind seems to have been fascinated by all these impracticalities. On one side is a list of lovely names, names of abstract virtues, of philosophical ideals, of pious devotion; on the other side is the deadly record of bankruptcy and dispersal. One wishes they had been as intelligent as they were gallant, as beautiful as they were fanatic. But making all reservations, these communities still have a touch of human dignity, and it seems hard that they should have struggled and perished and left their name to be exploited as bait for bad furniture and limp leather books.

In the period of the ’40’s, the most famous experiment was Brook Farm; the most numerous experiments were the Fourierite phalanxes. The stories of these colonies are so well known that I have preferred to choose two others: Ballou’s Hopedale, which in its meekness and dullness exhibits all the lesser vices of communities, and Alcott’s Fruitlands, where every idiosyncrasy flourished and all the absurd impracticality of the reformer when cultivating the land was exposed.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stays!

A few discord folks were asking me about stays, so I figured I’d make a post with some basic info. There are a lot of other posts and resources around, but I like info dumping, so here is another one.

First: I am not a historian. I am a seamstress, a lover of history, and a wannabe historybounder(that’s why I learned to sew twenty years ago before it was really a thing), who has dabbled in historical interpreting/reenacting. So, I might be wrong about things. There are many, many people who know more than me, and if you are one of them please feel free to correct me. Second: This is all really basic information, so please to ask me questions if you want to know more. I’m happy to share what I know, and what I don’t know I will research.

What are stays?

Stays are a supportive garment worn to A) support the bust and B) help create a fashionable silhouette. They are generally an undergarment, but can in some situations be worn as an outer layer. They are always worn over a shift(a chemise in later periods). The earliest extant pair of stays is known as The Effigy Bodies(bodies being the term for stays prior to the mid/late 1600s) which is part of Elizabeth I funeral effigy. Bodies is an older term for stays, I do not know when the one became the common choice.

What’s the difference between stays and corsets?

A corset is also a supportive garment worn to support the bust and create a fashionable silhouette. A few key differences are regarding how the support and shaping is done ie materials used in construction, and the type of shaping done. Almost all stays create a conical or columnar shape while corsets generally create an hourglass or curved shape, the degree of which depends on the particular period. Regarding materials, stays are usually boned with reeds, quilting or cord, while later corsets use baleen and/or steel in addition to cording. Stays can be either front or back lacing, or both; I do not think I have ever heard of a corset lacing in the front. Stays are usually spiral laced with a single cord tied at the top or bottom(usually top.) Corsets are cross laced with one or two cords and tie at the waist.

There is some crossover between the terms and while stays are sometimes refered to as corsets, an 1860s corset will never be called stays. There is the ‘transition period’ which is late 1780s through around the mid 1830s when the methods of construction and material use was in a state of flux.

While stays would sometimes be outerwear, especially for women working in very warm or labor intensive places(farms, kitchens), a corset is always underwear.

Aren’t they uncomfortable and unhealthy?

Not at all! Many boob-having people actually find stays, and corsets for that matter, more comfortable than modern bras. Provided that your stays fit properly and are not laced too tight, they are extremely comfortable. The reason people think otherwise is because they either laced too tight, or more likely are wearing a pair that doesn’t fit correctly. There are tens if not hundreds of small measurements that go into a pair of stays. There is more to proper fit than bust, hip, and waist diameter. Torso length, shoulder width and depth, waist-to-hip length are some of the more important measurements for getting a good fit. That’s not to say that every pair needs to be custom-made, Redthreaded do an amazing job at making historically accurate stays in a range of standard sizes that will be comfortable for most women. A custom pair will always feel better though.

As for healthy, again if they are laced and fit properly, no there are not health risks for the majority of people. The idea that corsets, and by extension stays, are unhealthy was started as a marketing campaign in the early 1900s to sell the new ‘health corsets’. You can learn more about this in Bernadette Banner’s videos (1, 2) where she explains it very well, including sources.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

White cotton dress with green beetle wing embroidery, 1868-1869, British.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

#V&A#womenswear#extant garments#dress#Cotton#beetle wing#19th century#Britain#1868#1860s#1860s dress#1860s britain#1860s extant garment#embroidery

507 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm begging on my knees... what is the difference between 1860s, 1870s and 1880s corsets if there's any... I've been looking at extant garments and illustrations all day and I still can't see what the identifiable characteristics are...

0 notes