#1794 w

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

thinking about how they got lestat in marie antoinette style on the day of "killing" him which was the fashion at the time when he "died" the first time mwah

#txt#lestat de lioncourt#iwtv#i am so slow i realised this like 2 nights ago lying awake going WAIT A MINUTE#like even a week after reading the part of tvl where she is mentioned#not sh#i know she died in 1993 or smth and he died in 1994 in the show (bc i just read both) but still#i'm live love loving it#i mean i did know this but like i realised it realised it again and no#w it's stuck u know what i mean#and therefore i have to write it to get it out of my brain so i can think of something else#edit: i mean *1793 / 1794 lmao

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Back to another time" historical fanfic

a question to all napoleonic fans out there:

What should be changed or improved if a time travel were to travel back into the Napoleonic era?

So it's no secret of mine that I've been planning of writing a historical fanfic of a surgeon leonard dunard who's a pretty big napoleonic era nerd travels back in time during 1794 the siege of toulon. I've been kind struggling piecing this story together because of the not so many sources that I can go off

I just have alot of questions and not so many answers.

Now of course I'm not really thinking about giving napoleon the biggest W of all time there are going to be struggles but I think we can all agree that the peninsular wars and the attack to Russia can be avoided.

But I'm not only thinking of the way of how napoleon could've won but I was also think of how our modern surgeon Leonard could improve the medical field more.

I know that our boy larrey is definitely going to be involved since he was in most of the campaigns.

So I will just write down my questions under here and hope that some of yall can answer it I'll even organize it from which battle/chapter it would be used for you can ask me to explain further if some of it doesn't make sense.

Siege of toulon:

-how would a young surgeon inlist themselves into the medical field of the army?

-what was expected from a chirurgien sous aide major?

-what were the major issues the in the 18th century medical field? And how can they be fixed?

- how could dunard(oc) meet larrey? (So in what way could they have met eachother and stay in contact without napoleon introducing them to eachother)

Italian campaign 1796-1797:

-was is it common practice for surgeons to be in the midst of an active battle rescuing patients ?

-could a surgeon be given command to a battalion if it was needed?

-were nurses a thing in that time? And if not how could dunard incorporate them in the medical field?

-why wasn't there symbol for the medics to indicate that they're medical staff?

Egyptian campaign:

-how did the French army handle the spreading of the plague and could it be more improved?

-if the French fleet would have won at the battle of the nile against the British fleet would the British do more to sabotage the French army? Or would they just give up?

-> and would the Egyptian campaign only have taken 1 year to finish? Instead of 3 years

Italian campaign 1800

- what if desiax lived would he and davout been a unstoppable duo?

-if messena got navy support would he have continued fighting?

-should napoleon not have split his army that much in the battle of marengo?

Napoleons reign 1804-1812

-would it have been better if napoleon didn't become emperor?

-is it possible for a surgeon to become a marshal?

-could alot of the coalitions have been avoided if napoleon took the right steps?

Now I'm asking these questions because I struggle to find answers to these questions and I genuinely want to discuss more about my history fanfic so that I can maybe make fun fic to read that doesn't completely go of the rails i do kind what to keep it "realistic" if you know what i mean. so if your interested in it as I am I would love to talk about it more ^^

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok time for a real question

Does 035's host's vision effect the mask? Like if his host has myopia does 035 also see like shit on the distance? If yes then I'm very sorry for him from my experience if you try to wear glasses w a mask on slightest tilt of a head and they're on the ground.

Does it effect the colour too? Colour blindness was document only in 1794 do you think before that 035 ever possessed a new host and was like "holly fuck why is everything so yellow"

Or in sedition tapes he snapped his neck just by will, no hands or anything, would be he do the same thing but somehow charge the structure of the eyeballs so they work correctly? (Imagine if instead of neck snap he would shoot out eyeballs at Watch lol)

OR maybe he has some sort of invisible eyeballs of his own and he's able to see even without a host. Idk Ig we'll never know

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

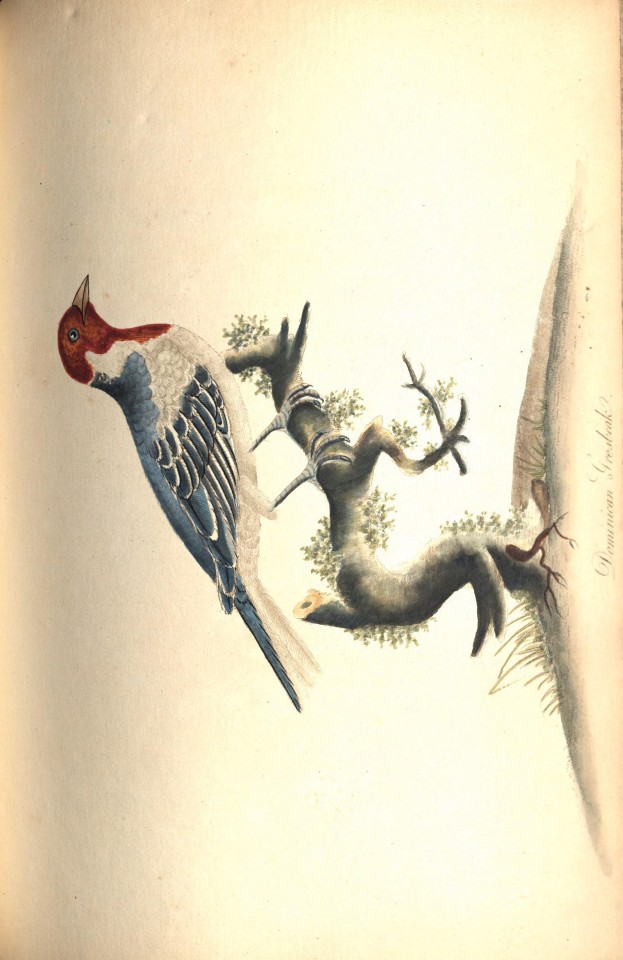

🌎 Portraits of rare and curious birds, with their descriptions: London: Printed by W. Bulmer and Co., and published for the author by R. Faulder, 1794-1799.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … February 2

1711 – The great Austrian statesman Prince Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz (d.1794) was born in Vienna. He was an Austrian-Czech diplomat and statesman in the Habsburg Monarchy.

A proponent of enlightened absolutism, he held the office of State Chancellor for four decades and was responsible for the foreign policies during the reigns of Maria Theresa, Joseph II, and Leopold II. In 1764, he was elevated to the noble rank of a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire. Single-handedly he engineered an alliance between traditional enemies France and England.

Eccentric, arrogant, conceited and always happy to hear the sound of his own voice, he is said to have had a virtual harem of young men.

1859 – Havelock Ellis, British psychologist and sexologist, born (d.1939); Ellis's monumental seven-volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1897-1928) was not only of the greatest importance in changing Western attitude toward sex, but has influenced almost all writers ever since. Given the nature of his major interest, he was more than entitled to a full-fledged fetish all his own.

From the beginning, his marriage was unconventional (Edith Ellis was openly lesbian), and at the end of the honeymoon, Ellis went back to his bachelor rooms in Paddington, while she lived at Fellowship House. Their "open marriage" was the central subject in Ellis's autobiography, My Life. According to Ellis in My Life, his friends were much amused at his being considered an expert on sex considering the fact that he suffered from impotence until the age of 60, when he discovered that he was able to become aroused by the sight of a woman urinating. Ellis named the interest in urination "Undinism" but it is now more commonly called Urolagnia.

Ellis's Sexual Inversion, the first English medical text book on homosexuality, co-authored with John Addington Symonds, described the sexual relations of homosexual men and boys, something that Ellis did not consider to be a disease, immoral, or a crime. The work assumes that same-sex love transcends age as well as gender taboos, as seven of the twenty one examples are of intergenerational relationships. A bookseller was prosecuted in 1897 for stocking it. Although the term 'homosexual' is attributed to Ellis, he writes in 1897, "`Homosexual' is a barbarously hybrid word, and I claim no responsibility for it." Other psychologically important concepts developed by Ellis include autoeroticism and narcissism, both of which were later taken on by Sigmund Freud.

1940 – On this date the American poet, critic and science fiction author Tom Disch was born (d.2008). Born in Des Moines, Iowa, as Thomas Michael Disch, he also worked under the pseudonyms Tom Disch, Tom Demijohn and Dobbin Thorpe. Disch won the Hugo Award for Best Related Book (previously entitled "Best Non- Fiction Book") in 1999, and had two other Hugo nominations and nine Nebula Award nominations to his credit, plus one win of the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, a Rhysling Award, and two Seiun Awards, among others. He is perhaps best known for his story "The Brave Little Toaster." This other works include The Genocides (1965), Mankind Under the Leash (1966), Echo Around the Bones (1967), Black Alice (1968), Camp Concentration (1968), The Prisoner (1969), 334 (1972), Getting Into Death (1973), Clara Reeve (1975), The Brave Little Toaster (1978), Neighboring Lives (1981), The Business Man (1984), The Brave Little Toaster Goes to Mars (1988), The M.D. (1991), The Priest (1994), The Castle of Indolence (1995), A Child's Garden of Grammar (1997), and The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of (1998).

Following an extended period of depression following the death in 2005 of his life-partner, Charles Naylor, Disch stopped writing almost entirely, except for poetry - although he did produce two novellas. Disch committed suicide by gunshot on July 4, 2008, in his apartment in Manhattan, New York City. His last book, The Word of God, which was written shortly before Naylor died, had just been published a few days before Disch's death.

1946 - J. E. Freeman was an American actor (d.2014), often cast in tough guy roles.

His first movie appearance was in the early 1980s actioner An Eye for an Eye in which he played a tow truck driver who minces words with Chuck Norris.

Freeman was especially known for his menacing characters roles: the evil gangster Marcello Santos in David Lynch's Wild at Heart, the terrifying Eddie Dane, ferocious gay hitman from Miller's Crossing, and the infamous scientist Wren in Alien Resurrection. Other notable apparitions in : Ruthless People, Patriot Games, Copycat and Go.

Freeman was openly gay. At age 22, he admitted his sexuality to the United States Marine Corps to avoid being drafted to the Vietnam War, leading to his discharge. He was HIV-positive from circa 1984. In 2009, he published a letter to the editor on sfgate.com, detailing his reminiscences of the 1969 Stonewall riots. He wrote poetry and had a tumblr blog (Freedapoet) dedicated to his poetry.

Freeman retired from acting in 2004. He died in the evening of August 9, 2014. He was 68.

1954 – Frank G. Ferri is an American politician who was a Democratic member of the Rhode Island House of Representatives, representing the 22nd district from October 24, 2007 until January 6, 2015. A Rhode Island native, Ferri grew up in Providence before earning a degree in business from Bryant University. His district is located in Warwick and includes the neighborhoods of Warwick Neck and Oakland Beach.

He has been a Warwick resident since 1985 and owns the Town Hall Lanes bowling alley. The former chair of Marriage Equality RI, he is openly gay. Along with Reps. Gordon D. Fox and Deb Ruggiero, and Sen. Donna Nesselbush, he served as one of four openly LGBT members of the Rhode Island General Assembly. His campaigns have won the support of the Gay & Lesbian Victory Fund.

1970 – Casey Spooner is an American artist and musician. He was born in Athens, Georgia and resides in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Spooner is openly gay. While attending the Art Institute of Chicago he met Warren Fischer. The two went on to cofound Fischerspooner in New York in 1998.

Spooner has submitted works for Deitch Projects and an album by R.E.M. A promotion for Fischerspooner's second album included an art Salon/Art Exhibition of all the images used in making of the album, this has since been linked to Warhol.

Casey joined experimental New York performance ensemble The Wooster Group in 2007, taking on the role of Ophelia's brother Laertes in their production of Hamlet (which featured two Fischerspooner songs that were composed for the show). During this time, he also began work on a third Fischerspooner album (with Warren Fischer). Entertainment was released in North America via the band's own label FS Studios on May 4, 2009, produced by Jeff Saltzman (The Killers, The Black Keys, The Sounds). An American and European Tour, known as Between Worlds, continued all through 2009. Like in other Fischerspooner's performances, Spooner was the main figure of the show.

In January 2010, Spooner distributed online his first solo work, the song Faye Dunaway, as a preview of a 2010 solo album entitled Adult Contemporary. He served as the opening act for Scissor Sisters on their North American tour. This was possible thanks to the funding provided by his fans through Kickstarter, the crowdfunding online platform. Currently, he is at home in NY after releasing his solo album, Adult Contemporary.

1979 – David Paisley is a Scottish actor, his best-known for roles are midwife Ben Saunders in Holby City and Ryan Taylor in Tinsel Town. Openly gay himself, both his characters were controversial due to their sexual orientation - a lingering kiss with his on-screen boyfriend in Holby City led to 400 complaints to the BBC.

Paisley grew up in Glen Village near Falkirk. At 15 he went to a gay youth group where he eventually met his first boyfriend. At 17, he went to Glasgow University to study physics, during which time he appeared in a community workshop and then later he went to Caledonian University to study Optometry. At 18, Paisley finally came out to his family who were supportive and helped in his efforts campaigning against the Keep the Clause campaign, a British anti-homosexual movement.

He had a long-term relationship with Alex Mercer, (with whom he shared Britain's first on-screen gay threesome scene in Tinsel Town). David also had a part in the film adaptation of David Leavitt's While England Sleeps.

He has been voted 'Britain's sexiest man' by readers of Gay Times magazine.

He appeared in the BBC Scotland soap opera River City as Rory Murdoch until December 2008, a part to which he may return.

David recently starred as Gary in the play The Back Room by Adrian Pagan at the Cock Tavern Theatre in Kilburn, London. David also starred in the successful stage production of Mumah in early 2009. October 2009 has seen him take to the stage again in the UK Tour of Over The Rainbow - The Eva Cassidy story, in which he plays the part of 'Danny Cassidy'.

In 2010 David made his directorial debut with the play The Lasses, O at the Edinburgh Festival.

2005 – Austria: Transgender Europe (TGEU) is founded in Vienna during the first European Transgender Council. This NGO works "to support or work for the rights of transgender/transsexual/gender variant people." It also runs the Trans Murder Monitoring project, which records and reports the many people who are killed each year as a result of transphobia.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interesting Papers for Week 51, 2024

Learning depends on the information conveyed by temporal relationships between events and is reflected in the dopamine response to cues. Balsam, P. D., Simpson, E. H., Taylor, K., Kalmbach, A., & Gallistel, C. R. (2024). Science Advances, 10(36).

Inferred representations behave like oscillators in dynamic Bayesian models of beat perception. Cannon, J., & Kaplan, T. (2024). Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 122, 102869.

Different temporal dynamics of foveal and peripheral visual processing during fixation. de la Malla, C., & Poletti, M. (2024). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(37), e2408067121.

Organizing the coactivity structure of the hippocampus from robust to flexible memory. Gava, G. P., Lefèvre, L., Broadbelt, T., McHugh, S. B., Lopes-dos-Santos, V., Brizee, D., … Dupret, D. (2024). Science, 385(6713), 1120–1127.

Saccade size predicts onset time of object processing during visual search of an open world virtual environment. Gordon, S. M., Dalangin, B., & Touryan, J. (2024). NeuroImage, 298, 120781.

Selective consistency of recurrent neural networks induced by plasticity as a mechanism of unsupervised perceptual learning. Goto, Y., & Kitajo, K. (2024). PLOS Computational Biology, 20(9), e1012378.

Measuring the velocity of spatio-temporal attention waves. Jagacinski, R. J., Ma, A., & Morrison, T. N. (2024). Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 122, 102874.

Distinct Neural Plasticity Enhancing Visual Perception. Kondat, T., Tik, N., Sharon, H., Tavor, I., & Censor, N. (2024). Journal of Neuroscience, 44(36), e0301242024.

Applying Super-Resolution and Tomography Concepts to Identify Receptive Field Subunits in the Retina. Krüppel, S., Khani, M. H., Schreyer, H. M., Sridhar, S., Ramakrishna, V., Zapp, S. J., … Gollisch, T. (2024). PLOS Computational Biology, 20(9), e1012370.

Nested compressed co-representations of multiple sequential experiences during sleep. Liu, K., Sibille, J., & Dragoi, G. (2024). Nature Neuroscience, 27(9), 1816–1828.

On the multiplicative inequality. McCausland, W. J., & Marley, A. A. J. (2024). Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 122, 102867.

Serotonin release in the habenula during emotional contagion promotes resilience. Mondoloni, S., Molina, P., Lecca, S., Wu, C.-H., Michel, L., Osypenko, D., … Mameli, M. (2024). Science, 385(6713), 1081–1086.

A nonoscillatory, millisecond-scale embedding of brain state provides insight into behavior. Parks, D. F., Schneider, A. M., Xu, Y., Brunwasser, S. J., Funderburk, S., Thurber, D., … Hengen, K. B. (2024). Nature Neuroscience, 27(9), 1829–1843.

Formalising the role of behaviour in neuroscience. Piantadosi, S. T., & Gallistel, C. R. (2024). European Journal of Neuroscience, 60(5), 4756–4770.

Cracking and Packing Information about the Features of Expected Rewards in the Orbitofrontal Cortex. Shimbo, A., Takahashi, Y. K., Langdon, A. J., Stalnaker, T. A., & Schoenbaum, G. (2024). Journal of Neuroscience, 44(36), e0714242024.

Sleep Consolidation Potentiates Sensorimotor Adaptation. Solano, A., Lerner, G., Griffa, G., Deleglise, A., Caffaro, P., Riquelme, L., … Della-Maggiore, V. (2024). Journal of Neuroscience, 44(36), e0325242024.

Input specificity of NMDA-dependent GABAergic plasticity in the hippocampus. Wiera, G., Jabłońska, J., Lech, A. M., & Mozrzymas, J. W. (2024). Scientific Reports, 14, 20463.

Higher-order interactions between hippocampal CA1 neurons are disrupted in amnestic mice. Yan, C., Mercaldo, V., Jacob, A. D., Kramer, E., Mocle, A., Ramsaran, A. I., … Josselyn, S. A. (2024). Nature Neuroscience, 27(9), 1794–1804.

Infant sensorimotor decoupling from 4 to 9 months of age: Individual differences and contingencies with maternal actions. Ying, Z., Karshaleva, B., & Deák, G. (2024). Infant Behavior and Development, 76, 101957.

Learning to integrate parts for whole through correlated neural variability. Zhu, Z., Qi, Y., Lu, W., & Feng, J. (2024). PLOS Computational Biology, 20(9), e1012401.

#neuroscience#science#research#brain science#scientific publications#cognitive science#neurobiology#cognition#psychophysics#neurons#neural computation#neural networks#computational neuroscience

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

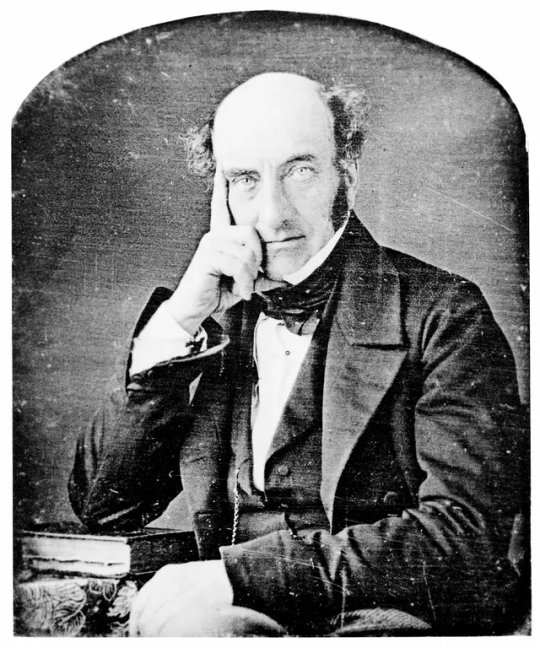

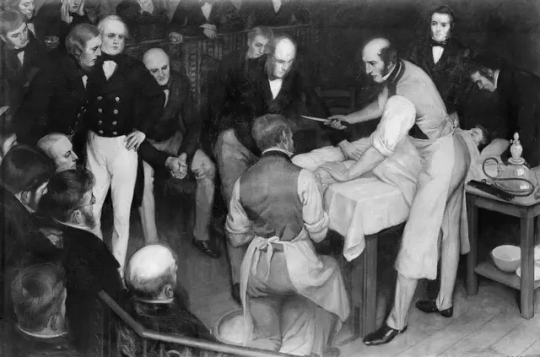

On October 28th 1794 Robert Liston, the first surgeon to use general anaesthetic in Europe, was born in Ecclesmachan, West Lothian.

Liston may be remembered for the anaesthetic but he was also the best surgeon around in the 19th century and quite a remarkable man.

Using an anaesthetic wasn't new, Alcohol is said to have been used in ancient Mesopotamia going back thousands of years, the opium poppy is said to have been cultivated and harvested by the Sumerians in lower Mesopotamia as early as 3400 BC but they were not controlled like they are today. The inventor of the safety lamp Humphry Davy experimented with the gas nitrous oxide in 1799 and found it made him laugh, giving it the term used to this day "laughing gas" Davy wrote about the potential anaesthetic properties of nitrous oxide in relieving pain during surgery, but nobody at that time did not pursue the matter any further.

American physician Crawford W. Long noticed that his friends felt no pain when they injured themselves while staggering around under the influence of diethyl ether., he didn't publish his findings until 1849 though, by then other doctors were using Ether.

Enter Robert Liston, the most skilled surgeon of his generation, so adept that he was described as "the fastest knife in the West End. He could amputate a leg in 21⁄2 minutes" this was at a time when speed was essential to reduce pain and improve the odds of survival of a patient.

The eminent English surgeon Richard Gordon said about Liston that:

"He was six foot two, and operated in a bottle-green coat with wellington boots. He sprung across the blood-stained boards upon his swooning, sweating, strapped-down patient like a duelist, calling, 'Time me gentlemen, time me!' to students craning with pocket watches from the iron-railinged galleries. Everyone swore that the first flash of his knife was followed so swiftly by the rasp of saw on bone that sight and sound seemed simultaneous. To free both hands, he would clasp the bloody knife between his teeth."

His methods were the envy and despair of other surgeons, their dislike of him meant he left Scotland and Gordon goes on to describe this in this paragraph

"an abrupt, abrasive, argumentative man, unfailingly charitable to the poor and tender to the sick (who) was vilely unpopular to his fellow surgeons at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. He relished operating successfully in the reeking tenements of the Grassmarket and Lawnmarket on patients they had discharged as hopelessly incurable. They conspired to bar him from the wards, banished him south, where he became professor of surgery at University College Hospital (London) and made a fortune"

Another wee bit of interest is his suspicions regarding Dr Knox on the body of a young woman that Knox had kept in whisky, on show in his dissecting rooms, her name was Mary Paterson and Liston suspected foul play in the manner of her death, he was right, her name was Mary Paterson and she had been "Burked" by the West Port murderers Burke and Hare in April 1828, they were paid £8 for the corpse, which was still warm when they delivered it, Fergusson—one of Knox's assistants—asked where they had obtained the body, as he thought he recognised her. Burke explained that the girl had drunk herself to death, and they had purchased it "from an old woman in the Canongate" The pair went on to sell a further 11 bodies to Knox before they were caught.

Liston on confronting Knox over the poor woman's demise is said to have "knocked Knox down after an altercation in front of his students – Liston assumed some students had slept with her when she was alive, and that they should dissect her body offended his sense of decency. He removed her body for burial." So I think we get a sense of the character of Robert Liston.

Some of Liston's most famous cases documented in a book by the aforementioned Richard Gordon were; removal in 4 minutes of a 45-pound scrotal tumour, whose owner had to carry it round in a wheelbarrow; Amputated the leg in 21⁄2 minutes, but in his enthusiasm the patient's testicles as well; Amputated the leg in under 21⁄2 minutes (the patient died afterwards in the ward from hospital gangrene; they usually did in those pre-Listerian days). He amputated in addition the fingers of his young assistant (who died afterwards in the ward from hospital gangrene). He also slashed through the coat tails of a distinguished surgical spectator, who was so terrified that the knife had pierced his vitals he dropped dead from fright.

That was the only operation in history with a 300 percent mortality!

But it is the first operation in Europe under modern anaesthesia using ether, that Liston is best remembered, on 21 December 1846 at the University College Hospital. His comment at the time: "This Yankee dodge beats mesmerism hollow", referring to the first use of ether by doctors in the US. The first operation using ether as an anaesthetic was by William T. G. Morton on 16 October 1846, in the Massachusetts General Hospital.

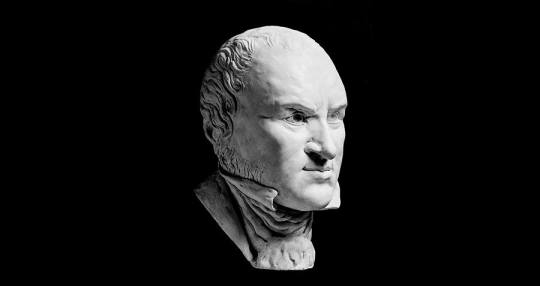

The pics are Robert Liston , the surgeon performing an amputation in front of a crowd of spectators and a marble bust of the man.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think it's you who pointed out the black writer from s1 didn't return for s2. And it made me think (with your last ask about Armand's story). I really hope they touch on his individual story outside of Lestat. They don't need to reneact Venice but some background would be good. Another point, Armand is a brown 200 years vampire roaming the street of 1700's Paris. He was at the balcony in rags around white people. And nobody gave him looks or dragged him down? Granted, both scenes were short so we haven't seen them in full yet. But I really hope they didn't fumble on how his skin color is going to impact his surroundings. Also how he responds to them. French slavery was abolished in 1794 and 1848.

i believe so far there are 2 black writers with episode credits for s2 (out of 8 eps), however unlike last season the entire directors line up is white. and i do hope they get some asian and/or south asian writers in the room not only bc armand has his own story that requires handling w/ care but they also have some token asian vamps this season and like hopefully they get something to do other than stand there?? aljflskdjf at least have them take off their shoes before going into their coffins like please that just hurts me on a deeply personal level to see that.

but also while a diverse writers room is obviously important in fleshing out characters and writing individual episodes, dialogue, etc.. the people who determine the overall arc of the show are mark johnson and rolin. they're the ones who determine which characters are going to be mains, who gets the juicy arcs, the direction of the show at large. big decisions are made by higher ups ESP in a show where they have larger universe plans.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

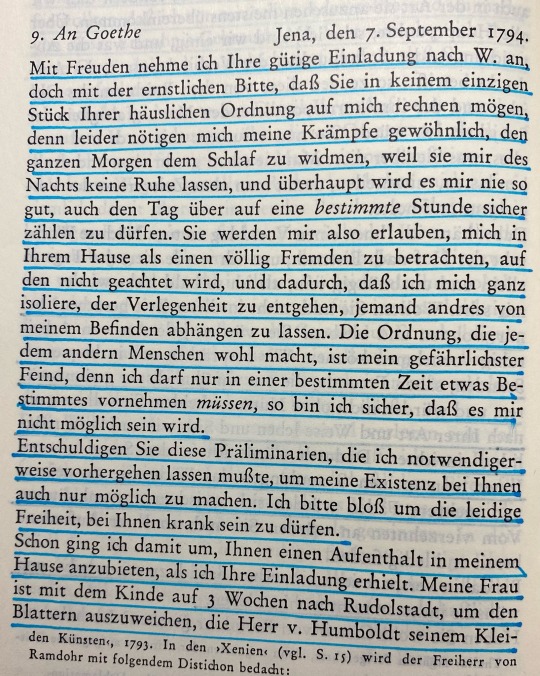

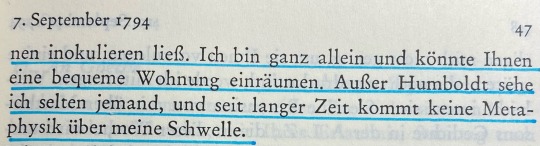

9. Brief - An Goethe

07. September 1794

,,Mit Freuden nehme ich Ihre gütige Einladung nach W. an, doch mit der ernstlichen Bitte, daß Sie in keinem einzigen Stück Ihrer häuslichen Ordnung auf mich rechnen mögen […]. Ich bitte bloß um die leidige Freiheit, bei Ihnen krank sein zu dürfen.“

Man mag sich gar nicht vorstellen, wie sehr von Schiller unter den Krankheiten gelitten und sich davon eingeschränkt gefühlt haben muss. Aber diese Ehrlichkeit gegenüber von Goethe und die Achtung vor der eigenen Gesundheit sind schön zu lesen.

#Friedrich von Schiller#Johann Wolfgang von Goethe#Schoethe#Briefwechsel Goethe und Schiller#Friedrich Schiller#Schiller#Johann Wolfgang Goethe#Goethe#Goethe und Schiller

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

1794 - Lewiston, Maine was considered part of a Plantation.

L e w i s t o n, Maine has become a new Plantation to an over-eager association of diverse racial plantation with field hands imported from afar.

0 notes

Text

The African Methodist Episcopal Church grew out of the Free African Society which Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and others established in Philadelphia in 1787. When officials at St. George’s MEC pulled Blacks off their knees while praying, FAS members discovered just how far American Methodists would go to enforce racial discrimination against African Americans. He led a small group who resolved to remain Methodists. In 1794 Bethel AME was dedicated with Allen as pastor. To establish Bethel’s independence from interfering white Methodists, Allen, a former Delaware enslaved, successfully sued in the Pennsylvania courts in 1807 and 1815 for the right of his congregation to exist as an independent institution. Because Black Methodists in other Middle Atlantic communities encountered racism and desired religious autonomy, Allen called them to meet in Philadelphia to form the AME denomination.

The spread of the AMEC before the Civil War was restricted to the Northeast and Midwest. Major congregations were established in Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Pittsburgh, Baltimore, DC, Cincinnati, Chicago, Detroit, and other large Blacksmith’s Shop cities. The slave states of Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, Louisiana, and, South Carolina, became locations for AME congregations. The denomination reached the Pacific Coast in the early 1850s with churches in Stockton, Sacramento, San Francisco, and other places in California. Bishop Morris Brown established the Canada Annual Conference.

In 1880 AME membership reached 400,000 because of its spread below the Mason-Dixon line. Bishop Henry M. Turner pushed African Methodism across the Atlantic into Liberia and Sierra Leone in 1891 and into South Africa in 1896, the AME laid claim to adherents on two continents.

Bishop Benjamin W. Arnett reminded the audience of the presence of Blacks in the formation of Christianity. Bishop Benjamin T. Tanner wrote in 1895 in The Color of Solomon – What? that biblical scholars wrongly portrayed the son of David as a white man.

The AMEC has membership in twenty Episcopal Districts in thirty-nine countries on five continents. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

It is clear that members of the family were buried at a common ground. In addition, the graves of the people that belonged to a given family preferred to design their graves using the same materials, same shape, same size and the same design, it shows the commonness among the people of the family and their uniformity. This in most cases acted as a form of identity to a certain family. For instance, the Comings family that consisted of Lydia, Benjamin, Samuel and Josiah, all had identical graves. This shows the preference of a given family having identical graves. Hereunder is the clear data about the people, their ages, sex, date of death, the type of grave one was buried in, material used to make the graves, design of the grave, the condition of the grave, and the size of the grave and little in formation of concern (Dethlefsen and Deetz 1996). Gravestone design Shape Size Material Condition Design Biography Demography Gravestone design Surname First name(s) Sex Birth Date Death date Age Type Shape Size Material Condition Design Comment Hallet Warren M 1791 8th Feb 1811 20 H D S Tall Slate G U & W Hamblen Cornelius M 1752 30th May 1811 59 H D S Tall Sandstone F U & W Howes Ebenezer M 1737 20th Feb 1811 74 Ob SDWC Tall slate P U & W Lombard Caleb M 1736 14th Dec 1811 75 H D Tall marble P U & W Rich Rabeccca F 1742 18th Oct. 1811 69 M DISC Tall Marble F M Bangs Benjamin M 1758 9th March 1814 56 Ob D Tall granite F U & W Gray Elizabeth F 1774 16th May 1814 40 H GDWC Short Slate E U & W Hamblen Ruth F 1755 20th Sep 1814 59 H DISC Tall Marble P Ch Knowles Elizabeth F 1738 29th June 1815 77 M DISC Tall Sandstone P Ch Rich Isaac M 1756 29th June 1815 59 P D Short Slate F U & W Atkins Silas M 1742 17th April 1816 84 M D S Short Slate F U & W Burges Thomas M 1748 11th Feb 1816 68 M D S Tall Slate G P Higgins Joseph M 1771 2Oth Nov. 1816 45 Ob S D Tall Sandstone P U & W Snow Tamsin M 1811 11th April 1816 5 H D Tall Sandstone G M Collins Marcey M 1814 15th May 1817 3 H SDWC Tall Sandstone G U & W Collins Mary F 1794 20th Oct.1817 23 P GDWC Short granite P U & W Gross Thomas M 1740 17th May 1817 77 P Rectangular Tall granite F R Snow Mary F 1793 9th sept 1817 24 H SDWC Tall Sandstone F M Stevens Levi M 1747 16th March 1829 82 H S D Tall Granite G P Sears Elizabeth F 1782 24th Aug 1829 47 H S D Tall granite P U & W Comings Samuel M 1807 July 1829 22 H S D Tall granite p U & W Comings Benjamin M 1817 1839 22 H S D Tall granite p U & W Comings Josiah M 1810 1810 0. 33 H S D Tall granite P U & W Comings Lydiah F 1826 1826 0.08 H S D Tall granite P U & W Damon Judy f 1750 19th Nov 1828 78 H S D Tall granite P U & W Coan Betsy f 1794 12th Dec 1821 27 P Rectangular Tall marble F Ch Hallet Charles m 1751 15 Nov 1821 70 Ob DISC Tall granite F U & W Hallet Elizabeth f 1732 9th March1821 89 H S D Tall granite F U & W Smith John C m 1783 4th Oct.1811 28 H S D Tall Marble F U & W Rider Ruth f 1791 6th Sep.1812 21 Ob Round Gothic arc Tall Granite p P Hall Bethiah f 1763 27th Sep 1813 50 H Rectangular Tall Sandstone p M Gray Elizabeth f 1774 16th May 1814 40 Oth Sharp Gothic arc Tall Sandstone f M The grave forms a sharp arch at the top and its tall. Rich Richard m 1739 1813 74 H S D Tall Sandstone f M Bangs Benjamin m 1758 1814 56 Ob Gothic discoid with caps Tall Sandstone f M Knowles Elizabeth f 1738 1815 77 Ob Gothic discoid Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Events 3.14 (before 1930)

1074 – Battle of Mogyoród: Dukes Géza and Ladislaus defeat their cousin Solomon, King of Hungary, forcing him to flee to Hungary's western borderland. 1590 – Battle of Ivry: Henry of Navarre and the Huguenots defeat the forces of the Catholic League under Charles, Duke of Mayenne, during the French Wars of Religion. 1647 – Thirty Years' War: Bavaria, Cologne, France and Sweden sign the Truce of Ulm. 1663 – According to his own account, Otto von Guericke completes his book Experimenta Nova (ut vocantur) Magdeburgica de Vacuo Spatio, detailing his experiments on vacuum and his discovery of electrostatic repulsion. 1674 – The Third Anglo-Dutch War: The Battle of Ronas Voe results in the Dutch East India Company ship Wapen van Rotterdam being captured with a death toll of up to 300 Dutch crew and soldiers. 1757 – Admiral Sir John Byng is executed by firing squad aboard HMS Monarch for breach of the Articles of War. 1780 – American Revolutionary War: Spanish forces capture Fort Charlotte in Mobile, Alabama, the last British frontier post capable of threatening New Orleans. 1794 – Eli Whitney is granted a patent for the cotton gin. 1864 – Rossini's Petite messe solennelle is first performed, by twelve singers, two pianists and a harmonium player in a mansion in Paris. 1885 – The Mikado, a light opera by W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, receives its first public performance at the Savoy Theatre in London. 1900 – The Gold Standard Act is ratified, placing the United States currency on the gold standard. 1901 – Utah governor Heber Manning Wells vetoes a bill that would have eased restriction on polygamy. 1903 – Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge, the first national wildlife refuge in the US, is established by President Theodore Roosevelt. 1920 – In the second of the 1920 Schleswig plebiscites, about 80% of the population in Zone II votes to remain part of Weimar Germany. 1921 – Six members of a group of Irish Republican Army activists known as the Forgotten Ten, are hanged in Dublin's Mountjoy Prison. 1923 – Charlie Daly and three other members of the Irish Republican Army are executed by Irish Free State forces. 1926 – The El Virilla train accident, Costa Rica, kills 248 people and wounds another 93 when a train falls off a bridge over the Río Virilla between Heredia and Tibás.

0 notes

Text

Historia europejskiego prawa karnego

Tworzenie prawa karnego w Europie to proces rozciągający się na wiele wieków, od czasów starożytnych po współczesność. Ewoluowało ono pod wpływem różnych systemów politycznych, religii i filozofii, kształtując współczesne kodeksy karne obowiązujące w państwach europejskich.

Prawo karne w starożytności Pierwsze regulacje prawa karnego w Europie pojawiły się w starożytnych Atenach i Rzymie. W Grecji obowiązywały surowe kary za przestępstwa, a jednym z pierwszych znanych zbiorów praw był kodeks Drakona, charakteryzujący się wyjątkową surowością. W Rzymie rozwinięto system prawa karnego, oparty na prawie dwunastu tablic i późniejszych regulacjach cesarskich. Wprowadzono pierwsze pojęcia odpowiedzialności prawnej, zasady procesowe oraz instytucję apelacji.

Średniowieczne prawo karne W średniowieczu prawo karne w Europie było silnie związane z systemem feudalnym i prawem zwyczajowym. Kara była często uzależniona od statusu społecznego sprawcy i ofiary. W tym okresie kluczową rolę w orzekaniu wyroków odgrywał Kościół, a sądy duchowne miały szerokie kompetencje. Powszechnie stosowano okrutne kary cielesne, tortury i egzekucje, a procesy często miały charakter inkwizycyjny.

Prawo karne w epoce nowożytnej Renesans i oświecenie przyniosły istotne zmiany w prawie karnym. Pod wpływem myśli humanistycznej zaczęto kwestionować brutalne kary i nadużycia sądowe. W XVIII wieku włoski prawnik Cesare Beccaria w swoim dziele "O przestępstwach i karach" postulował zniesienie tortur i kar śmierci oraz reformę prawa karnego w kierunku racjonalności i humanizmu. W tym czasie wprowadzono pierwsze kodeksy karne, takie jak pruski kodeks z 1794 roku oraz kodeks karny Napoleona z 1810 roku, który miał ogromny wpływ na europejskie systemy prawne.

Prawo karne w XIX i XX wieku W XIX wieku dominował trend kodyfikacji prawa karnego i stopniowego odchodzenia od surowych kar. Rozwijano koncepcję odpowiedzialności karnej i zasady winy. W XX wieku na skutek dwóch wojen światowych prawo karne objęło także kwestie odpowiedzialności za zbrodnie wojenne i ludobójstwo. Trybunały w Norymberdze i Tokio stały się kamieniami milowymi w rozwoju międzynarodowego prawa karnego.

Współczesne europejskie prawo karne Obecnie prawo karne w Europie oparte jest na zasadzie humanitaryzmu, proporcjonalności kary i ochrony praw jednostki. Państwa członkowskie Unii Europejskiej harmonizują przepisy dotyczące przestępczości zorganizowanej, terroryzmu czy cyberprzestępczości. Współpraca w ramach Interpolu oraz Europejskiego Nakazu Aresztowania ułatwia ściganie przestępców w skali międzynarodowej.

0 notes

Text

#2747 - Sargassum sinclairii

Described by Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1845, in his Algae Novae Zelandiae; being a catalogue of all of the species of algae yet recorded as inhabiting the shores of New Zealand, with characters and brief descriptions of the new species discovered during the voyage of H.M. discovery ships "Erebus" and "Terror" and of others communicated to Sir W. Hooker by Dr. Sinclair, the Rev. Colenso, and M. Raoul. London Journal of Botany 4: 521-551. He named this one after Dr Andrew Sinclair (1794–1861), a surgeon, collector, and second Colonial Secretary to New Zealand. 15 other plants are named after him as well.

The most common Sargassum species in Aotearoa, and apparently more rarely recorded along the eastern coast of Australia.

Most brown macroalgae prefer cooler waters, but many Sargassum species live in temperate and tropical oceans. A few species are pelagic - floating in the open ocean for their entire lives. The Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic is named after the large quantities of the seaweed drifting on the surface. A good number of species including the Gulfweed Crab Planes minutus and the Sargassum Anglerfish Histrio histrio have evolved to live in the floating forests.

In the last decade or so, populations of the floating seaweed have exploded, inundating the beachs of several Caribbean islands up to a meter deep. This seems to be related to fertilizer runoff from the Amazon basin.

Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand

0 notes

Text

Heidegger, Schelling y la realidad del mal

Por Collin Cleary

Traducción de Juan Gabriel Caro Rivera

Introducción: el cenit de la metafísica del idealismo alemán

En 1936 Martin Heidegger impartió un curso sobre el tratado de F. W. J. Schelling de 1809 Investigaciones filosóficas sobre la esencia de la libertad humana, al que los eruditos suelen referirse simplemente como Freiheitsschrift (Ensayo sobre la libertad) [1]. En este curso, un filósofo alemán extremadamente difícil se enfrenta a otro que también lo es. De hecho, el Freiheitsschrift es posiblemente el texto más oscuro y desconcertante de Schelling. Las cosas se complican aún más por el hecho de que el autor que más influyó en este ensayo de Schelling fue un filósofo alemán aún más difícil de leer que Schelling o Heidegger: Jacob Boehme (1575-1624), el zapatero místico de Görlitz. Schelling no se refiere ni una sola vez a Boehme en su ensayo, pero su influencia en el texto es amplia, evidente y ha sido universalmente reconocida por los estudiosos de Schelling [2].

Me he ocupado extensamente del “primer Schelling” en otro ensayo (véase En defensa de la naturaleza: Una introducción a la filosofía de F. W. J. Schelling), en el que presenté a los lectores su vida y sus escritos. Cinco años más joven que Hegel, Schelling era considerado una estrella emergente de la filosofía alemana de finales del siglo XVIII y principios del XIX. Desde 1794 (cuando Schelling sólo tenía diecinueve años) hasta 1804, publicó numerosos libros y ensayos presentando a los lectores su “sistema de filosofía”. Después de 1804, sin embargo, esta notable producción disminuyó y luego se detuvo abrupta y misteriosamente. Freiheitsschrift fue la última gran obra que Schelling vio publicada en su vida.

En 1807, Hegel publicó su Fenomenología del espíritu y en pocos años alcanzó la fama en la profesión filosófica en Alemania, para disgusto de su colega más joven. El silencio de Schelling a partir de 1809 contribuyó a crear la impresión de que ya no tenía nada que decir. Sin embargo, no fue así, pues el Freiheitsschrift fue sólo el comienzo del “segundo Schelling”. A partir de 1809 produjo una gran cantidad de obras – tratados, diálogos y conferencias –, la mayoría de las cuales se publicaron póstumamente y gran parte de las cuales estaban dedicadas a elaborar las ideas del Freiheitsschrift.

¿Por qué Heidegger retomó el ensayo de Schelling y dio una conferencia sobre él? Aunque Heidegger tiene mucho que decir sobre Schelling aquí y allá, no dedicó un curso entero a ninguna otra obra suya. Observando las exposiciones de Heidegger y la forma respetuosa, casi reverencial, en que trata el texto, se desprende que el Freiheitsschrift tuvo para él una gran importancia personal. Heidegger afirma en el curso de 1936 que se trata del “mayor logro de Schelling y al mismo tiempo [es] una de las obras más profundas de la filosofía alemana, y por tanto de la filosofía occidental” [3]. Algunos años más tarde, sus elogios fueron aún más efusivos, al referirse al Freiheitsschrift como “la cumbre de la metafísica del idealismo alemán” [4].

El comentario de Heidegger en su curso de 1936 es casi enteramente expositivo, lo que significa que, aunque interpreta el ensayo de Schelling y nos ofrece ideas que a menudo son brillantes, hace pocas críticas. La razón de ello es que Schelling le resulta afín y simpatiza con las ideas del ensayo. Cualquier lector imparcial podrá ver que Heidegger se siente como en casa en el singularmente extraño y teosóficamente inspirado Begriffswelt (mundo conceptual) del Freiheitsschrift.

En un momento temprano de sus conferencias, Heidegger hace una observación que puede considerarse crítica, aunque sólo en un sentido matizado. Cree que Schelling dejó de publicar después de 1809 porque se esforzaba – al final, sin éxito – por dar a luz ideas que en realidad no podían expresarse utilizando el vocabulario y los presupuestos del idealismo alemán. Compara a Schelling en este sentido con Nietzsche, quien, como dice Heidegger, “se quebró en medio de su verdadera obra, La voluntad de poder, por la misma razón” [5].

Heidegger no parece referirse aquí al colapso mental de Nietzsche. Más bien parece querer decir que Nietzsche se esforzaba por expresar algo en La voluntad de poder, pero no podía hacerlo dentro de los presupuestos de la tradición metafísica. Nietzsche creía que rechazaba esos presupuestos, pero Heidegger sostenía que seguía apoyándolos encubiertamente. Así pues, el trabajo “se rompió” porque era imposible seguir desarrollándolo sin trascender el propio pensamiento metafísico. Heidegger cree que Schelling dejó de publicar porque estaba luchando con la misma cuestión, sin que (al igual que Nietzsche) se diera cuenta de que era así.

Un nuevo comienzo para la filosofía

Heidegger continúa diciendo lo siguiente: “Pero esta doble y gran ruptura de los grandes pensadores no es un fracaso ni nada negativo, al contrario. Es la señal del advenimiento de algo completamente diferente, el calor del relámpago que inaugura un nuevo comienzo. Quien realmente conoce la razón de este quiebre y es capaz de conquistarlo inteligentemente tendrá que convertirse en el fundador del nuevo comienzo de la filosofía occidental” [6].

Se trata de una afirmación muy significativa. A partir del mismo año en que Heidegger pronunció sus conferencias sobre Schelling, comenzó a escribir lo que proyectó como su segunda gran obra, después de Ser y tiempo: Contribuciones a la filosofía (Del acontecimiento) (Beiträge zur Philosophie (Vom Ereignis)). Este texto, que no se publicó hasta años después de la muerte de Heidegger, se habla de un “otro comienzo” (anderer Anfang) para la filosofía. El “primer comienzo” fue con la filosofía presocrática. En Contribuciones, Heidegger afirma que “la disposición básica del primer comienzo es el asombro [Er-staunen]: asombro frente a que los seres sean y de que los propios seres humanos sean y estén en medio de lo que no son” [7].

Con el platonismo, sin embargo, comienza a producirse un cambio intelectual, un cambio denominado en los estudios de Heidegger como un movimiento hacia la “metafísica de la presencia”. Heidegger sostiene que, a partir de Platón, toda la metafísica occidental estará marcada por esta metafísica, que es esencialmente una voluntad oculta de distorsionar nuestra comprensión del ser de los seres acomodándola al deseo humano de que los seres estén (1) permanentemente presentes para nosotros, sin ocultarnos nada, y (2) disponibles para nuestra manipulación. Como veremos, el concepto de “voluntad” desempeña un papel crucial en el tratado de Schelling y es un concepto central para Heidegger [8]. Esto es particularmente cierto en el pensamiento posterior de Heidegger, en el que “voluntad” (Wille) se refiere esencialmente a la metafísica de la presencia en su iteración “final” como el “mundo de la explotación” moderno y tecnológico, en el que la voluntad es amada únicamente por sí misma [9].

Heidegger considera que la tradición metafísica occidental ha terminado con la “voluntad de poder” de Nietzsche, que expresa la esencia de la moderna “voluntad de querer”. Así pues, si algo le queda ahora a la filosofía, debe ser necesariamente “post-metafísica” y tendría que haber un “otro comienzo” o un “nuevo comienzo”. Éste es el significado de la afirmación de Heidegger de que la incapacidad de Schelling y Nietzsche para trascender el pensamiento metafísico constituye al “al calor del relámpago que da nacimiento a un nuevo comienzo”.

Centrándonos sólo en Schelling, ya que es nuestro tema central, Heidegger quiere decir que el pensamiento posterior de Schelling contenía el germen de un alejamiento de la metafísica, el germen de un nuevo comienzo, que Schelling finalmente no pudo llevar a buen término porque permaneció confinado dentro de las restricciones del pensamiento metafísico. Su pensamiento, por lo tanto, “se rompe”. Cuando Heidegger escribe que quien pudiera descubrir la razón precisa de esta ruptura “tendría que convertirse en el fundador del nuevo comienzo de la filosofía occidental” se está refiriendo, de hecho, a sí mismo.

Parece, pues, que la Freiheitsschrift fue un texto extraordinariamente importante para Heidegger. Afirma que “el núcleo esencial de toda la metafísica occidental puede ser expuesto con total determinación a partir de este tratado” [10] Así, para Heidegger, la Freiheitsschrift nos proporciona una clave para desentrañar la naturaleza de la metafísica occidental y, por lo tanto, una clave para comprender las ideas fundacionales sobre las que descansa nuestra cultura y a las que se debe su actual decadencia.

F. W. J. Schelling (Se trata de la fotografía más antigua que se conoce de un filósofo).

Tan importante era el Freiheitsschrift para Heidegger que en 1941 volvió a impartir un curso de conferencias sobre este texto. Además, hay una marcada diferencia entre estas conferencias y las anteriores. Como ya se ha señalado, las conferencias de 1936 son casi totalmente expositivas y contienen pocas críticas. Las de 1941, sin embargo, muestran una mayor distancia crítica respecto a Schelling. Al parecer, Heidegger consideraba muy importantes sus clases sobre Schelling. El curso de conferencias de 1936 fue uno de los últimos textos que preparó para su publicación antes de morir (se publicó en 1971 y Heidegger murió cinco años después). Las conferencias de 1941 se publicaron en 1991. Desgraciadamente, el texto de las conferencias de 1941 parece más bien un esbozo y a menudo es frustrantemente conciso y críptico. Las notas de las conferencias de 1936, por el contrario, contienen pensamientos totalmente elaborados, aunque con la habitual oscuridad heideggeriana. En mi ensayo, todas las citas y pensamientos atribuidos a Heidegger proceden de las conferencias de 1936, a menos que se especifique lo contrario.

Como ya he mencionado, las conferencias de Heidegger sobre Schelling poseen múltiples capas oscuras. Heidegger es un pensador notoriamente difícil, que comenta al notoriamente difícil Schelling, quien se inspira libremente en las ideas y la terminología del notoriamente difícil Boehme. Sin embargo, tomando prestada una imagen común de Boehme y Schelling, hay una luz discernible en esta oscuridad. Estos textos no son imposibles y el esfuerzo por comprenderlos es sumamente gratificante. El Freiheitsschrift, y las conferencias de Heidegger sobre él, nos proporcionan en efecto una clave para entender la metafísica occidental, tal como promete Heidegger. Espero poder demostrarlo en el presente ensayo, aunque el lector debe tener paciencia. Mucha paciencia.

La influencia de Boehme en Schelling también abre nuevas perspectivas para los estudios sobre Heidegger y para nuestra comprensión de la filosofía moderna en su conjunto, perspectivas que los estudiosos no han decidido explorar hasta ahora. Debido a que el Freiheitsschrift está tan fuertemente influenciada por las ideas de Boehme, las conferencias de Heidegger a menudo se leen como un comentario sobre Boehme, pero sólo para aquellos que ya están familiarizados con la filosofía de Boehme y su terminología única. Heidegger era consciente de la influencia de Boehme en Schelling, pero no está claro hasta qué punto conocía los escritos de Boehme [11].

Voy a argumentar que el tratado de Schelling fue una influencia importante en el pensamiento posterior de Heidegger. Si eso es cierto, entonces Boehme fue, indirectamente, una importante influencia para Heidegger. Los escritos de Boehme fueron extremadamente importantes para los románticos – por ejemplo, fueron leídos por los hermanos Schlegel, Novalis y Ludwig Tieck – así como para Schelling y Hegel. Si se puede afirmar que las ideas de Boehme también influyeron en Heidegger, entonces Boehme se convierte en una especie de “rey secreto” de la filosofía moderna, ignorado por la mayoría de los estudiosos debido a su reputación de místico y a su merecida fama de oscuro. Sin embargo, no puedo abordar la cuestión de la influencia de Boehme en este artículo.

Tratado sobre el mal

Hay otra razón más por la que el encuentro de Heidegger con Schelling tiene una importancia capital. Heidegger señala en sus conferencias que el título de Schelling es en realidad engañoso. Por el título, uno espera encontrar un tratado sobre el “libre albedrío” (en alemán, Willkür), pero Heidegger afirma, correctamente, que el ensayo no tiene “nada que ver con esta cuestión de la libertad de la voluntad”. Y continúa: “Pues la libertad no es aquí [en el Freiheitsschrift] propiedad del hombre, sino al revés: el hombre es, en el mejor de los casos, propiedad de la libertad. La libertad es la naturaleza abarcadora y penetrante, en la que el hombre sólo llega a ser hombre cuando está anclado en ella. Eso significa que la naturaleza del hombre se fundamenta en la libertad. Pero [según Schelling] la libertad misma es una determinación del ser verdadero en general que trasciende todo ser humano. En la medida en que el hombre como hombre, debe participar en esta determinación del ser, y el hombre es en la medida en que realiza esta participación en la libertad”. Luego, en un movimiento inusual para Heidegger, añade, entre paréntesis: “Frase clave: La libertad no es propiedad del hombre, sino: el hombre propiedad de la libertad” [12].

Además, como veremos más adelante, Schelling define la libertad como “la capacidad de hacer el bien y el mal” [13]. En apoyo de esta afirmación, Schelling ofrece una larga meditación sobre la naturaleza del mal, con el resultado de que la Freiheitsschrift tiene en realidad más que ver con el mal que con la libertad. Esta es una de las razones por las que el texto es tan interesante. En palabras de Heidegger: “El mal es la palabra clave del tratado principal. La cuestión de la naturaleza de la libertad humana se convierte en la cuestión de la posibilidad y la realidad del mal” [14]. El concepto del mal de Schelling es radicalmente diferente de las teorías filosóficas anteriores y es extraordinariamente fructífero. Nos da una clave inestimable para entender el punto de vista que Heidegger critica en sus escritos posteriores como “voluntad”, que está estrechamente relacionada con la metafísica de la presencia. Existen incluso fascinantes paralelismos entre la idea del mal de Schelling y el modo en que se concibe el mal tanto en la mitología clásica como en la nórdica. Schelling, que elaboró tardíamente una Filosofía de la mitología, habría estado abierto a tales paralelismos.

Por último, si injertamos la concepción del mal de Schelling en la teoría del resentimiento de Nietzsche (que constituye la base de la “moral del esclavo”) llegamos a una poderosa herramienta para comprender las motivaciones de la izquierda actual. No en vano, en el siglo XIX, los individuos que hoy llamaríamos simplemente “izquierdistas” – generalmente comunistas y anarquistas – eran calificados habitualmente de “nihilistas” (véanse, por ejemplo, las obras de Dostoievski). No hace mucho, Elon Musk describió el izquierdismo como un “culto a la muerte”. Me atrevería a decir que la mayoría de los que pertenecemos a la derecha política hemos tenido esos pensamientos: hemos intuido que el objetivo del izquierdismo es la destrucción de la vida, la salud, el orden y la misma civilización.

Pero, ¿a qué se debe esto? ¿Cómo surge algo tan perverso y pernicioso como el izquierdismo? La teoría del mal de Schelling puede darnos algunas respuestas. La explicación del izquierdismo de Nietzsche – el resentimiento – es puramente psicológica. Pero en los últimos años he empezado a sentir cada vez más que hay, a falta de una palabra mejor, alguna “fuerza” extrahumana trabajando en este proceso. Cada vez más, he empezado a pensar seriamente en “la realidad del mal”. Cuando menciono esto a muchos de mis amigos laicos de derechas, tienden a quedarse muy callados, y luego, tímida y vacilantemente, admiten que han tenido cavilaciones similares.

Creo que estoy expresando un pensamiento que ellos mismos se habían planteado, pero que no se atrevían a admitir, quizá porque sonaba demasiado cristiano. Schelling, que nominalmente era cristiano protestante, sí cree en la realidad del mal. A diferencia de numerosos filósofos que le precedieron (entre ellos la mayoría de los filósofos antiguos y medievales y muchos de los primeros filósofos modernos, especialmente Leibniz), Schelling rechaza la idea de que el mal sea una mera “privación”: una ausencia de bondad o ausencia de un principio de orden o forma. En cambio, Schelling sostiene que el mal es una “fuerza” sustantiva por derecho propio, que se opone al bien.

En esta serie – que es en realidad una continuación de mi serie “Historia de la metafísica de Heidegger” – seguiré el ejemplo de Heidegger y comenzaré por exponer los puntos esenciales del tratado de Schelling (omitiendo muchas cosas, por desgracia). Por el camino, discutiré los comentarios de Heidegger sobre Schelling. Las próximas nueve partes de esta serie estarán dedicadas a esa tarea. En las últimas cinco partes de la serie nos ocuparemos de algunas de las implicaciones de este encuentro entre los dos filósofos, al que se ha aludido anteriormente: cómo el ensayo de Schelling puede iluminar la metafísica occidental en su conjunto, las críticas de Heidegger a Schelling, la influencia positiva de Schelling en Heidegger y las implicaciones más amplias de la teoría del mal de Schelling.

Notas

[1] El título completo es Investigaciones filosóficas sobre la esencia de la libertad humana y cuestiones afines (Philosophische Untersuchungen über das Wesen der menschlichen Freiheit und die damit zusammenhängenden Gegenstände).

[2] Véase Robert Brown, The Later Philosophy of Schelling: The Influence of Boehme on the Works 1809-1815 (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 1977), 19. Se han publicado muchos otros estudios, la mayoría en alemán.

[3] Heidegger, Schelling’s Treatise on the Essence of Human Freedom, trad. Joan Stambaugh (Athens, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1985), 2. En adelante, "ST".

[4] Martin Heidegger, The Metaphysics of German Idealism, trad. Ian Alexander Moore y Rodrigo Therezo (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2021), 1. En adelante, "MGI".

[5] Heidegger, ST, 3.

[6] Heidegger, ST, 3.

[7] Heidegger, Contributions to Philosophy (Of the Event), trad. Richard Rojcewicz y Daniela Vallega-Neu (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012), 37.

[8] Para una discusión exhaustiva de este tema, véase Bret W. Davis, Heidegger and the Will (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2007).

[9] “Mundo de explotación” es la traducción de Thomas Sheehan del término Gestell de Heidegger, que es otro término para el despliegue moderno y tecnológico de la voluntad. Sheehan escribe: “Heidegger lee la actual dispensación [del Ser] como una que provoca e incluso nos obliga a tratar todo en términos de su explotabilidad para el consumo: el ser de las cosas es ahora su capacidad de convertirse en productos para el uso y el disfrute… La Tierra se ve ahora como un vasto almacén de recursos, tanto humanos como naturales; y el valor y la realidad de esos recursos, su ser, se mide exclusivamente por su disponibilidad para el consumo”. Véase Thomas Sheehan, Making Sense of Heidegger: A Paradigm Shift (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015), 258-259.

[10] Heidegger, MGI, 2.

[11] Heidegger menciona a Boehme en las conferencias de 1936. En el contexto de la defensa de Schelling contra la vacua acusación de “misticismo”, Heidegger escribe: “pero no se trata del vacuo juego de pensamientos de un maníaco ermitaño, sino sólo de la continuación de una actitud de pensamiento que comienza con Meister Eckhart y se desarrolla de manera única en Jacob Boehme. Pero cuando se cita este contexto histórico, se vuelve inmediatamente a la jerga, se habla de “misticismo” y de “teosofía”. Ciertamente, se le puede llamar así, pero con ello no se dice nada respecto al acontecer espiritual y a la verdadera creación del pensamiento, no más que cuando acertadamente se afirma sobre una estatua griega de un Dios que se trata como un trozo de mármol y todo lo demás es lo que unos pocos han imaginado sobre ella y fabricado como misterios. Shelling no es un místico en el sentido de la palabra, es decir, un embrollo al que le gusta enredarse en lo oscuro y encuentra su placer en sus velos”. Heidegger, ST, 117.

[12] Heidegger, ST, 9. Cursiva en el original.

[13] F.W.J. Schelling, Philosophical Investigations into the Essence of Human Freedom, trad. Jeff Love y Johannes Schmidt (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006), 23. Cursiva mía. He modificado esta traducción aquí y allá cuando me ha parecido que podía ser más precisa. Por ejemplo, he suprimido la práctica de los traductores de poner en mayúscula la letra inicial de “ser” (Sein). Como en alemán todos los sustantivos se escriben con mayúscula inicial, no hay justificación para hacerlo.

[14] Heidegger, ST, 97.

0 notes