#14th century ce

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Sivan Vahki, in Coolidge, Arizona, USA, is associated with the Hohokam culture. It was abandoned around 1450 CE.

Werowocomoco, in Jametown, Virginia, USA, is associated with the Powhatan, an Algonquin-speaking group. It was abandoned in 1609 after run ins with the Jamestown colonists.

Cahokia, in East St. Louis, Illinois, USA, is associated with the Mississippian culture. It was abandoned circa 1350 after several floods and a general collapse of the Mississippian world.

Teochtitlan, in Mexico City, Mexico, is associated with the Aztec. It was conquered by the Spanish in 1521.

Tikal / Yax Mutal, in Guatemala, is associated with the Maya. It peaked in the 200 to 900 CE period and was abandoned before the Spanish arrived.

Omahkoyis ("big tree lodge"), in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, is associated with the Blackfoot, another Algonquin-speaking group. It was established by 3,000 BCE or perhaps as early as 12,000 BCE and was assimilated by British Canada in the early 19th century.

Qusqu ("boundary stone" or "navel"), in Cuzco, Peru, is associated with the Killke, Quechua, and Inca. It was conquered by the Spanish in 1532.

Uttewas ("white-slope village"), in Old Massett, British Columbia, Canada, is associated with the Haida. It was established during the last ice age (c. 14,000 to 19,000 YBP, or circa 17,000 to 12,000 BCE) and was partially assimilated by British Canada in the mid-19th century.

Pre-colonial Native American cities/settlements/meeting sites.

Sivan Vahki: just north of Casa Grande, Arizona, Sivan Vahki or Siwañ Waʼa Ki: was a large farming and trade network site of the Sonoran Desert people starting in the early 13th century.

Werowocomoco: With habitation beginning from the 13th century, Werowocomo was a village that later served as the headquarters of the werowance Wahunsenacah, Paramount Chief of the Powhatan confederacy.

Cahokia: Mississippian culture city dating from circa 1050–1350 CE, containing elaborately planned community, woodhenge, mounds, and burials.

Tenochtitlan: built atop a lake, Tenochtitlan was an Aztec altepetl, and was the largest city in the pre-columbian Americas at its peak. It is considered one of the most impressive cities in North America, and is today known as Mexico city.

Tikal: one of the most powerful ancient kingdoms of the Maya, and dates back as far as the 4th century BC, and may have had a population of up to 90,000.

Omahkoyis: Meeting place and trading and cultural hub for the Blackfoot, and later other tribes as well as settlers. The Blackfoot and their ancestors had inhabited the area as early as 12,000 BC, and would later also be known by other names. Colonizing efforts turned the area into a settlement, known today as the city of Edmonton.

Qusqu: also known as “Cuzco”, the city served as the capital for the Inca Empire from the 13th century up into the 16th century upon colonization. However, evidence shows that The Killke people occupied the region from 900 to 1200 CE, prior to the arrival of the Inca, and had constructed a fortress about 1100 CE.

Uttewas: later known as “Old Masset”, was one of the largest Haida villages on Haida Gwaii, and is home to a number of important cultural artifacts, such as numerous totem poles. Today its land is legally designated as Masset Indian Reserve No. 1.

#Sivan Vahki#Coolidge Arizona#Hohokam#1150#1100s#12th century ce#1450#1400s#15th century#1200s#13th century ce#1300s#14th century ce#Werowocomoco#Jamestown Virginia#Powhatan#Algonquin#1270#1609#13th century#14th century#1500s#16th century#1600s#17th century#Cahokia#East St. Louis#Illinois#Missouri#Mississippi River

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

etz hayyim (“tree of life”) synagogue in chania, crete, greece. the building dates to the 14th-15th centuries, and was originally a venetian catholic church. it was acquired by chania's jewish community and converted into a synagogue in the late 17th century. chania's jews were deported due to the holocaust in 1944, after which the building remained abandoned until restoration in the 1990s.

romaniote jews are the oldest jewish community in europe and one of the oldest in the world, thought to have lived in and around present day greece since before 70 ce. they have their own liturgy that is unrelated to the more commonly used european ones (ashkenazic and sephardic).

#greece#architecture#interior#worship#jewish#romaniote#old & new#my posts#for all u Westerners 'rom' = constantinople referring to itself as the roman empire#so rome/italy is like 'west roman' constantinople/greece/anatolia is like 'east roman'#in the west its called 'byzantine' from 'byzantium' (proto-constantinople)#also it insinuates w roman empire was the 'real' roman empire (despite east lasting 1000 years longer)#in most mediterranean & w asian languages greece/greek is 'yunan/yawan/yavan' (from ionians) or 'rum/rom' (from roman)#in actual greek it's 'hellas'/'ellas' (from hellenic)#in georgian it's 'saberdzneti' for some reason but they also have their own names for a bunch of places#'greece' comes from the latin name 'graecia'#in a lot of slavic languages it's some variation of 'greece'. weird considering most were never/hardly under latin influence#if you think this is a lot just wait until u hear about the all the names for armenia#but yeah these guys were also in a lot of the balkans. if you're from the balkans and jewish you MAY have romaniote ancestry#(at least more recent romaniote ancestry than all other european jews)#not a guarantee though especially if you're ashkenazi#theres like. other jewish groups in europe that predated ashkenazi migration#most of them just got absorbed into the ashkenazi population

469 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节), also known as the Mooncake Festival, falls on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. It is called the Mid-autumn Festival because the 15th day is the middle of a month, and the eighth lunar month is in the middle of autumn. In Singapore, mooncakes and lanterns are offered for sale as early as a month before the festival. These days, however, it has become more common to give mooncakes as gifts than to eat them during the festival. The custom of offering sacrifices to the moon has been replaced by celebrating the festival with family and friends. Moon-viewing parties is one way to enjoy the occasion, with family and friends sitting in gardens lit by paper lanterns, sipping tea, nibbling on mooncakes, and if so inspired, composing poetry in venerable Tang Dynasty fashion.

The Full Moon is considered a symbol of reunion, as such the Mid-autumn Festival is also known as the Reunion Festival. Shaped round like the full moon, mooncakes signify reunion. The Mid-autumn Festival is associated with the moon and “moon appreciation” (赏月) parties, particularly because the moon is at its brightest during this time. The festival also coincides with the end of the autumn harvest, marking the end of the Hungry Ghost Festival, which occurs during the seventh lunar month. The day of the Mid-autumn Festival is traditionally thought to be auspicious for weddings, as the moon goddess is believed to extend conjugal bliss to couples.

Among the Chinese, the most popular of all the tales connected with the Mid-autumn Festival is that of Chang-E (嫦娥), also known as the Moon Lady, and her husband Hou Yi (后羿). This myth is said to have originated from storytellers in the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), and even as far back as the time of Emperor Yao (2346 BCE).

youtube

Hidden Messages in Mooncakes played a major role in the liberation of Yuan China (1206–1341 CE) from the Mongols in the 14th century. Despite a prohibition against large gatherings, rebel leader Zhu Yuan Zhang was able to instigate a rebellion by placing secret messages in mooncakes. The rebellion took place during the Mid-autumn Festival, and the celebration of the festival and eating of mooncakes took on a different meaning thereafter.

Information from National Library Board. Bo Jio literally meaning “not invited” in Hokkien.

#Mid-Autumn Festival#中秋节#Mooncake Festival#农历八月十五#Chinese Culture#Chinese Tradition#Celebration#Season Greeting#Mooncake#月饼#Moon Appreciation#赏月#Chang-E#嫦娥#Hou Yi#后羿#Hidden Messages#Video#Youtube#Snack#Dessert#Asian Food#Food#Buffetlicious

98 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is the highest order of knighthood in Britain and the most exclusive with traditionally only 24 knights as full members at any one time, along with the reigning monarch and the Prince of Wales. Created by Edward III of England c. 1348 CE, the chivalric order was one of the first of a growing trend where rulers and noble knights sought to differentiate themselves from the increasing number of knights in the late medieval period. The order's annual gathering at Saint George's Chapel at Windsor Castle, with its magnificent procession of members and retainers in full regalia, maintains the traditions of pomp and pageantry for which the Middle Ages are rightly famous.

Origins

The Order of the Garter was created by the English monarch Edward III (r. 1327-1377 CE) around 1348 CE and dedicated to the Virgin Mary and Saint George. The king was still in a celebratory mood after England's famous victory over a much bigger French army at the Battle of Crécy in August 1346 CE and was eager to further emphasise the nation's martial prowess by creating an elite order of knights. In addition, by the 14th century CE, the number of knights had greatly increased so that the upper ranks of the nobility began to look for some way in which they could differentiate themselves from other knights and create a sort of private members club. These elite brotherhoods were designed to also pull together the greatest fighters and most useful military knowledge and experience so that in times of war the order would prove a useful part of the army's command structure. Finally, such secular chivalric orders were a good way for a sovereign to ensure the loyalty of their best knights who otherwise may have joined an order whose members, instead, swore allegiance to the church (the then-defunct Knights Templar being an example of such an order).

The Order of the Garter was the first of such chivalric orders in England, but there had been several already formed elsewhere, notably the Order of the Sash by King Alfonso XI of Castile and Leon (r. 1313-1350 CE) and the Order of Saint Catherine in France, both founded during the 1330s CE. The pomp and ceremony of the Order of the Garter was something more, though, and it would spawn many other famous orders at home and abroad such as the Order of the Golden Fleece, created by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1419-1467 CE) in 1430 CE.

Just like the legendary Round Table of King Arthur, the order of the Garter was, from the outset, intended to be a very exclusive club indeed. Its first two members were Edward III himself and his son, Edward the Black Prince and Prince of Wales. Alongside this pair were 24 knights, known as Companions of the Order of the Garter, all of whom had fought at the Battle of Crécy. Each member was granted the right to wear a dark blue garter as a symbol of their membership and new rank. A specific coat of arms was created for the order, which includes the flag of Saint George enclosed in a circle made up of a garter. Besides the knights, there were 26 priests and 26 'poor knights' (faith and charity being great chivalric ideals) who were expected to pray for the souls of the more illustrious full members, although they did receive free clothes, food, and lodgings at Windsor castle.

Continue reading...

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

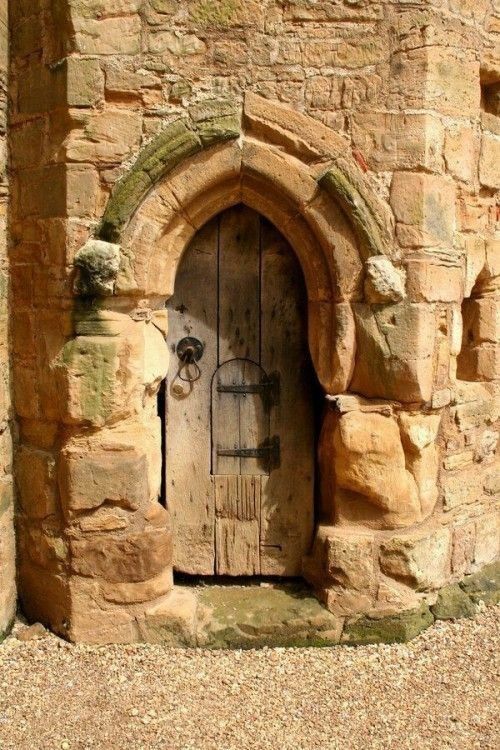

A 14th Century CE, door at Battle Abbey in East Sussex, England....

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sara de Sancto Aegidio (of St. Gilles) was a Jewish woman doctor who lived in Marseille in the 14th century.

The widow of a fellow physician named Avraham, her existence is documented through a contract dated August 28, 1326, between herself and her student, Salvetus de Burgonoro from Salon-de-Provence. According to this contract, Sara agreed to teach Salvetus medicine and to provide him with board, lodging, and clothing for seven months. In return, Salvetus was required to hand over all the fees he earned from treating patients during this period.

Likewise, another Jewish woman surgeon named Chava practiced in 15th-century Manosque. Around this time, four of the seven Jewish women doctors in Frankfurt were noted for their expertise in eye medicine. These women likely learned their skills from other practitioners or family members.

See also: Magistra Hersend, royal doctor during the 13th century.

Here is the link to my Ko-Fi. If you enjoy my content, your support would be much appreciated!

Further reading

Decker Sarah Ifft, Jewish Women in the Medieval World 500–1500 CE

Taitz Emily, Henry Sondra, Tallan Cheryl, The JPS Guide to Jewish Women

#Sara de Sancto Aegidio#sara of st. gilles#history#women in history#women's history#historyedit#14th century#15th century#france#french history#medieval women#middle ages#medieval history

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Persian pottery fragment depicting King Bahram Gur hunting with Azadeh. The glazed fragment was originated in Kashan, and it dates back to the late 13th century and early 14th century CE. The Pergamon Museum, Berlin, GERMANY.

Photo by Babylon Chronicle

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

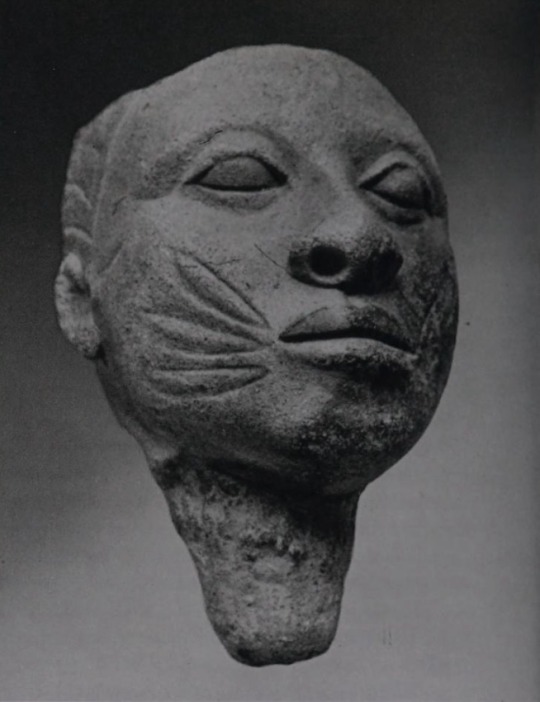

“Head with "cat whisker" marks

Olokun Walode site, lle-Ife, Nigeria, c. early 14th century ce Terracotta; Height: 127 mm

Nigeria National Museums”

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish Ceremonial Wedding Ring. Possibly made in Italy. 13th-14th Century CE.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

#the metropolitan museum of art#the metropolitan#early modern period#early modern history#jewish history#jewish fashion#Jewish#italian history#italy#european history#museum#art#culture

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

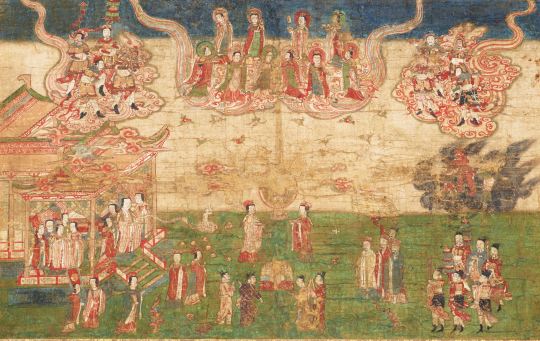

Depiction by an unknown Chinese artist of the birth of Mani (216-274 CE), founder of Manichaeism, a dualistic religion that portrays existence as a struggle between kingdoms of light and darkness. From its origins in present-day Iraq, Manichaeism spread westward into the Roman Empire (where it temporarily won over Augustine of Hippo before his conversion to Catholicism) and eastward into Asia. Though it died out in the West following intense persecution by the Christian Roman emperors, it is thought to have persisted in some parts of China into the 20th century, and perhaps still today.

Colors on silk, 35.6x56.9 cm (=14x22.4 in). 14th century (late Yuan or early Ming Dynasty). Now in the Kyushu National Museum, Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan.

#art#art history#Asian art#China#Chinese art#Imperial China#Mani#Manichaeism#14th century art#Kyushu National Museum#religion#ancient religion#ancient history

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cheraman Juma Mosque is a popular prayer centre in Kodungallur in Thrissur district. According to hagiographical legends, it is claimed that the mosque was built in 629 CE by Malik Bin Dinar.[1]

It is claimed to be the first mosque to be built in India.[2][3] It is claimed to be the oldest mosque in the Indian subcontinent which is still in use.[4][5][6]

The mosque was constructed in Kerala style with hanging lamps, making the historicity of its date claims more convincing.[7][better source needed][8][better source needed][9][better source needed][10][better source needed][11][better source needed][12][better source needed][13][better source needed] Other scholars are more skeptical and dated the structure to the 14th-15th century based on the architectural style.[14]

lol

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The History of Astrology: A Journey Through Time and Thought

Astrology, the study of the positions and movements of celestial bodies and their purported influence on human affairs, has been a fixture in human culture for millennia. Its evolution reflects a complex interplay between science, philosophy, and spirituality, showcasing how societies have sought to understand their place in the cosmos. This essay explores the historical development of astrology, from its ancient origins to its contemporary forms.

Ancient Beginnings: Mesopotamia and Egypt

The roots of astrology can be traced back to ancient Mesopotamia, around the 3rd millennium BCE. The Babylonians, who were among the first to develop systematic astronomical observations, used these observations to create a form of astrology that combined celestial phenomena with predictions about earthly events. This early astrology was primarily concerned with omens and was heavily intertwined with the religious and political life of the time.

By the 2nd millennium BCE, Egyptian astrology had begun to emerge, blending Mesopotamian influences with local beliefs. The Egyptians, known for their advanced knowledge of astronomy and their intricate pantheon of gods, integrated astrological concepts into their religious and daily practices. They used astrology to forecast events and guide decisions, often linking the movements of the stars to the will of their gods.

Hellenistic Synthesis: The Birth of Horoscopic Astrology

The Hellenistic period (circa 3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE) marked a significant transformation in astrology. With the expansion of the Greek empire and the subsequent mingling of Greek, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian cultures, a more sophisticated form of astrology emerged. This period saw the development of horoscopic astrology, which focused on creating individual birth charts based on the exact positions of celestial bodies at the time of a person's birth.

One of the key figures in this development was Claudius Ptolemy, a Greek astronomer and astrologer whose work, the Tetrabiblos, became a foundational text for Western astrology. Ptolemy’s system sought to systematize astrological knowledge and establish it as a coherent discipline. His work remained influential throughout the medieval period and beyond, laying the groundwork for modern astrological practices.

Medieval and Renaissance Astrology: Integration and Innovation

During the medieval period, astrology continued to thrive in both the Islamic world and Europe. Islamic scholars preserved and expanded upon Greek and Roman astrological knowledge, integrating it with their own astronomical observations and philosophical ideas. Figures like Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi and Al-Kindi made significant contributions, blending astrological theory with a more refined understanding of the cosmos.

In Europe, astrology gained prominence as part of the broader scholarly tradition. Medieval scholars, including prominent figures like Thomas Aquinas, debated the role of astrology within a Christian framework. Despite some resistance from the Church, astrology remained a respected academic discipline and was often used in conjunction with medicine, politics, and other fields.

The Renaissance period (14th to 17th centuries) saw a revival of interest in astrology, driven by a renewed fascination with classical texts and an emphasis on the relationship between the macrocosm and the microcosm. Astrologers like Johannes Kepler, who is also known for his contributions to celestial mechanics, attempted to reconcile astrology with emerging scientific principles, though his work ultimately leaned more towards astronomy.

Modern Perspectives: From Science to Personal Insight

The Enlightenment and subsequent scientific revolutions brought a shift in attitudes towards astrology. With the rise of empirical science and skepticism towards unverified claims, astrology began to lose its status as a scientific discipline. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw astrology increasingly marginalized by the scientific community, with many viewing it as a pseudoscience.

However, astrology did not disappear. Instead, it underwent a transformation, adapting to modern sensibilities and becoming a popular cultural phenomenon. The 20th century witnessed the rise of psychological astrology, which emphasized the role of astrology in personal growth and self-understanding. Figures like Carl Jung incorporated astrological concepts into their psychological theories, reflecting a broader interest in integrating astrology with modern ideas about the self and consciousness.

Today, astrology occupies a diverse space within contemporary culture. While it is not recognized as a scientific discipline, it remains a popular and influential practice, with many people finding value in its symbolic and interpretive frameworks. Modern astrologers often focus on personal horoscopes and guidance, drawing on ancient traditions while adapting to contemporary concerns and contexts.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Meaning and Reflection

The history of astrology is a testament to humanity's enduring quest to understand the cosmos and our place within it. From its origins in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt to its modern incarnations, astrology has evolved alongside human thought, reflecting our shifting attitudes towards knowledge, spirituality, and the universe. While its scientific validity remains debated, astrology continues to offer a rich tapestry of symbolism and insight, underscoring the timeless human desire to seek meaning in the stars.

#astrology#metaphysics#mysticism#occultism#astro observations#astro community#astro notes#astrology notes#astro tumblr#chatgpt

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bat-Nosed Figure Pendant

Coclé, 12th–14th century CE

The powerful Prehispanic rulers of present-day Panama and Costa Rica expressed their authority and status by the ostentatious display of gold ornaments in both life and death. Pendants that combine human form with those of various animals selected for specific behavioral characteristics were suspended from the neck by a thong or cord.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

friendship ended with 'kiku was a shy and lonely hermit for most of his life only until the meiji era', 'kiku was reasonably well-travelled regionally and a seasoned mariner who culturally has a deep relationship with the sea and who, centuries ago, learned advanced shipbuilding and navigation from yong-soo (who is also the old korean kingdom of silla and another reason the whole student backstabbing his teacher theme is a recurrent thing for kiku.) isolationist at times when domestic political turmoil constrained things, but also adventurous and ambitious, yearning to see what is further beyond. many facets of the same whole. he's an old mariner, and that's why when alfred forces the end of isolationism at the point of a gun(boat), for kiku it was like picking up a sword that he hasn't used in a while, but which he's very familiar with' is my best friend now:

5th century: Goguryeo–Wa conflicts (Korea and Japan)

6th century: Japanese embassies to Sui China

7th century: Baekje-Tang War (Korea, Japan and China)

9th century: Japanese embassies to Tang China

13th century: Mongol invasions of Japan (self-explanatory)

14th—16th century: Japanese wokou piracy

1565: Battle of Fukuda Bay (Portugal and Japan)

1582 Cagayan battles (Japan, China, Korea (pirates) vs. Spain)

1590s CE: Imjin War (Japanese invasion of Korea with the intention to also conquer China)

1609: Invasion of the Ryukyu Kingdom

1613: Hasekura Mission to Mexico and Europe

#hetalia#hetalia headcanons#hws china#hws japan#hws south korea#more complexity than he is a Shy Hermit please it's ludicrous as someone whose folks got invaded by japan so many times lol#he is not shy he is a right pain in the arse and regional hothead when he wants to be lmao

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Interview: Medieval Christian Art in the Levant

Medievalists retain misconceptions and myths about Oriental Christians. Indeed, the fact that the Middle East is the birthplace of Christianity is an afterthought for many. During the Middle Ages, Christians from different creeds and confessions lived in present-day Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine. Here, they constructed churches, monasteries, nunneries, and seminaries, which retain timeless artistic treasures and cultural riches.

James Blake Wiener speaks to Dr Mat Immerzee to clarify and contextualize the artistic and cultural heritage of medieval Christians who resided in what is now the Levant.

Dr Immerzee is a retired Assistant Professor at Universiteit Leiden and Director of the Paul van Moorsel Centre for Christian Art and Culture in the Middle East at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Saint Bacchus Fresco

James Gordon (CC BY)

JBW: The largest Christian community in what is present-day Lebanon is that of the Maronite Christians – they trace their origins to the 4th-century Syrian hermit, St. Maron (d. 410). The Maronite Church is an Eastern Catholic Syriac Church, using the Antiochian Rite, which has been in communion with Rome since 1182. Nonetheless, Maronites have kept their own unique traditions and practices.

What do you think differentiates medieval Maronite art and architecture from other Christian sects in the Levant? Due to a large degree of contact with traders and crusaders from Western Europe, I would suspect that we see “Western” influence reflected in Maronite edifices, mosaics, frescoes, and so forth.

MI: Especially in the 13th century, the oriental Christian communities enjoyed an impressive cultural flourishing which came to expression in the embellishment of churches with wall paintings, icons, sculpture, and woodwork and the production of illustrated manuscripts, but what remains today differs from on one community or region to another. In Lebanon, several dozens of decorated Maronite and Greek Orthodox churches are encountered in mountain villages and small towns in the vicinity of Jbeil (Byblos), Tripoli, the Qadisha Valley, and by exception in Beirut, but only a few still preserve substantial parts of their medieval decoration programs. Most churches fell into decay after the Christian cultural downfall in the early 14th century when the pressure to convert became stronger. While many church buildings were left in the state they were, others were renovated in the Ottoman period or more recently.

Christian Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, c. 1000

Simeon Netchev (CC BY-NC-ND)

Remarkably Oriental Christian art displays broad uniformity with some regional and denominational differences. Cut off from the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire after the Arab conquest, it also escaped from the Byzantine iconoclastic movement (726-843 CE), which allowed the Middle Eastern Christians to develop their artistic legacy in their own way. An appealing subject is the introduction of warrior saints on horseback such as George and Theodore from about the 8th century. The West and the Byzantine Empire had to wait until the Crusader era to pick up this oriental motif and make it a worldwide success. But the borrowing was mutual. Mounted saints painted in Maronite, Melkite (Greek Orthodox), and Syriac Orthodox churches would increasingly be equipped with a chain coat and rendered with their feet in a forward thrust position, a battle technique developed within Norman military circles. Moreover, the Syrian equestrian saints Sergius and Bacchus were rendered holding a crossed ‘crusader’ banner, an attribute usually associated with Saint George, as if they were Crusader knights. Apart from these examples, there is little evidence of Oriental susceptibility to typically Latin subjects. We find Saint Lawrence of Rome represented in the Greek Orthodox Monastery of Our Lady near Kaftun, but this is exceptional.

Normally, one cannot tell from wall paintings in Lebanon to which community the church in question belonged. They all represented the same subjects and saints whose names are written in Greek and/or Syriac and may have recruited painters from the same artistic circles. Regarding architecture, the last word has not been said on this matter, because the documentation of medieval Lebanese church architecture is still in progress. Nevertheless, the build of some churches undeniably displays Western architectural influences; for example, the Maronite Church of Saint Sabas in Eddé al-Batrun is even plainly Romanesque in style.

JBW: Following my last question, is it then correct to assume that the Crusader lands – Edessa, Antioch, Tripoli, and Jerusalem – were quite receptive to Eastern Christian styles?

MI: That is difficult to tell because there is next to nothing left in the former County of Edessa and the Principality of Antioch. We do have some decorated churches in the former Kingdom of Jerusalem (Abu Gosh, Bethlehem), and here we see a strong focus on Byzantine craftsmanship and Latin usage. Apart from the preserved church embellishment in the Lebanese mountains, there are some fascinating, stylistically and thematically comparable instances across the border with Syria.

Saint Peter in Sinai

Wikipedia (Public Domain)

Although situated within Muslim territory, the Qalamun District between Damascus and Homs stands out for its well-established Greek Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox populations; and from the 18th century onwards, also Greek Catholics and Syrian Catholics. Interestingly, stylistic characteristics confirm that indigenous Syrian painters were also involved in the decoration inside Crusader fortresses such as Crac des Chevaliers and Margat Castle in Syria. It was obviously easier to contract local manpower than to find specialists in Europe.

JBW: The Byzantine Empire exuded tremendous political, cultural, and religious sway across the Levant throughout the Middle Ages; a sizable chunk of the Christian population in both Syria and Lebanon still adheres to the rituals of the Greek Orthodox Church even today.

MI: Leaving aside the cultural foundations laid before the Arab conquest, the contemporary Byzantine influences can hardly be overlooked. In the 12th and 13th centuries, itinerating Byzantine-trained painters worked on behalf of any well-paying client within Frankish and Muslim territory, from Cairo to Tabriz, irrespective of their denominational background. This partly explains the introduction of some ‘fashionable’ Byzantine subjects and the Byzantine brushwork of several mural paintings and icons. Made in the 1160s, the Byzantine-style mosaics in the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem are believed to be the result of Latin-Byzantine cooperation at the highest levels; they exhale the propagandistic message of Christian unity. In 1204, however, the Crusaders would conquer Constantinople and substantial parts of the Byzantine Empire. The Venetians brought the bounty to Venice, and, surprisingly, also to Alexandria with the consent of the sultan in Cairo, intending to sell the objects in the Middle East. So much for Christian unity…

The Eastern Greek Orthodox Church has its roots in the Chalcedonian dispute about the human and divine nature of Christ in 451, which resulted in the dogmatic breakdown of the Byzantine Church into pro- and anti-Chalcedonian factions. Like the Maronites, the Melkites (‘royalists’) remained faithful to the former, official Byzantine standpoint, except for their oriental patriarchs in Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem were officially allowed autonomy without direct interference from Constantinople. On the other hand, the Syriac Orthodox became dogmatically affiliated with the identically ‘Miaphysite’ Coptic, Ethiopian, and Armenian Churches. To complicate matters even more, part of the Greek Orthodox and Syriac Orthodox communities joined the Church of Rome in the 18th century. This resulted in the establishment of the Greek Catholic and Syriac Catholic Churches.

The Church of Nativity, Bethlehem

Konrad von Grünenberg (Public Domain)

JBW: Could you tell us a little bit more with regard to the Syriac Orthodox Church? If I’m not mistaken, there was a flourishing of the building of churches and monasteries by Syriac Orthodox communities once they fell under Muslim rule around 640.

MI: As a Miaphysite community, the Syriac Orthodox enjoyed the same protected status as other non-Muslim communities under Muslim rule. This allowed them to establish an independent Church hierarchy headed by their patriarch who nominally resided in Antioch, which covered large areas in Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria. Some of their oldest churches, with architectural sculpture and occasionally a mosaic, are situated in the Tur Abdin region in Southeast Turkey. Remarkably, around the year 800, a group of monks from the city of Takrit (present-day Tikrit in Iraq) migrated to Egypt to establish a Syriac ‘colony’ within the Coptic monastic community. Their ‘Monastery of the Syrians’ (Deir al-Surian) still exists and is one of Middle Eastern Christianity’s key monuments for its architecture, wall paintings, icons, wood- and plasterwork ranging in date from the 7th to the 13th centuries. The monastery also houses an extensive manuscript collection. Another decorated monastery is the Monastery of St Moses (Deir Mar Musa; presently Syriac Catholic) near Nebk to the north of Damascus, where paintings from the 11th and 13th-centuries can still be seen. The Monastery of St Behnam (Deir Mar Behnam; presently Syriac Catholic) near Mosul is reputed for its 13th-century architectural sculpture and unique stucco relief, but unfortunately, a lot has been destroyed by ISIS warriors.

The Syriac Orthodox presence in Lebanon remained limited to a church dedicated to Saint Behnam in Tripoli, and the temporary use of a Maronite church dedicated to St Theodore at the village of Bahdeidat by refugees from the East who were on the run from the Mongols during the 1250s. This church still displays its complete decoration program from this period. It is impossible to tell which community arranged the refurbishment, but the addition of a donor figure in Western dress testifies to support from a (probably) local Frankish lord. Finally, the Syriac Orthodox also excelled in manuscript illumination, examples of which can be found in Western collections and the patriarchal library near Damascus.

JBW: As the Lebanese and Syrian Greek Orthodox Churches had fewer dealings with Western Europeans than the Maronite Church, does medieval Christian Orthodox art in Lebanon and Syria reflect and maintain the designs and styles of medieval Byzantium? If so, in what ways, and where do we see deviation or innovation?

MI: As I said before, Byzantine-trained artists have been surprisingly active in the Frankish states and beyond, especially during the 13th century. I prefer to label them as “Byzantine-trained” instead of “Byzantine,” because it is not always clear where they came from. To mention an example, painters from Cyprus still worked in the Byzantine artistic tradition but no longer fell under the authority of the emperor after the Crusader conquest of the island in 1291. Culturally they were still fully Byzantine, but, speaking in modern terms, they would have had the Frankish-Cypriot nationality. The little we can say from the preserved paintings is that some Cypriot artists traveled to the Levant in the aftermath of the power change in search of new clientele. It is unknown if they stayed or returned after the accomplishment of their tasks, but around the mid-13th century we see the birth of a ‘Syrian-Cypriot’ style which combines Byzantine painting techniques with typically Syrian formal features and designs; for example, in the afore-mentioned Monastery at Kaftun in Lebanon. Typically, instances of this blended art are not only encountered in Lebanon and Syria but also in Cyprus.

The Virgin and Child Mosaic, Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia Research Team (CC BY-NC-SA)

Focusing on the shared elements in Oriental Christian and Byzantine art, the example of apse decorations illustrates the resemblances and often also subtle differences. From the Early Christian period, the common composition in the apse behind the altar consisted of the mystical appearance of Christ (Christ in Glory) between the Four Living Creatures in the conch and the Virgin between saints, such as the apostles and Church fathers, in the lower zone. However, an early variant encountered in Egypt renders the biblical Vision of Ezekiel: here, Christ in Glory is placed on the fiery chariot the prophet saw. Recent research has brought to light that this variant was also applied in Syriac Orthodox churches in Turkey and Iraq as late as the 13th century. Medieval oriental conch paintings often combine Christ in Glory with the Deesis, that is, the Virgin and St John the Baptist pleading in favour of mankind. Whereas the Byzantines kept these subjects separated, the ‘Deesis-Vision’ is encountered from Egypt to Armenia and Georgia in churches of all denominations

JBW: One cannot discuss medieval Christian art in the Near East without making some mention of Armenians and Georgians. The first recorded Armenian pilgrimage occurred in the early 4th century, and Armenian Cilicia (1080-1375) flourished at the time of the Crusades. During the reign of Queen Tamar (r. 1184-1213), Georgia assumed the traditional role of the Byzantine crown as a protector of the Christians of the Middle East. Armenians and Georgians intermarried not only with one another but also with Byzantines and Crusaders.

Where is the medieval Armenian and Georgian presence the strongest in the Levant? Is it discernible?

Tomb of Saint Hripsime in Armenia

James Blake Wiener (CC BY-NC-SA)

MI: Medieval Armenian and Georgian art can be found in their homelands, but there are also surviving works testifying to their presence in the Levant and Egypt. Starting with the Armenians, they have always lived in groups dispersed throughout the Middle East, whereas in Jerusalem they have their own quarter. A 13th-century wooden door with typically Armenian ornamentation and inscriptions in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem testify to the interest Armenians took in the Holy Land. Further to the south, a 12th-century mural painting with Armenian inscriptions in the White Monastery near Sohag reminds us of the strong Armenian presence in Egypt under Fatimid rule during the 11th to 12th centuries. They had arrived in the wake of the rise of power of the Muslim Armenian warlord and later Vizir Badr al-Jamali, who seized all power in the Fatimid realm during the 1070s. He not only brought his own army consisting of Christian and Muslim Armenians but also made Egypt a safe home for Armenians from more troubled areas.

The Christian Armenians had their own monastery and used a number of churches in Egypt. However, these were appropriated by the Copts at the downfall of Fatimid power and the subsequent expulsion of all Armenians during the 1160s. The Armenian catholicos or head of Egypt is known to have left for Jerusalem taking with him all the church treasures.

At the White Monastery, a mural was made by an artist named Theodore originating from a village in Southeastern Turkey on behalf of Armenian miners who were apparently allowed to use the monastery’s church. It is hard to believe that Theodore came all the way to accomplish just one task in this remote place. There can be no doubt that he decorated more Armenian churches during his stay in Egypt, but the Copts thoroughly wiped out all remaining traces of their previous owners.

The Georgian presence was limited to Jerusalem, where they owned the Monastery of the Holy Cross until it was taken over by the Greek Orthodox in the 17th century. In the monastery’s church, a series of 14th-century paintings with Georgian inscriptions are a reminder of this period. In addition, an icon representing St George and scenes of his life painted during the early 13th century, and kept in the Monastery of Saint Catherine in the Sinai, was a gift from a Georgian monk, who is himself depicted prostrating at the saint’s feet.

St. Catherine's Monastery, Sinai

Marc!D (CC BY-NC-ND)

JBW: Because we touched upon the incorporation of outside artistic influences coming from Western Europe and Byzantium to the Levant, I wondered if you might offer a final comment or two on those architectural or artistic influences coming from the Arab World or even the wider Islamic world.

To what extent did Levantine Christians – who often lived near their Muslim neighbors – adopt or assimilate Islamic styles of art and architecture?

MI: The earliest examples of Islamic art from the Umayyad era display strong influences of Late Antiquity, which in turn had also been the source of inspiration to early Christian art. Over the course of time, these artistic relatives would gradually grow apart to meet again on specific occasions. The earliest example of Islamic-inspired Christian art is the purely ornamental stucco reliefs in the Monastery of the Syrians in Egypt. Constructed during the early 10th century by the Abbot Moses of Nisibis. Its plastered altar room exudes the same atmosphere as houses in the 9th-century Abbasid capital of Samarra and the similarly decorated Mosque of Ibn Tulun (an Abbasid prince who came to Egypt as its governor) in Cairo.

The Mosque of Ibn Tulun, Cairo Egypt

Berthold Werner (CC BY)

The decoration of Fatimid-era sanctuary screens in Coptic churches and woodwork from Egyptian Islamic, Jewish, and secular contexts are fully interchangeable; likewise, 13th-century architectural sculpture, manuscript illustrations, and metalwork from the Mosul area display the same shared stylistic and iconographic artistic language. Broadly speaking, we are obviously dealing with craftsmen working on behalf of different parties at the local level regardless of their religious backgrounds. Occasionally, one comes across ‘Islamic’ ornaments in wall paintings, but the overall impression is that Christian painting was subject to blatant conservatism when compared to more fashionable, ‘neutral’ items of interior decoration. The only Arabic inscriptions found in mural paintings concern texts commemorating building or refurbishment activities, or graffiti left by visitors. There obviously was a difference in status between the vernacular spoken language and the Church’s Greek and Syriac.

JBW: Dr. Mat Immerzeel, thanks so much for your time and consideration.

MI: You are welcome; it is my pleasure to contribute to your magazine.

Mat Immerzeel has been active in the Middle East since 1989, first in Egypt, then in Syria and Lebanon, and recently in Cyprus. His main field of study is the material culture of Oriental Christian communities from the 3rd century to the present. In particular, he studies wall paintings, icons, stone and plaster sculpture, woodwork, and manuscript illustrations. He has participated in research projects focusing on the formation of religious communal identity, the training of local collection curators, and restoration and documentation campaigns. He is the Director of the Paul van Moorsel Centre for Christian Art and Culture in the Middle East and editor-in-chief of the journal Eastern Christian Art (ECA) published by Peeters Publishers in Leuven, the Netherlands.

Continue reading...

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do the Mayan years work on the calendar?

I appreciate your comics showing it in the CE years as well but I'm curious how they work

I'm afraid I know close to nothing about the particularities of Maya cultures, let alone their calendar. As for the rest of Mesoamerica, although with variations from region to region, they had two calendars: A sacred-ritual one that lasted 260 days, and a solar one with 365 days, which works just like ours. These two calendars matched every 52 years, which was considered a very special happening and some people dub that 52-year period as the "indigenous century." There's intense debate about the calendar, and whether it adjusted to take into account leap years or not, and it is a VERY complex topic to which many researchers dedicate their lives, so I can't claim to know the exact answers. Maybe your question was related to the naming convention though. The sacred calendar uses a system of 13 numbers + 20 day signs, with a total of 260 possible combinations (hence its duration). So for example, you start the year with day 1-Crocodile, then 2-Wind, 3-House, and so on. After number 13, the count goes back to 1 but with the 14th day sign: 1-Jaguar. From these 20 day signs, 4 were used for the years: House, Rabbit, Reed, and Flint, and also used 13 numbers. So you have a succession of years like 1-House, 2-Rabbit, 3-Reed, 4-Flint, 5-House [...] 13-House, 1-Rabbit, and so on. This count will only reset after 52 years when the cycle restarts.

Here's the 20 day signs (these are those used in Mixtec and Nahua calendars, but other groups like the Maya and Zapotec had different signs, although the calendars were all synchronized):

31 notes

·

View notes