#120 A.D

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ROMAN MARKET GATE OF MILETO - TURKEY

PUERTA ROMANA DEL MERCADO DE MILETO - TURQUÍA

PORTA DEL MERCATO ROMANO DI MILETO - TURCHIA

(English / Español / Italiano)

In ancient times it was located near the mouth of the Meander River, 180 km from the city of Pergamon (Turkey). Miletus was a city of merchants and therefore its market was very important and was located in a square in the center of the city. The Roman style gate was built in 120 A.D. when the Roman Emperor Hadrian ruled and corresponded to the southern entrance of the Market of Miletus. Later, in the 6th century, Emperor Justinian ordered the construction of a city wall around the city of Miletus and the Market Gate was part of the wall. It is one of the best known examples of Roman architectural facades.

Today the Market Gate of Miletus is in the Pergamon Museum, as it appears in the image, in the room dedicated to Roman architecture and is the best preserved piece in the entire museum.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Antiguamente se encontraba cerca de la desembocadura del río Meandro a 180 km de la ciudad de Pérgamo (Turquía). Mileto era una ciudad de comerciantes y por eso su mercado era muy importante y se encontraba en una plaza del centro de la ciudad. La Puerta de estilo romano fue construida en el año 120 d.C. cuando gobernaba el emperador romano Adriano y correspondía a la entrada sur del Mercado de Mileto. Más tarde, en el s.VI, el emperador Justiniano ordenó construir una muralla alrededor de la ciudad de Mileto y la Puerta del Mercado formó parte de la muralla. Es uno de los ejemplos más conocidos de fachadas arquitectónicas romanas.

Hoy en día la Puerta del Mercado de Mileto se encuentra en el Museo de Pérgamo, tal como aparece en la imagen, en la sala dedicada a la arquitectura romana y es la pieza mejor conservada de todo el museo.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nell'antichità si trovava vicino alla foce del fiume Meandro, a 180 km dalla città di Pergamo (Turchia). Mileto era una città di mercanti e quindi il suo mercato era molto importante e si trovava in una piazza nel centro della città. La porta in stile romano fu costruita nel 120 d.C. durante il regno dell'imperatore romano Adriano e corrispondeva all'ingresso meridionale del mercato di Mileto. Più tardi, nel VI secolo, l'imperatore Giustiniano ordinò la costruzione di una cinta muraria intorno alla città di Mileto, di cui la Porta del Mercato faceva parte. È uno degli esempi più noti di facciata architettonica romana.

Oggi la Porta del Mercato di Mileto si trova nel Museo di Pergamo, come mostra la foto, nella sala dedicata all'architettura romana, ed è il pezzo meglio conservato dell'intero museo.

#ancient rome#roma antigua#antica roma#120 A.D#120d.C.#s. VI#6th century#mileto#pergamo#miletus#pergamon#Emperor Hadrian#imperatore Adriano

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ROMAN MONUMENTAL MARBLE PORTRAIT HEAD OF POMPEIA PLOTINA TRAJANIC PERIOD, C. 110 - 120 A.D.

Pompeia Plotina was born around 70 A.D. into a prominent Roman family. Little is known about her early life, but she gained prominence when she married the future Emperor Trajan, likely around 100 A.D. As Trajan rose through the ranks of the Roman military and eventually ascended to the imperial throne in 98 A.D., Plotina assumed the role of empress consort.

During Trajan's reign, Plotina was known for her philanthropy and patronage of public works, funding various civic projects and charitable initiatives throughout the empire. Plotina's adherence to Stoic principles, a philosophical school popular among the Roman elite, was notable. She is described as having embraced a life of simplicity and modesty, eschewing the trappings of power and luxury often associated with imperial life.

Following Trajan's death in 117 A.D., Plotina continued to be revered but lived out the remainder of her life in relative obscurity, passing away sometime in the early 120’s A.D.

#ROMAN MONUMENTAL MARBLE PORTRAIT HEAD OF POMPEIA PLOTINA#TRAJANIC PERIOD#C. 110 - 120 A.D.#Pompeia Plotina#Emperor Trajan#marble#marble statue#marble sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman emperor#roman art#ancient art#art history

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

A ROMAN MARBLE HEAD OF HERMES CIRCA 120-140 A.D. found at the Pantanello at Hadrian's Villa in November 1769. Christie's July 2022. http://hadrian6.tumblr.com

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The more corrupt the state the more it legislates"

Tacitus (A.D. 56-120) Roman historian and statesman.

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

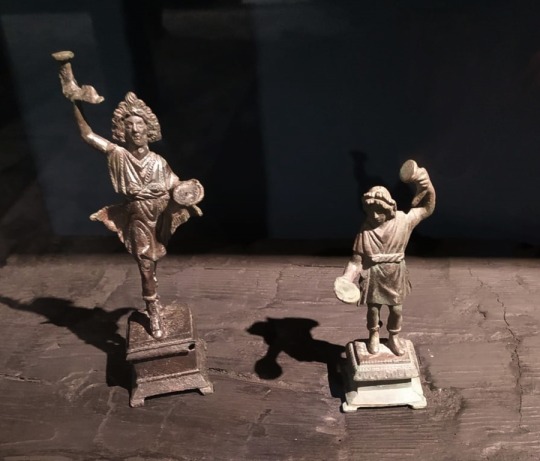

Mummy Mask c. A.D. 120-170

Roman - Egypt

Stucco/gesso with paint, gold leaf, and glass inlays / The face was pressed from a mold, while the curling hair, ears, and beard were added to increase its portrait like quality

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the exposition "Materia" in Reggia di Portici, Italy. The itinerary is distributed into some rooms on the noble floor of the Royal Palace, according to an undoubtedly evocative disposition that will allow the visitor to not only appreciate the miracolous conservation of the wood that escaped the catastrophe that hit the Vesuvius region in 79 A.D., but also to immerse oneself in the life of the ancients and to understand how vital wood was for every activity, as well as being a precious material to the point that trees and woods often took on aspects of sacredness and symbolic values, through over 120 objects all hailing from Herculaneum and presented to the public in monographic form.

#herculaneum#italy#napoli#italia#ercolano#vesuvio#pompeii#naples#loves#scavidiercolano#archeology#ercolanoscavi#vesuvius#ig#pompei#campania#igersitalia#igersnapoli#vesuviocoast#gf#igerscampania#browsingitaly#pocket#topitalyofficial#archiologia#united#italiale#italyiscalling#flipitaly#life

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

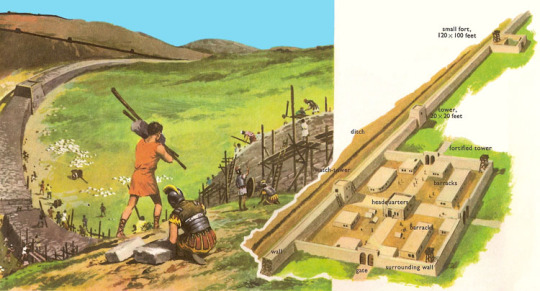

January 24th, 76AD, is the probable date of birth of Publius Aelius Hadrianus, who built Hadrian’s Wall.

Right let’s start with the myth, a lot of people believe it marks the border between Scotland and England, and never has. In fact, the wall predates both kingdoms, while substantial sections of modern-day Northumberland and Cumbria – both of which are located south of the border – are bisected by it.

This post is a lot longer than I would normally do, Hadrian himself ruled for over 30 years , and the Roman Empire were in Britain for over 350 years. I've taken this post from the Smithsonian web site as I'm tied up trying to do other things this morning

Stretching 80 miles from the Irish Sea in the west to the North Sea in the east, Hadrian’s Wall in northern England is one of the United Kingdom’s most famous structures. But the fortification was designed to protect the Roman province of Britannia from a threat few people remember today—the Picts, Britannia’s “barbarian” neighbours from Caledonia, now known as Scotland.

By the end of the first century, the Romans had successfully brought most of modern England into the imperial fold. The Empire still faced challenges in the north, though, and one provincial governor, Agricola, had already made some military headway in that area. According to his son-in-law and primary chronicler, Tacitus, the highlight of his northern campaign was a victory in 83 or 84 A.D. at the Battle of Mons Graupius, which probably took place in southern Scotland. Agricola established several northern forts, where he posted garrisons to secure the lands he’d conquered. But this attempt to subdue the northerners eventually failed, and Emperor Domitian recalled him a few years later.

It wasn’t until the 120s that northern England got another taste of Rome’s iron-fisted rule. Emperor Hadrian “devoted his attention to maintaining peace throughout the world,” according to the Life of Hadrian in the Historia Augusta. Hadrian reformed his armies and earned their respect by living like an ordinary soldier and walking 20 miles a day in full military kit. Backed by the military he had reformed, he quelled armed resistance from rebellious tribes all over Europe.

But though Hadrian had the love of his own troops, he had political enemies—and was afraid of being assassinated in Rome. Driven from home by his fear, he visited nearly every province in his empire in person. The hands-on emperor settled disputes, spread Roman goodwill, and put a face to the imperial name. His destinations included northern Britain, where he decided to build a wall and a permanent militarized zone between “enemy” and Roman territory.

Primary sources on Hadrian’s Wall are widespread. They include everything from preserved letters to Roman historians to inscriptions on the wall itself. Historians have also used archaeological evidence like discarded pots and clothing to date the construction of different portions of the wall and reconstruct what daily life must have been like. But the documents that survive focus more on the Romans than the foes the wall was designed to conquer.

Before this period, the Romans had already fought enemies in northern England and southern Scotland for several decades, Rob Collins, author of Hadrian's Wall and the End of Empire, says via email. One problem? They didn’t have enough men to maintain permanent control over the area. Hadrian’s Wall served as a line of defense, helping a small number of Roman soldiers shore up their forces against foes with much larger numbers.

Hadrian viewed the inhabitants of southern Scotland—the “Picti,” or Picts—as a menace. Meaning “the painted ones” in Latin, the moniker referred to the group’s culturally significant body tattoos. The Romans used the name to refer collectively to a confederation of diverse tribes, says Hudson.

To Hadrian and his men, the Picts were legitimate threats. They frequently raided Roman territories, engaging in what Collins calls “guerilla warfare” that included stealing cattle and capturing slaves. Starting in the fourth century, constant raids began to take their toll on one of Rome’s westernmost provinces.

Hadrian’s Wall wasn’t just built to keep the Picts out. It likely served another important function—generating revenue for the empire. Historians think it established a customs barrier where Romans could tax anyone who entered. Similar barriers were discovered at other Roman frontier walls, like that at Porolissum in Dacia.

The wall may also have helped control the flow of people between north and south, making it easier for a few Romans to fight off a lot of Picts. “A handful of men could hold off a much larger force by using Hadrian’s Wall as a shield,” Benjamin Hudson, a professor of history at Pennsylvania State University and author of The Picts, says via email. “Delaying an attack for even a day or two would enable other troops to come to that area.” Because the Wall had limited checkpoints and gates, Collins notes, it would be difficult for mounted raiders to get too close. And because would-be invaders couldn’t take their horses over the Wall with them, a successful getaway would be that much harder.

The Romans had already controlled the area around their new wall for a generation, so its construction didn’t precipitate much cultural change. However, they would have had to confiscate massive tracts of land.

Most building materials, like stone and turf, were probably obtained locally. Special materials, like lead, were likely privately purchased, but paid for by the provincial governor. And no one had to worry about hiring extra men—either they would be Roman soldiers, who received regular wages, or conscripted, unpaid local men.

“Building the Wall would not have been ‘cheap,’ but the Romans probably did it as inexpensively as could be expected,” says Hudson. “Most of the funds would have come from tax revenues in Britain, although the indirect costs (such as the salaries for the garrisons) would have been part of operating expenses,” he adds.

There is no archaeological or written record of any local resistance to the wall’s construction. Since written Roman records focus on large-scale conflicts, rather than localized kerfuffles, they may have overlooked local hostility toward the wall. “Over the decades and centuries, hostility may still have been present, but it was probably not quite as local to the Wall itself,” says Collins. And future generations couldn’t even remember a time before its existence.

But for centuries, the Picts continued to raid. Shortly after the wall was built, they successfully raided the area around it, and as the rebellion wore on, Hadrian’s successors headed west to fight. In the 180s, the Picts even overtook the wall briefly. Throughout the centuries, Britain and other provinces rebelled against the Romans several times and occasionally seceded, the troops choosing different emperors before being brought back under the imperial thumb again.

Locals gained materially, thanks to military intervention and increased trade, but native Britons would have lost land and men. But it’s hard to tell just how hard they were hit by these skirmishes due to scattered, untranslatable Pict records.

The Picts persisted. In the late third century, they invaded Roman lands beyond York, but Emperor Constantine Chlorus eventually quelled the rebellion. In 367-8, the Scotti—the Picts’ Irish allies—formed an alliance with the Picts, the Saxons, the Franks, and the Attacotti. In “The Barbarian Conspiracy,” they pillaged Roman outposts and murdered two high-ranking Roman military officials. Tensions continued to simmer and occasionally erupt over the next several decades.

Only in the fifth century did Roman influence in Britain gradually dwindle. Rome’s already tenuous control on northern England slipped due to turmoil within the politically fragmented empire and threats from other foes like the Visigoths and Vandals. Between 409 and 411 A.D., Britain officially left the empire.

The Romans may be long gone, but Hadrian’s Wall remains. Like modern walls, its most important effect might not have been tangible. As Costica Bradatan wrote in a 2011 New York Times op-ed about the proposed border wall between the U.S. and Mexico, walls “are built not for security, but for a sense of security.”

Hadrian’s Wall was ostensibly built to defend Romans. But its true purpose was to assuage the fears of those it supposedly guarded, England’s Roman conquerors and the Britons they subdued. Even if the Picts had never invaded, the wall would have been a symbol of Roman might—and the fact that they did only feeds into the legend of a barrier that’s long since become obsolete.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marble head of Zeus Ammon ca. A.D. 120–160 x

Zeus Ammon’s sanctuary at the Oasis of Siwa in the Libyan desert was already famous when Alexander the Great made his pilgrimage there in 331 B.C. Alexander’s visit to Siwa was a pivotal moment in the young king’s extraordinary life. The details are shrouded in mystery, but legend has it that the Oracle proclaimed him son of Zeus Ammon and answered Alexander’s questions favorably, “to his heart’s desire.” This powerful portrait of the god combines a classical Greek image of the bearded Zeus with the ram’s horns of the Egyptian Ammon, an attribute with which Alexander himself was sometimes represented. It may well reflect a sculpture created in Egypt in the years after Alexander’s historic visit to Siwa.

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xiwang Mu

I made some notes for Xiwang Mu a while ago cause I was super interested in her, I forgot I made this but i'll post it anyways even if its not finished: with both yang and yin, sun and moon, life and death, reveals the goddess's control over the universe. Her link to both yin and yang also suggests androgyny, completeness, and independence. The Queen Mother's usual anthropomorphic attendants are minor deities known as blue lads and jade girls, or followers seeking immortality. In the clay brick from Szechwan, two seated or kneeling female figures, perhaps goddesses, appear in the lower right corner, and two male figures, a deeply bowing attendant holding a jade tablet and a standing guard holding a halberd, fill the lower left corner. The Szechwan tile shows the goddess ruling alone above a hierarchy of spirits. In other contexts, such as the reliefs at the Wu Liang offering shrines and at I nan, she is accompanied by her divine consort, Tung Wang Kung (the King and Sire of the East), who is also called Tung Wang Fu (King Father of the East). She is yin to his yang; the pair embodies the divine marriage that creates the world and keeps it in balance.

Han poetry. Han poems agree with other sources in depicting the Queen Mother as a goddess of longevity living on a magic mountain. Ssu-ma Hsiang-:iu's (179-I I7 B.C.) Tajen fu (Rhapsody on the great man), written between 130 and 120 B.C., portrays her as an old hag. (The fu was a literary form special to the Han that mixed elements of prose and poetry and is often translated as "rhapsody" or "prose-poem.") A part from his humorous tone and clear delineation of age, Ssu-ma's description matches that found in the Classic of Mountains and Seas. The goddess wears a sheng headdress in her white hair and dwells in a remote mountain cave, where a threelegged crow brings her food. The poet comments: "If one were to live without dying, even for a myriad generations, what joy would one have?" (SC, 1 1 7.3060). Through satire and rhetoric, Ssu-ma Hsiang-ju criticizes the cult of immortality and warns the emperor, the "great man" of the title, against wasting his energy in vain pursuit of the worthless gifts offered by this old witch. Yang Hsiung's (53 B.C. -A.D. I S) Kan ch'uan fu (Rhapsody on the Sweet Springs) commemorates an imperial sacrifice to the supreme heavenly deity known as T'ai I or Grand Unity. The long poem takes its title from the Sweet Springs Palace to the east ofCh'ang an, where the ritual was held. Yang Hsiung glorifies Emperor Ch'eng (r. 32-7 B.C.), whose sacrificial procession and ceremonial performance he compares to the shamanistic journeys of the "Elegies of Ch'u." He praises Emperor Ch'eng's palace, likening its building$ and grounds to the goddess's estate on Mount K'un-Iun. Amid purple and turquoise palaces stand gardens planted with jade trees. There stands the Queen Mother of the West, attended by jade maidens and river goddesses. The narrator visualizes her during his ascent to transcendence. "Thinking of the Queen Mother of the West, in a state of joy he makes offerings to obtain longevity" ( WH,

Ia-I4b). Yang emphasizes the adept's flight to immortality with the aid of the goddess. Han dynasty literati venerated the Queen Mother of the West as a major deity who dwelt in heaven, dominated other spirits, controlled access to immortality, and promised ecstatic flight through space. 30

Han works in the Taoist canon. The history of the Taoist religion begins in the second century with the risc of two schools: the Celestial Masters or Five Pecks of Rice school in Szechwan and the Great Peace school around the capital city ofLo yang. They have left few surviving texts and fewer references to the Queen Mother. In fact, no contemporary record of either popular or elite cults to the Queen Mother during the Han dynasty survives in the Taoist canon. The earliest reference to her found in the patrology may be a line in the T'ai-p'ing ching (Classic of grand peace), a text originating in the Celestial Masters schoo!. One line in a section of the classic entitled "Declarations of the Celestial Masters" reads: "Let a person have longevity like that of the Queen Mother of the West," a phrase almost identical to Han mirror inscriptions.31 The Celestial Masters school connects her with long life but shows the goddess no special reverence. Han texts in the canon neglect a cult other sources show to be widespread and continuous, centered on a goddess who was to become one of the highest deities. This may result from attempts on the part of early Taoist leaders to reform the native religions of China. Such tendencies may be seen in efforts by the Celestial Masters to eliminate ancestor worship, blood sacrifice, and monetary payments to the clergy. The Queen Mother's later readmission to the divine hierarchy of the official Taoist church would then represent one of the many victories of the native religion. But the goddess herself changes under the impact of the Taoist religion, as we shall see. . Shang Ch 'ing Taoism, Paradise, Local Cults: The Six Dynasties Shang ch'ing Taoism. The most important development concerning worship of the Queen Mother of the West during the Six Dynasties period was her incorporation into the religious system of Shang ch'ing Taoism. The school takes its name from the highest of three heavens where its gods dwell: the Realm of Supreme Clarity. This new lineage absorbed many archaic goddesses worshiped in earlier eras, such as local deities of the rivers and lakes. Alone among them the Queen Mother remained powerful and active rather than subservient. But her nature altered to suit new needs. Shang ch'ing Taoism originated with revelations from the highest

Humans also have her. She resides in the center of a person's right eye, where her surname is Grand Yin, her name Mysterious Radiance, and her cognomen Supine Jade. A person must obtain the King Father [described in the previous entry as the primal pneuma of blue yang, the precedent one of the myriad divinities, who resides at the magic island of P'eng-lai in the Eastern Sea] and the Queen Mother and guard them in his two eyes. Only then will he be able to practice pacing the void, observing and looking up, and with acute hearing and eyesight distinguish and recognize good and evil. Then he can cause to flow down the various deities, just as a mother thinks of her child, and as a child also thinks of its mother. The germinal essence and pneuma will obtain each other, and for a myriad generations he will prolong his stay.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non-Christian sources confirm the validity of New Testament

The Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus (A.D. 37-100), is the first non-Christian author to mention Jesus. In the Antiquities, Josephus writes:

There was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man, for he was a doer of wonderful works—a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews, and many of the Gentiles. He was Christ; and when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him, for he appeared to them alive again the third day, as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him; and the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day (Antiquities 18:3:3).

Tacitus (A.D. 56-120), the Roman historian confirms that the crucifixion of Jesus actually took place. Writing in his Annals, he records:

Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind.

Pliny the Younger (A.D. 62-113), Roman governor in Asia Minor, established that early Christians worshiped Jesus as a god:

They (Christians) were in the habit of meeting on a certain fixed day before it was light, when they sang in alternate verses a hymn to Christ, as to a god, and bound themselves by a solemn oath, not to any wicked deeds, but never to commit any fraud, theft or adultery, never to falsify their word, nor deny a trust when they should be called upon to deliver it up; after which it was their custom to separate, and then reassemble to partake of food, but of an ordinary and innocent kind (Epistles 10.96).

Suetonius (120 AD) was a Roman historian and court official. When recounting the history of the emperor Claudius some years before him, he said,

“Because the Jews at Rome caused constant disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus [Christ], he [Claudius] expelled them from the city [Rome]” (Life of Claudius, 25:4).

Lucian, born (c. AD 125 – 180), the pagan author Samosata, while ridiculing Christians, accepted that Jesus actually existed:

The Christians, you know, worship a man to this day—the distinguished personage who introduced their novel rites, and was crucified on that account. … You see, these misguided creatures start with the general conviction that they are immortal for all time, which explains their contempt of death and voluntary self-devotion which are so common among them; and then it was impressed on them by their original lawgiver that they are all brothers, from the moment that they are converted, and deny the gods of Greece, and worship the crucified sage, and live after his laws. All this they take quite on faith, with the result that they despise all worldly goods alike, regarding them merely as common property. (Lucian, The Passing of Peregrinus)

Celsus (2nd century), the Greek philosopher, while arguing against Christianity, also accepted that Jesus existed:

O light and truth! He distinctly declares, with his own voice, as ye yourselves have recorded, that there will come to you even others, employing miracles of a similar kind, who are wicked men, and sorcerers; and Satan. So that Jesus himself does not deny that these works at least are not at all divine, but are the acts of wicked men; and being compelled by the force of truth, he at the same time not only laid open the doings of others, but convicted himself of the same acts. Is it not, then, a miserable inference, to conclude from the same works that the one is God and the other sorcerers? Why ought the others, because of these acts, to be accounted wicked rather than this man, seeing they have him as their witness against himself? For he has himself acknowledged that these are not the works of a divine nature, but the inventions of certain deceivers, and of thoroughly wicked men.

~ Samples, Kenneth Richard. ‘Without a Doubt: Answering the 20 Toughest Faith Questions

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of a young woman in red - Met Museum Collection

Inventory Number: 09.181.6 Roman Period, A.D. 90–120 Location Information: Location Unlisted

Description:

The background of this portrait was originally gilded, emphasizing the divine status of the deceased young woman. She looks at the viewer with large serious eyes, accentuated by long lashes. A mass of loose curls covers her head, and some strands fall along the back of her neck on the left side. Framed by the black hair, deeply shadowed neck, and dark red tunic, her brightly lit face stands out in appealing youthfulness, an impression that is heightened by the gold wreath and sparkling jewelry.

#Portrait of a young woman in red#met museum#09.181.6#panel portrait#location unlisted#roman#womens hair and wigs#RPWHW

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINTS FOR FEBRUARY 15

St Jovita and Faustinus. For their fearless preaching of the Gospel, they were arraigned before the Roman Emperor Hadrian, who at Brescia, Rome and Naples, subjected them to frightful torments, after which they were beheaded at Brescia in the year 120. Feastday Feb 15

St. Dochow, 473 A.D. Monastic founder from Wales, possibly a bishop. Dochow formed a monastery in Cornwall, England. The Ulster Annual describes him as a bishop.

St. Berach, 6th century. Irish abbot and nephew of St. Freoch. He was raised by his uncle and became a disciple of St. Kevin. Berach, who is sometimes called Barachias or Berachius, founded an abbey at Clusin-Coirpte, in Connaught, Ireland. He is the patron saint of Kilbarry, County Dublin.

St. Farannan, 590 A.D. Abbot and Irish disciple of St. Columba on Iona, Scotland. He returned to Ireland to become a hermit at AllFarannan, now Allernan, Sligo.

Saint Claude de la Colombiere, Roman Catholic Jesuit Priest. a Roman Catholic priest and the confessor of Saint Margaret Mary Alacoque. His feast day is the day of his death, 15 February

ST. ONESIMUS, DISCIPLE OF ST. PAUL, Onesimus was a Phrygian by birth, slave to Philemon, a person of note of the city of Colossae, converted to the faith by St. Paul. Feb. 15

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mysterious 12-Sided Roman Object Found in Belgium

A fragment of a mysterious artifact known as a Roman dodecahedron has been found in Belgium.

A metal detectorist in Belgium has unearthed a fragment of a mysterious bronze artifact known as a Roman dodecahedron that is thought to be more than 1,600 years old.

More than a hundred of the puzzling objects — hollow, 12-sided geometric shells of cast metal about the size of baseballs, with large holes in each face and studs at each corner — have been discovered in Northern Europe over the past 200 years. But no one knows why or how they were used.

"There have been several hypotheses for it — some kind of a calendar, an instrument for land measurement, a scepter, etcetera — but none of them is satisfying," Guido Creemers (opens in new tab), a curator at the Gallo-Roman Museum in Tongeren, Belgium, told Live Science in an email. "We rather think it has something to do with non-official activities like sorcery, fortune-telling and so on."

Creemers and his colleagues at the Gallo-Roman Museum were given the fragment by its finder and identified it in December. It consists of only one corner of the object with a single corner stud, but it is unmistakably part of a dodecahedron that originally measured just over 2 inches (5 centimeters) across.

Metal detectorist and amateur archaeologist Patrick Schuermans had found the fragment months earlier in a plowed field near the small town of Kortessem, in Belgium's northern Flanders region.

Creemers said the Gallo-Roman Museum already displays a complete ancient bronze dodecahedron found in 1939 just outside Tongeren's Roman city walls, and the new fragment will go on display next to it in February.

Mysterious dodecahedrons

The first Roman dodecahedron to be discovered in modern times was found in England in the 18th century, and roughly 120 have been found since then in Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

It's not possible to date the metal itself, but some dodecahedrons were found buried in layers of earth that date them to between the first and fifth centuries A.D.

The mystery doesn't end there; archaeologists cannot explain the geometric artifact's function, and no written record of the dodecahedrons has ever been found.

It's possible they were used in secret for magical purposes, such as divination (telling the future), which was popular in Roman times but forbidden under Christianity, the religion of the later Roman Empire, Creemers said. "These activities were not allowed, and punishments were severe," he explained. "That is possibly why we do not find any written sources."

Several explanations for the mysterious artifacts have been suggested over the years. Initially, they were described as "mace heads" and were thought to be part of a weapon. Other ideas are that they were tools for determining the right time to plant grain (opens in new tab); that they were dice, or other objects for playing a game; and that they were instruments for measuring distance (opens in new tab), possibly for finding the right range for Roman artillery, such as ballistas.

A recent suggestion is that dodecahedrons were knitting patterns for Roman gloves.

But most archaeologists think the objects were probably used in magical rituals. The dodecahedrons have no markings indicating how they were used, as might be expected for measuring instruments, and they all have different weights and sizes, ranging from 1.5 to 4.5 inches (4 to 11 centimeters) across.

Roman dodecahedrons are also found only in the Roman Empire's northwestern areas, and many were unearthed at burial sites. These clues suggest that the cult or magical practice of using them was restricted to the "Gallo-Roman" regions — the parts of the later Roman Empire influenced by Gauls or Celts, according to Tibor Grüll (opens in new tab), a historian at the University of Pécs in Hungary who has reviewed the academic literature (opens in new tab) about dodecahedrons.

Ancient puzzle

Creemers said the dodecahedron fragment found near Kortessem could shed more light on these mysterious metal objects. Many other Roman dodecahedrons were first recognized for what they were in private or museum collections, so their archaeological context is unknown, he said.

But the location of the Kortessem fragment is well documented, he said; and subsequent archaeological investigations have revealed mural fragments at the site, indicating that it may have been a Roman villa.

A translated statement by the Flanders Heritage Agency (opens in new tab) said the fractured surfaces of the fragment indicate that the dodecahedron had been deliberately broken, possibly during a final ritual.

The location will now be monitored for further finds.

"Thanks to the correct working method of the metal detectorist, archaeologists know for the first time the exact location of a Roman dodecahedron in Flanders," the statement said. "That opens the door for further research."

By Tom Metcalfe.

#Mysterious 12-Sided Roman Object Found in Belgium#archeology#archeolgst#metal detector#metal detecting finds#roman dodecahedron#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

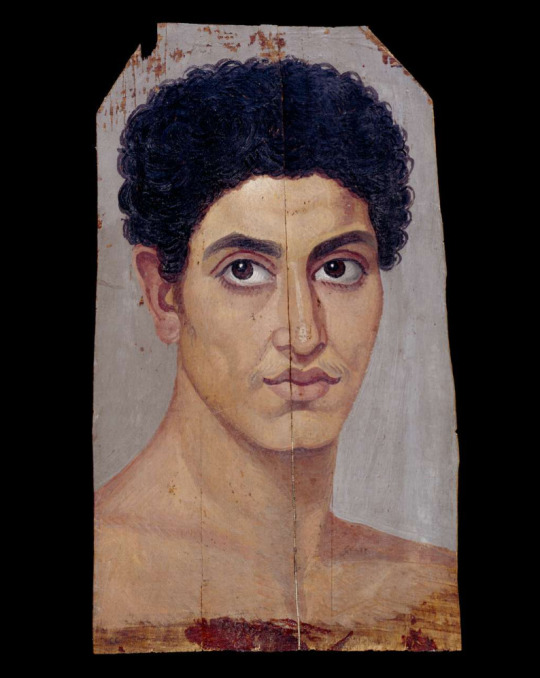

Limewood panel depicting a young man Hawara, Medinet al-Faiyum, Egypt. c. 80-120 A.D. British Museum. EA74711

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

CANARIAS EN LA ANTIGUEDAD

Los primeros visitantes de las islas Canarias fueron fenicios, así lo atestigua restos de construcciones en Lanzarote y alguna ciudadela de bajo del mar en otras islas, pero porque los romanos omiten el hecho de estar habitadas y en cada isla hay una variante diferente de la cultura Amazigh, lo sabremos con el tiempo.

G Ancor Kanarii

De Tagoror Cultural del Pueblo Guanche:

Las Islas Canarias eran ya conocidas en la antigüedad como lo atestiguan las citas que sobre ellas hacen Homero y Estrabón.

Es probable que los primeros exploradores que alcanzaran sus costas fueran navegantes fenicios originarios de Sidón y Tiro. Herodoto habla de una expedición fenicia que circunnavegó Africa en el 6 siglo a.J:C.

Así mismo, Cartago, colonia fenicia norte-africana, envió una expedición de colonizadora de 30,000 personas hacia el oeste de Africa aproximadamente hacia el año 425 antes de nuestra era, habiendose encontrado monedas fenicias en las Azores.

Hacia el año 120 los marinos de Tiro afirmaban que el mundo habitado limitaba al oeste con las Islas Afortunadas. Las Islas Afortunadas como el extremo occidental del mundo conocido fue establecido más formalmente cuando Ptolemeo (90 - 168), las adoptó como el primero meridiano para su Geographia.

Esta fue el mapa clásico más famoso del mundo, utilizado durante casi 1500 años, hasta aproximadamente el año 1800. Los mapas holandeses utilizaban la cumbre DE ECHEIDE como su primero meridiano.

Los romanos exploraron las Islas Canarias tal y como lo prueba la descripcion que Plinio el Viejo hizo sobre la expedición enviada por Juba II, gobernador del protectorado romano de Mauritania (el actual Marruecos) aproximadamente entre el año 29 a.de J.C. y el 20 de nuestra era.

Las islas fueron encontradas deshabitadas durante esta expedicion si bien encontraron un templo en Junonia (el nombre romano para La Palma) probablemente evidencia de habitantes anteriores.

Alrededor del fin del 13 siglo, las Canarias fueron redescubiertas por una flota genovesa dirigida por Lancelot Malocello.

Un estudio más detallado fue hecho por Nicolas de Recco de Genova en 1341. Un documento papal de 1433 otorga derechos sobre las Islas Canarias a Henrique el Navegante de Portugal, pero esta decisión se invirtió en 1436, cuando el papa concede estos derechos a la corona de Castilla,tras su vil invasion . En el tratado de Alcovaça de 1479.

Portugal reconoció los derechos del Castilla sobre las Canarias, a cambio del reconocimiento castellano de la soberanía portugesa sobre Fez y Guinea.

En el momento de la invasion estaban habitados por Guanches. Se sabe de las similitudes culturales guanches con las tribus bereberes de las montañas del noroeste africano. Cómo ellos alcanzaron las Canarias ha sido tema de muchas especulaciones, ya que segun se dice carecían de conocimientos de navegación, hecho extraño si se tiene en cuenta que eran personas que vivían en islas pequeñas con otras islas cercanas claramente visible.

Hay evidencia de dos tipos raciales diferentes, normalmente llamados cromañon y mediterraneo. Los restos de alfarería sugieren que hubo cuatro olas distintas de colonizacion, fijando la datación por el carbono 14 para la llegada de los primeros colonos durante el primer millenio a. JC.

https://www.facebook.com/G.ANCOR/posts/pfbid02YhMNYuvy8Md5jpz6ZvVXMBn9iXAukRJK65UJx2yytvWAorxL3R9hNpnShn6VvaYTl?__cft__[0]=AZUJWnqjUNItZ3feyCMaQRh9S5z8krdYXbntNJzS9pi-sE_ZRsTrhNYL0vjdwppN_Sm8iyAm8IMVLpV9WRhk1ETLz5gYGPW9YcNtJxCJoWybyB0osmwiUCPilNRjEui64Zux4yuB2w3ZMsNz446ZMVdeD7ym2ALyXF-IdHVh-YaU_A&__tn__=%2CO%2CP-R

#fenicios#romanos#amazigh#canarios#guanches#africa#indigenous#aborigenous#culture#history#genocide#native#unesco#united nations#international criminal court#cou penal international#corte penal internacional#indigenas#aborigenes#cultura#historia#genocidio#nativos#naciones unidas#canarias la colonia mas antigua del mundo#canarias tiene identidad cultural propia#descolonizacion de canarias#canarias#onu#un

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Can't get this idea out of my head. It's been on the back burner for so long that I want to write it). Probably going to start a Loki x OC story soon.

Identity

· Full Name: Asta Skírnisdóttir (real name: Nienna) (the picture above is her Vanir form).

· Age: 1,045

· Date of birth: 966 A.D.

· Gender: Female

· Place of birth: Vanaheim

· Race/Ethnicity/Species: Dark Elf/Vanir

Physical Description

· Height: 165.1 cm (5'5")

· Weight: 54.4 kilos (120 lbs)

· Hair color: black

· Hair length: long

· Hairstyle: her hair is loose with numerous thin braids spread all over. Though she sometimes wears her hair in a ponytail with the sides braided.

· Eye Color: blue-gray

· General body description: lean with toned muscles in her arms and her back from years of archery.

· Typical clothing style: she wears flax linen tunics with an apron over them. Her most common outfit is a blue flax linen tunic with brown accents and a green apron; both with an intricate trim around the sleeves, neck, and hem. With them, she wears a leather belt with a molded brass clasp, lightweight leather sandals, and a pair of etched brass oval brooches.

6 notes

·

View notes