Performer, Educator, Composer. For more information visit http://www.nathansantos.com

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Rush Fish-Eye Lens: To Sow A New Mentality

When they turn the pages of history

When these days have passed long ago

Will they read of us with sadness

For the seeds that we let grow

We turned our gaze

From the castles in the distance

Eyes cast down

On the path of least resistance—Neil Peart (1977)

August 9, 1974 marks the surreal moment remembered for the curt, farewell wave followed by fingers outstretched with the "V" for victory sign of a crumbled presidency, as number 37 boarded the helicopter to depart his coveted, elected position in disgrace. The evening before, just following his final address to the American nation, Richard Nixon had this brief exchange with Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger: “History is going to record that you were a great president,” Kissinger assured Nixon. “Henry,” the president said, “that will depend on who writes the history.”

The overwhelming power of the youthful Boomers was realized in the 1970s as many iconic “kings” were pressured into making farewell waves: Watergate and the debilitating end of the Vietnam War underscored the influence of journalism to translate popular opinion into action. By the decade’s end, “progress” would be defined in such ways as the overthrow of the Iranian shah by the revolutionary, theocratic regime led by Ayatollah Khomeini, Ronald Reagan’s rise by courting the Religious Right, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s deregulation following Premier James Callaghan’s ‘Winter of Discontent’ (named after Shakespeare’s Richard III). The music industry would also report farewell waves by kingly icons: the disbanding of The Supremes, Led Zeppelin’s final U.S. performances, and the tragic deaths of Elvis Presley, T Rex’s Marc Bolan, members of Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Bing Crosby.

As further evidence of the postmodern confusion in 1977 over what is deemed progressive or primitive, popular culture became fascinated with punk as represented by such groups as The Clash, The Ramones, and the Sex Pistols while also extolling soundtracks to the Studio 54 hedonistic discotheque and Saturday Night Fever celebrity lifestyles as pointing the way to the future. The most popular band of the day, Kiss, and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s blockbuster megamusical portrayal of Eva Perón were just a few examples of trending anti-heroes seeking influence over a mass following.

Another manifestation of postmodern revisionism the mid-1970s was the preoccupation with Renaissance icons and dynamics. This urge to look back with modern eyes and repurpose archetypes, sounds, fashion, etc. perhaps aimed to project Boomer transcendentalism and proselytization.

Byproducts of systemic dysfunction in the 14th century yield alarming lessons for us in our time: The Great Schism (1378-1417), The Black Plague (1346-1353), and the 100 Years War (1337-1453) undermine the hope towards progress invested in religion, technology, and ideology respectively, and can result in unintended monumental disaster when they are implemented as tools for massification. What followed the 14th century was a cultural correction and the period of time was given the name Renaissance. In Ayn Rand’s view, “The Renaissance was specifically the rebirth of reason, the liberation of man's mind, the triumph of rationality over mysticism - a faltering, incomplete, but impassioned triumph that led to the birth of science, of individualism, of freedom.” The resurgence of Renaissance-era style surely expressed the bidding farewell to perceived “kingdoms” built in the post WWI-Vietnam War era for José Ortega Y Gasset’s “mass-man.”

In June of 1977, Rush had just completed a sixteenth-month tour supporting their career-saving project, 2112, and decided to maintain creative momentum on a new project without respite. Their decision to record in Wales perhaps itself invited ideas that were evoking the Renaissance, but certainly the themes they deployed confirmed these impulses. This new material would be released as A Farewell to Kings on September 1, 1977.

The idea binding the material follows: “accepting that the former time ruled by heroic rulers is now passing, we must rediscover a lost capacity to discover between right and wrong.” These songs all examine the consequences of overreach and begin to suggest the reconciliation of the mind and heart with the acceptance of civic responsibility and accountability. A balance can be reached when philosophers, ploughmen, blacksmiths, artists each “plays his part,” thus “sowing a NEW mentality.”

youtube

In addition to rhetoric, their own evocation of Elizabethan-age setting was further achieved with the addition of primitive instruments and cover art. Pastoral sounds of birds chirping and nylon-strung guitar are heard in the opening moments of the record, reed-sounding keyboard (moog), percussion such as tubular bells, temple blocks, windchimes, bell tree and even vibra-slap can be found throughout.

Hugh Syme’s album art contains an industrial wasteland (depicted by a midrise apartment block and pylon in the background and a dilapidated building and debris in the foreground) is juxtaposed with the focal image of a marionette puppet dressed as a king, sitting on a burnished throne. A cape thrown over one side of the throne shields the figure from the wasteland, but he has lost his sovereignty: his body has fallen over to the left, his crown on the floor out of reach on the other side of the throne; his costume is awry and ragged; and the marionette strings are seemingly disused – an image reinforced on the reverse of the album cover, where we see red strings descending limply against a black field, without a puppeteer in sight.

youtube

In their roles as troubadours, Rush continued to wander the face of the Earth now with the confidence that their unique perspectives on their time were having impact. Interest in creating denser textures and exploring even deeper philosophical areas were presenting even greater challenges for them to pull off as a traveling trio in an FM radio world. Undeterred, they continued progressing forward, boarding the spaceship Rocinante and navigating it towards Cygnus X-1 to get a closer look, and were pulled into their most intense Prog adventure yet….

#rush a farewell to kings#geddy lee#alex lifeson#neil peart#renaissance#Revolt of the Masses Jose Ortega Y Gasset#evita#Richard Nixon#1977#nathan santos

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rush Fish-Eye Lens: Assuming Control

Many works of art enjoying sustained appreciation often contain multiple layers of understanding that may invite/require frequent revisits to reach full comprehension of the creator’s intent. These works can operate successfully on each level independently and thus serve many purposes. In contrast, other works in service to commerce often are created to have maximum impact in the present, and are resigned to a limited shelf life. While all music has a purpose, it is also true that creative aims are not monolithic, but instead exist somewhere on a wide spectrum. This can create conflict if the artist(s) are contractually bound to a larger network supporting the endeavor. An issue of who is controlling the content emerges and the resulting products can be a reflection of the dynamics of this network.

At the time that the Canadian power trio, Rush, was finishing a lackluster tour promoting the weak commercial performance of their third album, Caress of Steel, there were many major cultural shifts underway setting the stage for a broader cultural war; one, it can be argued, that is still being waged. 1976 was the bicentennial celebration of the American Revolution, and in many respects the original revolutionary tenet of “the individual vs. the machine” was very much on people’s minds two hundred years later. Ascendant were conversations about feminist and gender equality, environmental concerns, influence of the Evangelical community, stirring of Islamic politics, racial and ethnic identity, and resistance to the heavy-handedness of corporations directing the entertainment industry.

Artists of this time played the role of vox populi, and groups such as Queen and Kiss penned a number of anthems to stir large arenas into unified chants channeling revolutionary fervor to oppose conventionality. The English band, Pink Floyd, utilized a vehicle of musical commentary through their string of influential concept albums. Their Wish You Were Here album from 1975 describes the band's disillusionment with the music industry as a moneymaking machine rather than a forum of artistic expression. The plot features an aspiring musician getting signed by a seedy executive to the music industry, "The Machine". Dystopian settings were in vogue in all areas of art expressing anxiety of the influence of technology, religion, ideology, and other agents of conformity.

It was at this time that Rush, supported by Mercury Records, arrived at a directional crossroad preparing for their fourth recording project. Rush manager Ray Danniels received pressure from Mercury to see that Rush’s next project be commercially accessible, or they would be dropped from the company. Rush’s recalcitrant answer to the label’s ultimatum was to maintain artistic integrity and stay the course. What resulted from their own act of insubordination was THE bull’s eye strike that earned them the permanent license to control their aesthetic vision. This project given the title, 2112, repurposed Ayn Rand’s Anthem (1937) novella, with additional inspiration from Samuel R. Delany’s Babel-17 (1966) and Nova (1967). Rush’s resistance to massification resonated with their audience profoundly, and they would maintain elements of their resistance throughout the remainder of their work together.

The mini-opera that comprises the entire first side of this album tells the cautionary story of a theocratic regime that has gained total control of the inhabitants of Megadon in the year 2112 and has instituted a collectivist state depriving the population of individual identity and artistic expression. By chance, a guitar is discovered in a cavern behind a waterfall by an anonymous escapee. Determining that introducing this obsolete, primitive technology might enrich their society, the protagonist presents it to the autocratic Priests, who summarily ridicule him and dismiss the idea as unproductive and dangerous. Throughout the entire suite, Rush invokes the combative 1812 Overture (1880) by Peter Tchaikovsky, the Gospel of Matthew, and even G.W.F. Hegel’s “unhappy consciousness” and “beautiful soul” from The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) in the masterwork. The second side of the album, although not a part of the “2112” suite, continues the thematic motifs describing the traveling to internal and external places and discovering transformative ideas.

This music IS multi-layered and overtly critical of the collectivist ideology. Graphic designer Hugh Syme’s depiction of The Starman on the album cover also underscored the battle waged by “the individual” that was so much a part of the Boomer raison d’être. This material was criticized by leftist journalist, Barry Miles in the March 4, 1978 article in the New Musical Express calling Rush “right-wing propagandists” and even equated them with Nazis (“shades of the 1000-year Reich”). Nonetheless, their following was secured and they would remain in the domain of The Starman, resist pressure to compromise their principles, and steadfastly offer their unique perspective on life.

#nathanhsantos#RUSH#rush 2112#ayn rand anthem#progressive rock#hugh syme#geddy lee#neil peart#alex lifeson#pink floyd wish you were here

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Rush Fish-Eye Lens: Bastille Day, The Opening Salvo in the War for Creative Freedom

“Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.” –J.R.R. Tolkien from “On Fairy-Stories” (1939)

In 1958, Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith published “The Affluent Society” describing a postwar era’s achievements in manufacturing and distribution, and the growing dominance of America’s corporations (Coca-Cola, Kodak, GM, Ford, Levi’s, Exxon, I.T.T., Holiday Inn, McDonald’s, etc.). Accordingly, the valiant G.I. “Greatest” Generation returned from their heroic battles anxious to establish their own modest kingdoms within the new neighborhoods built by William Levitt, himself another enterprising G.I. entrepreneur developing a formidable institution called suburbia. The homogeneity resulting from FDR’s mobilization of American Nationalism to overcome external threats and economic depression became the modus operandi of those seeking to make the “American Dream” reality at war’s end.

This embrace of conformity would not be universally shared however. Far from celebrating achievement, the intent of Galbraith’s report instead was to draw attention to widening economic disparity. For her part, political activist Malvina Reynolds communicated her sanctimony for this ticky-tacky uniformity in her 1962 song, “Little Boxes.”

youtube

Likewise, the children born into this suburban Utopia, The Boomers, would grow increasingly antsy, seeking any and every means to escape the cohering values of their Veteran parents, voiced their rebellious views at every opportunity. The “turn on, tune in, drop out” generation embraced and explored escapism in the arts, their self-directed lifestyles, exercise (aerobics, biking, martial arts, disco dancing, roller skating, sexuality), Transcendental Meditation, and recreational drug use (LSD, marijuana).

Reflecting this escapist strain, this era produced multiple expressions of Fantastic Neomedievalism. In 1966, the Society for Creative Anachronism was formed, dedicated to representing life in the pre-modern Medieval Era, donning appropriate wardrobe, engaging in physical activities such as archery, and reviving Medieval dance. 1974 witnessed the publication of the RPG Dungeons & Dragons. Monty Python’s zany telling of King Arthur, Monty Python and the Holy Grail premiered in 1975.

The animated interpretation of J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Hobbit was released in 1977. And also in 1977, Star Wars made a debut evoking knighthood order and the John Campbell-inspired hero’s journey archetypes.

Music similarly embraced Elizabethan Era themes with Jethro Tull’s Minstrel In The Valley (1975) and the Led Zeppelin masterwork, “Stairway To Heaven” (1971). Zeppelin created lyrics that were inspired by Robert Plant’s Arthurian search for spiritual perfection, and contains references to May Queens, pipers, and "bustling hedgerows.” The track even uses a Elizabethan recorder consort.

In July of 1975, RUSH, having just been awarded a Juno Award for “Most Promising Group” anxiously entered the recording studios to begin their follow-up project to the successful Fly By Night album and tour. For Caress of Steel, their chosen direction likewise channeled escapist Fantastic Neomedievalism and embraced Progressive Rock conceptualization in epic musical storytelling. Typically youthful inclinations of separating themselves from their formative suburban upbringing was fully imagined in a side long, six song cycle called “The Fountain of Lamenth” where an arduous search for their Holy Grail led them to also a typically inconclusive ending. Another long track featured the Tolkein Necromancer as the subject of their composition, in addition to making the image the focus of their album cover. This artwork marked the first with long-time RUSH cover artist, Hugh Syme.

With the benefit of hindsight, we in 2020 can place this particular album into context of that time with a clearer understanding of these ambitious musicians. Often the notable anecdote of RUSH’s introduction of this freshly recorded material to their touring partner, Paul Stanley of KISS, where he tacitly stared nonplussed at the floor and uncomfortably listened to their insular musings is revisited when describing their collaboration still in an early phase. Unfortunately, lagging record sales support their own self-deprecation when referring to their lamentation of these abstract experiments, as did the dwindling crowds at remote locations on a tour that they have since dubbed the “Down the Tubes” tour. We must remember that these were merely 22 year olds who were nerds at heart. KISS’s Gene Simmons still expresses his disbelief when telling tales of engaging in his own and numerous notorious tour conquests while walking past a hotel room where RUSH in stark contrast were immersed reading novels. Although Geddy Lee does admit that they themselves may have been too high when recording Caress of Steel.

Nonetheless, the opening track of this album was a bombastic one that can now be understood as a bold statement of defiance, daring, and determination. “Bastille Day” expresses the march towards their own revolution. Certainly, they were not going to allow “kings” to determine the course of their collaboration. They were seeking to “free the dungeons of the innocent” and to never again “bow to the king.” RUSH was given notice by their business representatives that either they adjust to commercial demands or they’re label support would be terminated. Unwilling to surrender their ideals to The Priests of the music industry, RUSH pushed back and “assumed control.”

Terminat hora diem; terminat auctor opus

youtube

#RUSH#Caress of Steel#j.r.r. tolkien#Nathan Santos#Kenneth Galbraith#malvina reynolds#monty python and the holy grail#fantastic neomedievalism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rush Fish-Eye Lens: The Virtue of Selfishness

There's a time for feeling as good as we can

The time is now, and there's no stopping us

There's a time for living as high as we can

Behind us you will only see our dust

So we'll just keep smiling, move onward ev'ry day

Try to keep our thoughts away from home

We're travelling all around, no time to settle down

Satisfy our wanderlust to roam…

from Making Memories (1974)

When Neil Peart penned these lyrics as a young man in his early 20s, he was roaming around the United States in a new music ensemble from Toronto. He was hastily hired into this group who had only two weeks to replace their original drummer before embarking on their first American tour. His drum audition for this group, RUSH, sufficiently impressed original members Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson musically, although they were concerned that his appearance did not entirely suit the “Rock” image. What longtime friends Lee and Lifeson would soon learn about “the new guy” as they all became close was that his predilection for reading and word craftsmanship would provide meaningful direction for their songwriting.

Only ten years prior to this union of Canadian artists, the Russian-American writer Ayn Rand published a set of essays called The Virtue of Selfishness codifying foundations for her philosophical system, Objectivism. Her validation of egoism and assertions exposing altruism as a destructive practice also reflected the modus operandi of that era’s youth, the postwar Boomer generation. In the year of Rand’s publication immediately following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the first wave of Boomers began entering higher education armed with numerous loud voices demanding the freedom to express their individuality. This cohort who were the recipients of Dr. Spock permissiveness collectively escaped their suburban conformism and established the era of self-fulfillment that journalist Tom Wolfe in 1976 coined as the “ME Decade.”

Prior to joining RUSH, Peart discovered Rand’s novels while pursuing a music career in England. Unable to establish networking momentum, he began filling the unproductive time avidly reading. While working at The Great Frog on Carnaby Street selling trinkets and jewelry, he immersed himself in the world of Rand’s Fountainhead, Atlas Shrugged, and Anthem, and developed a perspective that would inform the lyrics set to music by Lee and Lifeson. He worked only a short distance away from Charing Cross Road where was located Better Books, the London bookstore that fostered the counterculture scene by future RUSH critic Barry Miles. Peart’s failed English springboard disillusioned him and he returned back to his native St. Catherines, Ontario to work for his father’s tractor parts business.

youtube

RUSH with Peart as drummer, lyricist, album cover supervisor, tour book director (among other tasks), forged a longevity formula remaining together through the turbulence of the ever-changing industry and their personal lives. With the benefit of hindsight, their initial collaboration can be understood as establishing a process oriented towards achieving the highest possible standards. At the time though in 1974, their first serious tour together supporting groups such as Uriah Heep and Manfred Mann’s Earth Band provided them with their first opportunity to collaborate on material for their first album together.

From the very first composed syllable, RUSH established their Randian cred. Just as Rand defected from the communism of Soviet Russia in 1926, Fly By Night voiced thematically a desire to escape “begging hands and bleeding hearts” and to “write songs for themselves.” A paean to the ME decade, their ideas epitomized the zeitgeist of self-absorption. The 1970s witnessed a culture preoccupied with health food, hot tubs, physical exercise, Kung Fu, therapy, Helter Skelter cults, and fervent Environmental activism akin to religiosity. Simultaneously, the Religious Right was ascendant and the Southern Strategy was underway. RUSH’s following was built atop this foundation, and remains faithfully committed to the ideals that their artistic collaboration expressed.

youtube

Recorded in ten days in Toronto, their first album together, Fly By Night, was released 45 years ago. The themes they explored expressing the desire to embark on the “Hero’s Journey” updated Aristotelian thought: that each man’s life has a purpose and that the function of one’s life is to attain that purpose. This purpose can be achieved via reason and the acquisition of virtue. Each human being should use his abilities to their fullest potential and should obtain happiness and enjoyment through the exercise of his realized capacities (individualism). For this, they were awarded Juno Award for Most Promising New Group. Nearly 40 years later, their rich body of work was validated by induction into the Rock Hall of Fame. Their anthems will continue to resonate for they have created together a profound body of work inviting deep exploration and giving us a better understanding of this next period of Awakening.

youtube

#rush band#geddy lee#alex lifeson#neil peart#Ayn Rand#Objectvism#Fly By Night#Anthem#Nathan Santos#me decade#Tom Wolfe#awakening#aristotle

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rush Fish-Eye Lens: Codes of Authenticity

The Birmingham Blitz was the heavy bombing campaign carried out by the Nazi German Luftwaffe in central England between 1940-43. Around 1,852 tons of bombs were dropped, decimating this highly populated area. Urban renewal followed to remedy the blight left in the ruins of WWII. Just twenty-five years beyond the sounding of the final warning siren, this bleak, industrial, noisy town would bring together the group known as Black Sabbath whose aesthetic reflected the working class attitude and established the prototypical Heavy Metal sound, fashion, and ethos. Two other English groups representing this rising culture were Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple. Collectively, codes of authenticity were established that has given identity to so many subsequent musicians seeking to flout the pervasive commercialism characterized in John Kenneth Galbraith’s Affluent Society.

Codes of authenticity established by Heavy Metal culture largely characterized a young, white, male, blue-collar demographic base. They promoted opposition to authority and separateness from the rest of society. Performers appear both completely devoted to their music and loyal to the subculture that supports it. The sounds they generated were aggressive, distorted, and very loud. Their uniform consisted of torn blue jeans, black T-shirts (often displaying the logo of their preferred band), boots, and black leather or denim jackets, and their long unkempt hair flowing down their back. Following these codes insured acceptance into this alienated culture. It did not take long for this culture to increase its population as intransigence implanted in the wake of Vietnam, high profile assassinations, race riots, and other signs of unraveling.

Across the Atlantic Ocean in the Commonwealth Realm of Canada, a similar counter-culture youth movement was percolating within the booming suburban towns. The postwar elimination of racially based immigration policies brought streams of European refugees, Chinese job seekers, as well as construction laborers from places like Italy and Portugal to double the population in areas such as Toronto. Yonge Street witnessed a very influential music scene represented by such luminaries as Robbie Robertson, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Gordon Lightfoot.

In one of these suburban towns of Toronto there were a few schoolmates who discovered a mutual obsession in music and decided to begin jamming together as a group. Alex Zivojinovich, Gary Lee Weinrib, and John Rutsey, enamored with groups such as Cream and Blue Cheer likewise played as a power trio. A few months later, a new group from England, Led Zeppelin, visited Toronto for the first time in February of 1969. In August, Zeppelin returned to Toronto just days after the Woodstock Peace Festival ended, and in the audience was the young impressionable trio from Willowdale who aspired to begin their rock and roll journey as RUSH.

Their first independently produced album contained sounds and themes deriving from the same places as Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Cream, Deep Purple, Blue Cheer, and others: a paean to the blue-collar, industrial, masculine, alienated, and anonymous laboring class reflected that their home experience. They adopted the same codes of authenticity, and maintained them for the next 40+ years, endearing them to a loyal audience who rejoiced in the group’s unpretentious approach to musical storytelling. It is not surprising that their initial breakthrough would occur at such rust belt cities such as Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Detroit. Donna Halper, the pioneering DJ at WMMS in Cleveland explains that upon first receiving a copy of Rush’s first eponymous record, she chose to play “Working Man” merely because it was a lengthy track that enabled her to run to the restroom. But little did she know that the audience hearing about the banality and redundancy of the laborers life would immediately react to what they thought was a new Led Zeppelin song. Now as Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee, and John Rutsey, Rush would be launched.

youtube

Halper’s identity as a very early agent in breaking the glass ceiling in the male-dominated world of radio is also profoundly significant when considering codes of authenticity. The lingering inside joke about the lack of women in Rush’s audience might be traced to these codes and the Honeymooners-like paternalistic mood of the postwar era. Second-wave feminism and the LGBTQ community were just beginning to agitate for changes in the workplace, then the home, church, and other institutions. Even with Neil Peart’s replacing of John Rutsey in the timekeeping role, the group would continue to promote an Apollonian rather than Dionysian approach to their work keeping them mainly in the masculine domain.

Perhaps the most impressive code is the total devotion that also undergirds the longevity of these groups. The commitment to maintaining values leads to a recalcitrance in both the performers and the audience, and avoids the pitfalls of commercial fickleness. Rush was a group that was in the race to stay and to make the most of the distance. They accepted who they were without compromise and became the defiant voice of the Working Man. Now, as they return to their gardens so nurtured and protected, they can resolutely say that all is for the best.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rush Fish-Eye Lens: Raison D'être

Neil Peart in his eloquence stated that “we are only immortal for a limited time.” Since the news of his passing was made public, there has been a steady outpouring of testimony recognizing the influence of this private man on so many. Throughout his remarkable career he has amassed an unrivaled cadre of fiercely loyal admirers who now are expressing their deep appreciation for his work: billboards, quotations, iconic symbols, personal anecdotes, tour merchandise, ticket stubs, artwork, petitions for permanent playlist on satellite radio, discussions of a statue in Peart’s native St. Catherines, podcasts-- admirers from all walks of life, and spanning multiple generations are now legion.

Peart’s success can be traced to his unpretentious and uncompromising nature. His life was lived as a flaneur with a voracious appetite for knowledge searching for greater understanding of the world that he was exploring. This inclination to be in continuous motion can be identified in his song lyrics, his physical conditioning and ongoing study of drumming technique, his carefully planned bicycle and motorcycling side trips while on tour, his voluminous travel diaries turned into best-selling books, and even the manner in which he dealt with the grief of losing his daughter and wife. He never lost the urge to escape the normalizing forces of his suburban birthplace. His song ideas, while unusual for their avoidance of typical/popular subjects of love or war, nonetheless were completely relatable as they reflected the characteristics of his Boomer cohort and their pugnacious resistance to “massification.”

Peart and his Rush colleagues Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson established an unbreakable bond with their audience after standing firm against the corporate authorities seeking to terminate financial support just as their journey as a collaborative ensemble began. They became the epitome of what the individual will could overcome, maintaining dignity without compromising on their values. As role models, they were elevated to the status of “gods” to their next younger cohort, Generation X. Gen X, the subject of many of Rush’s songs beginning in the 1980s, were viewed as the loners in shopping malls, nobody’s heroes, and the new Lost generation. Xers heard Rush’s Randian advice to trust no one but themselves and were wholly convinced. Rush’s blue-collar origins and their recalcitrant individuality became the voice for the disconnected and distrustful youth who now are breaking their guarded silence to ebulliently articulate how difficult this loss is in their lives, regardless of the fact that they never knew Peart personally.

I, myself had my own brief personal encounter with Geddy Lee at a book signing in Pittsburgh. From the moment I purchased my ticket I wrestled with how I could tell him everything I wanted to tell him in 20 seconds and in a way that would get across how much impact he had on my life, especially in the formative years of figuring out the kind of identity that would characterize me. As I entered the bookstore that hosted the event, I noticed so many different Rush clothes and other fans’ symbols of their allegiance and I got in line. The line began moving me closer to my hero and I observed how EVERYONE wrestled in a similar way. To Geddy’s credit, he endured signing all of those books and as a bonus, he gifted everyone with a short one-liner. Once I reached my moment, I stuttered over what I decided to tell him, and he offered me his one-liner. And, just like that: it was over. Did he get it?

Upon hearing the news of Neil Peart’s passing, I too was grief-stricken. But, he was not my father, spouse, son, neighbor, bandmate, etc. so my mourning could not be the same as his widowed wife, daughter, close friends. I knew that I had only gratitude for what this man represented to me, what I learned from studying his work intimately, and to remind myself that were are truly immortal only for a limited time. We must make the most of the distance, but we must have endurance. My contributions here, in the academic course that I am proud to have organized and presented twice on Rush’s work, the podcast that is about to drop, and the occasions that I have been able to perform Rush’s music in front of audiences are joining a very voluminous chorus, but nonetheless I feel compelled to offer my own thoughts as a token of appreciation.

I will be composing a series of blogs featuring the results of my deeper analysis of Rush and their work as my own tribute. Stay tuned for more…..

youtube

“The Spirit of Radio” (RUSH cover)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Beauty

As a part of America’s Bicentennial in 1976, President Gerald Ford formally recognized Black History Month. The impetus for this month-long celebration began with educators at Kent State University in 1970, and the roots of this historical focus on contributions of people of African descent could be traced to the achievements of Dr. Carter G. Woodson.

Woodson, only the second African-American (after W.E.B. Du Bois) to earn a doctorate from Harvard University championed the cause of researching and preserving the history of African-Americans, and among his many initiatives he launched the celebration of “Negro History Week” in February to coincide with the birthdays of Frederick Douglas and Abraham Lincoln.

The 1970s were rich with images of African pride, and establishing Black History Month at the start of the decade was apropos. The inertia of Black Pride would ultimately result in the historical inauguration of Barack Obama as President in 2009. Pop culture witnessed the popularity of Blaxploitation films such as “Shaft”, television situation comedies starring legendary comics like Redd Foxx, Bill Cosby, Jimmie Walker, and Richard Pryor, the immensely popular Soul Train created by Don Cornelius established an institution that chugged for 35 years, and Hank Aaron and Muhammad Ali hammered, floated, and stung as the most remarkable athletes of the 20thcentury.

youtube

The “Godfather of Soul,” James Brown, saddened by the gang warfare in Compton and Watts, utilized his powerful influence to regain the pride that he felt had been lost in the urban community. Penning what became the anthem of the Black Pride movement, “Say It Loud,” he articulated individual responsibility and the recognition that each person’s uniqueness could energize the whole if the energy directed towards elevation, not destruction. He and his musical collaborator “Pee Wee” Ellis created a musical approach that opened the way for the emergence of Hip-Hop, with their long, looping vamps, the emphasis of beat 1, rather than 2 and 4, the percolating semiquaver guitar and the thumping Fender electric bass soon to be revolutionized by Larry Graham and Bootsy Collins.

It was in this context that Miles Davis permanently separated himself from the traditionalists of modern jazz and fully embracing the zeitgeist. Although baffling the critics who seemed to be invested in jazz music remaining as an elite idiom, those who knew Davis would not be surprised that he supported the Black Power movement fully, and found inspiration in James Brown’s grooves, Richard Pryor’s uncompromising commentary, and the ferocity and cadence of Muhammad Ali. Urged by his young new bride, Betty Mabry, his departure into “Black is Beautiful” fashion was underscored by his fascination with looping funk grooves, inspired by Brown’s “Say It Loud” and his experimentation with electric instruments.

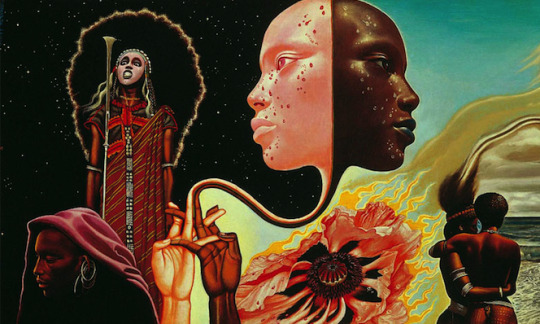

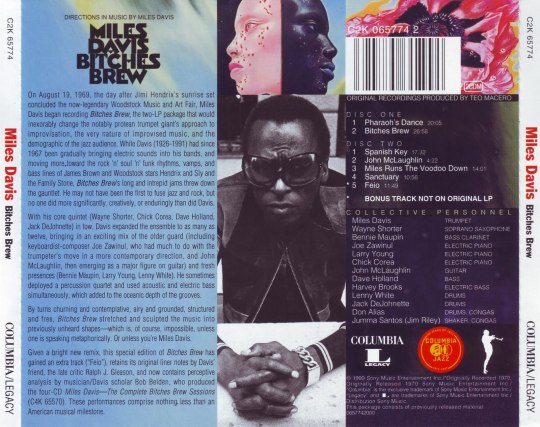

One need only study the covers encasing his newest records of this period to see surrealistic depictions of counterculture Afrocentric expression as in Bitches Brew (1969), urban ghetto caricatures of prostitutes, gays, activists, winos, and drug dealers as utilized on the 1972 project On The Corner to know what Miles was communicating in these years building to the establishment of Black History Month in 1976.

In his final decade of life, Davis’s advocacy of the Black Pride did not abate. His first album on Warner Brothers Records was released in 1986 called Tutu, named for the South African Nobel Peace Prize winner, Bishop Desmond Tutu. The project was another bold step in a different direction, employing Marcus Miller’s many skills to place Miles’s voice into a synthetic, digital context, maintaining the muscularity of a Mike Tyson-like jab, pungent harmonies and the abstraction of random, fragmented solo voices that defined the 1980s.

The follow up to this album was Amandla, a Zulu word for “power” used to bring down Aprtheid. His final collaboration with Miller, Miles explored an amalgamation of styles including West Indian zouk (inspired by Kassav), go-go, hip-hop, funk, and even straight-ahead jazz. The album cover for this project was his own collaboration with his artistic and romantic partner, Jo Gelbard, depicting his self-portrait with a map of Africa embedded within.

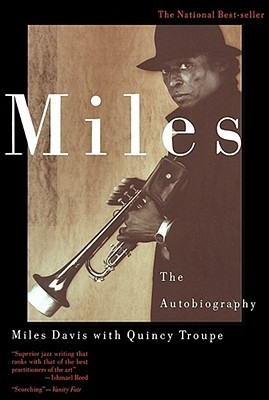

In Quincy Troupe’s newest publication, Miles & Me, he describes Miles as an “unreconstructed black man” with a fiercely tough and unapproachable demeanor, and an uncompromising champion of urban culture. Critical of his heroes Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie for smiling, and emulating the boldness of Jack Johnson in an out of the boxing ring, he represents a figure who spent his life obsessively looking forward and challenging the world to keep up with him. To understand Black History from 1926-1991, one need to look no further than the remarkable life of Miles Davis.

youtube

#miles davis#James Brown#Black History Month#Bishop Desmond Tutu#On The Corner#carter g. woodson#Amandla#Marcus Miller

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miles, Michel Legrand, and the Screen

The recent passing of legendary French composer Michel Legrand has inspired many tributes to his collaborations with Miles Davis. Among the most interesting thoughts that are currently being passed around social media is that Miles contributed to Legrand’s debut project and then at the end of Miles’ life, Legrand was in turn the chief composer for Miles’ final recording studio moments. Additionally, the premier of Stanley Nelson’s much-anticipated documentary Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool at the Sundance Festival reminds us that Miles had a strong connection with the acting world as a film score composer, acting in small roles, and even personal relationships with actors/actresses, artists, dancers, and comedians.

In 1958, Michel Legrand made the trip from his native France to record at the New York Columbia Studio to record what would become Legrand Jazz. This session was offered to Legrand as a gesture of recompense for the unpaid previous work that Legrand had done with Columbia. He gathered thirty-one jazz heavyweights including John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Phil Woods and Eddie Costa to record his arrangements.

On June 25, 1958, Miles arrived to the studio reluctant of his participation, but was convinced when he saw who was there and what Legrand’s music was inspiring. Legrand’s credentials already boasted studies at the Conservatoire de Paris, lessons from the legendary Nadia Boulanger (teacher of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, etc.), and even the first French language rock and roll hit: “Rock and Roll Mops” featuring Henry Cording & His Original Rock and Roll Boys.

youtube

The sessions with Miles produced tracks for Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz” and the Louis Armstrong/Jelly Roll Morton classic “Wild Man Blues.”

youtube

Miles himself was in Paris in the fall of 1957 to be a guest soloist at Club Saint-Germain and visit with his French girlfriend Juliette Greco when he was asked to compose music for the new film in postproduction, L’Ascenseur pour l’Échafaud (Elevator to the Gallows) by Greco’s associate Louis Malle. According to Discogs, “Davis only gave the musicians a few rudimentary harmonic sequences he had assembled in his hotel room, and once the plot was explained, the band improvised without any precomposed theme, while edited loops of the musically relevant film sequences were projected in the background.”

youtube

This was Malle’s first feature film and Miles’ first soundtrack. The music was later released on the 1958 Columbia Records compilation album called Miles Davis Jazz Track and was a very important foreshadowing of how Miles approached his momentous Kind of Blue sessions a year later.

Miles in later years contributed to other film projects. His 1970 music for A Tribute To Jack Johnson was his follow-up to Bitches Brew. The sounds he employed here represent a trend-setting fusion of rock grooves and instrumentation with collective improvisation indigenous to jazz. In October 1986, he played on some tracks for the film Street Smart.

In 1987, he collaborated with Marcus Miller to produce the music for the film Siesta, creating sounds similar to his Sketches of Spain (1960) album. Warner Brothers released the music as an album and it proved to be the second of three projects featuring Miller’s work.

As an actor, Miles appeared as a pimp named Ivory Jones in an episode of Miami Vice, “Junk Love” which aired on November 8, 1985. He also had a quick cameo on Scrooged (1988) performing “We Three Kings” on a Manhattan street corner with fellow buskers David Sanborn, Larry Carlton, and Paul Shaffer while being heckled by cynical network executive Bill Murray.

youtube

As for Michel Legrand, he amassed over 200 film and television scores, 3 Oscars, 5 Grammys, and many songs before his passing on January 26, 2019. His collaboration with Miles on the soundtrack for Dingo was one of Davis’s last before his death in 1991. Miles also starred in the film as Billy Cross, a mentor of jazz trumpet to his young protégé John Anderson. Legrand recalls the collaboration in the November 18, 2016 issue of Downbeat:

Miles could call me anytime, day or night. Miles calls me: “Michel, you need to bring your fucking ass to Los Angeles.” I said, “Miles, don’t worry. You want me, the next day I’ll take the train to Los Angeles.” He said, “Michel, there’s a film, and I want to do it with you.”

So, on the first day, I’m in the area. On the second day, we talk a lot. We go swimming. We drank a lot. It was a Saturday, and we were supposed to record the following Wednesday. So I said, “Miles, we’re supposed to compose it together. We should start to work.” He said, “Work! I don’t want to. Who gives a shit about the film?”

I told him, “If you don’t want to do it, OK. It’s good to relax—to really enjoy, talk about the music, have a beautiful vacation.”

But there was a phone conversation with someone from the studio; they were going to start shooting soon, and they need the playback to help [them] make the film.

I tell Miles, “We said we were going to do it. This isn’t about you, or your Grammys.” He said, “Fuck off! Who gives a shit about this, man?” I recall [a musician had] said, “The way Miles works is this: He goes into the studio with his musicians and—Miles is the laziest man on earth—comes afterwards and puts his trumpet up and overdubs.”

So, I see he’s expecting me to do the same. So, I said, “Miles, I have an idea. I’ll go to my hotel now. I will write everything, the complete orchestration. I will record on Wednesday, all the charts. Come Thursday to the studio and take your trumpet and play.” He said, “Michel, I knew you were a genius.” I record all day Wednesday, and then the next day, Miles comes. I loved that man. So generous, so strong and very open at the same time.

youtube

#michel legrand#miles davis#elevator to the gallows#scrooged#dingo#legrand jazz#miami vice#siesta#marcus miller

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

MLK & Miles Davis: Legacy

The destabilization resulting from tragic and consequential events beginning with President Kennedy’s assassination and into the rise of Postmodernism in the early 1970s created an environment for yet a new means of communicating the conditions of inner-city life. In blighted Bronx neighborhood block parties and house parties, an urban movement began to form expressing the blighted conditions experienced by Black and Latino youth. Their parties were energized by emcees who artfully maintained continuous music by rapping over the breaks of funk songs—the parts most suited to dance, usually percussion-based, were isolated and repeated for the purpose of all-night dance parties. What would emerge from these gatherings contained the necessary inertia to rapidly traverse the globe utilizing the new tools of cyber connectivity.

The culture coined Hip-Hop can be viewed as the predominant manifestation of the Postmodern Era with its use of digital technology, sampling, globalism, and ever-evolving vernacular. In our information-dense modern time, fragmented sound bytes and 280-character messages shape our communication style. “I have a dream” is a brief phrase, but the attribution to Dr. King may be seen in our time as his enduring legacy to the post-Boomer generations who never experienced his living presence.

For Miles, his debilitating depression finally began to subside at the dawn of the 80s, and the challenging sounds by new artists like Prince piqued his interests anew. The remaining decade of his life witnessed his dive into the artificial, synthetic waters of digital technology, drum machines, sampling, colorful artwork, and the introduction of young, pioneering talent feeding his insatiable need to stay current.

Only in the final 5 months of his life in 1991 did he return to material that he previously recorded: the Montreux Jazz Festival revisited his remarkable Gil Evans collaborations and then a concert billed as “Miles and Friends” involving former sidemen. Other than this quick backward glance, he lived his life as the sage griot commenting on the conditions of the moment.

As we customarily begin each new year reflecting on the enduring legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King discussing how his ideas can improve our current cultural conditions, it is useful to also consider the legacy of Miles Davis, who was a mere three years older than Dr. King, and outlived him by twenty-three years. In 2016, marking 90 years following Miles’ birth, the website called The Pudding conducted an extensive search of Wikipedia and found 2,452 pages on which Miles is mentioned. Personal perspectives and research-oriented books such as Quincy Troupe’s Miles and Me and Victor Svorinich’s Listen To This add detail about Miles’ personality.

Also in 2016, a dramatic film rendering his late 70s retirement years was produced entitled Miles Ahead, starring Don Cheadle with soundtrack by Robert Glasper.

youtube

On January 24that the Sundance Film Festival, the debut of Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool directed by Stanley Nelson will run as a preview to the global theatrical release and PBS airing this summer. Samplings of his recordings are still being used by artists such as The Roots, Mobb Deep, The Beatnuts, Black Moon, Heavy D & The Boyz, Outkast, Queen Latifah, and more.

youtube

Dr. King’s unrivaled ability to articulate entreaties for peaceful coexistence in eloquent prose has provided us with a means to discuss our differences and communicate productively. In contrast, Miles Davis’ shy demeanor led him to avoid interviews and develop a detached stage persona never introducing a song or speaking a single word to his audience—he preferred to express himself completely through his horn. But his impact on culture is equally as profound as Dr. King’s. King and Davis represented a generation born into a time of dire turbulence—economic depression, battles over foreign and domestic fascism, and the establishment of individual freedom—the members of which lived their lives working to open doors for others. We celebrate their example, striving to keep our minds open to the challenge of the changing seasons and boldly moving into the future energized about the new sounds that we will make.

0 notes

Text

Post-Bitches Brew Resistance

Miles Davis did not receive universal applause for his crossover into the Boomer world of self-exploration. Some saw his new ideas as a maneuver to erase the debt that had accumulated over the past years exploring inaccessible abstract sounds while living an extravagant life of cavorting with celebrities, traveling overseas, and maintaining a lifestyle of excessive self-indulgence.

Critic Stanley Crouch is one who associated Miles’ post-1968 with Zip Coon-nineteenth century minstrelsy. The attire that Davis acquired and the embrace of calculated gestures to Crouch, similar to the invective leveled at Bob Dylan at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, was a betrayal to his previous association with authentic revolutionaries whose mission was to elevate the race and reject the “Uncle Tom”, “Armstrong-like mugging and grinning” for mass approval. In his 2007 publication, Considering Genius, Crouch eloquently composes these thoughts:

“Gone is the elegant and exigent Afro-American authenticity of the likes of Ellington, at ease in the alleys as well as in the palace, replaced by youth culture vulgarity that vandalizes the sweep and substance of Afro-American life. The fall of Davis reflects perhaps the essential failure of contemporary Negro culture: its mock-democratic idea that the elite, too, should like it down in the gutter. Aristocracies of culture, however, come not from the acceptance of limitations, but from the struggle with them, as a group or an individual, from within or without.” (Crouch, p. 256).

Despite accusations leveled by Crouch and other traditionalists that this music was not true Jazz, what Miles created in August of 1969 immediately resonated as it was representative of the zeitgeist that permeated culture and continues to influence our perception of life in 2019. Multiculturalism, globalism, and synthetic materialism are prominent characteristics of Postmodernism. We challenge language, symbols, credentials, and motivations of those whose authority threatens our personal identity. The need to establish individuality by definition fragments us from the whole, and our own individual whims mandate how the pieces are reassembled or not. Technology reinforces this by allowing our own imagination to define our image, and tribalism influences our choices affecting our instincts for survival. Some describe Miles as selling out, others marvel at his obsession to maintain relevance. Perhaps apropos to our postmodern perception we see what we wish to see, and his true gift was to exist on both sides of the divide. Miles as griot told the story of that moment in time by engaging younger artists and masterfully directing them with his seasoned voice. Judging by audience ovation witnessing his new direction, he converted many.

The cover that adorns his controversial 1969 project is the depiction of Black Power and Afro-centricity. The surreal art was created by Mati Klarwein, an artist who was born to two Jewish parents in pre-war Germany who fled to Palestine with the two-year old Mati to raise him in the ethnically diverse environment of Palestine.

The binary imagery: light and dark, black and white women interlocking heads and fingers, anger and peace, intimacy and loneliness, strength and weakness, bring together opposites and communicate coexistence. Miles’ choice of Klarwein’s art also reflects his own inclinations in support of icons of Black Power, Blaxploitation, and Pan-Africanism.

His reaction to the 1968 murder of Dr. King in Miles, The Autobiography reads:

“Just before we left to do these concerts [in Berkeley, California], Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed in Memphis, in early April. The country erupted into violence again. King had won the Nobel Prize for peace and was a great leader and a beautiful guy, but I just never could go for his non-violent, turn-the-other-cheek philosophy. Still, for him to get killed like that, so violently—just like Gandhi—was a goddamn shame.

He was like America’s saint, and white people had killed him anyway because they were afraid when he changed his message from just talking to blacks to talking about the Vietnam War and labor and everything. When he died he was talking to everyone, and the powers that be didn’t like that. If he had just kept talking only to blacks he would have been all right, but he did the same thing that Malcolm (X) did after he came back from Mecca and that’s why he was killed, too, I’m certain of it.”(Davis, pp. 289-290)

Having passed fearlessly into the new world of electricity, Miles continued to move forward leaving those critical of every new experiment in his wake. He followed Bitches Brew with A Tribute To Jack Johnson, the soundtrack to the 1971 documentary on the flamboyant African-American world heavyweight boxing champion from 1908-1915 and predominant Jim Crow era icon. Miles was obsessed with boxing and idolized champions such as Johnson, Joe Lewis, and Sugar Ray Robinson for their audacity and charisma. His enthusiasm for the sport compelled him to hire a trainer, and experience it as a participant.

youtube

His music betrays the intimate knowledge of this craft in his jab-like fragmented gestures, affinity for shuffle grooves like the dancing motion around the boxing ring, and keen sense of timing required to deliver his strikes with overwhelming results.

The Jack Johnson soundtrack was then followed in 1972 with On The Corner, an album whose sound and album cover go deeper into the James Brown/Sly Stone inspired psychedelic funk and Blaxploitation trend, further confounding those waiting for a nostalgic return to the 1950s. Even as these projects were released, his health and lifestyle excess were beginning to take a toll on his productivity and creative energy, and he began to withdraw into a period of retirement from music and public life altogether.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miles Makes the Boomer Connection

Every jazz musician acknowledges that Kind of Blue represents the pinnacle of the respect paid to Jazz as an art form and no longer a street music or popular dance style. Higher education began legitimizing Jazz at this time by offering formal Jazz Studies in the curriculum. The unfortunate consequence of this though was the continuing commercial decline, as these artists representing The New Thing, or Free Jazz explored abstract textures, formless collective improvisation, and could only find audiences in smaller venues and the college campus. But as the first wave of Baby Boomers entered college in 1964, everything immediately changed.

Muddy Waters’ performance at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, Columbia’s reissue of Blues legend Robert Johnson’s Faustian 1936-37 recordings, and Bob Dylan’s inaugural recording were all signals of a revived interest in folk or pre-modern music. Driving the revival of these primitive sounds were the youthful, outspoken children of the returning GIs following the war.

“The Boomers,” as they would be called (born between 1943-1960), were demanding the freedom to speak their opinions, to “to turn on, tune in, drop out,” and to protest anything that challenged their awakened philosophies. Their numbers were legion and their gatherings were becoming epic. Dr. King’s 1963 Washington D.C. speech, Monterey in 1967 and Woodstock in 1969 were among the most prominent indicators that their voices were not going to be ignored. Miles Davis knew this and was becoming frustrated playing in small clubs. He wanted in.

Electricity has long fascinated the imagination of artists as a symbol of progress and awesome power. Mary Shelley portrayed it as giving life to a monster, Stephen King describes with gruesome detail “Old Sparky” the chair that denied life, and even Miles describes defibrillators to justify the advancement of life due to the harnessing of this power. In the Aquarian era where purity and nature were revered, Bob Dylan’s decision to use an electric guitar at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival was viewed as a betrayal.

But Dylan’s chosen instrument in 1965, the invention of Les Paul and Leo Fender, became THE icon of the youth. Dylan’s electric voice of protest took hold nonetheless, and procession of louder and more distorted sounds accompanied The Byrds on Pete Seeger’s “Turn! Turn! Turn!,” The Who’s “My Generation,” and The Beatles “Revolution,” culminating with the emergence of the most transforming figure of the lot, Jimi Hendrix.

Trading his military armaments for a Fender Stratocaster, Hendrix’s introduction as Counterculture Messiah came at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. His chosen wardrobe, supplied by Stella Benabou and Colette Mimram who owned a shop at 321 East Ninth in the East Village in New York, became as imitated as his amped up style of Blues music.

But his cultural importance was permanently established as he headlined the three-day music festival in 1969 on a dairy farm in the Catskill Mountains when he interpreted “The Star-Spangled Banner” with copious amounts of feedback and distortion, sending a clear message of disapproval for the unraveling war in Vietnam.

youtube

Miles Davis was sufficiently impressed by Hendrix’s appeal that he believed he also could connect with large audiences by crossing the Rubicon into the modern world of electricity.

In 1967, Miles met a young model named Betty Mabry. Nineteen years her senior, he was reinvigorated by her energy, and in turn she introduced him to the music of her friends, Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone. Their relationship moved quickly to marriage and he started shopping for clothes from Benabou and Mimram, frequenting new circles of younger crowds, and replacing his band instruments with the newest technology. The musicians who arrived to record the day after Hendrix’s climactic early morning performance at Woodstock had no idea what Miles had in store for them.

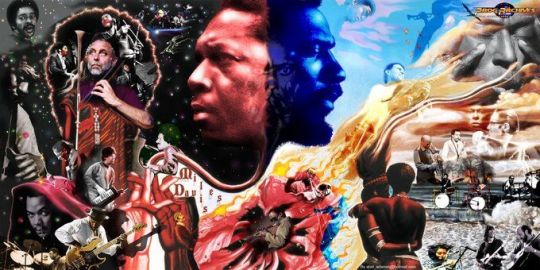

Davis’ sidemen, pianists Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea, had never used electric keyboards before Miles insisted on their inclusion. Also new to the ensemble were musicians who played electric bass and the Hendrix-inspired electric guitar. Miles himself began experimenting with sending his trumpet through a wah pedal, creating the similar sonic effect as Hendrix’s guitar. The collective experimentation that occurred over the next three days known as Bitches Brew (suggested by Mabry) erased his amassed debt with Columbia Records, became the progenitor of jazz-rock fusion, and provided him with the desired entrée to the youth-dominated audience that he so desired to reach. Released in March of 1970, the reaction was profound, even landing him a coveted slot four months later at the Isle of Wight festival in England attended by upwards of 600,000 people—by far the largest audience ever for a Jazz musician.

youtube

Venues normally hosting popular acts such as the Fillmore East and Fillmore West billed Miles opening for Santana, the Grateful Dead, Neil Young and Crazy Horse and even his former sideman, Herbie Hancock and his Headhunters. Miles was once again leading the way into unexplored terrain.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Demarcation Line: Before and After Bitches Brew

On August 19th, 1969, the day after Jimi Hendrix’s legendary performance at Woodstock, Miles Davis entered Columbia Records Studio B and over 3 days recorded what would be named Bitches Brew. These sessions were mostly experimental—merely governed by occasional audio gestures, finger snaps, and a few rehearsed musical signals. The bulk of the music representing the project was spontaneously invented by carefully chosen musicians who were afforded complete liberty to react in the moment. Some participants now admit that there were moments that they were unaware they were even being recorded.

After these three days had ended and the musicians exited the studio, producer Teo Macero waded through all of the amorphous material and demonstrated his own creative virtuosity with a pioneering use of the studio effects and editing techniques by assembling it into the final product. Once released on March 30th, 1970, it spread like wildfire becoming Davis’s first gold record, selling more than half a million copies.

But this financial success often is used to upstage the Pandora’s Box that it opened. From the vantage point of fifty years later, we can plainly see the demarcation line that is represented by this bold project. On one side are those who contend that progress must be embraced—technological advances allow vocabulary to expand, but at what cost? Does progress also mean that perhaps that which is then rendered obsolete ought to be discarded from conversation altogether? What of those who prefer to strive for preservation and precise, authentic emulation of past masters, do they deserve scorn for defending what may be outside of conventional definitions of their craft?

youtube

This is the vigorous debate that continues to take place evidenced by the spirited conversation in 2009 by Davis sideman James Mtume and critic Stanley Crouch in a criticism of Ken Burns’s 2000 documentary series, Jazz (accused of giving post-1959 developments short shrift in favor of detailing the end of Louis Armstrong’s and Duke Ellington’s lives), and even the separation of the music into two separate channels on satellite radio: Real Jazz (and doesn’t that moniker clearly expose the controversy?) vs. Watercolors (a channel featuring music given the pejorative label, Smooth Jazz).

Fortunately for Miles, unlike his fallen peers, he lived long beyond 1970 and provided his own commentary on the events of this revolutionary time in cultural history. Embellished with a tone of narcissistic self-importance, Davis, in his 1990 autobiography appropriately titled Miles, The Autobiography, is not shy about details of his life, both laudable and reprehensible.

He adamantly defends his race and his freedom at any cost, and enthusiastically acknowledges those figures enduring similar struggle without compromise of their integrity. He was born in 1924 and raised in East St. Louis as Miles Dewey Davis III, son of Miles Dewey Davis, Jr., a respected dentist who raised his son to view the world with Marcus Garvey–like suspicion.

Dr. Davis would forever support his second of three children as his son ventured to New York to enroll then quit Juilliard School of Music to pursue an insecure gigging career with Bebop groups, acquire a debilitating heroin habit, and even endure the misadventures with women—Davis (the son) was already responsible for two children who, unlike their father, were never financially supported even after his successful life ended in 1991.

Miles describes the dynamic of the mid-1950s Civil Rights Era as a time that he also was finding his stride and becoming recognized along with others in his generation:

“When this group was getting all this critical acclaim, it seemed that there was a new mood coming into the country; a new feeling was growing among people, black and white. Martin Luther King was leading that bus boycott down in Montgomery, Alabama, and all the black people were supporting him. Marian Anderson became the first black person to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. Arthur Mitchell became the first black to dance with a major white dance company, the New York City Ballet. Marlon Brando and James Dean were the new movie stars and they had this rebellious young image of the “angry young man” going for them. Rebel Without a Cause was a big movie then. Black and white people were starting to get together and in the music world Uncle Tom images were on their way out. All of a sudden, everybody seemed to want anger, coolness, hipness, and real clean, mean sophistication. Now the “rebel” was in and with me being one at that time, I guess that helped make me a media star. Not to mention that I was young and good looking and dressed well too.” (Davis, 197-198)

youtube

The group that was drawing celebrities such as Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Marlon Brando was his first remarkable Quintet featuring the tenor saxophonist John Coltrane. This group, just three years following King’s Montgomery Bus Boycott, recorded the album Kind of Blue, a masterpiece remaining the most important Jazz recording in history. This project was among the first to explore Modal composition: the idea of improvising melody above an accompaniment of a static harmonic foundation. The compositional approach was introduced to Davis and codified by theoretician George Russell in his Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization in 1953. When turntablism emerged in the 1970s as a means of maintaining a static accompaniment to support the emcees and breakdancing, it was merely updating the textures created by Miles Davis and his contemporaries in 1959 whose experiments began paving the way for Hip-Hop.

#miles davis#bitches brew#Teo Macero#jazz history#Hip Hop#Kind of Blue#modal jazz#James Mtume#Stanley Crouch

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

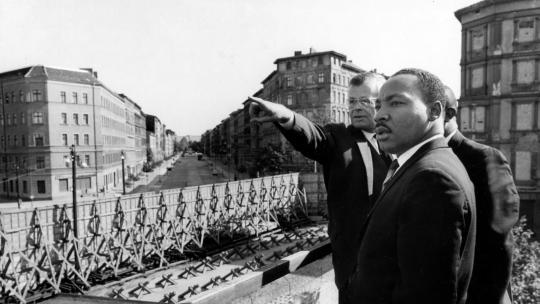

Berlin, 1964: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Miles Davis

To everything (turn, turn, turn) There is a season (turn, turn, turn) And a time to every purpose, under heaven

What was Pete Seeger feeling in 1961 when he was compelled to open the Bible to Ecclesiastes 3: verses 1-8, and compose a melody to these words to give to his publisher to sell? Artists tend to be hyper-sensitive to changing conditions so as to gain more insight about how their body acclimates. Many will accept their instinct for adaptation as a part of survival with minimal notice. Artists, however, endeavor to preserve these human reactions for future study or to facilitate further change. Seeger and the band that would most prominently represent this song, The Byrds, were communicating a change of season—a season of turbulence, agitation, defiance, revolution, introspection and awakening. A season that compels us to look deeply into our inner world, address our grievances, and bring them unabashedly out into the summer sunlight for all to see.

Change is never easy: it invites criticism, resistance, defensiveness, counter-operations. It challenges long-trusting relationships and often results in permanent destabilization. But as we all occupy a living, rotating planet, we are always adapting to each moment. This is what we are celebrating today as we honor the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who was dedicated to a mission of reconciling his moment’s turbulence by exposing it and initiating a grand conversation about it. As perhaps one of the first indicators that the world was moving forward into the Postmodern Age, he uttered the words “I have a dream….” His hopes for a peaceful and unified march into this new season were soon dashed by bullets of those resistors aiming their own passions at those prominent voices of change: JFK, Malcolm X, RFK, MLK Jr., John Lennon, Ronald Reagan, and on, and on….

Although his historic sermon in 1963 was strategically given at the Washington D.C. Mall to reach the heart of the American politic, King also traveled overseas to expose international audiences to the mission.

At the inaugural Berlin Jazz Festival in 1964, he was asked to give the opening address. The festival’s mission: “to document, support, and validate trends in jazz, and to mirror the diversity of creative musical activity” was christened with Dr. King’s words:

“God has wrought many things out of oppression. He has endowed his creatures with the capacity to create—and from this capacity has flowed the sweet songs of sorrow and joy that have allowed man to cope with his environment and many different situations.

Jazz speaks for life. The Blues tell the story of life's difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realize that they take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come out with some new hope or sense of triumph.

This is triumphant music.

Modern jazz has continued in this tradition, singing the songs of a more complicated urban existence. When life itself offers no order and meaning, the musician creates an order and meaning from the sounds of the earth which flow through his instrument.

It is no wonder that so much of the search for identity among American Negroes was championed by Jazz musicians. Long before the modern essayists and scholars wrote of racial identity as a problem for a multiracial world, musicians were returning to their roots to affirm that which was stirring within their souls.

Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down.

And now, Jazz is exported to the world. For in the particular struggle of the Negro in America there is something akin to the universal struggle of modern man. Everybody has the Blues. Everybody longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for faith.

In music, especially this broad category called Jazz, there is a stepping stone towards all of these.” (King, 1964)

The closing act of the 1964 Festival in Berlin was the Miles Davis Quintet, now historically significant as the first recording of his Second Great Quintet with Davis on trumpet, Wayne Shorter on sax, Herbie Hancock, piano, Ron Carter, bass, and Tony Williams on drums. Miles Davis, only Dr. King’s senior by three years, also was in Berlin to communicate a message that the season was changing.

Davis by this point had reached the highest points of financial success for a Bebop artist, but was demonstrating that he had no intent to coast on the achievements of previous projects. His mission, like King’s, John Lennon’s, and others in their generation, would be to adapt to the changing times and continue moving forward. This ensemble, his Second Great Quintet produced a remarkable body of challenging, searching, abstract music through to 1968, that violent moment when peaceful protests turned to militant insistence. True to form, Miles turned also.

youtube

#Miles Davis#Herbie Hancock#Ron Carter#Tony Williams#Wayne Shorter#1964 Berlin Jazz Festival#Jazz History#Martin Luther King#Miles In Berlin#Second Turning#Consciousness Revolution

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jazz in the Postmodern Age

Jazz music is an idiom in which the griot, or storyteller, contextualizes contemporary events with an individualized inflection to connect with their immediate audience. Jazz as a process continued the griotic tradition in America, conventionally understood as emerging from the Mississippi Delta regions, most significantly cosmopolitan New Orleans, and migrating into northern metropolitan areas such as Chicago, Harlem, and St. Louis. Jazz was only the next in a developing language occupying a place in the storytelling continuum which has included Blues, Spirituals, Gospel, Blues before it, and succeeded by Rhythm & Blues, Rock & Roll, Afro-Cuban, Soul, Funk, and currently Hip-Hop.

“Jazz” as a descriptive label was first used to identify the sounds of Lost Generation pioneers such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, providing a distinctive voice to the Prohibition Era speakeasies, and quickly gaining the attention of the next eager cohort who were listening to any and every note these masters presented on the new technology of mass communication, radio.The GI Generation collectivized and commercialized Jazz.

Victorious in WWII, they were encouraged by such notable psychologists as Dr. Spock to allow their postwar children latitude to “discover themselves” in youth and subsequently The Baby Boomers have remained the prophets of the early millennial years. Among the repercussions of this licensed Boomer introspection was a preoccupation with the self that in 1976, journalist Tom Wolfe coined as the “Me” culture.

Concurrent with the post-JFK Consciousness Revolution emerged a philosophical movement that was coined “Postmodernism.” Deconstructionists such as Jacques Derrida became preoccupied with language and semiotics, challenging how perception is communicated, and facilitating a relativism that continues to keep our modern culture in a polarized, chaotic state of existence.

Technological advances as represented by digital instruments and fascination with the synthetic are material representations of our current Postmodern Age.

youtube

By the late 1950s, what was at one time considered “street music” was formally adopted into curricula of higher institution, validating the Jazz process as deserving of formal study and appreciation. This inclusion was just another event that elevated the urban community in the decades following the 1920s Renaissance. It was the Boomers who were the recipients of these initial academic adoptions of urban culture, and by the late 1960s the zeitgeist was characterized by that which stimulated inner-directed searching: free speech, LSD, free love, cults, aerobics, Moonies, etc. The decolonization of the British Empire enabled the global influence of Eastern Transcendentalism, and by the mid-1960s, a new Awakening was driving society.

Martin Luther King, Jr. emulated approaches practiced by Gandhi, composers Terry Riley, Philip Glass, and Steve Reich introduced music in drone-like fashion called Minimalism, and Miles Davis moved into a phase of aleatoric, collective improvisation first liberating harmony, then form, and finally adopting new technology to move Jazz convincingly into the Postmodern Age.

Inspired by his conversations with George Russell, who proposed the Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization (1953), Davis assembled a legendary sextet that recorded the landmark album Kind of Blue in 1959, utilizing Russell’s Modal theories by reducing composition to a scales (horizontal melodies) as opposed to chords (vertical approaches to melody), and creating static accompaniments as the foundation for improvisation.

youtube

Davis would follow this ensemble with his second important group that experimented with compositions such as “Nefertiti,” based on a looping melody rather than a formalized structure that was the musical equivalent to M.C. Escher’s tessellations and Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup paintings.

youtube

And then in the late 1960s, a thoroughly postmodern mindset influenced Davis to present collective improvisation with electric instruments, thus launching the Jazz-Rock Fusion genre. His projects, Bitches Brew, A Tribute To Jack Johnson, and On The Corner with their James Brown-like static grooves both provoked criticism from traditionalists, and provided the model for his protégés to create in an idiom that spoke to and for the younger Boomer audience. The door had been opened for the entrance of Hip-Hop.

youtube

#Miles Davis#m.c. escher#andywarhol#postmodernism#ModalJazz#George Russell#kind of blue#Jacques Derrida#mlkjr#Bitches Brew#Jazz

1 note

·

View note

Text

Something Cool

Margy Frake is “restless as a willow in a wind storm” as she packs for the Iowa State Fair, believing that it will provide her with a break from the mundane life on the farm in the 1945 film, State Fair, scored by Rogers and Hammerstein. Artists have the innate ability to translate the mood of their time into masterworks resonating within and beyond the moment of artful creation. Certainly the end of this critical war and crippling Depression thawed the icy mood and dawned to an early morning, cool, spring-like optimism. Rogers’ and Hammerstein’s keen timing was reinforced by the Academy Award for Best Original Song as “It Might as Well Be Spring” was added to the Great American Songbook.

youtube

Hollywood and the West Coast attracted the attention of the world at war’s end. The energy required to attain victory would be invested in migrating to a more relaxed environment much like the vacation departure following an arduous period of work. Capitol Records was founded in 1942, and the circular tower known as “The House That Nat Built” would be the epicenter of the Cool movement. Nat Cole, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis, Jr., Peggy Lee, Dean Martin, and Harry James were all contributors to a silky smooth, breezy, crooning, sophisticated, understated, back-phrasing style of delivery.

It was here also the Stan Kenton’s Orchestra backed the youthful, but very sensual vocalist, June Christy.

Her rendering of Billy Barnes’ song captures this mood: “Something Cool, I’d like to order something cool…My! It’s simply nice to sit and rest awhile… A cigarette? Well I don’t smoke them as a rule, but I’ll have one, It might be fun with something cool.”

youtube

Upon completing service in the war, pianist/composer Gil Evans brought his West Coast experience with the Claude Thornhill Orchestra to New York, making a beeline for the progenitors of Bebop. His cramped rented basement apartment at 14 West 55thStreet became the meeting ground for musicians hanging around the action on 52ndStreet. It was here that discussions on music by visionaries such as George Russell, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Lee Konitz, John Lewis, and Gerry Mulligan.

These ongoing gatherings sparked creative energy resulting in the first of several remarkable collaborations between Evans and Davis, as well as the others in this group.

Their first recording project occurred at Capital Records in 1949 and was given the pitch-perfect title of Birth of the Cool.