Text

"I Love This Little Life We Built"

I find the torchlit ending of the Epilogue to be the best among them, even beyond the gorgeous Danse Macabre, because it is the truest to the twin natures of you, it is the ending that both of you would choose for the sake of the other and yet it is the ending in which nobody wins. Though perhaps the Long Quiet in a diegetic manner does not understand that the Princess is yielded to the Shifting Mound every time she feels the starlight of the world enter her eyes, we the player (if they were indeed to get the torchlit ending) are, crucially, all too aware of that, and I would assume that is the predominant reason that we would choose the "stay with her" option rather than the "leave with her" one. With regards to the Deconstructed Damsel, it is a different story, but to some extent the same logic of "protecting her from those all-powerful hands" remains a priority.

So though you may not leave together, lest she be taken and the love story be destroyed and begin anew, you can at least remain together. But the Princess wants to leave, she wants to see the world and, to some extent, be wrapped in those cold arms, she wants to abandon her vessel and join the conglomeration. She wants to commit suicide. But you prevent her, and, because this Princess is pliable to her core, she reticently accepts that. But she is unhappy with this. She does not understand that she will die, and the Long Quiet does not have the words and knowledge in order to explain it to her. And so she is unhappy, she does not understand why she cannot leave and she does not understand why she must stay trapped within her hell. Why she must live. And, of course, the Smitten cannot bear that, everything goes dark, and we die.

We appear in a place where she has, in part, come to terms with the fact that she is unhappy, that she will forever be unhappy, because just as we are willing to bear the heartbreak for our partner, so too is she. And so she smiles with a melancholy fondness and allows us to participate in this life that we put together, she, though we have denied her for what seems like no reason at all, continues to love us. She entertains us, she feeds us, she engages in conversation with us, she portrays herself as happy for our sake. And we too, we smile all the while as the food grows rancid, as the games grow boring, and as apathy eats us alive. Because to leave with the Princess is the death and rebirth of her, and we cannot allow that to happen. And Smitten, the same one to kill us in the beginning, almost begins to understand this. He takes care of the Princess and traps her both, just as we do, and she does not understand why, only that he genuinely does care for her yet still hurts her in this way.

And finally, rather than making the other unhappy, we each sit in our own unhappiness forever, each one of us insufficient in totality, yet utterly devoted to the other. She cannot understand us, and we cannot understand the pain that she is going through. But we grin and bear it, because an eternity of this is still better than death for her. We have become the Narrator, and she has too, just as the Danse Macabre is the ultimate rejection of the Narrator. We love her, she loves us, and because of that, we damn ourselves to an eternity of nothing, each of us secure in the knowledge that the other one loves us, and that we love them, and we waste away in decay.

And in the end, the hands take her nonetheless, all our agony so vain.

#slay the princess#black tabby games#stp princess#the princess#happily ever after#damsel#the damsel#it's like the gift of the magi#except tragic instead of comic#the love is there#it is real#but maybe nothing else is

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prologue to Osamu Dazai's "No Longer Human"

I have seen three pictures of the man.

The first, a childhood photograph you might call it, shows him about the age of ten, a small boy surrounded by a great many women (his sisters and cousins, no doubt). He stands in brightly checked trousers by the edge of a garden pond. His head is tilted at an angle thirty degrees to the left, and his teeth are bared in an ugly smirk. Ugly? You may well question the word, for insensitive people (that is to say, those indifferent to matters of beauty and ugliness) would mechanically comment with a bland, vacuous expression, “What an adorable little boy!” It is quite true that what commonly passes for “adorable” is sufficiently present in this child’s face to give a modicum of meaning to the compliment. But I think that anyone who had ever been subjected to the least exposure to what makes for beauty would most likely toss the photograph to one side with the gesture employed in brushing away a caterpillar, and mutter in profound revulsion, “What a dreadful child!”

Indeed, the more carefully you examine the child’s smiling face the more you feel an indescribable, unspeakable horror creeping over you. You see that it is actually not a smiling face at all. The boy has not a suggestion of a smile. Look at his tightly clenched fists if you want proof. No human being can smile with his fists doubled like that. It is a monkey. A grinning monkey-face. The smile is nothing more than a puckering of ugly wrinkles. The photograph reproduces an expression so freakish, and at the same time so unclean and even nauseating, that your impulse is to say, “What a wizened, hideous little boy!” I have never seen a child with such an unaccountable expression.

The face in the second snapshot is startlingly unlike the first. He is a student in this picture, although it is not clear whether it dates from high school or college days. At any rate, he is now extraordinarily handsome. But here again the face fails inexplicably to give the impression of belonging to a living human being. He wears a student’s uniform and a white handkerchief peeps from his breast pocket. He sits in a wicker chair with his legs crossed. Again he is smiling, this time not the wizened monkey’s grin but a rather adroit little smile. And yet somehow it is not the smile of a human being: it utterly lacks substance, all of what we might call the “heaviness of blood” or perhaps the “solidity of human life”—it has not even a bird’s weight. It is merely a blank sheet of paper, light as a feather, and it is smiling. The picture produces, in short, a sensation of complete artificiality. Pretense, insincerity, fatuousness— none of these words quite covers it. And of course you couldn’t dismiss it simply as dandyism. In fact, if you look carefully you will begin to feel that there is something strangely unpleasant about this handsome young man. I have never seen a young man whose good looks were so baffling.

The remaining photograph is the most monstrous of all. It is quite impossible in this one even to guess the age, though the hair seems to be streaked somewhat with grey. It was taken in a corner of an extraordinarily dirty room (you can plainly see in the picture how the wall is crumbling in three places). His small hands are held in front of him. This time he is not smiling. There is no expression whatsoever. The picture has a genuinely chilling, foreboding quality, as if it caught him in the act of dying as he sat before the camera, his hands held over a heater. That is not the only shocking thing about it. The head is shown quite large, and you can examine the features in detail: the forehead is average, the wrinkles on the forehead average, the eyebrows also average, the eyes, the nose, the mouth, the chin... the face is not merely devoid of expression, it fails even to leave a memory. It has no individuality. I have only to shut my eyes after looking at it to forget the face. I can remember the wall of the room, the little heater, but all impression of the face of the principal figure in the room is blotted out; I am unable to recall a single thing about it. This face could never be made the subject of a painting, not even of a cartoon. I open my eyes. There is not even the pleasure of recollecting: of course, that’s the kind of face it was! To state the matter in the most extreme terms: when I open my eyes and look at the photograph a second time I still cannot remember it. Besides, it rubs against me the wrong way, and makes me feel so uncomfortable that in the end I want to avert my eyes.

I think that even a death mask would hold more of an expression, leave more of a memory. That effigy suggests nothing so much as a human body to which a horse’s head has been attached. Something ineffable makes the beholder shudder in distaste. I have never seen such an inscrutable face on a man.

#obviously this isn't mine#but for the sake of having it somewhere it can be accessed#surprisingly self-contained for a prologue#but it still is far more effective knowing the rest of the story#i headcanon that Yozo rather than the Narrator of the epilogue is the one to remark upon the photos

0 notes

Text

The Lee Shore

The quiet embrace of land calls like a siren, and one ship, weary and hungry from years on the open sea, is primed to hear its call. It just needs a little bit more time to find a port, just a little bit more time at sea to ensure its safe landing. Yet its mastheads don’t quite stand with the same vivacity they initially carried themselves with, and its will eventually buckles. Left without wax for its ears, the ship pushes towards the land, nominally its only source of respite, its crew shaking with a growing horror that refuses to be abated. Not unlike the exhausted hands on deck, the twins Scylla and Charybdis hunger; they have hungered for millennia, and it’s safe to say that their bottomless stomachs may well never be full. The very concept of free will is stripped away from the lowliest ship hand and the captain alike as the galleon achingly, forcefully hobbles its way towards its desolation. Eurus himself takes initiative in marching it to its execution, pushing it against the wall for his never-tiring firing squad to take full advantage of. Such is the lee shore. In the chapter of the same name, one Bulkington, a ship’s pilot, found it within himself to reject those winds, and in that, Melville’s Ishmael, possessed for a moment of the spirit of Virgil or Homer, eulogises him and all he represented; it would be the only lasting record in memory of him.

He appears for perhaps three pages in the novel, in all but this epitaph a minor character, forgotten by the world. The irony is that within the metanarrative, until looking at this eternal tombstone of a chapter, neither would we remember him. Quoted as a man for whom “[t]he land seemed scorching to his feet”, Bulkington was someone who dared to not only reject the grand winds that would push him unwillingly towards land, but someone who dared to reclaim his own destiny from the hostile elements that would come before him. One who found refuge in the greatest danger he could find, whose courage would put a lion to shame. The final thought we ever hear of him is the concluding paragraph of the only page he is remembered in, and some of the greatest prose to grace the English language: “But as in landlessness alone resides the highest truth, shoreless, indefinite as God --- so better is it to perish in that howling infinite than be ingloriously dashed upon the lee, even if that were safety! For worm-like, then, oh! who would craven crawl to land! Terrors of the terrible! is all this agony so vain? Take heart, take heart, O Bulkington! Bear thee grimly, demigod! Up from the spray of thy ocean-perishing --- straight up, leaps thy apotheosis!” As I’m sure one can guess, there is a certain connotation to that final word that, for all the tenacity of a bulldog, I cannot completely extricate.

But in that moment, the Eureka escaped from my lips, and I thought to myself, why must one necessarily oppose the connection of the two concepts, particularly when it is inevitable? Why can’t I simply unify the ideas? Is there anything within the concept of art that irrationally linked concepts cannot for whatever reason be rationally linked? In short, I found I was being shortsighted. And, as such, I shall now attempt to explain why, exactly, the themes of both this paragraph and the other Apotheosis, aren’t fully extricable. First of all, I really must apply a disclaimer to this. Doing this properly would in fact require me to elucidate exactly what both the Apotheosis and the Melville passage signify. I’d like to emphasise that this is before the Pristine Cut releases, and as such, I lack the deeper knowledge from Apotheosis that comes from, well, playing Apotheosis in full, but I have enough faith in Black Tabby to believe that the majority of the existing themes are already present within, and will simply be expanded upon and properly developed. That is, I am taking the art as is, and trying to take from that the basic themes that we have now. With regards to the paragraph from Moby-Dick, in my professional opinion, it should be more or less safe from revision, considering it is dated from a hundred and seventy-five years ago, in addition to it being nothing more than a paragraph.

Furthermore, before all else is put forth, it is important to make note of the fact that within Ishmael’s eulogy, Bulkington is not a person. Bulkington the character is only the inspiration for Ishmael’s musings, and could be replaced with anyone else for the same result. He has not played any significant role in the story; he is completely static, and he was never even mentioned by the narration except insofar as to paint a picture of the regulars at an inn. Bulkington the character does not matter. Taking him, however, as an ideal shows a much fuller picture of what Ishmael is trying to say. Bulkington does not need to be a character, but what he does need to be is the conduit for that striking prose, for the triumphant cry against the sea. That is to say, I shall not be minutely analysing Bulkington, nor his four lines of dialogue.

To be able to compare the themes of the End of Everything and the obituary to the End of But One Man requires, definitionally, those themes to be made known. Throughout the final paragraph of Bulkington's epitaph, the primary theme is made quite clear. Despite the battery of waves, the lack of safety, the very ground constantly shifting beneath one’s feet, it is of far greater virtue to die at sea than to perish while cringing towards the land that initially promises its protection. “Lee”, before it was used as a term for sailing, meant “safety”, yet the lee shore promises not safety, but destruction wrapped in the guile of innocence. As it gently pushes a sailor towards the land, his just home, it simultaneously begs him to be dashed upon the rocks of that land. And if he does listen to those sweet lips calling him home, then he shall verily “come home,” and all the seafaring, all the agony was wrapped in the pallor of futility. To conquer the greatest of the seas, to see Tahiti, Cape Horn, the Maldives, to view the truly universal continent, and yet be brought down like Goliath himself by the rocks of the land. They outstretch their hand to hold him, to finally bring him rest. And, at last, they succeed. Such is the lee shore.

Yet Ishmael notes something else, something, dare I say, far more interesting. It is also in the rejection of the lee wind that mankind truly ascends. In nothing more than simply remaining at sea, mankind reaches its towering heights. For vice is meaningless without virtue, no? He who refuses to let himself be compromised by the false cry of home, well, he has then made himself greater than Hercules and all his labours. For in that rejection of the call of safety, mankind has found its freedom. And the greatest thing mankind can do, its highest calling, is to save its life, even if that requires its own destruction. In happily going to the ballroom for the Danse Macabre, the Grim Reaper tires. Ishmael posthumously cries that the pilot should “take heart”, because just as the heart was the key to bodily life, so too has the heart, according to the ancients, a deep and sincere reservoir of what may be more important – moral strength. And it is through that strength that man finds it within himself to fend off old Thanatos’s scythe with the rudder of his innate purpose.

That may seem rather confusing; after all, Ishmael himself, within that quote, directly romanticises death at sea. Clearly this is not about life and death – it is simply death. Yet, in my humble opinion, I would declare a key difference. To perish in the ocean is the choice taken. It is the adeo, a Latin word that carries the various and eclectic meanings of “goodbye”, of “fulfillment”, and of “action”, all at once; one's final decision. It is desire fulfilled, not simply living in denial about the inevitable, as one attempts to grasp for a chance that will never rear its head. If death is then hanging its gloomy countenance over every outcome regardless of action, then the man who lives as he was, the man who carries on with what he has determined he shall do, he carries far more valour with him than he who futilely runs screaming, never allowing himself to write his own future. A decidedly unromantic view, one could argue, yet one with a strange quixotic passion to it yet; a contradiction in terms, even. Yet, in the end, those are even the words of Christ: whosoever shall lose his life, the same shall save it. The very struggle with death, eternal for man, has become paradox.

And this philosophy of his is itself reflected in Ishmael’s actions later on in the book. He, in no less than the first chapter, is indicated to have an unhealthy morbidity about him – marching in funeral processions in which he has no connection and staying for an abnormal amount of time within coffin warehouses. And in the end, it comes to pass that even the ship he boards and the beast he attempts to slay are hearses of their own (in the plaintext, no less), sepulchres that stand whitewashed in two quite markedly different ways. He is no stranger to looking the angel of death square in the eye. And at the end, it is by clinging to a coffin that salvation finally comes to him. It is in that unashamed embrace of his mortality that he is able to find his way out of the waves. Melville was no Poe. He did not dive into the morbid purely for the sake of itself. But rather, it was the opinion of him that, in contrast, courage was, just for the sake of it being courage, virtuous. And the slow, futile crawl towards the shore, towards “salvation”, only to fall nonetheless, was for those of whom a timorous countenance was the only one they had learned. And in that ocean-perishing, in that death so completely removed from the desperate wish for life, ears far too stuffed with the wax of fulfillment to hear the growing chorus of the shore’s desperate cries, desperate attempts to claim one’s soul; up from that leaps thy apotheosis!

The Apotheosis carries more or less that same message, but in a very different light. Her context must be taken into consideration if anything is to be said about her, which in turn requires a brief analysis of the Tower. The Tower arises not only out of the failure of her (presumptive) Slayer, but his complete and total submission upon that failure. And in that, she becomes dominance incarnate, she ascends to divinity. And at that point, what is the Slayer to her but whatsoever she wills? There is contained within her purifying light no room for the blemish of disobedience. She offers the Slayer a spot at her side, willing to put aside his past transgressions for the sake of the future. Yet in the face of her magnanimity, he still refuses.

The Slayer refuses the Princess’s offer, his place forgotten — or perhaps simply never learned. She is willing to forgive his sins, as he has awakened her to her true place, that celestial throne. She speaks, her voice gently booming, love infused in every word, and tells him of all they could accomplish together, she offers the life that only she can bring. Yet in the face of her magnanimity, he still refuses. She is taken aback, yet understands. She understands everything. He needs to be able to process everything, like a young child who is confused on what exactly he did wrong. She has time, all the time in the world. For she is the world. Nothing happens that does not happen without her saying it is so, and nothing does not happen should she say it does. She can reform the world in the Imago Turri, and verily, she shall. She loves the lost little bird, for a reason that she cannot fully express. She finds it within herself to not only forgive his mistake earlier, but to forget it altogether. She is merciful, she is benevolent, she is loving. And through that love, she decides that he has come to a decision.

And so he utters that decision. And something odd occurs. In the face of her magnanimity, he still refuses. The Princess is disappointed, though she is careful not to break her imperious, royal smile. After all this time, he still doesn’t understand who he is? What he is? And so, though it breaks her heart, she does what she must. She offers him a choice, to either embrace her or to embrace the next iteration of their saga, one in which she shall surely open his eyes, to open the eyes of that poor little bird, if only he would accept it. She hopes deep within her heart that he does not choose the latter; why can her open arms never be embraced? In the last life, her foot brought down the Slayer like it was iron: strength that refuses to yield — why is he so blind to her head of gold, potential made into reality, value that cannot fade? Her silver shoulders that, despite the sickly air of the cabin being so corrosive, refuse to tarnish? Her belly of bronze, sturdy as steel and loving as Venus, here to protect him?

Yet in the face of her magnanimity, he still refuses, after everything, and her heart aches as she realises what she must do. The Slayer has forced her hand. And now she will force his. Such is the benevolence of her that she not only shall forgive him his trespasses, but shall even deliver him from the evil one, a dead echo throughout his skull, long forgotten by anyone, yet a plague, a parasite to his form nonetheless. This is something that is neither her nor him, and as such does nothing more than futilely stand in the way of the victory of the god and her herald. The pitiful echo is gone, and they shall begin their dance anew. He will understand now, there is no question of that. And that is all that matters.

The Slayer refuses the Princess’s offer, his place forgotten — or perhaps simply never learned. And so he fights, he marches onwards in his futile drive to freedom. He refuses to turn his eyes to the lee shore where safety and home lie, and stays within the tempestuous, oceanic struggle with a force far greater than him or anything else. This fight was never between equals, yet still the Slayer maintains his assault, not so much because he has a moral imperative to keep the world from ending, but because he shall not be beaten down such that he cannot bring himself back to his feet. He could, perhaps, yield control of the situation — that’s manageable, if not ideal; but he cannot yield his nature. Yet, at some point, he does. He feels his very soul crying out as his willpower becomes moot, shaking with the inevitability and the horror of it, a fight in vain that the Slayer refused to abstain from. It has given a magnificent swan song, yet the hunter he once thought he could win against has wrung the angelic trumpet out of the bird’s chest. He takes his blade, fighting with his own body, delaying the inevitable.

There is a part of him who wants to lie down, who wants to die, who wants to stake the Slayer’s life upon the ascendance of the only thing that can ensure safety. This part has been a thorn in the Slayer’s side ever since it made itself known. He is sick of it. He refuses to give any oxygen to it. He ignores it. It does not leave. He fights with it, he tells himself that he doesn’t want to give in. It does not leave. He gathers together all of his volition and he wills himself to simply reject this side to him, like he always has. Like he knows he can. But that broken little part of his psyche? He does not leave. He refuses to simply be stamped out. And as he remains, his voice begins to ring with the almost blinding clarity of knowing exactly what he is. But his value becoming as clear as the Princess’s light means nothing. Alongside the Princess, he can do anything. He easily overwhelms any opposition, and with a force unlike anything the Slayer has seen before, that puny little voice steels himself and acts. And with that imperceptible tremor, the mouse has roared, and the rocks upon the lee shore end the day speckled with a blood that the waves that crash against it can’t quite reach.

And he wakes up once more, the situation hanging like a heavy radiance over his head, a burden that his shoulders cannot bear. Yet he cannot set his burden down. Not yet. The world is apocalyptic and gorgeous and broken and complete all at once; even the trees, desolate and dead as they may be, herald with an Olympian majesty the cella of the cabin, proclaiming the divine majesty of who the Princess is. He at once realises that this is final; that this is going to be the climax of the dance of the god and her singular subject. There is an echo within him — it, unlike in lives past, declares its full and undying support behind him. There will be no treachery, there will be no petulance; the stakes are far too high for something as empty as that to be brooked. He takes a solitary step, not in any direction in particular, and in that moment the height of anything that has existed or ever will exist is reached. The Princess reveals Herself, yet at the same time remains unrevealed. There is no way to describe Her, because there is nothing other than Her. She stands, and with that the heavens bend themselves around her, a thousand lights, a thousand eyes, and a thousand suns in a halo around her beatific head. There is nothing that escapes her gravity, nothing able to stand its ground in the face of who She is. She is the absolute, the end of everything. The beginning of something new, something far grander than could be imagined.

She is so much more than him. And Her arms are happily opened to his embrace. The Long Quiet lets himself be pulled into the zenith of existence. He has opened his soul to Her, he has opened his mind to Her, he has even opened his carotid unto her, a sacrifice poured upon the marble floor and the symbol that he has repented of his transgressions. It is so easy to simply be loved. There is no virtue greater than love, there is no vice greater than abandoning that love. She loves him, and he loves her. What would he be if he denied that? She smiles at him, as if to say that tonight, he shall be with her in paradise. It has always been an option. This was always an option. He may have lost that paradise, yet alongside her, “the World was all before them, where to choose their place of rest, with Her as their guide. They, hand in hand, with wandering steps, and slow, through this world, they could take their solitary way.” He has embraced oblivion, yet while The Long Quiet remains in the unshakeable grasp of Her, the word has no meaning. She smiles, and reaches to take his hand. The lee wind blows him to shore, and he happily complies. He happily takes the safety offered to him. He is happy, and, just perhaps, that happiness is far more virtuous than any futile resistance could be. She is absolute, the end of everything. The beginning of something new, something far greater than could be imagined.

Yet despite who She is, he still fights. He deigns to perish in this howling infinite — if he must die for the sake of his soul, so be it. The Hero finds the blade, buried deep within one of many monuments to her greatness, and lets himself be swept within her gravity. He is facing the most awesome being to ever walk upon this earth, yet he still fights, for there is no other option. As the world breaks, the one thing that shall not is the Hero’s resolve; the mistake shall not be repeated. The world will end if he does not find victory, so then let him be damned if he doesn’t at least seek it. The knife feels perfectly balanced in his hands, and, shockingly, as he leaps towards Her, he finds within himself a brief moment of exhilaration. He feels that, despite everything, he can still do this. He is the one who has found the highest truth, indefinite as the Princess herself. He will end this. He will Slay the Princess, this false idol that purports safety yet is incapable of living in a world where not all is bent to Her will. The Hero is just the symbol of that, he is just the one who refuses to bend. The Princess turns to him, as he still resists with all the effort he can muster. And upon Her face is plastered a look that the Hero cannot quite understand. She is delighted. After all this time trying to tear his resolve down, to force him to see her point of view, She is glad that he chooses to fight. She faces him with the same love She had when he first entered the basement, all pain between them forgotten by Her. He has borne the suffering grimly, and with that, he, up from the spray of his perishing, found the love that was so much foolishness, a veritable stumbling block only a few seconds ago. Straight up, he leaps to his Apotheosis.

It is not entirely difficult to see the comparisons between the chapters. There exists within them the ideals of seizing your soul even at the expense of the body, most clearly seen in the end of the Tower. There is, curiously enough, a seeming innocence of the shore within the passage of Moby-Dick. It does not intend for there to be so much pain as a result of its existence, it simply welcomes the ship to itself, holding the anxious family members of the crew up such that they can see their returning loves. It provides respite, it provides warmth and resupply and new people to talk to and new cultures to understand. It simply wants the best for the ship that chances upon it, and with that, there is continuously a shout of joy arising from the crew as they see the land they have left for so unbearably long. There is a love present there. Yet as the lee wind pushes, as the confines of the construct begin to demand its toll, the land warps into a demonic entity, one that claims the souls of far too many innocent men. It does not necessarily want to bring harm, but it does anyway, because what else ought it do? As wood splinters all around it and bodies begin to pile up, the land cannot move. It must simply remain in place, horrified, as these externalities force so much desolation upon the ship that once loved it so. But whatever horrors it may have seen, it shall take heart, and see them through. Because there will always be a ship that the land can help, that the shore can do its just penance for. It never meant to bring harm, not to the ships that love it, and that the land loves in turn.

This is a love story.

#slay the princess#black tabby games#the princess#the apotheosis#apotheosis#moby dick#herman melville#this is probably my finest work thus far#i dont think it my “greatest”#but certainly my best#both these passages are in the superposition of being both incredibly christian and incredibly blasphemous#its oddly compelling#in any case#points if you can name where the quote from the third to last paragraph is from#i telegraphed it pretty heavily#but still#covering my plagiarism bases

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

After thinking about it for like, three hours straight, it is official. Ms. @queenlucythevaliant has in fact convinced me that Brontë's Heathcliff is the initial Earnshaw’s bastard son, and that’s even undoing the massive damage Nicola Edwards did to my perception of that theory. Ms. Lucy has a wonderful analysis of why that is (Like drinking light — In Defense of Wuthering Heights (tumblr.com)), but to simply and abominably briefly go over it, it focuses on one major point. That all of what would come in the book would be the sin of the father being visited upon the son, and how that failure as a patriarch, a husband, and a father would set the seeds for the horrors that would eventually come. The genius of the book comes in the third act, but you really ought to read her analysis, it is far better than I could do. But there is one character, one that I certainly should not love as much as I do, that I feel does not get their due in her excellent analysis, and that is Hindley Earnshaw, the upcoming master of Wuthering Heights. Please forgive in advance my appalling characterization.

Hindley, throughout the book, is objectively a terrible human being. He is an abusive patriarch, one who in a large part forms the trauma that drives Heathcliff and Cathy together, and messes Heathcliff up so badly. He, among other things, tries to murder Heathcliff (multiple times), starves both Heathcliff and Cathy, loses the entirety of Wuthering Heights to gambling debts, and drops his infant son over the bannister of a staircase. He is by no means a sympathetic character, at most a pathetic one, someone that is pitiable but not much more. Yet, to me, he has always been oddly compelling, and I think that the “Heathcliff Earnshaw” theory really adds to his character.

Much has been made of the fact that when Heathcliff first arrives at the manor within the coat of Master Earnshaw, he replaces Cathy’s horsewhip, in turn becoming it, eventually. Heathcliff becomes her tool to seek revenge for both his own sake and for hers, to be driven to any goal she should like. Yet for Hindley, what is he but the instrument of the devil, the fiddle? He arrives, dark and strangely off-putting, and in turn (implicitly) usurps Hindley as the favorite son. Heathcliff, throughout the book, could perhaps be summed up in one word — ressentiment. The inferiority complex that turns into frustration, yet the aggrieved oft cannot face the purveyor of it. Yet, at the beginning, Hindley is the one who bestows upon both himself and (eventually) Heathcliff the phenomenon. He is the heir, yet the second favorite. He does not have his father’s love in the same way that Heathcliff does, a new member of the house picked up off the very streets. And he cannot understand why Heathcliff would be the one to obtain his father’s love. As much as one can enjoy being loved, it hurts to know that you are only the next best thing. It hurts playing the second fiddle.

It’s also important to recognize the age gap dynamics at play here. Heathcliff and Cathy are roughly the same age, and so they go and play together, they enjoy their life as children are wont to do with their contemporaries. Hindley is declared to be at least a good bit older than them, and the text says that as he was growing up, he had for his playmate Nelly Dean, who, from the very nature of the relationship, was never on equal footing. She could not engage in the same freedom that Heathcliff and Cathy had, she was simply a servant and a child, doing her job to the very best, and regardless of how much she may or may not have enjoyed Hindley’s company, that thread would underlie everything they did together.

And he takes it out on Heathcliff. He is the usurper, he is happy and has his father’s real love. He has a true friendship, one that doesn’t exist just because his father is paying for it. Hindley is full of wrath, and Heathcliff quickly learns that Hindley’s kindled fury burns as it fills the air around him, blazing as it fills the room with smoke, obscuring the original purpose of that anger. And that anger is all for naught, for as Hindley torments Heathcliff, his father looks on him with anger, and perhaps worse, disappointment. Multiple times, the old Master Earnshaw starts to try to beat Hindley with his stick, and every time lamenting that he could not. When the decision finally comes to send Hindley to college, out of Earnshaw’s sight, the man says that he doubts Hindley could thrive anywhere. Hindley, in trying to cope with being the second favorite, dooms his place as the heir that shall never have his father’s approval, and at his father's death, he wasn’t even at home to see it. And the worst of it is that it is only because Hindley leaves that Heathcliff and Cathy are able to become close, to become the people so inseparably tied that they would almost bring down two families.

After he ascends to the role of patriarch, he becomes even worse, particularly upon seeing his wife’s dislike of Heathcliff. Beatings and fastings were commonplace. This was the height of his cruelty. Nelly Dean, his own servant and best friend, questioned his mistreatment of them. And after his wife died, things went downhill quickly. He had nobody who loved him anymore except the old, loquacious, contemptible butler. His father hated him to his death, his wife was gone, no siblings anymore, and his sole true friend a turncoat. He had a son, but all that did was remind him of his lost love. He took to drink and gambling, trying to forget that love was ever a thing. And Nelly Dean watched as her playmate from years past threw his own life away. He had no life anymore, he had squandered anything that could have been love. But really, it was only natural.

What other option did he have?

#honestly pretty low effort compared to most of my stuff#hindley earnshaw#heathcliff#catherine earnshaw#really not a tragic character#but i'll make him one dangit#it hurts being the second favorite#wuthering heights

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

If I had a nickel for every time I fell in love with a tragic love story that takes note of ethnic tensions and follows a protagonist (fueled by ressentiment) with a psuedo-incestuous relationship with a Catherine, I'd have two nickels, which isn't a lot, but it's weird that it happened twice.

#wuthering heights#catherine earnshaw#heathcliff#a view from the bridge#eddie carbone#literature#these “heroes” are so messed up and so human#my heart goes out to them

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a good bit more low-effort than most of my stuff, but I cannot hold it in. The heart attack I had when I realized the primary lancer of Moby-Dick was also the primary harpooneer was something I could not keep to myself.

#moby dick#herman melville#classic literature#if this was clearly apparent to anyone else#i am very sorry#but I have no idea if it was intentional or not#knowing melville's prose#probably the former

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

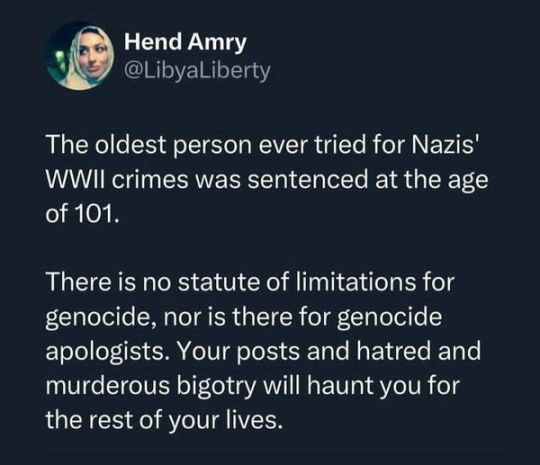

First of all, you are completely right. There is no statute of limitations for genocide apology. There's no statute of limitations for genocide apology because it's no crime. And the reason that statutes of limitations exist in the first place is because punitive justice is (rightfully) not the way we run our system. If someone is 101 years old and turns out to have committed a war crime in a time past the statute of limitations, we can be reasonably sure that they won't have committed a crime recently and that they won't commit a crime in the near future. As such, there is no compelling reason to limit their freedom for the safety of their neighbors.

People in modern developed societies don't get locked up because "they deserve it". Mankind is unique in that it has endless ability to grow and endless opportunity for compassion. We are able to forgive the most evil of people, and verily, we ought to if they prove their capacity to change. I hope you recognize that you're using the same line of logic as the conservatives here. Of course their sin will follow them, but the societal consequences of their sin needn't.

A repentant murderer is forever haunted by his actions, but our society ought to accept that repentance. Anything else is downright monstrous. He will stand before the face of God and answer for his evil, and before then, we have to make sure that more people aren't hurt by him. If that's the case, then of course we'll incarcerate them, or maybe even rehabilitate them. But to give an evil for an evil simply because it is "deserved" is such backwards thinking, particularly for a leftist.

Now, I don't mean to say "oh, those poor genociders". I, for one, believe that everything they got, they asked for, they *deserved*. But that's irrational, that ought to be entirely taken out of the equation. That's not the way we run our criminal justice system, because above all else, it is for the prevention of crimes. If it prevents crime, we incarcerate an individual. If it doesn't, we don't. And isn't that the most moral of options?

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

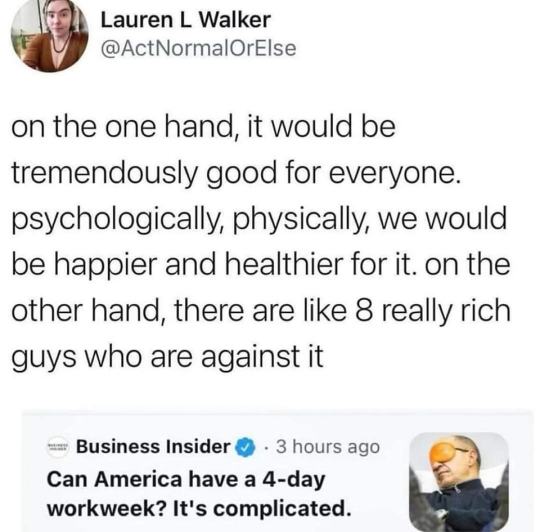

Alright, please allow me to rant here. This is not an effective solution for the average underpaid blue-collar worker. This is not in the interests of labor or unions. There are genuine upsides to a four day work week, but the "8 really rich guys" aren't the only ones who are against it, because in every single one of these scenarios, you cannot just dig in on a surface level. There are layers here, ones that may reveal some real harm to the worker.

First of all, we have to make some presuppositions, which will allow me to get into the same framework as you. For one, I'm sure none of you would disagree that labor politics should take care of the poorest fist, that is, to focus on the people who need the *most* help. Secondly, I assume that you fellas are pro-union, and oppose right-to-work. In fact, I'm going to go out and assume that you support advanced regulation to help unions and oppose strikebreaking. And I'm going to assume that you do not care at all about the economic standing of the business owner, only the workers (which I myself disagree with, I think that everyone should be looked after, but whatever).

In that case, this would be intolerable. But let me point out the positives first. Sticking to a forty hour work week, each individual would serve 10 hours a day. Compared to the standard 8 hour day, psychologically, the day doesn't feel that much longer than it would otherwise, and a third day off is universally beloved. This objectively makes workers happier and healthier, and even though you don't necessarily care about it, more productive. That third weekday also allows for more time with family, which is key to a good education for the workers' kids and could even lead to lower divorce rates. Everyone wins here.

Except one group, actually. And that is the destitute union man, especially the older ones. I know a lot of people in the oil fields. I know a lot of government workers. And I'm sure you know some sort of person in your town. The miner. The man working the auto industry. Barely making enough to stay alive and dependent upon the union for just that. It's disgusting, and honestly one of the best arguments against modern capitalism (much more so than complaining that it discriminates against ADHD folks or whatever else is the current hot topic). And they don't want the 4 day work week for one reason alone -- overtime.

Because it gets really hard to pull a double shift when you get off for four hours of sleep each night, less when accounting for travel and getting up in the morning. And unlike most people, most of these folks *have* to work massive amounts of overtime in order to make enough money to raise a family. That's one of the reasons they're so vociferously tied to a union -- to make sure that the overtime numbers come out fairly. Otherwise, they're out on the streets. And while an 8 hour work day versus a 10 hour work day isn't a lot, a 16 hour work day versus a 20 hour work day is night and day, quite literally. It makes things so much worse for the most vulnerable within our society, the man who makes no money *and* must raise a family, usually a large one. This doesn't help his health, this doesn't assist him, it just makes life even more of a living hell than it already is.

And don't come in with the rejoinder of "just increase the minimum wage". Disregarding any *massive* political issues of getting the wage to a place where overtime isn't required (some $25-30 an hour for a family of six to barely get by ($55,000), that's simply not going to pass Congress, at least while the dollar remains valued as is), that also massively accelerates the "sweatshopification" of America, because, believe it or not, massive corporations don't care about their workers. You bring in a $25 minimum wage, and every single job out here is going over to China, where they don't have neat stuff like "labor regulations" or "environmental regulations" or "having to pay workers". Beyond that, it also hurts American mom and pop shops, which is the only reasons that transnational corporations don't price gouge even more than they do now.

This is an incredibly complex issue, one that helps the average worker and kills the most vulnerable worker. I for one, am not willing to sacrifice my brethren on the altar of progress, although I'm sure many of you may. But please remember that there is nuance to this, and that there are more than "8 really rich guys" who oppose this.

Edit: You fellas do understand that making a 32 hour work week is a thousand times worse than even this, right? A national 25% increase in wages is going to absolutely demolish economic stability, along with annihilating any semblance of low prices, devaluing the dollar, which in turn causes stagflation. I'm not exactly sure how many of you are familiar with the economy of the early 1970s, but then you could buy a good burger for a half dollar or less. There's the old article of a cup of coffee becoming more than a nickel during the Carter administration. That's not just boomers going on a nostalgia trip, that's the reality of what occurred in the seventies and changed in the seventies. Stagflation hurts the common man more than maybe anything else, and a 25% increase in wages is going to contribute to that, guaranteed, because that is a foremost way to cause instability, which is fatal.

The issue is that you fellas are Romantic in an economic system that simply doesn't allow for Romanticism. The Sueno Impossible doesn't work. We need to understand that we must work around corporate greed rather than eliminating it in one fell swoop. Because if we attempt to legislate greed away, there are many things that fall, not just the corporations. Heck, I'd offer you more credit if you were straight revolutionaries, because at least that contains more of a chance of success. But the economy, the dollar, the wages of the common man, there are so many factors going into it. Think of it as the Sword of Damocles. Yes, it hangs, but you can't attempt to rush and take care of it, or you shall get run through. The best we can do is to help the King survive as is. We must help the worker in a way that actually helps.

#labor#leftism#the cosmopolitan left has an issue with leaving the rural worker behind in the grand struggle against corporate greed#it's important to note that the cause of worker solidarity is universal#something especially worth bringing up in the wake of harsh political divides between worldviews that characterizes the urban and rural man#but even so#the flag waving MAGA J6er is your brother in this fight#just as the blue haired autistic pansexual is his#may God bless the both of you

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

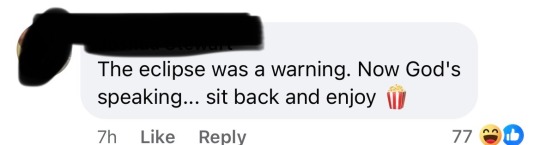

"I offer you no sign but the sign of the prophet Jonas."

Beyond the actual, literal definition of the statement declawing any semblance of an apocalyptic "sign", was this not the core of his story? That he was happily waiting (popcorn bucket in hand) for the judgement to come to a people who could be saved if he had only tried? Him caring more for the plant that gave him convenience than the deliverance of an entire city from destruction? It reminds me of a lot of my problems with modern Protestant Christianity in general.

rant.

Ok so right now we are approaching a rapture date set. May the 19th. People are claiming the sign of Jonah was an eclipse and not Jesus’ literal words about his own death. And so they gave the world 40 days to repent before Jesus comes back. According to them the 40 days ends on the 19th where Jesus will come back. Here’s my issue with the absolute heresy:

People like this ALL OVER Facebook. Sit back and enjoy? Correct me if I’m wrong but no Christian should be excited to watch people die and get judged to hell. This idea of escapism is so engrained that people no longer care about the dying world around us. They only care about them getting zapped out of here and not having to suffer.

we lose our heart for the lost when all we can think about is what we get to enjoy. We care less about the suffering of our neighbors when we are just sitting around waiting for Jesus to get us out. You are going to sit back and enjoy while judgement falls on people? How about you get out there and get busy. If you truly believed the crap you say you wouldn’t be a smart ass on Facebook posting cocky popcorn emoji. You’d be telling every single person you could to follow Jesus. Begging them even.

but in my experience people like this just don’t care. They will believe this crap and when the 20th comes they will believe more crap. And they will continue following false prophet after false prophet who tells them the world is going to hell and it doesn’t matter because they get to get out before anything bad happens.

Makes me sick.

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Damsel Pristine Cut Prediction

Alright, I have a theory for the leadup to Damsel’s Chapter Three. So, what information do we have on Chapter Three presently? Well, we already know it’s going to be depressing as all heck (Tony has mentioned that Abby's plan for the chapter would be very painful for both you and the Princess). We know that it will exist in relation to staying with her in the cabin. We know that there are heavily Romantic themes within the chapter. We know that one of Damsel’s primary themes is her lack of agency, so frightening in her Deconstruction and somewhat nervously endearing in her fairytale escape. So to recap, it will focus on Damsel and you staying together, it will focus on the Damsel’s lack of agency, and it will play into traditional Romantic tropes while simultaneously deconstructing them.

So the idea is that when Damsel declares her wish to leave, rather than simply deconstructing her, you deny her request. You declare that you will stay with her and live out your romantic destiny. While taken aback, she accedes to your request, as she always would. So you stay together in the basement, spending time with each other, maybe opening up new lines of dialogue. She would be acting odd throughout, clearly wanting to leave but also wholly devoted to you. If you say that you’d love to continue to be with her, then what does leaving really matter? She has you, what more could she want? But the drive to leave, to be free, it still tugs at her, to fulfill her purpose as a vessel.

She eventually works up the courage to ask you if you would be willing to leave yet. You could either agree and get the standard “Romantic Haze” ending, or continue staying with her, much to Hero’s chagrin. It feels uncomfortable to so disregard the Princess’s wishes for this life. Smitten, for his part, is so completely out of touch with reality that he genuinely believes that spending time with the Princess like this is something that she honestly wants, and is pushing for a continuation of the status quo. He wants the time with the Princess, he wants to take her and live out their life together, forever.

In response to your second denial, she is clearly hurt but also putting on a brave face. *For his sake.* She is happy, she tells herself. She is with the one she loves, she is willing to do whatever he wants. If being with him would make him happy, then that is what she will do. You unlock more dialogue with her. You talk and laugh and love each other. But the Damsel’s wishes still have been ignored, the one thing she wanted, taken from her. She, after sitting for a long while with you, declares affirmatively that it is her wish to leave. Once again, you can simply get your “Romantic Haze” and abort, or you can continue on and definitively say no. She accepts your wishes, a smile on her face as a tear rolls down her cheek (meant to be reminiscent of the Scorched Grey leadup).

The dialogue for you… shifts. It becomes more possessive, more controlling. More in tune with the player. The Hero, by this point, is fuming. He keeps telling you that this isn’t right, that this isn’t what she wants and that this needs to stop. You ignore him. You and the Damsel will be together, there will be nothing standing in your way. You lifting her, her lifting you, forever and ever. Consumed by true belief, there is absolutely nothing that will stop you. You are her guide, the one who knows what is best for her. She needs you and you need her.

Damsel, in one final effort, merely asks to go up the stairs, not to leave but simply to look out the window. To see the stars, to keep a grasp of what could have been. To have a dream. The game will allow you to say “no” as long as you want, but she will begin to deconstruct along that route, unless you allow her to go upstairs. You take her hand and the music swells as you take the stairs, and despite the bleakness of the moment, despite the fact that you will never leave, the moment is beautiful, seeing a smile upon her face that you have not in a long while, seeing the wonder of the outside world. She smiles, turns to you with tears filling her eyes.

“My dashing hero.”

“I’m sorry.”

She grabs the knife and begins to stab herself in a cruel reflection of Chapter One, apologizing to you all the while. She was incapable of living like this, incapable of being there for you and for that she is truly, genuinely apologetic. She is broken and tearful the whole while, and eventually, as the last flame of light exits her eyes, she dies, with a simple “I’m so sorry” exiting her lips. The Smitten immediately takes the blade to end his own life, both finally being together forever in the cabin. The Hero does not try to stop him this time.

#slay the princess#the damsel#stp damsel#black tabby games#stp princess#really straddling the line between fan theory and fanfic#this would kill my soul

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

For They Know Not What They Do

The Story that is Christianity

Many have written pages on pages on pages of how to understand Christianity. Two of my favorite books of all time, “Mere Christianity” and “Orthodoxy”, both approach the issue of what the core of Christianity is for the layman. The intellectual (or perhaps a more accurate term would be “armchair theologian”) has even more access to works ascertaining precisely what Christianity is. I would say that is a fantastic way of getting to know our place within the world and our relationship with the God that ensures every atom moves properly. I also tend to view these works, seminal as they may be, as incomplete. But I suppose they aren’t trying to be complete, really. That’s because they are only building upon a completed text, of course, one they can hardly re-establish while remaining true to it and simultaneously expanding. They aren’t going to have the spark of the original.

But that’s not my problem with the modern discourse around Christianity. I understand that they lack the spark of the original. When dealing with direct divine inspiration, I would imagine that tends to happen. My problem is that, beyond lacking the spark of the original, it doesn’t even try to come close, it doesn’t *search* for that spark. There is nothing ventured back to the original composition except as intellectual evidence for a broader thesis. That is, the Gospel, the single most important piece of literature in history, is no longer a piece of literature but a manuscript. Because the core of Christianity is not praxis or hermeneutics or any other ten dollar word. It was passed from carpenter to fishermen. Christianity is, with all else stripped away like chaff in the wind, a Story.

It is a Story of love and betrayal. It is a Story about good vanquishing evil. It is a Story of a Bridegroom united with His Bride, finally redeemed after constant failure and everlasting patience. It is a Story of a Father and Son, and how they, despite the pervasiveness of wickedness, would save the world from itself. It is a Story of love and the sacrifice that would naturally pour out from that love. It is a Story of undeserved grace by one party and an undeserved outburst of fury on the part of the other. It is, as odd as it is to say it, a grand Romance, one that spans across the entire history of man and especially the history of one Man in particular. It is a Story.

And like all stories, this one has a beginning. In fact, it has something before the beginning, before the very concept of time. It has a God, triune in nature, omnipotent and wholly benevolent. Now, this God is a creative God, and as such shapes the world. He forms what would become reality, all the laws of nature and mathematics, the ideas of time, of space, of matter itself, ex nihilo. He makes light and life, seas and earth and celestial bodies, animals and plants in an explosion of what can only be described as art. And He makes man, defined to be with a soul, in the imago Dei, His very image, capable of creation, capable of love, capable of making a sincere decision. The crown of what exists.

And with that, the very next day He rests, surveying His creation. He has done a good work, shrouding the world in the radiant light that He is. He has made something that continues on its own in a way, yet in another way is still eternally dependent upon Him for every action, every movement, every moment in time. Something has been created and with that beauty arises where there was none before. There is a completion to what was to be done, man being what was finally needed for the world to be properly finished. He loves the world, and He loves man. And so He rests.

After that, He graces us with something magical. You want to know what was the first thing He gave man beyond the very life we hold so closely? The concept of romance, of marriage. Of giving one’s life over to another, of being able to truly understand another individual in a way that nobody else can. Of living your life for someone other than yourself, of being, in a way, one with another individual, fully free and without fear or reservation, only sheer, insurmountable love. It is the closest thing that we have to a relationship with Him with another individual. It is the epitome of a relationship among us, one that if we are lucky enough to have it, is the most beautiful thing we can have within the confines of this world. And He gave it to us because He loves man.

And man loves Him, the only creature able to love establishing their love first and foremost. God created a garden, one in which it is declared that He walked with man. At every point man was covered by who God was, engaging with Him and with each other in the beauty of merely being able to speak, to talk, to be in conversation with the being behind everything that happens at any point in time, to talk to someone unimaginably beyond the world yet still willing to interact with it, with His greatest creation. And He offers but one demand – do not eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.

And, of course, they do so anyway and as such are blemished by sin and therefore must be driven out of the garden, out of the sight of the God that loves them so much. With the knowledge of what evil is, evil becomes an everyday occurrence rather than the quite literally unthinkable action that it was within the garden. Their love for God is tarnished like silver being exposed to oxygen. It is still silver, no doubt, but it is difficult to tell that it was the same thing as the genuine article, and while the value inherent within it will still be present (the silver atoms aren’t leaving anytime soon), it would require the level of atomic precision to return it to its original form, something we are entirely incapable of doing.

With that, God can no longer speak with them, walk with them, be with them in the same way He used to. For sin cannot exist within the sight of God, the idea is a logical impossibility. Just as matter and antimatter cannot coexist within any one location, neither can the absence of God and the presence of God. There’s one theory that the reason God was no longer able to be in the physical presence of humanity is because the sinful nature of ourselves would quite literally destroy our very personages if exposed to the sheer holiness that is Him. I don’t know if it’s true or not, and it is impossible to know, but it sure does preach well.

Most of the remainder of the Old Testament squarely places a focus on the Jews. For his devotion to God, Abraham was given an assurance that his descendants would be specially protected by God as long as they remained faithful, and as such the Jews became the “Chosen People”. This assurance is referred to as the Abrahamic Covenant. They were gifted with the Law, which essentially was a document of divine nature that established what they could and could not do as a nation. One of the most important parts both for their society and Christianity wholesale was that of animal sacrifice, something both commonplace and unique among the Jews. Rather than in other societies, where an animal sacrifice was there to satisfy the gods and not much more, the Jews symbolically placed their sins upon the blood of a pure white lamb and then killed it as a symbol of repentance (where we get the term ‘scapegoat’ from). And if they continued to abide by that Abrahamic Covenant and showed a dedication to faithfulness, then God would accept that symbol.

Throughout the Old Testament, an intriguing turn of events would begin to rear its head – they did not remain faithful. Throughout the history of Israel, the Jews would remain stubbornly in a constant flux between faithfulness and the complete denial of basic morality. Many times they would clean up their act, so to speak, and less than a decade later fall into depravity. The majority of the Old Testament is them doing terrible stuff, getting punished, getting better, and then returning to exactly what they were doing before. As it can be understood, for a society solely existing due to God’s special favor, this was less than heartening. I want to take what may seem like a sharp turn into one of the more overlooked books of the Bible, one of the (very many) stories about a prophet attempting to bring Israel back to God and one of my favorites.

The Book of Hosea, at least the beginning of it, is a love story between a man and his wife. Throughout the section you find this book in, it is filled with books that essentially amount to a whole bunch of sermons being combined. This is not that. This is a genuinely beautiful story, this is something that I would want to read, this is *real*. And it may well be the best summation of the Old Testament in the entire Bible. This is exactly what I was searching for with the rest of my readings, something that so perfectly encapsulates the relationship between God and those who He loves.

Hosea was a prophet, someone who was given direction from God to return Israel to its worship of Him. Many had come before him, many would come after him. One could even say that his actions were entirely futile. But he had a calling, despite the truly unrepentant nature of Israel, and he was not exactly going to tell God of all people “no” – that was the very thing he hated so much about the society he found himself in. So he decided to follow that calling, becoming the newest prophet of Israel.

With that came instruction from God. He was to take a certain individual as his wife, one by the name of Gomer. She was a prostitute, and more or less written off when it came to marital prospects, perhaps understandably so. But Hosea was commanded to do so, and as such took her as his wife. And Hosea took care of her, fully and totally, as a husband should, providing for her economically, emotionally, generally being an all around good husband. Why? Simply because he loved her. He loved Gomer more than anyone else within the world. Certainly more than anyone else would within the nation, what with all of the social devastation from her peers of both sexes.

And as I’m sure you can tell, the infidelity continued throughout the marriage. Constant heartbreak on the part of Hosea, who loved his wife, with the constant rejection of the wife incapable of loving him. Yet Hosea did not cease loving her. Even when the provisions he offered to her went to those she would cheat with him on, Hosea did not cease providing for her, something that was well outside of the norm within society, when at the very least divorce was the status quo. Hosea was continuously loving his wife, and he was continuously being emotionally destroyed by her. One day, Gomer disappeared for longer than she usually did. Hosea went looking for her, and found that she was being sold into what amounted to sex slavery. And once again, against *all of the* standards of the time, he went and gathered together a small fortune to purchase her and free her. And why was that? *Because he loved her.* And the absolute kicker is, there is no record of her ever stopping her activities. Despite all of his love for her, despite everything he gave up emotionally and physically for their marriage, she would always let him down. It was her nature. To fail and hurt in the process but to always be able to return to one who would always love her, it’s heartbreaking in its tragedy.

It’s not difficult to see the allegory between this and Israel’s repeated falls from the graces of God. A nation chosen by God in particular, one that is provided for and taken care of more than any else in the world, one he frees from backbreaking slavery, one he offers bountiful land to despite everything. A nation that is truly blessed among all others. It of all countries should be one not to turn away from the path that has been consistently positively reinforced and consistently negatively punished. Yet it still does. Because men loved darkness rather than light. Because the love offered towards us is something they took for granted. Because it is our nature to spurn that love.

Yet there would be one moment to establish that love forever in the eyes of God, and it began with one man, by the name of Jesus Christ of Nazareth, the King of the Jews. The humiliation of the Incarnation is something that deserves to be talked more about. God becoming man and all the wonder inherent in that is highlighted in various Christmas events and the like, but it rarely goes anywhere beyond the surface level. Another way to say it would be that the substance is highlighted, but oddly enough not the sacrifice of the thing that would eventually become Calvary. For in the Incarnation was the stripping down of Christ long before His arrest. Taken from the omnipotence of Godhood to the inability of a child, forced to flee to Egypt just so He wouldn’t be killed before He turned three years old. Losing omniscience for the insight of an infant, losing omnipotence for the physical ability of a baby. The Incarnation was the deliberate elimination of anything especially divine He had, with the sole exception of his relationship with his Father. It is hard to overstate exactly how drastic a change like this was. Imagine losing any and all sensation, sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, all at once, and then entering into the world and being told to go out and live, get stuff done, have a proper life. The thought is quite frankly absurd.

Yet all of this and more was suffered for love. For the chance to live as a person to save all people. For the beauty in finally freeing mankind from our nature of destruction to all we come in contact with. For love. Love for us, broken and fallen as we may be, entirely covered in the ink that obscures what we could be from what we are. The entrance of Christ alone into the world is a sacrifice for our sin, and it would not be the last, as I’m sure you are aware. Everything, absolutely everything orchestrated throughout the Old Testament lines up towards this moment. Everything evil and redeemed and evil and redeemed and evil and redeemed, fluctuating back and forth and forth and back for a purpose, for the ultimate evil and the ultimate redemption. All that was needed was for that very redemption to enter the world. And so He did, incapable of speaking, incapable of walking, incapable of bending the entire cosmos to Himself with one thought. The birth of Christ to Mary was, in essence, His first death.

Jesus Christ had lived life as a man among men, with one exception. He had never sinned, not once. The evil that had plagued humanity as a whole was absent from Him, not a speckle on His fleece, for the entirety of His life. All of the absurd wickedness, every disgusting thing mankind suffers from, it was all gone from His personage. He was, morally speaking, perfection. And with that perfection comes something important. With that truly pure fleece, He was able to be a sacrifice that was more than symbolic. No longer would man slaughter a lamb, a symbol of sin, and obtain a symbol of repentance. Instead, man would commit the ultimate sin and slaughter The Lamb, The Son sent among them, and with The Son's sacrifice gain the possibility of True Repentance.

Eventually, He would begin to teach. A message of adhering to the spirit rather than the letter of the Law, which Israel was just beginning to follow. He taught forgiveness beyond what the Law said, commitment to marriage beyond what the Law said, being willing to help the fellow man beyond what the Law said. He did not supersede the Law, but He was the completion of it. Everything the Law said, He went beyond, not because He added to it, but because He fulfilled it. Everything He said was the intention of that Law, the meaning of it that had been lost to tradition for centuries. Israel had finally established a dedication to the Law and Jesus swept that rug from underneath their feet. It was the acceptance of the thought that went behind the Law rather than exactly what it said.

And yet the position was unpopular with the people whose opinions on the subject mattered. The local Jewish ruling classes were quite comfortable with the acceptance of established law and tradition, leaving the more learned and established classes at the top. The local Roman ruling classes were quite comfortable without more religious zealotry breaking out in an area known for it. The idea of expanding upon existing Law and riling up support for and against it in an endless cycle of polarization was not in either of their interests. Yet the movement continued to grow, and it increasingly became an elephant in the room when it came to politics within the area. With that, quite reasonably, the decision was made to kill Jesus on charges of sacrilege.

While they were taking such an action, Jesus was doing something entirely different. He was preparing Himself. He went over to a garden and began to pray, to beg, to plead for any other option. He did not want to die, He was genuinely scared of the suffering that would await Him. He sweated drops of blood throughout his prayer, such was the fear that took hold of Him. He was in agony. There was nothing He wanted less than to die an excruciatingly painful death. Yet He declares that it is His duty, that He must accept death. And that is what He does. The Romans and Jews arrive to take Him away. He does not resist.

They brought Him before the Romans, because they, as rulers of the area, were the only ones who could prescribe capital punishment legally. There was an issue, however – nothing within Roman law actually enabled them to kill an individual for blasphemy against a god not recognized by Rome at all. So they simply decided to go with charges of treason. A similar issue arose – there was basically no evidence for a statement like that. So the governor of the region more or less tried to weasel his way out of it. He summoned Jesus, desperate for any sort of denial that would allow him to say there wasn’t enough evidence. Jesus, for his part, was cryptic, of absolutely zero help to the governor, Himself, or anyone, really.

The governor called for something, anything to assuage the crowd from a death penalty with no evidence, something guaranteed to look bad to his higher-ups. Bargaining – citing a Jewish holiday about to come up, he offered a choice between two prisoners to be freed – Jesus or a murderous thief. Those who were present for the choice, a mob at this point, called for the freedom of the murderer. The crowd did not yield. Humiliation – a beating, fine clothes, a scepter and a crown of thorns. The crowd did not yield. A “lesser” punishment than execution – nine and twenty lashes from a cat o’ nine tails, each tail burying itself in muscle rather than skin and more or less skinning Him alive, with immeasurable pain coursing through every single second of trauma to his rapidly shrinking back. For some point of reference, the standard death penalty within the region was thirty lashes from this very whip. The crowd. did. not. yield. There would be no option other than crucifixion. They would never be content with anything else. And so the order went.

In the most damning moment in the history of humanity, we determined we would commit Deicide. And the deed was done. Christ, God Himself on the earth, innocent in the truest sense of the word, slowly dragged His own cross through the streets of Jerusalem towards a hill called Calvary, where He would meet death. He stumbled, weak from blood loss and unable to continue to carry anything, let alone a cross. The pinnacle of mankind, brought down to being no more capable of preaching than a corpse like any other; He was thirty-three years old. And behind Him followed the very crowd that put Him to death, some jeering, some disgusted by He who would attempt to destroy Judaism, some even weeping over the demise that they themselves caused, any semblance of righteous fury gone from their eyes.

Eventually the procession was able to make it to Calvary, at which point the crucifixion began. There are two tangentially important facts about crucifixion as a means of execution. The first is that Jewish Law states that any who die by being hanged on a tree have been cursed by God. It was considered that anyone who goes through that was abandoned by God, and it’s a generally bad omen. The second fact, somewhat more well-known, is that “crucifixion” is the root of the word “excruciating”. Crucifixion was not the means of execution generally used; it was always used in cases where an example was going to be made, due to its incredible cruelty as an execution device and its incredibly public location.

A brief overview of how exactly an individual dies would begin with both arms secured in place to the cross with nails, hammered into the wrist between the radius and ulna and directly through the median nerve. This would leave the body hanging from the overextended arms, which, apart from the immense pain such a position provides, physiologically makes it impossible to inhale. That’s where the legs being kept in place (with rope or nails) would come in, pushing the body up whenever oxygen was needed, and allowing the diaphragm to do its job. This had the added effect of causing even more pain from the scraping of the oft-scourged back against the rough wood of the cross. The process would continue until either the victim would die of asphyxiation due to exhaustion of the legs or until their legs were broken, making them incapable of continuing breathing. In total, time to die was varied but could last up to several days.

As the nails hammer into the flesh of Jesus Christ, He does not resist. As He is hoisted into an upright position as the death knell tolls and His minutes upon the earth begin counting down, He does not resist. As an innocent man being killed for a crime He did not commit, He does not resist. He is simply a Lamb walking quietly to the slaughter. The cross is beyond painful, there is nothing that could have prepared Him for such physical torture. But He does not resist. He shouts out the opening line to a song He knows well: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me.” He does not believe He has been abandoned by God, but in the moment, it certainly feels that way. It is hard to think of anything outside the pain of the moment.

Voices resound around the crowd watching Him. Cries taunting Him to save Himself if He could supposedly save so many others. The apparent desecration of God is unthinkable within Jewish culture, no god of theirs could die like that. And so, in their denial of such a concept, they desecrated the only God they could ever have laid their eyes upon, the only God they ever could have spoken to, the only God who lived among them, who ate and talked and laughed among them. The Human God and the Divine Man, being scourged, crucified, abused with all manner of insults. He does not resist. The only thing He offers up out of His battered, gasping chest is a plea, not even to them: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

While I may have offered the Book of Hosea as the clearest summation of the Old Testament, those ten words are the clearest summation of the New. For despite everything, all of the suffering that we placed upon each other, for all of our sins, for everything. For the very execution of the only perfect man to ever live, for the very execution of the God who knows and loves every single individual, we are forgiven. Yes, it is in our nature to betray that love constantly, it is in our nature to harm everyone we come in contact with, it is in our nature to hate and kill and lie. But we are forgiven regardless.