You might know me from SnapRevise. Have questions? Get in touch here via the AMA page or drop me a line at [email protected]. There's no such thing as a silly question and I'll do my best to answer everything you send my way. {Check out my Info + Contact page for more details.} ✌︎ ✌︎ ✌︎

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

From the coldest cold to the hottest hot, here’s all the universe’s temperatures.

(from BBC Future)

Bonus question: What is hotter, a boiling tea kettle or an iceberg?

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

hey fran do you not teach on snaprevise anymore

Hey, I do actually! I just don’t do the videos anymore but I am still speaking at the seminars - the next ones are on Jan 19-20.

If you do want to contact me though, please do drop [email protected] an email and mention that you would like me to respond to it specifically 😊

1 note

·

View note

Text

Laurel, Yanni and McGurk: Why your life is a lie

Update: I’m not dead! I know I haven’t been posting regularly. I’m sorry. It’s down to two things really: a) I’ve been very busy with the new job and b) I’ve frankly really struggled to find any kind of inspiration lately - I suppose that’s what happens when your life is taken over by your job. And you’re an auditor.

But this week this whole Yanni/Laurel brought about a bit of a brainwave - not least because it’s done nothing but do my nut in. Literally every one of my social media feeds is infected with these words. Apart from Twitter - but only because it contains an option to mute words - but even then I’m still swamped by the overhyped, equally annoying sequel: green needle/brainstorm.

However, as with most things I hate, I’m going to put my back into this.

A few things are going to happen in the next few minutes: we’re going to unpack the explanations behind these phenomena, and then I’m going to try to shatter your perception of the world.

The Yanni/Laurel thing has now been confirmed as an aural phenomenon: if you were to plot the frequencies present in the recording against time, much like something you’d get on Audacity or any other kind of audio-editing software, you would see that this clip is made up of a mixture of high and low frequency tones. Yanni is formed from the higher frequencies. Laurel is characterised by lower frequencies. It’s like listening to what are essentially two different tracks of music that have been overlaid. If your ear is more attuned to higher frequencies (perhaps the younger among you), or you’re the kind of animal that turns down the bass on your speakers, you’re going to hear Yanni. The vast majority of people however hear Laurel, because, well, we’re older.

Now we come to Laurel’s little sister: green-needle/brainstorm. She’s a little smarter, a tad more interesting and she was allowed to wear makeup from a younger age. What you can hear in this recording can be changed depending on simply the word you’re looking at when you hear it, which is much more than a physical phenomenon - it’s a psychological one. We know something to be true - that we’re hearing the same sound each time, but our perception of it changes. This is interesting for two reasons: firstly, on a psychological level it helps us to dissect how our brains work, and secondly, more importantly, it proves to us that objective truth is a fallacy.

Green needle/brainstorm is a slightly more evolved example of the McGurk effect, which is a widely known and studied phenomenon where your brain can interpret the same audio/visual recording as two different sounds depending on the context it’s given. This context often comes in the form of a visual cue, which is much better explained by the folks at Horizon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G-lN8vWm3m0. Ultimately it comes about because of the top-down processing in our brains. What does this mean? Well, effectively our brains process a whole load of information all at once, and uses its analysis of this to work out the most probable explanation of our current circumstances to make sense of the world. For example, imagine you’re on safari. There’s not a cloud in the sky, you’ve got the sunroof down and you’re driving through a woody looking area. You hear a dense flock of startled birds swiftly fly out of the branches above you as your jeep slams through the undergrowth. They’re so close you can feel the beat of their wings in the air around you, and suddenly you feel something cold drip onto your hair and down your neck.

You’ve surely been shat on.

You look up and see a monkey peering down at you from the sunroof, drooling.

But for a second, you believed you’d been shat on, well, because you hadn’t noticed the monkey. Hey, we’re not perfect.

Additionally your analysis often relies on the outcomes of events that it’s seen before and it projects these probabilities on the current situation in order to work out what’s going on. For example, if you’ve had a horrid cough before and went to the GP, who told you it was pneumonia, the next time you get a cough you’re more likely to think it’s pneumonia again, even though that’s actually quite unlikely. The McGurk effect combines these two analytical phenomena. Most of the time you hear a hard “k” sound and seen a particular mouth shape, it’s turned out to be a word starting with that letter. But if that same exact sound is accompanied by a “g” mouth shape, your brain goes “Well, based on past experience, that word must begin with a G”.

TLDR: we can easily trick ourselves, and others based on the subset and quality of information we allow ourselves to see.

As well as being a fun illusion, like all other illusions it highlights something more insidious: we’re all primed for bias - it’s inherently how our brain deals with the mound of information it receives every single millisecond of every day. If we didn’t skip straight to conclusions we’d end up overthinking everything and ultimately not taking any action. Evolutionarily speaking, our ancestors would have died if they didn’t spring into action on hearing twigs breaking, assuming it was indicative of an imminent attack. The benefit of catching our predators pre-arrack vastly outweighed the excess energy expended on false alarms. Out of our ancestors, those who were the quickest to leap into action on hearing the quietest of sounds lived the longest. However, in modern day terms this kind of cranial processing doesn’t work as well. Sure, based on he gait of the person in front of you at Kings Cross, you might predict they’re going to take a hard swerve left to the Victoria line and you can use that information to prevent an embarrassing collision. I’m not saying this fundamental system of processing doesn’t have its merits - I’m just saying it has fewer: we don’t spend every waking moment fending off predators any more, because we’ve built infrastructure, terraformed land, driven predators out of their natural habitats and evolved societies that provide you with security against dangerous individuals in return for a cut of your income.

So we find ourselves in conflict. We have brains that are used to using whatever information is conveniently available and pre-existing knowledge to judge, but vastly reduced the need for that judgement. We’ve also reduced the benefits of this judgement - if anything it’s often frowned upon. We’ve developed a new term for unnecessary judgement: prejudice. And we often think we’re well aware of our own prejudices and can therefore escape them - but I’m here to tell you that the vast majority of us can’t. Take this for example:

Try to memorise these words: Adventure, curious, sun, brave, clean, friendly, ocean, white, fruit, learn, free, wholesome, holiday, talented.

Now read this: Alan is making plans for his gap year. He wants to visit the South America but is struggling to fit that in with his plans to take part in a motorcross rally. He missed it the year before because he broke his leg in the practice round. He needs to find his passport, which he lost on his last trip back from Bali and hopes his friend accidentally picked up. He also wants to visit India and needs to find time to move into his flat in Camden before he starts at his London uni.

What do you think of Alan?

What would you have thought had you memorised these words instead: Jealous, green, selfish, cocaine, petty, reckless, red, corrupt, idiot, lad, careless, clown, rude.

Go back and read the paragraph again - see what you think.

He might have seemed a bit of a gap yah wanker that time, methinks.

This is something called priming, which is an extension of the broken thinking we discussed earlier. It’s exactly how advertising works - we can’t help but associate things together when they’re close together, either spatially or temporally. You judged Alan because those lists of words made you linger on different sets of details in the narrative each time. If you start to form an opinion, you’re more likely to see details that reinforce them.

So what’s my point? I’ve just shown you that this kind of thinking is inescapable: you knew where this article was going and yet you likely painted a picture of two different Alans. I’ve told you that our brains are hard-wired for bias. That our perception of the world is inherently, inescapably warped. That we all have our blind spots. That we can convince ourselves of anything depending on what details we choose to notice. And that our choices of details are rooted in past experience. The logical conclusion of this is that as we get older, we get more biased. Something happens, we learn from it, maybe even form a slight opinion, we stumble across varied details in the subsequent hours, days, weeks of our lives, and out of these details our brains are primed to pick out those that are familiar, opinions and beliefs are justified and strengthened, our filter for details gets narrower, our opinion gets stronger, our blinkers come down even more, so on and so forth. Incidentally it’s eerily similar to how evolution works.

We’re built from bias.

This means that in order to even be able to grasp at objective truth, you have to work. Really work. Hard. And I think this is something that is totally overlooked in our current political climate. We all think that facts are facts - they’re not, simply by virtue of being beheld by us. We, these flawed, inherently biased networks of synapses in cages of bone and bags of skin. But we need to guard against this. No man is an island, and as a society we need to believe in the concept of objective truth, even if we accept we’ll never achieve it. If we don’t, we lose our baseline for discussion, leading to a society which is unable to sort opinion from fact: one in which radical, absurd and harmful ideas could propagate at the same speed as those more closely aligned with common sense, driven by whimsy. Truth is the tare weight for any battle of wits - without it, there could be no consensus.

So if we must believe in an objective truth, but can only ever see it through a glass, darkly, so to speak, how can we polish the lens?

This brings us full circle to audit, my bread and butter, and perhaps why the question of truth is at the front of my mind. Audit is fully preoccupied with objectivity and truth - firms drop clients and lose money because of it all the time. This is because our job is to take the draft financial statements a company prepares before they’re published and ensure that the figures in them haven’t just been made up, or tweaked. We need to assess whether the numbers show an adequately “true and fair” view of what’s happened to that company during the year. As with everything, we can never be 100% certain of the truth, or fairness of accounts, so we test the numbers to a reasonable level of assurance.

Believe it or not, there are a couple of aspects that are quite interesting about it:

Firstly, sampling. Much like biologists attempting to study animals in a large habitat, the feat of fully auditing every single transaction a company makes during the year is nigh on impossible. Instead we choose a representative sample of transactions and look at those in more detail to work out if they were recorded correctly. We’re always terrified of choosing the wrong number of transactions - if we audit too few, we might miss one large one which was fraudulent or recorded wrongly - one typo could change an overall profit to a loss. If I wasn’t thorough enough, I could lose my job over that.

Secondly, we rely heavily on the people running the audited company to tell us what happened during the year. If for example they failed to tell us that they underwent a huge merger, we might audit them against the wrong set of financial standards. We might think it’s all fine by those standards - but that’s a false positive. We used the wrong measure of truth, because we didn’t have all of the facts.

So why did I bother to tell you all this?

Because auditors measure truth for a living, and you might learn something from the highly discussed and regulated procedures we use day in, day out. The next time you find yourself judging something - anything, for that matter, however small - ask yourself these questions:

How much detail can I subtract from the situation before I change my view of it?

Is there a detail or perspective I’m missing because I’m being primed by my prior beliefs, assumptions or experiences?

If you find the threshold for Q1 and an example for Q2, you’ll be much closer to the truth than you were before.

You never know, you might end up finding truth in the most unlikely of places, and applying measured skepticism can lead to some of the most - sometimes surprising - eye-opening revelations. Those “MY LIFE HAS BEEN A LIE” moments. Never be afraid of disagreeing with your past opinions - it’s a sign of learning.

Some great resources:

On the illusion of pain, and how the perception of context guides belief: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-3NmTE-fJSo

On humans as slightly wonky bipedal brain machines: Kluge - The haphazard evolution of the human mind, Gary Marcus

#yanni#laurel#green needle#brainstorm#illusion#truth#trump#politics#objectivity#philosophy#psychology#mcgurk#what do you hear#original#snaprevise

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Placoid Scale

Placoid scales are the tiny tough scales that cover the skin of sharks, rays, and other elasmobranchs. Even though placoid scales are similar to the scales of bony fish, they are modified teeth and are covered with a hard enamel. They grow out of the dermis layer and this is why they are called dermal denticles.

Take a look at this cool infographic on scale types.

266 notes

·

View notes

Photo

oooohweee

Biology: Mold timelapse

Source: Lariontsev on YT

695 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tsunami drives species ‘army’ across Pacific to US coast

Scientists have detected hundreds of Japanese marine species on US coasts, swept across the Pacific by the deadly 2011 tsunami.

Mussels, starfish and dozens of other creatures great and small travelled across the waters, often on pieces of plastic debris.

Researchers were surprised that so many survived the long crossing, with new species still washing up in 2017.

The study is published in the journal Science.

378 notes

·

View notes

Text

Critical Thinking In Practice: The Sweetest Poison of All

“There’s about 40g sugar in that. Weren’t you meant to be going healthy this week?”

“Yeah but it doesn’t contain any refined sugars. That’s the nasty stuff that you want to avoid.”

“You’re still 10g over the recommended daily intake of sugars.”

“But it’s not refined sugar. You clearly don’t know what you’re talking about. I Googled it. I’ll send you the link.”

I read the article that evening, but we never spoke about sugar again. A pity, because the garbage Charlie was citing to support his argument was an absolute shocker. It’s the kind that uses pseudo-biological language and half-arsed logic that superficially sounds like it’s making a great point but doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. If you’ve done GCSE or A Level biology, you’re in a good position to pick it apart. It was the first search result for “refined sugar” in 2015 but has thankfully since dropped down the list.

Nevertheless I managed to find it again, and thought it could be helpful to scribble my thoughts in the margin to illustrate the kind of thinking I do when I read. It’s especially important to get into the habit of not just reading about things for interviews/life, but also actively engaging with the texts you’re looking at. Ask questions - that’s how you learn more about a topic. Challenge, even if the source sounds/is authoritative. You’re allowed to have opinions. Authors can make mistakes. I’ll be doing some more of these analyses as time goes on, but I thought this was quite an entertaining and obvious one to start with.

Click this to see my thoughts on the article. (Sorry, the JPEG doesn’t load properly when I include it in the body of the article, so I’ve had to make do with a link to the PDF.) This isn’t the full article, by the way: I only got a few paragraphs in before rage-quitting.

I think in this era of “alternative facts” and webs of lies it’s easy to cling to “science” as some monolithic source of truth. But the reality is, as this annotated document shows, science is only as truthful as its practitioners and interpreters. I think it’s important to get your head around the fact that science is a very human endeavour and that all scientific documents require just as much critical thought as, for example, historical ones. Don’t be lulled into a false sense of security because you see words like ‘pyruvic acid’ and ‘enzyme’, or science loses its driving force: critical thinking.

Charlie wasn’t stupid. He just mistook science for truth, when the former can only give a reliable estimate of the latter. He could have avoided looking like a tit by simply not taking the article for granted. To plagiarise my own tweets to the Dalai Lama, who once made the same error as Charlie:

Science isn’t infallible. To hold it as anything other than organised common sense/experience is dangerous. I’m not sure science can dictate values nor instruct, or we’d be eradicating the human race. All science can do is provide evidence.

It’s up to us how we interpret it.

And with that power comes great responsibility.

#a levels#biology#sugar#clean eating#reading#oxford#cambridge#oxbridge#interview#admissions#university#russell group#raw sugar#cane sugar#refined sugar#healthy eating#health#sucrose

0 notes

Text

Oxbridge Interviews: 3 ways to improve your Long Game

Preparing for interviews is a process that scares many people. From personal experience this is because there are no set guidelines on how to prepare, and the kinds of questions you might be asked in an interview are generally kept under lock and key. What a lot of people overlook however is the true function of interviews: they allow academics to identify candidates they want to teach over the next three or so years. So they’re not just looking for people who are bright, but also curious, hard working, pleasant and who thirst to learn.

So how do you make yourself stand out? Interview prep isn’t easy, nor is it quick, and definitely don’t expect it to be painless. Conceptually it’s helpful to split it into two parts, the same way you would in golf. You have your Long Game, and your Short Game. The Long Game for me started about 3 weeks before my interviews, but many will begin way before that. It’s up to you really, and how prepared you need to be to feel comfortable - there’s no shame in starting years in advance. The point of the Long Game is to get you to be well-read in your subject, and free your mind so it’s agile enough to navigate those all-important conversations when they’re eventually due. As someone who’s been through the wringer, here’s what I found helped me the most:

1. Make sure you know your shit.

Don’t cast your A Level material aside in order to learn new wacky things. If you can’t show an ability to recall fundamental information, you’re not going to give the impression that you’re going to do well at A Level, let alone survive a degree at Oxbridge.

This includes knowing the details of your personal statement too. If you’re going to drop names, do your research. They might ask you about that book you read. Hell, they might have even helped the guy write it. It would be good to have some opinions ready, and don’t be afraid to disagree with published authors.

2. Find something that interests you, and allow that interest to push you to pursue new knowledge.

This is probably the most difficult part, and something you’ll do well to get ahead in before writing your personal statement. It’s difficult to know where to start, so I’m peppering my blog with a number of curiosities that I’ve scoured out. Hopefully by having a read you might find something that grabs your attention.

It’s really important that once this happens, you don’t just learn these facts by heart. Turn your attention to asking questions - after all, this is the basis of all science. How does it work? Does it always behave this way? What’s the evidence? Is this evidence valid? If this is true, what are the implications in a wider context? Hopefully you can find a question that hasn’t been answered yet, and you could even have a go at designing your own experiment. It’s also totally true that the more you read, the more likely it will be that you’d have encountered an interview question before (in which case you should pretend you’ve never seen it before and that you’re some kind of genius).

3. Practice thinking.

You’re going to have all kinds of balls thrown at you hard and fast. If you’re good, you’ll catch most of them. If you’re outstanding, you’ll catch all of them, and the curveballs, set them on fire, find a blindfold and juggle. But nobody pops out of the womb catching balls. The trick is to practice. But you can easily set yourself apart if you practice practice practice. Ask yourself questions and before Googling the answers have a good crack at trying to figure them out yourself. The trick is to find your own methodology. I personally find that any question can be split up into a series of shorter, more precise questions that are easier to answer. Why is the sky blue? Well, define what you mean by ‘blue’ and ‘sky’ and we’ll go from there. Allow this to trickle into how you eventually conduct yourself in the interview. Ask good questions and you’ll be remembered.

This practice isn’t only going to put you in good stead to answer their questions, but it’s also going to make you a more interesting candidate because thinking will give you opinions. Everything is about opinions, up to and including science. Practice generating and justifying them.

Above all, don’t panic just yet. Nerves are inevitable closer to the time, but we’ll deal with your Short Game another day.

#oxbridge#interviews#cambridge#oxford#admissions#university#job#application#ucas#harvard#ivy league#Russell Group#snaprevise

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Fran, I just wanted to say that I really admire your blog and I just read your piece on the Education System and I just thought that it was so well-written and raised some really interesting points! Thank you for all the free help you give to me and all the other students out there, I certainly really appreciate your drive and commitment, I'm sure it must be quite time consuming. Thanks once again!

Hey, thank you so much! I’m more than happy to help - sorry I’m not posting more often (though I do have a piece on uni admission interviews on the way...) glad you’re enjoying my stuff :)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Actual photo of me just after my first Cambridge interview.

232 notes

·

View notes

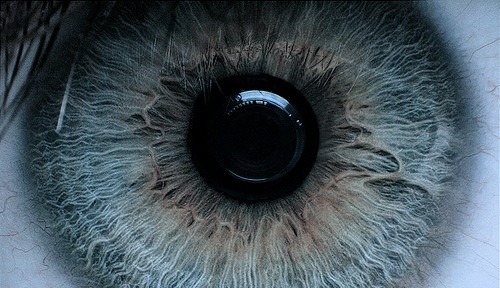

Photo

I like closeups.

Also blue eyes don’t actually have a set colour - the ‘blue’ we see is actually a result of all the light hitting the iris getting reflected back into the atmosphere. It’s scattered, as per the Tyndall effect, and we interpret the resulting colour as blue, which changes depending on the amount of light hitting the iris at the time of viewing.

[read it to believe it]

3M notes

·

View notes

Photo

That’s an albino tiger on the right.

It’s unstriped too, which mostly comes about because of inbreeding. This can also (presumably through genetic linkage, but don’t quote me on that) result in the fact that all white tigers become cross-eyed when stressed.

52K notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is even more interesting on a molecular level: the transparency occurs as a result of randomly arranged nanostructures within the wing. Chaos is difficult to find within biological structures, but this species bucks the trend in order to evade predators and is also paving the way for developing water-repellent technology.

Read more at https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms7909.

The Glasswing Butterfly (Greta oto) has transparent wings that span 2.2 - 2.4 inches. These butterflies are native to Central and South America.

4K notes

·

View notes

Link

An incredible resource for any A Level biologists out there. A collection of past paper exam questions organised by topic. If you’re doing OCR this will be especially helpful, but if you’re just looking to test your understanding or practice recall, this is gold.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Education Market

It was the 19th December, 2013. I walked out of Corpus Christi College in the dark, alone, and for the last time. For fuck’s sake – I’d said that bacteria replicate by mitosis. Rookie error - they had scoffed at me. I had been so nervous I could hardly speak, and failed to draw a simple molecule I’d mentioned in my personal statement. To make matters worse I was the very last kid the college had interviewed, so surely they had a handful of good candidates already by the time they had gotten round to interrogating me: a fumbling, clumsy girl who had tripped on the stairs while being escorted to her interviews. I was the dregs of a sparkling pint. Nobody wants that: goodbye future.

Three years, a generous helping of crippling mental health issues, a horrible term wasted on a (now) ex-boyfriend and a good run-in with addiction later, and against all odds I had a 2:1 from Cambridge. Never would a naïve 18 year old me, shattered and fragile from my interviews, thought that this was possible.

But then again, it was pretty inevitable. I had been schooled at Westminster, which for those of you out of the loop is one of the top public schools in the country. Fees were extortionate – my parents sacrificed almost everything to ensure I had the best start in life, and for that I will be forever grateful. It will remain one of the most enlightening experiences I’ve had, where students were encouraged to interrogate their dedicated, highly educated teachers in order to glean further insight through rounds of verbal sparring. Having come from another private school where I had sailed through GCSE’s with little effort, I held a steady level of mediocracy among my Westminster peers who had been there since the age of 13. They were a formidable bunch: talented, sharp and incredibly high-scoring despite their terrible work ethic. Out of a year of 120, 100 applied to Oxbridge. 70 got in.

This is not a luxury everyone can afford.

The educational system is a commercial marketplace, the quality of whose products are driven by competition between schools for the highest paying sectors of the same nationwide pool of consumers. These consumers are you, dear student. Each year a new wave arrives, acknowledging the necessity of literacy and articulation, willing to pay with at least their time, if not their hard-earned money to learn such privileges. These are, after all, the weapons which will help you navigate the shit-filled wasteland that is adult life. From the viewpoint of these educational institutions, there truly are always more fish in the sea. And these fish are forced to swim into nets from day 1 of school all the way to A Level results day. As always in life, you get what you can afford to pay for. Sometimes you stumble across bargains: that one excellent physics teacher that finally explains electromagnetic theory in a way that actually makes sense, the English tutor that tells you the topics you'll most likely be examined on. Sometimes you just don't. Weeks go by during which staff can’t be arsed to get to work. Empty lessons. Academic drought. Get fucked, says the system.

All the while you edge closer to the final battle: university. This is the make-it or break-it, or so it is made to seem. Time for a couple of questions, which have probably been gnawing at you for a while (and if they haven’t, they will be soon):

How do I give myself the best shot at this whole uni thing?

What if I don't go? What am I going to miss out on?

The reality is intangible, but looming. The answer to the first is this: be good at thinking. This starts with learning how to think. The answer to the second is just as important (if you want a spoiler, the answer really depends on what you want out of life), but I don’t want to draw focus from the first by attempting to enlighten two equally complex discussions in the same article.

How do you think well? You can be born with it, or you can be taught. If you’re naturally bright, good for you. If not, you’re going to have to rely on external resources: books, articles, teachers. Now for an aside about the human condition: we don’t like uncertainty. In fact, we are so adverse to uncertainty that we tend to pay premiums to mitigate it – and the more uncertainty there is, the higher the premium. This is the very logic that insurers rely on to sell their products. This is also the same logic that allows private schools to exist, and for the best of the best to charge high fees. Instead of paying for the assurance that you won’t lose any value in assets if, for example, some asshole keys your car, you’re essentially paying into the educational system to secure a future. This might come in the form of passing your GCSEs, A Levels, or Oxbridge admissions tests. The latter is exactly the logic my parents clung so tightly to. As in all marketplaces, it is not in the interests of those that deliver the best products to be any more transparent about the whole ordeal. This opacity is how private schools wall off their educational resources and why they maintain their monopoly on university admissions, especially to those Russel Group universities – not to mention Oxbridge. This is the harsh truth. Accessibility to education is based on the girth of your wallet, not your drive, ambition, rigour, or academic merit. You’re unlikely to learn how to think for free.

This is not right.

Why? If greatness amounts to the sum of your ambition and having enough money to secure excellent education, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that some people are born great, and others have greatness thrust upon them. We can call these “privilege”, and “happening to be in the right place in the right time”, respectively. To move from a position of disadvantage to greatness, it seems, is a question of chance. The result? Social stagnancy.

Now we’ve defined the problem, it’s clear that moving forward, we have two options. Option 1: we can rant about it until we’re blue in the face and the government finally revolutionises the way in which education is delivered to society, which seems the preferred modus operandus of many. In reality this requires a number of miracles to work. For starters, we’ll need to have a competent government which cares enough about education to dedicate the huge resources required for this process. I’m not sure about you, but given our countless failings in recent years I’m not betting anything that this is going to happen. Moreover, a cheeky surprise Brexit has given us bigger fish to fry, so a nationwide discussion about education isn’t going to take the necessary forefront to drive any change just yet. Option 2: we can take matters into our own hands. With ever growing global connectivity this actually seems feasible - and this is the exact brainwave I had on a particularly boring train journey back from the SnapRevise offices.

All this leaves is to design this solution. Observation 1: It doesn’t take the world’s leading academics to provide you with the tools needed to access higher education. In fact, over my three years at Cambridge I’ve learnt that accomplished scientists, on the whole, tend to be kind of crappy teachers. I know for a fact that the same goes for other subjects. Observation 2: I have years of experience in teaching, including being a lead tutor for SnapRevise – and I’m not alone. Additionally I have had the privilege of 3 long years in the system. So I’m going to take the liberty of showing you the ropes.

So here it is: a site dedicated to making higher education more accessible. You’re going to get think-pieces, application guides, an interview question database and content that’s going to give you a feel for the kind of academic rigour expected of you at these institutions. Take it as an insider’s guide to getting in the water and keeping your head above it. You’re going to get translations of cutting-edge research articles into real-speak. A wealth of background information that those in better schools (i.e., past me) take for granted.

I’m gonna teach you how to think.

#oxbridge#a level results#a levels#university#future#education#cambridge#oxford#russel group#russell group#reading#mandate

5 notes

·

View notes