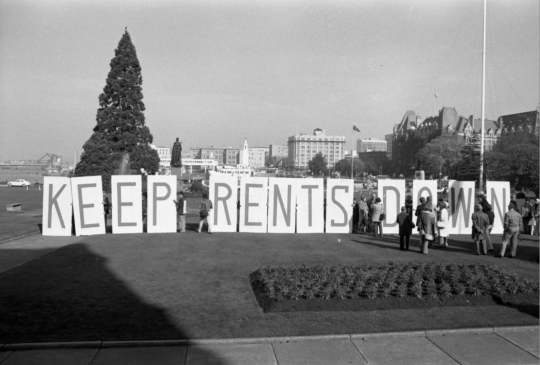

Photo

APEC Alert—an ‘Affair’ to remember

Text by Steph Glanzmann, Noni Nabors, and Marisa Pavone

Edited by Alexandra Bischoff and Anna Tidlund

In collaboration with UBC Geography Department’s Dr. Jessica Dempsey and her Fall 2017 GEOG 419 class, students were invited to submit archival based research for publication on the Both/And blog. The class thematic surrounded societal amnesia. Dempsey was interested in having students investigate major efforts for social change which had occurred in the past, the memories of which have not persisted in present social consciousness.

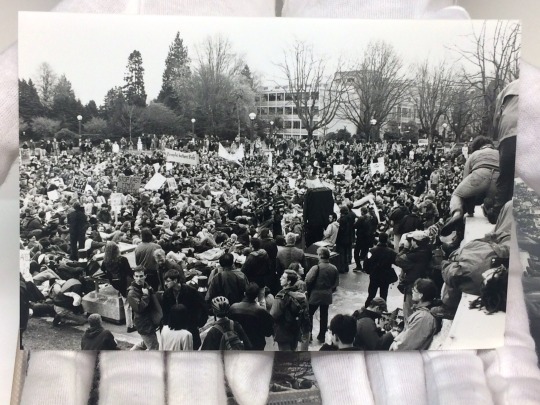

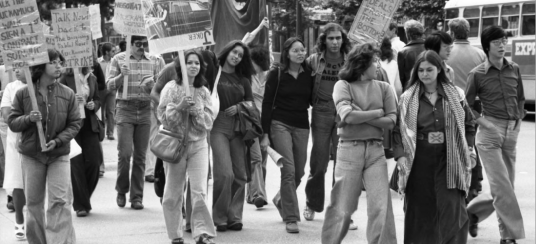

On November 25, 1997, anti-globalization activists at the University of British Columbia (UBC) Vancouver campus harnessed the attention of the nation during the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders’ Summit, in a protest that became known as the “APEC Affair”. APEC is an organization consisting of Pacific Rim countries seeking to promote free trade, economic cooperation, economic growth and prosperity among member states [1]. The APEC Affair garnered nation-wide media attention after local RCMP used pepper spray against nonviolent student protesters [2][3][4]. Unfortunately, the events that unfolded on November 25 (and the sequential court cases [5]) largely overshadowed the purpose of the anti-APEC campaign. This report intends to show how student organizers in opposition to APEC were able to engage and mobilize students on the UBC campus. With many of the organizers’ records and external communications accessible [6][7], we are able to analyze the principles, strategies and tactics used to mobilize the student body at UBC.

The APEC Affair occurred during a time of broader anti-globalization movements, which arose as a form of resistance to the widespread neoliberal policies being implemented around the globe [8]. The structural adjustments that came with globalization policies disproportionality impacted economies of Africa, Asia and Latin America and benefited those of the Global North [9], while simultaneously diluting democracy across borders and eroding workers rights around the world [10]. Other international bodies with similar neoliberal motivations include the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization, which both promote trade liberalization internationally [11].

In January 1997, outgoing UBC President Dr. David Strangway announced that the UBC Vancouver campus, including the Museum of Anthropology, would be the venue for the sixth annual APEC Leaders’ Summit. This would come to be the biggest and most expensive private meeting in Canada [12], with the intent of fostering economic partnerships between member states [13]. The decision was widely criticized for being outside Strangway’s scope of decision-making power, sparking anger among students who were not consulted about the decision [14][15]. Further to this, anti-APEC students and community members fundamentally opposed the meeting on the grounds that it was to be a meeting place to implement corporate globalization agendas [16]. The fall after the summit announcement, several students began organizing efforts against the APEC Leaders’ Summit and referred to themselves as “APEC Alert” [17].

APEC Alert “considered APEC to be undemocratic, complicit in the erosion of human rights . . . fostering a society of consumption, and promoters of environmental destruction” [18]. In resistance, APEC Alert created a powerful campaign that included diverse tactics and messaging, which resonated with a large student base. Approximately 1,500 individuals protested in opposition to the APEC summit [19][20]. Protesters were concerned that the APEC summit would be focused on trade agreements without considering the human rights abuses of Indonesia President Suharto and Chinese General Secretary Zemin, as well as the environmental and social ills of the trade deals [21][22]. Although the protest itself was peaceful, 48 students were detained and multiple individuals were pepper sprayed by police [23][24].

Organizing materials and threads of communication used to mobilize UBC campus have been preserved through email lists, news articles, and local archives, but there has been little work to re-centre this story of student resistance to the conscious of the UBC community. By threading together primary sources, first-hand accounts and anti-APEC material, we seek to create a roadmap for future student organizers and to distribute the story of a meaningful student-led movement on UBC campus. By framing the voices of APEC-Alert organizers and protestors, our work serves to counterbalance the largely institutional and legalist research already done on the APEC Affair.

We visited the UBC Alma Mater Society (AMS), Museum of Anthropology (MOA) and Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery archives, looking at collections both online and in-person. When visiting the AMS and MOA archives, we focused on student-generated content such as leaflets, posters, event itineraries and email communications. Archival sources included a Vancouver-wide anarchist email list used to coordinate events and as well as circulate alternative media. This list, which included over 24 threads containing the term “APEC” in their titles, acts as the backbone of our research as we used it to piece together the larger organizing process and identify key members of APEC Alert [25].

We compiled a list of potential interviewees and, ultimately, interviewed four individuals: Garth Mullins, a writer based in East Vancouver; Jonathan Oppenheim, a former UBC student and APEC Alert organizer; Katja-Anton Cronauer, also a former UBC student and APEC Alert organizer; and Jamie Doucette, a former UBC student and activist taken into custody during the APEC Affair.

These interviews revealed many aspects of the APEC Affair and the campus culture of 1997. For one, the success of the APEC Affair is largely credited to the diverse tactics used by organizers in mobilizing 1,500 protesters. Organizers were able to foster a successful movement on campus because of the diverse tactics they used to activate the student body. APEC Alert split their campaign into three sections: “Refuse APEC,” “Summit Under Siege,” and “Crash The Summit” [26].

Refuse APEC spanned from the beginning of September to November 17, 1997 [27]. This period involved a series of acts of civil disobedience that engaged students as well as created situations which forced UBC administration to act. When asked about the strengths of APEC Alert’s campaign, past member Jonathan Oppenheim said, “[protesters were] effective at creating situations where we put both the university and the state . . . at a loss of what to do. We were quite good at creating situations where they were kind of forced to choose. [We pushed] them in situations they were uncomfortable with” [28]. Examples of these situations include camping at the Museum of Anthropology and the AMS Student Union Building, tabling motions for both the AMS and the UBC Board of Governors to overturn the decision to host the Summit [29], a series of road hockey games on the driveway of the Norman Mackenzie house [30] and a Halloween campus march that ended with two student being detained for writing “BOO APEC” on a newly renovated building [31]. The Refuse APEC period was also used to educate the student body through both informational and provocative posters, debates on campus, classroom announcements, film screenings and talks.

The next phase, Summit Under Siege, was a transition point in the campaign where organizers ramped up the intensity and size of anti-APEC demonstrations in preparation for the beginning of summit proceedings on November 19. Summit Under Siege began on November 17 with a tent city outside of the AMS Student Union Building (SUB) called Democracy Village, or DemoVille for short, which lasted until November 25 [32]. Other UBC student groups were encouraged to show their support by setting up a tent in DemoVille and to participate in the ongoing civil disobedience trainings, cook-outs and workshops. On November 21, APEC Alert held a concert next to the restricted area of the Museum of Anthropology called “Rock Against APEC” [33]. On November 24—the day before the Leaders’ Summit—APEC Alert organized a campus wide walk-out, directing students, faculty and Vancouver supporters to a day-long teach-in called “Free University” in the SUB.

Summit Under Siege culminated with the final phase of the campaign: Crash The Summit. On the morning of November 25, 1997, protesters were invited to gather at the Goddess of Democracy statue for a “Refuse APEC Festival”, which included street theatre, music, speeches and civil disobedience preparation [34]. Over 1,500 protesters marched throughout campus in opposition to the Leaders Summit, eventually clashing with police, finding themselves on the receiving end of pepper spray and excessive force [35][36].

Our interviewees spoke of the necessity of mixed-methods organizing, emphasizing that any movement will not succeed without them. Katja-Anton Cronauer recalled [37]:

What I liked was that it was very varied—our strategies. We employed our educations, had workshops, showed films, invited presenters for talks, plastered the campus with posters, did civil disobedience actions, beautified the campus—as we called it—with chalk and paint and posters. So I liked that because it drew a lot of different people in.

During the APEC Affair there were events tailored for those with deep, academic knowledge of power systems and international affairs, as well as events for those less familiar. Garth Mullins remembers thinking, “this is great, are you kidding me? We’ve like broken through to the Zeitgeist or whatever, because the truth is [UBC] . . . was not a hotbed of radicalism” [38].

People were made to feel welcome through these tactics regardless of how much they knew when they arrived at an event. In this way a welcoming atmosphere was created, and increased awareness about APEC attracted more individuals to the events who were curious. The multitude of events leading up to the summit generated momentum for the main protest, Crash The Summit.

The gender dynamics in APEC Alert are also worth considering. While APEC Alert centered anti-oppression and consensus as guiding principles in their organizing, in our research it was clear that certain identities and voices were missing from conversations while others dominated. Cronauer’s thesis, for example, suggests that women and non-binary individuals were underrepresented in APEC Alert email exchanges [39]. Furthermore in our interview, Cronauer spoke of a “boy’s club” within APEC Alert that implicitly excluded women and non-binary members. According to Cronauer, there “was difference among groups. There was a boys club, [ . . . and] there was a core group which I was a part of, which was the next inner group” [40].

Cronauer later went on to say that following the Summit, a group of female organizers created a women’s only group to discuss the sexism they faced both from police and from within APEC Alert [41]. Seven out of eight persons we contacted for interviews identify as cis-male. It is not immediately clear whether this is because the archive selectively overrepresents male voices and/or whether women and non-binary individuals were excluded from organizing.

In addition to the gender power dynamics, Cronauer recounted how APEC Alert was predominately white, a fact she believes influenced their activities. Cronauer recalls that “using [tactics] like ‘Hockey Against APEC’ —which as I know is a very white Canadian game,” could have been a subtle form of exclusion [42]. In fact all our interviewees are white, something we realized only at the conclusion of our interviews.

It is impossible to say what the specific impacts of a predominately white and male organizing leadership are, especially within the scope of this report. Regardless, it calls to attention critical questions of power structures within justice-oriented organizing groups. Who has the ability to be speak, and to be heard, as well as whose voice is represented in archival histories are crucial and power-laden questions.

Our interviewees stressed that, up until the day of the summit, they could not have predicted whether Crash The Summit would be “successful” or not. There is no benchmark for “success” in such movements, so describing it as such is fickle. They emphasized that, rather than focusing on the “success” of events, aspiring organizers must keep an eye on their long-term goals. As Katja-Anton Cronauer said, “I think one important thing is: keep going” [43].

The APEC Affair occurred 20 years ago and yet we suspect the majority of students on UBC campus are unaware of it. We believe there is still a need for student movements today, including the movement to divest UBC from fossil fuels, which stem from the same neoliberal forces the anti-APEC movement rallied against. It is ironic that 20 years ago UBC students protested against the widespread implementation of neoliberal policies, while students today are affected by the consequences of those policies—yet are unaware of the efforts of the students before them. We encourage future research into the connection between this lack of memory, and the student body’s perceptions of social action on campus today.

Notes

[1] Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. "Mission Statement." Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Accessed April 12, 2017. http://www.apec.org/About-Us/About-APEC/Mission-Statement.

[2] Winter, James. "Canadian PM in hot water over APEC '97." Green Left Weekly. September 5, 2016. Accessed June 21, 2017. https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/canadian-pm-hot-water-over-apec-97.

[3] Pue, W. Wesley. Pepper in our eyes: the APEC affair. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000.

[4] Abbate, Gay. "Mounties assailed for APEC bungling." The Globe and Mail. March 21, 2009. Web. Accessed June 21, 2017. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/mounties-assailed-for-apec-bungling/article1032642/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Cronauer, Katja-Anton. "Activism and the Internet: a socio-political analysis of how the use of electronic mailing lists affects mobilization in social movement organizations." PhD diss., University of British Columbia, April 2004.

[7] A-Infos News Services: News about and of interest to anarchists. Accessed April 12, 2017. http://www.ainfos.ca/A-Infos97/4/index.html#545.

[8] Ericson, Richard and Aaron Doyle. "Globalization and the policing of protest: the case of APEC 1997." British Journal of Sociology 50, no. 4 (1999): 589-608. Accessed June 21, 2017. doi:10.1080/000713199358554.

[9] Redclift, Michael and Colin Sage. "Global Environmental Change and Global Inequality." International Sociology 13, No. 4 (1998): 499-516. Accessed June 21, 2017. doi:10.1177/026858098013004005.

[10] Biebricher, Thomas. "Neoliberalism and Democracy," Constellations 22, No. 2 (2015): 255-266. Accessed April 12, 2017, doi:10.1111/1467-8675.12157.

[11] Chorev, Nitsan and Sarah Babb. "The crisis of neoliberalism and the future of international institutions: A comparison of the IMF and the WTO." Theory and Society 38, No. 5 (2009): 459-84. doi:10.1007/s11186-009-9093-5.

[12] Mackin, Bob and Geoff Dembicki. "Mercer Blasted APEC Protesters with Pepper Spray." The Tyee. Web. October 22, 2009. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://thetyee.ca/News/2009/10/22/MercerPepperSpray/.

[13] Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. "Mission Statement." Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Accessed April 12, 2017. http://www.apec.org/About-Us/About-APEC/Mission-Statement.

[14] Clark, J. "APEC Economic Summit." The Ubyssey (Vancouver): 3. January 10, 1997. Vol 78 Iss 24. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubcpublications/ubysseynews/items/1.0127434.

[15] Cronauer, Katja-Anton and Nicole Capler. "APEC-Alert voices views." UBC News: News from the University of British Columbia. July 10, 1997. Web. Accessed April 14, 2017. http://news.ubc.ca/ubcreports/1997/97sep04/97sep4let.html.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Mackin, Bob and Geoff Dembicki. "Mercer Blasted APEC Protesters with Pepper Spray." The Tyee. October 22, 2009. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://thetyee.ca/News/2009/10/22/MercerPepperSpray/.

[18] Doyle, Alan. “B.C. Civil Liberties Association - APEC Inquiry fonds,” December 2002, last revised September 2010. Finding aid at the University of British Columbia Archives, Vancouver, BC. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/bc_civil_liberties_association.pdf.

[19] Nuttal-Smith, Chris and Sarah Galashan. “APEC slams UBC.” The Ubyssey (Vancouver): 1. November 28, 1997. Vol 72 Iss 23. Web. Accessed June 7, 2017. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubcpublications/ubysseynews/items/1.0126666#p0z-2r0f.

[20] Doyle, Alan. “B.C. Civil Liberties Association - APEC Inquiry fonds,” December 2002, last revised September 2010. Finding aid at the University of British Columbia Archives, Vancouver, BC. Doyle, A. 2002. B.C. Civil Liberties Association - APEC Inquiry fonds. UBC Archives. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/bc_civil_liberties_association.pdf.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Cronauer, Katja-Anton and Nicole Capler. "APEC-Alert voices views." UBC News: News from the University of British Columbia. July 10, 1997. Web. Accessed April 14, 2017. http://news.ubc.ca/ubcreports/1997/97sep04/97sep4let.html.

[23] Pecho, J. “APEC Inquiry Collection (various collectors),” 2008. Finding aid at the University of British Columbia Archives, Vancouver, BC. Accessed April 12, 2017. http://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/apec_coll.pdf.

[24] Bradley, Nicholas, and Daliah Merzaban. “APEC remembered: two years later.” The Ubyssey (Vancouver): 1-2. November 23, 1999. Vol 81 Iss 20. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubcpublications/ubysseynews/items/1.0128705#p0z-2r0f.

[25] A-Infos News Services: News about and of interest to anarchists. Accessed April 12, 2017. http://www.ainfos.ca/A-Infos97/4/index.html#545.

[26] Oppenheim, Jonathan. "(en) Summit Under Siege!" Forum post. A-Infos News Services: News about and of interest to anarchists. October 30, 1997. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. www.ainfos.ca/A-Infos97/4/0320.html.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Oppenheim, Jonathan. "Questions on APEC Alert." Online interview by Steph Glanzmann. March 9, 2017.

[29] Bradley, Nicholas, and Daliah Merzaban. “APEC remembered: two years later.” The Ubyssey (Vancouver): 1-2. November 23, 1999. Vol 81 Iss 20. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubcpublications/ubysseynews/items/1.0128705#p0z-2r0f.

[30] APEC Alert. "UBC PRESDIENT WANTS THE ARREST OF STUDENTS FOR PLAYING ROAD HOCKEY." [sic] British Columbia Anarchist Association. Geocities, October 29, 1997. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. http://www.geocities.ws/CapitolHill/6322/apec.htm.

[31] The Ubyssey. "The Circus Comes to Campus." The Ubyssey (Vancouver): 10. November 4, 1997. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubcpublications/ubysseynews/items/1.0127649#p8z-6r0f:halleen%20APEC.

[32] Howe, Brendan. "B.C. APEC Protest." UWO Gazette (London, ON). November 21, 1997. Vol 91 Iss 48. University of Western Ontario. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. http://www.usc.uwo.ca/gazette/1997/November/21/News3.htm.

[33] Oppenheim, Jonathan. "(en) Summit Under Siege!" Forum post. A-Infos News Services: News about and of interest to anarchists. October 30, 1997. Web. Accessed April 12, 2017. www.ainfos.ca/A-Infos97/4/0320.html.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Douglas Quan, “Necessary force: Students accuse police of brutality”. The Ubyssey (Vancouver): 1. Vol 79 Iss 23. 28 November 1997. Web. Accessed 8 June 2017. https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubcpublications/ubysseynews/items/1.0126666#p0z-5r0f:necessary%20force:%20Students%20accuse%20police%20of%20brutality

[36] Alan Doyle. “B.C. Civil Liberties Association - APEC Inquiry fonds,” December 2002, last revised September 2010. Finding aid at the University of British Columbia Archives, Vancouver, BC. Doyle, A. 2002. B.C. Civil Liberties Association - APEC Inquiry fonds. UBC Archives. Accessed April 12, 2017. https://www.library.ubc.ca/archives/u_arch/bc_civil_liberties_association.pdf.

[37] Kajta-Anton Cronauer. "Questions on APEC Alert." Online interview by Steph Glanzmann and Noni Nabors. March 23, 2017.

[38] Garth Mullins. "Questions on APEC Alert." Interview by Noni Nabors. March 15, 2017.

[39] Cronauer’s “Activism and the Internet: A socio-political analysis of how the use of mailing lists affects mobilization in social movement organizations” (2004) discovered that from the APEC-Alert email list 72 messages were sent by women, 266 were sent by men, and 17 were sent by individuals whose gender is unknown.

[40] Kajta-Anton Cronauer. "Questions on APEC Alert." Online interview by Steph Glanzmann and Noni Nabors. March 23, 2017.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

Images

APEC protesters gathering outside the Walter C. Koerner Library at the University of British Columbia in November 1997. Photograph by Todd Tubutis. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) collection, series 6, box 3, file 6-9. Courtesy of UBC Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver, Canada.

Police presence at the University of British Columbia in November 1997. Photograph by Maria Roth. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) collection, series 6, box 3, file 6-1. Courtesy of UBC Museum of Anthropology.

Demoville Tent City outside the old Student Union Building at the University of British Columbia in November 1997. Photograph by Todd Tubutis. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) collection, series 6, box 3, file 6-9. Courtesy of UBC Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver, Canada.

APEC protesters gathering outside the Walter C. Koerner Library at the University of British Columbia in November 1997. Photograph by Todd Tubutis. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) collection, series 6, box 3, file 6-9. Courtesy of UBC Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver, Canada.

APEC protesters gathering outside the Walter C. Koerner Library at the University of British Columbia in November 1997. Photograph by Todd Tubutis. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) collection, series 6, box 3, file 6-9. Courtesy of UBC Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver, Canada.

#APEC Alert#campus politics#UBC#university of British columbia#uni-poli#student activism#pepper spray#peaceful protest#anti-globalization politics#APEC#Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation#bcpoli#bc politics

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What are Archives and what can we do with them?

“Archives have the capacity to produce and reproduce social justice and injustice through their constructions of the past, engagements in the present, and shaping of possible futures” - Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor [1]

The word “archive” has many meanings. Archive(s) can refer to a place, a repository where records are kept. Archives can refer to material, historical documents, personal and community belongings. To archive can be a verb, used to describe the transfer of records. Archives can refer to computer data. They can come in any shape or form and contain records of past actions so that we may reference them in the future. The concepts and definitions of “record” are constantly challenged and debated even within the archival profession.

Terry Eastwood states “the roots of archival theory may be traced to certain ancient legal and administrative principles. In order to conduct affairs, and in the course of conducting affairs, certain documents are created to capture the facts of the matter of action for future reference, to extend memory of deeds and actions of all kinds, to make it enduring” [2]. Archives can be considered monuments to the past because records were produced by specific entities during their activities under certain conditions. They can therefore attest to those recorded “acts” and “facts”. It is because archives provide an unbroken chain of custody, in a protected setting where corruption or falsification is difficult, that they can be deemed trustworthy and reliable.

The concept of archives and records being trustworthy and reliable is deeply important for the idea of evidence and the demonstration of accountability. We can hold people, corporations, and governments to account by exercising our right to view information produced by them to confirm that they act how they purport to act. This can be an important tool in rendering social justice, exercising rights, and maintaining fiduciary trust. We can see how people, corporations, and governments deny transparency by destroying, restricting, or simply not producing their records. We see this in the BC government’s intentional deletion of emails relating to the Highway of Tears, the US government’s unethical disregard for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s treaty rights spelled out by the Fort Laramie Treaty, the memorandum released by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) of the US stating that the records produced by the then President-elect’s Transition Team (PETT) will be considered private and restricted instead of being publicly available as they usually are [3][4][5].

Archives as evidence can have powerful outcomes for those who utilize them in legal affairs. But, the conceptual stillness of archives as evidence does not always represent the truth or at least not the whole truth. Documentary truths are not all truths. A document that is accurate, as in, it is produced by and when it says it was created, does not mean it resides outside of the realm of human processes and intentions. Rather, it is an indication of those human processes and intentions. Archives can promote social justice and injustice, sometimes simultaneously.

Archives are contingent on the nature of their creation, preservation, and dissemination. The criteria determining each set of actions and procedures is inherently historical, cultural, and political. Verne Harris writes, “an archive is a sliver of a sliver of a sliver of a window of a process” [6]. No archive preserves all the records of everyone, leading to inherent omissions from the public record and raising questions about who gets to decide what shall be saved.

Archives are select records decidedly put aside for future reference - a very small sliver of a complex result of context, narratives, and production. Rodney Carter writes “archival power is, in part, the power to allow voices to be heard… The power of the archive is witnessed in the act of inclusion… (but also) the power to exclude. Inevitably, there are distortions, omissions, erasures, and silences in the archive. Not every story is told” [7].

Community archives are an extremely important infrastructure and public service to the community it serves and more. When large or institutional archives fail to represent communities who are marginalized by race, class, sexuality, gender, and politics, communities themselves will often create their own archives outside the boundaries of the formalized institution. Often, with the grassroots labor of devoted volunteers and limited staff. These valuable community archives come in many forms and can counteract the way their community is represented by the mainstream archival, historical, political, and social discourse. Communities can include artist-run centres, LGBTQ+ initiatives, racialized peoples, independent collectors with specialized interests, religious centres, geographic and/or rural communities, cultural associations, political and activist movements, and survivors of atrocities. Creating an archive can then become a political and reflexive act; by constantly repositioning collecting and descriptive strategies with the needs of the community in mind, archives can be used as a means to empower and construct one’s own identity.

Archives themselves are not necessarily powerful, it is how they are created, used, and received by people that is powerful. They are meaningful extensions of human interactions that allow or deny histories and futures. Archives should be “activated” by being used, promoted, and questioned.

Text

Anna Tidlund

Notes/Sources

[1] Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor, “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives”, Archivaria 81, Spring (2016): p. 26.

[2] Terry Eastwood,”What is Archival Theory and Why is it Important?”, Archivaria 37, Spring (1994): p. 125.

[3] The BC Liberals staffer, George Steven Gretes, was fired and charged with wilfully making false statements to mislead, or attempting to mislead, under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. The crime led to the publication of Investigation Report F15-03 Access Denied: Record Retention and Disposal Practices of the Government of British Columbia that champions for The Duty to Document. The investigation was lead by Elizabeth Denham, Information and Privacy Commissioner for BC (now the Information Commissioner of the UK).

[4] In 1851 the (colonial) Treaty of Fort Laramie “legally” asserted that Standing Rock Sioux Tribe owned land, including the land west of the Missouri river. Shortly after the Treaty was signed, white settlers began to encroach further on Indigenous lands, sanctioned by the US Government without tribal approval. This disregard for Indigenous peoples and their rightful ownership to land was further provoked in 2016, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers granted authorization to the Dakota Access Pipeline without tribal consultation.

[5] On November 16, 2016 the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) issued public memorandum AC09.2017 stating that the Donald Trump’s (then) President-elect Transition Team (PETT) would not be considered Federal or Presidential records, but private materials. The result is that NARA is not required to collect or preserve records created by the PETT, denying access to these records for future reference.

[6] Verne Harris, “The Archival Sliver: Power, Memory, and Archives in South Africa”, Archival Science 2, (2002): p. 84.

[7] Rodney Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence”, Archivaria 61, Spring (2006): p. 216.

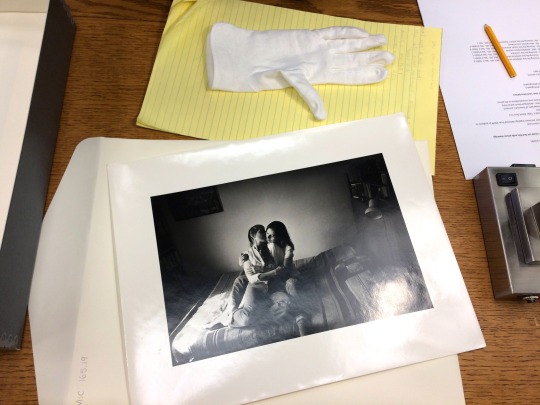

Image

Photo by Anna Tidlund, taken at the Western Front’s Videotape Archive (2016).

0 notes

Photo

“A PROVOCATIVE SPEECH” by Rosemary Brown

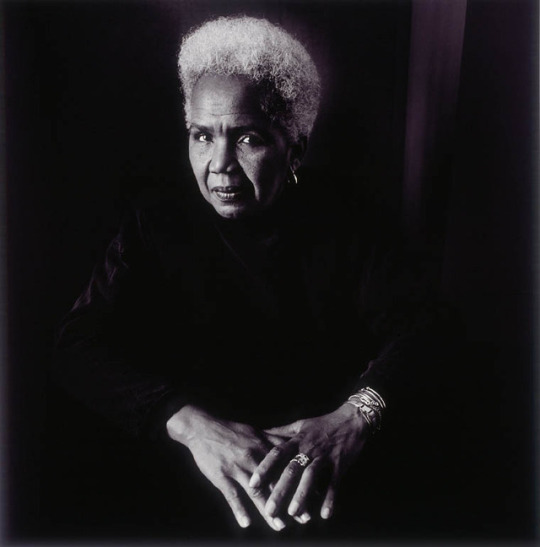

Rosemary Brown (b. 1930 Kingston, Jamaica), the first black woman appointed to a provincial legislature in Canadian history, was elected MLA of the Vancouver-Burrard riding in 1972. Three years later, Brown would make her bid to run as federal leader of the NDP party—another first for a black woman in Canada. Ed Broadbent went on to take the party’s helm, but Brown came in close at second place with 41+% of the votes on the fourth and final ballot [1].

A woman who once said that to “be black and female in a society that is both racist and sexist is to be in the unique position of having nowhere to go but up,” Brown consistently worked to deconstruct conventions of oppression [2]. Among other initiatives, Brown “formed a committee to eliminate sexism in school textbooks and curricula...was instrumental in introducing legislation to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex or marital status,” “was a founding member of the Vancouver Status of Women” and advocated tirelessly for people of colour in Canada [3][4][5].

She was also a popular speaker and a prolific writer. The UBC Rare Books and Special Collections archive hosts a number of files with original, typed speeches, all of which are passionate, insightful, and eerily prescient. With the 2017 provincial election on the horizon, one speech, given to the Alberta NDP party on May 7, 1976, feels particularly worth revisiting.

For context, 1976 was a year in which many of B.C.’s left-leaning voters were experiencing, what Brown called, “a widespread disillusionment” [6]. Four years prior in 1972, the New Democratic Party was elected as British Columbia’s provincial government for the first time since the party’s inception in 1933. This was a historical moment; the Social Credit Party had maintained control over the province for the last twenty years [7]. Despite the fact that the NDP had passed an extensive amount of progressive legislation during a short period of time, the run was short lived. NDP leadership lasted for a single three year term before returning to a Socred government in 1975.

Titled “A PROVOCATIVE SPEECH FOR ALBERTA NEW DEMOCRATS,” Brown’s speech addresses the swift return of B.C.’s conservative politics, the crisis of electoral disillusionment, the portentous death of capitalism (or at the very least, the incurable ailments of capitalism), and gives a critique of everyday life which suggests how to refute the aforementioned sources of despondency. Below are a few excerpts of this timely speech; the full transcript (for research use only) can be found here: https://goo.gl/9KxM8i [8].

A PROVOCATIVE SPEECH FOR ALBERTA NEW DEMOCRATS

On Alberta and British Columbia politics:

“It was not long ago that many Alberta New Democrats believed that the ‘grass was greener on the other side of the Rockies.’ The struggle for democratic socialism in Alberta seemed almost insurmountable in the face of the powerful oil corporation Tories…Many of you looked enviously at our NDP Government’s provisions for the elderly, at our willingness to assert the public stake in valuable mineral resources, forest products, and to preserve our scarce agricultural land…

Well, now we both know differently. The illusion has been shattered. The grass is not greener on the other side of the Rockies anymore.” [9]

On voter disillusionment:

“The illusion has been shattered.

The illusion that one successful election, one vigorous period of progressive legislation, can turn history around, can solidify and consolidate the aspirations of generations of socialists...But if illusions have been shattered, what has replaced those illusions may be even worse:

There is a widespread disillusionment, a feeling of despair, of cynical acceptance of what is, as being what must be. Of course on the Right this cynical disillusionment is almost welcomed as being a ‘liberating’ force, as a way of re-asserting the ‘good old days.’ A demoralized people is easier to divide, easier to coerce, easier to tempt with delusionary solutions. On the Left this mood is expressed in a pessimism, a fatalism about the chance of progress...This mood is more frightening than the ‘event’ of an electoral defeat.” [10]

On how to assess our complicitness in systems of capitalist oppression:

“We must look at our everyday conditions of existence and separate those aspects which really leave the quality of life untouched, those things which render life utterly banal…from those areas of life which have real quality, which make life worth living.

We must learn to recognize which of the supposed ‘benefits of the system’ serve real needs, and which only serve to oppress us…

We must assess our relation to the external world—and learn to separate real communication, real ideas, real events from mere side-shows and spectacles designed to blurr [sic] our vision…

We must investigate those aspects which break down social and political relationships, which tear us away from one andother [sic], which prevent us from struggling more effectively together…

We must recognize that the purposes of the capitalist system are not those of our own…

We must criticize our own ‘silence’, because this silence coincides with a fatalistic perspective which hinders action.” [11]

On strengthening socialism to strengthen reform:

“...it is clear that politics as opposed to parliaments develops outside legislative chambers, it develops in the needs, aspirations, struggles, and organizations of the people. Whatever our parliamentary goals, our political roots are out among the people.

Economic crisis, the capitalist crisis...cannot produce willy nilly a revolt. Capitalism has been ready for burial for a long long time. Cy Gonick tells us “a central fact of our own experience is the enormous strength and stability of civil society even when state pwoer [sic] momentarily falters.” It is not enough to know the system is breaking down. We need an alternative view, which challenges the totality of the existing structure...and that is not simply a matter of changing laws, and that is not found inside statute books.

Therefore I suggest that the NDP, political people, we cannot confine our struggle to electoral politics. We found in B.C. that merely legislative reforms did not make lasting changes or ensure re-election. Good legislation is not self sustaining. What we needed to do was to make good legislation defensible by the people—regardless of which party controlled the government legislation services. It is time for socialism to sink its roots more deeply into society, to find nourishment and support. When we do that, we will have the kind of policies and laws which cannot be so easily toppled, and that no government would dare to tamper with.” [12]

Upon retiring from politics in 1988, Brown continued her advocacy through organizations such as the MATCH International Women’s Fund—for which she was the CEO between 1988-91—and the Ontario Human Rights Commission of which she was named the chief commissioner in 1993. Among other national and international recognitions, Brown was the recipient of a total of 15 honorary doctorates from Canadian universities, the Order of British Columbia (1995), and the Order of Canada (Officer, 1996) [13]. Rosemary Brown passed away on April 26, 2003 in Vancouver, B.C..

Text

Introduction by Alexandra Bischoff

Speech excerpts by Rosemary Brown

Notes/Sources

[1] "Rosemary Brown (politician)." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 30 Apr. 2017. Web. 02 May 2017.

[2] Hume, Stephen. "Canada 150: Rosemary Brown, an Outspoken Pioneer for Women of Colour." Vancouver Sun. N.p., 05 Feb. 2017. Web. 02 May 2017.

[3] "ARCHIVED - Celebrating Women's Achievements (Rosemary Brown)." Library and Archives Canada. Government of Canada, 10 Oct. 2000. Web. 04 May 2017.

[4] Snyder, Lorraine. "Rosemary Brown." The Canadian Encyclopedia. N.d. Web. 02 May 2017.

[5] For an example, we recommend reading a speech Brown gave in September 1982 to the Association of Black Business Persons titled “Motivation of Young People.” UBC Rare Books Special Collections; Rosemary Brown fonds; reference code: RBSC-ARC-1077-35-7.

[6] “A PROVOCATIVE SPEECH FOR THE ALBERTA NEW DEMOCRATS.” UBC Rare Books Special Collections; Rosemary Brown fonds; reference code: RBSC-ARC-1077-35-6 Alberta NCP “Disillusionment” 7 May 1976. Quoted from page 4.

[7] "List of British Columbia General Elections." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 04 May 2017. Web. 03 May 2017.

[8] Courtesy of UBC Rare Books Special Collections; for research and reference purposes only. “A PROVOCATIVE SPEECH FOR THE ALBERTA NEW DEMOCRATS” by Rosemary Brown. UBC Rare Books Special Collections; Rosemary Brown fonds; reference code: RBSC-ARC-1077-35-6 Alberta NCP “Disillusionment” 7 May 1976.

[9] “A PROVOCATIVE SPEECH FOR THE ALBERTA NEW DEMOCRATS.” UBC Rare Books Special Collections; Rosemary Brown fonds; reference code: RBSC-ARC-1077-35-6 Alberta NCP “Disillusionment” 7 May 1976. Quoted from page 1.

[10] Ibid. Quoted from page 4.

[11] Ibid. Quoted from pages 14-16.

[12] Ibid. Quoted from pages 17-18.

[13] Snyder, Lorraine. "Rosemary Brown." The Canadian Encyclopedia. N.d. Web. 02 May 2017.

Image

Credit: Barbara Woodley, Labatt Breweries of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, 1993-234, PA-186871 Restrictions on use: compulsory mention: acquired with the assistance of a grant from the Minister of Communications under the terms of the Cultural Property Import & Export Review Act

#bcpoli#bc election 2017#rosemary brown#feminist politics#feminism#female leaders#black feminism#women in politics#bc politics

0 notes

Photo

Ron Dutton and the B.C. Gay and Lesbian Archives

The following is a brief profile on Ron Dutton, founder of the B.C. Gay and Lesbian Archives. On February 14, 2017, Alexandra Bischoff and Anna Tidlund visited Dutton to ask him a few questions about his archival process, and to see the massive holdings which the archivist has been collecting since 1976. All quotations are of Dutton from this initial interview.

The B.C. Gay and Lesbian Archives (BCGLA) is unlike most archival institutions. One of its most distinguishing features is that the archives are housed within the founder’s apartment in Vancouver’s West End. Files are meticulously boxed and stored in the apartment’s guest bedroom, so there is an immediate sense of warmth, comfort and refuge offered not only to the visiting researcher but also the documents themselves.

Ron Dutton, the magnanimous figure behind the project, welcomes interested parties into his home, sits down with them at his kitchen table, and works through the vague inquiries that people often begin their research with. He tells us that while he hosts researchers of all kinds, they usually fall under four categories: fact checkers from the media, academics from across North America, cultural workers looking for inspiration, or individuals creating personal projects about family members.

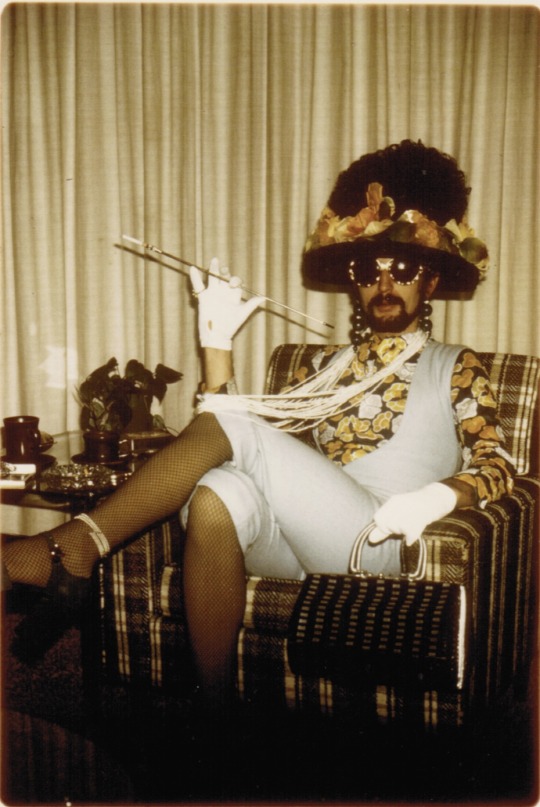

For forty-two years, Dutton has worked to collect ephemera of B.C.’s queer communities. I ask him what major events can be found in the archive, to which he replies, “everything. I don’t make assumptions that something is too trivial to be collected. I collect everything.” The archive covers, he elaborates, anything B.C. and queer community related. His collection of around 750,000 items includes books by B.C.’s queer authors, magazines, newspapers, the newsletters of queer organizations, small publications (“that you would never find on the internet”), event ephemera, personal diaries, photo albums, audio cassettes, CDs, VHSs and DVDs, posters of all sizes, and government reports—to name a few.

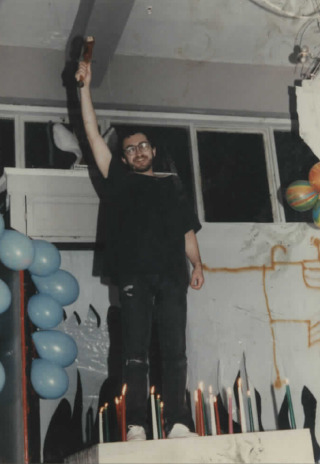

There are many hidden gems. Tucked in one section are over 100 VHS tapes of drag shows at the no-longer operating Dufferin Hotel. Dutton sets the scene: grainy video of the 1970s and 80s capturing a smoke filled bar, drunken commentary cutting through the audio of a bad sound system, mixed with pure, drag magic. These tapes document hours upon hours of renowned performers (like Wanda Fuca and, pictured below, Adrian Alexandria de Vander Vogue) showcasing some of their best material.

Dutton grew up in a small town in rural Alberta and went to the UofA for Library and Archival studies. The air in the 1970s, he recalls, was electric. According to Dutton, a fundamental difference between the 1970s and the 2000s is todays lack of optimism—or perhaps the overabundance of it in back then.

He notes that the broad theme of the 1960s belonged to “people who had been held down [by systems of oppression] and were not willing to take the abuse anymore.” The radical, anti-colonial protests resulting from WWII, as well as the Civil Rights and Women’s Rights movements worked to create a rhetoric around oppression that previously did not exist. This newfound vocabulary made it possible to verbalize the cruelties perpetrated against gay and lesbian people, propelling the Gay Liberation movement into the public sphere for the first time.

Because gay and lesbian communities in North America have historically been so vulnerable to judicial and societal violence, most of Dutton’s holdings represent queer culture from the 1960s onwards. A necessary quietude—the survival tactics of living under-the-radar, and even in denial of one's sexual or gender identity—means that Dutton’s most difficult task as an archivist has been to “work backwards” to uncover materials that describe the lives of queer people living in the 1950s and earlier.

One particularly unique case comes from an unlikely source. The Spanish Mapmakers of the 1730s, who travelled to document the coast of British Columbia, made several notes in monarchy-mandated journals about “cross-dressing” Indigenous peoples. More important than the discovery of men wearing “dresses” or women wearing “men’s clothing” was the discovery that these individuals were fully integrated and respected in society; whether they had same sex partners or held working positions typically associated with different sexes, people who identified as Two-Spirited were not outcast from their communities.

Dutton understands that certain groups have traditionally been written out of history. While the Spanish Mapmaker’s diaries have been studied extensively since the 1730s, for example, any notations therein about Two-Spiritedness were largely ignored. Even within the Gay Liberation movement itself, media representation in the 1970s generally showcased white, middle class activists. This is why Dutton has gone to extra lengths to make sure that the BCGLA offers as equal a representation as possible for all queer people.

Because Ron Dutton is ultimately committed to “bringing home” the individuals whose narratives the archive keeps alive, he regularly speaks at schools. He wants to connect with queer youth, who have grown up in a fundamentally different culture than he did. To see “gay politicians, musicians, and cultural icons” on television is something that Dutton did not experience in his childhood. He finds that young people have a great desire to know who came before them, and to hear what struggles their predecessors went through.

The elderly, on the other hand, have a more difficult time accepting Dutton’s claim that they have anything meaningful to contribute to the conversation—that they are, inherently, of historical and societal value. Again, due to the survival tactic of silence, queer seniors who lived through the 1940s and 50s can sometimes still be self-censoring. Dutton is patient, realizing that the stories of these individuals will be told and honored when they themselves are ready. With much sincerity and a depth of sensitivity, he tells us that he has a habit of combing through obituaries for mentions of “fond memories from the ‘special friend’” of the deceased. He will collect these notices and add them to the archive, knowing that he is bringing them home; the archivist wants “them to be where their heart was.”

I asked Dutton if he had ever imagined that the archive would become so expansive. He laughed and said, “If I had any idea, I would have been so intimidated I probably wouldn’t have even started.” The position has grown to be so substantial, and Dutton has been gifted so many collections of files and ephemera, that the task of stewardship has become a lifelong endeavour. “I have adjusted to match the needs that the job entails,” he tells us. A task this monumental requires a person with the fortitude to equal that of the archive’s holdings; by all accounts, Dutton is up to the challenge.

To visit the B.C. Gay and Lesbian Archives, email Ron Dutton to make an appointment: [email protected]

Alexandra Bischoff and Anna Tidlund would like to express our gratitude to Ron Dutton for offering us such a candid view into his life and work.

Text

Alexandra Bischoff

Images

Courtesy of Alexandra Bischoff, a BCGLA finding aid in-situ, 2016.

Courtesy of Ron Dutton, photo of Robert Pogue aka Adrian Alexandria de Vander Vogue, 1972.

Courtesy of Ron Dutton and Imtiaz Popat, photo of activist Imtiaz Popat and Salaamat during the Vancouver Pride Parade, 2010. Salaamat has since become Salaam-Vancouver when it joined the Salaam Canada: Queer Muslim Community coalition.

Courtesy of Ron Dutton and Pat Hogan, photo of the Menopausal Old Bitches (M.O.B.), Vancouver Pride Parade 2006.

#queer activism#vancouver lgbtq#queer archives#creative protest#art and archives#vancouver pride#vancouver drag#queer muslims#menopausal old bitches#vancouver#BC gay and lesbian archives

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Corporeal Returns: Feminism and Phenomenology in Vancouver Video and Performance 1968-1983

Text by Marina Roy

First Published in Canadian Art, Toronto, Summer 2001.

Scene: September 1975; Vancouver Small Claims Court; Diana Douglas in the witness box after being sworn in by the judge.

Judge: Your name please. Douglas: Diana Douglas. Judge: Miss or Mrs.? Douglas: Ms.

Judge: Pardon?

Douglas: Ms ... M...S...

Judge: What does that mean?

Douglas: It means that I feel that it is not relevant whether I am married or not. Judge: Um...You mean you are a nonentity...

From a distance of over twenty-five years, it may seem hard to believe that this scene between a judge and a citizen occurred during International Womenʼs Year, at the height of the womenʼs movement. For a representative of the law to say that women were either Miss or Mrs. and nothing in between, underscores the limitations put on womenʼs roles within society and the problem of symbolic domination that women had to contend with. A womanʼs social role had traditionally been defined in relation to that naturalized institution, the family. Foucault tells us that “juridical systems of power produce the subjects they subsequently come to represent”. The judgeʼs use of the word “nonentity” is significant in terms of the phenomenological issues that were being discussed within various cultural fields at the time — the idea that oneʼs body was an experiencing entity in-the-world. The juridical projection of “nonentity” onto Douglas uncovers deep-seated essentialist views. Cultural law projects readymade feminine attributes onto women, then somatizes them as a “metaphysical substance” inherent to “woman”.

When women attempt to shed these social fabrications, performing roles as subjects rather than objects they are disrupting the sexual division of material life, the very stuff on which the political economy of capitalism is based. This disrupts the repetitive flow of day to day collective social habits. According to Judith Butler our identity is constructed temporally by repeated and ritualized performative acts, a reenactment of a set of meanings already socially established and simply reproduced as natural: “If gender is instituted through acts which are internally discontinuous, then the appearance of substance is precisely that, a constructed identity, a performative accomplishment which the mundane social audience, including the actors themselves, come to believe and to perform in the mode of belief. If the ground of gender identity is the stylized repetition of acts through time… then the possibilities of gender transformation are to be found in the arbitrary relation between such acts, in the possibility of a different sort of repeating, in the breaking or subversive repetition of that style” (Theatre Journal, vol.40, p. 519).

In the 1970s many women artists in Vancouver were practicing this “different sort of repeating” using various performative strategies within video and performance art. These strategies were in many ways an extension of the spirit of the times. Theories of language and communication (e.g. Searleʼs performative speech acts) and phenomenology (Merleau Pontyʼs lived experience and his placing of the body at the centre of experience) were based on the idea of sentient agents acting within a socially- constructed environment. Simone de Beauvoir also used a phenomenological approach in her feminist classic The Second Sex . The days of Cartesian subjecthood, as psychically transcendent, divorced from the physical body, and epitomized in Western art by abstraction, essence, and genius, were beginning to recede into the modernist past. Lived experience was founded on the corporeal. The separation of all fields into essential categories was being deconstructed and reconfigured. The traditional division of labour on which heterosexual relations were enforced and naturalized, crumbled as women sought agency outside the confines of the domestic sphere, the family unit.

In Vancouver, from about 1968, the new media of performance and video art were developing at the same time as the feminist movement and the beginning of artist-run centres. Within these centres one had free access to equipment and studio space, and found oneself part of a supportive community of artists practicing divergent disciplines. For one of the first times in history, many women found an alternative space to that of the home where they could live and work as artists. Collaboration meant the cooperation of bodies performing within a communal space, but it also meant taking part in an international network, as with correspondence art and video distribution networks. Funding for these collaborative ventures was increasingly provided for by the Canada Council. Also in 1968, the CRTC was instituting community access cable programming, thus signalling for many artists, the possibility for a more inclusive distribution of information and cultural expression.

It may seem paradoxical that such a heterogeneous array of media and agents should have come together at the same time to form such unparalleled opportunity for artists in Vancouver. A body-centred art practice worked in tandem with new forms of technological reproduction (video), avant-garde artists often found support from the cultural establishment (the Canada Council, the Vancouver Art Gallery), and video artists sometimes had assistance in production and distribution from broadcast television (Cable Ten). Women artists were at the forefront of this new activity in the 70s. A particularly wide variety of communities, counter-cultural, and activist strategies were formed by, and made available to women . The 70s signaled a moment of historical rupture for society and culture. Not only were the categories of Miss and Mrs. torn asunder; so were those of traditional art practice, reception, and distribution. Although other cities in Canada could vaunt a similar cultural climate, Vancouverʼs social and cultural situation was unique.

The period covered here, from the late sixties to the end of the seventies has come to be known culturally as the “Canadian renaissance”. The success of Canadaʼs centennial celebrations, especially at Expo 67 in Montreal, gave the nation a cultural presence on the international stage, seen as excelling in the fields of technology and communications. The key national cultural institutions of the CBC, the Canada Council, the National Film Board, and Telefilm Canada were instrumental in forging a national identity in an attempt to unite a small population across a vast territory. Radical changes were brought about in the arts in large part due to the Canada Council (established in 1957), with its armʼs length distance from government intervention. Without access to such funding, work space and equipment would have remained inaccessible to artists wishing to experiment with new technologies and approaches to making art. The pressure to create marketable art works was alleviated by the presence of artist-run centres, opening the way for a more socially-engaged praxis. While most commercial galleries were still steeped in modernist paradigms, the artist-run centre began an investigation into interdisciplinary approaches to new and traditional media. The government encouraged the use of this new technology in the cultural realm, for it served to strengthen Canadaʼs image and reputation globally. The eventual institutionalization of artist-run centres and alternative community groups, set up through various funding programs, was also a way of keeping more activist, oppositional groups under wraps: “The lessons of the Roosevelt era in the U.S., which saw the absorption of the radical movements of the 1930s through meagre but widely accessible state funding, were not lost on the Trudeau government, itself a product of populism and the mass media” (_Vancouver Anthology_, p. 63).

Vancouver had always been isolated geographically, and it was only with increased air travel and broadcast communications that there was a turn toward a more national and global perspective. Vancouverʼs supposed lack of history, itʼs profoundly multicultural status stemming from a constant influx of immigrants, perhaps made people feel that there were fewer homespun traditions constricting their identity. People tended to come to Vancouver with an image in their minds of the last frontier, a land burgeoning with unlimited resources and opportunities, factories implementing the ideals of progress and innovation, not to mention its reputation as lotusland — a welfare and drug culture. One came for economic opportunity and a lifestyle. Because Vancouver was a peripheral city, not a centre in the modern sense of the word, it was very much at home with the idea of networking, incorporating innovative communications systems, as a way of keeping in touch with the world, in turn drawing the world to it. Its dispersed, elusive identity, and its new economy of “dynamic services” in the 70s, made it warrant the title of “postmodern city”.

The utopian impulse to blur the boundaries between art, life, and technology began in the early sixties when a new generation of artists was breaking away from the lyrical regionalism of landscape painting associated with Vancouver. In 1961, a giant leap into the international arena of art took place at the University of British Columbia, under the guidance of B. C. Binning and June Binkert. The Festival of the Contemporary Arts took place every February for the next 10 years (1961-71). These collaborative events included works by a host of prominent local, national and international artists and poets (mostly from New York and California: Cage, Cunningham, Halprin, Rauschenberg, etc.). The festivals were initially inspired by the “surge of postwar artistic energy first released by the abstract expressionists in New York” (Alvin Balkind), but in the end it was the anti-establishment practices of interdisciplinarity and experimental play that were de rigueur , in the areas of music/sound, poetry, dance, happenings, film, theatre, installation, etc. The festival acted as a catalyst for the emergence of a new kind of artistic praxis, of an international rather than regional or national character.

In 1966, a group of artists and architects, many of which had participated in the activities of UBCʼs art festivals, decided to create an artist-run centre where collaboration and new electronic media would signal the dawn of a new utopian consciousness. With some local financial support, and $40,000 from the Canada Council (the first artist-run centre ever to be funded), these artists bought film and electronic equipment and founded Intermedia in 1967. The space was essentially a democratic one, upholding an open door policy to anyone who wanted to experiment with multimedia. The first video portapak was introduced to Vancouver artists via Intermedia in 1968.

Without a doubt, the most important collaborative activities to come out of the late sixties were that between Intermedia and the Vancouver Art Gallery under the aegis of Anthony Emery and Doris Shadbolt. The VAGʼs Special Events programming and three consecutive years of Intermedia week-long festivals (1968-1970), were the principal venues for new explorations in performance art. It was one of the only spaces available where artists Gathie Falk, Evelyn Roth, and the Helen Goodwinʼs dance troupe could realize their performance works. Such visiting artists as Ann Halprin, Yvonne Rainer, Deborah Hay, and critic/curator Lucy Lippard were especially inspirational to these artists. The VAG and the Vancouver Public Library also played an important role in initiating and sponsoring womenʼs art events such as Women in the Arts that presented performances and discussions.

In 1968 Deborah Hay held workshops at the Douglas Gallery and Intermedia in what was then called “dance-oriented live performance”. Originally inspired by the Black Mountain College experiments and happenings from the 50s, Hayʼs workshops sought to incorporate body movements from everyday life into performance: “From my work with artists, I learned to appreciate the way non-dancers responded within the context of a performance. I never asked them to execute movements that they did not do in everyday life.” 1968 heralds the dawn of performance art as a discipline in its own right in Vancouver. Before this time, artists and dancers would experiment with sound, multimedia light shows and installations, more or less in an improvisational manner, without any solid idea except perhaps a McLuhanesque notion of global communication and counter-cultural communalism. Women had been taking part in these collaborative intermedia events, especially as dancers and poets, but they were often ignored and given second place within multimedia events. While collaborative performance was an alternative to and a critique of individualistic (male-dominated) modes of art production, this rarely meant that women were granted an equal place within that community. After Deborah Hay taught dance performance workshops in Vancouver a whole new direction was taken in performance-based works by women.

The use of repetition within these dance-related performances was directed toward creating a new type of audience participation. The process of performance was made transparent through the use of variations on repetition, as constitutive of the social rhythms of the body. The audience would relate to performers through their use of mundane movements and non-hierarchical relations between dancers. This type of performance would reflect the everyday lives of all members of the audience, implicating them in a non-hierarchical fashion. Bodies repeated the same actions so as to allow the audience to see these movements. The use of repetition also evokes what Judith Butler calls “identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts”. In phenomenological terms, the body is displayed not only as being in-the-world, or as a sensuous and experiencing entity, but in a state of perpetual becoming: “The body is understood to be an active process of embodying certain cultural and historical possibilities… the acts by which gender is constituted bear similarities to performative acts within theatrical contexts” (p. 521).

Works performed by such dancers as Helen Goodwin and TheCo used everyday movements such as people slowly moving along a wall, or “dance” movements where each member would execute one of a number of separate activities in a continuous repetition: one person rolling themselves in paper, one person walking with sponges attached to their feet, another performing actions with an umbrella, etc. From the very start, Helen Goodwin had been very active within the UBC Festival for the Contemporary Arts and had been a founding member of both the Sound Gallery and Intermedia. Her work was in close collaboration with musicians and multimedia artists within these communities. The Anna Wyman dancers presented a more professional dance performance situation, employing everyday, repetitive movements within their dances, set to electronic music by modern composers such as Stockhausen. They also performed at the VAG during Intermedia festival events.

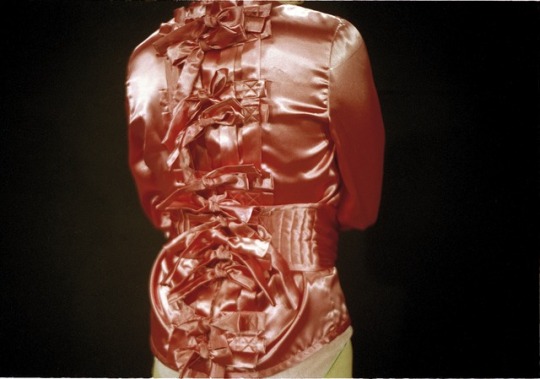

Evelyn Roth combined performance and video art in a thought-provoking way. Costume design is usually considered secondary to theatrical production or social life. Yet the sartorial displays social codes, setting up hierarchies between subjects. Through crocheting and donning videotape garments Roth came to embody a persona during the 70s. As a bag-lady-cum-fashion model, she somehow elevated the idea of being a mundane public media figure into the realm of art. She is best known for her performances in crocheting recycled video tape into garments, hats, car covers, gallery awnings. The action of covering bodies, cars, and buildings in used videotape could be construed as a comment on the technologization of bodies and spaces, our entrapment within the very medium of communication that we use to try to transcend our bodies. The use of crocheting within the context of art also placed value on womenʼs work.

One of the most acknowledged performance artists to have come out of this Intermedia/VAG collaboration was Gathie Falk. Her performances began within the context of Hayʼs workshops. Everyday, task-related activities and repeated objects played a central role in her artwork, signaling the repetitive nature of womenʼs domestic work and the fetishization of women into objects of desire.

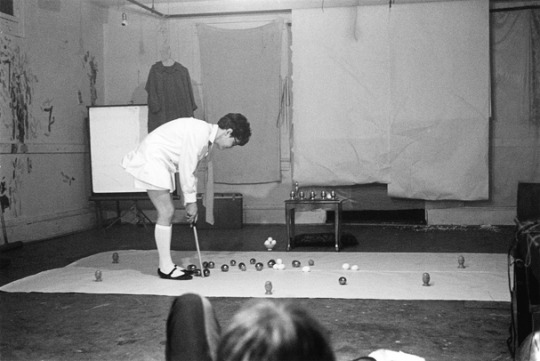

Falkʼs girl-child costumed persona (white blouse, pinafore, maryjane buttoned shoes) seems to reinforce the idea of masochistic entrapment that Falk within her work. Her use of eggs (with its references to fertility) is abject and disturbing in two of her performances: Eighty-eight Eggs (in which she is pelted with eggs by the audience) and Some are Egger than I (where she bats around ceramic eggs croquet-style until she hits a raw egg; by some absurd logic she then proceeds to eat a boiled egg; this action is repeated eight times). The impact of Eighty-eight Eggs as a performance relates to masochism: she is egged by the audience as if in reaction to a bad performance, and yet she performs nothing. This being egged “before the fact” becomes a statement unto itself, implying perhaps inadvertently that this is how women feel when they are discouraged from expressing themselves or put down publicly if they do attempt to play roles that are considered inappropriate to their nature. The slapstick nature of audience participation falls short of the mark, turning into pathetic spectacle.

Another example is Red Angel where a winged Falk sits atop a commode while five record players with ceramic parrots on them, do a musical round of “row, row, row your boat”. Falk herself repeats the same lines last. The idea of being a broken record, driven to repeat the same lines over and over like a parrot, reflects her role as woman trapped within the vicious cycle of repeated acts, as a woman passively displaying herself as a decorative ornament, repeating what she is taught to say. Once the musical round is finished, a woman wheels in a washing machine, removes Falkʼs gown, washes it, and then leaves the space. Falk then repeats the exact same opening sequence. The performance repeated a second time is however profoundly different. The repeated sequence speaks of entrapment. The angel follows the motion of a technologized controlled rhythm, just as womenʼs work is controlled by the technological rhythms of home appliances.

As a body-based art form, performance had its roots in early 20th century avant-garde art. In the 1920s (in Europe), and again in the 50s and 60s (in the U.S.), a type of ʻtheatricalityʼ formed itself in opposition to the modernist myth of the autonomous work of art, legitimized by the art institution, created by the male ʻgeniusʼ artist. The prototype was Picasso in Europe, Jackson Pollock in America. Amelia Jones in Body Art: Performing the Subject has pointed out that the fascination with Pollockʼs performative process of action painting, first seen in photographs from the late 40s and early 50s, was downplayed by theorists such as Greenberg. They emphasized product over process in the work. In reaction to modernist criticism, minimalist artists made work that Michael Fried characterized as degenerating away from art and moving toward theatre—what lay between the arts. Preoccupation with duration, whereby the beholder became implicated in the artwork, was considered anathema to formalist critics. In an ironic gesture pop art elevated mass media for the viewer. Subsequently, conceptual art elevated the philological notion of art as idea in the form of instruction sheets, card files, and even photographs of deadpan performative acts (or the result of these acts). These practices favoured the dematerialization of the object.

Video art and performance art by women could be seen in part as a culmination of, and a reaction against many of these strategies. (In many ways, one could see feminist strategies as one of the major vital forces behind postmodern turns in art.) The process-oriented, performative aspects of action painting, the inclusion of the beholder and of duration within the artwork, the dematerialization and ephemerality of the work, were elements that were retained from the art strategies of the 50s and 60s. But the preoccupation with formalism and information at the expense of figuration or the body was considered to be foreign to womenʼs experience. Having always been relegated to the status of immanence rather than transcendence in the Cartesian tradition of Western thought (transcendence/mind/male vs. immanence/body/female), women were relegated to the realm of the corporeal, weighed down by their biology. Thus the importance for many women of representing their bodies and life experiences within art works. One of the main reasons women turned to performance and video in the late 60s was that it was still uncharted territory. While men had made a history for themselves in the more traditional media of painting, sculpture, film, and photography, video and performance was so new that women felt they could truly make the medium their own, make it speak for them without the historical baggage of male precedence.

The chief social reaction to the end of the war in the 1950s, a time of unparalleled economic wealth arising from a war-fuelled economy, was a soaring marriage and birth rate. Family became a sacrosanct institution. In Canada, as in the U.S., television was to become the ideological channeller of such a vision: “Members of the Fowler Commission viewed television as a unifying source for the rejuvenation of family, serving as a headquarters, a gathering place, enhancing family encounters in the home and strengthening the moral fabric of the nation… what was striking about this focus on the family was not only the reification of the home as the source of moral order, but the way in which television was contextualized as a fixture not of community, nor of the individual, but of the family unit” (Dot Tuer, “Family: An Examination of Community Access Cable in Canada”, Fuse , Spring 1994, p. 26).

By the 60s a new strain of ideology, in the form of the movie star, the rock star, the media icon, and artist genius, touted individualism as the religion. Given the socializing influence of television, distortions of reality determined how people perceived themselves and one another. The coincidence of the sixties generation with the media culture boom meant that youth developed a narcissistic relationship with new archetypal role models. As the hegemonic structures of broadcast and press information began to belie their morality and truth-value, artists took Marshall McLuhan at his word and took on the role of “perception experts” and “educators of the future”. Videoʼs phenomenology, its format and its inherent “real time” aesthetic, connects it to television. For this reason, using video as a new form of global media, became a way of expressing disillusionment with televisionʼs biased, manipulative nature.

One of the great advantages of video was its reproducibility, exchangeability, “synced audio-visual portability, low-cost reusable tape, and instantaneous record and playback capabilities” (Paul Wong). The medium was very much in tune with the times, with the idea of a free-floating distribution system of ideas dashing across the globe, setting up a network of collaborative projects by artists made through the process of exchange (mail art), of special interest groups not bound by the strictures of space and time. Performance and video artists fought against the alienating effects of television in two ways: through ironic posturing and through social-activism.

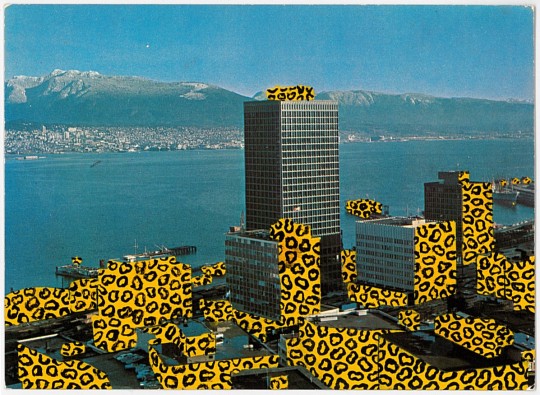

1973 was an extraordinary year for video art in Vancouver. There was the Matrix conference that gave rise to Video Inn/Satellite Video Exchange Society (through the donation of 120 tapes by artists who partook in the Matrix conference); the Pacific Vibrations Exhibition at the VAG showcased video and performance works; the Womenʼs Film and Video Festival gave rise to Reelfeelings, a womenʼs film and video collective. It was also the year that the Western Front came into being. That year a group of artists found themselves homeless thanks to the razing of old buildings to make way for new more expensive ones. Rents had also been hiked and they were looking for housing alternatives. Needing a home and studio space, and no doubt inspired by Intermedia and New Era Social Club, not to mention the Maplewood Mudflats community in Dollarton, these artists came up with the idea of pooling their money together and establishing a communal living space. Founding members Michael Morris, Vincent Trasov, Kate Craig, Eric Metcalf, Glen Lewis, Mo Van Nostrand, and Henry Greenhow set up the Western Front. Unlike previous artist-run centres, the Western Front was much more selective in terms of the facilitiesʼ conditions of use. Equipment and studio space was reserved for themselves, select friends, and artists-in-residence.

Fluxus type activities began when Image Bank was formed, a mail art network inspired by Ray Johnsonʼs New York Correspondance School of Art. In keeping with the latter activities, Western Front artists took up pseudonyms and personae that stuck with them for years: Dr Brute and Lady Brute, Mr. Peanut, Flakey Rose Hip, Marcel Idea, etc. These in turn became future roles within cabaret events. This use of “larger-than-life” media-style personas was at once playful and critical inspired as much by Dadaist strategies of the 1920s as by the glamour stereotypes of mass media. The use of pseudonyms was based on the fantastical idea of being able to change life into art or rather, art into lifestyle. It was also a comment on the facticity of the so-called norms of identity tailored to everyday life as produced under capitalist modes of production.

The construction of personas was also very much about liberating oneself from the strictures of nationhood and geography. Creating a new persona and being known as that persona had a somewhat tribal or totem-like ring to it. Demarcating oneself from the status quo became a political statement steeped in irony. It signaled being part of a different tribal community, one bound by relations other than kinship ties. For women it was a way of criticizing the structure of the normative family relations. Community and public agency were seen as breaking the bipolar categories of home/work, private/public, husband/wife, life/art. Trapping oneself within a persona was about breaking free from this socially-regulated somatized prison.

These extravagant high camp gestures were thus based on a will to form a community outside of the usual roles of daily life, they literally wanted to unmask the alienating effects of traditional roles on everyday life. By making their lives a public spectacle, they were also becoming fictional embodiments of cliched glamour images, parodying the ubiquitous Hollywood and TV star. Being a West Coast city, Vancouver quite naturally has a cultural dialogue going on with a place like LA. The Western Front participated in (and the Image Bank helped organize) the Decca Dance in Hollywood in 1974. It was a parody of the Academy Awards that attracted hundreds of performance artists.

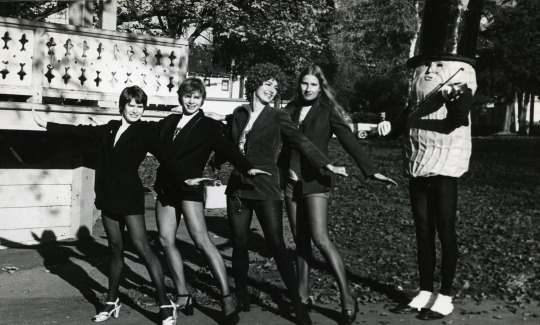

Kate Craig organized the Western Frontʼs video production studio in 1976. In 1977, she established and curated the Artist-in-Residence Video program. Her strong administrative role within the society, her leading role in video production, and her prominence as a performance and video artist in Vancouver, all contributed to the formation of a strong presence of local, national and international women artists at the Western Front. Some of the women who have been more directly involved with the Western Front over the years have been Jane Ellison, Daina Augaitus, Elizabeth Vander Zaag, Karen Henry, Annette Hurtig, Susan Milne, Babs Shapiro, Cornelia Wyngaarden, Elizabeth Chitty, Margaret Dragu, Mary Beth Knechtel, Judy Radul. Craigʼs performance of Back up in collaboration with Margaret Dragu, reflects a panoply of activities and narratives, gender stereotypes, and new roles enacted by women. Without being overtly political, they play out the lifestyles of school girls, pool-hall tough girls, scientists, upper- class debutantes, and domestics.

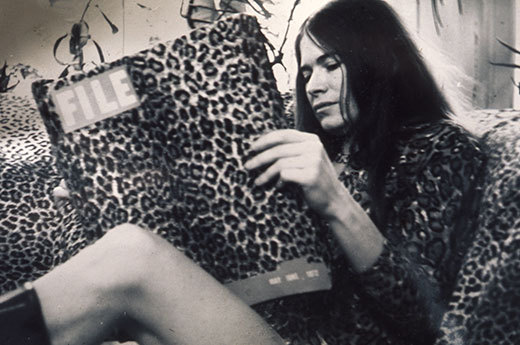

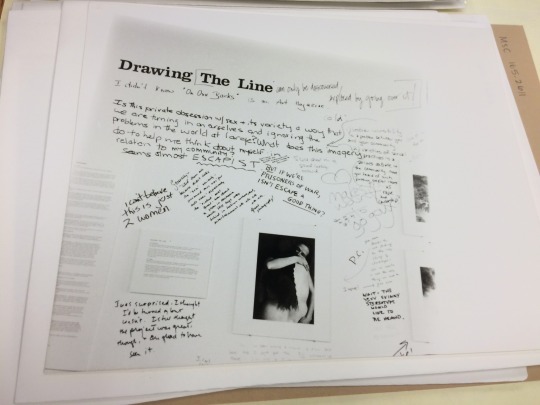

This mercurial role-playing reflects Craigʼs inclination towards adopting quite a variety of personae in her art-as-lifestyle. She was one of the Soni Twins, one of the ʻEttes, and at one point she identified herself with the colour pink (via an extensive pink wardrobe). Her most lasting alter-ego however was Lady Brute, a female stereotype based on leopard- spotted accoutrements. In her own words, Craig says that: “Lady Brute was...very much a part of Dr. Brute, a collaboration with Eric Metcalfe in terms of our marriage and our lifestyle together. Lady Brute was a mask, a point of focus, where you could step one pace behind and use it in a very specific way without necessarily becoming that person...One of the wonderful things about Lady Brute was that there was a stand-in at every corner. If I wore the leopard skin it was only to become a part of this incredible culture of women who adopted that costume”.

Craig based at least two videos on her persona Lady Brute. Through the Image Bank mail-art directory she acquired a huge collection of leopard skin paraphernalia and garments. The fashion statement associated with faux fur and mimetic animal patterning seems to signal female aggression and animal sex drive. As a sign-system it serves to mask the alienating effects of the colonization and exoticization of the female body, grounding it in a reversal of predator/prey fantasy. In the video Skins (1975), Craig documents herself modeling her Lady Brute wardrobe. She dresses and undresses in front of the camera, taking on different poses and stereotyped attitudes for each costume. The female stereotypes named in the video soundtrack describe the type of woman Craig becomes in each new outfit. Her multiple incarnations as Lady Brute underline the parodic nature of the video, as it traces out the many fantasy construction that dominate womenʼs lives.