Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Tales Along the Senescent Trail

Brass Monkeys Again . . .

It really was cold. No wonder you always see brass monkeys hugging each other. Momsie and I clung tightly to each other and teetered out to the white Colorado. A thin reddish-yellow line of color blanketed the dark mountaintops as early dawn slipped toward day. The smell of woodsmoke drifted along the dense frigid air. I fumbled with the keys. My hands shook more now, and I don’t mean from the chilly air. I popped the door, clambered into the driver’s seat, and cranked Snowy up. With a quick roll of the starter, the engine barked to life as June struggled in through the passenger side and plopped down. Thank God for wide running boards on trucks!

After an hour-long trip, we bumped into an empty parking lot just in front of the outpatient center intake at the hospital in Gainesville. After dealing with the sleepy desk clerk, we rode the elevator to the second floor with our peel-off name tags plastered to our chests and flimsy hospital masks covering our faces.

I slipped into one of those annoying hospital gowns, you know, the kind that fastens in the back with no easy way to tie them together so your butt cheeks hang out for everyone to gawk at and admire. I was lucky. My tiny rear stayed hidden in the wide folds of the hospital skirt. I dropped my medicine bag on the tray next to a hospital bed and lay down, my cold hands draped meekly across my churning stomach. Why do hospitals have to always be so morgue-like cold?

From there we were pushed to the fourth floor to meet Dr. M.

“Hello Sir,” he said with a smooth toothy smile as we lightly bumped elbows. June exited to the waiting room and was surprised to see a magnificent panoramic sunrise of glowing orange, red, and purple skies. The nurses grabbed the hospital bed by the side rails and pulled me into the operating room. Dr. M. sat down next to my bed, took my arm, and gently patted my wrist.

The preop procedure surprised me. One startling aspect concerned the shaving of the privates. When I asked, how come? Dr. M. stated matter-of-factly that if the arm procedure didn’t work, they would have to go in through the femoral artery in my leg next to my crotch. I made some stupid joke about discussing job descriptions at parties and then fell into an awkward silence. The nurse didn’t even crack a grin at my attempt at humor. She aggressively slopped the cold iodine all over my inner thigh.

Dr. M. moved in close. “We’re going to get started now.”

I watched him lower the slender tube and impale the pulsing radial artery at my already numbed right wrist. The tiny catheter slipped in with hardly a twitch from me. The pain medicine made me start feeling a little loopy. I glanced up for a moment to where the tubing filled with saline solution connected to the transducer device. I felt just the slightest twinge. The uncomfortable electric hospital bed seemed to slowly fall away from under me. I gripped at the rails.

Dr. M. glanced up and smiled for a second. His smirk seemed a little mischievous to me.

“You won’t feel a thing,” he winked.

Then everything winked out.

*********************************************************************

Dr. M. called the whole procedure Angioplasty, and the technique is quite commonly used for both adults and children. The cardiologist snakes a hollow threadlike tube with a tiny balloon at the end up the blood vessel towards the narrowed area of the heart artery so that the doctor can use a procedure called fluoroscopy to see what’s happening to the heart and circulatory system surrounding it. Upon locating the blockage, the cardiologist may inject liquid contrast or “dye” into the blood flow to highlight the arteries and help the doctor find the stoppage(s). Once found, a guidewire traverses the blockage, and a balloon catheter pushes into the obstruction and inflates which allows proper blood flow through the artery again. Next, the drug-coated wire stent expands and provides a permanent tunnel for blood flow into the heart.[1]

********************************************************************

Next thing I know, I’m slowly blinking my eyes open. Blurry images float by like stumbling frames in a slow-motion movie reel.

I thought, what just happened?

A young guy in a nurse’s uniform stepped into the room. His name was Daniel, he said. He checked the needles and tubes which protruded from both my wrist and antecubital fossa better known as the crouch of the elbow. I had to stay prone and immobile for hours.

Night came. Dr. M. wanted me to stay overnight. June had gone home for the time being. Everything was really quiet when I started having trouble breathing. It’s like trying to catch your breath on every third breath. I started to panic a little. Shortness of breath was not something new to me as I had the same problem with the pulmonary embolisms in my lungs. I would take two breaths and then things would settle down a bit until I started to doze off. Then I would jerk awake and catch my breath again. This went on for what seemed like hours. When Daniel came in to check on me, I complained about it. He said that it was probably caused by a side effect from the Brilinta blood thinner Dr. M. prescribed for me after the treatment. He said the brain is fooled by the drug into thinking it needs oxygen when it really doesn’t need any.

“It’s quite common, you know.” Daniel said matter-of-factly. “We see it often in heart patients here.”

I asked him what could be done about it.

“Well, it’s mostly psychological so we could try giving you some oxygen, even though you don’t really need some. It should trick your brain into thinking everything is okay now.”

I said let’s do it, and he slipped the feeder tube into my nose. Unfortunately, as it turned out, it was still a rather bad night.

The hospital’s so-called bed, lumpy and elevated as it was, kept me awake most of the time. Coupled with the short breaths, I got little sleep. Daniel remained as sympathetic and helpful as his duties would allow.

Next day, I got to see my heart beating in real-time on a special ultrasound machine. It looked amazing—almost like a mini-thunderstorm inside the heart. At every beat, lightning flashed in a kaleidoscope of colors in the turbulence of my seething blood. It seemed unreal. The ultrasound technician said that they wanted to make sure everything looked okay before releasing me so we watched the beautiful tempests together for a little while.

Incidentally, I know you might think that I don’t respect the VA Health system from all my talk about things that have happened to me while in their care. But make no mistake, I do respect them. They have always been there when I needed them and have demanded very little in return. The VA Health Care System represents a great organization for the vast majority of veterans who would otherwise be without any health care at all. Additionally, the twelve-week community service heart rehab program they completely paid for after my release from the hospital turned out to be a success as well. I lost twenty pounds over that period and regained a lot of my lost strength from forced inactivity.

Nevertheless, even though the operation was a resounding success, I was really glad to see Momsie that day. We went over to the Longstreet Café for some tasty fried chicken and fix’ns. I also noticed that the Café had put General Longstreet’s portrait back on the wall. He lived in Gainesville after the Civil War and was greatly respected there, even if he was a Confederate general. He was an unusual man. I chuckled a little. So much for political correctness.

As we made our way back to the car, my daughter’s gift of a yellow get-well-soon-balloon popped out in the blustery winter air as soon as I opened the rear door. I jumped but didn’t catch it . . . and there was no pain. For a moment, I watched in envy as the smiley face swirled round and round into the big cloudless blue sky . . . and I smiled too.

[1] Angioplasty and Stent Placement for the Heart.” John Hopkins Medicine. hopkinsmedicine.org. Health. 2021.https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/angioplasty-and-stent-placement-for-the-heart.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 10: Tales Along The Senescent Trail

It's been a great class. Hope to see all of you in the future. Please watch the video below for my narration of my essay. Thanks.

Good luck.

So, I was going to put up another video I created that contained my reflections on the class. Guess what? The editor says I can only upload one video. So, you can't read all the juicy things I had to say about our class. However, it was really sweet juicy stuff, mostly . . . so, I guess you'll just have to be satisfied with the one video I uploaded above.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 9: Tales Along the Senescent Trail Revisions

Reflections on Essay Writing Revisions

In the beginning, I thought to try to tell the story of my experiences with the Veterans Administration Health Care System as a straightforward, chronologically ordered piece of creative nonfiction. However, I realized it might be easier to tell the current story chronologically and peppered with anecdotal flashbacks to enhance a mixture of candid current events mixed with humorous/serious incidents.

I thought to alternate between the current situation and past events to illustrate my frustration and appreciation of this so-called veteran-friendly, giant governmental organization. However, the story turned out interesting, and after comments from peers concerning structure scene-linking problems, the revision of the story seems to be going quite well.

I have decided to drop the numerous graphic images, quotations, and cartoons, in favor of a more streamlined look with only one or two of the most critical images used to illustrate my points in the story. I will also make sure that my work follows the MLA format.

Of the few images I will use, gleaned from the internet, I will make sure I get all copyright permissions I need, if any, and give credit where credit is due to organizations and/or individuals involved.

I also plan to use the Word spell check and thesaurus where I see it needed. Another method I will use to ensure readability is to run my essay through Grammarly to check for spelling and grammatical errors. Sometimes Grammarly even recommends changes in sentence structure, and I will be looking at that also.

One thing pointed out by our class instructor involved the use of “yelling” boldface fonts. I will be eliminating those in favor of regular 12-point italicized font to emphasize a statement rather than boldfacing it.

One of my peer reviewers suggested that sometimes it is unclear what I am referring to in the story, so I may need to revise those parts the peer reviewer pointed out that possibly need revision. This peer reviewer also suggested that I might want to reconsider using Part numbers to introduce new scenes as it was clear that the scene had changed. They also suggested that I consider removing the indentations for each paragraph, but after reading the instructor’s comments, I believe I’ll leave the indents in place since this is an essay. They also suggested that sometimes the scene changes occur too abruptly, so I will be looking at that as well as time changes. A valid suggestion was made to more directly address the problems with the VA Health Care system rather than relying so much on humor. Another peer reviewer suggested that the beginning could be revised somewhat to reflect what the story is really about. They also suggested that the transitions between paragraphs could be better, and also, the flashbacks created too much “jumping around.” They also suggested it might be well to be more explanatory, as many of the readers might not be very familiar with the VA Health Care System. The reviewer also suggested that some of the images used were confusing, that they didn’t quite understand why they were put in the text at that specific point.

I very much appreciated the feedback from my peers, and I will be incorporating some of their suggestions into the final draft of the essay.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 8: Tales Along the Senescent Trail--Prepping for the Real Deal

I watched his tense reaction closely. He seemed preoccupied.

The dark brown skin of his broad forehead furrowed into a little triple-vee frown between thick eyebrows. His elbow remained anchored against the black rigid arm of his chair while a white narrow forearm pillowed a tightly closed fist against his jaw. He suddenly reminded me of that famous sculpture “The Thinker” by Auguste Rodin poising before The Gates of Hell.

Dr. M. slowly tapped a stuttering pencil against an open notebook.

Tap! Tap! Ratta-tap-tap!

The irregular beat banged forth annoyingly.

“You have to make a decision,” he said as the drumbeats grew louder and louder above the word-crowded pad in front of him. "We agreed to that after our last meeting."

A faint whiff of stale cigarette smoke hung in the air as I glanced at the hand gripping the offending pencil. Dark yellow tar-‘n-nicotine stains smeared the inner recesses of his index and middle fingers, contrasting dramatically with the pure white sleeve-ends of his jacket.

I was annoyed and also sympathetic, having once been a smoker myself. I smirked silently and rubbed my coarse tongue back-n-forth against the ribbed roof of my mouth to scrape the imagined bitter taste away. Old habits die hard even now.

Perhaps the Hippocratic Oath should really be the Hypocritic Oath, I mused.

I sighed. No matter.

“I have decided,” I said. “Let’s do it.”

“Okay. Just to be clear. We’re just going in there and take a look,” Dr. M. paused dramatically . . .

“. . . but, if we do find something, we’re going to fix it right then and there. Correct?”

I didn’t hesitate but crossed my fingers under the table anyway. “Right!”

We had already discussed the possibility of a stent insertion if he found a blocked artery. I didn’t really relish the idea of the invasive procedure, but I knew that my life might depend on it. The old ticker suddenly skipped a beat in my chest as I pondered what all this meant.

He glanced at his calendar.

“Let’s see. How about February 4?” he asked. “I need you here early in the morning—by 6 am.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 7: Tales Along the Senescent Trail--My Google Essay

While it might seem on the surface that I have a lot of issues with the VA. I can not in good conscience paint the organization, metaphorically speaking, as a bumbling, stumbling idiot, although it might at times seem that way.

My Google Earth Map links cover a gamut of things that have happened to me during and since my release from active duty and my time in the Reserves.

The VA Health Care has stood by me through thick and thin over the years, and I am truly grateful for it. Although the quality of care is not what you might get with a million-dollar bank account at hand, it was sufficient to get me to this point in my life.

The VA is a HUGE organization. I’m surprised it does as well as it does. I am not excusing it for the bad things that have happened, like the unnecessary deaths of a lot of vets mostly through neglect, but it has done far more good work than bad over the years.

I want to thank dryaddesigns for putting his blog up first. I don’t think I would have ever figured out how to make the Google Earth Map without his lead.

See this link for my Google Maps Essay.

https://earth.google.com/earth/d/1Qe2Vzy2-24G26hBAMc6Z5fkRjZ2EZegL?usp=sharing

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 6: Tales Along the Senescent Trail--An Unexpected Adventure.

Incredibly, it’s been four hours now!

I’ve been lying on this gurney for so long I think I’m going blind.

Wait! Here comes someone who’s actually making eye contact with me.

“Mr. Thornton. I’m Dr. Jones. I’m working the ER today.”

My throat is so parched, I can only croak an acknowledgment.

“Sorry for keeping you waiting so long, but we get homeless walk-ins all the time. We had to make sure you weren’t just another drug user looking for a fix.”

Hello. I’m wearing farmer Jones bibs with suspenders. Do I look homeless to you?

“We get too many folks trying to get in here every day looking for a quick fix when they run out of drugs, so we had to make sure you weren’t one of them. We try to help them but it's reached a point where we are being overrun."

I sat up. Suddenly I didn’t feel too good. It was getting hard to breathe again.

“Hey, Doc!. I’m having trouble breathing. Can you give me some oxygen or something,” I gasped as I laid back down. I had a pale complexion before I ever came down to the VA hospital. Now I was turning a purplish color.

The doctor made a quick gesture to an orderly standing close by and called for a wheelchair, an IV, and oxygen. They whisked me up to the fifth floor and into a hospital bed there. You know, the kind with the flip-down rails running horizontally along each side.

I began to feel much better after they put a nasal cannula in my nose. The nurse pulled a curtain between me and the guy next to my cubicle. I quickly fell into a deep sleep—the best I’ve had in a while.

I woke up the next day feeling much better. Soon a nurse entered the room pushing breakfast food carts with trays, but she didn’t stop by my bed. I wasn’t very hungry anyway.

The nurse pulled the curtain back, and I chatted for a while with the guy next to me. He was a cheery, talkative young man who very nonchalantly told me they were going to cut his foot off in a couple of days. He stepped on a nail, it seems, and it got infected. Turned gangrenous on him. So, now it had to go.

A little later in the morning, Dr. Smith came to see me. We chatted for a while about my symptoms. He said that he wanted to perform a catheter insertion through my right thigh so we could take a look at my heart. I said sure. Anything was better than going on like before. Not getting enough oxygen to your brain is like slowly drowning where you’re gasping for air but not quite suffocating.

When we said goodbye, I lay down thinking about the stress test I had taken the year before and felt a shiver go up my spine.

When I first started displaying symptoms of fatigue, my doctor at that time recommended that I go to the VA hospital in Atlanta and take a stress test. I had no idea of what I was getting into.

So, at the appointed time, I went to the hospital for the test.

Now, you’ve got to understand that parking at the VA hospital in Atlanta is an adventure all on its own. I tried it once and finally gave up after circling the parking deck twenty-eight times. After that, we utilized the Valet Service at the front door of the hospital. That was really great—if you could ever get to it. Sometimes the valet parking line snaked all the way around the hospital, and even out into the main road at times. It took a long time to get to the front door.

I finally made it and took their redemption ticket. I made my way back to the stress-test room where they determine how your heart works during physical activity. They stuck a bunch of cardiac memory loop monitors all over my chest and put me on the treadmill. I can tell you I wasn’t looking forward to the test because of my angina episodes. I did warn them, but they didn’t seem to be too concerned.

We started out real slow, and things were just fine—until they picked up the speed. I started to huff as the speed increased and warned them I wasn’t feeling too good. They poo-pooed that and cranked the speed up.

I was having trouble holding my own and warned them I was “fix’n to go.”

The male nurse hollered, “just give me another minute . . . just a minute more!”

“I’m fix’n to fall!” I gasped. Then I did. Right down on the still rapidly moving treadmill. I slumped to my knees and grabbed the support bars as my knees dragged out behind me.

A couple of male nurses grabbed me and picked me up and off the machine and set me down in a nearby chair.

“We’re so sorry! We thought you were okay,” the nurse stuttered apologetically.

Yeah. Sure. Like I didn’t warn you.

So now you can see why I was a little leery about having a catheter procedure. As it turned out, it wasn’t so bad. They took me down to a special room where they administered the stent through my inner right thigh and up to my heart with a camera.

It was terribly interesting. I was able to see my own heart beating and all the little black web-like arteries and veins that roped to and from my heart.

The doctor--and I forget his name now--seemed surprised at not finding something wrong there.

“Hmmm. Your heart is only twenty percent blocked, and that’s really good for your age,” he murmured, more to himself than to me. He paused . . .

“I think we’re going to send you to the Nuclear Lab to let them take a Nuclear Lung Scan because I don’t see anything much wrong with your heart. For your age, it’s in pretty good shape.”

The next day, I went in for the scan.

He brought the results back and gave me a strange look.

“Well, it looks like you’ve got three clots in your right lung and two clots in the left one.” he paused, “You should be dead. It only takes one to kill you.”

Thanks for the cheery prognosis. Needless to say, they sent me back to the fifth floor and put me on a blood thinner right away.

Later that evening, the doctor came by.

“We want to keep you here a few more days to make sure everything is going okay (with the thinners).

“Okay,” I said. “Hey, Doc. Do you think I can get something to eat? I haven’t had anything in two days.”

He just stared at me for a moment in total exasperation.

Somehow, they didn’t have my name on the patient list for food so the food cart kept bypassing me when it came to the fifth floor.

I lost fifteen pounds during my stay at the VA. Not by choice, I can assure you. I looked forward to leaving.

This was a real scary brush with death. It wasn't my first, and it wouldn’t be my last. Over the next couple of days, I thought about many of the things I had done—both good and bad—over the course of my life.

It all seemed much clearer now. I knew what I had to do.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 5: Tales Along the Senescent Trail-- The Waiting Room

Seriously!

I’ve been anchored to this gurney in a hallway next to the emergency room for two whole hours and nobody’s even come by to check on me!

I must say, it really doesn’t surprise me. After all, this is the VA.

Don’t be late!!

Hurry up and wait! Hurry up and wait!

As I lay there, I got to thinking about the last lab line. What a dog and pony show that was!

Just take a number . . . and wait. The waiting room was small and filled to capacity by every type of person you can imagine, all ready to blow . . . and some did. I distinctly recall waiting in line in the hallway with my number clutched tightly in my hand as a whole troop of VA riot police came charging by and into the lab room. After some scuffling and loud protests, they dragged some poor vet out the door and disappeared down a nearby stairwell.

If you were lucky enough to get a seat inside the waiting room, you had to keep your eyes glued to the digital number counter on the wall. If they called your number, and you didn’t respond within the allotted time, too bad! Go pick another number and get in line again.

The last time they siphoned off some of my blood in the second-floor hospital lab, I jumped when they called my number, (because I dozed off and wasn’t paying attention to the digital time warden).

I ran to the counter very apologetically, but the nurse wasn’t very sympathetic.

“ID please!” she hissed.

I fumbled in my wallet, and of course, it wouldn’t come out. It suddenly seemed glued to the leather slot in which it resided. I glanced at the nurse and smiled contritely. It finally popped loose and immediately slipped through my fingers onto the floor . . . somewhere.

“Wait, wait,” I begged.

I dropped down and scanned the stained rug. There seemed to be some type of unctuous odor emanating from the torn oriental weave. I pinched my nose and swept my fingers across the nasty nap, snagging my pinky on a loose wire just as I fingered my card. It bled nicely, and I should have immediately requested a tube and saved myself the trouble of a needle later.

“Ouch!” I protested.

From above I heard a deep sigh.

“Sir. Are you okay?” someone asked.

I arched up and banged my head against the nasty underside of the counter. I glanced up at the huge wads of gum reserved there and cringed.

I stood up.

“Yes. Yes. I’m okay.” I said half-heartedly.

She gave me a long look and sighed.

“Take this and give me a sample.”

She handed me what looked like a baby’s sippy cup. I looked at her questioningly. She pointed to the room at my left that said “Bathroom.”

I smiled sheepishly.

Her frown deepened.

I hustled over and through the door. I had to go real bad. Of course, wouldn’t you know it, the door would not lock! It reminds me of the Depot bathrooms where none of the sliding locks would ever slide into the lock, which of course, leaves you vulnerable to anyone who jerks the door open as you squirm on the stool hollering, “It’s occupied!”

I finally gave up and tried to unzip. Now, all men know that when the time comes, that little brass lever—the zipper-pull—is embedded in the zipper folds of the trousers, and no matter how hard you try, it just won’t come loose.

I started to get anxious. They were waiting for me.

After a furious jerk, I finally got the little brass b*****d loose and tried to go, as the urge was upon me. Of course, nothing happened. The dam wouldn’t break! I looked around the ceiling in desperation to see if any cameras were posted on me. Nothing.

Finally, it came, not in a great youthful gush, but a slow agonizing dribble that took FOREVER.

Suddenly, it was over. I snapped the lid tight, put it on the turnstile embedded in the wall, and gave it a spin. Smiling, I stepped back through the unlocked door.

A male nurse grabbed me by the arm, chuckling, and said, “Come with me.”

I followed him to what looked like a student desk with a swing arm.

“Sit here,” he said, politely. “Don’t mind the ladies. They really do like the vets.”

After giving what seemed like a pint or two of rich red blood in numerous vacutainers, he let me go, and I made my way back through the packed throng towards the exit.

The nurse turned toward me smiling and waved.

“Have a nice day!” she sang.

I did a small double-take and moved on.

Was that a one-fingered wave of her hand??

Nope!

Just another VA day.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 4—Tales Along the Senescent Trail: Part 4

At the speed we were going, I just knew we were going to crash. I gripped the handlebars like a baby clutches a bottle—very tightly and pushed hard against the pedals as we weaved in and out of traffic, the IV drip swinging wildly above my head. June and the grandbabies came scooting behind as we came to an abrupt halt at the emergency room, and I was unceremoniously shoved through the swinging doors into the waiting area. Two burly orderlies flipped me onto a gurney, and there I remained for four hours in a supine position with little attention and a great deal of apprehension about what might come next. Such are the unexpected and endearing adventures when one is dealing with the VA.*

The whole episode started from such a simple thing.

While scribbling a few notes in my workshop, I dropped a pencil, bent over to pick it up, and kept right on going. Next thing I know, I’m sitting in the recliner in the living room with a bunch of folks hovering over me like a noisy crowd of fake relatives gathered around a deathbed.

June pleaded with me to go to the hospital, and I finally agreed.

We were babysitting two of our grandkids at the time, so we grabbed them up, tossed them into their car seats in our white Silverado, and rushed downtown to the VA hospital.

June dropped me off at the emergency room door, and I stumbled into the entrance while she raced to find a parking space for the truck.

The male nurse at the check-in desk looked up at me and frowned. I stood there in faded blue, raggedy, farmer-Jones bib-overalls that stood out like a sore thumb among the herd of white uniforms.

“Can I help you?” he growled as he leaned back and folded a set of burly arms across a really big chest.

I straightened up and replied.

“I’m having chest pains”

He stood up and said in a more serious tone.

“Is this an emergency?”

The question caught me off-guard. I’d never experienced an “emergency” like this before, so I hesitated a few seconds before answering, trying to untangle my thoughts.

Well, this must have been instant confirmation to him that I didn’t need immediate care.

“What’s your team color?” he snarled.

“Purple. I’m purple,” I replied a little confused and intimidated.

“You need to go to your own station to see your doctor” he barked with a finality that was hard to argue with.

I knew where the Purple Station was because that was my age group, so I headed through the swinging doors, up the crowded halls, and stopped in front of the nurse’s station with a big purple stop-hand glowing above it. You know, like the kind you see at crosswalks.

The nurse kept scribbling furiously across a pad she held in front of her, ignoring me. I soon began to fidget and finally mumbled a weak “ahem!” to get her attention.

She looked up with tired unfocused eyes.

“Yes. Can I help you?”

“I’m having chest pains and the guys in the emergency room told me to come up here and see you all.”

Her eyes snapped wide, and her jaw almost hit the desktop. She swooped around the counter and said, “come with me” as she grabbed me by the elbow and rushed me over to the doctor’s office.

“Dr. Singh!” she hooted as she pushed me ahead of her into his cubicle. He looked up and frowned. “This man says he’s having chest pains and emergency steered him to us!

“Damn! Those idiots! What are they thinking?” he screamed.

“Get him a wheelchair and wheel him back down to emergency!” he screeched as he snatched the phone from the receiver.

The nurse scooted back around the corner and produced a wheelchair outfitted with pedals and flying a used IV drip at the back.

She shoved me into the chair and went zooming down the hallway.

We intercepted June and the grandkids scrambling along the way.

And that’s where we are now . . . waiting for the next step.

*Veterans Administration Health Care System.

Source: Actual Personal Experience.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 3: Tales Along the Senescent Trail: Part 3

"At my age, flowers scare me." —George Burns

Damn! I couldn’t stop shaking. It was cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey!* I tried hugging myself, but it didn’t help much. The icy wind blew past with a shriek and a deathly caress colder than my evil stepmother’s last kiss. We slammed the front door shut and teetered forward into the frigid air,

We rolled into a frozen February for the hour-long trip to the hospital in Gainesville. Dr. M insisted that we get there early, but, I mean, getting up a four-thirty in the morning is kinda—no, it’s real early, even for a former Marine. I hadn’t had to get up this early since my days in boot camp on the rifle range at Parris Island.

Even so, I stretched a yawn and stepped carefully towards the white Colorado, taking note of the icy brick patio.

“You’d better take my arm,” I told her. June wasn’t as nimble as she used to be. We called it the Bashir shuffle, after watching an episode on Star Trek Deep Space Nine when the station’s doctor, Julian Bashir, was hexed by an alien and began to age rapidly. At the end of the episode, he was talking in a high-pitched voice and taking little tee-tiny shuffling steps. We got such a kick out of it, we named his gait the “Bashir shuffle.”

It’s not so funny now.

In any case, it was too early and too cold for a couple of old coffin-dodgers like us to be wandering around. I mean, a slip could mean a busted hip, a cracked skull, or worse. It was bad enough that I had to go so Dr. M could “take a look in there” to see what was going on.

I made a fist with my right hand and unconsciously started lightly tapping on my upper chest. I stopped for a moment to catch my balance. My heart started racing. I could feel the slowly tightening chest constriction take hold.

“Hold up a minute, Momsie.” I steadied myself against her, and she gave me a quick worried look.

It was that old familiar painful squeeze--angina.

Years ago, in the beginning, there was no pain, only an immeasurable slowing down and a faint feeling of all-encompassing tiredness. Even the smallest incline taxed my physical abilities. I hardly even noticed it at first, but then there were the episodes.

In one instance, after cutting three-fourths of the front yard, I started to feel weak. I could hardly even push the self-propelled mower or keep it in a straight line. I stopped and leaned over the handles to catch my breath. I felt faint and clutched tightly at the bar.

“Are you okay?” Momsie hooted from the porch where she had been sitting, watching.

I didn’t answer. I couldn’t answer. Suddenly I couldn’t breathe good.

She stood up and hollered for Nghia, one of my students, who was working on wooden dummies in the back. Nghia shot out the front door at the sound of urgency in her voice. He was a strapping young Vietnamese boy and always seemed to know what people were thinking by the sound in their voices.

She pointed at me and shouted, “Help him!!”

Nghia came scrambling down the hill. It looked real easy for a sixteen-year-old, but he was lanky and real strong.

He grabbed me by the shoulders with one arm and by my belt with the other as he helped me back up the driveway, through the front door, and into the recliner on the other side of the living room.

They hovered over me like a pair of helicopter parents until I felt the hotness and the pain recede out of sight into the center of my chest. The thumping was not as wild and scary as before.

“We’re taking you to the emergency room right now!” Momsie cried.

“No. Not yet. It’ll pass.”

It would take a more serious episode to break my stubbornness.

============================================

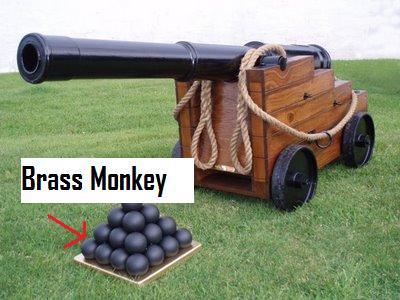

* In the British Navy, they would stack cannonballs on a brass plate with holes (aka a monkey). If it were cold enough, the holes in the plate would contract to the point that the bottom balls could no longer rest in the holes and rolled loose, and thus the term, “it's frozen the balls off.” This became common marine terminology and morphed into sailor slang as “it’s cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey” when referencing uncommonly icy weather.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 2: Tales Along the Senescent Trail: Part 2

As I dodged the automatic doors that tried to ambush me, the lady-receptionist at the lobby desk hooted loudly.

“Sir, you gotta wear a mask to come in here!”

Comprehension comes a little more slowly now. I raised my right hand questioningly.

She hooked a finger into her cool black mask, covered in glaring white Nike symbols, so she could be heard more clearly. “Your mask! Sir! You must wear a mask to enter here!” she shouted with an exasperated, ugly tone and shot me an even nastier frown.

Crap! What’s the big deal! We’re not lepers. We don’t have any obvious open sores and don’t wheeze too loudly. We had already gotten our Covid shots a month ago. Damn! I fumbled clumsily in my pocket and fished out a covering my grandson had given me. With some difficulty, I managed to get the flimsy rubber band connectors around my ears and shifted the mask over my nose. SpongeBob’s ridiculous face ogled from my mouth, although I must admit my grandchildren and I find the program extremely amusing at times.

My wife June hugged my left elbow like a blind woman grips a walking stick as we teetered through the snapping jaws of the entrance. Together we shuffled towards the elevator and headed to the second floor of The Heart Center.

I glanced down at some poor guy in a wheelchair with his tongue lolling out and a head that hung at an impossible angle above his shoulder. He kept staring at me until, embarrassed, I jerked my eyes away and focused on the elevator panel buttons. I felt a twinge of regret for gawking too long.

As we stepped through the elevator doors, June hugged my elbow like a jumper clutches a parachute. Real tight.

After checking into the doctor’s office, we managed to find a couple of chairs next to each other. Someone had ripped the caution tape off the chair I dropped into.

After a few minutes, the nurse came out and called my name. As luck would have it, I followed her into the same waiting cubicle I had occupied last time. The ugly orange ceiling tile was missing, replaced by a brand-spanking-new white one. I could already see faint orange moisture forming at one corner of the tile.

Another bulge-hugger.

The diseased heart charts were missing, replaced by diet charts hawking new slim-jim menus with in-your-face, before and after caricatures of people like us and the beautiful people.

The nurse took my weight and blood pressure then asked the usual questions. Was I depressed? Did I think about committing suicide in the last week? Did I have trouble urinating? Was I incontinent? How was I sleeping?

Then she left with a cheery “The doctor will be with you in a moment.”

An hour later, there was a soft knock at the door, and Dr. M. stepped quickly through and right up next to me.

“Well?” he asked. “Have you decided on what we talked about last time?”

I shifted slightly, and the toilet-paper tissue under me crinkled loudly. I had been anchored so long in one spot I could feel nasty bedsores forming all over my rear end.

“Yeah. I think we should go ahead and take a look,” I whispered as I reluctantly rolled from one hip to the other, the bedsores screaming for mercy.

“Good!” he exclaimed gleefully. “Now let’s see . . . .”

He grabbed my right arm and twisted it so the forearm faced upward and then lovingly touched each ropey greenish-blue vein at the wrist. Finally, he came to an abrupt halt over a long, mostly straight one.

“Ah! . . . this one will do nicely.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 1: Tales Along the Senescent Trail: Part 1

"If you live to be one hundred, you've got it made. Very few people die past that age." George Burns

I really hate being an old codger. People treat you differently. You know, with no real respect for the old ways or the old days.

I sat stiff-backed and squirmed a little on the thinly padded barber-chair-like recliner decked-out from head-to-toe with a long wide roll of absorbent paper that looked like someone had swaddled the chair with a scarf of cheap tissue. I chuckled sarcastically. Yeah. Head to Toe. You know, like someone had pulled too much oversized toilet paper from the roller across the steeply inclined and totally uncomfortable imaging chair. It made an unpleasant crinkling sound as I fidgeted there. I felt a stiff twinge at the base of my neck and absentmindedly rubbed it as I twisted and glanced over at the diseased heart charts on the wall. Above them, an ugly orange mushroom-like stain hugged a bulging ceiling tile in the corner of the waiting room. Tilting my head slightly, I sniffed lightly into the air. The cubical smelled damaged and old.

Suddenly there was a light knocking at the door and a short young Indian guy in brilliant white, with a spiffy-looking binaural black-n-steel stethoscope hanging askew from his neck, stepped firmly through the door. He introduced himself as Dr. M. as he sidled up uncomfortably close to me. For a moment, I wondered if he spoke in that thick Indian brogue you hear so often from the telemarketers and the computer service guys, and for a split second, I wondered how come you never hear any female Indian operators on the other end of the line. The thoughts vanished as quickly as they came.

“Hi. I’m Dr. M. Are you Clark?” he asked in perfect English with a slightly flavored mid-Western accent. I was pleasantly surprised. I had assumed, like so many do, that he would automatically start tripping over the ugly American digraphic “th” phoneme that some Asians and others seem to have such a problem with. You know, the voiceless dental fricative that always seems to bite the tongue and says “alien” without saying it. It’s the constantly annoying “dis” “dat” and “dee udder” that screams “other.” Suddenly I felt a little guilty about my baseless assumption.

He was dark-skinned and way too thin with deep, dark-brown eyes but with a surprising, pleasant voice. I relaxed a little.

“I’ve had a chance to look at your charts, and we have to make a decision.”

I stared incredulously for a moment at his smiling face.

No. I’m the one who’s going to have to bite the bullet, I thought.

“You have to let me know whether you want to continue on with your medicine or we take a look to see what’s going on in there.”

I squirmed some more.

Take a look?

I glanced down at my right arm with its long ropey blue veins. I knew all too well what that meant.

9 notes

·

View notes