A blog by social scientist and proud polynerd Peter Licari living at the intersection of data, science, society, and pop-culture.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I caught a funny bit of survey wording from YouGov. In one of their recent surveys, they asked Americans whether or not they believe in the idea of "soulmates." Far more do (56%) than don't (25%).

(For what it's worth, I don't personally believe in a preordained, universe-selected "perfect" match. I believe we can "find" soulmates in that we can grow and work to become them for our partners--and they can do so for us).

Regardless, it's usually good survey practice to use these responses to filter out people that are inappropriate for follow-ups on the subject. For example, in the survey I fielded with YouGov for my dissertation, I asked people if they played video games: yes or no. If they said "no", I wasn't gonna follow-up with "great! Now how often do you play video games with others in the same room?" They'd rightfully be like

So I had to chuckle when the very next question asked in the survey was "whether or not [the respondents] met their soulmate"--regardless of how they answered the first question.

Notice how this then implies that at least 63% of Americans implicitly believe that soulmates exist (yes, currently with + yes, currently apart + no, but expect to be together)?! Like, nearly 10 points higher than their previous question?

It's a leading question to be sure, but the stakes are low enough that all I can do is laugh about it.

0 notes

Text

I wish I had the source for this. If y’all know who it is, let me know!

0 notes

Text

I'm reading The Existentialist's Survival Guide by Gordon Marino, and I came across this quote, attributed to Dr. Ben Yacobi.

The concept of “authenticity” is a human construct, and as such it has no reality independent of minds.

This snidbit hit me like a lightning bolt. Not because of its direct message but because of its implications for other concepts we study in the social sciences. We who study society (through quantitative means and otherwise) often put on a positivist guise and try to "objectively" measure or report on something. But the things that many of us find to be the most interesting ("justice", "democracy", "ideology", "wellness") are purely artificial constructs. How can we claim to measure and observe something "objectively" when our only experience with it resides purely within our minds?

Our brains, according to neuroscience research over the last few decades, is not wired to isolate concepts from the emotions they're entangled with. If an object of study solely exists in our "collective imagination" (which is a funny term because our inclination of what the collective experiences is unavoidably imagined--unless we've somehow managed to actually, literally get in each other's headspace), then there's no way to be objective about it . We can be no more "objective" than we can about our opinions of Unicorns. By engaging in the cognitive construction of what a Unicorn should look like, we've invested in arbitrary standards. When we try to judge something by how closely it resembles our conception of a Unicorn, the only thing we're really basing it off of is a fundamentally subjective experience: the little model of a horned horse galloping around in our heads.

You can't be objective about something inherently subjective. That's as oxymoronic as diet soda. (Or, to use my former-Marine dad's favorite "military intelligence.")

To be more concrete:

There is no way to be "objective" in studies of war.

There's no way to be "objective" in studies of fairness.

There's no way to be "objective" in studies of belief structures.

While this is an important point for any social scientist, I think it's especially important to those of us trafficking in data science. We often take these exact same concepts and raise them even higher on the ladder of abstraction: We turn them into numbers and vectors that we can run regressions on, or try to "reduce" to a more manageable number of dimensions. And this isn't me saying that what we're doing isn't useful or that it's irredeemably flawed. It is and isn't, respectively. Just that we have to be conscious of what we're doing and be aware of how we're ultimately imputing our own values into the results we arrive at. Otherwise, we risk conflating a concept with greater social purchase and impact with our conception of it, all the while thinking that we're being "objective" about the whole thing.

I'm by far not the first social scientist to argue this point. Shoot, this isn't even the first time I've argued this point. But there's something so viscerally clarifying about the point when phrased in Yacobi's words that I had to share.

0 notes

Text

I had a lot of fun puzzling over this question. I love cooking and I saw the show that this book spun-off on Netflix. To me, these elements don't just make food tasty-- they're also integral to the whole pursuit of cooking.

Like, we use these tastes and processes to do creative new things to food. They're what experts wield to bring the most out of something, they're things that invite creative new dishes--but they're also already at the core of cooking as is. Baked in, as it were.

So I wanted to come up with 4 things that were like that for statistics and data science--at least as I understand them. The 4 I came up with were: Visualization, Simulation Methods, Gradient Descent, & Wholistic (often qualitative) subject matter expertise.

Visualization isn't just to make data pretty for end users--although that's often icing on the cake. They also allow US to understand what we're seeing in the data. They're both means and ends of new understanding.

Gradient descent underlies so much of the tools we use. Using an MLE method? It probably uses gradient descent to estimate the likelihood function. And odds are you're using an MLE method but don't realize it.

Simulation methods similarly underly so much of what we do. Everything from Bayesian methods to bootstrapping and a lot more. And more stuff is coming out all the time. (And I know my knowledge is pretty superficial here).

Last but not least, deep (often qualitative) subject knowledge. We often don't realize the assumptions about the world we lean on when we interpret results, but they're there. And they can't all be appreciated by quantitative inference alone.

One of my most formative quant experiences was a class on quantitative issues in studying race and ethnicity. I realized how much we take for granted the ideas we proxy with numbers. How solid they seem. Yet how contingent they really are. Like cooking over flame, there is life there, vibrant and fluid. It is humbling to work with and needs to be respected. And you can really only do that if you appreciate the broader context.

0 notes

Text

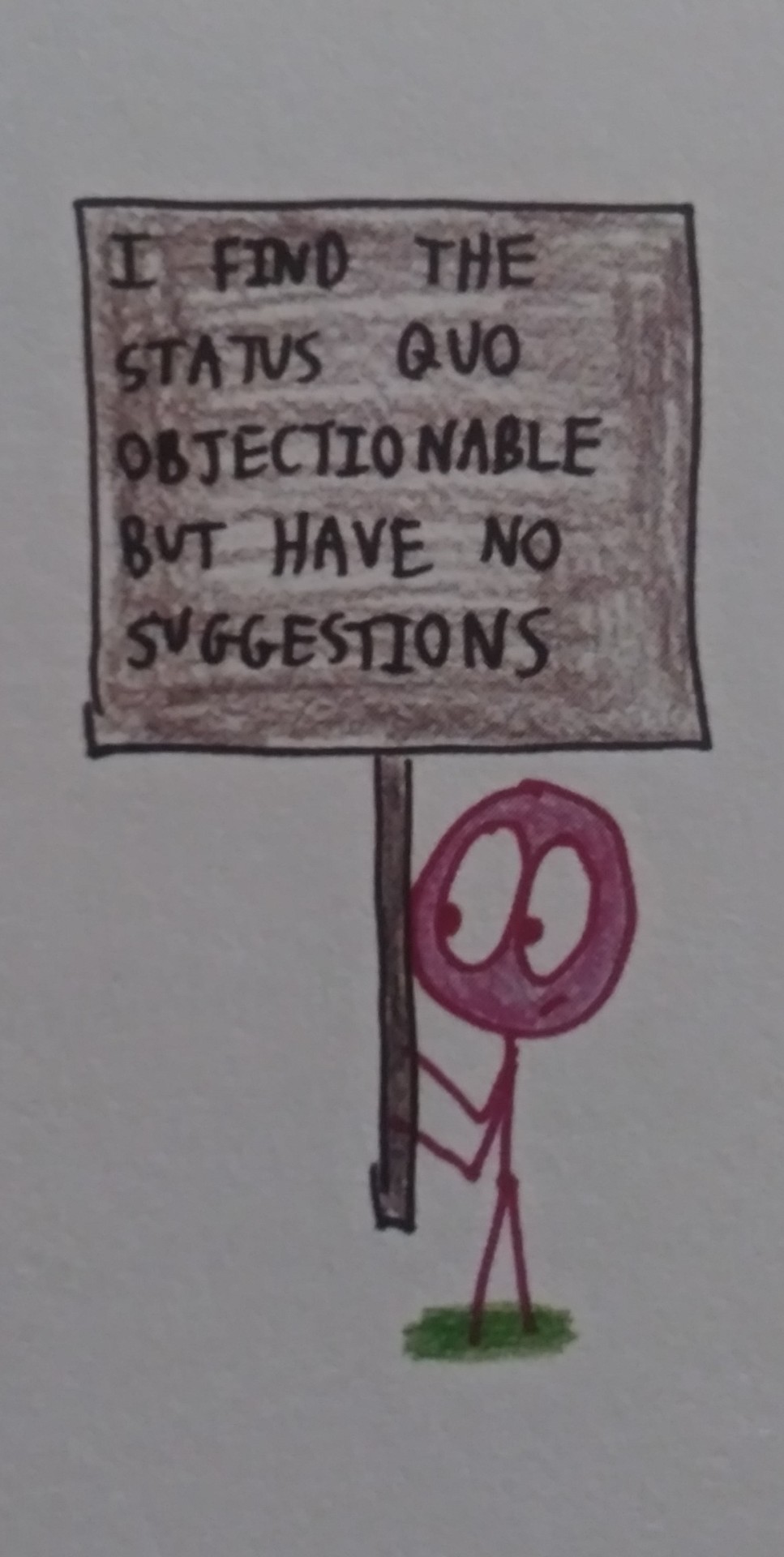

I just finished reading "Math with Bad Drawings" (I'll post a review tomorrow) and I saw this picture and I want it put directly into my veins.

0 notes

Text

Here's a (quasi)random thought I was having.

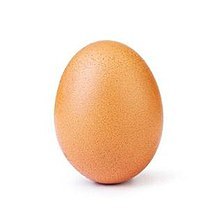

"An egg, relying only on inference, will never predict the moment that it shatters."

I'm currently reading Antifragile by Nassim Taleb, and have been enjoying a good deal of the book. One critique that he levies at scientists (especially social scientists) is that we base most of our predictions off of inference--the idea of what happened before will allow us to predict what happens in the future. It's undoubtedly useful (he and I would undoubtedly disagree about just how useful, but that's fine) but it's imperfect. The problem is that ultra-rare events with nonlinear impacts (so-called "Black Swans") aren't possible to predict using inferential methods since they are so rare that we can't estimate the probability distribution for outcomes--nor easily model the expected gain/loss in utility due to the event's non-linear impact. I was just reading the section discussing how tea cups deal with millions of micro-impacts every day thanks to fluctuations in air pressure but these don't add up to the harms of a single event exerting all of that force, like hurling it at a concrete wall. (Taleb used dropping it. I opted for something more evocative). I realized that the teacup would be so accustomed to the micro-shocks that, if it were conscious (and mathematically inclined), it would probably try to predict how turbulent the next few days would be using its accumulated experience. I.e., inference. And it would be totally ignorant of the possibility that someone could be having a bad day and want to chuck it at the wall.

Even more tragic, though, would be an egg undergoing the same experience. Because while there's a possibility that the tea cup will remain unmolested and unshattered (at least for a long time; in the long run we are all dead and tea cups all crumble), the purpose of an egg is to eventually be cracked and eaten. Its great tragedy is that inferential knowledge will never be able to inform it, warn it, of the deeper truth of its condition. That it is destined for impermanence. Deliciousness too--but mainly impermanence.

It leaves me wondering what systems of ours are similarly limited. I suppose that's the main thrust of the whole point of the book, but it makes me wonder all the same.

I'm not sure if I'll ever have an answer (or a satisfactory way of coming to one), but, hey, at least I got a pithy aphorism out of it!

0 notes

Link

I’ve finally done it! I’ve made a imgur folder of most of my data visualizations!!! Or at least most of those I can find. They’re curated so that the more recent/the ones I’m most proud of are closer to the front. The further back you go, the worse they are. So, you know, go to the end at your own risk. There are a few that I have to add to it still once I track decent-resolution versions of them down. But getting these 40 or so up is a pretty fair proportion of the side-projects/vizes I’ve done while I’ve been working on my PhD.

0 notes

Text

Old Ship Logs to Help Current Atmospheric Science

This is just a phenomenally interesting thing that I had to forward and share. I’ll let the original authors explain; I couldn’t do it better. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, millions of weather observations were carefully made in the logbooks of ships sailing through largely uncharted waters. Written in pen and ink, the logs recorded barometric pressure, air temperature, ice conditions and other variables. Today, volunteers from a project called Old Weather are transcribing these observations, which are fed into a huge dataset at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This "weather time machine," as NOAA puts it, can estimate what the weather was for every day back to 1836, improving our understanding of extreme weather events and the impacts of climate change.

I’m just learning about geographic interpolation (Kriging and the like), so this is just so cool on I can’t even explain how many levels. Source

0 notes

Video

youtube

I made a video on why #TeamTrees is going to succeed at getting 20,000,000 trees planted--and why charitable initiatives have a hard time reaching this amount of success so quickly.

0 notes

Text

Do shark attacks cause changes in voting rates? Apparently not at the local level. Via 9Gag

0 notes

Text

This is, by far, my favorite survey-based news article. And it’s not even close.

0 notes

Text

When someone asks me how I manage my work-life balance.

1 note

·

View note

Link

For those who are working in R and are struggling with recoding some variable in their dataset based off of the values of other variables (or even *gasp* the combination of multiple variables), I wrote this short, accessible piece and published it on RPubs. (I would’ve put it either here or on Medium but, apparently, neither gel particularly well with RMarkdown. Oh well. Would’ve been nice, but it ain’t the end of the world.)

0 notes

Text

Here’s something I found to be kind of funny. Gottfried Leibniz is undoubtedly one of history’s greatest all-around geniuses. Aside from his notable advancements in philosophy, logic, and engineering, the dude invented calculus independent of Newton. (Although it’s not at all clear if Newton did it independent of Leibniz...). One small measure of how laudable his intellectual contributions are is the fact that his name is recognized in Word, Google, and LibreOffice’s English dictionaries--which isn’t exactly the most common thing with German names. However, the thing that tickles me is that its only his last name that’s recognized.

It’s like “you’re famous enough to be recognized. But just your last name. You’re not quite on the level of ‘Sigmund’ yet.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Video games have become increasingly popular over the last few years. In fact, a recent survey suggests that approximately 2/3rds of American adults partake in the pursuit...Many of the medium’s most ardent critics argue that games offer only vacuous experiences. Lying beyond the pixels, polygons, and interactive scenes is just empty entertainment. Or, even worse, they argue that games are only a vehicle for mindless violence and other moral corruptions. But if you ask the designers behind many games, you'll learn that they often go out of their way to include elements in their games so that they have a deeper moral, social, and political appeal.” Over the summer, I got to play around (pun intended) the Strong Museum of Play’s archive of video game materials and periodicals. I learned a lot about how, when, and why developers include social, moral, and political content in games. After I wrapped up, they asked me to write a blog post about what I learned--and that post is now live! Check it out!

0 notes

Text

Couldn’t help but join in on the fun happening on Twitter.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: The Moral Animal: Why We Are the Way We Are: The New Science of Evolutionary Psychology. By Robert Wright. (1994).

Robert Wright’s The Moral Animal is a look through the field of evolutionary psychology--at least as it stood at the book's writing in 1994. It's a promising work with a lot of insight. However, it can best be analogized to the peacock: If it survives, it does so despite the massive disadvantage of some obvious maladaptions. In the case of the peacock, the adaption is its oversized tail (or "train" as it's often referred to). In the case of The Moral Animal, it's Wright’s own unexamined moral and ideological biases presented as fact that lowered its potential.

The big sell of the book is actually a rather interesting premise: Take the most famous proponent of the theory of evolution (Charles “the Chuck” Darwin) and use his life to demonstrate the principles of evolutionary psychology. Want to illustrate the theory that men are less biologically inclined towards lifelong monogamy thanks to our disproportionately small part in the baby-making process? Highlight the fact that Darwin literally sketched out a cost/benefit analysis of getting married in his notebook. Want to argue that young siblings should be both predisposed towards rivalry and cooperation thanks to kin selection? Give some (admittedly adorable) examples of Darwin’s many, many children. Because of this, the book was part popular-science exploration of a then-burgeoning topic and accessible biography on one of the most important scientific minds to ever emerge from the primordial ooze. When done well, this was the book at its best. It was discursive, informative, and enjoyable. It kept me engaged over much of the book’s nearly 400-pages.

(Lest someone use the opening example as evidence that I have no idea what the hell I’m talking about later in the review, let it be known that I know that the mystery of the peacock’s train was solved with the insights of sexual selection--that peahens select males with large trains because possessing one shows that the males have got to be pretty dang "fit" to survive with such a glaringly obvious disadvantage. Writing thematically consistent introductions is hard; I claim some artistic liberties here).

There are two core ways that this plays out throughout the book. The first is the odd insistence that every possible point that Wright could conceive of making in this vast subject was exemplified by good ol’ Chuck. And there were times that this was very clearly a stretch. The way he pursued his eventual wife, Emma, is described through a very genetic lens instead of primarily cultural terms (part of a supposed genetic predisposition towards the “Madonna-Whore” dichotomy for those of us with that infernal y chromosome). His differential patterns of grief for the loss of two of his children (he reportedly mourned the death of his ten year old daughter far longer, and far more intensely, then that of his infant son) are couched as being primarily due to their proximity to prime fertility age. His intense anxiety about publishing what would be his scientific legacy (you know, apart from being the 19th century’s foremost barnacle expert)? It’s the genes! It’s genes, genes, genes all the way down.

I’d like to say that the book was always like this. Or, apparently, my desire to want to say this, my inability to do so, and the considerable amount of sarcasm required to pen these last two sentences are because of my genes. At least that’s the culprit if we were to take Wright literally. At times, he is positively (and ironically) evangelical about the power of our genetics in dictating our behavior. And it is to the rest of the work’s detriment.

I’m not some biological denialist. I believe whole-heartedly in evolutionary theory. And, of course, the potential for any and all physical actions have to ultimately originate in the code that facilitates every biological process we undertake. But, first off, since natural selection works probabilistically, what do you think the odds are that, of the billions of humans to walk the Earth, the theory’s first popular progenitor is an acceptable exemplar of all of these processes? It’s laughably small. Literally smaller than the first common ancestor of all life on this planet compared to the sun. I don’t think that this means that Wright had to abandon the mission of using Darwin as an illustration--again, that’s part of what made this book so interesting--but it would be far better served if, instead, Wright said something to the effect of “we can see an imperfect analogy to these processes in Darwin’s life.” A small change but, as Wright knows, small changes can have a large impact.

I suspect that Wright’s self-admitted zealousy on the subject was partially spurred on by the fact that this book was written before epigenetics (the process through which different parts of the genome are activated/deactivated in response to environmental changes, changing the genes’ expression) was more rigorously demonstrated. I recall him adamantly insisting, once or twice, that genes “can’t be changed” once we’ve been conceived. At the time, that was the belief commensurate with the best available evidence. Although epigenetics do not disprove this, the truth is that our genes are far more flexible than originally thought. If genetic fixedness is what you’re arguing, it’s pretty tough to say anything other than “everything Darwin did ever is totally explainable through evolutionary psychology.” Even if it's not true. So I’ve decided to chalk this up to scientific progress and its inevitable, unenviable ability to reveal certain pronouncements as utterly wrong. It’ll undoubtedly happen to me; it happens to any practicing scientist.

The second theme, though, is less able to be chalked up to the inexorable march of progress. That is the distinct, but related, assertion interwoven throughout the text that literally everything can be explained by evolutionary psychology. Moral codes? Evolutionary psychology. Selective memory of our own moral failings? Evolutionary psychology. Western social structures and the necessity of political and economic inequality? Survey says: Evolutionary psychology.

These assertions are often manifest through what I call “cover your ass” language. We all know it; we all, regrettably, deploy it. It comes when the authors use absolute terms for the vast preponderance of the work and then say “now, do I really think that this explains everything? Of course not! But…” and then proceeds to make the exact same points, just with a couple of words interjected to signal intellectual humility. A few careful words do not erase the other 98% and the frames they collectively construct. Wright is arguing that evolutionary psychology alone can explain just about every social phenomenon, from the simple to profound. But the fact of the matter is that evolutionary psychology would be hard-pressed to understand why people on vacation with their families would bother to leave tips at restaurants despite the fact that they do, more often than not. (Seriously. Reciprocal altruism’s out since you’ll never see that server again. Odds are they weren’t related, so kin selection’s out too. Peacocking wealth contrasts with women’s supposed preference for mates who don’t needlessly divert resources away from her children. Tipping is a tough nut to crack for rational-choice-esque theoried like evolutionary psych). If it can’t explain something so banal as this, I have strong doubts of the deterministic account Wright explicates here. He will, almost begrudgingly, admit that social and environmental forces play a part in genetic expression. But he does not seem prepared to admit that it plays as big of a role as even the available evidence at the time did.

The more I read it, the more I felt that this book was symbolic of a lot of evolutionary science at the time: It contains real, interesting insight on genetic processes and their role (however expansive or limited) in complex interpersonal phenomena. These shouldn’t be undersold or ignored; I learned a great deal reading this book. The problem is that these insights come paired with uninterrogated moralizing, steeped in contemporaneous social events, passed off as timeless, objective Truth. The most obvious example (because of how often Wright returns to it) comes in the aforementioned asymmetry in male parental investment. Or, rather, the seemingly inevitable end-result: Divorce. This was often curiously paired with hand-wavey discussions of the Madonna-Whore dichotomy. Apparently, men who manage to have sex with women earlier in the relationship feel less inclined to see her as a viable marriage partner. Should a quickly-pairing couple (referring to the speed in which they decide to do the act and not, hopefully, the duration of the act itself) wind-up married, men are more likely to ditch the women--and ditch them for similar "kinds" of women. This discussion would often lead to Wright lamenting how women are engaging in sex earlier and earlier in romantic relationships. Things were better decades before this promiscuity was socially acceptable. Like back in Victorian England when Charles wed his beloved Emma. And the evidentiary linchpin, at times explicitly mentioned while only obliquely inferred at others, is the sky-high divorce rates that, Wright argues, came as a consequence of social structures being poorly designed considering our inherent genetic predispositions.

Of course, we now know that the high divorce rates of the 90s were a temporary thing. First-marriages are lasting far longer than they did (on average) in the 80’s, 90’s, and early 00’s but divorces are just as easy (if not easier) than ever before. If it was entirely because of early sex and our baser nature, the pattern should continue. The fact that it doesn’t is both evidence that evolutionary psychology is more limited than Wright suggests and that the urgency imbued in his analysis was shaped by his own moral sensibilities rather than those seen in society as a whole, inculcated by natural selection.

This wasn’t all of the social critique Wright was inclined to wade in. All fields and theories have their critics. Good authors often anticipate common objections and address them in the text. He saw his most likely critics as less scientifically driven as ideologically so. Lofty prose to the contrary, he was on the attack far more than on the defense; Darwin found himself a new bull dog. His target: Those dastardly post-modernists. He often panned “post-modernism” for their critiques of evolutionary psychology, often claiming (without much evidence) that it stemmed from the post-modernists’ universal and fundamental ignorance about biology. Honestly, the way Wright so derisively talked about them, I was surprised that he didn’t bust out a couple of verbose “yo mamma” jokes.

What makes his vituperative swipes so ironic 25 years later is that the post-structuralists were right. Many evolutionary scientists were predisposed towards advancing biologically deterministic theories of human behavior. Any practicing geneticist worth their salt today would tell you that human behavior is so dependent on genes' interactions with the social and physical environment that even things we take for granted as “hard-wired” (such as one’s sexual preference) has been persuasively shown to not be the consequence of singular genes--or even wholly the consequence of complex genetic interactions. This is a far, far cry from Wright’s portrayal in the book; I honestly think he would be aghast at this suggestion, as if it surrenders precious ground to heretical forces in the battle for all of science’s soul. And the post-modernists are consequently vindicated in questioning what kind of power is made manifest, and towards whom is it ultimately directed, when these assertions are given the pop-science stamp of total veracity. (Actually, despite it being basically their entire deal, I can’t recall a moment when Wright discussed power when issuing his disses of post-modernism. Instead, he discussed them in the same kind of shifting, ephemeral manner that paints them as boogeymen with accusations that were often equally grounded in reality. I think he would find his own intellectual horizons broadened if he allotted the same serious attention to their intellectual contributions as he demands for his subject).

To shoehorn in a personal complaint that I had, the book was heavy in evolutionary theory but very, very sparse in social-psychological insight. Spare a chapter where Wright tried to rehabilitate Freud’s reputation (as successful attempt as one’s going to have considering how uphill that battle is), most of the psychology was relegated to sexual pairing preferences and over-general suggestions on morality and social bonding. The former was interesting and insightful; the rest woefully underdeveloped. I may be spoiled by books like Behave and How Emotions Are Made (part of these phenomenal works both touched on how evolution may bring around specific cognitive processes), but I think Wright could have comfortably fit interesting, more specific insights if he shed the weird moralism and extensive post-modernist vendetta.

I hate closing reviews with negatives, no matter how well deserved. Presumably that’s in my genes as well. So I’d actually like to conclude by saying that I well and truly learned a lot from this book. Some of it was less novel so much as it was a refresher (I have read a number of prominent books on evolutionary theory, including the oft-referenced Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins), but some insights were well and truly new to me and illuminating. The one that stands out the most at the moment is the game theoretic accounts claiming that monogamy ultimately serves men (while institutional polygyny would be better for women) and the argument that people are more rude in spaces with fewer permanent interpersonal ties. I also thought the point that adherence to cultural values are an expedient for environmentally contingent reproductive success was well argued. I don’t buy these arguments entirely, but I think they and other points are worth mulling over to extract the useful bits. But in order to get to these bits, you have to be attentive and willing to parse through a lot of things that, in the rat-race of ideas, deserve to be thoroughly out-competed.

5 notes

·

View notes