Text

The Mistmantle Chronicles, Book 5: Urchin and the Rage Tide

We’re going through the mists, one last time…

Today I’m reviewing the fifth and final book in the Mistmantle Chronicles.

Yeah, yeah, at this point people know the drill. There’s a lovely island inhabited with moles, otters, hedgehogs, and squirrels. Spoilers ahead. This book (written by M. I. McAllister, illustrated by Omar Rayyan, published in 2010) features Mistmantle getting hit with an awful storm called the Rage Tide. There’s also a charismatic troublemaker named Mossberry.

The first thing I have to say is something embarrassing.

This entire time, I’ve been thinking that the animals were human-sized. It was the way they talked about food. I thought, surely they’re treating acorns the way we would. They pick up sea urchins like they’re hand-sized. A fish for us is part of a meal, but for small animals one fish would be a feast for several creatures.

But, no. I’m the world’s biggest goof. There is a castle built in the roots of a tree. There’s simply no way they’re not to scale with real world animals.

But they do age like humans. This book (finally) gives us an exact number on the time that passes! Eight years. Our hero Urchin is full grown, with a page of his own.

The beginning is a pure delight, as it should be. If your fantasy book about squirrels doesn’t have a joyful winter solstice party at the beginning, what are you even doing? No, really. It’s so essential to show why this world is worth protecting and treasuring.

From there… that’s where the pacing gets funny. These books will not-infrequently have confusing timelines, where island-wide events happen in just a few days or a few hours.

There’s a warning about the storm during the solstice party. Meanwhile, Mossberry the squirrel is undermining animals’ belief in the monarchy and Brother Juniper. Chapter 3 has Urchin discovering that, and asking Mossberry’s followers to explain what’s going on. Chapter 4 has the beginning of the Rage Tide and the confrontation with Mossberry. And by chapter 5, it’s over.

After that, I was like… wait, what is this book about?

There’s a pair of children who are missing for a few chapters. I was never really invested. Urchin’s page leaves the island to look for Sepia, who got washed away. And ultimately it turns out there is another Rage Tide coming toward Mistmantle. But all in all, I think the confrontation with Mossberry was rushed.

Honestly, I dislike the addition of Mossberry. Book 3 already had irrational fear and mistrust being the enemy (and Linty, who mistakenly believed she had to hide Princess Catkin). After so many books where I was positively surprised by the treatment of disability… Mossberry is kind of just “evil because he’s crazy”.

He’s delusional and it’s not explained in any detail like it was for Linty. He spends most of the book in a cell yelling obscenities. There was one bit of sympathy that I liked: Padra the otter captain says that Mossberry can’t get away from himself. Anyone else can just go away, but Mossberry’s stuck with himself. But overall, it’s not ideal.

Two further notes about disability: the otter scribe Tay is described as using a wheelchair. We get no further description. I want to see how an otter wheelchair works!

Also, at the end of the last book, the squirrel Scatter got injured. She started as a maid for Lady Aspen, and even years after Aspen was revealed as a murderous traitor Scatter was loyal and carefully maintained her grave. Scatter was injured during the Raven War and couldn’t walk anymore. But unless I missed it, Scatter isn’t mentioned at all in this final book. It’s just interesting that she’s been around since book 1 but didn’t appear at all in this one. Especially since we know animal wheelchairs apparently exist!

Some notes about species equality:

Overall, this series handles it the best out of most series I’ve read. I love the balance between making species matter (otters tend to like the water, squirrels leap through trees) and subverting the generalizations (not all moles hate the water, and Hope the hedgehog is just as good at digging as the best moles). Mistmantle has an otter scribe in the beginning, but a squirrel trains under her and takes over. We see some squirrel priests, but in this book an otter is training to be the next one and it’s not unusual.

The second chapter has a discussion about captains. They want at least one captain for each of the species, but they’re also concerned that would mean not choosing the best animals for the job. So basically they’re talking about affirmative action. It’s just interesting.

In spite of being the fifth book, the book does a good job of introducing things and explaining them (which is awesome in a children’s book). McAllister really knows her stuff.

I could just be getting fonder of the books. But I really think Rayyan has been improving, book-by-book. His art’s really sensational.

To get back to Sepia, the squirrel washed away early on: she and Urchin are kinda-together in this book. In the last review, I mentioned how funny I thought it was when Queen Cedar basically shrugged and guessed Urchin might be interested in Sepia. I buy the relationship in this book— they’re two likeable characters with a lot of positive traits. Eight years is plenty of time for feelings to develop.

But it’s also interesting to me since it’s another off-screen romance. We get the eight year timeskip, now they’re in love, and even during this book they mainly just think about each other because they’re separated. These are highly platonic books, with a lot of focus on the strong non-romantic relationships.

Before Sepia can get back to the island, though, there’s a sacrifice. One of the big details of the book which I haven’t mentioned yet is that King Crispin has to trade his life for Sepia’s.

It did get me. Knowing this book series was ending, and seeing this character I’ve known for five books, made me sad.

But if I’m honest, that emotional punch is one of the big things keeping this book afloat for me. This book would be notably worse, for me, if it didn’t have that emotional aspect. And I wish the death had happened in a better book.

The books say that Crispin was actually injured ever since the Raven War in the last book. It’s weak writing. He was technically on the verge of death buying time for eight years, except no one really noticed, so…? It’s too convenient.

These are generally great ensemble-cast fantasy books, though. We see the young people growing into the next generation of adults safeguarding the island, with proteges of their own. I love that.

I also want to talk about faith. There’s a perspective in these books that I hadn’t quite seen before.

I think this series has a uniquely positive view of religion, while also not just being pro-Christianity. Children’s books will sometimes have Christian elements that, y’know, bring up a lot of weird questions. What does it mean if Redwall characters are talking about Satan?! Or maybe they have basically-Christianity, but with different names.

But in this world, faith truly is a positive force. The books aren’t unquestioningly saying that we should believe. It’s not “the Heart is like God and that’s why it’s good and we should believe in it”. We legitimately see the power of the Heart. Plenty of times in every book, people pray because it’s all they can do.

It makes a lot of sense, because McAllister is married to a minister. The author bio in all the books is something like “M. I. McAllister wrote the Mistmantle Chronicles, she has children, she lives in England, and she’s married to a minister.” So clearly, faith is important to her. But it’s also fascinating that someone like that didn’t just make mouse-Christianity. The books have their own faith which is very different in some ways.

Getting back to this book, in particular: one of the ideas for how to get Sepia back through the mists (since she left via water, she can’t return that way) is to bring her the Heartstone. In book two, that’s how Urchin and Juniper miraculously came back via water. They unknowingly had the Heartstone on their ship.

But, this book explains that the Heartstone isn’t just a magic relic. It’s not an exact science and besides, it would be wrong to treat the Heartstone as a tool to get through the mists.

I would never come up with that perspective. I’m not religious, so to me it really would just be a magic item for gaming the system. The books really show-don’t-tell why faith matters. It’s awesome.

On a lighter note— McAllister also seems to enjoy scenes where one character is like “I’ve failed you, my King. Take back this sword, I don’t deserve it, I’ve done such a bad job here that I have to resign”. And then the King is like “no, you’re so good at your job I won’t let you!”.

And you know what? She’s darn right! It’s so cool! Great trope!

My personal rating for this book: 4

Overall rating: 3.5

Also, I haven’t done this before, but I want to rank the series as a whole. The Mistmantle Chronicles has truly been an unexpected joy for me. These past few months have had plenty of days when I really needed stories about loyal animals who love each other. And most importantly, stories written at an easy reading level. But they also start to bring in serious themes, and they generally treat them in a positive way. I have never read a better series in this genre. I highly, highly, highly recommend them.

My personal rating for this series: 4.5

Overall: 4.5

1 note

·

View note

Text

Urchin and the Raven War

I’m running out of things to say about returning to Mistmantle…

You know the drill, by now. This post is reviewing The Mistmantle Chronicles, Book Four: Urchin and the Raven War. It was published in 2008, written by M. I. McAllister and illustrated by Omar Rayyan.

You also know the deal about spoilers. There will be spoilers, as well as discussion of violence and death.

This book jumps forward in time a significant amount (although it doesn’t specify how much). Urchin is fully grown, and Princess Catkin (who was a baby last book) is up and around. She is talking, making decisions, and fed up with boring island life. When swans from Swan Isle come for help, the animals of Mistmantle go to their rescue. Doing that, though, draws the anger of a flock of ravens and Mistmantle is put under siege.

I’ll confess I was pretty anxious about this book. Last one was especially good, worthy of being an ending to the whole series. Luckily, book four delivered. I love that every book has very distinct tension. There’s usually a mix of threats from outside and inside the community.

It’s hard to say if the books are getting better, or if I’m just growing fonder of the series. I’m far from objective at this point. But that’s also a major testament to McAllister’s skill. She makes a world, and characters, that really draw readers in. I think Rayyan’s illustrations continue to improve, too. This is an archetype of the genre. This is what animal fantasy for children should be.

What could be better than a generational story with an ensemble cast? It’s very special to see characters mature and grow in responsibilities. The books were published at a rate of about one per year (which is remarkable) and I’m curious how people who actually grew up with this series felt about seeing characters go from children to being adults. The characters certainly grow up faster than the readers.

I really think that, finally, we got a Mistmantle book without a boring early bit. The other consistent problem, of too many characters, is also slightly improved. I think it helps to have characters who are swans and ravens.

This book has swans shown in a more sympathetic light, after they were kind of empty-headed in the first book and they didn’t even talk in the second. The ravens are pretty flatly dehumanized, though. It’s a common trope with nonhuman protagonists to have another species be monstrous. “Maybe rats and mice are okay, but owls and snakes are even worse!”

One character, Corr, is a young otter who’s searching for adventure. I find his journey interesting because he lives on his own for a while, after leaving home. It makes me wonder— what would society be like, if we could easily go off into nature and live without other people? If a human wants to try being self-sufficient, they’d need a lot of distance from other people, plus clothing, shelter, tools, and training to boot. But couldn’t Corr just hunt fish to feed himself?

Later, the otter Fingal kisses a squirrel on the cheeks because he promised he’d kiss whoever killed the raven prince. That’s the closest the books have gotten to addressing inter-species relationships.

Speaking of… At one point, a healer is urging Urchin to stay alive.

��Stay, Urchin,” she said. “Stay with me. Stay for Mistmantle. Stay for Crispin, for Juniper, for Needle, for all of us. Think of—” Is he in love with anyone? Take a guess. Stay for Sepia. Stay for your friends.”

That cracked me up. And, it made me realize how light on romance the books are. Almost all of it happens offscreen. Usually, we have a couple and then timeskip to them being parents. The most interesting relationships are platonic. I like that.

One thing I admire about this series is the treatment of violence. In the first book, a mole assassinates someone and then is killed himself. This book brings back his brother, seeking vengeance. That made me realize, violence is essentially never the answer in these books. It just begets more violence.

Ultimately, Mistmantle defeats most of the ravens with sticky nets. Plus, leadership struggles make the ravens fight each other.

At the end, even though the Mistmantle animals cut down the surviving ravens, they’re so badly injured that they die within minutes. That detail was so unbelievably convenient that I had to laugh.

Now for some worldbuilding. This book finally made Threadings merit the capital T, in my opinion. We meet a hedgehog who occasionally, unintentionally, includes the future when she’s making the tapestries that tell Mistmantle’s history. It’s pretty cool to imagine someone accidentally including the future in a historical document. Preemptive history.

There’s another kind of prophecy with the Silver Prince. He’s a kind of messiah for the ravens. They used to rule Swan Isle, but after they were defeated they promised never to return unless they had a Silver Prince to lead them. The swans agreed because silver ravens are rare, and only female.

I was wondering if I’d be able to claim him as a trans icon, but it seems like he’s just a grey raven who they got overly excited about. (You can still headcanon him as trans tho.)

Aah, these books make me happy.

I would love to hear any opinions about this series, especially if you read it when you were young!

My personal rating: 4.5 My overall rating: 4

#Moles#hedgehogs#swords#squirrels#children's books#me:4#oa:4#mistmantle#ravens#swans#otters#2008#faith

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Heir of Mistmantle

yeah that’s right they have hair now

This book review, I’m looking at The Mistmantle Chronicles, Book 3: The Heir of Mistmantle, by M. I. McAllister and illustrated by Omar Rayyan. Published in 2007, It continues the story of the animals of Mistmantle.

Disclaimer: I fully believed this was the final book in the series, when I was reading it. I’m thrilled that there are two more!

And, honestly, I think it’s a huge compliment that the series can stand alone. You could stop after any of the three books I’ve read so far, and be satisfied.

This book features Mistmantle dealing with a lot of disasters– including plague, floods, and a kidnapped princess. It also features extra attention to Urchin’s friend Juniper. Watch out for more detailed spoilers ahead.

I loved this book, possibly even more than the previous ones. I’m so, so impressed with McAllister (and the illustrations by Rayyan) and the world she makes. The imagery of parties and celebrations is beautiful, and it makes you understand why this place is worth defending. We finally get to see Crispin as king, which is cool. Also, Rayyan puts human emotions onto animals without veering into uncanny valley for me.

We also get AWESOME things like Urchin doing the Dark Knight Rises jump out of a deep hole. I love stories about rodents so flipping much.

It’s also kind of revolutionary, to me, to have a children’s fantasy book where the enemy is fear. There’s no dragon to kill or evil king to dethrone. Sometimes it’s a heat wave, or it rains too much, or the water is polluted. Then, people turn to look for a villain, but there is none.

I don’t want to be too light about it, but, I really did see commonalities with COVID. Some people turn on Queen Cedar, saying she brought the plague because she’s not from Mistmantle.

There’s also a conversation with Fingal the otter that I thought was well done. He spends the first half of this book extremely excited about his new boat. Then, it’s smashed in the storm. Two older otters are trying to console him, but he puts it in perspective. He says it’s not a very big deal compared to the animals who died or lost homes. You can be upset by both, while also knowing one loss is larger. I thought it did a good job of showing all the different scales of loss.

And, uh, if you want to be a bummer… they have a lovely scene at the end where peace is restored. The monarchs have a big court. They say a general “thank you” to the healers. But no one gets a special reward (despite other characters getting wreaths and titles). Sounds familiar. Yikes.

Back to losses, yes, they do have actual losses. Two major characters die, including Juniper’s mother Damson.

I liked the writing of that part. He actually lies to his dying mother, so that he can hear her final confession. Yes, it’s relieving her of stress, but he’s also posing as the priest to do it. That’s morally ambiguous! Plus, there’s the actual confession itself, which is that his father is Husk (the villain of the first book).

We get two freaking amazing quotes afterward, from the priest Brother Fir:

“You hate yourself now because you heard Damson’s confession. If you had not done it, you would hate yourself for that instead.” Dude, that’s intense.

And after Juniper says he can’t continue, Fir says “You can’t yet, [...] but you will. Life consists of doing the impossible”.

I like both of those a lot!

Juniper later admits he wanted to die saving people from a landslide, so that he could do something good with his life. Dang, again.

But then the adults and Urchin tell him he’s worth it, and he confronts his feelings about jealousy and becoming like Husk.

There’s even a conversation with a young hedgehog about why it’s not okay to hit people. I know that sounds very basic, but it’s all so mature! Especially when a lot of fantasy stories are about how cool it would be if we could hit people.

We get a description of children playing a game where you say “find the King, find the Queen, find the heir of Mistmantle”. Then their parents hush them and basically say “that’s not appropriate right now”. That broke my heart, gently.

Going back to the paranoia, yes, the real antagonist was inside us all along. It’s fear. But even the three animals who represent the grumblings and negative sentiments are pretty sympathetic. One of them is a young hedgehog who is clearly just trying to fit in.

Also, the suspicion toward the queen is extra heartbreaking because the king and queen are missing their daughter. McAllister really shows the effect it has on the king and queen to lead through all these problems and keep up the search for their child as well. At one point Cedar reveals she’s depriving herself of sleep because she’s having nightmares. That’s such an excellent parallel with the villainous couple in book one!

About the daughter… She disappears very early on. I appreciate all of the Mistmantle books for not beating around the bush. We don’t spend a lot of time wondering where she went, either. We know an old squirrel, Linty, took her.

Linty is an interesting case. She is old, and confused, and she lost two children to the culling. I love that problems from the first book continue to be relevant. Of course a policy like that is going to leave lasting scars on the population! That trauma is why she confuses princess Catkin for her own daughter, and tries to hide her away.

I love these books, so I want to give them the benefit of the doubt. Yes, if you have to ask, then it’s probably ableist.

But I do admire this book, especially one from 2007, for not saying she’s evil. There’s a good paragraph near the end about how things are never complete and never perfect, and it’s ridiculous that Husk tried to eliminate any different animals from the island. They also say near the end, “There’s always a reason for animals to behave the way they do. It may not be a good reason. It may be a very bad one, or an insane one, but there is always a reason.”

It’s really beautiful for children’s fantasy to have that message.

By the way, that quote was partly in reference to Husk. Juniper leads two friends into the deep tunnels below the island so that they can find Husk’s body and prove he’s dead, once and for all.

But even when they do that, his broken bones and shattered gems are more sad than anything. It’s a tragedy that this guy could have been a good captain, and succumbed to evil. There are a few witnesses to confirm he’s dead, but they make a point that they don’t want to turn his body into a show. Plus, they make the point that good things did come from his life, like Juniper.

Yes, it’s still a very light reading level. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not challenging my worldview in a huge way. But oh boy, I want this on more shelves. For the reading level it’s at, I think it really is approaching important themes and treating them very well. It is very good, for what it is.

To end, here are some fun lore drops: a mole uses the phrase that an idea is “stuck in their little skulls like an otter down a mole hole”. Then he slightly apologizes to an otter for the expression. I wonder if they used to fight?

There are some animals who can leave and reenter the magical mists many times. One was an otter named Lochan. There’s also a mole boogeyman called Gripthroat.

Finally… The squirrel who gave birth to Juniper is named Spindrift. I thought that was wicked funny. Even better than Fiverr the rabbit!

You can definitely tell that I am getting more and more invested in these characters. All three books so far are very consistent (right down to the problems of “huge number of characters” and “a boring early-to-mid section”). But I love an ensemble cast and I’m falling deeper in love with the world.

My personal rating: 4.5

My overall rating: 4

1 note

·

View note

Text

Urchin and the Heartstone

We’re going back to Mistmantle, baby!

Today’s review is The Mistmantle Chronicles, Book 2: Urchin and the Heartstone. This was published in 2006, written by M. I. McAllister and illustrated by Omar Rayyan.

Content warning: this review will mention vomit and ableism (again)

This is the first sequel I’ve reviewed. I was not very detailed about the plot in my first review, but this one will get more in-depth. I’m also not going to explain the premise as much since I covered that in the last book.

In this book, the protagonist Urchin is kidnapped and brought to another island called Whitewings. All the while, the Heartstone that Mistmantle needs to crown a king is missing.

I really liked this book’s focus on the difficulties of running the island. The Heartstone is missing because of the bad guy from the last book. And some of the problems on Whitewings are caused by all the soldiers that Mistmantle exiled at the end of book one. It felt like the right balance between new challenges and connecting to the first book. It’s not as simple as replacing a bad king with a good king.

This book had two issues that the first book also had. For one thing, the middle bit is kind of boring. There’s a lot of “character A B C finds out that character X Y Z is doing something”. And we have to talk about the number of characters.

During this book, I started writing a character guide on a bookmark. It was simple things like “Whittle, training as lawyer and historian”. By the end, my scrap of paper was running out of space, with 18 characters, and I was still having double-take moments near the end of the book.

I wonder how this would go over as a visual format. Comics, TV shows, etc tend to be able to get away with more characters.

One other issue I have is with the A and B plots. For a book called “Urchin and the Heartstone” it’s not really about Urchin doing anything with the Heartstone. It’s moreso a book about Urchin, which also has some parts about the Heartstone. Because we had Urchin kidnapped on an entirely different island, it was very hard to care about the Heartstone search on Mistmantle. It sort of just deus ex machina’s itself into appearing, once he’s back home.

And speaking of deus ex machina, the bad guys' castle sinks into the ground at the end. There's no final confrontation.

Urchin is kind of a MacGuffin in his own way. People on Whitewings want a Marked Squirrel, so they take Urchin because his fur is mostly white. He's central to the plot because the bad guys decided he was central to the plot. It does make me wonder why the cover doesn’t show him that way, though. He’s pretty obviously a plain red squirrel on the cover.

All that said… I loved this book. It’s an excellent sequel to an excellent book!

So, let’s list some of the great things.

For one, the reunification at the end of the book really is delightful. Too many characters or not, I love this cast. And it’s so heart-warming to see the whole island celebrating the heroes’ return. After he spends so much of the book trapped alone in a tower, Urchin “was back among animals who hugged you and squashed up beside you and didn’t mind much what you smelled of”. D'aww.

Another cute image is children making snow-squirrels with tails that fell off.

I also think it’s very notable that this book doesn't have many evil disabled people. So often in children’s books, especially in animal books, villains have scars or mental illnesses. There is some of that, but it’s much better than the average story in my opinion.

Ableism, or generally fear of difference, is always a villainous trait. Urchin is called a freak on Whitewings, even though his fur is just a different color.

There’s also a pattern where the priests of islands have some kind of disability, like Brother Fir on Mistmantle having a limp. Juniper is another priest-like squirrel. He was hidden away from the culling because of his turned-in paw, and he also has a lung condition.

Generally, I admire that McAllister tells a solid good-versus-evil story. There’s powerful imagery of dust, decay and death for the bad guys. But, there are still gray areas, such as Scatter the squirrel deciding to be loyal to Mistmantle instead of Whitewings. That doesn’t mean she’s automatically innocent, though. The book doesn’t put everyone into a box of either good or evil, and it doesn’t completely ignore someone’s problems if they’re on the side of good.

I do feel obliged to address the inter-species biases… But frankly, I think this book handles them excellently! There’s a moment early on where a squirrel says otters and moles would rather be in the water, or underground, than rule the island. That got my hackles up.

But, after a second reading, it’s not the text itself saying that. It’s the characters. They’re not treating that opinion as fact.

Later, there’s an attempted coup by hedgehogs. I was very surprised about how firm the book is about their “hedgehogs are the only ones who should be in charge” rhetoric. Basically everyone, hedgehog or not, shuts them down immediately.

I appreciate that because, in real life, there are biases. There will be prejudice, and it’s more realistic to show people working through it than to show none at all.

Also, it’s cool that the dynamics vary over time and in different places. Whitewings has moles, hedgehogs and squirrels, but no otters.

A cool piece of worldbuilding from this book was the way the Heartstone works. It jumps out of your hands unless you’re worthy. Also, the reason people can take mole tunnels between islands is that the tunnels predate the water. Cool! Wind Waker made me love anything where the current world is just a flooded version of the old one.

This book had swans, like the last one. But here they are basically mounts. I don't even think we directly hear dialogue from them, even though last book had an island ruled by swans. Weird.

Also, I am pretty sure these guys are human-sized with human lifespans. But, they mention a dead sparrow on a kind of stretcher, at one point. Not sure what that means. Are sparrows the same size as the people? A human doesn't need a stretcher to carry a dead sparrow.

One final note, since I talked about it in the last review: an early chapter of this book had a squirrel throwing up. Wow… they don’t just have human abilities of language and tool-making, they can also vomit like us…

My rating: 4

Overall rating: 4

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Owls, Predators, Prey, and Relatability

I’ve been rereading Kathryn Lasky’s Guardians of Ga’Hoole series recently. It’s fantasy about owls, a la Warriors.

This is not a review. Even though the books have plenty of mice and other small mammals (as food), these are not rat books by any stretch of the imagination.

Still, I have been thinking about xenofiction as a whole— the idea of writing from other species’ POV.

In my childhood, the two biggest series that really got into other species’ heads were Warriors (cats) and Ga’Hoole (owls). I think that’s notable, because when I’ve written my own stories from a rodent’s perspective, it’s pretty difficult.

One great resource for how rats, specifically, experience the world is this website. Basically, they have poor vision but great smell. They also rely a great deal on touch and on their whiskers.

Cats and owls are active at night because they can see in the dark— rats are more likely to be active in the dark because they simply can’t see well even if it’s bright out. They’re also very near-sighted.

One of the first things that makes it easier to relate to predators like owls and cats is that they have senses like ours, or better. It’s less difficult to imagine seeing through an owl’s eyes (and hearing through an owl’s ears, etc) because their most important senses are comparable to our most important senses.

Humans primarily experience the world through sight, and then through hearing. We have language to describe it, too. Even if I can’t hear a mouse’s heartbeat or see by the light of the stars, I can imagine that.

Meanwhile, there’s no good equivalent to a rat sensing the world through whiskers. How do you describe a scene, or a character, when vision isn’t your primary sense? And neither is hearing? We don’t distinguish each other by how we feel or smell.

We have so few words to describe smells, and absolutely no language for “feeling something with whiskers”.

We are oriented toward sight and sound in so many ways. If I wanted to suggest that a character was tough (and maybe someone to be wary of), I could say they have a raspy voice or a towering demeanor or a dozen different facial features, or expressions, or postures. If you had the same character to describe by smell or feel, how would you do that? “They smelled kind of threatening”?

Or, if I’m describing a conversation, I might say “they frowned” or “he looked away” or “she bit her lip”. We don’t have smell-based ways to indicate emotions or thoughts.

Heck, even “feel” is an annoying word because we so often use it for emotions instead of actual tactile sensations.

Now, in fairness, there are plenty of harder comparisons in the other books I mentioned. There’s no human equivalent to cats leaving scent markings on their territory, or owls feeling a landscape through the air currents that rise off of it. Ga’Hoole is full of excellent owl words like “yarping” (spitting up a pellet), or “wilfing” (appearing to shrink because your feathers lie flat).

I will also argue, though, that predators are more relatable because of philosophy.

Owls and cats are predators, like humans. Personally, I’m a vegetarian, and I don’t hunt for anything. But I still have far more in common with predators in how I experience the world.

We’re programmed for this by our biology, in so many ways. We have binocular vision, to better focus on one object in front of us, instead of two wide-set eyes for wider field of view.

Even if my sense of smell is much poorer than a cat’s, I’ve still followed my nose to food plenty of times. But I have never used my sense of smell to avoid a predator. Or, for that matter, my hearing or sight. Because I’m a human! I’m not prey! And neither are the owls and cats in these books.

Meanwhile, if you read about how small mammals experience the world, it’s a lot of focus on staying alive. Mice show up plenty of times in Warriors and Ga’Hoole… as food.

There’s even a way that being a predator feels noble, to humans. National animals are usually not prey animals. It’s raptors and lions and other beasts that we think of as “on top of the food chain”.

Here’s where we return to specifics about Ga’Hoole. In the same way that other fantasy loves having benevolent kings, the fact that all the owls are predators provides a lot of opportunities to (ostensibly) show who’s good and who’s bad.

Nest-maid snakes in these books are a whole thing. It’s a real scientific fact that sometimes owls will bring a snake back to their nest, not eat it, and enter a symbiotic relationship. You could call it commensalism (the snake is benefitting from shelter and eating the bugs in the nest, and the owl is not harmed or helped) or maybe mutualism (the owl gets a clean nest so they both benefit). It’s definitely more like mutualism in Ga’Hoole because they’re anthropomorphized and they like having clean nests.

The issue in Ga’Hoole is that it’s a whole serving class thing. Like, they imply snakes don’t have souls? They could have made it cool and normal but instead repeatedly say that snakes aren’t on the same level socially as owls are. It’s a whole thing.

And, more importantly, they eat snakes! That’s another real scientific fact. In the earlier books they have a few conversations about how the main character, Soren, was raised to never eat snakes. His friends give him grief about it, but that’s the principle he has. It’s good manners.

Think about it, though. It’s seen as noble that he could be eating snakes, and he’s refraining from it.

There’s another conversation about a starfish, and how it would be wrong to bring it home as a decoration. Because that would be killing for decoration, not for survival. They also clue us in that someone is evil when she tortures a mouse instead of just eating it. That’s a huge taboo for them.

I guarantee you that rodents are not having these conversations!

In the same way that we’re conditioned by a million stories to love gentle royalty who treat their servants well (even though, let’s be real, monarchy is a really bad system of government) … I think we’re taught to relate much more to predators than prey.

It makes sense. Why fantasize about being a meal for everything on the face of the Earth, when you could fantasize about being king of the beasts?

Of course, Watership Down is a very notable exception to this. Rabbits aren’t classified as rodents, but I promise the Watership Down review is coming.

Richard Adams stuffed that book with the rabbit outlook on the world. They have words like “silflay”, because of course they’d have a verb for “to go above ground to feed”. They have words like “embleer” as a curse word meaning “the smell of fox”, and it all reflects that they are prey animals. They spend a lot of their time thinking about all the forces that can kill them.

In its own way, playing up the vulnerability makes the characters seem even stronger. How can you not root for them, when they can’t count past four and everything wants to eat them? Even the simplest task is monumentally heroic.

I don’t have a larger conclusion beyond that. Just, that even if we’re technically more closely related to rats… it might be easier for us to relate to owls. But how much of that is innate, and how much is a cultural desire to see ourselves as the ones on top of the food chain? A more honest look at nature sees it as a food web. Everybody decomposes, and there’s no species on top of it all.

As a caveat (cat-veat?), I haven’t read Warriors in many years. And I haven’t finished my reread of Ga’Hoole yet, either. There’s plenty I could have missed.

Also, forgive the inelegant phrasing but: my senses are what people consider typical. Not everyone relies primarily on sight and hearing, and I’d love to hear other peoples’ perspectives.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Urchin of the Riding Stars

This is gonna be a long one, because I liked this book!

Content warning: this review will discuss culling “unwanted” parts of the population, and vomit.

Urchin of the Riding Stars is the first book in the Mistmantle Chronicles. It was written by M. I. McAllister and illustrated by Omar Rayyan, and published in 2005.

The book is about the island of Mistmantle, which has a castle and magical mists around it. The protagonist is a squirrel named Urchin. That’s a little confusing since urchin is also a term for hedgehogs, and this is a world with hedgehogs, red squirrels, otters and moles… but that’s his name.

He is an orphan with a prophecy around his birth. He’s also different because he’s honey-colored instead of red, except at his ear- and tail-tips. Yeah, it’s one of those books. It’s not challenging writing, since it’s meant for children, and personally that was just what I needed when I read this.

“Fantasy with small woodland creatures” is a relatively small genre, but this book is one of the best examples of it that I’ve read. This is the first book I’ve reviewed that is truly in that niche, so it’s a great opportunity to talk about the genre as a whole.

One thing that I think is notable is the violence. My opinion is that having little critters, instead of humans, lets you get away with more in a children’s book. The prologue is about a mother in labor, and she’s dead by the second page. Shortly after that, we hear about culling “undesirable” babies. And then we see the body of the prince, a baby hedgehog, after he’s been stabbed. That’s all within the first three chapters.

Some notes on their level of anthropomorphism:

Clothes are optional. They wear them for special occasions, or for warmth.

They might be human-sized? There’s an important detail about marking leaves with claws, like a signature. That implies the leaves are hand-sized. And, the book cover has a sea urchin next to Urchin, and it’s sized like it would be next to a human.

They have priests, monarchy, and marriage. Fantasy often has those elements and you take it as a given, but when there are no humans it does feel a little more odd.

I’m not certain if they live human lifespans, or if they age like their actual species, but it seems like human aging.

Generally, their species matters a lot. Squirrels easily leap, otters swim, moles are short-sighted. At points they use smell to see who has been in a place, and characters walk on all fours. They use claws or teeth like knives.

Overall, I’m a huge fan of this. I like that they aren’t just humans with flavor text. Using claw marks like a fingerprint is pretty unique.

They also drink alcohol. There’s a great deal of giving the king wine so he’ll be drunk and look bad, and then other characters try to give him spring water instead… You can also tell that McAllister loves the word “cordial”. They talk so much about cordials.

I mention that because squirrels probably wouldn’t drink alcohol in real life. Rodent’s can’t vomit, so mice and rats don’t drink alcohol.

People aren’t trying to poison squirrels in the same way, but I’m pretty sure in real life squirrels would not drink alcohol. I do know other animals drink alcohol. I’m less sure about otters, moles, and hedgehogs. Two minutes of internet searching didn’t find anything other than a few cool pictures of Sonic.

They imply a kind of racial hierarchy. That’s pretty common in fantasy, and it’s obviously a whole conversation.

What I found interesting was that it seems to have changed, over the years. At the time of the story, the king is a hedgehog, and squirrels could be considered as second in power. The usurper is a squirrel who wants to be in control. Then, broadly, are otters, and then moles. But in the past, there was a legendary Old Palace made by moles. And even before that, a squirrel was king. There’s also an assassin mole in the modern day who thinks a mole should be king, instead of a squirrel. I really like that the history is bumpy, in a way. It’s not as simple as “hedgehogs always get to be king”. We have a little bit from different species saying “we’re the best”.

Another thing I appreciate is that the person/nonperson distinction is relatively clear. You definitely run into that problem, with books like this, but it’s pretty distinct in Mistmantle.

They kill and eat fish, as well as worms and beetles. Those are clearly not people, and they’re not closely related. It’s not like there are fish-people at the same time as we’re eating fish, or even squirrel-people while we eat rabbit meat.

I’m also tremendously appreciative of what species populate Mistmantle. It would really eat away at me if we had, say, otters, weasels, badgers and hedgehogs (three mustelids and then a whole different family). Or mice, rats, squirrels and moles (three rodents and then the family Talpidae). When it comes to evolutionary closeness, squirrels, otters, hedgehogs and moles feel like they’re on the same level of closeness. It’s just something that really satisfies my brain.

There is some gray area with birds— another island is ruled by swans, who talk. But on Mistmantle they mention birdsong, which makes it sound like birds are just another animal. They never employ the songbirds as spies, or anything. But they also don’t eat bird meat or farm chickens for eggs, so it’s not terribly jarring.

I was pleasantly surprised by the number of female characters. I found myself expecting someone to be “he” and then catching my assumption when the book said “she”. The cast has so many gender-neutral names, like Apple, Needle, Crackle, Spindle, Tumble, and other things that don’t end in -le.

I wouldn’t mind fewer characters, though. Or a list of who’s who.

There’s one case of fridging, IMO. The captain Crispin meets another squirrel while banished, who helps him get through it. But she dies tragically before he returns to Mistmantle. She doesn’t really exist independent of him.

I will say, there’s a bit less sword fighting than I was expecting, and more court intrigue. The middle bit of the book gets a little slow because of the machinations and back-and-forth, but I guess that’s to be expected when it’s Macbeth.

Yes, this book is heavily drawing from Macbeth. We have a traitorous murdering couple who aspire to the throne. The bad guy is supremely confident because he thinks the one thing that could stop him is impossible. He is extremely sleep-deprived because he has nightmares about the murder he’s done.

It makes me really happy to think of all the kids who grew up, read Macbeth in English class, and thought “hey wait a second, this is just like that squirrel book!”

Another small note- squirrels do a lot of eavesdropping and rumor-spreading in this story. Intentionally or not, it’s reminiscent of Ratatoskr! That’s the squirrel from Norse mythology who runs up and down the World Tree sending insults from the bird at the top to the dragon at the bottom.

There’s kind of a lot of baby-culling content. I personally wouldn’t have included so much in a book for young people but, hey, whatever works, I guess?

I would say it’s broadly a good depiction. The good guys want to save the babies even though the bad guy wants to kill them for being “too weak”. The language they use is derogatory, but I can sign off on the overall premise of hiding away the children so they can survive. That’s good.

I really like that Urchin is good with children. That’s a very endearing trait, especially from an orphan who was raised by a community. I don’t know if a young reader would feel the same way, but I liked that he was nurturing in that way.

This book also made me think about connection with nonhuman protagonists. Sometimes people think that a nonhuman protagonist is hard to relate to. But, you’re telling me we meet the hero as a baby squirrel shivering in the cold? You’re telling me we gotta defend a baby hedgehog? Of COURSE I’m attached to that character! Obviously I’m rooting for him!

Some other fun worldbuilding things:

I already mentioned the leaves-as-signatures. There are also capital-T Threadings, which I’m curious about for the future books. They seem like just tapestries that tell a story, but it’s capitalized. So they have to be important!

One of the coolest things is that “falling stars” is not metaphorical. Urchin is “of the falling stars” because he was born on a night when the stars leave their orbits. That’s freakin’ sick!

Also, the illustrations are well done. They’re simple and small, at the head of each chapter, but they get the job done. Good job, Omar Rayyan!

One final note about rats, since rats are my faves: the only mention of them is when the swans call squirrels tree-rats. So, that’s treated as a derogatory thing.

Overall, I am pleased as punch with this book. I was approaching it thinking “oh well, it’s in my genre so I might as well read it”. Maybe it’s just that I needed a light read, but oh boy, I really loved it. I would 100% recommend it as an example of little critter fantasy. I’m going to read the next book in the series right away.

My personal rating: 4

Overall rating: 4

0 notes

Text

Beaverland by Leila Philip

Beavers, round two, baby!

Content warning: this review will talk about colonialism and slavery.

The meta-story here is that I recently read Beaverland (in late February and early March, 2024). But, I felt like I had to review Eager first. And, well, now it’s July, but I still read the book relatively recently! So, here it is. Beaverland: How One Weird Rodent Made America was published in 2022. It's a nonfiction book by Leila Philip.

I got very, very excited about this book because my one big gripe with Eager was that it didn't talk enough about the social circumstances and history. This one is more aware! And on top of that, Philips is local to my area! I loved it from the start, for that reason.

I could definitely tell this was someone with a background in English, not science. It was also more focused on the fur trade.

Politics came up more than I was expecting. This book came out in 2022, rather than 2018 like Eager. (I imagine that much of the research for Eager happened before 2016.) Philips writes a lot about being a liberal college professor woman among these conservative hunters and trappers.

It was unsteadying, to me. I want simple good guys/bad guys. Us versus them. But sometimes the trappers are the also conservationists. Sometimes they're doing something I'd consider cultural appropriation, but they come from incredibly difficult life circumstances and that's what's working for them. Maybe they clash with their PETA family members and also hate the NRA. It's complicated.

I'm curious about the process of writing this book, because different chapters felt very different from each other. COVID lockdowns happened in the middle of her research, which probably didn’t help.

Unfortunately, I found the writing a bit disjointed. Sometimes I would be learning about water flow, but then find myself reading a description of some flowers Philips saw. I felt like I got interrupted.

Different chapters often (but not always) talked about colonialism in a self-aware manner, but it wasn't always treated the same. One chapter might be a history of the fur trade, essentially told from European settlers’ perspective, while other chapters really engaged with that history.

I hate to say it, but it felt melodramatic at moments. I wish it had been more concise. One of the chapters is about stone walls, which are classic features of New England. She reveals that a lot of them were made by enslaved African and Indigenous people. That was impactful for me to learn. I didn’t know that, and it’s a fact about something I considered a beloved feature of my home. Unfortunately, I felt like Philip buried the lead so it didn’t land as strongly as it could have.

I know that choosing to write from your own perspective is a choice, rather than trying to be a perfectly objective narrator. Still, it could have been done better.

All this said, I did enjoy the book. And I learned great beaver facts! I might even recommend it more than Eager. Honestly, both are great if you want to learn more about these animals.

Some of the beaver facts I learned: they’re best to trap in the Winter, because in the Summer their pelts are too thin, you can’t use the meat because of parasites, and besides they have kits inside the dam that would starve. Meat from beavers trapped in the Winter is dark, almost purple-red, because it has so much hemoglobin for storing oxygen. The further north beavers are, the deeper the water they need (because ponds freeze over).

Their pelts have more hairs in an area the size of a postage stamp than humans have on their entire head!

In the past, beaver meat (especially the tail) was considered a delicacy in Europe because it was considered “cold”. Christians could eat it on fast days. That’s ironic since previous civilizations had considered their tails as aphrodisiacs. (Bonus fact: did you know alligators are seafood? They’re okay to eat on fast days, too! Go wild, New Orleans.)

Humans find a pinch point in rivers and build very high dams. Beavers like to build low, and they don’t really care how long their dam is.

Maybe this review seemed hard on the book, but I truly did love it. I think it could have been so much more, and I really desperately wanted it to be better.

My personal ranking: 3 (but the first two or three chapters are a 5)

My overall ranking: 3.5

0 notes

Text

Eager, by Ben Goldfarb

I’m back with a beaver book! Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter is a nonfiction book from 2018 by Ben Goldfarb.

As a disclaimer, I read this book over two years ago, in 2022, but I’m working off notes I took when I first read it.

Eager is a bit of a cult classic, in my opinion. No, it's not widely famous, but people who read this book are likely to recommend it. It’s one of those nonfiction books that really cracks your brain open and makes you see the world differently. Goldfarb makes a pretty convincing argument that beavers are on par with humans as ecosystem engineers. He even says we should call this the Castorocene (like how people call this era the Anthropocene).

I found the writing evocative and almost too wordy, which made it hard to read. He teaches about amazing biology facts, which I'll talk more about later. He also gets into their role in human history, with fur trading, and also the way their ecosystem engineering clashes with humans.

The majority of the book is about beaver believers, people who think restoring beavers to habitats could massively improve the world. There's a bucket and a half of benefits, from sequestering carbon, to increasing biodiversity, to catching damaging runoff, to refreshing aquifers.

Predictably, I wanted him to talk more about the colonization and violence of history. That's very relevant when you're talking about conservation and overhunting of species in the United States. But all things considered, it wasn't too bad.

This book might seem a far cry from Desperaux, or Redwall, or the Rats of NIMH. But one of the reasons I'm so fascinated by rodents is that they literally and metaphorically gnaw away at our world. Humans want to impose our order on the world. But as long as a space is well-suited to beavers, they're going to keep coming back, and coming back, and coming back.

We want to put roads in straight lines. We want rivers to be static lines you plot on a map. We want nature to be clean and simple, but beavers upturn all of that.

I also learned about cultural carrying capacity from this book, which is different from biological carrying capacity. Maybe a town has enough space, food, etc, for 800 deer. Long before we hit that number, they're going to exceed their cultural carrying capacity among humans, and the humans are going to get rid of them. Cultural carrying capacity is far more flexible, though. If you educate people about beavers and get them really excited, they're less likely to see them as pests.

This book is also where I learned about culverts. Culverts are unsung heroes! They're basically miniature tunnels that let water go underneath roads. And they're also extremely beaver-prone. But, there are "beaver deceivers" that you can put into dams that will let some water through.

Now that the review section is over, I can tell y’all more of the cool beaver facts from the book:

Did you know about devils’ corkscrews? Such a cool name. These are fossils from the Southwest US that look like a giant stone spiral. For a long time, no one knew where they were from. Maybe some extinct species of plant? But they were actually burrows made by paleocastor, ancient relatives of beavers!

Beavers have an extra pair of transparent eyelids, so they can see underwater. They also have lips behind their teeth for underwater chewing. Their tails can communicate by slapping the water as an alarm, plus they can regulate heat, paddle, store fat, and serve as props when gnawing. Also, do you know why beavers have orange front teeth? They're reinforced with iron! Beavers are so cool!

They are super impressive architects, too. When they're gnawing down a tree, it will usually fall toward their dam so that it will be easier to transport. They don't have to hibernate because their lodges are so warm.

And, did you know why they're called "castor" and their scent is castoreum? It's related to "castrated". People used to think beavers would gnaw off their testicles to distract hunters. In reality, beavers truly are difficult to sex. They have internal genitalia.

Oh, and have you heard about the beaver paratroopers? The US government dropped beavers out of planes because they knew how much economic benefit they could bring.

Okay, this post was 90% just listing the cool facts I learned from this book, and not a review of the book itself. But those are the notes I wrote down. Beavers are really cool.

With the caveat that this was a ranking from 2 years ago:

My personal rating is 3.5

My overall rating is 3.5

0 notes

Text

Charlotte's Web- Templeton's Version

April 1st, 2024

Today’s review is a book by E. B. White. Charlotte’s Web is about a rat named Templeton and the other animals that live in a barn with him.

The opening line is sensational (like with Stuart Little). "Where's Papa going with that ax?" That's so good! It's practically the entire drama and stakes of the book, in one sentence! It's only undercut by the fact that they're not talking about Templeton the rat.

This is a talking animal book. I know you can say this about most talking animal books... but the morality is so bizarre. It's supposedly a bad thing that Wilbur might get eaten. But what about his ten siblings who they sell at 5 months old? If Charlotte the spider can have conversations, why not flies. And the barn has rat traps!

I don't love the treatment of the human girl Fern- her parents are worried about her, because she talks to animals. They talk with a doctor in one chapter, who says "oh, she'll start being interested in boys eventually". And then she does. That's the end of her story. She does grow up and stops talking with animals. Heteronormative, and really everything-normative.

The descriptions are really terrific, though. E. B. White makes me want to live in a manure pile and eat slops, because it sounds so appealing and delicious.

But let's get back to the main character.

The book was decently accurate about rats. Templeton, like real rat species, is mainly interested in food and shelter. He's not popular, but he's not unnecessarily cruel. Just very self-interested. He eats Wilbur's breakfast, he's nocturnal, and has many tunnels. He likes the dump because it has food and hiding places. That's pretty accurate.

Templeton is willing to kill a gosling, and everyone knows it. When one of the goose eggs doesn't hatch, he wants it. He doesn't have a particular purpose, he just wants to have it. I don't know as much about pack rats, but that sounds like pack rat behavior. I don't think of brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) or black rats (Rattus rattus) as huge collectors. (He is probably one of those two species.)

One of the least accurate things is that Templeton is alone. How on earth is there only one rat in this whole barn?

I was really happy for him, when he went to the county fair and got to eat a lot of food. He gets huge! But rat behavior-wise, that's not very realistic either. Some rats definitely feast on foods at big events, but one of the things that helps their species survive is that they're unwilling to try new foods (neophobic). They'll leave things alone for a long time before trying them, because they might be poison.

Even though Templeton says his stomach can handle anything, real rats are incapable of vomiting. So, they need to be very careful about what they eat. A barn rat would not try so many new foods in a new place.

[April Fools aside, this next part is actually interesting to me.]

Templeton is heroic in his own way, throughout the book. But he's not seen that way. His rotten egg bursts and scares the human boy Avery away from killing Charlotte. He finds the words for Charlotte to write in her web. When Wilbur faints from all the praise he's getting at the fair, Templeton bites him so he'll jump up and look lively. He even saves Charlotte's egg case and brings it back to the barn.

He's benefiting from this, like making a deal so he can eat Wilbur's food. But he's still arguably just as essential as Charlotte to save Wilbur's life. It's not even like spiders are so much more popular than rats. But Charlotte is "the size of a gumdrop", which is a very intentional move to make her sound unfrightening. And Templeton has "long ugly teeth".

[okay back to funny mode]

I’m not quite sure why it was called “Charlotte’s Web” and not “Templeton’s Trough”. He’s clearly the most compelling character, and I wish less time had been spent on the side characters like Wilbur the pig and Fern the human.

My rating: 3

Overall rating: 3

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Tale of One Bad Rat

Content warning: this book covers familial sexual abuse, suicidal ideation, and homelessness. The review will get into that. I know the previous book also did, but I promise it won't be a pattern.

The Tale of One Bad Rat, by Bryan Talbot

This is a comic written in 1994. It begins in London and follows a homeless girl named Helen as she heals from abuse.

I am going to get into detail about the story. The actual plot doesn’t have many “spoilers”, but I’ll undress a lot of the emotional moments.

I saw the title at a library, and I took a closer look. Haha, I love rats, so funny… Then the back cover had these reviews about the importance of addressing child abuse, and I realized it was a serious book. I think the book handles Helen’s situation very well. It’s not an easy read, but it’s sympathetic and it shines light on something that people rarely want to talk about.

Something silly about me is that I often get annoyed by book titles with animals. Take Dinosaurs, by Lydia Millet. I get interested, only to read the back cover and see it’s not literally about dinosaurs.

This book was not like that. Helen has a pet rat, she admires them and shares facts about rats, and rats are generally a theme throughout the book. Surprise surprise, she’s the One Bad Rat the story is talking about. She’s unwanted by society and shunned.

I thought she was a boy at first, just based off the cover. I realize that’s intentional— she deliberately has short hair because she doesn’t want to be seen as a young woman alone in the world.

I think that also reflects the representation of homelessness. It was easier for me to imagine a solo homeless boy than a solo homeless girl.

I admire that the book shows Helen’s hair growing longer. I personally just appreciate when media shows characters change over time, but it’s also a good metaphor for her healing. When she’s safe, she is free to grow it out more.

The book used the medium of comics very well. At several points, Helen has intrusive thoughts, like jumping off a bridge. The panels don’t change or anything. You see her do it, then, there’s another panel and you realize she was just envisioning doing that. It felt very similar to my experience. You’re in that current without even realizing it’s happening, and then you jerk back to reality.

Something bittersweet about this book is the kindness Helen receives. She deserves it. She’s taken in by some older kids. I think it’s a little funny how she agrees to pretend she’s sleeping with a boy, so he won't get bullied by the others. It’s very utilitarian. They’re both getting what they need from the relationship. She later finds an older couple to live with, and who doesn’t love found family? It’s very, very sweet. But it's bittersweet because I know so many people don’t have that support.

The healing is really, really amazing. I wrote in my notes that reading this book felt like unclenching a painfully tight muscle. It hurts, but the release and healing is very powerful.

The afterword really made me appreciate this book. In my edition, Talbot talked about his process making the book, and the reception since it was first published. He originally wanted to write a story about the Lake District in the UK. He basically had the protagonist fleeing parental abuse as an excuse to tell the story.

Then, after doing more research, he realized he had to fully address that. It became more central. He says it much better than I can, but the general point is that abuse is far more common than we think. People don’t want to talk about it, but talking about it is the only way we’re going to make things better.

I strongly encourage people to read the afterword here.

Note on language: I know there are many terms to use for unhoused people. I say “homeless” in this review because 1. It’s commonly understood and 2. Helen’s journey is just as much about finding an emotional home as it is finding a roof over her head.

My rating: 4.5

Overall rating: 4.5

0 notes

Text

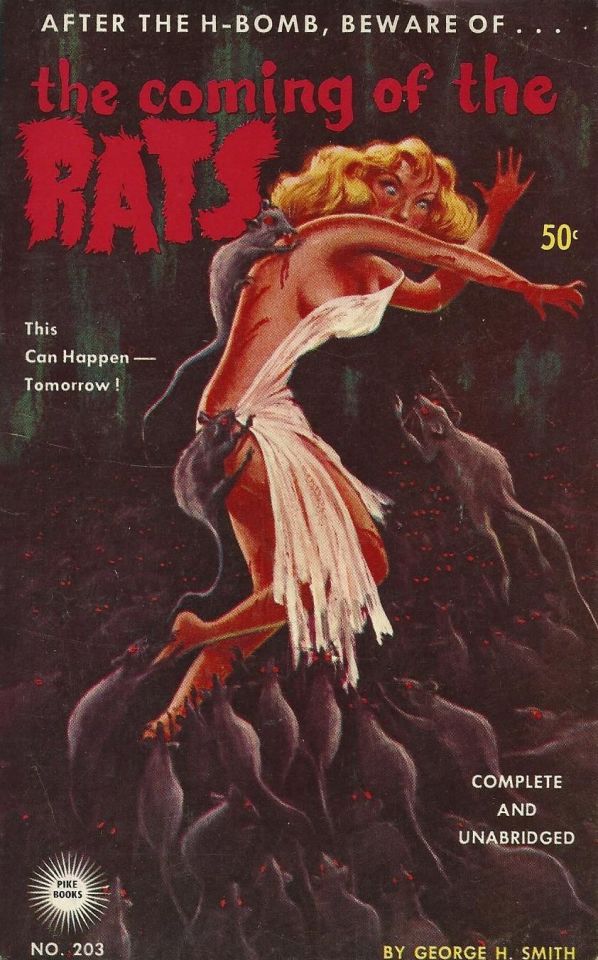

The Coming of the Rats

Content warning: the book I'm reviewing today has a lot of sexual content.

Today I am reviewing The Coming of the Rats, by George H. Smith, published in 1961. It's a science fiction novel about a man surviving nuclear apocalypse.

Image description: The book's cover. It has a skinny blonde woman with her clothes being ripped off by hordes of red-eyed rats. It is 50 cents.

Before I go further, I will say that this book has a lot of sexual violence in it. It is treated badly. That's all I'll say in this review. Also, I'll be spoiling the end, but it's a bad book so don't feel too bad.

So, when I picked the book up (just the title was enough to get me excited) I knew what I was getting into. It was really funny. If you like this sort of thing, then this is the sort of thing you will like. I could write a thousand words taking down this long-dead author's sexism, but I'm not going to waste anyone's time.

Something that surprised me was that it's a near-future book. It takes place in 1963, and was published in 1961. I think of near futures as being a modern trend. Today, technology feels like it's advancing by leaps and bounds. It's easy to set science fiction just a few years from now. But Smith was doing this in the sixties. Early on, his protagonist explains why the year has to be 1963. I can't vouch for the accuracy of his calculations about the Russians' nuclear arsenal, but he clearly put some thought into it.

I find it kind of reassuring to read accounts from the Cold War. (It feels funny to use that name since it wasn't cold at all, for so many people.) I don't think people were wrong to be worried about the end of humanity, back then. But the world didn't burn. We live in scary times now. It's nice to know people were afraid the world would end, and it didn't happen.

One piece of evidence the book cites is that 90% of humans will die if exposed to 400-600 roentgens, and only 50% of rats will die if exposed to 825 roentgens. Again, citation is needed. In the text, it quickly becomes "rats can survive twice as much radiation as humans and live".

In reality, most of the book is set before the bombs fall, and very little of it is about rats. The protagonist spends the first part preparing and trying to convince Bettirose, his coworker, to go with him to his cave in the mountains. Once the bombs do fall, he has some incidents with other survivors and prepares for the rat invasion. He sees the occasional rat and worries about them, but there's no horde until the last chapter. The vast majority is not really about rats. I guess that's a hazard of an older book. I'm used to covers talking about the first 10-20% of a book. But in this one, the rats are less of the premise and more like the climax.

Speaking of the climax, it was just fine. I'm obsessed with rats, and I was happy they finally showed up... but it was an awfully long wait for an average action scene. Something I would have liked to see is more description of the cats, dogs, and weasels the protagonist stores. Throughout the book he collects as many of them as he can, and they're useful in the end because they kill rats. But, compared to the detail given to farming and other preparations, there's never any description of the animals. They say the animals are taking up food, but how much? Dozens of animals are a lot of mouths to feed. And he never mentions taking the dogs for walks, or waste disposal. I'm not talking about animal welfare, I'm talking about them literally being able to survive. If you're going to have tens upon tens of weasels, dogs, and cats, you need to spend most of your time maintaining them. And there's never any description of that. Are they plants?

Also, the very ending is especially bad. It's hard to end a post-nuclear apocalypse story, but this is not the way. After waves upon waves of rats, there's a king rat. The protagonist kills it, and the rest scatter. Eyeroll. Then, there's a few paragraphs, maybe a page and a half, of thinking about the future. He knows the rats will come again, but he'll breed dogs, and make more preparations. That's the end. "I'm confident we'll be ready". Very weak.

If I was hard on this book, well, it's because it's bad. The sexism was really funny, until it stopped being funny. You don't need to read this one. My personal rating: 2.5 / 5 My overall rating: 1.5 / 5

0 notes

Text

Expedition Backyard

Today's review is ...

Expedition Backyard

Exploring Nature from Country to City

by

Rosemary Mosco, Binglin Hu, Ashanti Fortson (color design) Desolina Fletcher (flatting assistance)

I was thinking to myself the other day, “does anyone know what a vole is?” They’re kind of just like… generic rodents. I know the word. But they’re never the center of things, the way that mice are. There’s no famous voles. So, I looked up voles at my local library, and what do you know? I found one book with a vole.

It’s a children’s picture/comic book, about best friends Mole and Vole exploring nature.

The book is gorgeous. I feel like every page blows me away and makes me a better person. I can tell care went into every single one. The wobbly panel borders are comforting.

It’s a love letter to my very favorite kind of nature: backyard nature. Wildlife documentaries are great, but this book elevates the local wildlife. It helps that it’s very New England-based, which is where live, too. The book has a strong message that whether you’re in a rural or urban area, you can find wonderful things.

Mole and Vole are a delight. Their friendship is pure love, and it’s infectious. Mole is more cautious while Vole is more adventurous. They’re a perfect duo.

Mole and Vole hold each other's hands and at the same time say "Time to watch NATURE SHOWS in the house!"

It’s not just beautiful and joyful, it teaches things. They pass by a stone and mention it was dropped by a glacier during the last ice age. That’s real! Glacial erratics are a thing! They casually teach readers that honeybees are actually an introduced species to the US, and there are many species of bees, some of which aren’t yellow-and-black. The end of the book has useful tips on composting, community gardens, keeping birds safe from windows, and more.

A 2-panel spread where we see Mole and Vole walking in the park. They see many types of birds and hear their calls.

At one point, they meet a snake and a spider. I particularly liked those two, because they were characterized as trying to be scary. The DeKay’s brownsnake is a “TERRIFYING hunter!”, who hunts only the most fearsome prey… slugs and worms. The jumping spider calls itself vicious, but the next panel has Vole looking at how cute, small and fuzzy it is.

The aforementioned panels with trying-to-be-tough spider and snake.

I haven’t seen that characterization before, for spiders and snakes. Plenty of media shows them as monsters. Plenty of people who like them will say they’re not gross. But that’s not helpful to someone who’s afraid. So, making them adorable as they try to seem tough is a neat synthesis of those two ideas. The book makes space for being afraid of nature, instead of assuming people will love every second of it.

When I finished, I realized it’s a 5/5 on my personal ranking and on my general ranking. I can’t imagine how it would have done its job better. I wasn’t thinking “this is a 5/5 book” while I read it, because I was only thinking about how delightful it is. I’m incredibly glad I found this book by chance.

Have you read this book, or one like it?

Sorry I still have no scanner.

0 notes

Text

Stuart Little

I just recently read Stuart Little, written in 1945 by E.B. White, so I'll review it here as my first review.

Beware! I will be talking about plot details, including the end. And a big part of the experience for me was that I didn't know where the story would go next.

Overview

It's about a boy(?) named Stuart Little. It's hard to say much more than that, because there's no central thread. I can pitch Charlotte's Web to you: there is a pig and the barn animals, especially the spider Charlotte, are trying to keep him from getting eaten. This book, though? It's just... about Stuart Little.

It has a really great opening line: "When Mrs. Frederick C. Little's second son arrived, everybody noticed that he was not much bigger than a mouse." In the first edition, the line is that he "was born". The book isn't very specific about whether he's a mouse, or a boy who just looks like a mouse.

My Thoughts

I loved it, and I don't know what to make of it. I am glad such a strange book is considered a classic, even if I don't understand why. It's hilariously matter-of-fact, almost deadpan. Yeah, he could walk as soon as he was born. He's in love with a bird. There's an invisible car. Deal with it.

I really, really loved the bits about how Stuart lives. Early chapters explain how he gets clothes, how he gets around, and the challenges of raising a mouse-boy. It's actually a great message. People don't question his different needs, they just accommodate him. I could read an entire book about the challenges of being the size of a mouse in a world built for human-sized people. And I did! And I want more!

There's a great deal of attention paid to his clothes. From the first chapter: "Before he was many days old he was not only looking like a mouse but acting like one, too-- wearing a gray hat and carrying a small cane." Does E. B. White know what a mouse is? Is that the problem? A few sentences later, Mrs. Little makes Stuart "a fine little blue worsted suit with patch pockets in which he could keep his handkerchief, his money, and his keys." At another point he wears "a pepper-and-salt jacket, old striped trousers, a Windsor tie, and spectacles." And the whole book is like that. Stuart is a little gentleman. The world's smallest dandy.

It kind of reads like E. B. White wasn't editing, at all. Pure 'yes and', no revisions. Or, it's like a group storytelling game, where everybody contributes one sentence at a time.

After a few chapters of little adventures, he decides to run away from home to find the bird Margalo. And we never see her, or Stuart's family, again.

There's a non sequitur chapter where he becomes a schoolteacher for a day, and I don't think it relates to anything that comes before or after.

There's an invisible car, like I mentioned. Unironically, halfway through the book, Stuart's doctor friend gives him a miniature car that can turn invisible. What? That wasn't part of the premise!

There's also a human girl, the same size as Stuart, in the later part of the book. Where did that come from? She's small like him, but she doesn't look like a mouse.

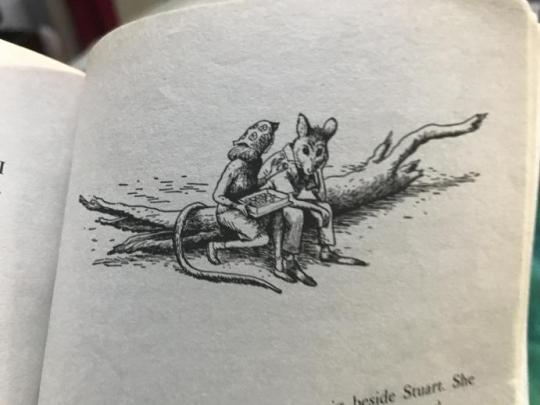

It's like the reverse of Chekov's gun. Something new could be introduced at any moment, and something could be dropped at any moment. To be crystal clear, I enjoy this. I like the unpredictability. And, it must be well-written somehow, because even with how odd it gets, I never lost my suspension of disbelief. This would be an excellent exercise in storytelling. I'd ask children what they think will happen in the next chapter. Even the ending is a kind of curveball: a telephone repairman talks for a long time about how great North is, as a direction. And then Stuart keeps driving. Overall, I liked it, even if I don't know if it's well-written. It seemingly breaks a lot of rules about writing. It's profoundly weird from a storytelling perspective, so I'm glad it's somehow a popular book. I give it a 3/5 overall, and a 4/5 for me, personally. For further reading: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/07/21/the-lion-and-the-mouse This article talks about children's books and how Stuart Little was part of a fight over what children's book should be. Anne Carroll Moore is a fascinating historical figure. Sorry, I have no scanner, so here's some pictures of Garth Williams' illustrations.

Stuart is on a branch with the human-shaped girl, Harriet. He's dressed like a human, but he has a tail and a face like a mouse.

In the second, she's watching him swim and his furry body is on display as he looks at her. P.S.: Since my specific focus is on rats, I feel like I should bring up the one major time they're mentioned in the book. During the schoolteacher chapter, Stuart gets very mad at being compared to a rat. He's very distinctly not a rat, and doesn't want to be mistaken for one.

0 notes

Text

HEY-OH! This is my blog.

I am Eli, and this is my blog. I just made it. Rats are my special interest, and I like fantasy with lil forest critters. Think Rats of NIMH, The Underfoot, Redwall, Mouseguard, the like. I'm going to post reviews of those kinds of books, on here. This blog was previously on Blogger https://ever-rat.blogspot.com/ I have just made a Tumblr acct for the first time. I'll learn as I go.

2 notes

·

View notes