My name is Steph and I’m a recently graduated veterinarian in Australia. Follow my veterinary adventures around the world: working with wildlife in Africa, surgical training in Thailand, platypus research in Tasmania, desexing street dogs in outback Australia, and fighting rabies in rural India!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Phone Interview Survival Guide

Applying for a veterinary job in a distant location is nothing short of terrifying. You don’t entirely know what you’re getting into, there are far more factors to consider (accommodation, lifestyle, work visas and flights, to name a few), and there is much more at stake if the job doesn’t work out. Even more concerning, you need to make a judgement of a vet clinic based on a half hour phone call!

In the last week, I’ve had 5 Skype interviews for veterinary positions in the UK. This was an entirely new experience for me and I had no idea what to expect. I shook and stumbled my way through the first interview, and by the last, I was interviewing like a pro! Ok, maybe not that great, but I wasn’t nervous anymore!

So if you’re about to brave a phone interview, here’s what to expect and how to succeed without really trying:

Arrange a day and time. Make sure they are aware of the time difference and organise to talk at a time that suits you both. To avoid any confusion, specify whose time you’re referring to (for example, “I’ll call you at 3pm your time”).

Decide on the call medium. Skype, FaceTime, WhatsApp and a straightforward phone call are the obvious options. I decided on Skype because everyone has it (even the oldies!), it’s on the computer (so you can be hands free), and you can see each other (making it as close to a face-to-face interview as possible). Share your number or username ahead of time. I recommend checking that you remember your password and testing your camera beforehand too. To video call or not to video call? I’ve had a couple of uncomfortable interviews where my camera was on and theirs wasn’t! Nothing makes you feel quite so exposed and vulnerable as being on display while talking to a black screen! To avoid this, you can answer the call by clicking on the normal phone button (not the video call button), say hello, assess the situation, and turn on your camera once you can see them.

Be punctual. Punctuality is my middle name, so I found myself sitting in position 15-30 minutes before the scheduled interview time! That is obviously a bit excessive, but make sure you’re ready at least 5 minutes before. You can judge the clinic by how soon after the arranged time they call. I had one interviewer call 40 minutes late, making it 11:40 pm my time! I was tired, irritated and not impressed!

Be polite, friendly and smiley. This will go a long way towards making a good impression. Employers seem to place more weight on personality than experience. After all, they have to work with you all the time! My lame attempts at humour (like when I was asked “what’s your weakness” and I replied “interviews!”, or when they mentioned working in snow and I joked “what’s that?”) made everyone laugh, lightened the mood and relieved the tension! … And if they don’t laugh, do you really want to work for them?

Make eye contact. Easier said than done with video calls. I had a couple of interviews where the interviewer didn’t have their camera on, and another where the interviewer’s camera was sideways! Not ideal. Try to look into your camera when speaking and avoid looking at yourself or the interviewer’s face.

Be prepared. As with any interview, re-read the job advertisement, research the clinic, stalk them on social media, and ask people! Get to know as much about them as you can. Google common interview questions and write down answers beforehand so you have some pre-prepared responses. Common questions I encountered were: “What experience do you have with smallies/production/equine?” “Why do you think you would be a good fit for our team?” or “what can you contribute to our team?” “What would you do in this scenario?” (I was asked to talk them through a cow caesarian!) “What are your long term plans?” “What are your special interests?”

Take notes. All of my interviews started with the interviewer launching into a ramble about the position, practice, salary, benefits, hours, out of hours rota, holidays, etc. In my first interview, I tried to absorb all the info and only realised once I’d hung up that I couldn’t remember a thing. It’s a good idea to have a pen and paper handy, and just jot down some numbers while they’re talking, even if not looking at the page. Alternatively, if you can find a way to record the conversation, it’s great to be able to go back over the details when comparing practices later.

Ask questions. I was asked if I had any questions in every one of my interviews. Prepare a list of questions beforehand. This shows you’re interested in the position and have given it some thought. Remember interviews are a two-way street! This is your chance to see if the position is the right fit for you. Some great questions I like to ask include: “What is the split of animals your practice sees (smallies/production/equine/exotics)?” “What support and mentoring do you offer to new graduates?” “How long did your last new graduate stay?” “Do you offer accommodation and a vehicle?” “Do you offer/encourage continued professional development?” “When would you like your new vet to start?” “How long are your standard consult times?” (this one gave me an idea of how chaotic the clinic is likely to be - I’m yet to test this logic but I’ll keep you posted on my findings)

Thank them for their time. Remember they likely had to sacrifice their coffee break or record-writing time to speak with you. They will probably offer to answer any more questions you may think of via email. They should also tell you when you can expect to hear from them.

I hope these points will shed some light on what to expect and help you nail those phone interviews! Take a deep breath and smile. In a few days, your inbox will be flooded with offers of employment! Good luck!

#vet#vetstudent#vetschool#veterinarian#interview#vetlife#job#jobapplication#vetmed#medlife#medstudent#phoneinterview#phone#jobsearch#jobhunt#employment#veterinary

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Beating Heart Cadavers

Last year we had a terminal (non-recovery) fish practical which required fresh cadavers. The fish were humanely euthanised with an anaesthetic overdose. As an added precaution, the gill arches were then cut (causing them to bleed out and preventing respiration) and the spinal cord transected (obstructing electrical signals from the brain). Despite these measures, the fish hearts continued to beat for several minutes. Even once removed from the rest of the body, they continued to beat. As you can imagine, it was quite disconcerting, but we were all reassured that the fish were, in fact, dead and unable to feel any pain.

I hadn't given it another thought until I came across this video yesterday and my curiosity got the better of me. So I did what any ex-vet student would do - RESEARCH!

The heart continues to beat because, unlike most muscles in the body, the heart doesn't rely on electrical impulses from the brain, but instead generates its own electrical impulses from specialised cells within the heart. These cells can continue to fire as long as they have sufficient ATP (energy). Apparently this phenomenon can (and does) occur in humans too.

So then I started thinking about the process of dying, how "death" is defined, and what criteria are used to determine death. Is a patient dead when the heart stops beating, or when respiration ceases? Are they dead when there is no longer conscious thought, no response to stimulus, or an absence of electrical activity in the brain (“brain dead”)? Or a combination? It’s clearly a controversial question because death isn't a single event, it's a process! Cells, tissues and organs die at different rates.

While I was reading, I came across the term "beating heart cadaver" which I hadn't heard of before. A beating heart cadaver is a body that is pronounced dead (by the brain dead definition), yet retains functioning organs and a pulse. Because the brain stem is dead and can't control ventilation, the body is connected to a medical ventilator which keeps the blood oxygenated. This blood is circulated around the body by the heart, which continues to beat independently. Beating heart cadavers are known to "survive" for up to 20 years! These cadavers are even capable of maintaining pregnancies! Fascinating right?

In the vet industry we routinely determine whether an animal is alive or not simply by feeling for a pulse and using a stethoscope to auscultate the heart. I suppose if the heart ISN'T beating, the animal is definitely dead. And with pharmacological euthanasia, the cardiovascular system is likely to be the last to go (after nervous and respiratory systems). Even so, assessing cardiovascular function now seems an over-simplified means for determining death in veterinary patients. I will certainly be giving more thought to my death criteria from now on.

If you're as fascinated by this topic as I apparently am, I found this interesting BBC article which is worth a read: http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20161103-the-macabre-fate-of-beating-heart-corpses

Check out the videos of my fish practical here: https://www.instagram.com/p/BtaeSQKnW-a/

#vetschool#vetstudent#vet#vetlife#vetmed#medical#medicine#cadaver#pathology#anaesthesia#life#lifeanddeath#death#dying#beatingheart#beatingheartcadaver#euthanasia#veterinary#veterinarian#doctor

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

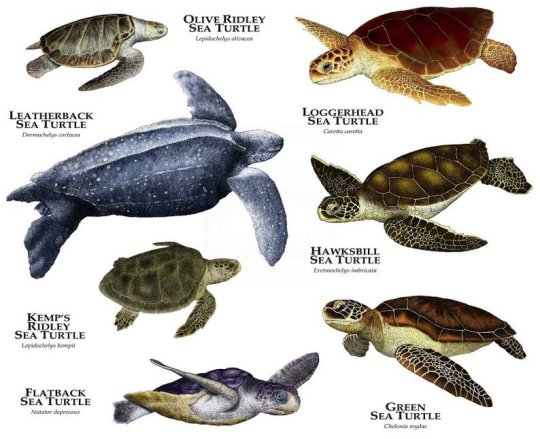

Seven Species of Sea Turtle

Last year I was lucky enough to visit Sri Lanka and spend some time on the beautiful coastline. The water was so crystal clear and I was delighted to spot the odd turtle foraging close to the beach. I spent literally hours with my eyes glued to the water, waiting for them to pop up for a breath so I could catch a glimpse or snap a pic.

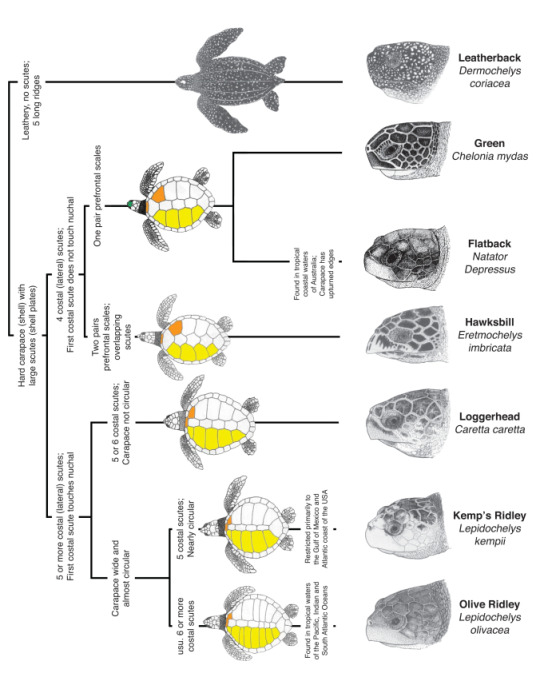

There are seven species of sea turtles currently in existence: leatherback, green, flatback, hawksbill, loggerhead, kemp’s ridley and olive ridley. Of these, six inhabit Australian waters. The IUCN classifies the hawksbill and kemp’s ridley turtles as critically endangered, the green turtle as endangered, and the other four as either vulnerable or data deficient. Some of the threats to sea turtles include poaching, bycatch, development, plastic debris, oil spills, climate change, predators and disease (namely fibropapillomatosis).

While the leatherback turtle has a unique appearance due to its size, huge front flippers and lack of a hard shell, the other species are a little more difficult to differentiate. Identification is done by counting the costal scutes (bony plates on the shell) and the pairs of prefrontal scales.

Looking at my turtle photos, I can count only one pair of prefrontal scales, which narrows it down to green and flatback. The latter is only found around the northern coastline of Australia, SO green sea turtle it is!

If you’re interested in learning more about sea turtles or want to contribute to their conservation, there are countless programs out there for vets, students, nurses and budding conservationists, where you can get hands on experience looking after turtles in rehabilitation centres, collecting data for research, protecting turtle nesting sites or cleaning up their habitats!

#vet#vetstudent#vetdownunder#veterinary#vetschool#vetmed#vetlife#vetnurse#wildlifevet#conservation#turtle#seaturtle#wildlifephotography#srilanka#reptile#wildlife#travel#vetstudentlife#medicine

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Anatomy of Vet School

Most of my posts from the past year have been about my final year rotations and my experiences in each. Someone recently asked me to explain what rotations actually are and what they involve. I thought I’d take this opportunity to demystify the structure of vet school to any aspiring vet students out there. The following is based on my course in Australia, a 5 year combined undergraduate (Bachelor of Science, BSc) and postgraduate (Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, DVM) degree, although many vet schools follow a similar system.

FIRST YEAR

Who am I and what am I doing here?

First year is, to put it bluntly, a bit of a waste of time. It comprises basic foundation units which are not at all veterinary related. I had cell biology, statistics, agriculture and even a unit called ‘What is Science?’, which left me more confused about science than before I began! I found myself twiddling my thumbs waiting for this year to be over so I could learn something relevant to my chosen profession.

The next few years of vet school are dedicated to learning (and cramming) theory - all the ‘-ologies’ (physiology, parasitology, pharmacology and so on). This is accompanied by placements, where students spend several weeks on farms and at veterinary clinics in order to gain experience in agriculture and practice. The number of placement weeks varies between courses. Mine entailed 7 weeks of farm placement and 15 weeks of clinic placement.

SECOND YEAR

What does a normal animal look like and how does it work?

Second year covers primarily anatomy and physiology, as well as microbiology, parasitology and biochemistry. My lasting memories of this year involve rote learning the names of every bump on every bone and every detail of every organ in every species, to the extent that I could draw and label the outside and inside of any animal from memory.

THIRD YEAR

What does an abnormal or diseased animal look like and how does it go wrong?

After learning the normal body inside out in second year, this year is spent learning everything that can go wrong with the body - pathology. One of my units was called ‘Systemic Pathology and Medicine’, abbreviated to SPAM, which ruined the the Monty Python sketch (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gxtsa-OvQLA) for me forever. Pathology is accompanied by radiography, pharmacology, nutrition, toxicology, behaviour, welfare, an introduction to One Health, and the basics of surgery and anaesthesia.

In my course, a research project was also launched towards the end of third year, to be conducted throughout fourth and fifth year. This is a requirement of the masters level postgraduate degree (the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, DVM).

FOURTH YEAR

How do I fix an abnormal or diseased animal?

Fourth year is the dreaded year from hell, when students spend more time in the lecture theatre than they do at home. We often brought sleeping bags, pyjamas and kettles to class and basically moved in for the year. Lectures cover surgery, diagnostic imaging, theriogenology (reproduction) and medicine (small animal, production, equine, wildlife and exotics). This is the year when everything from the past four years starts to come together and students begin to feel like real vets.

FIFTH YEAR

Let’s give it a go!

During fifth year, students finally get to close the textbooks, step out of the lecture theatre and put all that new knowledge into action. This is the year you’re allowed all the fun of being a vet, but with just a fraction of the responsibility! It’s also the last chance to try things under supervision before you do it for real out in the big bad world.

The final year of my veterinary course (and most others I’m aware of) primarily consists of rotations. Veterinary medicine covers an enormous range of fields compared to that of human medicine (think of all the human medical specialties and then factor in all the different species vets look after). Rotations are short (one or two week) blocks dedicated to each major field or speciality of the veterinary industry. They are designed to provide students with a foundation in all aspects of the profession. The year group is divided into small groups of around eight students which rotate between 15 different rotations (listed below). These amount to a total of 24 weeks. During these rotations, students form part of the department’s veterinary team and have the opportunity to develop their skills in each area with the guidance of experienced vets. For example, during the two week equine rotation, students may accompany vets on lameness call outs, treat a foal in the hospital, or scrub into and assist with a colic surgery. Whereas, during the two week diagnostic imaging rotation, students may position a surgery patient for stifle radiographs, evaluate an echocardiogram, or radiograph the fetlock of a lame horse.

The other component of final year is streaming. A stream is a broad division of the veterinary industry by species: small animal, production animal, equine, mixed, and wildlife and zoological medicine. Students elect one stream in which to advance their knowledge and skills during final year. This is either the field the student wishes to pursue as a graduate vet, or simply one they have an interest in. A further 12 weeks of placement is undertaken in this field during final year. I selected the wildlife and zoological medicine stream, which allowed me to research platypus in Tasmania, spend two weeks with the vets at my local zoo and participate in wildlife field operations in South Africa.

Primary care

Small animal medicine

Surgery

Anaesthesia

Diagnostic imaging

Ophthalmology, shelter, wildlife and behaviour

Emergency and critical care

Dermatology and dentistry

Equine

Production

Intensive industries

Public health

Anatomical pathology

Clinical pathology

After hours

I hope this post provides a bit of an insight into vet school and what to expect each year. To find out more about each rotation, have a read of my previous posts. As always, if you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to ask.

#vetdownunder#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#anatomy#vetlife#vetmed#veterinary#dvm#veterinarian#medicine#university#study

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

End of an Era

24 weeks of rotations, 15 weeks of placement, 1 postgraduate research project, over 50 assessments, 12 flights and 3 final exams later, I’ve finally reached the end of fifth year! We hit the ground running immediately after our fourth year exams and worked tirelessly right up until Christmas. Although I didn’t have a moment free to appreciate it at the time, fifth year gave me the freedom to explore my interests and presented countless opportunities to travel and work abroad. My experiences have allowed me to grow as a vet - taking charge of cases, making my own decisions and taking responsibility for the outcome. The past 13 months have without a doubt been the highlight of vet school.

#vetstudentdownunder#vetdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#vet#vetmed#vetlife#study#student#graduation#medstudent

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Surgery Rotation

My final rotation of the year! It seems like yesterday that I was following a hand drawn map of the hospital to locate the ophthalmology room for my very first rotation. How far I’ve come!

On this rotation we began with a small group of four students (rather than the usual eight) which was then divided in half, with two students beginning on soft tissue and the other two on orthopaedics. I was assigned to soft tissue surgery for the first week and it was hectic! My buddy and I were run off our feet trying to complete the work of four students. We arrived at 7:30 each morning and didn’t leave until after 7:00 at night when our patient records were completed. Once home, our evenings were spent frantically researching surgical procedures to avoid looking like complete idiots when the specialists inevitably quizzed us the following day.

Students were assigned to cases and responsible for collecting a history during the initial consultation with the owner, performing a physical examination, scrubbing into the surgery, writing a detailed surgical report, looking after the patient in hospital, administering medications, overseeing wound care, recording vitals and the progress of recovery, and eventually discharging the patient. Our ultimate goal was to get our patients through all of those stages and discharged as quickly as possible, to minimise the number of animals in our care and allow us to leave the hospital at a semi-reasonable hour each day.

Although being a group of just two students meant that we had an insane workload to keep on top of, we did get special treatment in the form of being allowed to scrub into almost every surgery! Students in previous groups were lucky to scrub into five surgeries during the whole rotation, whereas I scrubbed into ten just in the first week! Even so, being specialist surgery, our job primarily consisted of passing surgical instruments and cutting suture material (which was never quite the right length). One day towards the end of the first week, the surgeon surprised me by letting me place two sutures: a simple interrupted and a cruciate. That was two more than my fellow student, so I counted myself lucky!

During the first week, I was involved with a huge variety of soft tissue cases (prepare for big words) including an abdominal hernia repair, ventral bulla osteotomy, two dermoid sinus removals, multiple wound repairs, adrenalectomy, thyroidectomy, melanoma removal and skin flap, tongue biopsy, emergency plication to correct an intussusception, gastropexy, and ovariohysterectomy.

The most memorable case from this rotation was a soft tissue sarcoma removal from the hind leg of an elderly Golden Retriever. The surgery was performed on Monday and I arrived early the following day to find her leg very swollen. Over the week, the leg continued to swell and her condition steadily declined. By Thursday her breathing was laboured and I could hardly hear a heart beat. Our patient was transferred to the ICU to spend the night in an oxygen tank. The following morning she was much the same, still struggling for each breath. The vets had tentatively diagnosed her with von Willebrand Disease, an inherited clotting disorder caused by a defective or deficient protein. This meant the swelling in her leg was likely pooled blood as a result of uncontrolled bleeding from the surgical site. The disorder had never been detected previously and so it was an incredibly unfortunate and unforeseen complication. On Friday evening I went to check on her before heading home and reached the ICU just as someone yelled, “SHE’S ARRESTED!”. The emergency team sprung into action and began CPR. Her owners were contacted and the decision was made to let her go. It was a devastating end to what should have been a simple mass removal. Everyone involved was deeply affected by her death.

At the end of the first week, the resident came to see us in the student tutorial room. He told us we had done a fantastic job and he really appreciated our help. The hard work of final year students is often taken for granted, so the few times people have acknowledged and appreciated my efforts have really stuck with me!

Just as we were beginning to feel comfortable with soft tissue surgery, Monday came around and it was time to switch to orthopaedics. New surgeries, new patients, new team. At least I still had my student buddy for support and entertainment. There was an interesting mix of cases on orthopaedics, including bilateral hip dysplasia, intervertebral disc disease, two medial patellar luxations, shoulder arthroscopy, stifle arthroscopy and joint tap, and many tibial plateau levelling osteotomies.

Over the two week rotation, we had several tutorials on wound management, brachycephalic airway syndrome, neurology and fracture management. On the last Friday we had a short exam, followed by an orthopaedic cadaver lab, where we practiced our surgical approaches to the hip and stifle joints, and performed a femoral head ostectomy (a procedure in which the head of the femur is cut off to remove the hip joint).

The last surgery finished late on Friday and the hospital was eerily quiet. It was the strangest feeling saving my final reports, packing up my belongings and preparing to leave the hospital for the last time. The four of us didn’t really know how to react. We congratulated one another on finishing and headed home in stunned disbelief, unsure whether to laugh or cry. We didn’t have much time to process these feelings before our minds became consumed with panicked thoughts of the impending exams. It was time to put our heads down and bums up for one final push to the finish line!

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#vetlife#vetmed#veterinary#vetscience#medicine#student#med#medlife#university#surgery#surgical#rotation#hospital#vetclinic#vethospital#vetstudentlife#veterinarian

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Equine Rotation

I was looking forward to being back in the large animal hospital, in my overalls and boots, with the smell of fresh air, hay and manure wafting through the barn. Out of the group of eight students, only two of us had an interest in working with horses, which meant I’d have more opportunities to practice things over the next two weeks. It became evident early on that the equine department had an innate distrust for students and wouldn’t be allowing us to carry out anything but the simplest tasks under extreme supervision. This sentiment was only reinforced by a recent incident involving a student and a feisty stallion.

After a brief introductory session, a couple of the equine vets conducted a lameness practical with the assistance of two of the teaching horses. We practiced palpating limbs, using hoof testers, and performing flexion tests. After a couple of hours of trotting horses up and down the asphalt outside the barn, both students and horses were knackered.

Also on the first day, we assigned ourselves to each of the hospital cases which would be our responsibility until their discharge. We were to feed, water, medicate, exercise and groom our charges, take and record their vitals each morning and night, write their hospital records, communicate their progress to the responsible vet, perform any procedures required, and present a case summary to the group at morning and evening rounds. My first case was a two year old thoroughbred filly named Sentimental Queen who had a wound over her left elbow (due to a run in with a fence) and a septic joint was suspected. She was a gentle horse and I really enjoyed looking after her and following her case over the week she was hospitalised.

I am the first person to laugh at the ridiculous names given to horses, and for some reason I got it in my head that my horse’s name was instead Independent Sunshine. I made the mistake of sharing that with my fellow students, who then made it their mission to confuse me into calling her Independent Sunshine during rounds by dropping the two words into conversation just prior. I’m pleased to say they didn’t succeed, though there were often long stretches of silence while I tossed up which name was correct in my head.

After a couple of ultrasound scans, and an attempted arthrocentesis and joint flush, we concluded that the wound didn’t in fact communicate with the joint, which made the prognosis considerably more favourable. Each day I brought her into the stocks, cold hosed her leg for 10 minutes to reduce the swelling, re-bandaged her leg, administered her penicillin intramuscularly and phenylbutazone orally, and gave her plenty of love and attention. The swelling over her elbow gradually reduced, as did her temperature, and the wound healed steadily.

It often seemed as though the equine staff were out to get us. They just revelled in any opportunity to scold us for the silliest things. One of the hospital patients developed a case of diarrhoea and I enthusiastically volunteered for the glamorous job of collecting a fresh sample. I gloved up, armed myself with a faecal pot, and stood ready for the next stream. When it came, I extended my arm from where I stood safely at the horse’s side, and filled the pot with the green goodness. At that exact moment, about three voices all yelled at me simultaneously to stay away from the horse’s rear. Err… how can I collect a fresh sample without standing in the vicinity of the horse’s rear?

It wasn’t long before we got to put our new skills from Monday’s practical class to the test with the endless flow of lameness cases that graced the hospital. Solar abscesses, ligament injuries, joint disease… it was one lameness examination after another! The students watched as a nurse trotted the horses up and down in front of us. We scrutinised every movement, wishing so hard to see a head bob or a hip hike that half the time it was imagined. Just when I thought I’d localised the lameness to a single limb, the horse would trot back and I’d pick the opposite limb. The movements were so subtle that I often doubted whether the vet could see it either. Afterwards they would turn to the group of students and say, “you could see that lameness in the the near fore, couldn’t you?”. “Yes” was the answer, whether we could or not!

During the first week, I went on a couple of call outs with a fellow student, a vet and a nurse. At the first property, the owner was really friendly and while the vet was taking radiographs, she showed us around and took us to meet all her horses. When she introduced a gelding as Dark Romance, I struggled to contain a snigger, but she quickly followed with, “I know the name is ridiculous, he came with it”. Finally, someone who understands the joke, I thought. With a straight face, she continued, “I would’ve named him Demi Devine!”. It was too much. I had to turn away to hide my laughter!

Students also took responsibility for outpatients, and a single student was assigned to each case. When my grey warmblood mare arrived at the hospital, I introduced myself to the owner and attempted to gather a detailed history for when the vet arrived. Each of my questions was met with either a single word or a grunt. The man couldn’t have made it plainer that he didn’t want to speak to me. Of course, when the vet arrived, he became Mr Chatterbox and the history changed entirely. Charming.

Towards the end of the first week, the vet responsible for Sentimental Queen (Independent Sunshine) approached as I was hosing her leg and expressed his delight at her progress. He congratulated me on my work and suggested she could be discharged on Friday. It was really gratifying to receive some praise for my efforts - a rare occurrence for a vet student! Friday rolled around and it was a bittersweet moment when she was loaded onto the float and driven home.

For two weeks I had my fingers crossed for a colic case. Please let me have just one more before I graduate! Finally, on the second last day of the rotation, we had an urgent call from an owner whose horse had been collicking since the day before. Supportive treatment from the regular vet had little effect, so she’d opted to bring him to the specialist hospital. A combination of the signalment, history, physical exam and ultrasound findings lead to the decision to perform an exploratory laparotomy. Our patient was anaesthetised and prepped for surgery. The surgeon allowed me, as the primary student, to scrub in and I couldn’t have been more excited. He suggested I wait until he had opened the abdominal cavity and determined the cause in case it was irreparable. Soon after the first incision was made, a horrible rotten smell filled the room and black fluid leaked from the abdomen. The cause was a strangulating lipoma - a small fatty mass which restricts the passage of digesta and the blood supply to the intestines. The built up pressure had resulted in a perforation, explaining the black fluid within the abdomen. The vet identified an 18 foot section of necrotic intestine which would need to be resected if the horse was to have any chance of survival. Even if that went ahead, the prognosis for recovery was grim. The owner opted for euthanasia, which everyone agreed was the kindest option. Instead of scrubbing in, I changed into my overalls, put a rectal palpation glove on each arm, and helped the vet stuff the organs back into the abdomen and suture it closed for disposal. The job was comparable to stuffing a sleeping bag into a too-small sack - far easier said than done!

As usual, the final day of the rotation was reserved for assessments. After our morning computer exam, we all reluctantly moved into the conference room for grand rounds. This involved each student presenting on a topic related to one of our cases during the rotation. I chose septic arthritis as my topic. Public speaking is not my strong point and I was relieved when it was over.

Mid afternoon, one of the vets informed us that a newborn foal was en route to the hospital. The mare had sadly died during birth and the foal had not received sufficient colostrum. We were all super excited for the new arrival. The foal was less than a day old, yet almost equal to me in weight, with limbs to rival a spider monkey, and a whole lot of attitude! It took four of us to restrain him on his side and stop his knobbly legs from flaying everywhere while we did a plasma transfusion. With the new addition to the hospital requiring constant monitoring and frequent bottle feeds, we had our work cut out for us on the weekend shifts!

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#vetlife#vetmed#vet#veterinary#medicine#equine#equinevet#horse#pony#hospital#vethospital#vetstudentlife

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Primary Care Rotation

The primary care (aka general practice) rotation is essentially two weeks in which to become comfortable dealing with the cases that will make up 95% of our workload as vets. This includes vaccinations, ear infections, itchy skin, sore eyes, dental disease, wounds, lameness, and so on. The rotation also focusses on developing our client communication skills through consultations with pet owners.

For the majority of the days we pretended to be real veterinarians. We assigned ourselves to cases which we followed from beginning to end. When our patients arrived, we greeted the owners, collected a detailed history and performed a thorough physical examination of the patient. We reported our findings to the responsible vet and together we formulated a diagnostic and treatment plan. The vet then conveyed this to the client. If any procedures needed to be performed (such as blood collection, ultrasound scan or wound clean), we were allowed to assist. The patient’s hospital report was also our responsibility.

To assess our client communication skills, we had to record our consultations using hidden cameras and microphones (with the client’s permission, of course). Believe me when I say there is nothing more uncomfortable than watching yourself pretending to be a vet. Sooo cringe-worthy! I am awkward at the best of times, but when the camera is rolling, everything seems to go pear shaped. Like when I put my stethoscope in my ears backwards, took it out, looked at it for a moment, and then put it back in the same way. Face palm. I wasn’t the only one with embarrassing footage though. One of my classmates tripped over a dog, another couldn’t hold onto her cat, and someone else had a stubborn dog that planted his butt firmly on the ground and refused to let anyone take his temperature. Between us, we could’ve made a hilarious blooper reel!

In between consultations, the primary care vets organised some informal tutorials on vaccinations, ear and eye medications, and eye examinations. These were really, really helpful.

One day of the rotation was spent “on procedures”. I scrubbed into a digit amputation and lump removal in a dog. I also watched a cystotomy (surgery involving an incision into the urinary bladder) in a dog with a bladder stone. I had another day in the dental clinic where I got to brush up (pun intended) on my scaling and polishing, and watch several extractions. Another day I was stationed at an external vet practice to observe the vets consulting and pick up some tips and tricks from the experts. I also had a day in the exotic pet clinic. I saw some really interesting cases there, including a rabbit respiratory emergency, a python exhibiting neurological signs, and a ridge-tailed monitor that fell from a height and fractured its spine resulting in paralysis of its hind legs.

The final day of the rotation was examination day. We started with an online exam which covered random topics that did not at all reflect what we’d been learning over the fortnight. Straight after that I had a history taking exam. I had to pretend to be a vet and collect a history from the ‘client’ (an actor) while an examiner sat in the corner of the room with a clipboard. I freaked out and forgot everything I knew. There’s a reason I didn’t pursue an acting career! I walked straight out of that exam and into the next. The clinical skills exam should have been easy, but my nerves got the better of me and my hands shook so much that I managed to shatter a glass tube! The final assault was playing my consultation recording in front of a small audience while the examiner critiqued my words, body language and expressions.

At the end of the day, we each had an individual feedback session with one of the primary care vets. When it was my turn, I was feeling a bit like a lamb for slaughter, but my skin was thick and I was ready for the next wave of criticism. Lay it on me! I was completely taken aback when I was instead flooded with praise and encouraging words.

I really appreciated the kindness, patience and support from the primary care staff. It makes all the difference at this point in the year (and degree).

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#primarycare#generalpractice#gp#medicine#veterinary#veterinarian#vetlife#vet

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anaesthesia Rotation

(1001 Ways To Kill Your Patient)

While most people in my group were terrified to begin two weeks of anaesthesia, having spent six years working in a vet clinic on weekends and often playing anaesthetist, I felt quietly confident about this rotation. I was already competent drawing up and administering medications that a vet had advised, recognising when a patient’s vitals were abnormal and following instructions to correct this. I was hoping this rotation would provide me with an explanation behind these actions so I would be able to problem solve and make decisions independently.

In the introductory session, we were led to believe that we would be the primary anaesthetists, and a supervising vet would be around and ready to jump in if things went pear shaped. It quickly became evident, however, that the vets and nurses didn’t have the tolerance or patience for teaching. They simply couldn’t resist interfering. A perfect example of this was placing catheters. You’d think that getting the catheter into the vein would be the hardest part, right? Wrong. It’s all in the taping my friends. You would also think, perhaps, that as long as the tape secures the catheter and ensures it remains in the vein for the duration of the procedure, it was serving its purpose. Also wrong. In the university hospital, there are about 10 types of tape that all need to be applied in a certain order and in a very specific way. The catch: every single department and staff member does this slightly differently. The student’s job is to ascertain the ‘correct’ technique for the specific supervisor and carry it out without the slightest hesitation. Knowing this to be the bane of many a student’s existence, after placing my first catheter of the rotation, I asked the supervising vet if they had a preference for taping. She replied, to my astonishment, “No! As long as the catheter stays in, you can tape any way you like!”. I proceeded to secure the first piece of tape, when suddenly - “NO! Not like that! I like to do it this way because…”. And just like that, I was robbed of my taping responsibilities and forced to endure yet another 10 minute lecture on how to best tape in a catheter. It was micromanaging in the most extreme sense. A few days on, my friend joked that if she heard one more person say “let me just show you a trick with taping”, she might throttle someone. Except I’m not entirely sure it was a joke. We were all incredibly frustrated. That level of control was applied to every aspect of anaesthesia throughout the rotation. I don’t know how we were expected to learn from our mistakes and correct them.

One time I offered to clip a dog’s nails and after a good five minutes of convincing the nurse that I was, in fact, capable of performing such a hazardous task, she eventually relinquished the clippers. She returned a while later to ask whether I’d made any bleed (no), if I was sure (yes), if I’d clipped them short enough (yes), whether I remembered to also cut the back nails (yes) and whether I also clipped the dew claws (yes). She then inspected them all herself before saying “not a bad effort” and walking off. NOT A BAD EFFORT!? Just about the time I’d recovered from that incident, she returned to give me a 15 minute lecture about how to appropriately assemble an e-collar. Sigh.

Micromanaging aside, the staff were more than happy to explain things and answer questions, so I focussed my two weeks on learning the theory, rather than improving my practical skills. We were encouraged to create an anaesthesia plan specific to each of our patients, including drug choice and dose rate for premedication, induction, maintenance and analgesia, a fluid rate, and specific anaesthetic considerations. This was a really useful exercise, even though the clinicians always used their own plan regardless. We also had an assignment for which we had to come up with a pain management plan for two provided cases, one acute and one chronic. My acute case was a horse undergoing colic surgery and my chronic case was a dog with hip osteoarthritis. I didn’t realise just how complicated pain management could be until I started researching drug efficacy, dose rates, interactions and adverse effects.

As the days passed and we learned more and more about patient physiology, anaesthetic machines, the drugs at our disposal and their endless side effects, it became evident that anaesthesia could be renamed ‘1001 ways to kill your patient’. Strangely enough, incorrect catheter taping technique is not one of them!

The hospital anaesthetic machines and monitors were next level. The most extreme of which I was told is “the only one in the country”. The 10 screens were filled with all sorts of unnecessary numbers, graphs and settings, all beeping and flashing to indicate one thing or another. It’s a good thing the patients were stable, because by the time I found the heart rate and determined it to be dangerously low, the patient could already be dead! I’m exaggerating, of course, but I still found it absurd. Despite being the fanciest anaesthetic monitoring machine in Australia, it seemed to struggle with a basic heart rate and blood pressure reading. Oh the irony! Give me a stethoscope, thermometer and watch any day!

One of the perks of the anaesthesia rotation was that I got to follow my patients all over the hospital and visit friends in primary care, imaging, medicine and surgery. I also got to see some pretty interesting procedures including orthopaedic surgery, CTs, rhinoscopy, surgery to remove an enormous abdominal mass from a tiny dog (the mass was 20% of the dog’s body weight), ectopic cilia removal, a cat that was bleeding into its abdomen, two pig speys, and a horse that was having a fetlock arthroscopy.

On the final Friday we had a theory exam and three practical exams. The first practical exam involved setting up an anaesthetic machine for a specified patient, leak testing it and fixing a leak. Mine had a hole in the reservoir bag. The second was intubation, which was easy. The third was dose calculations, which I had no problem doing at home, but the exact moment my timer started in the exam, a loud BANG-BANG-BANG started across the room. All I could think was how loud the banging noise was and how fast the timer was ticking down. I managed to get to an answer but I’m not sure if it was right. I’ve added a practice question below, for your enjoyment.

Although I’m now confident with the basics required in every day private practice, I feel as though I’ve only just scratched the surface of anaesthesia. I have my whole career ahead of me to keep learning!

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#vetmed#veterinary#dvm#medicine#anaesthesia#anaesthetic#veterinarian

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Diagnostic Imaging Rotation

I had been dreading this rotation all year and it was finally upon me. Countless stories of students crying and having breakdowns were circulating and didn’t inspire a great deal of enthusiasm. The first couple of days were really quite overwhelming. It seemed as though there was a new assessment every five minutes!

Each day generally began with an online quiz for which we frantically revised the night before. Once finished, we would convene in front of the light boxes for interpretation rounds. This involved five students being selected at random to look at a series of radiographs we’d never seen before, interpret them using a systematic approach, and arrive at a diagnosis. This was both timed and assessed. Each day would cover a different topic: musculoskeletal, thorax, abdomen, equine, and so on. In a desperate attempt to beat the tears, our group diffused the tension with humour. I don’t remember how it started, but we began referring to interpretation rounds as ‘the grilling’ or ‘the roasting’. The puns were endless. When asked if we were ready, the response was “I’ve been marinating all night!”. As the first person of the day stepped up to the hot seat, someone would mime lighting a grill. If the radiologist was being especially harsh, we’d say “the grill is hot today!”, and if they were giving someone a hard time, someone would make a sizzling noise in the background. Laughter was the only way to get through it.

On the first day, we had a short ultrasonography tutorial and a quick practice scanning a nurse’s dog. Each student was assigned a day of ultrasonography during which we observed the specialist performing scans and pretended to understand the grey shapes on the screen. Another day was spent on ‘interpretations’ where we interpreted all of the radiographs taken that day. The remaining students were assigned to radiography, which involved positioning real patients and taking the radiographs according to requests from clinicians. These were also timed and assessed, with many ways to instantly fail. If there weren’t any real patients, we were assessed on the dummy dog (named Emily) who was frustratingly inflexible. In the evenings, we would convene again for rounds and share any interesting cases with the group.

Towards the end of the second week, we had yet another timed exam where we had to take radiographs of a horse’s foot, fetlock or carpus. I forgot to check the exposure parameters on one of my shots, but it happened to be on the right setting by coincidence. On the final morning, we had an online theory exam.

As much as it pains me to admit it, I think I actually enjoyed diagnostic imaging! It was great to finally learn how to read radiographs and I improved considerably over the two weeks. Not a single tear was shed in our group, which was perhaps our greatest achievement.

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#vetmed#dvm#imaging#veterinary#diagnosticimaging#radiography#radiology#medicine#medstudent#vetstudentlife

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Note On Religious Slaughter

In my third year of vet school, I had to write an essay on an animal welfare issue. I chose to research ‘halal slaughter’ because I wanted to increase my knowledge in order to form an educated opinion. The essay ended up winning me an award and sponsorship from Meat and Livestock Australia. It also provoked an ongoing interest in animal welfare associated with slaughter and euthanasia.

Halal slaughter conditions vary considerably according to differing interpretations of the Quran. It is generally accepted that animals must die from exsanguination (draining of blood) in order to be classified as ‘halal’. Therefore, animals are either slaughtered without any prior stunning (i.e. conscious) or after being reversibly stunned.

Conscious animals are capable of feeling pain, fear and stress. For this reason, livestock should be rendered unconscious before they are killed by ventral neck incision. In Australia, most abattoirs stun animals prior to slaughter. This can be done via a number of methods, including gas, electric stunners and non-penetrative captive bolt (NPCB). The issue with these reversible stunning methods is that animals can regain consciousness prior to death. They therefore rely on worker efficiency to ensure throats are cut and animals are effectively bled out before the effects of stunning wear off. In addition, there are few reliable methods of determining whether animals are, in fact, dead before they can regain consciousness. Any movement is often just attributed to post-mortem muscle twitching - but who’s to say it’s not conscious movement?

A small percentage of Australian abattoirs have been exempted from stunning standards and permitted to slaughter conscious animals for religious purposes. This is just disturbing.

The alternative (non-halal) slaughter method involves prior stunning by penetrative captive bolt (PCB) which results in irreversible unconsciousness. This method eliminates the risk of an animal regaining consciousness after having its neck cut, and therefore eliminates any pain, fear and stress post-stunning.

I fully appreciate that some swift knife action and rapid bleeding may once have been the most effective and humane method of slaughter. However, new large scale production industries and an increasing demand for meat from a rapidly growing population necessitate change. In modern times we have new knowledge and new technology that allows us to more humanely kill our livestock. Is it not our moral responsibility to utilise the best and kindest methods at our disposal?

I respect the religions of others, but I simply cannot justify animal suffering for a human belief. The more I research halal slaughter, the more uncomfortable I become with it. Don’t take my word for it though - do your own research and reach your own conclusions! The facts are out there if you do a bit of digging!

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetmed#vetschool#vet#veterinary#veterinarian#vetlife#abattoir#meat#slaughter#animalwelfare#animalethics#meatlover#vegetarian#food

153 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Public Health Rotation

The rotation that converts the masses to vegetarianism! This is a week spent in lab coats, hard hats and gumboots, visiting a range of local abattoirs (chicken, sheep, cow and pig) and learning about public health issues. The following account describes my observations in detail and doesn’t skirt around difficult and controversial issues. If you do not want to know about animal slaughter, stop reading now and find another blog that talks about happy things like puppies and kittens! However, I encourage you to educate yourselves about where your meat comes from so that you can make informed lifestyle decisions. After all, eating animals is a privilege, not a right!

On Monday we were re-introduced to the concept of ‘One Health’ (a multidisciplinary approach to health issues at the human, animal and environmental interface), revised zoonotic diseases (those transmitted naturally between humans and vertebrate animals), and learnt about food safety.

The following day we kicked off the abattoir visits with a tour of a chicken factory. The disposable onesies we were given for hygiene purposes made us look like giant white chickens ourselves. It was a dangerous situation for chicken-lookalikes to be in! Our guide was way too enthusiastic for a slaughter house and seemed to be operating under the illusion that he was instead working at a fun fair. We walked through a set of doors to reveal the most bizarre scene I think I’ve ever seen. Everywhere I looked, there were plucked chickens gliding along on tracks, hanging by their legs, at various stages of disassembly. I was half expecting circus music to start playing in the background. Despite the horror of the situation, I actually struggled not to laugh at the absurdity of it all. After showing us around the meat processing areas, our guide took us to see the slaughter. Groups of chickens were contained in crates, which were passed individually through a gas chamber. The chickens were gassed with CO2 and exited the chamber unconscious. Workers then hung them by their feet, and they moved along the line past a blade which cut their necks, causing them to bleed out. Just before their necks are cut, a muslim man standing with a hand outstretched, touched each chicken as they went by, apparently saying a prayer for them (not that it did any good). This ensures the final product is ‘halal’ certified.

On Wednesday, we all piled into the university vehicles for a long drive down south. Our first stop was a sheep abattoir. This one was quite crowded and we had to jump between moving carcasses, hop over piles of congealed blood, and dodge swinging knives. This abattoir also produces ‘halal certified’ products. The sheep were stunned with an electric stunner before having their necks cut by a muslim man. Workers are supposed to check the corneal reflex prior to cutting the neck, and re-stun if there is a blink response. In the five minutes I spent watching this process, I didn’t once observe anyone checking the corneal reflex, and I am confident that one sheep was not effectively stunned before having its neck cut. This sheep continued to kick and struggle until it eventually bled out. I found this deeply unsettling.

After a quick lunch break at the nearby farmer’s market (I can assure you there was no meat in my sandwich!), we headed to our next stop - a beef abattoir. I had already visited this abattoir in my second year of vet school, so I was prepared for the horrors ahead. Although the sheer size of the animals made it more confronting than the other abattoirs, I was generally impressed with the efficiency and welfare standards. This abattoir also produces ‘halal’ products. The cows are stunned with a non-penetrative captive bolt (NPCB) and their corneal reflexes are checked to ensure they are unconscious. A muslim man performs two cuts: the first is a religious cut across the neck and the second severs the major thoracic vessels causing faster bleeding. The corneal reflex check and second thoracic cut make this method more foolproof than that used at the sheep abattoir. I was surprised by the number of late-term foetuses I saw going around the conveyor belts with the other organs. According to the OPV (on plant vet), these foetuses die from anoxia (lack of oxygen) over about a ten minute period. This didn’t sit well with me. Apparently there is no law against slaughtering pregnant animals, but pregnant animals are not ‘fit to load’ (legally allowed to be transported) during late gestation. This, however, does not appear to be enforced. The OPV explained that the abattoir makes a lot of money from foetal products (such as foetal blood drained from the heart), so there is no incentive to prevent this practice.

It was an emotionally draining day and I decided I had earned some comfort food. I stopped at the grocery store on my way home to buy some chocolate. Just as I got there, I watched a dog run across the road and get hit by a car. I sprinted over and was the first on the scene. The dog was bleeding profusely, an eye was hanging out, and the the owner was screaming and panicking. I tried to assess the dog and take control of the situation. The dog rapidly turned white and I couldn’t feel a heart beat or pulse. It was a quick death, most likely caused by a splenic rupture and huge internal bleed. I left the owners to grieve and managed to hold the tears back until I got home. It was just a bit too much death for one day!

On Thursday, we wrapped up the grand abattoir tour with a visit to a pig abattoir. They were reluctant to show us much, which of course made us assume the worst. However, we did get to see some of the carcass processing post-slaughter. It was a different kind of weird, perhaps because their pink hairless bodies look oddly human-like. The carcasses were hung by the hind legs and moved slowly around a track through all the processing stages. They got dunked in a trough of water, causing it to slosh over the sides periodically, then set alight by a jet of flames which singed off hairs and cleaned the skin, before being disembowelled. Although we didn’t see the slaughter, the method was described to us. Small groups of pigs are gassed in a CO2 chamber which renders them unconscious. Their necks are then cut individually. Larger pigs are stunned with an electric stunner followed by a captive bolt, prior to having their necks cut. Pig products, of course, are not halal, so there were no religious slaughter methods used.

Back at uni, we conducted a quick food hygiene experiment. We inoculated a slab of meat with bacteria and made cuts with a knife to mimic the work of abattoir employees. We then dunked the knife in two different water temperatures and compared the bacterial load between them. The higher water temperature resulted in a significantly reduced bacterial load. This technique of dunking knives in hot water between cuts is utilised in abattoirs to reduce food contamination.

On the final day of the rotation, we did our group presentations on zoonotic diseases. My group was assigned Ebola virus. I found this topic fascinating and really enjoyed researching the disease. During the presentation, I stumbled on a word and got the giggles. I couldn’t stop laughing and every time I managed to gain control of myself, I would see one of my friends shaking with laughter and it would set me off again! Sorry team! After the presentations, we sat a short end-of-rotation exam, which was very reasonable. Much to our delight, we finished early and got the afternoon off!

All in all, I thought this rotation was a confronting but very necessary experience. I think welfare issues regarding slaughter need to be tackled head on. Turning a blind eye is the convenient option, but it doesn’t mean that animals aren’t suffering. Most people today are so far removed from the slaughter process that it’s easy to forget that meat comes from animals rather than the supermarket, and take their lives for granted. I strongly believe that anyone who eats meat should be made aware of the slaughtering process, and ideally witness it. If you can’t stomach the animal slaughter, you shouldn’t stomach the meat!

Have a read of my next post about religious slaughter.

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetmed#vet#vetschool#vetlife#vetstudentlife#veterinary#veterinarian#publichealth#onehealth#onplantvet#foodsafety#foodhygiene#zoonosis#zoonoses#abattoir#vegetarian#vegetarians#meatlover#meateater#meat#animals#animalwelfare#animalethics#halal#slaughter

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DPIRD Workshop

Last week I voluntarily attended a two day workshop at the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (aka the agricultural department). Unfortunately for me, the scheduled days alternated with my rostered night shifts at the equine hospital, meaning, aside from the odd power nap, I was awake from 9am on Monday to 9pm on Wednesday! That’s 60 hours of sleep deprivation that I brought on myself!

Despite having to physically hold my eyelids apart (because no amount of caffeine can substitute two nights of sleep), the workshop was well worth it. Only five students attended, so the training was interactive and hands on. Field vets, pathologists and other specialists contributed to the course, each imparting a wealth of knowledge and advice. A wide range of topics were covered over the two days, including:

What to expect on our first farm visit

Necropsies and sampling

Disease surveillance and reportable diseases

Foot and mouth disease (FMD)

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE)

Avian necropsies and diseases

Utilising the significant disease investigation (SDI) subsidy scheme

Welfare

Nutrition

We also had the opportunity to perform an entire sheep and chicken necropsy, including sample collection, independently. Necropsies are covered quite superficially by the vet course, and I previously had a limited understanding of the procedure. It was the first time I’d completed one by myself, and it was really helpful to receive direct feedback and advice from the experts. I also practiced removing the brain of the sheep with a hatchet and mallet (not to be confused with ‘mullet’). A field necropsy is something I could potentially be asked to do on my first day as a vet, so it’s great that I now have the confidence to ‘take the bull by the horns’, so to speak.

I found both days really interesting and beneficial to my first year out in the field! Everyone at the department was friendly and great to work with. It was clear that they were really invested in our education and more than willing to lend a hand or offer advice when needed.

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#vetlife#pathology#necropsy#postmortem#dvm#agriculture#farmvet#veterinarian#veterinary

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

After Hours Rotation

Throughout the year, final year students have to complete two weeks of ‘after hours’, comprising a total of three nights at the small animal emergency centre and three nights at the equine hospital. The small animal emergency nights are actual shifts where we are expected to work through the night, consulting, looking after the ICU patients, and treating emergency cases as they arrive. The 10pm to 8am shift is an absolute killer! Copious amounts of caffeine and sugar are a necessity to remain functional throughout the night. The only good thing about these shifts is that we’re allowed to wear scrubs, which are essentially professional pyjamas. There is a magical time around 3am where things usually become quiet (touch wood) and everyone starts to get a little delirious and giggly. This is when the staff let their guard down and students become privy to the hospital goss. All of my overnight shifts were dead quiet (maybe that’s not the best term to use in this situation) which made the nights drag out painfully. The worst part was leaving the hospital in the morning, blinded by the light and feeling like a zombie, while your friends rolled in, fresh-faced and full of enthusiasm for the day ahead.

Equine overnight shifts, by comparison, are usually a lot more manageable. Two students are rostered on each night and given access to the student flats (a small room with a mattress, study desk, basic kitchen facilities and attached bathroom). At 5pm, we meet at the equine barn for rounds where we take notes on the hospital patients and form a plan for the night. Usually the overnight students have treatments and colic checks at 6pm, 8pm, 12pm, 4am and 8am. In between these times, we can study or attempt to sleep. The student flats are filled with textbooks, which I guess is a not-so-subtle hint from the university! We are also on call and have to answer the phone if it rings. Thankfully, all of my equine cases were straightforward and the phone didn’t ring once. There were, however, five lambs in the production barn which needed regular bottle feeds. They were very cute, but it meant I didn’t get much sleep at all. At 8am, we drag ourselves down to the equine barn to meet the well-rested day students for rounds and pass on any pertinent information from the night.

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetmed#veterinary#vetlife#vetschool#equinevet#emergencyvet#medicine#studentlife#veterinarian

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DVM Research Project and Conference

After two long years, I finally hit SUBMIT and waved goodbye to my research project for good. This study has caused me an unbelievable amount of stress and frustration, and probably accounted for 95% of my vet school problems. A whole lot of sweat and tears went into it (blood was provided by other aspects of vet school), leaving me as dehydrated as a cat with chronic kidney disease. It feels like the huge dark cloud hanging over me has finally lifted. Hallelujah!

A couple of weeks ago, my year group attended the first ever Murdoch University DVM Research Conference, where we presented our findings to our peers, supervisors and external practitioners. My fellow bobtail lizard researchers (the “Bobsquad”) nailed the presentations, and I think it’s fair to say we brought SHINGLE BACK! It was an interesting day, made even better by the free food and drinks! It was also the first time our whole year group had been together since last year, so it was great to catch up with everyone and hear about their experiences in practice.

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#dvm#masters#research#university#phd#study#student#vetlife#vetmed#bobtails#lizards#reptiles#herpetology

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Anatomical Pathology Rotation

I had low expectations for this rotation, after a friend described it as, “anatomical pathology…more like anatomical crapology”. Despite the negative review, I was determined to keep an open mind and start the week with fresh enthusiasm for dead things!

Monday began with a bit of pathology revision and a few practice cases. It was really hard and I felt as though I may as well have been listening to another language (situation not helped by the strong French accent of our teacher). In the afternoon, we got out the aprons, boots and safety glasses, and worked in groups to perform a couple of necropsies (the word for post-mortem examination in non-human animals). I worked on a five month old mixed breed dog that had presented to the hospital in acute respiratory distress. We systematically worked our way through all the anatomical structures, recording our findings as we went. While my teammates worked on other parts of the body, I removed the “pluck” - a weird term for a group of structures that can be removed together by cutting out the tongue and dissecting away attachments along the trachea and oesophagus to the heart and lungs. It is every bit as gruesome as it sounds! Pneumonia was evident in the lungs and the lung tissue was so dense it sunk when placed in water. I cut down the length of the trachea and discovered, to my surprise, the cause of death! A chunk of cartilage was wedged into the right primary bronchus, and had cut full thickness through the trachea. For one very brief moment I considered a career as a pathologist. I then looked around at all the death and gore surrounding me and quickly came to my senses. My friend, who was working on the gastrointestinal tract, found a huge number of nematodes (parasitic roundworms) in the intestines, which made my skin crawl!

On Tuesday we began the day with some more theory, and then headed to the post-mortem room in the afternoon for some more dead animals. A horse, a dolphin and a cat needed to be necropsied (no, this is not the start of a bad joke), and somehow I managed to get landed with the cat. Boo! It was a pretty straightforward case of chronic kidney disease, which meant I had time to hang around the dolphin and have a bit of a nosy. The dolphin, who was known to have a young calf, had died as a result of fishing line entanglement. The line had cut into her dorsal fin and tail fluke, restricting her movements and leaving open wounds susceptible to infection. It was a sad case and a reminder of the damage caused by human waste.

On Wednesday morning we went to the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (aka the agricultural department). We were given a tour of the facility, had a couple of lectures on necropsy sampling and notifiable diseases, and participated in a quick parasitology workshop. We headed back to uni in the afternoon for a cow necropsy. Large animal necropsies are quite a task, and it’s easy to become so focussed on what you’re doing that you don’t notice the absurdity of squatting in the middle of a cow carcass, soaked in blood, surrounded by organs and wielding a huge knife!

Thursday began with some more practice cases. Our teacher broke the news to us that necrosis is in fact white, rather than black as we had all previously been led to believe. Mind blown! In the afternoon we went to the university fish health unit where we anaesthetised fish and practiced taking gill samples and skin scrapes. We then euthanised the fish with an anaesthesia overdose, followed by cutting the gill arches and severing the spinal cord, just to be sure. Once dead, we performed a necropsy and collected samples for a research project. The tiny heart continued to beat for many minutes after being removed from the body. Creepy-deepy!

The final day of the rotation involved assessed pathology rounds and an online case-based exam. For rounds we had to present a specimen collected during the week to our peers and a small audience of vets from the teaching hospital. I presented the trachea and lungs from the case on Monday. I was really nervous but it actually went much better than I expected. I even survived the brutal questioning from the pathologists and got complimented on my explanation of the pathophysiology of pneumonia! The exam, on the other hand, was straight out of hell. The questions were so random and specific - there was no way we could’ve known the answers! Luckily we we were all in the same boat. All in all, anatomical pathology is a great rotation for those who enjoy feeling like an idiot constantly. Although I do enjoy the odd necropsy, I think it’s fair to say a career in pathology is not for me!

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#vetschool#vetmed#veterinary#veterinarian#vetlife#dvm#pathology#necropsy#postmortem#death#path#anatomy

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Have You Got a Job Lined Up Yet?

Fresh off the plane from Sri Lanka, I had a mere three nights in my own bed before re-packing my bags and setting off on yet another veterinary expedition. This time I’d be driving several hours south for two weeks of clinical placement at my favourite country practice. I spent my first ever week of placement at this clinic, and during the drive down it dawned on me that this would be my last! Two more weeks of being ‘the student’. Next time I find myself in a clinic, I’ll have the title and responsibility of ‘veterinarian’!

It was nice to see some familiar faces when I arrived and catch up on some of the country gossip - most of which revolved around sightings of a panther that had escaped from a circus over 70 years ago, and a thylacine (an extinct carnivorous marsupial) *eye roll*. I stayed with a couple of the vets, both of whom I really admire and look up to as mentors, on their new farm just out of town.

The first week was pretty eventful and I saw my fair share of interesting cases and procedures, including a steer with a corneal ulcer, several non-healing wounds, a dog with an acute hepatic injury, two ram castrations, a horse dental float, a cat with pericardial effusion, a lame bull, a sheep with lambing paralysis, lymphoma in a dog, a recumbent horse, and a cow that had retained foetal membranes, metritis, mastitis and pneumonia.

One of the vets introduced me to the clients by saying, “this is Steph - she’s an almost-vet”. Every single person I met during the first week asked me if I have a job lined up at the end of the year. I hadn’t even started looking! I wasn’t at all concerned until now! The vets also started testing my knowledge by saying, “you’re going to be a vet in a few months - how would you treat this case?”. Generally I was pretty wrong, but at least I know the answers now… and I still have five months to learn everything!

The vets I was staying with killed one of their sheep and I spent an evening helping them cut up the carcass. It was quite an experience and oddly relaxing! Their four year old son gave us all an anatomy lesson as we worked. Once every last scrap of meat had been scraped off the bones, we chucked some on the barbecue and had lamb chops for dinner. The real country experience!

One morning during my second week, I had the choice of getting a lift with one of the vets who had a gelding to do, or driving to the clinic myself to help another vet with a lame bull. After much deliberation (and being acutely aware that whichever I chose would be the wrong choice), I decided on the bull. After listening to the first vet’s car engine fade into the distance, I hopped in my own car and turned the key. It wouldn’t start. Brilliant. I just sat there for a second, mentally kicking myself. Typical! Most of my day was spent getting lifts from other people, on the phone to mechanics, and organising the car to be towed into town. I ended up missing out on going to see the bull anyway, and the other vet rubbed salt in the wound by telling me he had an exciting day involving a foetotomy, prolapsed uterus in a cow, and two equine geldings!

In between frequent trips to the auto shop, I observed and assisted with some interesting procedures during my second week. There was a ferret dental, entropion corrective surgery, a grid keratotomy and third eyelid flap on a dog with corneal ulceration, another equine dental, a couple of colic cases, and a dog with sudden onset blindness in both eyes. The vets let me do a few sterilisation surgeries as well, and I impressed them with my intradermal suturing skills acquired from my recent placement in India. I also got to extract a canine from a cat (the tooth variety, not the barking type).

Towards the end of the second week, the practice owner tracked me down and interrogated me about my interests and plans for next year. It was obviously an interview and everyone in the clinic went quiet to listen in. I was really put on the spot! She explained they had plans to hire a new graduate vet next year and then invited me to dinner the following night. Once she left the room, everyone said, “oooh, she’s sussing you out Steph!”. I was admittedly a little terrified about the invitation, but it was actually very casual and enjoyable. As soon as I arrived, I was put to work drenching their newly acquired sheep. I suspect that was a subtle test as well! We had pork chops for dinner (again, meat from their own pigs). The following day, I accidentally walked in on a discussion between the practice owner and some of the staff about potential candidates for the vet position. I didn’t hear a lot, but I guess time will tell.

Despite my misfortunes, I really enjoyed my final two weeks of placement and learnt a whole lot. Although I’m terrified of graduating and stepping out into the big wide world, I’m also really excited about becoming a vet in just a few short months. It’s time to dust off the old CV and start hunting down some referees!

#vetstudentdownunder#vetstudent#veterinary#vetlife#veterinarian#vetstudentlife#vetschool#vetmed#dvm#seeingpractice#countryvet#ruralvet#mixedvet

13 notes

·

View notes