#yehoram

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Yehoram Gaon

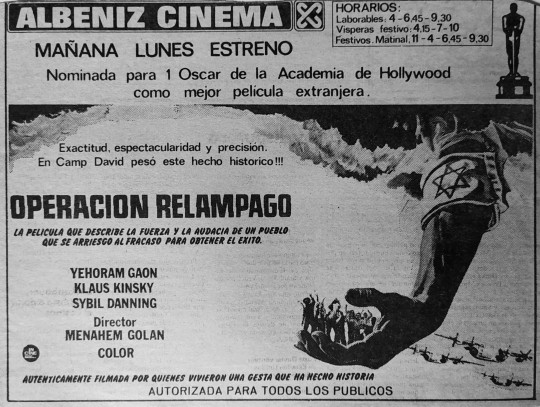

🇺🇸 Yehoram Gaon, born December 28, 1939, is an Israeli singer, actor, director, and media personality from a Sephardic family. He began his career in the Nahal entertainment troupe during his army service and gained fame with the musical "Kazablan." Gaon has produced nearly fifty albums, including Ladino music, and performed extensively. He starred in notable films like "Operation Thunderbolt" and entered politics in 1993, serving on the Jerusalem City Council. In 2005, he was voted the 27th-greatest Israeli of all time. His 1974 album "Romantic Ballads from the Great Judeo-Espagnol Heritage" introduced Ladino songs to Israeli audiences.

🇮🇱 Yehoram Gaon, nasido el 28 de dekiembre de 1939, es un kantador, aktor, direktor i personalidad de medya de Israel, de una familia sefardí. Empesó su karyera en la trupa de entretenimyento de Nahal durante su servisyo militar i ganó fama kon el mizikal "Kazablan." Gaon produjo serka de sinkuenta alvumos, inkluyendo muzika ladina, i aktuó extensivamente. Protagonizó filmes notables komo "Operacion Thunderbolt" i entró en politiká en 1993, sirviendo en el Konsejo de la Ciudad de Yerushalayim. En 2005, fue votado el 27-mo israeli mas grande de todos los tiempos. Su alvumo de 1974 "Baladas Romantikas del Gran Eredado Judeoespañol" introduzó kantikas ladinas a las audiencias israelís.

#judaísmo#judaism#israel#jumblr#ladino#sephardic jews#sephardic traditions#sephadic music#música sefardí#jewish#🇮🇱#israelí#cantante#kantes#kantes sefardíes#sephardim#יהורם גאון#yehoram gaon#gaon#yehoram#judío#sefardíes#sephardic#sephardi jewish#música

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jerusalem - this is a love song

A love so great that a “thousand incarnations” could not make us forget or seek out a new love

As an American born Jew, I had little connection with Israel and even less understanding… although my mother was born in Israel, although my grandmother was a freedom fighter who dedicated much of her young life to the re-establishment of the Jewish State. In the diaspora it was Yehoram Gaon’s voice that gave me some connection to Israel. I AM HERE was written in 1971 for Yehoram Gaon, in…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

You're the Jewish music בקי here on jumblr, yeah? Do you think the lyric "כבר שרנו לך באמונה שלא תהיה עוד מלחמה" in Shwekey's שיר היונה is referring to Yehoram Gaon's המלחמה האחרונה?

Okay, not that I have a problem with mixing Hebrew and English, but this is absurd, what are you saying??

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

list of things that happened at my middle of nowhere Purim party

a) a relative of one of the zaydes asked me to dance with him because it was His Song. His song was Uptown Funk and he did know the words

b) the dj announced we would be hearing top Israeli dance hits. I got ready for Omer Adam. The hits ended being עוד לא אהבתי די as sung by Yehoram Gaon as that was the organizers idea of a recent Israeli dance hit

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jehoshaphat Reigns in Judah

1 And Yehoshaphat his son reigned in his place, and strengthened himself against Yisra’ĕl,

2 and placed an army in all the walled cities of Yehuḏah, and set watch-posts in the land of Yehuḏah and in the cities of Ephrayim which Asa his father had taken.

3 And יהוה was with Yehoshaphat, for he walked in the former ways of his father Dawiḏ, and did not seek the Ba‛als,

4 but sought the Elohim of his father, and walked in His commands and not according to the deeds of Yisra’ĕl.

5 So יהוה established the reign in his hand. And all Yehuḏah gave presents to Yehoshaphat, and he had great riches and esteem.

6 And his heart was exalted in the ways of יהוה, and he again removed the high places and the Ashĕrim from Yehuḏah.

7 And in the third year of his reign he sent his leaders, Ben-Ḥayil, and Oḇaḏyah, and Zeḵaryah, and Nethanĕ’l, and Miḵayahu, to teach in the cities of Yehuḏah.

8 And with them he sent Lĕwites: Shemayahu, and Nethanyahu, and Zeḇaḏyahu, and Asah’ĕl, and Shemiramoth, and Yehonathan, and Aḏoniyahu, and Toḇiyahu, and Toḇaḏoniyah, the Lĕwites, and with them Elishama and Yehoram, the priests.

9 And they taught in Yehuḏah, and with them was the Book of the Torah of יהוה. And they went around into all the cities of Yehuḏah and taught the people.

10 And the fear of יהוה fell on all the reigns of the lands that were around Yehuḏah, and they did not fight against Yehoshaphat.

11 And some of the Philistines brought Yehoshaphat gifts and a load of silver. And the Araḇians brought him flocks, seven thousand seven hundred rams and seven thousand seven hundred male goats.

12 And Yehoshaphat became increasingly great, and he built palaces and storage cities in Yehuḏah.

13 And he had much work in the cities of Yehuḏah. And the men of battle, mighty brave men, were in Yerushalayim.

14 And these were their numbers, according to their fathers’ houses: Of Yehuḏah, the commanders of thousands: Aḏnah the commander, and with him three hundred thousand mighty brave men;

15 and next to him was Yehoḥanan the commander, and with him two hundred and eighty thousand;

16 and next to him was Amasyah son of Ziḵri, who volunteered himself to יהוה, and with him two hundred thousand mighty brave men.

17 And of Binyamin: Elyaḏa, a mighty brave one, and with him two hundred thousand men armed with bow and shield;

18 and next to him was Yehozaḇaḏ, and with him one hundred and eighty thousand prepared for battle.

19 These were the ones serving the sovereign, besides those whom the sovereign put in the walled cities throughout all Yehuḏah. — 2 Chronicles 17 | The Scriptures (ISR 1998) The Scriptures 1998 Copyright © 1998 Institute for Scripture Research. All Rights reserved. Cross References: Exodus 1:11; Exodus 34:13; Numbers 1:8; Numbers 1:36; Deuteronomy 6:4; Judges 5:2; Judges 5:9; 1 Samuel 10:27; 1 Kings 12:28; 1 Kings 15:24; 1 Kings 22:43; 2 Chronicles 11:5; 2 Chronicles 14:14; 2 Chronicles 15:3; 2 Chronicles 15:8; 2 Chronicles 15:17; 2 Chronicles 18:1; 2 Chronicles 19:8; 2 Chronicles 21:12; 2 Chronicles 22:9; 2 Chronicles 26:8; 2 Chronicles 35:3; Proverbs 16:7; Isaiah 13:20

#Judah flourishes#Jehoshaphat#idols removed#worship#God#Levites teach the people of Judah#the people's hearts turn to God#2 Chronicles 17#Book of Second Chronicles#Old Testament#ISR 1998#Holy Bible#The Scriptures 1998#Institute for Scripture Research

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 125: II Kings 3 // 'מלכים ב' ג

A fun bit of human sacrifice in today's chapter.

(Link to full chapter text on Sefaria)

0 notes

Text

3/5 おはようございます。 Peggy Lee / The Man I Love t864 等更新しました。

Mark Murphy / Hip Parade st-1299 Peggy Lee / The Man I Love t864 Carol Kidd / All My Tomorrows akh005 Monica Zetterlund / Ahh Monica p08211l Nina Simone / Nuff Said Lsp4065 Joe Williams / Sings Everyday mg6002 Helen O'Connell Bob Eberly / Recapturing The Excitement Of The Jimmy Dorsey Era WS1403 Zoot Sims / Trotting Pr16009 Gene Ammons / Jungle Soul Prt7552 Kenny Burrell / with John Coltrane prst7532 Freddie McCoy / Peas 'n' Rice Prst7487 Gerry Mulligan Astor Piazzolla / Summit RTV25046 Stan Getz / Getz Gilberto V6-8545 Kenny Burrell / Soul Call Prst7315 VA / Homegrown III Yehoram Gaon / OST Kazablan CBS70128 David Martial / Bambou Tabou abl7031 Dogliotti / Candombe For Export 33106 Nouvelle Formule / Tiers Monde Cooperation IAD/S003 Juan Pablo Torres / Algo Nuevo ld-3664

~bamboo music~

530-0028 大阪市北区万歳町3-41 シロノビル104号

06-6363-2700

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#mossad 101#tv shows#daniel syrkin#yehuda levi#yehoram gaon#tzachi halevy#daniel litman#aki avni#itay tiran#hana laszlo#illustration#vintage art#alternative movie posters

1 note

·

View note

Text

Universo cultural sefardí: tradición oral y kantes clásicos

🇪🇸 Emisión en Sefardí: El programa ofrece un recorrido completo por la música, historia y tradición oral sefardí. Se presenta un cuento de la escritora Matilda Koen Sarano, "El djueves de la necocherá", que relata con humor la preparación de comidas sefardíes. Además, se incluyen investigaciones sobre las comunidades sefardíes tras la expulsión de Sefarad y una serie de refranes transmitidos por generaciones. El programa también cuenta con kantes tradicionales y romances, destacando "Yo hanino, tú hanina" por Flory Jagoda, "Hero y Leandro" por Santiago Blasco, y "Kuando el Rey Nimbrod" y "Adio kerida" por Yehoram Gaón.

🇺🇸 Broadcast in Ladino: The program offers a comprehensive exploration of Sephardic music, history, and oral tradition. It features a story by writer Matilda Koen Sarano, "El djueves de la necocherá," humorously recounting the preparation of Sephardic dishes. Additionally, it includes research on Sephardic communities after the expulsion from Sefarad and a collection of proverbs passed down through generations. The program also features traditional kantes and romances, highlighting "Yo hanino, tú hanina" by Flory Jagoda, "Hero y Leandro" by Santiago Blasco, and "Kuando el Rey Nimbrod" and "Adio kerida" by Yehoram Gaón.

youtube

#judaísmo#judaism#jewish#judío#judíos#jumblr#cultura sefardí#sephardic culture#matilda koen saraon#matilda koen saraon z''l#el djueves de la necocherá#comidas sefardíes#música sefardí#flory jagoda#hero y leandro#yo hanino#santiago blasco#yehoram gaón#kuando el rey nimbrod#adio kerida#Youtube#ladino#sephardic#sephardim#sefardí#sephardi jewish#música

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

youtube

Gleiches Lied (ein sephardisches Wiegenlied), zwei unterschiedliche Interpretationen. Der Chorsatz ist zwar sehr einfach, aber ich mag ihn gern. Und Yehoram Gaon ist sowieso klasse, den hatten wir hier ja schon einmal.

0 notes

Link

On my first date with Yehoram, I offered him a sip of my prosecco at the hip Tel Aviv bar I had brought him to. He tensed, paused and quietly replied, “I’m not sure if I can. I don’t know if it’s kosher.” I immediately recognized his confession for what it was: a coming-out. I told him that it’s fine, that we can ask the waitress if the wine has a certification, that I grew up in an observant family too. He finally breathed.

I already knew that Yehoram is female-to-male transgender. In fact, it was the only thing written on his dating profile. Over the course of our year-long relationship, and then our seamless transition into friendship late last year, he explained to me that the queer community will often accept that he is trans but not that he is religious. But the same is not always necessarily true of the religious community – and particularly of his family.

There are many preconceptions about his family. The matriarch Mazal, 74, and patriarch Yehiel, 78, were both born in Sana’a, Yemen, and immigrated to the newly-declared State of Israel in early childhood. (Haaretz is honoring their request not to publish the family name.) They are visibly Haredi: Mazal wears long skirts and tucks her hair into modest black caps; Yehiel trims his salt-and-pepper beard, and wears a uniform of crisp dress shirts, black pants and a black velvet kippa.

They speak with heavy Yemenite accents – which have been at least partially adopted by their seven children – and their speech is seasoned with religious aphorisms and allusions. People are surprised to learn that Yehoram, 32, is accepted and supported by his parents, to a degree that is rare even in the secular homes of Tel Aviv.

At their kitchen table in a town near Rehovot, central Israel, Mazal has set out water, juice and a homemade cake. Yehiel has set down a voice recorder of his own, to make sure he isn’t misrepresented. They have a story to tell about being the parents of a trans son, and they have decided that I am allowed to tell it.

Before we begin the interview, both are apprehensive. After much deliberation, they decide that I can publish their names but not their images. Yehiel is a respected figure in religious circles: he serves as his synagogue’s main cantor on the High Holy Days, is a mezuzah scribe and kashrut supervisor for the Chief Rabbinate. He spends his free time poring over religious texts, with Yehoram often alongside him. His son no longer attends the local synagogue in which his father plays so large a role; the congregation knew him before his transition, and it could hurt his family’s reputation.

If someone goes to the rabbi with this article in hand and tells Yehiel that he’s out of the fold, “at our age, there’s no fight left. There’s nothing you can do,” he says. “It would destroy me.” When he thinks I cannot hear him, he says that he suspects that one of his contracts as a kashrut supervisor was not renewed for this exact reason – because of his unconventional family.

But if getting his story out shows religious parents that they can embrace their own LGBTQ children, he wants it published. “I want to help,” he says.

Mazal chimes in. “Both of us do. You hear these stories about parents throwing their children out ... I don’t understand it. I don’t understand how you throw out your child.”

She recounts going to the shivah of a friend of Yehoram’s – the transgender queer activist DanVeg, who took her own life in 2016. “I saw them all in the living room, with their heads on each other’s shoulders. I started to cry. I wanted to hug them all, to go one by one. And they came to me; they saw the look in my eye. There was a man who had become a woman, who came to hug me. And a young girl, and more. I couldn’t take it,” she says, wiping away tears that are coming faster and faster. “More and more of them told us that they’re alone, abandoned by their parents. How can you throw out your child? The child of a human being!”

I get up to hug her, and she cries into my back: “Why? Why would you throw your child out of your house? Why?”

They say they never suspected that Yehoram was different before he came out to them, if not unconventionally, as queer at the age of 18, some 14 years ago.

He did not employ the usual lexicon: “I told them, this is how I am – I’m wearing pants from now on and I’m not interested in men,” he recounts. In Yehoram’s absence, Yehiel recalls it as well. Yehoram sat his parents down in the living room and said his piece, and then asked his parents for a response.

“We got up immediately, as if it were coordinated,” Yehiel says. “We hugged [him] from both directions … and we told [him], ‘You have nothing to be afraid of, no need to worry. You’re our daughter, it doesn’t matter what you do.’” Yehoram then opened his backpack to show a couple days’ clothes inside. “If you didn’t accept me, I would have killed myself,” he told his parents.

From there, they worked to make sure that their son wouldn’t, for one moment, forget that he is loved and cared for. They also made sure that he could live a normal life. “It was important that he be self-sufficient, have a respectable career, be able to build a life without us,” Yehiel explains. “Every day, I’m afraid that he won’t be here. I think about how he can build his life so he’s not dependent on anyone else.”

Mazal and Yehiel tend to refer to Yehoram with female pronouns when he isn’t in the room, and occasionally slip into them when he is. To her, Mazal says, he will always be their daughter. “It’s hard for me,” Yehiel concurs. “[He] should be patient.”

Mazal calls him by his chosen name – an anagram of his birth name – to make him happy. “And to connect with [him] – what can you do? We love [him] either way. [He’s] our daughter.”

There have been difficulties in accepting him along the way, she concedes. But like many parents of LGBTQ children, they are mainly rooted in concerns that he will be able to live a safe, fulfilling life.

No one should mistake their acceptance for liberalism – they repeatedly note that the Pride Parades, with their scanty clothes and glitter, are unsightly. “The left brings it in,” Mazal says. “Non-Jews from abroad, with all their tattoos and whatnot.” However, their embrace of their transgender son and the many queer people who have passed through their doors does not come in spite of their firm religious beliefs, but is the direct result of them.

Yehiel, a lifelong religious scholar, has poured over sources biblical, talmudic, rabbinic and kabbalistic. The kabbalistic concept of the soul provides a simple explanation for the transgender phenomenon, he believes.

“We have the knowledge that Jewish souls can be reincarnated into anything – into non-Jewish families, into animals, even into food,” Yehiel explains. “We were taught that the soul of a man can be reincarnated into a woman, in order to remedy something he had done in a past life.”

When Mazal was pregnant with Yehoram, she had already given birth to five daughters and was hoping for a son. The couple went to a respected rabbi, who told them to buy a bottle of wine for the circumcision ceremony and to come see him 40 days into the pregnancy. Yehiel says that when the time came, it was hard to get hold of the rabbi to schedule an appointment, and they were only able to see him eight months in. The rabbi gave them the blessing regardless.

“The body was already formed female,” Yehiel says, but the prayers had worked: “The soul was male.”

And there is scripture to back up the existence of LGBTQ people within Judaism. “You’re not different, you’re not strange,” Yehiel says. “This [phenomenon] has always existed. It’s in the Torah, and it’s in the mystical sources.” Mazal adds: “It’s a shame that we don’t lay this out these days, to have everything written up and organized to say that it’s all there in scripture.”

At 26, Yehoram told his parents he was transitioning. He underwent top surgery – a double mastectomy – without informing them. “On the one hand, it hurt us,” Yehiel admits. “For us, it meant that’s it – it’s sealed. If he’d told us in advance, we would have told him to wait. Maybe the situation would change.”

But what’s done is done, Mazal says. “What hurt me is that [he] underwent the surgery and I wasn’t there. That ate at me.”

Both loudly agree that the important thing is that he is happy and healthy. “We hope just for success – and thank God there are many successes, so everything is alright,” she says. “I’m just waiting for children,” she laughs.

Yehoram, who has taken a seat next to her, smirks. Mazal jokes about him coming home pregnant one day. He’s slightly irked, but jokes along. A couple of years ago, he froze his eggs through Ichilov Hospital’s fertility clinic for transgender men, and hopes to one day become a father, no matter how he has to do it. His parents strongly supported the move. They have 31 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Yehoram asks a question of his own: Whether his parents want to talk about the time they took him to an esteemed rabbi in Tel Aviv, after he came out at 18.

“After he told us everything, we consulted with a rabbi,” Yehiel relays. “I remember that he got angry and yelled at him. I didn’t like that. He hurt him, and I couldn’t stay any longer, so we left.”

“The rabbi told me that I had lapsed, deteriorated in my spirituality,” Yehoram explains. It’s clear that he remembers it vividly. “That I had fallen.”

After that, the rabbi told him to leave the room, and for his parents to stay. “I heard shouting, and then you left the room,” he says to his parents. “You didn’t say anything, I didn’t say anything. We were quiet all the way home.”

No one discussed the incident for days after, and they barely spoke at all. After three days, Yehoram says, he asked his mother what had happened after the rabbi told him to leave the room.

“I didn’t know what happened, I assumed the worst. You told me that [Dad] got very angry and told [the rabbi], ‘How dare you hurt and belittle a Jewish soul?’ You said you had to give him however much money, and that you just threw a small bill onto the table and left the room,” Yehoram tells his mother. “It really surprised me. I thought you were on his side, and then I suddenly heard that you were on mine.”

When he is with us in the room, Yehoram sometimes seems agitated by his parents’ insistence that their acceptance has always been complete. He tries to direct them toward other instances, other rabbis they don’t or won’t recall. It is often difficult for parents to acknowledge the pain or discomfort that their actions caused their children, even if they were accidental. Mazal brings out a picture from Yehoram’s bat mitzvah, of them embracing the young girl he was. They look almost exactly the same, 20 years later, beaming. Young Yehoram, in a long-sleeved, high-necked dress, is smiling, but the smile does not reach his eyes.

Elisha Alexander, co-CEO and founder of the transgender advocacy and information organization Ma’avarim, says that even though Yehiel and Mazal’s acceptance of their son may seem unique, he would like to think it’s more common than we assume.

“There are religious and even ultra-Orthodox people who accept their trans family members, but it’s usually in secret. The main problem in these communities is the leadership,” he says.

But if more of them realized that embracing their children was a matter of pikuach nefesh – the Jewish concept that saving a life supersedes most religious commandments and norms – they would be more inclined to find a halakhic solution to integrating transgender people into these communities.

There is also a misconception that acceptance is a binary choice: That any parent who does not kick their transgender child out of the house or disown them has, by default, accepted them. “This could not be further from the truth,” Alexander says. “Accepting your child means accepting every aspect inherent to them, including their gender identity, pronouns and so on.”

When parents refuse to do so, their child may seek acceptance elsewhere. He adds that studies show that acceptance within the family drastically reduces the suicide rate among transgender people.

Knowing this, Yehiel says that any parent in his position must continue loving and supporting their child. “This child can fall,” he says. He does not mention it, but he is aware of the stories and statistics: trans youth who find themselves on the street face high rates of abuse and exploitation. Thirty to 50 percent of transgender teens report suicidal thoughts and behaviors – a rate three times higher than for teens overall. But that figure falls to 4 percent when families accept and embrace them, says Sarit Ben Shimol, manager of the Lioness Alliance for families and transgender children and teenagers.

Yehiel adds that it is the duty of parents to give children the support they need to thrive. “As a parent, it is your responsibility to tell your child: You are my child and you are my life. My life depends on you. Watch over me so that I can watch over you,” he says.

As we get up from our seats, Yehiel looks at me for a moment and asks, “If it’s not too personal – since we already opened up the topic – what is your relationship like with your parents?”

I tell them that I talk to my parents, and especially my mother, almost every day. That it was difficult for them to come to terms with my sexual orientation as well, and that sometimes I have an inkling that it still is, even if they won’t say it outright. But I try to be patient.

“Good,” Mazal says. “It’s important to be patient – they’re learning too.” She embraces me again, and Yehiel rests a hand on my shoulder. They invite me to come again, whenever I like. “After all, you’re like our daughter, too.”

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

Difference between music that fits a character and music a character might listen too

#It’s referenced in the draft that wylan spent some heist earning money buying vinyls of fun. Mika and vampire weekend#No comment on quality just a deep character truth#Nina jamming to Janis Joplin and the cranberries to drown out Kaz talking at any point soooo true#Jesper Phil lynott/thin lizzy man ESP in 80’s au#Jesper (cool 70’s/80’s)#ABBA and Donna summers!!!#Zoya - ofra haza and yehoram gaon and other Hebrew classics#Matthias: uhhhh missing time for being in a cult so just plays his dads cassettes without shred of irony#U2 and depeche mode. Personal Jesus etc#Colm and Jesper karaoke scene to ordinary man by Christy Moore too#Still working on Inej b#Horrible au says Inej is from jersey so she does rep her homeboy Bruce

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy birthday, Golani!

The Golani Brigade was formed 73 years ago on February 22, 1948, and was the first brigade formed by the IDF, earning it the nickname the “#1 Brigade.”

During the War of Independence, Golani fought on many fronts and participated in numerous battles. They captured Nazereth, repelled Arab forces in the Battle of Tiberius and Safed, and liberated the Upper Galilee.

During the Six Day War in 1967, Golani was appointed the daunting task of capturing the Golan Heights. The brigade swept through the Golan, eventually reaching and conquering Mount Hermon.

Tales of Golani soldier's heroism spread like wildfire throughout the country, prompting famed musician Yehoram Gaon to release the song, “Golani Sheli” (My Golani), which transformed into the brigade's unofficial anthem and perhaps the most famous army tune.

During the Yom Kippur War, Golani soldiers reconquered the Hermon and advanced deep into Syrian territory. During the First Lebanon War, they defeated the PLO-held Beaufort Castle and participated in the siege on Beirut. In the Second Lebanon War, the brigade fought in the battle at Bint Jbeil where Major Roi Klein jumped on a live grenade and sacrificed himself for his troops.

Golani's emblem is a green olive tree on a yellow background. Its soldiers wear brown berets symbolizing the connection between them and the earth. There are 4 battalions in the Golani Brigade: #12 Barak, #13 Gideon, #51 First Breachers, and Reconnaissance (special forces).

The “#1 Brigade” has been the highest requested brigade in the IDF for years and has earned the reputation as one of the most decorated infantry units in the IDF.

Im Tirtzu

11 notes

·

View notes