#yegHistory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

My friend Sissy Thiessen Kootenayoo of @wasesabaexperiences is the first Indigenous person and feminine person to host the City of Edmonton’s New Years Eve celebrations. I got to be there to see history being made. They did great and I'm glad that, even for a moment, was able to witness it. Taken with Canon T6I Location: Churchill Square, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Taken: New Years Eve, 2022 Taken and edited by David William Paturel (Dis & Dat Media) Edited with the software PhotoScape All rights of photo(s) reserved to Dis & Dat Media (David Paturel) #disanddatmedia #photography #photo #churchillsquare #edmonton #yeg #alberta #canada #indigenous #newyearseve #edmontonhistory #yeghistory #night #nighttime #nightphotography #nighttimephotography #winter #2022 #winter2022 #newyearseve2022 #history #edmontonphotography #yegphotography #2spirit #twospirit #goodbye2022 #hello2023 #event #party #cold (at Churchill Square, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cm60KQPJO0I/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#disanddatmedia#photography#photo#churchillsquare#edmonton#yeg#alberta#canada#indigenous#newyearseve#edmontonhistory#yeghistory#night#nighttime#nightphotography#nighttimephotography#winter#2022#winter2022#newyearseve2022#history#edmontonphotography#yegphotography#2spirit#twospirit#goodbye2022#hello2023#event#party#cold

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog Post 4: Winter

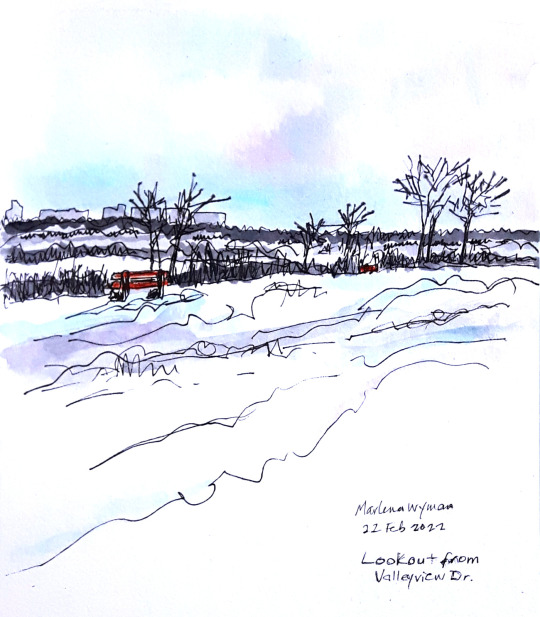

Words by Adriana A. Davies, Jan 21, 2022 Artwork by Marlena Wyman Jan 22 – Feb 2, 2022 Artists-in-Residence at Yorath House

North Saskatchewan River looking north from below Yorath House

Since time immemorial, human beings have been afraid of ice and snow. Indigenous Peoples in the Northern Hemisphere donned warm clothing made of the skins of fur-bearing animals and used snowshoes to get around. In Northern Europe, the Swedes invented cross country and downhill skiing, saunas and a honey liquor called mead, and that began to change things.

Being born in warm, southern Italy, my first Canadian winter after immigration with my family as a child was a huge shock. My parents took my siblings – sister Rosa and brother Giuseppe – and I to the old Army & Navy store downtown (that’s where most immigrants first shopped) and bought us our first winter gear. Rosa got a wool coat and ugly brown long stockings; Giuseppe and I got one-piece snowsuits with long zippers that inevitably jammed. My suit was red. Against all instructions not to do so, I licked an icy lamp post and jumped on the ice on top of puddles and broke through, and had to walk home with water-filled boots.

I quickly learned to respect winter and fear the cold. I admit it: I am a wimp who prefers to look at winter through a picture window. Yorath House has plenty of those and during the cold spell this January, it is a wonderful place to be. I wrote my first poem there watching the snow fall but I’ve been writing winter poetry for a long time.

The dualities of winter – cold that can kill and also the extreme beauty of frozen landscapes – have captivated me. I remember reading Anglo Saxon poems at the University of Alberta and the later Icelandic sagas that told of life in Northern climes. One account described it being so cold that words froze in the air as people spoke and, when spring came and they defrosted, the air was full of a cacophony of sound. Here are some winter poems.

Snow

In the North Saskatchewan River Valley, Snow has formed A white crust That cracks And settles In footprint shapes.

Underneath, The brown leaves Are undergoing A transformation— Becoming New soil. The Yorath House grounds Are over-run by dog walkers on this winter day. The dogs run ahead Evading their owners, On the track of wildlife. They disappear For minutes on end And I am left alone wrapped in silence. It is almost too cold To be walking outdoors. Fingers and toes Chilled to a dull ache. Ice forms around eyelids And scarf covering my mouth. Nature asserts itself, Making the human irrelevant In this landscape Where sleep and death Are one And absolutes converge. No sunshine Or bird song In this dark place Defined by negatives. An eternal winter of the heart. Beyond the solace of human touch. Hoar frost has covered everything. So much whiteness— Field, trees and sky. All the same But different— Incandescent. So easy to forget That one lives in a populous city Visible above the trees At the top of both river banks. Black swallows Break from the tree tops And form a ragged line As they fly for the horizon.

Walking the Dogs

The beagles are ready to walk. They bay excitedly And run in circles, Tangling their leashes around themselves and us. They are off— One moment dragging me behind, The next, Stopping so suddenly That I nearly trip over them, As they inhale deeply, Whatever catches their eye in the grass— Whether the scent of another dog, Or morsel of discarded food. Others we meet Are of enormous interest To these curious hounds, Who want to bound up To adults, children and other dogs, And must be restrained By a pulling back on the leash. Their unbounded enthusiasm, And enjoyment of the fall day, Leaves no leeway for reflection, Or melancholy. Only when they tire, As we climb the final hill, Do they settle to a sedate pace, Leaving me in charge at last, Able to admire the golden haloes, Punctuated by clusters of red, Which are the Mountain Ashes In their fall glory, And to contemplate The grove of fir trees Pierced by a single shaft of light, Which focuses on the leaf-strewn earth, And feathers out to the spiky edges Of the trees surrounding the clearing. It is not only the beagles who perk up With excitement When the suggestion is made, "Let's go for a walk."

Winter Dawn

Dawn's rosy finger Warms the grey clouds And tips with fire the smoky stacks Of the mist-shrouded power plant. Another winter dawn And journey to work, Driving on the river road, Conscious of the vapour coming off the water. Tree branches outlined in frost, And the valley edges Crowned with highrise apartments— All part of this dream. The coldness rather than driving me indoors, Catches my imagination And I wonder At the metamorphosis. The palette of white and grey, Is augmented by mother-of-pearl, As warm life asserts itself And night becomes morning.

Reflections on Nature and Art

1 Silent ravens Soar Above the desolation, Making invisible patterns In the cloudless sky.

2 The birds are audible But not visible This winter morning In the city. Bare-branched Mountain ashes and poplars Provide no shelter. Only dense firs With their crowns of cones Offer hospitality. Songs emerge From nowhere— Sweet, Repetitive, Melodic. I have no language To describe them Other than— Chirp, chirp To-whit, to-whit. But they have Animated An ordinary morning Walk to work, Made the trees emerge From between buildings And remnants of houses On this once residential street Nature asserting itself And gladdening the heart.

3 The air is heavy With snow. No distinction between Earth and sky, Only the ribbon of asphalt Leading onward. Suddenly, A flock of snowbirds Appears, Hanging in the sky Like a character In Chinese calligraphy.

Their wings formed By a sable brush Dipped in Indian ink. Other than us, The only living element In the landscape. Until the clouds begin To move And the wind picks up snow Sweeping it down The length of the valley Disturbing the stillness. Heeding a secret call, The cluster of buntings Explodes outward And they disappear Into the pervasive Whiteness.

Snow Storm

Jagged bowing, Suggestive of icicles and cold winds, A long-dead composer’s evocation of the seasons, My background on a winter day. But the real snow Drifts down, Gently, Past dark spruce branches, And the frozen blood-red berries Of Mountain Ash. It accumulates, Imperceptibly, The stillness punctuated By the rhythmic rise and fall of bows, On massed fiddles, Now evoking the descent Of myriad individual flakes Audibly drifting down. But behind can also be heard the silence That is so much a part of falling snow.

Now, the flakes are denser, As the sharp, insistent violin bowing, Is joined by the guttural rasping of cellos, And the snow drifts and eddies around the halo of a street lamp. In the music, The storm rises and abates, But, today, nature does not toy with us, Offering only a contrast, To quiet reflection, On what the next year will bring.

Gathering of Crows

Winter afternoon, Trees outlined in the half light, Branches bare Except for the occasional Detritus of an empty nest, Evidence of another season. Some trees Have black shapes in them, Like over-sized leaves. On a closer view, A congregation of crows emerges, Sitting at branch ends in silent colloquy. So many, Perhaps fifty, Perched For no apparent reason, That I could discern In this urban landscape. An enigmatic picture That I take away. Nature, Defying me to find meaning In a gathering of crows In Midwinter.

My Parkview Garden

The trees in my back garden Are fir, Manitoba maple And another, I cannot name.

On this winter morning. They are still and, Seemingly, lifeless Until a slight movement Catches my attention. A squirrel, Leaps from branch-to-branch And tree-to-tree, Finishing with a high-wire act On the powerline. The contemplation of winter, When plants do not grow, The clearing, empty of birds And their sweet song. That time of endings, Of being trapped In the ruins of the past, Unable to evoke remembered music. Always, the clearing in the woods, In the River Valley. The stillness, Silence, The pastness of things. The inexpressible beauty Of the snow, Blinding in the sunlight And masking death. The birds have fled But I am here, Contemplating winter And making my own music. The sound of the wind Wrapping itself around the house, Whistling past obstructions And making the cold siding crack. This signals a subtle change That is not evident Until morning When water drops from the eves. Warm Chinook winds Have come over the mountains, Loosened the grip of winter And given us a taste of spring. The insistent drip of water Creates stalactites And stalagmites Of yellowy ice. But this is only temporary— Nature teasing us with hope; The next night, the house tenses, It is winter again.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On July 1st 2003, I did a dual art exhibition show called “High Anxiety,” in Edmonton,Alberta. This was right after I graduated in Fine Arts art the University of Alberta. I found a flyer for this show. I did figurative painting with eerie and unnerving themes. One such painting was a giant painting called “Unexpected Visitor.” I wasn’t able to save these paintings. I believe I sold one painting at the time but I can’t remember which one. All I know was it wasn’t the “Unexpected Visitor.” There is also an old photo of me standing in front of the what use to be the “Pie in the Sky” gallery. I don’t know what’s happening in that location now. Those were the days when I had hair on my head. Here’s what I did in the past... but really looking forward to what I’ll be doing in the future. #fineart #painting #paintings #macabre #macabreart #artistsoninstagram #artist #yeg #yegarts #edmontonalberta #yeghistory #albertacanada (at Edmonton, Alberta) https://www.instagram.com/p/BsrBodCgcaX/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1vwnz3yquapy6

#fineart#painting#paintings#macabre#macabreart#artistsoninstagram#artist#yeg#yegarts#edmontonalberta#yeghistory#albertacanada

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I'm working with the Jasper Place Community History Project doing research and writing about the area. This includes writing articles on behalf of the organization for SPANN, the community newspaper serving Stony Plain Road and surrounding neighbourhoods. My first article is about JAHSENA, the local Jewish archives that relocated to the Jasper Place area a decade ago. I'll also be working on other articles concerning Jewish history, as well as general history, in the area for SPANN as well as the Jasper Place Community History Project's website. In the meantime, you can download the latest issue of SPANN at: https://www.stonyplainroad.com/spann/ @spannjasperplace @jasperplacehistory @stonyplainroad -- #yeg #yegwestend #yeghistory #JewishEdmonton #JewishYEG #edmonton #JasperPlace #StonyPlainRoad #SPR #yegwriter https://www.instagram.com/p/CcLve6DvKph/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#yeg#yegwestend#yeghistory#jewishedmonton#jewishyeg#edmonton#jasperplace#stonyplainroad#spr#yegwriter

0 notes

Photo

REPOST • @fairmontmac Have you ever wondered what was for dinner 106 years ago? This was the first menu from the Hotel Macdonald in 1915! When was the last time you ordered “consommé double” at a restaurant? *Visit our bio link to see how see today’s menu #TBT #MACmemories #yeghistory #FairmontMAC #Fairmonthotels #yegbrunch #yegbreakfast #FairmontMAC #Fairmonthotels #yegdt #edmonton #yeg #alberta #canada #calgary #yeglocal #yeggers #edmontonliving #yeglife #yegliving #vintagemenu https://www.instagram.com/p/CLx6nOxgw_5/?igshid=hvf531rgqu3s

#tbt#macmemories#yeghistory#fairmontmac#fairmonthotels#yegbrunch#yegbreakfast#yegdt#edmonton#yeg#alberta#canada#calgary#yeglocal#yeggers#edmontonliving#yeglife#yegliving#vintagemenu

0 notes

Photo

A few of my favorite webcomic pages from “Women, Work, and our Union” for @_aupe_ 💪 . . . . . #illustration #comic #webcomic #comicartist #yegcomics #illustrator #womensrights #abunion #yeghistory #educationalcomic #digitalart #yegarts #yegillustrator #yegmade #handlettering #womenatwork #yycarts #heyemilychu (at Edmonton, Alberta) https://www.instagram.com/p/BteXqMCgQjh/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=bus6rihf9015

#illustration#comic#webcomic#comicartist#yegcomics#illustrator#womensrights#abunion#yeghistory#educationalcomic#digitalart#yegarts#yegillustrator#yegmade#handlettering#womenatwork#yycarts#heyemilychu

0 notes

Photo

We have a very limited number of the 1984 Edmonton Access Catalogue in stock, a great little time capsule of #yeghistory - get one before they're gone! #yeg #whyteave (at Vivid Print)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Old enough to remember a lot of this #yeghistory (at Royal Alberta Museum) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bp8A8neAFaH/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=18zt6kzbmqlgs

0 notes

Photo

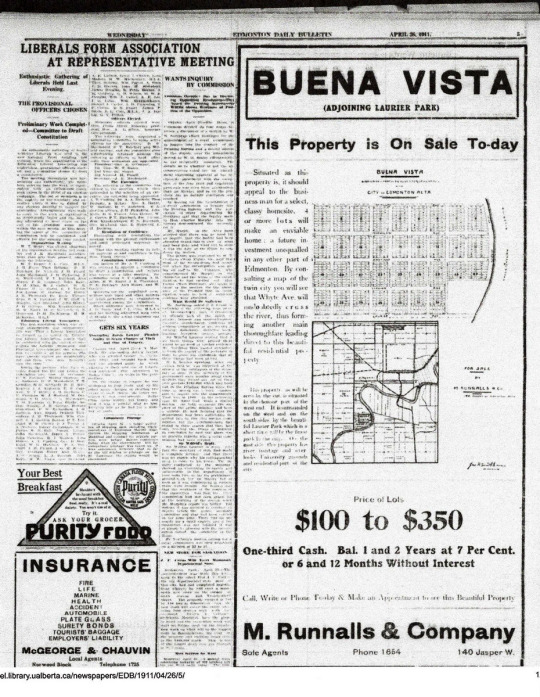

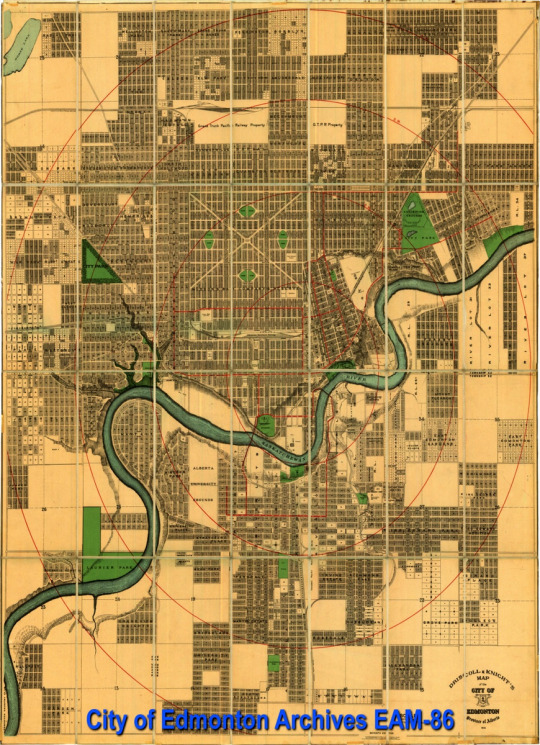

Edmonton, 1912.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog Post 8: Family and Home

Words by Adriana A. Davies, February 2022 Artworks by Marlena Wyman February 2022 Artists-in-Residence at Yorath House (Photographs as credited)

It is time to write the final blog post, No. 8, which focuses on family. It’s hard to believe that our two-month residency is up. It’s been an amazing experience and has resulted in a surge of creativity for Marlena and myself.

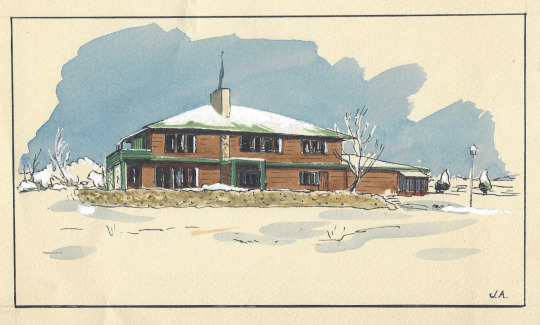

Yorath House ca 1980s. Yorath family collection.

Yorath House was a family home for 43 years and was a passive observer of all the joys, hopes and sufferings of the people who lived there. To understand this, I’ve done a lot of research on key family members. This started with revisiting the work on Christopher James Yorath, Dennis’ father that I did for his entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, which I began in 2013. The family entrusted me with biographical accounts, correspondence, a memoir, newspaper clippings, speeches and other materials about C. J. but also touching on other family members.

Among these treasures was a small watercolour sketch of Yorath House done by a member of the team at Rule Wynn and Rule. Little did I know at the time that my attention would be focused on the house and that I would be a “resident” there for two months in 2022 (at least during the day). It seemed natural for me, therefore, to spend part of the residency focusing on the Yorath-Wilkin families and their experiences. This spun off naturally from one of the goals of our residency, which was to examine the relationship between space and place, and also time and the river.

Architectural drawing of Yorath House by Rule, Wynn & Rule, 1949. Yorath family collection

In this respect, the experiences of the families are both unique and universal. Historic structures are not just about the design and building materials but rather about these and also the occupants who lived or worked there. The range of human experience, I believe, somehow leaves a residue in the walls and natural landscapes. I know that this is a fanciful and, to some, an absurd notion but, humour me, visual artists and writers get to play with this kind of stuff! I think that I can be both rational and fanciful as I move between non-fiction and creative non-fiction. I propose to tell some family stories in both prose and poetry, and show that human beings turn space into place.

The Yoraths: Father and Son

C. J. (Christopher James) and D. K. (Dennis Kestell) Yorath, father and son, were skilled businessmen and “community builders.” They were part of the industrialization and urbanization of the City of Edmonton and Province of Alberta in the twentieth century. C. J. was born in 1870 in Cardiff, Wales, the son of William Yorath and Sarah Hopkins. In 1904, he married Emily Kestell.i The couple had two sons, Dennis and Eric, and a daughter, Joyce. From 1895 to 1898, he studied civil engineering at Cardiff College (later part of the University of Wales). When he completed his studies, he obtained work with the City of Cardiff and learned a great deal on the job about issues such as drainage, street-railway electrification, road and bridge building, and artificial gas delivery. In 1909, he moved to London and did some lecturing at the Westminster Technical Institute and, more significantly, worked for the firm of Sir Alexander Richardson Binnie on a massive drainage project in the city. At that time, many ambitious young men looked to the colonies to further their careers. In 1912, he became aware of a major urban planning project: Canberra had been designated the capital of Australia. He submitted an application to develop the master plan; he was unsuccessful and then turned his eyes to Canada.

C. J. Yorath, Who’s Who in Canada, volume 16, 1922, page 748.

In 1913, C. J. submitted an application to an international competition to become city commissioner and treasurer for the City of Saskatoon and won. He may have learned of the competition from his brother Arthur, who had homesteaded near Oyen, a town in east-central Alberta, near the Saskatchewan border and north of Medicine Hat beginning in 1911.i C. J. was charged with preventing the City from declaring bankruptcy – the state of many Canadian municipalities at that time as a result of the worldwide recession and a dramatic fall in the value of land and property, and huge decline in the property tax base. On April 23, Yorath sailed from Southampton, England, on the Olympic (a sister ship of the Titanic) with wife, Emily, and their two sons Dennis and Eric. They arrived in New York on the 30th and reached Saskatoon early the following month.

C. J. brought not only engineering and project management expertise to his job but also a vision about the proper layout and development of urban areas. In a 1913 article that he wrote for Western Municipal News, he approvingly quotes Aristotle’s definition of a city as a “place where men live a common life for a noble end”; stresses that municipalities should be purposefully planned; and laments that too often “cities have grown up in a haphazard manner, and many a beautiful spot turned into an ugly accumulation of bricks and mortar.” Emphasizing natural beauty and artistic symmetry, Yorath allied himself with the Garden City movement, describing the ideal municipality as “beautiful, well planted and finely laid out, known and characterized by the charm and amenities which it can offer to those who seek a residence or dwelling removed from the turmoil, stress and discomforts of a manufacturing district.” He not only got the City out of debt, he also left them with a “Preliminary plan of greater Saskatoon,” which made tangible his vision of a city with plentiful green space and, among other innovations, a ring road around its outskirts. While it was shelved for lack of funding, as was the case in many municipalities across the country at the time, it was a legacy.

In 1921, he accepted a higher-paying job in Edmonton and, on March 23, the Edmonton Journal, welcomed him to the city and noted, “There are no airs of the autocrat or supposed superman about him.” He had a very large mandate: he was commissioner of public works and utilities and joint commissioner of finance, in effect, Edmonton’s city commissioner. C. J. found that the municipal debt was higher than that of most western cities and, during his three years in Edmonton, succeeded in putting the city in a stronger financial position. While more than a third of Edmonton’s debt was tied to its waterworks, electrical powerhouse, street railway, and telephone system, under his tenure all of these services were financially self-sufficient and provided additional tax revenue. Newspaper articles reveal that he was a popular speaker and visited other municipalities; a favourite topic was “public ownership vs. private control.” He was a strong believer in the latter.

Edmonton City Council minutes during C. J.’s term frequently deal with discussions about the provision of gas to residential and business customers. In 1909, Eugene Coste, who worked for the Geological Survey of Canada, made a major gas discovery in the Bow Island area near Calgary. He established Canadian Western Natural Gas in 1911 and built a pipeline to Calgary. In 1924, C. J. joined the company and, in 1925, became President and managing director of Canadian Western Natural Gas, Light, Heat and Power Company, which supplied not only Calgary and Lethbridge but also towns in between.i By 1927, Northwestern Utilities and Canadian Western had become subsidiaries of the International Utilities Corporation, an American holding company, and by 1930, Yorath was president and managing director of several other Canadian subsidiaries.

In June of that year, he arranged the sale of all these firms to the Dominion Gas and Electric Company, an American subsidiary. After this massive deal (the Calgary Albertan estimated its value at $30 million or $505,056,287 Cdn today) was completed, C. J. remained in charge. He was at the peak of his career when he died as a result of a heart condition on April 2, 1932. Family members believe that it was the stress of his work that precipitated his health issues. His obituary in the Albertan encompassed nearly an entire page and outlined his business successes, as well as his community service, noting: “But the heavy burden of business cares did not curtail Mr. Yorath’s interest in sport and community life. He was a prominent member of the Kiwanis Club and a keen golfer, having been a member of Calgary Golf and Country Club for many years.” He was also a member of the Masonic Order, as were most members of the British establishment, and was interested “in conservation of the gas supply.” The article notes: “He had just returned from Edmonton, where discussions regarding conservation measures took place, when he was stricken with the illness which proved fatal.”i The work that he set in motion would result in the establishment of the Petroleum and Natural Gas Conservation Board in 1938 (later the Alberta Energy Conservation Board).

C. J. was part of Calgary’s business elite and the family’s home at 1213 Prospect Avenue in the Mount Royal district was an enormous brick and wood Craftsman-style home with some Tudor elements built in 1912. The district was initially nicknamed “American Hill” because of the number of wealthy Americans who lived there (this was pegged at about one-third). Some were initially drawn by the ranching opportunities and others by the coming in of the Turner Valley oil field in 1914. The formal photograph of the house in the bottom lower right corner shows the gas fittings in the home to demonstrate the importance of the fuel in a modern residence. The house was similar to the one built by Eugene Coste for his own residence, in 1913, which had 28 rooms and was located at 2208 Amherst Street in Mount Royal. As the district name suggests, the subdivision was built on an escarpment that provided expansive views of the new city. Like Old Glenora in Edmonton, there was a covenant that directed that only homes of a certain (high) value be built there. C. J.’s granddaughters remember the extensive grounds that surrounded it including gardens and flowerbeds and also allowed horses to be kept on the property.

C. J. Yorath residence, Calgary, Alberta, ca. 1930. C.J. was President and Managing Director of the Calgary Gas Company. A sketch of the plumbing and heating system appears in the lower right-hand corner. Photographer: W. J. Oliver. Glenbow Archives, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary, PB-946-8.

Dennis Kestell Yorath was born in London, England in 1905 and was educated in London, Saskatoon and perhaps Edmonton. His father’s wealth allowed him, as a young man, to enjoy the benefits of being part of Calgary’s elite and he learned to fly a plane and play polo. A number of young Canadian men had learned to fly during the First World War, among them Calgary’s Captain Fred McCall and Edmonton’s Wilfrid “Wop” May. They were pioneers who helped to set up flying clubs in their communities. Dennis knew both of them and was a charter member of the Calgary Flying Club, which was established in 1927, and obtained a pilot’s license in 1929.i He was also an expert horseman and played polo; in fact, according to his daughters, he played in a game with the Prince of Wales, Edward VIII, when he visited Calgary in the 1920s. According to newspaper accounts, he played for the Calgary Blues Polo Team among whose members was J. B. Cross. His father, A. E. Cross, was a rancher and co-founder of the Calgary Stampede, the Calgary Brewing and Malting Company, and Calgary Petroleum Products (1912). J. B. and Dennis would follow in their father’s footsteps. The pages of the family’s photo albums include pictures demonstrating these pursuits.

Dennis Yorath painting by Marlena Wyman – image transfer and oil stick on Mylar. (Photos from Yorath family collection ca 1930).

With respect to his career, Dennis started work with the Imperial Bank of Canada in Edmonton where he worked for two years and, then, following his Father to Calgary began work, at the age of 19, for Northwestern Utilities and, in 1925, for Canadian Western Natural Gas. His father’s early death at the age of 52 catapulted him into a leadership position in the companies. In 1933, he married Bette Wilkin, whose father, among his various real estate and insurance interests, was also a co-founder and shareholder of the North West Brewing Company. According to family history, the Wilkin and Yorath families knew each other when C. J. and wife Emily lived in Edmonton, and that Dennis dated Bette’s older sister Jean until she found the man she was to marry. Dennis then turned his attention to Bette. After their society wedding, the couple went on an extended honeymoon to China and Japan, and brought back some lovely antiques including a Chinese chest, Japanese screen and brass inlaid tray table and two stools. They moved into a cottage on the grounds of C. J.’s home in Mount Royal. In 1940, Dennis left his jobs to serve his country becoming director of pilot training for southern Alberta, based at the No. 5 Elementary Flight Training School near Lethbridge as part of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.i In 1941, the School relocated to High River. Bette and their two daughters, Gillian (born 1936) and Jocelyn (born 1938) remained in Calgary. Just as his father’s career had been impacted by an oil and gas boom, so would Dennis’ career. The coming in of the Leduc and Redwater fields, in 1947 and 1948, triggered massive development, and prosperity for not only Edmonton but also the entire Province of Alberta. In 1949, Dennis was transferred to Edmonton to become general manager of Northwestern Utilities and, in 1956, became president of both Northwestern and Canadian Western Natural Gas. He served as chair of both from 1962 to 1969. From 1957 to 1973, he served as Director of the International Utilities Corporation and, from 1973 to 1981, as vice chair of International Utilities Corporation. On March 2, 1971, the New York Times noted: “TORONTO, March 1 (Canadian Press) – The International Utilities Corporation reported yesterday that its 1970 net income rose to $33,475,000 [worth $242, 562, 610 Cdn in 2022], or $2.42 a share, from $33,070,000, or $2.61 a share, a year ago. The Toronto-based conglomerate, which has administrative offices in Philadelphia, reports its financial results in United States currency.”i

Dennis Yorath headed the Canadian Western Natural Gas Company when it celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. A commemorative book titled Half a Century of Service: 1912 – 1962: Canadian Western Natural Gas Company included photos of its presidents on page 3.

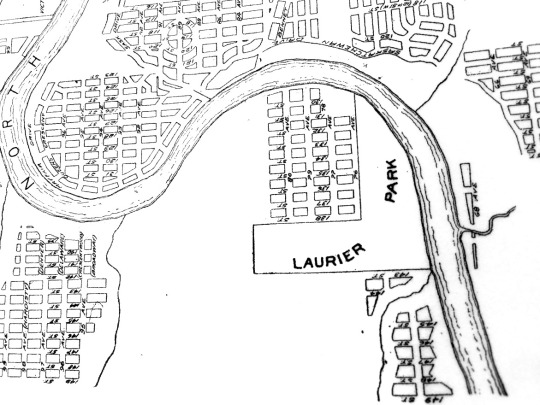

On their move to Edmonton, Dennis and Bette chose to build a “signature” house in the Modern Style designed by Rule Wynn and Rule, just as his parents had chosen a Craftsman-Style House in Calgary. Dennis died on May 8, 1981 as a result of early onset Alzheimers’ Disease. In 1985, Bette had her nephew, architect Richard Wilkin, design and see to the renovations required to create a rental suite on the second-storey of her home to avoid living alone. In 1992, the city bought the 11-acre Yorath property for $900,000 to consolidate public ownership of river frontage in Buena Vista Park. The fieldstone memorial at the river’s edge of the property commemorates not only Dennis and Bette but also her parents, William and Hilda Wilkin, who had given them the land.

Wilkin-Yorath family cairn on the grounds of Yorath House. Yorath family collection.

During his lifetime, Dennis received many honours and was an active volunteer in both professional associations and community organizations. For his war-time service, he was awarded an Order of the British Empire by the British government in 1946. From 1947 to 1949, he served as the president of the Royal Canadian Flying Clubs Association, and, in 1949, was awarded the McKee Trans-Canada Trophy for his contributions to aviation. From 1947 to 1955, he was Director of the Canadian Gas Association (CGA) and served as Vice President in 1951, and, President, in 1953. From 1955 to 1957, he was a director of the American Gas Association. In 1951, he received a life membership in the Edmonton Flying Club and, in 1973, was inducted into the Alberta Aviation Hall of Fame. In 1955, he was president of the Edmonton Chamber of Commerce and, in 1962, headed the United Community Fund of Greater Edmonton. From 1966 to 1972, he served on the Board of Governors of the University of Alberta and was involved with the Friends of the University of Alberta Botanical Gardens; the University awarded him an Honorary Doctor of Laws Degree in 1974. Dennis was active with the Canadian Council of Christians and Jews, the Community Chest Air Cadet League of Canada, Boy Scouts Association and the Salvation Army. He was a supporter of the Edmonton Klondike Days Association and, in 1966, as part of the Sourdough Raft Race, six boats raced from the dock below Yorath House down the North Saskatchewan River. He was a member of the Committee that helped to decide on the design of the Canadian flag. He died on May 8, 1981 in Edmonton.

Mothers and Daughters

The women of the Wilkin and Yorath families lived in a time when they were defined by what their husbands did, and were expected to be excellent wives, mothers and hostesses. This was certainly true for Hilda Wilkin, Emily Yorath and Bette Yorath. Their husbands worked hard and the families were part of the upper middle class elite of people of Eastern-Canadian, British or American origin who dominated the development of Edmonton and other communities not only in Alberta but also the rest of Canada. Their doings can be found in the pages of the Edmonton Bulletin, Edmonton Journal, Calgary Albertan and Calgary Herald. Their attendance at events at the Legislature, church fetes and meetings of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, St. John’s Ambulance and other patriotic societies always referenced them as “Mrs.” or “Miss.” Their first names were rarely mentioned, if at all. They are invisible except in the many pictures in family albums.

William Lewis Wilkin in military uniform, 218th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, ca. 1916. Photo courtesy of Richard Wilkin.

William Lewis Wilkin arrived in Edmonton in 1892 on an adventure and began to make good working at retail, real estate and insurance brokerage. He returned to England in 1904 to marry a childhood friend, Hilda Richardson Carter, and brought her back to the relative wilds of Fort Saskatchewan where he operated a store and served on the town council. Their first child, a son, also called William, was born in 1905, and their fortune improved with the increase in numbers of their family. As property ventures began to dominate William’s business life, he and Hilda decided to move to Edmonton from Fort Saskatchewan. They auctioned their furniture so that they could have a fresh start and also went to England for a holiday with children Bill and Jean. This was not a “steerage voyage” and he writes in his memoir: “The trip over was as far as I remember very nice but not startling. On the boat Bill & Jean (about 4 & 2) shared our nice fairly large cabin at night & had meals & play room in the nursery which was well equipped with everything including a competent nurse.”

Hilda Wilkin (née Richardson Carter) and son W. V. (Bill). Yorath family collection.

Their Edmonton home was located on the corner of 123 Street and 103 Avenue and was a three-storey Craftsman-style home with a wrap-around porch. It was across the street from Robertson Presbyterian Church (Robertson-Wesley United Church today), which was built in 1913, and kitty-corner from the Buena Vista Apartments. Children Margaret Elizabeth (Bette) (born 1912), Robert (born 1914) and Richard (born 1919) completed the family. Their comfortable family home was known for excellent hospitality and, according to grandson, Richard Wilkin, almost every evening his grandparents were “at home” for visits from family and friends. This continued in their new home at Connaught Drive in Old Glenora, which was built around 1945. Both Hilda and William lived to the age of 97 and welcomed grandchildren into their home and even hosted sleep-overs. Their homes were tastefully decorated with English antiques and they adhered to the formalities and civilities of British life with teas and formal Sunday dinners.

Emily “Marnie” Yorath (née Kestell) pictured in formal dress for a wedding or other society event. Yorath family collection.

Emily Kestell Yorath was the perfect hostess for her husband, a leader of the business community, and presided at events in Calgary at their Mount Royal home. The Yorath children – Dennis, Eric and Joyce – all married well and had children. The Yorath children called their grandmother “Marnie.” There was always something to do both inside and outside the grand home. There were extensive gardens as well as games such as tennis and lawn bowling as well as horseback riding. The Yorath children and their spouses took part in not only family events but also other more official entertainments. After her husband’s death, Emily remained in Calgary where her daughter Joyce Yorath Williams and son Eric resided. Eric was vice president of Carlile and McCarthy Ltd., a firm of stockbrokers. Emily died in 1958.

Dennis and Bette Yorath wedding photo taken in the garden of the Wilkin home in Edmonton in 1933. Photographer: McDermid Studio. Glenbow Archives, Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary, ND-3-6389a.

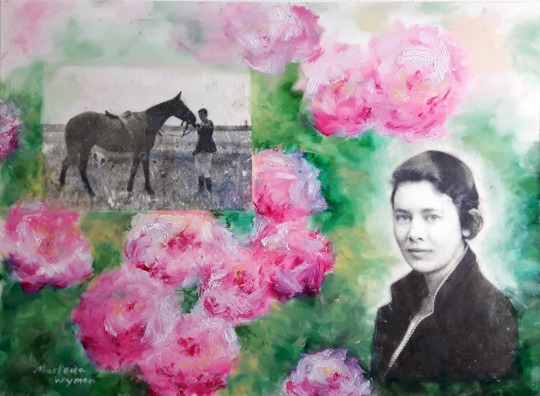

It could be said that Bette Wilkin “married up” but she was undaunted when she moved with Dennis to a modest home, referred to as a “cottage” on the grounds of the Mount Royal property. She had attended a private girl’s school in Vancouver for a time, according to her daughters, and was a superb equestrienne. The wedding photo of her in her parents’ garden in Edmonton shows a beautiful, self-assured and serene young woman. She was prepared to be the perfect wife, mother and hostess. Since Dennis’ father was dead, the oldest son and wife became the principal supports for his widow; and, since Dennis was in the same business, he continued his high-level social interactions with civic and provincial leaders, as well as the business community. Bette tended extensive gardens and bred peonies, rode daily and also raced thoroughbreds in “Powder Puff” Derbies in Calgary.

Bette Yorath (née Wilkin) painting by Marlena Wyman – image transfer and oil stick on Mylar. (Photos from Yorath family collection ca 1930).

Bette supported Dennis in all of his activities including the war-time work with the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. She and her young daughters visited him in Lethbridge and High River where he was based. According to daughters, Gillian Brubaker (née Yorath) and Elizabeth Yorath-Welsh, the couple responded to the call from the Canadian government to help refugees and also befriended some Japanese Canadians interned and re-located to the sugar beet farming areas around Taber and Brooks. The move to Edmonton in 1949 was difficult but Bette took it in stride and with Dennis planned their new home working with architects Rule Wynn and Rule. The joy of the new home was extinguished when daughter Jocelyn died of leukemia in 1950. Sorrow was followed by joy with the birth of Elizabeth Jane. Life in Yorath House was a continuous round of socializing both with family and friends, and business associates and community leaders.

Bette’s taste was evident in the home’s furnishing which were a blend of antiques and contemporary furniture animated by purchases made on their honeymoon trip to China and Japan as well as other international travels. These included an inlaid brass tray coffee table and matching stools, a Chinese chest and Japanese screen. Bette also collected Japanese prints. The symptoms of early Alzheimer’s disease ended Dennis’ career but Bette supported him to the end. Four years’ after his death, she decided that she did not want to live alone and commissioned her nephew, architect Richard Wilkin, to design a self-contained suite to be created on the second-storey of her home. She died in 1991, the year before the City purchased her home.

Family Voices

In my work in community and social history, I’ve found that oral histories and correspondence, memoirs and other documents are an invaluable tool. The first-hand account is both exciting and revealing, and makes history come alive. Besides archival and other primary sources, I had the pleasure of talking with Yorath daughters Gillian and Elizabeth and nephew Richard Wilkin. I will let them speak in their own voices whether through transcripts of interviews or reminiscences.

Interview with Gillian Yorath Brubaker Adriana A. Davies and Marlena Wyman Zoom Conversation, Sunday, 3 pm Edmonton time and 1 pm Alaska time, January 30, 2022

After my parents’ marriage in Edmonton in 1933, they settled in Calgary where he worked. The family home, a “cottage” on the grounds of my grandparents’ large house, was situated near the Sarcee Reserve [Mount Royal] in Calgary. My father was an excellent rider from an early age and played polo including with Prince Edward on his visits to Calgary. One of his polo ponies, Cheetah, was brought up to Edmonton when the house in Buena Vista was built in 1949, in addition to our mother’s horse, Lady Patricia. We had more horses and donkeys in Calgary, but not all were moved up to Edmonton. Both my parents excelled at riding and my mother as a young woman had ridden as a jockey in “Powder Puff” derbies in Calgary and won! She had attended a private school in Vancouver for two years when in her teens. It was Crofton House School.i We rode almost daily and my sister Jocelyn was an excellent rider.

I believe that the Calgary cottage was built around 1920 and my parents bought it and moved in after their honeymoon in China and Japan. My grandparents lived in the “Big House” next door. My grandfather died in 1932 and my father followed in his footsteps working in the gas business in Calgary and later Edmonton (International Utilities).

My father was a skilled aviator who learned to fly in his early twenties. He would fly a Tiger Moth aircraft to our home in Calgary. He was a friend of First World War flying ace Wilfrid “Wop” May. From 1939 to 1945, my father lived in Lethbridge as head of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. He was very concerned about the air crews that he helped train and grieved at the loss of lives. He was away from the family and this was hard for me, my mother and Jocelyn, who was 14-months younger than me.

The nearby community of Taber was a centre of the sugar beet industry and was chosen as a location to intern Japanese from British Columbia, who were designated enemy aliens in the Second World War.i Our parents befriended two Japanese young women, Tammy and Ruby, from the internment camp. My parents also signed on to sponsor displaced persons: the Government of Canada was advertising for host families. They arranged for Eine Kranz from Riga, Latvia to come to Canada and my father located her fiancé Henry in a European internment camp and arranged for their wedding when they arrived. In Calgary, we had a huge garden and the Kranzs worked for us.

In Calgary, I attended St. Hilda’s School, which was a boarding school, and had to wear a uniform.i In 1949, when Father became the head of Northwestern Utilities, we moved to Edmonton and lived with my grandparents until our house was built. We moved in in the fall of 1949. Leaving Calgary was hard – I felt that I was losing all of my friends. I went to Glenora School in Edmonton at 135th Street and 102 Avenue (Stony Plain Road).i Jocelyn and I wore uniforms on the first day of school and we stuck out like sore thumbs. Jocelyn held my hand tightly and shivered. In the 1944 photograph of myself and Jocelyn with our cousin Rick Wilkin, we are wearing our school uniforms and Rick was wearing a robe. The photo was taken at the Wilkin summer place at Kapasiwin Beach on Lake Wabamun.

Wilkin and Yorath Cousins painting by Marlena Wyman – image transfer and acrylic paints on Mylar. (Photos from Yorath family collection ca 1944).

My mother loved the move to Edmonton since she was born and raised there and had family and friends there. It was a “huge move” with not only furniture but also horses and a pony being transported up. The current Yorath House parking lot was a pasture at the time and the Yorath horses as well as some belonging to our neighbours grazed there. There was a shed for the horses. Near the house was also a gravel pit and the Legroulx family lived nearby. There were three or four houses at the top of the hill. The Tellingtons also lived nearby, along the river.

Our house was built on about 14 acres of land and there was a mink farm owned by Esther Fisk nearby. It was 14 miles away from the City and located in wilderness. The house had many flower beds and also fruit trees around it. In Calgary, we also had large gardens including one devoted to peonies, which my mother bred and entered in competitions, some of which she won. She transplanted some of the peonies from Calgary into the Yorath House flower beds. The lawn and gardens sloped down on the land behind the house toward the river, and a large vegetable garden was planted on the side of the house where the garage is.

My parents had lots and lots of parties. Many had lost loved ones in the Second World War and just wanted to enjoy themselves. Cocktail parties took place all the time not only in our own house but also the Bill Wilkin residence [Richard’s family] at 16 St. George’s Crescent.

I remember breaking down when my sister Jocelyn died in 1950 and the first five years in the house I was in a daze. I remember that my parents were away and Jocelyn and I were staying with our Wilkin grandparents and sleeping in the same bed when Jocelyn woke me up and told me that she was not feeling well. I turned the light on and found the bed sheets covered in blood. Jocelyn had had a massive nose bleed. I called our grandparents and they took Jocelyn to hospital where she was diagnosed with leukemia. This was in September and she died in October [Provincial Archives death records show date as Oct 21, 1950]. I made a vow at that time to study radiology and go into nursing.

I attended Westglen High School [now an elementary school] at 10950 – 127 Street as did my cousin Richard Wilkin.i Initially I biked to school but eventually my parents bought me a blue Renault car, which I drove to the edge of the City, and parked on Stony Plain Road and 136 Street and walked the rest of the way. I remember that once while driving through the gravel pit near our house in my Renault, I nearly tipped it over. Baby Elizabeth was inside. We had a maid called Ilse who helped look after Elizabeth.

When I finished High School in 1954, I attended the University of Alberta and as a student worked for Dr. Bill Armstrong, who was a friend of the family. His specialty was ear, nose and throat. Around 1957, when I finished university, I went for a year of travel and work in Europe. I lived in London, England, and Linz, Austria. I remember climbing the Matterhorn and meeting my future husband John Brubaker on the climb. I climbed the West Ridge and he and a friend climbed the East Ridge. We then met in a bar. John was at Yale as an undergrad and attended law school in Charlottesville, Virginia.

In Linz, I worked in a Lutheran Church refugee camp that helped refugee boys who had been active in the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. They were kicked out of Hungary or maybe just left. I worked as a general “dog’s body” in the camp and was similar in age to the boys. Some of the boys went to Canada and established themselves. I returned to Canada but no-one seemed to be interested in my experiences other than mother and father.

John and I got married on December 28, 1959. The day was beautiful but cold and the well froze which meant that the inside toilets could not be flushed. Portable toilets were set up on the grounds. John and I flew to Calgary that night and then on to Washington, DC. There was a storm the next day and I heard that some of the guests from away stayed for three or four days adding to my parents’ worries.

John and I moved to Virginia and, then, in 1962, to Juneau, Alaska, and lived there until 1964 when we moved to Anchorage and we’ve been there ever since. I never went back to medicine and worked in a number of fields. John and I had two children, Heather and Michael.

I remember coming back to Edmonton for a visit in 1978 for the party that my parents hosted for Prince Philip. My son Michael was set to open the car door when the Prince arrived but the Prince opened it himself and said, “Beat you.” My parents knew a number of Royals.

With respect to the sale of our house, I remember that the City had “right of refusal.” I was shocked to see that the renovated house was so open and white on the ground floor. The downstairs was more closed in with “swing doors” into the dining room. There was also a door into the kitchen opposite the freezers on the wall. The dining room walls were pale blue and the floors throughout were teak.

Elizabeth Yorath-Welsh Reminiscences: Part 1: Life at Yorath House

My parents moved up to Edmonton after World War 2 so my father could head up Northwestern Utilities. They built this house in 1949. The land was purchased from a farmer named Stephenson. The architects were Rule, Wynn and Rule.

I was born in 1951. My very early childhood of course is vague, but we did have maids until I was 2. Then there was a lady named Mrs. Bowman who looked after me when Mum & Dad would go away.

As a child I have very fond memories of growing up in the River Valley area now known as Buena Vista. There were quite a number of people living in that area along the river or overlooking the valley. Buena Vista road didn't exist back then, so we used 81st Ave down the hill to 131st St. to get to our house, and it was all dirt/gravel road – awful after a heavy rain!

I remember Old Tom & his horse drawn wagon would come and cut the fields for the hay. He lived up above the zoo before it was built. Also, the milk was delivered by a horse wagon!

By age 2 I was getting to know how to get around rather quickly. Having the "run" of the river valley was not a bad life! There were other farms & small homes throughout the Valley, & the people were all wonderful. There was a chicken & turkey farm right across our field to the north owned by the Bates family. Both Sue & John Bates babysat me. Near them was my best friend, Heather Washburn & her brother, Rod. I would visit the Bates’ first, then carry on in time to watch Heather's Mum braid her long red hair. Then we were off and running. This is all at ages 3, 4, & 5. The Washburns moved away when I was 6. I lost my dear friend to Vancouver!

At the area where Buena Vista Park begins, where the public washrooms now are, is where the Legroulx family lived. Larry & Jean & their 2 boys Claude & Marcel. Larry worked for my Dad both at Northwestern Utilities, & as a gardener & fix (nearly everything) man! Jean also helped out with a lot of the parties.

There were several mink farms around. One was owned by the Blaylocks on what is now 81 Ave at the bottom of the hill. That road used to go straight through until about 1970 when the city built the berm. Chris Blaylock was also a babysitter, & I played with his sister Lynne. Further up that 1st hill and to the right were several families, the Neimans. Kim was my age, & his sister Noanie also babysat me. The Shaws, who owned Shaw plumbing, had 4 boys & a girl. Actually one of the boys lives in the last house on Buena Vista beside the top end of the Zoo, Alan Shaw.

Laurier Heights School opened in 1958. By then a bunch of young families had moved into the Valley.

A wonderful couple lived across the field in a house that was beside the little hill that goes down to the parking for people going for walks. Esther & Ted Fisk & Ted’s brother, John. They had a few mink for a while, but then got rid of them to grow raspberries. Esther became our housekeeper & was a Nanny to me. A wonderful woman who taught me a lot! I would often have lunch at their house & tea after school. I will never forget going canvassing with her when I was about 5 or 6, & one of the houses we stopped at was Al Oeming’s. There in his back yard was this magnificent creature!! His Cheetah! Well . . . although a bit scared at first, I fell in love with Cheetahs!

I learned to ride with Betty Tellington who lived with her Mum & brother across from the big field where the dogs play in the off leash area. That used to be a horse field & riding ring. Betty had some great horses & I loved riding. We had some fun gymkhanas in the ring! I was not bad at the barrel racing! Betty was yet another babysitter as well. And her mother was my grade 6 teacher. There were several other small houses past the Tellingtons, and a large house at the end where the bridge to Hawrelak Park is now. I don't remember much about them though.

In 1958 they were building Buena Vista Road to accommodate the opening of the Storyland Valley Zoo in 1959. Rather daunting to see those huge earth movers rumble down the road! But that changed things considerably. It soon became the new way to get to our house. And Laurier Park was built . . . which took care of the family of Métis that lived in the “woods” 1/2 way into the Park with their team of huskies tied up outside their shack.

Another shocker, there was a couple in the very early 50s until about 1956, who lived in the River Bank in a cave. I would not have believed it if I had not been in it! It was near where the Métis lived. I think Dad helped them out. It actually looked kinda cozy.

Before 1958 there were very few houses even up to where the IGA is now [not the IGA at 91 Avenue and 142 Street but another store that no longer exists near Laurier Heights School]. It used to be a Loblaws. And across from it was also small houses, shacks & farms. We bought our chicken eggs from a family who lived in a shack there. And, yes, shacks were common housing back then. I also remember our milk being delivered by a horse driven cart. We had well water until I was 9. Dad quickly got rid of it after my sister's wedding in December 1959. The well froze the night before the wedding. A shock to wake up to. 150 guests coming to the reception & no water. Luckily, December 28th 1959 was a warm day. We were able to be outside around the fireplace. The caterers had to bring water in. The hairdresser had to come at 7 AM & bring hot water to wash Jill's hair. She looked fabulous despite it all & it was a day to remember.

Across from where the Washburns & Bates had lived, a family from Holland moved in with their then 6 children. The Matthezings. A very good family. My father helped them over the 1st few years with getting city water, gas heating, & a proper fridge as I recall. The girls & I quickly became playmates. Liddy & I had a “club house” kind of a hole in the woods which is still there today.

Things began to change in the 60s & certainly in the '70s a lot of these places got bought up by the City Parks Dept. It has now become the Buena Vista off leash area we all know today. Thank God we hung on to this beautiful house my parents built, and it was declared a Historical Site so the public can now enjoy it today!

Reminiscence Part 2: Mum, Marnie & Granny

Marnie was my Dad's mother. I remember her as being a lovely, warm, caring lady! She would come up to stay with us at least once a year, and shared my room. I also remember going to see her when we went to Calgary. Occasionally we stayed at her house & I always went in to see her in the mornings! Unfortunately she died when I was 5. She was staying with us when I got that spanking when Heather Washburn & I were caught playing by the river. She was very consoling, but also clear that Heather & I had made a wrong choice, that playing by the river could be dangerous. (So as you see, though Mum may have said something once, I learned the hard way that playing by the river was not a good plan).

Granny & Grandpose [Wilkin grandparents] were my favorites! I spent many weekends at their house on Connaught Dr. And the family often met there for drinks after work. Sunday dinners were also frequent. They were very patient with me, especially given I made a fort out of 2 card tables right in the middle of their living room! But I always helped out and cleaned up when asked. One big tradition was after Christmas Dinner we children were allowed to walk down the center of the dining table! Another Christmas Tradition was them coming out to our house to be there to open presents. I was not allowed to see the tree until they got there! Grandpose was gruff in a very amusing way . . . always teasing us. Granny would sometimes admonish him by saying "Tod, you're scaring the poor child!" Later as I got older I learned a lot from Granny, especially cooking. I loved to bake with her & after finishing school it became apparent I was good at it & was sent to Cordon Bleu in London. Granny lived to be 97, and was always very spry. She would love to tell everyone "I'm 97 you know!" She was an amazing dressmaker & knitter. She made most of my Barbie doll clothes. Imagine the fidgetiness of that.

Mum was a wonderful & very gracious woman. She was very clear when I was a child what my chores were . . . setting the table for dinner, cleaning up, helping guests with things . . . get this get that. "Jane will get it". . . "Jane will do it." We loved to go "hacking" in the woods and cut branches out of the way . . . and look for wild onions. (I have to see if I can find those again this spring.) Parties were certainly plentiful & friends would pop down on weekends for a drink in the garden. I loved my parents’ friends. I usually helped Mum cook the dinners, and also did a lot of the flower arrangements. A wonderful bunch of people.

I would attend most of the dinner parties, often helping out the caterers in the kitchen as well. Then of course there were the wonderful Pre Derby parties held the night before the Canadian Derby in mid-August. Dad was head of the racing commission, so the parties were pretty grand events! We always had a marquee set up as there were often showers or even thunderstorms! And in 1976 there was the party for all the Heads of State for the Commonwealth Games. Prince Phillip made an appearance there as well. Dinner even with just the 3 of us was always in the dining room. Properly served & with wine . . . which I started drinking at a young age. My godfather gave me a wee wine glass at the age of 8!

Mum loved the outdoors, so we walked, x-country skied, downhill skied & rode horses. She also played tennis. We went up to Sunshine Village to ski every year when I was a young kid. I learned to ski there when I was 8 . . . and was a very fast skier! She always loved a good afternoon of going for a walk then having a cup of tea by the fire. We also loved to garden, and had a huge vegetable garden and flower gardens. Dad always grew daffodils & tulips in his greenhouse for spring . . . and the living room was a sea of color when they were in bloom!

When I was in my 20's and proved my riding skills, Mum & I would go ride horses belonging to a good friend . . . ex race horses. We would ride down in the fields below the Edmonton Country Club . . . often encountering coyotes. We always had Mum's dog, a Great Pyrenees & my Labrador. Naturally, there was always quite the interaction . . . Pyrenees – 1; Coyotes - 0! But it was always amusing!

She also loved fishing, & I would sometimes join her & her friend on trips down around Caroline to Nordegg. They fly fished & I used a casting rod with a worm . . . I caught the bigger fish! Always delightful fun.

Apropros your writings on Keillor Rd [Yorath Art Residency, Blog Post 2], I had a couple of friends over for dinner one night back in the '70s, & Dad was home as well . . . Mum was away. As we ate our dinner we watched a couple up on a small clearing just off Keillor Rd set up a card table with a nice tablecloth, candelabra and silverware. The lady then served her gentleman friend a nice dinner! So lovely!

I miss those days! So many delightful friends, and always something interesting going on!

Interview with Richard Wilkin Adriana A. Davies and Marlena Wyman Wednesday, 2 pm, January 19, 2022, Yorath House, Edmonton

I was born in 1938, the son of William Wilkin [1905-1986], the first child of William Lewis (Tod) Wilkin [1875-1972]. I remember that my grandfather was a questionable driver, who handled his car as he would a team of horses and buggy. He was very strong minded; my grandmother Hilda was a “brick of a woman.” She was a childhood friend of Tod’s, and he returned to England to marry her [circa 1904]. Their other children were: Jean (Jefferey) [born 1907], Margaret Elizabeth (Yorath) [born 1912], Robert [1915] and Richard [1920], who died in the Second World War.

Sometime before 1905 the Wilkin family moved into a big house on the corner of 123 Street and 103 Avenue with a detached garage/stable/servants’ quarters. The main house was a three-storey single family home. Around 1946, they built a new house at 10314 Connaught Drive in Old Glenora.

My parents Bill Wilkin and Katherine Frances Tyner married in 1928. They lived in the apartment over his parents’ stable when they were first married. My parents built a house at 16 St. George’s Crescent also in Old Glenora ca. 1948. This is where I grew up. The house was sold to Cam Sydie years after my parents’ deaths. The Sydie family (owners of Fabric Care Cleaners in Edmonton) were close friends of the Wilkins’ ever since the 1920s.

My father and Uncle Robert were with W. L. Wilkin Ltd until the 1970s. William L. Wilkin and Co. acquired the Buena Vista land along the River Valley – not only the 12 acres of what became the Yorath property but also a similar amount to the East. My father planned to build a house on the adjoining 12 acre property but changes in bylaws in 1950 enabled the City to expropriate land from private land owners in order to extend the parks system in the River Valley. I don’t know the financial details of the acquisition of the Yorath property. Certainly, as head of Northwestern Utilities, Dennis would have had adequate compensation for the move to Edmonton from Calgary.

I remember a number of small houses along the road in front of the Yorath House, maybe five or six. One of the houses was the residence of the Yorath’s maid/friend, who along with her husband were caretakers of the property. According to my cousin Elizabeth Yorath-Welsh, this was Jeanne and Larry Legroulx.i The area was rural and the neighbours raised small livestock. Bette and Dennis kept several polo ponies on their property at that time. Dennis had been a keen polo player in Calgary in earlier years.

The Wilkin building in downtown Edmonton was sold around 1969-1970 and my grandfather got rid of his insurance and bond business. My father and Uncle Bob retained the real estate component and had offices on the ground floor of the Buena Vista Building. My father’s career was always connected to his own father’s, including the North West Brewing Company (later Bohemian Maid), of which he was president at one point. The building was located below Saskatchewan Drive and above Walterdale Hill; it has been for many years the City of Edmonton Artifacts Centre.

The Yoraths and the Wilkin families were friends with many of the business leaders in Edmonton during the 1950s through the 1980s. These included such names as Munson, Milner, Macdonnell, de la Bruyère, and Mactaggart.

I remember numerous dinner parties with family, friends and business colleagues. I remember Gillian’s Christmas wedding in December 1959 to John Brubaker, a young lawyer from Philadelphia. I was a groomsman. The wedding was at Christ Church Anglican on a Saturday; the septic tank failed [Gillian and Elizabeth say it was the well], and they had to bring in portable toilets placed in the field at the back of the house, two for men and two for women. I remember the well-dressed guests having to go out through the snow to use the facilities. Gillian and I were and are close friends.

As the head of Northwestern Utilities, my Uncle Dennis had many social commitments and had a public presence. I remember that, for a Klondike Days Breakfast, my Aunt Bette wore a beautiful lace dress from ca. 1910-11 that belonged to her mother Hilda Wilkin. In 1985, my Aunt Bette, who was living alone after her husband’s death, came to me as nephew/architect to create the separate apartment on the second storey of the house. The tenant was a friend of Bette’s, John Layton, and his partner. I remember the City, over the years, pressuring Dennis to sell the house for parkland; a deal was worked out that allowed them to live there so long as they chose. I remember that my grandparents were extremely sociable well into their 90s. They hosted a drop-in/cocktail hour almost every evening. They did this until their deaths in their late 90s.

Tour of the house:

The architects were Rule Wynn and Rule – who were the most prominent in town, and had the largest practice during the 1940s and 1950s. John Rule did the design for the Yorath house. I subsequently worked for RWR one summer when I was studying architecture. I attended the University of Washington from 1957, where I studied architecture.

The house was built on a floodplain, thus it had no basement. Instead, it had a dugout area under part of the house that was filled with rock for drainage in case of flooding. A few years after it was built, the river did flood and the water came up almost to the level of the main floor of the house. There were no utilities when it was built because City infrastructure did not reach that far out of the city at that time. There was a well for water and oil tank for heating and cooking. The house did however have power. On my return from Italy in 1968, I lived with my ex-wife, Karen, in the House for several months while Dennis and Bette were travelling.

The house was not as open as City renovations have made it today. A hallway ran the length of the main floor from the living room to the kitchen where the posts are located today. The living room’s wood-burning fieldstone fireplace wall continued with a partition between it and the dining room. The sunken living room was entered through an open doorway directly across from the main staircase to the 2nd floor. The walls were stained mahogany and there was a floor-to-ceiling built-in bookcase on the right of the door (along where the current accessibility ramp is located). The dining room was located next to the living room and it also was closed in with a door or case opening from the corridor. Next to it was the kitchen which was also enclosed. There were windows and a Dutch door out to the garden on the end (south-east) wall. Kitchen cupboards were located on both sides and there was a sitting area and table at the north-east end. A stove and fridge were located on the north wall. The freezer cabinets were located in the corridor, in the same spot as they are presently. Across the corridor was the ironing/service room, plus the main furnace/utility room.

The large master bedroom was located at the south-west end of the second floor. The bedroom area was where the fireplace is (the fireplace was natural gas). The bed was located on the west wall where there are no windows. A large dressing room and master bath were located at north-west end of the room. The door leading to the hallway was located on the short south-west wall around the corner from where the present doors are located. The present doors were originally a wall. The full-length balcony is original to the house. The present-day washroom was part of Elizabeth’s bedroom and the original bathroom was between Elizabeth’s and Gillian’s bedrooms. Gillian’s bedroom was at the far south-east end. Across the corridor from the girls’ bedrooms was the recreation room.

The house was renovated to include an apartment on the second floor after Dennis’ death. Bette retained the master suite and 2 bedrooms, and the rest was converted into a self-contained apartment; stairs led to it from near the garage.

A Maid or Nanny’s Tale Based on a telephone interview with Ilse Ella Messmer (born Hanewald) Adriana A. Davies, January 29, 2022

Around 2011, Ilse at the prompting of her children began to write a memoir; she had taken a writing class at the Lion’s Seniors Centre in Edmonton. Included in the memoir is an account of her work as a maid/nanny for Dennis and Bette Yorath for five-and-a-half months in 1953. I asked for permission to quote from her account in a Yorath House Residency blog post and she agreed. She was delighted to be interviewed.

Ilse Hanewald was born on a small farm owned by her parents that was 20 kilometres North of Dresden. They witnessed the bombing of Dresden by the Allies but fortunately were outside of the range. Her brother Karl was a soldier in the German Army and was injured and, after convalescing, decided to immigrate to Canada because he “didn’t want to become a Soviet coulee” in East Germany. He left around 1951 and worked, first, on a farm near Winnipeg; next in the Town of Kerrobert, Saskatchewan; and, finally, in Slave Lake at the air base as a cement finisher. Ilse, who had studied at an agricultural college for a term and started work in the office of a collective farm. Not happy with the work, she decided to begin a nurse’s course at the Görlitz Hospital in the town of the same name in East Germany near the Polish border. She hadn’t finished her course when her brother sponsored her in 1953. She boarded ship on January 31 and left from the Port of Bremerhaven. She had fled to West Berlin via East Berlin and was helped by some friends of her parents who lived in the English Zone. On board ship, she felt alone – she says “I felt that I had burned all my bridges.” She frequently cried herself to sleep.

The Yorath period of her life was “like a dream.” Coming from East Germany, it was a huge change. She sent parcels home with coffee and cocoa for her family; she also sent chocolate; she preferred not to eat it herself but rather send it to her family. She had arrived with two small suitcases. The “match” between her and the Yoraths was made by immigration officials in Edmonton, who arranged for a meeting at Immigration Hall. Ilse could not speak English but she felt that Mrs. Yorath had a “kind face” and agreed to work for them. She says of the Yorath House, “For me it was a good place to come to; I hold it dear in my heart.” She arrived in February 16 or 17, 1953 and felt that the house was away from everything. She had Thursday afternoons off and Mrs. Yorath would drop her off downtown but she had to make her own way back. Every second weekend she had off. She worked for the Yoraths for just under six months and left so that she could study English and better her circumstances. After completing English and bookkeeping courses, she was able to find work in a bank and later married.

Ilse’s Memoir Excerpt 1: Arrival

Karl arranged for a friend to give them a ride to the Yorath House but they got lost around 142 Street and 87 Avenue and had to telephone Mrs. Yorath. She told them to wait there that she would come and pick them up.

She arrived with baby in car seat, we left Karl’s friend behind, and she would bring Karl back to the city after I was settled in their home. Driving we had been very close, one more hump and a bend we would have seen across the snow-covered meadow the stately Yorath house, as we did now. First thing on arriving we were greeted by two friendly black Labradors. All the while the Baby about fifteen months old eyed us intently, as her mom peeled off her baby-blue woolen coat and leggings to put her in her crib to sleep upstairs. Mrs. Yorath showed us through the rest of the house and then ferried Karl back to town, as I took to my littler room across the kitchen, unpacking to stay.

My situation seemed to me more than adequate and I would handle what was before me, however very difficult would be learning to understand let alone speak this eccentric “Weltsprache” so far much confounding me. Later that day I became introduced to Mr. Yorath and their teen-age daughter Gillian, each as we met extending their hand in a formal gesture of Welcome to Canada. Mrs. Yorath explained to me that my day starts mornings at seven, I set the alarm clock in my room. Also there 3 were uniforms folded in one drawer for me to wear, for which I was grateful, since my wardrobe was quite limited. Near the front entrance was a cloak room with washbasin, mirror, and beside a private toilet for my use.

Next morning perkily dressed in my uniform and on time I entered the kitchen to meet Mrs. Yorath, who was beset by two hungry dogs, their feeding time. Bindy, the smaller and calmer was the mother to Skippy, her lively male offspring about three years old and were very friendly family pets. Their beds were in the garage, a connecting door with a swing flap gave them entry into the house. Also to the north-west end of the house was the furnace room and the place for the dog’s food bowls, we filled them with water and dry dog food. Next in the kitchen we prepared an electric coffee percolator, taking it through a swing door into the formal dining room, it was placed on a side board, plugged in an outlet.

Here we set the table for two with place mats and simple blue earthenware dishes, stainless steel flatware, complimented by washable napkins. Toast was made in the kitchen, in a warmed silver dish with glass inset and cover brought to the table, as well apple juice in small glasses. Mr. Yorath wearing a business suit came downstairs and the couple sat down for breakfast.

Into the kitchen walked Jill, greeting me with “Good Morning” Ilse, setting the kitchen table for two, making toast, all the while chatting and showing me about, inviting me to join her at the table and encouraging me to choose from cornflakes with milk, toast and jam with peanut butter. Jill went off with her father who took her to Victoria Composite High School [actually Westglen High School] before starting his work day as General Manager at Northwestern Utilities, their office on 104 Street south of Jasper Avenue. Mrs. Yorath attended to the Baby bringing her to the kitchen where she sat her in the seat of a low play table to be fed breakfast, a fine milled product of grains from a box called “Pablum,” mixed with warm milk. For now I sat with them, smiling and listening while Baby regarded me with her curious eyes, until the dogs showed up and broke the spell, between them was great mutual fondness. Jane was a lovely contented fifteen-month-old, bright, responsive and playful, early on I thought her a little boy, what with the blue woolen winter outfit and daily she wore little overalls and Dr. Denton’s pyjamas for the night, none of these items were pink, also the name “Jane” did not strike me then as feminine.

Several times a week I washed diapers, and folded returned them to her room, when I spotted little dresses in her closet I did wonder. Soon then Mr. and Mrs. Yorath with Jill had to go out for the evening and would I mind giving the Baby her bath and put her to bed, yes, with pleasure I smiled, and found Jane to be a little girl after all. Yet another snowfall in March, a bright sunny day followed and Mrs. Yorath packed Jane with a blanket into a sleigh, inviting me to come along for this pleasant outing in a lovely winter scene, accompanied by our playful dogs.

Ilse’s Memoir Excerpt 2: Kitchen, Living and Dining Room

Yorath Kitchen painting by Marlena Wyman – image transfer and oil stick on Mylar. (Photos from Yorath family collection ca 1980s).

The nerve center of any house after all resides in the kitchen, the layout of this one was practical and modern with plenty of smartly arranged cupboards and counter space, incorporating necessary electrical appliances. A screen door opened to outside next to a large picture window and bench seating area around a dining table. As a divider a counter attached to the inside wall reaching into the middle accommodating a double sink, as well a dishwasher cum cloths washing machine, for washing cloths the wire rack was removable. For washing dishes I found it more fanciful than useful, the dishes had to be dried still and those it could not accommodate washed in the sink, Mrs. Yorath nodded in agreement and henceforth all dishes were washed in the sink. Mrs. Yorath prepared the meals, I was eager learning new ways, with Imperial Cheddar she made a tasty cheese sauce for home-grown broccoli, out of a freezer compartment located across the hallway from this kitchen. The only telephone was in the kitchen, mounted on the wall beside the swing door to the dining room and conversations were brief, nowhere to sit.

Furniture in the dining room consisted of a long trestle table, a corresponding side board and both built of a heavy wood, almost black and polished to a shine, ten or twelve high back ladder chairs of ebony wood with seats of woven hemp material. On the side board placed against the wall to the kitchen sat a silver tray with silver tea set, two covered silver serving dishes with removable insets of tempered glass and daily in use, as well a spot for the electric coffee percolator. Above hung a large picture of an English Hunting Party, and before it on the floor lay a fair size thick red rug having a large motive of a tiger woven in. On the inside wall a counter with cupboards and drawers from floor to ceiling held table ware and linen, all for entertaining guests. The outside wall has tall windows, on the end a door to a patio and outside fire place, the dividing wall covered by field stone as it is backing the fire place in the living room, and opposite a door leaving the dining room into the hallway, at this point extending into a foyer.

The front entrance is at the south end of the house, it opens into a small ante room with the next door opening into the foyer, to the left is a cloak room, and also the beautifully crafted wooden staircase starts winding its way up, a lovely chest of drawers holding mittens and such with mirror sits conveniently to the side. From the foyer facing east taking two steps down enter a spacious living room with its warm and friendly atmosphere, focal point on the inside wall is a large fire place, width and height set with rustic field stone and meeting the outer wall which has a row of tall windows with a door mid-ways. The southern wall as well has several tall windows, and heavy lined drapes could be pulled over all windows for privacy at night. The back wall above the wainscot paneling is fitted with shelves that are laden with a library of books of every description, awesome and intimidating since I could not even read their spines, as I did my task of dusting I opened one or another rather dumfounded.

Next to the shelves was yet a cabinet with record player and collection of records, such as Rogers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma, Rhapsody in Blue, and Glen Miller Music, contemporaries of that time. Where the wainscoting and the bookshelves end is a divider of wooden struts with a flowerbox meeting the steps, across the steps meeting with the fire place runs also a flowerbox, all with healthy thriving plants, philodendrons and amaryllis in bloom, and the dark wood paneling behind is painted with an iconic mural large as life, Eastern in origin. No space was left for other pictures, and none needed, the large windows providing scenic pictures with their seasonal changes.

Ilse’s Memoir Excerpt 3: A Party