#YorathHouse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

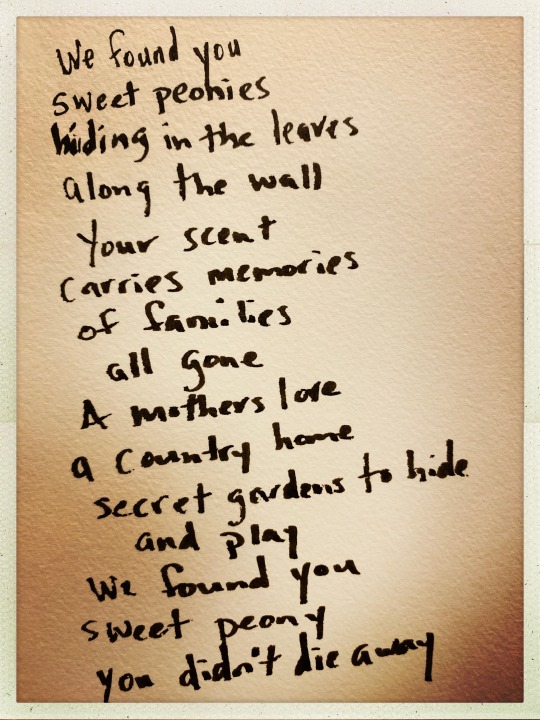

Yorath House Studio Residency Wrap-Up: Thea Bowering and Jody Shenkarek

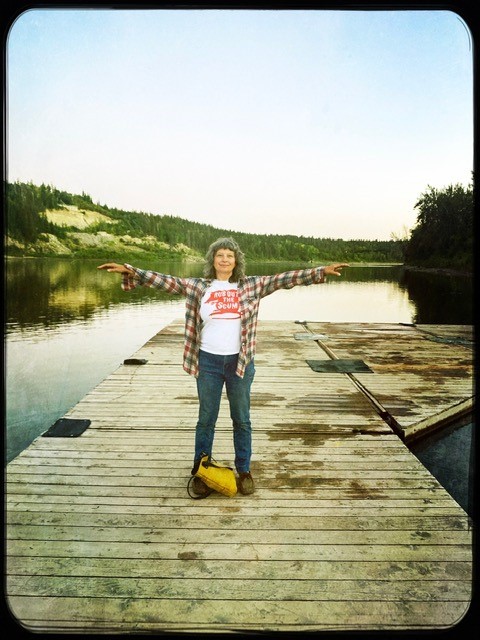

Long-time friends Jody Shenkarek and Thea Bowering were the third artist pair to take up residence at the Yorath House Artist Studio Placement this year. Over the summer, they began their long-talked about collaboration that blended Jody’s music with Thea’s storytelling.

Now that their residency has concluded, the artists are sharing a final update on their time at Yorath House with reflections, prose excerpts, and images. Read more about their residency on the YEGArts blog (introductory post, reflections #1, reflections #2) and check out Jody and Thea's Instagram @sistersofyorath .

Thea Bowering: Final Blog Post

I've lived in Edmonton for two decades now, and if I think of my life as a story, sometimes I find that ironic: I never imagined spending the last of my youth in the geography I had dismissed in my Can Lit 100 courses. I always hated those "foundational," multi-generational stories about people arriving and staying in a place on The Prairies, hated slugging through pages that described life in dusty landscapes I thought no one in their right mind would want to live in. Over the last two decades, I've written short stories about the urban landscape of Edmonton. I would often forget I live in a river town, that there is a river down there, flowing through the basin of the city. When I did picture the North Saskatchewan, it was frozen, not necessarily with ice, but as it would be on a postcard printed who-knows-when sitting in a motel/gas station card rack. Greetings from Edmonton! In red cursive. Greetings from anywhere!

I'm terrible, I agree. A good part of the reason I wanted this residency had to do with an intense need to be better, get down into the valley and close to the river to find a lightness, an expanse, to be away from trucks and cement, my cramped and failing house, unfurl my sedentary body and tired mind and simply push them into green--become less ironic. Every day I was working at Yorath House, I would walk the short path to the dock that reaches quiet out into the river. And with water below me, the green and brown banks all around, the crazy swirling white and blue sky far above, I would stretch out waiting for the currents of "the Universal Being [to] circulate through me." But this didn't happen. I looked glumly at the lucky ones floating down the river on paddleboards, holding their beers, wondering if the Universal Being was flowing through them. One day walking up the ramp from the dock, back to the main path, I saw off to the side a fully intact dandelion puff, the largest and most perfect I'd ever seen. I bent down and stared into its perfect roundness. It looked back at me, a giant eyeball on a stalk, its spore-design an iris. It was a perfect eyeball looking at me. My whole imperfect body staring back, recoiled. I realized, as much as it relaxes me and makes me happy, Nature also makes me feel like a terrible human, with some impenetrable construction column inside that keeps out the blowing spirit. I am more at one with the crumbling city.

But it was my aim to write something about things I hadn't tried to write about before: nature and local history. I did end up reading and being influenced by writers I hadn't read before, who write on nature: Ralph Waldo Emerson and Emily Dickinson. And I ended up learning a lot of things I didn't know much about: the Métis lot system, the history of scrip, the Indigenous and Métis community that lived between 1935-37 along the edge of the city, 142nd street, the street I drove down every day to get to Yorath House. I learned that the practice here of taking apart material history and abandoning it is as old as the city itself. When the last original Fort Edmonton was dismantled in 1915, the Alberta Government promised the people it would reuse the timber in a heritage or museum-like way. Instead, the pieces of fort lay about below the parliament building and eventually vanished. There are many great rumours about what happened to that timber. Similarly, Dennis Yorath tried to donate to the city the eight-foot fieldstone chimney that sat on his property, all that was left of a cabin built by English Charlie, a famous early settler and gold panner. A letter from a city secretary to Dennis reads: "As you know, the fireplace was the oldest relic of early Edmonton still in existence. Without your permission for removal, it would have been lost forever." Well, the chimney was lost forever, deemed too fragile to move and re-erect near John Walter House or the reconstructed Fort Edmonton. For years it had sat, houseless, in Laurier Park, without signage, a curiosity for passersby. And after it was dismantled, where did its stones go? I became obsessed with this and trolled the field next to Yorath for old looking stones, ha!

There is, however, also a beauty that comes from the way the material past is neglected in Edmonton--rather than cleaned away, it is often left in piles for whomever wants it, left to fall down on its own in beautiful weathered ruin. In my stories about cities, I focus on the flâneur: a modern social and literary figure--solitary, urban, wandering, rebellious--who goes far off the set paths of the city to witness and recount the visions of urban life that are neglected, strange, or in ruin. As Jody and I poked about in the bush along the paths of Yorath, in our mode of flânerie, we found evidence of old river homes--possibly going back as far as the Métis and early European settlers. (We image, anyway!) We find a line of stone foundation, an old hearth, a large pile of completely rusted tin cans, a very old gear a tree has grown into.

In one of my favourite essays of flânerie, Virginia Woolf's "Street Haunting," the speaker says she must cross London alone at dusk to buy a pencil. This is just an excuse--as a woman at her time had to have a purpose, usually related to shopping, to leave the house alone for a walk. Her real purpose is to write about all the strange and chance spectacles she sees along the way. This wandering on foot and with words is something I was trying to do with the long piece I was writing at Yorath. (I've submitted excerpts from it in previous blog posts.) In one way, in my mind, our version of Woolf's pencil is the Ghost Pipe--the flower we sought and thought about throughout our residency. It spurred on our walks and meditations about many things: growing older, grief, thoughts about beauty, nature, and the fragility of ourselves and our world. Now that the residency is over, I am going through withdrawal, not being in the valley and on the water and walking paths every day. But I also know that I have found the spot in Edmonton I can return to, for solace and the inspiration to continue this long poetic-prose piece about this place. I'm going to include the last two entries I wrote while at Yorath. I don't think they really gives a sense of closure; they're just the latest in a string of them that continues.

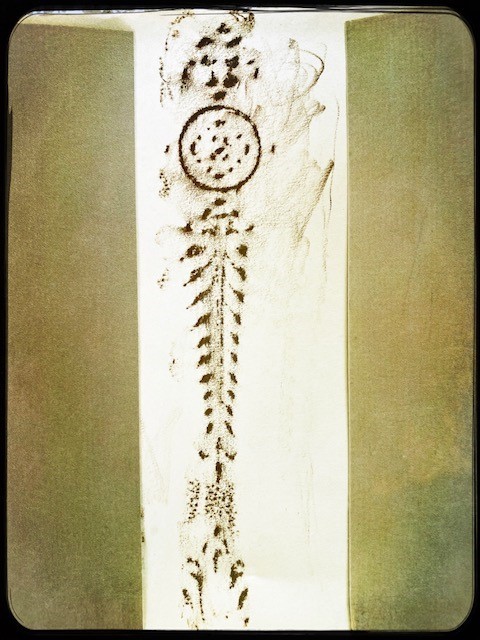

30.

Ten weeks here and I haven't yet written about grief. Even though it's what we started with. Even though it's all around and in everything. Your loved one's ashes catching wind over water. My loved one's ashes buried in an old settler orchard. air, water, fire, and earth. God's eye woven by someone and hung, a star, on a saskatoon berry bush over our little cluster of ghost pipe. The narrative did not go as we hoped it would. Does it ever? We did, in the end, get to see it--but not here. By a different piece of the river. That day under the Mill Creek Bridge, the police were evicting a community who had been living in the ravine for a while. The police were cheery and relaxed as a mattress with a bloom of brown in the middle fell into a storage container. This was all we could observe through the greenery. We heard rustling close by, along the bike path, but we did not go see. Did we learn how to sit beside grief? The moment of finding the flower was not an epiphany, did not bring about a sudden change, but brought empathy, real and useless. We returned almost daily to the tender stalks, to sit in vigil. All around us things died quickly or slowly, unnoticed by walkers and joggers and cyclists. A caterpillar writhed silently as wasps dived onto it, taking out chunks of real estate and planting eggs. We feel for it. We remove it with a bit of bark and place it somewhere covered. It will die in pain unobserved. Grief is useless but persists. Love persists. Grief walks up and down the river, up and down. A hundred and fifty years ago children walked up and down the banks of this river, calling for their parents. You are useless and crude and should learn how to be useful. That is all that matters now. The present is over. You should learn to measure grief and think about the future. Instead, you sit beside white flowers, taking elegiac photos. Mourning that which is a symbol of mourning.

31.

The other day I thought of Emily's long dash as a straightened-out blackening ghost pipe, a line somewhere between life and death. To suspend the Breath / Is the most we can / Ignorant is it Life or Death / Nicely balancing. The white petticoats rimmed black and gathered professionally in a flower frenzy, one black stockinged leg thrust straight up and then out, tick-tocking back and forth with a da-da-dahdahdahdah. Your time is up, Victorianism! She can-caned with a young ruined face that people loved. I shouldn't. But I still think of this plant as a tragic heroine.

Jane Avril, skinny, "fed on flowers" holding the pose

and then dying, poor, in obscurity, of course. Jane the strange one, Jane the crazy. All the innocent whores of modern history jerk from lover to lover down narrow stone streets, turning childhood illness, a nervous tic, into dance. They take up with a woman, then a lecherous doctor, drag a boy-child along from one daddy to another. Hysterical elegance and soft melancholy all around, movement immortalized in Toulouse-Lautrec posters. Life and death, luck and misfortune, a hair-width between them. She once headlined at the Jardin de Paris, but ended in a poor house, sick with angina, dying in 1943. Last written words "I hate Hitler."Too loose. To Lose. The Trek.

But all that is behind me now. We sit at the side of the jogging path in folding chairs, just two weird old ladies, it looks like. J. says: Ghost Pipe's stems reminds me of an empty artery. Yuk, I say...

I just Can't. Can't

Look. The Summer is almost gone.

Jody Shenkarek: Final Blog Post

My time at Yorath House this summer has been such an incredible opportunity. Thea and I came to this place to work together and learn from each others experiences. We spent many hours walking the trails, sitting on the beaches, talking, listening trying new ideas and enjoying the grounds and the surrounding community. Time was a gift for us. Time to explore words, music, ideas and each others hearts and minds. We learned a lot about the area and the history of the people that have lived herein this place. I am thankful for my time and the interest it has sparked in me regarding place and people and history. We saw many native plants and learned the bends of the river. Met people from the area and found our favourite paths and places. The house welcomed us, and provided a place of comfort and creativity. We learned slowly how to intertwine our talents and come out with a project that highlights our individual and shared ideas.

Mornings with coffee and sunlight were my favourite time for writing lyrics and poetry. Thea taught me about form in writing and I taught her about making songs.

I have many hours of recordings made on the grounds of birds and sounds and our long talks and experimental songwriting projects. My photography and paintings done during that time have brought me great joy and I'm hoping to show them in the future.

Our beloved flower friend ghost pipe showed up (sadly not in the grounds of Yorath) but nonetheless we had the opportunity to sit with it for a week. I am forever grateful for this time as it shifted my world.

We will never truly leave Yorath now. We will come and walk and remember and keep building on the projects that we have started here. Ideas grow and reflection on our time will bring other new ideas as well. The chance to have an entire summer to be with a fellow artist and work together was heart opening. Connection and creativity take time. Thank you for this perfect summer.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog Post 5: Treaties and Settlement History

By Adriana A. Davies Yorath House Artist-in-Residence

A sketch of the buildings at Fort Edmonton done by Dr. A. Whiteside, 1880, City of Edmonton Archives EA-10-1178.

Sitting in Yorath House next to the North Saskatchewan River doing online research on homestead records, and also reading newspaper accounts from the end of the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth centuries, I come face-to-face with racism. The accounts are written from the settler perspective. The City of Edmonton Archives on its website has posted the following statement:

The City of Edmonton Archives (CoE A) has developed this statement regarding the language used in archival descriptions to meaningfully integrate equity and reconciliation work into the City’s archival practice. The changes reflect the staff’s on-going efforts to acknowledge known instances of discrimination that appear in archival records.

Archivists have been working on identifying and contextualizing problematic content, language and imagery found in our collections since 2017. This was partly in response to the Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) Commission’s Calls to Action, specifically those aimed at cultural and heritage institutions. Further work is on-going in alignment with the City of Edmonton’s commitments to inclusion and respect for diversity and the work of various groups in the City and, specifically, of the Anti-Racism Committee of City Council, as well as the Association of Canadian Archivists’ Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct.

While the statement deals with the language in historic documents, there is a larger issue. The Government of Canada was intent on colonizing traditional Indigenous lands. The territories that became Canada initially attracted the attention of the British and French because of the bounty of fur-bearing animals. The fur of beavers, in particular, was used to create felt for hat making. Fur trading companies were the first major commercial enterprises (Hudson’s Bay Company and North-West Company) and were followed by others to harvest other natural resources including fish and stands of timber.

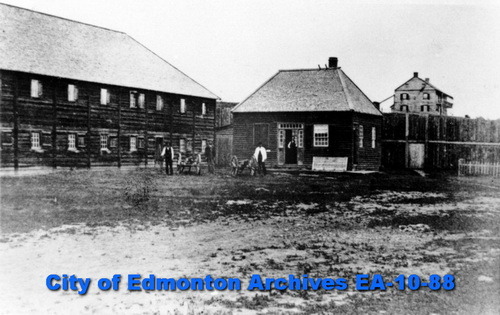

The interior of Fort Edmonton within the palisades showing the warehouse, Chief Factor’s House and Clerks’ quarters, 1894, City of Edmonton Archives EA-10-88.

With the signing of Treaty No. 6 on August 23, 1876 at Fort Carlton and on September 9, at Fort Pitt, the federal government was ready to unite the country “from sea to shining sea” through the building of a railway. The territory in question covered most of the central portions of what became, in 1905, the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta. The signatories were representatives of the Canadian Crown and the Cree, Chipewyan and Stoney nations.

Front and back of large medal presented to the Chiefs and councillors who signed treaties 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. It shows a relief portrait of Queen Victoria and the representative of the Crown shaking hands with one of the Chiefs. Libraries and Archives Canada, Accession number: 1971-205 NPC.

Treaty 6 was mid-way in the 11 numbered treaties; Treaties 6, 7 and 8 cover most of Alberta. At the Fort Carlton meeting, on the part of First Nations, Chief Mistawasis (Big Child) and Chief Ahtahkakoop (Star Blanket) represented the Carlton Cree. On the part of the Crown, principal negotiators were Alexander Morris, Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories; James McKay, a Metis fur trader, and Minister of Agriculture for Manitoba; and W. J. Christie, Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Chiefs at Fort Pitt trading with Hudson’s Bay Company representatives, autumn 1884, unknown photographer. L-R: Four Sky Thunder; Sky Bird (or King Bird), the third son of Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear); Moose (seated); Naposis; Mistahimaskwa; Angus McKay; Mr. Dufresne; Louis Goulet; Stanley Simpson; Constable G. W. Rowley (seated); Alex McDonald (in back); Corporal R. B. Sleigh; Mr. Edmund; and Henry Dufresne. There is a difference of opinion as to the names of the two corporals: some sources claim it is Corporal Sleigh and Billy Anderson, while others claim it is Patsy Carroll and H. A. Edmonds. Library and Archives Canada, Ernest Brown Fonds/e011303100-020_s1.

When Treaty negotiations began at Fort Pitt, on September 5, Cree Chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear) was away and therefore did not participate. Chief Weekaskookwasayin (Sweet Grass) led the discussions and appeared to accept that the terms of the Treaty would be beneficial; he was likely influenced by Chiefs Mistawasis and Ahtahkakoop. When Chief Mistahimaskwa returned, he was surprised that the other chiefs had not waited for him to return before signing. He had some important news to share: he had spoken to some of the signatories of previous Treaties and they had told him that they had been disappointed with the outcomes. Historian Hugh Dempsey has written that, if the Chief had been there, Treaty 6 may not have been signed. The entry in The Canadian Encyclopedia notes:

When Mistahimaskwa returned to Fort Pitt, he brought discouraging news with him from the Indigenous peoples on the prairies who had already signed Treaties 1 to 5: the treaties had not amounted to everything that the people had hoped. However, he was too late; the treaty had already been signed. Mistahimaskwa was frustrated and surprised that the other chiefs had not waited for him to return before concluding the negotiations. According to the notes of the commission’s secretary, M.G. Dickieson, Mistahimaskwa referred to the treaty as a dreaded “rope to be about my neck.” Mistahimaskwa was not referring to a literal hanging (which is what some government officials had believed), but to the loss of his and his people’s freedom, and Indigenous loss of control over land and resources. Dempsey argues that if Mistahimaskwa had been present at the negotiations, the treaty commissioners would have likely had a more difficult time acquiring Indigenous approval of Treaty 6. Mistahimaskwa was not the only chief who initially refused to sign the treaty. Chief Minahikosis (Little Pine) and other Cree leaders of the Saskatchewan District were also opposed to the terms, arguing that the treaty provided little protections for their people. Fearing starvation and unrest, many of the initially hesitant chiefs signed adhesions to the treaty in the years to come, including Minahikosis (who signed in July 1879) and Mistahimaskwa (who signed on 8 December 1882 at Fort Walsh).1

The “adhesions” involved the adding of signatories from other areas including Edmonton in 1877, Blackfoot Crossing in 1877, Sounding Lake in 1879, and Rocky Mountain House in 1944 and 1950. Treaty 6 encompasses 17 First Nations in central Alberta including the Dene Suliné, Cree, Nakota Sioux and Saulteaux peoples. The Edmonton adhesion was signed on August 21, 1877 on the land that would become the site of the Alberta Legislature. The site was a sacred gathering place for the Indigenous People of Alberta.

While the Treaties outline the rights, benefits and obligations to each other of the signing parties, there is no doubt that they were intended to enable a “land grab”: the Government of Canada wanted to open up the land for settlement. Indigenous People were to be confined to “reserves” and the remaining lands were to be made available. In 1869, Canada had purchased extensive parts of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company but the Company, because of its historic role in the fur trade, retained extensive tracts of land. When the federal government gave the Canadian Pacific Railway a monopoly to build the railway through the prairies they were also given extensive lands not only for laying of tracks and building of stations but also for establishing town sites and farms.

As sovereign peoples, why would Indigenous People in what became Alberta and Saskatchewan want to sign Treaties? They came to the negotiations in good faith expecting that the Government of Canada would protect their lands from outsiders including white settlers, surveyors and the Métis. By the mid-nineteenth century, buffalo herds had declined, as had deer and other big game, and they faced starvation; in addition, various smallpox epidemics were decimating their population and that is why they negotiated the “medicine chest” provision in Treaty 6; it was literally to be housed with the Indian agent. In addition, the Government promised to assist the signatories in farming initiatives by providing various types of equipment.

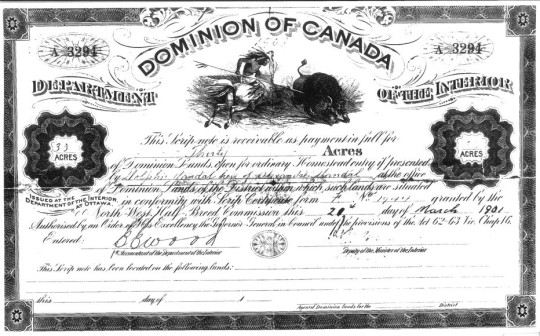

With respect to the Metis or “mixed blood” peoples who were the result of marriages between fur traders and Indigenous women, the Government of Canada devised Métis scrip, which was a one-time payment whether in money or land that “extinguished” the individual’s land rights. Whether the recipients understood this is open to question. The certificate or warrant was issued by the Department of the Interior and printed by the Canadian Bank Note Company. Money scrip came in $20, $80, $160 and $240 increments. Land scrip came in allotments of 80, 160 and 240 acre (32, 65 and 97 hectare) increments. This allowed the Canadian government to acquire Métis rights to the land. As Robert Houle writes:

To the detriment of the Métis, who at the time did not fully comprehend the foreign system, traders like McDougall and Secord began to venture away from mercantilism. Through continued exploitation of the Crown system, McDougall and Secord were able to become “Edmonton’s First Millionaire Teachers”. The Scrip system allowed those with resources to purchase a certificate for face value or perhaps a marginal increase, then redeem the certificate on behalf, sometimes through fraud, of the original holder and re-sell for profit. Once a sale was undertaken, unbeknownst to Métis, their claims and rights would be extinguished in the eyes of the Crown.2

Métis Scrip for 30 acres issued March 20, 1901. Image Courtesy of the City of Edmonton archives MS-46 File 38.

In order for the land to be settled, it needed to be surveyed. This work had begun in 1871 after Manitoba became a province, and the North-West Territories was established as a result of the purchase of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Dominion Land Survey covered about 800,000 square kilometres and began with Manitoba and then continued West. In 1869, the first meridian was chosen at 97°27′28.4″ west longitude. The survey excluded First Nations’ reserves and federal parks. The Hudson’s Bay received Section 8 and most of Section 26.

The surveys were done in three stages: 1871-1879: southern Manitoba and a little of Saskatchewan; 1880: small areas of Saskatchewan; and 1881: the largest survey that includes what became Alberta. There was a sense of urgency about finishing the survey because the Government of Canada feared US encroachment into Canada. Over 27 million quarter sections were surveyed by 1883; maps and plans were given to the provinces. Townships were composed of 36 sections, and sections comprised 4 quarter sections or 16 subdivisions.

After Hudson’s Bay Company railway right of ways and school sections were carved out, the remainder became available for homesteads. The federal and provincial governments and municipalities advertised land availability for settlement. A homesteader had to pay a $10 fee to register a quarter-section and, within a term of three years, had to cultivate 30 acres (12 hectares) and build a house to gain title to the land. The bulk of prairie settlement occurred in the period 1885 to 1914.

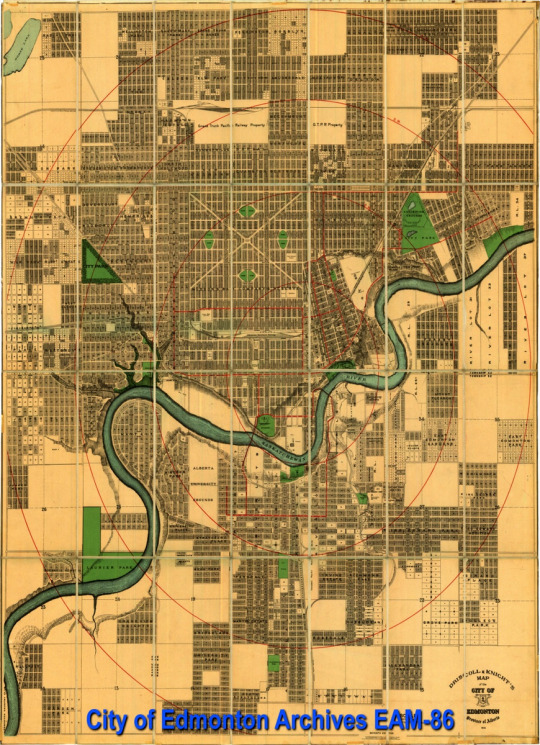

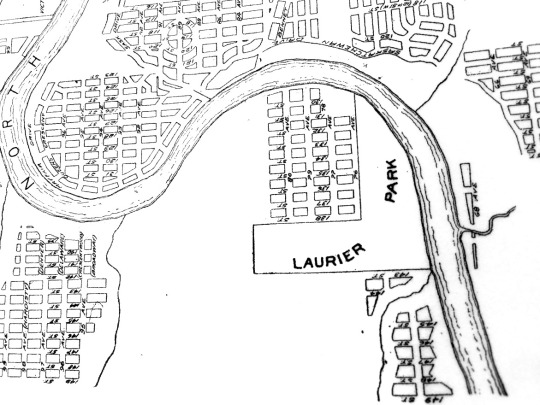

With respect to the surveying of the land at Fort Edmonton, W. F. King did an initial survey for the Government of Canada in 1878. The formal survey was done in 1882 and adhered to the river lot pattern that the largely Métis population had established. This was based on the system used in Quebec. Because many of the Métis at Fort Edmonton and St. Albert had begun to settle the land and their small farms and landholdings adhered to the river lot system, this was grandfathered in.

The Hudson’s Bay Company had an extensive tract of land to the West of the downtown centred on Jasper Avenue (the Hudson’s Bay Reserve). The survey established 44 lots covering both sides of the North Saskatchewan River. These were East of the HBC reserve lands. By and large, these were Métis owned with the remainder purchased from the Company by current and former employees. The lots on the northern side of the River were even-numbered and the lots on the south side were odd-numbered. Among the former HBC employees were Malcom Groat, Colin Fraser, John Sinclair, Donald McLeod, James and William Rowland, Kenneth Macdonald, James Kirkness, John Fraser and James and George Gullion. Métis homesteaders included Joseph McDonald (River Lot 11), Laurent Garneau (River Lot 7), some of whom had also worked for the Company.3 These lots were by and large farmland until the communities of Edmonton and Strathcona began to expand quickly becoming towns and cities in the period from 1890 to 1914 when a worldwide economic recession and the First World War put an end to development.

Connor Thompson in “Edmonton’s River Lots: A Layer in Our History,” writes:

As the area’s fur trade was winding down, farming began to take on a greater importance in the lives of the people around Fort Edmonton. Many began staking claims to land in the Fort’s immediate vicinity, farming in a river lot fashion. A staple of Métis culture, this style of farming allowed for access to the river, wooded areas, cultivated land, and provided space for hay lands as well. While a rough (and unapproved) survey was undertaken by government surveyor W. F. King 1878, a more thorough government-approved survey in 1882 formalized the division of the land in terms of a river lot pattern, which is what the predominantly Métis population in the area at the time desired. The survey created 44 large lots across the banks of the North Saskatchewan, most of which stretched east of the Hudson’s Bay Company reserve lands. In many ways, the early history of these river lots is a history of the Métis and their kinship networks – marriage between the area’s families was common, as were friendship and support systems.

Other south side families faced struggles relating to their Indigenous identities, especially with the pressures of Métis scrip and the 1885 rebellion – Métis scrip was a one-time payment of either money or land that, in the eyes of the Canadian government, extinguished the person’s Indigenous land rights. Scrip was notorious for its convoluted process and unethical nature. Many families on these south-side river lot farms, including the family of William Meaver on River Lot 15 (bounded by present-day 99th St. to 101 St.), Charles Gauthier and his son on River Lot 17 south (99th St. and Mill Creek Ravine), George Donald and Betsy Brass of River Lot 21 (91st to 95th St., in the present-day Bonnie Doon neighborhood), took scrip. Some of the families that were members of the Papaschase band either took scrip (as Brass herself, who was a woman of mixed Cree/Saulteaux ancestry did), or joined the Enoch band, as William Ward’s family (of River Lot 13) did. As settlement increased, many Métis families of this period would leave to places such as St. Paul des Métis, St. Albert, Tofield, and Cooking Lake.

As the largely British towns of Edmonton and Strathcona grew, the Indigenous origins of the land were erased and the rights of Indigenous Peoples violated.

Edmonton Settlement showing the river lots, ca. 1882. City of Edmonton Archives EAM-85.

Interpreting History

In August 1951, my Mother Estera, older sister Rosa and my brother Giuseppe and I joined our Father, Raffaele Albi in Edmonton. He had left Italy in 1949 and made his way to Edmonton and begun work for an Italian-owned company, New West Construction. The company was helping to finish the Imperial Oil Refinery in Strathcona. In 1953, my parents purchased an old house on 127 Street and 109A Avenue in the Westmount area. That September, we went to school at St. Andrew’s Elementary School across from the Charles Camsell Hospital. That is when I encountered racism personally: as a dark and thin southern-Italian kid, I became the target of “half-breed” jokes. I knew who these people were because daily I watched the dark-skinned children looking at me through the chain-link fence that surrounded the Hospital. They looked sad and I felt that they were jealous watching us play our care-free games in the school yard. There were some Métis children in my school and I quickly made friends with members of the L’Hirondelle, Mercier and Majeau families not realizing that for some of my school mates this was not done.

It came as a surprise to me that Italians were considered a “visible minority” and therefore the butt of jokes, many about the Mafia, DPs, Wops or other pejorative terms. I was thus sensitized to “being different.” When I was in junior high, I decided that I wanted to be a journalist and, in 1962, became a student at the University of Alberta with an English major and French minor. I volunteered with the student newspaper, The Gateway, and the summer of 1964 was a student intern at The Edmonton Journal.

Two traumatic experiences occurred that summer that helped to shape my thinking and influenced my life and career. A friendly journalist told me that there was a bet on at the Greenbriar Lounge, where the largely male staff went to drink, as to who would get me into bed (nobody did!). The other occurred when on weekend duty I was assigned to cover a story on a northern reserve. Weekend duty was assigned to younger staff and the carrot was that you got to do a photo essay for the Sunday newspaper. A young photographer and I drove up to the reserve and I remember arriving in a tiny, tiny community (it wasn’t large enough to be described as a town) and going to what looked like the community hall. Dave and I entered an extremely smoky room where all the men were talking animatedly. When we introduced ourselves, they were extremely kind and I began the interviews. I discovered that they were discussing Treaty rights and that the Government of Canada was not honouring these. I was captivated. On our return to the Journal offices late that evening (Saturday), I wrote the article telling their story. I was delighted with the two-page spread that included David’s photographs of the Chiefs and Elders. The following Thursday at the weekly Editorial meeting, Editor Andrew Snaddon tore strips off me for having “lost my objectivity” and only told the “Indian” side of the story. From that day forward, I knew that I wanted to continue to tell those stories.

The first opportunity came in January 1987 when I started work as the executive director of the Alberta Museums Association. I took a call in the first week from someone wanting to know what “ICOM Resolution 11” was. I didn’t know so I called the Canadian Museums Association and learned that the International Council of Museums at its General Assembly in 1986 in Buenos Aires, Argentina had passed a resolution that was to guide museums in dealing with living Indigenous communities. It stated:

Resolution No. 11: Participation of Ethnic Groups in Museum Activities

Whereas there are increasing concerns on the part of ethnic groups regarding the ways in which they and their cultures are portrayed in museum exhibitions and programmes, The 15th General Assembly of ICOM, meeting in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 4 November 1986, Recommends that: 1. Museums which are engaged in activities relating to living ethnic groups, should, whenever possible, consult with the appropriate members of those groups, and 2. Such museums should avoid using ethnic materials in any way which might be detrimental to the group that produced them; their usage should be in keeping with the spirit of the ICOM Code of Professional Ethics, with particular reference to paragraphs 2.8 and 6.7.

The resolution enshrined consultation on all Indigenous exhibits and programs that has become a practice with Canadian museums. When I called back and gave the mystery caller this information, I asked who they represented and learned that it was the Lubicon Cree. This northern Alberta First Nation had been left out of Treaty 8 negotiations. They had filed a claim with the federal government as early as 1933, for their own reserve but nothing had been done to resolve the matter. Pressures on their traditional way of life resulting from the number of oil companies drilling on the contested territory had accelerated their need for a settlement. Under a new, young Chief, Bernard Ominayak, the cause received renewed impetus and he sought the help of professionals.

American human rights activist Fred Lennarson became his chief advisor in 1979. His consulting company, Mirmir Corporation, had already done work for the Indian Association of Alberta (under Harold Cardinal). Ominayak and Lennarson aimed to get a $1 billion settlement from the federal government and, to do this, organized an aggressive letter writing and media campaign. By 1983, they were mailing information about the land claim dispute to over 600 organizations and individuals around the world and had been successful in obtaining the support of the World Council of Churches and the European Parliament. Knowing that they would need the support of Indigenous organizations, they had extensive meetings and, among the first to come on board were the Assembly of First Nations, the Indian Association of Alberta, the Métis Association of Alberta and the Grand Council of Quebec Cree.

Subsequently, when the Glenbow Museum launched its exhibit, curated by Julia Harrison, titled “The Spirits Sings,” as part of the Calgary Winter Olympics in 1988, there were protestors there indicating the museum had violated ICOM Resolution 11 and also attacking the display of “False Face” sacred masks that were on display. In fact, Harrison had had an Indigenous advisory committee and the masks had previously been on display in Ontario museums as well as in the Canadian Embassy in London, England, without objections. This event galvanized museum personnel to undertake some serious reflection on the way in which they represented Indigenous history and artifacts.

The Canadian Museums Association with the Assembly of First Nations undertook the Task Force on Museums and First Peoples and I was delighted to take part in this work which was led on the museum side by Morris Flewwelling, the CMA President at the time. With the support of the Board of the Alberta Museums Association, we created three symposia held in 1988, 1989 and 1990 to address the relationship between museums and First Peoples, repatriation of ceremonial and sacred objects, and the topic “Re-inventing the Museum in Native Terms.” For this last, I invited representatives from the Ak-Chin Eco-Museum in Arizona. The community, which was established in 1912 as a reservation, was plagued by poverty and scarcity of resources until it declared itself an “ecomuseum” and focused on preservation of its language and culture to promote economic development.

As a result of information gathered through our symposia and meetings with representatives from various Indigenous communities (both within and outside of Alberta), I was delighted to provide advice to a number of Indigenous museum projects. I could not have done this work without the help of some prominent individuals, who championed Indigenous history and were chiefs, elders and ceremonialists. The most important were Russell Wright and wife Julia; Leo Pretty Young Man Senior and wife Alma; and Reg Crowshoe and wife Rose. They participated willingly in the Alberta Museums Association Indigenous symposia and in other planning and advisory work.

Russell struggled to maintain a museum in the old Residential School at Blackfoot Crossing on the Bow River East of Calgary. In the 1970s, he had helped to develop a Blackfoot studies program for the Old Sun College on the reserve. He was troubled by the high rate of student suicides on the reserve and firmly believed that it was only through the renewal of the Blackfoot culture and language that this trend could be halted. I did my best in advising him as to how to go about fundraising for a new museum, which had been his dream since the 1977 centenary celebrations of the signing of Treaty 7 (Prince Charles attended the ceremonies). With Leo Pretty Young Man Senior and wife Alma as well as other Elders and their wives, he envisioned an appropriate building that would house cultural artifacts and function as an education centre.

The Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park is a legacy to their vision. In 1989, six square kilometres of land were set aside but funding would not become available until 2003 to initiate construction. Neither Russell nor Leo lived to see the museum, which was completed in 2007. The iconic teepee-like structure was designed by architect Ron Goodfellow. The Buffalo Nations group, headed by Leo, took over the old Luxton Museum in Banff and I was delighted to attend planning meetings to assist them to obtain grants to develop new exhibits, care for collections and undertake necessary restoration work to the building. The Buffalo Nations Luxton Museum became a popular attraction in Banff.

The vista from the rear windows of the Blackfoot Crossing Interpretive Centre, which is a National Historic Site of Canada located near Cluny, Alberta. The area in southern Alberta is significant as both a geographic and cultural centre of Blackfoot territory and includes the grassy flood plain of the Bow River Valley. It was the location where Treaty No. 7 was signed in 1877 by representatives of the the Siksika (Blackfoot), Pekuni (Peigan), Kainai (Blood), Nakoda (Stoney) and Tsuu T'ina (Sarcee) First Nations. They surrendered their rights to 50,000 square miles of territory. Numerous archaeological resources and historical features are located there including the grave of Chief Isapo-Muxika (Crowfoot). Photographer: Adriana A. Davies.

Another of my Indigenous mentors was Reg Crowshoe, a former chief of the Piikani Blackfoot First Nation, who had worked as an RCMP officer. He assisted the Historic Sites Service on various projects and generously shared his traditional knowledge with students at the universities of Lethbridge and Calgary. He founded the Old Man River Cultural Society and followed in the footsteps of his father, Joe Crow Shoe Senior. Joe was an Elder and Bundle Keeper and ran Sun Dances; he renewed the Brave Dog and Chickadee Societies. Father and son collaborated with Historic Sites Service, Government of Alberta, and were instrumental in the building of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump Interpretive Centre near Fort Macleod, which showcases and interprets Blackfoot culture. It opened in 1987 and is run by Alberta Culture. It is a Canadian national historic site and UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Gerald Conaty, Julia Harrison’s successor at Glenbow as Curator of Ethnology, was an invaluable resource and took me on a number of field trips to Treaty Seven areas to meet with Elders and ceremonialists. Beginning in 1990, he helped the Glenbow to develop and implement repatriation policies with respect to sacred objects. The initial work was done by Hugh Dempsey, long-time Glenbow curator and sometime Acting Director, who had extensive relationships in the Indigenous community going back to his involvement with the Indian Association of Alberta. He married Pauline Gladstone, the daughter of James Gladstone, the first status Indian appointed to the Canadian Senate. In mid-1990, Dempsey with Board approval loaned a medicine bundle to Dan Weasel Moccasin for a ceremony thereby setting a precedent. The bundle was returned.

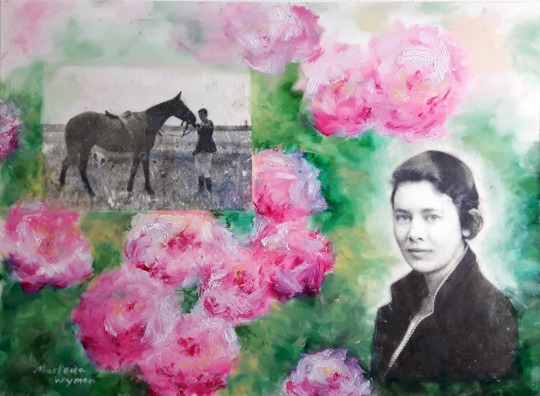

Towards the end of my tenure as Executive Director of the Alberta Museums Association around 1998-1999, I was involved in an interesting project titled “Lost Identities” put together by Historic Sites Service Museums Advisor Eric Waterton; Provincial Archives of Alberta Archivist, Marlena Wyman; Pat Myers, historian with the Provincial Museum of Alberta; and Shirley Bruised Head, the Education Officer at the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump Interpretive Centre. We wanted to develop a photographic exhibit for the Centre and Marlena scanned their collection for a cross-section of photos representing Treaty 7 people. When the committee reviewed them, we noticed that archival photographs frequently had the label “unknown Indian.” We decided to focus on those photographs for the exhibit and selected about 30 photographs that were enlarged and framed. They were hung in an exhibit room at the Interpretive Centre and next to each was a copy of the photograph with blank outlines of the people. Visitors to the exhibit were encouraged to identify anyone they knew.

I remember well the exhibit launch organized by Shirley. There was a feast for the Elders and after the blessings were finished, the exhibit was introduced and the participants began to walk around looking at each photograph carefully. For some time, there was absolute silence in the room followed by a kind of buzzing noise as they began to talk to each other and point at people they knew.

Shirley was an extraordinary woman (Sacred Hill Woman "Naatoyiitomakii"), who died too soon in 2012. She was a member of the Piikani Nation and she and her twin sister Barbara were born on the reserve on February 19, 1951 to Irene and Joe Scott. Her parents ranched. After their early death, the children were separated and she grew up in her Uncle’s home in Siksika and then moved to Edmonton to attend St. Joseph’s High School. She married Norbert Bruised Head and supported his rodeo career and worked for Native Counseling Services in Lethbridge. She obtained a BA degree from the University of Lethbridge and, later, a Master’s in Education. She was a ceremonialist and was a pipe owner; she assisted in the beaver bundle ceremony.

A committee of former presidents of the Alberta Museums Association met for several years to discuss how to make the Association more financially independent and how to promote museums more effectively. The result of this was the creation of the Heritage Community Foundation in summer 1999 with the mandate “to link people with heritage through discovery and learning.” At that time, I was a member of the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN) advisory committee and involved in a “Museums and the Web” study. I quickly became convinced that the World Wide Web offered enormous opportunities for promoting heritage. The Foundation obtained funding to create our first website – a kind of overview of Alberta’s heritage and museums – and this gave us our direction.

I pitched to the Board that the primary focus of the Foundation should become the development of web content drawing on museum and archival collections and, furthermore, that we should create the “Alberta Online Encyclopedia.” They wholeheartedly endorsed this and www.albertasource.ca was born. Luck and, I guess, timing was on our side. In March 2001, CHIN launched the Virtual Museum of Canada, which had a grants program, and I knew which project to bring forward. The Spirit of the Peace Museum Network had developed a travelling exhibit titled “The Making of Treaty 8 in Canada’s Northwest.” It was rich in artifacts, documents and records. I approached Fran Moore, the Chair of the network, and asked whether they would partner with us and the answer back was an unequivocal, “Yes!” It was all systems go. I developed the grant application, which was jointly submitted, and we obtained funding to hire some project staff and a firm of web developers. In the end, content and images for the bilingual website were contributed by not only the Museums of the Peace but also, the Glenbow, Provincial Museum of Alberta, Treaty 8 First Nations and the Lobstick Journal. I remember going up North to test the site with Elders and seeing the excitement on their faces when they began to identify relatives in the archival photos. The website was launched in 2002 and CHIN was thrilled with it.

In 2004, we designed a project to celebrate Alberta’s centenary: expansion of the websites in order to cover Alberta’s social, natural, cultural, scientific and technological heritage. Albertasource.ca, the Alberta Online Encyclopedia, received a $1 million Centennial Legacy grant. On September 29, 2005, the Foundation launched the Encyclopedia – the Province’s intellectual legacy project – at the Edmonton Space and Science Centre to a supportive crowd including children from neighbourhood schools.

After development of the Treaty 8 website, we moved all technical development in-house because we found that we could better control quality as well as guaranteeing that websites were completed on time. This was crucial because in some instances the majority of funding was received on project completion. Of our first four interns, two stayed on with us for a number of years and became permanent staff. Dulcie Meatheringham, a young Métis woman from Northern Alberta, became our first webmaster. Over the 10-year life of the Foundation, we had over 450 interns, most for three-month internships.

There are certain groupings of websites that the Trustees and I take particular pride in; among them are the over 30 websites that are either wholly or partly devoted to Indigenous content. All involved partnerships with Treaty organizations and the Métis Nation of Alberta. These include sites on individual treaties as well as Alberta’s Metis Heritage, People of the Boreal Forest and Elders’ Voices. The last included content from the “Ten Grandmothers Project” undertaken by Linda Many Guns of the Nii Touii Knowledge and Learning Centre; the Centenarians, a nine-minute video production celebrating Indigenous women resulting from a partnership between Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, the Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women and EnCana Energy. We also undertook some oral histories of Métis veterans. Thirteen Edukits draw on the content of the various websites and provide teacher and student resources directly related to the K-12 curriculum. They are: Alex Decoteau; Origin and Settlement; First Nations Contributions; Culture and Meaning; Language and Culture; Spirituality and Creation; Health and Wellness; Leadership; Physical Education, Sports and Recreation; Math: Elementary; Science; and Carving Faces: People of the Boreal Forest.

I am proud of the fact that we created three Indigenous internship programs in partnership with the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology that trained young people in web design. We obtained some funding from Western Economic Diversification in support of the project. We had not only interns who specialized in web design but also graduates in history who wrote site content. They worked on both Indigenous and non-Indigenous websites. Some have made careers in this area. On June 30, 2009, the Heritage Community Foundation gifted the Alberta Online Encyclopedia to the University of Alberta so that it could make available the websites in perpetuity.

What people in the museum and heritage field accomplished in partnership with Indigenous Peoples and institutions from 1987 to the present is only a beginning. As we move into the era of the “decolonizing of museums,” a whole new generation of Shirley Bruised Heads, Linda Many Guns and others are needed. It’s good to see these new voices, talents and abilities emerging and tackling recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I was privileged to be able to attend the last day of the Commission hearings held in Edmonton from March 27-30, 2014 at the Shaw Conference Centre. I eagerly awaited the release of the report in June 2015 and have tracked how heritage and arts organizations have begun to implement its recommendations.

The last physical event that I attended before Covid was the Edmonton Heritage Council’s Symposium titled “Reconciliation and Resurgence: Heritage Practice in Post-TRC Edmonton.” Their website notes:

On March 3 and 4, 2020, 150 people came together at La Cité Francophone to discuss Reconciliation and Resurgence in post Truth and Reconciliation Commission Edmonton. Members of the Indigenous community, Edmonton’s heritage sector, academics, not-for-profit workers, students, public sector workers, and members of the public, came together to learn how each of us can contribute to reconciliation work in the heritage community. Those in attendance were encouraged to consider and examine the ways in which Indigenous peoples and heritage have been and continue to be excluded or marginalized within heritage institutions and narratives. We asked attendees to think critically about their own roles in this pattern of erasure, and to consider a way forward where Indigenous voices are lifted up, where Indigenous heritage is told by Indigenous people, and how historical erasure and marginalization has contributed to the current realities of systemic racism.

The Edmonton Heritage Council was advised by Elders and community members from First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities throughout the planning process. Each day of the symposium began in ceremony with smudging and a prayer.4

From the 15 - 18 of March, 2021, I attended a virtual symposium organized by the International Committee for Museology of the International Council of Museums, which is part of UNESCO. I have been a member for over 30 years and served on the ICOM Canada Board. The conference was to take place in Montreal but Covid turned it to an online encounter. The topic was “Decolonizing Museology: Museums, Mixing and Myths of Origin.” The focus was as follows:

The purpose of the ICOFOM Annual Meeting is to create an international forum for a high level discussion on a museological topic. Usually, the topic is different each year, but sometimes it is analyzed over a three year period.

Approaches to museology vary widely around the world, for example, using museums to make statements about nationalism is given priority in some countries. In others, conservation and the exhibition of highly aestheticized, non-controversial artefacts, are regarded as the primary roles for museums. By contrast, in other nations, the development of “histories from below” or the salvaging of the histories of the lives of people who were regarded as having no value, is now a primary museological focus. The wide international variety of museologies means that the annual meeting has fundamental importance for the expression and recording of these differences.

I am looking forward to seeing the next era of history writing and interpretation.

The Dome

Standing on the Dome, Dawson City, You can see the fingers of river stretching towards the Bering Strait. Rotating through 360 degrees, The various landscapes open up to you.

The place is magical – Both in its natural and human elements. The light, in this Land of the Midnight Sun, Is like no other.

It brings out the artist in me. I want to paint word pictures— Of rocks, trees, sky and water, A haze smudging the distant mountains into the cloud cover.

Time present and time past merge. Geological time has shaped rock formations; Glaciation normally softens these, but not in this valley; And vegetation adds the finishing touches.

Up here, the town site is miniscule— The works of man diminished by the works of nature. The reverse of what is seen at the valley floor, Where churned-up gravels dominate.

There, the striations of gold-dredging, Form giant worm leavings— The only industrial operation that almost looks natural— The regularity and symmetry of gravel ridges resembling a moraine.

Dredge no. 4 now sits tethered. Its work of creating new landforms ended. Its appetite for muskeg stilled by economic forces, The devaluing of the sovereign metal.

And what of those changed lives? The preserved buildings are a memorial to them. Window displays tell of events, And objects are tangible evidence.

You can identify buildings and streets, Forming the background of archival photos. But, what you don’t get are the raw emotions— The greed, flimflam, pain and loss.

When it all went bust, Those gold gypsies walked away, Leaving their possessions behind, like empty cocoons— The residue of a transitory, disposable society.

We now want to put those lives on show, In restored and recreated buildings, For the entertainment of bus-tour travellers. How can we do it and pay homage to their humanity?

In the window in the madam’s house, I see photos—a woman in a fashionable, fifties swing coat with a dog, Also a family portrait with an Oriental man and little boy. Was it greed that brought this genteel Parisienne to the Yukon?

The priests and religious are also there. Ministering to their flocks brought hardship and even death. Did they feel it was worth it, in the end, When facing their Maker?

The substantial buildings survive, Set down for a future territorial capital, Their neoclassical tin facades, Bravely face river and forest.

Those gold hustlers must have had other qualities to counter the greed. Some must have come to stay— To put down roots, And leave a legacy for their children.

What about the Native People— Skookum Jim and Tagish Charlie? Cast as bit players in this colonial saga, Their impassive countenances don’t say much.

We need the Han Centre to place the Gold Follies in a larger context. Indigenous time and values— Centuries in the making— Providing a silent commentary on white mayfly lives.

Did they know that it would be heritage tourism — The “gold rush” of the early 20th century— That would provide the window on their lives, The measure of their success whether they struck it rich or not.

The aged prospector in the CBC documentary, Repeats the eternal round of digging into the earth, Like an Ancient Mariner marooned in mid-century, A generation away from when the action left Dawson.

Museums have serious powers. Unearthing the past has its responsibilities. Each day, we make and break reputations— Validate one person’s struggle, while ignoring another’s.

We have become dream merchants. A rootless civilization finally coming to its senses, Needing the bone, twigs, cloth and feathers Of heritage “shamans” to reconstruct the world.

Is a code of professional ethics enough? Or do we acknowledge our powers— To create the symbols and icons for the next generation, And turn job into vocation?

Whitehorse, June 3, 1998, Canadian Museums Association conference

________________________________________________

1 Michelle Filice, “Treaty 6,” The Canadian Encyclopedia Online, URL: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/treaty-6, retrieved January 15, 2022. See also Harold Cardinal and Walter Hildebrand, Treaty Elders of Saskatchewan: Our Dream is that Our Peoples Will One Day Be Clearly Recognized As Nations (2000).

2 Robert Henry Houle, “Richard Secord and Métis Scrip Speculation,” June 28, 2016, Edmonton Heritage Council, Edmonton City as Museum Project, URL: https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2016/06/28/richard-henry-secord-and-metis-scrip-speculation/

3 See Connor Thompson, “Edmonton’s River Lots: A Layer in Our History,” September 9, 2020, URL: https://www.google.com/search?q=Edmonton%27s+River+Lots&ei=QBraYfTfC5mU0PEPuq-0oAk&ved=0ahUKEwj0_7fYo6P1AhUZCjQIHboXDZQQ4dUDCA4&oq=Edmonton%27s+River+Lots&gs_lcp=Cgdnd3Mtd2l6EAxKBAhBGABKBAhGGABQAFgAYABoAHAAeACAAQCIAQCSAQCYAQA&sclient=gws-wiz

4 See “Reconciliation and Resurgence: A Year Later,” Edmonton Heritage Council, URL: https://edmontonheritage.ca/blog/2021/03/04/reconciliation-and-resurgence-one-year-later/, retrieved January 18, 2022.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

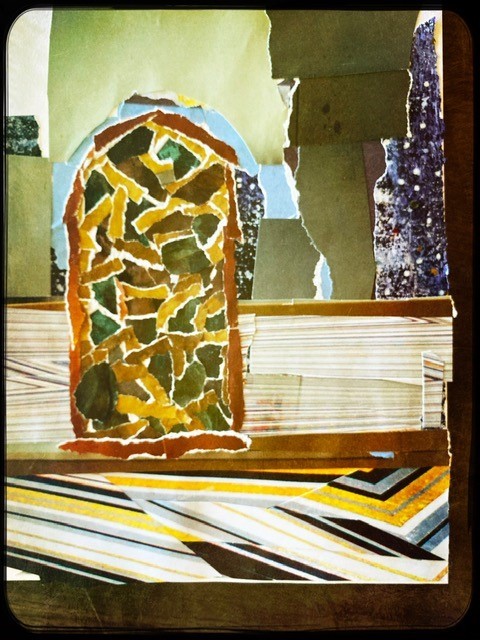

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog 6: Marion Nicoll as Muse

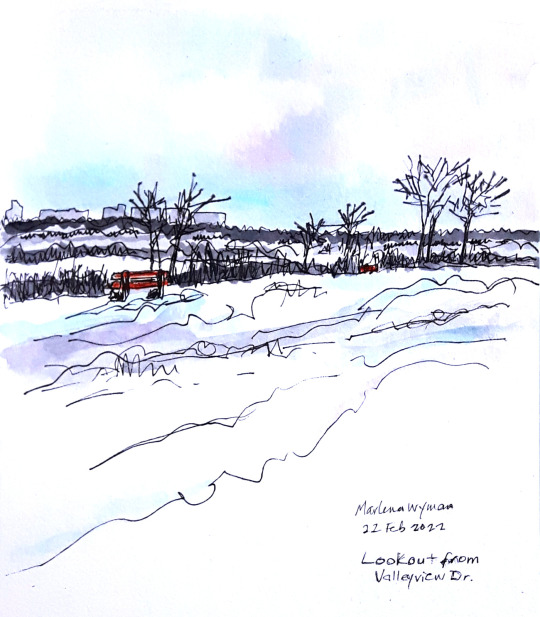

by Marlena Wyman, February 22, 2022 Artist-in-Residence at Yorath House

The walls of Yorath House are graced with inspiring artworks by major Alberta artists, on loan from the Alberta Foundation for the Arts. The works were carefully curated by AFA’s Art Collections Consultant Gail Lint to complement the modernist style of the house, built in 1949. Mid-century prints, drawings and paintings are on exhibit in the house by eight significant Alberta artists: Marion Nicoll, Thelma Manarey, John Snow, Stanford Perrot, George Wood, J.K. Esler, E.J. Ferguson, and Kenneth Samuelson.

Background about these artworks can be viewed on the AFA’s website.

I was especially pleased to see four artworks by Marion Mackay Nicoll (1909 – 1985). She was on the cutting edge of Alberta’s early abstract art movement, and her work paved the way for the acceptance of female artists in a male-dominated art scene. In 1933 she became the first woman instructor at the Provincial Institute of Technology and Art.

Two of her works are just down the hall from our studio at the second floor staircase landing. They are fittingly titled January and February, which are the months of our artists’ residency. Nicoll has provided her muse to me, and these two prints were a beginning point. In my walks through the winter landscape near Yorath House, I became aware of forms that echoed those in Nicoll’s January and February prints, and my intent is for my interpretations to honour her two works.

After Marion Nicoll’s February by Marlena Wyman.

One of the thin central lines in Nicoll’s February is a red-brown, which I interpreted as the wooden exterior of Yorath House. When looking at the house from the river side, there is a large expanse of open land leading up to the house which had been the Yorath family’s lawn and flower gardens. Trees surround the house on all sides.

February by Marion Nicoll. Courtesy Glenbow Museum. Collection of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts #1981.155.244

What I have noticed about being at Yorath House in January and February is that the cool winter whites and blues frame the warm wooden tones of the house exterior more so than in any other season. My outdoor palette has been in contrast to the brown and golden tones of the house interior used in my drawings from our first blog post.

After Marion Nicoll’s January by Marlena Wyman.

January by Marion Nicoll. Courtesy Glenbow Museum. Collection of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts #1973.004.004.1_2

Much of Nicoll’s entire body of work expresses her love of Alberta’s seasons and weather, and her elegant perception of prairie space is evident.

My watercolour pans in the blue and grey tones have been getting a real workout with all of the outdoor artworks that I have been creating. Prairie Farm, another of Nicoll’s winter paintings (not hanging at Yorath) is a subject that is more connected to the setting of the Yorath House than might be initially thought. There were farms in the river valley where Yorath House is situated and what is now parkland had been the site of chicken, turkey and mink farms along with other agricultural activities.

After Marion Nicoll’s Prairie Farm by Marlena Wyman.

Prairie Farm by Marion Nicoll. Courtesy Glenbow Museum. Collection of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts #1973.004.006.1_2

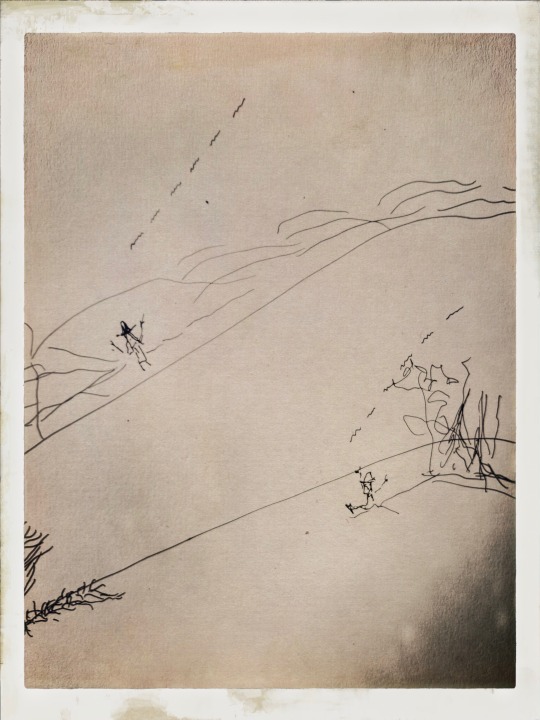

Nicoll also worked in automatic drawing – something that I have not attempted. It is not easy to enter into that level of the subconscious mind, and I admire her for that and her other departures from what were the strong British watercolour landscape traditions taught by A. C. Leighton in her early art school training (1928-1930) at Calgary’s Provincial Institute of Technology & Art (later the Alberta College of Art). Although she had a lifelong gratitude for what Leighton taught her, she felt that her true identity as an artist came about after she learned automatism from Jock Macdonald (1946), and then made abstract her genre.

I have to admit that at times my paint test sheets actually turn out better than my drawings/paintings. That was the case here with the test sheet that I used when I was painting a watercolour of the exterior of Yorath House. I scrapped the “painting” but I liked the test sheet. It is nothing more than random blobs and brush strokes to see whether the colours were what I wanted. My test sheets are not conscious acts of art, but I have been keeping some when I look at them at the end of the day and say, “Hey I like that.” I may do something with them one day. In this case I think that my test sheet was guided by the muse of Marion Nicoll. They are as close to being automatic drawings as I have come.

Marlena Wyman paint test sheet

Nicoll worked in sketchbooks as well, often using the continuous line drawing technique. I sketch regularly with my Urban Sketchers Edmonton group, and I have a tendency for the line in my sketches to become tight, so making a continuous line drawing from time to time helps me to loosen up.

Continuous line drawing of my artist-in-residence partner, writer Adriana Davies.

Figure sketch continuous line drawing by Marion Nicoll. Courtesy Glenbow Museum. Collection of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts #1981.155.216.K

Marion Nicoll, Annora Brown, Ella May Walker and others produced the 1935 exhibit Women Sketch Hunters of Alberta as a reaction to the almost completely male membership of the Alberta Society of Artists at the time, and the preferential attention given to male artists. Women artists played an integral role in Alberta’s art scene, although both it and the Canadian art scenes were mainly a boys club at that time and for the next several decades.

Nicoll’s abstract art practice began in 1957 at Emma Lake, SK and then at the Arts Students League in New York (1958-59) where she studied with Will Barnet at both locations. It may seem unusual for me to have an abstract artist as muse since I do not work in that genre - I also love the work of American artist Joan Mitchell – but the light of inspiration enters through many windows and it is not always direct.

Nicoll is the most recognized female artist in the development of abstract art in Alberta, and her legacy of Canadian postwar modernism remains at the modernist-designed Yorath House.

Continuous line drawing of Yorath House by Marlena Wyman.

________________________________________________________

References:

Townshend, Nancy. A History of Art in Alberta. Calgary: Bayeux Arts Inc., 2005.

Laviolette, Mary-Beth. Alberta Mistresses of the Modern 1935-1975. Edmonton: Art Gallery of Alberta, 2012.

Zimon, Kathy. Alberta Society of Artists - The First Seventy Years. Calgary: The University of Calgary Press, 2000.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog Post 4: Winter

Words by Adriana A. Davies, Jan 21, 2022 Artwork by Marlena Wyman Jan 22 – Feb 2, 2022 Artists-in-Residence at Yorath House

North Saskatchewan River looking north from below Yorath House

Since time immemorial, human beings have been afraid of ice and snow. Indigenous Peoples in the Northern Hemisphere donned warm clothing made of the skins of fur-bearing animals and used snowshoes to get around. In Northern Europe, the Swedes invented cross country and downhill skiing, saunas and a honey liquor called mead, and that began to change things.

Being born in warm, southern Italy, my first Canadian winter after immigration with my family as a child was a huge shock. My parents took my siblings – sister Rosa and brother Giuseppe – and I to the old Army & Navy store downtown (that’s where most immigrants first shopped) and bought us our first winter gear. Rosa got a wool coat and ugly brown long stockings; Giuseppe and I got one-piece snowsuits with long zippers that inevitably jammed. My suit was red. Against all instructions not to do so, I licked an icy lamp post and jumped on the ice on top of puddles and broke through, and had to walk home with water-filled boots.

I quickly learned to respect winter and fear the cold. I admit it: I am a wimp who prefers to look at winter through a picture window. Yorath House has plenty of those and during the cold spell this January, it is a wonderful place to be. I wrote my first poem there watching the snow fall but I’ve been writing winter poetry for a long time.

The dualities of winter – cold that can kill and also the extreme beauty of frozen landscapes – have captivated me. I remember reading Anglo Saxon poems at the University of Alberta and the later Icelandic sagas that told of life in Northern climes. One account described it being so cold that words froze in the air as people spoke and, when spring came and they defrosted, the air was full of a cacophony of sound. Here are some winter poems.

Snow

In the North Saskatchewan River Valley, Snow has formed A white crust That cracks And settles In footprint shapes.

Underneath, The brown leaves Are undergoing A transformation— Becoming New soil. The Yorath House grounds Are over-run by dog walkers on this winter day. The dogs run ahead Evading their owners, On the track of wildlife. They disappear For minutes on end And I am left alone wrapped in silence. It is almost too cold To be walking outdoors. Fingers and toes Chilled to a dull ache. Ice forms around eyelids And scarf covering my mouth. Nature asserts itself, Making the human irrelevant In this landscape Where sleep and death Are one And absolutes converge. No sunshine Or bird song In this dark place Defined by negatives. An eternal winter of the heart. Beyond the solace of human touch. Hoar frost has covered everything. So much whiteness— Field, trees and sky. All the same But different— Incandescent. So easy to forget That one lives in a populous city Visible above the trees At the top of both river banks. Black swallows Break from the tree tops And form a ragged line As they fly for the horizon.

Walking the Dogs

The beagles are ready to walk. They bay excitedly And run in circles, Tangling their leashes around themselves and us. They are off— One moment dragging me behind, The next, Stopping so suddenly That I nearly trip over them, As they inhale deeply, Whatever catches their eye in the grass— Whether the scent of another dog, Or morsel of discarded food. Others we meet Are of enormous interest To these curious hounds, Who want to bound up To adults, children and other dogs, And must be restrained By a pulling back on the leash. Their unbounded enthusiasm, And enjoyment of the fall day, Leaves no leeway for reflection, Or melancholy. Only when they tire, As we climb the final hill, Do they settle to a sedate pace, Leaving me in charge at last, Able to admire the golden haloes, Punctuated by clusters of red, Which are the Mountain Ashes In their fall glory, And to contemplate The grove of fir trees Pierced by a single shaft of light, Which focuses on the leaf-strewn earth, And feathers out to the spiky edges Of the trees surrounding the clearing. It is not only the beagles who perk up With excitement When the suggestion is made, "Let's go for a walk."

Winter Dawn

Dawn's rosy finger Warms the grey clouds And tips with fire the smoky stacks Of the mist-shrouded power plant. Another winter dawn And journey to work, Driving on the river road, Conscious of the vapour coming off the water. Tree branches outlined in frost, And the valley edges Crowned with highrise apartments— All part of this dream. The coldness rather than driving me indoors, Catches my imagination And I wonder At the metamorphosis. The palette of white and grey, Is augmented by mother-of-pearl, As warm life asserts itself And night becomes morning.

Reflections on Nature and Art

1 Silent ravens Soar Above the desolation, Making invisible patterns In the cloudless sky.

2 The birds are audible But not visible This winter morning In the city. Bare-branched Mountain ashes and poplars Provide no shelter. Only dense firs With their crowns of cones Offer hospitality. Songs emerge From nowhere— Sweet, Repetitive, Melodic. I have no language To describe them Other than— Chirp, chirp To-whit, to-whit. But they have Animated An ordinary morning Walk to work, Made the trees emerge From between buildings And remnants of houses On this once residential street Nature asserting itself And gladdening the heart.

3 The air is heavy With snow. No distinction between Earth and sky, Only the ribbon of asphalt Leading onward. Suddenly, A flock of snowbirds Appears, Hanging in the sky Like a character In Chinese calligraphy.

Their wings formed By a sable brush Dipped in Indian ink. Other than us, The only living element In the landscape. Until the clouds begin To move And the wind picks up snow Sweeping it down The length of the valley Disturbing the stillness. Heeding a secret call, The cluster of buntings Explodes outward And they disappear Into the pervasive Whiteness.

Snow Storm

Jagged bowing, Suggestive of icicles and cold winds, A long-dead composer’s evocation of the seasons, My background on a winter day. But the real snow Drifts down, Gently, Past dark spruce branches, And the frozen blood-red berries Of Mountain Ash. It accumulates, Imperceptibly, The stillness punctuated By the rhythmic rise and fall of bows, On massed fiddles, Now evoking the descent Of myriad individual flakes Audibly drifting down. But behind can also be heard the silence That is so much a part of falling snow.

Now, the flakes are denser, As the sharp, insistent violin bowing, Is joined by the guttural rasping of cellos, And the snow drifts and eddies around the halo of a street lamp. In the music, The storm rises and abates, But, today, nature does not toy with us, Offering only a contrast, To quiet reflection, On what the next year will bring.

Gathering of Crows

Winter afternoon, Trees outlined in the half light, Branches bare Except for the occasional Detritus of an empty nest, Evidence of another season. Some trees Have black shapes in them, Like over-sized leaves. On a closer view, A congregation of crows emerges, Sitting at branch ends in silent colloquy. So many, Perhaps fifty, Perched For no apparent reason, That I could discern In this urban landscape. An enigmatic picture That I take away. Nature, Defying me to find meaning In a gathering of crows In Midwinter.

My Parkview Garden

The trees in my back garden Are fir, Manitoba maple And another, I cannot name.

On this winter morning. They are still and, Seemingly, lifeless Until a slight movement Catches my attention. A squirrel, Leaps from branch-to-branch And tree-to-tree, Finishing with a high-wire act On the powerline. The contemplation of winter, When plants do not grow, The clearing, empty of birds And their sweet song. That time of endings, Of being trapped In the ruins of the past, Unable to evoke remembered music. Always, the clearing in the woods, In the River Valley. The stillness, Silence, The pastness of things. The inexpressible beauty Of the snow, Blinding in the sunlight And masking death. The birds have fled But I am here, Contemplating winter And making my own music. The sound of the wind Wrapping itself around the house, Whistling past obstructions And making the cold siding crack. This signals a subtle change That is not evident Until morning When water drops from the eves. Warm Chinook winds Have come over the mountains, Loosened the grip of winter And given us a taste of spring. The insistent drip of water Creates stalactites And stalagmites Of yellowy ice. But this is only temporary— Nature teasing us with hope; The next night, the house tenses, It is winter again.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog 1: Yorath House Sleeps in Snow

Words by Adriana A. Davies, Jan 5, 2022 Artwork by Marlena Wyman Jan 5-15, 2022 Artists-in-Residence at Yorath House

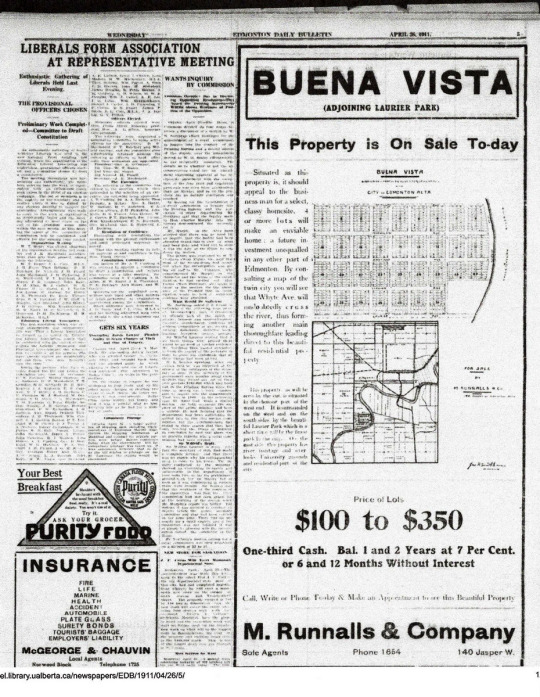

I drove from my mid-1950s bungalow in Parkview downhill, down Buena Vista Road to the flat area that is Laurier Park (named for Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier). The temperature this morning was -31 degrees Celsius and at 8:45 am there were not many cars on the road and those that were, like mine, were being driven carefully because of the thick snow that covered everything. Edmonton is truly a winter wonderland at this time of year though the admiration at its beauty, after a cold spell of nearly a month, is wearing thin. I passed the back entrance to the Valley Zoo on the way down and I tried to identify the 1950s Modern Style homes that had not been renovated and upgraded to more modern house clones, and I was pleased that there were still a few.

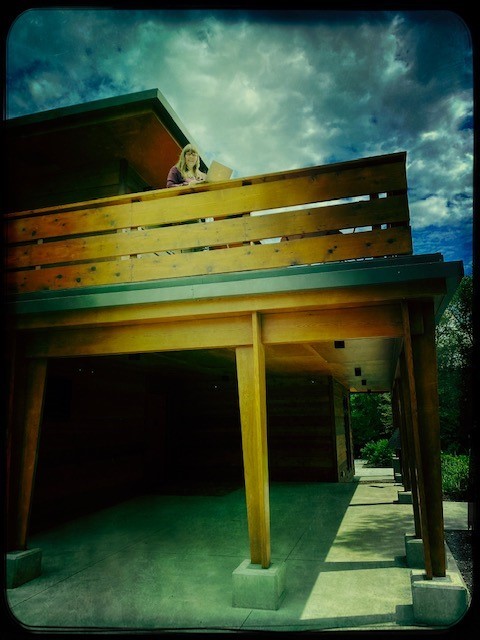

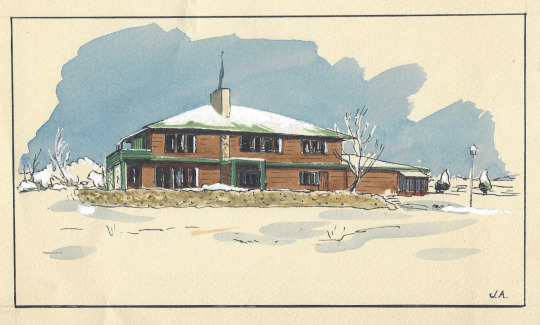

I made several turns on the flat land next to the north bank of the North Saskatchewan River that comprises part of Laurier Park and saw a sign for Buena Vista Park. I made a turn and saw the house. It is an angular, wooden-sided structure designed by the prominent architectural firm of Rule, Wynn and Rule and built for businessman and manager of Northwestern Utilities, Dennis Kestell Yorath and his wife Margaret Elizabeth (Bette) Wilkin in 1949. It was built on a 12-acre lot gifted to the couple by Bette’s father, William Wilkin who was one of the developers of the Laurier Heights subdivision.

The area at the River’s edge was once known as Miners’ Flats both because of the panning for gold that occurred along the North Saskatchewan River banks but also because of the number of coal mines that stretched along both sides of the River, the largest number in the stretch from the High Level Bridge to Cloverbar. The coal, unlike that buried deep in the Rockies, was found close to the surface of the banks of the sedimentary channel carved over the centuries by the River on its way East to its drainage in Hudson’s Bay. In the first decades of the twentieth century, there would have been miners’ shacks and some small homestead structures in the area now encompassing Laurier and Buena Vista parks.

All that was to change in the late 1940s as a result of the post-war boom experienced by Edmonton and other Alberta communities. Almost 60 percent of the residences in the Laurier Heights subdivision were built in the years 1946 to 1960; the rest, in the period 1961 to 1970; thus, the neighbourhood was not part of the inner “circles” of historic Edmonton neighbourhoods including not only the City Centre communities but also Westmount, Glenora, the Groat Estates and Capitol Hill. Laurier was built as a part of the movement westward that included Crestwood, Parkview and Valleyview neighbourhoods.

Architectural drawing of Yorath House by Rule, Wynn & Rule, 1949. Yorath family collection.

Yorath House, when it was built, made a bold statement both in its design and materials used. It did not hearken back to the past and the Craftsman Style houses made of brick and wood, and the brick public and retail buildings of past generations with Tindall stone trim. It was unlike the small stuccoed houses built for working class families. The new business elite wanted houses that were more futuristic in design and that affirmed that this was not their parent’s house. They seemed to say, “Look at us; we are part of the new world of prosperity based on resource wealth.” Edmonton looked to Toronto and New York for design influences. Rule, Wynn and Rule represented that larger world of architecture. Some iconic buildings that they designed include Glenora School, the Petroleum Club (demolished), U of A Rutherford Library, Eastglen Composite High School, AGT Building, Northwestern Utilities Building (now Milner Building), William Shaw House (St. George’s Crescent) and Varscona Theatre (demolished).

It was the fitting house for a young couple (he was born in 1905 and she in 1912) with an established British lineage on both sides of their family trees. Christopher James Yorath, Dennis’ father, left the UK with his young family in 1913 to become the Commissioner of the City of Saskatoon and then moved on to Edmonton in January 1921 to head the public works department of the City of Edmonton and, subsequently, became City Commissioner. He then moved to Calgary and was instrumental in the creation of gas and utility companies. William Lewis Wilkin, Betty’s father, left the UK in 1892 on the White Star liner Teutonic and initially worked for his maternal uncle, Henry (Harry) Wilson, a Whyte Avenue merchant, before striking out on his own in various business ventures including mercantile and property development. Dennis followed in his Father’s footsteps becoming involved in the natural gas industry in Calgary and, later, various utility companies that were local, national and international.

What drew me to the art residency was not only because I knew Laurier Park well having taken my children and grandchildren there for many outings over a period of 40 years but also because I had done the biography of Christopher Yorath for the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (to be published online in 2022) and, in the course of the research, had met several family members. I felt that the residency would allow me not only to further explore the history of the family but also to pursue another love, nature poetry. It would also allow me to work with Marlena Wyman, visual artist and archivist, who has begun the residency by documenting the house using her urban sketching skills.

Marlena Wyman & Adriana Davies in front of Yorath House, January 15, 2022. Photo by David Johnston.

On this unusually cold winter morning, I was wrapped up in a down coat with a hood and wearing silk long johns under my slacks, and my face was covered with a Covid mask (great in cold weather). I drove the car very close to the house and parked next to a City of Edmonton white truck. The young man blowing the snow off the walks around the house helped me to carry in my boxes and bags with research materials, books, laptop and various edibles since I’ll be working at the house all day (except for occasional forays to the City of Edmonton and Provincial Archives) until March 2nd.

I am now seated in the designated artists’ studio in one of the bedrooms on the second floor. It overlooks the small, cleared parking lot – not that you would know that it served that function since everything is covered in snow and the house is surrounded by beautiful fir trees of various types and hardy deciduous trees.