#xi hist

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

💐💐💐💐💐💐💐💐💐

EVANGELHO

Quinta Feira 12 de Setembro de 2024

℣. O Senhor esteja convosco.

℟. Ele está no meio de nós.

℣. Proclamação do Evangelho de Jesus Cristo ✠ segundo Lucas

℟. Glória a vós, Senhor.

Naquele tempo, falou Jesus aos seus discípulos: 27“A vós que me escutais, eu digo: Amai os vossos inimigos e fazei o bem aos que vos odeiam, 28bendizei os que vos amaldiçoam, e rezai por aqueles que vos caluniam. 29Se alguém te der uma bofetada numa face, oferece também a outra. Se alguém te tomar o manto, deixa-o levar também a túnica.

30Dá a quem te pedir e, se alguém tirar o que é teu, não peças que o devolva. 31O que vós desejais que os outros vos façam, fazei-o também vós a eles. 32Se amais somente aqueles que vos amam, que recompensa tereis? Até os pecadores amam aqueles que os amam.

33E se fazeis o bem somente aos que vos fazem o bem, que recompensa tereis? Até os pecadores fazem assim. 34E se emprestais somente àqueles de quem esperais receber, que recompensa tereis? Até os pecadores emprestam aos pecadores, para receber de volta a mesma quantia. 35Ao contrário, amai os vossos inimigos, fazei o bem e emprestai sem esperar coisa alguma em troca. Então, a vossa recompensa será grande, e sereis filhos do Altíssimo, porque Deus é bondoso também para com os ingratos e os maus.

36Sede misericordiosos, como também o vosso Pai é misericordioso. 37Não julgueis e não sereis julgados; não condeneis e não sereis condenados; perdoai, e sereis perdoados. 38Dai e vos será dado. Uma boa medida, calcada, sacudida, transbordante será colocada no vosso colo; porque com a mesma medida com que medirdes os outros, vós também sereis medidos”.

- Palavra da Salvação.

💐💐💐💐💐💐💐💐💐

- Comentário do Dia

💎 Um amor escandaloso

“Vós ouvistes o que foi dito: ‘Amarás o teu próximo e odiarás o teu inimigo!’ Eu, porém, vos digo: Amai os vossos inimigos e rezai por aqueles que vos perseguem!”

Amor aos inimigos (Mt 5,43-48). — V. 43. A antiga Lei mandava amar o próximo (Lv 19,18); mas pelo nome próximo (רֵעַ, amigo, companheiro) entendia-se somente o da mesma tribo ou nação, i.e. um homem da mesma origem (israelítica) e da mesma religião, como se vê pelo contexto. Isso é confirmado por ditos rabínicos que explicam Lv 19,18: [amarás] “o próximo, não [porém] os outros [i.e. os estrangeiros]”; “o próximo, mas não os samaritanos, estrangeiros, prosélitos tôshâbh [i.e. não conversos]” (cf. Mekhilta xxi 14.35, apud *Strack-Billerbeck i 354). A segunda parte, odiarás o teu inimigo, i.e. os estrangeiros, os não judeus etc., não consta na Lei nem em outros escritos, mas parece ser uma consequência prática ou também uma glosa rabínica; ao menos exprime com exatidão o espírito dos judeus daquela época.

Esta consequência (glosa) e espírito nasceram paulatinamente do preceito da Lei acerca da destruição dos outros povos (cf. Ex 17,16; Dt 7,2; 20,13-18; 23,4-7; 25,17ss; Nm 34,52.55; 1Sm 15,3 etc.); a inimizade com os gentios converteu-se assim em ódio contra qualquer estrangeiro. Além disso, inúmeras passagens do AT parecem respirar vingança e ódio, seja nacional ou religioso (cf. 1Rs 2,8s; Jr 18,19ss; Sl 108 [109] etc.). Estes sentimentos foram alimentados, sobretudo na época dos Macabeus, por contínuos conflitos pro aris et focis. De fato, os judeus tanto prática como doutrinalmente tinham ódio encarniçado a qualquer estrangeiro. São célebres as palavras de Tácito a esse respeito: “Entre eles, a fidelidade é inquebrantável e rápida a misericórdia, mas contra os de fora impera um ódio hostil” (hist. v. 5; cf. Flávio Josefo, antiq. xi 6, 5; Cícero, pro Flacco 28). Além disso, a Mishna recomenda com frequência ter ódio aos israelitas infiéis, samaritanos, hereges, publicanos, ammê ha-’ares etc. Com toda a razão, pois, o Senhor podia dizer: Ouvistes o que foi dito… odiarás 😊 te é lícito odiar) o teu inimigo [1].

V. 44. (cf. Lc 6,27s.35) Cristo aperfeiçoa o preceito da antiga Lei sobre o próximo e corrige a interpretação perversa que se lhe dera. Os discípulos da Nova Lei devem amar não só o próximo (amigos, familiares, conterrâneos etc.), mas também os inimigos, i.e. aqueles que os odeiam e perseguem (Mt.), amaldiçoam e caluniam (Lc.). A esta quádrupla manifestação de ódio se deve corresponder com os atos contrários: amai e orai (Mt.), abençoai e fazei bem (Lc.). Logo, há que responder ao ódio com afeto, desejo, oração e boas obras. Põem-se em seguida alguns exemplos de boas obras: dar em empréstimo o que se pede, sem esperar recompensa (Lc.), saudar (Mt.) etc.

O amor aos inimigos de algum modo já aparece no AT (e.g. Ex 23,4s; Pv 25,21s, onde se prescreve auxiliar o inimigo em necessidade). Mas estas passagens, na verdade, nunca chegaram a melhorar as disposições dos judeus para com os inimigos, muito menos lhes sugeriram um princípio positivo e universal, semelhante ao de Cristo, sobre o amor aos inimigos. No máximo, algumas expressões recomendam aqui e ali não se alegrar com as adversidades dos inimigos, não pagar o mal com o mal e coisas afins. O primeiro de todos a promulgar a doutrina exposta acima foi Cristo, doutrina que seus discípulos abraçaram de todo o coração (cf. Rm 12,14-21; 1Pd 3,8s; Santo Inácio, ad Eph. 10,23s etc.). Eis a maior glória do Evangelho em matéria moral: “Amar os amigos, todos o fazem; amar os inimigos, somente os cristãos” (Tertuliano, ad Scap. 1: M 1,777).

V. 45ss. Para melhor persuadir seus ouvintes deste dever de amor universal, o divino Mestre recorre a três argumentos. Devem, pois, amar os inimigos: a) para se tornarem filhos do (i.e. semelhantes ao) nosso Pai, que faz nascer o Sol sobre maus e bons etc., ou seja, que dá a todos indiscriminadamente a graça de seus múltiplos benefícios [2]; b) para terem direito a alguma recompensa, i.e. para que suas ações sejam dignas de prêmio, pois quem ama apenas os seus, com amor meramente natural e em proveito próprio, não receberá de Deus retribuição alguma; c) para fazerem mais do que já fazem os pagãos e os publicanos (em Lc 6,32: os pecadores), pelos quais os judeus tinham um profundo desprezo (cf. Dt 7,2; Mt 18,17; At 10,28 etc.).

V. 48. Este v. contém a regra de perfeição que nessa matéria cumpre seguir: Portanto, sede perfeitos (τέλειοι) como o vosso Pai celeste é perfeito. Como se depreende do contexto e de Lc. (6, 36: Sede pois misericordiosos), em particular, é evidente que toda esta cláusula apresenta um resumo da exortação à caridade fraterna feita acima, ainda que possa interpretar-se também em sentido amplo e aplicar-se a qualquer outra virtude.

Deus abençoe você!

💐💐💐💐💐💐💐💐💐

0 notes

Text

Furcht und Elend im dritten Reich (~ 'Fear and Misery in the Third Reich' original title: Deutschland - Ein Greuelmärchen, based on H. Heine's "Deutschland ein Wintermärchen"; the final title is a reference to Balzac's novel "Glanz und Elend der Kurtisanen") by Bertolt Brecht and Helene Weigel - written between 1935 and 1939 in emigration. Based on eyewitness reports and newspaper notes. The scenes were printed in 1938 for the Malik publishing house in Prague, but could no longer be distributed as a result of the Hitler invasion.

Excerpt from the play - notes, historical considerations and interpretations

'For the poor' and yet against them [excerpt from the 24 chapters, especially considering the propagandistic claim to be politics for the poor, whereas the ideas are more and more intensifying the precariousness, free translation of mine]

"There they come down: A pale, motley heap. And high in front A cross on blood-red flags That has a big swastika For the poor man" [The German Army Show, 2nd verse]

"The widows and orphans are coming For them a good time is promised too. But first they must sacrifice and tax Because they make meat more expensive. The good time is far away." [Chap. XI.]

"The class conciliators press For boots and bad food The poor to labour service. They see a year in the same kit The sons of the rich. Would rather have a profit." [Chap. XII.]

"The winter helpers enter With banners and trumpets Even into the poorest house. They proudly drag extorted Rags and leftovers For the poor neighbour.

The hand that slayed their brother Is enough for them not to complain A charitable gift in a hurry. The alms wafers remain Stuck in their throats And the Hitler salvation too." [Chapter XVI.]

"They fetch the young and tan dying-for-the-rich Like the multiplication table. Dying is probably harder. But they see the teachers' fists And are afraid to be fearful." [Chap. XXI.]

"The job creators are coming. The poor man is their kaffir They put him where they want. He may serve them again He may pay their war machines Pay blood and labour sweat." [Chap. XXIII.]

VI The practicing of law; Augsburg 1934, consultation room in a courthouse; magistrate uncertain about the jurisdiction

Introductory poem

"Then the master judges came To whom the rabble said: Law is what benefits the German folk. They said: How are we supposed to know that? So they will have to speak in accordance with the laws Until the whole German people are seated."

Conversation between magistrate and inspector

The indictment consists of only one page and is the "leanest and sloppiest that the district judge has ever come across" Inspector: Mr District Judge, I have a family Consideration of charges by provocation

District judge and inspector

Problem: certifying the Jew's innocence means that in the Third Reich a Jew can be proven right against the SA; solution: the SA stole the jewellery in national excitement

Maid

"Half of the storm are former criminals, the whole neighbourhood knows that. If we didn't have our justice system, they would still be dragging away the cathedral church."

Magistrate and district court judge

"I'm prepared to do anything, Jesus, understand me! You've changed completely. I'll decide like this, and I'll decide as required, but I have to know what's required. If you don't know that, there is no justice."

Hist. Background: National Socialist propaganda effectively used the justice system to spread its ideology and influence the population. The National Socialist justice system was used by the National Socialist German Labour Party (NSDAP) as an instrument to enforce its ideology and propaganda.

Development of the Justice System:

Guidelines for National Socialist propaganda in Hitler's "Mein Kampf": Adolf Hitler already emphasised the importance of propaganda aimed at the feelings of the masses in his work "Mein Kampf"; Psychology of the masses

Before 1933: Propaganda techniques were used even before the Nazis came to power. After 1933, however, the judicial system was heavily politicised and used for the National Socialist agenda

After the Nazis came to power in 1933: The Reich Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, under the leadership of Joseph Goebbels, played a central role in the dissemination of National Socialist propaganda. Books, newspapers, radio and films were used as means of dissemination.

Instrumentalisation of the judiciary:

The judical system was violeted for politcal purpose. The undermining and politicisation of the judiciary increased arbitrariness and lawlessness

The control of public communication had a high priority for the regime, for strenghening the power and to prepare the propaganda for the war and the extermination of Eurpean Jews.

Notices in German [formatting costed too much energy and nerves, just was able to correct a bit - very unordentlich!]

#literature#world literature#Bertolt Brecht#reading stage-play aloud#stage-play#reading#books about nationalsocialism#1935#1939#Brecht#Helene Weigel#remembering against fascism#fascism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chinglish

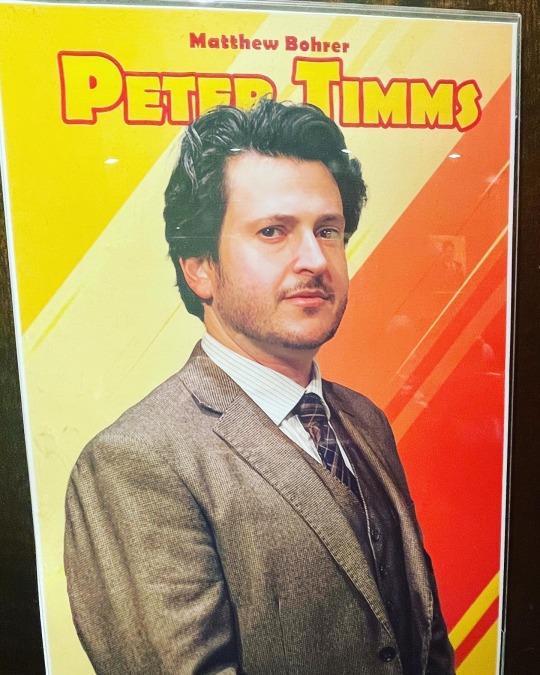

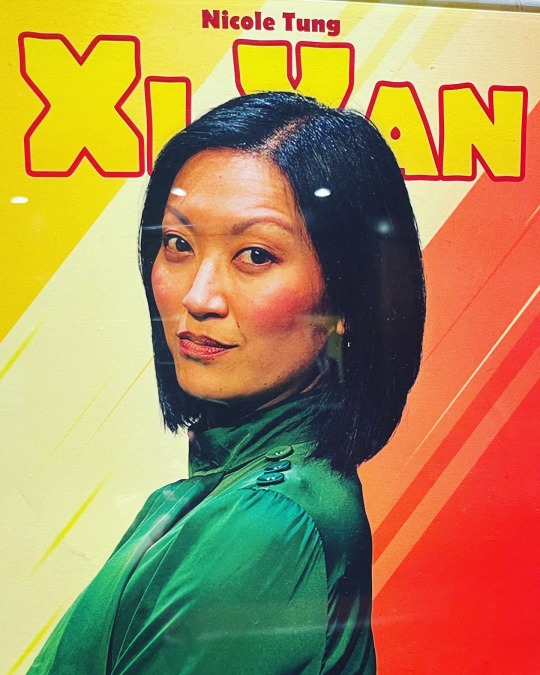

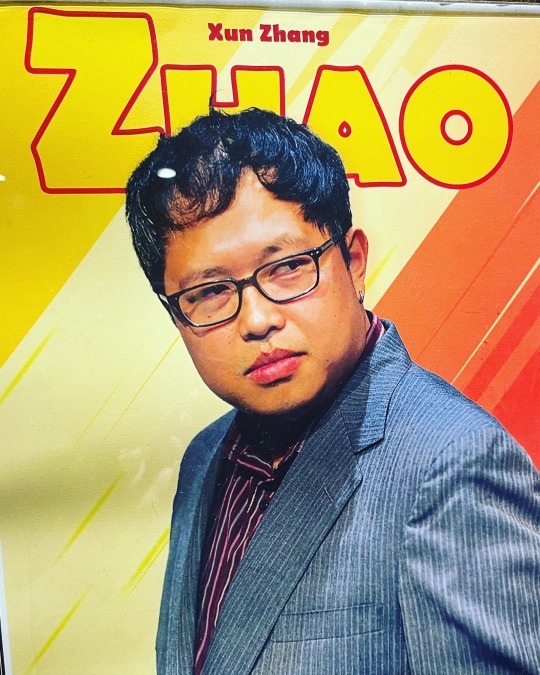

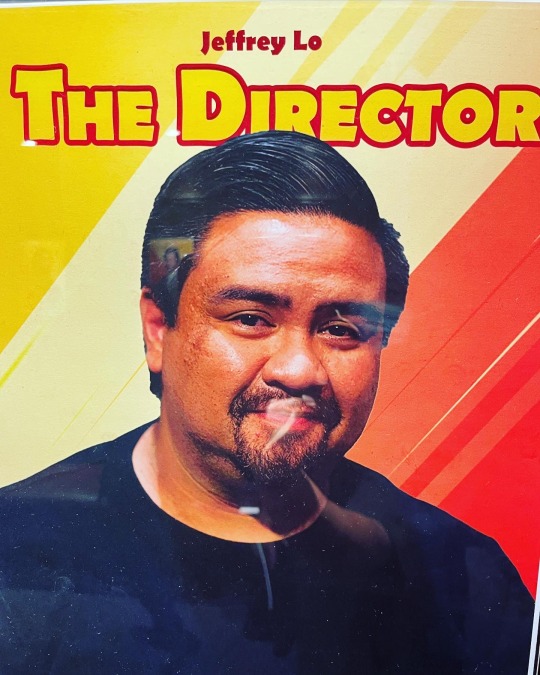

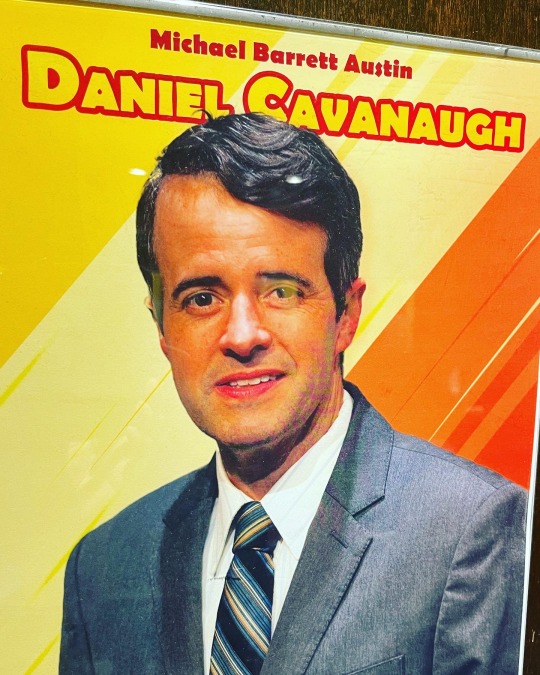

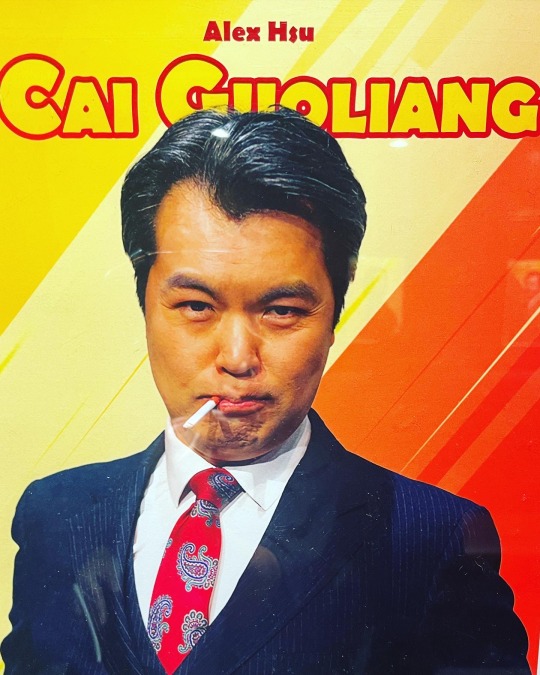

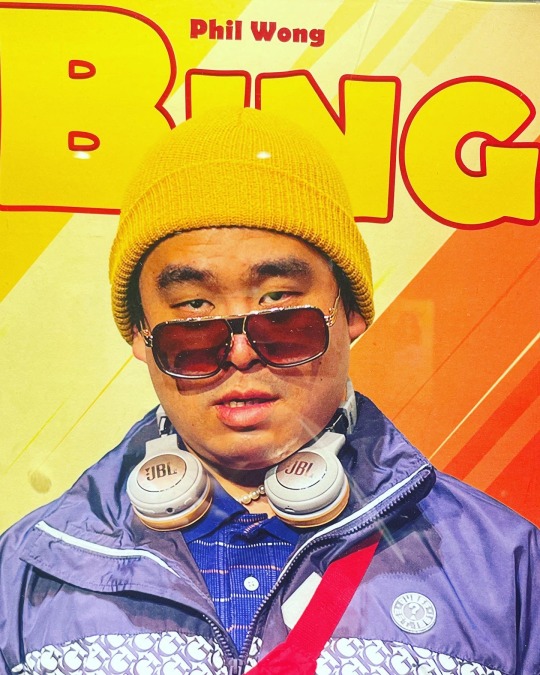

Bill English presents “Chinglish" at the San Francisco Playhouse. The play is written by David Henry Hwang and directed by Jeffrey Lo. It features a cast including Michael Barrett Austin as Daniel Cavanaugh, Matthew Bohrer as Peter Timms, Alex Hsu as Cai Guoliang, Sharon Shao as Miss Qian/Prosecutor Li, Nicole Tung as Xi Yan, Phil Wong as Bing/Judge Xu Geming, and Xun Zhang as Zhao. The play will run at SF Playhouse until June 10. Tickets are available at Sfplayhouse.org

The show is a hilarious romp at getting lost in translation that is common with the inter-mingling of multi-cultural characters/settings as in the play when a Cleveland based businessman decides to go to China to expand his Signs making business by translating signs in the upcoming construction of a cultural center.

Chinglish" is a comedic play written by David Henry Hwang, an acclaimed American playwright known for works like "M. Butterfly."

“Chinglish" explores cultural and linguistic barriers in the context of business relations between China and the Western world. It tells the story of an American businessman who travels to China to secure a lucrative contract but encounters numerous misunderstandings and cultural clashes due to language differences and cultural nuances.

The play uses humor to highlight the challenges of cross-cultural communication and sheds light on the complexities and misinterpretations that can arise in such situations. "Chinglish" has been praised for its witty dialogue and sharp observations about cultural differences. It provides an opportunity for audiences to reflect on the intricacies of language and cultural exchange in a globalized world.

Overall, "Chinglish" has received positive reviews for its clever writing and thought-provoking themes. However, theater experiences are subjective, and individual opinions may vary. It's always best to read multiple reviews or watch the play yourself to form your own judgment.

Renowned Playwright

David Henry Hwang is a renowned playwright known for his insightful works that explore themes of identity, culture, and Asian-American experiences. Some of his notable plays include:

1. "M. Butterfly" (1988): This Tony Award-winning play is Hwang's most famous work. It is a fictionalized retelling of the true story of a French diplomat who carries on a 20-year affair with a Chinese opera singer, unaware of his lover's true gender.

2. "Chinglish" (2011): A comedy that delves into the complexities of cross-cultural communication and business relations between China and the Western world. It humorously examines the challenges faced by an American businessman trying to navigate language and cultural barriers.

3. "Yellow Face" (2007): Blending fact and fiction, this play explores themes of racial identity and self-discovery. It follows Hwang's own experiences with the casting controversy surrounding his play "Face Value" and touches on broader issues of cultural representation in the entertainment industry.

4. "The Dance and the Railroad" (1981): Set in the 1860s, this play tells the story of two Chinese laborers working on the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad and their struggle to maintain their dignity and cultural identity in the face of adversity.

5. "Golden Child" (1996): Inspired by Hwang's own family history, this play examines the conflicts that arise when a traditional Chinese family in early 20th-century China embraces Western influences, particularly Christianity.

These are just a few examples of David Henry Hwang's works, but he has written many more plays and contributed to various other projects in the field of theater. His plays often explore themes of cultural assimilation, racial identity, and the complexities of East-West encounters.

US- China Relations History

The history of U.S.-China relations is complex and spans several decades. Here is a brief overview of some key milestones:

1. Early Relations: In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, U.S. traders established contact with China, primarily through the port of Canton (now Guangzhou). However, diplomatic relations were only established in 1844 with the Treaty of Wanghia.

2. Boxer Rebellion and Open Door Policy: In the early 20th century, the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) led to increased anti-foreigner sentiment in China. Following this, the United States advocated for an Open Door Policy to ensure equal commercial access for all nations in China.

3. World War II and the Civil War: During World War II, the United States and China were allies against the Axis powers. However, after the war, China descended into a civil war between the Nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek and the Communists under Mao Zedong.

4. Recognition of the People's Republic of China: In 1949, the Communists emerged victorious, and the People's Republic of China (PRC) was established. The United States initially did not recognize the PRC and continued to recognize Taiwan (Republic of China) as the legitimate government of China until 1979.

5. Ping Pong Diplomacy and Normalization: In the early 1970s, a series of events, including the "ping pong diplomacy" and secret negotiations, led to a thaw in U.S.-China relations. In 1972, President Richard Nixon visited China, and diplomatic relations were normalized in 1979 under President Jimmy Carter.

6. Trade and Economic Relations: Since the late 1970s, the U.S. and China have engaged in extensive trade and economic ties. China's economic reforms and opening up led to a significant increase in bilateral trade, with China becoming one of the United States' largest trading partners.

7. Human Rights and Political Differences: The U.S. and China have had ongoing disagreements over issues such as human rights, religious freedom, intellectual property rights, and cybersecurity. These differences have at times strained the bilateral relationship.

8. Taiwan and Hong Kong: The U.S. maintains unofficial relations with Taiwan and has been a long-standing supporter of its security. The issue of Hong Kong's autonomy and the erosion of its freedoms have also become contentious topics in recent years.

9. Strategic Competition and Cooperation: In recent years, the U.S.-China relationship has become more complex, characterized by both cooperation and competition. Issues such as trade imbalances, intellectual property theft, cybersecurity, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and human rights concerns continue to impact the relationship.

It's important to note that the dynamics of U.S.-China relations are subject to change, and ongoing developments will shape the future trajectory of this significant bilateral relationship.

0 notes

Text

timelines for SEA (Vietnam, Indonesia, Burma)

VIETNAM

1944: Brazzaville Declaration 1945 Mar: Vietminh replaced by Bao Dai 1945 May: General Vo Nguyen Giap 1945 Aug: Vietminh as the predominant political force 1945 Sep: DRV (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) 1945 Nov: dissolved Indochina Communist Party 1946 Jan: Vietminh victory over VNQDD 1946 Mar 6: Treaty of Hanoi 1946 Nov 22: Vietnamese troops fired upon 1946 Nov 23: French troops sent ultimatum, killed 1950-51: war exacting huge toll on France 1951: the Party set up Communist parties 1954 Mar: Dien Bien Plan 1954 Apr: negotiations 1954 May 7: French surrender 1954 July: Paris declared Indochina independent 1954-1956: land reforms, Lao Dong Party, DRV’s military, PAVN 1955: pro-American Ngo Dinh Diem 1958-1960: first Three Year Plan 1960: Vietcong 1963: Buddhist Crisis + military coup (Diem killed) 1964: Tonkin Gulf Incident 1965: Major-General Nguyen Van Thieu leader of Saigon government 1965 Feb: US carpet bombings 1965 Dec – 1966 Jan: Rolling Thunder (airstrikes) 1968 Jan 30: Tet offensive 1968 Mar: My Lai Massacre 1968: succeeded by Nixon 1969: DRV’s influence bolstered by Provisional Revolutionary Government 1973: US and North Vietnam signed the Paris Peace Agreement 1973 Mar 29: last American troops left 1975 Apr: North Vietnamese finally conquered the South (unified = Socialist Republic of Vietnam) 1976 Jul 12: official proclamation of founding of newly reunified Vietnam

INDONESIA

1945: collapse of Japanese 1945 June: Pancasila principles introduced 1945 Aug 17: Sukarno compelled to issue declaration of Indonesian independence 1945 Sep 15: Dutch officials returned --> Battle of Surabaya 1945 Oct: Sukarno sidelined by Republican government 1945 Nov: Battle of Surabaya ends 1945 Dec: Indonesian Socialist Youth Party and Indonesian Socialist Party (PSI 1946: social revolution (challenged by the youth) 1946 Nov: Linggadjati Agreement (recognition of authority of Indonesian republic) 1947 Aug: First Police Action 1948 Jan: Renville Agreement 1948 Sept: Madiun Affair (communists VS Sukarno) - Republican Army turned to guerrilla warfare 1948 Dec: Second Police Action 1949 Jan: US threatens to withhold Marshall Aid from Netherlands 1949 Aug-Nov: Roundtable Conference 1949 Nov 2: Hague Agreement (United States of Indonesia would gain independence)

BURMA

1945 May 7: Burma White Paper 1945 Oct: civil government set up (under British) -- nationalists demand immediate independence 1946: rallies and protests, Aung San re-arming People’s Voluntary Organisations 1946 Jan: mass rally at Shwe Dagon Pagoda -- Dorman Smith attempted to arrest Aung San 1946 Jan: AFPFL expels ‘red flag’ communist faction 1946 Aug: Sir Hubert Rance replaced Dorman Smith 1946 Sep: Rance arrives in Burma 1946 Sep 2: Thakins goes on strike, Executive Council is forced to resign 1946 Sep 26: Rance appoints a new Executive Council (Burmese now 6/11) 1946 Nov: Aung San tours frontier regions 1947 Jan: Aung San leads delegation to London to negotiate independence 1947 Jan: Aung San-Attlee Agreement signed 1947 Feb: Panglong Agreement (guaranteed minority rights), agreed to establish two autonomous states 1947 Apr: Constituent Assembly elections (AFPFL won 173/210) 1947 July 19: Aung San assassinated 1949 Jan 4: Union of Burma official – 2 legislative chambers

0 notes

Text

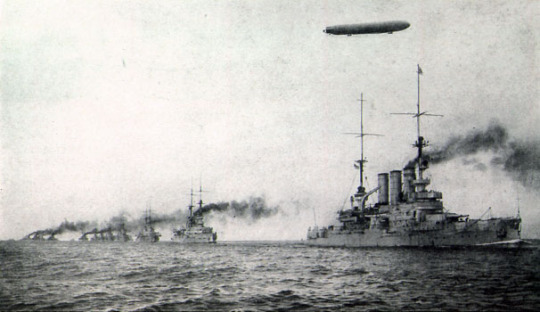

UNA ARMADA CREPUSCULAR: LA MARINA IMPERIAL ALEMANA (1872 – 1919 )

Héctor López Aréstegui

“….Los caminos de hierro nos conducirán solamente con mayor rapidez al abismo”

- François – Rene de Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848)

La guerra se nutre de equívocos y, acaso, el mayor de ellos resulte ser el concepto que la historia le escriben los vencedores. Y es que vencedor y vencido no son categorías absolutas, y que “todos somos vencedores y vencidos al mismo tiempo al describir en nuestros éxitos, pues también exponemos el arduo problema de no olvidar el alcance de nuestras fuerzas[i]”· Creemos que esta frase, tomada del prefacio de las memorias de guerra del almirante alemán Reinhard Scheer (1863 – 1928), describe con justicia el carácter de la guerra naval durante la Gran Guerra y, en particular, la existencia crepuscular de la Marina Imperial Alemana (1872 – 1919), cuya historia merece ser mejor conocida y trascender el alcance de la cita churchilliana que constituye su lapida ante el tribunal de la Historia, “la flota alemana es un lujo, no una necesidad nacional”.

1. ¿Qué es Alemania?

¡Alemania! ¿Qué es Alemania? El gran poeta Johan Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832) pensaba que era una entelequia en tanto los alemanes no superaran su sempiterna tradición de rivalidad y fragmentación[ii], basculando – desde el siglo XVIII – ora bajo la égida de Prusia, ora a la de Austria. A partir del efecto de las Revolución de 1848[iii], que barrió el orden europeo creado por el Congreso de Viena de 1814 – 1815, Alemania fue tomando forma, a golpes del cincel del nacionalismo, constituyendo la fase final del proceso las guerras de unificación contra Dinamarca, Austria y Francia (1864 – 1871). La victoria sobre Francia en la guerra Franco – Prusiana (1870 – 1871), fue el hecho político – militar que transformó la Confederación de Estados Alemanes surgida de la derrota austriaca de 1866 en el Segundo Reich[iv] alemán, constituyéndose Prusia en su estado director. El 18 de enero de 1871 en Versalles, Francia, iniciábase el proceso de convertir “un mosaico de curiosidades políticas y la idea medieval del Imperio resucitado[v]” en un estado a la par de los paradigmas de la época, Francia e Inglaterra.

El Reich era una idea medieval, difícil de definir y mucho más de traducir al lenguaje político de la época. Bajo su sombra coexistían – desigualmente – principios absolutistas de la monarquía prusiana y los democráticos de la Revolución de 1848. El nuevo Estado era una monarquía federal, “una reunión de Estados, bajo la legal y efectiva hegemonía de un Estado director, que es Prusia. Prusia, al crear con su esfuerzo el gran Imperio alemán, recibió el encargo de dirigirlo, obteniendo con ello ciertos privilegios sobre los demás, principalmente en todo lo relacionado con la política militar y comercial de la Confederación[vi]”. El Bundsrat (Consejo de la Corona) era la cima de su estructura del poder constituido, con competencia exclusiva en materia de defensa, legislación civil y penal, comercio y orden económico; los gobiernos estaduales lo eran para los demás asuntos dentro de sus límites territoriales. La administración imperial recaía en la Cancillería del Reich, que la ejercía el Ministro Presidente de Prusia. Descolgada de esta jerarquía, el Reichstag (Dieta Imperial), de elección popular, servía – en la práctica – de órgano consultivo para los asuntos de competencia del gobierno imperial[vii]. Este esquema de gobierno era el resultado de las maniobras políticas del canciller – ministro presidente de Prusia Otto von Bismarck, para quien la monarquía prusiana tenía el derecho y el deber de dominar el proceso de unidad alemana, lo cual excluía toda forma de gobierno parlamentario que controlara la acción del monarca. Así, pues, el artículo 4 de la Constitución de 1871 establecía que el soberano tenía el derecho “de convocar, abrir, prorrogar y cerrar el Reichstag y el Bundsrat[viii]”.

2. El llamado del mar

La nación alemana estaba obsesionada con sus fronteras, históricamente precarias y expuestas a la presión de sus vecinos. El geógrafo y politólogo sueco Johan Rudolf Kjellén[ix] (1864 – 1922), afirmaba que éstas podían calificarse de malas y eran la fuente de la inseguridad y vacilación de su política exterior e interior. Las postrimerías del siglo XIX añadieron al problema una nueva dimensión: la marítima. En su obra “Las Grandes Potencias de la Actualidad” (1911) Kjellen describía la situación: “Si se tiene en cuenta los grandes intereses marítimos de Alemania, lo que el Rin ha llegado a representar en el interior del país como vía de comunicación comercial y la riqueza que se levanta sobre sus riberas, se comprenderá cuán penoso ha de resultar para Alemania el no poseer la desembocadura del Rin. En Oriente le pasa a Alemania con el Vístula lo que a los Países Bajos con el Rin: no posee nada más que su curso medio. Con el Rin es Holanda la que le roba a Alemania su natural con el mar; en el Vístula, Alemania es quien le roba la suya a Rusia. Lo mismo sucede algo más con el Este con el Memel; también con este río es Alemania la favorecida, con perjuicio de Rusia[x] ”.

Sin embargo Prusia estaba anclada en el brillo de la gloria de las guerras de unificación[xi]. La guerra era, según la definición uno de los intelectuales más reconocidos de la época, el historiador Heinrich von Treitschke (1834 – 1896), “el medio de grabar en la mente del individuo el binomio patria – nación, a fin de que trascienda de sí mismo y liberte a la nación del destino que había tenido hasta las guerras napoleónicas, ser el campo de batalla de casi todos los conflictos bélicos de Europa”. El almirante Reinhard Scheer (1863 – 1928), que creció en aquel ambiente de exaltado nacionalismo, dejó testimonio de ello en la introducción de sus memorias de guerra: “Del lado opuesto Prusia – Alemania. Toda su historia marcada por la lucha y la angustia, porque las guerras europeas tuvieron lugar preferentemente en su territorio. Era la nación del Imperativo Categórico, presta a las privaciones y al sacrificio, siempre levantándose una y otra vez, hasta que finalmente pareció haber alcanzado el éxito a través de la unificación del Imperio y ser capaz de cosechar los frutos duramente ganados de una posición de poder. La victoria sobre las adversidades solo pudo lograrse gracias a su idealismo y probada lealtad a la Patria bajo la opresión del gobierno extranjero. La fuerza de nuestro potencial defensivo descansaba sobre todas las cosas en nuestra conciencia e integridad adquiridas por la estricta disciplina[xii]”.

Así, al iniciar su andadura como estado unificado, en Alemania no se tenía en consideración la célebre máxima romana “Navegar es necesario, vivir no lo es[xiii]”. Prusia no era consciente de esta verdad porque había vivido casi toda su historia de espalda al mar. Por ser la más pequeña y la más joven de las potencias europeas surgidas de las guerras de religión de los siglos XVI y XVII, sus recursos financieros siempre habían sido escasos y, por ello, sus formaciones navales efímeras. Además, su vecindad con grandes potencias marítimas (Dinamarca, Holanda, Suecia, Francia e Inglaterra) abonaba a favor de la idea de invertir en un poderoso ejército en lugar de una débil armada. El único chispazo de tradición marítima alemana era el recuerdo de la Liga Hanseática (1358 – 1630), una federación comercial y defensiva de ciudades del norte de Alemania y de las comunidades de comerciantes alemanes en el mar Báltico, los Países Bajos, Suecia, Polonia y Rusia. El Margraviato de Brandeburgo – el antecedente medieval de Prusia – apenas participó en esta alianza. Así, mientras el Rey – sargento Federico Guillermo I de Hohenzollern (1688 – 1740) y su sucesor Federico II (1712 – 1786) creaban el ejército modelo del mundo europeo de la Edad Moderna, el dominio del mar se convertía en el elemento clave en la diferenciación entre los estados. No bastaba con proteger las costas de la flota enemiga sino ser capaz de explorar los mares allende de las mismas. La fuente de riqueza de las naciones era el comercio marítimo. Prusia – y posteriormente el binomio Prusia – Alemania a fines del siglo XIX – aún no habían dado ese paso, el cual que elevó – en su momento – a Portugal, España, Francia e Inglaterra como potencias mundiales.

Alemania hubo de esperar a que surgiese una figura que encarnase el llamado del mar. Este personaje fue el príncipe Adalberto de Prusia (1811 – 1873), fundador de la efímera flota de la Confederación de Estados del Norte de Alemania, la Reichsflotte[xiv] (1848 – 1852) y de la Marina Prusiana (1850 – 1867). No es fácil definir la personalidad del príncipe Adalberto, acaso lo más preciso es decir que fue para su patria en una sola persona lo que para Portugal significó el príncipe Enrique el Navegante (1394 – 1460) y para Inglaterra Samuel Pepys (1633 – 1703), el organizador de la Royal Navy. La voz del príncipe era la vocera de muchas otras que recordaban las razones por las que se debía contar con una armada que protegiera permanentemente las costas de invasores, bloqueara los puertos del enemigo en caso de guerra y salvaguardara el comercio exterior en aguas allende del norte de Europa. Convergían con su opinión las ideas de personajes como el economista Freidrich List (1789 – 1846), creador del Sistema de Innovación Nacional – léase, en términos contemporáneos, la Teoría del Desarrollo Económico –, quien señalaba que una flota permanente debía existir por y para un bien común, la defensa y la proyección de la identidad nacional alemana[xv].

La mano creadora de la Marina Imperial Alemana (Kaiserliche Marine) fue la del general Albretch von Stosch (1818 – 1896), quién imprimió en sus acciones un norte claro: una institución de unidad nacional, defensora de soberanía marítima y del comercio exterior. El desafío era inmenso. Corrían tiempos de cambio tecnológico y de la naturaleza jurídica de la guerra en el mar. Los mayores obstáculos eran, como ya lo hemos señalado anteriormente, la posición geográfica de Alemania y la falta de una tradición naval. A su favor Von Stosch contaba con el apoyo político del canciller Bismarck y de un generoso presupuesto para un programa naval de diez años según el cual se construirían ocho fragatas blindadas, seis corbetas blindadas, veinticuatro corbetas ligeras, siete monitores, dos baterías flotantes, seis avisos dieciocho cañoneras y veintiocho torpederos, parcialmente financiado con los pagos que hubo de hacer Francia al Reich como compensación de los gasto de la guerra de 1870 – 1871. En una década (1872 – 1882) Von Stosch creó una armada de la nada, formó a sus oficiales y tripulantes y dotó a Alemania de una industria naval propia. Lo hizo con pragmatismo, consciente de la incertidumbre reinante sobre el futuro del poder marítimo[xvi]. Así, el SMS Hansa (1872) y el SMS Preussen (1873) fueron dos buques exponentes de lo que significaba para Alemania el poder naval: respeto de su soberanía y una garantía para su comercio. El SMS Hansa fue el primer blindado construido en astilleros germanos y pasó la mayor parte de su vida útil en el exterior, protegiendo el comercio alemán. El SMS Preussen fue el primer buque de guerra teutón construido por un astillero privado – el astillero AGVulcan, en Sttetin[xvii] – , patrulló el Mediterráneo oriental durante la guerra ruso – turca (1877 – 1878) y participó en la ceremonia de transferencia del archipiélago de Heligoland al Imperio en 1890. La obra formativa de Von Stosch (1872 – 1882) y su sucesor, el general Leo von Caprivi (1883 – 1888) fue sumamente exitosa y, a fines de 1880, Alemania era la tercera potencia naval de Europa, solo superada en número de unidades por Rusia y la Gran Bretaña[xviii].

Además de crear de una armada, Alemania emprendió la tarea de dotarse de una continuidad litoral entre el Mar Báltico y del Mar del Norte y una plataforma de proyección sobre el Mar del Norte, el archipiélago de Heligoland[xix]. El primer objetivo se alcanzó con la construcción del Canal de Kiel. Las obras se iniciaron en Holtenau, cerca de Kiel, el 3 junio de 1887 y concluyeron ocho años después, el 20 de junio de 1895. El canal medía 62 metros de ancho en la superficie y 22 en el fondo, 9 de profundidad; en honor al monarca que inició el proyecto – Guillermo I, rey de Prusia y primer emperador de la Alemania unida – se le denominó Káiser Wilhem Kanal. No era la primera vez que se vinculaba el Mar Báltico y el Mar del Norte a través de un canal, pero sus predecesores eran, comparativamente, obras modestas. Así, pues, del Canal de Kiel se dijo que era una muestra “del orgullo alemán, pletórico de facultades de invención e imaginación, de iniciativa y de recursos, una audacia avisada y complaciente a la que se rinde homenaje y se sirve de una potencia industrial de primer orden y de personal altamente calificado[xx]”. Asimismo, la adquisición del archipiélago de las Heligoland (1890) – fruto del cuidado que puso el canciller Bismarck en las relaciones diplomáticas con Gran Bretaña – consolidó el dominio marítimo alemán y le dotó de una proyección al Mar del Norte.

3. La influencia de Mahan (1890 – 1897)

En 1888, al iniciar su reinado, el Káiser Guillermo II (1859 – 1941) declaraba con seguridad que “Al Imperio Alemán no le es menester nueva gloria militar ni conquistas, ahora que ha ganado el derecho a vivir como nación unida e independiente”. Esta prudencia fue decayendo a partir de 1890, tras la dimisión de Bismarck a la Cancillería del Reich. El voluntarioso emperador cayó bajo el influjo de las ideas de Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840 – 1914), autor del libro que se consideró como el más influyente de la última década del siglo XIX, “La influencia del poder marítimo en la Historia: 1660 – 1788”. La obra era una compilación de las clases dictadas por el marino norteamericano en la Academia de Guerra Naval de los Estados Unidos.

Mahan señalaba que el control de los mares era el factor más importante para la prosperidad nacional a lo largo de los siglos y que los componentes del poder marítimo de una nación eran los factores geográficos, los recursos naturales, el carácter nacional, el espíritu de su gobierno y su política naval y diplomática. Asimismo, deducía varios principios estratégicos relacionados con la concentración de fuerzas, la correcta elección del objetivo y la importancia de las líneas de comunicación. “La influencia del poder marítimo en la Historia: 1660 – 1788” resumía las razones por las qué una nación debía contar con una Armada cuyo principal objetivo fuera el tener la capacidad suficiente para destruir una flota de guerra enemiga. En Alemania “La influencia del poder marítimo en la Historia: 1660 – 1788” tuvo un gran éxito, constituyéndose el káiser Guillermo II (1859 – 1941) en su mayor propagandista, llegando a decir de él que “No estoy leyendo sino devorando el libro de Mahan y trato de aprovecharlo con el corazón y con la mente. Es un trabajo de primera clase y clásico en todos sus puntos. Está a bordo de mis barcos y es constantemente consultado por mis almirantes y oficiales”.

Sin embargo el Segundo Reich no encajaba con la geografía política que proponía el autor norteamericano. Y es que, tal como decía Kllejen, “Alemania era, en la constelación europea, la menos independiente de todas las potencias mundiales[xxi]”. Consciente de ello, Bismarck se había ocupado de mantener un equilibrio estratégico europeo en beneficio de la prosperidad y estabilidad de Prusia – Alemania y de la dinastía Hohenzollern. Así, al oeste contenía a los franceses y mantenía buenas relaciones con los británicos y, al este, era sumamente cuidadoso y hasta cordial con los rusos. Dicha política exterior le había permitido fortalecer la posición del Reich, dotándole de una costa continua y de una salida independiente al Mar del Norte. Conservador de corazón, Bismarck había dado autonomía al general Von Stosch en el desarrollo del primer programa naval (1872 – 1882), sabiendo que pondría énfasis en la construcción de una Armada protectora del comercio germano y no en experimentos para los cuales Alemania no estaba en condiciones de asumir por falta de recursos políticos[xxii] y económicos[xxiii]. Von Stosch eludió estos escollos y apostó por el torpedo como nivelador de las pequeñas y grandes armadas. Esta nueva arma, desarrollada por el ingeniero británico Robert Whitehead (1823 – 1905) con el apoyo de capitales austro – húngaros, respondía a la pregunta sobre cómo una marina modesta podía defenderse de una armada más poderosa.

4. La daga en la garganta de Inglaterra

El programa de torpedos de la Armada Imperial estaba en manos de un oficial quien había sido influenciado hondamente por las ideas de Mahan, Alfred Tirpitz (1849 – 1930). A pesar de haber sido promovido por Von Stosch, Tirpitz cuestionaba la misión que le había impuesto Von Stosch a la Marina Imperial. Para Tirpitz “la bandera debía seguir los pasos del comercio, como otros países habían visto antes de que nosotros nos diéramos cuenta[xxiv]”. Así, al asumir el cargo de Secretario de Estado en el despacho de la Administración Naval Imperial en junio de 1897, Tirpitz dio un golpe de timón presentando al káiser el proyecto de una gran flota de combate cuya realización implicaba graves consideraciones políticas y diplomáticas, porque constituía un peldaño más en la escalada de militarización de la política exterior y de seguridad nacional. Construir una gran flota era entrar en competencia directa – y, eventualmente, en conflicto abierto – con la Gran Bretaña por “el lugar bajo el sol”[xxv] que, según Tirpitz, le negaban los británicos a los alemanes.

Tirpitz pensaba que el flanco estratégico más desprotegido de los británicos era el Mar del Norte. La Marina Real privilegiaba el teatro de operaciones del Mediterráneo y el despliegue de sus unidades como gendarmes de las colonias y el comercio británico. Según Tirpitz, los británicos negociarían con Alemania un acuerdo sobre construcciones navales con el fin de mantener su presencia naval en el Mediterráneo y del resto del mundo. Por ello la Gran Flota Alemana debía ser una fleet in being (escuadra en potencia), es decir, una amenaza constante a la hegemonía naval británica. En medios periodísticos esta estrategia recibió un nombre más amenazante y perturbador, “la daga en la garganta de Inglaterra” que la prensa británica asumió y utilizó para advertir al gobierno y al pueblo del peligro alemán y de la complaciente política de esplendido aislamiento frente a los asuntos europeos.

La estrategia de Tirpitz se fundaba en supuestos erróneos. El Reino Unido no vaciló en responder al reto e inició un programa naval que duplicó en una década la tasa de construcciones navales alemanas y reorganizó su sistema de defensa global gracias al apoyo político y económico de sus dominios, Canadá, Australia, Nueva Zelanda, la India y África del Sur. En vísperas de la Gran Guerra, Inglaterra había triplicado su ventaja en el juego de correlación de fuerzas. En Alemania echaban raíces las dudas sobre la capacidad de la Armada Imperial para enfrentar a la Royal Navy y la validez de la idea de pretender hacer la guerra contra Inglaterra[xxvi]. La guerra ponía en peligro la prosperidad alcanzada por la marina mercante alemana. La divisa de la compañía naviera Hamburg – Amerika – Line – “mi campo es el mundo” – era una realidad de la que se enorgullecían todos los alemanes. Su director Albert Ballin (1857 – 1918) era consejero del káiser y mediador en las sombras en las crisis diplomáticas entre Inglaterra y Alemania gracias a su amistad con el consejero privado del rey Eduardo VII (1841 – 1910), sir Ernst Cassel (1852 – 1921). Siendo el principal armador de Alemania, Ballin temía por la seguridad de la flota mercante alemana y la pérdida de su posición preeminente en el comercio mundial. En 1914 era Inglaterra quien tenía preparada la daga para, cuando estallara la guerra, encajarla en la garganta de Alemania a través de un bloqueo a distancia aprovechando las desventajas geográficas del litoral germano. Asimismo, su presencia naval global borraría del mapa los buques mercantes alemanes[xxvii].

5. Tiempo de pruebas

En vísperas de la Gran Guerra la Flota de Alta Mar Alemana se encontraba en una situación política sumamente complicada. Tras una década del gozar el favor imperial (1897 – 1908), las críticas comenzaron a llegar de todos los sectores políticos, incluso entre los nacionalistas que veían en el almirante Tirpitz encarnados todos los defectos de un estamento político – militar débil, elitista, ciego a las demandas de la nación y reaccionario. Las críticas más feroces venían del grupo que había sido el puntal del programa de Tirpitz, la Deutscher Flottenverein[xxviii] (Liga Naval Alemana) (DFV). Era irónico que esta institución, creada como freno al parlamentarismo y al Partido Social Demócrata (SPD), pasara a ser una feroz opositora de Tirpitz. El nacionalismo que había insuflado y sostenido la construcción de la Armada Imperial se escapaba del control del Reich. El SPD aprovechó la crisis de confianza en Tirpitz para cuestionar la política global del káiser y del nacionalismo y ganar predicamento más allá de su electorado tradicional, la clase trabajadora.

Atrapada entre dos fuegos, el nacionalismo desbocado y la prédica pacifista y antiimperialista del SPD, la Armada Imperial fue señalada por unos de bajar la cabeza ante los británicos y, por otros, de ser la responsable de las tensiones diplomáticas anglo – alemanas. La guerra estalló en plena crisis de credibilidad y ante ella el alto mando naval no tuvo otro camino que el de la improvisación. En este marco, “Alemania vio en el submarino un rayo de esperanza en el acoso mundial a que se encontraba sometida y apeló a él como pudo apelar al rayo de la muerte[xxix] si éste se hubiese inventado. Los aliados disponían de la hegemonía marinera tal y como se entendía hasta entonces, en el concepto clásico de la guerra marítima, de la guerra que hasta entonces era guerra plana. El submarino era la guerra en el espacio, completando el avión esta transformación que no es que origine una guerra nueva, como creen, o fingen creer, unos cuantos futuristas, pero que desde luego introduce otras modalidades como ha acaecido siempre desde que un arma o un adelanto sensacional ha cambiado los puntos básicos del planteamiento del problema[xxx]”.

Asimismo, Alemania se lanzó a una guerra de guerrillas en el mar (Kleinkriegs) utilizando corsarios cuyas hazañas y desventuras constituyen episodios apasionantes del desarrollo de la guerra naval como la del Westburn, en el Archipiélago Canario, en aguas españolas, es decir, en territorio de un estado neutral. Sobre ella, El Comercio informaba el 02 de junio de 1916 lo siguiente: “Acaba de llegar el vapor inglés Westburn, izando la bandera de guerra alemana, bajo el mando del oficial de marina Badewitz, llevando a bordo las tripulaciones de los vapores ingleses “Flamenco”, “Horace”, Edimborough”, “Clan Mactavish” y el belga “Luxemburg”, todos hundidos por el comandante alemán. El “Westburn”, cargado de carbón, fue apresado en su viaje de Inglaterra a Buenos Aires. Las tripulaciones de los cinco vapores serán puestas a disposición de sus respectivos cónsules.

El “Westburn” entró en el puerto de Santa Cruz [de Tenerife], mientras que un crucero inglés se hallaba anclado en la rada. Es de grandísimo interés hacer constar el hecho de que el vapor que acaba de fondear en [Santa Cruz de] Tenerife, tenía 199 prisioneros ingleses, mientras que la tripulación estaba constituida por sólo siete alemanes (…)

Mientras las tripulaciones de los barcos alemanes surtos en el puerto aclamaban a la heroica tripulación del “Westburn”, en cuyo palo mayor había sustituido la bandera británica por el pabellón alemán, abandonó la bahía el crucero inglés HMS “Sutlej”, cuya situación resultaba un poco ridícula. El “Sutlej” quedó vigilando, fuera de la bahía, en espera de que al transcurrir las veinticuatro horas de su entrada, en Tenerife, abandonará el puerto el “Westburn”, para entonces cazarlo o hundirlo a cañonazos (…)

Al cumplirse las veinticuatro horas de su llegada al puerto, el “Westburn”, a cuyo bordo no quedaba ni uno solo de los tripulantes y pasajeros que traía prisioneros, levó anclas y enfiló la salida del puerto. Los muelles y las alturas estaban repletos de curiosos que se disponían con gemelos y anteojos de largo alcance a presenciar qué iba a ocurrir en el mar tan pronto como el crucero “Sutlej” pudiese atacar a los corsarios alemanes.

El “Westburn”, con su corta tripulación germana, y arbolando el pabellón de guerra del imperio, salió valientemente fuera de la bahía. La expectación era extraordinaria, se había tocado zafarrancho de combate. Tan pronto como salió a la mar, el crucero británico se puso en movimiento para darle caza. El oficial alemán, que con sus siete hombres iba a bordo del “Westburn”, no se proponía escapar. Antes, al contrario, puso proa en demanda del enemigo y hacia él dirigió el buque capturado. Se detuvo entonces el crucero y rectificando su rumbo parecía aceptar el reto de los alemanes. Todo el mundo esperaba el primer cañonazo cuando, al costado del “Westburn”, se destacó un bote, en el que iban los marinos alemanes. El crucero inglés avanzó entonces, forzando la máquina pero una violenta y larga explosión a bordo del “Westburn” dio a entender a los marinos ingleses que se habían burlado de ellos nuevamente volado la presa en sus mismas narices. Los valerosos germanos ganaron rápidamente el puerto de Tenerife entre las aclamaciones de todos los que presenciaban la hazaña, Allí afuera quedaban los marinos ingleses devorando su fracaso. Los alemanes desembarcaron en el muelle, y seguidos del público que les felicitaba se presentaron antes las autoridades[xxxi]”.

No es nuestra intención ocuparnos del combate de Jutlandia (31 de mayo – 1 de junio de 1916), basta decir que fue un choque inútil: los británicos no aniquilaron a la Flota de Alta Mar Alemana y, ésta, a su vez, no pudo romper el bloqueo británico y justificar su existencia. Un comentarista español contemporáneo, Mariano Rubio y Bellve, concluía que “El problema en el mar queda planteado, después de la batalla, en los mismo términos que antes que ella. Solamente la muerte, con numerosas víctimas de la horrible tragedia de Jutlandia, es la que ha triunfado en toda línea[xxxii]”. Evidentemente Alemania reclamó para sí el resultado del combate como una victoria táctica, pero lo cierto es que no había variado la situación estratégica de Alemania. Un corresponsal del Daily Telegraph la resumía así: “La verdad es que, como isleños, no ignoramos lo que son los mapas de guerra, pero damos más importancia a los mapas sancionados por el tiempo. Olvida Von Bethmann – Hollweg que cerca de tres cuartas partes de la superficie de la Tierra están cubiertas de agua. Cuando se iniciaron las hostilidades, comenzaba una lucha mundial para los alemanes, que habían demostrado actividad en los mares y estaban practicando o preparando operaciones guerreras no sólo en cada de uno de los continentes, sino también en todos los países del globo. Para los germanos esto no es ya actualmente una guerra mundial. Alemania se halla casi tan completamente aislada del mundo exterior, como París en 1870. Aunque Alemania haya gastado 7,250 millones de francos en su Marina, y aunque tenía la primera marina mercante del mundo después de la británica, sin embargo la bandera germana ha desaparecido del mar, resultado singular para una nación marítima.

Durante varios siglos la guerra marítima, en la que se hallaron comprometidas las flotas de España, Holanda y Francia, nunca ocurrió que no mostraran sus banderas en el mar; pero la marina mercante alemana ha desaparecido; la marina de guerra está inactiva, el comercio transatlántico ha cesado y han desaparecido las colonias. Alemania no ha alcanzado victorias como las conseguidas por Napoleón en 1811, pero Trafalgar preparó Waterloo. El canciller alemán debe leer la vida de Napoleón[xxxiii]”.

La Hochseeflotte no tendría una segunda oportunidad de medir fuerzas con la Royal Navy. Sus pérdidas habían sido menores que las británicas, pero eran irremplazables. Ya no podía disputar el dominio del mar. Al respecto escribió Mateo Mille: “Pero Alemania no era una nación naval; la formidable potencia creada por el almirante Von Tirpitz, organizador genial al amparo de una industria colosal, no fue empleada adecuadamente[xxxiv]”.

En el invierno boreal 1916 – 1917 la moral de la flota se fue a pique. Como todos los alemanes, el fracaso de la cosechas hizo más severo el racionamiento alimentario. Las magras raciones potenciaron elementos como la inactividad, las rutinas sin sentido y el desprecio de los oficiales. En junio de 1917 una manifestación contra los privilegios alimentarios de los oficiales se tornó en una plataforma política a favor de una paz negociada. Los líderes del comité de marinos fueron detenidos. Dos de ellos fueron fusilados[xxxv]. En julio un alzamiento armado en las bases navales de la costa de Flandes dejó un saldo de cincuenta oficiales asesinados y la destrucción de las instalaciones de los zeppelines. Su líder, el segundo teniente Rudolf Glatfelder, declaró después, ya a salvo en Suiza, que este hecho probaba la capacidad de los alemanes para rebelarse[xxxvi]. En diciembre el desacato a la orden de reembarque de la dotación de buques de vigilancia que acababan de regresar de una larga y sangrienta patrulla degeneró en motín que fue develado con un saldo de cuarenta y cuatro muertes. Los sobrevivientes fueron condenados a trabajos forzados[xxxvii].

El descontento también cundía en el cuerpo de oficiales. Von Tirpitz hubo de renunciar a la Secretaria de Marina en marzo de 1916, a causa de su postura favorable a la guerra submarina irrestricta[xxxviii]. Pocos meses después se convirtió en co – fundador del Partido de la Patria Alemana (DVP), un movimiento político nacionalista opuesto a una paz negociada. Corría el año 1918 y el poder real – el gobierno que apoyaban Von Tirpitz y sus correligionarios – era el de los caudillos del pueblo alemán, el mariscal de campo Paul von Hindenburg y el general Erich Ludendorff. En mayo de 1918 corrían fuertes rumores sobre la existencia de círculos secretos de oficiales conspirando contra Von Capelle y Scheer, con el fin de sacar de los puertos a la Hochseeflotten y combatir contra los ingleses[xxxix]. A finales de julio el crítico naval del Berliner Tageblatt, capitán de navío (r) Karl Ludwig Lothar Persius (1864 – 1944) declaraba abiertamente el fracaso de la guerra submarina[xl].

El 29 de setiembre de 1918 el alto mando del Ejército alemán reclamó al gobierno imperial el inicio de negociaciones para un armisticio con los aliados. Cuatro días después el nuevo gabinete, con el príncipe Max de Baden a la cabeza[xli], enviaba una nota al gobierno de los Estados Unidos solicitando el armisticio sobre la base de los Catorce Puntos del presidente Woodrow Wilson.

Entretanto el ejército y la marina imperial se ocupaban de los efectos de la derrota. El alto mando militar hábilmente inició una campaña de propaganda entre las tropas del frente. Esta fue el origen del mito de la “puñalada por la espalda”, en el cual se apoyarían los partidos de extrema derecha durante la República de Weimar, en particular los nacionalsocialistas. Entre la oficialidad naval las células nacionalistas clandestinas salieron a la luz y, en contra de la voluntad de paz del gobierno Baden, sus integrantes dictaron las órdenes pertinentes para el alistamiento de la Flota para forzar el combate decisivo contra la Armada británica. El 28 de octubre la marinería de Kiel y Wilhelmshaven se amotinaron, utilizando como pretexto el nivel crítico al que había llegado el racionamiento de las dotaciones. Cinco días después Kiel – la capital de la Armada imperial – era escenario de manifestaciones en las que se exigía, además de la mejora del rancho, la reforma política y la libertad de los encarcelados por los motines de 1917. El temor de que el motín fuese develado a sangre y fuego, al estilo de la sublevación en Flandes, ocurrida el verano pasado, dio motivo a los amotinados para armarse y organizarse en soviets. Así, pues, el pabellón imperial fue arriado e izada la bandera roja. El motín fue controlado por la moderación de las autoridades navales y la intervención del diputado socialista Gustav Noske, hombre de autoridad y sentido práctico. No hubo violencia contra los oficiales y los amotinados fueron licenciados, dispersándose por toda Alemania. Guillermo II seguía los acontecimientos desde el cuartel general del Ejército Imperial en Spa (Bélgica). Conmocionado, declaró que ya no tenía una marina y abdicó. En aquella hora amarga Guillermo II dijo: “Espero que esto será en beneficio de Alemania. No desesperemos por el porvenir”. Una vez más se había repetido un viejo axioma sobre los motines navales: estos se producen en las flotas que permanecen ancladas en puerto, y son mayormente consecuencia de una derrota.

6. Ocaso

El 15 de noviembre de 1918 el almirante alemán Hugo Meurer (1869 – 1960) firmaba con su par británico, Jellicoe, las clausulas del acuerdo de internamiento de la flota imperial. Tres días después el almirante Ludwig von Reuter (1869 – 1943) asumía el mando de la escuadra de buques destinados al internamiento provisional en Escocia. Conformada por diez acorazados, siete cruceros ligeros y cincuenta destructores, su derrota hacia Escocia tuvo un aire que recordaba tiempos convulsos, pues cada buque ondeaba dos enseñas, la imperial a popa y la bandera roja en el palo de proa. El lugar definitivo de internamiento fue Scapa Flow, la base de la Grand Fleet británica, en el archipiélago de las Orcadas. Durante las negociaciones del Tratado de Versalles los buques permanecieron fondeados y severamente custodiados, a tal punto que sus tripulaciones se encontraban incomunicadas y prohibidas de tocar tierra.

En vísperas de la culminación de las negociaciones de paz en París, a fines de junio de 1919, el Times de Londres informaba que los aliados habían acordado exigir a Alemania la entrega de los buques internados a través de un arreglo financiero. En caso que la respuesta germana fuera negativa, correrían tres días de plazo para la denuncia del armisticio del 11 de noviembre de 1918 y, con ello, la reanudación de hostilidades. Con la convicción que el destino de la flota internada era la de trofeo de guerra, el almirante Von Reuter activó el plan de hundirla. Aprovechando un descuido de sus custodios, los alemanes abrieron los grifos de fondo de los buques y arriaron los botes salvavidas. En cinco horas se fueron a pique diez acorazados, cinco cruceros de batalla, cinco cruceros ligeros y cuarenta y cuatro destructores. Un crucero de batalla, cuatro cruceros ligeros y catorce destructores fueron embarrancados por personal británico. Ludwig von Reuter había protegido, in extremis, el honor de la flota[xlii].

La Hochseeflotte pudo haber tenido un final diferente si se hubiera prolongado la guerra. En setiembre de 1917, el almirante David Beatty (1871 – 1936), comandante de la Gran Flota, autorizó un audaz plan según el cual 121 aviones del Real Servicio Aéreo Naval (RNAS) destruirían la Hochseeflotte y sus bases de Kiel y de Wilhemshaven[xliii]. Los torpederos despegarían desde porta aeronaves – – y los hidroplanos – bombarderos desde sus bases del Canal de la Mancha. Este plan de ataque sirvió de modelo para el bombardeo de la flota italiana surta en Tarento, Sicilia, el 11 de noviembre de 1940.

7. A modo de conclusión

En su biografía de juventud “Historia de un alemán. Memorias 1914 – 1933” el periodista alemán Sebastian Haffner (1907 – 1999) escribió: “Esta enfermedad – el nacionalismo – que en otros casos sólo afecta el aspecto externo, en el suyo – los alemanes – les carcome el alma (…) Un alemán que cae víctima del nacionalismo deja de ser alemán, apenas es persona. Y lo que este movimiento genera es un imperio alemán, quizás incluso un gran imperio alemán o un imperio pangermánico y la consiguiente destrucción de Alemania”. Considero que esta reflexión personal de Haffner puede aplicarse a la existencia de la Marina Imperial alemana. Su carácter nacionalista debe comprenderse como una imitación del sentimiento nacional de los ingleses y franceses de su época[xliv]. Al imitar se corre el peligro de tomar los defectos ajenos[xlv]. ¿Necesitaba Alemania una Armada como la concebida por la ambición del almirante von Tirpitz? Creemos que no. Incluso el káiser Guillermo II (1859 – 1941) declaró, en un momento de lucidez, que la seguridad del Imperio no descansaba en nuevas conquistas[xlvi]. En 1871 Alemania había ganado el derecho a vivir como nación unida e independiente. En 1888 contaba con una Armada digna de respeto, garantía de su soberanía e, incluso, con un modesto imperio colonial. En 1918 Alemania perdió todo lo ganado y sus marinos se amotinaron para salvar sus vidas, porque no querían ser sacrificados en un combate inútil[xlvii]. En cuanto a Scapa Flow, este hecho fue una tragedia redentora para una Armada destruida moralmente. El almirante Von Reuter y sus oficiales demostraron que todo se había perdido, menos el honor.

Scapa Flow fue el último acto de un fracaso que se recuerda con una cita churchilliana, “la flota alemana es un lujo, no una necesidad nacional”. Creemos que dicha frase es equívoca. Al dotarse de una Armada poderosa, Alemania demostró su voluntad de ser un pueblo fuerte y con vocación marítima. Equívocamente se creyó que la libertad de los mares sólo podía alcanzarse por medio de la fuerza. Aquel dogma era propio de la época y la derrota alemana probó su falsedad arrastrando en su magnitud a su poderosa adversaria, Inglaterra, a la luz del impacto humanitario que provocó el bloqueo de las costas alemanas. El orgullo y la ambición desmedida fueron la perdición de la Marina Imperial Alemana. Sus virtudes fueron el valor y la pericia de los tripulantes de submarinos, destructores y cruceros auxiliares. Aquellos que servían a bordo de los dreadnoughts y cruceros de batalla no tuvieron la oportunidad de demostrar su calidad. La obra de construir una flota como la Armada Imperial fue extraordinaria. En ella vemos la maestría y las debilidades de sus artesanos, Von Stosch, Von Caprivi y Von Tirpitz.

REFERENCIAS

[i] “But we are victors and vanquished at one and at the same time, and in depicting our success the difficult problem confronts us of not forgetting that our strength did not last out to the end”

[ii] Desde los tiempos de Julio César Germania – Alemania fue considerada más que un pueblo, una vasta comunidad que habitaba en un territorio pobre y peligroso.

[iii] Serie de motines, sublevaciones e insurrecciones que estallaron en toda Europa, en las que se mezclaron motivos políticos, sociales y nacionales que puso fin al predominio del absolutismo en el continente europeo desde el Congreso de Viena de 1814 – 1815. Se inició el 12 de enero de 1848 en Reino de las Dos Sicilias y llegó a Prusia dos meses después, extendiéndose por toda Alemania a partir del mes de mayo, con la constitución del Parlamento Federal de los Estados Alemanes. La asamblea se dividió entre los representantes partidarios de la Gran Alemania (con Austria) y los de la Pequeña Alemania (sin Austria). Si bien la Asamblea se desintegró el 28 de abril de 1849, a causa de la negativa del rey de Prusia, Guillermo IV, de aceptar la corona imperial de una asamblea revolucionaria, dejó claramente planteada la cuestión de la unidad alemana bajo la hegemonía prusiana o austriaca.

[iv] El término Reich procede de una fusión ecléctica del Rix celta y el Rex latino, razón por la que se tradujo como imperio.

[v] FYFFE, Charles Alan (1845 – 1892), Historiador y periodista británico, corresponsal del Daily News durante la guerra franco – prusiana.

[vi] DOMINGUEZ RODIÑO, Enrique (1918, 13 de marzo), “Las Grandes Potencias: Alemania V”, La Vanguardia, Barcelona, p. 12

[vii] TENBROCK, Robert Hermann, “Historia de Alemania”, Paderborn: Hueber – Schöning, 1968, 344p, p. 218

[viii] PARK, Evan (2015), “The Nationalist Fleet: Radical Nationalism and The Imperial German Navy from Unification to 1914”, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Volume 16, issue2, p. 125 – 159, p. 136

[ix] KLLEJEN, Johan Rudolf ((1864 – 1922), Geógrafo, politólogo y político sueco. Fue catedrático de ciencias políticas y estadística de las universidades de Gotemburgo y de Upsala. En 1899 acuñó el término “Geopolítica”.

[x] DOMINGUEZ RODIÑO, Enrique, (1918, 6 de febrero), “Las Grandes Potencias: Alemania II”, La Vanguardia, sección “La Guerra Europea”, p. 9

[xi] “Sólo en la Guerra se forja una nación. Sólo las grandes acciones comunes en nombre de la patria unen a la Nación. El individualismo cede y el individuo se difumina y se convierte en parte de un todo” – Heinrich von Treistchke

[xii] Online edition of Admiral Reinhard Scheer’s WW1 memoirs, published in 1920 http:// www.richthofen.com/scheer

[xiii] Esta frase, según el filosofo e historiador romano Plutarco (46/50 DC – 120 DC), había sido pronunciada por el caudillo Pompeyo (106 AC – 48 AC) arengando a sus marineros a embarcarse a pesar del amenazador estado de la mar, recordándoles que el deber está por encima de cualquier miedo o de cualquier circunstancia.

[xiv] La Reichsflotte (Flota Imperial) fue la primera marina unificada alemana. Fue creada el 14 de enero de 1848 por la Asamblea Nacional Alemana de Fráncfort, con el fin de contar con una fuerza naval en la Primera Guerra de Schleswig (1850 – 1852) contra Dinamarca. La fecha de su creación se considera, simbólicamente, como el inicio de la Armada alemana moderna. Ver: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reichsflotte

[xv] PARK, Evan (2015), “The Nationalist Fleet: Radical Nationalism and The Imperial German Navy from Unification to 1914”, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Volume 16, issue 2, p. 125 – 159, p. 131 – 132

[xvi] “Necesitamos buques que sean apropiados para proteger a la marina mercante ofensivamente y escuadrones que estacionemos para fines de policía en lugares distantes. Considero que los acorazados son un error; son superfluos para nuestras condiciones porque no podemos combatir en un combate de largo aliento” – Albert von Stosch

[xvii] Actualmente Szczecin, Polonia

[xviii] El artículo 53 de la Constitución Imperial de 1871 decía que la Marina del Imperio se encontraba al mando del Emperador, correspondiéndole ocuparse de su organización y composición.

[xix] RUBIO Y BELLVE, Mariano (1916, 22 de octubre), “El Canal de Kiel”, La Vanguardia, Sección “La Guerra Europea”,

[xx] « Des facultés d’invention et d’imagination, un esprit d’initiative et de ressources une hardiesse avisée et souple auxquels il faut rendre hommage, servis admirablement par une puissance industrielle de premier ordre (…) et le dévouement passionné d’un personnel d’élite » GRANDHOMME, Jean – Noel, « Du pompon à la plume: l’amiral, commentateur de la guerre et de la paix d’inquiétude, 1914 – 1919 », Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains, 2007/3 Nº227, p.43 – 64 DOI :10.3917/gmcc.227.0043, p. 53

[xxi] DOMINGUEZ RODIÑO, Enrique, (1918, 6 de febrero), “Las Grandes Potencias: Alemania II”, La Vanguardia, sección “La Guerra Europea”, p. 9

[xxii] La ventaja de contar con el favor imperial constituyó, a la larga, al problema para la consolidación de la cadena de comando de la Armada.

[xxiii] A diferencia de Inglaterra, la Alemania imperial nunca tuvo un apoyo tributario que le permitiera con una fuente de financiación estable y permanente de su Armada. La Royal Navy disfrutaba de los ingresos producidos por una serie de impuestos y tasas al comercio colonial .

[xxiv] SCHEER, Reinhard (1920), “Germany’s High Seas Fleet in the World War”, Cassell & Co,, p. 176

[xxv] Esta frase es el elemento central del discurso del ministro de relaciones Exteriores, Bernhard von Bülow, del 6 de diciembre de 1897, en el cual anunció el golpe de timón de la política exterior alemana, de la política europea de Bismarck (europapolitik) a la global del káiser Guillermo II (Weltpolitik), es decir, del balance de poderes en Europa a la expansión mundial del poderío alemán.

[xxvi] En sus memorias Tirpitz niega que su intención fuera ir a la guerra contra Inglaterra. Por lo contrario, señala que la Armada Imperial tenía un carácter defensivo contra las intenciones bélicas de los británicos, amén de darles unas cuantas lecciones en política internacional.

[xxvii] La Vanguardia (29 de noviembre de 1914), página 16, segunda columna: “Londres, 28 – La Oficina de Trabajo ha publicado a los efectos de la guerra sobre las marinas mercantes inglesa y alemana. De dicho informe se desprende que el 97 por cien de los buques ingleses siguen prestando servicios mientras el 89 por cien de los alemanes han dejado de prestarlo, y que la mayoría de los que navegan son pequeños buques de cabotaje”

[xxviii] Fundada en 1898, la DFV – se definía “como una muestra de concordia entre el trabajador y el príncipe, la izquierda y la derecha, el norte y el sur, un movimiento popular fundado en el amor a la patria, sin distinción de ideas políticas y religiosas ni barrera social alguna”.

[xxix] El rayo de la muerte o rayo de tesla es un arma que permite disparar un haz de partículas microscópicas hacia seres vivos u objetos para destruirlos. Supuestamente fue inventado entre la década de 1920 y 1930 de manera independiente por Nikola Tesla, Edwin R. Scott y Harry Grindell Matthews, entre otros. El aparato nunca fue desarrollado, pero ha alimentado la imaginación de muchos autores de ciencia ficción y ha inspirado la creación de conceptos como la pistola de rayos láser, utilizada por héroes de ficción como Flash Gordon. Ver: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rayo_de_la_muerte

[xxx] MILLE, Mateo, “Historia Naval de la Gran Guerra 1914 – 1918”, Barcelona: Inédita Editores, SL, 2010, 548 p., p. 123

[xxxi] El Comercio (02 de junio de 1916), edición de la mañana, página 4, tercera y cuarta columnas

[xxxii] RUBIO Y BELLVE, Mariano (1916, 11 de junio), “En el mar”, La Vanguardia, sección “La Guerra Europea”, p. 14, 1 – 4 Col.

[xxxiii] La Vanguardia, (29 de mayo de 1916), página 6, tercera columna

[xxxiv] MILLE, Mateo, “Historia Naval de la Gran Guerra 1914 – 1918”, Barcelona: Inédita Editores, SL, 2010, 548 p., p. 11

[xxxv] PATERSON, Tony, (2014, 17 de junio), “A History of the First World War in 100 moments: My dear parents, I have been sentenced to death…”, The Independent

[xxxvi] La Vanguardia (20 de octubre de 1917), página 13, primera columna

[xxxvii] La Vanguardia (26 de enero de 1918), página 9, tercera columna

[xxxviii] El Comercio, (23 de marzo de 1916), edición de la mañana, página 1, tercera y cuarta columnas

[xxxix] La Vanguardia, (18 de mayo de 1918), página 9, cuarta columna

[xl] La Vanguardia (28 de julio de 1918), página 13, primera columna

[xli] El 03 de octubre de 1918 marca el inicio de una de serie de gobiernos concebidos entre cábalas y motines. La política alemana no se estabilizó hasta el año 1922, tras el asesinato del ministro de relaciones exteriores, el industrial Walter Rathenau (1867 – 1922). Su muerte unió, brevemente, a la mayoría silenciosa contra los radicalismos políticos.

[xlii] Fue testigo de estos hechos Claude Stanley Choules (1901 – 2011), el último de los últimos veteranos británicos de la Primera Guerra Mundial

[xliii] WILKINS, Tony (2015, 03 de agosto), “World War I’s abandoned Pearl Harbour Attack”, Ver: http://defence of the realm.wordpress.com/2015/03/08/world-war-Is-abandoned-pearl-harbour-attack/

[xliv] “Repróchese a los alemanes el que imiten unas veces a los ingleses y otras a los franceses, pues es lo mejor que pueden hacer. Reducidos a sus propios medios nada sensato podrían ofrecernos”.

[xlv] “¡Bienaventurados nuestros imitadores, porque de ellos serán nuestros defectos!” – Jacinto Benavente, dramaturgo español (1866 – 1954)

[xlvi] Al Imperio Alemán no le es menester nueva gloria militar ni conquistas, ahora que ha ganado el derecho de vivir como nación unida e independiente” – Guillermo II (1888)

[xlvii] “Alemania en sí no es nada, pero cada alemán es mucho por sí mismo” – Goethe (1808)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

☕Amaneció en mi escritorio, ¿es un aviso? 📖Paleografía: MAYATL Grafía normalizada: mayatl Tipo: r.n. Traducción uno: Scarabée ou coléoptère de couleur verte. Traducción dos: scarabée ou coléoptère de couleur verte. Diccionario: Wimmer Contexto: mayâtl Scarabée ou coléoptère de couleur verte. Insecte de couleur verte. Launey II 240 note 175. Hallorina duguesi. Sah Garibay IV 101. Mexicanisme: mayate. Diccionario de Mexicanismos. Santamaria. Description. Sah11,101. Illustration. Dib.Anders. XI fig.356. " inic tlachîuhtli tlatzauctli îca in mayâtl xoxoctli ", il est fait ainsi, il est encollé de scarabée verts - ist in folgender Weise hergestellt: Er ist mit einem Mosaik von grünen Käfer (flügeln) bedeckt. Acad Hist MS 68,69 §8. SGA II 547. Cf. également ECN10,158 qui traduit: they are made of a mosaic of green beetles (yn mayatl xoxocti). Beetle = coléoptère. R.Siméon dit 'escarbot ailé de couleur verte' (Clav.). Escarbot = nom commun de divers coléoptères, en particulier l'hister. Fuente: 2004 Wimmer Entradas mayatl - En: 1571 Molina 2 mayatl - En: 1580 CF Index mayatl - En: 1780 Clavijero mayatl - En: 2004 Wimmer Descomposición maya-tl Palabras maya maya + mayahua mayahualoa mayahuel mayahui mayahui + mayahuia mayahuilia mayahuiliztli mayahuini mayahuini + mayahuito mayahuiz mayamanqui mayamiqui mayampoloa mayan mayana mayanacochtli aaccayotl ac mach tlacatl acacalotl acacapacquilitl acacatl acachachacatl acachatl acachiquihuitl acacocoyotl acacoyotl acacuahuitl acacueyatl acacuiyatl acahuatototl acaiyetl acalcuachpancuahuitl acalcuachpanitl acalcuauhyollotl acalmaitl acalpatiotl Paleografía maiatl - En: 1580 CF Index Traducciones XI-101 - En: 1580 CF Index Mayate, cierta especie de escarabajo verde - En: 1780 Clavijero cierto escarauajo que buela. - En: 1571 Molina 2 Scarabée ou coléoptère de couleur verte. - En: 2004 Wimmer https://www.instagram.com/p/CeviT4EOp9yyyU970GbyyC2byvKIrll9pNaVz80/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

THE PROPHECY OF Zacharias - From The Douay-Rheims Bible - Latin Vulgate

Chapter 11

INTRODUCTION.

Zacharias or Zachariah began to prophesy in the same year as Aggeus, and upon the same occasion. His prophecy is full of mysterious figures and promises of blessings, partly relating to the synagogue and partly to the Church of Christ. Ch. --- He is the "most obscure and longest of the twelve;" (S. Jer.) though Osee wrote the same number of chapters. H. --- Zacharias has been confounded with many others of the same name. Little is known concerning his life. Some have asserted that the ninth and two following chapters were written by Jeremias, in whose name C. xi. 12. is quoted Mat. xxvii. 9. But that is more probably a mistake of transcribers. Zacharias speaks more plainly of the Messias and of the last siege of Jerusalem than the rest, as he live nearer those times. C. --- His name signifies, "the memory of the Lord." S. Jer. --- He appeared only two months after Aggeus, and shewed that the Church should flourish in the synagogue, and much more after the coming of Christ, who would select his first preachers from among the Jews. Yet few of them shall embrace the gospel, in comparison with the Gentiles, though they shall at last be converted. S. Jer. ad Paulin. W.

The additional Notes in this Edition of the New Testament will be marked with the letter A. Such as are taken from various Interpreters and Commentators, will be marked as in the Old Testament. B. Bristow, C. Calmet, Ch. Challoner, D. Du Hamel, E. Estius, J. Jansenius, M. Menochius, Po. Polus, P. Pastorini, T. Tirinus, V. Bible de Vence, W. Worthington, Wi. Witham. — The names of other authors, who may be occasionally consulted, will be given at full length.

Verses are in English and Latin.

HAYDOCK CATHOLIC BIBLE COMMENTARY

This Catholic commentary on the Old Testament, following the Douay-Rheims Bible text, was originally compiled by Catholic priest and biblical scholar Rev. George Leo Haydock (1774-1849). This transcription is based on Haydock's notes as they appear in the 1859 edition of Haydock's Catholic Family Bible and Commentary printed by Edward Dunigan and Brother, New York, New York.

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES

Changes made to the original text for this transcription include the following:

Greek letters. The original text sometimes includes Greek expressions spelled out in Greek letters. In this transcription, those expressions have been transliterated from Greek letters to English letters, put in italics, and underlined. The following substitution scheme has been used: A for Alpha; B for Beta; G for Gamma; D for Delta; E for Epsilon; Z for Zeta; E for Eta; Th for Theta; I for Iota; K for Kappa; L for Lamda; M for Mu; N for Nu; X for Xi; O for Omicron; P for Pi; R for Rho; S for Sigma; T for Tau; U for Upsilon; Ph for Phi; Ch for Chi; Ps for Psi; O for Omega. For example, where the name, Jesus, is spelled out in the original text in Greek letters, Iota-eta-sigma-omicron-upsilon-sigma, it is transliterated in this transcription as, Iesous. Greek diacritical marks have not been represented in this transcription.

Footnotes. The original text indicates footnotes with special characters, including the astrisk (*) and printers' marks, such as the dagger mark, the double dagger mark, the section mark, the parallels mark, and the paragraph mark. In this transcription all these special characters have been replaced by numbers in square brackets, such as [1], [2], [3], etc.

Accent marks. The original text contains some English letters represented with accent marks. In this transcription, those letters have been rendered in this transcription without their accent marks.

Other special characters.

Solid horizontal lines of various lengths that appear in the original text have been represented as a series of consecutive hyphens of approximately the same length, such as ---.

Ligatures, single characters containing two letters united, in the original text in some Latin expressions have been represented in this transcription as separate letters. The ligature formed by uniting A and E is represented as Ae, that of a and e as ae, that of O and E as Oe, and that of o and e as oe.

Monetary sums in the original text represented with a preceding British pound sterling symbol (a stylized L, transected by a short horizontal line) are represented in this transcription with a following pound symbol, l.

The half symbol (1/2) and three-quarters symbol (3/4) in the original text have been represented in this transcription with their decimal equivalent, (.5) and (.75) respectively.

Unreadable text. Places where the transcriber's copy of the original text is unreadable have been indicated in this transcription by an empty set of square brackets, [].

Chapter 11

The destruction of Jerusalem and the temple. God's dealings with the Jews, and their reprobation.

[1] Open thy gates, O Libanus, and let fire devour thy cedars.

Aperi, Libane, portas tuas, et comedat ignis cedros tuas.

[2] Howl, thou fir tree, for the cedar is fallen, for the mighty are laid waste: howl, ye oaks of Basan, because the fenced forest is cut down.

Ulula, abies, quia cecidit cedrus, quoniam magnifici vastati sunt : ululate, quercus Basan, quoniam succisus est saltus munitus.

[3] The voice of the howling of the shepherds, because their glory is laid waste: the voice of the roaring of the lions, because the pride of the Jordan is spoiled.

Vox ululatus pastorum, quia vastata est magnificentia eorum : vox rugitus leonum, quoniam vastata est superbia Jordanis.

[4] Thus saith the Lord my God: Feed the flock of the slaughter,

Haec dicit Dominus Deus meus : Pasce pecora occisionis,

[5] Which they that possessed, slew, and repented not, and they sold them, saying: Blessed be the Lord, we are become rich: and their shepherds spared them not.

quae qui possederant occidebant, et non dolebant, et vendebant ea, dicentes : Benedictus Dominus! divites facti sumus : et pastores eorum non parcebant eis.

[6] And I will no more spare the inhabitants of the land, saith the Lord: behold I will deliver the men, every one into his neighbour's hand, and into the hand of his king: and they shall destroy the land, and I will not deliver it out of their hand.

Et ego non parcam ultra super habitantes terram, dicit Dominus : ecce ego tradam homines, unumquemque in manu proximi sui, et in manu regis sui : et concident terram, et non eruam de manu eorum.

[7] And I will feed the flock of slaughter for this, O ye poor of the flock. And I took unto me two rods, one I called Beauty, and the other I called a Cord, and I fed the flock.