#wwii in colour

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

US Marines pose with their War Dogs - Bougainville, Solomon Islands 1943

#world war two#ww2#worldwar2photos#history#1940s#ww2 history#wwii#world war 2#ww2history#wwii era#solomon islands#bougainvillea#Bougainville#war in the pacific#pacific war#pacific#dog handler#us marines#ww2 colour photos

634 notes

·

View notes

Text

83 years ago, Independence Day was celebrated in somewhat different circumstances.

Street fighting on Independence Day in -34 degree frost in Karhumäki, Eastern Karelia, on December 6, 1941.

A high price has been paid for Finland's independence. We must cherish and protect this heritage that has been left to us. Happy Independence Day! •••••••• 83 vuotta sitten itsenäisyyspäivää vietettiin hieman erilaisemmissa tunnelmissa.

Katutaistelua itsenäisyyspäivänä -34 asteen pakkasessa Itä-Karjalan Karhumäessä, 6.12.1941.

Itsenäisyydestä on maksettu kova hinta. Meidän tulee vaalia ja suojella tätä perintöä, joka meille on jätetty. Hyvää itsenäisyyspäivää! •••••••• [ sa-kuva | 66119 | T.Norjavirta ]

#wwii#worldwar2#colorizing#jhlcolorizing#finland#ww2history#wwii history#ww2photos#colourized#history#ww2 continuationwar#continuationwar#continuation war#jatkosota#second world war#world war 2#war#war history#historia#colourised#colorized

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matty Firman (Suzanna Hamilton) and Colin Beale (Jeremy Northam) in Wish Me Luck S1 (LWT 1988).

#wish me luck#gif#matty firman#colin beale#colin x matty#suzanna hamilton#jeremy northam#1980s#period drama#spies#wwii#kissing#slightly different version of them in this ep#because a) the colouring is so horrible and i keep trying to make it better#but i'm afraid the dvd is just like this#and b) they really are v cute in it and it's hard to leave out bits#(it means nothing tho! lol)

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triumph Charade tulips R blush pink which transition 2 orange at the margins. Some charade tulips darken as they age. Orange tulips R the most popular tulip because they R such a bright color. But there R no natural orange tulips in the wild. The Dutch selectively bred orange tulips in the 17th century by mixing red & yellow.

Orange tulips symbolize a sense of understanding & appreciation between 2 people, usually in a relationship. Sending a bouquet of orange tulips means U feel spiritually & physically connected 2 recipient. Orange tulips symbolize excitement, happiness, enthusiasm, warmth, positive vibes & energy. If you receive orange tulips the person wants U 2 feel they R happy with U or 4 U or just want 2 cheer you up.

See other tulip posts 4 info on why Canadians receive a gift of 10,000 Tulips each year for last 78years from the DutchRoyal Family.

#tulips#floral photography#flowerphotography#floralphoto#colour photography#outdoorphotography#garden#gardeners#garden photography#fieldoftulips#canadiantulipfestival#mostpopulartulipcolor#photography#naturephotography#photooftheday#photowalk#puplicgarden#charadetulip#history#WWII#dutchroyalfamily#orangetulips#nature#pretty#largesttulipfestivalinworld#bokeh shotz#pinkandorange#pinkandorangetulips#springphotography#macro photography

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you for this!

In case anyone tried to whitewash your Battle of Britain lately. I present receipts of the countless Jamaican, Haitian, Indian, and Māori fighter and bomber crews in the RAF. Fully integrated.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

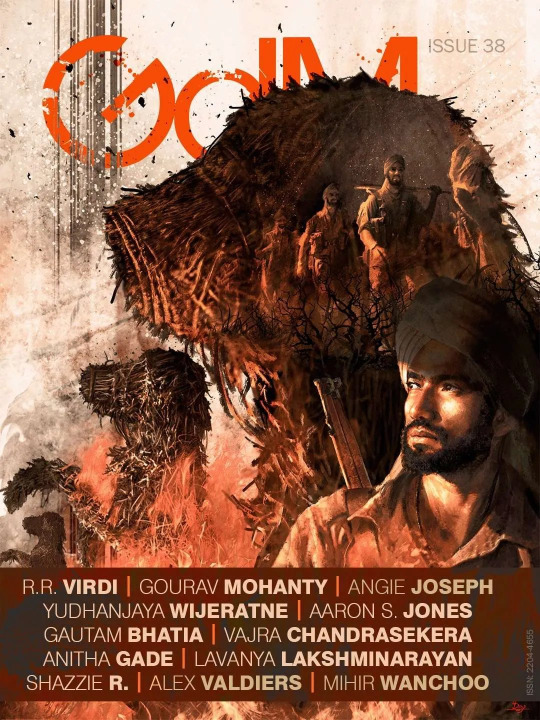

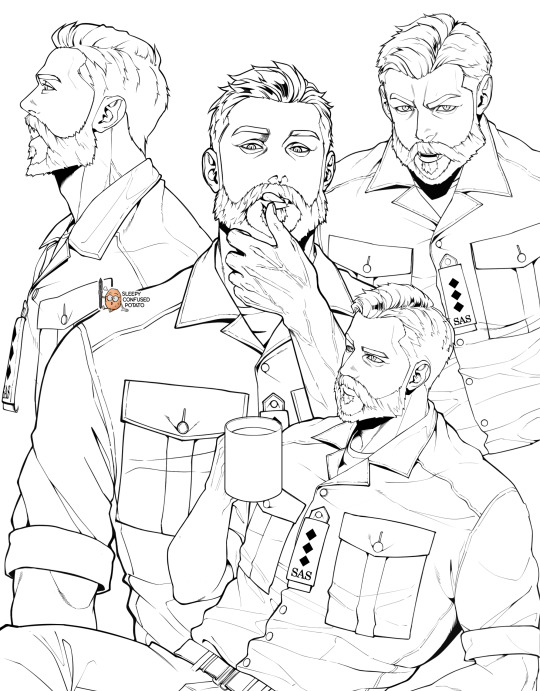

Super cool reminder of this from last year and the wonderful @Grimdark_Mag and @BethTabler compiling this.

It's the first western mag/piece to ever feature Punjabi Sikhs wearing turbans!

And is filled to the brim with brilliant writers.

It was an honor and more to be asked to be included, and to have Reed Lions, my short fic, be chosen to be the inspiration for the cover. It means actually a lot to me being of Sikh heritage and the history of Sikhs serving in battle being formed as a warrior culture to protect/serve.

My specific story follows a dwindling group of soldiers on their last legs at the frontlines drawing inspiration from the history of Sikh soldiers serving on the front lines in the African campaigns during WWII especially. This is set in a fictional secondary world - Punjabi names, slang, mannerisms, and cultural pieces are full through the story.

A quote: "Finally, we that live on can never forget those comrades who in giving their lives gave so much that is good to the story of the Sikh Regiment. No living glory can transcend that of their supreme sacrifice, may they rest in peace. In the last two world wars 83,005 turban wearing Sikh soldiers were killed and 109,045 were wounded. They all died or were wounded for the freedom of Britain and the world and during shell fire, with no other protection but the turban, the symbol of their faith." General Sir Frank Messervy KCSI, KBE, CB, DSO

The story def. broke some hearts, but if you want to support a whole host of wonderful writers on that cover and the magazine, please go check it out.

#throwback#history making#punjabi culture#punjabi sikhs#turbans#Grimdark#grimdark magazine#short story#short stories#WWII#world war 2#ww2#world war ii#external link#support content creators#support authors#author of colour#author of color#southeast asian#Punjabi stories#sikh culture#storytelling

1 note

·

View note

Text

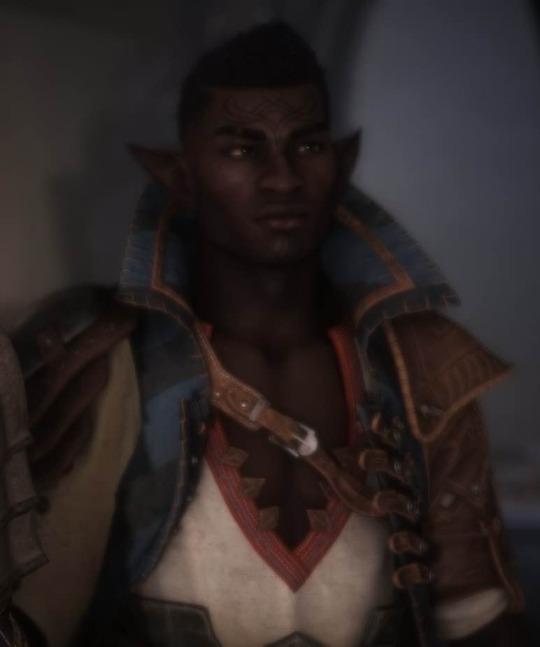

It took a minute to piece together why Davrin's armour was so familiar despite being such a unique warden design but then it finally clicked. And it's brilliant.

Davrin has griffon rider armour.

Modernized, of course - it's been almost 500 years after all. If Garahel's armour took some inspiration from WWI pilot uniforms, Davrin's pulls from WWII, drawing on the vibe of the classic leather jacket with the wide, high collar taking the place of lambswool.

It's debonair and cavalier, a griffon rider for these modern times of 9:52, but it keeps the same colour scheme and basic elements of brown leather on blue cloth with sparse metal elements. And there's even a nod to the leather scales on Garahel's shoulder on Davrin's.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

⭑ for the love that used to be here. tom riddle x reader

summary. you and tom are the only muggle-borns in slytherin, until one day he isn’t.

tags. angst, afab reader who is referred to as a witch a few times and rooms with girls but i don't think i ever use she/her pronouns or say the word girl/woman, biggest warning is that this is SO long (idk what compelled me to write a year 1 – post-hogwarts fic but here we are twenty thousand damn words later), blood purity and bigotry, dumbledore is greatly offended by the bonding of two orphans until he can capitalise on it, frequent wwii mentions (specifically the blitz), book clerk tom, MURDERER TOM… ministry reader, kissing, smut once they’re 21/22 May all the minors in the room exit at once, more angst, sad ending kinda, me spreading a very personal and very nefarious tom riddle agenda that is canon to ME but probably only like two other people

note. i need a shower and an exorcism after writing this shit. i'm exhausted. i don't even remember half of it. but i'm also SO stoked, this is my little (very large, frankly) 100 followers celebration! i've only been on here for about a month and the love has been so crazy so thank you mwah mwah mwah ♡

word count. 21.8k (i know... i KNOW)

You learn quickly that your shade of green is not the same as theirs. The rest of them are emeralds, even at that age — they glitter with their parent’s polish. You are flotsam, sea-sick, envy green; the putrid boiling stuff that brews in your cauldron when you look away for a second too long, and, really, it’s more of a stain than a colour at all. There is a fraction of a second where you find something powerful in that. You are not an easy thing to remove. And then it’s gone, because they want to so badly.

You learn, with a bit less tact, that you doesn’t actually mean just you; that it’s you and him whether you like it or not.

He evidently does not.

“It has to be completely fine,” Tom says to you in Potions, his voice small then but just as practised.

You narrow your eyes. “‘Scuse me?”

“I said the powder has to be completely fine.”

“I heard you completely fine. I know how to read.”

He stares blankly at you before returning to his own station, and that’s that.

It isn’t unheard of for muggle-borns to be sorted into Slytherin, so you’ve been told, but one glance around your common room and you can see it’s pretty damn rare.

There’s Tom Riddle, there’s you, and there’s a seventh-year girl whose knuckles are always white like she’s spent so long with her hands balled into fists that they don’t know how to do anything else. Tom Riddle is a prat, the girl is too old and unapproachable even if she wasn’t, and you are very good at being alone.

That decides it. Flotsam still floats.

Everything is — fine. It’s fine for months; you have no one and need no one and sometimes you catch a jinx in the back of Charms that zips your mouth shut or bends a foot the wrong way (a cruel reminder of how much more these people know than you) and your broom occasionally pivots so sharply the Flying professor has to stop you from careening into a wall and breaking enough bones for a week’s worth of Skele-Gro, but it’s fine.

…It’s just that he’s insufferable.

The boy is eleven years old and he speaks like he’s stealing glances at an invisible lexicon between every word, more refined than any of the orphans you grew up with which makes you wonder which sort he’s surrounded by, and you take it upon yourself to theorise in passing if you could ever scare him badly enough his real voice would slip and he might just appear human for once.

Only it becomes clear when you’re stirring awake in the Hospital Wing after a mysterious bout of dragon pox (conveniently, all the pureblood children developed an immunity after catching it young) has rendered you bed-ridden and pockmarked, that you don’t think anything can scare Tom Riddle. He’s suffering just as well in the bed beside yours to keep the contagion to the two of you, and he’s all cold, eddied rage under sallow skin and beetling bones.

“They’re going to kill you,” he says after three days of silence, when the room is dusted in moonlight so thin it’s like squinting through cinema noise or mohair fluff to try to see him.

You blink at the vague shape of him. “What?”

“If you don’t hurt them back, eventually, they’ll just kill you.”

In hindsight, it’s an assumption so hastily bleak only a scared child could make it.

I want to hurt them, you try to say, but for what follows you cannot: I want to hurt them but I’m not good enough to do it.

You roll over and pretend to sleep, and in the morning, you hurt them anyway.

It’s Avery who’s unlucky enough to be the first to test you when you’re three assignments behind in Transfiguration, still a bit groggy from your last dose of Gorsemoor Elixir, and actually, physically green. He tugs your hair and stings your cheek with the promise of “bringing a bit of colour back to your face” and it’s sort of funny how banal it is compared to the other transgressions you’ve been dealt — that this is the thing that makes you bare your teeth, grip your wand in a hand that still can’t hold half of it, and send Avery flying across the room with a Knockback Jinx.

Tom sits with you in the Great Hall for dinner that night, and he never really stops.

You practise spells by the Black Lake between classes and he’s anything but kind about the ordeal, but you teach each other. You end your days with singe prints and sore wrists and you often take more damage than he does, but sometimes, as spring settles in with warm tones (apple and jade and moss — all the greens you’d never imagined), you leave with less bruises than he does. It hardly feels like friendship. It feels much more like purpose.

When summer comes you don’t write to him, and you don’t expect he will either. You don’t suppose you’ve actually written a letter in your life. Instead you try new wand movements under your quilt every night and wait for August’s departure on a big red train.

You sit together when the day does come. He asks you if you’ve been practising. You frown and tell him you’re not allowed to use magic outside of school.

Second year is nothing but monotonous, antiquated theoretics. Most everyone complains. You don’t see why they should — they’re already aeons ahead of you — but that means you finally have a chance to catch up in your less-than-school-sanctioned meetings with Tom while the rest remain practically stationary.

Deputy Headmaster and Transfiguration professor Albus Dumbledore is imperceptibly less soft with you than he was last year when you make the apparently poor decision to sit beside Tom on the first day, and you file the subtle shift in demeanour into some mental cabinet to review later.

You find workarounds with the librarian, Madam Palles, inclined to sympathy for the poor, orphaned muggle-borns to grant relatively unfettered daytime access to the Restricted Section so long as you keep it tidy and none of the books leave the library. That’s where things get a bit more interesting.

For a month you remain innocuous as can be. You browse through rare historical tomes and foreign biographies that would charge more galleons than you can conceptualise, and you never leave so much as a tea stain on the parchment. You smile at the Madam when you return the key each night, and walk back to the dungeons with your hands behind your back. It is, of course, totally unrelated that a month is what it takes for Tom to master the third-year curriculum’s Doubling Charm. An entirely separate affair when you meet him in the most secluded alcove of the library, slip him the key, and stifle your grin as he duplicates it perfectly.

You discover Christmas break is your favourite time of the year. Nearly all the purebloods go home. The Slytherin dormitories are effectively halved.

It’s two weeks of earnest, uninterrupted work and sleep without fear of waking up with jelly legs or whiskers.

Madam Palles, most nights, makes a slight, drowsy effort of searching the library for leftover students before she casts the lights out and closes the door. Then, it belongs to you and Tom.

You’re splayed rather ridiculously over one of the big reading chairs on Christmas Eve, Lore of Godelot in hand, enthralled by a chapter detailing his controlled use of Fiendfyre through the power of the Elder Wand.

Tom is cross-legged and sat straight, his brows furrowed in concentration.

“What’ve you got?” you ask, leaning over to answer your own question.

Tom as good as rolls his eyes, holding up the book to give you an easier look.

“Magick Moste Evile?” You scrunch your nose. “Bit much, don’t you think?”

“It’s the stuff they’ll never teach us.”

“I wonder why.”

He steals a glance at your own book and smiles in that smug way that makes you want to slap him.

“What, Tom?”

He shrugs. “You might want to know you’re reading stories about the author.”

You look down. Lore of — Godelot wrote Magick Moste Evile?

It shouldn’t really be surprising. Three chapters ago your book was recounting his months in Yugoslavia grave-robbing magical burial sites.

“Whatever,” you mumble, “It’s just a biography. Least I’m not reading the words out of his mouth.”

“Well, they’d be out of his quill.”

“Oh my God, Tom, shut up.”

All good things must come to an end. Term resumes and your hackles are back up.

Abraxas Malfoy, Antonin Dolohov, Walburga Black and the best of the worst of your house have returned, sleek-haired and insatiable and deranged, truly, in such a manner that you don’t think you can be blamed for the instinct you feel every time you pass them to lunge like a wild predator or run like wild prey. All Tom does, though (and so you follow, because he’s standing with you and who has ever done that?) is meet their gazes with equal assuredness. He never seems bothered. He never seems animal. You are still all hammering heart and heavy lungs, and you are learning not to see the world through the eyes of someone who’s only ever had their fists to fight. You have magic, you remember. You’re good at it. You could hurt them, if you really wanted.

Not much is different that summer than the last. The war is hard. The food is hard to chew. You chip a tooth. You’re too afraid to fix it with the Trace on you, but you still smile because you will, and everyone seems put off by that. What is there to smile about?

You suppose, for them, it’s a question with few answers.

For you — you’re back on a big red train musing about the functions of muggle warfare with Tom Riddle, chucking a useless card from a chocolate frog out the window and moaning about how you wasted the sickle you found under your seat.

He’s gotten very good at ignoring your theatrics and going right back to whatever it was he was talking about. And you note, unrelatedly, he almost looks like he’s learned how to open the windows at Wool’s. (You dare not suggest he’s doing something so ludicrous as sitting in the sun too, but this is a start.)

Dippet, or the Minister, or whoever it is that’s in charge of the practicality of the curriculum, has become fractionally less stupid in the last three months.

You don’t have to rely on nights in the Restricted Section or weekends at the Black Lake to actually learn something anymore. Of course, without the assistance of those illicit extracurriculars, you wouldn’t be able to match up to your peers the way you are this year, but it’s nice to duel with dummies instead of motioning your wand vaguely over a desk, and you and Tom still climb the notice boards in rapid succession.

They hate you for it. One of your roommates makes a pointed effort each night to glare at you from her bed like those jelly legs are back on the table, Orion Black (two years younger but just as nasty as his cousin) nearly trips you on your way to Divination, Abraxas Malfoy develops what you think borders on obsession with Tom, and for once it feels almost offhand to not care about any of it.

You’re beginning to think even at its best, Hogwarts is remarkably insufficient. This leads you to books mercifully unrestricted so you can read about a few of the other magical schools for comparison. Beauxbatons is renowned for providing most of the worlds alchemical developments, Uagadou’s early propensity for wandless magic makes it unfathomably more practical than Hogwarts, Durmstrang (though you scoff at their violent anti-muggle sentiment) teaches the Dark Arts as something beneficial rather than unforgivable, and — what do you learn here? Even with the hair’s-breadth of magical leniency you’ve been allowed this year, it’s no surprise so few recognizable names in wizarding history are Hogwarts alumni.

“Let me have a look at that,” you say to Tom one evening, when he’s peering once more over the pages of Magick Moste Evile. He’s a purveyor of knowledge in all forms, but he always seems to come back to Godelot in the end.

He raises a brow, handing it to you like your intrigue doubles his. “No more reservations?”

“Don’t get ahead of yourself. I’m only curious.”

“Curiosity—”

“Killed the damn cat, I know.” You glare at him through the pages. “I think that’s you, in this case though, since you’re the one in love with the bloody thing.”

He shakes his head as he reclines in the low light of the Restricted Section, muttering something that sounds like “ridiculous,” or “querulous,” or something else unimaginably fucking annoying.

You might be wrong. Retract your last quip and expunge it. If Tom’s in love with any book, it’s the behemoth dictionary he’s been spitting stupid adjectives out of since he was eleven.

But Godelot’s musings on the Dark Arts are fascinating enough that you can understand the appeal. He’s no wordsmith, and you appreciate that in a way you’re sure Tom deems regrettable, but his points are straightforward but thoughtful in such a way you can read in them how he was guided by the Elder Wand through everything he did. There’s a stream-of-consciousness to them. Something doctrinal you’re surprised to enjoy for all the obligatory English creed they washed your mouth with at the orphanage.

“Find what you’re looking for?” Tom asks, combing with little interest through the tomb you’d put down in favour of his.

“I’m not looking for anything. I’m just…” You sigh. It’s almost painful to say. “I think you were right, and — oh, shut up, don’t look at me like that — I don’t think we’re learning anything here. Not really; not as much as they do at other schools.”

“Of course,” he says blankly. “Hence this.”

This — restricted books and furtive duels — should not be necessary.

“You know that’s not gonna be enough. For the rest of them, maybe, but not us.”

He tenses how he always does at the reminder of his difference. And you get it. Sometimes in moments like these you forget the reason you’re here in the first place. It isn’t just the rebellious divertissement of two academically eager students, it’s… survival. What future do you have as a penniless orphan in wartorn London? What future do you have as a muggle-born Slytherin who’s apt with a wand when there are a thousand more your age, just as skilled and twice as pure?

It isn’t enough to be as good as them. You have to best them, and you have to do it forever.

The night stumbles into an exhaustive silence because you both know it’s true and it’s a bit too heavy right now. The answer isn’t in this room. Just you. Just him. So you sit in the dark and you stare through that muffled nighttime noise playing tricks on your eyes. The worst of the world can wait until morning.

The worst of the world has impeccable timing.

A fault of both sides of the coin; the muggle world is a travesty and the wizarding world is just a bit fucking late, really.

So there’s the newspaper. It’s October first and the date reads September tenth. School owls are a joke and you can’t afford anything better.

And it’s a dirty, ashen grey. It smudges your green if you ever had it at all. You were born to this and you will return to it always.

BOMB’S HAVOC IN CROWDED PUBLIC SHELTER

MOTHERS AND CHILDREN AMONG THE CASUALTIES

DAMAGE CONSIDERABLE, BUT SPIRITS UNBROKEN

All you can hope to do is pass the paper to Tom and wonder without words what you’ll go home to.

The answer is very little when the summer clouds your vision with dust and you stand dumbly with your suitcase in front of nothing at all. You’d tried your best until your departure to keep up with muggle news, but it had remained, routinely, a month behind with the owls. By the time June arrived you were still holding your breath through May. Tom had attempted to reason with Dippet for summer lodgings at the school but you were both denied in light of the exquisite mercy — the bombs have stopped! The Blitz has ended! Go back to the aftermath and make do with the craters.

It’s a bit ironic that Tom’s orphanage survived and yours didn’t. At least you can finally see what all the fuss is about.

In truth, it’s more strange than anything. You feel unreasonably like you’re impeding on a part of him that has never belonged to you (if any of him does); that place where you intersect but never draw attention to. You remind yourself you had no choice in the matter. The system puts you where it wants to, and these days the options are slim. But it’s — the walls are amber-black tile and plaster, lined with sanitary-smelling hospital beds and a cupboard per room. Per room, you think; you’ve got one of those now, and with only one girl to share it with.

You figure the reason for the extra space is probably not one you want to know.

Anyway, you don’t actually see Tom for two days. The caretakers bring you a tray of dinner that’s vaguely warm and a bit too salty and you sleep off the debris you think you breathed in that morning, half-sated and sun-tired.

But then you do see him, and he’s in these funny uniform shorts and a thick blazer and your greeting is an offhand joke about the scandal of his knees that he doesn’t seem to appreciate. He eyes your muggle clothes while you wait for your own set and you know you really don’t have any room to judge.

He doesn’t, or at least doesn’t say he minds your relocation.

You spend half the summer waking up in the middle of the night to acquaint yourselves with the London tube stations, and the other half in whatever crevices of the orphanage you aren’t harangued by Mrs Cole every five seconds, which are far and few between. She seems to have decided fourteen is old enough an age to worry about your intentions unchaperoned, like it’s the bloody 1800’s, and admonishes you and Tom relentlessly despite only ever finding you quietly buried in useless books.

You begin to miss Madam Palles and her invaluable pity. Everyone’s an orphan here. No one’s sorry.

“What’s his deal?” you ask one stuffy afternoon, reclining in your creaking seat to prop your legs on the desk.

Tom knocks them off (he’s so well-mannered that you sometimes push these little gestures of impropriety just to bother him) and glances at the target of your question. Some broad, blond boy who skitters down the corridor a shade paler than he arrived. You’ve yet to properly introduce yourself to anyone you don’t have to, so names are muddy when you try to apply them to faces.

He shrugs, but there’s a flash of something in his expression you’re fascinated to realise is unfamiliar. “He’s an imbecile.”

“...Riiiiight, but that isn’t a proper answer.”

You smile. Legs return to table. Timeworn Oxfords muddy the surface. Tom scowls.

“There was an altercation last year,” he says tersely, “he’s rather fixated on the matter.”

“An altercation.”

“Very good, that is what I said.”

You narrow your eyes and he sweeps your legs off the desk again, gaze catching the unmistakable ribbon of an old bullied scar on your shin.

“And I suppose you’re above such incidents,” he muses.

You cross your arms and huff. He always wins games like these.

You’re grateful when you return to Hogwarts in one piece after your final night of summer is spent underground, and the certainty of knowing where you’ll rest your head for the next ten months cannot be understated.

But the worst thing has happened, and you blame it on the flicker of a moment where you missed Madam Palles like it was some jubilant, accidental curse to ever miss anyone. A foreign thing you remind yourself never to do again.

She’s only gone and jinxed the locks to the Restricted Section so they cry like newborn Mandrakes when Tom’s replica key clicks in place.

For a second you both stand there looking stupidly at each other. Getting caught was a fear two years ago; you’d almost forgotten it was still possible.

Tom is quicker to collect himself. He grabs you by the arm and casts a Disillusionment Charm, and you don’t burst running out of the library like two blurry suncatchers reflecting the candlelight as your instinct heeds; you cling to the shelves and you slither silently to the door. (You’ll make a joke about it when you can breathe.)

Madam Palles the Traitor comes heaving into the library in her nightgown, a blinding blue light baubled at the end of her wand, and it’s really just theatrical at this point to use Lumos bloody Maxima when the basic spell would do the job just fine.

“Has she suspected us the whole time?” you say on gasp once you’ve made it to the dungeons.

“Perhaps someone else has,” Tom suggests.

“What? Malfoy?”

You think it’s a good first guess. It could have been any of the Slytherins, upon consideration, but Malfoy seemed most fixated on Tom last year and it wouldn’t surprise you to learn he’d been observant enough to follow you to the library and notice you don’t leave with the other students.

But Tom quashes the idea. “I’m doubtful. Malfoy is attentive, but Madam Palles is hardly partial to him.” (He had, in second year, set one of her books on fire while studying offensive spells.) “I suspect it was someone with more influence.”

Only no one has more influence than Abraxas Malfoy. The rest of the Slytherins follow him like lost pups. But then Tom might mean —

“A professor?”

“It may be.” He says it like he’s already decided his suspect.

He is, as always, and ever-infuriatingly, correct.

It’s that file you tucked away for later, reoccurring when you return to Transfiguration in the morning like a second epiphany: Dumbledore.

He assigns the term’s seating arrangements, which he’s never done before, and there’s something in his tone when he pairs you with Rosier that feels intentionally like not pairing you with Tom. You don’t think it’s paranoia clouding your better judgement, and by the way Tom’s gaze hardens as he takes his seat beside Malfoy, neither does he.

Dumbledore is suspicious for a number of reasons. He disappears for weeks at a time. The Prophet writes articles on his sightings in Austria and France like he’s an endling beast. He’s being sighted in Austria and France — two notable countries in Grindelwald’s ongoing war. Perhaps ancillary, you’ve decided the charmed glass repositories he uses to hold his old artefacts are the same ones encasing the least permissible books in the Restricted Section. And if that isn’t paranoia (which, you’re willing to admit, it may be) then you assume he has them so proudly on display because he wants you to know.

You consider it a warning.

Tom does not.

“Just give it up,” you hiss over a game of wizard’s chess, “I bet we’ve read every book in there twice already anyway.”

His jaw ticks as the sole indicator of his annoyance, and he takes your rook. You scowl.

“Tom, that man thinks you’re devil-spawn. You know he’s just waiting for an opportunity to catch you doing something wrong.”

“So?”

It sounds so petulant you think he’s been possessed by his eleven-year-old self. Then you think he was a lot wiser at eleven.

“So?” You make an aggressive move with your knight. “So don’t give him one!”

He stares at the board and his breath is just a trace sharper and you hate that you know him like this and no one else. You wonder if he knows you like that too, but resolve with ease that he does not. You’re hard frowns and lewd jokes and trousers torn at the knee to bare scars with stories you wish you could forget. There’s no mystery there. Tom is nothing but — gordian knots and fixed expressions and little patterns to learn like the rules of this stupid game between you. You must know Tom Riddle by every atom or not at all. And that isn’t a choice, really. You’ve never known anyone else.

“Are you stupid, Tom?”

You glance at the board. He’s got Check. A terrible, true answer.

“No,” you finish. “Then don’t act like it.”

Your king glances at you and you nod. He falls. The game is resigned.

Tom acts stupid.

Dumbledore knows.

It all happens very fast.

You strike Tom harder in the arm with Confringo than is likely necessary that night, and he returns the favour with a Knockback Jinx that thrusts you into the shallows of the Black Lake.

You gasp. The cold water feels like it’s swallowing you whole when it strikes, an envelope sealed around you and licked shut for good measure. Everything holds to you, and it’s fucking November. Your senses are so overwhelmed that you forget to murder Tom the instant you sink in. You forget to do much of anything.

You wade trembling out of the lake when sense returns and Tom huffs, peeling off his robe to treat the burn on his arm.

“You—idi—iot,” you mutter, trying to find the incantation for a warming charm but the words get stuck between your chattering teeth. “You stole a re… stricted book.”

Tom glares daggers at you between his poor healing job and you scowl, mincing through the grass and grabbing his arm. “Fucking imbec-cile…”

You’ve done enough damage that if he were anyone else you’d be proud of yourself, and somehow, simultaneously, if he were anyone else you’d be able to manage a pinch of guilt. But he’s Tom, and you know him by every atom, so you cannot be proud, and he’s Tom — he retaliated by tossing you in freezing water and now your clothes are clinging sodden and heavy to every inch of you, so you certainly can’t be guilty either.

“I borrowed it,” he says tightly. As if that means anything at all. And then he takes his robe and drapes it spiritlessly over your shoulders. “You could attempt communication before curses.”

“I could attempt communication,” you scoff, uttering a charm to partially close the gash on Tom’s arm, “Fucking h-hypocrite. I did communicate. You lied.”

“I —”

“Omitted information? Withheld the truth? Watch your mouth or I’ll steal your fucking dictionary, Riddle.”

You swear a great deal when you’re cold and mad, apparently.

“I won’t be caught.” His calm is infuriating. “It would hardly earn expulsion regardless.”

“It doesn’t matter! He knows it’s you! He was staring at you all class!”

“So nothing novel then.”

“D’you want me to blast you again?”

His lips form a flat line. No. That’s what you thought.

You sigh, clutching his robes in your fists to quell your trembling. “What’d you take, anyway? We never touch the encased stuff.”

That is, you assume, why Dumbledore was vexed enough about the whole thing to mention it in class today. A highly valuable book has gone missing, from a repository you dare conclude belongs to him, and he has to pretend all the while not to know it’s Tom who took it. You are out of the question. Theirs is some delicate vendetta you can’t begin to unfurl.

“Nothing anyone should miss,” Tom says, a complete non-answer as he stops to murmur a warming charm you could probably manage yourself by now.

“Tom.”

“It was an encyclopaedia. It’s entirely in Runes. I suspect it will take months for me to decipher.”

“God’s sake,” you groan. He really is exhausting. “I think Dumbledore’l take his chances and loot your dorm before that happens.”

Tom wipes a stray droplet of water from your cheek. His fingers are soft. “We should return. You look half-drowned.”

“I am half-drowned, dickhead.”

And you accost him in hushed tones the whole walk back. Runes, Tom, really? Threw me in the damn lake over a Runic Encyclopaedia? He accosts you just the same; You burned me first.

It does, in fact, take Tom months to decipher the Runes, and he’s quite secretive about it. He won’t let you see the book, won’t tell you what it’s about, won’t indulge your queries on how far he’s gotten or if it’s worth the way Dumbledore bores his eyes into the pair of you in the Great Hall with nothing but the glass of his spectacles to soften his censure. You consider — well — you consider taking your chances and looting his dormitory.

The day everything changes starts the same as any.

You muse over breakfast about muggle news and how the way Tom holds his wand when he casts defensive spells is too sharp when it should be circular. He argues. You soften the criticism by telling him his offensive magic is stellar but you’ll always beat him in defence if he doesn’t swallow his damn pride and listen to you for once. (So, really, you soften it very little.) He doesn’t take Divination so you don’t see him until Herbology that afternoon and he’s silent enough during the hour you share with your wormwood plant that you know he’s done it sometime between breakfast and now.

Tom has cracked the book.

It’s late spring and the night takes longer to settle than it did in the winter. Errant sunbeams still sparkle on the water when you meet him by the lake, and it’s warm enough to forgo a coat.

“Are you going to tell me what it’s about now?” you ask without preamble, arms crossed over your chest as he approaches.

He hands you the book like it’s worth something to you without his explanation, but you’re intelligent enough to gather something from the illustrations of two twined snakes embroidering the cover.

“I should have suspected it sooner,” Tom says before you can comment. “By the way Dumbledore acted when I told him… I should have known he would have wanted to keep it from me.”

“Tom, I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

“It’s an Encyclopaedia on Parseltongue and its known speakers.”

You flip through the pages and none of it means anything. “Parseltongue?”

“The language of serpents,” Tom supplies, and the two of you walk along the edge of the forest. “It’s almost exclusively hereditary.”

“Okay, so, what — you’re trying to learn it anyway?”

“I have no need.”

You frown. “You… you already know it.”

“I always have,” he says, and there’s something almost unrestrained in his voice. He’s proud in a new light, and it takes you a moment to understand and you’re not sure why exactly it makes your heart sink, but —

“You’re not muggle-born.”

“No, I’m not. And Dumbledore knows.”

“So, he —” You try not to sound crushed because why should you be? Why should it matter that he isn’t some exact reflection of you? He’s at your side, he’s still there, he’ll always be there — “How does he know?”

“When he came to Wool’s to inform me I'd been accepted at Hogwarts. I hadn’t known anything, certainly not that speaking to snakes is emphatically rare, so I asked him. He said it was ‘not a peculiar gift.’ Perhaps to keep my interest at a minimum.”

“Why would he lie?”

“Because it isn’t just that I’m of magical blood. I’m a descendant of Salazar Slytherin.”

You can’t be faulted for laughing. It’s not often Tom makes jokes, let alone funny ones.

“That’s good, Tom. Morgana used to have tea with my great-great-hundredth-great-grandmother, so that works out nice.”

He sighs, taking your hand and leading you further into the woods.

“Are you trying to murder me?”

“I might.”

“You’d be the first suspect.”

“No, I wouldn’t. You’ve far too many enemies.”

Not by choice, you start to scold, and then he stops, not so far into the Forbidden Forest that you’re afraid, but far enough you understand this is not something he’d chance showing you in the open.

He closes his eyes and whispers, and it’s — decidedly not English. And you know the sound of a few other languages, at least; this doesn’t sound like words at all. His consonants are pointed, his S’s stretched, the syllables repetitive but separated by a difference in cadence someone less perceptive might not notice.

It shouldn’t be surprising; it’s exactly what he told you, but it startles you how much it reminds you of a snake.

“Tom?” you murmur, unsure at the prospect of speaking some ancient, unknown language into the air of the Forbidden Forest, and, underneath that, still reeling with the knowledge that this is real at all. You’ve pinched yourself a few times to make sure.

There’s a low susurration in the grass, wet with dew that catches the moonlight, and you gasp, clinging to Tom’s arm when you see the blades part in helices for the space of an adder.

“It’s all right,” Tom says softly, almost elsewhere, his eyes zeroed in on the snake. “It won’t hurt you.”

You’re still by the balance of his arm and some petrifying awe as he extends a hand to the grass and the adder coils around it, weaving upward to his shoulder.

“Oh my God. Oh my God, Tom.”

The adder points its beady gaze at you, and Tom whispers something else in that strange language before it retreats in agreement or compliance or whatever could come close to expression on the face of a fucking snake, and maybe you’re dreaming this despite your pinching. Maybe you’ve lost your mind.

“Hope you didn’t just tell it to bite me,” you try, and it comes out half-choked.

He smiles. It’s partly for you and partly for this venomous little thing on his shoulder, and that’s a bit startling. Tom Riddle smiles for adders and you and not much else.

“Should I?”

And all you manage, for whatever reason, is, “Don’t be like them now that you’re not like me.”

It’s out before you can stop it, welling from a small, scared place that embarrasses you to return to. A hospital bed when you were eleven. The walls of a bedroom ravaged by bombs.

Tom’s smile fades. “We’re nothing like them.”

The thing is, neither of you know that’s the day that changes everything.

You celebrate your fifteenth birthday in the Deathday ballroom with Tom, a stolen dinner pastry, a green candle, and a few sad ghosts. You try to learn how to dance. Tom thinks it’s silly. You tell him that’s only because he’s upset he keeps stepping on your toes.

Summer blisters when it comes.

Some of the children take jobs as mail-sorters and steelworkers and you clasp for whatever you’re (one) allowed and (two) capable of, which isn’t much. You’re both old enough at the end of the day to explore London on your own, opting to spend as much time away from the orphanage as Mrs Cole allots, but you only have knuts and pennies and you warn Tom it would be unwise to swindle muggles and risk a letter from the Ministry. So you work where you’re needed and you eat the rationed nonsense you always do and you miss Hogwarts terribly. It’s much the same: you’re together, you’re hungry, and you’re nothing like them.

And then it’s different: Tom makes Slytherin Prefect, is suddenly tall, and you wonder in fleeting moments if his face has always suited him this well.

A stupid remark. You fervently ignore it.

Fifth year begins and you have almost the same number of electives as you do core classes, Tom has duties in his new role that take much of his spare time, and despite popular belief, you and him are not a mitotic entity, so this splits you up more often than it had in previous years. Which is fine. You still have plenty of things to talk about during meals and between duels, and you reckon you’ll share DADA until you graduate.

But in his absence, your attentions are forced elsewhere, and you should be grateful they land on something potentially promising.

It’s like Transfiguration just clicks for you this year. You’ve never been the greatest at Transformation (importantly though, you’ve also remained far from the worst), but fifth year launches you into Vanishment and something about that feels like a perfect equation. There are no complicated half-numerals and objects stuck between inanimacy and being — just unmaking the made. Nothing or not. You’re fucking excellent at it. You glean the theoretics fast and then the practise comes like breathing. Even the purebloods struggle as you Vanish Dumbledore’s Conjured garden snakes in brilliant tendrils of light. You exult unabashedly when you brush past them on the way out of class — who was it that didn’t belong in Slytherin?

You say the same to Tom and he rolls his eyes, but the amusement is there.

“Think you can talk to my snakes for me?” you tease, nudging him on the path to Hogsmeade.

“If they’re yours, I doubt they have anything worth discussing.”

And Dumbledore is… a hue nearer to the man you remember from first year. He praises your improvement and smiles when you can’t hide your giddiness as if equally impressed.

He doesn’t shelve people the way Slughorn does (you’re dismayed to find Tom has been invited to join the Slug Club and you have not) but you think if he did you’d be rapidly climbing your way to the top. Maybe get put in one of those neat little repositories he keeps all his best treasures in.

Dumbledore does, however, offer additional assignments for those who are interested, and tasks you with a few if you’re up to the challenge.

You always are.

The Tom-Dumbledore-Encyclopaedia debacle is apparently either resolved, or your part in it forgotten.

Tom humours you when you’re both singed at the fingers from duelling, yours dipped in the lake while he buries his in the cold moss, about how Abraxas takes the seat beside him at every Slug Club dinner. He tells you he pretends to be very interested in the Malfoy’s business affairs and their stock in the Bulgarian Quidditch team’s win this coming spring. He tells you he finds it amusing to let Abraxas think he can make Tom his pet. Tom says he considers searching for Salazar Slytherin’s fabled Chamber of Secrets and showing Abraxas what a real pet looks like. You smack him in the arm.

He’s had an ego forever. He just has a few too many reasons for it now.

And maybe that’s why you push harder in Transfiguration, dedicate the majority of your studies to it, spend your Saturday nights scrutinising advanced techniques while Tom makes nice with Potions experts and politics with people who don’t even know what he is but like him anyway. It’s patronising, of course — borderline fetishistic; not a real like — but it scares you. Tom Riddle would not allow himself to be anyone’s pretty mudblood show pony if he didn’t have an ulterior motive.

Everything changes but the observable truth that he is still insufferable.

You’re lucky to see him twice a week if it isn’t in class, and the way it starts is so slow you don’t even fully understand what’s happening until Christmas break when Abraxas stays a few extra days and leaves by Dippet’s Floo instead of the train.

You don’t dare ask where Tom has vanished to in that time or why the hell Abraxas Malfoy would willingly subject himself to unnecessarily extended time at school with all his lackeys gone, and it isn’t because you don’t want to. It’s because he won’t tell you himself. It’s because you’re terrified the answer will feel like a broken promise, and you’ve come to realise (it’s been there for so long; such an obvious, tiny thing that you’ve never stopped to really dissect it) that it’s quite difficult to know someone at every atom and not love them a little bit.

You’re suddenly aware of the risk of it: you love him like an inextricable piece of yourself, and, well, you’ve seen war. You know what amputation looks like. You’ve seen the remains of structures designed to stand forever, and you’re strong like them — casts and gauze in all the weak spots because you remember the pain of breaking them — but those were blows dealt without the complication of loving the bombs behind them.

Tom is the green on your robes, the dragon pox tinge you sometimes think never truly faded when you look in the mirror too long, and all the shades you never imagined. Apple, jade, moss. The beginnings of emerald. (No, he couldn’t be that.)

You wonder what the world would look like if he stole those colours back, and it’s much worse than some brutal decimation; it would leave you with too much. You would just be you without him.

So you love him into June like you always do, and you pluck his Prefect badge off on the last day of school and tell him it makes you jealous like a joke when it’s half-true.

It’s raining when you walk to the train together, miserable for what should be summer but not at all remarkable in Scotland. Tom wipes it from your cheek. Your wrists are sore from vanishing bits and bobbles all night while you still can, never truly prepared for three months without magic, and you curl into your seat as soon as you’re in it. Tom wakes you up when you arrive back in London, startling you to find that you fell asleep at all.

It rains a lot that summer. There’s nothing much to see in the city and you can’t get anywhere else (you note: the Trace cares little about broomsticks but you can’t afford one of your own and flying might be the only thing Tom is bad at) so you’re stuck to the library again with a noseful of old paper and a certain prose that magical literature cannot replicate. You theorise a lifetime of reckoning with the mundane forces one to be more creative.

Perhaps it’s the cold that makes you sick. Perhaps it’s the state of your meals. Either way, your final weeks before sixth year are hell. Biblical, blazing hell.

The nurses aren’t sure what it is — another influenza epidemic you’re the first in the orphanage to catch — but they isolate you immediately and there’s not much care they can offer.

You hear Tom arguing with one of them outside your door but can’t make out the words. Everything is dizzy, sweaty, halfway to unconsciousness but without its relief. You’d take dragon pox over this.

Some days later (though you can’t be sure because it feels like bloody centuries), he’s at your bedside, and you think even if you were lucid enough to ask what horrible thing he’d done to change the nurses’ minds, you wouldn’t.

But you know he’s not beyond breaking wizarding law, because he’s muttering healing spells with a hand to your damp forehead, and you hazily find yourself reaching for him, trying to shake your head no.

“Not allowed,” you mumble. Your throat is sore and your nose is stuffy. You sound terrible and you probably look worse.

Tom is slightly blurry but you think he’s staring at you. You know if he is it’s with the utmost incredulity.

“Not allowed,” he repeats slowly. It’s very easy to picture him clenching his jaw. “I wonder, if the Trace is so exact that it can detect all forms of magic, it can’t also detect malady. You’re burning — and I’m to consider whether saving your life might be illegal?”

He’s angry. He’s angrier than you’ve seen in a long time; and you can actually see it now. His magic courses through you and your vision clears, bit by bit, until your depth perception steadies and you realise he’s closer than you thought. His jaw is, in fact, clenched.

You move to catch his wrist and manage it this time. “Tom.”

“Don’t argue,” he says thinly.

“You’ll get sick.”

His face is far too neutral for the way his fingers stroke your damp cheek. “Hm. Then it’s a good thing you’d break the law for me too.”

Of course he’s right — you love him. Which makes it a good thing he doesn’t get sick.

Some of the younger children do. The fever comes overnight for a girl who wasn’t in the orphanage last year, and it takes her by the next.

When you get back on the train to Hogwarts, the virus is circulating Britain and you’re livid.

What Tom said is true; you consider the Trace’s precision and the details of the laws on underage magic — how one of the technicalities is that a young witch or wizard may be absolved of the consequences if the circumstances are life-threatening. You think about how it supposedly doesn’t care about broom-riding or Portkeys or Floo travel, and if the Trace is that complex, surely it understands sickness.

You only wonder if the Ministry would understand it. There haven’t been any epidemics in the wizarding world since Gorsemoor cured dragon pox in the sixteenth century, and when there isn’t healing magic there are antidotes and Pepper-Ups and herbs that muggles simply don’t have. The fatality of a fever of all things is not something you imagine could be comprehended by the sort of people who sent you and Tom back to London in the wake of the Blitz.

Of course, the Ministry hasn't written to you, you haven’t been forced in front of a representative from the Improper Use office, and you have no real reason to be upset.

You are regardless.

It shouldn’t even be a thought: you immolating into oblivion protesting rescue because one of you might get in trouble for it.

A world you’ve never much cared for is blanketed in ash and its people are dying and you can’t help them. A girl is dead. You’ll return next summer and there will certainly be more.

Life is for the magical, you find. The muggles can burn.

It’s what makes you start to panic this year, knowing you’ve only got one more after it. You have no idea what you’re going to do after school, and it doesn’t help that Tom doesn’t appear to share the sentiment. He’s got Head Boy in the bag and when he isn’t with you he’s with Abraxas, who can surely provide him connections if whatever game Tom is playing at works (and you have no doubt it will), but it’s like you said in third year: that isn’t enough for you.

You remember with a small ache that you no longer means you and him.

And then — it makes sense. You feel incredibly stupid.

“You told him, didn’t you?” you ask Tom the first opportunity you can get him alone, in the glum blue light of the Deathday ballroom on your way back from supper.

He sighs like it’s a conversation he’d hoped to put off for longer. “You’re referring to Abraxas, I presume?”

“You’re referring to — yes, you prick, I’m referring to Abraxas. Of course I’m referring to Abraxas, or are there others? Dolohov and Nott seem unusually enthralled by you, now that I think about it.”

“And for a reason I’m supposed to be aware of, this is an error on my part. Should I be apologising?”

“Why did you tell him, Tom?!”

“Why?” he deadpans.

You throw your hands up. “Oh, for fuck’s sake.”

“Shall I provide you with my itinerary as well? Would you accompany me as I tour the third-years around Hogsmeade? Or can you do me the favour of trusting me to make my own decisions with the nature of my ancestry?”

“You’re keeping something from me and there’s a reason,” you say, stepping closer to him, “and forgive me if I want to know what it is when you were willing to tell me you’re the Heir of Slytherin and you can talk to snakes. What — what could possibly be bigger than that?”

Tom returns your approach with one of his own. His eyes are steady, dark, thick with lashes and you can’t reminisce on the details of the rest of him because that would be strange for a friend to do. Stranger to do it now, when you’re angry with him and there’s two sleeping ghosts in the corner and he’s framed by deep indigoes like the ripples in the Black Lake and — you’re doing it anyway.

To be short, he’s close, he’s very beautiful, and sometimes you despise him.

“Trust me,” he says again, without the derision of the last time. “This will change things for us.”

You frown, but it’s a weak upset in contrast to the explosion you came in here willing to make. There were at least twenty questions you meant to ask and you only managed one.

You are not his keeper. You know that.

“Change them for the better, Tom,” you say on a sigh.

He blinks, and you think he’ll respond with a nod or a slightly offended ‘of course’ but he does not. He blinks and he just keeps looking at you. It’s disarming. It probably resembles the way you often look at him. There’s a rationale somewhere; you never see each other anymore, life is so incredibly busy, maybe he’s forgotten what you look like.

And he does nod, finally, but he does it with his thumb brushing the corner of your lip.

What? Sorry. What’s going on?

He pulls it away like he’s heard you. “You had something.”

You’re almost positive you did not.

Transfiguration this year brings Conjuration, which is an advanced and welcome distraction, and even more exciting when you consider no longer having to Vanish things you have no idea how to bring back. Dumbledore’s is one of three N.E.W.T classes you’re taking — Defence Against the Dark Arts and Alchemy besides. It’s easily your favourite.

You share it with eleven other Slytherins and twelve Ravenclaws. Four of them are muggle-born, and it’s hard to describe the ease you feel among them because you don’t think you’ve ever had anything resembling ease with anyone but Tom.

Your schedule is more crammed than it’s ever been, but it’s good. Two of the Ravenclaw girls invite you to Hogsmeade every other weekend, you share butterbeers when you can afford one, you study until you collapse, you take Dumbledore’s extra assignments and consider trying out for Chaser on one of your more restless evenings before waking up in the morning and resolving there is such as thing as too much of a good thing. Best not to get ahead of yourself.

Your contentment is remedied quickly.

Someone is found unresponsive in the dungeons. Dippet makes an announcement at breakfast that the boy isn’t dead, rather, petrified. No one is quite sure the cause, but the Headmaster warns a few minor precautions, suggests a buddy system, and says that after dinner studying should remain in everyone’s respective common rooms rather than the courtyards or library.

You know next to nothing about petrification, but the victim is muggle-born, and you suspect it was the result of a poorly performed statue curse by one of the many blood zealots in your house. The whole thing makes you hold onto your wand a smidge tighter, but you’re adamant not to let it drive you to paranoia like it would have a few years ago.

Tom nods at your theory when you manage to escape to the Black Lake together in November.

“That isn’t unreasonable,” he says. High praise.

You sink into the moss, sighing. “Do you think there’ll be more?”

He looks out onto the lake, the lapping waves, the crystalline beads that furrow them, midnight algae and flotsam you don’t think you belong to anymore.

You peer up at his silhouette in the dark. “Do you think whoever did it will do it again, I mean?”

“I don’t know,” he says finally, and after another pause: “but I don’t think it would be you.”

“How’s that?”

“No one would be senseless enough to try.”

And he sinks beside you with that, breath shaping the cold in steady, rhythmic clouds while yours are scattered. His robes brush yours and you take his arm with a sleepy hum, tracing patterns in the stars until your eyes feel heavy and he insists on taking you back to your dormitories.

One of the Ravenclaw girls, Marigold Wright, distracts you with a spare blue scarf and an invitation to her next Quidditch match. You watch from the stands and cheer as she catches the snitch to beat Gryffindor.

It’s a bit strange — having a distraction — having a friend. Mari is kind, smart, a good study partner who’s as keen on stepping into the advanced theoretics of Human Transfiguration a year early as you are. She’s funny in a vulgar way, introduces you to all her friends, shows you the best way to sneak into the kitchens, and you sometimes wonder if she was sorted wrong, but — her methods are creative, and she’s definitely intelligent. She’s also definitely not Tom.

You see less and less of him and more of her, Dumbledore, the Ravenclaw common room and the pages of progressive Transfiguration methodologies. He sees less of you and more of Abraxas, Dolohov and Nott and all the other purebloods, Slughorn’s soirées and Prefect meetings that cut into meals.

It happens again.

Second floor lavatory. A girl called Myrtle Warren. She isn’t petrified.

There’s a vigil the following week and her parents are there, two muggles whose sobs wrack the Great Hall even as the students clear out. Flowers descend from the charmed ceiling, little bluebells and white chrysanthemums.

You cry that night. You can’t remember the last time you cried.

This time, you don’t have to seek Tom out. He catches you on your way back from Alchemy and brings you to the Deathday ballroom with a melancholy glance in your direction that you don't hesitate to follow. You realise it’s an odd place to continue to end up in, but no one else goes there and you suppose that makes it yours.

You’ve seen Tom skinny and sickly and olive green, but today his eyes are circled with veined violets and the lack of summer sun this year has whittled him grey once more. He’s still beautiful. He’ll always be beautiful. But he’s tired and — sad — and for the six years you’ve known him you aren’t quite sure what to do with that.

You don’t spend too long pondering it. You just hug him with the dawning newness of a thing like that; a thing you’ve never done, and never really thought to do. (You ask yourself in bewilderment how you’ve never thought to do it before.)

He’s warm. He’s uncertain. He doesn’t reciprocate immediately.

And then he does, and you understand without caveats or concerns that you stopped having a choice in your destruction the moment you chose him. He’s home, and that’s going to ruin you one day.

Your arms tighten around him and his around you, the rhythm of his breath holding you to earth when you begin to float away. Nothing makes sense in this moment but the mercy that in all the death you’ve seen, you swear to God you’ll never see his. As long as you’re alive, he must be too.

And there’s something to be said about the innate self-slaughter of loving a person (of loving Tom Riddle, especially): that it’ll cleave you in two, that you’ll say feeble things in his embrace that you should be above saying, like ‘I’m scared’, that his hand will find the back of your head and he'll tell you he knows, that that should not feel like enough but it will be. You’ll clasp your hands under black robes and hold this singular embrace together by the faulty adhesive of your fingers. Maybe you’ll cry again, like your body can suddenly comprehend its capacity for it and is making up for lost time.

The first sign that something is wrong, more than the obvious grievance of the death itself, is the Ministry’s happy acceptance of Rubeus Hagrid as the culprit.

The boy is maybe fourteen years old, half-blood — half human, mind — and no one has a bad word to say about him other than he likes to keep eccentric pets. Which leads you to wonder what pet he possessed with the ability to petrify one student and kill another and what cause he’d have for it in the first place besides two terrible, miraculous accidents.

That question draws an even stranger path. Mari says over butterbeers (on her, bless her soul) that she read somewhere years ago that Gorgons can induce petrification, but that she doesn’t remember much else.

One of the boys in DADA says that his father’s an auror, and heard from him that Hagrid’s pet was some sort of arachnid. Tom deducts five points from his house after class with a scowl on his pale face, muttering about conspiracy.

The second sign that something is wrong is that only one of those things would need to be true for the entire case on Hagrid to be called into question. If Mari’s memory serves right, how the hell did Hagrid come into ownership of a Gorgon? (Could Gorgons even be owned?) If the auror’s son is worth your credence, then what species of arachnid is capable of petrification?

You take to the library.

Unsure of where to begin and hesitant to draw attention, your research lingers into Christmas break and stalls some of your extracurriculars in Transfiguration. Tom is busy enough not to notice the new step in your routine, and you’re grateful not to have him breathing down your back, telling you you’re looking in the wrong places or you shouldn’t be looking at all.

The third sign is the end.

You wish to retract it all. There are time-turners and memory charms and potions that could dizzy you enough to manipulate the truth; there is anything but this. You’d suffer the consequences for the bliss of loving him with one more day before the ruin — you’d write it down to remember through the fog: look at him, duel him without wanting to hurt him, kiss him to know that you did it at least once, have him, be had. You never will again.

He’d shown you the adder. He’d joked about the Chamber of Secrets. He’d spent months disappearing with Abraxas, earning the trust of the sons of the Sacred Twenty Eight.

And he’d killed Myrtle Warren.

So it’s statue curses and Gorgons and Tom — speaking to serpents when no one else can, buttressed by pureblood boys who want people like you dead.

Don’t become like them now that you’re not like me.

He’s something else entirely.

What do you do in a moment like this? Panting into an empty library at a revelation you wish you could unknow, fingers digging into the hickory of your desk — another memory carved among the initials and hearts; how do you stand from your chair and leave like the world outside this room is the same as it was when you entered? There’s nothing to orbit. You are cosmic debris, tea dregs in a barren cup, flotsam.

You stand; and you tell no one. Not even Tom.

His presence in your life is so infrequent that you don’t even have to come up with excuses for your distance until three weeks after your discovery when you’re paired together in DADA to practise stretching jinxes.

You almost laugh. He’s standing beside you, tall (lanky like he was when he was a boy if you look long enough) and serious, and you love him without knowing who he is anymore. You’ve skirted corners to avoid him and sat with Mari during lunch and breakfast like he’s some scorned lover to escape confrontation from and not someone who held you through a grief inflicted by his hand.

“You look tired,” he says, inspecting the daisy you’d been tasked to elongate.

You glance at him. You are tired. It’s exhaustive, bone-deep, aching like nothing you’ve ever known, and maybe that’s why you can look at him and smile sadly instead of thrashing against his chest screaming for what he did. You suppose it happens enough in your head to satisfy. When you can sleep, you sleep to the thought of it. The waking moments are just blank.

“Mhm,” you hum, transfiguring the daisy stem back to its regular length.

Tom observes it with curious eyes. “You’re getting good at that.”

“I’ve been good at it.”

His lips turn, a small frown before he puts it away. You make the observation that he’s tired too; there are still bags under his eyes and his hands tremble ever-so-slightly with his wand when he loosens his grip on it.

His own doing and still you flicker with some relentless hope that he's drowning in regret.

“Sorry,” you say. A ridiculous thing. Do you intend to slowly push him from your life with weak disinterest and diverging academic avenues? As if he were something extricable. He’d never let you.

You’ll have to confront him, and that’s a revelation that holds its weight on your chest until you think you'll suffocate under it.

You’re in the blue light of the Deathday ballroom with a face you've never worn before when it happens, deep into spring, and you know then that you were wrong all those years ago.

He sees all of you.

Takes you in in the flash of a second and maybe it’s your quivering jaw that reveals you or the flint of betrayal in your eyes waiting to be struck and lit. Yes, you were wrong — Tom Riddle knows you at every atom too.

“Are you going to let me explain?" he asks before any hello. His jaw is tight but there’s nothing else to go on to judge his disposition. He's settling into impassivity like an animal drawing its shell. You will not be allowed in if you're going to make it hurt, and you might be the only one who can.

“Explain," you copy with a hard exhale, “Just tell me it wasn’t you. That’s all there is to say."

He stares at you. There’s nothing there.

“Tell me, Tom.”

Your breath catches on an automatic please but you don’t want to offer him that.

“I cannot.”

Then make me forget, you want to scream. Let it be summer. Let us work for pennies and breadcrumbs and be no one together.

It’s late winter and it’s too cold.

“You killed her,” you say quietly.

“If I told you I did not wish for it, would you even believe me?”

“What are you… so it was an accident?”

“There was — an opportunity presented itself that may never have come again; that does not mean I don’t find the nature of it regrettable.”

“Regrettable.” You’re laughing or crying or both, and you must look unwell. Halfway out of your mind.

He’s so composed in the face of it that it only makes you more incensed.

“You told me to change things —”

“You killed someone! Can you understand that?”

“You nearly died,” he hisses, “and if I am to apologise for recognizing it only as the first of many times, I will not. If I am to apologise for doing whatever is necessary to prevent it, I will not. The hand we were dealt will not be the hand we die to — so yes, I understand it. And one day so will you.”

“Don't," you spit, and your anger must look pathetic under your welling tears. “Don't you dare tell me that this was for me.”

“Do you want me to lie?”

“What could her death possibly bring me, Tom?”

“Her death is the first step to —”

“God, stop dancing around the fucking question!” Both hands have wound their way to your head, clutching at your skull like the brain matter might spill through one of the cracks he’s wearing down. “Just… tell me.”

“You recall Godelot's work," he says stiffly. The question of it takes you by surprise, peels the moment back like the rim of a fruit and you're left uncertain.

All you can do is nod, arms falling to cross over your chest.

“There was one form of magic he refused quite concisely to impart. I searched the Restricted Section for days, and under Dumbledore's watch that was not an easy thing to do."

You stole from him, you're urged to remind him, but it's something you'd say with a nudge of annoyance and a roll of your eyes. Such admonishment is small and far away.

“I found it at last in one of the repositories," he goes on, “Secrets of the Darkest Art."

“...What?"

“It's called a Horcrux,” he says. “Murder, by nature, splits the soul. The Horcrux simply makes use of the act; puts the soul fragment into something imperishable so that it is protected, rather than abandoned. In turn, your life cannot be taken. By malady, by magic, by sword — the vessel is destroyed but the soul lives on.”

You blink, feeling dizzy. “Myrtle was the sacrifice.”

“Myrtle was there,” Tom remedies.

“How lucky for you.”

“The circumstances could be ameliorated if one were to be made for you. I would have preferred it be someone who deserves it.”

“For — you’d do it again? Again, Tom?”

His brows crease, and even his upset seems contrived. There’s this barricade he’s placed that you, in all your infallible knowing of him, cannot puncture. It’s agony to begin to question what he could possibly be keeping from you in a confession like this.

“You killed someone, Tom. You — I would never ask you to do that. I would never live at the cost of someone else."

“No, you would not,” he agrees, though he shakes his head like it’s incredulous of you. “Do you think, even if I knew it were certain, a summons from the Ministry would have stopped me from saving you this summer? Do you suppose the threat of punishment would cause me to waver at that moment? I know it would not hinder you. So, you have your lines and I have mine — you never needed to ask.”

And now it hurts. The emptiness clears and you can't stand yourself for crying, but you do. It comes out in ragged, breathless sobs, clasped behind your palm as you turn away from him.

You've loved him since you were eleven. It's always been you two — it was always supposed to be you two. What is there to say to him? He's blurring in your periphery like in the midst of your sickness, and there's nothing he can do to heal you this time. Your vision will clear and Myrtle Warren will still be dead. He'll still be a stranger in the face of the boy you love.

“Why," you whine, a wet, hollow stain in your voice you've never cried enough to hear before. “Myrtle was — wasn't — uh —" You swallow, hysterics severing your words. You can't really think right now. Your body wobbles and your head feels puffy and hot. This might be shock.

Tom scowls like it irritates him to watch you push yourself, like this is just the unfortunate effect of you depleting your energy in a duel, not eating correctly, treating yourself carelessly.

Of course you can't stand or talk or think. You're you, contemplating a life without him.

“Sit," he says in frustration. You smack his hand away when he reaches for you, but the world has turned a shade darker and you're slipping into it.

He tugs a chair towards you with a silent charge and a reprimand, and your body doesn’t possess the wherewithal not to collapse into it the second it’s under you.

After a moment you can speak again, shaking hands steadied by your knees. “Did you… did you think I wouldn't find out? You know, the only thing that can petrify someone besides a serpent is a Gorgon. And — where would Rubeus Hagrid have found one of those?"

“I thought I would have time.”

“To come up with a good lie? Something I’d sympathise with?”

He bites his cheek. “Evidently the particulars matter little to you.”

Fuck him. “Fuck you.”

“Very cogent.”

“No, fuck you, Tom. We could have — we only had a year left and then we could — we could've done anything we wanted." You're crying again. You don't have the energy to be embarrassed. “And you chose this."

He’s indignant as he steps closer. “With what money? For what life? We are better than all of them and it’s never mattered. It never will; you know that. You told me that. You’re angry now, but you must know the truth of it. I would not forsake you. I would not lose you.”

You blink up at him, mouth stuck with some cottony feeling and cheeks stiff from crying.

“You have lost me, Tom."

He stills as if suspended. Some maceration must follow but it doesn’t.

You stand on weak legs to look him in the eyes. You wonder if he can see the love in yours. You wonder if he knows you will walk away despite it. (Of course he does. You’ve never lied to him.)

You think about how his fingers seem to always find their way to your cheek and you put yours to his. The bone there is sharp, but the skin is soft. Boyish.

There isn't a word for a goodbye like this. It shouldn't exist and so it doesn't. You just leave.

You fail your N.E.W.T courses. Quite spectacularly.

Mari sits beside you on the train with a soothing hand on your shoulder, and doesn’t ask what’s rendered you into a comatose husk since March. There’s no crying. You chew numbly on soft caramels from the trolley and stare out the window onto the hills.

That summer is spent in your bedroom unless you’re forced elsewhere. A new girl with skin so white it’s nearly translucent sleeps in the bed beside yours, taking meals on trays like you did in your first days here, tracing the cracks in the tiles, humming to herself in the dark. She makes you feel less pathetic for doing much the same.

You’d been right in your assumption that there would be more dead upon your return, and wrong that there would be more empty rooms. There are always more orphans being made.

And then you receive a letter. It isn’t delivered by owl (only for secrecy, you assume, because there are no muggles who’d be writing to you) but it’s stamped with a vaguely familiar crest. Not Hogwarts’ waxen seal, but something undoubtedly magical. A cockroach and a cup, you think, squinting. Transfiguration.

You tear the envelope open and pull the letter out.

It’s from Dumbledore. Some of it melds together, but the key words stand out.

Spoken to Dippet… Exceptional promise… N.E.W.Ts… May be reconsidered… Upon dispensation… Be well.

Be well.

You are not. You are something half-drowned and half-burned, never enough of one to quell the effects of the other. Sunlight is sparse through your side of the orphanage. On the radio, they warn a pattern of one bomb every second hour. The only other warning is the sound when they fly overhead, and if you can’t run fast enough —

You write your answer in a crowded tube station with a spotty ballpoint pen. Tom is there, looking between you, the dust, and your shaking hands as if to say: tell me I was wrong.

Some of your letter melds together but the key words stand out.

Thank you, Sir. Whatever you need.

It’s a shock that you live to seventh year. It’s a shock that you do it without him — though he watches, and in his gaze you feel regressed. You’re alive, yes, but there’s something there… his dead weight, death-grip; his haunting. They always speak of the dead as something heavy. Something that holds onto you even after it’s gone.

You find that to be true.

Dippet’s condition that you remain in Dumbledore’s N.E.W.T class is that you achieve more than the standard requirement. Essentially, your final exam will be much harder than everyone else's: Human Transfiguration, mastery of petty Transformation (through the means of Wizard’s Chess pieces), Conjuration and Vanishment of various delicate objects — all done nonverbally.

Even Dumbledore seems sceptical, but it translates to more rigorous practise rather than resignation, assignments he doesn’t even task to Mari, though she’s just as good, and you can’t begin to understand why he cares so much.

“I’ll entrust you with these while I’m away,” he says before Christmas break, sliding a sheet of parchment your way with a flick of his wand.

You frown, unfolding it. His instructions are always short now — you’ve learned to decode his meaning well enough without much exposition.

Teacup to gerbil — to cat, and inverse.

Inanimatus Conjurus spell (cockroach and cup, as instructed) to be Vanished when perfected.

Study Antar’s Doctrine. Miss Wright will act as your partner.

Due February.

It’s far too much to be done in that time. “Sir?”

Dumbledore lugs a messenger bag over his shoulder that appears small, but he carries it in such a way you suspect it’s magically extended. He smiles wistfully, pushing his spectacles up the bridge of his nose. “You know, I often regret how much this war asks of me. A consequence of my own doing.”

Right — Grindelwald. Sometimes you forget between awaiting the next muggle paper. War is everywhere.

You nod. “I hope… Good luck, Sir.”

Another half-smile as he twists open a jar of Floo Powder, and then he shakes his head with something you almost decipher as amusement. A brittle sort. Tired. “Good luck to you.”

And then he’s gone, in a swath of green flames that do nothing to inspire any desire for Floo travel in you.