#writing descriptions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I find myself struggling to describe environment’s. I always describe what characters do or what the character is thinking, but always forget to describe the space around them, usually because I feel like I’ve made the paragraph too long already. Any help?

Nailing the sweet spot between descriptions and actions is very hard, but a tip I found very useful when writing is this: make your characters interact with the space around them.

A big part of describing things is to make the reader feel like they are in the scene with the characters. If a specific details is not needed, or the characters wouldn't notice it, just ignore it (ex. Do the readers really need to know that the lightbulbs emits yellow light? Is it fundamental for their immersion to learn about the invisible-to-the-charachter spider hiding behind the curtain?) .

Another trick is what I call implied description. Instead of ""wasting"" two lines describing the table and the chair in the middle of the room try incorporate it in the actions (ex. B walked in the room just to see A already sitting at the old oak table. B gripped the backrest of the opposite chair, the sharp edges digging into his palm.) or even put it in the middle of a dialogue ("What fo you want?" asked A, hidden finger pulling at the tablecloth in anxiety. "Just to have a quick chit-chat" B sat heavily on the chair to his left, plastic groaning at the weight "like any old friend would do.". B's tie was the same deep-wine colors of the drapes obscuring the windows.).

Of course this is not a one-size-fit-all solution, sometimes there is no alternative but writing four paragraphs of descriptions, as writers we have to live with that. And sometimes our writing style simply lends itself towards a more descriptive-heavy writing! There is nothing bad in that either (ex. literally the whole "Wheel of times" serie)!

So, in the end, I guess my advice is to embrace your writing style and to cut your description into bite-size pieces to then scatter around the scene.

I really hope this will help you some @nxrthwind! Good writing!

#anyway yeah#descriptions are Hard#personally I have a very description-heavy style#I guess when you reach a certain point you just have to lie in the grave you dug for yourself#and hope someone will find it pleasent to look at#(or read in this case)#writing#writers#writer#writers woes#wip#writing descriptions

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to pull off descriptions

New authors always describe the scene and place every object on the stage before they press the play button of their novels. And I feel that it happens because we live in a world filled with visual media like comics and films, which heavily influence our prose.

In visual media, it’s really easy to set the scene—you just show where every object is, doesn’t matter if they’re a part of the action about to come or not. But prose is quite different from comics and films. You can’t just set the scene and expect the reader to wait for you to start action of the novel. You just begin the scene with action, making sure your reader is glued to the page.

And now that begs the question—if not at the beginning, where do you describe the scene? Am I saying you should not use descriptions and details at all? Hell naw! I’m just saying the way you’re doing it is wrong—there’s a smarter way to pull off descriptions. And I’m here to teach that to you.

***

#01 - What are descriptions?

Let’s start with the basics—what are descriptions? How do you define descriptions? Or details, for that matter? And what do the words include?

Descriptions refer to… descriptions. It’s that part of your prose where you’re not describing something—the appearance of an object, perhaps. Mostly, we mean scene-descriptions when we use the term, but descriptions are more than just scene-descriptions.

Descriptions include appearances of characters too. Let’s call that character-descriptions.

Both scene-descriptions and character-descriptions are forms of descriptions that we regularly use in our prose. We mostly use them at the beginning of the scene—just out of habit.

Authors, especially the newer ones, feel that they need to describe each and every nook and cranny of the place or character so they can be visualized clearly by their readers, right as the authors themselves visualized them. And they do that at the start of the scene because how can you visualize a scene when you don’t know how the scene looks first.

And that’s why your prose is filled with how the clouds look or what lights are on the room before you even start with the dialogues and action. But the first paragraph doesn’t need to be a simple scene-description—it makes your prose formulaic and predictable. And boring. Let me help you with this.

***

#02 - Get in your narrator’s head

The prose may have many MCs, but a piece of prose only has a single narrator. And these days, that’s mostly one of the characters of your story. Who uses third-person omniscient narrator these days anyway? If that’s you, change your habits.

Anyway, know your narrator. Flesh out their character. And then internalize them—their speech and stuff like that. Internalize your narrator to such an extent that you can write prose from their point-of-view.

Now, I don’t mean to say that only your narrator should be at the center of the scene—far from it. What I mean is you should get into your narrator’s head.

You do not describe a scene from the eyes of the author—you—but from the eyes of the narrator. You see from their eyes, and understand what they’re noticing. And then you write that.

Start your scene with what the narrator is looking at.

For example,

The dark clouds had covered the sky that day. The whole classroom was in shades of gray—quite unusual for someone like Sara who was used to the sun. She felt the gloom the day had brought with it—the gloom that no one else in her class knew of.

She never had happy times under the clouds like that. Rain made her sad. Rain made her yearn for something she couldn’t put into words. What was it that she was living for? Money? Happiness?

As she stared at the sky through the window, she was lost in her own quiet little corner. Both money and happiness—and even everything else—were temporary. All of it would leave her one day, then come back, then leave, then come back, like the waves of an ocean far away from any human civilization in sight.

All of it would come and go—like rain, it’d fall on her, like rain, it’d evaporate without proof.

And suddenly, drops of water began hitting the window.

You know it was a cloudy day, where it could rain anytime soon. You know that for other students, it didn’t really matter, but Sara felt really depressed because of the weather that day. You know Sara was at the corner, dealing with her emotions alone.

It’s far better than this,

The dark clouds covered the sky that day. It could rain anytime soon.

From her seat at the corner of the room, Sara stared at the sky that made everything gray that day. She…

The main reason it doesn’t work is that you describe the scene in the first paragraph, but it’s devoid of any emotions. Of any flavor. It’s like a factual weather report of the day. That’s what you don’t want to do—write descriptions in a factual tone.

If you want to pull off the prior one, get to your narrator’s head. See from their eyes, think from their brain. Understand what they’re experiencing, and then write that experience from their POV.

Sara didn’t care what everyone was wearing—they were all probably in their school uniforms, obviously, so I didn’t describe that. Sara didn’t focus on how big the classroom was, or how filled, or what everybody was doing. Sara was just looking at the clouds and the clouds alone, hearing everybody just living their normal days, so I mentioned just those things.

As the author, you need to understand that only you, the author are the know-it-all about the scene, not your narrator. And that you’re different from your narrator.

Write as a narrator, not as an author.

***

#03 - Filler Words

This brings me to filler words. Now, hearing my advice, you might start writing something like this,

Sarah noticed the dark clouds through the window. She saw that they’d saturated the place gray.

Fillers words like “see”, “notice”, “stare”, “hear” should be ignored. But many authors who begin writing from the POV of the characters start using these verbs to describe what the character is experiencing.

But remember, the character is not cognizant of the fact that they’re seeing a dark cloud, just that it’s a dark cloud. You don’t need these filler words—straight up describe what the character is seeing, instead of describing that the character is seeing.

Just write,

There were dark clouds on the other end of the window, which saturated the place gray.

Sarah is still seeing the clouds, yeah. But we’re looking from her eyes, and her eyes ain’t noticing that she’s noticing the clouds.

It’s kinda confusing, but it’s an important mistake to avoid. Filler words can really make your writing sound more amateurish than before and take away the experience of the reader, because the reader wants to see through the narrator’s eyes, not that the narrator is seeing.

***

#04 - Characters

Character-descriptions are a lot harder to pull off than scene-descriptions. Because it’s really confusing to know when to describe them, their clothing, their appearances, and what to tell and what not to.

For characters, you can give a full description of their looks. Keep it concise and clear, so that your readers can get a pretty good idea of the character with so few words that they don’t notice you’ve stopped action for a while.

Or can show your narrator scanning the character, and what they noticed about them.

Both these two tricks only work when a character is shown first time to the readers. After that, you don’t really talk about their clothing or face anymore.

Until there’s something out of the ordinary about your character.

What do I mean by that? See, you’ve described the face and clothes of the character, and the next time they appear, the reader is gonna imagine the character in a similar set of clothes, with the same face and appearance that they had the first time. Therefore, any time other than the first, you don’t go into detail about the character again. But, if something about your character is out of ordinary—there are bruises on their face, scars, or a change in the way they dress—describe it to the reader. That’s because your narrator may notice these little changes.

***

#05 - Clothing

Clothing is a special case. Some new authors describe the clothes of the characters when they’re describing the character every time the reader sees them. So, I wanna help you with this.

Clothing can be a way to show something about your character—a character with a well-ironed business suit is gonna be different from a character with tight jeans and baggy t-shirt. Therefore, only use clothing to tell something unique about the character.

Refrain from describing the clothing of characters that dress like most others. Like, in a school, it’s obvious that all characters are wearing school uniforms. Also, a normal teenage boy may wear t-shirts and denim jeans. If your character is this, no need to describe their clothing—anything the reader would be imagining is fine.

Refrain from describing the clothing of one-dimensional side-characters—there’s a high chance you’ve not really created them well enough that they have clothing that differs from the expectations of the readers. We all know what waiters wear, or what a college guy who was just passing by in the scene would be wearing.

You may describe the clothing of the important character in the story, but only in the first appearance. After that, describe their clothes only if the clothes seem really, really different from the first time. And stop describing their clothes if you’ve set your character well enough in the story that your readers know what to expect from them in normal circumstances—then, describe clothes only when they’re really, really different from their usual forms of clothing.

***

#06 - Conclusion

I think there was so much I had to say in this article, but I didn’t do a good job. However, I said all that I wanted to say. I hope you guys liked the article and it helps you in one way or the other.

And please subscribe if you want more articles like this straight in your inbox!

#writers and poets#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writeblr#writing#creative writing#writing resources#writing advice#writing tips#writing descriptions#character descriptions

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

describing your main character in first person (+ examples)

request from instagram

comparisons: using another character as a point of reference

our eyes were both blue, but hers were piercing chips of sapphire, while mine were more the color of dishwater.

they stopped growing in middle school. i didn’t. now, though i wouldn’t consider myself a giant by any means, i tower over them with ease.

i got my father’s squarish jawline, but he had a nose to match, whereas my face seemed more like a mismatched collage of features from both parents.

dialogue: other characters commenting on the mc’s appearance

“i don’t know,” she says. “you have a bit more of a pear-shaped build, so i think an empire waistline would look good on you.”

my father looked at me and sighed. “a mullet is... definitely a choice.”

“huh,” he said, reaching out to poke my upper forearm. “i always thought your tattoo was meant to be some kind of weird abstract flower.”

action: the main character interacts with an aspect of their appearance to let the reader know it’s there

i rolled up the sleeves of my jacket. it was a faded green thing with rips along the elbows from a few too many falls on the pavement, and i seldom took it off.

i pushed my glasses back up the bridge of my nose, cursing their thick lenses.

my nails were chipped, but i gnawed at them anyway.

i shook the stray curls out of my eyes.

showing (related to action) something occurs within the story that naturally reveals a part of the character’s appearance

the man gives me a once-over, then a twice-over, and smiles at me. i tuck a loose blonde strand behind my ear and smile back.

the white silk contrasts starkly with my skin.

even with heels, the book was too high up for me to reach.

i hold each watch up to my face, comparing it against my undertones, before securing the silver one about my wrist.

reflections: the character sees part or all of their appearance in a reflective surface (can be overused)

my reflection startles me with its puffy, reddened eyes and tear-streaked mascara and ruined lipstick. i looked so put-together at the start of the night.

i held up the knife, angling it so that my own piercing green eyes stared back at me.

the rain last night left behind still and scattered puddles. as i pass them on my way to work, i am followed by my hunched silhouette, darkly clothed, reflected dozens of times.

advice

break your descriptions up into smaller, more digestible bits and scatter them throughout the beginning of the story.

don’t wait too long to describe your mc, as you might be ruining the reader’s established mental image if you introduce a key detail later on.

don’t worry too much! if a book is first-person, you don’t need to agonize over the littlest parts of someone’s appearance. focus on the most important or noticeable parts (a scar, a facial feature, a limp, dyed hair, a prosthetic, etc.)

-----------------

like this post? buy me a ko-fi! | what's radio apocalypse?

#🌿 writing#writing advice#writing tips#descriptions#writing descriptions#character description#writing help#writing resources#writer tips#writing reference#fic writing

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

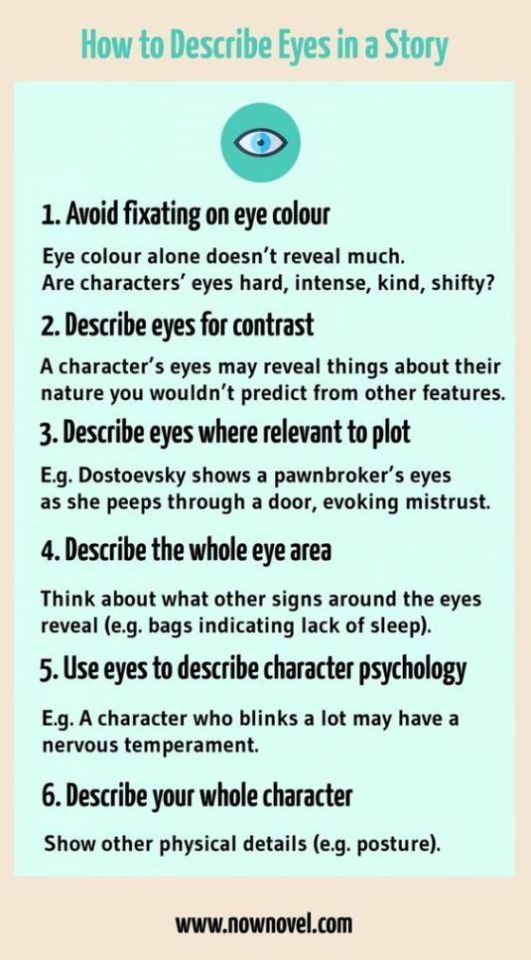

How to Describe Eyes in a Story

798 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are some good alternatives for idiot/dummy/etc? I want to be able to make fun of fictional characters without using ableist language

so far all I've found is stuff like dunderhead, blockhead, doofus, birdbain / featherbrain, numbskull, dimwit etc etc but I don't know if they're actually any better. What are some of your go-tos? thank you so much

Hey,

Any insult that makes fun of someone's intelligence will fall into the same trap, there's no real difference between "dummy" and most of the alternatives here.

Personally, as long as you're not calling an actually intellectually disabled (or not ID but otherwise significantly developmentally disabled) character an idiot/moron/imbecile/r-word (since these terms, specifically, are historically charged) I don't care like at all.

The only time I'd be actively offended by an abled character being called any of these is if it was either the R slur or just the term "intellectually disabled" being used as an insult, which it isn't.

An incredibly high amount of insults in English come from words surrounding or implying disability. "Lame" used to mean physically disabled, "moron" was invented by a eugenicist for eugenics reasons, then you got "crazy" and "insane", "smooth brain" if we are talking about modern insults (it is real disability called lissencephaly), "braindead"... List goes on.

Basically, not using words of ableist origin is a great goal (no sarcasm intended) but changing "stupid" to "small brained" just isn't much of a change. As a rule of thumb; if it got to do with either brain or skull it's probably just the same thing. Ableist terms do need to be phased out, but it's the sentiment that's the problem, not the actual word (in most cases, at least). Otherwise it's just a constant semantics treadmill that changes nothing and helps no one.

As I said, I don't really care if anyone is calling their abled blorbo an idiot and I feel pretty comfortable saying that most intellectually disabled people I know also don't. But if you want to use words that do actually avoid having an ableist basis then they need to insult something else than intelligence - preferably actions or opinions.

Hope this helps,

mod Sasza

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear writers, please describe your characters.

A lot of people seem to think that describing a character’s appearance is limited to skin color, eye color, hair color + style, and body type, but there’s so much more than that.

If you don’t know where to start, try thinking about each individual feature.

Eyes, for example; It’s great to know that your character has brown eyes, but what do they look like outside of that? Are they big, or small? Upturned, or downturned? Do they have any prominent features, like heavy dark circles? What about their eyelids; Are they monolids or double eyelids? What about the eyes’ general shape?

I’m not saying you need to go into detail about your characters’ nostrils and tear ducts, but give the reader something to work with outside of the basics.

Here’s some stuff to think about for other features, as well:

Nose - Is your character’s nose bridge high or low on their face? Is it more flat, or more defined? How wide or narrow is their nose? Long or short?

Mouth: What color are your character’s lips? How thick or thin are they? Are they horizontally long or narrow? Hell, are the corners of their mouth upturned or downturned?

Face shape: Does your character have a wider face or a slimmer one? Is this due to fat concentration or just their bone structure? What shape would you say most accurately represents your character’s face shape; Circular, triangular, etc? How long or short is your character’s face?

Other features: How high up on your character’s face are their brows? Their brow bone? How heavy and/or noticeable is their brow bone? What shape is their chin? Are their cheekbones prominent, or do they tend to blend in with the rest of the face?

Looking up references on sites like Pinterest can help with this a lot. If you find a person who looks sort of like your character, examine their face and what about it is similar or different to your vision for the character. What features stand out to you?

#writing#writeblr#writer#writers#aspiring author#writers on tumblr#author#writing advice#writing tips#authors#authors on tumblr#writing descriptions#writing discussion#novel writing

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Descriptions

I was just musing recently about this, so thought I’d share some bits about how I try to build compelling descriptions of scenes/environments. Normally I just post fan art but eh, diversifying lol.

Having an agenda

I found both reading and writing descriptions that if I don’t have an objective for them they end up feeling aimless and sometimes forgettable. I am always trying to build a narrative. It can be as simple as “this building is old/unused” or as complex as ‘contrasting a bright atmosphere with an underlying coldness as an allegory to a character’s crushing isolation in the face of their personal grief/pain’. What does every line and descriptive word contribute to what you’re trying to do? What emotions or vibes are you trying to evoke? How does every part of it tie together into a cohesive picture instead of a bunch of disparate parts?

2. Utilizing descriptions as a tool

descriptions inherently tend to center a story in a specific setting, or serve as our senses to experience the story alongside the characters — but I try to use it as more than that when possible. How you can use it may vary with what person you’re using, but even third person (what I typically use) descriptions can give you a glimpse into the headspace of your character. This can be really helpful when writing a character who isn’t very emotionally self aware, or a character who is stoic. I typically use this one of two ways.

First one is seeing through the eyes of the character. How do they see this other character? How does their emotions, history, etc affect their impressions about different settings? For example, a characters with religious trauma might have a more negative/emotionally loaded perspective when walking into a church which can manifest at different levels of subtlety within the description of the environment.

second one way is just to get the reader on the same page emotionally as a character. If the character is desperate, incorporate that emotions/vibe into your description of the setting or even of them. If they’re lonely invoke that, etc. Note that this can also be used for plot beats and not just character moments.

Also total side note, but I’d reccomend not taking any writing advice too seriously. Explore how people write their stuff, take little tidbits here and there when it speaks to you and your style, and toss aside anything that doesn’t work for you.

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

🚨Description, Momentum, and Tension; Or, How Not to Bore a Reader🚨

This was inspired by, of all things, horrible Booktok takes like the above.

You know, the ones where they say they will only read the dialogue because they just want to understand the plot and they blaze past any descriptions because they're apparently worthless?

I doubt I can change their minds, since such people allergic to actually, you know ... reading. BUT! There may be some salvageable ones yet.

Today, we're doing to discuss how to write exciting descriptions, and where to put them for maximum impact. Perhaps we'll get the Booktok girlies to read a book for fun instead of treating it like a school assignment.

Again, as always, this is just my opinion as someone who has been writing for a long time. And a lot.

Maybe you'll disagree, and that's fine. This is my opinion and my perspective. With that, let's go!

What do Description, Momentum, and Tension mean?

Description is anything that is not action or dialogue. It could be of a room, a character, a landscape, etc. Description can also include interiority, like stream of consciousness thoughts.

Momentum is the forward thrust of the plot. This is not the same as pacing, though it is related to it. When you have momentum, you are moving forward; that could be slowly or quickly, depending on what you need at the moment.

In general, momentum will ebb and flow throughout a story, same as you have less forward momentum when you're turning a corner in your car. You'll start out slowly and gradually pick up pace throughout the story, until something intense happens (like the climax), after which momentum will slow down toward the end.

Tension is suspense or anticipation, and it is directly related to momentum. This is what keeps people turning pages because they want to know what happens.

I will put description aside for a second and delve a bit further into the relationship between tension and momentum.

Momentum = Tension + Pace

Again, momentum is not the same as pace. Momentum is the sense that the story is progressing toward something; tension is about intriguing your readers. You vary the tension based on the pace to get the right momentum.

You can have a slow-paced plot with such extreme tension that people simply can't put it down, because there is momentum; we feel something building up and we want to know what it is. This is common in horror stories. That creeping sense of dread is tension, and as it builds, so does the momentum.

On the other hand, you can have a fast-paced plot with 0% tension that no one gives a shit about. (Sorry Hurricane Wars, I DNFed after like five seconds because it was boring despite being super fast.)

In this case, you haven't gotten the right blend between pace and tension, which means there's not enough momentum. You've slammed me into a brick wall and I gave up. This is a common problem with adventure and thriller stories.

Tension is what makes people care, and it needs to be proportional to the momentum.

Think like you'll pulling something. You need strong tension to build momentum for a heavier (slower-paced) story. But you need light tension to build momentum for a lighter (faster-paced) story. And your pacing will vary, so you'll need different tensions throughout the book to maintain momentum.

And where does that tension come from? It comes from everywhere, but today we'll focus on description.

Description Builds Tension, Which Sets the Momentum

I don't think most people actually hate descriptions. Or maybe I am just too optimistic.

Readers (not Booktok girlies) hate descriptions that take away from the tension and are in the wrong places. These kinds of descriptions bring everything to a screeching halt because no one cares about them at that exact moment.

Description slows things down, which can be a good thing when you need tension. When you don't need tension - such as if you're in the middle of the fight scene - you need less description. You've built up the momentum already; now you let it hum along until it slows down again. Then, you pick it back up by introducing tension through dialogue, action, and description.

Here is a description I am particularly proud of. This scene happens in Absent All Light, the fifth book in The Eirenic Verses series.

Clearly these arrows are very, very important. I told you the fletching, what type of wood they are, that they have an iron tip.

They feel so important because there's not many other descriptions here. I am holding you by the face and making you look at them.

We're seeing this scene in slo-mo; you watch each arrow hit its mark. Now you're wondering what the fuck is so special about these arrows, of all arrows on the planet.

And you're probably also frustrated because our boy Orrinir passed tf out and can't even tell you anything more. What's with these things?! Where are they coming from?! Who cares so much about this stupid useless man?!

(Me. I do. Orrinir is baby.)

This unveils something else important, which is that you don't need to handhold your readers.

Allow Your Readers Some Autonomy

It's okay not to describe everything. In fact, it's better not to describe everything. Describe what is essential to what you are trying to show, and let everything else be a bit blurry. This helps maintain momentum: you're not bringing everything to a halt in order to take your reader on an MTV Cribs-style tour of a single room.

And, if the reader cottons on to the fact that you only describe things that are important, then they want to understand why you mentioned it. This creates tension ... and thus momentum.

Here's another example from the my WIP Funeral of Hopes, where we get to see a description of an outhouse. (Hell yeah!)

This description gives us a lot of context clues without going into disgusting detail:

It's nighttime.

We're obviously in a premodern world if there's an outhouse, and given the weird names, it's a fantasy premodern world.

Their outhouse does not smell particularly bad because of the ventillation. Our noses aren't being assaulted through the screen.

These characters have enough money to commission a nice outhouse. Probably not super rich, but not hurting financially either.

Their country has artisans, which suggests the place isn't raggedly destitute.

Orrinir is a simp.

Uileac hasn't gone to therapy about the fact that his parents were slaughtered pretty much right in front of him (because therapy does not exist yet). Instead, he avoids anything whatsoever that reminds him of his trauma, but it keeps coming up anyway.

We don't need to know the type of wood or the setup; it's an outhouse. Even if you, specifically, have not been in an outhouse, you likely have some cultural consciousness of what they look like. You can rely on that to fill in what wood it is, what the interior is, etc. Going too much into detail would be super annoying.

I could probably add a little bit more description - temperature, noises outside, if there's a breeze, if it's stuffy in there - without losing my readers, and maybe I will.

Of course, sometimes you just want to describe something pretty, and that's fine. But if you're describing something pretty, then it should have a reason for being there. Either it's a symbol of something, or it connects back to a particular theme, or it reminds the character of something else, or whatever.

Okay, so now we know what purpose description has, how to use it to build tension and maintain momentum, and so on. But what about exactly where to put it?

Where to Put Descriptions

Hellos.

When meeting a character for the first time, you will want to describe them. Face, height, size, eye color, hair color and style, maybe their clothing if it denotes something about them (rich, poor, messy, neat, weird, out of place, pretentious, humble, etc).

The more that your POV describes a character, the more crucial they are to the plot. Please do not describe every single side character because no one cares.

In fact, if the character isn't in more than a few scenes, don't even name them. Your reader's cognitive load increases with each character that you introduce and describe. I share more about that in my post about not overcomplicating fantasy stories.

The way that characters are described is also important, as I have discussed in remembering perspective when writing descriptions.

As characters grow closer, you can add new details as long as they would not clash with previous ones.

For example, the MC may notice a very small scar on the love interest's cheek after being together for a few days or weeks, which is an opportunity to share more about the love interest's backstory. The MC would not fail to mention an enormous scar that goes right across the love interest's cheek. That would, in fact, be one of the first things they noticed.

Goodbyes.

When characters part from one another is a good time to slow down and let the reader soak in the moment.

You can describe the setting as the other character walks away, or notice something about the departing character's gait - whatever.

Adding description makes their departure seem momentous and can denote how important the character is to the MC. Focusing on setting? Unimportant, maybe annoying, and the MC is glad to see them go away. Focusing on the character? Important, the MC probably likes them.

Travel Scenes.

This is a given, especially for fantasy adventures. Show us what's happening out there! If you can work themes into your descriptions by focusing on key elements - and having the characters react to those things - that's all the better.

We can get a lot of characterization by seeing how your MC observes their surroundings.

For example, if your character is a foreigner and has a bad opinion of wherever they are, then you can really draw out their disdain and help us understand them better.

If they are scared, they're going to look for things that feel safe and familiar - and panic if they don't see any. If they are excited about their journey, even the stupidest things will seem wondrous to them.

If they're naive, they may want someone to explain everything they see (hence annoying other characters and building conflict).

In this way, you're developing characterization, worldbuilding, infusing themes, and drawing a pretty picture, all at once. Multifunctional writing is always good.

"Approaching the Door" moments.

What I mean is those moments before something serious happens. It's the eve of a battle, or it's right before the character must make a huge decision that will change their life forever, or they're waiting for terrible news.

Think about sitting in the principal's office waiting for them to return so you can get yelled at. You're focusing on anything you can get your eyes on to distract yourself from what you know is coming.

Suddenly that stupid "#1 School Administrator" mug on the desk is the most important thing you've ever seen and you can't stop looking at it: analyzing its gloss, seeing the little dribble of coffee around the rim, noticing that the text is peeling. This can tell us how long the principal has been working in education, if they're a tidy person or a messy one, and maybe even how much they are liked by their peers.

If you've made it clear that something is going to happen soon, slowing down and describing (important!) things will feel agonizing to the reader. They will start clinging to every word for a clue about what is going down, trying to tell what the weather means, and so on.

Here's a brief example: we're waiting for Orrinir to give us the answer (and, hence, give his captors the answer). A lot hinges upon this answer, so I slow down to add some tension.

Not too slow, mind you. Again, it would be annoying if this went on for pages and pages. But now we have more tension again anyway, because we need to know whether the Sinans will figure out that Orrinir is lying.

By slowing down and giving a small flashback, it emphasizes how critical this question is to Orrinir's continued survival.

After Action.

These are the "cigarettes after sex" descriptions. Once something big and important has happened, we need to ease up so the reader can take a breather.

Too much action all at once is, paradoxically, very boring. You're vomiting all this action on the reader so they don't have time to digest what the hell is happening before you've dragged them on to the next point.

There's no tension, except maybe a tension headache because your reader is confused and disoriented. There's no momentum because everything is occurring right on top of itself.

As such, you break it up with a bit of description, pumping the brakes on the momentum. It's the difference between throwing someone off a cliff (horrifying, criminal offense) versus strapping them into a harness and rappeling down (exciting, recreational activity).

The descriptions may literally be after sex, like when the characters are admiring each other or the scenery after scaling a building to bang on the roof. Or they may be after a battle, during the cleanup or while the characters are convalescing. Or they may be after a huge important reveal, while the characters are digesting the news and trying to figure out what to do next.

Lulls

Again, you can't have 24/7 adventure and excitement or your reader will have a nervous breakdown. It's okay to have quick flashes of description during conversations, or while waiting for things.

To ensure you keep a good momentum, these descriptions should be pretty brief. It could just be your POV character noticing something sitting on the table, or hearing a noise outside, or taking a sip of tea.

These small descriptions can add a lot of depth without boring anyone.

Where Not to Put Descriptions

This isn't to say that there should be no descriptions at all in these places, but any and all descriptions should be kept very brief: no more than a sentence or two.

Fight scenes

Arguments

Chase scenes

Revelations

Explanations

Basically, anywhere that there is a lot of action in your particular genre, you need less description. You've got a lot of momentum now and can focus primarily on what's happening rather than where you are, assuming you set things up correctly.

So, now we get to the scariest question.

How Much Description Is Too Much?

Description is good. But like most things, description becomes bad when it is in the wrong place at the wrong time.

A quick rule of thumb is that if you have a full page of nothing but description - no dialogue, no action - you have too much. You don't have to remove it all: you just need to chunk it up by including an action or a conversation.

Your character should not be musing to themselves for a full page. I can't even listen to myself muse for a full page, and I am the main character in my own life. Throw a grenade at them, or have the building collapse, or whatever.

They also shouldn't be just describing things for a full page, even if it's some beautiful scenic locale. Have you ever tried to just sit there for 10 minutes and pick out every single little thing you see around you? Exhausting!

Real people would not do that, no matter how interesting somewhere is. They'd grab a snack, or turn to the person next to them and ask a question, or wonder what it would feel like to run into traffic, then promptly tell themselves not to do that and go back to admiring the scenery.

And man, if you are describing another character for a full half a page, your MC is either very horny or very, very bored.

You're probably sick of hearing this if you've been reading my blog, but this is a golden rule.

Characters are not real people, but for the most part, they must feel like real people.

Even the most fantastical of fantastic fantasy stories still have characters that feel like a real person, because people like stories that have realistic people in them.

Description is the same way if you are working in third person limited or first person. Think about how long you spend describing something when seeing it for the first time, or when you first meet someone. Probably not very long! You're not sitting there musing for ten minutes without doing anything whatsoever.

Together with dialogue and action, description builds a world, offers characterization, and creates tension: all the elements you need for a great story.

And speaking of great stories, do you want to read one? Of course you do. You should pick up my debut book, 9 Years Yearning.

This lovely novella is about two soldiers (the ones mentioned above, in fact) as they come to understand one another over their training at the War Academy. You can expect a lot of gay yearning, some fight scenes, and a bratty little sister who is simultaneously adorable and annoying.

If you do decide to read my book, don't forget to leave a review!

They're crucial for getting books on more eyes because Amazon loves reviews. And we wouldn't want to upset Amazon. (Please, Amazon is scary.)

#beginner writer#young writer#writer stuff#writing tips#writing advice#writing help#how to write#writing descriptions#writing reference#writing resource#writing resources#writing tip#creative writing#writerscommunity#writers of tumblr#aspiring writer#writers community#writeblr#writeblr community#writing community#wip excerpt

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

A writer's guide to describing passing out

Because i just passed out (again) and the second thing i thought of upon waking up was that glazed donut no mark save it for your art post, here is a list of what you could use when writing about characters passing out:

Beforehand:

you're going to feel really, really lightheaded. for me, that's what starts it all off. it's going to feel like when you stand up too fast, but it never goes away. your head doesn't clear

eventually, that lightheadedness feeds into a tv static sort of fuzziness. your head is whirring, almost. it's like a really drawn out buzz. you feel it in your forehead, in your jaw, in your ears.

your mouth starts to get thick, too. that tv static moves in there. your teeth start to feel fuzzy, especially the front and back ones.

by now, youre shaking and your limbs are heavy. at this point, i know to sit down, but it depends on your characters! is this regular enough of an occurance for them to know to sit? are they going to reach out to another character because they know what's going on? or are they going to reach out because they don't know what's going on? do their knees buckle and they fall while all alone?

it's all very disorienting at this point in the process. you have enough sense to form thoughts, but they're not all that coherent. words? not going to be that coherent either

During:

you can't pinpoint the exact moment you pass out. at least, i can't.

when you're passed out, there can be certain degrees to alertness. for example, i've had times where it feels like years pass but it's only a few seconds. i've had it feel almost like im in a really foggy dream. i've had times where i dont remember anything from it. most recently, i didn't remember passing out itself, but i remembered waking myself up from it. it was a very conscious struggle, where i knew i was passed out and i needed to wake up now

does your character remain somewhat alert? do they enter a dream-like haze? what's waiting for them there? i've seen faces and shapes there.

i personally can't feel when someone is touching me while i'm passed out, regardless of degree of alertness

do they know that being passed out is Just Not Right? do they wake themselves up?

Afterward:

you pee. that's just the deal. your bladder is going to release. i know this is not romantic, but like man thats just what happens.

peeing, like most things, could hold a plot point. who cleans your character up? or if they're on their own, how do they clean themselves up?

youre also drenched in sweat. just absolutely sopping in sweat. passing out loves the release of excess body fluids. its sexy like that

mention sweat on their neck, their forehead, their hair pressed down by it. do they wipe it off? do they have the strength to? if they don't, does someone else?

your face will have no color. describe this, but don't stop at the face. your character's lips will also be drained of it.

you will be wobbly. standing up, even sitting up, is going to involve a lot of shaking.

when you first talk, it won't be loud (fuzzy tongue, remember?) so it takes a couple tries to get what you want to say out. or if you do get it out right away, it surfaces extremely weak

it's important after you pass out to get fluids in you. not just water, but orange juice, cocoa, anything that will get you awake again. who gives this to your character? if there are multiple characters present when your character passes out, who won't leave their side and who runs to get something for them to drink, knowing it will help them?

your hands will shake lifting anything

it takes 3-5 minutes for me to regain color again

it takes about 5-10 minutes for me to feel normal again, but this likely depends on the person and how often passing out occurs for them

Please keep in mind this is based soley on my own experiences! also please feel free to add on! i hope this helps!

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

brown eyes - comparative descriptors

Eyes like . . . / Eyes the shade/color of . . . / Eyes reminiscent of . . . / Eyes that embody . . .

coffee beans

tamarind

milk chocolate

cinnamon sticks

wren feathers

peeled chestnuts

potting soil

maple syrup

molasses

#writing#writing ref#writing descriptions#writing help#writing tips#eye colors#brown eyes#eye description#writing eye color

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

PROMPT/IDEA- Enjoy!

Lightning, jagged and harsh, quick as a sword, faster than blinking slashed into the sky like a cat’s slashed claw marks against the dusk. “Captain!” He exclaimed, spluttered as he slammed into the ship’s railing as waves crashed over the sides.

“Full steam ahead! I won’t lose another chase, I shan’t! Full steam ahead!” Thunder cracked overhead. The navigator clutched his chest, wheezing and coughing still.

“We can’t, sir, the storm’s too much! We’ll never make it!”

“We’ll make it if I say we’ll make it!” The captain hollered back, battling the howling wind to be heard. “How dare you question me!?”

“Please, Captain! I beseech you, see reason-”

“Enough! One more word from you and I’ll have you lashed! Full steam ahead! Don’t let them get away!”

#story prompt#writing prompt#creative writing#story ideas#short prompt#writing inspiration#writers block#writing#writing prompts#creative writing prompt#pirates#pirate story#writing descriptions#pathetic fallacy

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

how do you approach writing description?

oh man... there's not really an approach 😅 it's more like me circling around it and throwing lassos around phrases and key words i wanna use while the image in my head tosses its beastly head around and dances out of reach 🤣

there are some key strategies and techniques i try to use though!

describing people: vibes, expression, colors. if i tell you "she had large brown eyes and short blonde hair" you get a quick glimpse of her, ig. if i tell you "she smiled widely, all dimples, her hair falling over her shoulders in golden coils as she tilted her head" you can see her much more clearly AND you know something about her. pair physical discriptions with hints of personality, it works way better!

describing scenery: be like the poets. make things like other things! the street is a river of black water. the house is the color of sand with shutters like mist and you can almost almost hear the fog horn as you look at it. the sun scorches your back as you trudge through the sand dunes, coated in white fire. people will be like "ooh that's so good you're so good at describing stuff" and you'll be like "hahah yeah"

describing feelings: i'm a very visceral person so when i feel emotions i really feel them in my body. when trying to put myself in my characters' shoes i imagine what their body will feel like when they're experiencing those feelings. i stick to corporeal stuff like "aching lungs" and "soaring heart" and "stinging eyes." so, less descriptions like "his pained expression broke her heart" and more like "the downturn of his mouth sliced like a knife through her ribs."

sometimes if a scene is really intense i don't describe feelings. it becomes an out-of-body experience where the character kinda dissociates. "her blood painted the ground where she lay, staining the pavement, the sky, and the taste in his mouth."

so yeah just a bit of a peek into how my writing process goes 🤣 it's definitely never this smooth when i'm ACTUALLY writing, usually i have to go back and add in descriptions where they might be missing from the scenes. hopefully this helps whoever comes across it! and you too, anon, if you were looking for advice lol.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

It wasn't until high school that I began seeing the world as a story to be written. It was a survival tactic, I think, for covid. That and a general habit created by my near-constant writing.

To that extent, it wasn't until post-lockdown that I realized how fucking cool fog is. And since it's foggy today, I'm going to talk about it.

I think that fog is only cool as a visual medium. Book descriptions don't do it justice. "A bank of fog rolls in" "tendrils of fog reach through the trees" yeah but what does that LOOK like?

It looks like a digital artist was drawing clouds behind a mountain and misplaced a layer. It looks like a cloud bisecting the landscape. The tops of the trees look like an island rising out of a flat calm, gray sea while the bottom half of it, the bushes and the houses and the roads, looks like an unfinished painting. If two people were to stand down the road and hold a flashlight, it would be a damn good impression of a car.

And I think a lot of authors forget to describe how fucking damp everything is. There's always this impending sense of rain. Nothing is dry except maybe your clothes, and odds are they're not gonna stay dry for long. Your socks and shoes are toast the moment you stray from a paved road. Hope you like wet socks.

Fog doesn't work like the poison mist in the hunger games. You don't walk into a wall of fog unless some outside force has confined the fog to a specific area. It's a gradual claustrophobia, a slow loss of sight.

It's also usually still when the fog is thick. Otherwise, the wind would blow it away, right? But unless a monsoon is following the fog, there's not quite that eerie "calm before the storm" stillness. It has a different vibe to it.

But you can't say all that without interrupting the flow of the story, so people tend to stick to the simpler descriptions.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is writing so hard?

Any tips on writing block? I've got story/character associated music, I'm not focusing on it being perfect, I'm allowing mini time skips where I can fill those scenes in later.

Help lol

Also, how does one find the balance between dialogue and description?

#anti endo#endos do not touch this post#quills corner#writing#writers on tumblr#original story#short story#writerscommunity#writers block#writing dialogue#writing descriptions

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! So I’m a fairly new ambulatory wheelchair user with EDS writing about a character who is also an ambulatory wheelchair user. I feel like I keep using the same words over and over to portray movement though (rolled, propelled, “pushed themself,” etc) so I would love to hear if you have any more ideas for alternatives! I’ll take as many as you’ve got!

Thank you!!!

Hello dearest asker!

This is the list that we have provided over time plus others:

Moved/Moves

Went

Wheeled

Rolled

Pushed

Sped/Spun

Propelled

Pulled (by a service animal etc)

Maneuvered

Turn/Turned

Scoot/scooted

Travel/traveled

Rock/rocked

Drove

Crossed

Cut

Stroll/Strolled

Navigated

Drift/Drifted

Swung/swinged

Popped ("Popped up their wheels/chair" to get over a surface etc)

Tip/tipped (Tipped themselves over something etc)

Advanced

Migrate/migrated

Inched

Zoomed

Rushed

Hurried

Raced

Skid

Ram/Rammed

Roamed

Shift/Shifted

Slid (In rainy or icy weather)

Followed

Circled

And a lot of many other verbs that would take me a long time to list! Consider what type of wheelchair the person has, as mention Here. And also how the person moves or places their hands can be another detail to include.

If the actual definition of the verb doesn't involve the specific actions of one or two lower extremities (ex. walk, run, stepped, trot, stride) then it's otherwise good to use! Other words like Moseyed, sauntered, paced, I think depends on the writer. A particularly mischievous character may saunter of a manner in their wheelchair. And a character who is nervous would pace—although possibly tiring—back and forth. And Moseyed, well, I just particularly like this word—but, a character could mosey on by in a certain fashion. Happy writing!

(last ask about verb terminology on wheelchairs per this post we made about it)

~ Mod Virus 🌸

311 notes

·

View notes