#would that i is not about the knights comradeship?

Text

so it’s actually impossible Florence and the Machine, Daughter, Taylor Swift, Phoebe Bridgers and Hozier didn’t watch Merlin and then release their music because otherwise there is literally no explanation

#merlin bbc#bbc merlin#you’re telling me Moon Song is not about Arthur’s death#my tears ricochet is not arthur and morgana#youth is not about morgana?#no light no light is not about morgana arthur and merlin?#would that i is not about the knights comradeship?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Toei wanted to make their own ver. of Silver Surfer in the early 80′s (Get ready because it’s about to get wild)

All the information I’ve gotten is in this one blog here, documenting about what Toei and Marvel were collabing on at the time: https://spider-man.at.webry.info/200802/article_3.html

From the blog in the link above:

‘As mentioned in this blog several times before, after Spider-Man aired from 1978 to 1979, Toei planned and considered several programs using Marvel characters, including 3-D Man, Moon Knight and Silver Surfer.

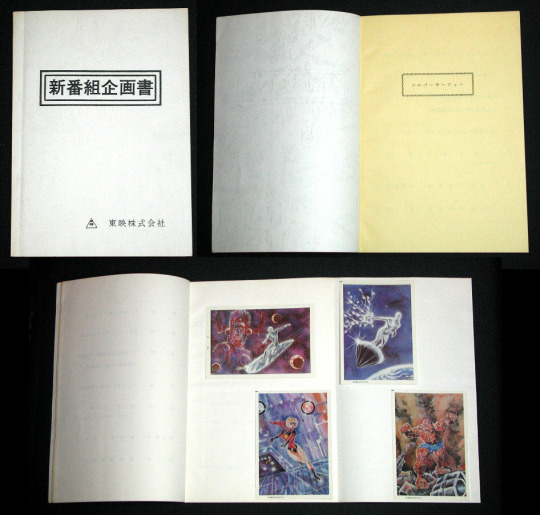

We introduced 3-D Man (26 May 2007) and Moon Knight (14 January 2008), but Silver Surfer had not yet been introduced, so we thought we would introduce it sooner or later, but the other day we happened to receive a copy of the "New Programme Proposal" that resulted in Silver Surfer's death. I was planning to introduce it sooner or later, but I happened to get a copy of the Silver Surfer's lost 'New Programme Proposal' the other day, so I'll write about it this time, weaving in its contents as I go along.

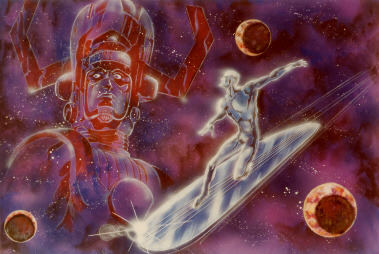

This is the Silver Surfer proposal. Four colour photos of the main characters are attached.

The show is a colourful and varied action series centered on three Marvel Comics heroes - Silver Surfer, Ms Marvel and The Thing - and features Marvel characters from time to time, plus original characters from Japan.

Title: Silver Surfer

Type: SF hero action film

Format: TV film with extensive use of VTR synthesis, 30-minute complete episodes, 26 or more episodes.

Target audience: Young people and other families in general.

Based on the novel by Saburo Hate (from the Marvel Comics version)

Planning cooperation: Kikakusha 104

Production: Toei Co.

Planning details

The Great Invasion Army, led by the space emperor Galactus, extends its power across the universe. Their next target is our home planet, Earth. At ・・・・・, Ms Marvel and The Thing, who belong to the Japan Branch of the Independent Strategy Office, have a fateful encounter with the superhero Silver Surfer, who has escaped from Galactus' army to Earth, and are told by him of the enemy's true intentions. The three are united by a strong sense of comradeship and rivalry as they face their giant enemy.

Introduction of the characters

Silver Surfer (Koushi Shibuki).

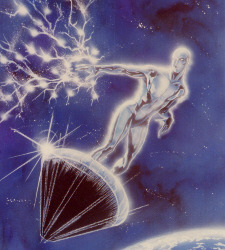

A silver-coloured alien who pilots a surfboard named Skyboard and travels through space at the speed of light.

He was a resident of the planet Zen Ra, but was captured when an invasion force destroyed the planet and converted into a space combat soldier in the psychic strategic development section. After being converted, he attempted to escape to his late mother's planet.

Fights enemies with Cosmic Power, an ability that allows him to manipulate cosmic energy.

Cosmic Blast = Attacks by firing energy blasts from the fingertips.

Cosmic Burst = Energy discharge generated from both hands spread wide.

Cosmic Attack = The strongest attack method, in which the energy stored in the body is released, the entire body is enveloped in energy and the attacker strikes with the body. However, this technique drains all of Silver Surfer's energy and can only be used once in battle, as he has no attack ability for "one hour" until the Cosmic Energy is charged up in his body again.

Usually a young man who enjoys ocean sports, mainly surfing. When he catches sight of an enemy invasion, he heads for the battlefield as a warrior Silver Surfer. His father is from the planet Zen Ra and his mother is from Earth.

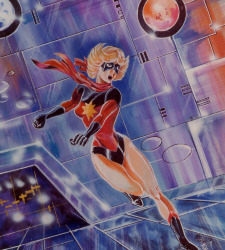

Miz Marvel (Masumi Suzuka).

An Earth superheroine with inherently superior precognition and clairvoyant abilities. In everyday life, she is a female university student who works part-time at a coffee shop frequented by Koushi Shibuki. She is actually the daughter of the wealthy Suzuka family.

Thing (Gen Ishihara).

A power fighter who punches with great destructive power, defeats his enemies with great monstrous strength, and is an earthling who specialises in ground combat. He is usually a truck driver. He often frequents the coffee shop where Suzuka Masumi works part-time.

During the investigation of a previous case, he was involved in an explosion at an enemy hideout, at which time he was exposed to special energy along with a monstrous beam of light, and became a superhuman with immeasurable power.

That's roughly how it went down. The rest of the book contains information about the 'Independent Strategy Office of the Earth Defence Organisation' to which the three belong, an introduction to the 'Galactus Army', a sample story of the first episode, and so on. We will introduce this proposal when we have a chance.

-----------------------------------

By the way, I looked into this lost project to see if it was utilized in any later Toei special effects programs, and found some matching settings in Space Detective Gavan, which was broadcast from March 1982.

The Gavan project started in the spring of 1981, around the same time as Silver Surfer.

The story is about the defense of peace in space, which is a different dimension from existing heroes.

He wears a silver combat suit.

He emits rays of light from his fingertips.

His father is an alien and his mother is from Earth.

He rides in a sidecar (Cyberian), reminiscent of the Silver Surfer.

[Image reference.]

There may be more, but I don't think I'm the only one who feels that this is similar. However, I haven't seen any reference book that states the fact that the 'Silver Surfer' setting was used for 'Gavan', so this is a matter of speculation.’

------------------------------------- End of Translation

So that was my find of this info. All while I’m trying to find info of ‘Tomb of Dracula’ anime animated by Toei so I tried to find info on Google using Dracula’s Japanese title and lo and behold, I found this blog that has quite the info on it.

Next time, info on ‘Tomb of Dracula’ anime movie and how Harmony Gold crammed WAAAY Too much story into a condensed movie that was different in the intended way by Toei.

#toei tokusatsu#toei#Marvel Comics#marvel#silver surfer#jack kirby#1980s#80s#superheroes#tokusatsu#Toei and Marvel Collab#40th anniversary Metal Heroes#Metal Heroes#space sheriff gavan#Metal Heroes 40th#comic book heroes#comic books

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

I soon found out that Sanson and Guydelot were not the happiest of duos, in fact they spent more time arguing over tiny things.

It was refreshing, they were both full of passion, Sanson for his job and Guydelot for life.

When we rescued Slyviel, he was more than grateful to tell us of a Coherthan Legend, He told us of a Saint of Song that lived in the heavens, a master of poetry and verse, who was said to bring battle to an end with its song. While Sylviel went to look into it further, Guydelot proclaimed how fruitless he thought the current enquiry was. A 'dead-end' and on his recommendation they should return back to Gridania.

I think it far too early to draw conclusions. I, for one, mean to continue searching until I find a definite answer. If you wish to abandon our mission, I'll not stop you.

But know that you would be judged a deserter. You would lose your place in the Gods' Quiver...and that would be precisely what your superiors had intended.

Look, Guydelot. You of all people must know the true reason they chose you for this mission. They wanted you out of the way! Your skills had naught to do with it!

And it isn't so different for me! I was a thorn in their side, demanding cooperation when they were loath to give it! They were pleased to be rid of me as well, yet naught would please them more than for us to come back empty-handed!

That is why we must succeed! That is why we must find the Ballad of Oblivion!

If you want to find the song so badly, you can bloody well find it yourself. I've had a gutful.

You're no bard─I doubt you even understand what gives a song its power. Yet here you are gallivanting about searching for one.

To you, the Ballad of Oblivion is just a means to curry favor with the brass hats. Well, that's an insult to honest-to-gods bards like me and Jefara.

Oh, gods, what have I done? I did not mean to be antagonizing...

Though my pride won't let me tell him this, I know that Guydelot is a truly exceptional bard. With his skills married to my unit composition, I had hoped that we might prove our detractors wrong. Alas, my words failed to convey that intent.

With him gone I stayed with Sanson, he showed me his notes from their journey, from Celaine a Convictor Knight they had meet not the week before. She had shown them not oblivion but how she savoured the time she had with her comrades, sending them to heaven when their time came. She had encouraged them to savour their comradeship, a task Sanson felt he had already failed in.

In turn I shared some of my own experiences, of my loss and how I wish I could have embraced my companions more. I dont know when it happened but before long we were starting to write, to compose...

Our own song. A dangerous hope that we wished to share.

#Final Fantasy XIV#FFXIV#warrior of light#ffxiv aura#HW#ffxiv hw#ffxiv hw retelling#ffxiv gpose#final fantasy gpose#FFXIV Screenshots#ffxiv screenies#sanson#guydelot#bard

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

for a long time my Republic main was my Commando, Zekket (started life as a Twi'lek but always headcanon Togruta, naturally made the switch once available) who I've recently started to imagine connecting with Rusk post-KOTFE

He's not my story's Outlander - despite Vyzzir (SI) being my main, he's more on a fun journey to explore Dark Side options, his story in my canon has him staying on the Dark Council under Vowrawn - my Outlander is Jelrin Eis, a mostly-LS Consular - but I still imagine the Jedi Knight team becoming fractured in the Zakuulan war, so Rusk would be operating in his thing you find him in the Alliance alerts

Zekket, for the record, was in love with Jaxo. I enjoyed her as a love interest and wholeheartedly wove her into his story as his personal canon; he started as an honest-to-Force lightsider, idolized the Jedi commitment to peace and nonaggression wherever possible (he has a cousin who he looked up to who was very much a chivalry/bushido/honorable Jedi who died in the Battle of Corellia), always did the Right Thing even to the point of pissing off Garza, I think he spared every former Havoc member you could

Until the Thing with Jaxo happened

I remember literally having my heart pounding realizing what was about to happen, putting off the choice with as many dialogue choices as possible til I got the one where Jorgan was like "we're all soldiers. she knew the risks. there's only one right choice here" and he, of course, saved the prisoners.

This was unexpected to the way I'd imagined/played him, but the curveball honestly made gameplay so much more interesting....because that absolutely broke him.

I actually sent him to Tython and had him just hang out there for a while (in my story it was several months), when I played him I mostly did crafting/GTN stuff rather than any missions, because he was so wracked by what he'd had to do, and he was fighting hard to find the same clarity and compassion he'd always idolized....

....but he didn't.

He then flipped entirely. He didn't go like full-selfish-cruel dark side, but he never spared another Imperial or Sith. Ever. Not even surrender/prisoners/civilians. Took every weapon, took every harsher choice he could. He was still a diehard Republic soldier, and believed he was doing the right thing, but his rage and spite for the Empire honestly took over a lot of his decision-making

He also, not suprisingly, started ignoring a lot of command orders that tried to temper any recklessness; the same command that got Jaxo killed wasn't someone he trusted anymore, making him much more of a loose cannon

In my "endgame" stories for the fate of all my characters post-whatever-SWTOR-comes-up-with, he leads the strike team on Vyzzir's stronghold, and personally is the one who kills Crythos, Vette (my headcanon Vette romanced my darkside SW and had a kind of thrill-of-the-battle Bonnie and Clyde dynamic), and ultimately, Xalek

(Xalek's death is what made Vyzzir surrender; for all his lawful-evil Sithness, he'd never gotten over losing his brother as a child, and Xalek had very much replaced that empty hole in his life; despite having his relationship with another Twi'lek slave on Balmorra (hence Crythos's birth) I have written Vyzzir mostly as aroace, with his most important relationship being his comradeship with Xalek. If it had happened maybe 20 years prior, Xalek's death would have fueled a formidable rage that would have probably turned the tide of the whole battle, but with the crumbling of the Empire and his advanced age, losing his son, most apprentices, and then the most important being in his life all in the span of a single day was too much)

Vyzzir was fine with Zekket being ready to execute him despite surrendering - he pretty much expected nothing less - and was only spared because Utuli (ironically, Vyzzir's brother who grew up as my canon Consular, at least for the main story) was there. He'd assumed Utuli died when they were children, Utuli was the one who figured it out that they'd both lived; his main virtue in the way I play all his choices is mercy, so it made sense for him to prevent Zekket from executing him despite being a Dark Council member, though there was certainly a struggle with Jedi-detachment in him when realizing it was his brother

ANYWAY back to Zekket, he and Rusk obviously align on a lot of things in the way they approach their duties as Republic troopers. I could see them teaming up; I'm not sure about romance between them but honestly I haven't ruled it out. The idea of them finding someone who Gets It; of them first fueling off each other's bloodlust, but slowly starting to recognize how it was eating them away by seeing it in each other (seeing someone they care about consumed by anger and guilt and violence and realizing that they're hurting themselves and other people, then in turn realizing "wait I'm doing the same thing") and finding some form of healing in that relationship is something I find intriguing

Anyway I don't often post so much of my SWTOR story but here's a peek into it

#swtor#republic trooper#sith inquisitor#star wars#my fanfic I guess#zekket#vyzzir#utuli#rusk#xalek#crythos#vette

0 notes

Text

i wonder if the knights would initially be relatively cold & angry, protective even, if they met rey —— considering how much of a threat she poses on a regular basis to the livelihood of their master, i doubt they’d immediately be welcoming. she’s almost killed their boss twice. there’s the whole potential for animosity there.

i need this dynamic solely for the moment of ben’s deadpan dismissive ‘ no, it was a consented almost-death ’ followed swiftly by one of the knights moving right along with a ‘ oh, in that case can i sit with her then??? she’s rad. ’

i want oddly bloomed friendships, weird comradeship made between force-sensitives aligned to the opposing sides of a war, but ultimately both caring about the same person enough to put those differences aside. i want disagreements, i want rey going feral defensively because a knight tried to get a rise out of her, i want ben to have to put his foot down & make them listen to him. i want certain knights accepting her & others being harder to convince, but ultimately stowing their weapons because kylo ren declared her ‘ not an enemy of ours ’ & to directly disobey him would be to earn not only rey’s blade, but his as well.

#UNMASKED. // & out of character.#i won't sit here and pretend that the kor and rey would be buddies right off the bat.#there's tension. there's loyalty and duty and protectiveness from the knights#who wouldn't likely enjoy the idea of a resistance-aligned jedi who almost killed their leader whom they're bonded with#to come strolling in.#but -- that's why i need. kor + rey interactions to really nail the drama of that.#because of course ben's not about to exclude his dyad from a vital part of his process of leadership.#if rey ever joined his side / etc. it'd be a necessary hurdle to introduce them to each other.#and if we're talking about a post-tros scenario; even more so important for them to coexist.#these people are all that ben has left.#rey and the kor.#jj can pry this from my cold dead hands but: ben wouldn't just mow the kor down to choose rey. he'd ( and i know this concept is INSANE )#want to keep his found-family / friends just like rey with her resistance buddies.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

sorry for the strange question but erwin and levi’s relationship is one of friendship/comradeship canonically as far as was confirmed?

Isayama has described their relationship like that of a knight and liege. But I do feel that terms like friendship and comradeship would absolutely apply to their dynamic, yes. I believe their bond is something that WIT’s PR team especially wanted to highlight with the second half of season three, and its importance to Levi’s character. But Isayama has talked about it quite extensively here and here.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hero’s Road

Warning: Definitely has spoilers up to Volume 6, Episode 4

Rating: K

Word Count: 3.5k

Ao3 Link: The Hero’s Road

Summary: Though every reincarnation was new, their role was always the same. This time around, Ozpin was set to be the guide, Oscar the driving force and, as always, Ozma was the spirit.

Things just… weren’t exactly going as planned right now. [Set sometime after Volume 6, Episode 4]

Notes: So this is completely dedicated to @undeadwicchan who’s post here inspired me to do a character study on the three Oz’s (Ozma, Oscar and Ozpin). Beyond briefly utilizing the idea of Ozma coming to the rescue for Oscar, it doesn’t actually have much to do with the framework of the post itself - which, all the kudos to you for such a kickass headcanon; it would be seriously awesome to see executed in true canon. Nevertheless, with this volume making me all sorts of fond for the precious trio, this was just the jolt I needed to get writing something of my own!

~

It had been a long time since Ozma had been required to surface to the full forefront of control.

But Oscar, young and inexperienced as he was, could not handle the swarm that overtook Brunswick Farms. Roused by the cries for help, he swiftly took the reigns and joined the fight alongside team RWBY and Qrow. Yet, hindered without Ozpin’s melee experience, he relied entirely on his magic to combat the force – tipping them all off that he was neither of the two they had come to expect to see.

As soon as the last Grimm faded, they turned on him, as he expected they would.

“What are you doing here?” Sir Branwen’s voice was as sharp as his weapon. Unlike his kin, fear did not shake him; he stood taller in the face of adversary. Were the man a true bird, one might believe such a valiant personality would go up against even an eagle. It was a quality that was hard not to admire.

But when faced with it in opposition, even dug deep in their mind as he was, he could feel the pang from Ozpin’s heart. He fathomed that no matter how many times he was reborn, there would always be those select few that their desertion would strike hard enough to unbalance them. It was just unfortunate that those around them often forgot the fact they were still entirely human themselves.

“Do you know how many lifetimes I have led?” Ozma questioned. He turned to face them, their combined ire doing nothing to weigh him. “Ninety-three. The ninety first and second were the closest we’ve ever gotten to unifying humanity. A hundred years to end a war and bring about comradeship among our kingdoms. To create technology and advancements the world had never seen before. To build the schools and raise a defense force for the many less-abled.” He stepped forward, his voice rising with his righteous fury, “And one night was all it took to see so much of that undone. One night for irreparable damage to be done.” He looked to Lady Xiao Long as he said this, watching as her gaze averted. He turned to Lady Belladonna and Lady Schnee next, “For fear and uncertainty to halt us.” Finally, to Lady Rose and Sir Branwen, “Or for those to be lost that could never be returned.”

The snow crunched underfoot as Qrow challenged him, “That’s not-”

“One mere hour for you all to lose your confidence.” He swept his cane in indication of them, stalling it to point to the man. When only silence reigned, Ozma placed it down, crossing his hands over the top. “I am not naïve to what the power of destruction can do. It is in it that has my former love so lost.” He shut his eyes, briefly seeking the one locked away; but Ozpin still was not ready to give up the key. “It is in that, I find myself lost as well.”

“Then how can you ask us to fight an enemy we can’t beat?!” Yang snapped, her fire refueled. Another quality that was easy to admire, but when misdirected, became her greatest obstacle.

“Then I will not.” He replied simply. “I instead ask you to fight for what is right. Every moment we delay is a chance for Salem to continue her advance. Atlas and Shade are no doubt her next targets. Every life we can save by merely intervening is worth it. However, whether you stand by me for that end or not is only a choice you can make.” He walked past them, heading back for the farmhouse they had come to make their own.

“Where are you going?” Asked Lady Schnee.

“To lie down. I used a tad too much magic. Oscar will need time to recover.” He paused, glancing over his shoulder. “And he, like all of you, needs time to consider what he truly wishes to do.” He continued onward.

What I wish to do? Oscar repeated faintly.

Did you truly not believe you had a choice? He thought back.

Silence was his only answer.

Ozma quickened his step just so. It seems he had more work to do.

~

When Oscar awoke, he was neither on the couch he had laid down on nor in the farmhouse at all. Above him were the branches of trees, sunlight streaming through and dappling along the ground, confusing him with their lack of snow and cold. As he sat up, it was with a start he realized he was not alone.

Ozma sat on the ground a few feet from him. He may have been meditating but at the sound of movement, his eyes opened. “Ah, it was much easier to call you here than I feared.”

“What’s going on? Where are we?” Oscar demanded. Things were already weird enough in his head; if he found out he had some crazy super ability to astral project, he was done.

“Calm, young one.” Ozma replied, raising a hand. “You are still asleep. This is merely a mental space in which we can talk. As for where we are…” He looked about. “You’ll have to tell me. It is your psyche after all.”

He looked around, realizing the other man was right. He did know this place. “It’s one of the forest trails that leads back to my farm.” It was the same one he’d taken to leave.

There was a rattle of armor as the other stood. “Then perhaps we can take a walk together. I’d enjoy to see it.”

Yeah right. Still, Oscar allowed himself to be helped up, doing his best to keep up with him as they walked down the dirt path. As they did, he could not help but sneak glances at the man. He truly appeared as if he were someone who stepped right out of a fairytale, with armor meant for a knight and a cape befitting a superhero. Even his body language seemed strong, with his shoulders and head high, his stride long so that it forced Oscar to take two steps to his every one. How could he walk with such confidence when everything in his life had gone so wrong?

Ozma caught him staring and smiled at him. “Are you alright?”

“Y-Yea!” Oscar looked down, his face heating. “What did you want to talk to me about?”

“Whatever you would like. I’m sure you have a lot on your mind.”

He thought of asking the one he’d just thought, but quickly shook it aside. He went for something safer instead. “Why do you want to see my dingy old farm? I’m sure it’s nothing nearly as amazing as the stuff you’ve seen.”

Ozma chuckled. “You know, I always loved adventuring. It was what made me decide to set off from home. I wanted to see the world. Experience everything to its fullest.” He waved his hands outwards, encapsulating a sight Oscar could not see. “My travels brought me to so many places. Grand castles. Beautiful canyons. Stunning oceans. And yes, even ‘dingy’ old farms.”

“And you left, as easy as that.” He shook his head. Figures.

“I never said it was easy. My father was furious. Every night he told me I was throwing my life away. And my mother cried and cried.” Ozma looked away and though his smile stayed, there was something sorrowful there. “I don’t think I could have ever disappointed them more.”

Like a Grimm to a mourner, he couldn’t help but wonder what his own parents would have said, had they still been around. He felt something settle against his gut uncomfortably. A weight he hadn’t felt in years, but its presence was as agonizing as ever. He ran a hand over his face, trying to act like he was brushing away an itch and not the burn in his eyes. “So why did you do it?”

“It was all I wanted. I didn’t want to live with the regret I hadn’t tried.” Ozma placed his hand over his heart. “It just felt right.”

His feet stopped, the sentence striking a painfully familiar chord in him and words spilled out before Oscar could help it, “Is that why I felt that way when I left? Was it you!?” So many emotions were filling him he didn’t know where one began and another ended, but anger seemed to take the helm, raising in a great tidal wave inside of him. “Huh?! Was it?! How many other things haven’t been me?! What else is just you or him or, or someone else!!”

Ozma reached for him, “Oscar-”

“No!” He smacked the hand away, stumbling backwards. “When I was younger, I used to dream about it, you know? Setting out on my own big adventure. Becoming a hero like the ones we saw on TV. I thought that was what I wanted.” He looked away, his fists so tight at his side they shook. “But now I get it. I never had it in me to leave. It’s… it’s always just been you, hasn’t it? And that’s what it’s going to be like, isn’t it?!” He bowed his head, fighting down tears but not the other’s approach this time, or the hands that laid on his shoulders. He let his head thunk against the metal breastplate. “I didn’t even get a choice! It’s not fair!” Metal rang as he slammed his fist against the other’s chest. “It’s not fair!!”

The arms that encircled him tightened. “Yeah, you’re right. It’s not.”

He hit him again, strength waning. By the third strike it was barely more than a weak knock. He slumped against him. “I’m just going to disappear, aren’t I?”

“Of course not.” Ozma’s voice was soft, almost fatherly in a way he’d almost forgotten, as he spoke against his hair. “If Ozpin nor I have disappeared, why would you?”

Oscar snuffled, tilting his head up, “But Qrow, he said…”

“An injured heart will say much in an effort to ease its own pain.” He stepped back, just enough to look at him properly. “I will not lie and say that the lines do not blur at times, but there will always be a distinctive you in here and your input is always as important as ours. And you will always have the right to choose.”

“What about at Haven?” He bit back.

Ozma laughed softly. “The same can be said about Jinn.”

His eyes widened. “I- That was- I was just-”

There was a shake of his head and a hand on his shoulder once more as the man lent down to his eye-level. “I apologize, it was not an accusation. Merely an observation. None of us have been very fair to each other. But while the past can’t be undone, we can change moving forward. If this coexistence is to work, that is.”

“So what if I said I wanted to go back home?” He challenged.

He expected him to blanch or backtrack. But Ozma only smiled and said, “Then I’ll help you buy the train ticket this time.” The hand on his shoulder squeezed; a reassuring touch. “Is that what you want?”

Oscar looked away, wiping away tears. “No. I dunno. Maybe.”

He rose. “What is it that makes you uncertain?”

A sigh heaved from deep in his chest, focusing on the dirt between their shoes. “I’m… not like you guys. I’m no knight running out to save damsels from towers. Or some wise professor who can motivate a whole school of people to be these great fighters.” He laughed bitterly as he threw up his hands. “I couldn’t even get that guy to shut off those stupid turrets! I’m not particularly smart or skilled,” Finally, he looked up at other. “Or brave.”

An eyebrow rose like a startled exclamation. “Are those the things that you believe a hero to be?”

“Of course they are!” When Ozma’s expression did not change though, Oscar felt uncertain suddenly. “…Aren’t they?”

He hummed thoughtfully as he waved to the trail before them. As Oscar took his place beside him again, he was given his answer, “They are good qualities, certainly. But one can be skilled, yet never use them to assist others. One can be smart, but remain uncaring to other’s plights. One can be brave, but recklessly so.”

“So then, what does make a hero?” He asked.

Ozma’s eyes glittered merrily. “What is it about Lady Rose that impresses you so?”

Ruby? “Well she’s… amazing.” He thought back on the train, how easily she got Dudley to listen to her when he couldn’t. How she commanded her team to focus. How even now her words to him back at the house at Haven still inspired him. “She can motivate others.”

“What do you think it is about her that gives her that ability?”

As he tried to think it over, he found he couldn’t pin down something tangible. It just seemed to be something that was inherently there. A piece of her that made people want to stand beside her. Something in the way she viewed the world, with such a bright and kind spirit, that made others want to do the same.

… Oh. “Her heart.” He said finally.

“Yes.” Ozma nodded. “A good, strong heart is first thing a true hero needs.”

Oscar placed a hand over his own. Did he have that?

“If I may be bold,” He added, tone amused. “I do think it is also worth saying that I do not often witness fourteen-year-olds rushing across the top of speeding trains. I believe what you lack is not any of the things you think you do, but merely your own self-belief.”

“What do you mean?”

“To have faith in others, first you must find it in yourself. Though, I will admit, in the face of failure, it can be one of the hardest things to hold onto.” As they reached towards the end of the trail, the world grew dark and grey as storm clouds hovered overhead, blocking out the sun. Ozma’s expression seemed to do the same as looked into the distance. “No matter how strong they are.”

Oscar stared as well, discovering that they had not entered the plains that would lead to the farm, but a courtyard leading to a school he had never seen in person, but recognized as if it were his own home. “Beacon.”

“How curious. I did say before this was your psyche we were traveling in. So why do you think it brought us here?” Ozma quipped.

He gazed upwards slowly, to the office he had once been able to mentally photograph perfectly, and knew exactly who was hiding within it.

Oscar squared his shoulders and held his head high just like his companion. “I think it’s telling me it’s my turn to rescue someone from a tower.”

He walked forward.

~

A quiet, familiar ding roused Ozpin from his stupor. He lifted his head from his arms, finding it as heavy as the rest of him felt. He could hear the gears around him turning, and realized where he was. Asleep in his office again? Then no doubt it was Glynda coming to chastise him. He reached for his glasses, slipping them on to at least appear more presentable – and with it his hazy vision cleared, startling him when instead of his dear assistant, it was two familiar gentlemen approaching.

Right.

He was dead.

(How was Glynda doing? And… how long would it be until the truth got to her? What would she think of him then?)

“Ah, time for The Walk?” Ozpin asked, willing himself not to sink back to sleep.

“Wait. This is a thing?” Oscar asked.

Though he couldn’t muster a laugh, he could not help but be lightened by the boy’s simple innocence. He was going to go on to be a great reincarnation.

“It’s a practice I sometimes perform once my new host learns the full truth. I find it helps to uplift the spirit.” Ozma replies. “Though, it’s usually not this soon.”

Oscar turned to him. “I learned sooner than you?”

Ozpin crossed his hands, smiling to the boy. “Four years, to be exact. I was also twice your age.” He focused on one of the larger cogs underneath the glass surface if the desk, watching it turn. “I’m embarrassed to admit I purchased a one-way ticket to Vacuo that same day.”

“…What made you stay?”

What indeed. “As luck would have it, whether it be good or bad, a rather… problematic student was sent to my office that day. If I recall, this time around he had intentionally set the dust lab on fire.” Though, it could have also been the time he clogged the drain of the courtyard fountain. The record had become quite extensive. “Most of the other facility believed him to simply be a destructive sort. But I suspected different. Yet no matter how many times he was sent to my office, no matter how many conversations we had, I couldn’t get him to speak a word. He would just ask for his punishment in his crude way, pay it, and be back in a week.”

Ozpin rose to his feet, heading to his window that overlooked his former school. “That day though, on what I thought would be my last, I took a chance and acted on my suspicions.” His eyes darted to Oscar’s reflection as the boy approached. “You see, Beacon was always a school designed to have a low entry requirement. It was a school meant to train the best of the kingdom, but also be a shelter many could seek refuge in. Quite a few enrolled were those thrown from their own homes. So, I questioned him if that was what had happened to him and I learned more than I thought he would offer.”

He shut his eyes, still able to picture so clearly the seventeen-year-old Qrow that had eventually dissolved into tears, angry and pained by a world that didn’t want him and so full of hate at himself for a semblance he could not help. It seemed to be an impossible problem. Fortunately, Ozpin knew a bit about those. It was surprising to realize just how much of a difference a little empathy could go to heal a hurt soul.

“I did not stay that day for the war. I stayed because he helped remind me why being a professor could be so rewarding. I enjoyed having a part in my students’ lives, to help guide them into finding better ones.” He sighed. “I realize now that I’ve repaid him rather poorly for that.”

“So then, how are you repaying him any better by hiding away here?”

Ozpin turned to the boy, unsure if he was more surprised by his gall or his bull-headed honesty. In the background, Ozma started to chuckle.

“I did not lie before. I – we – do not know where to go from here.” And after so many lifetimes trying, maybe it was time to admit they just weren’t cut out for the task.

But it was Oscar, despite how he often quivered in the face of Grimm, who nodded and said. “Yeah, I know. And that’s scary.” He shifted on his feet, admitting softly, “But it’s even scarier facing it alone.”

That, more than anything, snapped him into wakefulness. You are meant to be guiding him Oz. What are you doing?

He placed a hand on his shoulder, knowing how much weight it was already carrying and much, much too much for one so young. “I’m so sorry, Oscar.”

“I am sorry too.” Ozma finally spoke, crossing over to them. “To both of you; that you must bear the burden of my mistakes as if they are your own.” He looked to each of them. “But if it is something we must bear together, then let us bear it equally, as we too should be.”

Oscar’s eyebrow rose in confusion, looking towards him for help. “Uhh…?”

He smiled. “He means that I need to stop treating you like a child."

“Oh.” He replied, seeming to take that newfound growth in. Whatever conclusion he came to made him nod once more, before he spoke again, “I’m sorry to both of you as well. I thought I was doing something right, with Jinn. I thought I was helping but all it did was end up hurting everyone.”

“You are certainly not the only one.” Ozpin agreed. The more he let those words sink in, the more he realized he was not the only one who needed to hear them. “Oscar?”

“Yes?”

“When we awaken, there’s someone I’ll need to speak with.”

The boy frowned. “Okay. But if he punches us again, I’m hitting him with the cane.”

Ozpin finally found it in him to laugh again.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thor’s character development and types of morality

@foundlingmother, I’m making this a separate post instead of reblogging because this is getting well off the trail of the original post and I don’t want to keep dragging poor writernotwaiting into it. Here is the thread of discussion and here’s what you said in your reblog:

That’s an interesting distinction between compassion and respect. I think I would say, taking into account @illwynd‘s explanation of the ways Thor shows that he’s compassionate, or at least trying to be, that part of Thor’s character growth may be that he feels worthiness is tied to, to use the Nietzschean terminology, a slave morality (the contrast between being a good man and a great king, for instance).

That might be some of what’s going on; Thor is probably picking up some (post-)Christian moral ideas from all the Western-educated humans he’s hanging out with. And of course I don’t expect most of the MCU writers to have a very thorough understanding of when certain moral ideas developed and where they came from. So of course to most writers and audiences, “becoming morally better” is going to be more or less synonymous with “becoming more selfless and altruistic.” That said, a noble value system certainly doesn’t preclude caring about other people, and the kind of narcissistic selfishness we associate with people like Trump is still an ignoble mindset, a way of being bad or contemptible according to noble value systems like those of ancient Greece or feudal Europe.

As I’ve said before in discussions of various philosophical issues in the MCU, I think the “good man vs. great king” issue is actually more about deontological vs. consequentialist modes of moral reasoning (I discuss the contrast a bit in this post on Thanos and Ultron and a bit more in this follow-up; apparently I also touched on it in this weird exchange). That’s a distinction that mostly comes up within what Nietzsche calls “slave morality” -- the standard examples are Kantianism and utililtarianism, both of which are secular adaptations of Christian morality -- but it can actually cut across the slave vs. noble morality distinction. So there can be deontological or consequentialist ways of implementing a noble morality. The reason I think that’s what Thor was talking about is this line: “The brutality, the sacrifice, it changes you.” I think what he had in mind was Odin’s willingness to sacrifice many Asgardian lives (and Malekith’s willingness to sacrifice most of his people) for the sake of victory. The reason this is relevant to ruling is that when you’re making decisions about large numbers of people with different needs and interests, you’re always going to have to trade the well-being of some for the well-being of others. I think we all saw the stupidity of Steve’s “We don’t trade lives” claim in Infinity War, because he was trading lives: in order to buy time to save Vision, he knowingly risked a whole bunch of Wakandan lives. In trying to keep his deontologist conscience clean, to remain “a good man,” he just hid from himself that he was being a bad leader making an indefensible trade, sacrificing many lives for one instead of vice versa.

This got very long, so I’m putting most of it under a cut.

A note on terminology, because it’s clearly very loaded: the “noble” and “slave” labels on moralities/value systems refer to whom the value system ultimately benefits. A noble value system is posited and maintained by the noble class (which may be either a knightly or a priestly caste) and works to justify and preserve their dominant position in society. A slave value system may or may not be invented by the lower classes of society (Buddhism, which counts as a slave morality in Nietzsche’s sense, was invented by a prince), but it definitely works to their advantage, because it protects the vulnerable and promotes social equality. The terminology is unfortunate in a context where the word “slave” immediately brings to mind the American system of Black chattel slavery; that is definitely not what Nietzsche had in mind. He was a classicist before he became a philosopher, so he’s usually thinking about slavery in the ancient world as well as serfdom in pre-modern Europe. This is definitely unorthodox, but I’m going to start using “serf morality” instead of “slave morality” to avoid irrelevant racial connotations.

The main difference between noble and serf morality, on the issue of caring for and helping others, has to do with the way you think about the obligation to do so. The type of serf morality that Nietzsche calls “the morality of compassion” or “the morality of suffering” says that you have an obligation to relieve all suffering, and to care about all others who suffer. (Sometimes an exception is made for those who make others suffer and you’re allowed to hate them and want them to suffer; sometimes you’re supposed to pity and help them too.) You’re supposed to make the happiness and/or well-being of other people your primary goal in life, and you’re supposed to care about everyone, regardless of their relationship to you. Some forms of (post-)Christian morality permit you to prioritize people to whom you have special relationships (family and friends), but the purest form of this morality requires you to care about everyone equally, and ascetic or monastic Christianity discourages forming special relationships because that will inject an element of selfishness into your desire to benefit certain people. The purer forms of this morality -- philosophical Christianity, with or without God -- also consider the salvation of one’s own soul to be an unacceptably selfish motivation for helping others. Ideally, everyone’s entire motivation is to eliminate the suffering of others, not because of anything particular about them or their relation to you, but simply because they exist and they suffer. The morality of compassion is universalistic, egalitarian, and outward-focused.

Noble value systems allow agents to be selective in whose well-being they care about. Special relationships are extremely important. Traditionally, this usually means family relationships and comradeship-in-arms because aristocratic societies have conventionally been very heredity-focused and martial. But it also includes what Aristotle scholars call “character friendships”: friendships formed with kindred spirits because of mutual admiration for each other’s qualities and abilities. The standards of a noble morality only apply to a small class of people, namely, the nobility; it’s largely silent on how non-nobles should behave, and different versions have different rules about how nobles should treat non-nobles. Respect is reserved for other nobles, but some noble moralities, especially medieval hybrids of Christianity and Roman/pagan noble morality, also encourage benevolence, generosity, and forbearance toward commoners. Under certain circumstances, nobles can be obligated to care about the well-being of certain non-nobles, but it’s virtually always a matter of regarding them as your own, as your responsibility. Lords are supposed to care about the commoners who live in their lands and are obligated to protect them and provide for them; Christian knights are supposed to care about other Christians. In the ideal city described in Plato’s Republic, the guardians (the warrior class) are compared to guard dogs who are friendly to their master’s family but hostile to strangers. Their responsibility is to all the citizens of their city, even the lower-class ones; to that extent, all citizens are their own in the same way family members are. Caring for others in noble moralities is selective and is always a matter of regarding certain others as an extension of oneself and, therefore, regarding their well-being as part of one’s own well-being. Noble moralities also don’t preclude sacrificing yourself for others -- that would be very silly in a warrior’s code of conduct -- but self-sacrifice is not selfless when you’re sacrificing a part of yourself (your life, your body) for another part of yourself: the people who matter to you, your family, your comrades, your countrymen. There’s also the understanding that those who sacrifice themselves in such a way will be remembered and honored; you exchange a brief life for long-lasting glory.

(To be clear: Nietzsche was not in favor of going back to a Homeric-style warrior noble morality; he was very aware of the many cultural changes that have made that both impossible and undesirable, mostly involving the internalization and intellectualization of human life and activity. He was imagining communities being constructed and battle lines drawn on the ground of ideas, not geography or ethnicity, which can no longer defensibly be said to have the significance they once did. Nationalism, he thought, was a spasm of an outdated worldview. But he also questioned the value of selflessness and wondered about the end goal of a moral system whose primary motivation is the alleviation of suffering.)

So... I’m not sure if Thor’s moral improvement was a matter of moving toward serf morality or just becoming a better representative of noble morality. I definitely think Odin’s goal was the latter. “Humility” considered as an absolute value, as in the more of it the better, definitely belongs to serf morality, but there is a place for humility as a balancing quality in noble morality: Aristotle places magnanimity, or “greatness of soul,” as the virtue at the mean between vanity or arrogance -- claiming more honor than you deserve -- and an excess of humility or “smallness of soul,” which is effectively meekness, laying claim to less honor than you actually deserve. Thor was arrogant and vain; he invited adulation, he overestimated his own abilities and (as we saw in the deleted scene) the amount of credit he deserved for victories he shared with others. He needed to be shown that he isn’t invincible and that he sometimes has to rely on others, but the goal wasn’t for him to become self-effacing. His maturation also involved a greater awareness and sensitivity to the needs of others: contrast his complete obliviousness to the danger his friends are in during the Jotunheim battle with the slow-motion sequence in the Puente Antiguo battle where Thor looks around and really takes in how much his friends are struggling. That -- along with his acknowledgment that he might have done something to wrong Loki and his attempt to apologize -- might be considered an increase in empathy and/or compassion; in any case, it’s definitely doing a better job of caring for the people with whom he has a relationship, and for whom he is responsible. Making friends in Midgard does seem to have done something to widen the scope of his compassion and/or benevolence, since he now sees a problem with wiping out the Jotnar.

#moral philosophy#noble vs. slave morality#deontology vs. consequentialism#consequentialism vs. deontology#noble morality#slave morality#consequentialism#deontology#mcu#mcu meta#thor meta#nietzsche#thor#thor 1#avengers infinity war#philosophy

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

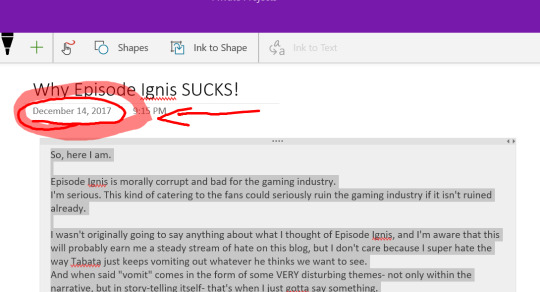

Why Episode Ignis SUCKS!

So, here I am.

Episode Ignis is morally corrupt AND bad for the gaming industry.

I'm serious. This kind of catering to the fans could seriously ruin the gaming industry if it isn't ruined already.

I wasn't originally going to say anything about what I thought of Episode Ignis, and I'm aware that this will probably earn me a steady stream of hate on this blog, but I don't care because I really hate the way Tabata just keeps vomiting out whatever he THINKS we want to see.

And when said "vomit" comes in the form of some VERY disturbing themes- not only within the narrative, but in story-telling itself- that's when I just gotta say something.

None of this is fan theories or trying to figure out what's really happened or trying to fill in plot holes. It's clear both endings have plot holes. This blog is just WHAT'S WRONG WITH EPISODE IGNIS AND WHY I HATED IT. And why, in my opinion, it didn't fix anything.

I've compiled my reasons into one little...big blog. Divided into chapters for organization.

(I'm not borrowing anybody's opinions or theories, btw. I wrote this blog before I even knew anyone had similar fan reactions to mine about the alternate ending.)

The date I started writing this in One Note was Dec 14, in case anyone is interested. No? Okay.

So buckle up, and don't say I didn't warn you...

HEAVY SPOILERS UNDER THE CUT

CHAPTERS:

1. IGNIS IS OUT OF CHARACTER

2. IGNIS IS A SELFISH PRICK

3. IGNIS TAKES OVER EVERONE ELSE'S ROLE

4. THE ORIGINAL STORY'S BUILD-UP AND CLIMAX IS GROSSLY OFFSET

5. WHY THE ORIGINAL STORY IS BETTER

6. COMPARING FFXV'S STORY TO OTHER GREAT EPICS

7. BAD MORAL/MESSAGE

8. THIS ENDING IS NOT CANON

9. PURE FANSERVICE

10. LINGERING QUESTIONS

11. OTHER THINGS I PERSONALLY DIDN'T LIKE

12. IN CONCLUSION

Okay, saying episode Ig sucks is kind of shameless clickbait, I admit. The episode proper was actually great and I really enjoyed it. It was compelling, exciting and answered enough questions. The alternate ending part... Not so much.

Keep in mind that most of my criticism is directed toward the Alternate Ending, and from a story-teller's vantage point, but there is a bit directed toward the main episode as well. And this is just STORY criticism. The gameplay elements of Episode Ignis and the visuals and music were great. No complaints there.

So, let's get started!

1. IGNIS IS OUT OF CHARACTER

We're all familiar with the bespectacled, level-headed, pensive advisor that is Ignis Scientia. With his cool logical methods, he is the one the bros- and most importantly Noct- rely on as their anchor. The voice of reason in the medley of chaotic situations which they often find themselves.

But, watch out! Throw a magic ring and a prophetic vision into the mix, and he becomes a one-man recipeh for disaster, who's ready to literally burn the world!

See what I mean:

-Ignis doesn't use any of the cool decision-making skills we've come to expect from him in the main game. He's all raw emotion and flights of fancy now.

-He's never shown signs of obsessive protectiveness over Noct before. He cares, yes, but one little vision makes him completely lose his ability to examine the situation and think clearly. This is a direct contradiction to everything we've previously learned about his personality!

-The creators of episode Ignis also based the alternate ending on the comradeship that was built up in the story parts that THEY CUT OFF.

The close bonds that the bros come to forage during the later parts of the game never happen, thus making their actions (and especially IGNIS'S actions) unrealistic.

Remember, all that's happened to the bros at this point is a few hours on the road trip in the regalia, they've captured a few summons, collected a few weapons... Nothing has really happened. No death, no vision loss, Ignis and the others act like the story proper has already taken place.

2. IGNIS IS A SELFISH PRICK

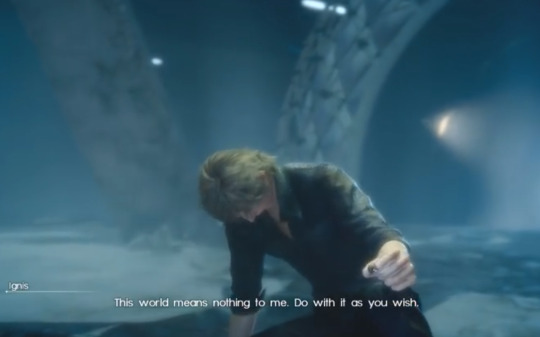

The alternate ending seems innocent enough. Ardyn threatens to kill Ignis, and he has little choice but to put on the ring and defend himself. But it's what Ignis says first that is highly disturbing. Ignis's words are at best emotionally compromised-- at worst, EVIL.

Let's listen in on some quotes:

-"This world means nothing to me. Do with it as you wish!" (To Ardyn) (TO ARDYN!!!!)

-"A world without him isn't worth saving!"

??? What about Prompto and Gladio? What about Iris, Cindy, Cid and Aranea, you BLATHERING BOBBY-SOCK??? ...Actually they never make nice with Aranea if this happens, do they... Huh.

-"I refuse to let Noctis sacrifice himself!"

Again, "I refuse to do this." "I refuse to do that." Ignis isn't thinking about what is really best for Noct and the others. He's thinking about himself and what he wants or doesn't want.

Isn't that Noct's choice? Did you ask him? Ig only wants it to go HIS way. Like, Dude, just because your bud might die, you'll let the world burn? That's not your choice!

And I'm sorry, this isn't self sacrificing or beautiful. It's DANGEROUS for Ignis to be thinking this way, much less get praised for it. He's willing to throw away everything everyone has sacrificed up until that point. Regis, Luna, Nyx, EVERYBODY. Ignis didn't 'rebel against fate'. He acted selfishly without consulting any of his friends, and only by the good grace of Tabata did it work.

-Ignis doesn't believe in Noctis. Regis and Luna both believed in him, but Ignis sees one vision and freaks the hell out. He is like: "No, I will make all these decisions for Noct. I will not allow him to decide if he wants to go through with it. I'll risk burning the world down instead."

Whatever happened to "Stand by Me"?

-after he learns of Noct's potential death, Ignis tries to make Noctis discontinue his journey. Even though he knows now that Noct is the only one who has the power to save the world! And just as Noct is beginning to realize how important it is! Just on the heels of Luna's death!

He's only thinking that he doesn't want Noct to die because he's SELFISH.

-Ignis treads dangerously close to the same path as Ardyn in the alternate ending and it's NOT RIGHT that he can do the same thing, yet have a better result. Selfishness ALWAYS leads to harming those we wish to protect most.

-I CAN'T BELIEVE THE LUCII FOUND HIM WORTHY OF THEIR POWER WHEN HE JUST DECLARED HE WOULD LET ARDYN BURN THE WORLD DOWN!

Sense made: 0%

3. IGNIS TAKES OVER EVERONE ELSE'S ROLE

Say hello to you new protagonist everybody! Ignis Scientia effectively usurps the lead position from Noctis. (And everybody else's positions too.) Watch this:

-Ignis takes over Noct's role of the game's protagonist/hero.

-Ignis takes over Gladio's role as Noct's guardian. He says something like: "I swore an oath to protect him!" No, Ignis. That's Gladio's job. You are a cook, remember? Now be a good boy and come up with a new recipeh for us.

-Ignis takes over Prompto's role as Ardyn's hostage in Gralea.

-Ardyn reveals his true identity to Ignis (a complete stranger) and Noctis never finds out??? Idk.

-Ignis takes over Ardyn’s role as the guy who’s gonna burn the world.

-Ignis takes everyone's role for himself except his own, which was to be the pensive, intelligent and dependable advisor. He totally takes leave of his brain!

4. THE ORIGINAL STORY'S BUILD-UP AND CLIMAX IS GROSSLY OFFSET

-The train ride to Gralea, Noctis coming to terms with Luna's death, finding the strength to wear the ring-- all this character development and story arcs NEVER HAPPEN! Noct just decides on the spot that he's gonna hop right into the crystal and... That's basically it. No doubts or fears or hesitation like he had in the original story. Nope, we skip all the development and cut right to the chase.

The previous build-up made him a human, relatable and interesting character. It made us stand up and cheer for Noct. Now, just the sight of Ignis messed up on the ground and BOOM! Skip straight to the ending. Character development and struggles be damned!

Such an immediate decision as Noct makes is not only highly unrelated to his character, but doesn't even make for a good story. I don't know how people say it does.

-Everything becomes too easy. Luna's death and Iggy's vision loss stirs up some serious turbulence that the bros have to work out before they continue their journey. All this is skipped in the alternate ending.

-Ignis's vision loss becomes just a tease.

-There's no penalty for using the ring's ultimate power to banish Ardyn for good. Noctis's survival doesn't make any sense.

It's kinda easy to defy fate when there's no consequences for any of your actions, eh? Seriously, there's no consequences to putting on the ring and summoning the Knights of the Round to defeat Ardyn and restore light. This is wildly out of whack with every way the ring's magic has worked until this point. (That is: draining life force in exchange for magic.)

-Noctis doesn't die defeating Ardyn now? Just because Ig used the ring on him ten years ago, doesn't mean he's still weakened all this time later. And if it does, then we should just do this all the time. There's no good explanation for this that I've seen.

-And why would Ardyn still go through with his plan. I mean, you can't exact revenge on your own bloodline and the crystal if you're not strong enough to at least take him down with you, Ard.

-Luna and Noctis's "love story" (big fan) is stepped all over. Not that it was well written to begin with, but now her death has no effect on Noctis or anything that comes after.

I guess Tabata's no good with commitment to relationships.

-Ignis trying to "change fate" is like saying every other character didn't try to figure out EVERY possible way to save Noctis. Do you think Luna wouldn't have tried to find a way to save her only friend? DO YOU THINK REGIS WOULDN'T HAVE TRIED TO FIND A WAY TO SAVE HIS OWN SON?? No, they were basically stuck-up bigots who were willing to sacrifice Noct because it was convenient.

Yep. Not buying it.

I mean, Ravus looked for years for another way for Luna to fulfill her calling without spending life force (even selling his own soul in the process) and couldn't do it, and suddenly Iggy just snaps his fingers and BOOM! "I've come up with a new way to fix everything!"

Imma call bogus on that one.

-Now the Genesis artwork makes no sense, because Noct never had a blind companion.

-Luna's t- t-...tr...TRUE feelings for Noct are never disclosed via Gentiana/Shiva.

-Ardyn is now on the losing end for the bulk of the game. Horrible dramatization!

-The world of darkness now has reduced meaning because everyone now knows Noct is gonna be back and kick Ardyn's backside in a bit.

5. WHY THE ORIGINAL STORY IS BETTER

I say "story" and not "ending" because it's pretty obvious how much of a change there is to the story, depending on which ending you choose.

So, there's a generally accepted fan theory that Noctis never had a choice in his destiny and was basically funnelled down the path to complete it by the prophecy and/or the Astrals and/or the Knights of the Round.

Not going to name any names, of course, but there's this thing that the FFXV fandom says: "Noctis never had a choice but to sacrifice himself. That he was the slave of the prophecy and the Astrals were using him." That he was a victim of circumstance. That it "wasn't fair".

Like somehow the prophecy and Astrals were forcing Noct to kill himself.

I've never seen any real evidence to support this. On the contrary, no one is forcing Noctis to do this.

The prophecy's not something you can rebel against. A prophecy is just a foretelling of something that is to come. It doesn't force anybody to do anything. In fact, it's only fair that Noctis know what's coming if he chooses to go through with his destiny.

A last chance to turn and run from it if he so wishes.

In fact, it would be unfair if he had no warning whatsoever.

The magic of the ring is what kills Noct. We know that the more magic one uses, the more life force is drained (see KG and ep Ig). Like simple Physics: what goes up must come down. He who uses the magic must sacrifice life force. That's what magic runs on. (like king Regis ages more quickly as he uses magic to keep up the new wall) It's nobody's fault.

As the only one with the power to use as much magic needed to defeat Ardyn, (even the Astrals can't) Noctis has a choice to make. Surrender his life force to kill Ardyn, or give up and run.

THAT is Noct's choice.

And he makes conscious decisions to sacrifice himself many times throughout the story. This is what makes our heroes and heroines worth looking up to. Putting aside their own desires and doing the best for everyone.

"I think I can do it... I won't let you down!" He tells Luna.

Still, Noctis had many chances to run. He could have turned from his responsibility and turned back. But he knew his Dad and Luna and the bros and the WORLD was counting on him. By the time he emerges from the crystal we see his resolve. He's made his decision and he'll see it through.

Because only HE can. Only the chosen. By the ending campfire scene and when he takes Prompto's photo as a keepsake, it's clear he'd made his choice. And the bros RESPECT IT. They STAND BY HIM. There's none of this second-guessing stuff or making decisions for Noct.

As for being a victim of circumstance, aren't all heroes?

Ardyn, for one. Here we have an example of a man who could have been a hero, but his jealousy of his brother led him to do things that led him to hurting those he once swore to help. Noctis didn't let this responsibility drag him into the depths of despair and spite like Ardyn did.

The important thing is that Noctis makes the right choice. If he didn't, he would have ended up like poor, corrupted, jealous Ardyn.

As I said before, Ignis treads dangerously close to the same path as Ardyn in the alternate ending, and it's NOT RIGHT that he can do the same thing, yet achieve a better result. Selfishness ALWAYS leads to harming those we wish to protect most.

A direct corruption of morals.

6. COMPARING FFXV'S STORY TO OTHER GREAT EPICS

Seems like a good time to reference Lord of the Rings, since it's obvious Final Fantasy gets a lot of inspiration from there:

For example:

It was never Frodo's choice to inherit Sauron's ring of power, but as the story progresses, he learns to accept his burden, because he understands that if he can't destroy it, then no one will. Even as it becomes abundantly clear that it will cost him his life.

It's the doubt and fear that Frodo overcomes that makes him a true hero. He's faced with a situation no one would choose, but isn't that how all heroes are made?

In the end he chooses to do what's right.

Likewise Noctis:

As the chosen King of light, Noctis finds himself in a situation no one would choose. But it's how he handles it-- forces on in spite of everything -- because he knows it has to be done. And like Frodo, he finds himself the only one who has the means to do it. And he does it because it's the RIGHT thing.

And that's the ONLY kind of hero worth looking up to.

Other elements of the two stories match up too, like four protagonists set out on a journey, one with a very special mission, although they all will have to sacrifice part of themselves to see it through.

Speaking of which, let's take a look at the similarities between the theme songs:

In Dreams, by Howard Shore:

When the cold of winter comes,

Starless night will cover day,

In the veiling of the sun ,

We will walk in bitter rain,

But in dreams,

I can hear your name,

And in dreams,

We will meet again,

And now

Stand by Me, by Ben E. King:

When the night has come,

And the land is dark,

And the moon is the only light we'll see,

No, I won't be afraid,

Oh, I won't be afraid,

Just as long as you stand,

Stand by me,

As you can see, both songs tell of the world being enveloped in darkness, but the bravery of the heroes spurs them on to complete their task with the help of their friends, because the world and all good things in the world DEPEND ON IT.

And, yes it's nice if there's an easy way out. A quick way to escape hardship and possible death. And in real life this even happens a lot, but those are the stories you never hear about because there's no sacrifice, effort and determination in them.

For instance, if the Great eagles were to grab the ring of power, fly over to Mt. Doom and plop it in the lava, that wouldn't be a real story worth listening to.

Likewise, if Iggy were to put on the ring of the Lucii FOR Noctis, and defeat Ardyn halfway through the

game, pretty much skipping the journey and the evolution of the characters, then that wouldn't be a good story, would it?

Why do you think you're so heart broken when Noctis finally does decide to sacrifice himself? Because, you got to know him and his friends throughout their journey. Their struggles. You felt like you were actually there through the ups and downs, observing all their actions. Taking part even. Through their hardship you learned to LOVE these characters and care about the choices they make.

That's how it should be. That's what makes every good story GREAT.

Look around. All your favourite stories follow the same pattern. It's not something we can dispense with to make ourselves feel better. It's OUR responsibility not to.

Okay, that got a lot deeper a lot faster than it had to, but you have to see, that Noct's sacrifice is in no way unfair or bogus. It's HIS choice.

7. BAD MORAL/MESSAGE

-So, the message the alternate ending portrays is basically: "Just act irrationally and irresponsibly on your own whims and desires. Without consulting your friends and the people who's decision this REALLY is. Things will come up aces ;)"

-Throw out your rational-thinking self-sacrificing heroes boys and girls, because here's one hot-head who NONE of the rules apply to!

-Heroes are made by the great deeds they do, and the obstacles they overcome. I guess heroes don't overcome their struggles anymore. They just go berserk and look for the quickest, easiest way out. And yay! They find it! What d'ya know. ;p

-The theme of Final Fantasy is not necessarily to "rebel against fate, or the powers that be". The theme of Final Fantasy has always been to overcome your obstacles, push forward and to do WHAT'S RIGHT, no matter the circumstance. No matter what the cost. Even if it's your own life.

That's what's always been important about the Final Fantasy games I'VE played.

That's the message I've always taken away from not only the Final Fantasy stories, but all great adventures in general.

That's the true message to be learned.

8. THE ALTERNATE ENDING IS NOT CANON

-People have noted already that the ending is called "Possibilities" therefore indicating that you can take it or leave it. Like something that might have happened if Ignis had taken Ardyn up on his deal to come to Gralea.

-You can only play the alternate ending if you ALREADY played the first one, which leads one to believe that that's how the game is supposed to be played.

-You're seriously gonna make me invest in a DLC to get the "Canon" ending? (A whole year after the game came out?)

-Square Enix has even confirmed that the ending is not canon, but rather a 'possibility'.

9. PURE FANSERVICE

-Just because fans bugged hard enough for an easy way out. A blatant suck-up! At a time when fan service is butchering the industry! Calling this disaster "canon" is giving Tabata an easy way out of his responsibility. A responsibility to do it right the FIRST time, not just patch all your mistakes later. (If you can call this "patching") We paid for the GAME, not fan service.

-We all wish for that perfect ending where nobody dies and everything turns up roses, but at the cost of proper development, REAL heroic sacrifices and grievances and battle scars, I say NO.

10. LINGERING QUESTIONS AND PLOT HOLES

-So, remember that part when Noctis is lying there on the ground, and Ignis is lying there too and Ardyn offers to take Ignis to Gralea to lure Noctis to the crystal...?

The key words were: Noctis is just lying there... Yep.

-What's up with those visions? Luna sending them? There's no way she would send those to him, because why? He's a random stranger who will just freak out and burn down the world if he sees them.

It seems only to set up the alternate ending. And that makes me really mad.

There's no way Luna would give Ignis the idea to turn from his path. Not after how strongly she and Regis and everybody believed in Noct. There's NO reason Ignis needs to know this. UGH!

-Why does the ring hurt when Ig puts it on? It didn't hurt Nyx.

-Ardyn reveals his true identity to Ignis (a complete stranger) and Noctis never finds out??? Idk.

-Why does Ardyn taunt Ignis (a total stranger) into thinking he's going to kill Noct? What purpose does that serve?

-Why was Ardyn shocked to see the ring in the alternate ending, but in the main episode he wasn't worried?

-Why could Noctis command the crystal so easily in the alternate ending, when it was ignoring him in the main game?

-What happened to the Niflhiem Empire? Did Ardyn still kill Iedolas?

-Why doesn't Ardyn kill Ravus/turn him into a demon? So much for wiping out the bloodline of the oracle. :p

-How come in the original story, Ravus is fooled by Ardyn disguising himself (as Noct),and Ardyn then kills him, but in ep Iggy, he sees right through the fake Gladio?

-And to top it all off, Iggy walks up to Noct at the end and mouths "Your Majesty", which is already starting to spark theories that that was ARDYN!

Personally, I don't buy into the theory, but why the tease?????

11. OTHER THINGS I PERSONALLY DIDN'T LIKE

-It was short. Come on, we waited until December for and hour and a half of gameplay? Episode Prompto was way longer and fuller. (And raised a lot less questions...)

-All fangirl squealing aside, Iggy's outfit changes were kinda lame.

-All that money spent on an alternative ending when the main game is starving for patches...?

-Throughout the episode proper, we get dumb clips that intentionally set up the alternate ending. Like those visions and Ravus not dying/turning into a demon. They don't even serve a purpose into the main story.

-The blatant disregard for commitment to a story.

-The voice acting was a bit off in parts. Like, sometimes Iggy is just standing there screaming. Lol

-Ignis didn't come up with ONE new recipe!

12. IN CONCLUSION

-Tabata is spineless!

-Ahem, sorry. So yeah. Everything in this new ending is pretty messed up. The first one had it's issues, but this one to me is 10,000,000,000,872.5 times worse. It's hollow, with no backbone, and plays out like a cheesy fan fic I would pass up on AO3.

-Look, I love sweety, fluffy, nonsensical endings and happily ever afters and shippy ships too, but if Tabata sees the rate at which we're lapping up this sugar and rainbow vomit, he'll wonder why he should even waste time developing fleshed out characters with real struggles and cohesive stories, and we'll be stuck in this cheap fan service HELL forever!

And that's disrespectful to true story tellers and well established character arcs everywhere!

Disrespectful to the name of Final Fantasy!

-So yeah. That's all I wanted to say. I'll say no more on why I hate the alternate ending, because I know a lot of people liked it. I just wanted my friends to know why I'm won't be hopping up on this alternate ending train any time soon. ^^

Thanks for reading. Stay epic, you guys!

159 notes

·

View notes

Note

What sleeping positions do the Royal Knights couple make (Not in the R-18 way! As in fluffy way)?

Okay I got around to answer this one but sorry if my words doesn’t make sense I tried my best. This answer is also base on the drawing I made which can be found here. Take it as a visual aid I guess! I will only list my 4 RK OTPS here and this is my personal interpretation so if your ship is not here, sorry about that.DukemonxOmegamon

I believe their sleeping positions would be “the Nuzzle” or “The Sweetheart’s Cradle”. Like this position stated, it is a snuggling position that has a high strengthening sense of comradeship and protection. One that requires a high level of trust in one another. Duke and Omega are already close friends since the early RK days and they really trust each other both knowing each other strengths, faults, and insecurities. I mean Omega killed him one time in that movie and get depressed about it and Duke came back alive with no grudge against him. If that’s not love IDK what that is.

DuftmonxGankoomon

Okay this one is tricky mainly cause I cant find the exact word for this sleeping position. Duft really values his space as he’s not use being in a relationship with someone and Gankoo willingly give the space he needed. But overtime after their relationship and trust grew, Duft will start asking for his lover’s attention and being the inner softy he is, Gankoo will gladly give. Let it be a cuddle, a kiss, or a simple stroke of the hair as long as they are happy that’s all that matters.

MagnamonxUlforcemon

Hmm their sleeping position would be a mix of the two mentioned above. While Ulforce craves the attention of his lover, Magna would be somewhat the opposite. Not to say that he doesn’t like that Ulforce fawns over him but more of feeling embarrass off the PDA but that feeling stems of the feeling of insecurity towards himself. Magna values his independence and space of the relationship and it would take some time for Ulforce to adjust and making a compromise between intimacy and independence, allowing the best of both worlds in their relationship.

Lord KnightmonxDynasmon

Lord Knight and Dynas likes to spoon whether its before or after their lovemaking. They take turns being the big or small spoon or in some cases, doing the loose spoon it doesn’t matter as long they are entangle and having close contact with one another. Like the sleeping position states, it demonstrates a dynamic where one partner is protective over the other and it goes without saying that Lord Knight and Dynas really trust each other and willing to put their lives at risk to protect the another.

#Royal Knights#omegamon#Omnimon#dukemon#Gallantmon#omegamon x dukemon#duftmon#Leopardmon#gankoomon#Duftmon x Gankoomon#ulforceveedramon#ulforce#Magnamon#Ulforceveedramon x Magnamon#LordKnightmon#crusadermon#dynasmon#LordKnightmon x Dynasmon#replies#GOD THIS IS TOO LONG SOMEONE SAVE ME#digimon

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Prussia’s Reflections” is a piece I wrote as if it was one of Gilbert’s diary entries to practice not only first person writing but also to practice writing as Gilbert would. In this piece, Gilbert talks about his reflections of his rise and decline in power, German unification, reunification, militarism, and other such things. It is not a formal piece but instead I imagine Gilbert is just getting his thoughts down. If he actually wrote this, it would be in German, and most likely formal German therefor this is why there are not many colloquialisms at all in this piece. Enjoy.

Many would think that I would have given up by now, considering my situation. I have given up scant few times in my life before and this was not due to my own wanting but for the sake of my men, my people. I will carry on until I am dead, and this perplexes those around me. Nations thrive off the fall of those around them, so of course they want me to give up. But I won't, I like to see them squirm and suffer, to see their anger rise like bile in the back of their throats when they see me, when they realize that no, I am not dead and I have no intention of dying for quite some time. This gives me a great sense of satisfaction.