#with my eastern fashion

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It's called the Cat's Cradle cuz Bea's a baby butch.

#fandom#warrior nun#sister beatrice#*mutters to myself*#western viewers all missing#all those masc#eastern style cues#bea: ope I'm east asian#lemme just sneak on by#with my eastern fashion#stealth butch ftw#sorry did it get dark in here?#my bad lmao

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

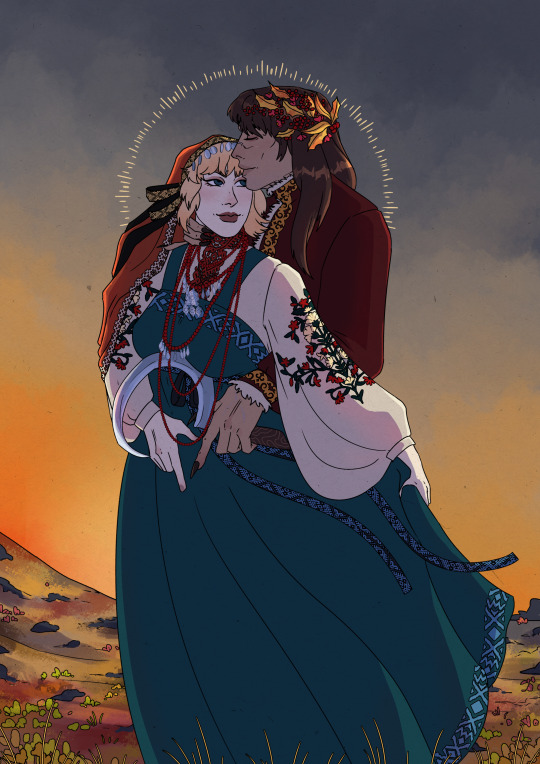

Graveyard spirit in Biłgoraj folk costume

#my art#dress history#fashion history#vintage#historical fashion#folk#folk costume#folk dress#polish folk#polish folklore#polish culture#polska#poland#slavic folk#slavic art#slavic culture#slavic#eastern europe#folklore#traditional dress#biłgoraj#strójbiłgorajski#spooky art#spooky aesthetic#spooky vibes#ghost

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

Byzantium

#illustration#artists on tumblr#my art#digital art#women artists#drawing#art#procreate art#female artists#character design#byzantine empire#eastern roman empire#historical fashion

654 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finished something

#i finished my masters but i started phd#by accident#its complicated#so i work at lab 8h a day and then fall asleep on my armchair mostly#comic#historical#history#comic art#historical art#folklore#folklore art#historical fashion#eastern europe

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

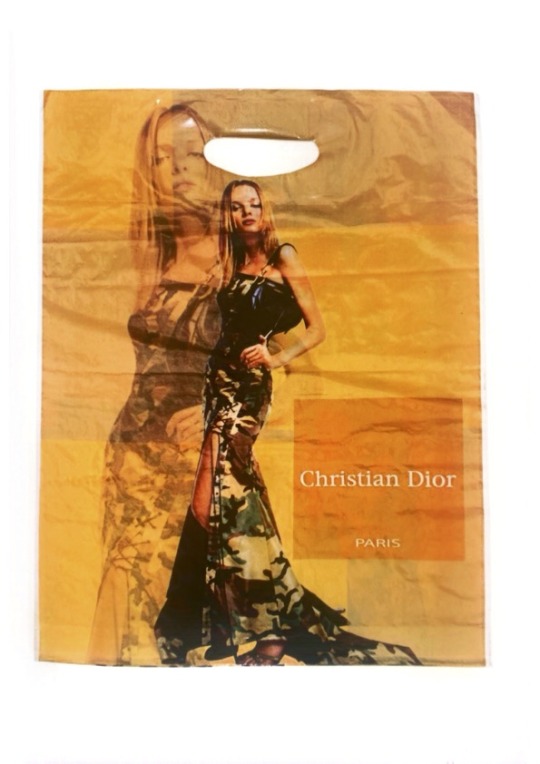

Eastern Bloc Shopping Bags from Fashion Magazine by Martin Parr - Summer 2005

#Martin parr#Martin parr fashion magazine#photography#eastern bloc#eastern europe#soviet union#christian dior#dior#my scans#scans#scanned by me#ukraine#2000s#dkny#vintage ads#odessa#2005#plastic

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hungarian woman wearing a black ruffled blouse, sitting on a black chair, in a black room. Medium format color positive film.

#black#black dress#hungary#black hair beauty#black eyes#black fashion#ruffles#woman#ai portrait#ai photography#my analog ai#medium format#european woman#eastern europe#pale girl#goth vibes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I walked around a tree for nearly ten minutes trying to find the bird that was screaming through the leaves and it turned out to be this fledgling eastern kingbird

#find me where the wild things are#eastern kingbird#fledgling#i shouldve guessed there were sooooo many adults flitting about#it did not respond to pishing so i had to use good old fashioned tactics (my eyes)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

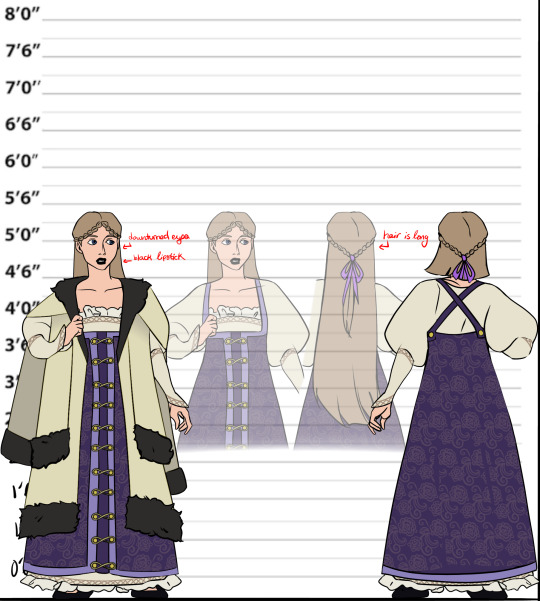

5 Months Improvement in my character design!

#You can tell I made a incredibly detailed pinterest board with historical/fantasy fashion info#EASTERN EUROPEAN MEDIEVAL DRESSES MY BELOVED#oc#original character#nemma#Nemma Ufali#fantasy#fantasy oc#character art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

Tradicional dress from Croatia

CEREMONIAL RECONSTRUCTED NATIONAL COSTUME FROM 1940

This beautiful reconstructed costume comes from Gornji Kraljevec, made with a lot of love and attention to tradition. A marquise shirt, with beautifully embroidered sleeves, along with a luxurious skirt, makes this costume a true jewel of our cultural heritage, A scarf was worn on the shoulders, while young girls braided their hair into braids, and older women wore a headdress. Special attention was paid to details in order to preserve the originality of the costume. It is interesting that research has revealed similarities with the costumes in Slovenia, especially in the areas where the emigrants from Međimurje lived.

#my post#tradition#folk#folk art#folk aesthetic#folklore#croatia#Međimurje#slavic#balkans#eastern europe#Instagram#1940s#1940s fashion#1940

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

every single thing about medieval and renaissance era clothing only talks about englandfranceburgundyspaingermany. what were the serbs wearing???? what were the poles and the hungarians wearing??????

#i do know this a little bit and i have a pretty good idea of the male fashion and how it was inspired by byz and otts empires more than west#however my issue is there are so much fewer depictions of women that i have found from those countries and i can't tell if their clothing#was also eastern inspired or skewed more towards west? i mean i am kind of thinking that because that's what a lot of pictures show but als#I don't want to take pictures made by west euros into account because they're probably just drawing women in what they thought#their women wore. then again men often adopt foreign styles more than women pre renunciation#like crusader kingdoms men#plus whenever you try to research this stuff the national folk costumes of these countries come up and idk how that all fits in#considering that so much of those were more a product of 20th c nationalist movement than tradition

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do you guys wear shoes in the house? I don’t. But what about you guys?

#reblog and say your answer#so when my nurses came over separately each time#They were wearing shoes and stepping on the carpet#I think most asians & middle easterns don’t#Doesn’t it feel uncomfortable#lol#text#reblog game#positivity#fashion#shoes#asians#afghans

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

I NEVER THOUGHT I’D SEE TAY TAWAN AND MADS MIKKELSEN IN THE SAME PLACE, LET ALONE SEEING THEM TAKING SELFIE TOGETHER???!??!??

BUT THE FACT THAT IT HAPPENED??? BLOWS MY MIND TBH

#it’s like my western fave met my eastern fave and I’M LOSING MY MIND?!??#mads mikkelsen#tay tawan#zegna fashion show

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palm Sunday in Łyse, Kurpie Zielone (2024)

#my art#dress history#fashion history#historical fashion#folk#folk dress#folk costume#traditional dress#slavic folk#slavic art#slavic culture#slavic#polish folklore#polish folk#polish culture#polska#poland#eastern europe#kurpie zielone folk costume#kurpie zielone folk dress#kurpie zielone#kurpie#palm sunday#niedziela palmowa

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

resisting the urge to list like 20 models every time i’m trying to exemplify a trend in modelling

#the eastern european girls of the late 00s and early 2010s? oh here’s a laundry list#you want evidence east asian models have grown exponentially in perceived marketability since the early 2010s and the realization in the#western fashion industry that china and south korea in particular are huge luxury markets? well here are 40 models i can mention in 30 sec#to prove my point#p

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tags

#found images#image archive#eastern europe#people#pets#animals#fashion#interior#location#nostalgia#film#my images#flickr finds#flickr find#web finds

1 note

·

View note

Text

Polychrome jewellery like these earrings are part of a really, really old artistic tradition! The first examples come from early Bronze Age, like this pectoral (brooch) worn by a princess in Middle Kingdom Egypt:

Pectoral and necklace of Sithathoryunet with the name of pharaoh Senwosret II (c. 1887–1878 BCE), from his pyramid in Faiyum, Egypt.

So, the process of crafting these pieces (called cloisonné) is exactly as painstaking as you'd expect. First, the jewellers would cut gemstones (in this case garnet, turquoise, carnelian, feldspar and lapis lazuli) into precise shapes according to the design. Then, they would weld or hot-solder thin gold wires onto the gold base (usually cast from a lost-wax mould) to create the "lines" between the stones. Finally, the stones would be carefully glued into the slots, creating complex, multicoloured designs like you'd see here.

The ancient world was a deeply interconnected place: the deep blue lapis lazuli on the above piece was likely brought to Egypt all the way from modern-day Afghanistan. It naturally followed that the cloisonné technique took off in more than one place. While the thin-wire style came to define Bronze Age Mediterranean jewellery, the thick-walled style of medieval Byzantine cloisonné originated in another place: the Inner Eurasian steppe.

Kushan/Yuezhi pendant and neckwear (1st century CE) from the Tillya Tepe (Golden Hill) burial site, northern Afghanistan.

We often think that steppe peoples lived in small, freewheeling tribes, idly wandering endless open plains. This wasn't actually the case! They lived (and still live) a highly technical lifestyle, moving like clockwork between grazing grounds, trading towns and winter quarters sheltered by mountains and forests.

And most importantly: they were enthusiastic metalworkers. Steppe peoples prized their mines and smithies, whether as places they'd drop by on the way to the next pasture or as year-round homes for groups of professional metalworkers employed by nomadic nobles.

The Altai Mountains in Central Asia, the ancestral holy ground of many steppe peoples, were also one of the world's largest and richest mining and metallurgical complexes, going all the way back to the late Bronze Age. Starting in the early 1st millennium BCE, we started to see a flourishing of this style of ornaments, cast from gold or silver and inlaid with complex, often multicoloured gemstone designs:

Left: Sarmatian belt buckle (2nd-1st century BCE) from Sadovy Kurgan, Novocherkassk, Russia. Right: Xiongnu horse ornament (c. 1st century CE) from the Gol Mod burial site, Mongolia.

Steppe peoples were hardly the only ones who knew how to inlay gemstones into gold. Plenty of other cultures did it, too. What set Inner Eurasian cloisonné apart was the sheer complexity of its gemstone arrangements, rarely seen on the continent since the Bronze Age collapse. Many of these pieces were crafted in the shape of animals like horses, stags or leopards; others took more abstract, flowing shapes that evoked animal parts like horns or wings, symbolically calling upon their strengths on the wearer's behalf.

Since the most ancient times, the Greeks and Romans had heard of the Scythians, a nomadic Iranian people from the plains north of the Black Sea (think modern-day Ukraine), famed for their wealth and skills on horseback. In the late 1st century CE, some of these steppe Iranians (variously known to the Romans as the Sarmatians, Roxolani, Aorsi, Iazyges or Alans) started to make their way further west, to the Roman Empire's border on the Danube River. Their hierarchies of kings and nobles met the local Germanic peoples' egalitarian tribes; their polychrome craft met the flowing patterns on the natives' gold and silver.

Though the steppe Iranians fought many border wars against the Romans, there were many years of peace and quiet, too. The Romans paid good money for the nomads' craft through the Black Sea trade, and their skill on horseback made them highly sought after as elite soldiers. Some of them rose to very high ranks in the empire.

Then everything changed when the Hunnic Empire attacked.

Left: Scythian earring (c. 1st-2nd century CE) from Ust-Alma necropolis, Crimea. Objects from this trove were originally displayed at the Simferopol Museum; after the Crimean Peninsula was annexed by Russia in 2014, the Ukrainian government managed to successfully sue for their return from a Dutch museum they were on loan to. Right: White Hunnic dragon-shaped collar (5th century) from Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan

The Huns were a powerful steppe empire, heirs to an old, long-fallen empire far to the east. They were made up of many tribes, rearranged into ranked military units and commanded by nobles who swore their oaths personally to one of their two kings: one in the east, one in the west.

In a few short decades of the 4th century CE, the Huns conquered a vast swathe of land, from north of the Caucasus to the very borders of the Roman Empire on the Danube. The proudly independent Germanic peoples of Central Europe, whom the Romans couldn't quite conquer, now faced two choices.

They could submit to the Huns, pay them expensive tributes and be absorbed into their army, like countless nations before them. Or they could cross the river, into Roman land, and ask for sanctuary from the other empire.

Whichever way they went, the Germanic peoples — Goths, Vandals, Suebians, Langobards, Thuringians — were by now a transformed people. Centuries of trade and elite intermarriage with the Black Sea nomads had steeped them in the culture of the steppe: the strict ranks of kingship and nobility, the ways of the horse and the bow, the cult of mystical swords.

Now Hunnic rule would firmly imprint all those things onto their cultural fabric, along with one more thing: the art of the steppe.

Left: Hunnic noblewoman's diadem (5th century CE) from Kerch, Crimea. Right: Horse harness buckles (5th century CE) from the tomb of Ardaric in Apahida, Romania. Ardaric is traditionally believed to be a king of the Gepid people and a vassal of the Huns, but recent historians have suggested that he might've been a Hunnic prince himself.

In older histories of the Migration Period, you might see this style of cloisonné called by various European terms, like maybe "Visigothic" or "Aquitainian". These names belie the style's Asian roots. By the end of the 4th century, a uniform style of jewellery stretched from the Hungarian Plains to the Caucasus, practiced by the artisans living under Hunnic rule.

For a few decades, the Romans and the Huns sized each other up across the frontier. But in time, the Huns pacified their borders. The flight of Germanic peoples into Roman lands slowed down, and the old cross-border trade routes lurched back into life.

Sometimes the Romans would ask the Huns to break the kneecaps of "barbarian" bands roaming the borderlands (whom the Huns gladly hunted down as "fugitives"), and paid them off with tributes of gold and precious stones, which were turned into colourful jewellery for Hunnic rulers to reward their vassals with.

Which brings us to the proverbial elephant in the room! These splendid works of art mostly belonged to the royals and aristocrats at the top of society. If you were an average peasant living under Roman rule — or a herder living under Hunnic rule — you might see these things displayed at houses of worship and religious rituals, you might even wear one to really big occasions like weddings, whether borrowed or as a family heirloom.

But it would've been a small upper-class who owned these things in droves (enough that their families buried them with their jewels when they died). In some cases, the nobility would even enact strict sumptuary laws to control what kinds of ornaments each social class was allowed to wear. Even though it would've been the commoner's hands that dug out the stones from deep, dark tunnels. Their hands that farmed and herded to pay the elites taxes; maybe their arms that seized gold or exacted it as tribute in the wars they were levied to fight.

And lest you think we left all this behind in the "Dark Ages": the global jewel industry today is still deeply tied with armed conflict and labour abuse. That slab of lapis you saw on CrystalTok? Probably smuggled out of war-torn Afghanistan. Gold rings and bracelets? Could well have come from mines run by warlords in the Sahel.

Not all precious stones and metals are mined at gunpoint, obviously — there are plenty of people in the industry who are proud of what they do and are compensated well for it, now just as then. The passion and skill that went into crafting these incredible works of art were 100% real.

But I think it's important to remember the equally real systems of violence that ensured that so much of them flow so easily and cheaply to the end user. Jewellery, like all other displays of surplus wealth, has a long trail of bloodshed and oppression surrounding it.

Left: Ostrogothic noblewoman's eagle-shaped brooch in the Hunnic style (5th century CE), Domagnano, Italy. Right: Illustration of Danubian (Hunnic) grave goods from the tomb of Frankish king Childeric I (5th century CE), stolen from the National Library of France in 1831. Both the Ostrogothic and Frankish peoples were vassals of the Hunnic Empire.

In 453, Attila, the supreme ruler of the Huns, died suddenly at a feast. Throughout his two decades of rule, Attila had brought his empire into open war with the Romans; inflicted mortal wounds on the Western Empire; brought the Eastern Empire to its knees.

But his reign also laid on unstable foundations. Attila had installed himself as sole dictator by murdering his brother who ruled over the eastern plains and moving the core of his empire west, to the Hungarian Plains. With the king gone, his heirs and vassals quickly lapsed into civil wars as they sought to claim his empire for themselves — in full or in part.

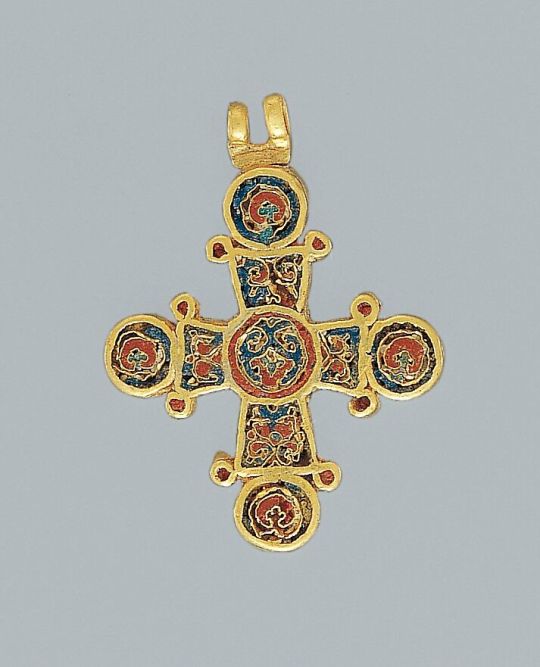

Flash-forward to a century later, around the time the time Byzantine earrings in the OP were made. Europe, by this time, was a very different place. The Western Roman Empire was gone. A smattering of kingdoms stood in its place, ruled by the military elites of migrating Germanic peoples who'd come to an accommodation with the local Roman senatorial elites and church clergy.

For a few short decades, at least, the new kingdoms of Europe traded with the Eastern Empire in peace. That wouldn't last forever (thanks, Justinian); but it was enough time for the steppe-derived style of cloisonné jewellery to permeate Byzantine fashion, adding onto the earlier Germanic and Alan influences.

Left: Enamelled cross. Right: Medallion of St John the Baptist. Both from Constantinople, c. 1100 CE.

So while the northern Germanic kingdoms (like the Carolingian Franks and the Anglo-Saxons) took the craft to the far corners of the continent, the Byzantines worked on combining it with familiar Greco-Roman techniques. Byzantine cloisonné would be marked by fine carved reliefs along the gold's surface, and also textures made by chasing and repoussé.

Throughout the next few centuries, Byzantine artists revived a couple of ancient Egyptian practices. The first was the use of thin gold wires, which they used to create complex (often religious) images.

The second was a Roman specialty: glass! Precious stones like garnet and turquoise are eye-catching, sure. But they cost a lot to mine, a lot more to cut and polish, and there are only so many ways you can work with them. So Byzantine jewellers started pouring coloured glass powder into spaces in the design, and then heating it until it fuses into enamel.

This enamelling technique, combined with thin wires, enabled much more complex designs than were traditionally possible with precious stones. But it wasn't 100% foolproof! The fusing temperature of silicate glass can be quite close to the melting temperature of gold alloys (and doubly so for silver and copper-based alloys), meaning it took a lot of care to fire the powder into translucent glass without damaging the rest of the piece.

So yeah: we might be used to thinking of "Europe" and "Asia" as two separate worlds. But the past was a lot more interconnected than it might appear; even some of the art we associate with "Medieval Europe" have deep roots in the Central Asian steppes. And I think that if we look closely at the world around us, we'd all be surprised by how many markers of wealth and style had roots in equally unlikely places.

References:

Zhixin Sun, James C. Wyatt and Emma C. Bunker, Nomadic Art of the Eastern Eurasian Steppes (2002)

Hyun Jin Kim, The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe (2013)

Nicola Di Cosmo, Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity (2018)

A pair of gold earrings with garnet, pearl, and chalcedony elements, Byzantine, 6th century AD

from Hindman Auctions

#cloisonné#jewellery#polychrome#history#late antiquity#early medieval#migration period#central asia#eastern europe#attila the hun#scythians#sarmatians#byzantine empire#goths#franks#merovingian#inlay#gems#garnet#turquoise#gold#enamel#historical aesthetic#fashion history#mesoamerican turquoise mosaics kinda had the same energy#but they're way out of my ballpark#steppe nomads: closer than they might appear in your history textbooks

1K notes

·

View notes