#willie mae thornton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Willie Mae "Big Mama" Thornton was born December 11, 1926 and died July 25, 1984 at the age of 57

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kaiser George Marionettes. https://www.facebook.com/KGMMarionettes/ https://www.etsy.com/uk/listing/1226985279/rock-n-roll-stand-ups-kgm-marionettes

#marionettes#puppets#rock and roll#rolling stones#chuck berry#john lydon#little richard#howlin' wolf#kaiser george#KGM#artist#sculpture#willie mae thornton#etta james#buddy holly

1 note

·

View note

Text

Women in Rock Deserve More Than 1 Day

Jan. 3 has been declared – by who we don’t know – Women Rock! Day, because on that day in 1987, Aretha Franklin became the first woman inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame – nice, I guess, but hardly a highlight of her career. We’d suggest changing the date to June 3, the day in 1967 that Franklin’s “Respect” hit No. 1 on Billboard’s singles chart. But that’s just us. Also, Jan. 3 is less…

View On WordPress

#1950s#Bowie#Elvis#Elvis Presley#heartbreak hotel#Hound Dog#mae boren axton#marion keisker#rock and roll#willie mae thornton#women rock day

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why are women never the " mothers " of invention .

Like this is an overgeneralidation but men are always " fathers of modern medicine " or creators but women are almost always only called the " mother " of a field or invention when there's also a " father " . A lot of the time even if they litterally created something the men who came after them are still referred to as the " father "

Not to mention the implication of the semantics behind mother and father are completely different due to centuries of stereotyping and sexist systematic bias. Like we think of the " father " of fields or invention as being in control and as a smart capable genius whilst " mothers " are portrayed as nurturing slightly whimsical and barley forward thinking women in modern media .Grandmother also discredits women seeing as unfortunately western culture has created a narrative that elderly women are helpless , cruel or crazy

Like Mary shelly CREATED the sci fi genre but is never referred to as the mother of sci fi but we say H.G Wells fathered sci fi . We are told that Elvis is not only the father of rock and roll and modern music but the king of it - ignoring the fact he stole his songs from Willie Mae Thorton .

#funny#shitpost#vent post#feminisim#just girly things#intersectional feminism#womens rights#beautiful women#mary shelley#big mama thornton#willie mae thorton#elvis presley#elvis#elvis the king#elvis history#hound dog#rock#rock and roll#music#sci fi#frankenstein#h.g. wells

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baron Wolman Willie Mae Big Mama Thornton, San Francisco 1968

“My singing comes from my experience…my own experience. I never had no one teach me nothin’. I never went to school for music or nothin’. I taught myself to sing and to blow harmonica and even to play drums by watchin’ other people! I can’t read music, but I know what I’m singing! I don’t sing like nobody but myself.” Big Mama Thornton

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

On August 13, 1952, four years before Elvis Presley would make “Hound Dog” his longest running no. 1 hit, the song was recorded for the very first time by Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton. #OnThisDay

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's talk about Hound Dog

With the upcoming release of the movie Priscilla, it seems that there are tons of trolls out and about on Tumblr trying to inundate the #Elvis tag with lies and misinformation about Elvis.

Like, for one, that he stole music from black recording artists. One of the most pervasive--and incorrect--rumors specifically revolves around the song "Hound Dog."

People say that Elvis stole the song from Big Mama Thornton, a talented (and black) rhythm and blues singer/songwriter.

But what if I told you that "Hound Dog" was written by two Jewish guys?

And that Elvis' rendition was not based on Big Mama Thornton's 1952 version, but rather on Freddie Bell & the Bellboys 1955 version?

First, let's talk about how the song came to be in the first place.

In 1952, bandleader Johnny Otis introduced Willie Mae "Big Mama" Thornton to songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who were inspired by her powerful and gritty blues style to write the song. Characterized by its bold lyrics and Thornton’s robust delivery, the song told the story of a woman dismissing a useless man from her life, with the iconic opening line serving as a euphemism for a man who is a burden rather than a benefit ("You ain't nothing but a hound dog/Been snoopin' 'round my door/You can wag your tail/But I ain't gon' feed you no more").

The writing process was influenced by both Thornton's imposing physical presence and vocal style and sought to capture her fierce and unapologetic personality without using explicit language.

And quite frankly, the song is kick ass. Have a listen here:

youtube

It was written for a woman to vocally chastise her selfish and exploitative man, making use of metaphor and sexual double entendre common in the bawdy genre, and effectively embodied Willie Mae "Big Mama" Thornton's robust and unapologetic persona.

In a stroke of genius, Leiber and Stoller crafted the iconic piece in just 12 to 15 minutes, with Leiber jotting down the lyrics spontaneously during a car ride. The process involved a challenging rhyme scheme and a complex metric structure of the music. In addition to the original version, they also created an alternate version titled "Tom Cat," adding diversity to Thornton's musical repertoire.

Thornton’s rendition of "Hound Dog" played a pivotal role in transitioning black R&B into rock music and symbolized the blending of racial lines in music ahead of legal desegregation in public schools. Initially, Thornton performed the song as a ballad, but Leiber and Stoller, who held her version as their favorite, guided her to the more rhythmic and edgy style that became iconic. New York University music professor Maureen Mahon highlights the significance of Thornton's version as "an important [part of the] beginning of rock-and-roll, especially in its use of the guitar as the key instrument."

Many assert that Elvis was the first to cover her song, but that is untrue. By the end of 1953, at least six "answer songs" that responded to 'Big Mama' Thornton's original version were released. According to Peacock Records' Don Robey (who, it would come to be known, defrauded Leiber, Stoller, and Big Mama Thornton out of money for "Hound Dog"), these songs were "bastardizations" of the original and reduced its sales potential.

By 1955, enter Freddie Bell and the Bellboys.

In 1955, Bernie Lowe of Teen Records believed "Hound Dog" could have a broader appeal and commissioned Freddie Bell of Freddie Bell and the Bellboys to rewrite and sanitize the song for mainstream audiences.

Jerry Leiber found these alterations irritating, criticizing the new lyrics for making "no sense", even though the modified version became a regular feature in Bell and the Bellboys’ Las Vegas act.

You can listen to their version here. Sound familiar?

youtube

Finally, we come to Elvis.

In 1956, Presley and his band first heard "Hound Dog" while they were in Las Vegas, where they were booked to perform at the Venus Room of the New Frontier Hotel and Casino. During their stay from April 23 to May 6 of that year, they encountered the song at the Sands Casino, where Freddie Bell and the Bellboys were performing their sanitized version of the tune, having transformed it from a racy song about a disappointing lover into a song literally about a dog.

Elvis Presley was instantly captivated by the song. Its catchy melody and lyrics had him returning to the performance multiple times to grasp its chords and lyrics fully. Scotty Moore, Presley's guitarist, and D.J. Fontana, his drummer, corroborated that Elvis was heavily influenced by the Bellboys’ version of the song. Presley, although acquainted with Big Mama Thornton's original bluesy version, was more drawn to the Bellboys' rock and roll, more comedic rendition.

Soon after, Presley introduced "Hound Dog" to his own live performances, first showcasing it at the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas. Initially, his execution of the song bore a more measured pace and almost burlesque feel, influenced directly by the Bellboys’ comical, Las Vegas-style performance.

At around 1:30 in the video below, you can see and hear the slowed-down version as Elvis might have performed it in Las Vegas.

youtube

It was not long before the song became a staple in Presley’s performances, and a twangy guitar and a hard-driving rock and roll beat were added, making its debut as the closing number at the Ellis Auditorium in Memphis on May 15, 1956. The audience of 7,000 at the Memphis Cotton Festival witnessed the inception of what would become a classic element in Presley’s shows, enduring for a time as his standard closer.

Elvis Presley’s version of "Hound Dog" is not considered a direct lift of Thornton’s original, but rather an adaptation of a song that had not reached the status of a "standard" in the music industry. Presley encountered the song through the Bellboys’ version, which was itself one of a number of covers of the original. Furthermore, respected music analysts and critics, including George Plasketes and Michael Coyle, emphasize that most of the audience in Presley's era were not familiar with Thornton's 1953 original recording, and thus, Presley's version cannot be perceived as a theft or usurpation.

Moreover, it is essential to highlight that Presley held a deep respect for Thornton’s original version and even had a copy in his personal record collection, indicating an acknowledgment of the song's origins.

Presley's rendition of "Hound Dog," influential as it became, was part of the broader practice of artists adapting and interpreting songs to suit different styles and audiences. Presley's had often recounted his admiration for other renditions and related songs--and often rebuked the notion that he was the King of Rock and Roll, instead preferring to refer to Fats Domino with the title.

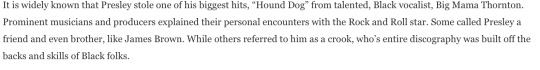

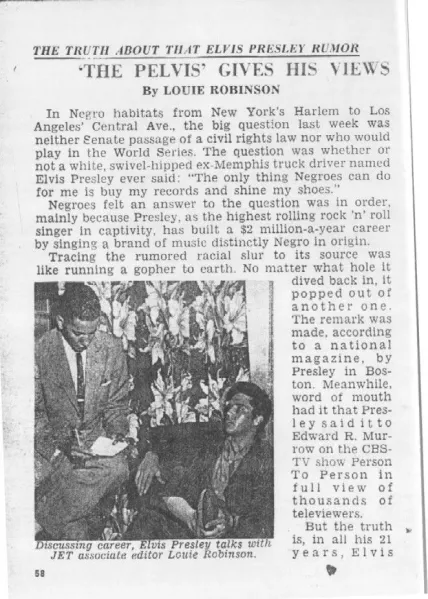

Contrary to persistent stereotypes suggesting Elvis Presley claimed sole credit for the rise of rock and roll, the singer himself acknowledged the black community’s paramount contribution to the genre. In a 1957 interview with Jet magazine, Presley openly dismissed the notion of being the originator of the genre.

In the interview, he expressed his admiration for black musicians, conceding that his own renditions could not match the authenticity and soul of artists like Fats Domino. Elvis cited his childhood experiences attending black churches, such as Rev. Brewster’s church in Memphis, as instrumental in fostering his love for the music that would later define his career. Through such statements, Elvis sought to underscore the black community's foundational role in shaping rock and roll.

His open admiration for and familiarity with black music and black artists proved that his interpretation of "Hound Dog" was not an act of appropriation, but rather a contribution to the evolving landscape of rock and roll.

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday to the late Willie Mae Thornton (December 11, 1926 – July 25, 1984), better known as Big Mama Thornton, was an American singer and songwriter of the blues and R&B genres. She was the first to record Leiber and Stoller's "Hound Dog", in 1952, which became her biggest hit, staying seven weeks at number one on the Billboard R&B chart in 1953 and selling almost two million copies. Thornton's other recordings included the original version of "Ball and Chain", which she wrote.🎂

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just Dance Name Headcanons #1

Explanations:

Jerome: This was based on a concept I had for Jerome by Lizzo, where it would be the Georgia that the song was talking about, talking about him this time.

Kelly: Idk, she looks like a Kelly.

Percy and Wilhelmina: I wanted old-Timey names, and the cover artist is dubbed Charles Percy, and since Charles is taken I went with Percy. For the girl, I just like the name Wilhelmina, as well as these two coaches being the main coaches for my Hound Dog mashup, and Big Mama Thornton’s real name is Willie Mae Thornton.

Lucille: She gives the vibe of an old sitcom protagonist, so I named her after Lucille Ball from I Love Lucy.

Obama Kennedy: The band’s name is The Presidents Of The United States Of America, so I wanted to name her after a president. I did a poll in a discord server I’m in, and Kennedy won by a landslide (of course inspired by JFK).

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

"(and take a guess at who destroyed the professional affinity they built with him" is this the colonel? jfc I keep hating that man

who else? leiber and stoller initially didn't know who elvis was and had some preconceived judgment in place (which happened to him a lot), but then once they actually met with him, they were impressed and developed a rapport. elvis wanted them to be in the studio when he recorded. they had suggestions and encouragement for him, about songs, about his career, and parker didn't like that, was threatened by the idea of them getting in the middle, or worse, giving him ideas (this would repeat throughout his life, it's not dissimilar to what happened with steve binder). the colonel eventually destroyed the relationship they built by sending leiber and stoller a blank page and calling it a contract as an intentional slight. they told him exactly what they thought of that, and never worked with elvis again.

longer details from here

"Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller were like the rap artists of the early '50s, pushing buttons, inviting scorn and testing the limits, as rock roared into being from its roots as blues and rhythm and blues. They were writing music for black artists, when one of their songs, Hound Dog, was heard by a young Elvis Presley. His adaptation turned it into a No. 1 hit and helped aim Leiber and Stoller toward the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

They wrote 20 songs for Elvis until the brash young songwriters had a falling out with Colonel Tom Parker, the Svengali they now remember as a 'bully' and a 'foul, greedy' man who helped destroy Elvis. But the estrangement didn't change their respect for Elvis.

'We feel that Elvis Presley was the high water mark of the 20th Century. He's legend. No, he's myth. He's in that celestial place for mythological figures. At the time, we just thought he was a white kid trying to make it as a singer', says Leiber, the man who supplied the words as lyricist of one of the worlds' best-known songwriting duos.

Leiber and Stoller originally met in 1950, sharing a love of the blues and boogie woogie. They were writing for black artists, their earliest songs recorded by Jimmy Witherspoon, Little Esther, Amos Milburn, Charles Brown, Little Willie Littlefield and, among others, Willie Mae 'Big Mama' Thornton.

It was for Big Mama Thornton that they wrote Hound Dog in 1952. Her version came out in 1953 and was adapted by several groups. Stoller had gone to Europe with royalties from some of those early songs and was on his way home aboard the Andrea Doria when it sank in 1956.

Rescued by a lifeboat, Stoller arrived in New York with Leiber yelling from the dock: 'We've got a smash hit'. 'I said, 'You mean Big Mama Thornton's record?' He said, 'No, some white kid named Elvis Presley'. Elvis had heard Hound Dog in a Vegas Lounge by a group called Freddie Bell and the Bellboys', says Stoller.

Elvis' recording of Hound Dog was released in July of 1956 and bounded up the charts, selling millions of copies. Released the same year as Heartbreak Hotel, it put Elvis on TV and turned him into a phenomenon.

After Elvis' great success with his version of Hound Dog, Paramount Studios and music publishers Hill and Range selected additional Leiber and Stoller songs for Elvis' 1957 film Loving You. It was on April 30, 1957 while working on the movie Jailhouse Rock that Elvis first met Leiber and Stoller. They were skeptical of meeting the newcomer, thinking he was a country bumpkin. However, they were very impressed when upon meeting and talking to Elvis that he was very knowledgeable of R&B music and could discuss its nuances in great detail. They went on to work closely with Elvis on the Jailhouse Rock soundtrack with Stoller appearing in the film playing the piano for Elvis' character. After an incident of pitching songs and movie ideas directly to Elvis and not going through the usual chain of command with Elvis' manager, Colonel Tom Parker, they had a falling out with Parker and essentially ended their collaboration with Elvis. Fast-forward to 1960, they did write a couple of songs that were in the running for inclusion in Elvis' first post-army movie, G.I. Blues, but, ultimately they were not used. Although the direct collaboration ended, Elvis did choose several additional Leiber and Stoller tunes to record over the years.

'We were completely unconscious of what it might imply. We were just doing numbers', says Leiber. Stoller says those numbers were unfamiliar to white audiences because he and Leiber had written 'almost exclusively for black performers, so we wrote in a black idiom. People started thinking it was entirely new, but the base we started from was the blues and boogie woogie'.

Stoller says they didn't specifically tailor songs to that early Elvis persona but began by supplying songs they had already written, like Love Me, a ballad they had already recorded. 'Then we were asked to write for a movie, Loving You, with Elvis and Lizabeth Scott'. The next project, Jailhouse Rock, included four songs Leiber and Stoller wrote while held captive in a New York hotel.

They had been living in Los Angeles, and Stoller says they rented a New York hotel suite with a piano in the living area. 'We were given a script for the movie and kind of tossed it in the corner. We were having a ball in New York, going to jazz clubs, cabaret, going to the theater and hanging out. Finally, Jean Aberbach who ran Elvis Presley Music knocked on the door and said, 'Well boys, where are my songs?' I think Jerry said, 'Oh, Jean, you're going to get them'. Jean then pushed a big overstuffed chair in front of the door and said, 'I'm not leaving until I get my songs'.

They wrote four songs in five hours, including Jailhouse Rock, the movie's title song and Treat Me Nice, both major hits.

After that, Elvis 'wanted us in the studio with him whenever we recorded', says Stoller. It was part of Elvis' 'perfectionist' tendencies in the early stages of his career, says Jerry Schilling, a member of Elvis' Memphis Mafia. Leiber says Elvis 'was like an Olympic champion. He could do 40 to 50 takes. I never saw him happier than when he was on a microphone, performing'.

Both songwriters say that studio time was their primary contact with Elvis, who was kept at arm's length from them by Colonel Parker. Stoller says Elvis once asked, 'Mike, could you write me a real pretty ballad?' Over the weekend, they wrote the song Don't for him and handed it to him only to be berated by Parker.

'He was upset that I handed a song directly to Elvis. They didn't want anybody to have direct access to Elvis. It was like Elvis was kept kind of in a glass box and away from contact except for the Memphis Mafia. They were like paid companions'.

Like almost everyone else, they also had little contact with Parker himself. 'The longest I ever spent with him was a dinner at the Beverly Hills Hotel around 1956, after Hound Dog', says Stoller.

The breaking point for them came when Leiber was recovering from a bout with pneumonia about two years later, and Parker ordered them to California to write songs for a new movie project. Leiber explained that he had just been released from the hospital and was unable to travel. 'Parker said, 'You'd better get your ass out here'. He then sent a packet with a contract for them to sign. Leiber says he pulled the contract from the packet and found only a dark line across the middle of a blank page for his signature.

'I called and said, 'I think you made a mistake. There's no contract in here'. He said, 'Don't worry about that, boy. Just sign your name, and I'll fill it in later'."

"Jerry Leiber: I called and asked to speak to (Colonel) Tom. He got on the phone and said (Leiber imitates Parker) 'How you doin' boy?' I said, 'I'm OK. I had a real close call there. I had walking pneumonia and I just got out of the hospital.' He said he wanted me to pack right away and catch a plane. I told him I wasn't in any shape to catch a plane because I'd just gotten out of the hospital. He said, 'If they let you out, that means you're all right'. I told him I needed a day or two to get myself together, but he said the schedule was very tight and he needed me to come out right away.

Then he said, 'Did you see the contract yet?' I said, contract?' He said, 'I'm sure it's there by now. It's a contract covering the forthcoming movie and soundtrack album. You better take a look, sign it and send it back. So I hung up, took the contract out of one of the manila envelopes, and saw nothing but a blank page. Nothing was written on it except two lines at the bottom where Mike and I were supposed to sign our names.

I thought they had made a ridiculous blunder. I called Parker's secretary and said, 'There's been a mistake', she said, 'Let me get Tom.' Colonel Parker got on the phone and I told him, 'There's a piece of paper here with two places for signatures, but the contract is missing'. He said, 'There's no mistake - just sign it'. Then he said, 'Don't worry. We'll fill it in later'.

I got off the phone with Parker and immediately called Mike. I told him, 'Breaking up with the Presley outfit is like throwing away a license to print money. After all this work, I really hate to do it, but I am really offended' (When I was on the phone with Parker, I almost told him that I wasn't one of his 'okie dokies'). I told Mike I didn't want to work with this jerk anymore.

I asked Mike, 'How do you feel about this?' Now Mike is a very measured and modest with very good manners. He paused for a moment, and then he said, Jer ....tell him to f**k himself!'

So I called Colonel Parker back and said, 'Tom, I thought about what you told me'. He said, 'Good! What time are you gonna get here?' I said, 'Tom, I spoke to Mike about the contract, and he told me to tell you to go f**k yourself'.

I hung up, and I never spoke to him again."

"Like many others, [Leiber] wondered about Parker's hold on Elvis. 'I think he (Elvis) had a very weak father and didn't get a sense of what a father was like. Parker came along, and his attitude was, 'Do this, do that, and I'll take care of everything'. Parker became his surrogate family'."

"Leiber: Of course, the Colonel wasn't really a colonel. He was Thomas A. Parker, whose former job as a carnival barker defined his personality. He had a definite shtick ('Pick a number from one to ten'). He told dozens of canned jokes. I can't remember any of them except that they weren't funny. But it didn't matter that we didn't laugh, because the Colonel wasn't really conscious of us. Of course, he knew we were the songwriters of 'Hound Dog' and the new songs for Jailhouse Rock. He knew more hit songs for Elvis meant more money for him. Beyond that, though, he was more interested in putting on his own show than getting to know us.

He had his long cigar and his confected Southern accent. He was a nonstop talker whose ego was always on parade. He told us in great detail all he had done for Elvis - and all he intended to do.

'Elvis' he said, 'is going to be bigger than the president, bigger than the pope'.

Naturally we agreed.

Stoller: The Colonel had the kind of energy that sucked all the air out of the room, even the dining room at the Beverly Hills Hotel. I had little interest in the man. Elvis was the guy we were eager to meet.

The session was due to start later that week.

Leiber: My heterosexual credits have long been established, so I can comfortably say that the first thing that hit me when I walked into the recording studio and found myself standing next to Elvis Presley was his physical beauty. Far more than his pictures, his actual presence was riveting.

He had a shy smile and quiet manner that were disarming."

"Stoller: It's important to remember that on the day we met Elvis, he was twenty-two and we were twenty-four. We were contemporaries. Remember, too, that Jerry and I shared the uppity view that he and I were among the few white guys who knew about the blues.

In the first five minutes of conversation with Elvis, we learned we were dead wrong.

Elvis knew the blues. He was a Ray Charles fanatic and even knew that Ray had sung our song 'The Snow Is Falling'. In fact, he knew virtually all of our songs. There wasn't any R&B he didn't know. He could quote from Arthur 'Big Boy' Crudup, B.B. King, and Big Bill Broonzy.

Leiber: When it came to the blues, Elvis knew his stuff. He may not have been conversant about politics or world history, but his blues knowledge was almost encyclopedic. Mike and I were blown away. In fact, the conversation got so enthusiastic that Mike and Elvis sat down at the piano and started playing four-handed blues. He definitely felt our passion for the real roots material and shared that passion with all his heart.

Just like that, we fell in love with the guy."

"'Whenever I record' he said, 'I want you guys in the studio. You're the guys who make the magic'."

"When Elvis returned (after a studio break), his head was down and his demeanor totally changed.

'I'm really sorry, Mike', he said, 'but you're gonna have to leave. The Colonel came in and he doesn't want anyone here but me and the guys'. 'Okay' I said, not wanting to make any more trouble. And with that, I left. The next day at the shoot I mentioned the incident to one of Elvis' Memphis buddies. 'Don't take it personally, Mike,' he said, 'It's just that the Colonel doesn't want Elvis to develop a friendship with anyone but us'."

#elvis presley#leiber and stoller#i could really yell here because it makes me so upset and angry but#i was reading something with sheree north who liked him so much and wanted to help him and she referred to the mm as “the goons”#they did what they were instructed to do under the auspices of it being somehow better for elvis but it wasn't#he wasn't some thing to be managed he was a human being and an artist with aspirations#it just breaks my heart how that was thwarted or suppressed or exploited over and over again#anyway shout out to elvis australia they do so much and have such informative pages <3#this was one of the earliest stories i read when i started digging into the foundation of his career#anonymous#letterbox#total aside but the number of guys who go “i'm totally straight but he was breathtaking” is endless and always makes me giggle#sorry the formatting on this is awful i did it on mobile somewhat unsuccessfully#i was a dreamer

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎶 𝗩𝗼𝗶𝘅 𝗲́𝗰𝗹𝗶𝗽𝘀𝗲́𝗲𝘀 - 𝗔̀ 𝗹𝗮 𝗿𝗲𝗻𝗰𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗿𝗲 𝗱𝗲𝘀 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗶𝗰𝗶𝗲𝗻𝗻𝗲𝘀 𝗺𝗲́𝗰𝗼𝗻𝗻𝘂𝗲𝘀 𝗱𝗲 𝗹'𝗵𝗶𝘀𝘁𝗼𝗶𝗿𝗲 🎵

🎤 𝗔𝘂𝗷𝗼𝘂𝗿𝗱’𝗵𝘂𝗶 : 𝗕𝗶𝗴 𝗠𝗮𝗺𝗮 𝗧𝗵𝗼𝗿𝗻𝘁𝗼𝗻 (𝟭𝟵𝟮𝟲-𝟭𝟵𝟴𝟰) 🎸

Dans l'Amérique du milieu du XXe siècle, tourmentée par les tumultes de la bataille ardente pour les droits civiques, s'élève une voix, puissante et inébranlable, celle de Willie Mae Thornton, plus connue sous le nom de Big Mama Thornton. Chanteuse de blues et de rythme and blues, elle se fait l'écho des douleurs et des aspirations d’une génération toute entière. Née en 1926 en Alabama, terre encore marquée par les ombres de la ségrégation, Big Mama Thornton puise dans la douleur de son temps les matériaux pour forger une mélodie qui se veut à la fois cri de rébellion et chant de liberté. Sa voix, rauque et vigoureuse, se fait porteuse des cicatrices de l’oppression et des rêves d'un avenir meilleur. En 1952, elle enregistre « Hound Dog », un titre qui va marquer à jamais l'histoire de la musique et ouvrir la voie au rock 'n' roll. Sa version, emplie de puissance et d’authenticité, sera, hélas, malheureusement éclipsée par celle, plus tardive et plus médiatisée, d'Elvis Presley. Toutefois, réduire Big Mama Thornton à ce seul morceau serait une hérésie. Elle est avant tout une précurseuse, une combattante, une artiste. Big Mama est la voix incarnée de l'Amérique Noire, l'expression musicale de la résilience et de la persévérance. Bien qu’elle ait quitté ce monde en 1984, son héritage perdure, tel un astre éternel dans l’immensité du firmament.

🔗 Pour en savoir plus : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Mama_Thornton 🎧 Écouter : https://youtu.be/2Pl2Bo9c88M?si=tFxeEOTjK4efd-We

#BigMamaThornton#Blues#RhythmAndBlues#HoundDog#MusiqueAméricaine#Légende#Pionnière#Résilience#HéritageMusical

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

if i say “fast car” and you think of luke combs and not tracy chapman i hate you and i’m not sorry about it

Nothing against Luke combs but this is giving Elvis Presley covering hound dog and everyone forgotten about who originally sung it which was Willie Mae Thornton better known for her stage name Big Mama Thornton and I don’t like it.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Singer/songwriter/blues legend Willie Mae ‘Big Mama’ Thornton

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

The blues music that Elvis and a lot of other rock and rollers pulled from was created and performed by Black artists who were relegated to a genre that was known as, “Race Music.” In the early part of the 20th century, this was how the powers that be classified Black music that was deemed unsuitable to be played on mostly white, mainstream radio. These black artists never got the chance to be heard by larger audiences and earn the kind of money that the white artists who copied them did.The famed singer was a "consumer culture guy" influenced by his time in Black spaces, says "Race, Rock and Elvis" author and Tennessee State University professor Michael T. Bertrand.

As a young man, "he was still basically going into the studio and recording stuff he had heard either recently or he remembered from when he was a kid," Bertrand says. Luhrmann's "Elvis" is perhaps the most high-profile examination of the Mississippi-born musician's Black influences and the controversy surrounding his popularization of songs originally sung by Black artists. "There is no doubt that (Elvis) benefited tremendously materially from performing music that was associated with African Americans," Bertrand says. Even in conversations with people who understand the complexity of that association, the Black artists who originally sang Presley's signature songs are rarely name-checked. Thornton, widely acknowledged as the vocal architect of "Hound Dog," made the song a hit, only for it to be eclipsed by Elvis' cover.

Presley's wealth accumulation for "Hound Dog"( original singer was willie mae " big mama "thorton ) in comparison to Thornton was a topic she frequently touched on at concerts, according to Michael Spörke's biography "Big Mama Thornton: The Life and Music." Jet Magazine's 1984 obituary recalls her once saying, "That song sold over two million records. I got one check for 500 dollars and never saw another." The "Elvis" soundtrack pointedly features top Black artists like Doja Cat, who remixes "Hound Dog" in the song "Vegas" using Thornton's original vocals. On another track ("The King and I").

exactly

i remember ppl saying how doja’s song Vegas was kind of a pick at elvis for this, using the original singer in that song and the specific usage of “his” lyrics:“you aint nothing but a hound dog you aint the man you aint fhe man” and the whole song in itself lol and how the video clip is all black people. everything combined

1 note

·

View note