#wallace henry thurman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

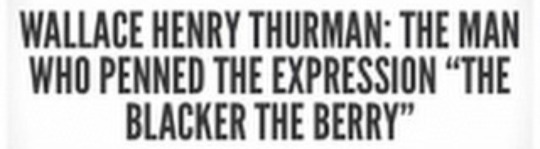

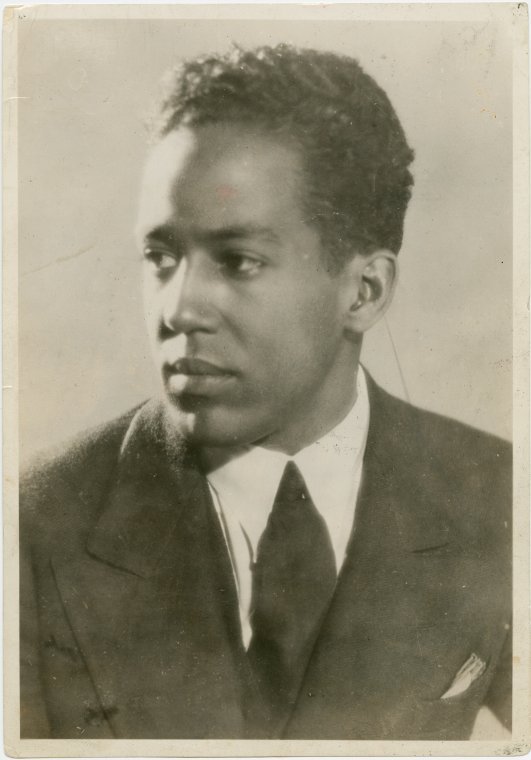

Wallace Henry Thurman (August 16, 1902 – December 22, 1934) was a novelist active during the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote essays, worked as an editor, and was a publisher of short-lived newspapers and literary journals. He was known for his novel The Blacker the Berry: A Novel of Negro Life.

He began grade school at age six in Boise, but his poor health led to a two-year absence from school, during which he returned to his grandmother in Salt Lake City. He lived in Chicago (1910-14). He finished grammar school in Omaha. He suffered from persistent heart attacks. While living in Pasadena, he caught influenza during the worldwide Influenza Pandemic. He recovered and returned to Salt Lake City, where he finished high school.

He was a voracious reader. He enjoyed the works of Plato, Aristotle, Shakespeare, Havelock Ellis, Flaubert, Charles Baudelaire, and many others. He wrote his first novel at the age of 10. He attended the University of Utah as a pre-medical student. He transferred to USC but left without earning a degree.

He met and befriended the writer Arna Bontemps, and became a reporter and columnist for an African American-owned newspaper. He started a magazine, Outlet.

He moved to Harlem. He worked as a ghostwriter, publisher, and editor, as well as writing novels, plays, and articles. He became the editor of The Messenger, a socialist journal addressed to African Americans. There he was the first to publish the adult-themed stories of Langston Hughes. He left the journal to become the editor of World Tomorrow. He collaborated in founding the literary magazine Fire!!. Among its contributors were Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Bruce Nugent, Aaron Douglas, and Gwendolyn B. Bennett.

He was asked to edit a magazine called Harlem: A Forum of Negro Life; its contributors included Alain Locke, George Schuyler, and Alice Dunbar-Nelson. He became a reader for a major New York publishing company, the first African American to work in such a position.

He wrote a play, Harlem, which debuted on Broadway.

He published Infants of the Spring. He co-authored his final novel, The Interne. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My Book Review

The Big Sea is an intimate, sweeping (travel) memoir that engulfs you into the world, thoughts, revelations, and life of Langston Hughes as he comes of age in his 20s in the 1920s to the onset of The Great Depression. The book’s title symbolizes the emotional states of deep sadness (depression) and loneliness, the vastness life has to offer, the curiosity of flowing into uncharted territories, the beauty of what lies beneath soon to reach the surface, the voyage by water itself and, most of all, freedom.

“Literature is a big sea full of many fish. I let down my nets and pulled. I'm still pulling.”

Life is literature; it's a reflection of fork in the road journeys amongst a sea of possibilities along the way. There are motifs from childhood trauma and child-parent relationships to dreams and happiness that arise in The Big Sea, alongside one of the book's main themes: the intricacy of race.

Black — the bottom classification of the US caste system built on a social construct transitioning into the cultural identity for a specific ethnic group (Black Americans) — is underscored against the higher deemed status and permanence and flatness of "white." Hughes and I share the same great-grandmother on his maternal side, Lucy Jane Langston—his first and my sixth. In The Big Sea, he describes Lucy as "colored" as he would himself although she was Pamunkey. In turn, upon touching down on the soil of Dakar in Senegal, Langston notes:

“The great Africa of my dreams! But there was one thing that hurt me a lot when I talked with the people. The Africans looked at me and would not believe I was a Negro.”

What you’re (“racially”) called in your house won’t be understood in someone else’s house. Race that’s defined in colors (black, white, red) was a foreign ass concept then and now for anyone from differing homelands with tribes, or similar words but different meanings absent of skin color. It’s heritage that’s attached. That same (Black/US Negro) heritage was a revulsion for Hughes’ self-loathing father, James Nathaniel Hughes. He hated Negroes and was willing to assimilate to anything else, leading him to try to permanently meld into the cultural identity of Mexicans in Mexico.

Throughout this memoir, Hughes interchangeably uses the US (re)classifications of Negro, Colored and Black to make sense of the world for himself. He deep dives into how he views himself and cultural identity; the way his family, himself, and others in his community choose to navigate through caste barriers; and compares and contrasts his racial status during his wide travel within and outside the United States, all while maintaining his steady net in the big sea.

SN: The photos aren’t included in book, but are pivotal to the details in the book.

Caroline “Carrie” (Langston) Hughes holding her son, Langston (1901)

Langston Hughes at age 3 (1904)

Carrie and Langston (1907)

James Nathaniel Hughes, the father of Langston Hughes

Mary (Patterson) Langston, Langston Hughes’ maternal grandmother who raised him

Langston Hughes with Charles S. Johnson, E. Franklin Frazier, Rudolph Fisher and Hubert T. Delaney on the roof of 580 St. Nicholas Avenue, Harlem, on the occasion of a party in Hughes' honor (1924)

Langston Hughes working as a busboy in hotel restaurant before his writing career took hold. He left three poems beside poet Vachel Lindsay's plate and Lindsay read them the next evening at the start of his recital. (Washington D.C., 1925)

Langston Hughes’ poetry book, The Weary Blues, which he wrote in the midst of traveling (1925)

Fire!! magazine created by Langston Hughes, Richard Nugent, Zora Neale Hurston, Gwendolyn Bennett, John Davis, Aaron Douglas, and Wallace Henry Thurman (November 1926)

Jessie Fauset, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston at Tuskegee Institute (1927)

#langston hughes#the big sea#the big sea book#the weary blues#zora neale hurston#jessie fauset#harlem renaissance#thechanelmuse reviews#book review

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

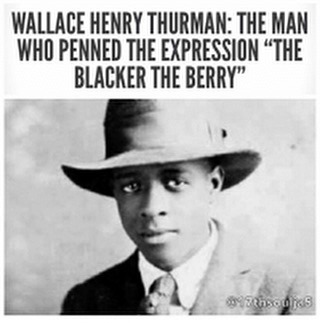

Wallace Henry Thurman was in the early 1930s acknowledged as one of the leading novelists, poets, critics, and playwrights of the Harlem Renaissance. Yet, he questioned the very existence of the movement. He had arrived in New York in 1925 during the second phase of the Harlem Renaissance, then noted as the most influential movement in African-American literary works and creative culture.While there, he did not only help launch two periodicals dedicated to Black artists but also wrote several plays and three novels, with The Blacker the Berry: A Novel of Negro Life becoming his most well-known novel. Indeed, the novel’s line “the blacker the berry, the sweeter the juice” has been referenced in the works of prominent artistes including Kendrick Lamar and Tupac Shakur.

That novel was his first. Thurman centered it on intraracial prejudice, colorism and internalized racism in African-American life. He dedicated it to his maternal grandmother, Emma Jackson, who had helped raise him.

#the blacker the berry#african#african american#kemetic dreams#kendrick lamar#tupac#tupac shakur#emma jackson#wallace henry thurman#africans

391 notes

·

View notes

Photo

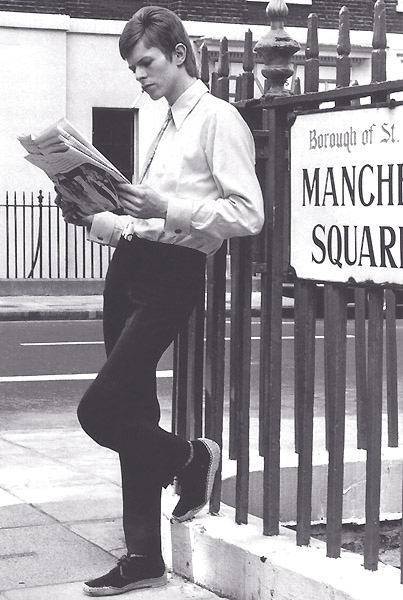

Bowie was a voracious reader. In 2013, he posted a list of his top 100 favorite reads on his Facebook page.

Interviews With Francis Bacon by David Sylvester Billy Liar by Keith Waterhouse Room At The Top by John Braine On Having No Head by Douglass Harding Kafka Was The Rage by Anatole Broyard A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess City Of Night by John Rechy The Brief Wondrous Life Of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert Iliad by Homer As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner Tadanori Yokoo by Tadanori Yokoo Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin Inside The Whale And Other Essays by George Orwell Mr. Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood Halls Dictionary Of Subjects And Symbols In Art by James A. Hall David Bomberg by Richard Cork Blast by Wyndham Lewis Passing by Nella Larson Beyond The Brillo Box by Arthur C. Danto The Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes In Bluebeard’s Castle by George Steiner Hawksmoor by Peter Ackroyd The Divided Self by R. D. Laing The Stranger by Albert Camus Infants Of The Spring by Wallace Thurman The Quest For Christa T by Christa Wolf The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin Nights At The Circus by Angela Carter The Master And Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov Herzog by Saul Bellow Puckoon by Spike Milligan Black Boy by Richard Wright The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea by Yukio Mishima Darkness At Noon by Arthur Koestler The Waste Land by T.S. Elliot McTeague by Frank Norris Money by Martin Amis The Outsider by Colin Wilson Strange People by Frank Edwards English Journey by J.B. Priestley A Confederacy Of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole The Day Of The Locust by Nathanael West 1984 by George Orwell The Life And Times Of Little Richard by Charles White Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: The Golden Age of Rock by Nik Cohn Mystery Train by Greil Marcus Beano (comic, ’50s) Raw (comic, ’80s) White Noise by Don DeLillo Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm And Blues And The Southern Dream Of Freedom by Peter Guralnick Silence: Lectures And Writing by John Cage Writers At Work: The Paris Review Interviews edited by Malcolm Cowley The Sound Of The City: The Rise Of Rock And Roll by Charlie Gillete Octobriana And The Russian Underground by Peter Sadecky The Street by Ann Petry Wonder Boys by Michael Chabon Last Exit To Brooklyn By Hubert Selby, Jr. A People’s History Of The United States by Howard Zinn The Age Of American Unreason by Susan Jacoby Metropolitan Life by Fran Lebowitz The Coast Of Utopia by Tom Stoppard The Bridge by Hart Crane All The Emperor’s Horses by David Kidd Fingersmith by Sarah Waters Earthly Powers by Anthony Burgess The 42nd Parallel by John Dos Passos Tales Of Beatnik Glory by Ed Saunders The Bird Artist by Howard Norman Nowhere To Run The Story Of Soul Music by Gerri Hirshey Before The Deluge by Otto Friedrich Sexual Personae: Art And Decadence From Nefertiti To Emily Dickinson by Camille Paglia The American Way Of Death by Jessica Mitford In Cold Blood by Truman Capote Lady Chatterly’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence Teenage by Jon Savage Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh The Hidden Persuaders by Vance Packard The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin Viz (comic, early ’80s) Private Eye (satirical magazine, ’60s – ’80s) Selected Poems by Frank O’Hara The Trial Of Henry Kissinger by Christopher Hitchens Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes Maldoror by Comte de Lautréamont On The Road by Jack Kerouac Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder by Lawrence Weschler Zanoni by Edward Bulwer-Lytton Transcendental Magic, Its Doctrine and Ritual by Eliphas Lévi The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels The Leopard by Giusseppe Di Lampedusa Inferno by Dante Alighieri A Grave For A Dolphin by Alberto Denti di Pirajno The Insult by Rupert Thomson In Between The Sheets by Ian McEwan A People’s Tragedy by Orlando Figes Journey Into The Whirlwind by Eugenia Ginzburg

222 notes

·

View notes

Photo

David Bowie’s 100 Favourite Books:

Interviews With Francis Bacon by David Sylvester

Billy Liar by Keith Waterhouse

Room At The Top by John Braine

On Having No Head by Douglass Harding

Kafka Was The Rage by Anatole Broyard

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

Of Night by John Rechy

The Brief Wondrous Life Of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

Iliad by Homer

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

Tadanori Yokoo by Tadanori Yokoo

Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin

Inside The Whale And Other Essays by George Orwell

Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood

Halls Dictionary Of Subjects And Symbols In Art by James A. Hall

David Bomberg by Richard Cork

Blast by Wyndham Lewis

Passing by Nella Larson

Beyond The Brillo Box by Arthur C. Danto

The Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes

In Bluebeard’s Castle by George Steiner

Hawksmoor by Peter Ackroyd

The Divided Self by R. D. Laing

The Stranger by Albert Camus

Infants Of The Spring by Wallace Thurman

The Quest For Christa T by Christa Wolf

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin

Nights At The Circus by Angela Carter

The Master And Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Herzog by Saul Bellow

Puckoon by Spike Milligan

Black Boy by Richard Wright

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea by Yukio Mishima

Darkness At Noon by Arthur Koestler

The Waste Land by T.S. Elliot

McTeague by Frank Norris

Money by Martin Amis

The Outsider by Colin Wilson

Strange People by Frank Edwards

English Journey by J.B. Priestley

A Confederacy Of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

The Day Of The Locust by Nathanael West

1984 by George Orwell

The Life And Times Of Little Richard by Charles White

Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: The Golden Age of Rock by Nik Cohn

Mystery Train by Greil Marcus

Beano (comic, )

Raw (comic, ’80s)

White Noise by Don DeLillo

Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm And Blues And The Southern Dream Of Freedom by Peter Guralnick

Silence: Lectures And Writing by John Cage

Writers At Work: The Paris Review Interviews edited by Malcolm Cowley

The Sound Of The City: The Rise Of Rock And Roll by Charlie Gillette

Octobriana And The Russian Underground by Peter Sadecky

The Street by Ann Petry

Wonder Boys by Michael Chabon

Last Exit To Brooklyn by Hubert Selby, Jr.

A People’s History Of The United States by Howard Zinn

The Age Of American Unreason by Susan Jacoby

Metropolitan Life by Fran Lebowitz

The Coast Of Utopia by Tom Stoppard

The Bridge by Hart Crane

All The Emperor’s Horses by David Kidd

Fingersmith by Sarah Waters

Earthly Powers by Anthony Burgess

The 42nd Parallel by John Dos Passos

Tales Of Beatnik Glory by Ed Saunders

The Bird Artist by Howard Norman

Nowhere To Run The Story Of Soul Music by Gerri Hirshey

Before The Deluge by Otto Friedrich

Sexual Personae: Art And Decadence From Nefertiti To Emily Dickinson by Camille Paglia

The American Way Of Death by Jessica Mitford

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

Lady Lover by D.H. Lawrence

Teenage by Jon Savage

Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh

The Hidden Persuaders by Vance Packard

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

Viz (comic, ’80s)

Private Eye (satirical magazine, – ’80s)

Selected Poems by Frank O’Hara

The Trial Of Henry Kissinger by Christopher Hitchens

Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes

Maldoror by Comte de Lautréamont

On The Road by Jack Kerouac

Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder by Lawrence Weschler

Zanoni by Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Transcendental Magic, Its Doctrine and Ritual by Eliphas Lévi

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

The Leopard by Giuseppe Di Lampedusa

Inferno by Dante Alighieri

A Grave For A Dolphin by Alberto Denti di Pirajno

The Insult by Rupert Thomson

In Between The Sheets by Ian McEwan

A People’s Tragedy by Orlando Figes

Journey Into The Whirlwind by Eugenia Ginzburg

358 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Sword Master Rates 10 Sword Fights From Movies And TV | How Real Is It?

Professional swordsman Dave Rawlings broke down 10 sword fights in movies and TV, critiquing their realism and technique. Rawlings has over 15 years' experience teaching Western Swordsmanship. He has been featured in the documentary series "Warriors" and "Bloody Tales of the Tower." He advised the Wallace Collection on its exhibition "The Noble Art of the Sword," and he teaches longsword at the London Longsword Academy.

Rawlings looked at the skill of Henry Cavill in "The Witcher" and Dwayne Johnson in "The Scorpion King." He also critiqued the realism of historical and fantasy scenes from "The Mask Of Zorro," "Gladiator" and "The Princess Bride." He also rated sword fights in "Game of Thrones," including Brienne of Tarth and Arya Stark, and Ned Stark and Jamie Lannister. He rated the samurai-sword skill of Keanu Reeves in "47 Ronin" and Uma Thurman in "Kill Bill: Volume 1."He analyzed the principles of sword fighting in the "Die Another Day" fencing scene and the light saber fight in "Star Wars: The Last Jedi."

1 note

·

View note

Text

David Bowie's Top 100 Reads:

Interviews With Francis Bacon by David Sylvester

Billy Liar by Keith Waterhouse

Room At The Top by John Braine

On Having No Head by Douglass Harding

Kafka Was The Rage by Anatole Broyard

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

City Of Night by John Rechy

The Brief Wondrous Life Of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

Iliad by Homer

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

Tadanori Yokoo by Tadanori Yokoo

Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin

Inside The Whale And Other Essays by George Orwell

Mr. Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood

Halls Dictionary Of Subjects And Symbols In Art by James A. Hall

David Bomberg by Richard Cork

Blast by Wyndham Lewis

Passing by Nella Larson

Beyond The Brillo Box by Arthur C. Danto

The Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes

In Bluebeard’s Castle by George Steiner

Hawksmoor by Peter Ackroyd

The Divided Self by R. D. Laing

The Stranger by Albert Camus

Infants Of The Spring by Wallace Thurman

The Quest For Christa T by Christa Wolf

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin

Nights At The Circus by Angela Carter

The Master And Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Herzog by Saul Bellow

Puckoon by Spike Milligan

Black Boy by Richard Wright

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea by Yukio Mishima

Darkness At Noon by Arthur Koestler

The Waste Land by T.S. Elliot

McTeague by Frank Norris

Money by Martin Amis

The Outsider by Colin Wilson

Strange People by Frank Edwards

English Journey by J.B. Priestley

A Confederacy Of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

The Day Of The Locust by Nathanael West

1984 by George Orwell

The Life And Times Of Little Richard by Charles White

Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: The Golden Age of Rock by Nik Cohn

Mystery Train by Greil Marcus

Beano (comic, ’50s)

Raw (comic, ’80s)

White Noise by Don DeLillo

Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm And Blues And The Southern Dream Of Freedom by Peter Guralnick

Silence: Lectures And Writing by John Cage

Writers At Work: The Paris Review Interviews edited by Malcolm Cowley

The Sound Of The City: The Rise Of Rock And Roll by Charlie Gillete

Octobriana And The Russian Underground by Peter Sadecky

The Street by Ann Petry

Wonder Boys by Michael Chabon

Last Exit To Brooklyn By Hubert Selby, Jr.

A People’s History Of The United States by Howard Zinn

The Age Of American Unreason by Susan Jacoby

Metropolitan Life by Fran Lebowitz

The Coast Of Utopia by Tom Stoppard

The Bridge by Hart Crane

All The Emperor’s Horses by David Kidd

Fingersmith by Sarah Waters

Earthly Powers by Anthony Burgess

The 42nd Parallel by John Dos Passos

Tales Of Beatnik Glory by Ed Saunders

The Bird Artist by Howard Norman

Nowhere To Run The Story Of Soul Music by Gerri Hirshey

Before The Deluge by Otto Friedrich

Sexual Personae: Art And Decadence From Nefertiti To Emily Dickinson by Camille Paglia

The American Way Of Death by Jessica Mitford

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

Lady Chatterly’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence

Teenage by Jon Savage

Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh

The Hidden Persuaders by Vance Packard

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

Viz (comic, early ’80s)

Private Eye (satirical magazine, ’60s – ’80s)

Selected Poems by Frank O’Hara

The Trial Of Henry Kissinger by Christopher Hitchens

Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes

Maldoror by Comte de Lautréamont

On The Road by Jack Kerouac

Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder by Lawrence Weschler

Zanoni by Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Transcendental Magic, Its Doctrine and Ritual by Eliphas Lévi

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

The Leopard by Giusseppe Di Lampedusa

Inferno by Dante Alighieri

A Grave For A Dolphin by Alberto Denti di Pirajno

The Insult by Rupert Thomson

In Between The Sheets by Ian McEwan

A People’s Tragedy by Orlando Figes

Journey Into The Whirlwind by Eugenia Ginzburg

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Queer Figures of the Harlem Renaissance

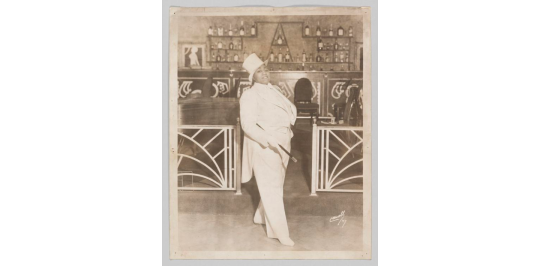

Gladys Bentley

Gladys Bentley was a blues singer who thrived during the Harlem Renaissance during the 20s and early 30s, becoming known as Harlem’s favourite ‘bulldagger’ and was known to have many female lovers during her life. Often singing controversial songs and known as a male impersonator for dressing in white tuxedos and top hats, she frequently performed and headlined at the famous gay speakeasy, The Clam House. Around 1930, Bentley married a white woman in Atlantic City, New Jersey. But later, Bentley went back in the closet and her all-too-brief period of fame ended in the 1930s. Ultimately, homophobia, uniting with racism, sexism, and classism, destroyed Bentley’s ability to live creatively and freely and she drew back into the closet and claimed to marry a man who denied ever being married to Bentley (Wilson 2010).

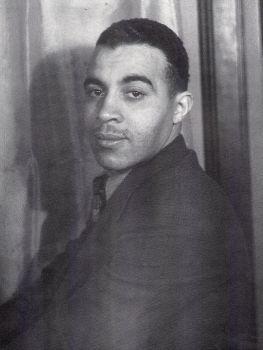

Richard Bruce Nugent

Richard Bruce Nugent was one of the few publicly out queer artists of the Harlem Renaissance and was as the ‘perfumed orchid of the New Negro Movement’ (Glick 2009:86). Nugent was known to have lived with another queer writer Wallace Thurman from the years 1926 to 1928 in Harlem, which led to the publishing of the story ‘Smoke, Lilies, and Jade’ in Thurman's black literary publication Fire!!. The story covered themes of bisexuality and more explicitly interracial male desire. Despite his openness about male attraction, Nugent married Grace Marr in 1952 until her suicide in 1969 (Wirth 2002).

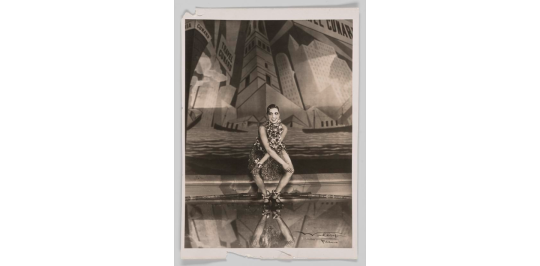

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker was a well-known singer, dancer and actress within the early years of the Harlem Renaissance. However, she struggled to find an audience within the US and predominantly grew her large career overseas in Paris. Because of this, she is often known as the first Black international star. Her song, ‘J’ai Deux Amours,’ meaning ‘I have two loves,’ became one of her biggest, in which Baker took to mean France and the United States (Goodman 2019). Baker identified herself as bisexual. She married four different times throughout her life but carried on affairs with women, including Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and French author Colette.

Langston Hughes

One of the most well-known and written about, poet, novelist and playwright, Langston Hughes, was a primary voice of the Harlem Renaissance. Although Hughes never spoke of his sexuality often in public, there are a lot of homosexual themes in his work such as ‘Blessed Assurance’ and ‘Seven People Dancing.’ Garber wrote that ‘Hughes was exceedingly cagy and evasive about his emotional involvements, even with his closest friends; as a result, though most of Hughes' biographers concede that the poet was at least sporadically homosexual, the exact nature of his sexuality remains uncertain’ (1990:326). He also often attended and was fond of the Harlem drag balls, naming them the infamous ‘spectacles of colour’.

As professor Henry Louis Gates describes, the Harlem Renaissance was, ‘surely as gay as it was black’ (1993:233). With the growth in art, jazz and blues, and drag balls, this time period was defined as ‘homosexual mecca’ or queer paradise and can be seen to have had many other LGBTQ artists that led the Harlem Renaissance. Some of the famous names including Countee Cullen, Ethel Waters, Ma Rainey, Claude Mckay, Alain Locke, Bessie Smith, James Richmond Barthé, Alberta Hunter, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, and Angelina Weld Grimké.

Gates, Henry Louis (1993) The Black Man’s Burden. In Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory ed. Michael Warner, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 230-238.

Glick, Elisa (2009) Materializing Queer Desire: Oscar Wilde to Andy Warhol. Albany: State University Press.

Jules-Rosette, Bennetta (2007) Josephine Baker in Art and Life. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Schwarz, A. B. Christa (2003) Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Wilson, James F. (2010) Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race, and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Wirth, Thomas H. (2002) Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance. Durham: Duke University Press.

Photo 1: Unknown n.d. A silver gelatin print depicting a black-and-white image of entertainer Gladys Bentley. Bentley is depicted standing in three-quarters profile with her head turned towards the viewer, and her proper right foot forward. She is wearing a white tuxedo, top hat, and she is holding a cane under her proper right arm. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Photo 2: Unknown n.d. Photograph of Richard Bruce Nugent (also Bruce Nugent). Image courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University.

Photo 3: Walery n.d. Photographic print of Josephine Baker performing at the Folies Bergère. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and National Portrait Gallery, gift from Jean-Claude Baker.

Photo 4: Unknown n.d. Langston Hughes as a young man. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library.

#ballroom#house ballroom#lgbt ballroom#harlem renaissance#queer#gladys bentley#richard bruce nugent#josephine baker#langston hughes#queer history

241 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yeah, this sword expert says much the same: when in a sword fight what you want is to put as much distance as possible between you and your opponent - like for instance running away from them!

youtube

Sword Master Rates 10 Sword Fights From Movies And TV | How Real Is It?

Professional swordsman Dave Rawlings broke down 10 sword fights in movies and TV, critiquing their realism and technique. Rawlings has over 15 years' experience teaching Western Swordsmanship. He has been featured in the documentary series "Warriors" and "Bloody Tales of the Tower." He advised the Wallace Collection on its exhibition "The Noble Art of the Sword," and he teaches longsword at the London Longsword Academy.

Rawlings looked at the skill of Henry Cavill in "The Witcher" and Dwayne Johnson in "The Scorpion King." He also critiqued the realism of historical and fantasy scenes from "The Mask Of Zorro," "Gladiator" and "The Princess Bride." He also rated sword fights in "Game of Thrones," including Brienne of Tarth and Arya Stark, and Ned Stark and Jamie Lannister. He rated the samurai-sword skill of Keanu Reeves in "47 Ronin" and Uma Thurman in "Kill Bill: Volume 1."He analyzed the principles of sword fighting in the "Die Another Day" fencing scene and the light saber fight in "Star Wars: The Last Jedi."

We distilled some of the wisdom from this weekend’s knife disarm class into the most internet-friendly form. Enjoy!

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sweat

A short story by Zora Neale Hurston (from Fire!! Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists [1926] edited by Wallace Henry Thurman) It was eleven o’clock of a Spring night in Florida. It was Sunday. Any other night, Delia Jones would have been in bed for two hours by this time. But she was a washwoman, and Monday morning meant a great deal to her. So she collected the soiled clothes on Saturday when…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri.

He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form called jazz poetry. Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance in New York City. He famously wrote about the period that "the negro was in vogue", which was later paraphrased as "when Harlem was in vogue".

Biography

Ancestry and childhood

Like many African Americans, Hughes has complex ancestry. Both of Hughes' paternal great-grandmothers were enslaved African Americans and both of his paternal great-grandfathers were white slave owners in Kentucky. According to Hughes, one of these men was Sam Clay, a Scottish-American whiskey distiller of Henry County and supposedly a relative of the statesman Henry Clay. The other was Silas Cushenberry, a Jewish-American slave trader of Clark County. Hughes's maternal grandmother Mary Patterson was of African-American, French, English and Native American descent. One of the first women to attend Oberlin College, she married Lewis Sheridan Leary, also of mixed race, before her studies. Leary subsequently joined John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859 and died from his wounds.

In 1869 the widow Mary Patterson Leary married again, into the elite, politically active Langston family. (See The Talented Tenth.) Her second husband was Charles Henry Langston, of African-American, Euro-American and Native American ancestry. He and his younger brother John Mercer Langston worked for the abolitionist cause and helped lead the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society in 1858. Charles Langston later moved to Kansas, where he was active as an educator and activist for voting and rights for African Americans. Charles and Mary's daughter Caroline was the mother of Langston Hughes.

Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, the second child of school teacher Carrie (Caroline) Mercer Langston and James Nathaniel Hughes (1871–1934). Langston Hughes grew up in a series of Midwestern small towns. Hughes' father left his family and later divorced Carrie. He traveled to Cuba and then Mexico, seeking to escape the enduring racism in the United States.

After his parents separated, his mother traveled seeking employment, and young Langston Hughes was raised mainly in Lawrence, Kansas by his maternal grandmother, Mary Patterson Langston. Through the black American oral tradition and drawing from the activist experiences of her generation, Mary Langston instilled in her grandson a lasting sense of racial pride. He spent most of his childhood in Lawrence. In his 1940 autobiography The Big Sea he wrote: "I was unhappy for a long time, and very lonesome, living with my grandmother. Then it was that books began to happen to me, and I began to believe in nothing but books and the wonderful world in books — where if people suffered, they suffered in beautiful language, not in monosyllables, as we did in Kansas."

After the death of his grandmother, Hughes went to live with family friends, James and Mary Reed, for two years. Later, Hughes lived again with his mother Carrie in Lincoln, Illinois. She had remarried when he was still an adolescent, and eventually they moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where he attended high school.

His writing experiments began when he was young. While in grammar school in Lincoln, Hughes was elected class poet. He stated that in retrospect he thought it was because of the stereotype about African Americans having rhythm.

I was a victim of a stereotype. There were only two of us Negro kids in the whole class and our English teacher was always stressing the importance of rhythm in poetry. Well, everyone knows, except us, that all Negroes have rhythm, so they elected me as class poet.

During high school in Cleveland, Hughes wrote for the school newspaper, edited the yearbook, and began to write his first short stories, poetry, and dramatic plays. His first piece of jazz poetry, "When Sue Wears Red," was written while he was in high school.

Relationship with father

Hughes had a very poor relationship with his father, with whom he lived in Mexico for a brief period in 1919. Upon graduating from high school in June 1920, Hughes returned to Mexico to live with his father, hoping to convince him to support his plan to attend Columbia University. Hughes later said that, prior to arriving in Mexico, "I had been thinking about my father and his strange dislike of his own people. I didn't understand it, because I was a Negro, and I liked Negroes very much." Initially, his father had hoped for Hughes to attend a university abroad, and to study for a career in engineering. On these grounds, he was willing to provide financial assistance to his son but did not support his desire to be a writer. Eventually, Hughes and his father came to a compromise: Hughes would study engineering, so long as he could attend Columbia. His tuition provided; Hughes left his father after more than a year. While at Columbia in 1921, Hughes managed to maintain a B+ grade average. He left in 1922 because of racial prejudice. He was attracted more to the people and the neighborhood of Harlem than his studies, though he continued writing poetry.

Adulthood

Hughes worked at various odd jobs, before serving a brief tenure as a crewman aboard the S.S. Malone in 1923, spending six months traveling to West Africa and Europe. In Europe, Hughes left the S.S. Malone for a temporary stay in Paris. There he met and had a romance with Anne Marie Coussey, a British-educated African from a well-to-do Gold Coast family; they subsequently corresponded but she eventually married Hugh Wooding, a promising Trinidadian lawyer.(Wooding went on to become chancellor of the University of the West Indies; a law school in Trinidad and Tobago was named in his honor.)

During his time in England in the early 1920s, Hughes became part of the black expatriate community. In November 1924, he returned to the U.S. to live with his mother in Washington, D.C. After assorted odd jobs, he gained white-collar employment in 1925 as a personal assistant to the historian Carter G. Woodson at the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. As the work demands limited his time for writing, Hughes quit the position to work as a busboy at the Wardman Park Hotel. There he encountered the poet Vachel Lindsay, with whom he shared some poems. Impressed with the poems, Lindsay publicized his discovery of a new black poet. By this time, Hughes's earlier work had been published in magazines and was about to be collected into his first book of poetry.

The following year, Hughes enrolled in Lincoln University, a historically black university in Chester County, Pennsylvania. He joined the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. Thurgood Marshall, who later became an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, was a classmate of Hughes during his undergraduate studies.

After Hughes earned a B.A. degree from Lincoln University in 1929, he returned to New York. Except for travels to the Soviet Union and parts of the Caribbean, he lived in Harlem as his primary home for the remainder of his life. During the 1930s, he became a resident of Westfield, New Jersey.

Sexuality

Some academics and biographers believe that Hughes was homosexual and included homosexual codes in many of his poems, as did Walt Whitman, whom Hughes cited as an influence on his poetry. Hughes's story "Blessed Assurance" deals with a father's anger over his son's effeminacy and "queerness". The biographer Aldrich argues that, in order to retain the respect and support of black churches and organizations and avoid exacerbating his precarious financial situation, Hughes remained closeted.

Arnold Rampersad, the primary biographer of Hughes, determined that Hughes exhibited a preference for other African-American men in his work and life. But, in his biography Rampersad denies Hughes's homosexuality, and concludes that Hughes was probably asexual and passive in his sexual relationships. Hughes did, however, show a respect and love for his fellow black man (and woman). Other scholars argue for his homosexuality: his love of black men is evidenced in a number of reported unpublished poems to an alleged black male lover.

Death

On May 22, 1967, Hughes died in New York City at the age of 65 from complications after abdominal surgery related to prostate cancer. His ashes are interred beneath a floor medallion in the middle of the foyer in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. It is the entrance to an auditorium named for him. The design on the floor is an African cosmogram entitled Rivers. The title is taken from his poem "The Negro Speaks of Rivers". Within the center of the cosmogram is the line: "My soul has grown deep like the rivers".

Career

First published in 1921 in The Crisis — official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) — "The Negro Speaks of Rivers", which became Hughes's signature poem, was collected in his first book of poetry The Weary Blues (1926). Hughes's first and last published poems appeared in The Crisis; more of his poems were published in The Crisis than in any other journal. Hughes' life and work were enormously influential during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, alongside those of his contemporaries, Zora Neale Hurston, Wallace Thurman, Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, Richard Bruce Nugent, and Aaron Douglas. Except for McKay, they worked together also to create the short-lived magazine Fire!! Devoted to Younger Negro Artists.

Hughes and his contemporaries had different goals and aspirations than the black middle class. Hughes and his fellows tried to depict the "low-life" in their art, that is, the real lives of blacks in the lower social-economic strata. They criticized the divisions and prejudices within the black community based on skin color. Hughes wrote what would be considered their manifesto, "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain", published in The Nation in 1926:

"The younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly, too. The tom-tom cries, and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn't matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain free within ourselves."

His poetry and fiction portrayed the lives of the working-class blacks in America, lives he portrayed as full of struggle, joy, laughter, and music. Permeating his work is pride in the African-American identity and its diverse culture. "My seeking has been to explain and illuminate the Negro condition in America and obliquely that of all human kind," Hughes is quoted as saying. He confronted racial stereotypes, protested social conditions, and expanded African America’s image of itself; a "people's poet" who sought to reeducate both audience and artist by lifting the theory of the black aesthetic into reality.

Hughes stressed a racial consciousness and cultural nationalism devoid of self-hate. His thought united people of African descent and Africa across the globe to encourage pride in their diverse black folk culture and black aesthetic. Hughes was one of the few prominent black writers to champion racial consciousness as a source of inspiration for black artists. His African-American race consciousness and cultural nationalism would influence many foreign black writers, including Jacques Roumain, Nicolás Guillén, Léopold Sédar Senghor, and Aimé Césaire. Along with the works of Senghor, Césaire, and other French-speaking writers of Africa and of African descent from the Caribbean, such as René Maran from Martinique and Léon Damas from French Guiana in South America, the works of Hughes helped to inspire the Négritude movement in France. A radical black self-examination was emphasized in the face of European colonialism. In addition to his example in social attitudes, Hughes had an important technical influence by his emphasis on folk and jazz rhythms as the basis of his poetry of racial pride.

In 1930, his first novel, Not Without Laughter, won the Harmon Gold Medal for literature. At a time before widespread arts grants, Hughes gained the support of private patrons and he was supported for two years prior to publishing this novel. The protagonist of the story is a boy named Sandy, whose family must deal with a variety of struggles due to their race and class, in addition to relating to one another.

In 1931, Hughes helped form the "New York Suitcase Theater" with playwright Paul Peters, artist Jacob Burck, and writer (soon-to-be underground spy) Whittaker Chambers, an acquaintance from Columbia. In 1932, he was part of a board to produce a Soviet film on "Negro Life" with Malcolm Cowley, Floyd Dell, and Chambers.

In 1932, Hughes and Ellen Winter wrote a pageant to Caroline Decker in an attempt to celebrate her work with the striking coal miners of the Harlan County War, but it was never performed. It was judged to be a "long, artificial propaganda vehicle too complicated and too cumbersome to be performed."

Maxim Lieber became his literary agent, 1933–45 and 1949–50. (Chambers and Lieber worked in the underground together around 1934–35.)

Hughes' first collection of short stories was published in 1934 with The Ways of White Folks. He finished the book at a Carmel, California cottage provided for a year by Noel Sullivan, another patron. These stories are a series of vignettes revealing the humorous and tragic interactions between whites and blacks. Overall, they are marked by a general pessimism about race relations, as well as a sardonic realism. He also became an advisory board member to the (then) newly formed San Francisco Workers' School (later the California Labor School).

In 1935 Hughes received a Guggenheim Fellowship. The same year that Hughes established his theatre troupe in Los Angeles, he realized an ambition related to films by co-writing the screenplay for Way Down South. Hughes believed his failure to gain more work in the lucrative movie trade was due to racial discrimination within the industry.

In Chicago, Hughes founded The Skyloft Players in 1941, which sought to nurture black playwrights and offer theatre "from the black perspective." Soon thereafter, he was hired to write a column for the Chicago Defender, in which he presented some of his "most powerful and relevant work", giving voice to black people. The column ran for twenty years. In 1943, Hughes began publishing stories about a character he called Jesse B. Semple, often referred to and spelled "Simple", the everyday black man in Harlem who offered musings on topical issues of the day. Although Hughes seldom responded to requests to teach at colleges, in 1947 he taught at Atlanta University. In 1949, he spent three months at the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools as a visiting lecturer. Between 1942 and 1949 Hughes was a frequent writer and served on the editorial board of Common Ground, a literary magazine focused on cultural pluralism in the United States published by the Common Council for American Unity (CCAU).

He wrote novels, short stories, plays, poetry, operas, essays, and works for children. With the encouragement of his best friend and writer, Arna Bontemps, and patron and friend, Carl Van Vechten, he wrote two volumes of autobiography, The Big Sea and I Wonder as I Wander, as well as translating several works of literature into English.

From the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, Hughes' popularity among the younger generation of black writers varied even as his reputation increased worldwide. With the gradual advancement toward racial integration, many black writers considered his writings of black pride and its corresponding subject matter out of date. They considered him a racial chauvinist. He found some new writers, among them James Baldwin, lacking in such pride, over-intellectual in their work, and occasionally vulgar.

Hughes wanted young black writers to be objective about their race, but not to scorn it or flee it. He understood the main points of the Black Power movement of the 1960s, but believed that some of the younger black writers who supported it were too angry in their work. Hughes's work Panther and the Lash, posthumously published in 1967, was intended to show solidarity with these writers, but with more skill and devoid of the most virulent anger and racial chauvinism some showed toward whites. Hughes continued to have admirers among the larger younger generation of black writers. He often helped writers by offering advice and introducing them to other influential persons in the literature and publishing communities. This latter group, including Alice Walker, whom Hughes discovered, looked upon Hughes as a hero and an example to be emulated within their own work. One of these young black writers (Loften Mitchell) observed of Hughes:

"Langston set a tone, a standard of brotherhood and friendship and cooperation, for all of us to follow. You never got from him, 'I am the Negro writer,' but only 'I am a Negro writer.' He never stopped thinking about the rest of us."

Political views

Hughes, like many black writers and artists of his time, was drawn to the promise of Communism as an alternative to a segregated America. Many of his lesser-known political writings have been collected in two volumes published by the University of Missouri Press and reflect his attraction to Communism. An example is the poem "A New Song".

In 1932, Hughes became part of a group of black people who went to the Soviet Union to make a film depicting the plight of African Americans in the United States. The film was never made, but Hughes was given the opportunity to travel extensively through the Soviet Union and to the Soviet-controlled regions in Central Asia, the latter parts usually closed to Westerners. While there, he met Robert Robinson, an African American living in Moscow and unable to leave. In Turkmenistan, Hughes met and befriended the Hungarian author Arthur Koestler, then a Communist who was given permission to travel there.

As later noted in Koestler's autobiography, Hughes, together with some forty other Black Americans, had originally been invited to the Soviet Union to produce a Soviet film on "Negro Life", but the Soviets dropped the film idea because of their 1933 success in getting the US to recognize the Soviet Union and establish an embassy in Moscow. This entailed a toning down of Soviet propaganda on racial segregation in America. Hughes and his fellow Blacks were not informed of the reasons for the cancelling, but he and Koestler worked it out for themselves.

Hughes also managed to travel to China and Japan before returning to the States.

Hughes's poetry was frequently published in the CPUSA newspaper and he was involved in initiatives supported by Communist organizations, such as the drive to free the Scottsboro Boys. Partly as a show of support for the Republican faction during the Spanish Civil War, in 1937 Hughes traveled to Spain as a correspondent for the Baltimore Afro-American and other various African-American newspapers. Hughes was also involved in other Communist-led organizations such as the John Reed Clubs and the League of Struggle for Negro Rights. He was more of a sympathizer than an active participant. He signed a 1938 statement supporting Joseph Stalin's purges and joined the American Peace Mobilization in 1940 working to keep the U.S. from participating in World War II.

Hughes initially did not favor black American involvement in the war because of the persistence of discriminatory U.S. Jim Crow laws and racial segregation and disfranchisement throughout the South. He came to support the war effort and black American participation after deciding that war service would aid their struggle for civil rights at home. The scholar Anthony Pinn has noted that Hughes, together with Lorraine Hansberry and Richard Wright, was a humanist "critical of belief in God. They provided a foundation for nontheistic participation in social struggle." Pinn has found that such writers are sometimes ignored in the narrative of American history that chiefly credits the civil rights movement to the work of affiliated Christian people.

Hughes was accused of being a Communist by many on the political right, but he always denied it. When asked why he never joined the Communist Party, he wrote, "it was based on strict discipline and the acceptance of directives that I, as a writer, did not wish to accept." In 1953, he was called before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations led by Senator Joseph McCarthy. He stated, "I never read the theoretical books of socialism or communism or the Democratic or Republican parties for that matter, and so my interest in whatever may be considered political has been non-theoretical, non-sectarian, and largely emotional and born out of my own need to find some way of thinking about this whole problem of myself." Following his testimony, Hughes distanced himself from Communism. He was rebuked by some on the Radical Left who had previously supported him. He moved away from overtly political poems and towards more lyric subjects. When selecting his poetry for his Selected Poems (1959) he excluded all his radical socialist verse from the 1930s.

Representation in other media

Hughes was featured reciting his poetry on the album Weary Blues (MGM, 1959), with music by Charles Mingus and Leonard Feather, and he also contributed lyrics to Randy Weston's Uhuru Afrika (Roulette, 1960).

Hughes' life has been portrayed in film and stage productions since the late 20th century. In Looking for Langston (1989), British filmmaker Isaac Julien claimed him as a black gay icon — Julien thought that Hughes' sexuality had historically been ignored or downplayed. Film portrayals of Hughes include Gary LeRoi Gray's role as a teenage Hughes in the short subject film Salvation (2003) (based on a portion of his autobiography The Big Sea), and Daniel Sunjata as Hughes in the Brother to Brother (2004). Hughes' Dream Harlem, a documentary by Jamal Joseph, examines Hughes' works and environment.

Paper Armor (1999) by Eisa Davis and Hannibal of the Alps (2005) by Michael Dinwiddie are plays by African-American playwrights that address Hughes's sexuality. Spike Lee's 1996 film Get on the Bus, included a black gay character, played by Isaiah Washington, who invokes the name of Hughes and punches a homophobic character, saying, "This is for James Baldwin and Langston Hughes."

Hughes was also featured prominently in a national campaign sponsored by the Center for Inquiry (CFI) known as African Americans for Humanism.

Hughes' Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods for Jazz, written in 1960, was performed for the first time in March 2009 with specially composed music by Laura Karpman at Carnegie Hall, at the Honor festival curated by Jessye Norman in celebration of the African-American cultural legacy. Ask Your Mama is the centerpiece of "The Langston Hughes Project", a multimedia concert performance directed by Ron McCurdy, professor of music in the Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California. The European premiere of The Langston Hughes Project, featuring Ice-T and McCurdy, took place at the Barbican Centre, London, on November 21, 2015, as part of the London Jazz Festival.

On September 22, 2016, his poem "I, Too" was printed on a full page of the New York Times in response to the riots of the previous day in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Literary archives

The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University holds the Langston Hughes papers (1862–1980) and the Langston Hughes collection (1924–1969) containing letters, manuscripts, personal items, photographs, clippings, artworks, and objects that document the life of Hughes. The Langston Hughes Memorial Library on the campus of Lincoln University, as well as at the James Weldon Johnson Collection within the Yale University also hold archives of Hughes' work.

Honors and awards

1926: Hughes won the Witter Bynner Undergraduate Poetry Prize.

1935: Hughes was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, which allowed him to travel to Spain and Russia.

1941: Hughes was awarded a fellowship from the Rosenwald Fund.

1943: Lincoln University awarded Hughes an honorary Litt.D.

1954: Hughes won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.

1960: the NAACP awarded Hughes the Spingarn Medal for distinguished achievements by an African American.

1961: National Institute of Arts and Letters.

1963: Howard University awarded Hughes an honorary doctorate.

1964: Western Reserve University awarded Hughes an honorary Litt.D.

1973: the first Langston Hughes Medal was awarded by the City College of New York.

1979: Langston Hughes Middle School was created in Reston, Virginia.

1981: New York City Landmark status was given to the Harlem home of Langston Hughes at 20 East 127th Street (40°48′26.32″N 73°56′25.54″W) by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and 127th Street was renamed "Langston Hughes Place". The Langston Hughes House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

2002: The United States Postal Service added the image of Langston Hughes to its Black Heritage series of postage stamps.

2002: scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Langston Hughes on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

2009: Langston Hughes High School was created in Fairburn, Georgia.

2015: Google Doodle commemorated his 113th birthday.

Wikipedia

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wallace Henry Thurman (August 16, 1902 – December 22, 1934) was a novelist active during the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote essays, worked as an editor, and was a publisher of short-lived newspapers and literary journals. He was known for his novel The Blacker the Berry: A Novel of Negro Life. He began grade school at age six in Boise, but his poor health led to a two-year absence from school, during which he returned to his grandmother in Salt Lake City. From 1910 to 1914, he lived in Chicago. He finished grammar school in Omaha. He suffered from persistent heart attacks. While living in Pasadena, he caught influenza during the worldwide Influenza Pandemic. He recovered and returned to Salt Lake City, where he finished high school. He was a voracious reader. He enjoyed the works of Plato, Aristotle, Shakespeare, Havelock Ellis, Flaubert, Charles Baudelaire, and many others. He wrote his first novel at the age of 10. He attended the University of Utah as a pre-medical student. He transferred to USC but left without earning a degree. He met and befriended the writer Arna Bontemps, and became a reporter and columnist for an African American-owned newspaper. He started a magazine, Outlet. He moved to Harlem. He worked as a ghostwriter, publisher, and editor, as well as writing novels, plays, and articles. He became the editor of The Messenger, a socialist journal addressed to African Americans. There he was the first to publish the adult-themed stories of Langston Hughes. He left the journal to become the editor of World Tomorrow. He collaborated in founding the literary magazine Fire!!. Among its contributors were Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Bruce Nugent, Aaron Douglas, and Gwendolyn B. Bennett. He was asked to edit a magazine called Harlem: A Forum of Negro Life; its contributors included Alain Locke, George Schuyler, and Alice Dunbar-Nelson. He became a reader for a major New York publishing company, the first African American to work in such a position. He wrote a play, Harlem, which debuted on Broadway. He published Infants of the Spring. He co-authored his final novel, The Interne. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence https://www.instagram.com/p/ChUSPeCOzY5jf2nPo0uXY2ZcyQaYhLoVK21qBk0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Ο Bowie ήταν δεινός αναγνώστης, χανόταν μέσα στα βιβλία(λέγεται ότι προσπαθούσε να διαβάζει ένα βιβλίο την ημέρα) και είχε φροντίσει να ξεχωρίσει τα αγαπημένα του αναγνώσματα, τα οποία είδαν το φως της δημοσιότητας το 2013, στο πλαίσιο της έκθεσης «David Bowie Is» του Art Gallery στο Οντάριο του Καναδά. Οι επιμελητές Geoffrey Marsh και Victoria Broackes συνέλεξαν την λίστα των 100 αγαπημένων του βιβλίων, μια «περιπλάνηση» ανάμεσα σε κλασσικά μυθιστορήματα, περιοδικά, ιστορικούς τίτλους και σύγχρονα αναγνώσματα.

Αν τους ρίξετε μια ματιά θα δείτε πως δεν είχε κάποια ιδιαίτερη προτίμηση σε είδος. Στη λίστα μπορείτε να βρείτε Δάντη, Όργουελ, Κέρουακ, Τζούλιαν Μπαρνς, Κάφκα, Καμύ ακόμη και…Όμηρο.

Η Λίστα με τα 100 αγαπημένα βιβλία του David Bowie:

«Interviews With Francis Bacon» του David Sylvester «Billy Liar» του Keith Waterhouse «Room At The Top» του John Braine «On Having No Head» του Douglass Harding «Kafka Was The Rage» του Anatole Broyard «A Clockwork Orange» του Anthony Burgess «City Of Night» του John Rechy «The Brief Wondrous Life Of Oscar Wao» του Junot Díaz «Madame Bovary» του Gustave Flaubert «Ιλιάδα» του Ομήρου «As I Lay Dying» του William Faulkner «Tadanori Yokoo» του Tadanori Yokoo «Berlin Alexanderplatz» του Alfred Döblin «Inside The Whale And Other Essays» του George Orwell «Mr. Norris Changes Trains» του Christopher Isherwood «Dictionary Of Subjects And Symbols In Art» του James A. Hall «David Bomberg» του Richard Cork «Blast» του Wyndham Lewis «Passing» της Nella Larsen «Beyond The Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective» του Arthur C. Danto «The Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind» του Julian Jaynes «In Bluebeard’s Castle» του George Steiner «Hawksmoor» του Peter Ackroyd «The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness» του R. D. Laing «The Stranger» του Albert Camus «Infants Of The Spring» του Wallace Thurman «The Quest For Christa T» της Christa Wolf «The Songlines» του Bruce Chatwin «Nights At The Circus» της Angela Carter «The Master And Margarita» του Mikhail Bulgakov «The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie» της Muriel Spark «Lolita» του Vladimir Nabokov «Herzog» του Saul Bellow «Puckoon» του Spike Milligan «Black Boy» του Richard Wright «The Great Gatsby» του F. Scott Fitzgerald «The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea» του Yukio Mishima «Darkness At Noon» του Arthur Koestler «The Waste Land» του T.S. Eliot «McTeague» του Frank Norris «Money» του Martin Amis «The Outsider» του Colin Wilson «Strange People» του Frank Edwards «English Journey» του J.B. Priestley «A Confederacy Of Dunces» του John Kennedy Toole «The Day Of The Locust» του Nathanael West «1984» του George Orwell

«The Life And Times Of Little Richard» του Charles White «Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: The Golden Age of Rock» του Nik Cohn «Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music» του Greil Marcus «Beano» (κόμικ των 1950s) «Raw» (κόμικ των 1980s) «White Noise» του Don DeLillo «Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm And Blues And The Southern Dream Of Freedom» του Peter Guralnick «Silence: Lectures And Writing» του John Cage «Writers At Work: The Paris Review Interviews» σε επιμέλεια του Malcolm Cowley «The Sound Of The City: The Rise Of Rock And Roll» του Charlie Gillett «Octobriana And The Russian Underground» του Petr Sadecky «The Street» της Ann Petry «Wonder Boys» του Michael Chabon «Last Exit To Brooklyn» του Hubert Selby, Jr. «A People’s History Of The United States» του Howard Zinn «The Age Of American Unreason» της Susan Jacoby «Metropolitan Life» της Fran Lebowitz «The Coast Of Utopia» του Tom Stoppard «The Bridge» του Hart Crane «All The Emperor’s Horses» του David Kidd «Fingersmith» της Sarah Waters «Earthly Powers» του Anthony Burgess «The 42nd Parallel» του John Dos Passos «Tales Of Beatnik Glory» του Ed Sanders «The Bird Artist» του Howard Norman «Nowhere To Run: The Story Of Soul Music» της Gerri Hirshey «Before The Deluge» του Otto Friedrich «Sexual Personae: Art And Decadence From Nefertiti To Emily Dickinson» της Camille Paglia «The American Way Of Death» της Jessica Mitford «In Cold Blood» του Truman Capote «Lady Chatterley’s Lover» της D. H. Lawrence «Teenage» του Jon Savage «Vile Bodies» της Evelyn Waugh «The Hidden Persuaders» του Vance Packard «The Fire Next Time» του James Baldwin «Viz» (κόμικ των 1980s) «Private Eye» (σατυρικό περιοδικό των 1960s και των 1980s) «Selected Poems» του Frank O’Hara «The Trial Of Henry Kissinger» του Christopher Hitchens «Flaubert’s Parrot» του Julian Barnes «Le Chants de Maldordor» του Comte de Lautréamont «On The Road» του Jack Kerouac «Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder» του Lawrence Weschler «Zanoni» του Edward Bulwer-Lytton «Transcendental Magic: Its Doctine and Ritual» του Éliphas Lévi «The Gnostic Gospels» της Elaine Pagels «The Leopard» του Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa «Κόλαση» του Δάντη «A Grave for a Dolphin» του Alberto Denti di Pirajno «The Insult» by Rupert Thomson «In Between the Sheets» του Ian McEwan «A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1890-1924» του Orlando Figes «Journey Into the Whirlwind» της Eugenia Ginzburg

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If you’re going to join a book club, why not Bowie’s? His favorite 100 books in no particular order:

Interviews With Francis Bacon by David Sylvester

Billy Liar by Keith Waterhouse

Room At The Top by John Braine

On Having No Head by Douglass Harding

Kafka Was The Rage by Anatole Broyard

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess

City Of Night by John Rechy

The Brief Wondrous Life Of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

Iliad by Homer

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

Tadanori Yokoo by Tadanori Yokoo

Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin

Inside The Whale And Other Essays by George Orwell

Mr. Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood

Halls Dictionary Of Subjects And Symbols In Art by James A. Hall

David Bomberg by Richard Cork

Blast by Wyndham Lewis

Passing by Nella Larson

Beyond The Brillo Box by Arthur C. Danto

The Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes

In Bluebeard’s Castle by George Steiner

Hawksmoor by Peter Ackroyd

The Divided Self by R. D. Laing

The Stranger by Albert Camus

Infants Of The Spring by Wallace Thurman

The Quest For Christa T by Christa Wolf

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin

Nights At The Circus by Angela Carter

The Master And Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Herzog by Saul Bellow

Puckoon by Spike Milligan

Black Boy by Richard Wright

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea by Yukio Mishima

Darkness At Noon by Arthur Koestler

The Waste Land by T.S. Elliot

McTeague by Frank Norris

Money by Martin Amis

The Outsider by Colin Wilson

Strange People by Frank Edwards

English Journey by J.B. Priestley

A Confederacy Of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

The Day Of The Locust by Nathanael West

1984 by George Orwell

The Life And Times Of Little Richard by Charles White

Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom: The Golden Age of Rock by Nik Cohn

Mystery Train by Greil Marcus

Beano (comic, ’50s)

Raw (comic, ’80s)

White Noise by Don DeLillo

Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm And Blues And The Southern Dream Of Freedom by Peter Guralnick

Silence: Lectures And Writing by John Cage

Writers At Work: The Paris Review Interviews edited by Malcolm Cowley

The Sound Of The City: The Rise Of Rock And Roll by Charlie Gillete

Octobriana And The Russian Underground by Peter Sadecky

The Street by Ann Petry

Wonder Boys by Michael Chabon

Last Exit To Brooklyn By Hubert Selby, Jr.

A People’s History Of The United States by Howard Zinn

The Age Of American Unreason by Susan Jacoby

Metropolitan Life by Fran Lebowitz

The Coast Of Utopia by Tom Stoppard

The Bridge by Hart Crane

All The Emperor’s Horses by David Kidd

Fingersmith by Sarah Waters

Earthly Powers by Anthony Burgess

The 42nd Parallel by John Dos Passos

Tales Of Beatnik Glory by Ed Saunders

The Bird Artist by Howard Norman

Nowhere To Run: The Story Of Soul Music by Gerri Hirshey

Before The Deluge by Otto Friedrich

Sexual Personae: Art And Decadence From Nefertiti To Emily Dickinson by Camille Paglia

The American Way Of Death by Jessica Mitford

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

Lady Chatterly’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence

Teenage by Jon Savage

Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh

The Hidden Persuaders by Vance Packard

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

Viz (comic, early ’80s)

Private Eye (satirical magazine, ’60s – ’80s)

Selected Poems by Frank O’Hara

The Trial Of Henry Kissinger by Christopher Hitchens

Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes

Maldodor by Comte de Lautréamont

On The Road by Jack Kerouac

Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonders by Lawrence Weschler

Zanoni by Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Transcendental Magic, Its Doctine and Ritual by Eliphas Lévi

The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels

The Leopard by Giusseppe Di Lampedusa

Inferno by Dante Alighieri

A Grave For A Dolphin by Alberto Denti di Pirajno

The Insult by Rupert Thomson

In Between The Sheets by Ian McEwan

A People’s Tragedy by Orlando Figes

Journey Into The Whirlwind by Eugenia Ginzburg

If the title’s in bold we’ve got a copy of it in store. Pretty much everything else is orderable at some discount to it’s cover price. This guy had good taste. And yes, there is an Antonio Banderas version of that ‘Read’ poster hanging on our Main St bathroom door. Price of admission, folks.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

july:

of mice and men by john steinbeck

the vanishing half by brit bennett

the argonauts by maggie nelson

my policeman by bethan roberts

homegoing by yaa gyasi

daisy jones & the six by taylor jenkins reid

august:

trick mirror: reflections on self-destruction by jia tolentino

chosen poems, old and new by andre lorde

drive your plow over the bones of the dead by olga tokarczuk

ellen foster by kaye gibbons

september:

eileen by ottessa moshfegh

the book thief by markus zusak

october:

the blacker the berry by wallace thurman

wow, no thank you: essays by samantha irby

desolation angels by jake kerouac

november:

fleabag: the scriptures by phoebe waller-bridge

december:

crying in h mart by michelle zauner

the sun also rises by ernest hemingway

ready player one by ernest cline

devotion by patti smith

moshi moshi by banana yoshimoto

venus in furs by leopold von sachet-masoch

convenience store woman by sayaka murata

simple passion by annie ernaux

beach read by emily henry

slow days, fast company by eve babitz

the midnight library by matt haig

2021: a year in books i read

january:

salvage the bones by jesmyn ward

the stranger by albert camus

february:

dr. jekyll and mr. hyde & other strange tales by robert louis stevenson

the art of loving by erich fromm

a wrinkle in time by madeleine l’engle

march:

the art book by phaidon press

conversations with friends by sally rooney

tell me more: stories about the 12 hardest things i’m learning to say by kelly corrigan

asleep by banana yoshimoto

everything i know about love by dolly alderton

giovanni’s room by james baldwin

april:

the bluest eyes by toni morrison

all about love by bell hooks

little weirds by jenny slate

if beale street could talk by james baldwin

may:

slaughterhouse five by kurt vonnegut

little book of gucci by karen homer

little book of prada by laia farran graves

little book of dior by karen homer

red white and royal blue by casey mcquiston

june:

a new earth: awakening to your life’s purpose by eckhart tolle

on earth we’re briefly gorgeous by ocean vuong

fleabag by phoebe waller bridge

the song of achilles by madeline miller

the coming insurrection by the invisible committee

life by keith richards

such a fun age by kiley reid

eleven minutes by paulo coelho

#final count#i did not meet me goodreads goal but i read more than last year so i’m calling that a success#nov vs dec is a trip lol#books#g talks#and yes i read the original fleabag play AND the show scripts i love pwb

2 notes

·

View notes