A timeline of the formation of LGBT ballroom culture in New York City and its migration to Paris, London and Berlin. Fall 2019/WGSS 29007.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Video

youtube

Highlights from the Tit Bit Ball IV as a part of the Berlin Voguing Out Festival, a vogue festival which runs every year in Berlin. The video features Sophie Saint Laurent.

Credit: de Quinze (2015) Berlin Voguing Out 2015 - Tit Bit Ball IV.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Berlin may be one of the most recent capitals to embrace and create a ballroom culture in its city with, according to Jakob Balenciaga, the first-ever ball in Germany taking place in 2012 (2018). Although there had been voguing classes being taught as early as 2009, there was no scene for LGBT people to take part in. Georgina, or known as Mother Leo Melody, is credited as the pioneer of German ballroom culture. Vogue teacher and ballroom participant, Sophie Saint Laurent explains that ‘she started the first Vogueing house in Germany, House of Melody and threw the first functions and balls, panel discussions and workshops’ (2019) which eventually grew the community.

The ballroom community has grown so quickly in berlin that it is now a close second to the unofficial capital of European voguing, Paris. Jakob continues in an interview by saying, ‘I am just happy to see that we are finally at a point where we get recognised. It’s been six years since the first ball and a lot has happened — we’ve come from not knowing what we are doing to actually forming a functional scene. [..] Everybody should aim to bring something different — that’s what keeps you relevant. The amount of creativity and work that is being put into walking or throwing a ball is crazy. It’s not for everyone. I guess, being the first person to walk and win “realness” and thereby starting a completely new branch of categories in Germany already brought something different. But actually, I just want to continue spreading the culture and continue educating the youth. Most importantly, I [want to] have fun’ (2018).

Shepherd, Harriet (2018) The fierce voguers setting Berlin’s ballroom scene on fire. Sleek. Available at: <https://www.sleek-mag.com/article/voguing-diesel/>, accessed 30 November 2019.

USC (2019) WELCOME TO BERLIN’S BALLROOM SCENE: VOGUEING // URBAN SPORT OF THE WEEK. Urban Sports Club. Available at: <https://blog.urbansportsclub.com/en/welcome-to-berlins-ballroom-scene-vogueing-urban-sport-of-the-week-english-version/>, accessed 30 November 2019.

Photo 1: Koone Kuhnert, Denis (2016) Two men during a Berlin ball. Image courtesy of iheartberlin.de.

Photo 2: Unknown (2015) Georgina Leo Melody, Co-founder of Berlin Voguing out and House of Melody Mother. Image courtesy of Vice.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

A look into the Jay Jay Revlon ball, ‘DenimBallPt2′ held at the nightclub Fabric in London.

Credit: Shintai, Anthony (2019) Jay Jay Revlon presents DenimBallPt2 | by Anthony Shintai.

0 notes

Photo

Much like Paris, the growing presence of ballroom in London has been a recent one. Hayley Joyes notes that even though ‘Les Child formed the UK’s first vogue house – House of Child – in the late ‘80s’ (n.d.), the scene has stayed very small and underground for decades. However, when Jack Mizrahi, mother of the house of Mizrahi, first arrived in London in 2007 along with other elders of the ballroom community, ballroom started to grow more within the city. Andrew Londyn in his article noted that Mizrahi had said ‘the black gay men of London were afraid to show their feminine side. [..] they’d watch him and others closely but would be hesitant to imitate the feminine gestures and poses of vogueing’ (Londyn 2017). Despite the hesitant start, ballroom slowly continued to expand across London and attract participants, Mizrahi coming back often to MC for many of the balls.

In recent years, Jay Jay Revlon has been credited to keeping the London ballroom scene alive, with successfully creating spaces for ballroom since 2015. Some of which include: UK Queer Men of Colour, Let’s Have a KiKi, Guys That Nail it and Noir (Echo Location Talent). He also has the ballroom collective ‘English Breakfast London’ to his name and has hosted vogue workshops in institutions like Tate Britain and the Southbank Centre (Joyes n.d.).

When interviewed by Tom Rasmussen, father of the house of Milan, Benjamin Milan, said that ‘The biggest scene in Europe is in Paris and I feel like it’s like the heartbeat for the rest of the scenes. [..] In the last three or four years, [London ballroom] really had a boom. [..T]here's four or five main houses. There's the House of West, which used to be the House of Khan, there's the House of Milan, House of Revlon and House of Commes de Garçon, and there are also people from the House of Aviance, the House of Ninja, the House of Amazon, and the House of Prodigy. There's a lot of houses represented, but I feel like the scene here is still young and we are slowly but steadily growing’ (2018).

Jay Jay Revlon n.d. Echo Location Talent, <https://echolocationtalent.com/artists/jay-jay-revlon/> accessed 25 November 2019.

Londyn, Andrew (2017) London Is Burning! How Ballroom Culture Is Flourishing Abroad. Huffpost, <https://www.huffpost.com/entry/london-is-burning-how-queer-ballroom-culture-flourishes_b_5a2e660ce4b04e0bc8f3b682> accessed 25 November 2019.

Rasmussen, Tom (2018) Get to know the UK Ballroom scene, from the voguers at its heart. Dazed, <https://www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/41417/1/ballroom-scene-voguing-gareth-pugh-judy-blame-ball-london-fashion-week-ss19> accessed 26 November 2019.

Joyes, Hayley n.d. A guide to London’s ballroom scene, by voguing sensation Jay Jay Revlon. Redbull, <https://www.redbull.com/gb-en/london-ballroom-culture-guide-jay-jay-revlon> accessed 26 November 2019.

Photo 1: Unknown n.d. Jay Jay Revlon. Image courtesy of Echo Location Talent.

Photo 2: Morrison, David (2018) Participant at the Judy Blame ball. @dcmorr.

Photo 3: Morrison, David (2018) Benjamin Milan at the Judy Blame ball. @dcmorr.

0 notes

Video

youtube

The first of a five-part series featuring Lasseindra Ninja and Steffie Mizrahi about how ballroom moved to Paris and explaining the elements and origins of the culture (English subtitles available).

Credit: Hornet France (2017) Voguers of Paris (1/5), chapter 1: Origin.

#ballroom#house ballroom#lgbt ballroom#voguing#paris#queer#queer history#lasseindra ninja#steffie mizrahi#video

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Although Tim Lawrence cited that 19th-century French masquerade balls were an early influence on the drag balls that grew out of the Harlem Renaissance (Gaestel 2019), and there has been the presence of drag queens and queer community in Paris for decades, the rise of the more modern ballroom scene in Paris in particular can be credited to two French house mothers, Lasseindra Ninja and Steffie Mizrahi.

Ninja met Mizrahi in 2009 in a Paris nightclub. They had both lived in New York during the 1990s and was active in the ballroom culture there. Ninja had been competing in hip-hop festivals and attempted to bring the style of vogue to those settings without luck or interest from others. When the two met, they worked on creating a present and thriving ballroom community there. When interviewed by Allyn Gaestel, Mizrahi commented that ‘you don’t go to vogue at hip-hop festivals, because you will suffer prejudice and being misunderstood, [..] you vogue at a ball’ (2019). For the next few years, the two worked on educating young black queer youth in Paris of the culture created in New York to much success.

It seems, similarly to New York ballroom, that Paris ballroom grew in spaces where LGBT individuals are in need of community. With it being reported that ‘many queer black and Arab youths — especially those from Paris’s “less affluent and religiously conservative suburbs” — have taken to seeing voguing as a way to express their racial and sexual identities without repercussions. “When they were lining the streets in France with angry anti-gay marriage signs, the others were expressing themselves with dance on the Vogue runway,” says one French dancer named Marion Tiger Melody. “The increased popularity of the (far-right) National Front must have had an impact,” she adds.’ (Flagrant).

Gaestel, Allyn (2019), Paris Is Burning’ Goes Global [online text], New York Times <https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/29/style/paris-is-burning-queer-ballroom-culture.html>, accessed 18 November 2019.

PARIS IS VOGUING: BALLROOM DANCE RETURNS TO FRANCE AS POLITICAL EXPRESSION [online text], Flagrant <http://weareflagrant.com/paris-voguing-ballroom-dance-returns-france-political-expression/>, accessed 18 November 2019.

Photo 1: Dustin Thierry (2019) Lasseindra Ninja. Image courtesy of The New York Times.

Photo 2: Dustin Thierry (2019) Steffie Mizrahi. Image courtesy of The New York Times.

0 notes

Video

youtube

A montage of footage taken from New York City balls during the 1990s.

Credit: Derek Faces (2012) VOGUE SUPREMACY 90'S BALLROOM STYLE.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From this era of ball culture was birthed two important exposures for the community that made ballroom more well-known.

Paris is Burning directed by Jennie Livingston

One of the most seminal documentaries surrounding the New York ballroom culture in the 1980s was Paris is Burning, directed by Jennie Livingston and was voguing cultures’ breakthrough to the big screen. Titled Paris Is Burning after a ball staged by Paris Dupree and the House of Dupree in 1986, it started to win awards at film festivals of the time. The documentary was one of the first insights into black and Latino drag balls between the years of 1986 and 1989. It provided a mix of ballroom footage, everyday life of the certain members of the community and interviews with ballroom elders including Pepper LaBeija, Dorian Corey and Angie Xtravaganza. The film gave insight into the hopes of many transgender ballroom members of earning money, sex reassignment surgery and assimilating into the wider culture as well as showing the harsh realities of many house members. Venus Xtravaganza, a member of the House of Xtravaganza, describes her anticipation for sex reassignment surgery while working as a prostitute and that one day she might live as a ‘spoiled, rich, white girl living in the suburbs’. However, Venus was subsequently by the end of the film found murdered in a hotel room, strangled with her body left under a bed (Lawrence 2011).

Although the film certainly received praise, it also came with its fair share of criticism. Judith Butler, queer theorist, responded to the film by asking whether ‘the depicted drag queens undermine dominant values around gender and sexuality, showing them to be based on performance rather than some form of essential identity, or whether they effectively reinforce them by placing a high value on the lifestyle and material values of dominant white culture’ (Lawrence 2011). Butler argues that ‘Venus, and Paris Is Burning more generally, calls into question whether parodying the dominant norms is enough to displace them[..] When Venus speaks her desire to become a whole woman, to find a man and have a house in the suburbs with a washing machine, we may well question whether the denaturalisation of gender and sexuality that she performs, and performs well, culminates in a reworking of the normative framework of heterosexuality.’ (Butler 1993:125)

In other responses, critics like Bell Hook argued that Livingston’s power as a white, educated woman over the drag queens she was interviewing was the only reason that this film could be made and have to go to have success. Even saying that, ‘the whiteness celebrated in Paris is Burning is not just any old brand of whiteness, but rather that brutal imperial ruling-class capitalist patriarchal whiteness that presents itself—its way of life—as the only meaningful life there is’ (1992:149).

Vogue by Madonna

In 1990, popular singer Madonna released the single ‘Vogue’ which included many voguers from the New York ballroom scene of the time and became the best-selling single of 1990. The singer released a black and white video for the song that drew on art deco aesthetics and the Golden Age of Hollywood, and featured two Xtravaganza house members, Luis and José, voguing with the star in between shots of Madonna posing in the manner of some of the name-checked movie icons (Lawrence 2011).

Madonna arrived into the voguing scene in order to piece together a cast for the video. David DePino, a DJ for the balls of the time, recounts that ‘[Madonna’s team] set up a meeting with me and Madonna, who came to Tracks when the club was closed to meet and watch some voguers. I had a group of kids there to vogue for her, including some kids from other houses. She picked out who she liked for the video’ (Lawrence 2011). She frequently visited many of the clubs that held balls at the time and went on to hire José and Luis as backing dancers for her critically acclaimed ‘Blond Ambition’ tour; featured in Madonna’s behind-the-scenes documentary of the tour; and continued to take voguing around the world.

However, Lawrence notes that ‘although they reaped very different rewards, both Madonna and Livingston were accused of ransacking drag ball culture for their own ends, and for benefiting from their engagements with ball culture and voguing in a much more explicit way than the participants they maintained they had helped’ (2011). After the tour, Madonna didn’t return to the clubs that she had become frequent to. Terre Thaemlitz, who was part of the ball scene, explained the effect the single left on the community: ‘when Madonna came out with [‘Vogue’] you knew it was over. She had taken a very specifically queer, transgendered, Latino and African-American phenomenon and totally erased that context with her lyrics, [..] Madonna was taking in tons of money, while the Queen who actually taught her how to vogue sat before me in the club, strung out, depressed and broke’ (2008).

Queens who had also worked with Livingston also started to criticise Livingston after the release of the documentary. Pepper LaBeija saying that ‘when Jennie first came, we were at a ball, in our fantasy, and she threw papers at us[..] We didn’t read them, because we wanted the attention. We loved being filmed. Later, when she did the interviews, she gave us a couple hundred dollars. But she told us that when the film came out we would be all right. There would be more coming. [..] But then the film came out and—nothing. They all got rich, and we got nothing’ (Green 1993). LaBeija did later go on to praise the film, however, crediting it as her rise to fame.

Despite the criticism both medias received, they also received a lot of support and love from the community and are often considered seminal to the history of New York ballroom.

Butler, Judith (1993) Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion. In Bodies That Matter, ed. Judith Butler, London: Routledge, pp. 121 - 140.

Green, Jesse (1993) Paris Has Burned. New York Times.

Hooks, Bell (1992) Is Paris Burning? In Black Looks: Race and Representation, ed. Bell Hooks, New York: Routledge, pp. 145-156.

Lawrence, Tim (2011). ‘Listen, and You Will Hear all the Houses that Walked There Before’: A History of Drag Balls, Houses and the Culture of Voguing. London: Soul Jazz.

Thaemlitz, Terre (2008) Ball’r (Madonna-Free Zone). Comatonse Recordings.

Photo 1: Unknown n.d. Photograph of Madonna, Willi Ninja and Jennie Livingston at a showing of Paris is Burning. Image courtesy of medium.com.

Photo 2: Livingston, Jennie (1986) Venus Xtravaganza, Brooklyn ball. Courtesy of Jennie Livingston.

Photo 3: Unknown n.d. Madonna performing on her ‘Blond Ambition’ tour. Image courtesy of GettyImages.

Photo 4: Still from Madonna’s music video of ‘Vogue’ including young voguers José Gutierez and Luis Xtravaganza. Can be found at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GuJQSAiODqI

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Clip explaining and demonstrating the different elements of voguing.

Murray, Ronald (2019) Ballroom Culture: the Language of Vogue | Ronald Murray | TEDxColumbus. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QS5j7PCSdtg&list=PLlzB96alJHIN8bJaL4RvbmD5YGyt2AT1B&index=8&t=719s (accessed 29th November).

1 note

·

View note

Video

tumblr

With the origination of balls as a space for drag queens and transvestites to show off and compete for highest beauty amongst each other, by the 1970s and 80s the balls began to change and expand to cater for all people in the community. As Pepper LaBeija, former house mother of the house of LaBeija explains, ‘[houses started making] the categories for everybody [..] so there was more involvement’ (1990). This introduced the concept of ‘realness’; the ability in which to ‘blend’ in with your heterosexual and/or cisgender counterpart: ‘it’s really a case of going back into the closet’ (Dorian 1990). Realness was born from the question of whether a member of a house could provide for the others; ‘unless someone is ‘real’ enough to keep a 9 to 5 [job, many houses would not] have enough food or be able to pay legally for people to survive until the next ball’ (LaBeija 2019). These categories would, therefore, allow for all individuals to compete as and perform a status or privilege which were largely unattainable to many due to their economic and racial status within society. The balls offered an opportunity to exercise greater agency in shaping how they are viewed by altering and performing their bodies in ways that disguise their gender and sexual nonconformity.

The balls also originated the dance style, ‘Vogue’: as previously mentioned, used as a form of settling disagreements amongst houses, instead of fighting, individuals would compete by dancing. With the style of dance originating from the fashion magazine of the same name, the dance mimics many of the shapes and poses that models from Vogue photoshoots would do and the formation of the style credited to Willi Ninja, former mother of the house of Ninja and known as ‘Godfather of Voguing’. Within voguing, there are many different elements which have evolved including: Hands,, Catwalk,, Duckwalk, Floor performance, and, Spins and Dips (see).

These forms of performance and dance cannot be disassociated from the also political statements in which they originate from, as P. B. Harper explains:

‘It is easy enough to identify the constituent factors in the reputed subversiveness of ball culture. Jim Farber's own formulation makes it quite clear that it is the demonstration of the "mutability of identity"-effected in particular through ball contestants' achievement of Realness-that provides the requisite "edge" to the culture's socio-political significance. According to John Howell, that demonstration inevitably raises the questions: "[W]hat is authentic in social roles? Who does our culture reward and who does it exclude, and how different are they? What is male, what is female? Can our chromosomal hard-wiring be reprogrammed?". Howell's identification of these as "bottom-line questions" implies that the mere posing of them is a radical political act; and since, according to Howell, it is "voguing" itself that thus "leads us to deep issues," ball practice emerges, in his rendering, as the clear agent of subversive critique.’ (Harper 1994:91).

Corey, Dorian (1990) Interviewed by Jennie Livingston. In Paris is Burning [DVD]. New York: Off-White Productions.

Harper, Phillip Brian (1994) The Subversive Edge: Paris Is Burning, Social Critique, and the Limits of Subjective. In Diacritics, vol. 24, no. 2/3, pp. 90- 103.

LaBeija, Pepper (1990) Interviewed by Jennie Livingston. In Paris is Burning [DVD]. New York: Off-White Productions.

Video: Livingston, Jennie (1990) Paris is Burning. Clips showing Willi Ninja and other members of the drag ball community breaking down the origins of ‘voguing’. New York: Off-White Productions.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

As well as rejection from immediate family and pathologized from wider society, ballroom grew from prominently Afro-American and Latin-American transgender individuals who were also facing rejection from the rest of the queer community. Deriving from the term ‘transvestite’ first coined by Magnus Hirschfeld in his book ‘The Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress’ in 1910 in Berlin, Susan Stryker uses Hirschfeld’s term when explaining in her essay, ‘(De)Subjugated Knowledges: An Introduction to Transgender Studies’ how ‘transgender’ has changed and evolved throughout the following decades:

‘If a transvestite was somebody who episodically changed into the clothes of the so-called “other sex,” and a transsexual was somebody who permanently changed genitals in order to claim membership in a gender other than the one assigned at birth, then a transgender was somebody who permanently changed social gender through the public presentation of self, without recourse to genital transformation’ (Stryker 2006:04).

‘Transgender’ grew as the predominant term of choice by the 1990s. ‘Transgender, in this sense, was a “pangender” umbrella term for an imagined community encompassing transsexuals, drag queens, butches, hermaphrodites, cross-dressers, masculine women, effeminate men, sissies, tomboys, and anybody else willing to be interpolated by the term, who felt compelled to answer the call to mobilization’ (Stryker 2006:04). The nature of ballroom, therefore, attracted many transgender people who were being left out of the many sexual liberation movements of the time and people of colour who were still suffering under a continually white-dominant society. With members of many queer organizations and networks during the 1993 March on Washington for Gay, Lesbian and Bi Rights explicitly voted not to include transgender’ in the title (Stryker 2006:05), ballroom and houses started becoming a place of political activism for the civil rights and gay liberation movements, and the fight against AIDS. Many transgender women and drag queens occupied the frontline during the Stonewall rebellion of June 1969, including the more famous names of Sylvia Ray Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson.

Hirschfeld, Magnus (1910) The Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress, translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1991). New York: Prometheus Books.

Stryker, Susan (2006) (De)Subjugated Knowledges: An Introduction to Transgender Studies. In The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, pp. 01-17.

Photo 1: Kay, Tobin (1970) Sylvia Rivera in front of fountain. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Photo 2: Davies, Diana (1969) Gay Liberation Front Marsha P. Johnson demonstrates at City Hall, New York. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Photo 3: Wandel, Rich (1970). Sylvia Rivera of STAR (Street Transvestites Action Revolutionaries) at Bellevue Hospital demonstration, Fall 1970. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

Photo 4: Davies, Diana (1968) Marsha P. Johnson pickets Bellevue Hospital to protest treatment of street people and gays. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library.

31 notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

Clip of Crystal LaBeija expressing tiredness of the anti-black bias of the balls at the Miss All-American Camp Beauty Pageant drag contest after host Flawless Sabrina announced that white drag queen, Harlow had won, declaring it to be a fix. LaBeija and others competed in front of a panel that included Larry Rivers and Andy Warhol. The experience prepared the way for LaBeija’s collaboration with Lottie.

Simon, Frank (1968) The Queen. New York: Grove Press.

190 notes

·

View notes

Photo

With the interruption of World Wars and prohibition, the Harlem queer and art scene dove back into darkness for some decades. However, as John D’Emilio refers from Allan Bérubé that ‘the war years were critical in the formation of a gay male community in [New York] city’ (1993:472). The war allowed for a temporary space for gay men (and women) to find community more easily, away from the strict heterosexual bounds. Steadily gay communities started to become more visible; ‘throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the gay subculture grew and stabilized so that people coming out then could more easily find other gay women and men than in the past’ (1993:472). However, night life scholar Tim Lawrence explains that ‘officers responded by intensifying their regulation and cases of entrapment (whereby police officers would ‘entrap’ gay men through sexual solicitation before producing their badge) increased exponentially’ (2011). Yet the police struggled to minimise the ever-growing presence of drag balls and homosexual activity, with an increase of gay men who, after the second world war, travelled through Manhattan on their way to the battlefront returned to the city (2011).

By the early 1960s, drag ball culture had begun to splinter along racial lines. Although the balls of the 1920s and the end of 1930s had started to see a notable mix of black and white participants, black queens were gradually finding that they were expected to ‘whiten up’ their faces in order to have a chance of winning the contests over the white queens. Therefore, black queens started to stage their own events, with Marcel Christian staging what is known to be the first all-black ball in 1962 (Lawrence 2011).

Ballroom culture as it’s more recognised nowadays started to appear in 1972. ‘House culture’ began when a Harlem drag queen named Lottie, ask another drag queen, Crystal LaBeija, to co-promote a ball. LaBeija at the time expressing her frustration at the anti-black bias of the balls and as one of the only black queens to be awarded a Queen of the Ball title at a white-organised ball agreed to work with Lottie. Terrence Legend International noted that ‘Lottie made the deal sweeter by convincing Crystal that they should start a group and name it the House of LaBeija, with Crystal’s title as “mother”’ (Lawrence 2011) The event was therefore named ‘Crystal & Lottie LaBeija presents the first annual House of LaBeija Ball at Up the Downstairs Case on West 115th Street & 5th Avenue in Harlem, NY’ (Lawrence 2011).

Throughout the following years, many more houses were born and grew as safe spaces for individuals that were rejected and dejected from the family home and provided people with their own nuclear family structure with a mother and father at the top. Ronald Murray explains that ‘the expression of the house culture became the ballroom’ (Murray 2019); wanting to express the proudness they felt for their house, they used ‘drag balls like “gay street gangs on the dance floor” creating new styles like voguing’ in order to solve arguments of difference between the houses and prove theirs were the best (Balzer 2005:115).

Balzer, Carsten (2005) The Great Drag Queen Hype: Thoughts on Cultural Globalisation and Autochthony. In Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde, Bd. 51, pp. 111-131.

D’Emilio, John (1993) Capitalism and Gay Identity. In The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. Henry Abelove, Michèle Aine Barale and David M. Halperin. New York: Routledge, pp. 467-476.

Murray, Ronald (2019) Ballroom Culture: the Language of Vogue | Ronald Murray | TEDxColumbus. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QS5j7PCSdtg&list=PLlzB96alJHIN8bJaL4RvbmD5YGyt2AT1B&index=8&t=719s (accessed 29th November).

Lawrence, Tim (2011) ‘Listen, and You Will Hear all the Houses that Walked There Before’: A History of Drag Balls, Houses and the Culture of Voguing. London: Soul Jazz.

Photo 1: Chantal Regnault. Group of men at a New York ball. Image courtesy of Soul Jazz Books.

Photo 2: Unknown n.d. Drag queen competing in Harlem drag ball. Image courtesy of Everett Collection.

Photo 3: Chantal Regnault. Ball judges giving their scores to a contestant. Image courtesy of Soul Jazz Books.

Photo 4: Crystal LaBeija (left) in a still from The Queen (1968), directed by Frank Simon. Image courtesy of Grove Press/Photofest.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Queer Figures of the Harlem Renaissance

Gladys Bentley

Gladys Bentley was a blues singer who thrived during the Harlem Renaissance during the 20s and early 30s, becoming known as Harlem’s favourite ‘bulldagger’ and was known to have many female lovers during her life. Often singing controversial songs and known as a male impersonator for dressing in white tuxedos and top hats, she frequently performed and headlined at the famous gay speakeasy, The Clam House. Around 1930, Bentley married a white woman in Atlantic City, New Jersey. But later, Bentley went back in the closet and her all-too-brief period of fame ended in the 1930s. Ultimately, homophobia, uniting with racism, sexism, and classism, destroyed Bentley’s ability to live creatively and freely and she drew back into the closet and claimed to marry a man who denied ever being married to Bentley (Wilson 2010).

Richard Bruce Nugent

Richard Bruce Nugent was one of the few publicly out queer artists of the Harlem Renaissance and was as the ‘perfumed orchid of the New Negro Movement’ (Glick 2009:86). Nugent was known to have lived with another queer writer Wallace Thurman from the years 1926 to 1928 in Harlem, which led to the publishing of the story ‘Smoke, Lilies, and Jade’ in Thurman's black literary publication Fire!!. The story covered themes of bisexuality and more explicitly interracial male desire. Despite his openness about male attraction, Nugent married Grace Marr in 1952 until her suicide in 1969 (Wirth 2002).

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker was a well-known singer, dancer and actress within the early years of the Harlem Renaissance. However, she struggled to find an audience within the US and predominantly grew her large career overseas in Paris. Because of this, she is often known as the first Black international star. Her song, ‘J’ai Deux Amours,’ meaning ‘I have two loves,’ became one of her biggest, in which Baker took to mean France and the United States (Goodman 2019). Baker identified herself as bisexual. She married four different times throughout her life but carried on affairs with women, including Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and French author Colette.

Langston Hughes

One of the most well-known and written about, poet, novelist and playwright, Langston Hughes, was a primary voice of the Harlem Renaissance. Although Hughes never spoke of his sexuality often in public, there are a lot of homosexual themes in his work such as ‘Blessed Assurance’ and ‘Seven People Dancing.’ Garber wrote that ‘Hughes was exceedingly cagy and evasive about his emotional involvements, even with his closest friends; as a result, though most of Hughes' biographers concede that the poet was at least sporadically homosexual, the exact nature of his sexuality remains uncertain’ (1990:326). He also often attended and was fond of the Harlem drag balls, naming them the infamous ‘spectacles of colour’.

As professor Henry Louis Gates describes, the Harlem Renaissance was, ‘surely as gay as it was black’ (1993:233). With the growth in art, jazz and blues, and drag balls, this time period was defined as ‘homosexual mecca’ or queer paradise and can be seen to have had many other LGBTQ artists that led the Harlem Renaissance. Some of the famous names including Countee Cullen, Ethel Waters, Ma Rainey, Claude Mckay, Alain Locke, Bessie Smith, James Richmond Barthé, Alberta Hunter, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, and Angelina Weld Grimké.

Gates, Henry Louis (1993) The Black Man’s Burden. In Fear of a Queer Planet: Queer Politics and Social Theory ed. Michael Warner, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 230-238.

Glick, Elisa (2009) Materializing Queer Desire: Oscar Wilde to Andy Warhol. Albany: State University Press.

Jules-Rosette, Bennetta (2007) Josephine Baker in Art and Life. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Schwarz, A. B. Christa (2003) Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Wilson, James F. (2010) Bulldaggers, Pansies, and Chocolate Babies: Performance, Race, and Sexuality in the Harlem Renaissance. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Wirth, Thomas H. (2002) Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance. Durham: Duke University Press.

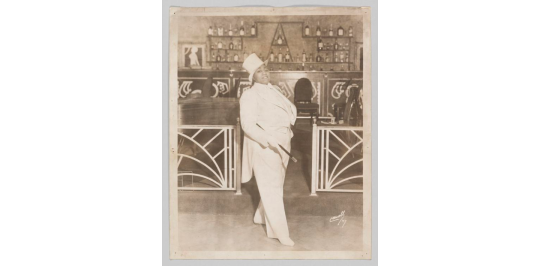

Photo 1: Unknown n.d. A silver gelatin print depicting a black-and-white image of entertainer Gladys Bentley. Bentley is depicted standing in three-quarters profile with her head turned towards the viewer, and her proper right foot forward. She is wearing a white tuxedo, top hat, and she is holding a cane under her proper right arm. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

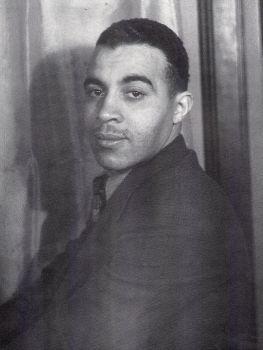

Photo 2: Unknown n.d. Photograph of Richard Bruce Nugent (also Bruce Nugent). Image courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University.

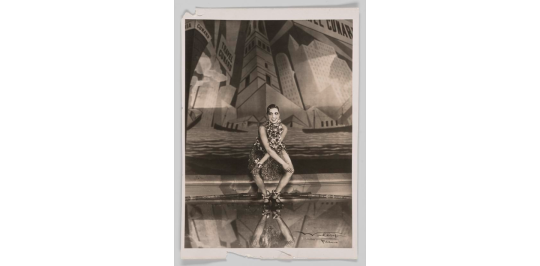

Photo 3: Walery n.d. Photographic print of Josephine Baker performing at the Folies Bergère. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture and National Portrait Gallery, gift from Jean-Claude Baker.

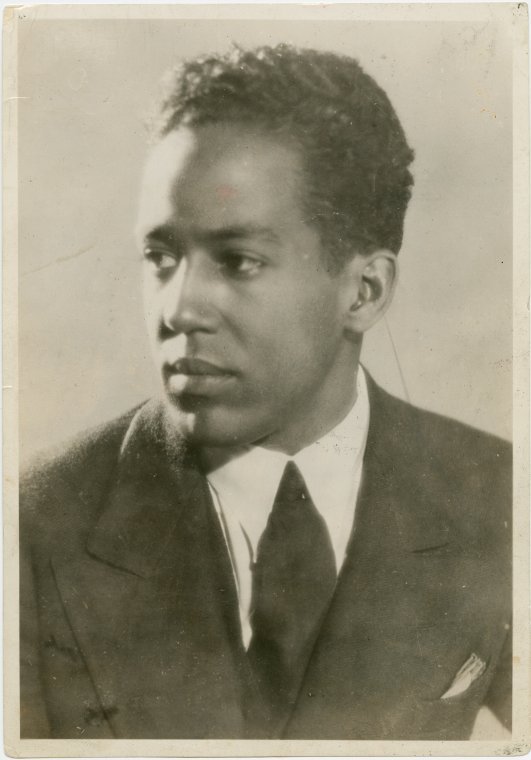

Photo 4: Unknown n.d. Langston Hughes as a young man. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library.

#ballroom#house ballroom#lgbt ballroom#harlem renaissance#queer#gladys bentley#richard bruce nugent#josephine baker#langston hughes#queer history

241 notes

·

View notes

Photo

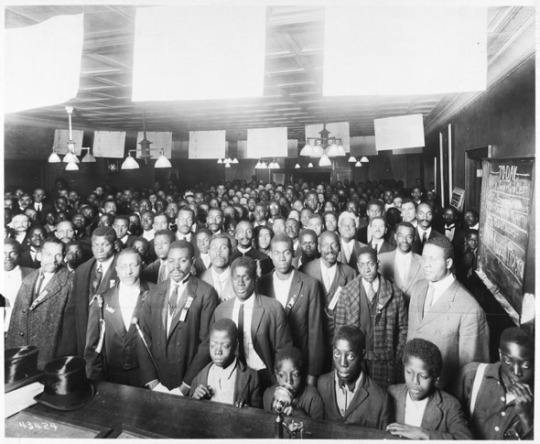

As well as rent parties and buffet flats Harlem birthed the first-ever ‘drag’ or ‘costume’ balls. ‘Decidedly safer [and] where both men and women could dress as they pleased and dance with whom they wished, called "Spectacles in Colour" by poet Langston Hughes, they were attended by thousands’ (Garber 1990:324). However, as years went on the anonymity of the balls started to fade and the ‘spectacle’ of the balls attracted large amounts of white audiences from downtown New York. ‘Too far away to be dangerous yet close enough to be exciting’; white visitors came in search of sexual and homosexual adventures but did not fear social ostracism or the loss of family ties and employment, as they could retain a sexually inconspicuous image in their everyday white environment (Schwarz 2003).

Hamilton Lodge annual balls were ‘the largest annual gathering of lesbian and gay men in Harlem – and the city’ (Chauncey 1995). Running since 1869, the annual ball first started to attract queer participants, most notably because of its acceptance and presence of female impersonators to the event. Soon, what was at one point known as Masquerade and Civic Balls were soon labelled as ‘Faggots Balls’ by a vast majority of the public after the knowledge grew that they were attended by queer people.

Garber also informs of the other venues for such events: ‘only slightly smaller were the balls given irregularly at the dazzling Savoy Ballroom. [..] The organizers would obtain a police permit making the ball, and its participants, legal for the evening. The highlight of the event was the beauty contest, in which the fashionably dressed drags would vie for the title of Queen of the Ball’ (1990:325). The first prize often going to the queen with the sparsest outfit—it was once awarded to a man wearing an apron, silver sandals, apple-green paint, and nothing else (Watson 2001).

But with this growing publicity also grew backlash. A Harlem minister, Adam Clayton Powell, pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church until 1937, campaigned against what he called ‘the growing scourge of sexual perversion and moral degeneracy’. Often referred to by scholars of the time as ‘indeterminates’, ‘third sex’, or ‘degenerates’, many of the black queer figures who attended such events were sent to psychiatric institutions in multitudes; some were also arrested and thrown into reformatories. Augustus Granville Dill, one of the more well-known figures during the time and business editor of the NAACP's Crisis, was arrested and career ended when he was caught participating in homosexual activity in a public restroom in 1928 (Wirth 2002:22).

Chauncey, G. (1994) Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. United States: Basic Books.

Garber, Eric (1990) A Spectacle in Colour: The Lesbian and Gay Subculture of Jazz Age Harlem. In Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. New York: Penguin, pp. 318 – 331.

Russell, Thaddeus (2008) The Color of Discipline: Civil Rights and Black Sexuality. In American Quarterly, vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 101-128.

Schwarz, A.B. Christa (2003) Gay Voices of the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Watson, Steven (2001) Hub of African-American Culture. In Harlem Renaissance, ed by Christine Slovey and Kelly King Howes. Detroit: Gale.

Wirth, Thomas H. (2002) Gay Rebel of the Harlem Renaissance. Durham: Duke University Press.

Photo 1: Newspaper clipping from The New York Age titled 'Hamilton Lodge Ball an Unusual Spectacle' (1926). Image courtesy of queermusicheritage.com.

Photo 2: Newspaper clipping from The New York Age titled ‘Hamilton Lodge, No. 710 In Annual Masquerade and Civic Ball’ (1927). Image courtesy of queermusicheritage.com.

Photo 3: Newspaper clipping from The New York Age titled ‘Hamilton Lodge Ball is Scene of Splendor’ (1930). Image courtesy of queermusicheritage.com.

Photo 4: Unknown (1939) The Hamilton Lodge Ball. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library.

Photo 5: Unknown (1939) The Hamilton Lodge Ball. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library.

Photo 6: Unknown (1939) The Hamilton Lodge Ball. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library.

Photo 7: Yale, Joel (1949) Contestants Parading for Judges for The Costume Prize During The Urban League Ball at The Savoy Ballroom. Image courtesy of For LIFE Magazine.

Photo 8: Unknown (1937) Savoy Ballroom Marquee. Image courtesy of welcometothesavoy.com.

#ballroom#house ballroom#lgbt ballroom#hamilton lodge#savoy ballroom#harlem renaissance#queer#queer history

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Origins of the ballroom culture that are seen today can be traced back to the 1920s. A seminal reading by Eric Garber wrote that ‘at the beginning of the twentieth century, a homosexual subculture uniquely Afro-American in substance, began to take shape in New York's Harlem. Throughout the so-called Harlem Renaissance period, roughly 1920 to 1935, black lesbians and gay men were meeting each other on street corners, socializing in cabarets and rent parties and worshipping in church on Sundays. Creating a language, a social structure, and a complex network of institutions’ (1990:318). One of these institutions also being, ‘balls’.

Garber goes on to explain that ‘the key historical factor in the development of the lesbian and gay subculture in Harlem was the massive migration of thousands of Afro-Americans to northern urban areas after the turn of the century’ (1990:319). With the large majority of Afro-Americans living in rural southern states at the end of American slavery, one of the most significant shifts in population occurred when many moved to developed northern urban areas with the prospects of factory work, creating large communities of black Americans, also now known as the ‘Great Migration’ (figure one). One of the largest communities formed was in Harlem. With a celebration of progress and possibilities and described as ‘spiritual emancipation’ by Rhodes scholar, Alain Locke, Harlem soon became a centre of black music and art.

Self-named as ‘The New Negros’ (figure two), Garber goes on to explain that ‘[the] movement created a new kind of art. Harlem, as the New Negro Capital, became a worldwide centre for Afro-American jazz, literature, and the fine arts. Many black musicians, artists, writers, and entertainers were drawn to the vibrant black uptown neighbourhood’ (1990:319). And with this art also came a growing homosexual community.

Esther Newton, American cultural anthropologist, argues that ‘homosexual communities are entirely urban and suburban phenomena. They depend on the anonymity and segmentation of metropolitan life’ (1972:21). It could be said that this creation of an urban settlement for black Americans allowed for the anonymous growth of the black homosexual community and for ‘homosexual behaviour’ to become ‘homosexual identity’. This new, young urban artistic setting ‘[..] made possible the formation of urban communities of lesbian and gay men and [..] of a politics based on a sexual identity’ (D’Emilio 1993:470).

D’Emilio, John (1993) Capitalism and Gay Identity. In The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. Henry Abelove, Michèle Aine Barale and David M. Halperin. New York: Routledge, pp. 467-476.

Garber, Eric (1990) A Spectacle in Colour: The Lesbian and Gay Subculture of Jazz Age Harlem. In Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. New York: Penguin, pp. 318 – 331.

King Howes, Kelly (2001) ‘Yes! It Captured Them ....': The Performing Arts. In Harlem Renaissance, ed. by Christine Slovey and Kelly King Howes. Detroit: Gale, pp. 69-103.

Locke, Alain (1925) Enter the New Negro. In Survey Graphic, vol lll.

Newton, Esther (1972) Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Photo 1: Woodward (1921) Union Terminal Railroad Depot Concourse, black & white photoprint, 8x10 in. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

Photo 2: Unknown (1920) UNIA Parade, organized in Harlem, 1920. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library.

Photo 3: Unknown n.d. Webster Hall hosting a drag ball during the 1920s. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

61 notes

·

View notes