#verified by me . native Japanese speaker

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

To whomever this will benefit, I’ve realized that Pierre might be the only person to pronounce “Tsunoda” accurately (TSU^noda not TsuNOda)

#I meant to say this a while ago but I forgot#yukierre#pierre gasly#yuki tsunoda#verified by me . native Japanese speaker

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

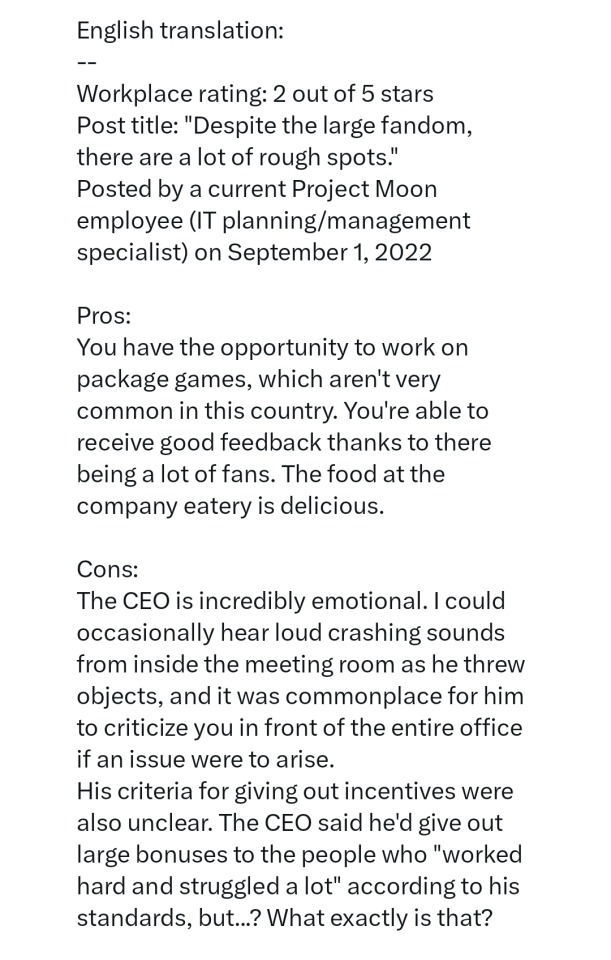

IMPORTANT: Regarding the current PMoon/LCB situation, KJH's history of poor employee treatment

(Edit: Please check my reblog for more employee reviews that were posted to the forum within the past few days.)

As of July 27, 2023 (3 PM PDT), the official LCB Twitter account still hasn't posted English or Japanese translations of the message by Project Moon CEO (Kim Jihoon) announcing their decision to fire story CG artist Vellmori.

In the subsequent chaos following her unjust expulsion, I've seen a significant number of the global fanbase pity KJH/PM and assume that firing Vellmori was a poor but well-intentioned response to protect PM employees.

However, PMoon has long been a less than ideal place to work for both outside contractors (see testimonies from the WonderLab and Leviathan artists) as well as their full-time employees.

Below is a workplace review of Project Moon from September 2022 by a current employee, which talks in depth about KJH's regular temper tantrums in the office and subpar treatment of the PMoon team.

Translation by me, a native Korean speaker. (source here)

This review was posted to a forum that can ONLY be accessed if you have a verified and active employee email address to a game company. While the forum is anonymous, it requires you to reveal your place of employment, which lends credence to its validity.

This, combined with other testimonies, has led people to believe that KJH will not recant his decision, as there's credible evidence that documents his temperamental outbursts, one-sided contract cancellations, and continued refusal to provide a healthy work environment.

TL;DR—Do not pity Kim Jihoon. This situation is shocking, yes—but it is no excuse to coddle a man who refused to protect an innocent employee of his company (knowing it could very well mean death of her future career) just to appease violent misogynists.

#vellmori is only 22 years old btw... and if she worked on the game cgs for at least 1~2 years. that's a BABY#likely her first job ever at a company too... wishing her nothing but the best for the future. work little and earn big 🫡#poca chat#pocasu tls#limbus company#lcb#project moon#kim jihoon

401 notes

·

View notes

Note

thank you and fia for translating that side order interview! i've been dying to learn more about who or what the hell cypher was. inoue mentions that cypher speaks in an "inconsistent and accented manner" due to being influenced by many consciousnesses, which made me curious if there's a difference in its japanese character voice as i found its english one a bit bland - does it, say, mix up several dialects?

Good question! I looked into Cipher's JP dialogue, as well as the impressions from some japanese users online. my impressions from what i could tell in JP was that the way it puts together sentences feels almost robotic, not in a rude way exactly, but in a 'who talks like this' way. Some comments I saw from JP users was that it spoke in a way that felt impersonal, and comparisons of its speaking style to like. a religious leader or nun or something. my impression is the english localization is pretty faithful to the JP in conveying this sense of "who talks like this." maybe cipher comes off as even more weird to native JP speakers in a way that cant be translated thru its dialogue, but im absolutely Not fluent in JP so i cant verify that

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time to brainrot about something I guess since I'm being kept up with a migraine.

Now you probably wouldn't think it from looking at me, but I am actually very, very much deeply obsessed with linguistics. To an unhealthy degree, some might say. And one of my favorite linguistic concepts is "This is a stupidly hilarious pun in Language A, but it makes no sense in Language B" The prime example of this is an old Sumerian/Babylonian joke that at this point has had several thousand video essays written about it. You know the one: "A dog walks into a tavern. 'I can't see anything!' he says. 'I'll open this one.'"

And who could forget the Greek Philosopher Chrysippus? In one of the accounts of his death, it is said that he got a bit too drunk at a party and, upon witnessing a donkey eating figs, he said "someone should get that donkey some pure wine to wash down the figs!". He then fucking died of laughter at his own joke. Beause apparently that was the funniest shit he'd ever seen.

Now neither of those make sense in any living language or modern culture, but the fact that it was written down at all means it made enough people laugh for it to be worth recording. And it's fun to look at living languages and see what makes the native speakers laugh but still utterly baffles everyone else. Even better, digital archeaologists in a thousand years are going to have a field day with this post if they ever stumble upon it, so here are a few of my favorite untranslatable puns: Hungarian: A man is pulled over by the police. The officer asks, "Are you drunk?". The man replies, "No, sir, Ivett is my wife"

Japanese: Why dont Hawaiians go to the dentist? Good teeth.

Finnish: "A bar and a screwdriver". That's the entire joke, by the way. Set up and punchline, apparently both right there, and in the original Finnish it's only two words. Apparently it's a reference to something? I'm just going to assume this is a thing you say and people laugh, much like "omae wa, mou shinderu"

Spanish: What fruit is the most patient? It's a pear. So fun fact, my Aunt is from Mexico, and I decided to tell her this joke in the original Spanish (which as a consequence of having a Mexican aunt, I speak pretty well). And I shit you not that as soon as the words "es pera" left my mouth, she let out the longest, heaviest, most world-weary sigh I have ever heard in my 20 years of life, before returning to the tamales she was making. I guess she now knows that my pun game has transcended to include her native language, and in that moment she was preparing herself for the ensuing decades of Spanish wordplay

Another from Japanese because they are gods of wordplay: "7-Up, Pepsi, Coca-Cola, they're all types of what?" "Soda?" "That's right!"

Chinese: "Who is Mi's mother?" "Hua, because peanuts". I took Chinese in high-school and I can verify that this is the shittiest pun I've ever seen, but the reddit user who posted it says "I am yet to find a single Chinese/Taiwanese person who does not find it hilarious"

Aussie English (which I'm including both for English rep and because Aussie slang is so markedly different that Brits and Americans are still unlikely to get it): "What's the difference between fat and cholesterol? You can't crack a cholesterol".

Danish: One sign says to another, "Are you married?" The other replies, "No, I'm divorced"

AND MY PERSONAL FAVORITE: French: "He wished to be Caesar, but he died as Pompey" -- George Clémenceau, commenting on the death of President Felix Faure (I refuse to explain this one or give any further context, go look it up)

Oh and side note. Obviously, no world leader can speak every language, so interpreters are a necessity for negotiation. And of course, world leaders and diplomats are going to try the lighten the mood occaisionally with humor. But for negotiations between most countries, that's hard to do, because there are very few puns with much cross-linguistic utility. Sure, you have that one joke about where cats go when they die that works in English and most Romance languages, but for some more serious negotiations, the number of puns that would make sense in both languages is pretty close to zero, and may very well BE zero. So the question arises, how do interpreters deal with that? Of course there are a lot of possible methods, not all of which are good or even remotely efficient. You could just translate the pun word for word, but as evidenced by the fact that that's literally what I did above, it's not gonna work that well. Explaining the joke also isn't gonna fly, because as we all know, the second you explain a joke is the seond it becomes Not Funny Anymore. The method I've found that I think works best is just to say "They have said a pun that doesn't translate well to English. Laugh now." Which is funny not just because it works, but because it works amazingly. That person on the other end of the table (who we are assuming doesn't speak a lick of English) has no clue what the interpreter is saying, and so must assume their joke was translated faithfully. Sure, their interpreter might know depending on how the whole thing is set up, but considering the vetting process you have to go through to be an interpreter for the POTUS , I highly doubt anyone is going to risk national security over a joke being left untranslated. Both leaders have a laugh, everything ends on good terms, and we avoid nuclear annihilation for another few weeks.

0 notes

Text

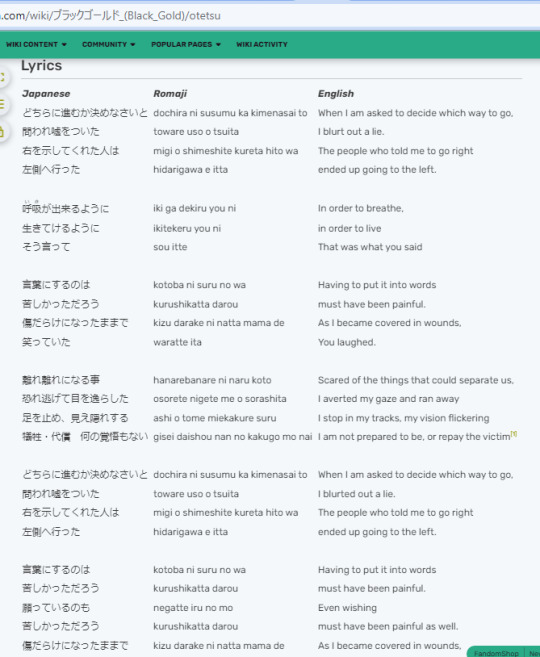

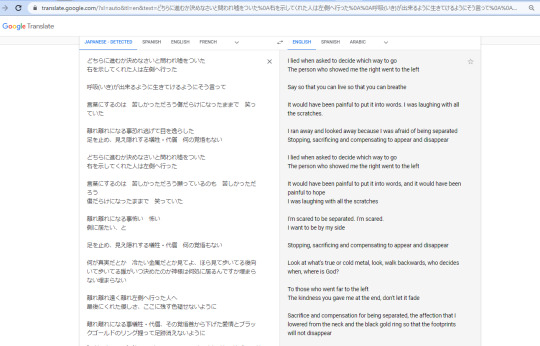

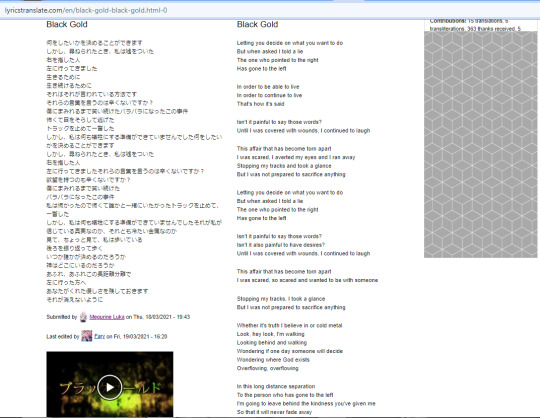

Non-Japanese tries to explain the lyrics of "Black Gold" by otetsu ft. Megurine Luka

Note: I am not a Japanese speaker, so I depend on translation engines, and comments are always welcome.

Black Gold is one of otetsu-P's iconic songs featuring Megurine Luka. It's also one of my fave J-pop songs to listen to, so I got curious on what the lyrics meant...

youtube

TL;DR I think the song talks about a breakup, in simplest words. But it is not one that ended because of infidelity.

So first off, I'm checking the PVs if they could have highlighted other elements of the song. The original PV by meola is more of a still, exhibiting the sheen of gold, contrasting on a dark background. Meanwhile, Project DIVA's game video features Luka in a railway station, with black-gold motifs.

youtube

Down to the lyrics, I looked up one at Vocaloid Lyrics by user @vaffisuco.

On Vaffisuco's, there are some notes, possibly adding more context to the intended message:

1. Not quite sure what the little 'dot' means between 犠牲 and 代償。Here I just assumed these two were connected to one another grammatically and in context. 2. Unsure if the その覚悟 part connects with the next sentence cluster, and can't tell if the intonation is necessarily going down to indicate the end of a sentence. I decided to translate these sentences as such as to avoid a very lengthy English explanation. 3. Here I assume that the singer is verifying her existence/her failed relationship. She grasps the 'love' and the Black gold ring in order to leave her 'mark'. May possibly be referring to the existence of her ex, but I decided to translate this portion in first person.

Those notes aside, comparing it to DeepL and Google Translate, the human and engine translations mostly have the same translation. For comparison on engine translations, I merged lines per phrase, usually into ones or two whole lines. There is also one line-by-line at DeepL, as the line breaks sort of bring a different context, though still similar.

Altogether, the translations at the first verses present a confusing group of lines.

I was asked to decide which way to go, and I lied. The person who told me to go right went left. (from DeepL, merged lines)

As someone who also speaks Tagalog, I might see that "going left" can translate to "pangangaliwa" or a connotation of adultery/cheating. However, I am not sure if this is applicable in Japanese too. So I thought that it implies more of a backsliding, or a reversal of what was once promised.

To be able to breathe / So that I can live / Having to put it into words (from DeepL, line-by-line)

To me this implies that there had been an end of a connection in good terms, that ironically not staying true (lying) to one's initial words would mean being true to the next.

It must have been hard for you to put it into words, but you were still smiling, covered in scars. (from DeepL, merged lines)

There is a slight difference on translated syntax to different engines, but it is pretty consistent with all three presented translations here. However, for the next line, both line-by-line DeepL and merged lines at Google Translate show the same to who is expressing laughter, but differ to who apparently got the injuries:

You're covered in scars/ I was smiling (from DeepL, line-by-line)

It would have been painful to put it into words. I was laughing with all the scratches. (from Google Translate, merged lines)

And so is for Vaffisuco's and merged lines at DeepL, saying it's the other party that did so:

As I became covered in wounds / You laughed. (Vaffisuco's Vocaloid Lyrics translation)

It must have been hard for you to put it into words, but you were still smiling, covered in scars. (from DeepL, merged lines)

I am not sure which among these translations fit the producer's intended message. Perhaps for one, it is open to interpretation. But I also think that the laugh can connote a "hiding the pain" (no reference intended), or it is more of a relief to one that broke the bond, that it had to be a relief for both.

The chorus translations are very similar. Vaffisuco's translation brings an imagery of, likely a lost possibility, a path that with this became a dead end.

Scared of the things that could separate us, / I averted my gaze and ran away / I stop in my tracks, my vision flickering / I am not prepared to be, or repay the victim* (Vaffisuco's Vocaloid Lyrics translation) *The words translated were "犠牲" (sacrifice) and "代償" (compensation). Per the note, the translator "assumed these two were connected to one another grammatically and in context."

Vaffisuco's translation strikes me that it was a shock for the person, as if they were caught off-guard. At least as how I see it, the persona talks about how difficult something was to let go, and consequently "repay" the compensation that for one, will mend things altogether. I reckon a line confirms it, that they still have a significant attachment despite the breaking away:

I'm so, so scared of being separated, / I just want to be by your side (Vaffisuco's Vocaloid Lyrics translation)

I'm afraid of being separated from you. I'm afraid. I wanted to be there. (from DeepL, merged lines)

Where Vaffisuco's (and another translation at LyricsTranslate) repeats with "or repay the victim", the engine translations seemed to show slight differences:

Stopping, hiding in plain sight The sacrifice, the price, I'm not prepared for [it] (from DeepL, line-by-line)

Stopping, sacrificing and compensating to appear and disappear (from Google Translate, merged lines)

The words may have resulted from completely different ways of extracting context from syntax, so here we are. But even so, the connotations share something in common. "To appear and disappear" presents itself in a way that there could be a sacrifice to begin with, to compensate in keeping, and the "stopping" in "[to] disappear". That's how I can interpret what I got from Google Translate. But for what DeepL showed, it could be reiterating the notion of not being able to accept for whatever had to be lost and "sacrificed".

The bridge builds up with lyrics that give a sense of "spiralling down". It likely, vaguely if anything, references fate being cruel.

So, what is the 'truth'? / Is it cold, hard metal? / Look, look at me walking! / Look, look at me walking! / So who was the one that made the decision? / Just where is our God? / Ah, how unfulfilling! (Vaffisuco's Vocaloid Lyrics translation)

What's the truth, what's cold metal? Look at me, I'm looking at you, I'm walking backwards, When did God decide? I don't know where God is, I can't fill it, I can't fill it. (from DeepL, merged lines) *Without the rest of the lines, "埋まらない 埋まらない" becomes "I can't bury it I can't bury it"

I'm not sure what the "cold metal" is about, but a quick Google search of "冷たい金属だとか" showed this (and another random translation):

Could it mean that that the brink of sincerity becomes no more than gold, but that of silver? Could it be referencing the conductivity of silver? Or maybe it just generally refers to metal left in a cool temperature, that literally feels hard and cold to touch?

And down to the last two choruses... the lines changed, going to the song's conclusion.

Separating from you, I go far, far away / To the people who went left / I'll leave your last act of kindness right here / So it won't lose it's brilliance (Vaffisuco's Vocaloid Lyrics translation)

To the one who went away, far away, to the left The last kindness you gave me, I'll leave it here so it doesn't fade away (from DeepL, merged lines)

Both DeepL and Google Translate shared very similar results. As for this, it bears acknowledgement on the other party, possibly memorializing the pleasant memories to be left behind.

What drives people apart / is that resolve for victims and their compensation I grasped the love dangling from my neck / and a black gold ring / So my footprints won't disappear (Vaffisuco's Vocaloid Lyrics translation) *Quoting the translator: "Here I assume that the singer is verifying her existence/her failed relationship. She grasps the 'love' and the Black gold ring in order to leave her 'mark'. May possibly be referring to the existence of her ex, but I decided to translate this portion in first person."

One of Vaffisuco's notes imply for the second last chorus that in times of trouble, people look for compensation and will do anything for it. It might try to say that at some point, vengeance is what pushes a person to act upon something; sometimes, this can be seen as closures, closing things. This is such that they believe that removing something from their live will make it easier, that it is a resolution on their part. (There definitely are more connotations that only human translators and native speakers can catch!)

To be separated from you The sacrifice, the price, the determination With [the] love around my neck and the black gold ring around my neck I'm trying to keep my footprints (from DeepL, line-by-line)

For the last chorus, I agree with Vaffisuco's note, seconding that the song is about a process of separation, when honesty is still honesty, and the difficulty of acceptance for one end (the persona). As for whose footprints are being kept, if it is decided that it was the persona's footprints, the persona wants to be remembered by one who left her. Otherwise, the persona wants to remember the other half, implied by the footprints.

As for the title "Black Gold", it can be interpreted in many ways. For English speakers, the phrase may be slang for "petroleum" as this resource in deposits had made certain countries rich by importation. But in jewelries, "black gold" refers to processed gold so its surface exhibits a black color.

Overall, the song shows itself as mysterious and poetic (especially that I am no Japanese speaker) with how the words are translated, and the implications I get by looking at how the syntax is processed for a language I am a native speaker of.

#black gold#megurine luka#vocaloid#巡音ルカ#otetsu#vocaloid lyrics#jpop#song lyrics#song lyrics meanings#japanese#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are you learning Japanese or would like to? I've been feeling inspired to myself after my friend surprised me with the Kiki's Delivery Service artbook (so thoughtful ❤), but am electing to use a translation app for now.

I'm actually really bad with languages, but I love learning about different cultures, so it sucks being me sometimes lol

I don't mind relying on machine translations or reliable people explaining things cause it's better to acknowledge a weakness than act like I know better than native speakers cause I happened to pick up a few words.

I've used several apps on the AC reunion files and compared them to the official translations and they're pretty decent. I also wouldn't post those machine translations without the original so other people can double check if they like. I think translators who only post their translation without the original are very suspect. It's like they're trying to hoard the info and prevent other people verifying what they've said.

Very sus...

I bet the art book is pretty! Studio Ghibli always makes everything so pretty, it's like watching a moving painting. So wholesome and cute ❤️

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m in a mood, so here’s some an extremely long post with shit conflict that happened on deviantart when i was younger that i’m still petty about and i wanna vent about it because if i wasn’t so young i woldn’t have let people step on me like that

No one should read this, tbh, it’s a fucking horror show out here

oc: Shinju

When i made her it was the first time one of my ocs had like effort put into it, i designed her, make her backstory, put her in kirigakure, and i spent a long time researching names for her, looking up japanese words that i think would fit her, Ren Takeo

One person commented saying that they had an with the same name, from the same village, though they didn’t mean any harm by saying that, and even said it was fine

Here’s where it gets tricky.

I then got comments and private messages from OTHER PEOPLE telling me to change the name

So, like the weak bitch i was, i changed her name

Oc: Roxy

I’ve talked about this one before, but i have this sonic oc named Roxy, i loved her, she was a bit edgy but like, queen, 10 years ago we were ALL edgy

I really wanted Roxy to be a lesbian, but i didn’t like, put that in the info, at the time gay ocs we’re really taken very well by the community, plus a few of my art friends were very iffy anytime i implied that some of my ocs might not be 100% straight.

now, i WANTED Roxy to be a lesbian but i was guilt tripped by some dude to roleplay with him, no matter now many time i said i didn’t roleplay, he wouldn’t take no for an answer and I was very easily guilt tripped into eventually saying yes

A roleplay starts with Roxy and his Male wolf characer, John, when we started he assured that they were gonna be friends but one thing lead to another and he pressured me into role playing a sex scene, i was 14, i didn’t want to, didn’t even know how to write that. At that age i hadn’t really even seen porn before, but a few days of mowing down my boundries and he guilt trips me into saying yes.

At that point, he essencially took Roxy and did whatever the hell he wanted with her. Next thing i know, Roxy was married to this male character and they had a baby? I even ended up making some art of them because he kept saying how he was tired of making all the artwork himself.

Thank god, eventually he forgot about me and Roxy for a lot time. The last time i talked to him was on a pm where he warned me he was gonna delete all his ocs, including Roxy and Johns child, i think he wanted me to convince him not to do it but by that time i was older and just said “alright man, see ya”

Thank fuck, that problem solved itself, but i’d be better off not going through it in the first place

The cosplay hellhole

When i first started cosplaying, i posted my pictures to DA too, since there was a cosplay community there, didn’t think anything would happen

When i got my first Harley wig and makeup i was so excited i posted them on deviantart, and they did quite well, tbh. Some people asked for fansigns, and i didn’t even know who those were but, once it was explained to me, i did some for people who requested them, from there it was also fine, but stay tuned, cause it’s gonna bite me in the ass later down the line

I start getting wierd dms, very sexual in nature, which grossed me out, since i was already 20 it wasn’t like, illegal or anything, but there was a pattern of people asking for sexual content followed by “it’s okay if you say no, though” and when i said no, they would be pissed at me, calling me a whore, saying if i didn’t want attention, i wouldn’t cosplay Harley.... keep in mind, all of my photos where from the shoulder up at this point, i muscle through this time, i’ve been harrassed enough to have a lil bit thicker skin.

But over time, the pile up of messages from diferent accounts were getting to me, and i was starting to delete photos.

AND THEN

He said he was embarrassed of having to send me these things but if i wanted the photo taken down i’d have to report it myself, thankfully he also found the direct link to the report page so i didn’t have to dig through the website. Thankfully the report worked and the photo was taken down

I receive a pm from a friend that scared the shit out of me. He was going through this porn website called Xhamster, he recognises someone using one of my fansigns as a photo, now he KNOWS this isn’t me, because i’ve been vocal about not wanting to be sexualized while in cosplay. Someone took one of the fansigns, edited out the words, flipped the image, and photoshopped their own signature on to the sign in hopes of like... getting verified or something?. In short this person was using my photo as if it was a photo of them.

That mixed in with the still incoming pms from creeps made me delete every cosplay photo i’ve ever posted on deviantart.

Years later i did post new cosplay stuff again, now giving a warning right at the top of the description and being very okay with using the block button to my leisure.

I’m taking a long as fuck hiatus from posting on deviantart, it’s been over a year now, but i still go on a block spree when someone breaks the rules i’ve set

The whole “Luís” saga

Sit down for this one, it’s the weirdest one

I had a friend named Luís, we weren’t super close, in fact he was mean to me a lot, making fun of my english, even though neither of us were native speakers, refering to my home country as “Spain’s bitch”. Sending me cartoon porn when i was underaged was a big red flag that i didn’t even think was a big deal until i was older and thought back on it, like that was fucked up.

One day, i had critiques open, Luís sends a super spammy message and then blocks me. I was like “okay, whatever, i’m tired anyway” and i blocked him back.

THAT is when shit hit the fan

He tries to unblock me and talk to me, when that doesn’t work he makes a secondary account and starts sending me very aggressive pms. I’m was tired of how he acted with me, plus something about him being so desperate to be unblocked didn’t sit right, so i just blocked the new accounts

He made 15 separate accounts, getting more and more angry with each one, i block all 15.

Suddenly i’m getting pms in english and spanish from people i’ve never interacted with, but aparently Luís had told them i was being some sort of monster, some of them backed off after seeing the full picture, the others got blocked

Luís girlfriend was friends with me.

He then threatned to leave her if she didn’t block me.... she left HIM, and now I’M being blamed for that

Someone shared some uuuuhhhh fanart he drew of her after that, it was super sus, it was a comic about him seducing her with a kiss in order to make her hate someone, girl you’re better off without him, jesus christ

Now shit starts moving off of deviantart

He finds my personal facebook, which was NOT disclosed to the public, and starts messaging me, from there he found my twitter, youtube, skype, starts messaging my irl friends, quite a lot of them did not even know english at the time.

In the few messages before i blocked him, i warned him to stop, i warned him he was stalking me online and that shit isn’t okay. THIS DUDE

this dude replied with “it’s not stalking because i’m younger than you”

BOI

this happened over the course of a year, and it was the first time i ever reported someone, hell it’s the first time i’ve seen a report be successful, because i contact deviantart with a list of everything he’s done, screenshots to prove it, links to his separate accounts where all the comments are ONLY about me

a week later they DELETE THIS MAN’S WHOLE ACCOUNT

I have not heard from him in almost a decade

This is like, the ONE TIME i feel like i won

Aaand well, done, those are the most serious one, there’s some minor shit that’s not worth talking about, but looking back, wow, i used to get a lot of sexual harassment on deviantart huh?

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello Cycles and Vv! I love your podcast and how in-depth you get, particularly with characterization across the seasons and character motivations. How many times do you each re-watch an episode before getting together to record the podcast? How much outside research (in literature, psychology, military tactics, etc, etc) do you do for each episode to make sure you get the references right and all that? Thank you!

Cycles: We typically rewatch the episode once, and have the outline and research done by Monday night for recording at the next available time. So if you want us to address a question in an episode, try to get it to us before then!

Vv: I tend to make notes after the first watch so I don’t get bogged down in too many details, then I go back to check for thematic threads or content I’ve missed. Meshing our notes is always a trip because we have completely different writing styles— so Cycles usually does hers first and then we add mine.

Cycles: As for research—it’s really whatever the content calls for! Sometimes we’ll follow the trail a reference leaves and sometimes we’ll decide something in the show could benefit from more explanation or real-world context. Then, we’ll use the internet (and Vv, specifically, will sometimes use an actual physical book) to learn more or confirm information we were already familiar with. On occasion, live human people with relevant areas of expertise are involved.

Vv: I am of the belief that it’s silly not to ask your friends for help, so if we’re discussing content we don’t have experience with, I’ll touch base with someone who does just to make sure we’re not saying anything inaccurate. (We also do this with language! Both Manchester’s British slang and the translation of Kara & Alex’s Japanese were verified by native speakers before we recorded.)When it comes to discussing production stuff, we check that as well. THERE’S ALSO A LOT OF SINGING. MOSTLY BY ME.

Cycles: Important production note: there were at least 5 pauses where Vv sang a reference while we were recording the last episode.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Words

During the years that I have practiced or taught aikido, the physical movements were often clarified, explained, or directed by words. Some of them were Japanese; most were English translations of Japanese expressions and constructs.

Blend with your opponent, extend ki, keep maai, practice fudoshin, keep one point, kokyu-nage, take ukemi, uke, nage, hatori waza.

As a student, I hear them as explanations and directions. As a teacher, I returned the favor. They became the lingua franca of the class. The language bridging the art’s movements with the mystical dimensions of budo. As a student, I assumed that the expressions and translations heard were correct. And the ones I used when I taught were uttered in the absolute belief I understood their meaning.

In 1991, Dave Lowry, an American martial artist, wrote an article entitled Aiki of Words. It was published in Aikido Today, the premier magazine for Aikido during that time. The point of the article was to caution aikidoka about the use of English to understand what Aikido is.

“Morihei Ueshiba never talked about harmony. The founder of Aikido never spoke either, despite what you’ve been told, about love or the relationship between Aikido and the mechanics of the universe.

By now the reader, if he has recovered from his outrage over these apparently heretical pronouncements, will have guessed that there is a little linguistic sleight of hand at work here. O’sensei did not mention these things because he did not speak English. If you think, however, that Ueshiba Sensei and other Japanese speakers were simply using a different language and that there are English translations that mean virtually the same, you are not just mistaken. You are ignoring one of the most significant and often-overlooked gaps that yawn between Aikido as it is practiced in its native environs and as it is followed in the West…

..unless they are very careful or undertake a serious study of the Japanese language (and its attendant culture) at the same time as learning Aikido, even dedicated enthusiasts may find themselves having slid into a sloppy reliance upon poor or incomplete translations – a reliance that may soon be reflected in a less than accurate understanding of Aikido itself.”

A number of words used in a dojo’s practice, such as maai and ki, have subtle and nuanced meanings. Witness the recent change of extending ki to ki is extending. While the change seems a slight juggling of word placement, the change in meaning is significant.

All of it reminds me of the old party game, where you whisper a message to one person, and they, in turn, pass it on to another. Around the room, or down the line, the message is whispered from ear to ear until it arrives at the last person in the room. It is a good bet that the resulting message is nowhere near what the original was. The words and their meaning passing from one person to another colored by what I mean when I say them and what you perceive when you hear them.

So what is the point of all of this? It is to be cautious. Understand that unless someone is well versed in the Japanese language and culture, you are depending on a teacher’s best efforts to educate themselves on the meaning of things. Have a healthy skepticism; trust and verify what you told and taught. Ask questions.

Also, in recent times, Kashiwaya Sensei, the Chief Instructor of our federation of dojos, has started to make more direct statements about what things mean and don’t mean.

自分は心身統一合氣道の指導者ですが、まだ修行中です。なので「合氣道とは」とか「天地とは」等と自分が分かったような事を言う事は慎んでいます。何故なら、お弟子さん達がそれが答えだと勘違いをしてしまうからです。これらの答えは��自が真剣に修行した上で感じ取れば良い事だと思っています。

I am a Ki-Aikido instructor, but I am still training. Therefore, I refrain from saying things that I understand, such as "What is Aikido" or "What is Tenchi”. The reason is that the students will misunderstand that is the answer. I think these answers should be felt after each student has practiced sincerely.

The short answer is to stay critical, open, and practice. Question authority, especially your own. That is the practice. Say hai, I understand, because that is not the same as saying yes.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

DAY 5 // 2018-06-28

Today, I was still working on my report on Sanskrit loanwords in Indonesian for a class where I am only audit. AND. I. FINALLY. FINISHED. IT!!!! You can consider that I didn’t do something else important so my day was not productive but I really think that I was too desperate to finish this freaking report today that I didn’t felt like adding a lot of tasks to my lists. Nonetheless, one of the tasks today was to publish my first post on the language I am working on in Taipei: Thao.

Let’s talk about this a bit longer because I am really excited!

Thao: Introducing a very serious endangered language of Taiwan

Thao is a language spoken by only 7 native speakers, in the Central Mountains of Taiwan, precisely in the Sun Moon Lake. Their village is now called “Ita Thao” which means “our Thao” / “our people”.

As I am meant to become an expert of Thao language, I thought that it would be nice to make some posts about it. I think positively about three benefits that this new commitment could bring me: 1. it will permit me to verify if I am able to explain to non-experts clearly the different notions treated by the posts; 2. it will be an overture to more knowledge for everybody; 3. it will be a source of motivation to go back to study on the domain when I don’t feel like it.

A crossroad between culture and languages?

The first post is about something I am very much interested in: Mythology in Thao. When I was taking my Latin, Old Greek and Biblical Hebrew classes in either high school, university or both, I was fascinated by these great creations of the human mind which had, and in a sense still has, a deep and profound impact on our societies nowadays. Mythology hence corresponded to steady categories of values, of heroes, of facts and interdiction which, with much drama, were totally getting out of control (Gods taking side and making wars, people... haha).

In Thao, the fascination comes from a little different perspective. First, in their mythology we don’t find as much details of epic wars or battles or even epic romance between the protagonists. Everything is very factual, there are even some reserve talking about love life. But as a group of hunters-gatherers for many centuries, they add very surprising details such as how to get back home when you go hunting in a forest, or also on how to cook fishes. Secondly, and maybe the most important in my point of view, the transmission of these myths. Thao is a language of oral tradition, the people were illiterate before the arrival of Japanese colonizers. During the Japanese era, they had to go to school and learn the Japanese writing system. Kilash, one of the most important informants of Thao in his time had try in his private notebooks to adapt the writing system of Japanese to his own language, having realized the crucial importance of writing his dying language down before it is too late. Hence, all the texts of mythology found in Thao society are all a transmission of ancestors. There is no means to verify if what was said 200 years ago was still going in the same direction or if Thao continuously reinvented their history through time.

The first post I made earlier is about the foundation of actual settlement of Thao people and the title of this myth is the white deer. I am also responsible for the graphics/edits you can see before the texts. I thought that everybody (including me of course) love to study with aesthetics or at least like beautiful things and feel more interested in learning the content.

If you are interested, I give you the link of my post here again.

I thank you for the warm support I received these past few days, you guys are awesome!! I was really touched!

xx

Eloo.

#studyblr#studyspo#lingblr#productivity#organization#intellectys#studyquill#itshannyb#athenastudying#educatier#studypetals#emmastudies#gay studies#studyblrpositivity#100 days challenge#blogging challenge#study motivation#100 days of productivity#small studyblr network#small studyblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Certificate Translation Services Near Me

There are many advantages of using Certificate Translation services. Certificate Translation Services can help you get a reliable document in a foreign language that is acceptable by a third party like an employer or a doctor. They also provide you with the opportunity to have your certificate translated by a professional who is not only skilled but has the credentials of being an authorized member of the International Certificate Translators Association (ICA).

Certificate translation services allow you to be sure that your certificate will always be accepted by your foreign counterparts. This can greatly improve the chances of obtaining jobs. In addition, cheap Certificate Translation services can give you a chance to present your certificate in an acceptable manner. Many employers prefer to see a certificate that is professionally translated from one language to another. By having your document translated in an acceptable language, you can increase your chances of getting a job.

Certification translation services can also help you with any legal issues that you may come across when using your certificate. Certificate translations can sometimes be difficult for people who speak no English. It can be difficult for a non-native speaker to read the certificate and understand its meaning. Having the translation done by a Certificate Translation Company makes it much easier for these people. Also, your certificate will be in the native language of the person who is receiving it.

Certificate Translation Companies can provide you with a professional translation that meets your expectations. The company can provide you with expert translation services that have been reviewed and approved by an accreditation body. These companies often also have a good reputation for using a high level of professional language in their translations.

Certificate translation companies usually have their own accredited translators and they will work closely with the company to make sure that your certificate is accurate and up to date. They will also conduct background checks to make sure that the translation is accurate. You will get an emailed confirmation that your certificate has been completed in a professional manner.

When you are looking for Certificate Translation services near me, you want to make sure that they offer fast service. An affordable Certificate Translation Company can provide your documents on schedule and at a reasonable price. Make sure that you find a company that offers a fast turnaround time to get your documents completed.

You want to make sure that you find a Certificate Translation Company that offers quality assurance. Quality assurance is very important. The company should be able to prove that their translations are accurate. You want to be able to verify the accuracy of your documents before they are shipped to you.

If you have a hard time understanding a certificate because you can't read it, you will want to choose a company that can help you learn how to read it. By using a certificate translator, you can easily learn how to read a certificate.

One thing to keep in mind when you are choosing a Certificate Translation Services near me is the company's reputation. A good certificate translation company will have a good reputation. There should be no problem finding out what kind of reputation the company has in the field.

Another important consideration in choosing Certificate Translation services near me is the language of the certificate. You want your documents to be in your native language. This will save you time when you need to use your certificate for legal purposes. You should find a translation service that can meet your needs.

You want to choose a service that has certificates in the various languages that are commonly used. such as Spanish, Chinese, Russian, French, Japanese and German. You also want a service that can provide you with a translation for each certificate. that is accurate.

A good Certificate Translation Service will also offer different certificate translations. you should look for a translation that will help you understand the purpose of your certificate. In addition to being able to understand the purpose of your document, you want to be able to understand the language. and the culture of the country you are sending your document to

0 notes

Link

A lesser known, yet uniquely compelling candidate for the real Satoshi Nakamoto is Japanese mathematician and number theorist Shinichi Mochizuki. With a long history of mathematical innovation, and purportedly proving conjectures thought to be near impossible to verify, he seems to almost come from an alien world. Mochizuki further painstakingly avoids the spotlight. Some, like American computer scientist and co-inventor of hypertext, Ted Nelson, go so far as to call him Satoshi.

Also Read: “I Designed Bitcoi… Gold” – The Many Facts Pointing to Nick Being Satoshi

The Coolness Outside

As Paul Rosenberg states in his blog post “Be the Outsider,” everything that ultimately innovates comes from a private space, on the fringes of society: “Please believe me that the coolest things happen outside, and not within the hierarchies of the status quo … Outside is where personal computers came from. It’s where the Internet came from. It’s where Bitcoin came from … Nearly everything cool comes from outside.”

Japanese mathematician Shinichi Mochizuki fits this unorthodox form as well. Attempting to solve “impossible” problems, focused only on his work and hiding from the spotlight, the 50-year-old professor Mochizuki has chosen not to submit his most revolutionary ideas for formal review. He has instead — much like Satoshi Nakamoto — surreptitiously placed them on the internet, and walked away.

Shinichi Stats

A Mathematics Prodigy

Child of an international marriage, Mochizuki moved with his family from Japan to the United States at age five, and would go on to graduate Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire at age 16. From there it was Princeton University for a bachelor’s degree and Ph.D in mathematics, lecturing at Harvard for two years, and then a return to Japan in 1994. Mochizuki is currently a full professor at Japan’s prestigious Kyoto University.

In spite of impressive accomplishments and accolades such as proving Grothendieck’s conjecture on anabelian geometry in 1996, and being invited to speak at the International Congress of Mathematicians, nothing would cause such a stir as his alleged proof of the ABC Conjecture in 2012. The conjecture is described as a “beguilingly simple number theory problem that had stumped mathematicians for decades.”

What math experts found in reviewing the proof, however, was that they couldn’t even understand it, and Mochizuki couldn’t be bothered to explain. Caroline Chen notes in her article The Paradox of the Proof:

Usually, they said, mathematicians discuss their findings with their colleagues. Normally, they publish pre-prints to widely respected online forums. Then they submit their papers to the Annals of Mathematics, where papers are refereed by eminent mathematicians before publication. Mochizuki was bucking the trend. He was, according to his peers, “unorthodox.” But what roused their ire most was Mochizuki’s refusal to lecture.

Much like Bitcoin had been carefully dropped off as an alien creation on obscure corners of the internet at its inception, Mochizuki had dropped off a supposed bombshell in the field of mathematics and stepped back. He had even created his own terminology over a decade of isolated research which other mathematicians couldn’t parse.

Chen explains: “Then Mochizuki walked away. He did not send his work to the Annals of Mathematics. Nor did he leave a message on any of the online forums frequented by mathematicians around the world. He just posted the papers, and waited.”

An American Background in British English

Critics of Satoshi theories placing a Japanese as Nakamoto often cite Satoshi’s impeccable command of the English language and grammar in correspondence, and the cleanliness of his writing style. As a native speaker, this would have been a non-issue for Princeton salutatorian Mochizuki.

Also frequently cited is Satoshi’s use of typically British English expressions and spellings such as “bloody” and “colour.” Interestingly, Mochizuki’s mentor and doctoral advisor from Princeton, Gerd Faltings, is a German national. The two would have presumably communicated in English at Princeton in an academic setting, and the English formally taught in Germany is typically British English. Mochizuki would have also undoubtedly been exposed to the British usages at his prestigious boarding school, Philips Exeter Academy.

Hyper-Endorsement from Ted Nelson

The inventor of hypertext, computer scientist and philosopher Ted Nelson feverishly rushed to produce an entertaining and insightful video on Mochizuki in 2013 after reading an article about him and deciding that Shinichi Mochizuki was indeed “the one.”

Lack of Explanation and Evasion of the Spotlight

Sorry to be a wet blanket. Writing a description for this thing for general audiences is bloody hard. There’s nothing to relate it to.

So read the words of Satoshi Nakamoto from a July 5, 2010 post to Bitcointalk.org, in attempting to define Bitcoin for a wider audience. Like Bitcoin, Mochizuki’s purported proof of the ABC Conjecture was a novel contribution not readily grasped by the public, or even experts. With a stated goal of establishing “an arithmetic version of Teichmüller theory for number fields equipped with an elliptic curve … by applying the theory of semi-graphs of anabelioids, Frobenioids, the etale theta function, and log-shells,” even the world’s premier mathematicians were stumped, and Mochizuki couldn’t be bothered to explain.

When asked by a well-known university to visit and expound on the proof, Mochizuki reportedly stated “I couldn’t possibly do that in one talk.” He then refused even when offered more time. Friend and colleague of Mochizuki, Oxford professor Minhyong Kim, states that Shinichi is a “slightly shy character,” noting:

He’s a very hard working guy and he just doesn’t want to spend time on airplanes and hotels and so on.

Japanese Background

Japanese culture is quiet, reserved, and hardworking, generally speaking. Humility and politeness go hand-in-hand with and an almost painful aversion to being the center of attention. In Japan it is viewed as graceful and appropriate to do one’s work quietly, complete the task, and not make much of a fuss about it. This can be very different from the general Western individualist ethos, which often calls for flashy attention or a prize in the face of groundbreaking accomplishment.

On a linguistic aside, the name Shinichi means “new one” in Japanese, and interestingly shares a syllable count with Satoshi. The surnames line up syllabically as well, but this could be nothing more than mere coincidence.

Skepticism and Summary

The most obvious argument against Shinichi Mochizuki being Satoshi Nakamoto is a glaring lack of known background in computers, coding, and cypherpunk ethos and knowledge. It’s hard to imagine though, that a scholar of his caliber in the field of mathematics would not have at least some working familiarity with these fields. Critics have pulled no punches in attempting to put the Mochizuki as Satoshi theory into the cultural paper shredder, even leveraging insult to do so. Still, like the other candidates in this series so far, Mochizuki merits examination on a variety of counts, and further adds to the mystery of the hunt for Bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator.

Who do you think is Satoshi? One person? Many? Let us know in the comments section below.

0 notes

Text

The Many Facts Pointing to Shinichi Being Satoshi

New Post has been published on https://coinmakers.tech/news/the-many-facts-pointing-to-shinichi-being-satoshi

The Many Facts Pointing to Shinichi Being Satoshi

The Many Facts Pointing to Shinichi Being Satoshi

A lesser known, yet uniquely compelling candidate for the real Satoshi Nakamoto is Japanese mathematician and number theorist Shinichi Mochizuki. With a long history of mathematical innovation, and purportedly proving conjectures thought to be near impossible to verify, he seems to almost come from an alien world. Mochizuki further painstakingly avoids the spotlight. Some, like American computer scientist and co-inventor of hypertext, Ted Nelson, go so far as to call him Satoshi.

The Coolness Outside

As Paul Rosenberg states in his blog post “Be the Outsider,” everything that ultimately innovates comes from a private space, on the fringes of society: “Please believe me that the coolest things happen outside, and not within the hierarchies of the status quo … Outside is where personal computers came from. It’s where the Internet came from. It’s where Bitcoin came from … Nearly everything cool comes from outside.”

Japanese mathematician Shinichi Mochizuki fits this unorthodox form as well. Attempting to solve “impossible” problems, focused only on his work and hiding from the spotlight, the 50-year-old professor Mochizuki has chosen not to submit his most revolutionary ideas for formal review. He has instead — much like Satoshi Nakamoto — surreptitiously placed them on the internet, and walked away.

Shinichi Mochizuki

Shinichi Stats

A Mathematics Prodigy

Child of an international marriage, Mochizuki moved with his family from Japan to the United States at age five, and would go on to graduate Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire at age 16. From there it was Princeton University for a bachelor’s degree and Ph.D in mathematics, lecturing at Harvard for two years, and then a return to Japan in 1994. Mochizuki is currently a full professor at Japan’s prestigious Kyoto University.

In spite of impressive accomplishments and accolades such as proving Grothendieck’s conjecture on anabelian geometry in 1996, and being invited to speak at the International Congress of Mathematicians, nothing would cause such a stir as his alleged proof of the ABC Conjecture in 2012. The conjecture is described as a “beguilingly simple number theory problem that had stumped mathematicians for decades.”

What math experts found in reviewing the proof, however, was that they couldn’t even understand it, and Mochizuki couldn’t be bothered to explain. Caroline Chen notes in her article The Paradox of the Proof:

Usually, they said, mathematicians discuss their findings with their colleagues. Normally, they publish pre-prints to widely respected online forums. Then they submit their papers to the Annals of Mathematics, where papers are refereed by eminent mathematicians before publication. Mochizuki was bucking the trend. He was, according to his peers, “unorthodox.” But what roused their ire most was Mochizuki’s refusal to lecture.

Much like Bitcoin had been carefully dropped off as an alien creation on obscure corners of the internet at its inception, Mochizuki had dropped off a supposed bombshell in the field of mathematics and stepped back. He had even created his own terminology over a decade of isolated research which other mathematicians couldn’t parse.

Chen explains: “Then Mochizuki walked away. He did not send his work to the Annals of Mathematics. Nor did he leave a message on any of the online forums frequented by mathematicians around the world. He just posted the papers, and waited.”

An American Background in British English

Critics of Satoshi theories placing a Japanese as Nakamoto often cite Satoshi’s impeccable command of the English language and grammar in correspondence, and the cleanliness of his writing style. As a native speaker, this would have been a non-issue for Princeton salutatorian Mochizuki.

Also frequently cited is Satoshi’s use of typically British English expressions and spellings such as “bloody” and “colour.” Interestingly, Mochizuki’s mentor and doctoral advisor from Princeton, Gerd Faltings, is a German national. The two would have presumably communicated in English at Princeton in an academic setting, and the English formally taught in Germany is typically British English. Mochizuki would have also undoubtedly been exposed to the British usages at his prestigious boarding school, Philips Exeter Academy.

Hyper-Endorsement from Ted Nelson

The inventor of hypertext, computer scientist and philosopher Ted Nelson feverishly rushed to produce an entertaining and insightful video on Mochizuki in 2013 after reading an article about him and deciding that Shinichi Mochizuki was indeed “the one.”

youtube

Lack of Explanation and Evasion of the Spotlight

Sorry to be a wet blanket. Writing a description for this thing for general audiences is bloody hard. There’s nothing to relate it to.

So read the words of Satoshi Nakamoto from a July 5, 2010 post to Bitcointalk.org, in attempting to define Bitcoin for a wider audience. Like Bitcoin, Mochizuki’s purported proof of the ABC Conjecture was a novel contribution not readily grasped by the public, or even experts. With a stated goal of establishing “an arithmetic version of Teichmüller theory for number fields equipped with an elliptic curve … by applying the theory of semi-graphs of anabelioids, Frobenioids, the etale theta function, and log-shells,” even the world’s premier mathematicians were stumped, and Mochizuki couldn’t be bothered to explain.

When asked by a well-known university to visit and expound on the proof, Mochizuki reportedly stated “I couldn’t possibly do that in one talk.” He then refused even when offered more time. Friend and colleague of Mochizuki, Oxford professor Minhyong Kim, states that Shinichi is a “slightly shy character,” noting:

He’s a very hard working guy and he just doesn’t want to spend time on airplanes and hotels and so on.

Japanese Background

Japanese culture is quiet, reserved, and hardworking, generally speaking. Humility and politeness go hand-in-hand with and an almost painful aversion to being the center of attention. In Japan it is viewed as graceful and appropriate to do one’s work quietly, complete the task, and not make much of a fuss about it. This can be very different from the general Western individualist ethos, which often calls for flashy attention or a prize in the face of groundbreaking accomplishment.

On a linguistic aside, the name Shinichi means “new one” in Japanese, and interestingly shares a syllable count with Satoshi. The surnames line up syllabically as well, but this could be nothing more than mere coincidence.

Skepticism and Summary

The most obvious argument against Shinichi Mochizuki being Satoshi Nakamoto is a glaring lack of known background in computers, coding, and cypherpunk ethos and knowledge. It’s hard to imagine though, that a scholar of his caliber in the field of mathematics would not have at least some working familiarity with these fields. Critics have pulled no punches in attempting to put the Mochizuki as Satoshi theory into the cultural paper shredder, even leveraging insult to do so. Still, like the other candidates in this series so far, Mochizuki merits examination on a variety of counts, and further adds to the mystery of the hunt for Bitcoin’s pseudonymous creator.

Source: news.bitcoin

0 notes

Text

youtube

Learn Japanese Fast and Enjoy the Process

Do you learn japanese 3ds need assist choosing a Japanese learning program? I discovered Japanese from spending some time over in Japan. Then, I appreciated it a lot I went on to study it in college. It was a great experience for me. After graduating with a serious in Japanese, however, it has been troublesome to review it download free japanese learning program alone.

I used to be used to simply speaking the language in Japan or in faculty courses. The place I reside there are practically no Japanese people I can converse with regularly. This has created a need for me to look online for applications that can assist me to maintain up my Japanese. Whether or not you are a newbie or would like identical to to brush up, there are great packages on the market.

I might prefer to suggest some issues to look for when selecting an internet program to study. I would say a very powerful factor is to make sure the particular person instructing you is a native speaker of the language. I can tell by the person's identify and the sound of their accent. You might have to look a bit of nearer to see in the event that they mention it as a promoting level. They won't say something if the particular person isn't native Japanese.

Often there will likely be a free trial period to see in the event you like the program. Why not go ahead and see if the program is for you? You'll need to present your electronic mail deal with however that's all that's required. Select to take the trial when you'll be able to spend some time exploring the product after which you'll know if it's a good fit.

It is crucial when learning anything to have the ability to ask questions. Verify to see if the program entails native speakers and academics how to learn japanese quickly of Japanese answering questions that you will have through electronic mail or by cellphone. That is actually an essential feature.

Make sure the program is interesting. Are there video games or self exams or playback features to see how properly you might be doing while having fun? Are the conversations tremendous boring or is there some humor in them? If you will spend hours doing this you will must get pleasure from it.

Lastly, and one among my favorites is about culture. It's a big one for me. I actually would not love Japanese if it weren't for the culture surrounding it. I love that the Japanese individuals discuss so much of nature or of one's health. blog link The significance of the nod you give with salutations, the slurping of your soup, the respect of the Buddhist altars in people's homes. These are all very interesting, fun and even essential if you are going to travel over there.

Not everyone who's looking for Japanese learning software is inquisitive about studying the language like a local. For many who are just going to Japan for a vacation, slightly basic vocabulary is enough. Armed with a phrasebook, some simple phrases and some polite conversational Japanese, the traveler will get far more out of their trip to Japan than they are going to if they simply rely on English talking Japanese to help them discover their manner around.

There are several cheap Japanese studying software program packages which might be designed for vacationers and enterprise individuals who only need to get a fundamental grasp of the language. Priced at below $50 each, most of those are properly definitely worth the funding. A phrasebook alone learn japanese the fast and fun way will never really be sufficient. Japanese is a language that must be listened to and spoken. Pronunciation, inflection and pitch are all extraordinarily necessary facets of the Japanese language. A multi-media strategy to studying is also a much sooner method to get a feel for the language.

One of the most well-liked low-cost language studying series for any language is the Discuss Now! collection of language instructing CD's. At just under $35, the Discuss Now! Japanese program consists of most of the options that far costlier packages supply how to learn japanese quickly and easily Whereas it's not meant to present an intensive data of Japanese, customers of this program nearly universally report that they come away feeling comfortable with the Japanese that they have discovered. The most popular characteristic of this program is the video games. Customers

Almost any language scholar will tell you that flashcards are among the best vocabulary constructing instruments there are. The Declan Japanese studying program is a contemporary audio-visual adaptation of this time-tested learning assist. The Declan program lists for $32. Which will seem expensive for a fairly easy program, nevertheless it also contains entry to a downloadable database of 3200 of the most ceaselessly used Japanese words.

Declan additionally provides two programs for college students who wish to be taught to learn and write Japanese. Their ReadWrite Hiragana and Katakana downloads learn japanese fast record for $14 every and the Kanji's checklist worth is $sixteen. These programs, like all of the Declan language applications, include free lifetime upgrades.

For vacationers on the go who don't want to lug around their laptops to study Japanese, the Berlitz Chinese/Japanese studying program is properly worth contemplating. Berlitz is one of the oldest names in language teaching and appears to have kept up-to-date with this program. While this amalgam of two languages in one teaching program has been criticized for being "watered down," it has also been praised as being probably the most cellular packages available, because of its special function that allows the consumer to install it on Palm or Pocket PC's.

The Berlitz Chinese/Japanese language program has a list value of $39.ninety five.

At $24.95, Human Japanese Version 2 is likely one of the cheapest Japanese learning software programs and is superb worth for the worth.

This obtain solely program accommodates over 1800 voice recordings of important Japanese phrases and phrases, video games, quizzes and an easy to make use of dictionary. The major criticism about this Human Japanese is that it is not an interactive program and some say that it has a "textbook" really feel to it, because it comprises no video or voice recognition options. Others have mentioned that they discover it quite pleasant and entertaining despite its lack of video.

These are simply some of the extra in style Japanese studying software program merchandise that can be bought online. There are lots of others to select from that may be "sleepers" waiting to be discovered. Different college students have different needs and studying preferences. Contemplating the range of language studying software program functions that's out there, it's a honest guess that there is something that is good for anybody!

Bunky Malone is a Tokyo-based editor and author. He exercises vigorous health and rampant self-improvement. learn japanese words He publishes on Japanese language software program and on yoga - two of his pursuits.

A relative newcomer to the rising Japanese language software area, Rocket Japanese has a distinct benefit over lots of its on-line opponents. It has been designed and marketed from the bottom up for the web era. Whether that makes read more on wikipedia here it a greater language learning system than others is open to debate, however the Rocket language learning sequence is quickly gaining gross sales ground on its competition thanks largely to the corporate's marketing technique.

There are two levels to the Rocket Japanese studying program - Rocket Premium and Rocket Premium Plus. Whereas the worth tag on each of them puts them on the high finish of the market scale, Rocket additionally gives a downloadable choice that isn't obtainable from other high-end language courses, making it far more affordable for many who don't feel they want the CD's. While the total package, including both "Rocket Premium" and "Rocket Premium Plus" (the superior module) together cost nearly $600 when purchased as CD's, the absolutely featured downloadable model is available in at slightly below $250.

Value alone should not be the one criteria for purchasing a language program. The ultimate aim, in spite of everything, is to learn the language. best japanese learning books for beginners pdf The question becomes, can Rocket Japanese assist you to to learn and use the Japanese language as effectively as different merchandise can?

Like its main competitors, together with Pimsleur and Rosetta Stone, Rocket Japanese emphasizes learning conversational Japanese by listening and talking in a conversational method relatively than by memorization alone. Not like the others, although, the Rocket audio course breaks its http://www.languageopolis.com/ 31 classes down into subcategories such as purchasing and touring. Some college students could find this a handy solution to focus on their core area of curiosity, while others feel a fractured method like this limits the scholar's capability to master the language as a whole.

The Rocket program makes use of a multi-faceted educating construction that features grammar, vocabulary constructing games and a Hiragana writing and reading program. While on the floor it may seem to be a shotgun method visit to educating that provides college students too much, too soon, this system is designed to permit college students to proceed at their very own tempo and to customise their own learning experience and environment.

This freedom is without doubt one of the main criticisms of the Rocket Japanese learning system. Each Rosetta Stone and Pimsleur are extremely structured applications which are designed to be used step-by-step for best effectiveness. Advocates of the Rocket approach, nonetheless, say that its interactive recreation software program makes the entire learning experience enjoyable and that the language skills assessments give the scholars enough of a motivation to grasp their language expertise and to monitor their progress. They really feel that the extra inflexible step-by-step method of other teaching systems is overly pedantic and unrealistic for an unsupervised studying surroundings.

The makers of the Rocket language series have performed their internet advertising and marketing homework. Not solely do they provide a considerable low cost for the downloadable version of their program, additionally they provide a free downloadable six lesson trial. For anyone who's sitting on the fence attempting to decide which program to try, this free trial is likely to make them lean in Rocket's path. These brief introductory classes are very easy to master and though you come away needing extra, you do come away having learned just a little of the language.

The major criticism that is leveled towards the Rocket language learning system as an entire is that it's a system that is designed to promote more than it is a system that works. Criticisms aside, although, Rocket makes it straightforward for their potential clients do determine for themselves whether it is worth purchasing. Perhaps Rocket's rivals would do properly to take a leaf from Rocket's book and update their products to suit the web market in addition to Rocket has done.

If you're considering learning Japanese for any purpose, you will undoubtedly be looking for a Japanese Learning Software program Program. There are plenty of them to choose from. The question is, 'Which one is one of the best?' There is no such thing as a single reply to this query, however with a little bit data, you usually tend to discover the Japanese studying software that is best for you.

The first thing to consider is how effectively a language studying program does its job. Instructing languages has advanced because the days when memorization and rote studying was the one teaching strategy employed. The higher language programs right this moment are way more subtle and use a variety of teaching techniques to expedite the learning course of. The best Japanese instructing packages are genuinely interactive packages designed to interact the coed in pleasing workouts which are both motivational and effective.

The best Japanese language software programs employ a radically different premise from the older, more pedagogic technique that teaches language as a second language. Outdated-style teaching makes use of the student's native language as a base: new phrases are learned by translation and Here is Social Network memorization. Sentence construction, verbs and tenses, and many others. are all in contrast and contrasted to 1's native language. The most well-liked and efficient packages at the moment educate language in the way in which that youngsters learn their native language - from scratch.

When youngsters are learning to talk, they are starting from a blank slate. They hear a jumble of sounds coming from others and eventually start to mimic those sounds. As they progress, they associate sure sounds with sure objects - "Papa" and "Mama" are often the primary words LanguageOpolis a baby learns as a result of they're easy words that are connected with powerfully emotive "objects" of their atmosphere. They build on this checklist steadily till they'll speak their native language fluently. The "nuts and bolts" of formal training come much later.

The older style of learning may be effective if you're a native English speaker studying a European language as a result of all of our European languages have their roots primarily in Latin. Many words have comparable roots and word affiliation is often straightforward. The logic of the construction of sentences, tenses, and many others. can also be comparable.

Asian languages have solely totally different roots and the student of Japanese is confronted with a completely international language. It's troublesome sufficient to study to grasp or communicate these languages. With regards to studying and writing, it may be an awesome job. We are actually starting out as youngsters once we're studying Japanese, so it is smart to learn the language as children study - starting with a blank slate. Which will sound difficult, however those who have tried Japanese studying software program that teaches on this method have found that they study faster and retain greater than they might through the use of traditional studying methods.

Another thing to contemplate while you're in search of Japanese studying software is worth. If you're planning on going to Japan for a short trip, a cheap Japanese CD Rom that teaches you some fundamental spoken language expertise could also be all that you just need. If you are occurring enterprise, it's possible you'll require a more complete program.

Prices for Japanese learning software program programs fluctuate tremendously, from as little as $15 to as a lot as $500 or more, so the worth of this system is a crucial consideration. There is no sense spending $500 if all it's essential know is how you can say hey in Japanese and to ask a couple of simple questions. A number of the most cost-effective Japanese language CD's can educate you this stuff and extra fairly successfully.

In our subsequent installments, we'll look somewhat more carefully at a number of the more in style Japanese learning software applications. Every of them has its robust and weak points. A few of the costlier applications are absolutely complete, but require a tremendous dedication of money and time in an effort to absolutely grasp the language. Some are higher for studying spoken Japanese than for studying and writing the language.

If you're intending to invest money and time into studying Japanese, you will want a program that makes you need to be taught, that engages your attention and that helps you each step of the way. There is no such thing as a use pretending that learning Language Opolis learn japanese fast Japanese might be completed in a single day. It will not be straightforward, but it needn't be a burden, either. With the best Japanese studying software program, it may be an exhilarating expertise that you just sit up for on daily basis!

0 notes

Text

yamatosan is typing, or how i lost several hours of the day due to a misunderstanding

so this will be kind of a thing i do to keep track of the little things i get curious about as i’m surfin teh webz (lolcats?). most of these are highly-irrelevant to anything of substance at my current level and understanding of japanese, but they’re a common fixture in my life. at least enough to seek out and understand if for no other reason than to satiate boredom. more under the cut. may contain plain words, kanji, and bits of grammar all in one.

(warning: anyone who has a functioning knowledge with japanese will find this extremely sad and pathetic lol! novice blundering ahead)

入力中

this is the first of the day. it actually threw me off at first because of the sentence in which i encountered it, which is within a messaging program. the sentence was as follows: 「大和さんが 入力中…」 ( 大和さん being just a euphemism in this case)

being still a relative novice, i thought i stumbled upon some grammatical error or kind of nonsense because of a translation error or typo. the truth is that it’s much more complicated and deals with a concept new to me. i looked up the term as presented in bold because the beginning of the sentence is fine to me but 入力中 looks like a noun without the telltale kana of most verb conjugations. but it’s very much a verb. since it’s been conjugated, it doesn’t show up in the dictionary except in a noun which has different kanji tacked on. this is how i came to the conclusion that there was an error in the instant messaging client.

but a bit more searching led me to this question on hinative (the link from google pointed to the question linked previously, which is in traditional chinese, but the english version of the site can be viewed here. i kept the original link to document the experience) which has a short, concise explanation from a native speaker:

中 is used after a noun which can be a verb with する (e.g. 入力する). It means an action is being performed. e.g. いま文を入力中です。=いま文を入力しています。

(courtesy of user mfuji)

so according to mfuji, in this case, 中 indicates an action is being performed presently (making sense in context of the messaging program, which displays the original message from before whilst someone is typing), seemingly to “mobilize” a noun that can become a verb through the use of ~する, which i’ll explore in the next section to make a better understanding of this. but odd to me is that there’s a ~です at the end. i’m not doubting the legitimacy of the statement, mfuji is the native here. it’s just something i don’t understand. ~です is along the lines of indicating something is a certain way (to my unsourced knowledge; need to research this) and is really common in basic “A is B” sentence structures (but i read once that there is a distinction between states of being that are not expressed in english; source is not easily verified quickly but is out there and prompts me to look into it another time (also note that i can’t find the exact passage this information was in, my apologies!)). my only available explanation at the moment (which is subject to change, naturally) is that because the verb in the second sentence has a ~ます form, it’s to add an extra politeness to it. alone, it might not be normal to say to someone with whom you are on ~ます terms with. but this is entirely my own conjecture as a novice and is not fact at my present understanding.

so naturally the next step would be to dissect the usage of ~中. i headed over to the japanese stackexchange as i generally trust the people there to be more informed than random blog posters (such as yours truly). to my surprise, i couldn’t find what i was looking for, but it might have been a fault of my search syntax. so i decided to approach it in a different way, by using two popular online dictionaries.