#vaultsofmann

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

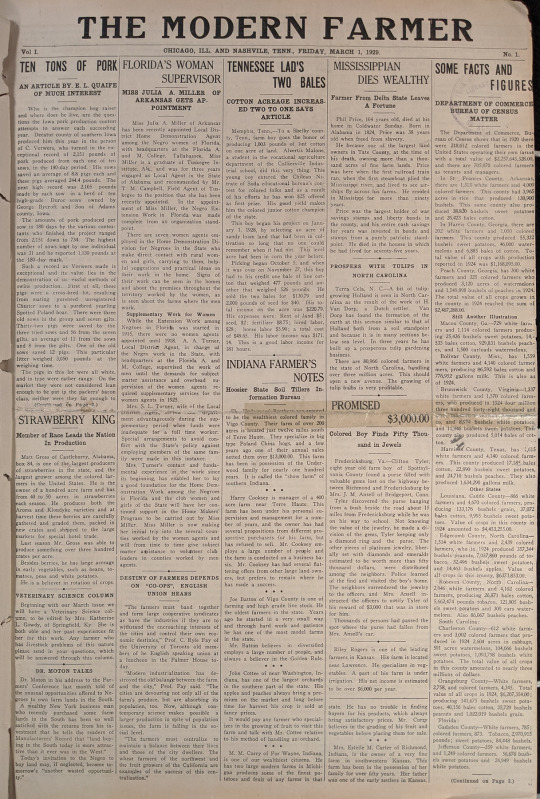

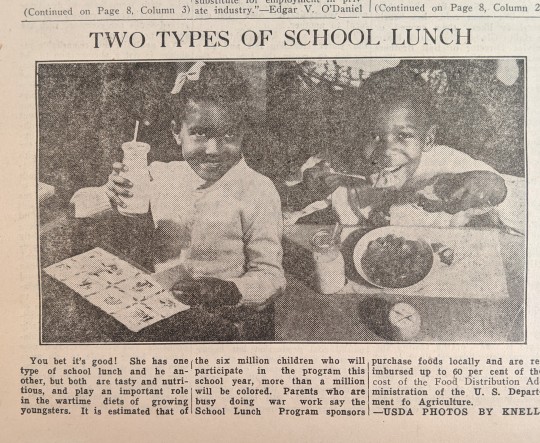

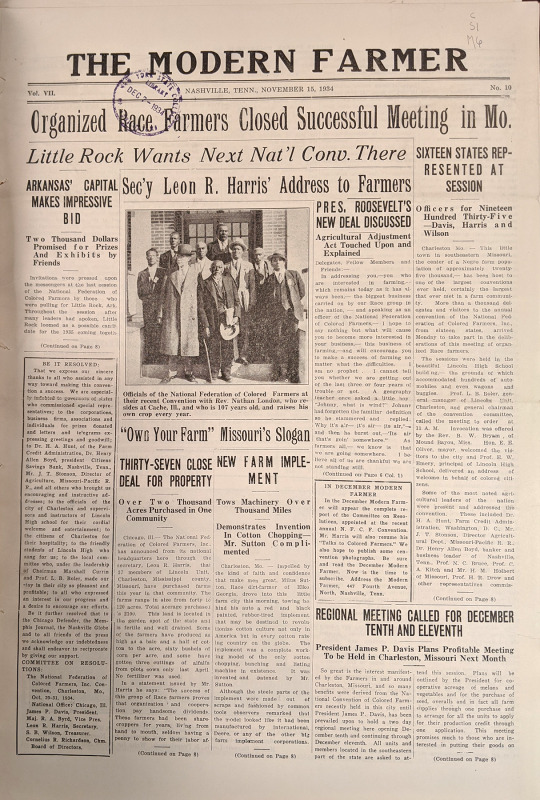

Modern Farmer

As many of us know, the farming life can be an epically tough vocation. And as some of will also be keenly aware, this has been more true for some than for others. Thanks to a recent scanning project, we’ve had our eye on the story of The Modern Farmer, a publication produced by the National Federation of Colored Farmers (NFCF) during a stretch of economic history that was hard for most folks in the United States—1929 through 1949—but especially so for African Americans confronting the vise of Jim Crow in the American South. As Black History Month closes out for this year, we’re pleased to share a little of what we’ve learned about this remarkable publication and the people who produced it.

Issued monthly, The Modern Farmer was first and foremost a periodical release of current news of interest to African American farming households. Its purpose: To share information that would advance the efforts of the NFCF in building the capacity of America’s black farmers to prosper. Founded in 1922 by a group of African American entrepreneurs and attorneys led by broker James P. Davis and heavily influenced by the teachings and philosophy of Booker T. Washington at the Tuskegee Institute, the NFCF had an initial early focus on building cooperatives and procurement/distribution networks. With this approach, the Federation hoped to secure reliable markets, good prices and fair interest rates for participants, attract a growing membership to these networks, and ultimately make it possible for rural black communities to take care of themselves. Over the years, as it became clear that (yet again) black farmers were being excluded from the benefits of New Deal legislation and programs, the Federation also turned attention and energy towards strengthening African American farmers' political clout.

Flip through the monthly issues of The Modern Farmer across its 20 years of publication, and you can't help but be impressed with the community purpose that emanates from its lively pages. Reports of farmstead success and tragedy, pithy advice on personal care, nutrition and diet, and school news published in its pages evoke a vibrant sense of shared experience and mutual care. Announcements about scholarship programs and religious conventions publicize opportunities for personal growth. News about lynching events and racially discriminatory hiring practices at specific firms and factories inform its readership on the specific dangers and challenges (and sometimes also more hopeful breakthroughs) happening at local, state as well as national levels. Of course, the periodical’s dominant content most certainly pertains to farming, as it provided a steady feed of news relevant to farm techniques and operations (e.g. "Ladybugs Used to Save Apples from Insect Parasite"), trends in markets and product marketability (e.g. "Federal Buying of Wheat Said to Be Justified" and "Potash Improves the Baking Quality of Michigan Potatoes"), and financing ("Biggest Fund in United States History Authorized by Senate: Two Billion Dollar Credit Assures Real Relief." ). And certainly not least: Across all of its pages, a strong editorial case for the power of organizing and collective strategizing will not be lost on any reader.

Given its timing, the NFCF was not poised particularly well for success. The 1930s were, after all, years that Jim Crow was maturing to its full, noisome ripeness in the American South, adding a huge handicap to widespread African American advancement in any pretty much any industry. While the color line may have been less brutally enforced elsewhere in the United States, it remained, of course, a perniciously widespread reality in American socioeconomic life in all corners of the country. And then of course, there were financial and natural disasters that shaped the Great Depression of the 1930s. Precipitous drops in commodity prices, crushing debt, floods, dust storms, heat waves, pest plagues spelled disaster for farming communities across the United States, black or white. Finally, of critical importance: the NFCF suffered from a serious internal weakness as well. Organized and largely led by prosperous black businessmen and professionals, the Federation was faulted for not sufficiently speaking to the realities of the land-poor tenant farmers and sharecroppers who made up the bulk of the black farming community of the rural South and who ultimately saw their interests and concerns better served by sharecropper unions and more politically engaged civil rights organizations of the 1930s.

Yet the NFCF was nothing if not energetically determined in its hope of making successful collective self-help and, eventually, a greater political voice, a reality for black farmers. For a time at least, there was good reason to gain confidence about this prospect. In September 1930 "The National Federation of Colored Farmers .... reports that 500 farmers in Holmes County, Mississippi have made the first purchase of a carload of groceries and supplies through the federation. The farmers, by wholesale buying, saved 42 percent on the cost." Later that year, promising negotiations between African American merchant associations in New York City and black farmers with melon and other fruits to sell had begun. By 1939, The Modern Farmer was able to spotlight an impressive victory on its front page: The Special Assistant to the Administrator of the U.S. Agricultural Adjustment Act had been successfully enjoined to meet with the NFCF to address concerns about the Act’s deleterious effects on black farmers.

Mann Library has the good fortune of being able to offer the full run of The Modern Farmer as part of its special collections in historical agriculture. As far as we know, we may be the only library with this rare and important piece of African American history in its collection. But we’re also happy to say that you don't need to actually walk through the front doors of our building to get a look at this treasure. Thanks to a recent scanning initiative, The Modern Farmer is now available for anyone with access to a computer and the internet. We invite you to take a look at archive.org. It is worth a good, long browse, for across the lively issues of its two decade run, you will get an amazing view of unflinching determination. The history of African American farmers in the United States may be one of contending with bitterly long odds—but what materials like The Modern Farmer make clear, black farmers have never been silent, passive or submissive in working to make these odds, well, unacceptable.

Sources:

Gordon Nembhard, Jessica. Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014.

Roll, Jarod. "The Lazarus of American Farmers": The Politics of Black Agrarianism in the Jim Crow South," in Beyond Forty Acres and a Mule: African American Landowning Families Since Reconstruction, edited by Debra A. Reid and Evan P. Bennett, Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2012, pp. 132 - 154.

The World of Jim Crow: A Daily Life Encyclopedia, edited by Stephen A. Reich. Greenwood, 2019 (https://books.google.com/books?id=ti6bDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA326&lpg=PA326&dq=Leon+R.+Harris+NFCF&source=bl&ots=skyrKCpGoq&sig=ACfU3U0u43uEPn0fRWIBhZ3u3DoMGiIcNA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjQstOJmvLnAhUZl3IEHWMIDywQ6AEwDnoECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=Leon%20R.%20Harris%20NFCF&f=false)

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cookbook History

(Title page from "The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy", London 1758, in the special collections of Mann Library, Cornell University)

Got assigned to make the sweet potato casserole for your big family gathering of the holiday season? Need some inspiration for your weekly meal prep? Just reach onto your book shelf and pluck out your favorite cookbook. Or, in these days of the internet, google your ingredients to find an almost infinite array of matching recipes at your fingertips. But it wasn’t always this easy. In the days of early antiquity, your success would have depended on who you knew, as recipes were primarily transmitted orally. In the Middle Ages, you would have had to be among the privileged classes to get your hands on manuscripts of collected recipes. It wasn’t until the advent of the printing press and increased literacy rates that access to cookbooks was democratized. And in the unfolding story of getting good food to the people, a leading part was played by this book: The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy, authored in 1747 “By a Lady.”

(Image of the frontispiece to “The Art of Cookery”, 1777 edition, from Wikimedia Commons)

It was later revealed that the author was, in fact, a lady: specifically an English dressmaker named Hannah Glasse, who helped usher in the development of modern cuisine by producing a cooking guide meant to be used by a wide swathe of an increasingly literate populace. Seminal though it was, Glasse’s cookbook could be considered “old-fashioned” in at least one sense: It included at least 200 recipes found to be plagiarized from other publications. At the dawn of Enlightenment, the culinary knowledge handed down through generations—via traditions of family life and food sharing—was still there for the taking, and Glasse apparently saw no problem in continuing the tradition of re-purposing other people’s recipes for her own enterprises.

The Art of Cookery contains hundreds of recipes, from puddings to gravies to food for the sick and hardy meals for voyaging sailors. Glasse purposefully used a conversational style of English in her book, avoiding the fancy French terminology associated with “high cuisine” at the time. Her stated aim with this approach: To ensure the book’s accessibility to people of any class. Asserts Glasse in her bold introduction, Cookery in hand, “…every Servant who can but read will be capable of making a tolerable good Cook, and those who have the least Notion of Cookery can’t miss of being very good ones.”

Over 40 editions of “The Art of Cookery” followed the original publication, and Glasse’s classic proved a popular hit beyond England as well, particularly in areas touched by British colonialism. But, in a telling example of the the back-and-forth nature of cultural exchange in a globalizing world, it didn’t take long for this seminal English cookbook to also be shaped by the foods and culinary traditions of far flung places. By 1774, a new edition of Cookery included a recipe for Indian "currey.” In 1805, an updated edition printed in Virginia, features quintessentially American ingredients such as maple sugar and pumpkin in dishes of a decidedly New World palette alongside the stoutly English fare.

(Recipe for Indian curry from the 1774 edition of “The Art of Cookery” from archive.org)

There are few records pertaining to the end of Glasse’s life, but it is known that she tragically plunged into debt over business troubles- so much so that she had to sell the copyright to her smash hit classic to make ends meet. While it isn’t known how much involvement Glasse had in later publications, The Art of Cookery continued to grow and develop as the years progressed- and came to mark an important milestone in the history of cooking: making good cooking accessible to the masses—which gives us yet another thing to be grateful for this holiday season.

References:

A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page over Seven Centuries, Henry Notaker, 2017

History of American Cooking, Merril D. Smith, 2013

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, Hannah Glasse, 1758

time.com/5218240/google-doodle-cookbook-author-hannah-glasse/

archive.org/details/b30502081_0002/page/100

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

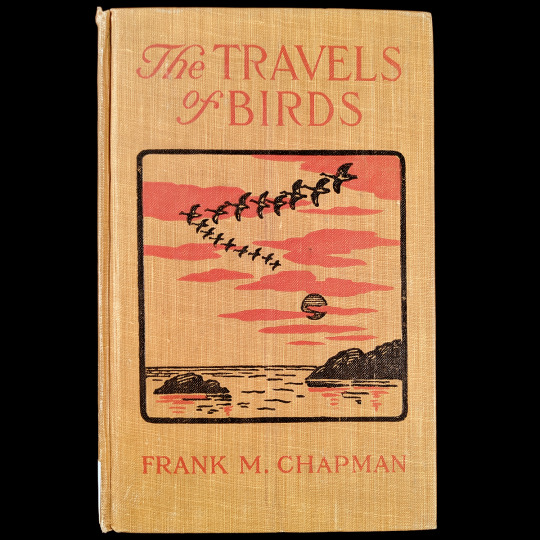

Bird travels

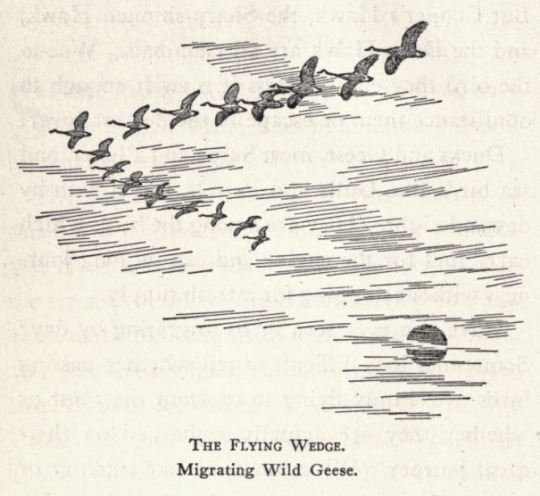

From the great white pelican to the snowy owl — birds spread their wings and flock southward in droves in the late summer and early fall. As the bird lovers among us would likely agree, few natural sights are as breathtaking as a group of cranes flying in a V-formation or a migrating group of snow geese, or even robins, which typically migrate in groups of less than fifty but sometimes gather in groups of hundreds or thousands. For those of us lucky enough to live near migration corridors, the sight of this fall phenomenon can captivate the mind and move the soul.

Over the centuries, many naturalists have attempted to better understand avian migration. One of these was early 20th century American ornithologist and author Frank Chapman. Chapman was a self-taught ornithologist from New Jersey – he is perhaps most well known as an early promoter of the photographic blind in bird photography, and for bringing the science of ornithology to the people through the use of non-specialized language and field guides composed with the bird-loving lay person in mind. As Frank Chapman observed in his lovely 1916 volume, The Travels of Birds, the study of natural history has been replete with thoughtful theorizing about the reasons behind bird migration, some of which have been a little out there (at least in the light of what we do currently know). Writes Chapman “At one time it was thought that some birds flew to the moon. Others, particularly the Swallows and Swifts, were believed to fly into the mud and pass the winter hibernating like frogs; while the European Cuckoo was said, in the fall, to turn into a Hawk.”

Such speculations may sound silly to us today, but the truth is, the facts of bird migration are indeed astonishing — bird populations seemingly disappear en masse overnight, make their way without a map or compass, across hundreds of thousands of miles of land and sea only to reappear every year, hale and hearty after winter’s last thaw. Thanks to insights gathered from careful scientific observation over the years, we now know that our feathered friends are able to navigate using a variety of methods such as a sun compass or olfactory cues, that migration is cued by factors like changes in day length, and that migration is driven to a significant degree by the seasonal availability of nourishment in different regions of the globe.

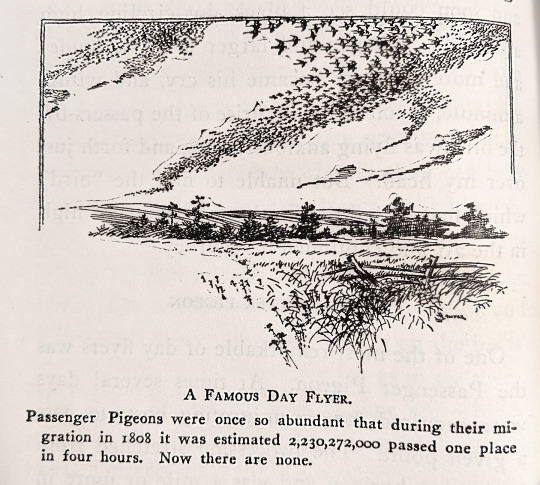

In Travels, Chapman takes a moment to ponder one of history’s most impressive migrants, the North American passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) whose day-flying migratory group — as observed in the early part of the 1800s at least — could reach flocks that were “a mile or more in width. Often the sun would be obscured by the clouds of flying birds." So great were the numbers of these birds in migration flight that hunters assumed the passenger pigeon would provide them with an inexhaustible supply of income — and used their rifles accordingly. Alas, passenger pigeons were hunted with such reckless abandon, and their deciduous forest habitat was sufficiently degraded during the course of the 19th century, that in less than 100 years, the death of the last known surviving passenger pigeon at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914 marked their final extinction.

So, while Chapman's lyrical volume about travelling birds does not fail in his goal of evoking in his readers a great (yes we'll call it soaring!) sense of wonder and appreciation about bird migration, it serves as a sobering cautionary tale as well. With brand new research by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology highlighted in Science Magazine just this month suggesting an alarming 30% decline in the general bird population of Canada and the United States since the early 1970s, it's a tale that we would be wise to take seriously to heart.

Sources:

wikipedia

audubon.org

catalog.hathitrust.org

#birds#migration#Ornithology#specialcollections#rarebooks#vaultsofmann#mann library#mannlibrary#passenger pigeon

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Missing Misses in Mycology

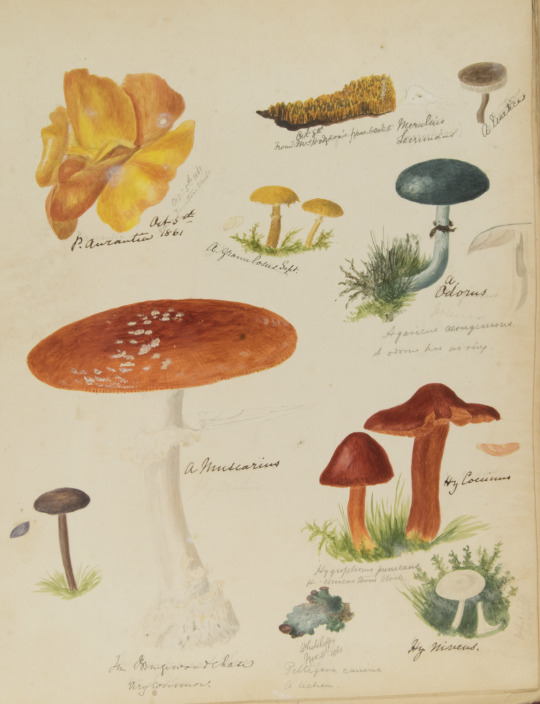

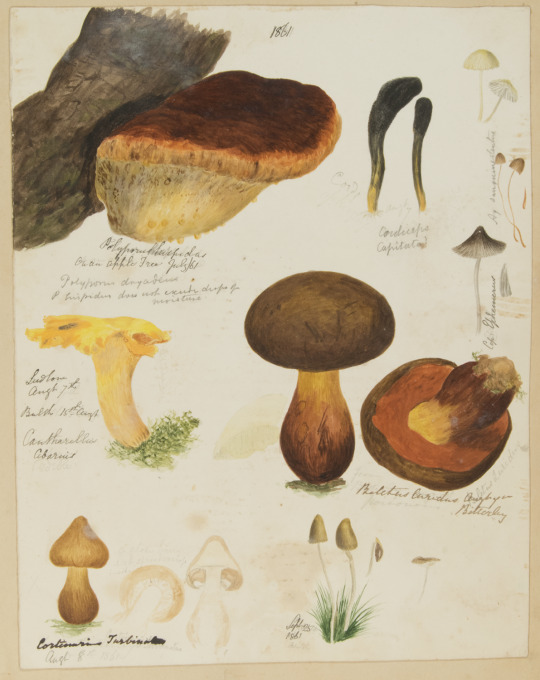

From: Fungi collected in Shropshire and other neighborhoods, by M.F. Lewis (1860-1903) in the Mann Library special collections.

It's no secret—the official history of science is a spotty narrative, flawed by frequent omission of the many contributions women have made to its advancement over the centuries. While we're now seeing considerable effort to rectify the record, the discovery of untold stories to fill in the blanks can be tricky business. It's not that the stories never happened — the field of botany, for one, is replete with some pretty spectacular evidence of women's (often unacknowledged) engagement with scientific inquiry, embodied in the detailed illustrations that captured the insights of observations from the natural world. But the published historical record is often woefully scant when it comes to closer detail on the lives and careers of the women who have helped carry modern science forward. For this month's Vaults of Mann blog — and in conjunction with a new exhibit spotlighting early women in botanical illustration that has just gone up at Mann Library — we hail a couple of exquisite gems from our special collections in mycology that speak volumes about women’s dedication to the creation of knowledge throughout history — and about the challenges involved in finding the missing pieces for a reliably accurate accounting of the mycological herstory.

From: Fungi collected in Shropshire and other neighborhoods, by M.F. Lewis (1860-1093) in the Mann Library special collections.

Open even just the first few pages of Fungi collected in Shropshire and other neighborhoods by M.F. Lewis and you'll be likely be smitten by this breathtaking 3-volume inventory of mushrooms identified over more than forty years (1860-1902) in the fields, forests, hills and valleys in various counties of England's West Midlands region in the late 19th century. Lewis' exquisite artistry is likely to persuade even the indifferent non-mushroom-enthusiasts among us about the curiously alluring beauty of this particular kingdom in life’s universe. The sheer number (over 300) and extraordinary variety of specimens included will leave you inspired by the wealth of fungi found in just one small corner of the world--a great lesson itself on the important but not always so readily visible biodiversity that can be found in our own backyards. And the care with which Lewis identifies the scientific name and place and date located for each species depicted will put you in awe of the painstaking devotion to data collection and taxonomy that this work represents.

From: Fungi collected in Shropshire and other neighborhoods, by M.F. Lewis (1860-1093) in the Mann Library special collections.

But who exactly was M. F. Lewis and what inspired her to produce this extraordinary study? What was her training? How did she work? And who did she work with over the four long decades that it took to complete her inventory? We may never know. Miss Lewis' work was never published—the 3 volumes in the Mann special collections appear to be a hand-bound set that includes the original watercolor drawings and field notes created by Lewis’ own hand. It did garner one mention by the English botanist William Phillips, who, in his essay on "The Hymenomycetes of Shropshire" in an 1880 issue of the Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, observes having been "permitted to look over [a work] of very much excellence executed by Miss M. F. Lewis, of Ludlow" and notes that "several rare species [of fungi] are very artistically represented." Aside from this single reference, however, Miss Lewis remains for us an elusive figure of mystery, a person whose (dare we call it) life's work proved her to be in possession of great talent, a keen eye, and an devoted dedication to the focused study of a fascinating subject of nature, yet who otherwise appears exceedingly difficult to find in the published record.

Clockwise from top left: Agaricus mutabilis Agaricus Laccatus, Lentinus cochleatus, Russula heterophylla, from Illustrations of the fungi of our fields and woods, by Sarah Price (1864-1865)

We also have in the Mann special collections a work by another English mycologist and science illustrator, Sarah Price, who, hailing from the town of Bitterly in Shropshire county (about 4 miles from Ludlow) happened to be not only Lewis' older contemporary, but also her virtual neighbor. Illustrations of the fungi of our fields and woods (1864-1865) offers an inventory of common mushrooms that Price found making the countryside in "her own neighborhood. around Shropshire...gay in their abundance." This study is a more limited one than Lewis' work--covering a little over hundred mushroom species only — but Price did manage to formally publish it as a slim 2 volume set thanks to funding provided by paying subscribers.

Among Price’s subscribers was William Jackson Hooker, then director of London's Royal Gardens of Kew, to whom Price dedicated, in her modest words, "this small contribution to the literature of botany." In addition to Hooker, about another 200 or so subscribers appear on the front pages of each of Price's volumes, many a "Sir," "Lord," "Reverend" “Colonel,” “Esquire,” and "Mr." among them, but also, a remarkably high number of "Ladies," "Misses" and "Mrs's." While, like M.F. Lewis, Sarah Price remains virtually invisible in the published record of British mycology, a review of her subscriber list (where women — not even counting those who appear as part of a couple — make up 53% of the names represented) makes it easy to imagine the presence of a kind of vibrant sisterhood in the Midlands region of 19th century England, a network of kindred spirits and bright minds sharing a common fascination with the secrets to be found in the nooks and crannies of the world around them--along with a determination to help discover them.

Polyporus beatiei, illustrated by Mary Elizabeth Banning, from Fungi: Mary Banning, at the New York State Museum.

In some ways, the cases of Lewis and Price recall the story of another remarkable woman who also toiled tirelessly to advance what we know about fungi, only this time on this side of the Atlantic. Mary Elizabeth Banning, born sometime in the 1820s in Talbot County, Maryland, received no formal training, but her family's moderate means allowed a basic level of childhood homeschooling that included some (clearly inspiring) nature study, possibly along with some Latin. As an adult, Banning became the sole breadwinner for her mother and half-sister and experienced a steady impoverishment of means over the course of her life. However these difficulties did not keep her from years of intrepid fieldwork hunting mushrooms across the state of Maryland, taking whatever form of public transportation available to her. Banning's passion prompted her to strike up a thirty-year correspondence with the mycologist Charles Horton Peck at New York State Museum of Natural History, to whom she sent many of her specimens and with whom she identified a number of fungal taxa. (Banning also identified 5 new species entirely on her own; and Peck wisely named one of the specimens that Banning had provided to him after the collector herself, Hypomyces banningiae). Convinced of the value of nature study for children's education, Banning worked long and hard on an illustrated study of Maryland's mushrooms, which she finished but was not able to publish before she died in 1903, in ill-health and living in a worn boarding house in Baltimore. Thanks to her connection with Peck, however, both a wonderful collection of her illustrations and the correspondence that detailed the story of her careful work were saved at the New York Museum of History, where, ninety years later, their discovery led to some well-deserved public recognition at last and the honor of being named to the Maryland Women's Hall of Fame.

It can be helpful to think of Banning's now more widely known story as a kind of proxy palette for very lightly coloring in some of the yawning blanks in the very incomplete picture we have of M.F. Lewis, Sarah Price and their engagement with the study of the mushroom kingdom. We can hope that the stories of Miss Lewis and Mrs. Price will also be eventually uncovered at some point, thanks to some intrepid future sleuth, willing to comb the town archives, local libraries and historical public records of rural England. In the meantime, we safeguard these women’s exquisite art and taxonomic work here at the Library, keeping their treasures accessible for future generations to enjoy — and to draw from as they embark on their own quests to better understand and appreciate this precious yet vulnerable planet that we call home.

Additional references:

Maroske, Sara; May, Tom W. (March 2018). "Naming names: the first women taxonomists in mycology" Studies in Mycology, Vol. 89, March 2018.

Mary Banning's Fungi of Maryland (1868-1888), New York State Museum; also see illustration collection at https://web.archive.org/web/20110710024009/http://www.nysm.nysed.gov/treasures/explore.cfm?coll=29&startRow=1&maxRows=12

#hernaturalhistory#mycology#women#botanical illustration#rare books#special collections#mushrooms#fungi#mann library#vaultsofmann

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beekeeping: From Amos to Z!

If you’re into beekeeping you likely know the name Amos Ives Root- the Ohio-born author and pioneering apiculturist who wrote “The ABC of Bee Culture” in 1879. The book in still in circulation today (although now titled “The ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture: An Encyclopedia of Beekeeping”) in its 41st edition and is affectionately nicknamed “The Beekeeper’s Bible” among bee-enthusiasts. “ABC” covers everything in regard to honey-bee rearing: from building hives to honey-harvesting, beekeeping implements, pollinator-friendly plants, biographies of noted beekeepers, and how to deal with pesky bears. A true A to Z of beekeeping!

As the story goes, Amos Root’s journey into beekeeping began on a warm August day in 1865 as a swarm of bees passed over Root’s worksite. An employee of his, recalling that Root had previously mentioned a desire to keep bees, offered to catch the swarm for him. Root was soon to discover that beekeeping is not an easy task, as his first swarm of bees was to fly off and abandon him. But he was not quick to give up! After much trial and error Root had his first successful hive, and four years later, in 1869, he decided to spread his passion for bees and founded the A.I. Root Company, producers of quality beehive and beekeeping equipment. He later went on to establish the publication “Gleanings in Bee Culture” and wrote his renowned book “The ABC of Bee Culture”. Impressively, all of Root’s accomplishments are still alive in some form. His beekeeping company would later switch to candle manufacturing, but Root Candles is still in business today and is run by Root’s great-great grandson (and produces some fine beeswax candles of course!). “Gleanings in Bee Culture” is today produced in magazine and online format and now known as “Bee Culture: The Magazine of American Beekeeping”. Last, but not least, of course the beekeeper’s bible “The ABC of Bee Culture”, while updated, is still a go-to for the modern beekeeper.

It was the efforts of early pioneers and inventors like Amos Root that laid the foundation for the modern beekeeping industry. Much has changed since Amos Roth’s time, but while the pollinators we rely on to produce over 75% of our food crop are in crisis and declining rapidly, we will need to summon that same gusto and tenacity as the early apiculture pioneers to help ensure their recovery and future health. Apiculturists like Amos Ives Root seemed to truly recognize the beauty of our pollinators and their supreme importance to all life. That isn’t a lesson we should be quick to forget!

References:

“ABC of Bee Culture”, Amos Ives Root, 1891

beeculture.com

rootcandles.com/

#specialcollections#bees#honeybees#pollinators#mann library#vaultsofmann#mannlibrary#rarebooks#scientific illustration#apiculture#beekeeping#entomology

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knitting for All

With the intense winter cold of the Finger Lakes and a yarn-bomb challenge we have going here at Mann Library, this last week of January has us on to a cozy topic—needlework and knitting. Whether as artisanal craft, high fashion design, or work of art, knitted creations have been the object of intense human focus and activity across time and culture. The earliest piece of true knitwear ever found—a knitted sock—dates from about 4th century Egypt, while ancient Mongolians were also known to have created knitted vests with abstract floral motifs to help ward off the bitter Central Asian winter cold. Distinctive knitting traditions developed in other corners of the globe following those early Near Eastern origins. Over the years—thanks to the work of artisans, fiber artists, designers and cultural historians—these traditions survived the process of industrial revolution to remain a solid, even resurgent part of culture today.

J. A Fleming’s How to Teach Needlework in Schools, published in 1887 by George Gill & Sons publishers of London, is a charming introduction to all types of needlework: from crochet to embroidery to knitting. It features lovely illustrations so the reader can easily follow along, like this one that shows the reader how to complete an exercise that will help them learn how to “cast on.”

For those of us new to the needle arts, in knitting, “casting on” is the process of getting the first loops, or row of stitches, on to the needle. Adversely, “casting off” is the act of finishing your last row of stitches so that your piece doesn’t unravel. Jane A. Fleming was an active English educator in her day, with a particular focus on promoting skills in sewing, knitting, and mending. In addition to authoring books such as How to Teach Needlework and Common-Sense Needlework, she contributed to the The Practical Educator, a British late 19th century monthly journal of advice and lesson material for teachers. We heartily recommend a browse through Fleming’s writings for a look at some beautifully clear and helpful guidance in some remarkably timeless (or, given today’s growing “maker” movement, perhaps better said, delightfully timely) life skills. Thank you Miss Jane!

How to Teach Needlework in Schools” is a rare book in the Mann Special Collections and may be browsed here at Mann Library via special request. Fleming’s Common-Sense Needlework has been digitized and made available via the library repository partnership known as the HathiTrust. To view there, visit goo.gl/xh8qBw.

#knitting#fiber arts#needlework#garment-making#yarn-bombing#rare books#special collections#vaultsofmann#mann library

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poinsettia

December 12th is Poinsettia Day! And so we celebrate the “Christmas Star” (as it’s commonly known) with an image from volume 85 of Revue Horticole. Poinsettias (Euphorbia pulcherrima) were introduced to the United States from Mexico in 1825 by Joel Roberts Poinsett, the first Ambassador to Mexico. Upon returning to the United States, Poinsett sent clippings of the plant to friends and botanists. In the early 1900’s a family of German immigrants, the Eckes, began producing poinsettias on a mass scale and selling them as Christmas decorations. The Ecke family were genius advertisers, incorporating the plants into magazine fashion shoots and giving them away to TV show hosts to get the plant in the public eye. Another fun fact about the poinsettia: The colored parts (the non-green ones that is) aren’t flower petals but bracts (or modified leaves). Deep red is the classically popular color for poinsettias, but they also come in pink and cream — as in this beautiful illustration from 1913 — as well as burgundy, and even marbled.

Revue Horticole was a French journal edited by the Société Nationale d'Horticulture de France, featuring botanical descriptions and gorgeous full color chromolithographs. This particular image was originally painted by the French painter Adolphe Millot and printed by the lithographer J. L. Goffart of Brussels.

A quick lesson on the chromolithography printing process: These words at the bottom of the image tell the story. “pinxit” (Latin for “he/she painted”) credits the artist who made the original painting while “lith” (lithographer) signifies the printmaker who reproduces and prints the image we see in the book.

A lithograph is created by an image drawn onto a smooth stone, which is then inked and printed on paper. A chromolithograph is a multi-layered colored lithograph, using many stones depending on the level of detail the printer wants. Chromolithography emerged in order to reproduce oil paintings in publications in mass quantities. When chromolithographs came onto the market they were referred to as “the democracy of art” because the medium was capable of a high quality reproduction for a low price. Although the quality of chromolithographs could vary, for those printers interested in high quality reproductions, it was possible to produce some stunningly gorgeous prints, such as this very poinsettia illustration!

Additional sources:

apsnet.org/publications/apsnetfeatures/pages/poinsettiaflower.aspx

The Ecke Poinsettia Manual, Paul Ecke, 2004

knoxhort.com/wp-content/uploads/Documents/Poinsettia-History.pdf

smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/how-americas-most-popular-potted-plant-captured-christmas-180949299/

#poinsettia#christmas star#horticulture#rare books#vaultsofmann#Mann Library#Cornell University Library

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bacteria Hunters

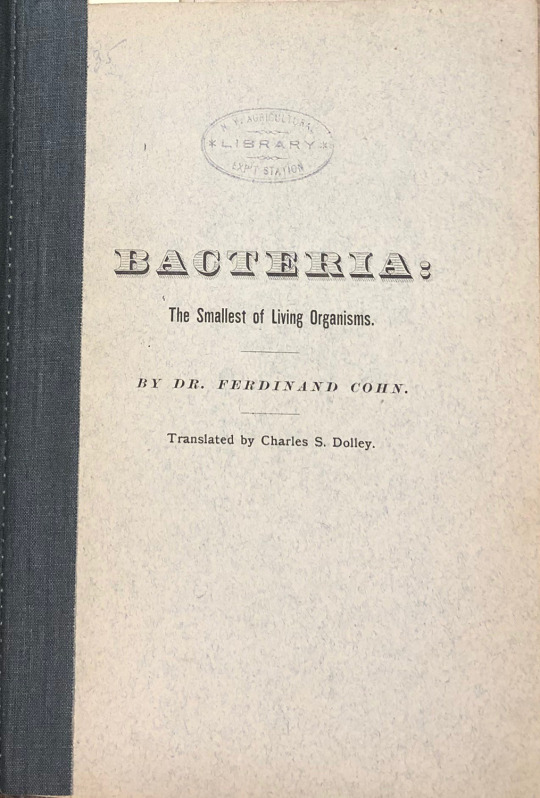

From: Bacteria: The Smallest of Living Organisms, by Dr. Ferdinand Cohn. Translated by Charles S. Dolley. Rochester, N.Y.: 1881 (from the special collections of Albert R. Mann Library, Cornell University)

Antibiotics Awareness week celebrated in November reminds us that it’s hard to imagine a world before antibiotics. The early 20th century discovery of the “magic bullet” rocked the medical world and turned once deadly infections into a quick trip to the doctor’s office. The problem now is that diseases once effectively treated with antibiotics are mutating and returning even stronger. It turns out the magic bullet can be over-prescribed and overused, and overuse causes resistance and stronger bacteria. At a time when dangerous super-bacteria are drawing increasing attention of the world’s microbiologists, we turn our special collections spotlight to some key foundational work for the field of bacteriology done by a 19th century German scientist.

Image reproduced from: "Bacteria: The Smallest of Living Organisms," translated by Charles S. Dolley, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, January 1939, via jstor.org (https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/44440427.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A4129cd9688644f0c8cbfcf67fb8c40a9)

Ferdinand Cohn was a botanist who earned himself lasting fame with the essays on bacteria that he first began publishing the early 1870s in Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen, a journal he had just launched as professor and director of the Institute of Plant Physiology at the University of Breslau (now known as the University of Wrocław in Wroclaw, Poland.) Cohn's most widely acclaimed essay "Über Bacterien, die kleinsten der lebenden Wesen" was also published in 1876 as part of a German series of popular science lectures, where it caught the eye of American medical student Charles S. Dolley at the University of Pennsylvania, who hoped to help make the "best writings in medicine and science" from the German and French medical literature more widely available to aspiring young American scientists-in-training. Dolley's translation, "Bacteria: The Smallest of Living Organisms," first appeared as a limited edition pamphlet published in Rochester, N.Y. in 1881, and was later picked up by the Johns Hopkins University Press in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine (January 1939).

Pamphlet from the special collections of Albert R. Mann Library, Cornell University

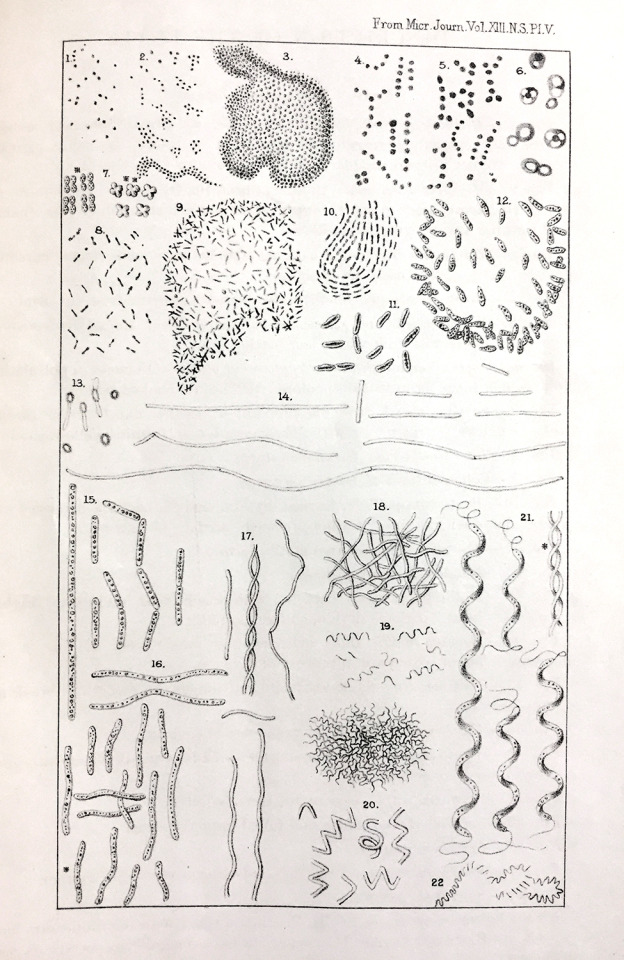

Don't let the size — 31 pages — of this slim publication fool you, for it summarizes profoundly important insights that the botanist had achieved in his study of algal, bacterial, and fungal microorganisms. With his work, Cohn established a robust definition of bacteria as chlorophyll-free cells that could be classified into four basic morphological forms — cocci, bacilli, vibrios and spirilli (see the illustration at the beginning of this blog for the visuals he provided along with that classification). He gave decisive intellectual weight to an understanding of bacteria as form-constant species in their own right, rather than organisms that evolve into something else. And Cohn recognized for the first time that some bacteria can undergo a spore stage—a stage in which otherwise actively reproducing bacteria cells assume a dormant form that allows them to survive exposure to unfavorable physical (e.g. high heat) or chemical (e.g. antiseptic agents) environments .

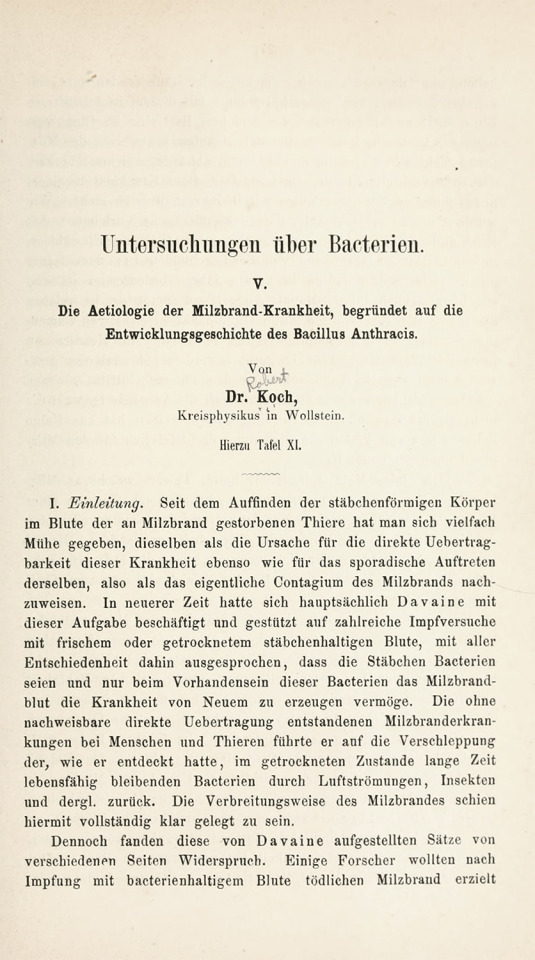

It's hard to overstate the importance of Cohn's analysis for the major breakthroughs in bacteriology that ensued. By the mid-1870’s Cohn’s ingenious work had attracted the attention of a young country physician, Robert Koch, whose research on anthrax was quietly laying the groundwork for modern medicine's understanding of bacteria as causative agents of infection. Cohn became a key supporter of Koch’s research, publishing Koch's seminal paper about bacillus anthracis in his Beiträge journal series in 1876, and also collaborating with him in some further studies. The rest is glorious science history, as the insights achieved by both scientists proved fundamental to all the later work establishing effective ways to treat bacterial infections, including of course Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in the late 1920’s.

From: Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen, vol. 2, no. 1, 1876. This seminal paper by Robert Koch, published in Ferdinand Cohn’s botany journal, established the causal relationship between bacillus anthracis and anthrax infection.

As microbiologists of today turn their attention to the problem of increasingly antibiotic-resistant super-bugs, it’s easy to imagine their intellectual forbears, the Cohns, Kochs, Flemings and the other greats of modern bacteriology, cheering them on — with no small sense of urgency — in their important work on behalf of global health. We might also do well to imagine these giants of science history reminding us that the global public has its own role to play in understanding how bacteria work and what steps we can take in our own habits and industry practices to hold the line against growing antibiotic resistance. For further thoughts on that, be sure to check out the info pages by the Center for Disease Control and the World Health Organization.

Additional references:

Drews, Gerhart, "The roots of microbiology and the influence of Ferdinand Cohn on microbiology of the 19th century," FEMS Microbiology Reviews, Volume 24, Issue 3, 1 July 2000, Pages 225–249, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00540.x

“Ferdinand Cohn, German Botanist,” Encyclopaedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ferdinand-Cohn

Gradman, Christoph, "Cohn, Ferdinand Julius," https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/doi/10.1038/npg.els.0002386

Leikind, Morris C., Introduction to "Bacteria: The Smallest of Living Organisms," translated by Charles S. Dolley, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, January 1939, via jstor.org (https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/44440427.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A4129cd9688644f0c8cbfcf67fb8c40a9)

Seidensticker, Oswald, Introduction to Ferdinand Cohn's "Über Bacterien, die kleinsten der lebenden Wesen" German Scientific Monographs for American Students, Boston: Henry Holt & Co., 1889, via hathitrust.org (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hxdcmt;view=1up;seq=7)

#antibioticsawareness#bacteriology#microbiology#Ferdinand Cohn#Robert Koch#special collections#rarebooks#vaultsofmann#mann library

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spider Curious

We don’t need Tolkien’s fantastically horrifying Shelob or his monstrous spiders of Mirkwood Forest to remind us that people find arachnids—even at their natural sizes—among the most fearsome creatures of the natural world. So in the spirit of spooky late October fun we've dug out a few creepy crawlies from The Natural History of Spiders and Other Curious Insects (1736), by 18th century painter and water colorist Eleazar Albin (d. 1742?).

Page through this entomological rarity, and you’ll make the acquaintance of over 180 spiders, most from England but some also from other corners of the world (South Africa, the Philippines, Suriname, among others). You won't learn their names though. Drawing from his own "ocular observation" (probably in good part via various private specimen collections), Albin provides accounts that detail the shape, color, size, and sometimes behavior of each spider depicted, but does not attempt to sort out species identification. To Albin's time, the art of taxonomy was, after all, a very young science still. Proceed to the chapter-like appendices — penned by physician Richard Mead and famed natural philosopher Robert Hooke — you get up-close-and-personal views of tarantulas, scorpions, and, somewhat incongruously, a range of fleas and lice associated with a variety of birds. The inspiration for this intriguing if somewhat discomfiting volume, as declared by author Albin in his introductory notes: A desire to provide a reliable account of the spider species that would “instruct our understanding and gratify our commendable curiosity.” Thanks to this work, and his earlier treatise, The Natural History of English Insects (London, 1720), Albin has been recognized by at least one team of science historians as "one of the great entomological book illustrators of the 18th century." (Salmon, et. al., quoted in Wikipedia).

Figure 173: A spider from the Cape of Good Hope. “These foreign large spiders have ten legs besides the forceps, all our English spiders having but eight. They are said to spin a web so strong between the branches of the trees as is able to intangle the humming-birds, which they kill and devour.” [Note: Albin mistakes two of the spider’s appendages, the short pedipalps on either side of the jaws at the top, for legs. By definition of course, spiders are 8-footed creatures].

So how did Albin—whose first paying job was that of teacher of painting and drawing in the bustling city of London—come by his success as an early pioneer of English science illustration? One lucky break came when the young artist’s life path crossed with that of Joseph Dandridge, a successful fabric pattern designer who was also respected as an amateur botanist, entomologist and collector. As Dandridge (himself a talented if possibly time-strapped illustrator) relied on Albin to render some of the choice caterpillars and other specimens gathered during expeditions across the English countryside, their collaboration provided the artist with access to a widening circle of British intellectuals, aristocrats and other wealthy patrons who would eventually become paying subscribers for several ambitious natural history projects of his own. Ultimately, Albin had five illustrated natural history works to his name, which in addition to Spiders and Insects, included, A Natural History of Birds (1731) , Natural History of English Songbirds (1737), and The History of Esculent Fish (published posthumously in 1794) , —no shabby life achievement.

Among others, the Empress of Russia. Taking care to include a celebrity-studded subscriber list in his introduction to Spiders, Albin was clearly not above stoking some 18th century FOMO as part of his marketing strategy.

While clearly adept at tapping into the wealth of England’s upper crust to make his work possible, Albin was not one born with a silver spoon in his mouth. The specific date and place of his birth are unclear, but he appears to have been born in Germany and come to London as an immigrant in either his child- or early adulthood. In London, he ended up with a large family to support (ten children in all), and their residence on Golden Square, SoHo, "next ye Green Man near Maggots Brew House," was likely not conducive to forging easy connections with the city's monied class. Yet a large family also provided some important resources. Albin's daughter, Elizabeth, and possibly his son (or son-in-law) Fortin contributed some of the lovely artwork in Albin's volumes. And according to at least one contemporaneous natural historian (James Petiver), Albin was known to use a surprisingly effective secret ingredient in mixing up the pigments for his artwork: boys' urine. No shortage of that agent in a household with five boys!

Spider no. 178: “The back, belly, legs and feelers of this large Spider were of a yellowish brown, with marks of a darker shade of the same color; its forelegs were longer than any of the others; its feelers were oddly sloped like claws of a lobster, with which it would lay hold of any thing it had a mind to.”

Albin beat some considerable odds in the unforgiving social environment of 18th century England to achieve respect as a natural history illustrator in his lifetime, but there’s a murky side to his story as well. In the late 1960's, some intrepid sleuthing by British science writer W. S. Bristowe yielded a troubling discovery: It appears that the spider illustrations in Albin's 1736 work were essentially copies of an unpublished set of "delicately executed and often excellent" illustrations by Albin's mentor Joseph Dandridge, which were found tucked away in the archives of the British Museum. Bristowe takes Albin severely to task (to the point possible with someone who’s been dead over 200 years) for failing to include even a hint of attribution to Dandridge's work is in his Spider volume. Now to be fair, Dandridge was very much still alive and kicking — "far from being in his dotage" as Bristowe puts it — when Albin published Spiders, and Albin's appropriation appears to have elicited none of the justifiable outrage one might have expected from his mentor or any of his other contemporaries. At least not anything that's been recorded in the history books.

And for your frontispiece, why not a put portrait of the author riding a fine horse among an array of mites, scorpions, tarantulas and other spiders!? One can’t, of course, help wondering about he inspiration behind this composition. An eccentric sense of grandeur ? A surreal sense of humor? Or maybe a need to express some wry commentary on the way this particular project had taken over the author’s life? Your guess!

Regardless of the specific story behind his Spider work, it’s clear that Albin labored greatly in life to achieve the results he did. Perhaps Joseph Dandridge felt sorry enough for hard-toiling Albin—and appreciated his zeal for the natural history project enough—to cut his erstwhile mentee a generous break and forgive him his piracy; perhaps Dandridge owed Albin some kind of intellectual debt stemming from their years of collaboration; or perhaps Albin contributed to Dandridge's original spider drawings in ways that he himself had not yet been able to acknowledge.

We may never know the full story behind this apparent act of 18th century intellectual property theft. But it's a good cautionary tale in the month of October in any case. While the entomologically unenlightened among us may still find spiders profoundly scary creatures, there's nothing like a cry of plagiarism to send shivers of horror into both the halls of academia and the world of publishing. And almost surely, that is a very good thing.

Additional references:

Albin, Eleazar. A Natural History of English Insects. 1720 Bristowe, W. S., "The Life and Work of a Great English Naturalist: Joseph Dandridge," Entomologist's Gazette, Vol. 18, No. 2 (April 24, 1967), pp. 71-89 Bristowe, W. S., "More About Joseph Dandridge and His Friends James Petiver and Eleazar Albin," Entomologists Gazette, Vol. 18, Nos. 3 & 4, pp. 197-201. Osborne, Peter (2004): "Albin, Eleazar (d. 1742?)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. Weiss, Harry B., "Two Entomologists of the Eighteenth Century--Eleazar Albin and Moses Harris," The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 23, No. 6 (Dec., 1926), pp. 558-564

Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Dandridge https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleazar_Albin

#spider#arachnid#insect#entomology#natural history#rarebooks#mannlibrary#vaultsofmann#cornelluniversitylibrary

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death in the Pot!

For a large serving of the sinister and spooky this Halloween, dig no further than this morbid title from Mann’s Special Collections: Deadly Adulteration and Slow Poisoning or, Disease and Death in the Pot and the Bottle. Published in London, around 1829 by an anonymous author self-described as “An Enemy of Fraud and Villainy”, this volume caused quite a stir at the time. While the title may suggest some kind of “How-To” for the murderously inclined, this work was actually intended to publicize the use of chemicals and unsafe practices in the production of common food items such as tea, flour and medicines.

Many later historians of food safety believe this work was actually the last-ditch effort of Friedrich Accum to get his message across to ordinary citizens. Accum was a German chemist who wrote in English and whose many scientific publications were influential in the popularization of chemistry during this era. Earlier in 1820, Accum had published his “Treatise on Adulteration of Food” to both great acclaim – and outrage. The cover was imprinted with a skull-and-crossbones above a spider sitting in the center of an intricate spiderweb.

And what about that catchy headline: Death in the Pot? This is a Biblical reference (2 Kings 4:40), which started to appear in the early 1700s in medical treatises and books about food contamination.

For a closer look at our creepy collections you can request to view both volumes from Mann’s special collections: http://mannlib.cornell.edu/use/collections/special/registration

Deadly Adulteration and Slow Poisoning, Anonymous, c1829, Call Number TX563.D27.

A Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons, Accum, Friedrich Christian, 1820, Call Number TX 563. A17 1820.

#pagefrights#food#contamination#public health#rare books#special collections#mannlibrary#vaultsofmann

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fraisier souchet

Happy National Strawberry Day from Mann's Special Collections!

This rare beauty is from Pomologie française: Recueil des plus beaux fruits cultivés en France, by Antoine Poiteau (1766-1854).

Botanical artist Antoine Poiteau (1766-1854) is among the greatest masters of the golden age of botanical illustration that flowered during the late 1800s and early 19th century. In addition to the artistic beauty of his work, Poiteau contributed a scientific accuracy to pomological illustration that was unrivaled by other botanical illustrators of his time.

The illustrations in Pomologie française specifically are considered to represent a high point in the genre of pomological art, which traces its original inspiration to the great Flemish still life paintings of the 16th and 17th centuries.

The Mann Library is one of only four libraries in the United States that owns the full 4-volume set of this work.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 1920 student protest against coeducation at Cornell: “Does This Mean “Sex-War”?

In the fall of 1920 a group of male students tried to end coeducation at Cornell University, the oldest private coeducational institution in the country. This demand, and the immediate responses to it, are presented in the article “Does This Mean ‘Sex-War’”? by Genevieve Parkhurst, published in the March 1921 issue of The Delineator, a leading women’s magazine of the era which is included in Mann Library’s Special Collections. The article gives a fascinating window into not only the incident at Cornell, but of the larger contemporary debate on the evolving status of women in the United States in the aftermath of World War I and the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment (August, 1920) as well as the position Cornell University took in the midst of it all.

Cornell University was founded o the principal of coeducation, and although this was not official policy until 1872, both Ezra Cornell and A.D. White were vocal in their support of Cornell as an institution open to all. This was despite significant skepticism of the very idea from many contemporaries. Dr. Edward Clarke of Harvard Medical School published his popular “Sex in Education” in 1873, asserting that coeducation was harmful to women’s reproductive health, rendering them infertile, or at least generally unfit for marriage and family life. Despite these kinds of concerns and objections, moral arguments, financial realities, and a general expansion of education, both primary and secondary, helped grow coeducational institutions over the following decades. Additionally, when male college enrollment dipped due to the first World War, larger numbers of women students were admitted than ever before, largely due to financial necessity at many schools. By 1920 more than half of all existing colleges in the United States offered coeducation, and women comprised 47 percent of college students. While female students were generally seen as diligent, and often outperformed their male counterparts scholastically in many subjects, the very success of women at these schools, and the numbers at which they were beginning to enroll, produced a backlash. Women at prestigious schools such as Stanford, Wesleyan, Duke, and Cornell had always experienced some level of discrimination in classes and activities, and sometimes faced open hostility from male students and faculty. The events of the fall of 1920 at Cornell, when a group of male students rose up to demand an end to coeducation, was one of the significant instances where women’s place at elite universities was directly and visibly challenged.

The Cry “What will happen when the women equal and outnumber the men?”

On November 30th, 1920 nine male undergraduate Cornell students, claiming to represent the student body as well as alumni interests, published a declaration against coeducation in the Cornell Daily Sun. This effort was reportedly also supported by some minority of the faculty.

The publication of the Cornell student’s ukase in November followed a demonstration in Bailey Hall on Thanksgiving Day where fraternity members raised an image of the women’s Sage Hall and then hissed their protests. This was apparently but one instance in a fifteen-year history of sporadic remonstration of the presence of women in Cornell’s student body, and the perceived threat to the University’s prestige presented by their numbers. Cornell was at the time unique in the Ivy League in its coeducational status. “Yale and Harvard laugh at us because we’re a sissy school” one student supporter of the cause stated. The rest of the Ivy was at this time still firmly and proudly ensconced in their system of single-sex education, as they would remain for another fifty some years, opened their doors in the nineteen-seventies, and in the case of Columbia, nineteen-eighties. In contrast, May Preston, the first woman to earn a Ph.D. at Cornell, did so in 1880.

The inclusion of women at Cornell was criticized in 1920 for a variety of reasons, prominent among them the perceived lowering of the athletic prowess of the University following defeats to Penn and Dartmouth in football that season. A puzzling degree of upset was also voiced over an incident in which female students reportedly sang Cornell songs on a Hudson ferry-boat. This incidence was referenced several times in “Does This Mean Sex-War” in quotes from male students filled with outrage at the indignities of coeducation. Another enumerated insult was increasing female competition in academics, specifically that there were twice as many female students at Cornell in 1920 as there had been in 1915, and that these women were very focused on their studies and had a high rate of success in winning awards, honors, and scholarships. Out of 310 Cornell honor students in 1920, 90 were women, while the student ratio was about one woman to every five men. In Arts and Sciences, twenty-four of fifty scholarships went to women, with a college enrollment of 340 men and 67 women. One can only assume that the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which had given women the right to vote on August 18, 1920, further fueled these men’s sentiments. The twin fears of a perceived threat to existing power structures, and a loss of academic and professional opportunities seems to underlay this desire to exclude women from the system entirely.

The Response Coeducation: “the hottest educational controversy of the times” or “beyond discussion”

While the group that brought forth the protest was small, and when pressed, unsupported by any formal organization on campus, the male revolt at Cornell had in its inception every hope of succeeding. Wesleyan University, founded in 1870 as an all-male institution had turned coed in 1892, but then in 1905 the University reversed its inclusionary policy and become all-male again, a condition which persisted all the way until 1970. The rest of the Ivy League was staunchly all-male and would proudly remain so for another 50 years. The University of Chicago, lauded as a pioneer in coeducation, had segregated into male and female classes in 1902. While Stanford was coeducational, its student ratio was legally fixed at no more than one woman to every three men. Numerous colleges and universities classified as coeducational admitted just handfuls of women students for decades. The presence of women at Universities, particularly elite universities, was in no way assured.

“Does This Mean Sex-War” states that the “significance of this disturbance is indicated by the strong stand taken immediately following it by educators all over the United States,” and quotes letters on the subject from prominent academic administrators such as Dr. Charles Eliot, the president emeritus of Harvard University, and President Wilbur of Stanford. Western and mid-Western public universities, as well as Stanford, all coeducational, stood behind the system on both practical and moral grounds, while Dr. Eliot of Harvard decried the very idea that men and women intermingle in educational settlings after the onset of puberty. In this article Dr. Eliot is the lone voice in favor of exclusively single-sex education however. Dr. James R. Day of Syracuse University is quoted as saying: “It seems to me that it is rather a late date, when woman is taking her larger place in affairs which have been exclusively managed by men and is addressing herself to the larger question of humanity and civilization, for us now to segregate her in higher education.”

Most significant perhaps for the outcome of this attempted coup on coeducation at Cornell was the response from Cornell’s leadership, other students, as well as from the town of Ithaca itself. President Albert W. Smith immediately sent a letter for publication in the Cornell Sun reminding the students that Ezra Cornell endowed the university with the proviso that its halls would be open to all, and that when Henry W. Sage made his endowment in 1873 it was with the condition that “instruction shall be afforded to young women…as broad and as thorough as that now afforded to young men.” He went on to state that while everyone is entitled to their own opinion, if a student or faculty member is not able to “accept coeducation and treat women students fairly,” then he should go elsewhere.

The Cornell faculty gave a joint statement that the demand was “an outrage.” The larger student body, reportedly most prominently and vocally among them the Agricultural College, the School of Medicine and the College of Architecture also “rallied to the defense” of the women. The fraternities, groups to which the nine named instigators belonged, remained silent on the subject. The newspapers of Ithaca, representing the sentiments of the town, decried this silence, ultimately forcing statements of repudiation and distancing from the instigators by the fraternities as well.

And in all this, what was the response of the women at Cornell? Apparently a “dignified” silence. The (lack of) response by the women was lauded by all interviewed for the article. “Their silence should shame their opponents into capitulation” said President Smith. “They are holding themselves superior to the attack made upon them” said Miss Georgia White, Cornell Advisor of Women. “The girls…must maintain their splendid attitude of tolerance and amusement” said Martha Van Rensselaer, head of the Department of Home Economics. It must be noted however that the women’s silence yet continued presence at the University was in no small part possible due to the vocal rejection provided by the University administration, faculty, student body, and even the town of Ithaca. It would appear that for women and their right to higher education at Cornell back in the day, the Cornell University administration and Ithaca area community had their backs.

Although official silence was apparently maintained by the female students, Martha Van goes on to note that in response to the men’s statement that they would now only take local girls and visitors to school dances, the women decided to boycott these dances. One significant exception: The Agricultural Assembly at Cornell, which the women would attend because there, says Martha Van “they are sure of being given the right sort of welcome.”

After 1920, as national college enrollment expanded generally, women's share of the student population began to shrink. Women comprised 47 percent of college students in 1920, but nation-wide their percentages dropped over the ensuing five decades, with exception of the WWII period. It is interesting to note that as shown in the table below, this trend does not seem to hold as true at Cornell. In the 20 years following the “sex-war” the rate of female enrollment seems to outpaces that of male enrollment, which in turn shows a slight downward trend for a decade or so after the failed coup. One can wonder how these things might have been related. Today Cornell’s undergraduate population is 52% women.

#vaultsofmann#womeninhighered#cornell university#special collections#gender#gender struggles#gender studies

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nature and Knowledge: A Century of National Parks and Nature Study

“[N]ature study…lead[s] us through the border-land of knowledge into the realm of the undiscovered.” -Anna Botsford Comstock from Handbook of Nature Study (1911)

“The Father of Our National Park System" John Muir (1838-1914) was perhaps this country's most famous and influential naturalist. Muir shared his ideas and experiences in nature through publication in four popular and influential monthly magazines: Scribner's, Atlantic Monthly, Harper's, and Century, inspiring the protection of wild places for all, laying the groundwork for the formation of the National Park Service, founding the Sierra Club and underpinning the modern conservation movement. What Muir conveyed so beautifully in prose was his wonder and deep spiritual connection to nature. Muir's grandfather helped kindle this relationship from his early boyhood in the Scottish countryside, and after Muir at age 11 emigrated with his family to Wisconsin to farm, his unofficial nature lessons continued in the new land. (You can read more about those formative years in Muir’s charming “The Story of My Boyhood and Youth” publicly available on-line through the Biodiversity Heritage Library).

Muir went on to study biology, botany and geology at the University of Wisconsin, but soon left formal classroom study behind to venture cross country and eventually to every continent save Antarctica to experience and understand the natural world first-hand. With a plant press in his backpack, Muir walked more than 1,000 miles from Kentucky to the Gulf of Mexico, gathering specimens along the way. Later in Alaska, he carefully observed the movements of glaciers. Living for years in Yosemite he discovered glaciers there and was the first to suggest that ice, not earthquakes, had shaped its valleys.

In many ways Muir’s experiential road to understanding was an exemplification of the learning style put forth by the nature study movement of the early 20th Century: achieving greater knowledge of natural systems and laws through careful observation of, and connection to, the natural world. A contemporary of Muir’s, Anna Botsford Comstock (1854-1930) was moved by many of the same ideas he was, and is considered an influential early conservationist in her own right. Botsford Comstock’s “Nature Bible” as her Handbook of Nature Study (1911) has been called, was central in the nature study movement and encourages investigation and experience in nature as a teaching tool that does far more than simply convey information. Although her preface to Handbook of Nature Study states that “Cornell University’s Nature-Study propaganda was essentially an agricultural movement in its inception and its aims” in the first paragraphs of the work she writes: “… nature-study gives the child a sense of companionship with life out-of-doors and an abiding love of nature. Let this latter be the teacher’s criterion for judging his or her work”.

Nature-study, as outlined in this handbook, encompasses all living things, as well as all non-living things such as rocks, minerals, weather and climate. Anna Botsford Comstock took the view that we should know first and best the things closest to us, and then, armed with a deep understanding of these things we can better understand more distant things. She also encouraged an organic form of study whereby students are encouraged to follow their own interests, writing: “In nature study the work begins with any plant or creature which chances to interest the pupil.”

The 900-page tome that is Handbook of Nature Study is certainly quite the hefty “handbook,” a fact the author apologizes for in the preface but says “it does not contain more than any intelligent country child of twelve should know of his environment…”. At the time of first publication no commercial publisher would take it on. John Henry Comstock, Anna’s husband, published it through their Comstock Publishing Company even though he believed it would be a financial disaster. The book has since gone through twenty-five editions, has been translated into eight languages, and is still in print, appreciated, and used today.

Botsford Comstock argues that what is needed for greater understanding and knowledge is curiosity, careful observation, and a willingness to make the learning experience immersive and free. She writes “ the object of the nature-study teacher should be to cultivate in the children powers of acute observation…”

Comstock was influenced from childhood by her Quaker mother's love of nature, and her childhood spent in rural Otto, NY. As an undergraduate at Cornell University majoring in literature, she also took a zoology class from John Henry Comstock, became his close friend, later married him and returned to Cornell for a degree in natural history. She went on to learn wood engraving so she could illustrate an entomology textbook her husband was writing, then to not only illustrate, but also write parts of his second book, A Manual for the Study of Insects (1895) and then several more books, both collaboratively with her John Henry, and on her own.

A writer, artist, teacher, and public speaker, Anna Botsford Comstock also became in 1920 the first woman to earn the rank of full professor at Cornell. She became good friends with Martha Van Rensselaer, fellow Cornell professor and founder of Cornell’s innovative and influential Department of Home Economics (which later became the College of Human Ecology) who is thanked in the preface of Handbook. In 1923 both of these remarkable ladies were named by the League of Women Voters as amongst the twelve greatest living women in America. Hear history come alive with an excerpt of the letter Anna wrote to her friend Martha celebrating this remarkable and joyful occasion here. The special copy of Handbook of Nature Study (1911) held within the Mann vault is from the personal collection of Martha Van Rensselaer and contains a brief dedication from “The Author” and the signature of her friend and colleague.

The Handbook of Nature Study remains a relevant and valuable tool for teachers and parents, maybe all inquisitive humans, even all these years later. Several copies of more recent editions of The Handbook of Nature Study are available for check-out at Mann Library. Alternatively, you can download the full text here.

And perhaps you can celebrate 100 years of National Parks by taking advantage of free admission to all 412 national parks (from August 25 through August 28) then make sure to take the time to breathe in its wild beauty and observe the details with a child’s curiosity and sense of wonder. Just think what you might discover!

"When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe."

- John Muir

#vaultsofmann#special collections#nature study#national parks#cornell#education#early women#CALS#cornellCALS

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Cryptic Language of Flowers

From Flora’s Dictionary (1829)

Planning on giving that special someone flowers for Valentine’s Day? Perhaps it is time to brush up on your floral language skills. A bouquet for your sweetheart could express a nuanced and tender sentiment, but also an unintended, even shocking message. Give some myrtle and you are expressing love, but pair it with a sunflower and suddenly your message is: “Your love is like false riches, not worth professing.” Giving your love a chrysanthemum? If it is rose colored, it means “I love”, but if yellow “slighted love”. A variegated poppy: “flirtation”. Purple hyacinth: “jealousy”. Ivy: “matrimony”. The possible combinations are dizzying.

From The Language of Flowers (1825)

All this according to the Language of Flowers, or floriography, the art of communicating sentiments through carefully chosen flower and herbal arrangements. This cryptic language saw its glory days in Victorian-era Europe and North America, and accompanied a general growing cultural interest in botany. Gifts of specific floral arrangements also allowed the sender to communicate sentiments which could not be spoken aloud under the strictures of proper Victorian society. Using floral dictionaries, Victorians often composed even every-day messages through the gift of small bouquets called tussie-mussies, which could then be worn or carried in public to acknowledge receipt of the message.

Flora’s Dictionary includes hundreds of meanings for various species and shades of flowers, including 12 pages of wildly different meanings for roses (from “Love” to Disdain” and even “War”!) depending on type, shades, thorns, and state of bloom.

From Flora’s Dictionary (1829)

Floriography was popularized in France as early as 1810, while in Britain it caught on around 1820, and in the United States by about 1830.The first dictionary of floriography appeared in 1819 when Louise Cortambert, writing under the pen name 'Madame Charlotte de la Tour,' wrote Le langage des Fleurs. British floral dictionaries soon followed, including Henry Phillips' Floral Emblems published in 1825 and Frederic Shoberl's The Language of Flowers; With Illustrative Poetry, in 1834. Robert Tyas’ The Sentiment of Flowers; or, Language of Flora, first published in 1836, was considered the English version of Charlotte de la Tour's book. In the United States Elizabeth Wirt's Flora's Dictionary and Dorothea Dix's The Garland of Flora were the first books to popularize the concept of a language of flowers.

From The Language of Flowers (1825)

During its peak in America, the language of flowers attracted the attention of the most popular women writers and editors of the day, and there were many books and magazines dedicated to the subject.

The remarkable Language of Flowers Collection at Mann Library was once the personal library of award-winning garden writer and Cornell Alumna Isabel Zucker ’26. Following Mrs. Zucker’s generous donation of this collection to Mann Library, her daughter Judith Zucker Clark ‘53 supported initial conservation treatment of this beautiful and historical collection. The 147 volumes in this collection include the classics Le langage des Fleurs by de la Tour, Phillips' Floral Emblems, Shoberl's The Language of Flowers; With Illustrative Poetry, Wirt's Flora's Dictionary and Dix's The Garland of Flora, as well as many other exquisitely illustrated floral dictionaries, books of sentimental verse, and moral fables from 19th century Europe and North America.

9 notes

·

View notes