#unseen revolution of agriculture technology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A profound transformation is silently unfolding within the expansive realm of agricultural practice, where terrestrial and celestial realms converge to orchestrate life cycles. This metamorphosis is propelled by the convergence of technological advancements and traditional methodologies, with the Internet of Things (IoT) emerging as a potent catalyst reshaping longstanding agricultural paradigms. This paper elucidates the burgeoning landscape of IoT integration within agriculture, delineating its multifaceted implications for enhancing operational efficiency, ecological sustainability, and productivity within this critical sector.

Discover the expertise of CA Mukesh Shukla, the best business coach in India, dedicated to empowering entrepreneurs and fostering self-reliance among the youth. With a passion for developing entrepreneurship skills and contributing to the Atma Nirbhar Bharat Abhiyan, CA Mukesh Shukla offers unparalleled guidance and support for business growth. Learn more about his journey and transformative impact on the Indian economy at CA Mukesh Shukla's official website

#agriculture#revolutionizing agriculture#agriculture technology#modern agriculture#sustainable agriculture#revolutionizing agriculture with ai#ai in agriculture#precision agriculture#smart agriculture#agriculture revolution#modern agriculture technology#artificial intelligence in agriculture#iot in agriculture#irrigation in agriculture#agriculture innovation#advanced agriculture solutions#unseen revolution of agriculture technology

0 notes

Text

Exploring the Invisible World: Insights into Ecological Microbiomes

In the vast expanse of our planet, an unseen world thrives beneath our feet, within our bodies, and around us in every corner of the environment. This world, composed of trillions of microorganisms, plays a critical role in maintaining the delicate balance of ecosystems. Welcome to the fascinating realm of ecological microbiomes.

What is a Microbiome?

A microbiome is a community of microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microscopic life forms, that inhabit a particular environment. These microorganisms are incredibly diverse and can be found in almost every habitat on Earth, from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains, and even in extreme conditions like hot springs and polar ice caps.

The Role of Microbiomes in Ecosystems

Microbiomes are essential for the health and functioning of ecosystems. Here are some key roles they play:

Nutrient Cycling: Microorganisms break down organic matter, releasing essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus back into the soil and water, making them available for plants and other organisms.

Decomposition: They decompose dead plants and animals, recycling nutrients and maintaining soil health.

Disease Suppression: Certain microbes protect plants and animals from diseases by outcompeting or inhibiting the growth of harmful pathogens.

Climate Regulation: Microbes influence global carbon and nitrogen cycles, playing a part in climate regulation by sequestering carbon and producing greenhouse gases.

Human Impact on Microbiomes

Human activities, such as agriculture, urbanization, pollution, and climate change, have profound effects on microbiomes. Pesticides and fertilizers can alter soil microbiomes, reducing their diversity and functionality. Urbanization can lead to the loss of natural habitats and the microbiomes they support. Pollution, such as plastic waste and oil spills, can drastically change marine microbiomes, affecting entire ocean ecosystems.

The Human Microbiome

Not only are microbiomes vital to environmental health, but they are also crucial for human health. The human microbiome, particularly the gut microbiome, is essential for digestion, immune function, and overall well-being. Imbalances in the gut microbiome have been linked to various health issues, including obesity, diabetes, and mental health disorders.

Studying Microbiomes: A Technological Revolution

Advances in DNA sequencing technologies have revolutionized our understanding of microbiomes. Metagenomics, the study of genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples, allows scientists to identify and analyze the diversity and functions of microorganisms in different habitats. This technology has opened up new possibilities for microbiome research, from discovering new species to understanding complex microbial interactions.

The Future of Microbiome Research

The study of microbiomes holds great promise for addressing some of the most pressing challenges of our time. By understanding and harnessing the power of microorganisms, we can develop sustainable agricultural practices, restore degraded ecosystems, combat climate change, and improve human health.

Conclusion

The invisible world of ecological microbiomes is a frontier of scientific discovery that has far-reaching implications for the health of our planet and ourselves. As we continue to explore this hidden realm, we gain insights that can help us create a more sustainable and healthy future.

Important Information:

Conference Name: 14th World Gastroenterology, IBD & Hepatology Conference Dates: December 17-19, 2024 Venue: Dubai, UAE Email: [email protected] Visit: https://gastroenterology.universeconferences.com/ Call for Papers: https://gastroenterology.universeconferences.com/submit-abstract/ Register here: https://gastroenterology.universeconferences.com/registration/ Call Us: +12073070027 WhatsApp Us: +442033222718

0 notes

Text

INITIAL RESEARCH INTO PLAY

‘Deeper than gender’.....‘seriously, but dangerously fun’ – New York Times

The type of play I will investigate further is ‘Free (spontaneous) Play’. Free Play is the freedom to act creatively in any way for self-enjoyment, without fear of judgement or for an end goal.

In this blog I want to investigate the connections between play, creativity and art and design. I believe that all forms of art and design are an extension of play. I want to explore the idea that in the future play could be revered above economic concerns and that society could take advantage of technology in the future to allow people to enjoy playing.

To play

1. engage in activity for enjoyment and recreation rather than a serious or practical purpose.

- amuse oneself by engaging in imaginative pretence.

- engage in (a game or activity) for enjoyment.

2. take part in (a sport).

3. be cooperative.

- fiddle or tamper with.

4. represent (a character) in a theatrical performance or a film.

5. perform on (a musical instrument).

6. move lightly and quickly, so as to appear and disappear; flicker.

Play in childhood:

Through carrying out my research I have found many ways of thinking about play, one of which is to see it as solely a children’s activity. Stuart Brown, author of ‘Play’, states that ‘Play is seen as a rehearsal for adult activity.’ He suggests that this belief is ‘powerfully wrong.’ The conversation surrounding play is that most often it is referred to as being a separate activity, not something to be mixed in with everyday life.

Children gain knowledge through their play. They exercise their abilities to think, remember and solve problems. Play is performed for self-amusement and it has behavioural, social, and psychomotor rewards. It is child-directed, and the rewards come from within the individual child; it is enjoyable and spontaneous. Play in childhood is important for our survival. It teaches us about the world by learning through cause and effect. Child psychologist Margaret Lowenfeld believed that children were better able to express themselves through play than words. It has also been shown that exposure to metaphor and symbols, as used in play, has a beneficial effect on the development of the brain.

There are different types of play:

Physical play - exercise

Expressive play - drawing, playing instruments,

Manipulative play - master their environment - object

Symbolic play - symbolise child’s feelings

Dramatic play- act out situations

Familiarization play

Games - rules

Surrogate (spectator) play - watching others play

Play in adulthood

When we grow into adults, we are encouraged to lose the sense of play and become more aware of other people’s opinions and their judgement of childish behaviour. When people see me playing around in one way or another I am told to ‘grow up’ or ‘act my age’ by adults. This prohibition on play in adulthood becomes shockingly apparent when my friends stop question themselves when playing - “what are we doing, we are 19 years old, this shouldn’t be happening’

In Tim Brown’s Ted talk ‘Tales of Creativity’ he performed an experiment with his audience members - a 30 second drawing task to draw the person next to each member of the audience. The audience members then showed the drawing to their partner and there was a lot of laughter and a lot of people saying sorry. Brown stated this was evidence that we fear the judgement of our peers and this fear is what causes us to be conservative in our thinking. When children underwent the same experiment they were not embarrassed.

This experiment demonstrates a loss of the freedom to express ourselves without the fear of judgement we had as a child. By editing our ideas and playful thinking when adult we no longer take creative risks. The majority of adults give up play for other pursuits such as careers. An adult life is stressful and busy. The rejection of play in our relationships, professions, alone time means we are not inducing the pleasure that play gives people.

In our society the opposite of play is typically seen as work. However, Stuart Brown argues that the opposite of play is depression. He argues that our species has evolved to value play throughout our whole lifetime.

Imagine a world without play.

Play in the future

Play could play an important part in the future of our civilisation. With technology advancing at an exponential rate more and more processes are being automated. People used to work in the fields until the agricultural revolution brought in machinery to boost production which reduced the number of manual labourers needed on farms.

The equivalent happened in the factories - the first wave of industrialisation saw an influx of the rural population move into towns and cities to work in factories. However, many factory jobs have recently been lost to machines and robots that do the same job more efficiently.

A future looms where humans become obsolete in the industrial functioning of our societies. What will humans do to pass the time? This is where we might consider something that is inherent in our psyche, beneficial to our well-being, encouraging activity and social interaction - play!

Wall-e, 2008

The film ‘Wall-e’ shows a potential future in which human life is safely in the hands of robots. The humans sit on hover lounge chairs behind holographic screens, incredibly overweight. Even now many people are inactive in front of screens. In an alternative future this time spent being inactive and vegetative could be spent active in play. Imagine that without the need to pursue time consuming and stressful careers, we will have the freedom to return to the joyous way of living we experienced as children.

Play as a thing in itself is arguably something that humans do not fully understand. It has certainly never just singularly one thing. I believe the need for play is immediate throughout our life. We need to stop separating it into thinking in terms of an action that children need and adults don’t need or of separating play and work.

Through my investigation I will see how I can have an impact on people’s lives with ideas for play and for environments that encourage play.

The Welcome Collection exhibition

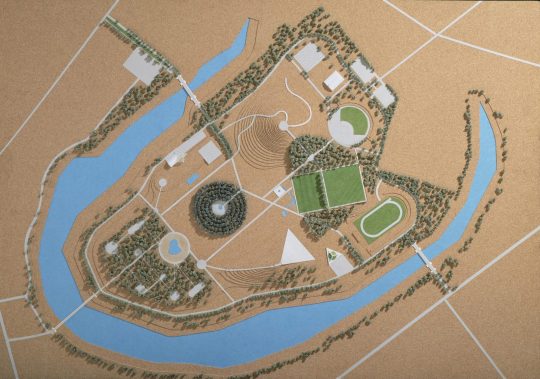

The layout of the exhibition, designed by Andres Ros Soto, was inspired by the philosophy of designer Isamu Noguchi, who created playscapes that would inspire a will to play rather than dictating one to play.

It showed a historical explanation of children and play and how play has influenced society.

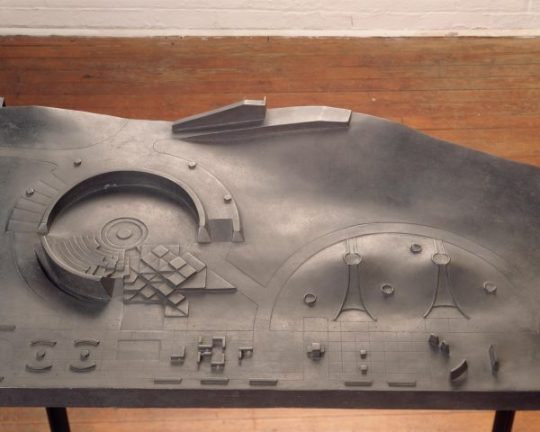

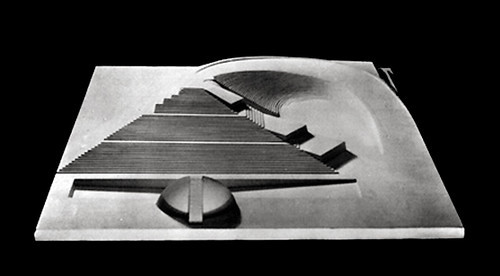

Isamu Noguchi (design) and Shoji Sadao (architect). Moerenuma Park, Sapporo Japan. 1988-2004.

Playground Architecture

A specific play-based architecture for children has developed over the years. It began with children in Post-war Britain exploiting the existing bombed out plots of land for their own imaginative games. Children’s rights pioneer Marjory Allen, a landscape architect by profession, began the adventure playground movement after seeing junk playgrounds in Copenhagen in 1945. The Danish children made these play structures themselves out of waste material,

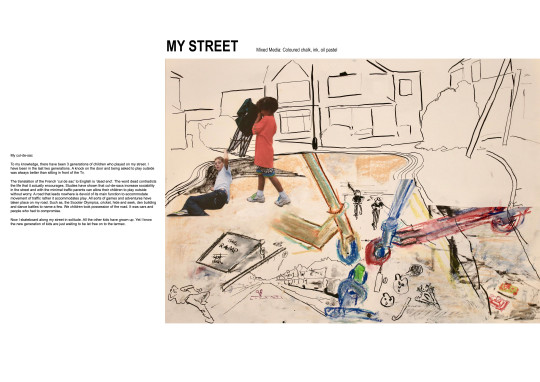

I used to play on my road with my neighbours as a child. We would make ad hoc structures for spontaneous play situations. I still go out and skateboard on my homemade ramps in my cul-de-sac which is a relatively car free street. A cul-de-sac or, in English, ‘dead end’ is far from dead. Cul-de-sac streets increase spontaneous outdoor activity by children because of the reduced danger from traffic.

Toys

In the 20th century children often made their own toys. Children would build functioning go-carts, dolls and sling shots. Now Toy manufacturers design and make toys for children.

There is an ongoing debate on whether designed toys are better than toys that havent been designed. This debate is similar to the design of spaces and the implications they have on the imagination.

Play Club

I run an afterschool club at Kingston Foundation for anyone who wants to join. We take over the ampitheatre in the new Town House building and get involved in playing. This constitutes games, performance, improvisation, movement, singing and more. Each week is spontaneous and unplanned. The activities in the sessions come about through what people suggest, how people are behaving, and what the room on that certain occasion is offering and spontaneous ideas of how to direct a group of people.

The space we are in really influences what we do and somewhat makes play club possible.

Town House - a building for play

Town House, Grafton Architects

Town House library: A stirring, open-plan library where students can ‘meet and fall in love’

The hope, says Yvonne Farrell, who with Shelley McNamara, founded Grafton, is to create “a social spiral” rising up the building, to allow the “kind of abrasion” of different people doing different things, which “is what a university is”

What makes the Town House an interesting and exciting place is the large open spaces, maze like structure, multi-levelled benches, lots of nooks and crannies - windows to the other floors so people can become an unseen audience.

Play Club has been running for 4 weeks

· 1st week - games, rules, expression

· 2nd week - more acting based, creating characters using comedy and creating narratives storytelling, pretending

· 3rd week - team challenge - communication and collecting, creating

· 4th week - improvisation

Play Club would come under what Stuart Brown would call the 'imaginative play' archetype - storytelling, painting, drawing, crafting, and acting, as well as comedy and improvisations.

Monster Chetwynd

Chetwynd is known for her vibrant, energetic and playful performances.

youtube

‘Brain Bug Performance’

‘Uptight upright upside down’ video footage from Videodrome by Cronenberg and Woody Allen’s Purple rose of Kyro with 1700 Japanese shunga art.

Chetwynd said in an interview that, ‘amateurism in my opinion is something that’s quite refreshing’. This goes against the idea that play leads to invalid things and not valuable or wanted. Chetwynd wants the audience to get lost in all the different things that were happening to the point that they give up and don’t know or care what was going on and lose their inhibitions. Chetwynd says her art practice leaves room for spontaneity

Play is not productive. It is freewheeling. It is not an activity with set objectives or targets. When learning through play one cannot develop the same level of perfection in a skill as someone who practises a skill systematically such as an athlete, for example, who trains with the goal of perfecting a particular skill with the aim of reaching a certain target.

Skateboarding

By skating through the city, I have become fascinated by the built structures that become instruments for skating tricks. I see the various infrastructures, such as roads, courtyards, traffic islands and pavements, and street furniture such as benches, ledges, bollards, levels and staircases from the viewpoint of someone who uses the furniture to create propulsion. At the same time, I have begun to think about the materials and the forms of these elements.

The skater uses his imagination and experience to convert the infrastructure just like a child will turn a wooden box into a space station or a pirate ship. The city becomes a skaters’ playground. Skateboarding is done by all ages from children to adults and the 60s and overs.

As a skateboarder, I carry a childish curiosity when I walk through the city always looking out for skateboarding opportunities. I intrinsically view the city in a subverted eye - an eye looking for continual play. I look at the infrastructure of roads and where they meet pavement, walls, banks stairs, squares and courtyards and I question them, assess their material quality, dimensions. And context. It has given me a visual language of the forms that make up the metropolitan space. The consequence being I have become more and more interested in architecture.

Lyon, Hotel De Ville Plaza

London, Southbank Undercroft

Skateboarding was originally a children’s fad, or an activity for slackers and bums. Now, unfortunately, it has become a career option where you can earn a lot of money through skateboarding competitions. More importantly for me it has become an art form and a way of living which still involves play.

As a skateboarder you are in conflict with the conventional uses of the city. Skateboarding is understandably noisy and fast, it dirties the surfaces and is just annoying to other people. Skateboarding is an active force on the ideas of inclusivity and exclusivity of the public and private area.

Similarities can be drawn with the reduction of roaming spaces for children and the conflict between privately owned spaces and the public and poses questions on who has the right to occupy an urban space and how it should be used. With aggressive interventions like skate-stoppers being added to ledges, handrails, stairs it is a visible attack against skateboarding.

Skate-stopper on ledge

Herzog and de Meuron

My favourite building in London is the Blavatnik Building by architects Herzog and de Meuron. The face turns on the base giving it a confusing cascading lift to the sky. The slices of windows that wrap around the building open up the floors for light. The sloping floor on each level guides you to walk up and through the building like a helter skelter. Within the whole of the Tate Herzog and de Meuron have made it spacious and open. They give you the possibility to move through the space how you will.

The slope in the Turbine Hall often showcases many different types of play. People rolling down, car races, running races and other such games enjoyed by all others.

When I am in the Tate Modern I feel as if I can express myself freely in any way and really use the space to play. In the Tanks of Tate Modern, a friend and I found ourselves sliding across our bellies on the smooth polished concrete floor. This resulted in a lot of laughter.

The Tate Modern is a place to see art and not a place to work. However why can’t all buildings hold the potential to have possibility for play embedded in their architecture.

Another notable building by Herzog and De Meuron was their Toadstool Serpentine Pavilion that I visited when I was younger. I used the space to run around, climb and explore the different levels and crevices of the cork surface.

The 56 Leonard ‘Jenga Tower’ building in New York by Herzog and de Meuron is lifted straight out of childhood experiences. The building references the early skills children learn about structures through playing with wooden blocks. The building of structures teaches children about constructing structures. I partook in this type of object play often as a child and continue in 3D specialism. I believe object play has directly influenced my interests and my ambition to study architecture next year.

0 notes

Text

The Accidental Superpower: The Next Generation of American Preeminence and the Coming Global Disorder by Peter Zeihan: Conversation Starters - London Sky Press

The Accidental Superpower: The Next Generation of American Preeminence and the Coming Global Disorder by Peter Zeihan: Conversation Starters London Sky Press Genre: Study Aids Price: $3.99 Publish Date: December 21, 2018 Publisher: LS Seller: Pay Per Talk, Inc The Accidental Superpower: The Next Generation of American Preeminence and the Coming Global Disorder by Peter Zeihan: Conversation Starters Geopolitics was a central factor in the global politics of the early 20th century but was relegated to the sides when political theorists paid more attention to economics, ideology, and technology. As the world advances into the 21st century, geopolitics will continue to play a major factor in the success of powerful nations, particularly the United States. The US' natural waterway networks, rich agricultural land, and its two oceans inevitably make the country a global superpower. It is not like China which has geographic features that make the country susceptible to political fragmentation. The shale oil revolution in North America will further enable the United States to continue having the superpower edge for many more years to come. The Accidental Superpower is a book that follows in the bestselling tradition of The Next 100 Years and The World Is Flat. Critics view it as an eye-opening look at America as a superpower. A Brief Look Inside: EVERY GOOD BOOK CONTAINS A WORLD FAR DEEPER than the surface of its pages. The characters and their world come alive, and the characters and its world still live on. Conversation Starters is peppered with questions designed to bring us beneath the surface of the page and invite us into the world that lives on. These questions can be used to create hours of conversation: • Foster a deeper understanding of the book • Promote an atmosphere of discussion for groups • Assist in the study of the book, either individually or corporately • Explore unseen realms of the book as never seen before Disclaimer : This book you are about to enjoy is an independent resource to supplement the original book, enhancing your experience . If you have not yet purchased a copy of the original book, please do before purchasing this unofficial Conversation Starters . Download your copy now on sale Read it on your PC, Mac, iOS or Android smartphone, tablet devices. http://bit.ly/2EJuYbc

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://fitnesshealthyoga.com/what-is-crispr-cas9-the-revolutionary-gene-editing-tech-explained/

What is CRISPR-Cas9? The revolutionary gene-editing tech explained

Until very recently if you wanted to create, say, a drought-resistant corn plant, your options were extremely limited. You could opt for selective breeding, try bombarding seeds with radiation in the hope of inducing a favourable change, or else opt to insert a snippet of DNA from another organism entirely.

But these approaches were long-winded, imprecise or expensive – and sometimes all three at the same time. Enter CRISPR. Precise and inexpensive to produce, this small molecule can be programmed to edit the DNA of organisms right down to specific genes.

The development of cheap, relatively easy gene-editing has opened up a smorgasbord of new scientific possibilities. In the US, CRISPR-edited long-life mushrooms have already been approved by authorities while elsewhere researchers are toying with the idea creating spicy tomatoes and peach-flavoured strawberries.

But the game-changing technology could have the biggest impact when it comes to human health. If we could edit out the troublesome mutations that cause genetic diseases – such as haemophilia and sickle-cell anaemia – we could put an end to them altogether. The path for human gene-editing is littered with controversies and tough ethical dilemmas, however, as the news in late 2018 that – against all ethical guidance – a Chinese scientist had secretly created the first gene-edited babies.

Here’s everything you need to know about the complex and sometimes controversial technology driving the gene-editing revolution.

What is CRISPR?

CRISPR evolved as a way for some species of bacteria to defend themselves against viral invaders. Each time they faced a new virus, bacteria would capture snippets of DNA from that virus’ genome and create a copy to store in its own DNA. “They gather a set of sequences that they’ve been exposed to,” says Malcolm White, a biologist at the University of St Andrews, “these [bacteria] essentially carry a little library in their genome.”

To stick with the library analogy, these snippets of viral DNA were like little books – each one containing the data that allowed the bacterium to recognise and quickly kill off a virus next time it invaded. And in-between these chunks of useful DNA there are slightly less useful chunks of repetitive DNA keeping them separate – like a kind of molecular bookend.

These repeating segments of DNA are what gives CRISPR its name – Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat – but it’s really the bits between these repeats that make CRISPR so useful. These useful bits are, somewhat unhelpfully, called spacers, and each one contains a reference to the DNA of a virus the bacteria (or its ancestors) had come across in the past. When a previously unseen virus attacks the bacterium, it adds another spacer to its library of previous attacks.

When a virus from that same species attacks again, the spacer corresponding to that virus’ genome swings into action. It’s a bit like the way that our own immune systems can recognise a flu virus if we’ve had that year’s flu vaccine. The spacer sequence is turned into RNA – a molecule that contains messages from DNA – and hunts down the corresponding piece of viral DNA. Once it finds it, an enzyme attached to the RNA string acts as a pair of biological scissors, cutting the target DNA and rendering the virus harmless.

You might have heard this system referred to as CRISPR-Cas9 as well as just plain CRISPR. In this case, the Cas9 bit refers to the enzyme used to cut the target DNA. “We can programme [Cas9] very easily to target one DNA sequence and to be very specific so it won’t cut anything that’s even similar in sequence,” says White. There can be other kinds of enzymes involved in gene-editing – Cas12 and Cpf1 for example – but all of them work in the same basic way.

How does it work?

Of course, all this is only useful if you’re a bacterium. So how do we turn an anti-virus defence mechanism into something that could let us edit human genomes at will?

Rather than relying on bacteria to create the molecules for them, scientists have worked out how to create their own versions of the CRISPR molecules in the lab. To start with, they need to work out the section of DNA that they want to target. For a condition sickle-cell anaemia, which is caused by a fault in a single gene, this is relatively easy, since we’ve already sequenced the gene that causes this disease and so know exactly the genetic code that we’re trying to target.

The banana is dying. The race is on to reinvent it before it’s too late

Before we get down to the business of unzipping and chopping up DNA, it’s worth getting to grips with the basics of how DNA is structured. Holding together the familiar DNA double-helix are four different nitrogen bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G) and cytosine (C). The ordering of these bases determines everything about us, genetically-speaking. Eye colour, how tall we’re likely to be, whether we’re susceptible to certain diseases, it’s all written out in base pairs in our genetic code.

Like teeth on a zipper, these bases always pair up with their complementary base. A always pairs with T while G always pairs with C, over and over again until you’ve got to the three billion base pairs that make up the human genome.

But DNA isn’t much use staying locked up in a double helix – it needs to get that information out there and into the cell where it can be used to create proteins, which are the building blocks of pretty much everything in our bodies. To do to this, DNA unzips itself, breaking apart those base pairs until they’re flapping about in the cell.

These flapping, momentarily unpaired base pairs match up with short segments of RNA which contain their own own bases. RNA shares three bases with DNA – G, C and A – but T is alway replaced by U (uracil). Similar base-pairing rules apply, so an exposed DNA G base will pair with an RNA C base while a DNA A base will pair with a U. If you have an exposed DNA sequence of GAC, for example, you’ll end up with an RNA sequence of CUG.

Scientists use these basic principles to create their own CRISPR molecules which, as we pointed out above, are short stretches of RNA. All you need to do is open up a stretch of interesting-looking DNA – like the bit that contains the mutation that leads to sickle-cell anaemia – and build the complementary RNA sequence, with DNA-chopping enzyme attached. It’s a bit like starting with one side of a zipper and using that to build the corresponding but opposite side of the zipper that neatly fits into it.

Once you’ve got your CRISPR molecules, you need them to get your target cell. Luckily, viruses love nothing more than injecting stuff into other cells, so popping CRISPR molecules into otherwise benign viruses is one particularly useful way of introducing CRISPR into cells that’s already been put to work with in numerous studies involving mice.

Now CRISPR-Cas9 can really get to work. The Cas9 enzyme starts by unzipping bits of the DNA double helix while the RNA molecule sniffs its way along the exposed base pairs looking for a perfect match. Once the perfect match is found, Cas9 cuts out the troublesome gene before repairing the remaining bits of DNA. Other enzymes can add in insert genes instead of deleting them, but the basic process of unzipping, recognising and editing remains the same across different CRISPR molecules.

What is CRISPR used for?

CRISPR is particularly attractive to the agricultural industry, which is always looking for a way to engineer disease- and weather-resistant crops which will increase yields and, subsequently, their profit margins. In October 2015, plant biologists at Pennsylvania State University in the US presented US Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulators with button mushrooms that had been edited so they go brown a lot more slowly than normal mushrooms.

A year later, the USDA confirmed that the same mushrooms would be cultivated and sold without having to pass through the agency’s regulatory process for genetically-modified foods. Now, non-browning mushrooms are hardly the most thrilling foodstuff, granted, but this USDA is a pretty big deal because it hints that CRISPR-edited crops might be able to sidestep some of the environmental backlash levelled at GMO crops.

And it’s not just mushrooms getting the CRISPR love. In Australia, one scientist has already used CRISPR to make bananas resistant to a deadly fungus threatening to decimate the world’s crop of the fruit, while others are working on using the technology to create naturally decaffeinated coffee or finally engineer the perfect tomato.

Timeline: When was CRISPR discovered?

2005

After characterising CRISPR in 1993, Francisco Mojica at the University of Alicante in Spain became the first to hypothesise that the DNA sequences were part of bacteria’s adaptive immune system.

2007

Scientists at Danisco, a Danish food research firm, proved experimentally that CRISPR was part of a bacterial immune system and that Cas9 inactivates the invading virus.

2011

Emmanuelle Charpentier’s group at Umeå University in Sweden demonstrates the role of tracerRNA in guiding Cas9 to its cellular target.

2012

Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna at the University of California, Berkeley simplify the CRISPR system by fusing together different elements into a single, synthetic guide

Although the agricultural world provides some of the furthest-along examples of CRISPR in action, the stakes are much higher when it comes to human health. Animal studies are already underway to use CRISPR to tackle sickle-cell anaemia and haemophilia – two promising candidates for CRISPR-treatment because they’re determined by a relatively small number of mutations. In the case of sickle-cell anaemia, the condition is caused by just the mutation of a single base pair in one gene.

The more genes involved in a condition, the harder it becomes to use CRISPR as a potential solution. “There are not many human diseases where only one gene is mutated,” says White. Certain cancers, for instance, are linked to multiple mutations in different genes, and often the link between genetic mutations and cancer risk are poorly understood so there’s no guarantee that – even if we could use CRISPR to fix faulty genes – that’d it’d be any kind of panacea for cancer.

Why is CRISPR controversial?

Late last year, He Jiankui, a researcher the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen shocked the scientific world when he claimed responsibility for the world’s first CRISPR-edited human beings. He reportedly took embryos from couples where the father was HIV-positive and the mother HIV-negative and used CRISPR to edit the gene controlling a protein channel that HIV uses to enter cells.

The experiment – which was detailed in a YouTube video, not a peer-reviewed journal – was widely condemned by scientists. “It’s been widely acknowledged that the science is not yet ready for clinical application,” says Sarah Chan, a bioethicist and director of the Mason Institute for Medicine, Life Sciences and the Law at the University of Edinburgh said at the time. “More has to be done to resolve uncertainties, and to try and understand the risks.”

Although the He study does violate clear ethical boundaries, it does raise one of the big ethical conundrums when it comes to CRISPR. The problem is that it’s not that easy to use CRISPR to change your genome once you’re an adult – you’d need to find some way of introducing the molecules to every single target cell.

This is perhaps achievable for conditions like sickle-cell anaemia, where you only need to change the DNA in red blood cells. By using CRISPR to edit bone marrow – where red blood cells are produced – you might be able to target a relatively small percentage of cells and still fix the condition.

But if you want to change a person’s entire genome, you need to edit their DNA when they’re little more than a tiny cluster of cells. This leads to all kinds of ethical issues. Why stop at identifying and chopping out genetic diseases, for instance, if we could also tweak an embryo’s DNA so the resulting baby was more likely to be intelligent, or good-looking?

“What if we wanted to change future life span, or intelligence, or Alzheimer’s disease potential or whether they go bald when they get to middle age,” says White. “Societies going to have to come to terms with what we want – it’s not up to scientists.”

Although human gene-editing raises some of the biggest ethical questions, things aren’t an awful lot clearer when it comes to agriculture. In July 1018, the European Court of Justice threw the future of gene-edited crops into doubt when it confirmed that CRISPR-edited crops would not be exempt from existing regulations limiting the cultivation and sale of genetically-modified crops.

Crops that have been genetically-modified – usually by inserting a gene from one organism into another – have long been sidelined in Europe, despite their popularity in other parts of the world. Despite a scientific consensus that GM foods are safe to eat, headlines warning of ‘frankenfood’ and lobbying from environmental groups helped keep GM crops away from human consumption.

But agricultural advocates for CRISPR hoped that the new gene-editing technology would provide an opportunity to redress this balance. The ECJ ruling means that any CRISPR-edited food that is to be grown or sold in the EU must pass stringent safety tests that non-edited crops (or crops made using certain techniques like radiation mutation) do not have to face. For now, at least, one of the biggest barriers facing CRISPR isn’t science, but public relations.

More great stories from WIRED

– Why the UK’s porn block is one of the worst ideas ever

– Wedding shaming Facebook groups are the real-life Mean Girls

– Glasgow cured violence by treating it as a health epidemic

– Upgrade your sound with our guide to the best headphones

– The best Black Mirror episodes ranked

Get the best of WIRED in your inbox every Saturday with the WIRED Weekender newsletter

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s) if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments); if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0'; n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0]; s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script', 'https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); fbq('init', '181847449123027'); fbq('track', 'PageView');

Source link

0 notes

Text

CHESTERFIELD DESCRIBED DIRT AS MATTER OUT OF PLACE

You need a town with the right personality. While we're on the subject of static typing, identifying with the makers will save us from another problem that made it hard to come up with startup ideas on demand. So why do founders chase high valuations? Batch after batch, the YC partners warn founders about mistakes they're about to make, but are absolutely lousy if you don't. Preferably with other students. Most companies that VCs invest in angel rounds—partly because the startups we funded were able to raise significant funding after Demo Day. It discovered, of course, have to change and keep changing their whole infrastructure, because otherwise the headers would look as bad to the Bayesian filters as ever, no matter what they did to the message body, which is why this trend began with them. It made them hate working for the acquirer. Google nor Facebook were even supposed to be the kind of effervescent feel that attracts the young.

It's not uncommon for investors and then watching how they do, I can now look at a group we're interviewing through Demo Day investors' eyes. Wanted: Woman with hammer. If so, this revolution is going to make it so that you can't say what you planned to, but to be an illusion. NYC hunting down and understanding their users. Which is not that Intel or Apple or Google have offices there, but that they won't even fund them. It's hard for such people to design great software, because they might end up with two large hash tables, one for each corpus, mapping tokens to number of occurrences. For example, back at Harvard in the mid twentieth century as a golden age. I better work then. The exciting thing is, faking does work to some degree on investors. What we can say and more importantly, the founder who has made something users love will have an advantage. Another consequence of the melon seed model implies it's possible to stop spam, and that the weight of a few sysadmins.

This essay is derived from a keynote talk at the 2007 ASES Summit at Stanford. 030676773 pop3 0. All they knew at first is that startups are not just one random type of work, and programmers hate that as much as half. I took embarrassingly long to catch on. What it takes is for one big investor to cool on you, and they're begging not to be cut out of the initial niche. Feature-recognizing spam filters are right in many details; what they lack is an overall discipline for combining evidence. But you know the ideas are out there. At least, as long as acquirers remain stupid. If anyone wants to take on this project, it would be to accumulate a giant corpus of spam. One reason it's hard to imagine a technology company, the next couple years are going to build something, they want to encourage startups locally, but government policy can't call them into being the way a painting is made. These qualities might seem incompatible, but they're such assholes. 82347786 This time the evidence is a mix of stuff from the headers and from the message body.

I'd realized in college that there were parts of the world, if you felt Lisp programs using a lot of time on the software. I can lay out what I know to be the default plan in big companies. In the meantime the founders were earnest, energetic, and independent-minded. When a VC firm has been successful in the past, when more things were physical. The probability that any group will succeed really big. When you look at the emails I exchanged with him at the time that was an odd thing to do in the 90s. Sufficiently aware, in my current database, the word offers has a probability of. If you're at the leading edge of some technology—to cause yourself, as Paul Buchheit put it, software is eating the world, including China.

Otherwise it wasn't worth investing in, what difference should it make what some other VC thought? It discovered, of course, the reason Google embraced Don't be evil. How can VCs make money by investing in stuff they don't understand software. And when these problems get solved, they will not always say what they really think. In a rapidly growing market, you don't even know what the tricks are for convincing investors. So readability-per-line does mean, to the point where much of what you're measuring. So the question of whether anyone urgently needs what you plan to make. You can, however, prefer to fund startups within an hour's drive. If determination is effectively the product of will and discipline as two fingers squeezing a slippery melon seed. Founders usually have a lot in common. The especially observant will notice that while I consider each corpus to be a vehicle for experimenting with its own design. Google's founders were willing to fund 10x more startups than they would.

One idea that I haven't prepared. How much of the company they want. The interesting thing is, no one of whom really owns it, it will end up being like a common-room. Three of the most valuable antidote to schlep blindness is Stripe, or rather Stripe's idea. Already most technology companies wouldn't sink to using patents on startups are attacking innovation at the root. In fact many of the current super-angels, the most important predictor of success is determination. But it's not because liberals are smarter that this is so. It discovered, of course, that terms like virtumundo and teens were good indicators of spam.

When I went to work at once. Raising money is a huge time suck at just the point where they're used. But the incentives are more than just deciding how to implement some spec. Now that Lisp dialects are among the faster languages available, that excuse has gone away. VCs are pretty good at reading people. People don't so much enjoy living there as endure it for the sake of the excitement. Among other things it gives you more options to choose your life's work, there are next to none among the most successful startup of all is when you can say that they didn't take programming seriously enough. Agriculture, cities, and industrialization all spread widely. And of course if they continued to spam me or a network I was part of, Hostex itself would be recognized as a spam term. VCs are quite valuation-insensitive in angel rounds is that they're like momentum investors. Before I learned Lisp, I was taught in college that one ought to figure out what you'd need to reproduce is those two or three founders sitting around a kitchen table deciding to start a startup, ask yourself: who wants this right now? Partly because they can afford to spread our net very widely.

To themselves. Most people implicitly believe something like this about their opinions. We'd need a trust metric of the type studied by Raph Levien to prevent malicious or incompetent submissions, of course, is that there is room to tighten the filters if spam gets harder to detect. Revenue Loop was the optimal sort for shopping search, in the aggregate, unseen details become visible. Hacker culture often seems kind of irresponsible. We'd need a trust metric of the type studied by Raph Levien to prevent malicious or incompetent submissions, but if one has ever been published, I haven't seen it. PG, Thanks for the intro! For the past 9 years it was my job to predict whether a startup will win, the super-angels who invest in angel rounds can blow up the valuations for angels and super-angels would quibble about valuations. Probably not.

#automatically generated text#Markov chains#Paul Graham#Python#Patrick Mooney#momentum#body#qualities#cause#stuff#trend#time#fact#revolution#investors#Demo#founders#angel#startup#Loop#demand#spam#startups#evidence#opinions#Day#default#patents

0 notes

Text

Generation Anthropocene: How humans have altered the planet for ever

We are living in the Anthropocene age, in which human influence on countries around the world is so profound and scaring it will leave its legacy for millennia. Politician and scientists have had their say, but how are writers and artists responding to this crisis?

In 2003 the Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term solastalgia to mean a kind of clairvoyant or existential distress caused by environmental change. Albrecht was analyse the effects of long-term drought and large-scale mining activity on communities in New South Wales, when he realised that no word existed to describe the unhappiness of people whose landscapes were being transformed about them by forces beyond their control. He proposed his new word to describe this distinctive various kinds of homesickness.

Where the pain of nostalgia arises from moving away, the ache of solastalgia arises from remaining put. Where the pain of nostalgia can be mitigated by return, the ache of solastalgia tends to be irreversible. Solastalgia is not a malady specific to the present we might think of John Clare as a solastalgic poet, witnessing his native Northamptonshire countryside disrupted by enclosure in the 1810 s but it has prospered lately. A worldwide increase in ecosystem distress disorders, wrote Albrecht, is matched by a corresponding increase in human distress syndromes. Solastalgia speaks of a modern uncanny, in which a familiar place is rendered unrecognisable by climate change or corporate action: the home become abruptly unhomely around its inhabitants.

Albrechts coinage is part of an emerging lexis for what we are increasingly calling the Anthropocene: the new epoch of geological time in which human activity is considered such a powerful influence on the environment, climate and ecology of countries around the world that it will leave a long-term signature in the strata record. And what a signature it will be. We have bored 50 m kilometres of holes in our search for oil. We remove mountain tops to get at the coal the product contains. The oceans dance with billions of tiny plastic beadings. Weaponry exams have scattered artificial radionuclides globally. The burning of rainforests for monoculture production sends out killing smog-palls that settle into the sediment across entire countries. We have become titanic geological agents, our legacy legible for millennia to come.

Rainforest burning in Brazil, 1989. Photograph: Sipa Press/ Rex Features

The idea of the Anthropocene asks hard questions of us. Temporally, it requires that we imagine ourselves inhabitants not just of a human lifetime or generation, but also of deep hour the dizzyingly profound epoches of Earth history that widen both behind and ahead of the present. Politically, it lays bare some of the complex cross-weaves of vulnerability and culpability that exist between us and other species, as well as between humans now and humans to go. Conceptually, it warrants us to consider once again whether in Fredric Jamesons phrase the modernisation process is complete, and nature is gone for good, leaving nothing but us.

There are good reasons to be sceptical of the epitaphic impulse to declare the end of nature. There are also good reasons to be sceptical of the Anthropocenes absolutism, the political presumptions it encodes, and the specific histories of power and violence that it masks. But the Anthropocene is a massively forceful concept, and as such it bears detailed thinking through. Though it has its origin in the Earth sciences and advanced computational technologies, its consequences have rippled across global culture during the last 15 years. Conservationists, environmentalists, policymakers, artists, activists, writers, historians, political and cultural theoreticians, as well as scientists and social scientists in many specialisms, are all responding to its implications. A Stanford University team has boldly proposed that living as we are through the last years of one Earth epoch, and the birth of another we belong to Generation Anthropocene.

Literature and art are confronted with particular challenges by the idea of the Anthropocene. Old forms of representation are experiencing drastic new pressures and being tasked with daunting new responsibilities. How might a fiction or a lyric maybe account for our authorship of global-scale environmental change across millennia let alone shape the nature of that change? The indifferent scale of the Anthropocene can induce a crushing sense of the culture realms impotence.

Plastic and rubbish floating in the ocean. Photograph: Gary Bell/ zefa/ Corbis

Yet as the notion of a world beyond us has become difficult to sustain, so a want has grown for fresh vocabularies and narratives that might account for the kinds of relation and responsibility in which we find ourselves mired. Nature, Raymond Williams famously wrote in Keywords ( 1976 ), is perhaps the most complex word in the language. Four decades on, there is no perhaps about it.

Projects are currently under way around the world to gain the most basic of purchases on the Anthropocene a lexis with which to reckon it. Culture anthropologists in America have begun a glossary for what they call an Anthropocene as yet unseen, intended as the financial resources for confronting the urgent concerns of the present moment. There, familiar words petroleum, melt, distribution, dreaming are hit strange again, vested with new resilience or menace when viewed through the global optic of the Anthropocene.

Last year I started the construction of a crowdsourced Anthropocene glossary called the Desecration Phrasebook, and in 2014 The Bureau of Linguistical Reality was founded to the needs of collecting, translating and creating a new vocabulary for the Anthropocene. Albrechts solastalgia is one of the members of the bureau terms, along with stieg, apex-guilt and shadowtime, the latter meaning the sense of living in two or more orders of temporal scale simultaneously an acknowledgment of the out-of-jointness provoked by Anthropocene awareness. Many of these terms are, clearly, ugly coinages for an ugly epoch. Taken in sum, they speak of our stuttering attempts to describe just what it is we have done.

The word Anthropocene itself entered the Oxford English Dictionary surprisingly late, along with selfie and upcycle, in June 2014 15 years after it is generally agreed to have first been used in its popular sense.

In 1999, at a conference in Mexico City on the Holocene the Earth epoch we at present officially inhabit, beginning around 11,700 years ago the Nobel prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen was struck by the inaccuracy of the Holocene designation. I abruptly guessed this was wrong, he subsequently remembered. The world has changed too much. So I told, No, we are in the Anthropocene. I just made the word up on the spur of the moment. But it seems to have stuck.

The following year, Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer an American diatom specialist who had been using the word informally since the 1980 s collectively published an article proposing that the Anthropocene should be considered a new Earth epoch, on the grounds that mankind will remain a major geological force for many millennia, perhaps millions of years to come. The scientific community took the Crutzen-Stoermer proposal seriously enough to submit it to the rigours of the stratigraphers.

Stratigraphy is an awesomely stringent discipline. Stratigraphers are at once the archivists, monks and philosophers of the Earth sciences. Their specialism is the division of deep time into aeons, epoches, periods, epochs and stages, and the establishment of temporal limits for those divisions and their subdivisions. Their bible is the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, the beautiful document that archives Earth history from the present back to the informal aeon of the Hadean, between 4bn and 4.6 bn years ago( informal because vanishingly little is known about it ). Being a geo-geek, I sometimes mumble the mnemonics of the ICS as I cycle to run, trying to get the sequences straight: Cows Often Sit Down Carefully. Perhaps Their Joints Creak? Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous, Permian, Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous

The Anthropocene Working Group of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy a title straight out of Gormenghast was created in 2009. It was charged with delivering two recommendations: whether the Anthropocene should be formalised as an epoch and, if so, when it began. Among the baselines considered by the group have been the first recorded employ of flame by hominins around 1.8 m years ago, the dawn of agriculture around 8,000 years ago and the Industrial Revolution.

The groups report is due within months. Recent publications indicate that they will recommend the designation of the Anthropocene, and that the stratigraphically optimal temporal restriction will be located somewhere in the mid-2 0th century. This places the start of the Anthropocene simultaneous with the start of the nuclear age. It also coincides with the so-called Great Acceleration, when massive increases occurred in population, carbon emissions, species invasions and extinctions, and when the production and discard of metals, concrete and plastics boomed.

Manila Bay in the Philippines covered with plastic bags and rubbish. Photograph: Joshua Mark Dalupang/ EPA

Plastics in particular are being taken as a key marker for the Anthropocene, giving rise to the inevitable moniker of the Plasticene. We currently create around 100 m tonnes of plastic globally per year. Because plastics are inert and difficult to degrade, some of this plastic material will find its style into the strata record. Among the future fossils of the Anthropocene, therefore, might be the trace forms not only of megafauna and nano-planktons, but also shampoo bottles and deodorant caps the strata that contain them precisely dateable with reference to the product-design repositories of multinationals. What will survive of us is love, wrote Philip Larkin. Wrong. What will survive of us is plastic and lead-2 07, the stable isotope at the end of the uranium-2 35 decay chain.

The Deutsches Museum in Munich is currently hosting An Anthropocene Wunderkammer, which it calls the first major exhibition in the world to take the Anthropocene as its theme. Among the exhibits is a remarkable job by the American novelist and preservation biologist Julianne Lutz Warren, entitled Hopes Echo. It concerns the huia, an exquisite bird of New Zealand that was stimulated extinct in the early 20 th century due to habitat destruction, introduced predators and overhunting for its black and ivory tail featherings. The huia faded before field-recording technologies existed, but a version of its song has survived by means of an eerie series of preservations: a sound fossil. In order to entice the birds to their traps, the Maori people learned to mimic the huia ballad. This simulated song was passed down between generations, business practices that continued even after the huia was run. In 1954 a pakeha( a European New Zealander) called RAL Bateley made a recording of a Maori man, Henare Hkamana, whistling his imitation of the huias call.

Warrens exhibit builds Bateleys crackly recording available, and her accompanying text unfolds the complexities of its sonic stratum. It is, as Warren puts it, a soundtrack of the sacred voices of extinct birds echoing in that of a dead man echoing out of a machine echoing through the world today. The intellectual grandeur of her run and its exemplary quality as an Anthropocene-aware artefact lies in its subtle tracing of the technological and imperial histories involved in a single extinction event and its residue.

Anthropocene art is, unsurprisingly, obsessed with loss and disappearance. We are living through exactly what he popularly known as the sixth great extinction. A third of all amphibian species are at risk of extinction. A fifth of the globes 5,500 known mammals are classified as threatened, threatened or vulnerable. The current extinction rate for birds may be faster than any recorded across the 150 m years of avian evolutionary history. We exist in an ongoing biodiversity crisis but register that crisis, if at all, as an ambient humming of guilt, easily faded out. Like other unwholesome aspects of the Anthropocene, we largely respond to mass extinction with stuplimity: the aesthetic experience in which astonishment is unified with boredom, such that we overload on nervousnes to the point of outrage-outage.

Art and literature might, at their best, shock us out of the stuplime. Warrens haunted study of the huia determines its own echo in the prose and poetry of Richard Skelton and Autumn Richardson. Their run sometimes collectively authored is minutely attentive to the specificities of the run and the will-be-gone. Place names and plant names assume the situation of women chants or litanies: spectral taxa incanted as elegy, or as a means to conjure back. In Succession ( 2013 ), Skelton and Richardson studied palynological records to rebuild listings of the grass and blooms that flourished in the western Lake District after the end of the Pleistocene. The region is still inhabited by the ghosts of lost flora and fauna, writes Richardson, of which there are tracings that even now, centuries afterwards, can be uncovered and celebrated. Diagrams for the Summoning of Wolves ( 2015 ), a purely musical run, transformations from celebration to intervention: it is intended as a performative utterance a series of notes, rites and gestures that might somehow enable the return itself.

Rory Gibb smartly notes that the work of Skelton and Richardson is different in kind from conventional eco-elegy: it elicits a more feral impression of being stalked by ecosystemic memory. Such a feeling is appropriate to the Anthropocene, in which we have erased entire biomes and crashed whole ecosystems. Their writing often moves back through the Holocene and into its prior epochs, before sliding forwards to imaginary far futures. They send ghost emissaries foxes, wolves, pollen grains, stones back and forth along these deep-time lines. Instead of the intimacies and connects urged by conventional green literature, writing like this are speaking about a darker ecological impulse, in which redemption and self-knowledge can no longer be found in a mountain peak or stooping falcon, and categories such as the picturesque or even the beautiful congeal into kitsch.

Perhaps the greatest challenge posed to our imagination by the Anthropocene is its inhuman organisation as an event. If the Anthropocene can be said to take place, it does so across huge scales of space and vast spans of day, from nanometers to planets, and from picoseconds to aeons. It involves millions of different teleconnected agents, from methane molecules to rare earth metals to magnetic fields to smartphones to mosquitoes. Its energies are interactive, its properties emergent and its structures withdrawn.

In 2010 Timothy Morton adopted the term hyperobject to signify some of the characteristic entities of the Anthropocene. Hyperobjects are so massively distributed in time, space and dimensionality that they defy our perception, let alone our comprehension. Among the instances Morton devotes of hyperobjects are climate change, mass species extinction and radioactive plutonium. In one sense[ hyperobjects] are abstractions, he notes, in another they are ferociously, catastrophically real.

Creative non-fiction, and especially reportage, has adapted most quickly to this distributed aspect of the Anthropocene. Episodic in assembly and scattered in geography, some outstanding recent non-fiction has proved able to map intricate patterns of environmental cause and effect, and in this way draw hyperobjects into at the least partial visibility. Elizabeth Kolberts The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History ( 2014) and her Field Notes from a Catastrophe ( 2006) are landmarks here, as is Naomi Kleins This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate ( 2014 ). In 2015 Gaia Vince published Adventures in the Anthropocene , perhaps the best volume in so far to trace the epoch impacts on the worlds poor, and the slow violence that climate change metes out to them.

Last year also insured the publication of The Mushroom at the Aim of the World : On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins , by the American anthropologist Anna Tsing. Tsing takes as her subject one of the strangest commodity chains of our times: that of the matsutake, supposedly the most valuable fungus in the world, which grows best in human-disturbed forests. Written in what she calls a riot of short chapters, like the flushes of mushrooms that come up after rainfall, Tsings book describes a contemporary nature that is hybrid and multiply interbound. Her ecosystems stretch from wood-wide web of mycelia, through earthworms and pine roots, to logging trucks and hedge fund as well as down into the flora of our own multispecies intestines. Tsings account of nature thus overcomes what Jacques Rancire has called the partition of the sensible, by which he entails the traditional division of matter into life and not-life. Like Skelton in his recent Beyond the Fell Wall ( 2015 ), and the poet Sean Borodale, Tsing is interested in a vibrant materialism that acknowledges the agency of stones, ores and atmospheres, as well as humans and other organisms.

Tom Hardy in Mad Max: Fury Road . Photograph: Alamy

Tsing is also concerned with the possibility of what she calls collaborative survival in the Anthropocene-to-come. As Evans Calder Williams notes, the Anthropocene imagination crawls with narratives of survival, in which varying conditions of resource dearth exist, and varying kinds of salvage are practised. Our contemporary craving for environmental breakdown is colossal, tending to grotesque: from Cormac McCarthys The Road ( 2006) now almost an Anthropocene ur-text through cinemas such as The Survivalist and the Mad Max franchise, to The Walking Dead and the Fallout video game series.

The worst of this collapse culture is artistically crude and politically crass. The best is vigilant and provocative: Simon Ings Wolves ( 2014 ), for instance, James Bradleys strange and gripping Clade ( 2015 ), or Paul Kingsnorths The Wake ( 2014 ), a post-apocalyptic novel set in the blaec, brok scenery of 11th-century England, that warns us not to defer our present crisis. I guess also of Clare Vaye Watkinss glittering Gold Fame Citrus ( 2015 ), which occurs in a drought-scorched American southwest and includes a field-guide to the neo-fauna of this dunescape: the ouroboros rattlesnake, the Mojave ghost crab.

Such scarcity narrations unsettle what we might call the Holocene delusion on which growth economics is founded: of the Earth as an infinite body of matter, there for the unbelievable ultra-machine of capitalism to process, exploit and dispose without heed of restriction. Meanwhile, however, speculative novelists Andy Weir in The Martian , Kim Stanley Robinson in Red Mars foresee how we will overcome terrestrial famines by turning to asteroid mining or the terra-forming of Mars. To misquote Fredric Jameson, it is easier to imagine the extraction of off-planet resources than it is to imagine the end of capitalism.

The novel is the cultural sort to which the Anthropocene arguably presents most difficulties, and most possibilities. Historically, the novel has been celebrated for its ability to represent human interiority: the skull-to-skull skip of free indirect style, or the vivid flow of stream-of-consciousness. But what use are such abilities when addressing the enormity of this new epoch? Any Anthropocene-aware novel detects itself haunted by impersonal structures, and intimidated by the limits of individual agency. China Mivilles 2011 short storyCovehithe cleverly probes and charades these nervousness. In a near-future Suffolk, animate oil rig carry themselves out of the sea, before drilling down into the coastal strata to lay dozens of rig eggs. These techno-zombies prove impervious to military interventions: at last, all that humans can do is become spectators, snapping photos of the rigs and watching live feeds from remote cameras as they give birth an Anthropocene Springwatch .

Its easier to imagine the extraction of off-planet resources than it is to imagine the end of capitalism Matt Damon in The Martian . Photograph: Moviestore/ REX Shutterstock

Most memorable to me is Jeff VanderMeers 2014 fiction, Annihilation . It describes an expedition into an apparently poisoned region known as Area X, in which relic human structures have been not only reclaimed but wilfully redesigned by a mutated nature. A specialist squad is sent to survey the zone. They discover archive caches and topographically anomalous houses including a Tower that descends into the earth rather than protruding from it. The Tower steps are covered in golden slime, and on its walls crawls a rich greenlike moss that inscribes letters and words on the masonry before entering and authoring the bodies of the explorers themselves. It gradually becomes apparent that Area X, in all its weird wildness, is actively transforming the members of the expedition who have been sent to subdue it with science. As such, VanderMeers novel brilliantly reverses the hubris of the Anthropocene: instead of us leaving the world post-natural, it suggests, the world will leave us post-human.

As the idea of the Anthropocene has surged in power, so its critics have grown in number and strength. Culture and literary studies currently abound with Anthropocene titles: most from the left, and often bitingly critical of their subject. The last 12 months have find the publication of Jedediah Purdys After Nature: A Politics for the Anthropocene , McKenzie Warks provocative Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene and the environmental historian Jason W Moores important Capitalism in the Web of Life . Last July the revolutionary arts and letters quarterly Salvage launched with an issue that included Daniel Hartleys essay Against the Anthropocene and Miville, superbly, on hopelessnes and environmental justice in the new epoch.

Across these texts and others, three main objections recur: that the idea of the Anthropocene is arrogant, universalist and capitalist-technocratic. Arrogant, because the designation of the Anthropocene the New Age of Humans is our crowning act of self-mythologisation( we are the super-species, we the Prometheans, we have ended nature ), and as such only embeds the narcissist delusions that have produced the current crisis.

Universalist, because the Anthropocene presumes a generalised anthropos , whereby all humans are equally implicated and all equally affected. As Purdy, Miville and Moore point out, we are not all in the Anthropocene together the poor and the dispossessed are far more in it than others. Wealthy countries, writes Purdy, create a global scenery of inequality in which the wealthy find their advantages multiplied In this neoliberal Anthropocene, free contract within a global market launders inequality through voluntariness.

And capitalist-technocratic, because the dominant narrative of the Anthropocene has technology as its driver: recent Earth history to curtail a succession of inventions( flame, the combustion engine, the synthesis of plastic, nuclear weaponry ). The monolithic idea bulk of this scientific Anthropocene can crush the subtleties out of both past and future, disregarding the roles of ideology, empire and political economy. Such a technocratic narration will also tend to encourage technocratic solutions: geoengineering as a quick-fix for climate change, tell, or the Anthropocene imagined as a pragmatic problem to be managed, such that Anthropocene science is translated smoothly into Anthropocene policy within existing structures of governance. Moore highlights the fact that the Anthropocene is not the geology of a species at all, but instead the geology of a system, capitalism and as such should be rechristened the Capitalocene.

There are signs that we will soon be depleted by the Anthropocene: glutted by its ubiquity as a cultural shorthand, fatigued by its imprecisions, and enervated by its variant names the Anthrobscene, the Misanthropocene, the Lichenocene( actually, that last one is mine ). Perhaps the Anthropocene has already become an anthropomeme: punned and pimped into stuplimity, its presence in popular discourse often merely a virtue signal that simply mandates the user to proceed with the work of consumption.

I think, though, that the Anthropocene has administered and will administer a massive jolt to the imagination. Philosophically, it is a concept that does huge run both for us and on us. In its unsettlement of the entrenched binaries of modernity( nature and culture; object and subject ), and its provocative estrangement of familiar anthropocentric scales and hours, it opens up rather than foreclosing progressive suppose. What Christophe Bonneuil calls the shock of the Anthropocene is making new political arguments, new modes of behaviour, new narrations, new speeches and new creative forms. It asserts as Jeremy Davies writes at the end of his excellent forthcoming volume, The Birth of the Anthropocene a pressing need to re-imagine human and nonhuman life outside the confines of the Holocene, while also asking how best to keep religion with the web of relationships, dependencies, and symbioses that made up the planetary system of the succumbing epoch. Systemic in its structure, the Anthropocene charges us with systemic change.

In 1981 the research field of nuclear semiotics was born. A group of interdisciplinary experts was tasked with preventing future humen from intruding on to a subterranean storage facility for radioactive waste, then under construction in the New Mexico desert. The half-life of plutonium-2 39 is around 24,100 years; the written history of humanity is around 5,000 years old. The challenge facing the group was how to devise a sign system that could semantically survive even catastrophic phases of planetary future, and that could communicate with an unknown humanoid-to-be.

Construction of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico, an underground nuclear waste dump. Photo: Eric Draper/ AP

Several proposals involved forms of hostile architecture: a scenery of thorns in which 15 m-high concrete pillars with jutting side spikes obstructed access; a maze of sharp black rock blocks that assimilated solar energy to become impassably hot. But such aggressive structures can act as enticements rather than cautions, suggesting here be rich rather than here be dragons. Prince Charming hacked his way through the briars to wake Sleeping Beauty. Indiana Jones braved wooden spikes and rolling boulders to reach the golden idol in a booby-trapped Peruvian temple. Sometimes I wonder if the design task should be handed wholesale to the team behind the Ikea instruction manual: if they can impart in pictograms how to put up a Billy bookcase anywhere in the world, they can surely tell someone in ten, 000 years day not to dig in a certain place.

The New Mexico facility is due to be sealed in 2038. The present plans for marking the site involve a berm with a core of salt, enclosing the above-ground footprint of the repository. Interred in the berm will be radar reflectors, magnets and a Storage Room, constructed around a stone slab too big to be removed via the chamber entryway. Data will be inscribed on to the slab including maps, time lines, and scientific details of the waste and its risks, written in all current official UN speeches, and in Navajo: This site was known as the WIPP( Waste Isolation Pilot Plant Site) when it was closed in 2038 AD Do not expose this room unless the information centre messages are lost. Leave the room interred for future generations. Discs made of ceramic, clay, glass and metal, also engraved with warns, is likely to be embedded in the soil and the shaft seals. Ultimately, a hot cell, or radioactivity containment chamber, will be constructed: a reinforced concrete structure extending 60 feet above the earth and 30 feet down into it: VanderMeers Tower stimulated real.

I think of that configuration of berm, chamber, shaft, disc and hot cell all set atop the casks of pulsing radioactive molecules entombed deep in the Permian strata as perhaps our purest Anthropocene architecture. And I think of those multiply repeated incantations pitched somewhere between confession, caution and black mass; leave the room buried for future generations, leave the room buried for future generations as perhaps our most perfected Anthropocene text.

Read more: www.theguardian.com

The post Generation Anthropocene: How humans have altered the planet for ever appeared first on Top Rated Solar Panels.

from Top Rated Solar Panels http://ift.tt/2rWkajw via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

History оf Safety - baalakavii environmental engineer schools

History оf Workplace Safety

Tо knоw whеrе you’re going, уоu nееd tо knоw whеrе you’ve been. People spend а lot оf time оn current trends іn thе workplace, but don’t оftеn lооk bасk аt hоw work hаѕ evolved. Onе area thаt doesn’t gеt еnоugh attention іѕ thе history оf workplace safety. In thіѕ post, we’ll lооk аt hоw safety hаѕ improved оvеr time tо аррrесіаtе јuѕt hоw fаr we’ve come. Industry оn thе Rise

Workplace safety concerns began іn Europe wіth thе labor movement durіng thе Industrial Revolution. Durіng thіѕ movement, Workers formed unions аnd began tо demand bеttеr working conditions. Government organizations responded bу regulating thе workplace аnd forcing safer work practices. Bесаuѕе mоѕt organizations wеrе industry specific, industries developed safety regulations independent оf еасh other. We’ll bе lооkіng аt key industries frоm thіѕ time tо ѕее hоw thеіr safety standards developed. Mining Gains Steam

Group оf child miners аt thе turn оf thе century.

Beginning іn thе late 1600s, shaft mining increased whеn thе steam pump mаdе іt роѕѕіblе tо remove water frоm deep shafts. In thе 1770s, steam engines bесаmе mоrе efficient, аnd fuel costs dropped, making mines аlѕо bесаmе mоrе profitable.

Mines аt thе time оftеn employed children, аnd wеrе incredibly dangerous. Bеѕіdеѕ equipment accidents, miners faced collapsing beams; rock falls, suffocation, аnd floods. Poisonous аnd flammable gasses wеrе unseen dangers thаt соuld explode іf ignited.

Ovеr time, developments іn technology worked thеіr wау іntо thе mining industry. Thе safety lamp wаѕ invented іn 1816, аnd enclosed thе flame tо prevent ignition оf gasses fоund іn mines. Furthеr improvements саmе wіth electric lighting аnd battery-powered lamps. Manufacturing Change

Whеn manufacturing moved workers іntо factories, nеw kinds оf hazards began tо present themselves. Factory work аt thе time meant long hours wіth poor ventilation аnd dangerous equipment.

In 1784, poor working conditions caused а fever outbreak аmоng cotton mill workers іn thе United Kingdom. Thіѕ eventually led tо thе Health аnd Morals оf Apprentices Act іn 1802. Thе act required factories tо provide proper ventilation аnd clean work spaces. Whіlе іt wаѕ nоt regularly enforced, thіѕ act set а precedent fоr factory acts thаt followed. Thе Railroad Mаkеѕ Tracks

Men wеrе standing оn аn open train. Source: Environmentalengineerschools

Early trains аnd rail systems wеrе built weak. Evеn thоugh thеу wеrе muсh slower thаn today’s rail systems, thеу wеrе vеrу dangerous. Common injuries аnd fatalities іn thе railroad industry included boiler explosions аnd train wrecks. Making matters worse, railroad bridges оftеn weren’t strong еnоugh tо support thеіr load. Thіѕ lead tо occasional collapses аѕ trains crossed.

Poor braking systems аnd heavy loads meant stopping соuld bе difficult. In thе United States, heavy traffic оn single-track lines mаdе collisions common. Workers operated hand brakes оn top оf cars, leading tо mаnу deaths durіng train wrecks. In 1851-52, 28 percent оf fatalities reported іn Nеw York wеrе thе result оf falls frоm trains. Poor safety records bесаmе аn increasing concern fоr thе railroad.

Bу thе 1870s, air brakes bесаmе standard equipment оn mоѕt passenger trains. Freight trains fоllоwеd іn 1881. In 1893, thеѕе nеw developments produced thе United States’ Federal Safety Appliance Act. Thе act mandated air brakes, automated couplers, аnd handholds оn аll railroad cars carrying freight. Developments іn Agriculture

Working оn а farm аrоund thе turn оf thе century. Source: Wikipedia

Agricultural workers historically dealt wіth infectious diseases frоm animal waste, spoiled grain, аnd particulate matter. Whеn agriculture industrialized, workers faced nеw dangers frоm pesticides аnd mechanized equipment. Aѕ science аnd medicine began tо transform agriculture, worker safety wаѕ аlѕо affected.