#tsuboniwa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Two Kings in Tears of the Kingdom

Tears of the Kingdom unearths the roots of Calamity Ganon in an ancient conflict between Rauru, the first king of Hyrule, and Ganondorf, a rival king who attempted to usurp him. In many ways, Rauru is characterized as a good king. He is noble, kind, and self-sacrificing, and he acts for the long-term benefit of the various groups of people living in Hyrule. In contrast to Rauru, the antagonist Ganondorf is an evil king who started a war because of his pride, ego, and greed.

Rauru and Ganondorf represent different styles of authority, both of which are grounded in Japanese fantasies of cultural identity. I’d argue that, in the end, neither king is fit to rule present-day Hyrule, which is why it’s appropriate that the game ends without any call to rebuild Hyrule Castle or the centralized government it symbolizes.

Rauru represents a golden age in Japanese culture when many arts now seen as “traditional” originated. This golden age is closely tied to Nintendo’s home city of Kyoto, which is associated with the culture of the imperial court before it moved to Tokyo in 1868. Because Tears of the Kingdom is a fantasy, the visual metaphors of Rauru’s character design are mixed, but his connection to a bygone golden age is tied to two symbols: the magatama jewels referred to as “secret stones,” and the kare-sansui dry landscape gardens of the Shrines of Light and the Temple of Time.

The “secret stones” that Rauru gives to the six sages have the distinctive comma shape of a magatama jewel, one of the three sacred symbols of Shinto. These three symbols are as follows: a mirror represents clarity of heart, a sword represents the power to protect the weak, and a jewel represents the materiality of divine blessings. These three objects also serve as the regalia of the Japanese emperor, whose role was historically to perform ritual prayers and thereby serve as a symbolic bridge between the world of humans and the world of gods.

There is nothing sacrosanct about magatama jewels; at various street fairs and tourist areas throughout Japan, you can buy inexpensive polished quartz and jade magatama to attach to phone charms or friendship bracelets. As a result of its relative ubiquity, this particular shape of gem has both a historical and a pop culture association with being a magical stone bestowed by the gods on special and worthy individuals such as, most famously, the first Japanese emperor.

Along with his magatama “secret stones,” Rauru is associated with kare-sansui dry landscape gardens of the old imperial capital. Note, for instance, the front courtyard of the Temple of Time that Link visits at the beginning of the game:

The visual motif of raked white gravel punctuated by standing rocks also appears in various permutations within the Shrines of Light established by Rauru and Sonia. To give an example, this is what the player will see if they circle back behind the entrance of the “Rauru’s Blessing” shrines:

This style of dry landscape garden is frequently referred to as a “Zen garden” because of its association with large Buddhist temples in and around Kyoto. The most famous example of this style can be found at Ryōanji, in northwest Kyoto:

The philosophy of these gardens meshes well with the philosophy behind the Zelda series, which Shigeru Miyamoto has described as his attempt to create a tsuboniwa miniature garden for the player to explore. In the same way, dry landscape gardens represent a larger landscape portrayed on a much smaller scale. The rocks in the gravel are meant to represent islands on the ocean, or perhaps mountaintops rising above the clouds. Another common interpretation of these gardens – and one especially pertinent to Tears of the Kingdom – is that the rocks are the dorsal spines of a dragon swimming through the sky.

Although dry landscape gardens have strong ties to Buddhist thought, they were primarily created by wealthy lords residing in Kyoto during the fifteenth century. This was a politically unstable era, and these lords needed to make a show of their wealth and cultural legitimacy. Unlike in China, where Chan Buddhism was largely anti-establishment, Zen Buddhism was the domain of the wealthy educated elite in Japan. Many of the rocks used in Zen-style gardens were imported from China and Korea at great expense, and lords competed to secure the services of celebrity landscape designers. Even today, the late medieval culture represented by dry landscape gardens is associated with the prestige of Japan’s former imperial capital of Kyoto.

Rauru is therefore associated with nobility and a certain air of sophistication. In the original Japanese script, he is unflaggingly polite and addresses everyone – Zelda, Ganondorf, and Link alike – with the sort of “clean” language associated with people of high social standing. To put it simply, Rauru is a perfect gentleman. He is the personification of the aristocratic virtues of the “traditional Japan” of the late fifteenth century, during which the wealthy filled the capital city with gardens while countless wars ravaged the countryside.

In contrast, Ganondorf is a personification of the warrior culture of eastern Japan, especially as it was exemplified by the warlords who competed for territory outside the capital before the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

Oda Nobunaga was the most notorious of these warlords. He was infamous for being aggressive but effective, and his military prowess and ruthless tactics have been memorialized in a wealth of stories whose lineage stretches to the video games of the present day. I believe that Nobunaga (or, at least, a commonly fictionalized version of him) served as a model for Ganondorf, who seeks to take advantage of the instability of the newly established kingdom of Hyrule in order to expand his own territory.

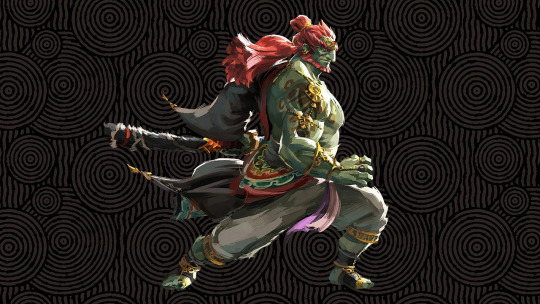

Like Rauru, Ganondorf’s character design contains mixed visual metaphors, but I think it’s fair to say that his topknot and costume are meant to evoke a samurai who has thrown off the kimono sleeve covering his sword arm as an indication of his readiness for battle. This is a style still worn by practitioners of Japanese fencing and archery, which are common extracurricular activities in many high schools. Appropriately, Ganondorf fights with a tachi katana, a naginata spear, and the body-length longbow used in kyūdō archery – all weapons associated with the martial arts of Japan’s medieval military elite.

As if to cement his connection to Nobunaga, Ganondorf speaks in period-drama “samurai Japanese” that demonstrates neither the elegance nor the poetry of his incarnations in previous games. He seems to lack both regret and awareness of the consequences of his actions, and he is concerned primarily with hierarchy, conquest, and the thrill of battle.

As was arguably the case for Nobunaga himself, there is no endgame for Ganondorf, only scorched earth. Ganondorf has absolute faith in his own power, and he views other people only as subordinates or enemies. According to his value system, there is no merit in compromise; he simply takes it for granted that he will win.

It makes sense that the aggressively bloodthirsty Ganondorf is a villain, but it’s important to understand that Rauru is not a hero. With all his magic and culture and imperial splendor, Rauru failed to understand that the system of power he created could easily be turned against him. A nation politically defined by a central authority whose rule is justified through military conquest and the cultural chauvinism of “ancient tradition” is not sustainable, and the legacy of such a kingdom can only be tears.

This is why Hyrule Castle remains in ruins at the end of Tears of the Kingdom, and this is why the game’s central hub is a research station populated with people from all over the world. This is why Zelda doesn’t attempt to re-establish Hyrule as a kingdom, and this is why it’s so important to her to understand the reality behind the myth of the nation’s history. This is also why the grand mythology of Hyrule’s origin is far less important to the player’s experience of the game than individual acts of community building. The highlights of Tears of the Kingdom are Link’s work in facilitating a local election in Hateno, helping Lurelin recover from a disaster, and volunteering in towns facing environmental issues such as water pollution and climate change.

Both Rauru and Ganondorf are compelling in their own ways, but it’s thematically satisfying that both characters are gone at the end of the game. When Zelda meets with the regional leaders of Hyrule during the closing cutscene, they promise each other that they will work together to ensure a lasting peace that neither of the two kings made possible. The legacy of the past still affects Hyrule, but Tears of the Kingdom suggests that it’s the duty of the younger generation to understand where this legacy came from in order to avoid the mistakes of their ancestors and move forward in a more hopeful direction.

270 notes

·

View notes

Text

Figuring out Komatsudaya's layout

I started putting together pics of and notes on Komatsudaya for my own reference (it's hard to write a story set somewhere whose layout you don't know), but decided to expand on it and make something that other people might find useful. Let's explore what the anime and manga have shown of Komatsudaya!

EXTERIOR

The exterior's gone through a few different incarnations in the anime, with the noren color and basic layout being the only consistent things. This is the first design we see, from episode 13-05.

After episode 13-05, the rocks on the roof were ditched, a curtain that runs across the building was added, and the display window's curtain was changed from purple to blue. Episode 16-97 (left) had a new, completely brown sign (or the animators forgot to color it in), which was changed back to the old colorful sign in episode 20-37 (right). Episode 16-97 almost makes it look like there's a second story, but all the other episodes make it look like a one-story building.

Episode 28-48 shows the most recent version of Komatsudaya's exterior, where the display window has lost its curtain. Instead, it's gained a wooden hatch (shutter?) that opens up toward the street, a feature that was previously either missing or which opened up toward the room and was thus hidden by the curtain.

The original manga version has the same general exterior, except the curtain in the display opening is patterned (volume 35, page 42).

Besides the exterior itself, there's also the question of the store's immediate surroundings and where it's located in relation to other buildings. Both the anime and manga show stores directly across from Komatsudaya.

However, anime seasons differ on where in the city Komatsudaya is located. Episode 13-05 (left) shows the store relatively near what looks to be the edge of town, with buildings on both sides of it. Episode 16-97 also shows Komatsudaya surrounded by buildings. However, a shot from episode 20-37 (right), framed in the same direction as episode 13-05's shot, shows Komatsudaya on a corner right next to a crossroad in what's presumably the middle of the city.

The manga is equally inconsistent about what Komatsudaya's surroundings are. Volume 35 (page 44, left) shows a flat road in between Komatsudaya and the buildings across from it, but volume 65 (page 221, right) has a waterway flowing through the middle of the street. I don't think it's a matter of differing perspectives, as everyone seems to be standing in about the same place in both panels. Maybe the city dug out a ditch between volumes 35 and 65?

INTERIOR

Now to get into the guts of Komatsudaya. The first question is: how many rooms are in the building? From what I can tell, we've been shown four distinct rooms throughout the series.

The first is the shop itself. All incarnations of it have a raised "display floor" of sorts when you walk in, though what it looks like differs from season to season. In addition, while the anime always has the floor displaying products to be sold, in the manga you can see fans being made on the display floor. Episode 28-48 (bottom) shows what looks like the beginning of a hallway to the side, which episode 16-97 (top) lacks. Incidentally, two of the fans on the wall in 28-48 are the fans that were being displayed outside Komatsudaya in episode 13-05.

Speaking of what episode 28-48 shows, it also shows what looks to be a window or open door in the back of the shop. Since we can see the sky, the opening potentially leads out to a small, enclosed garden (tsuboniwa), something which was found in many town houses of this era.

The manga also shows the display floor, but here it seems to run vertically across the room instead of horizontally. However, we never get to see inside the room itself, so it's difficult to say what its layout is (left, volume 35, page 42; right, volume 65, page 222).

Next is the tea room we see during episode 13-05 (left) and volume 35 (page 46, right). This room is pretty consistent across the anime and manga (it's not in the above screenshot, but the anime's tea room also has wood paneling on one wall). I do wish the anime kept the cute little flower trimming on the tatami. The anime adds a small alcove and display shelf to the room; the fan on display here can also be seen on the wall in episode 28-48.

Episode 16-02 (left) shows what looks like a back room where the artisans craft the fans, and we see a close-up of the shelves in the same room in episode 16-97 (right).

Then, in episode 31-30, there's a shot of what seems to be an entirely new room. At first I thought this could potentially be the shop's display floor, but the wooden planks on the floor in this mystery room look to be going in the opposite direction of those on the display floor.

Taking all of that into account, as well as what town houses looked like in this period, maybe Komatsudaya's layout is something like this?

There could be more rooms than what we've been shown, and there's definitely plenty of furniture and items I didn't add to the layout. However, this is a fair estimate of how I see the store in my head based off of what's in the anime and manga.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

万両[Manryō] Ardisia crenata

母と見る 庭の凍土 さびしきに こぼれて紅し 万両の実は

[Haha to miru niwa no itetsuchi sabishiki ni koborete akashi manryō no mi wa] The red berries of Manryō spill over and accent the lonely frozen garden soil where I gaze with my mother By 音馬 実[Otouma Minoru](Poet)

尼寺の ひるげによばれ 箸とれば 万両の実が 縁さきに紅し

[Amadera no hiruge ni yobare hashi toreba manryō no mi ga ensaki ni akashi] Invited to midday meal at a nunnery, I picked up my chopsticks (as I began to eat), I noticed the red berries of Manryō at the edge of veranda By 川田 順[Kawada Jun] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jun_Kawada

漱ぐ 寺の壺庭 苔ふかみ 万両の実の 赤さもあかき

[Kuchisosogu tera no tsuboniwa koke fukami manryō no mi no asasa mo akashi] The Tsuboniwa (inner garden) of the temple where I rince my mouth out (to purify with water) is covered with deep green moss and the red berries of Manryō growing there appear to be redder By 木下 利玄[Kinoshita Rigen]

The kanji 漱 is the same as that of Novelist 夏目 漱石[Natsume Sōseki]. His pen name, 漱石, translates directly to "rinse his mouth out with stone", meaning "perverse person". This comes from an old Chinese historical event. 漱ぐ is also read as kuchisusugu. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sun_Chu_(Western_Jin)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

📸妙心寺 大雄院庭園 / Myoshinji Daioin Temple Garden, Kyoto ② 続き。そして客殿の襖絵🖼(*撮影禁止)を描いたのが、江戸時代末期~明治初期の絵師・柴田是真(しばたぜしん)🎨 全72面にも及ぶ大雄院の襖絵は若かりし是真の初期の大作であり、また現存する作品の多くが海外に流出しているため国内の作品としても貴重(その他、トーハクや静嘉堂文庫美術館、佐野美術館など割かし有名な美術館・博物館が作品を所蔵)。 . また柴田是真が明治宮殿の千種の間に描いた“花の丸大天井”を現代の宮絵師・安川如風が襖絵として蘇らせる『襖絵プロジェクト』も見どころです!このGWに京都旅行へ来られる方はぜひチェックしてみて。 . 京都・妙心寺 大雄院庭園の詳細はこちら☟ https://oniwa.garden/myoshinji-daioin-temple-%e5%a4%a7%e9%9b%84%e9%99%a2%e5%ba%ad%e5%9c%92/ ーーーーーーーー #japanesegarden #japanesegardens #kyotogarden #zengarden #kyotojapan #beautifulkyoto #beautifuljapan #japanesearchitecture #japanarchitecture #japanarchitect #jardinjaponais #jardinjapones #japanischergarten #jardimjapones #kyototemple #坪庭 #tsuboniwa #bonsai #建築デザイン #庭園 #日本庭園 #京都庭園 #非公開庭園 #特別拝観 #京都特別拝観 #枯山水 #枯山水庭園 #karesansui #おにわさん (妙心寺 大雄院) https://www.instagram.com/p/CcsWMa8vQC3/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#japanesegarden#japanesegardens#kyotogarden#zengarden#kyotojapan#beautifulkyoto#beautifuljapan#japanesearchitecture#japanarchitecture#japanarchitect#jardinjaponais#jardinjapones#japanischergarten#jardimjapones#kyototemple#坪庭#tsuboniwa#bonsai#建築デザイン#庭園#日本庭園#京都庭園#非公開庭園#特別拝観#京都特別拝観#枯山水#枯山水庭園#karesansui#おにわさん

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

View of the courtyard garden from the 2nd floor bedroom of Korekiyo Takahashi--the same bedroom where Takashi was assassinated in 1936 by ultra-nationalist army officers using a pistol and sword. ISO 1600 at ƒ/8 for 1/640 sec. #Japanesegarden #traditionalgarden #courtyardGarden #tsuboniwa #KorekiyoTakahashiHouse #koganeipark #坪庭 #高橋是清邸 #江戸東京たてもの園 #小金井公園

#Japanese garden#traditional garden#traditional Japanese garden#courtyard garden#tsuboniwa#Korekiyo Takahashi House#Koganei Park#坪庭#高橋是清邸#江戸東京たてもの園#小金井公園

34 notes

·

View notes

Link

Besoin d’un paysagiste pour la conception d’un petit jardin japonais de type tsuboniwa ?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nhà ống 2 tầng ở Úc ứng dụng thiết kế kiểu nhà phố Nhật Bản để tối ưu không gian và tiết kiệm chi phí

Nhà ống 2 tầng ở Úc ứng dụng thiết kế kiểu nhà phố Nhật Bản để tối ưu không gian và tiết kiệm chi phí

Leichhardt Machiya được thiết kế dựa trên cảm hứng từ kiểu nhà Machiya của Nhật Bản để phù hợp với hình dáng mảnh đất và đảm bảo công năng tích hợp giữa nhà ở và kinh doanh. (more…)

View On WordPress

#132m2#2 tầng#2019#Carr Street vẫn sở hữu không gian ngoài trời đáng ngưỡng mộ#Gia đình 5 người cơi nới mảnh đất bỏ không ở sân vườn để tăng diện tích sinh hoạt và vui chơi cho trẻ nhỏ#Justin Alexander Simon Whitbread#kinh doanh#Leichhardt Machiya#Machiya#mát mẻ nhờ thiết kế vườn cây đan xen không gian sống#nhà ở#nhà ống#nhà phố#Nhà phố 2 tầng thoáng đãng#Nhật Bản#Studio Haptic#tiết kiệm chi phí#tối ưu không gian#Tsuboniwa#Xây dựng trên khu đất nhỏ ở nội đô

0 notes

Text

Minish Tsuboniwa

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

in town terrasse.

0 notes

Photo

Kahitsukan - Kyoto Museum of Contemporary Art

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

📸VISVIM GENERAL STORE / ビズビム・ジェネラル・ストア ② 東京・中目黒の『VISVIM GENERAL STORE』の庭園が素敵…! 2022年7月、新たに東京に現れた“市中の山居”。人気ファッション・ブランド《visvim》のデザイナー・中村ヒロキさんが自らデザインを手掛けた新店舗には、現代日本の庭師の巨匠 #安諸定男 さんが約10年ぶりに作庭した小川のせせらぐ庭園が…。 ...... 続き。VISVIM GALLERYの室内もその庭空間を感じられるよう意識して窓が設置されていて、中でも水琴窟の姿を切り取るよう見せている奥の窓は京都の『大徳寺 孤篷庵』の“忘筌”をオマージュしたもの。 . 竹垣に竹細工、敷石に今後育ってゆく植栽…まさに“庭師”の技が凝縮された空間。ぜひアパレル好きの方が“日本の庭の美”に興味を抱くきっかけにもなって欲しい庭園。 . 東京・VISVIM GENERAL STOREの紹介は☟ https://oniwa.garden/visvim-general-store-tokyo/ ーーーーーーーー #visvim #japanesegarden #japanesegardens #kyotogarden #tokyogarden #zengarden #beautifultokyo #beautifuljapan #japanesearchitecture #japanarchitecture #japanarchitect #japandesign #japanart #jardinjaponais #jardinjapones #japanischergarten #jardimjapones #tsuboniwa #landscapedesign #nakameguro #ランドスケープ #建築デザイン #庭園 #日本庭園 #東京庭園 #造園 #中目黒 #坪庭 #おにわさん (WMV Visvim TOKYO) https://www.instagram.com/p/CivF16RvOFg/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#安諸定男#visvim#japanesegarden#japanesegardens#kyotogarden#tokyogarden#zengarden#beautifultokyo#beautifuljapan#japanesearchitecture#japanarchitecture#japanarchitect#japandesign#japanart#jardinjaponais#jardinjapones#japanischergarten#jardimjapones#tsuboniwa#landscapedesign#nakameguro#ランドスケープ#建築デザイン#庭園#日本庭園#東京庭園#造園#中目黒#坪庭#おにわさん

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This classical “machiai” is a sheltered bench waiting area to relax until you are called into the garden tea house for the tea ceremony. The machiai features a woven bamboo roof design and the classical use of plaster comprised of natural earth sand (sunakabe = literally “sand wall”). ISO 100 at ƒ/4.5 for 1/20 sec. #machiai #Japanesegarden #traditionalgarden #courtyardGarden #tsuboniwa #KorekiyoTakahashiHouse #koganeipark #坪庭 #高橋是清邸 #江戸東京たてもの園 #小金井公園

#machiai#Japanese garden#traditional garden#courtyard garden#tsuboniwa#Korekiyo Takahashi House#Koganei Park#坪庭#高橋是清邸#江戸東京たてもの園#小金井公園

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Morozoff JAPAN / Singapore - 2 Plaza Singapura Opened Nov. 2017 Interior Design : Roito by Ryohei Kanda Strategic Design : STRATE VMD : STRATE Sign Logo Design : studio KULTA Graphic Design : Reimi Muranaga

#morozoff #morozoffjapan #sinpapore #interiordesign #shopdesign #designedbyRoito #Roito #ryoheikanda #inspiration #yukimishoji #shoji #tsuboniwa (Plaza Singapura)

#morozoff#sinpapore#tsuboniwa#shoji#ryoheikanda#interiordesign#designedbyroito#morozoffjapan#yukimishoji#inspiration#shopdesign#roito

1 note

·

View note