#toei majokko series

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I sought out this CD and scanned the cover art because, to my knowledge, it features one of the most complete set of protagonists from the Toei Magical Girl Series (東映魔女っ子シリーズ).

The album's title is Great Magical Girl Strategy Special Song Collection (魔女っ子大作戦 スペシャル·ソング·コレクション). As with so many of these crossover images from the Toei series, it's associated with the Great Magical Girl Strategy (魔女っ子 大作戦) video game from 1999 (平成11).

The only possible missing piece here would be Magical Girl Tickle (魔女っ子チックル) . I would expect her to be present more often when Toei promotes the series if she were meant to be included. But, she is included as part of a different CD -- The Dream of a Singing Girl ~Toei Animation Magical Girl Anime Complete Works~ (歌いつがれる少女の夢 ~東映動画魔法少女アニメ全集~).

#Toei Magical Girl Series#toei majokko series#majokko#魔女っ子大作戦#CD#crossover#lun lun#昭和#showa era#魔法少女#magical girl#魔女っ子#retro shoujo#retro shojo#heisei#heisei era#video game#video games#hana no ko lunlun#sally the witch#akko chan#himitsu no akko chan#secretive akko chan#akko chan's got a secret#magical girl lalabel#cutie honey#chappy

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

First Episode vs. Final Episode

The last episode of Majokko Megu-chan reunites most of the main staff from the first episode, which was an incredible feat back in the day. In fact, I think it was only the third Toei series to have the same animation director (usually the same person who handled the character designs) for the first and last episodes. Above you can see how Shingo Araki's style evolved over Megu-chan's 72 episode run.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation Night 155: Kunihiko Ikuhara

...or Ikuni to his fans. The Utena guy.

Since the very beginning of this series, Ikuhara’s been someone I’ve been desperate to cover. He’s exactly the kind of weirdo we like around here. And you know how much the Tumblr girlies love Utena.

But only now, at Animation Night 155, is Ikuni getting his due. Why so long? Well, let’s put it like this. Ikuni’s very much a TV guy. Revolutionary Girl Utena is 39 episodes and a movie. Mawaru Penguindrum: 26 episodes. Yurikuma Arashi is 13, as is Sarazanmai.

And if we’ve managed to cram in 13-episode series into this format, it’s always been with difficulty - take Heike Monogatari [AN91], Alexander Senki [AN125] or Houseki no Kuni [AN97]. It generally takes multiple nights. So I thought, that’s fine, we’ll do Adolescence of Utena, the movie, and, um... hmm.

Luckily for us they just made a new Penguindrum compilation movie! Problem solved let’s go!

And with such a long wait behind us, let’s try and do the guy some justice.

So. Who is this guy with the rabbit? (Picture from his website. Though this is a plain outfit by Ikuhara standards!)

If you were trying to summarise Ikuni’s works... you could probably say something like this: surreal, densely symbolic stories about the difficulties of real human connection. Sort of like the anime version of Lynch. But if that sounds too cerebral, let’s not forget that an episode of Utena involves a character gradually turning into a cow for no particular reason. He’s just as much a goofball who loves to tell lies.

Ikuni came into the business back in the mid eighties, at Toei. [c.f. AN149 for a brief history of Toei!]

So. In the late 70s, Toei had established a powerful niche to themselves in long-running, wildly popular series such as Galaxy Express 999, but most of their work was much less high-profile. Take a glance, see how many of these you recognise - I would guess not many! Hot out of art school, Ikuhara became an assistant director under the wing of Junichi Satō, later well known for shōjo anime such as the avant-garde Princess Tutu (2002-3), or Ojamajo Doremi (1999-2000).

But of course, the most renowned Satō project is Bishōjo Senshi Sailor Moon (1991-7, Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon). Satō directed the first half, and then Ikuhara took the reins for the rest. For Satō it was his debut as a director, I’ll talk more about his tenure on Sailor Moon in just a minute, but first, let’s get a little context about... magical girls!

(quick! tell me which sailor this is! you have five seconds)

Magical Girls! 魔法少女 mahō shōjo. An ordinary high school student makes contact with a powerful magical being, who may also be a cute mascot character, and agrees to help. Now she can transform: manifest a stylish outfit, gain suitably themed powers, and fight monsters of the week... but she’s got to maintain a double life as a regular student. The henshin (transformation) sequence itself will usually be an extremely elaborate sequence that is played regularly (a ‘bank’ shot).

By now it’s one of the absolutely central anime archetypes, one people are likely to recognise even if they’ve never watched a magical girl show. It’s been parodied, it’s been genderflipped, it’s spun off a dark otaku-oriented variant.

But it wasn’t always so! Everything must begin somewhere. Very quickly reeling this off then... Osamu Tezuka’s 1953 manga Princess Knight is seen as the earliest proto-magical-girl work; Himitsu no Akko-chan (1962-5) as the earliest true magical girl manga with the elements of the genre, and 1966′s Sally the Witch as the big populariser. In the 70s, Toei started producing them in a big way, known collectively as 魔女っ子 majokko series (‘little witch’).

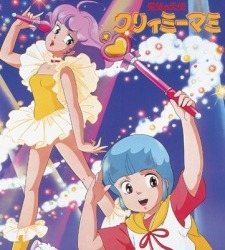

The actual phrase 魔法少女 mahō shōjo was introduced in 1980 with 魔法少女ララベル Mahō Shōjo Lalabel. With the economic bubble in full swing, other studios started to join the party - notably AshiPro with Minky Momo, and Pierrot, the studio behind epoch-defining megahit Urusei Yatsura, who entered the arena with Creamy Mami, the Magic Angel (1983-4). Why is she creamy? I don’t know, but that’s her stage name as an idol; the manga was designed to promote an actual idol singer Takako Ōta. This business model proved wildly successful, and even today anime production committees usually include record companies who use the show as a vehicle to promote a song or group. Toei no longer had exclusive hold on the matter of girls, magical.

Visually here we’re seeing 80s-style bishōjo, the same as over the fence in sci-fi series such as Macross. Mostly the stories are comedies, following in the footsteps of Urusei Yatsura.

What was missing from the formula at this point? Surprisingly, the henshin sequences! It’s not that magical girls didn’t transform, but they would be more likely to transform into something like an aged-up version of themselves, and the act of transformation wouldn’t be given the same importance. This final ingredient was to be found over in tokusatsu land - Kamen Rider and Super Sentai.

So, that’s where Sailor Moon came in at the beginning of the 90s - first a wildly successful manga by Naoko Takeuchi, and in very short order a TV series at Toei. Takeuchi came up with the idea of fusing the magical girls with sentai: instead of a motorbike-like Rider suit, the girls would get sailor fuku. And that means every magical girl transformation is in a sense a homage to this one.

youtube

Sailor Moon tells the story of a girl called Usagi. She’s a clumsy and forgetful audience-identification character - perhaps even to point of being a Huineng-type character? - but she’s informed by a talking cat that she’s the guardian of Earth, soon to be joined by a number of other girls from her area who are, collectively, the Sailor Guardians (セーラー戦��� sērā senshi). To fight, she activates a magical brooch and, that ^ happens.

Why? Well, the Dark Kingdom is invading! They want to free the villainous Queen Metaria. In past lives the Sailor Guardians fought those guys, and now they need to get back on the job. The forces of the Dark Kingdom (and numerous subsequent enemy factions) arrive in the form of a series of themed villains, much like the villains in a tokusatsu show. Outside of fighting those guys, it’s gentle comedy with a large cast, not so far from the works of Rumiko Takahashi. In fact it’s apparently a fair bit more comedic in tone than the manga, and a chunk of that can be credited to Ikuhara’s influence.

It’s hard to try and summarise the 90s for anime, it wasn’t just one thing. Even as the economic bubble popped, the movies got increasingly ambitious, reaching for more complex emotions and darker themes with incredibly complex animation to match. And to a certain extent, that was also true on TV, by which I mean “Evangelion happened”. But it was also an age of a return to more limited animation. If you wanted to make a TV anime, you had to be smart about using all the tools you could to cut corners. You could keep a bank of reused shots, or for a joke, transform a character into a much simpler caricatured design with more limited animation. At the same time, photography was getting more advanced, and animation techniques were getting more sophisticated.

Even so, a lot of the credit for the art of working effectively in limited animation goes way back to Osamu Dezaki, who back in the 60s and 70s established many of the iconic ‘anime’ techniques. I’ve written about him before back on Animation Night 95, but as much as that covers the history, it doesn’t say a lot about Dezaki’s style. So let me pull in this video, which will helpfully illustrate the important examples...

youtube

The relevant period is when Dezaki directed on Aim for the Ace! (エースをねらえ! Ēsu o Nerae!) - where, in contrast to his earlier work which was comparatively cinematic, he started to push in a more theatrical, abstracted direction, prioritising conveying emotion over realism. Still frames (with the famous ‘postcard memory’ effect), simplified background details framed to draw attention to the important stuff, repeating an important shot multiple times - oh, that’s just Utena, huh? And while Dezaki influenced just about everyone, but for Ikuhara, he’s a massive touchpoint.

Designs were also changing - in contrast to the rounded bishōjo of the 80s came more angular and blocky designs. Take Slayers for example:

Hold onto that thought because we’re going to talk about Utena in a minute. Sailor Moon didn’t go quite that far, but Kazuko Tadano’s designs were very effective in conveying a lot of appeal in quite simple shapes. Usagi in particular has an instantly recognisable hairstyle. But it’s also a style very amenable to simplification.

TV anime in this period ran long. Nowadays, the norm is one cours (‘cour’ if you’re not feeling pedantic) of 12-13 episodes, sometimes not even that. Back then you could easily see counts in the 50s or even hundreds. Such is true of Sailor Moon: crazy popular in both Japan and, in its heavily localised dub, America, and with a premise flexible enough to run for years. In the end it racked up some 200 episodes and several movies.

The Ikuhara period starts with the Sailor Moon R movie in 1993, then the series proper starting mid Sailor Moon R and then Sailor Moon S in 1994. Not sure which episode he took over, but S begins at 90. This is a post about Ikuhara (no, really!) so we should ask, how did Sailor Moon change once he took the reins? Let’s have a look at some of his favourite themes, as they appear in the Sailor Moon R movie, based on his own notes...

Lesbians - Not so much in the R movie, but once S gets going... big controversy! Sailors Uranus and Neptune were a couple whose dynamic was one of the most popular in the show, but this would be heavily censored in nearly every localisation, notably the American one which made them cousins.

Flower imagery - Ikuhara decided to set his first project as director in a botanical garden, naturally.

Lost connections, the distance between people - to quote the linked blog...

Ikuhara compares the reunion between Fiore and Mamoru with that of being stuck on a train in-between stations when suddenly you notice you’re standing next to an old friend you haven’t seen in years.

At first you’re both excited to see each other again and kill the time by catching up on each other’s lives. But eventually you run out of things to say, and the conversation just kind of dies off, leaving you both standing there in awkward silence.

Creative editing, use of music - 18 second long scene of Tuxedo Mask getting stabbed? Musically timed fight? Mm.

Darker themes - let’s watch the girls incinerate a field of flower monsters! At one point Usagi would nearly die! Ikuhara tried to keep it ‘fun’ and lighthearted, but just couldn’t do it, he says. Nothing on the level of where his later work would go, but definitely harsher than your average episode.

Vaguely hinting that some element is key to understanding everything, and then refusing to elaborate further - oh yes.

Which isn’t to say that Ikuhara’s Sailor Moon instantly became Utena. Rather, the seeds of his interests as a director, the sort of emotional arcs he’d like to portray, were there. I regret that I can’t really comment in much detail on what Ikuhara did in his actual run on the TV series - I’m sure I have some big Sailor Moon fans here who could fill me in and tell me if I’ve described anything wrong.

Working on Sailor Moon, in any case, also got Ikuhara used to technical elements that would become part of his stylistic fingerprint. We mentioned the transformation sequence, the elaborate bank shot with accompanying music that would recur in nearly every episode. I am less sure about other Dezaki-esque elements, like jokes based on repeating the same sequence with minor variations.

Eventually, Ikuhara’s run on Sailor Moon would come to an end. The final arc of the show saw the Sailor Guardians facing... themselves, from a distant bad future. But for that final season, Ikuhara had already stepped down. Where did he go...?

You see, Ikuhara chafed under the creative restrictions placed on him by Toei. Turning down an offer from Anno to work on Eva(!), he set off to found his own group, Be-Papas, along with...

the famous shōjo manga artist Chiho Saito, animator Shinya Hasegawa, writer Yōji Enokido, and producer Yuuichiro Okuro

and before long also recruiting composer J.A. Seazer, known for his work with avant-garde dramatist-filmmaker-writer-poet Shūji Terayama - another big influence on Ikuni, incidentally. What did Be-Papas make? Just one anime, after which they disbanded. That anime was... Albert Ei-

youtube

That anime was Utena.

Oh man. This is the one.

少女革命ウテナ - Shōjo Kakumei Utena. In English, Revolutionary Girl Utena. Now the time has finally come to write about it, I’m nervous. Could I possibly do justice to Utena in a single blog post? Is that why I spent so long writing about Sailor Moon?

Let’s start with the aesthetic: French Revolution-esque outfits that would be comfortable in Rose of Versailles. A school made of white stone; architecture that is strange, avant-garde. Roses. So many roses oh my fucking god. It draws heavily on the Takarazuka Revue, which I wrote about previously on Animation Night 92 in the context of Ikuhara’s protege Tomohiro Furukawa.

Utena is about a girl called (wait for it) Utena, who attends a school of sorts called Ohtori Academy. But it’s a school only in a fairly abstract sense - it’s more like a palace. She wears a distinctive masculine uniform, and shortly after transferring in, discovers a mysterious underground duelling society who go to a strange abstract battle arena outside of school hours. There, they attempt to strike the rose from the other duellist. The winner of the duel gains custody of Anthy Himemiya, the ‘Rose Bride’. At some point, whoever possesses Anthy will gain the nebulous power to ‘revolutionise the world’. With me so far?

Utena walks in and immediately wins her first duel, establishing an initially frosty relationship with Anthy. But the White Rose duellists won’t take this lying down. Over the first series of episodes, we learn about each of the duellists and their motivating conflicts, culminating in an attempt to defeat Utena. (She walks up the stairs every time.) They lose every time, but the point isn’t really about whether Utena will win or not - it’s about introducing us to a collection of fucked up guys, and then making them even more fucked up.

But it’s not all high drama. A lot of Utena is just straight-up antics, which is to say, just about any time Nanami is on the screen. There’s a greek chorus of shadow girls who comment on the events of the episode. The broad strokes are hard to miss, but the subtler, more obtuse stuff is the sort of thing that can get you into an almost endless rabbit hole of analysis. Don’t take things too literally! You could probably call it at least a little Brechtian in how much it foregrounds its own artifice.

After Utena’s defeated just about everyone at the White Rose, the Black Rose arc introduces a new element. Now, characters from beyond the duelling circle will go down an elevator to guy who renders a fucked up sort of anti-therapy which will motivate them give into their worst impulses and have a go at Utena. Utena, meanwhile, is harbouring a complex where she needs to live up to an ideal of fairytale prince following an incident from her childhood - and oblivious to what’s actually going on with Anthy.

Then at last Anthy’s brother Akio shows up - the actual prince from the upside-down castle in the sky that represents the power to revolutionise the world, and the architect of the monstrous system. It turns out he’s been incesting Anthy, that she’s complicit in all his shenanigans (guess who was behind the Black Rose thing). Moreover, Utena is pulled in to Akio’s orbit, an ugly, abusive relationship... that is conveyed mostly through visual metaphors involving cars.

The finale is... complicated to explain. But it gives us one of the most iconic pieces of cinematic lesbianism ever animated, as Utena reaches for Anthy, refusing to be pushed away (by stabbing) or let Anthy remain in her state of self-inflicted pain, and they are able to escape the academy and its system, at the cost of being separated. What future they have outside the academy is left unspoken...

And that’s just scratching the surface. If you ask the hardcore Utena fan, just about every element of every shot is dripping with meaning. You can’t take everything too literally, but you definitely have to take some portion of it literally or you don’t have a story and characters at all.

Visually, the characters in Utena are designed by Shinya Hasegawa - and as much as they are recognisably ‘90s’, they really push it. People are long and faces - noses and chins especially - are pointy. Characters tend to be reserved and stoic in their facial expressions, unless they’re Nanami, in which case all bets are off. Animation-wise, JC Staff did the work under Be-Papas’s direction - and as much as it uses limited animation for effect, it’s really got the goods, especially in the duel sequences and the bank shots (Utena climbing the stairs? Not CG!).

Did you know Yoh Yoshinari was on it? I didn’t until today! So too was Mamoru Hosoda.

Remarkably for such a deliberately challenging show Utena was pretty successful! This was the era between Eva and Lain: it was an excellent time to be making something really experimental and push those genre boundaries. (One thing I don’t really know is how Utena got funded in the first place, but all the big names attached to the project probably gave them some pull.)

Alongside the anime came a manga by Saito - but neither is really an adaptation of the other, they’re just two different interpretations of the same general concept and premise, produced at the same time. And in fact, Ikuhara and Saito clashed heavily over the direction of the series, particularly in regards to whether the relationship between Utena and Anthy should be presented as romantic. Saito did not believe that shōjo audiences would be on board with the yuri, but Ikuhara refused to back down. (Saito eventually changed her mind.)

With all this success, they went ahead to make a movie. Now, usually a compilation movie of a successful TV series will cut out down the story to fit the runtime, reanimate a few scenes and call it a day. But this would be all but impossible with Utena, which is so tied to its episodic structure and use of repetition. And in any case, Be-Papas had bigger ambitions!

The film would be titled 少女革命ウテナ アドゥレセンス黙示録 Shōjo Kakumei Utena: Aduresensu Mokushiroku, literally Revolutionary Girl Utena: Adolescence Apocalypse, though in English it’s usually given the shorter title Adolescence of Utena. It is kinda sorta a condensed version of the series at first... and then in the latter half it goes completely off the rails. This time Akio is long dead. And he’s not the only one! It ends with this absolutely nuts sequence where Utena turns into a car to drive Anthy out of the academy, pursued by Shiori, who also turns into a car. I still can’t say I really understand it, or how it relates to the ‘car is a rape metaphor’ role in the TV series? But it looks beautiful.

Compared to the series, the movie features the expected higher drawing counts and flashier animation... but the really novel aspect is the architecture. This movie goes absolutely wild with it: the Ohtori Academy this time is far stranger and more intricate, looking less like a regular old European palace and more like something dreamed up by the Russian avant-garde.

It’s less of a summary of Utena and more of a companion piece. Seen on its own by someone who’s not familiar with either... I’m not sure how it would come across! Maybe you’ll just think I’m insane. Maybe you’ll be right.

So, some 3000 words into this post, I’ve finally told you the first movie we’ll be watching! That’s right: we’re going to jump in at the deep end and enjoy Adolescence of Utena. You don’t need to have seen the series.

After Adolescence, Be-Papas disbanded, as if following Monsieur Dupont’s injunction that radical groups must exist for a single purpose and then disband. Ikuhara left anime for a long time, like twelve years. He wasn’t entirely cut out from the industry, occasionally dropping in to storyboard an episode or two (for example, Episode 2 of Diebuster, or the OP to yuri series Aoi Hana). But for the most part, he turned his attentions to other mediums.

In that time he published a shōjo manga, which was poorly received for being a lot more conventional than Utena; he also wrote a novel called Schell Bullet which, get a load of this...

As a result of gene manipulation, society is segregated by genes into "Majors" – intersex humans who maintain a monopoly on stronger genetic material – and lesser dual-sex "Minors". (Ikuhara stated that he chose to make the Majors intersex because he wished to create "a race which combines the good parts of both women and men."[1]) Protagonist Ors Break is hired by the intergalactic trading company Balt Liner Corporation to pilot a schell, a bio-organic mecha, by claiming to be a Major. When the truth of his Minor status is revealed, he comes to an agreement with his superior, a Major named Delbee Ibus, to continue working for the organization.[1][2]

...and another serial novel called Nokomono to Hanayome, described as ‘Lolita hardboiled’ (I believe as in ‘Elegant Gothic’ rather than as in ‘Nabokov’s novel’). This last was a precursor to Penguindrum - animal costumes, the a story about the 1995 Tokyo sarin gas attacks.

In 2011, Ikuhara came back to anime. Why? And why did he leave in the first place? itsamystery.jpg. In any case, his new project was... Mawaru Penguindrum. It’s about, I guess you might say, the abandoned children of cultists who connect to a supernatural penguin being through a hat. But honestly it’s even tougher to attempt to summarise than Utena. There’s a “child broiler” involved. That’s just the start. And this post is already very long.

So, it’s time to split it. You’ll be able to read more about Penguindrum tomorrow (or later today, if you’re also staying up insanely late in the UK).

Animation Night 155, in its cosy new Sunday timeslot, will be running (if all goes according to plan) at 8pm UK time. That’s about 13 hours from the time of this post. The plan will be to watch Adolescence of Utena and the two movies of Re:cyle of the Penguindrum, for a total of about five and a half hours. (Sorry Sailor Moon fans! I’d really like to squeeze in the R movie too, but I underestimate how long Penguindrum is in movie form. We’ll find another day to do Sailor Moon though!)

If you’ve read all this so far, thanks so much! I’ve wanted to do a proper Animation Night on Ikuhara for ages, and there’s so much I can write about. So far it’s all history, but we wanna do some analysis too. For now... hold on tight.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toei's Mazinger Z is so bizarre to me, it doesn't feel at all like Nagai's manga and also for 1972 how was some of this acceptable? But it's also funny because after this, their Devilman, Cutey Honey, and even his co-created with Ishikawa series Getter Robo animes everyone was rushing to make something in those genres be BETTER. Like seeing the awful, boring, misogynist writing of these male dominated shows in the writing room get pushed out by stuff like Robot Romance, Gaiking, Raideen, Majokko Megu-Chan, Lalabel, Minky Momo, and adaptions of these aforementioned properties like the Devilman OVAs, Shin Cutey Honey, Mazinger Edition Z, Getter Robo Armageddon being leagues better than the original shows that aired alongside the manga runs. Toei's Mazinger Z is so bizarre to me, it doesn't feel at all like Nagai's manga and also for 1972 how was some of this acceptable? But it's also funny because after this, their Devilman, Cutey Honey, and Getter Robo animes everyone was rushing to make something in those genres be BETTER. Like seeing the awful, boring, misogynist writing of these male dominated shows in the writing room get pushed out by stuff like Robot Romance, Gaiking, Raideen, Majokko Megu-Chan, Lalabel, Minky Momo, and adaptions of these aforementioned properties like the Devilman OVAs, Shin Cutey Honey, Mazinger Edition Z, Getter Robo Armageddon being leagues better than the original shows that aired alongside the manga runs.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

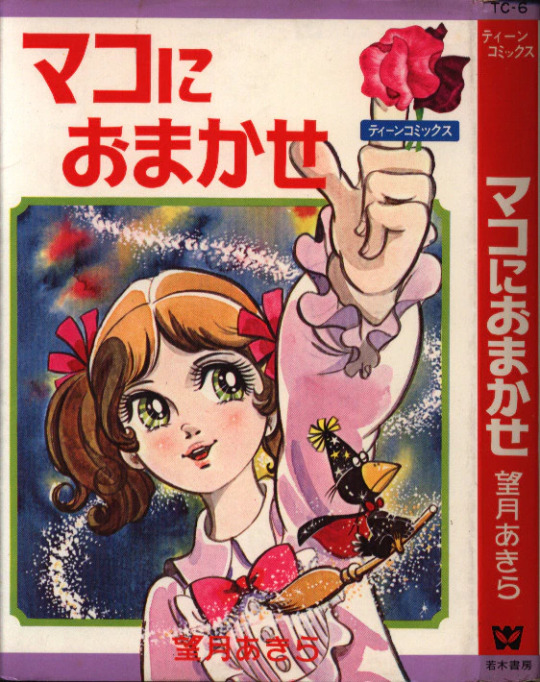

Majokko Lily

I am fascinated by magical girl terminology and the evolution thereof. After all, the words and phrases we use to describe the facets of this genre had to come from somewhere. Sometimes these origins are unambiguous. For example, the now-defunct Magical Girl Project blog made a series of posts in 2015 examining the history of magical girl transformations, and an early step in that process was coining a bunch of terms for the different types of transformation.

Other times, magical girl word origins aren't so clear cut. Some of these terms have been in use for decades and I can only hazard a guess at how long they've been around based on when they start showing up in completed productions. The term magical girl itself is a pretty direct translation of the Japanese mahou shoujo (literally magic girl), and the first anime to use mahou shoujo in its' title was Mahou Shoujo Lalabel, which began airing in 1980.

Then there's what magical girls were called before that, which doesn't seem to be as solidified. Asahi Sonorama put out a compilation record featuring the protagonists of Toei's first eight magical girl anime, and this record referred to them as mahoutsukai heroines. Mahoutsukai literally means magic user, so it's interesting that Limit and Honey were included in this despite using advanced science and technology. Even as far back as the 70s, magic was not a prerequisite for being a magical girl.

At any rate, a far more common name for this type of character was majokko. Majo is Japanese for witch, while ko has a number of meanings, one of which is girl, and it can be used as a diminutive suffix. As such, majokko can be translated as witch girl or little witch. Like with mahoutsukai heroine above, it's interesting that few of these characters were technically witches, though I suppose that's a matter of semantics. Again, I haven't found an in-depth explanation of where this term came from, so all I have to go on is productions that use it. 1974's Majokko Megu-chan was the first anime to put the word majokko in the title, and for a while I though it may have coined the term. But it turns out, there is a manga that dubbed its' protagonist a majokko about six years prior.

Majokko Lily is a 1968 manga by Kiyoshi Takenaka. An ordinary girl named Deko-chan is given a peculiar-looking doll for her birthday, but it turns out Lily is no doll. She's a witch from the underworld who has come to our world to make mischief. She sets herself up to pose as Deko's younger sister and when the two touch noses, Deko is able to use magic as well.

This set-up has some similarities to later magical girl works, especially Majokko Tickle (which, for context, was created ten years later); however, Lily's character design and power set strike me as quite unique. The above page explains Lily's various magical abilities, and while I don't know nearly enough Japanese to translate it in its' entirety, there are some powers listed on it that I haven't seen in any other magical girl series before or since.

Majokko Lily was published in Shogaku Sannensei, and unfortunately it has been quite difficult to track down exactly when that publication was. As near as I can tell, the debut chapter was printed in the April 1968 issue, given that it was the oldest issue to show Lily on the cover. While I don't have an exact chapter count, a single tankobon volume was released by Mushi Productions as the 6th volume of their Best Comic series on March 25, 1972.

But wait there's more! This manga would receive a direct sequel titled Oshikake Majokko Lily (Oshikake I think in this context would mean uninvited visitor but please correct me if I'm wrong) which ran in Shogaku Sannensei until the March 1972 issue. How the sequel differs from the original, I'm not sure. The tankobon release by Mushi Productions only covered the original series, meaning this sequel has never been printed outside of its' original magazine run. As well, even that one volume has never been reprinted, which has kept awareness of the manga quite low, even in comparison to other titles I've covered here.

Majokko Lily was created by Kiyoshi Takenaka, not to be confused with Kiyoko Takenaka, the latter of whom did the third manga of Bewitched. It is interesting that both created a small handful of obscure shoujo manga around the same time, and I have seen some speculation that they may have been either related or one person using a pseudonym, but as far as I know there's never been any confirmation of this. Personally, my money is on weird coincidence.

Although I can't say this with 100% certainty, Majokko Lily appears to be the first series to use the word majokko in its' title. I doubt Takenaka invented the word, but from there it would show up in the titles of a number of other magical girl stories. This includes early magical girl anime such as Majokko Megu-chan, Majokko Tickle, and Majokko Club, as well as some more recent anime like Majokko Shimai no Yoyo to Nene, not to mention manga that should be showing up on this blog as we get into the 80s and 90s, including Majokko Carnival, Majokko Tenshi, and Majokko Vivian.

Not all of these protagonists are witches in the technical sense, but referring to them as majokko highlights their commonalities to a potential audience. It associates these different works with one another, emphasizing that they're a part of the same genre, and allowing that genre to develop a core viewer base. Even now, the same thing is done with different terms, and it's incredible to look back at how far we've come.

#my posts#long post#Majokko Lily#魔女っ子リリー#Oshikake Majokko Lily#おしかけ魔女っ子リリー#Kiyoshi Takenaka#竹中きよし#Shogaku Sannensei#60s#shoujo#It was A Time™ trying to find specific details about this manga#so apologies for how wishy-washy some of the details sound and how incomplete certain sections are.#Also#literally the same morning I posted about not having any 70s manga in my timeline#I found three!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mahoutsukai Sally – translated opening lyrics –

! translation not mine !

Mahariku maharita Yanbara yan yan yan Mahariku maharita Yanbara yan yan yan

From the land of magic, came a charming, little girl, sally, sally, with her mysterious powers, she has filled the city with dreams and laughter, sally, sally, sally the witch (Yay!)

Flying on a broom in the sky, came a silly little princess, sally, sally, when she chants her magic spells, love and hope spring forth, sally, sally, sally the witch

Sally, sally, sally-chan!

mahoutsukai sally, toei animation 1966-1968

youtube

note: I wanted to start a series where I translate or pick and rewrite here the translatioms of majokko openings. We start with the first majokko anime, by toei animation, Sally the witch, one of my favourite witch. up there is the video where I copied the traslation. Next time I'll try to translate other openings by myself, very soon!

Bye for now !<3

‧͙⁺˚*・༓ ༓・*˚‧⁺˚*・༓ ༓・*˚⁺‧

#majokko#toei animation#70s#vintage#mahou tsukai sally#sally the witch#mahoshoujo#mahoucore#openings#Youtube

0 notes

Text

A Completely Incomplete History of the Magical Girl Subgenre in Manga and Anime, pt. 2

Welcome back to my occasional, completely unscientific, very self-indulgent look at the evolution of the magical girl subgenre! In my first post, I said that the subgenre can be loosely divided into three generations, starting with series like Sally the Witch and Majokko Megu-chan in the ‘60s and ‘70s. In this post, I’ll describe the second generation of magical girls: the new crop of shows starting in the early ‘80s that added some interesting elements that would transform the subgenre. Come join me below the break, gentle readers!

First, a quick recap. When talking about such a specific segment of pop culture, it’s helpful to have a definition to narrow one’s focus and keep things on track. In my first post, I attempted to define the magical girl subgenre as best I could; what I came up with was a series in which the main character(s) are girls, typically teenagers or pre-teens, who have access to magical or otherworldly abilities in what is otherwise a normal, real-world setting, which are used in conjunction with personal strengths and virtues to solve problems and/or achieve their goals, and which they must keep concealed from other people who aren’t in on the secret. Again, it’s not the most scientific definition—it’s a pretty broad net, including some works it probably shouldn’t and excluding a few it should—but it’ll do for this analysis.

Series like Mahoutsukai Sally and Majokko Megu-chan in the ‘60s and ‘70s were popular, running for multiple years and getting translated into other languages and spreading to other markets, but compared to other series they were modest successes. They didn’t have the cultural impact and staying power of other series from Toei around the same time—Cyborg 009 or GeGeGe no Kitaro in the late ‘60s, or Mazinger in the early ‘70s. And while Toei kept periodically making magical girl series—for example, Mahou Shojo Lalabel in 1980—the formula did not substantially change. The second generation of magical girl would come from a different studio, a newer contender in the world of anime: Studio Pierrot.

Toei Animation was (and is) one of the original giants of anime, having been founded in 1948. Studio Pierrot was founded in 1979 by former employees of other studios, and was trying to make a name for itself. It had already hit upon a pretty successful franchise with its adaptation of Urusei Yatsura in 1981, and was starting production on a number of new series. (Urusei Yatsura also sort of fits the “magical girl” definition, and has proved one of Pierrot’s most enduring and beloved properties, but I’d argue that it’s not nearly as important in the history of the subgenre as the series I’m about to describe. Material for a future post, I suppose.)

For one of these new series, Pierrot decided to use the strategy of “media mix,” an idea that’s been around in Japanese pop culture since at least the 1960s but which had only recently acquired a name. To quote Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan by Marc Steinberg, media mix is “the development of a text across numerous media, among which anime plays a key role in popularizing the franchise; the dependence on other incarnations to sell works within the same franchise; and the use of the character as a means of connecting these media incarnations.” Basically, the idea is to build a franchise by using characters or ideas across multiple media, something that would reach perhaps its ultimate form in the Pokemon franchise a decade later. In this case, Pierrot would promote the music of a newly-acquired idol singer, Takako Ota, by making her the voice of the main character in a new anime series, Magical Angel Creamy Mami (Mahou no Tenshi Kurimi Mami), which premiered in July of 1983.

The “idol” is a specifically Japanese celebrity type, a young female starlet who generally appears on TV shows, in magazines, and especially in pop music. They’re usually presented and sold on the strength of their cute, pure, “girl next door” image, which means that their image is tightly controlled and heavily managed. It’s sort of the Hollywood idea of the “ingenue,” turned up to eleven and corporate-controlled. Now, if you remember, in my first post I noted that you can trace the development of the first magical girl series directly to the American sitcom Bewitched. These shows were putting their own spin on a fairly simple narrative: a girl with magic powers in a mundane world, dealing with simple problems and the occasional, unthreatening, cartoonish villain. In the same vein, you can trace the development of the second generation of magical girls to the introduction of this new pop-culture figure, the idol.

In Magical Angel Creamy Mami, Yu Morisawa is a normal 10-year-old girl, until the day she helps a small alien in his giant, invisible spaceship. For her help, she’s granted a magic wand with a variety of ill-defined powers and two helpers: talking cat-like creatures named Negi and Posi. Yu uses her powers to transform into a glamorous 16-year-old version of herself, who is quickly discovered by a record company and turned into a pop star by the name of Creamy Mami. She must navigate the demands of stardom while also occasionally solving strange magical problems and helping her friends.

I can’t claim to have any special insight into the minds of the show’s creators, but it seems pretty clear to me that Creamy Mami was tailored to fit the image of Takako Ota specifically, and the pop idol in general. The idol must be fresh and innocent even while being perfectly at ease with the demands of celebrity—both naive and media-savvy simultaneously—so our heroine is ten years old, but able to transform into an older, more mature form. She must be talented, but not seem ambitious—she must seem as though she has been plucked from her home without any preparation or training—so Yu is literally discovered by accident and pulled on-stage without even knowing she’s expected to sing, and uses magic in order to perform. The lengthy process of makeup and wardrobe is simplified into a glamorous transformation sequence: instant beauty, no hard work required! The idol is part of a massive pop-culture machine, but must seem like a completely ordinary girl who is never pressured by stardom, so the series has a hefty dose of comical magic antics and wacky side characters without any major consequences for our heroine. (The only recurring antagonists in Creamy Mami are a rival singer who resents the new, younger, cuter Mami, and an unscrupulous paparazzi named Snake Joe.) The overall premise of the series, with our main character being an idol herself, meant that Takako Ota’s musical talent was heavily featured, with one of her songs in the course of most episodes, in addition to both the opening and ending themes.

Many of the elements of the modern magical girl already existed prior to Creamy Mami—for example, transformation sequences were a part of series like Fushigi na Melmo and Himitsu no Akko-chan, as was the main character being a normal girl given magic powers rather than an inherently magical girl, and the cute funny sidekicks have been around since as early as Ribon no Kishi—but I would argue that they acquire a new importance and resonance when combined with the image of the idol. The glamor and pageantry of pop culture synthesizes nicely with the fantastic elements of the magical girl, while the dual nature of the celebrity—and in particular the idol, expected to be both untouched child and glamorous star—becomes something literally otherworldly, an amazing other self given by a being from the sky. By choosing a pop idol as both the main character and chief voice actress for Creamy Mami, Studio Pierrot had created a fusion of pop-culture archetypes that would become a huge success. The second generation of magical girls had begun.

Creamy Mami ran for 52 episodes and several original video animations (OVA), proving quite popular for the new studio. It finished in June 1984, and Studio Pierrot immediately followed up with similar series, each lasting for about a year: Persia the Magic Fairy (Mahou no Yosei Persia), Magical Emi the Magic Star (Mahou no Suta Majikaru Emi), and Pastel Yumi the Magic Idol (Mahou no Aidoru Pasuteru Yumi). Each of these series had the same basic premise—young girl is given some kind of magic power by a magical being and uses it in her otherwise normal life—although surprisingly, despite the success of Mami (and the title of Yumi), none of these later series re-used the premise of the character being a pop idol.

(I hear some of you cry: “That’s it? Four series, each a year long, all from a single production company? That’s what you call a generation?” And it’s true! By the standards I lay out, the second generation of magical girls is extremely small. But I would say that these four series, Mami in particular, are crucial to the history of magical girls. Think of this as a vital transitional period for the subgenre, a relatively brief moment in pop culture that would soon be superseded by newer, more popular works—the equivalent of Archaeopteryx linking dinosaurs and birds, these series bridge the gap between Sally the witch girl and Sailor Moon. Additionally, I’m mostly talking about series and developments in chronological order; while this period in the mid-80s is the birth and peak of the second-generation magical girl, there have been later series that fit this category.)

So what are the new elements added by the second-generation magical girl? As I see it, there are two: first, the ordinary girl and the magical girl are two distinct characters which require a visible transformation. As I said in the final paragraph of my first post, while the magical girl has always had to hide her abilities, only starting with this generation does she hide her identity behind another full-fledged persona. The opening credits of Mami show Yu and Mami’s faces spinning around like opposite sides of a coin. Creamy Mami is in fact even more separate than most other examples in the subgenre; not only does she look completely different from Yu, she is specifically described as six years older than her “normal” self. Again, this is the archetype of the pop idol given a fantastic spin; the “celebrity” is a different person from the “person.” (Think, for example, of Hannah Montana!) Connected to this first point, second, an emphasis on costume, pageantry, and physical transformation into a more glamorous self. This is also at least partly due to improvements in animation allowing for more impressive spectacle, but the creators certainly made good use of it. Mami is dynamic and colorful, obviously far more so than its black-and-white precursors. It is also more toyetic than previous magical girl shows, par for the course for a media mix show; Mami uses a magical compact and wand to transform, plastic replicas of which could be bought as accessories, and stuffed animal versions of her fairy companions were available as well. (To be fair, Mami was hardly the only series from this period to be merchandised so heavily.) To what degree the pageantry influenced the desire to make toys, or vice versa, I can’t say, but they certainly go hand in hand from this point on.

There are also elements of this generation that have become staples of magical girl series—the cute sidekicks, the magic trinkets—but I think those are not truly essential, or rather, that what is essential about them is included in my second point above. To put it simply, the second-generation magical girl is surrounded by more stuff—a wand, some talking cats, magical accessories—all of which add to the pageantry (not to mention the merchandise).

There’s another element which I don’t think is necessary for or specific to the second-generation magical girl, but which also deserves a mention: Mami and other shows are aimed at a slightly older audience than Akko-chan or Sally, and the characters are children who often have to navigate adult worlds. Mami is in the music business; the main character in Magical Emi is a young girl who participates in her family’s magic shows. Even in shows where the character is not specifically participating in an adult sphere, they still find themselves in the position of having to act like adults: in her very first episode, Persia tries out her new magic by transforming into a policewoman and tricking her friends. These characters have a child’s perspective on adult problems, and while they can sometimes help the adults in their lives, they are still often flummoxed by the mysteries of the grown-up world. I think this is largely a matter of changing pop-culture expectations, a recognition that older girls—relatively older, that is, pre-teens and teenagers—were watching these shows, and would want to see characters closer to their own age, or at least dealing with similar problems. Again, I don’t think this is a defining feature of this generation of magical girls, but it’s something that will come up in other series and which should be noted.

That covers the second generation of the magical girl subgenre! And boy, are my fingers tired. Join me for the third installment, in which we finally reach the series that would define “magical girl” in both Japan and the rest of the world, and which would leave an indelible stamp on the genre—and anime as a whole—that has lasted to today. You know the one I mean.

#magical girl#magical girl history#mahou shojo#creamy mami#studio pierrot#scsg!#persia the magic fairy#magical emi the magic star#pastel yumi the magic idol

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kirakira Pretty Cure a la Mode, la serie arriva su Crunchyroll

Tutti gli episodi dell’anime sono già online sulla piattaforma!

A grande richiesta arriva finalmente anche in Italia “Kirakira Pretty Cure a la Mode”, la quattordicesima serie del popolare franchise Pretty Cure (abbreviato comunemente in PreCure), creato nel 2004 da Izumi Todo e ormai un vero e proprio fenomeno in patria (e non) nel genere majokko.

Diretta da Yukio Kaizawa (Zatch Bell!) e Kouhei Kureta (Precure Miracle Universe Movie) presso gli studi Toei Animation, la composizione della serie è stata curata da Jin Tanaka (Laid-Back Camp, Anne-Happy), mentre il character design è ad opera di Marie Ino. Tutti i 49 episodi andati originariamente in onda fra il 2017 e il 2018 sono già disponibili in streaming su Crunchyroll, sottotitolati in italiano.

La storia di Cure Whip e delle guardiane dei dolci sta per iniziare!

Sono Usami Ichika, frequento la seconda media e adoro tanto, tanto , tantissimo i dolci! Quando ho saputo che mia madre stava per tornare dal suo lavoro oltreoceano, ho deciso di cimentarmi nella creazione di un tortino monoporzione solo per lei!

Proprio in quel momento...

"Sono pekopeko affamata, peko!"

... una fata chiamata Pekorin è precipitata dal cielo! Mi ha spaventata a morte, ma era solo l'inizio! Esplosioni di crema pasticcera, ladri di torte... ogni genere di stranezza è iniziato ad accadere in città! Per giunta, come si è scoperto, c'era un assurdo mostro dietro a tutto ciò! Stava rubando l'energia kirakiral che si trova nei dolci, rendendoli tutti scuri!!

Non avrei mai permesso che ciò potesse accadere al mio dolce. È una dimostrazione d'amore verso mia madre, dunque per me è prezioso. Ma proprio nel momento in cui stavo dando gli ultimi tocchi al mio tortino Ichika special bunny... mi sono trasformata nella leggendaria pasticcera, Precure!"

Ora, come Cure Whip, proteggerò i dolci che le persone usano per esprimere i propri sentimenti verso gli altri!

Al momento, l’unica altra serie del franchise disponibile in Italia è quella prodotta nel 2012 dal titolo “Smile Precure!” (arrivata però a noi come Glitter Force). L’edizione che trovate su Netflix, però, ricalca l’edizione americana ed è composta da 40 episodi e non 48 come l’originale.

* NON VUOI PERDERTI NEANCHE UN POST? ENTRA NEL CANALE TELEGRAM! *

youtube

Autore: SilenziO))) (@s1lenzi0)

[FONTE]

#anime#majokko#precure#pretty cure#serie tv#sub ita#newsintheshell#news in the shell#streaming#on demand#kirakira pretty cure a la mode#cartoni animati#animazione#giappone#dolci#magia#crunchyroll

0 notes

Photo

Anime visti nell’Estate 2019 + 1

(Commenti non troppo lunghi perché ne è passato di tempo. Ma sono soddisfatta che ben 3 su 4 siano doppiati.)

✓ Miraculous - Le storie di Ladybug e Chat Noir: Serie 3

[ Miraculous, les aventures de Ladybug et Chat Noir: Saison 3 ]

[ 26 episodi | 2018-2019 | Studi: Zagtoon, Toei Animation, SAMG Animation, Method Animation | ITA su Disney Channel ]

[ Majokko, Supereroi, Azione, Commedia, Sentimentale ]

→ [ Sulla prima serie ] [ Sulla seconda serie ]

Ritorna Miraculous dalla trasmissione sofferta - anche se, c'è da dire, molto meno sofferta della seconda serie -, dalle première multilingue (stavolta non abbiamo avuto solo americano, francese e spagnolo, ma persino ucraino!) che hanno sempre un che di affascinante.

Ogni serie che passa, Miraculous diventa sempre più bello e questa terza serie, se si eliminano, ehm, l'inizio e il finale considerato finale solo dagli autori, è al momento la più bella del franchise.

Episodi molto belli sono Boulangerix, dolce ed intimo, con uno strano vibe che risulta più chiaro una volta scoperto che è biografico dell'autore; Poupeflekta, dove finalmente si vede qualcosa tra Juleka e Luka e lo swap di Lady Noire e Mister Bug è adorabile (peccato Lady Noire risulti piuttosto antipatica); Silence, dove qualcuno riesce a far alterare Luka e quest'ultimo parla più in questo episodio che in tutta la serie - e la sua dichiarazione è stupenda; Miraculeur perché FINALMENTE C'È LA SQUADRA, finalmente Mayura entra esplicitamente in scena e Queen Bee è fantastica; Oblivio è la quintessenza dell'adorabilità e del fluff; Ladybug rasenta il brokoro e Marinette e sua madre erano prossime all'akumatizzazione (Il fatto che fosse akumatizzata insieme a sua madre l'ho trovato abbastanza interessante, chissà se lo terranno, in futuro).

Ma episodi che vincono a mani basse, mani alte e mani di lato sono Papa Garou, Desperada, Chat Blanc e Félix.

Papa Garou si meriterebbe di aprire la serie: simbolismi financo nel più minuscolo dettaglio, riferimenti alle favole super azzeccati ed è sempre bello vedere il legame tra un padre e sua figlia.

Desperada, a sorpresa, non catalizza la sua attenzione su Viperion ma su Aspik, su Adrien, sul fatto che al momento Marinette sarebbe troppo rimbambita dall'idea di avere Adrien al suo fianco per fare una Ladybug che non si fa sconfiggere ogni tre secondi - di contro, Adrien capisce qual è la sua strada, soffre per tutti i riavvolgimenti temporali e trova la forza di staccarsi dalla sua idealizzata Ladybug. È uno scambio di fiducia: Marinette si sente pronta ad affidare un miraculous ad Adrien, Adrien decide di rimanere se stesso come Chat Noir, di vedere Ladybug come una ragazza normale e di consigliare di dare il miraculous a Luka, suo rivale in amore. Un episodio pervaso da una strana malinconia, non tanto incarnata nell'akuma quanto nel suo nome. (So che qualcuno odia questo episodio perché non è Viperion-centrico. Non commento neppure.)

Chat Blanc è il palese climax della terza serie (e probabile precedente climax dell'intera storia, quando in origine le serie erano solo tre). La tensione è palpabile, per essere un cartone per bambini è abbastanza inquietante, la patina opaca della Parigi del futuro concretizza il senso di "sbagliato" e Benjamin Bollen ha fatto la sua prova migliore in assoluto in Miraculous. Ogni secondo di questo episodio è studiato nel dettaglio, tra richiami, simbolismi, canzoncine brokoro e sguardi creepy che di certo non ci si aspetterebbe in un prodotto per un target basso. A parer mio l'episodio più bello mai prodotto di Miraculous.

Félix è il palese finale della terza serie, checché ne dicano gli autori. Félix è altezzoso, rancoroso, dispettoso, tsundere e istantaneamente uno dei miei personaggi preferiti di Miraculous. FancuBizza Gabriel, è pronto a portare via Adrien da quella villa di falsità: voglio più episodi con lui. Sì, è presentato quasi come un Gary Stu, ma c'è da dire che Ladybug zampetta felice sulla corda tesa sopra il barato Mary Sue, quindi- Ah, una cosa: sono genuinamente sorpresa del fatto che NON sia stato akumatizzato e che l'episodio si chiami come il personaggio, non come l'akuma (Già successo giusto con "Ladybug e Chat Noir" e "Mayura", cosa che fa ben sperare).

Ora, dopo tutto questo amore per la terza serie, passiamo alle cose brutte. Non tante, per fortuna, ma belle grosse.

Personalmente, ci sono due cose che non mi hanno convinta: l'assenza della Squadra e il risparmio imbarazzante sui modelli degli akuma.

Il primo non lo capisco. C'erano occasioni su occasioni di mettere non dico tutti e tre tra Rena Rouge, Carapace e Queen Bee, ma almeno due... uno, vabbè. Ma niente. Miraculeur e via. Giusto in Startrain mostrano il loro "lato eroico" anche da civili, ma mi piacerebbe vedere anche gli altri supereroi oltre ai sempiterni protagonisti... D'accordo, questa serie era dedicata al dare miraculous a destra e a manca. Ma non cambia che in qualche episodio potevano anche metterci gli altri del trio.

Discorso a parte per Nino, che già non ha screentime da "civile", figurarsi se gli danno un po' di spazio come supereroe-

La seconda cosa che non mi ha convinta è facilmente spiegabile con il fatto che hanno dovuto fare frotte e frotte di nuovi modelli per i nuovi supereroi. E lo capisco, eh!

Tuttavia, i design belli sono... tre? (Ne ho scritto QUI!) Gli altri o sono akuma riciclati o hanno design poco interessanti.

Tra l'altro, non è che mi abbia convinta granché neppure quel bel discorso di Alya sulla sua preoccupazione di essere di nuovo akumatizzata... per poi essere akumatizzata di nuovo qualche episodio dopo, come se non avesse mai aperto bocca. (Okay l'ordine cronologico a caso, ma...!)

Adesso iniziamo a scavare.

Caméléon è brutto.

È il primo episodio ed è palesemente una beta - tanto che io sono convintissima che Lila dovesse akumatizzarsi in una kitsune (cambia forma, assume la forma di chi bacia, lei è una volpe, nella serie non mancano certo i riferimenti alla cultura giapponese...). Tayr lo vide per prima e me ne parlò male, ma così male che ho deciso di non vederlo. Dato che sarei kattywah se parlassi male di un episodio che non ho visto, lascio la parola a Tayr, che esplica perfettamente perché questo fantomatico "primo episodio" possa far passare la voglia di vedere la terza serie. (Dopo che me lo narrò, dissi letteralmente: "Avvisami quando ci sono episodi belli", perché non avevo intenzione di seguire una serie che si apriva così. Poi arrivò Papa Garou e il resto si sa. (?))

→ [ Tayr spiega i problemi di Caméléon ]

Heart Hunter e soprattutto Miracle Queen fanno schifo.

Non è che sono brutti, fanno proprio schifo, ma uno schifo che non credevo possibile in Miraculous. Il picco di schifo è talmente tanto che persino la serie stessa si è ribellata, facendo sì che questi due abomini (che gli autori si ostinano a chiamare "finale") venissero trasmessi prima dell'invece bellissimo finale effettivo (Chat Blanc e Félix).

QUI ho spiegato cos'è che non mi ha convinto di Miracle Queen e, in generale, del """""finale""""" della terza serie. Fu un commento fatto a caldo, quindi molto sentito - anche se non avevo ancora realizzato appieno quanto fossero esecrabili questi episodi (Talmente brutti che devo pure cercare nel dizionario qualche parola che possa rendere appieno la loro bruttura!).

A parte tutto, trovo affascinante come Heart Hunter e Miracle Queen mi avessero fatto venir voglia di evitare le nuove serie, mentre Chat Blanc e Félix mi abbiano hyppata. È proprio vero che basta un finale per cambiare completamente la percezione di una storia!

P.S.: Ho avuto modo di sentire il doppiaggio italiano.

Evitatelo. Era da tanto che non sentivo un doppiaggio così annoiato, vuoto, passivo - è tutto letto, con un accenno di intonazione tanto per gradire. E suppongo che gli adattamenti dei nomi degli akuma siano fatti tirando a sorte, dato il miscuglio nonsense di traduzione fedele, nomi inventati, nomi in francese e nomi in inglese senza soluzione di continuità.

.

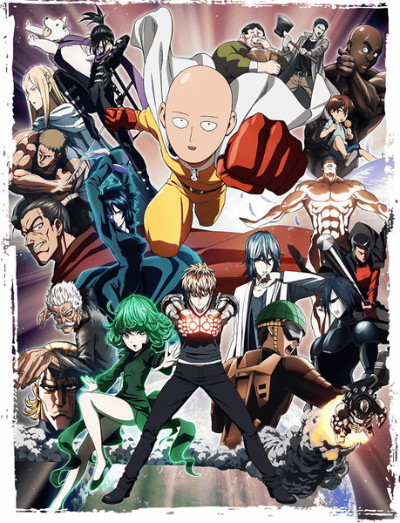

✓ One-Punch Man

[ ワンパンマン]

[ 12 episodi | 2015 | Studio: Madhouse | ITA su VVVVID ]

[ Parodia, Supereroi ]

Ricordo che ebbe gran successo alla sua uscita: era "l'anime del momento", si era persino creata una strana idolatria per la opening (che carina è carina, ma non ci vedo niente di rivoluzionario, dato che fa molto anni '70); così, avevo vagamente pensato di vederlo. Poi Tayr mi ha fatto notare che era doppiata su VVVVID, quindi non ho potuto rifiutare. (?)

Insomma, i primi due episodi mi avevano fatta ribaltare dalle risate. Tuttavia, avevo un dubbio: come avrebbero fatto a portare avanti una trama che vede come protagonista un uomo invincibile?

... Beh, non l'avrebbero fatto. Dal quinto episodio in poi, da quando viene introdotta l'Associazione Eroi, Saitama passerà ad essere insultato da tipo Chiunque e ci si concentrerà su personaggi a caso. A malincuore, confesso che questo espediente non solo non mi è piaciuto, ma mi ha fatto scemare tutto l'interesse per OPM. Addirittura, quasi a fine serie, mi ero dimenticata fosse una serie parodica. Non che inizi a prendersi sul serio, beninteso: semplicemente, da parodia pura diventa uno shonen sassy con un po' di battute.

Perché non ho messo ? invece di ✓, dunque?

Perché ci sono degli episodi stupendi: quello dello scienziato, quello in cui Saitama manda platealmente a fancuBo tutti quelli che lo ricoprono di sterco e tutto il miniarco del Re degli Abissi, per me la parte migliore della serie. Perché Genos è adorabile ed è il personaggio migliore di OPM - difatti, con il passare degli episodi, pure lui finirà nelle retrovie per dare spazio a gente su gente su gente. Perché il fatto che la storia cambi direzione non è un vero e proprio difetto in sé, dato che succede abbastanza presto, al quinto episodio.

Il doppiaggio mi è parso di ottima qualità e Alessandro Campaiola e Flavio Aquilone sono fantastici, azzeccatissimi sui loro personaggi. Sono piacevolmente stupita dal fatto che nomi di eroi e colpi siano stati tradotti, perlopiù in modo sensato.

OPM mi ha fatto ridere, finché è stato una parodia. E certi episodi rimangono bellissimi. Personalmente, però, non sono interessata a seguire la piega che ha preso la storia.

.

✓ DanMachi - La Freccia di Orione

[ 劇場版 ダンジョンに出会いを求めるのは間違っているだろうか -オリオンの矢- | Gekijouban Dungeon ni Deai o Motomeru no wa Machigatte Iru Darouka -Orion no Ya- | Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon? The Movie: Arrow of the Orion ]

[ Film | 2019 | Studio: J.C. Staff | Inedito ]

[ Botte, JRPG Style, DovrebbeEssereHaremMaVabbè, UnPo'DiEcchi, Commedia, Drammatico ]

→ [ Sulla prima serie e l'OAV ]

Ho visto questo film abbastanza mesi fa, quindi non lo ricordo benissimo al 100%.

Ma ricordo la malinconia di fondo: la malinconia di Artemide, la malinconia di Estia, la malinconia dello spettatore quando, a nemmeno metà film, ha già capito e aspetta il momento in cui sarà Bell a scoprire il segreto di Artemide.

Ricordo le scene di Artemide ed Estia, il calore famigliare che tanto mi era piaciuto già nella serie. Ricordo quant'era bello e scenografico l'Arco di Artemide, letteralmente la mezzaluna nel cielo.

Certo, ricordo anche che mi è parso ci fosse molta ma molta più fanservice che nella serie, che ci fosse un surplus di maniaci e che gli unici fruitori della fanservice fossero quelli interessati ai corpi femminili; ricordo anche che la componente harem era piuttosto comica, dato che Artemide è una dea lesbica (ma Orione è considerato anche un suo amato, quindi ve la passo).

Soprattutto, ricordo il mio dubbio finale: ma quindi, Bell era effettivamente la reincarnazione di Orione o era Artemide a volerlo vedere così e ha fatto in modo che le cose andassero come sono andate?

Anche se non l'ho del tutto presente, ho un buon ricordo di questo film.

.

✓ Toradora!

[ とらドラ!]

[ 25 episodi | 2008 | Studio: J.C. Staff | ITA su VVVVID ]

[ Romantico, Commedia scolastica, UnPo'DiAngstBrokoro, CelebreEsemplareDiTsundere ]

Toradora! è definito un capolavoro dello shoujo, è strafamosissimo e sembra non possa mancare nelle liste di shoujo/slice of life da consigliare assolutamente.

Secondo il mio modestissimo parere, si merita la sua fama.

Il primo impatto è piuttosto brutale e non necessariamente positivo: credo che tutti sappiano che Taiga Aisaka è una tsundere - una delle Tsundere Per Antonomasia degli animanga, per la precisione! - ed è "scontato" sia aggressiva fuori e tanto buona dentro. Ecco, non è che Taiga è aggressiva, Taiga è violenta, rabbiosa, in un modo quasi inquietante; bastano pochi episodi, però, per capire che Taiga non è un'adorabile tsunderina moe ma una ragazza che ha un sacco di problemi psicologici, che ha bisogno di aiuto e che non basterà qualche frase azzeccata per far breccia nel suo cuore e sciogliere la sua corazza d'ira. Ryuuji, d'altra parte, potrebbe quasi sembrare succube, o potrebbe sembrare che in realtà stia usando Taiga per sfogare un forte istinto da crocerossina. La verità è che, come da titolo ("La Tigre e il Drago"), sono due opposti complementari che, forse a volte un po' brutalmente, aiutano l'altro a superare i propri problemi e a "riempire quel vuoto" che sentono nelle loro vite. Sono opposti (lei è ricca, lui è povero, lei non ha troppa manualità, lui è un casalingo skillato, lei è incosciente, lui è prudente, lei è arrogante, lui è umile), ma hanno tanti punti di contatto (un padre che li ha "lasciati", una madre a cui vogliono bene ma che al momento meno opportuno vuole intromettersi nelle loro vite, una cotta non ricambiata, una non voluta popolarità a scuola) e ne prendono pian piano coscienza.

Quel che è bellissimo e palesissimo, però, è il fatto che in realtà Taiga e Ryuuji siano una coppia effettiva tipo dal secondo episodio.

Una cosa che mi ha sempre un po' rattristato degli animanga è che non si trova una coppia di fidanzati già fidanzati e felicemente fidanzati manco a pagarla - tutti si mettono insieme alla fine, se va bene a due minuti dalla fine, oppure hanno un sacco di problemi sentimentali spesso basati sul nulla -, e vedere protagonista una coppia è stata una grande soddisfazione. Ma, se siete d’accordo con me, non stappate lo spumante: nonostante si comportino come una coppia e nonostante tutti pensino siano una coppia, anche loro si metteranno ufficialmente insieme tipo al penultimo episodio. Questo perché il loro fidanzamento la loro alleanza prevede che si aiutino a vicenda per conquistare i loro "grandi amori", Minori e Kitamura. Sì, sono due fidanzati che aiutano il compagno a conquistare il/la proprio/a migliore amico/a. È comico come sembra.

Quanto a Minori e Kitamura, direi che l'anime stesso si concentra molto di più sulla prima; Kitamura ha il suo spazio e il suo archetto, ma Minori è quasi onnipresente ed è a tutti gli effetti la comprimaria principale. Probabilmente perché si sa già che Taiga non ha alcuna speranza con Kitamura, mentre a Minori piace Ryuuji ma sa che lui starebbe meglio con Taiga. Per fortuna, questa parte "drammone shoujo" non è la totalità del suo personaggio e non viene trascinata con troppa melodrammaticità.

Un elemento che ho trovato molto bello è che Taiga e Minori sono effettivamente amiche: si vogliono bene e si vorranno bene fino alla fine, non c'è nessun voltafaccia, anzi, finiscono con l’essere anche troppo premurose l’una verso l’altra.

Infine, lei: Ami. Sapevo che questa "Ami" fosse un personaggio molto popolare. Ma non avevo capito.

All'inizio, è una mitraglietta di odio: presentata come bellissima, fighissima e buonissima Mary Sue, si scopre che in realtà ha la patente di Str0nza Fiera Di Esserlo, con un master in Baldraccaggine, una vamp/dark lady che si finge una tenera Biancaneve innocente, ben decisa a rubare Ryuuji all'odiata Taiga. Con il passare degli episodi, Ami assurge al ruolo di personaggio più Epic Win di tutto Toradora!: dato che tutti i protagonisti sanno della sua doppia faccia, non la prendono sul serio e appare come una specie di buffa antagonista fallita; quando è il momento, però, manda a fancuBo chi si fa viaggi mentali stupidi; in uno strano evolversi degli eventi, diventa la (aggressiva) voce della coscienza di tipo Chiunque, scatenando applausi da parte degli spettatori per ogni dove. Seppur in modo brutale, Ami costringe Taiga/Ryuuji/Minori/Kitamura/PassantiRandom a stracciare le loro bugie e le loro esitazioni e a passare all'azione, ad essere onesti con se stessi. Inutile dire che la stessa Ami è conscia di dover, in qualche modo, provare a seguire i suoi stessi consigli.

Ami è una delle personagge che ho preferito di questa storia. Minori e Kitamura fanno il loro onesto lavoro. Ryuuji è fortunatamente buono ma non zerbino e deve darsi una calmata con il suo essere un casalingo clean-freak. Taiga è un personaggio più complesso di quanto la sua fama di Tsundere Con La T Maiuscola possa far pensare.

Quanto a Taiga e Ryuuji insieme, li ho trovati una coppia adorabile - e la loro "fuga" negli ultimi episodi è sinceramente romantica, nel suo totale essere impulsiva e disagiata, nel suo trovare aiuto dai loro amici (Minori, Kitamura, Ami), nel suo voler trovare la sua conclusione nel matrimonio, nel suo far sì che tutti i "problemi di famiglia" trovino la loro lieta risoluzione.

Dopo aver parlato tanto dei personaggi, vorrei fare un appunto alla storia: nonostante il suo concentrarsi sul lowwoh nelle sue varie forme, mi ha molto stupita il trovare delle tematiche anche un po' pesanti. Ad esempio, Ami è vittima di stalking, la madre di Ryuuji è una ragazza madre che è scappata di casa, Ryuuji vorrebbe che Taiga si riconciliasse con suo padre soprattutto perché proietta in loro la sua situazione e il suo desiderio di "avere" un padre e il padre di Taiga è uno stronzo che arriva ad usare sua figlia per i suoi affari, figlia che nonostante tutto, in fondo al cuore, vorrebbe avere occasione di dargli una possibilità di redenzione - che non arriverà mai. Ognuna di queste tematiche è trattata con il giusto peso e la giusta delicatezza.

L'edizione italiana. Ho sentito le peggio cose sull'edizione italiana, ma a me non è parsa così abominevole: non è Unlimited Blade Works o Death Parade, ma non è neanche Pokémon: Generazioni - è onesta. Di abbastanza imbarazzanti ci sono solo alcune comparse che recitano come se stessero facendo la recita dell'asilo, ma sono delle comparse che dicono battute di tipo tre parole.

Menzione speciale a due doppiatrici: Elena Liberati (Ami) e Fabiola Bittarello (Taiga).

Confesso che, in un primo momento, ho trovato la voce della prima fastidiosa. Quando switcha, però, proprio quel timbro contribuisce a rendere Ami ancora più stronza, per poi aderire del tutto al personaggio - tanto che non l'ho più trovata "fastidiosa", anzi, l'ho trovata adattissima!

La seconda, invece, mi ha davvero colpita. Sì, sono certa che Rie Kugimiya faccia una Taiga spettacolare (non ho visto l'originale), ma trovo che Fabiola Bittarello sia riuscita a trasmettere le emozioni di Taiga con un'intensità che di rado ho sentito in un anime doppiato in italiano. Non so se anche lei sia al centro delle critiche per il doppiaggio italiano, ma personalmente mi è piaciuta tantissimo.

In conclusione, se state cercando un buono shoujo con dei bei personaggi, Toradora! è ottimo e si merita tutto il successo che ha avuto.

(Ora vi svelo un colpone di scena: Toradora! non è uno shoujo.

Le novel sono pubblicate da Dengeki Bunko, che ha un target prevalentemente maschile, e il manga derivato è etichettato come shounen. Meraviglioso che un così grande shoujo sia in realtà uno shounen, eh?)

0 notes

Text

I love that you can see how the genre evolved over the years and slowly evovled into what it is today.

Like, 60s is very clearly meant for young kids, the protagonist is very young and it looks so clearly like a... well... a cartoon? (you know what I mean)

70s is when they seem to settle for teen protagonists (minus one or two exceptions) and the magic is more clearly in the forefront. Majokko Megu-chan also seems like it was the first one with a clear antagonist. We also get Cutie Honey, which is the odd one here (as a sidenote, having googled it, I think it is kinda a shame that Majokko Tickle was the Go Nagai property to ge the obscurity treatment, because I think it might have aged better than Cutie Honey...).

80s is when it started playing up with the character designs and the magical tools (toys) begin to show up. they also seem to be getting creative with their premises (Tokimeki Tonight is actually about a girl whose father is a vampire and her mother a werewolf). transformations seem to begin to appear and romance seem like a big deal in a couple of these (chances are, most of them had romance to a degree, but here is when they begin to show up in the opening).

90s is the turning point, with so many classics. We can also see throaways to other series, affectionate parodies, etc.

And of course, here we have Sailor Moon. I mean, just look at it. the epic music, the villains, the heroines in uniform ready to kick ass. Minus specific exceptions, it is like nothing before, and what it did not create, it codified into the Magical Girl DNA. There is also Rayearth, which went the other extreme: Take the Magical Girl premise and put it into a high fantasy setting.

This is also when transformations, multiple magical girls and being a superhero became common to the genre.

Really, when you hear “magical girl”, this decade is what you think of.

2000s is when we get some out there stuff, some classics still. But you can really tell the genre exploded. You can also see how the 90s completely changed the genre and how it reflects in this era.

But really, there are only 2 really particularly noteworthy series in this era: Nanoha and Futari Wa Pretty Cure.

Nanoha would go on to have multiple sequels and spin-offs. While Futari Wa would give birth to... well Precure, the little sister to Kamen Rider and Super Sentai, with Toei making a new Precure series every year and being famous for embracing action and fighting villains.

youtube

Honestly, I want to watch all of these. Lolol

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magical Girl Categories

I got bored, so I've decided to make some random post about Magical Girls, and its sub-categories, because I am a sucker for them and also because I want to school some ignorant people who believe that Sailor Moon was the first MG series ever created

Okay, the Magical Girl (or Mahou Shoujo) genre has its roots in Japan. Its first MG ever was Mahoutsukai Sally, created by Mitsuteru Yokoyama. Debuted in July 1966, the series was the first of the Majokko ("Little Witch") type, and inspired by the american sitcom entitled Bewitched, its japanese title being: Oku-sama wa Majo (TRANSLATION: "The Miss is a Witch"). Of course, after Sally, came lots of magical girls with lots of different formulas and plots, some of them similar, though...

⭐Majokko: Also known as "Little Witch", it uses the witchy formula, with broomsticks, wands, and such. It's rather simple, yet charming, in my opinion. Examples: Majokko Megu-chan and Mahoutsukai Chappy, both using the same formula as Sally's (a member of royalty from a magical world relocating to the mortal world), and both animated by Toei Animation.

⭐Magical Idol: Now, this one's about girls with magical alter-egos, where they are famous and popular (in most cases, these alter-egos are older than the girls). Examples: Creamy Mami, Magical Emi and Fancy Lala.

⭐Slice-of-Life: Another sub-category that's a simple one. It's about girls who are blessed with magical objects to help others and to make their lives more interesting and fun. Examples: Himitsu no Akko-chan and Pastel Yumi.

⭐Magical Warrior: This one is very popular. Thanks to Sailor Moon, which it was responsible for the revival of the MG genre, and opening doors to other stories such as the ever-growing PreCure franchise and Tokyo MewMew.

⭐Parody: Some of the MGs are parodies of the genre, showing us things out of the common plot. Examples: Puni Puni Poemi (absurd, comedy type) and Tonde Buurin (superheroine type, as an animal that no one would've think of: a pig).

⭐Phantom Thief: Think of the Gentleman Thief plot, but with a girl instead! Usually, their deeds are to help others and to solve mysteries, and obviously, it involves having a double life. Examples: Kamikaze Kaitou Jeanne and Kaitou Saint Tail.

⭐Superheroine: This one is about girls fighting crime. It's most present in the western-culture, but the difference is that they tend to be rather girlier. Examples: Cutey Honey, Codename wa Sailor V and Nanako SOS.

⭐Western/Non-japanese: The MG genre had its impact outside the land of the rising sun, and their plots may vary. Examples include (we have lots of them): Jem and the Holograms (Magical Idol), Lolirock (Magical Warrior), Star vs. The Forces of Evil (Magical Warrior), Sabrina the Teenage Witch (Little Witch/Slice-of-Life mash-up), MLP: Equestria Girls (I consider it Slice-of-Life, as it shows normal situations mixed up with ancient magic and mysteries) Miraculous Ladybug (Superheroine) and so many others.

⭐Magical Boys: We have lots of girls, but very few are boys. There aren't many stories where boys are magical AND are the protagonists though... Examples: Steven Universe and Cute High Earth Defense Club LOVE!

⭐Male-oriented: Most of them are angsty stories, all created for the pleasure of seeing young ladies being punished for their dreams! Examples: Madoka Magica and Mahou Shoujo Rising Project.

⭐Adult/Hentai: Most of them are bad parodies, surrounding on the rape theme... I won't talk much about it, as it makes me rather uncomfortable... Examples: Sex Warrior Pudding (a Tokyo MewMew parody) and Venus 5 (a Sailor Moon parody).

⭐Sci-fi: This sub-category plays heavy on the science-fiction and it has no magic at all; but some people seem to consider it a part of the MG lore for some reason. Examples: ESPer Mami and Miracle Limit-chan.

⭐Misc.: Some of these stories have magical concept, but also play on other tropes, so it kinda makes me a little confused... Examples: Onegai! MyMelody, Jewelpet, RiluRilu Fairilu, Flip Flappers, Tokimeki Tonight and Marvelous Melmo.

This research of mine may have some mistakes (correct me if I'm wrong), but I believe it's enough.

I did not have included the references and parodies shown in non-MG shows, because I think they weren't relevant to the researches I made.

I think this post goes for show how much I love the Magical Girl plot, no matter clichéd or overrated it can be! And please: don't go around saying that every MG is a Sailor Moon ripoff...

One more thing:

⭐~Stay magical, be positive and keep the faith!~⭐

350 notes

·

View notes

Text

The front and back cover of the game manual for The Great Magical Girl Strategy: Little Witching Mischiefs (魔女っ子大作戦 Little witching mischiefs) for PlayStation and featuring the stars Showa era Toei Majokko Series.

#Toei majokko series#majokko daisakusen#great magical girl strategy#great magical girl fight#game#games#video game#video games#昭和#showa era#magical girl#魔法少女#majokko#魔女っ子#retro shoujo#retro shojo

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

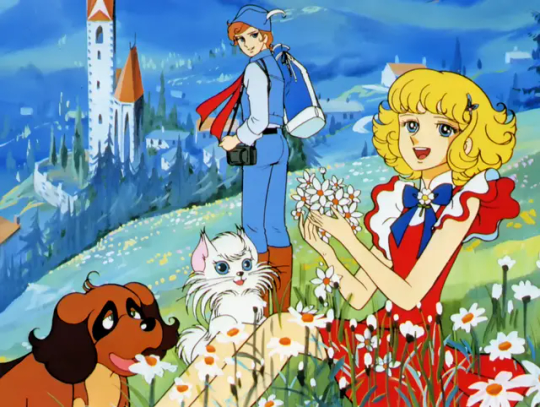

Nobody asked for it but here are some trivia bits about Hana no ko Lunlun:

Character designs were done by Michi Himeno, best known for her collaborations with late animator Shingo Araki. She was also the animation director for the first episode.

Toei Animation’s first magical series since Majokko Megu-chan finished in 1975.

The first magical girl anime to have an original theatrical film. Previous magical girl “films” were just theatrical showings of select episodes.

The very first magical girl series to have an English dub. Unfortunately, only four dubbed episodes have been confirmed. However, all 50 episodes were rescored and edited. Most of the international dubs are based on this version.

Although merchandise tie-ins existed for Toei’s previous magical girl series, Lunlun had a notably bigger push from the get go.

The series implemented a “chief animator system” which resulted in all but the first episode having a very consistent animation style.

The second film was originally going to include a cameo of Lalabell (from Magical Girl Lalabell).

While an accurate translation of the title would be “Flower Girl Lunlun,” the official English title is “Lulu, The Flower Angel.” Lunlun ultimately became “Angel” instead of Lulu for the English dub. This is probably because the American distributor, ZIV International, was also releasing Little Lulu and didn’t want to create confusion.